Exponential Progress: Thriving in an Era of Accelerating Change

John M. Smart

Introduction  What is foresight? What are the most fundamental ways we use to look ahead? What is accelerating change? Where and why does it occur? What is adaptiveness? How do complex systems maintain their adaptiveness? What values does adaptiveness appear to entail? What is intelligence? Are our machines now becoming intelligent? Finally, how can we get better at looking ahead, so we may not only survive, but thrive in this new era of rapidly accelerating societal change?

What is foresight? What are the most fundamental ways we use to look ahead? What is accelerating change? Where and why does it occur? What is adaptiveness? How do complex systems maintain their adaptiveness? What values does adaptiveness appear to entail? What is intelligence? Are our machines now becoming intelligent? Finally, how can we get better at looking ahead, so we may not only survive, but thrive in this new era of rapidly accelerating societal change?

These are humbling questions. To find better answers than we have today, we must use hindsight (past historical knowledge), insight (awareness of present reality), and foresight (our ability to anticipate, create, and improve the future). The last of these three fundamental time orientations, foresight, depends deeply on the first two, making it the hardest of the three. But foresight also offers us a unique reward—a better vision of what will and may come, and what good we may do with our futures. With that reward in mind, let us consider these big questions, and see what insights we might gain.

Alvin Toffler was perhaps the greatest futurist of the 20th century. He was surely the most popular futurist of the latter half of that century, the era when our modern field of strategic foresight emerged. More than anyone else, he brought future thinking to the masses. From the early 1960s to the late 2000s, with his wife Heidi as editor and researcher, Toffler wrote a series of prescient and increasingly widely read books and articles of social commentary and prediction. Exploring the impact of his first bestseller, Future Shock (1970), six million copies and 50 years later, is the subject of this volume.

Future Shock had its flaws. No piece of futurology is without them, including this one. It was a product of its time, the angst-ridden late 1960s. In this essay I will explore two of its achievements, and their relation to my own work. First, this very influential book got many of us thinking about the upsides and downsides of accelerating change, both in human history and in our modern era. Future Shock’s first two chapters, “The 800th Lifetime” and “The Accelerative Thrust,” are timeless introductions to this topic. Written a decade prior to the arrival of the personal computer, they inspire awe even today.

The book’s second-greatest contribution, in my view, occurred in just a single paragraph. Deep within the book, Toffler describes future thinking as being essentially about three things. Here is the key quotation, from p. 407 of the first edition:

Every society faces not merely a succession of probable futures, but an array of possible futures, and a conflict over preferable futures. … Determining the probable calls for a science of futurism. Delineating the possible calls for an art of futurism. Defining the preferable calls for a politics of futurism. The worldwide futurist movement today does not yet differentiate clearly among these functions.

Within a decade, Toffler’s observation would be called the Three Ps model of foresight. I do not know if it originated with him. He read widely, and likely gleaned it from an earlier source. But after Toffler’s insight, other futurists, most notably Roy Amara at the Institute for the Future, in two key articles in 1974 and 1981, would expand the Three Ps into a set of guidelines for strategic foresight practice.

Strategic Foresight—the Universality of the Three Ps

As Toffler and Amara observed, we can define Strategic Foresight as being, most essentially, about just three things: discovering and predicting the probable, taking advantage of and guarding against the possible, and steering and leading toward the preferable, as we understand them. When I first learned this model, as a new student of foresight in the 2000s, I realized it was congruent with two leading philosophies of science, the first of physics and the second of life.

First, consider physics: Modern physics describes two fundamentally opposing sets of dynamics in our universe. One set, including mechanics, relativity, and equilibrium thermodynamics, is intrinsically predictable over time. This set rules the convergent, statistically “inevitable” futures of our universe—the probable. The other set, seen in such processes as quantum physics, chaotic systems, and non-equilibrium thermodynamics, grows rapidly unpredictable in its specifics. This set rules the divergent and “contingent” features of our universe—the possible. These two types of physics, after billions of years in partnership with and opposition to each other, eventually created life and intelligence, which alone generates preferences. Our preferences, in turn, are relentlessly selected in surviving organisms for adaptation to the environment.

“

Humans are the most complex evo-devo learning systems on Earth. But our developmental genes are also a massive patchwork of legacy code, built on a code base shared with far simpler organisms. We can keep adding to it, but we can’t update the code.

”

Science has no unified theory of quantum gravity today. We don’t yet know how to combine these two fundamentally different yet equally useful ways to view the physical world. Yet both are clearly true, and somehow, over time, they created this very special, emergent, third thing—life and intelligence. Us. So you see, the Three Ps are a very basic way to understand the world. They are firm conceptual ground on which to stand.

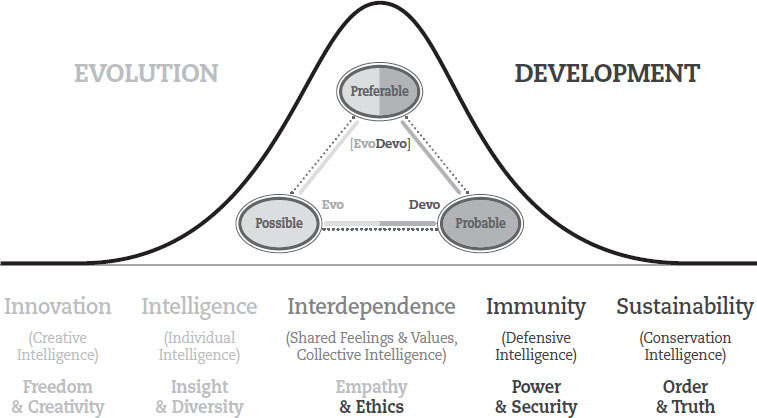

Figure 1

Just as curiously, we can see the Three Ps through the lens of biology. The emerging academic discipline of evolutionary developmental (evo-devo) biology allows us to see life as a fundamental tension between contingent evolutionary and predictable developmental processes. Both processes occur at the same time in biological systems, and we often need to change our perspective in order to see both.

Consider an oak tree (Figure 1). We can look at an acorn seed, with its unique shape, and if we’ve seen any acorn’s prior life cycle, or suspect it is a replicator of a certain class (tree), we can predict many of the features of the tree that will emerge. Much of its “oakness” is developmental. Yet where the leaves and branches will go within any tree is entirely unpredictable. Those features of its “oakness” are evolutionary, involving chaos, contingency, competition, and selection, at molecular and cellular scales. Trees are evo-devo systems.

Likewise, two genetically identical human twins share developmental features that make them indistinguishable from across the room. They also share many psychological features, even if separated at birth and raised apart in different environments. Look at all twins up close, however, and most aspects of them look evolutionary. Their cellular architecture, organ structure, and fingerprints are all stochastically, unpredictably, and contingently different. Their brain wiring emerged in a series of chemical and cellular competitions, in a selective, Darwinian process. We are evo-devo systems.

Within the life of any organism, and in species and ecosystems over macrobiological time, we can define the probable as convergent and predictable developmental processes, the possible as divergent and experimental evolutionary processes, and the preferable as potentially adaptive evo-devo processes. The latter, as in physics, is a mix of the first two, more fundamental types. All three processes, then, appear to be central to life.

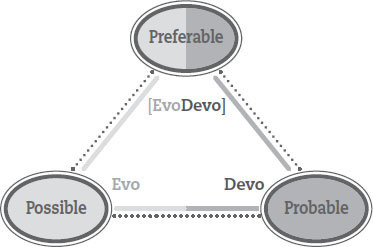

Figure 2 • Evo-devo foresight graphic view

We can depict this evo-devo view of foresight in a graphic shown on Figure 2. The two processes at the bottom of this pyramid are the most fundamental: what can happen and what will happen, in a statistical sense. The third process, preferences, generated by intelligent minds of any type, emerges via evolutionary and developmental dynamics. Selection determines whether those preferences are adaptive.

What about our universe itself? Did it start as a special seed, one with both evolutionary and developmental characteristics, like all living systems? Did it self-organize its great internal complexity in many past replications, the way all life has done? Is it more like a living system than we presently realize? This view seems reasonable to me.

“

The smarter our technology gets, the less help it needs to replicate. Our most rapidly improving digital systems, exemplified by neuro-inspired hardware and deep learning software today, are on a path to becoming autonomous evo-devo learning systems.

”

Consider that if all the most adaptive and intelligent complex systems inside our universe are replicative, evo-devo systems, why wouldn’t our universe, which has built us, be such a system as well? More fundamentally, are evo-devo approaches the only reasonable way to build adaptive and intelligent complex systems? Do they beat out all other approaches in producing and maintaining complexity?

If we live in an evo-devo universe, many curious and seemingly improbable aspects of universal dynamics, such as accelerating change, and our history of increasingly local and hierarchical emergence of complexity, may be best understood as developmental, written into our universe’s “genes” (initial conditions) and environment (multiverse). Simultaneously, many other aspects of universal dynamics, and features of the life and civilizations that emerge within it, across the cosmos, will remain unpredictable, or evolutionary, just as we see in all life.

Each of the Three Ps seems fundamental to the nature of the future. Notice that we must shift our perspective to see each process, operating at the same time.

The Evo-Devo Hypothesis—A Systems View of the Three Ps

Systems theorists study complex systems of many types, looking for commonalities and differences. I trained in that subject under James Grier Miller (Living Systems, 1977) one of the founders of the field. Using the lens of systems theory, we can now make an evo-devo hypothesis about the Three Ps:

All the most adaptive complex systems in our universe are replicative, evo-devo systems. They have used their history of evolutionary variation, developmental replication, and selection to build their internal intelligence, models, and preferences. In that intelligence-building, they use creative evolutionary processes to conduct experiments (explore the possible), and conservative developmental processes to conserve useful knowledge, including their life cycle (maintain the probable). Evo-devo processes, a mix of the two, are how all complex systems generate their intelligence and preferences, which are subject to selection (adaptation) in the environment.

In this hypothesis, even slowly replicating cosmic structures, like suns, encode a very primitive kind of adaptive intelligence. Replicating prebiotic chemicals encode a slightly more complex intelligence. Life has made another great leap in adaptiveness and intelligence by replicating under selection for billions of years. All life has evolutionary genes that regulate stochastic, unpredictable phenotypic variation, and developmental genes that regulate our predictable features, including life cycle. Both evolutionary and developmental genetics, and selection, encode life’s intelligence.

There are actually two different sets of genes in every living thing. Our evolutionary genes work “bottom-up” and “inside-out” in contingent, competitive, and unpredictable ways. They regulate differences, at all scales, between every animal of a species. They have varied a lot over the history of every species. Our developmental genes work “top-down” and “outside-in” in convergent, conservative, and predictable ways. They regulate similarities we see in all animals of any species. These genes are both highly conserved over time, and brittle. Change a few bases in them, and the organism may not even develop.

Humans are the most complex evo-devo learning systems on Earth. But our developmental genes are also a massive patchwork of legacy code, built on a code base shared with far simpler organisms. We can keep adding to it, but we can’t update the code. Like a tree that grows outward from a central trunk, the new morphology we can develop using that code must become increasingly limited, and progressively less innovative and adaptive. Every complex system has its limits.

“

A new computational architecture or algorithm, will commonly give us a 10X to 1000X improvement in speed, efficiency, yield, or performance. Incremental process innovations at the human scale, by contrast, typically give us 20 percent, 50 percent, or 300 percent (3X) improvements.

”

Humanity long ago got around our biological limits by moving our intelligence to a new, hierarchically emergent, replicative system. Along with a handful of other species, we developed culture, which engages in its own constant evo-devo replication of ideas (colloquially, “memes”), in our collective minds and environment, via language, behaviors, and technology.

In fact, we can best define “humanity,” on any planet, as the first species that learns to use extragenetic codes and technology (language, rocks, fire, levers, cities, etc.) to become something more than its biological self. The first use of hand-held and hand-thrown rocks, collectively, to defend ourselves against faster and more powerful predators (leopards, mainly) may have been the original human action. After that, cultural acceleration was off to the races. But human culture, as impressive as it is, depends on humans to improve itself.

We now can see that our digital technology, viewed as a complex adaptive system, is becoming different. The smarter our technology gets, the less help it needs to replicate. Our most rapidly improving digital systems, exemplified by neuro-inspired hardware and deep learning software today, are on a path to becoming autonomous evo-devo learning systems. Their speed of variation, replication, and learning can run at the speed of electricity (the speed of light), a rate far faster than both biological and cultural evolution.

Our leading AIs increasingly borrow algorithms from our brains and now even our immune systems. They seem on track to deliver another major step change for intelligence. What’s more, many astrobiologists think Earthlike planets are ubiquitous in our universe. In a massively parallel, branching, and multi-local fashion, much like speciation on Earth, our universe may produce an accelerating migration of leading intelligence from physical to chemical to biological to social to technological evo-devo replicators on all hospitable planets, as a central feature of its evolutionary development.

Accelerating Change—Then and Now

The idea of acceleration as a natural process is very old. (See my online essay, “A Brief History of Intellectual Discussion of Accelerating Change,” 1999, for more.) In 1766, the late-Enlightenment technology historian Anne-R-J Turgot described the “inevitable” advance of technology, a kind of progress he observed even during Europe’s Dark Ages of social and economic regression. The Scottish economist Adam Smith saw the relentless “quickening” of technological change. Several 18th- and 19th-century scholars, like William Godwin, August Comte, Herbert Spencer and Nicolai Fyodorov, discussed it as well.

In 1904 (“A Law of Acceleration”) and 1909 (“A Rule of Phase Applied to History”) American technology scholar Henry Adams offered our first modern view. He claimed accelerating change is a poorly understood law of nature, as inevitable as the force of gravity, whose equations he applied to humanity’s continual acceleration of innovation and thought. Curiously, some modern quantum gravity research, linking gravity to optimal computation, also takes Adams’s view. (See Caputa and Magan, “Quantum Computation as Gravity,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 2019.)

Like Toffler, Adams discussed the disorientation, stress, and conflict (with the church, state, and elders) caused by societal acceleration. He was also our first modeler of the technological singularity, the hypothesis that accelerating innovations, science, and technology (for him, electricity and machines) must produce a qualitative leap in thinking complexity that exceeds our biological minds.

As the futurist Ray Kurzweil described in his bestseller, The Age of Spiritual Machines (1999), throughout the entire 20th century humanity experienced rapid exponential growth in computing capacity, beginning with tabulating machines in 1890. In 1965, Intel co-founder Gordon Moore (and his popularizer, Carver Mead) gave us “Moore’s Law”—the observed exponential growth in transistors per silicon chip, doubling every 18 months. In 1966, Irving John Good published “Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine,” the first academic paper on the technological singularity. Good proposed that a self-improving computer was the “last invention that man need ever make,” an invention that finally seemed probable, given accelerating trends in computer technology.

“

One way to document dematerialization in our digital technology is to notice how it increasingly substitutes for physical processes. Think of all the matter and processes that have been dematerialized by the software and hardware in a smartphone. We no longer need as many physical objects (cameras, video recorders, flashlights, alarm clocks, etc.).

”

This history reminds us that Future Shock’s discussion of acceleration was not entirely original to Toffler. It was an elaboration of previous work, much of which was known to him. But Toffler eloquently described many societal impacts of acceleration at a time when America had just suffered a particularly wrenching and disorienting decade of social change—the 1960s. Our social anxiety grew further in the 1970s, as economic shocks, pollution, terrorism, urban crime and decline, Watergate, and Vietnam impacted our psyches. The public was mesmerized, and Future Shock became an apt description of the era.

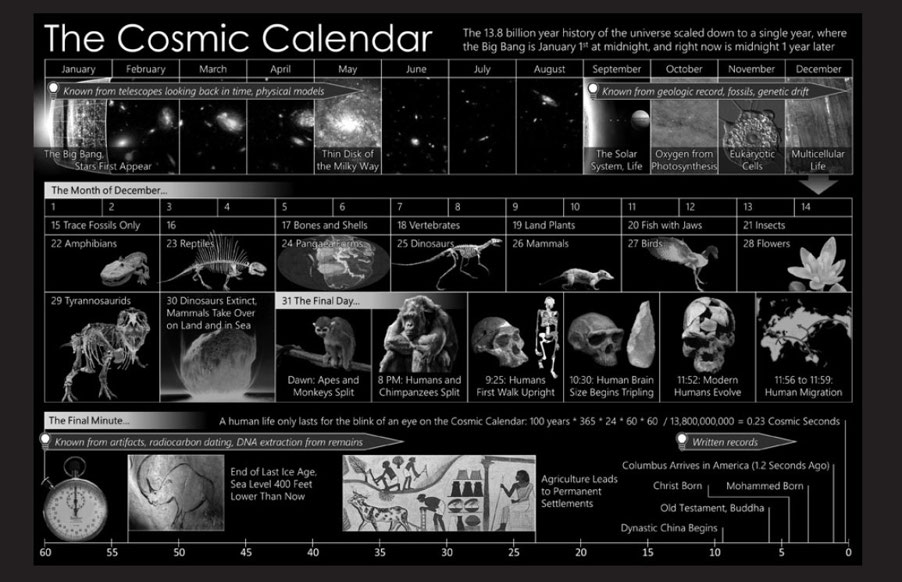

Our next great acceleration popularizer was physicist Carl Sagan. In the first chapter of The Dragons of Eden (1977) and his award-winning TV series Cosmos (1980), Sagan presented the metaphor of the Cosmic Calendar. Placing “significant universal events” in universal history onto a 12-month calendar, Sagan gave us the first widely seen visualization of accelerating change on a cosmic scale (Figure 3).

Seeing this calendar as a youth was life-changing for me. Asking why this improbable universal acceleration has occurred, given all the other plausible histories, has become a lifelong interest. I know others who were also strongly affected by this visualization. Like Earthrise, the first view of our precious planet from space in 1968, the Cosmic Calendar offers a major shift in worldview, a critical new way to see ourselves in relation to the universe.

Is this apparent acceleration some bias of our psychology, perhaps of how we are evolved to remember, or to assess significance? Or is it a real universal dynamic, as Adams proposed? Sagan strongly suspected it was real. He called it a “phenomenon” that science must confront, model, and understand.

In 2003, I co-founded a small nonprofit, the Acceleration Studies Foundation, to advocate for this neglected field of study. We are particularly interested in work that addresses Sagan’s universal, Cosmic Calendar perspective. Since Toffler re-popularized this topic in 1970, a few hundred insightful papers and books (including recent work in quantum gravity) have been published on universal mechanisms and drivers of accelerating change. A much larger number of papers reference societal accelerations, but there are very few general hypotheses and causal models for why universal and societal complexity acceleration occurs. There are fewer still that see its increasingly local and virtual nature.

Figure 3 • CC-licensed version of Carl Sagan’s Cosmic Calendar, by Wikipedia artist Eric Fisk.

I was lucky to have two private interviews with Toffler in Los Angeles in 2008. He thought it ironic that our science and public policy remain so ignorant of these processes. We noted how sad it was that many in our foresight profession ignore or deny accelerating change, even today. But he was also hopeful that we would wake up eventually.

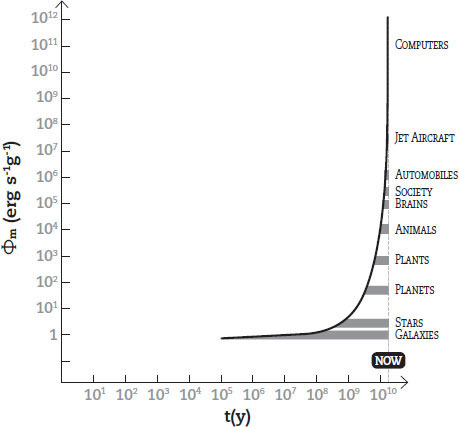

Figure 4 • Progressive acceleration chart, based on Eric Chaisson’s Cosmic Evolution.

Since Toffler and Sagan first popularized this phenomenon, a few bold scientists, like Harvard physicist Eric Chaisson in Cosmic Evolution (2001), have supported Adams’s claim. Figure 4, adapted from Chaisson’s 2001 book, charts a progressive acceleration in the energy flow density (energy flow per time and per mass) in a special subset of emergent complex systems over universal history. Energy flow is used in all complex systems to regulate their rates of change. Notice that the distributions of the various complex systems named at right, a temporal progression from galaxies to computers, have become progressively more local in space and time. This is a key insight we will return to in our next section.

Today’s energetically densest, fastest-changing, and fastest-learning systems are our increasingly brain-like deep learning hardware and software. They are not yet capable of self-evolving, but they may gain that ability sooner than most of us expect. As the graph shows, they are capable, in principle, of changing, learning, and evolving at least 1,000,000X faster than human society.

So far, the scientific community has largely ignored such work. Common critiques are that accelerating change is surely just some quirk of our psychology, that things went faster in the past, or that acceleration must soon become “unsustainable.” Critics usually ignore STEM efficiency trends (to be discussed next), and often conflate the reality of societal accelerating change with the reality that humanity’s population growth, material consumption, and ecosystem degradation trends are unsustainable. Or they assume acceleration cannot continue since it grows exponentially more difficult for any one of us to understand human-machine civilization (our psychological “complexity wall”). Something curious and cosmic appears to be happening, but we are not yet ready to admit it, as a species. Let me now try to better support that admittedly speculative claim.

Our Great Race to Inner Space—Accelerating Change as “D&D”

Since 2006, I have been using the phrase “Race to Inner Space” to describe the general nature of accelerating change. I find this phrase helps to quickly explain where our fastest-changing, fastest-learning, and most-adaptive complex systems always go as they evolve and develop. As far as I can tell, our world’s leading complex systems are always moving their bodies, brains, and actions to inner space, to the domain of the very dense and small (physical inner space) and the very computational and intelligent (virtual inner space). These two processes appear to be fundamental kinds of accelerating change.

“

When we think carefully about it, we must admit that thinking and consciousness, whether in humans or machines, are virtual worlds. They are as real in the universe as the physical world. That’s why we should stop using the phrase “‘real’ world” as an opposite to “virtual world.” Information is as real as physics in the universe we live in.

”

To better understand these two kinds of acceleration, we can use two scholarly words: densification (our movement into physical inner space) and dematerialization (our growth of virtual inner space). They form a useful acronym, “D&D.” The first term, densification, is the “engine” of accelerating change, its physical driver. The second, dematerialization, is the “steering” of accelerating change, its informational driver. We can also call D&D by another scholarly phrase, STEM compression, as these two accelerations outline how our universe turns increasingly local, dense, and miniaturized arrangements of physical space, time, energy, and matter (STEM) into various forms of mind. I suspect, but cannot prove, that maximizing the growth of D&D, via five adaptive goals we will discuss, is how leading complex systems stay dominant in their niches.

To better understand densification, consider how our universe’s leading frontier of structural and functional complexity creation began with universally distributed early matter, then localized to large-scale structure, then to our first galaxies, then to metal-rich stars replicating in special galaxies, then to stellar habitable zones circling special stars. On Earth, the first gene-based life may have started locally, around volcanic vents (archaea), but eventually ranged miles deep in our crust, and miles in the air (prokaryotes). Genetic replication eventually created eukaryotic life, whose range is restricted to just a sliver of our planet’s surface. This led to multicellular life, whose range is even more localized, and to nervous systems, which are far more local, dense, and dematerialized forms of cellular computation than we find in unicellular collectives.

In human brains, synaptic networks eventually supported replicating words, codes, and ideas (“memes”). Memes are more densified and dematerialized than genes. They replicate and vary by communication and conversation among receptive brains, and rearrangement of synaptic weights. Even bacterial replication is slow by comparison. Memes are so virtual that scholars still argue, sadly, if they even exist.

We also see net densification in human social structures. We began in one place in Africa as rock-wielding Homo habilis, expanded out to become nomadic hunter gatherers, then densified, into tribes, then villages, then cities, and societies run by markets, networks, governments, and, in recent decades, also by highly process-dense corporations. After initial, brief, next-adjacent explorations outward, at every new level of emergence, this has been a great race inward.

Humanity is today engaged in one of these brief initial forays outward. We’ve recently gained the ability to get off our planet, and we think we are going to the stars. I think that view is 180 degrees wrong. Yes, we will explore our local planets, even though our robots already do it better than us, and it will be inspirational, like Edmund Hillary climbing Mt. Everest. But the real next frontier for humanity, and for our coming machine intelligence, is inner space.

Densification tells us why process innovations at the nanoscale and in infotech often give either speed, efficiency, or productivity gains (or sometimes, all three) of 10X to 100,000X (1000 to 10,000,000 percent), in single-step innovations, versus far more modest innovation gains at human scale. A single change in an active site of an enzyme, or a new computational architecture or algorithm, will commonly give us a 10X to 1000X improvement in speed, efficiency, yield, or performance. Incremental process innovations at the human scale, by contrast, typically give us 20 percent, 50 percent, or 300 percent (3X) improvements. These are all far from a single order of magnitude (10X) in change. In contrast to the nanoscale, the human scale is outer space. It is an environment where all complex systems are far slower to adapt, improve, and learn. That’s just how our universe works.

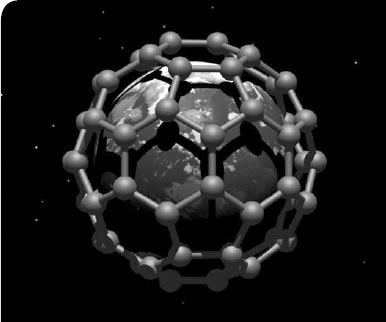

In 1959, the physicist Richard Feynman gave a futuristic talk on a then-nonexistent science. The title was “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom.” Feynman asked his audience to recognize that a world of complexity could be built and accessed, at the molecular and atomic scale, using nanotechnology. In 1985, the nanotech field finally emerged with discovery of C60, Buckminsterfullerene, a spherical molecule named after the futurist Bucky Fuller, for its resemblance to his geodesic domes. Figure 5, Earth in a Bucky Ball (2003) by nanoscientist Chris Ewels, conveys Feynman’s idea. Humanity is running a great race to inner space, not outer space, because that is where life’s greatest capacities, diversity, and consciousness apparently lie.

Figure 5 • Earth in a Bucky Ball, by nanoscientist Chris Ewels.

Today, engineering advances at the nanoscale, in physics, chemistry, biology, materials science, and computation, are at the cutting edge of all our technological advances. In physics, we are designing early quantum computers, which perform some algorithms 100 million times faster than classical computers. We get billions of times more fusion energy out of our experiments today than when we started in 1973, and we may see our first commercial fusion within a generation. In chemistry, we improve battery performance, make fresh water from our oceans, and even do artificial photosynthesis at ever faster rates each year. In biology, we recently gained the ability to edit genes using molecular scissors (CRISPR-Cas9 and other techniques) and insert gene drives (“molecular machines”) into animals. Yet nanotechnology remains in its infancy. We still fund it only modestly, just $18 billion by all governments and firms annually in 2012, per Lux Research, and we mostly don’t know what we are doing yet.

As deep machine learning gets involved, however, watch out. Just last year, a team at Google Deep-Mind used deep learning to find a number of solutions in protein folding. This is a fiendishly difficult problem in biochemistry, and their neuro-inspired AI handily beat out all the other human-built, and much older, AI approaches. Many more of these kinds of advances will happen as our computer systems and networks get more complex and neuro-inspired in coming decades.

Dematerialization, for its part, tells us why organisms with nervous systems, and then brains, came to rule our planet, and why modern software is “eating the world” the smarter it gets, as Marc Andreessen observed in 2011. Dematerialization is captured in the popular phrase “mind over matter,” or better yet, mind is always emerging from and increasingly controlling local matter, at an ever accelerating rate. We can apply this phrase to both human brains and our emerging digital brains.

One way to document dematerialization in our digital technology is to notice how it increasingly substitutes for physical processes. Think of all the matter and processes that have been dematerialized by the software and hardware in a smartphone. We no longer need as many physical objects (cameras, video recorders, flashlights, alarm clocks, etc.). The more intelligent our digital systems get, the more general purpose they become. A related concept, economic dematerialization, can be measured as the increasingly informational nature of societal GDP. All the world’s leading markets are turning into “knowledge economies” (or better yet, intelligence economies), selling increasingly high-value digital services (bits, media, info, software, compute) over atoms.

Another way to measure dematerialization is to notice that the better our simulations become, the more we virtualize human behavior itself. Increasingly, our thinking beats out acting, and the virtual beats out the physical, both to discover and to create better futures. As adults, we found that simulation (experimentation) increasingly outcompeted the physical play (experimentation) that we did as children. Adults, with enough experience, find it more adaptive to “play in our minds” instead. Our machines, too, are rapidly growing up. Soon their simulated worlds will be richer and more valuable than their physical play. These are major societal changes we’re still only beginning to recognize.

When we think carefully about it, we must admit that thinking and consciousness, whether in humans or machines, are virtual worlds. They are as real in the universe as the physical world. That’s why we should stop using the phrase “‘real’ world” as an opposite to “virtual world.” Information is as real as physics in the universe we live in. All life’s virtual processes emerge out of physical reality. So do the realities our computers are creating for us. So rather than “real” and virtual, physical and virtual—or nanotech and infotech (D&D)—are the right pair to think about as we run this Great Race.

“

If D&D are fundamental universal trends, as I think they are, we should look inward, not outward, to our next frontier. Our destiny is density and dematerialization.

”

One of the most surprising things about accelerating D&D processes, from an environmental perspective, is that they use progressively less space, time, energy, and matter (STEM) resources, per computation and physical transformation, the more miniaturized and virtual they become. Because of this accelerating STEM efficiency, our fastest-improving systems never run into Malthusian resource limits and S-curves the way all biological reproduction does. Each new generation of computer typically has both a smaller ecological footprint, and greater innovation capacity, per computation, than its predecessor.

Today’s computers are still far more energy wasting than our long-evolved human brains. But unlike us, they are on an astoundingly fast resource-efficiency improvement curve. In the lab, we have designed neuro-inspired hardware that is thousands of times more space, time, energy, and matter efficient than our current computers, and we are still in the infancy of such work. Because of D&D, our accelerating machine intelligences always shrink their use of physical resources per computation, and grow their learning and simulation capacity. That combination is uniquely powerful, and we still don’t broadly appreciate its implications for our future.

Where might the cosmic acceleration of D&D end? In a philosophical paper, “The Transcension Hypothesis” (2012), I speculate that via STEM compression, all intelligent life increasingly transcends, or grows out of, our physical universe. Our descendants may use nanotechnology, and architectures like quantum computing, to make even denser, more capable, and more intelligent systems than biology has to date. After that, we may migrate to femtoscale life, intelligence, and complexity. Eventually, we may end up in black hole-like environments, which some physicists propose are ideal for both computation and contact with other advanced civilizations. See Cadell Last’s “Big Historical Foundations for Deep Future Speculations” (2017) for a good review. At least, this future looks plausible to me. We shall see, as they say.

“

Each human connectome is the most advanced computational nanotech (physical inner space) and infotech (virtual inner space) that presently exists on Earth. Perhaps we’d treat each other better if we reflected daily on that fact.

”

To sum up this introduction to D&D, most of us presently imagine that it is our destiny to explore outer space. We seem driven to expand into the cosmos as our civilization develops. I call this view the Expansion hypothesis. I think that view of the future is like looking in the rear view mirror while driving forward. Life has made brief jumps outward, but the macrotrend is always inward. Arguably, machine evolution in nanospace is now more productive than most things humans are doing in human space.

What philosopher Cadell Last calls the Compression hypothesis is a much better description of both our past and future. Leading complex systems have continually discovered ever denser, more efficient, and more intelligent ways to use space, time, energy, and matter (STEM) resources to adapt. I call that process STEM compression, and it seems critically important to understanding accelerating change. If D&D are fundamental universal trends, as I think they are, we should look inward, not outward, to our next frontier. Our destiny is density and dematerialization.

When we are D&D-aware we are what I like to call “accelaware.” We understand a few things about the plausible dynamics of accelerating change, and how they may impact society in the years ahead. We recognize why well-managed cities, corporations, markets, digital networks, automation, and AI will increasingly win over less-dense and dematerialized alternatives. We are eager to foresee and manage the many new risks and disruptions that these processes create.

For a good introduction to accelerating change and its dizzying variety of societal implications, I’d recommend books by Ray Kurzweil (The Age of Spiritual Machines, 1999; The Singularity is Near, 2005), Kevin Kelly (What Technology Wants, 2010), Peter Diamandis and Steven Kotler (Abundance, 2012; Bold, 2015), Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee (The Second Machine Age, 2014; Machine, Platform, Crowd, 2018), Klaus Schwab (The Fourth Industrial Revolution, 2016), Kate Raworth (Donut Economics, 2017), Rachel Botsman (Who Can You Trust?, 2017), Max Tegmark (Life 3.0, 2017), Tim O’Reilly (What’s the Future?, 2017), and Byron Reese (The Fourth Age, 2017). Some good academic anthologies also exist, such as Amnon Eden’s The Singularity Hypothesis (2013).

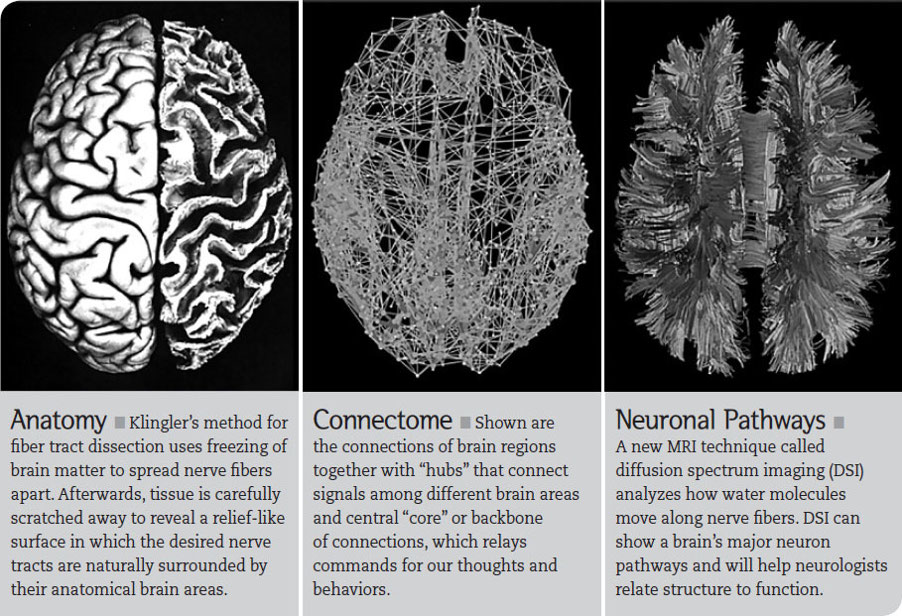

The Primacy of Consciousness and Natural Intelligence

Which complex adaptive systems on Earth have gone the furthest into inner space so far? That would be human thinking and consciousness. Each human connectome (Figure 6) is the most advanced computational nanotech (physical inner space) and infotech (virtual inner space) that presently exists on Earth. Perhaps we’d treat each other better if we reflected daily on that fact. Consider that there are 80 trillion informationally unique synaptic connections inside every 3-pound human brain. That is an incredible feat of nanotech, and an astonishing virtual uniqueness, inside every one of us. All our moral, empathic, and self-, social-, and universe-reflective thinking and feeling are virtual realities (infotech) which have arisen directly from that nanotech. It’s phenomenal.

Evolutionarily, consciousness is life’s newest inner space frontier. Science still doesn’t understand it well at the physical level. Yet we can observe that it emerged as a new kind of adaptive complexity for human brains, exploiting new forms of physical and virtual inner space, and it has allowed human society to become both more empathic with other life-forms and more ethical as well. But these advances have occurred only on average in the network, which means a few individuals have grown increasingly dangerous at the same time. The primacy of consciousness is why social values like ethics and empathy are at the center of human adaptiveness, as we will discuss.

Tomorrow’s machines will run further and faster into nano- and infospace. The online knowledge web, less than 30 years after its invention, is already a vast, low-level simulation of physical reality, even before high-level VR, AR, and simulations have arrived. We’ve also seen accelerating virtualization (emulation capacity) of hardware, operating systems, infrastructure, and business processes since the 1960s. Ever more of life’s processes migrate to the cloud every year.

Figure 6 • Visual description of the human connectome.

Our most advanced simulations today are partly “artificial” intelligences, engineered top-down using human models, and partly natural intelligences, emerging bottom-up, with us as trainers and gardeners of their self-learning components. We do not construct, and cannot identify, most of the algorithms in our deep learners today. They emerge on their own, with us observing them do so.

If neuro-inspired computers increasingly outperform all other forms of AI, as I’ve long predicted (it’s generally far easier for nature to copy and vary than to reinvent outright), the main role of our future AI safety “engineers” (read: gardeners) will be to select them for safety and symbiosis with us. Such artificial selection is how we tamed our domestic animals over the last few thousand years, and it is even how we have tamed ourselves. Domestic animal brains have typically shrunk 20 to 30 percent over the last 15,000 years. Human brains have shrunk 10 percent over the same time period (see “The Incredible Shrinking Brain,” Discover Magazine, 2010). In both cases, we removed more impulsive and asocial behaviors and programming, via selective reproduction (and in our own case, ostracism and killing of “bad actors”), making a more interdependent and adaptive social intelligence.

“

We’ve also seen accelerating virtualization (emulation capacity) of hardware, operating systems, infrastructure, and business processes since the 1960s. Ever more of life’s processes migrate to the cloud every year.

”

It seems that evo-devo methods and selection always win, as the best and fastest way to create trusted complexity. In my view, humanity will be forced to select these natural machine intelligences to be safe by constantly stress testing them, by knowing their past behavior, and by making sure we always have many more trusted and loyal breeds of deep learners (I like to call them “Labrador AIs” and “Doberman AIs”) around to defend us against the inevitable “rogues” that will emerge in someone’s basement. There is no other viable path to safety for natural intelligence, in my view.

Some futurists, like Klaus Schwab of the World Economic Forum (Schwab, The Fourth Industrial Revolution, 2016), propose that we are now in an “Intelligence Revolution,” with the advent of deep learning computers, the cloud, and other powerful new computing technologies. The WEF is one of several global organizations now working on AI ethics. As I write this, Microsoft has just pledged $1 billion to OpenAI, a community seeking to create safe artificial general intelligence. Such work is commendable. We can see that machine intelligence is developing into something new, and we must prepare for it.

But how fast is machine intelligence developing? Are we truly in a new era of accelerating change, or merely the next stage of our now 70-year-old Information Revolution? This question isn’t a quibble. In effect, it asks whether humanity still has decades to do our AI safety and ethics training and gardening well, or whether we might now see AI start improving itself fundamentally roughly every year, a pace that would give us far less time to adapt.

Consider our past technology revolutions. Each created powerful new densification (including vast temporal densification, or acceleration) of human interaction and value creation, and new dematerialization in its forms of social organization and simulation (collective intelligence):

1  Our Tool-Making Revolution occurred over hundreds of thousands of years. Tools like hand axes, the control of fire, clothing, and spears got us congregating in large, dense hunting and gathering bands, and got us to every habitable zone on the planet.

Our Tool-Making Revolution occurred over hundreds of thousands of years. Tools like hand axes, the control of fire, clothing, and spears got us congregating in large, dense hunting and gathering bands, and got us to every habitable zone on the planet.

2  Our Agricultural Revolution occurred over thousands of years, greatly densified food production, and created our first empires, law, and our first astronomical rich-poor divides.

Our Agricultural Revolution occurred over thousands of years, greatly densified food production, and created our first empires, law, and our first astronomical rich-poor divides.

3  Our Industrial Revolution occurred over hundreds of years, greatly densified the production of things, and created the modern corporation, the new, faster, and less extreme rich-poor divides of the capital class, and social democratic states.

Our Industrial Revolution occurred over hundreds of years, greatly densified the production of things, and created the modern corporation, the new, faster, and less extreme rich-poor divides of the capital class, and social democratic states.

4  Our Information Revolution has been occurring over decades. It has greatly densified computing and communications, and created globalization, a knowledge and entertainment society, the even faster-emerging rich-poor divides of our tech titans and ultra-rich, and a number of new societal problems, including eroding social contracts and an increasing number of citizens arguing for a more equitable distribution of technological wealth, and a revitalization of our democracy.

Our Information Revolution has been occurring over decades. It has greatly densified computing and communications, and created globalization, a knowledge and entertainment society, the even faster-emerging rich-poor divides of our tech titans and ultra-rich, and a number of new societal problems, including eroding social contracts and an increasing number of citizens arguing for a more equitable distribution of technological wealth, and a revitalization of our democracy.

I would argue we remain far from any fifth (by my count) revolution today. Today’s deep learners are based on a few key computer science discoveries made decades ago, discoveries we will now slowly apply to societal processes. There are many things deep learners can’t do well or at all today, like compositional logic, emotions, ethics, and complex model building. I’d bet many more new architectures, algorithms, and approaches will need to be discovered, both via new neuroscience, and new hardware and software experiments, before our AIs will be self-improving enough to become generally (and naturally) intelligent.

As the Gartner consultancy’s Emerging Technologies Hype Cycle 2018 makes clear, deep learning today is in a peak of inflated expectations due to recent high-profile advances. Predictably, many people and firms are stoking and capitalizing on this AI hype in an attempt to profit from an emerging technology. So let us not mistake a clear view (the apparent inevitability of general AI) for a short distance (its arrival soon). Circa 2060 has long been my own intuitive guess for when we might expect a (General) Intelligence Revolution. At the same time, it is wise and proactive to prepare now.

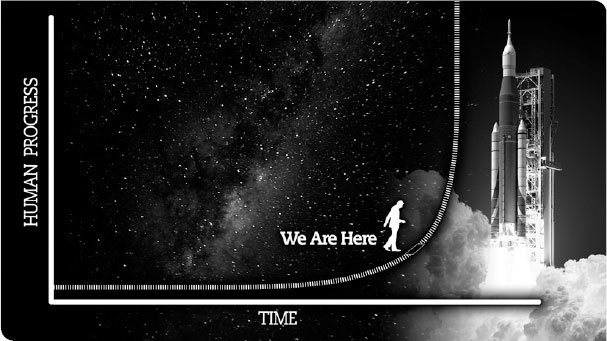

Figure 7 • Accelerating Change graph of Human Progress in time.

Exponential Foresight—A Useful But Limited Model of Change

Fortunately, since 2008, Singularity University (SU) has become the new leading popularizer of what we might call Exponential Foresight. SU has conferences and chapters all over the globe, and good free newsletters and social feeds. I recommend their community, and several others, like Azeem Azhar’s superlative podcast, Exponential View, and Tim O’Reilly’s Next Economy conferences, to confront organizational and societal issues of accelerating change.

Thanks in no small part to the popularization of exponentials in the technology press and by thought leaders like SU, we see popular discussion of Wright’s Law (experience curves), exponential technology price-performance curves, accelerating innovation adoption diffusion rates, and issues of exponential information growth and intelligence production. Beginning with Boston Consulting Group’s work with experience curves in the 1970s, and in consultancies like Deloitte, McKinsey and Accenture today, leading foresight teams have forecast aspects of exponential change, and imagined their impacts. But even today such work isn’t widely done, and most of us still don’t recognize our new reality.

“

Consider our past technology revolutions. Each created powerful new densification (including vast temporal densification, or acceleration) of human interaction and value creation, and new dematerialization in its forms of social organization and simulation (collective intelligence).

”

Many of us look to the future, like the observer above, congratulate ourselves on seeing that modern progress is no longer linear, but exponential, and then make the mistake of expecting the world will continue its current gentle exponential rates of change. But it won’t. Due to D&D, scientific, technical, and economic change are actually superexponential at the leading edge of complexity. Certain changes compound and converge on each other. See Kurzweil, Brynjolfsson, and others mentioned earlier for good references. A wall of change is coming toward us at present. So we must learn to think both superexponentially and developmentally in leading D&D domains, while avoiding perennial hype.

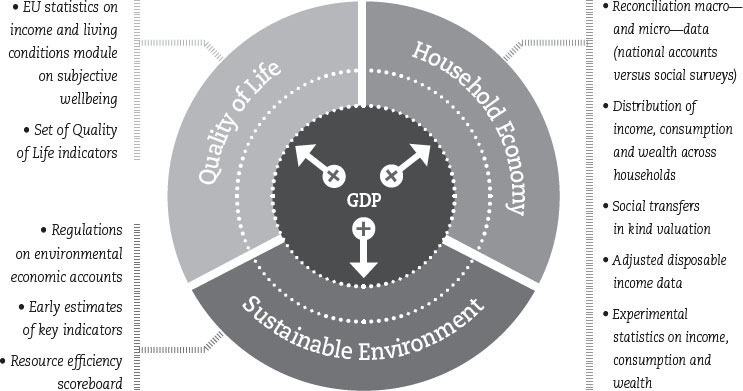

Even our New Growth economists, like Paul Romer, who describe the economic value of information and knowledge, still have no good models for accelerating data, network, AI, and automation growth, and the ways exponential technologies impact production, jobs, and the social contract. Part of the problem is that traditional economics uses price alone to value things, emphasizing financial profit, the market, and state regulation. Economics doesn’t yet see or measure all the other ways that accelerating information production and intelligence change and produce societal value. Robert Kennedy famously observed the inadequacy of GDP as an economic progress metric in 1968. Consider the EU’s commendable Beyond GDP movement, with its emerging social and economic progress metrics for the Household Economy, Quality of Life, and Environmental Sustainability (Figure 8).

As economist Kate Raworth elegantly describes in Donut Economics (2017), current economic theory ignores value creation and maintenance in households, in the commons, in our ecosystem, and (I must add) in our increasingly self-improving technologies themselves. It is no wonder economics is so dismal at prediction. It doesn’t yet understand real value creation, or technology as a learning system.

Figure 8 • European Union “Beyond GDP” graph

In reality, ever since the Information Revolution, we can say that “the machines we tend, more than the arms we bend” have driven most marginal growth in human capability and wealth. Toffler describes this new reality well in The Third Wave (1980), and again in Revolutionary Wealth (2006). One message of the latter book is that technical productivity, even more than labor productivity, is now the leading source of GDP and value growth. In this brave new world of exponential economics, ever-smarter software, ever more sophisticated machines, global digital platforms, and specialized and connected individuals are growing Earth’s technical capacity and economic value like never before.

Consider that the value of Amazon’s stock has increased 1,200X since 1995. Nvidia’s stock has increased 148X since 1999. Netflix’s stock has increased 312X since 2002. Tesla’s stock has increased 58X since 2010. Now there are a crop of new Chinese digital leaders, like Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, and ByteDance, whose real growth is even faster than our US tech leaders. China’s rise in recent decades has been, in a word, meteoric, and it has been based primarily on technical and entrepreneurial productivity. Read Kai-Fu Li’s AI Superpowers (2018) for a glimpse at what may come next. The Intelligence Revolution will dwarf the Information Revolution in its value creation.

I’m not saying that there won’t be new bubbles and crashes, or that any of these individual firms will survive, or that our central bankers and elites won’t continue to print fiat money and attempt to extract value faster than our machines can create it. Human greed and shortsightedness are perennial, and market conditions for each firm are always contingent. So please invest in a diverse set of ethically led technology firms in years ahead, regularly reevaluate any investment, and don’t speculate in unaccountable ventures like ICOs. At the same time, don’t ignore all the real accelerations in value creation.

When we are accelaware, each of us should realize that technology leaders that best use D&D drivers like nanotech, urbanization, AI, automation, platforms, and crowds will greatly outperform our other investments (including real estate, commodities, bonds, etc.) for the rest of our lives. Channeling L.P. Hartley, we can say that the investing past is a foreign country. We truly are in a new world.

Having said all this, we must now ask: What are the limits of an exponential view of the world? What could it become, and what is it missing, by its narrowness? Such questions can help us move beyond exponentials to deeper models and alternative dynamics.

First, we must observe that exponential extrapolations, for all their value, do not tell us about other forms of nonlinear dynamics. For example, as societies become wealthier, many of our most valuable societal processes saturate (reach peaks) and others decelerate.

Consider Figure 9 exemplifying Eroom’s Law (Moore’s Law spelled backward), the empirical observation by Derek Lowe in 2015 that half as many drugs have been approved by the US FDA, per billion dollars spent, roughly every nine years since the 1950s (Jones and Wilsdon, “The Biomedical Bubble,” 2018).

What are we to make of this negative exponential? At one level, it suggests S-curves, with their negative exponential phase after an inflection point, are often better models than positive exponentials, which are simply the first phase of any S-curve. Likewise, power laws and other nonlinear functions are often better models for winner-take-most economic dynamics in our network-based economy.

Causally, Eroom’s Law seems a consequence of S-curve factors like the declining returns of current drug discovery methods, the rising economic and legal value of human life, increasing media coverage of harm, and the growing legal and regulatory oversight (and when it goes too far, “safetyism”) found in all wealthy societies. It is also a consequence of power law factors, like the continued rise of Big Pharma, and the decreasing innovation and competition that always accompany too much market consolidation. But try making an evidence-based model for Eroom’s Law that sociologists, economists, and political scientists will adopt today. It’s not going to be easy. We may need the AIs to do it, via simulation and analysis of natural experiments in different societies.

Figure 9 • Eroom’s Law: the number of molecules approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (pharma and biotech) per US$bln global R&D spending

We are becoming aware of other predictable peaks and decelerations in recent decades. Our top foresight publications, like The Economist, now routinely discuss concepts like Peak Child, Peak Population, Peak Car, Peak Steel, Peak Anonymity, Peak Greenhouse Gases, and Peak Oil Demand (we humans may never reach actual Peak Oil, or use half of most other nonrenewable resources, if D&D continue). Many peaks are either here now or we can see them on the horizon. Others, like Peak Species Loss, Peak Trash, Peak Warfare, and Peak Authoritarianism are also imaginable, but either harder to predict or to agree upon today. (Did we hit Peak Warfare in WWII? Perhaps. See Steven Pinker, Better Angels of our Nature, 2010).

“

Current economic theory ignores value creation and maintenance in households, in the commons, in our ecosystem, and (I must add) in our increasingly self improving technologies themselves. It is no wonder economics is so dismal at prediction. It doesn’t yet understand real value creation, or technology as a learning system.

”

To my mind, most of these peaks signal efforts of our global civilization to self-regulate, consciously or unconsciously. Fortunately, new forms of social organization seem poised to soon emerge, forms far more powerful and intelligent than any in human history. There are new technologies now emerging that look powerful enough to become key regulatory pathways in a new, more global human-machine system—a superorganism, of sorts.

Consider personalized AI systems (Personal AIs, PAIs), aka intelligent personal assistants. Within a decade or two, I expect many of us will use personalized cloud-based AI software that continually trains on our private data (email, mobile, web, even speech), has primitive models of our values, goals, and preferences, and is able to read the public values and preferences data of other actors with verified identities and reputations in both public and private social graphs. Such PAIs will be able to increasingly advise us on what to read, what to watch, who to meet, what to buy, how to give public and private feedback, how to vote, and what social actions, policies, and legislation best reflect our preferences, for good and ill. PAIs will clearly have complex effects in 21st-century society.

We already have proprietary products and services that do this advice-giving narrowly, with very little personalization (e.g., Google Assistant, Siri, Cortana, Alexa, Spotify). Apple’s Siri, launched with iOS 7 in 2013, was the most recent reboot of this idea. But like humanoid robots, the idea of personalized intelligent agents has been around since the AI field first emerged in the 1950s.

Due to recent major advances in language understanding and world understanding (knowledge graphs) by deep learning AIs, we can expect increasingly useful PAIs, both proprietary and open source, in the coming years. Platforms like Spotify, whose AI is uncannily good at recommending songs we may like, are narrow PAIs today. We’ll talk to and learn from increasingly generally useful PAIs, using natural language, and they will give us a variety of nudges and contextual feedback to our earbuds, AR, and devices. Such PAIs have the potential to make us, as individuals, exponentially more intelligent for the rest our lives. We’ll be able, if we desire, to learn and improve continually via our PAIs, just like we did as children.

Some proprietary PAIs will surely be both manipulative and privacy abusing, as with some digital platforms today. But we will also have community-built open source options if we don’t like the cost, terms, or ethics of the corporate versions. Security and privacy will be challenges, as with today’s software. But just as we have secure private email in the cloud, we’ll have secure private personal models in our PAIs. For the first time since the start of the Information Revolution we will be able to know and nudge ourselves better than the marketers. How will we use this new power?

Consider two popular options. In the first option, we set our PAIs to create filter bubbles, feeding us only things that confirm our biases, connecting us only to people who think like us. This is how most social networks work today—not very adaptive. In the second option, we set our PAIs to be evidence-seekers, to try to understand the world as it is, with all its conflict and diversity, and to help us interact with people whose values we don’t entirely share. Those PAI users will be the leading managers, marketers, politicians, and entrepreneurs of the future. Both paths will be taken, of course. Some of us will retreat into fantasies. Others will grow. A healthy democracy requires a majority of the latter.

“

I’m not saying that there won’t be new bubbles and crashes, or that any of these individual firms will survive, or that our central bankers and elites won’t continue to print fiat money and attempt to extract value faster than our machines can create it. Human greed and shortsightedness are perennial.

”

We can expect that PAIs that are evidence-seekers will increasingly unlearn untruthful biases, either accidentally or intentionally installed in them by their designers. We’ve already seen limited versions of this occur in the deep learners used by Google and others today. As the neural nets on which deep learners are built evolve, as they get either new neurons, new data, or new training, they develop new and more predictive algorithms. No one codes those algorithms. As with human brains, we can’t even identify exactly where they are. They emerge in the weights and architecture of the network, in the same way children gain new insights, preferences, and values in their developing brains. Algorithmic bias is a big deal in today’s AI systems, which have limited ability to self-improve. But it also appears self-correcting in any deep learner that can grow and has evidence-seeking as a central value.

Among the challenges of PAI use will be developing primitive ethics models, world models, and self-models, in systems that will be collectively smart as a network, but poorly individually intelligent, and far from empathic or conscious for decades to come. Yet when we ask how we will manage our current societal challenges of privacy erosion, digital and physical insecurity, political polarization, indebtedness, inequality, fake news, deepfakes, evidence-neglect, and declining political representation, it seems likely that PAIs will play a major role. Groups, firms, and societies will use them in widely different ways, and we’ll all be able to learn from those uses, or not, as we desire. (I have an ongoing series on Medium, Your Personal AI, exploring the future of PAIs. Please see that if you’d like more.)

This discussion of PAIs should help us recognize that exponential foresight, for all its value, is not a normative foresight model. It does not suggest adaptive goals and values, or the values trade-offs involved in social progress. It also doesn’t try to define those vital yet slippery concepts. Exponential foresight won’t tell us which technologies we should accelerate, and which we should delay, regulate, or stop using altogether, to maximize human happiness and ability.

For such things, we will need more universal models of adaptiveness, and of our most generally adaptive goals and values. To consider this question, let us return to the Three Ps, and the evo-devo worldview.

Evo-Devo Foresight—A Normative Model of Adaptiveness

In my view, we can apply evo-devo models to our universe itself if it is a self-reproducing, or autopoetic system in the multiverse, as a number of cosmologists now propose. Since all our other most intelligent complex systems are replicative, self-organizing, and subject to environmental selection for adaptiveness, it seems parsimonious (conceptually the simplest) to me to assume that evo-devo processes are how the universe self-organized its great internal complexity as well.

I think the Three Ps model, when placed in a complex systems framework as Evo-Devo Foresight, can begin to tell us things about our most adaptive goals and values, and thus help us achieve social progress. If not only life, but society, technology, and our universe can be modeled as evo-devo systems, we can use the Three Ps to propose a set of goals (programs, purposes, drives, telos) that must be balanced against each other to create adaptiveness. We can also propose tentative values that seem to spring from those goals.

As an expression of our worldview, our goals and values are at the heart of our preferences. Collectively, we use our goals and values to determine the direction, nature, and challenges of social progress. So developing potentially more universal models of our goals and values would be no small thing. Though all such models must be deeply speculative and incomplete today, I hope you will agree that the quest is worth the effort. So please consider the following hypothesis, the Five Goals of Adaptive Systems, in that light.

I posit that the leading edge, most generally adaptive individuals, organizations, and societies, as evo-devo systems, must make progress on, and resolve conflicts in, at least the following five goals:

1  Innovation (freedom, creativity, experimentation, beauty, awe, inspiration, recreation, play, fun)

Innovation (freedom, creativity, experimentation, beauty, awe, inspiration, recreation, play, fun)

2  Intelligence (information, knowledge, insight, simulated options, dimensionality, diversity)

Intelligence (information, knowledge, insight, simulated options, dimensionality, diversity)

3  Interdependence (ethics, empathy, love, equity, understanding, network connectedness, synchronization, consciousness)

Interdependence (ethics, empathy, love, equity, understanding, network connectedness, synchronization, consciousness)

4  Immunity (power, wealth, security, safety, stability, resilience, antifragility)

Immunity (power, wealth, security, safety, stability, resilience, antifragility)

5  Sustainability (truth, belief, responsibility, order, science, rationality, optimality)

Sustainability (truth, belief, responsibility, order, science, rationality, optimality)

The first two of these (1 and 2) are primarily evolutionary goals. The core purposes of evolution, one might argue, are to experiment and to survive (e.g., evolve a self- and world-model that allows survival). The last two (4 and 5) are primarily developmental goals. The core purposes of development, one might argue, are to protect the organism, and to sustain its life cycle, offspring, and environment.

Note that both of the evolutionary goals, innovation and intelligence, create diversity and disruption. Intelligence, without ethics, is a very dangerous thing. By contrast, both of the developmental goals, immunity and sustainability, protect and conserve the complexity that exists. The middle goal (3), interdependence, is an evo-devo goal. It manages the conflict between all the goals, and a rather binary set of conflicts at the heart of all collectives, between individual and group, freedom and order, creativity and truth, evolution and development.

Think of the paradox in the evo-devo phrase sustainable innovation. It requires seeking social progress in both goals 1 and 5 at the same time. Yet too strong a focus on innovation will break sustainability, and too much on sustainability will strangle innovation. Each goal is at odds with the other, yet both seem critical for any living system, any thriving organization, and any adaptive society. More broadly, we can say that growing our sustainable innovation, our immune intelligence, and our interdependence may all be key purposes of life. All of these seem central to adaptiveness.

Just as the probable is our most neglected future in current Western culture, I would argue that two of the five goals, interdependence and immunity, are understudied in complex systems research at present.

Immunity is the second most complex system in metazoan bodies, from a genetic perspective, after the brain, and is statistically great at its job, yet it remains one of the most poorly researched systems in biology and medicine. We have only just begun to borrow from biological immune systems in societal, physical, and digital security.

Many large companies develop a dysfunctional “allergic reaction” to new ideas, and many wealthy societies have an “immune rejection” of evidence that disproves their beliefs or worldview. We too often turn away from debate, discomfort, and challenge. Read Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haight’s The Coddling of the American Mind (2018) for good examples of America’ current social immune problems.

Yet our biological, societal, and technological immune systems are “antifragile.” They improve under right-sized stress. We can train away peanut allergies in our kids, rather than ban peanuts. We can increase debate and cognitive diversity in our college students, rather than ban “trigger words” and limit public speech. If we don’t continually train and expose them to challenge, our immune systems get weak and dysregulated, and start attacking their hosts. In some areas, such as our increasingly effective and continual global use of Special Forces, America excels. We live in a dangerous world, and we haven’t turned away from that danger. But we still have much to learn.

“

We must now ask: What are the limits of an exponential view of the world? What could it become, and what is it missing, by its narrowness? Such questions can help us move beyond exponentials to deeper models and alternative dynamics.

”

Fortunately, our problems of individual immunity are rarely ever true of a diverse, evolutionary network. The network always improves, even when individuals often do not. Consider the fact that all of life’s known great catastrophes, even the ones that killed the majority of individual species, have at the same time catalyzed great leaps in innovation, immunity, and complexity in life itself, and in the general adaptiveness of the survivors.

Again, the unreasonable smoothness of life’s complexity acceleration story to date suggests there is a hidden network immunity in life itself, as a diverse and redundant evo-devo community. We will need to study and learn from that network immunity if we hope to evolve more resilient, secure, privacy-protecting, and antifragile (immune) digital systems, networks, and ecosystems.

To sum up this speculation, I would like to propose that in evo-devo terms, social progress, and even the purpose of life, may be most centrally about three things: enjoying our experimental, creative, and beautiful journey (evolution), seeking and discovering incrementally more optimal and truthful destinations (development), and striving to be good (ethical, empathic, interdependent) to minimize unnecessary suffering and coercion in the pursuit of these things. Alternatively, we can say social progress requires seeking to noticeably advance these five goals, and to resolve conflicts and weigh trade-offs between them. In my view, all self-leaders and team-leaders should keep these five goals in mind, and ask themselves how to best manage them.

We can even depict the five goals as a Gaussian distribution, with interdependence as the most frequently pursued goal at the center, which helps us recognize its particular importance in our lives, firms, and societies. A British psychologist, Michael Kirton, has developed a cognitive assessment, the KAI (https://kaicentre.com/), which supports this view. Finally, we can tentatively associate a number of societal values with each goal. If we limit ourselves to two values for each goal, we get ten values that seem particularly central to accelerating adaptiveness and social progress (see Figure 10).

What this illustration proposes is that in any adaptive collective, whether a society, an organization, or a group of neural networks in a brain, interdependence, and the ethics and empathy that regulate it, is the central goal that binds the collective (the network). The ethical thoughts, behaviors, and rulesets that we use, and the empathic thoughts, feelings, and behaviors we express, are the main values that keep collectives strong. They belong at the top of our values hierarchy.

Of course, any of these goals, and their associated values, can be over- or under-expressed. Each must be managed in ways appropriate to the context. If too many social actors pursue innovation or intelligence in a collective, without regard to their wider impact, they will break that collective apart. That breakup can be desirable if the collective is no longer adaptive and we need to create new diversity, but these goals must be carefully managed.

Figure 10 • Five Goals and Ten Values of Complex Systems, an Evo-Devo Model.

Likewise, if too many actors pursue immunity and sustainability in any collective, risk aversions and frictions multiply, and that system becomes inflexible and incapable of change, and will increasingly fail when challenged by competitors or the environment. These developmental goals are good to prioritize at times, such as when we try to avert or recover from catastrophe, but again, they must be carefully managed.

When we recognize that the heart of adaptation is understanding and advancing interdependence, via better ethics and empathy, we can keep human needs and problems at the center of our foresight. If this view of the world is applied well, it should cause us to be less selfish and aggressive in pursuing our own desires, and more concerned with the needs of the group. At the same time, it should challenge us to recognize when any group is being maladaptive, or excessively interdependent, and give us the courage to oppose its unfair or perverse laws and norms, even at the cost of personal sacrifice.

“

As an expression of our worldview, our goals and values are at the heart of our preferences. Collectively, we use our goals and values to determine the direction, nature, and challenges of social progress. So developing potentially more universal models of our goals and values would be no small thing.

”

Recall that the emergence of artificial general intelligence has often been called a coming technological singularity, since mathematician and sci-fi author Vernor Vinge gave it that name in two articles in 1983 and 1993. Vinge called it a singularity because in some ways, the coming AIs will be beyond the comprehension of biological minds.

But if they must also be evo-devo learning systems, as I have proposed, their goals and values will be constrained to be a lot more predictable and similar to ours than we presently realize. These goals and values, for me, are hopeful examples of natural constraints that may improve the future adaptiveness of the network (collective) of coming AIs. If true, almost all of them may be more ethical and empathic than us, just as we are versus our distant ancestors. I don’t know if these values models are useful to you, but they have been helpful to me. I share them in that light, and look forward to your critique.

Fighting Antiprediction Bias—In Science, Work and Culture

Let us end this essay on a less speculative note—the challenge of applying the Three Ps more effectively in our academic communities, our foresight training programs, our work, and our culture. Recall that the Three Ps tell us that there are both many futures, chosen by diverse intelligences in contingent contexts, and one common future (e.g., accelerating change, universal human rights, global security, AI, air taxis, quantum computers, the end of cancer, etc.) simultaneously ahead of us. Both contingency and inevitability, freedom and determinism, possibility and probability, always coexist in tension with each other in any evo-devo system. We must learn to see both.

To do this, we will have to fight a strong antiprediction bias, in our universities, on our teams, and in society. That bias is powerful, and reform won’t happen overnight. Many of us like to believe that we can’t predict important aspects of tomorrow. But that seductive idea also prevents us from making predictive mistakes, getting feedback, and better seeing the probable future. To better see the probable, we may need to begin with the Big Picture view, and specifically, with Toffler’s idea of accelerating change.

Our modern sciences of complexity, which emerged in the 1980s, seem the ideal place for the emergence of an interdisciplinary academic approach to the study of accelerating change. Leaders at the Santa Fe Institute, a leading US complexity community, tried three times in the last decade (2009-2011), to get a small Performance Curve Database funded by the NSF. They proposed an open repository of exponential technology performance curves, with data solicited from a variety of academic and industry silos. Unfortunately, even this modest predictive project remains unfunded.

“

Many of us like to believe that we can’t predict important aspects of tomorrow. But that seductive idea also prevents us from making predictive mistakes, getting feedback, and better seeing the probable future.

”

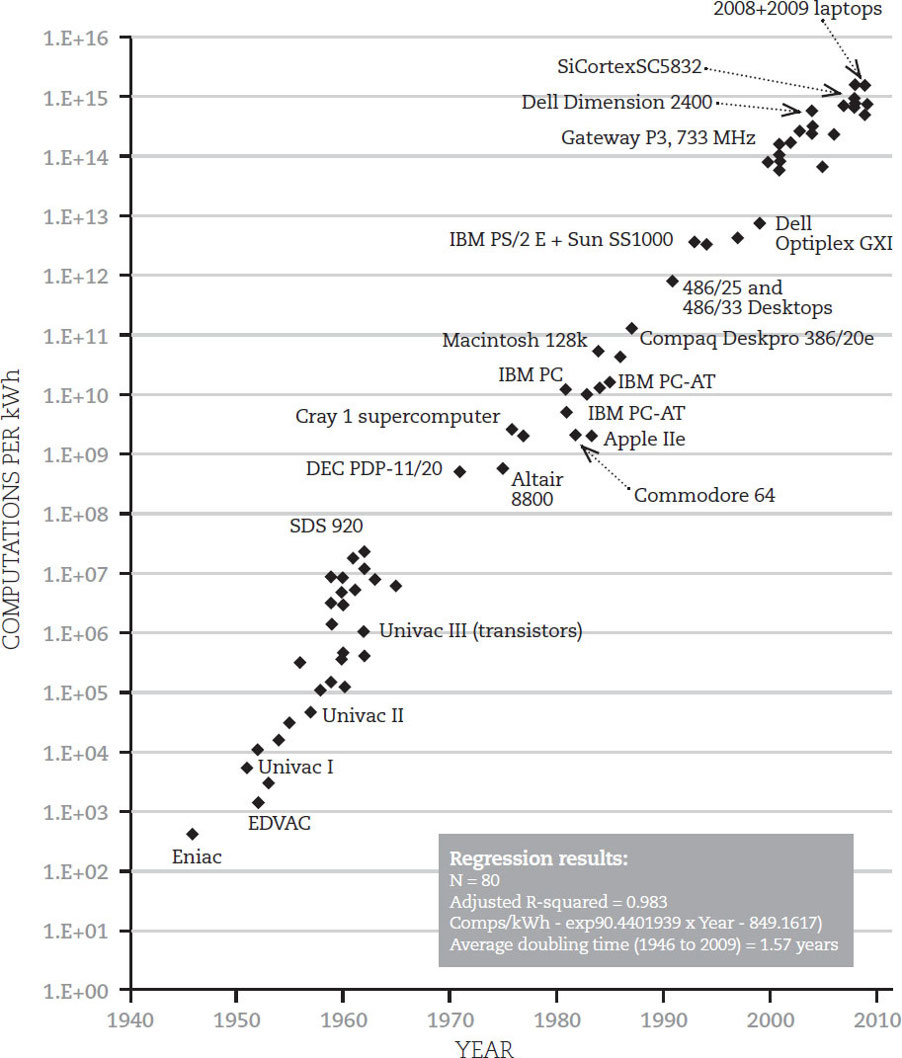

What kinds of curves would such a database collect? Most obviously, a variety of “generalized” Moore’s laws. Moore’s Law is a doubling in price performance of semiconductor computing technology roughly every two years, a phenomenal acceleration that has persisted since the early 1960s. Moore’s Law began to slow (slightly) with the end of Dennard scaling in 2005, and several industry leaders predict a 2020’s limit to transistor density. Some have used this fact to mistakenly conclude that computational densification is slowing down. But in reality, the slowing of Moore’s Law for CPUs has allowed other exponentials, first in multicore chips, then in GPUs (powering deep learning since 2010) and now in TPUs (a new class of chips specialty built for deep learners) to gain traction. These new computing paradigms became economically possible only once CPUs slowed their rapidly exponential annual shrinking rates. In other words, their development was regulated by the previous hardware paradigm.

Though GPU and TPU exponentials are slower today than Moore’s Law (a 2018 study by the Median group found a recent price-performance doubling of 3.5 years) these new machines have a far more massively parallel, bio- and brain-inspired nature. Their performance improvements come not primarily from circuit miniaturization (the last paradigm), but from exponentiation of circuit parallelism and associational complexity (the next paradigm). The growth of such complexity needs to be measured. It may be more rapid than Moore’s Law. Ray Kurzweil, in this volume, proposes that since 2012, neural network complexity has been doubling every 3.5 months. A 2010 TF&SC study by Bela Nagy et al. concluded that information storage, transportation (bandwidth), and transformation (speed of computation), when plotted with data since the late 19th century, are actually not exponential, but superexponential. Doubling times for all three of these functional tasks have been decreasing. With models of accelerating change, what is measured is as important as the time scale over which it is measured.

We also need a much better understanding of algorithmic efficiency improvements in software, an area where there presently is significant lack of clarity. For example, a 2019 Economist special report on supply chain automation notes that deep learning demand forecasting and replenishment algorithms developed by Blue Yonder, a German startup, have “reduced out-of-stock items by 30% and cut inventory needs by several days” at Morrison’s, a British grocery chain. But what exactly is the performance improvement here, and what resources (physical, informational, monetary, time) were needed in the old and the new system? Again, what is measured is as important as the time scale over which we measure.

Figure 11 • Koomey’s Law showing computers using half as much energy per computation every 1.6 years.