Moore’s Law—the Mechanism of Future Shock?

Carver Mead

The phenomenon of a rapidly advancing future—the central thesis of Future Shock—can be explained, at least in part, by Moore’s Law—the principle that describes the exponential nature of transistor scaling over time.  This deceptively simple observation has had a tremendous impact on modern society—perhaps more so than that of any other foundation technology. Indeed, the remarkable advances in semiconductor fabrication processes are precisely what have fueled the attendant explosion in technology, which in turn has accelerated the pace of progress. And it started out quite simply: Gordon Moore asking me a question.

This deceptively simple observation has had a tremendous impact on modern society—perhaps more so than that of any other foundation technology. Indeed, the remarkable advances in semiconductor fabrication processes are precisely what have fueled the attendant explosion in technology, which in turn has accelerated the pace of progress. And it started out quite simply: Gordon Moore asking me a question.

It happened early in 1965. At that time, while a professor at Caltech, I was also consulting for Fairchild—the seminal semiconductor company that pioneered the integrated circuit. In those days, I would fly in the night before and spend my consulting day in Palo Alto, where Fairchild was headquartered. On one such occasion, I walked into Gordon’s office and he said to me, handing me a handwritten plot, “What do you think of this?”

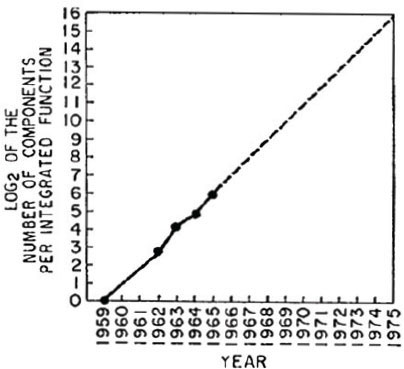

It was a figure depicting the increasing complexity of silicon chips over time. He had plotted one point for each year and put a line through them, extending the proposed exponential trend with a dotted line up and to the right—into the future. This was his big idea, to which I simply said, “Wow, that’s pretty neat!”

He then asked me about my work on a phenomenon called electron tunneling. It happens when certain transistor feature sizes get so small that the semiconductor physics begin to break down. “Won’t that limit how small you can make a transistor?” he asked. I answered, “Yes, it certainly will.” To which he probed, “How small?”

That was the beginning of what came to be known as Moore’s Law. But the concept immediately hit a headwind. In short, nobody believed the plot could be true. All the experts produced myriad reasons why we couldn’t make transistors as small as the curve required. Maybe, they’d say, we’d be able to achieve another factor or two, but then this or that or some other physical process would preclude any further progress. It was, to say the least, a tough sell.

Gordon was pushing the economics of it, because if you could make them that small, it would change the world. So we had to go back and work out the details to prove that the physics weren’t going to get you if you did it right. We spent the next 10 years fighting that battle.

What’s more, people at the time assumed that as you scaled the transistor feature sizes down, and the device density higher, the power density would go through the roof. But part of the scaling was to decrease the power supply voltage as the devices got smaller. With that kind of scaling, the transistors actually became better, faster, smaller, and cheaper, and the power density per unit area remained constant! The resulting computation per unit energy grew as the third power!

It wasn’t until I gave a talk on this subject at a device physics workshop in 1968 that we got the first glimmer of acceptance. One of the people in attendance was Bob Dennard, a prominent researcher at IBM. Bob invented the modern version of the dynamic RAM (DRAM). And while the people at the conference were giving me a terribly hard time, I could see that Bob was actually thinking about it. Then a remarkable thing happened.

The popular perception of Moore’s Law is that computer chips are compounding in their complexity at near constant per unit cost. The history of technology is one of disruption and exponential growth, epitomized in Moore’s law, and generalized to many basic technological capabilities that are compounding independently from the economy. Each horizontal line on this logarithmic graph represents a 2x improvement, and hence, a new chapter in the human drama.

Source: Cramming More Components onto Integrated Circuits, Electronics, Volume 38, Number 8, April 19, 1965, pp.114.

At the same conference a year later, Bob presented his own version of a scaling law, which became known as Dennard Scaling. And, not surprisingly, it tracked well with our scaling. The difference? We now had an “industry guy” endorsing the idea, and bestowing upon it the IBM imprimatur, and thus, respectability.

Now, in looking back at the actual progress achieved, it’s helpful to appreciate that we had made a rather audacious prediction—that transistors could be made as small as .15 microns. The resulting chip area for a given function would be nearly a thousand times smaller than required at the time. The simplifying assumption of our work was that all we would do was to shrink all the dimensions—and do nothing different with any other aspect of the design. Under that constraint we would start getting into trouble below .15 microns. At that point, we’d have to start getting fancy with new materials and device geometries, which, of course, at that time were still a distant dream. We hit that .15 micron mark in the year 2000, and it was, in fact, the hinge. After that, we did, indeed, have to get fancy. Using new device geometries and exotic materials, the industry has managed to blow by that projected limit by an order of magnitude (factor of 100 in area).

“

The rapidity of evolution of technology has made the competitive landscape such that the people who just did the next thing faster won out over whose who looked further into the future. And this, of course, ushered in the era of continual disruption-indeed a shocking event for the disrupted.

”

Now, as to why this matters, George Gilder answered it best when he said, “The question that occurred to me was whether Moore’s Law was just another learning curve. The learning curve is one of the most thoroughly documented phenomena in all technology and business, and it ordains that with every doubling of total units, you get a corresponding 20 to 30 percent drop in costs. Consequently, learning curves are projected into the whole economy. And learning curves are the most fundamental fact in capitalism—with Moore’s Law being the most important of them all.”¹

Interestingly, it turns out that Alvin Toffler, writing in Future Shock, did not mention Moore’s Law specifically, but he certainly described its effects—and in particular, a certain shadow side. “Advancing technology,” he wrote, “makes it possible to improve the object as time goes by. The second generation computer is better than the first and the third is better than the second. Since we can anticipate further technological advance, more improvements coming at ever shorter intervals, it often makes hard economic sense to build for the short term rather than the long.”

The latter part of that statement is the particularly insightful one. In my experience it has become less common for companies to build for the long haul than it was 50 years ago, when most companies had forward-looking research labs. It’s not happening nearly as much today. Indeed, the short-term competitive nature of things has gotten increasingly aggressive. The rapidity of evolution of technology has made the competitive landscape such that the people who just did the next thing faster won out over whose who looked further into the future. And this, of course, ushered in the era of continual disruption—indeed a shocking event for the disrupted.

Over the past 20 years, the people who were looking for entirely new technologies were consistently beat out in the marketplace by the people who just used the next generation Moore’s Law. Simply making the faster microprocessor and the faster memory at lower cost meant you’d displace anybody who was trying to look beyond that.

But with the apparent slowing down of Moore’s Law comes the question of a possible change in the nature of whether it pays to look further, or not. While we live in what’s being characterized as an exponential age—a time of exponential technology evolution—it might strike some as paradoxical that Moore’s Law—the exponential curve that started it all—is slowing down. What I’ve observed, however, is that people are applying what are not very rapidly evolving technologies to new applications at a very rapid rate. That’s largely the way innovation has been going. So we see an exponential increase in taking advantage of what is becoming a very stably evolving technology. And if you survey the applications that have grown out of that approach, we wouldn’t have imagined even a tiny fraction of them.

“

While we live in what’s being characterized as an exponential age-a time of exponential technology evolution-it might strike some as paradoxical that Moore’s Law-the exponential curve that started it all-is slowing down.

”

But there’s another important aspect to Moore’s Law that is the least talked about, and yet, in a sense, is perhaps the most important. The “Moore’s Law thing” is really about people’s belief in the future, and their willingness to put energy into causing something to come about. It is, in fact, a marvelous statement about humanity. And indeed, the idea of Moore’s Law progressed from nobody believing it was possible to the idea that it could take the rest of a person’s working life to fully realize it.

It’s true that most truly new technologies encounter an energy barrier to overcome: it takes a great deal of time and effort and energy for new ideas to get into the belief system of a culture. And if you don’t make that effort, you simply won’t get there.

It’s also true that every time there has been a major technological advance, everybody cried, “This is going to be the end of society as we know it.” Today we’re seeing that with the advent of deep learning systems. But we’ve always seen exactly the opposite through history. Still, almost every one of these new technologies has been resisted. There is some truth to Max Planck’s quip that science proceeds one funeral at a time!

Notwithstanding, we’ve also learned that there is a kind of a philosophy of possibility. I always had to explain that, while Moore’s Law is grounded in physics, it’s really not a law of physics—it’s a law of the way that humans are. In order for anything to evolve like our semiconductor technology has evolved, it takes an enormous amount of creative effort by a large number of very smart people. They have to believe that the effort is going to result in a successful thing, or they won’t put the effort in. The belief that it’s possible to do a thing is what causes the thing to happen. But you need two things going in: 1) the belief that what you’re envisioning is possible; and 2) the belief that if you do it, it’ll make a big difference.

By the time this idea became Moore’s Law, we had gotten past the major obstacles to belief. And Gordon Moore had made the absolutely compelling case that if you could do it, it would transform not only the industry, but the world. There was never a question about that in his mind. But there were a lot of questions about whether it was possible. That’s what we had to get past. And as we now know, Gordon was very successful in getting people to believe that it was worth doing. Like the Tofflers, he got there long before many of us did.

Carver Mead is an American scientist and engineer. He currently holds the position of Gordon and Betty Moore Professor Emeritus of Engineering and Applied Science at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), having taught there for over 40 years. His contributions as a teacher include the classic textbook Introduction to VLSI Systems (1980), which he coauthored with Lynn Conway. A pioneer of modern microelectronics, he has made contributions to the development and design of semiconductor devices, digital chips, and silicon compilers, technologies that form the foundations of modern very-large-scale integration chip design. In the 1980s, he focused on electronic modeling of human neurology and biology, creating “neuromorphic electronic systems.” Mead has been involved in the founding of nearly 30 companies. Most recently, he has called for the reconceptualization of modern physics, revisiting the theoretical debates of Niels Bohr, Albert Einstein, and others in light of modern experiments.

1. The Caltech Sessions: In Conversation with Carver Mead and George Gilder, Abundant World Institute.

This deceptively simple observation has had a tremendous impact on modern society—perhaps more so than that of any other foundation technology. Indeed, the remarkable advances in semiconductor fabrication processes are precisely what have fueled the attendant explosion in technology, which in turn has accelerated the pace of progress. And it started out quite simply: Gordon Moore asking me a question.

This deceptively simple observation has had a tremendous impact on modern society—perhaps more so than that of any other foundation technology. Indeed, the remarkable advances in semiconductor fabrication processes are precisely what have fueled the attendant explosion in technology, which in turn has accelerated the pace of progress. And it started out quite simply: Gordon Moore asking me a question.