5

Runes and Magical Signs

The knowledge surrounding the ancient lore of the runes had decayed significantly by the sixteenth century. Nevertheless, the history of magic demonstrates that even confused forms can still be used effectively by skilled sorcerers. What most interests us here is the way in which runic magical methods and techniques were handed down in the Icelandic traditions. The two main distinctive graphic features of the Northern style are the use of runes and the magical signs. The runes (Ice. rúnir) or runelike symbols, or even magical letters or characters (Ice. galdraletur), were used liberally in Icelandic magical manuals, as were the magical signs known in Icelandic as either galdrastafir or galdramyndir. As we noted earlier, another striking feature is that the technique by which this magic was effected was often virtually identical with that of the rune magic employed in the pagan age.

Basic runelore is found in appendix A of this book, along with instructions on how to transliterate Old Norse names into authentic runic forms.

As a practical alternative script, the runes continued to be known in Iceland into modern times. They were sometimes used to write inscriptions in and around magical drawings, or to write certain words in spells that the magician wanted to obscure. There was also the use of encoded runic forms called galdraletur, villuletur, or villurúnir. These were meant to confuse and conceal rather than reveal meanings. Runelore was sometimes used by the magicians who composed or compiled these workings by having certain numbers of runelike figures arranged in a way suggestive of the runic system. For example, efforts were made to use a meaningful number of figures to compose complexes or series of signs, such that there are twenty-four or sixteen or eight of them.

The terminology for describing the magical figures and ways of using them was also inherited from ancient runic magical practice. Often these signs are referred to in Icelandic as stafir (sing. stafur), “staves.” This terminology is taken over from the old technical designation of runes as staves or “sticks.” This is because they were from an early time carved on such wooden objects originally used for talismanic or divinatory purposes. The execution of these figures for magical aims is indicated by the Icelandic verbs rísta or rista, both meaning “to carve, scratch, or cut.” At first these terms indicate that actual cutting or carving is intended (into wooden or stone objects, for example), but later they are also used in contexts that show that what is intended is more akin to writing, as with ink and quill on parchment or paper.

Certainly the most outstanding single feature of the Icelandic books of magic is the presence of complex magical signs. Most efforts at classifying these signs attempt to determine their relationships to the runes and their magical functions. There are three main types of such signs.

- Bandrúnir: bindrunes made up of more or less obvious combinations of runes

- Galdrastafir: magic staves, which were perhaps originally bind runes but which have become so stylized as to take on independent lives of their own

- Galdramyndir: magical signs that seem to have always been non-runic, abstract, or iconic signs

Many of the signs appear to be combinations of runes and abstract symbols. The main problem that arises in any effort to decipher these signs is the longstanding tradition of stylization, which can include simplification as well as artificial complication or elaboration. Another way of classifying them has to do with their functions. If they were intended to be protective amulets they might be called by the Latin name innsigli (sigils) or by the Icelandic term varnastafir (protective staves). The term galdrastafir would then indicate magic of an operative nature meant to cause alterations in the environment.

It is almost impossible to read any linguistic meaning in the galdrastafir

(and many of the bandrúnir) without having some indication

being given in the commentaries. These leads usually come in the form

of the distinctive names given to particular signs. Examples of such

names are given in figure 4.1. Careful analysis reveals these

to be bandrúnir that have been stylized in the medium of pen and ink,

yet many of their runic features remain visible. On the other hand,

many of the names given to magical signs have to do with their functions

and not their forms. The names themselves are most often words

with highly obscure meanings. The two most famous names of such

signs are ægishjálmur (helm of awe or terror)

and svefnþorn (sleepthorn)

and svefnþorn (sleepthorn)

. The ægishjálmur is a name given to a figure that could be

simple or extremely complex, but its basic form starts out as a fourfold

or eightfold equal-armed cross with branches at its terminals. With

these two signs we are lucky, because mythic narratives survive that give

us insights into their origins, contexts, and meanings.

. The ægishjálmur is a name given to a figure that could be

simple or extremely complex, but its basic form starts out as a fourfold

or eightfold equal-armed cross with branches at its terminals. With

these two signs we are lucky, because mythic narratives survive that give

us insights into their origins, contexts, and meanings.

The ægishjálmur is mentioned in Old Norse literature concerning the legendary hero Sigurðr Fáfnisbani. When Sigurðr slays the serpent named Fáfnir to gain the treasure hoard of the Niflungs (Nibelungen), one of the objects of power that he obtains is the ægishjálmur. This is not a “helmet” in the usual sense, but rather a general covering that surrounds the wearer with an overawing power to terrify and subdue any enemies. This power is portrayed as being concentrated between the eyes, and it is often associated with the legendary power of serpents to paralyze their prey. This is an ancient Indo-European concept, as demonstrated by the etymology of the Greek drakôn—the “one with the evil eye.” This is also reminiscent of the Gorgons’ ability to paralyze their victims, to petrify or “turn them to stone,” with the gaze of their eyes set in a head surmounted by serpents.

The svefnþorn is also mentioned in Old Norse mythic literature as the magical device with which Óðinn placed one of the valkyrjur, Sigrdrífa (or Brynhildr), into a deep slumber from which she could be awakened only by one who was able to cross the magical barrier of fire placed around her by Óðinn. This feat too was accomplished by the Odinic hero Sigurðr Fáfnisbani. Spells intended to put people into a deep slumber from which they can be awakened only by the magical will of the sorcerer are common in the Icelandic black books, and there are numerous signs that are given the name svefnþorn.

In addition to these two signs there are several other names given to signs, for example, gapaldur, veðurgapi (“weather daredevil,” to cause a storm), kaupaloki (“deal-closer,” for good business), ginnir (also a name of Óðinn), and angurgapi (“reckless one of anger”). The fact that the same name may be attached to two or more different signs shows the names are not so much given to the particular shape of the sign but instead describe the sign’s intended effect.

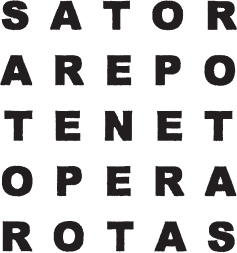

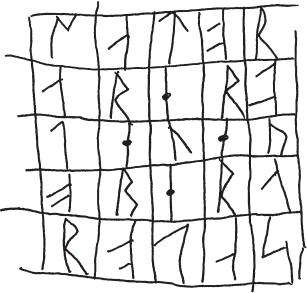

Despite the fact that it is obviously of Mediterranean origin, the so-called sator-square has certainly found a lively existence in the magical lore of the North. As a graphic sign it most often appears inscribed in Latin letters (see figure 5.1 below). The verbal formula was apparently well known, as magical instructions sometimes call for reciting the “sator-arepo.” It seems clear that this means that the practitioner is to speak the apparently nonsense sounds sator-arepo-tenet-opera-rotas. The sator-square formula was so well integrated into Northern practice that it is also found in at least nine runic inscriptions! One example is found on the bottom of a fourteenth-century silver bowl from Dune, Gotland (see figure 5.2, below).

Fig. 5.1. Sator-square

The sator-formula is actually one that conceals the formula Paternoster (“Our Father”) plus the formula “A + O” (alpha + omega). This formula is obviously best known as the beginning of the Christian “Lord’s Prayer.” This prayer is widely used in magical contexts, but the formula actually predates Christianity. We know this because an example of the sator-square was found in the ruins of the Roman city of Pompeii—buried under volcanic ash in the year 79 CE. This predates any known Christian influence in that city, and so it demonstrates that the “Our Father” prayer was used by some sect before the advent of organized Christianity. The sect in question was most likely the cult of Mithras from which organized Christianity adopted many features.

Fig. 5.2. Reproduction of the sator-square from the Dune bowl