16 From capital controls and miraculous growth to financial globalization and the financial crisis in Korea

Kang-Kook Lee

Introduction

Mainstream economists and international organizations have argued that financial liberalization and opening encourage economic growth in developing countries. They emphasize gains from financial globalization such as more investment and higher economic efficiency. However, this argument is seriously flawed both in theory and reality. Financial markets always suffer from market failures, and there is no empirical evidence to support the growth effect of financial globalization.

Heterodox perspectives including the Post-Keynesian view have wisely pointed out that effective capital controls could spur economic growth; the success of the developmental states of East Asia in achieving rapid economic development since the 1960s supports this contention. Conversely, capital account liberalization may destabilize the economy, as shown by the recent series of financial crises in those nations who liberalized, including some of these developmental states who had previously succeeded by deploying capital controls.

Korea presents the most telling case in this respect. The Korean economy was a paragon of the “East Asian Miracle” for its rapid economic growth after the 1960s. Strong and effective capital controls of the developmental government, in combination with industrial policy and domestic financial control, contributed to this success. However, selective financial opening in the 1990s led to the financial crisis, and the economic performance has been disappointing after extensive post-crisis economic restructuring and financial opening. This chapter examines the interesting experience of capital controls, liberalization and economic performance in Korea. I briefly review hot debates on capital controls, liberalization and economic growth in the second section. Then, I investigate how capital controls in Korea were successful in encouraging economic growth in the third section. In the fourth section, I present a historical analysis of financial opening and the financial crisis in the 1990s, and post-crisis changes in Korea.

Capital controls, liberalization and economic growth

It is strongly argued that an integrated global financial market enhances efficiency in capital allocation, reduces the cost of investment and disciplines national governments. Developing countries are said to grow faster with financial globalization and international capital movements for these reasons (Rogoff et al., 2004).1 However, when financial markets reek with market failures due to information problems and investors’ herd behaviors, there is no guarantee for such benefits to be realized. Rather, financial opening could generate instability, as seen in many financial crises related to self-fulfilling expectations and contagion effects (Stiglitz, 2000). Though mainstream economists advocate opening financial markets with a view to promoting prosperity, they still underestimate problems associated with open international financial markets. The East Asian financial crisis had the effect of making many economists more skeptical about benefits of financial opening, and led some to call for better regulation.

Heterodox economists understand capital controls and liberalization in relation to a broader context of economic management. They argue that capital controls could help governments to introduce full employment and egalitarian policies as shown in the experience of the “golden age,” when capital controls and Keynesian macroeconomic policy were adopted together in advanced countries. But financial globalization gave difficulty in macroeconomic management to national governments, which lost policy autonomy under the open capital market (Crotty, 1989). This perspective also asserts that capital controls, if effectively adopted under a proper development strategy, can contribute to economic development in developing countries (Crotty and Epstein, 1996).2 In fact, the experience of East Asia clearly demonstrates that capital controls could promote economic growth and mismanaged capital account liberalization brought about the financial crisis.

Proper capital controls may spur growth through several channels. First, controls can stabilize the economy by checking capital flight and regulating volatile capital movements. Also, they allow manipulating of the terms of trade for international trade, thereby boosting export and economic growth. Adequate management of foreign capital and regulation of foreign direct investment (FDI) are necessary to encouragement of productive investment and spillover effects. But if controls are to be successful they should be incorporated into a broad development strategy of capable governments. Only “developmental states” with strong capacity can execute capital controls effectively, and encourage the productive use of foreign capital with industrial policy and financial control (Lee, 2004). Of course, the change of political economy tends to bring about capital decontrols and liberalization, which finally result in economic instability and financial crises in many countries.

Having said that, it comes as no surprise that there is no consensus in debates on capital account liberalization and economic growth. Actually, empirical studies do not find strong evidence that capital account liberalization spurs economic growth (Kose et al., 2006).3 Considering limitations of cross-country regressions, it would be more desirable to examine a specific historical experience to show the relationship between capital controls, liberalization and growth, which I will turn to in the next section.

Economic miracle with capital controls in Korea

The developmental state and state-led economic development

It is now well known that rapid economic development in Korea was guided by the government that strongly intervened into the economy from the early 1960s (Amsden, 1989). Opposite to neoclassical arguments, the role of the state was crucial in Korea’s growth, represented by selective promotion of industry, credit allocation programs, various measures for trade protection, and capital controls. The key to this successful intervention was a specific institutional structure of the government, called the developmental state, that had a characteristic of embedded autonomy and high capacity (Evans, 1995). The state in Korea had relatively strong autonomy because no powerful economic interest groups existed, in contrast with Latin American captured states. Another important feature was a close government—business relationship with cooperation and discipline. This mitigated information problems and limited unproductive rentseeking. Furthermore, the Korean government had highly capable officials due to the long history of the bureaucracy system and efforts for internal reform. It was strongly development-oriented, different from other developing governments that attempted to maximize their own revenues.

The Korean government established a state-led financial system on the basis of this institutional structure, in which the government allocated financial resources to priority industries and firms in line with industrial policy. The major industrial policy purpose was export promotion in the 1960s and the development of heavy and chemical industries in the 1970s. In the process of industrialization, domestic business groups, called “chaebol” had been strongly supported by the government, with preferential credit, tax break and trade protection. The most important tool the government made use of was providing them with preferential bank loans, which were owned and controlled by the government itself. The share of policy credit in all loans of deposit money banks was higher than 60 percent from 1960 to 1991.

It is crucial to understand that the government support for businesses was wedded with effective discipline over their practices. The government provided preferential credit in return for export performance of firms, thereby creating contingent rents and minimizing rent-seeking. Hence, the development model of Korea was a unique combination of the market and state mechanism. The specific character of the state and the government—business relationship in Korea made this peculiar system function effectively. This system resulted in high and productive investment in the private sector, and thus economic growth for some 30 years.

Strategic globalization and capital controls

External economic policy of the developmental state of Korea was peculiar too. Opposite to the mainstream view that Korea benefited from globalization significantly, the Korean government did not pursue a mere opening of the economy. Rather, it pursued a strategic integration with the global economy by managing openness (Singh, 1994). First, the trade regime was not totally open but used the two-track approach of both export promotion and import substitution. The government effectively protected the domestic market so that domestic companies could grow internationally competitive, while it pushed them to increase exports for the world market (Chang, 1994).

More importantly, the government actively used extensive capital controls, incorporated into the state-controlled financial system (Nembhard, 1996). The Foreign Capital Inducement Act in 1961 legally stipulated capital controls that covered a broad gamut of financial activities, from foreign exchanges and currency restrictions to foreign investment. In 1962, the control over the foreign exchanges was transferred from the central bank to the ministry of finance (MoF) to increase the discretionary power of the government. Current accounts were controlled because imports were strongly regulated, and strict exchange restrictions were applied to all capital outflows until the 1980s. Tight regulations of FDI in Korea for the purpose of making FDI a conduit of advanced technology and managerial expertise for domestic development were well known (Mardon, 1990). The government inspected foreign investment projects rigorously and limited foreigners’ ownership of domestic industry.4 FDI that might compete with domestic firms were not permitted, and regulation measures including the foreign companies’ compulsory use of domestically produced parts were introduced.

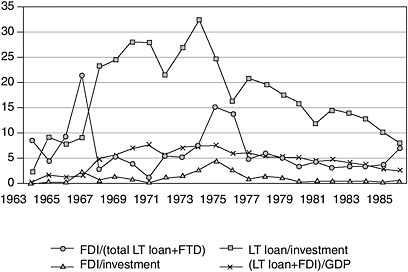

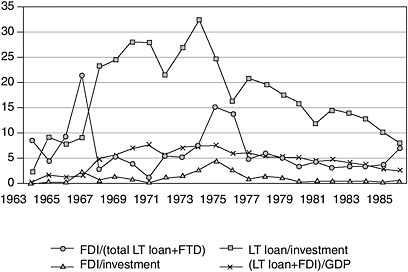

As a result, FDI played only a minor role in capital formation in Korea in comparison with other developing countries. As shown in Figure 16.1, the share of FDI in total long-term foreign capital and total domestic investment was much lower than other Asian Newly Industrializing Countries (NICs), let alone Latin America (Haggard and Cheng, 1987:95).

However, foreign loans were not hindered, but rather promoted, by the government which aimed to mobilize foreign capital to complement scarce domestic savings. The government introduced new laws in 1962 and amended them in 1966 to let state-controlled banks guarantee the payment of long-term foreign loans of the private sector. As private businesses did not have credibility to borrow foreign capital, this policy was essential to their procurement of foreign capital. Due to these measures, long-term loans, particularly commercial loans, soared starting from the mid-1960s as shown in Figure 16.1.5 The Korean government not only encouraged foreign loans but also made hard efforts to promote productive investment of the private sector using these loans. It allowed private businesses to make foreign loans taking the purpose of industrial policy into account, and actively distributed foreign currency loans through the state-controlled banking system for priority industries. Figure 16.2 demonstrates that the share of foreign savings in GDP between 1966 and 1982 was as high as about 5.5 percent, which financed high investment and the trade deficit. Thus, although the government controlled foreign capital strongly and the role of FDI was small, investment and economic growth in Korea banked highly on foreign capital in the early development period.6

Figure 16.1 Long-term loan and FDI in Korea (source: Economic Planning Board (EPB), Bank of Korea (BOK), Ministry of Finance and Economy (MOFE), arrival base).

Note

LT loan means long-term loan.

Figure 16.2 Investment and saving in Korea (1960–2002) (source: Bank of Korea (BOK)).

Note

Foreign saving is calculated by domestic investment minus domestic saving.

Capital controls and management of the Korean government were successful and the specific mode of foreign financing contributed to national development significantly. First, controls over capital outflows were highly effective because of the capacity of the government and they helped to contain domestic capital within the economy. Second, efforts to screen and examine foreign capital inflows made contributions to restricting foreign dominance of the economy. Among others, the developmental government successfully mobilized foreign loans and allocated them into priority sectors under the state-led financial system and industrial policy. Capital controls also helped the government to effectively discipline businesses because they relied highly on external finance and foreign capital that was controlled by the government. Hence, capital controls worked as an important element of a development strategy and stimulated productive investment, and thereby promoted economic growth in Korea

From financial opening and globalization to the financial crisis

Financial liberalization and globalizaiton in the 1990s

In Korea, it was not until the early 1990s that the government introduced extensive financial liberalization and opening. Several measures for financial liberalization including privatization of banks and interest rate deregulation were introduced in the 1980s, but the process was gradual and controlled by the government. However, economic development and the change of the financial system and political economy strengthened demands for more liberalization and opening in finance (Lee et al., 2002). In the financial market, non-bank financial institutions (NBFI), less regulated by the government and mainly dominated by chaebols, grew fast, and the capital market also developed rapidly in the 1980s. This change significantly weakened the control of the government over financing of the corporate sector, while it strengthened the power of chaebols against the government. Chaebols that wanted more freedom in their investment and financing requested financial opening to utilize cheaper foreign capital. The government itself began to retreat from the economy after the 1980s, influenced by strong neoliberal ideology, which gained further momentum in the civil government from 1993. There was also external pressure for financial opening from the US government, reflecting the changed international politics and the end of the Cold War.

Against the backdrop of these changes, extensive financial and capital account liberalization were introduced in the early 1990s (Cho, 2000). Domestically, the government introduced significant liberalization of short-term interest rates and deregulation in NBFI sectors, which caused the term structure of domestic loans to be shorter (Cho and McCauley, 2001).7 Measures for financial opening were also introduced along with the government decision to join the OECD and pressures from domestic and international capital. Capital-market opening for portfolio investment was introduced rather carefully and gradually, and long-term borrowing such as issuing corporate bonds abroad was still regulated in effect.8 Government maintained regulation because it was concerned about financial instability and the weakening of the government macroeconomic management due to volatile foreign financial capital.

However, deregulation for short-term foreign borrowing by financial institutions and firms was much more extensive (Cho, 2000). The government abolished the ceiling on foreign currency loans of financial institutions and reduced the required ratio of long-term foreign loans in 1993. Furthermore, between 1994 and 1996, 24 finance companies were transformed into merchant banks that dealt in foreign exchanges, and banks were allowed to open 28 new foreign branches. The government naïvely expected that short-term loans would be automatically rolled over, and the private sector strongly wanted low interest rates available on short-term foreign loans. Despite extensive opening, the financial supervision system was weakening, and was without an effective monitoring structure (Balino and Ubide, 1999). The problem was especially serious for newly licensed merchant banks that were exposed to high risk due to short-term borrowing and risky long-term investment (Lee et al., 2002). The monitoring of internationalized financial business was not effective either, in spite of the rapid expansion of offshore business.

Financial vulnerability and the 1997 financial crisis

The aftermath of this careless financial opening was growing vulnerability and the collapse of the economy. As a consequence of capital account liberalization, foreign capital inflows rose rapidly as shown in Table 16.1. Foreign debt surged from some $44 billion in 1992 to more than $120 billion at the end of 1997, most of which was due to the surge of short-term borrowing of financial institutions and firms.9

This foreign borrowing financed the investment boom driven by aggressive investment spending by optimistic chaebols in the early 1990s. It is hard to say

that the investment boom was overly irrational because there were several factors to explain it, including the temporary export market boom (Crotty and Lee, 2004).10 But the mode of financing of the Korean economy was problematic and dangerous. For example, the ratio of the foreign debt in all corporate debts rose from 8.6 percent in 1992, to 10 percent in 1994 to 16.4 percent in 1996, owing to the rapid growth of short-term foreign borrowing (Hahm and Mishkin, 2000:63). Chaebols’ higher dependence on short-term and foreign borrowing made their financing structure especially problematic (Lee et al., 2000).11 Financial institutions also became fragile with excessive risk-taking after liberalization and without good risk management. The share of foreign borrowing in total liabilities in the financial sector rose rapidly from 1.2 percent in 1992 to 10.7 percent in 1996, worsening the term structure and currency mismatch problem (Hahm and Mishkin, 2000). Merchant banks were in the biggest danger since they procured foreign capital mainly in short term and lent it in long term as chaebols’ conduit for finance. Therefore, the Korean economy became financially vulnerable due to the significant increase of the short-term foreign debt, following mismanaged financial liberalization and opening.

In 1996, a huge external shock of the export market collapse dealt a severe blow to the Korean economy. Several chaebols started to go bankrupt in the economic recession of early 1997 and this left the financial sector in acute trouble with huge nonperforming loans. As financial institutions, especially troubled merchant banks, struggled to pull back their short-term loans, the crisis spread to the whole economy. Finally, the dangerous structure of foreign debt together with the contagion effect of the Southeast Asian crisis exacerbated foreigners’ lack of confidence (Radelet and Sachs, 1998). When they refused a rollover of short-term foreign loans,12 the Korean economy plunged into a crisis and the government had no choice but to resort to the IMF for the emergency loan in December.

There were serious debates concerning the cause of the East Asian financial crisis. While mainstream economists stress problems of the old development model such as moral hazard and crony capitalism (Borensztein and Lee, 1999; Krueger and Yoo, 2001), heterodox economists emphasize careless financial opening and the problems of the international capital market (Chang, 1998; Crotty and Dymski, 2001). Our investigation points out that mismanaged financial opening, associated with the breakup of the developmental state in the early 1990s, was the most important cause of the crisis in Korea. Capital account liberalization, mainly deregulation of short-term foreign borrowing, without effective regulation was haphazard. The experience of the Korean economy demonstrates that the government must be careful in financial opening and globalization.

Post-crisis restructuring and financial opening

Neoliberal economic restructuring and further financial opening imposed by the IMF after the 1997 financial crisis finally brought down the old development regime in Korea. The Kim government took the position that the crisis was due to inherent inefficiency of the state-led development model and implemented the extensive reform measures (Ministry of Finance and Economy, 1999). As well as restrictive macroeconomic policy, the government introduced the corporate and financial restructuring program, pursuing the Anglo-Saxon style economic model (Crotty and Lee, 2002).13

The government also introduced various policies to totally open its capital markets in 1998 even though the main cause of the crisis was careless financial opening. Those measures included eliminating the limit of foreign ownership in the stock market, opening the bond market for foreigners and allowing the hostile merges and aquisitions (M&A) by foreigners. More liberalization of foreign borrowing of the corporate and financial sector and deregulation of outward investment was introduced in 1999. Further deregulation on individuals sending money abroad was adopted in 2001 and the removal of any regulation in foreign exchanges transactions will be introduced soon (Crotty and Lee, 2005). The Korean government has become especially keen about attracting foreign direct investment (FDI). The Roh government announced the plan of “Northeast Asian Business Hub” with several incentives for foreign investors. It finally concluded the Free Trade Agreement with the US, in spite of domestic opposition in 2007, in an attempt to promote inward FDI.

It is certain that this extensive financial opening and restructuring, together with sharp depreciation of the currency, following the crisis increased foreign investment into Korea significantly.14 Net foreign portfolio investment rose fast from $1.1 billion in 1997 to $4.8 billion in 1999 and $11.3 billion in 2000. FDI inflows recorded a dramatic growth after the crisis, amounting to more than $10 billion in a year, roughly ten times increase from the early 1990s. However, portfolio flows were unstable and the effect of FDI on economic recovery was in question because most of FDI was not productive “greenfield investment” but related to M&A.

All-out financial opening and neoliberal restructuring have actually caused serious concerns about the future of the Korean economy. First, skyrocketing capital inflows have reinforced foreign control of the Korean economy. The foreigners’ share in the Korean stock market rose from 14.6 percent in 1997 to some 43 percent in early 2004. While the increase of foreign ownership is expected to provide better management skill and technology, foreigners also exerted a depressing effect on corporate investment with increasing dividends and the threat of hostile M&A. Foreign control and its detrimental effects are the most salient in the financial sector. Many financial institutions were sold to foreigners, who had come to own as much as 65 percent of ownership of commercial banks in late 2004, a dramatic jump after the crisis. Foreign-owned banks were much more reluctant to corporate lending, which depressed financial intermediation and corporate investment. Second, liberalization of international capital movements may give the government more difficulty in managing the economy. The government has already struggled to fight inflationary pressure due to increasing inflows of foreign capital. It is also reported that international capital movements may destabilize the Koran economy and increase the possibility of the currency attack. Therefore, financial opening and the growth strategy dependent on foreign capital would weaken the role of the government significantly and finally enfeeble national development of Korea.15

In fact, the economic performance of the post-crisis Korean economy is disappointing in general. As Table 16.2 demonstrates, after the fast recovery in 1999 and 2000, the economy fell in stagnation with a serious decline of investment and domestic consumption. Firms’ investment has decreased highly along with the systemic change of the economy as big businesses lowered their debt ratio rapidly and financial institutions have become passive in corporate lending.16 As Figure 16.2 shows, total domestic investment is now lower than domestic saving and, hence, Korean people have grave concerns about underinvestment and future growth prospects. Besides, income distribution and poverty have worsened so rapidly as to hamper the recovery of domestic consumption (Crotty and Lee, 2002). Worsening distribution is common in developing countries that opened capital accounts and underwent the financial crisis, and Korea is not an exception. In sum, post-crisis Korea became a mediocre economy after neoliberal restructuring and financial opening in stark contrast with the economic miracle with strong and effective capital controls (Crotty and Lee, 2005).

Conclusions

Capital account liberalization has been recommended by many economists and international organizations as one of the most important development policies to developing countries. However, this study suggests that its growth effect is ambiguous, and developing countries should be careful about financial opening considering its negative impacts on the economy. It is highly feasible for developing countries to achieve economic growth based on capital controls when the developmental government adopts an effective growth strategy as heterodox economists such as Crotty have argued.

I have investigated the experience of the Korean economy in view of the success of capital controls and the failure of financial opening. Korea achieved rapid economic growth, called the “East Asian miracle” for several decades under the intervention of the developmental state into the economy. The government made successful efforts to manage foreign capital and limit foreign control of the domestic economy in order to promote national economic development, by establishing the capital controls regime that was an element of a broad development strategy. However, mismanaged financial and capital account liberalization in the early 1990s, reflecting the demise of the developmental state and the change of the political economy, made the economy financially vulnerable. The surge of short-term foreign borrowing and foreign debt after this financial opening coupled with the external shock finally led to the financial crisis in 1997. The Korean government introduced neoliberal economic restructuring and extensive financial opening following the crisis. But the post-crisis Korean economy that has pursued financial globalization has been suffering from lower growth and worsening distribution. In particular, there are serious concerns about the foreign control of the economy and higher economic instability along with the rapid increase of foreign capital inflows.

This case study about Korea from the historical and institutional viewpoint supports the heterodox argument about capital controls, liberalization and growth. The experience of capital controls and growth in Korea points to the importance of efforts to manage foreign capital for national development and the active role of the state in economic development. Besides, Korea’s experience of financial globalization and the crisis demonstrates the danger of careless financial opening and its detrimental effects. Other developing economies should learn crucial lessons from the historical experience of successful capital controls and problematic financial opening in Korea.

Notes

1 According to them, capital controls only introduce distortions and inefficiency. They are also ineffective because in most cases private capital can evade these controls.

2 In particular, they underscore political will and the feasibility of controls in practice. Recent studies report that capital controls were rather successful in Chile and Malaysia in the 1990s (IMF, 2000).

3 Many empirical studies report different results, depending on different specifications, samples and periods. Some even report that capital controls can promote growth under several contexts associated with East Asian developmental states (Lee and Jayadev, 2005).

4 Only joint ventures between foreign and domestic capital were permitted and moreover it was compulsory for foreign investors to resell their share after some years.

5 The ratio of payment guarantee on foreign borrowings to total deposit money bank loans jumped from 11 percent in 1965 to 71 percent in 1967 and 94 percent in 1970. The average amount of long-term loans rose from $124 million in the 1960s to $1.2 billion in the 1970s. That of foreign direct investment (FDI) also increased from $6 million to $82 million but its share in total foreign capital flows was still significantly lower than that of long-term loans.

6 This high dependence on foreign loan aggravated the foreign debt problem later in the early 1980s, but the crisis was overcome thanks to the political support from the United States and Japan, and the huge trade surplus in the late 1980s.

7 Interest rates on short-term bills such as CP (commercial paper) were formally liberalized in 1991, and were completely liberalized in 1993–1994, while bank interest rates and corporate bond rates continued to be controlled through moral suasion or administrative guidance despite formal liberalization.

8 The government allowed foreigners to own shares of Korean firms in 1992 with the ceiling of 10 percent for groups and 3 percent for individuals. The ceiling for groups was raised to 12 percent in December 1994, 18 percent in April 1996, 20 percent in October 1996, and was still 26 percent in November 1997 before the crisis.

9 Of course, the change in the international financial markets with the backdrop of high growth in East Asia and low interest rates in developed countries was another factor that in increased capital inflows.

10 Crotty and Lee (2004) argue that the argument to emphasize inefficiency of the Korean economy due to crony capitalism and moral hazard does not have empirical ground. Their investigation reports that profitability of the Korean corporate sector was rather high before the crisis both historically and internationally and there is hardly any evidence for serious inefficiency enough to cause the collapse of the economy in 1997.

11 The top 30 chaebols’ dependence on external finance increased from 58.8 percent in 1994 to 77.6 percent in 1996 and the share of short-term borrowing rose from 47.7 percent to 63.6 percent over the same period.

12 In 1997, the rollover rate of commercial banks fell from 106.3 percent in June to 85.8 percent in September, 58.8 percent in November and mere 32.2 percent in December.

13 The post-crisis restructuring program covered rapid reduction of the debt ratio of Korean conglomerates, called “chaebol,” streamlining of their corporate structure and the shutdown of many financial institutions with resolution of nonperforming loans. The government also introduced measures to strengthen the role of capital markets and labor market flexibilization.

14 Only foreign capital could afford to buy the assets chaebols were forced to sell, corporate-cum-financial opening naturally increased foreign capital inflows partly through a fire sale.

15 A report by Bank of Korea also indicates negative effects of speculative foreign capital such as private equity funds, including potential economic instability, threatening of the management rights, and repressing investment (BOK, 2005).

16 The debt ratio of the manufacturing sector of Korea is now even lower than that of the United States and Japan. The high debt model of the Korean economy appears to finally have come to an end.

References

Amsden, A. (1989) Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization. New York: Oxford University Press.

Balino, T. J. T. and Ubide, A. (1999) “The Korean Financial Crisis of 1997–A Strategy of Financial Sector Reform,” IMF Working Paper, WP/99/28.

Bank of Korea (BOK) (2005) “Problems of Speculative Foreign Capital and Policy Agenda,” 3. (Korean). Finance and Economy Institute.

Borensztein E. R. and Lee, J W. (1999) “Credit Allocation and Financial Crisis in Korea,” IMF Working Paper, WP/99/20.

Chang H.-J. (1994) The Political Economy of Industrial Policy. London and Basingstoke: Macmillan.

——(1998) “Korea: The Misunderstood Crisis,” World Development, 26(8).

Cho, Y. J. (2000) “Financial Crisis in Korea: A Consequence of Unbalanced Liberalization?” Presented at World Bank conference.

Cho, Y. J. and McCauley, R. (2001) “Liberalising the Capital Account without Losing Balance: Lessons from Korea,” BIS papers. No. 15.

Crotty, J. (1989) “The Limits of Keynesian Macroeconomic Policy in the Age of the Global Marketplace,” in A. MacEwan and W. K. Tabb (eds.) Instability and Change in the World Economy, 82–100, New York: Monthly Review Press.

Crotty, J. and Dymski, G. (2001) “Can the Global Neoliberal Regime Survive Victory in Asia?” in P. Arestis and M. Sawyer (eds.) Money, Finance and Capitalist Development. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Crotty, J. and Epstein, G. (1996) “In Defense of Capital Control,” Socialist Register.

Crotty, J. and Lee, K.-K. (2002) “A Political-economic Analysis of the Failure of Neo- liberal Restructuring in Post-crisis Korea,” Cambridge Journal of Economics 26(5).

——(2004) “Was the IMF’s Imposition of Economic Regime Change Justified? A Critique of the IMF’s Economic and Political Role in Korea During and After the Crisis,” PERI (Political Economy Research Institute) Working Paper, No. 77.

——(2005) “From East Asian ‘Miracle’ to Neoliberal ‘Mediocrity’: The Effects of Liberalization and Financial Opening on the Post-Crisis Korean Economy,” Global Economic Review, 34(4).

Evans, P. B. (1995) Embedded Autonomy: States and Industrial Transformation. Princeton: Princeton Unviersity Press.

Haggard, S. and Cheng, T.-J. (1987) “State and Foreign Capital in the East Asian NICs,” in F. C. Deyo (ed.) The Political Economy of the New Asian Industrialism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Hahm, J. and Mishkin, F. S. (2000) “Causes of the Korean Financial Crisis: Lessons for Policy,” NBER Working Paper, No. 7483.

IMF (2000) Country Experiences with the Use and Liberalization of Capital Controls.

Kose, A. M., Prasad, E., Rogoff, K. and Wei, S.-J. (2006) “Financial Globalization: A Reappraisal,” IMF Working Paper, WP/06/189.

Krueger, A. and Yoo, J. H. (2001) “Chaebol Capitalism and the Currency-Financial Crisis in Korea.” Presented at NBER conference, 2001.

Lee, C. H., Lee, K. and Lee, K.-K. (2002). “Chaebol, Financial Liberalization, and Economic Crisis: Transformation of Quasi-Internal Organization in Korea,” Asian Economic Journal, 16(2).

Lee, K.-K. (2004) “Economic Growth with Capital Controls: Focusing on the Experience of South Korea in the 1960s,” Social Systems Studies, 9.

Lee, K.-K. and Jayadev, A. (2005) “The Effects of Capital Account Liberalization on Growth and the Labor Share of Income: Reviewing and Extending the Cross-Country Evidence,” in G. Epstein (ed.) Capital Flight and Capital Controls in Developing Countries. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Mardon, R. (1990) “The State and the Effective Control of Foreign Capital: The Case of South Korea,” World Politics, 43.

Ministry of Finance and Economy (1999) Djnomics: a New Foundation for the Korean Economy, published for Korea Development Institute (KDI).

Nembhard, J. G. (1996) Capital Control, Financial Regulation and Industrial Policy in South Korea and Brazil. Westport: Praeger.

Radelet, S. and Sachs, J. (1998) “The East Asian Financial Crisis: Diagnosis, Remedies, Prospects,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1.

Rogoff, K., Kose, M. A., Prasad, E. and Wei, S.-J. (2004) “Effects of Financial Globalization on Developing Countries: Some Empirical Evidences,” IMF Occasional Paper, No. 220.

Singh, A. (1994) “Openness and the Market Friendly Approach to Development: Learning and the Right Lessons from Development Experience,” World Development, 22(12).

Stiglitz, J. (2000) “Capital Market Liberalization, Economic Growth, and Instability,” World Development, 28(6).