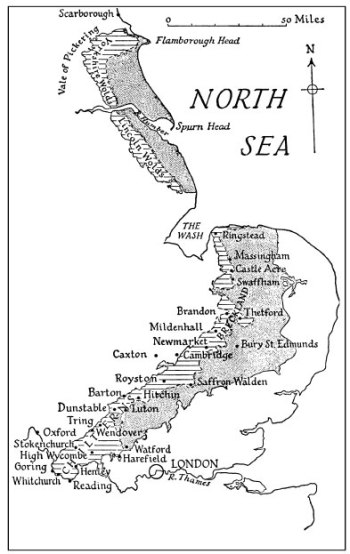

CHALKLANDS NORTH OF THE THAMES

![]()

THE THAMES between Reading and Goring forms a natural boundary between two very different types of chalk country. The Berkshire downs considered in the last chapter stretch away to the south-west and merge into those of Wiltshire. Characteristically these are open, treeless, sheep-grazed pastures. The Chilterns, on the other hand, which extend to the north-east, are heavily wooded except on the steeper slopes. They include some of the finest beechwoods in England, and although many of these are on superficial deposits over the chalk, they add welcome variety to the flora. Moreover, the downland turf itself, in my experience, is less uniform, and this, speaking very generally, is probably attributable to less intensive grazing. Although the area of chalk exposed at the surface is perhaps less than on Salisbury Plain and its outliers, the flora is more attractive.

THE CHILTERNS

On the higher ground of the Chilterns the chalk is often covered with patches of Clay-with-Flints, brickearth and gravels, and the vegetation usually indicates these very clearly to the observant eye. This, however, is not always the case in beechwoods. The beech, Fagus sylvatica, forms magnificent woods on well-drained soils other than on chalk, and the accumulation of leaves creates its own environment to suit certain plants irrespective of the underlying rock. On the other hand, the fine escarpment facing west, and later north-west, which extends from Whitchurch and Goring on the Thames to Stokenchurch, Princes Risborough, Wendover and Tring and beyond, provides a steep slope on which only a thin soil covers the chalk-rock. Here many of the finest chalk flowers are to be found.

Two of the most characteristic rare flowers of this escarpment are the Candytuft, Iberis amara (Plate 18), and Large Autumn Gentian, Gentianella germanica (Plate 25). Both of these occur in greater quantity than anywhere else in Britain. Both favour rather bare and very chalky soils. The Candytuft grows on open places on the hill slopes and also in clearings in the woods and cultivated fields. On the Chilterns it is certainly native, but in most other districts it is either an obvious introduction or doubtful. The Large Autumn Gentian is likewise at home on the open slopes and is occasionally found in woods.

The beechwoods are the homes of rare orchids. One of these, the Spur-lipped Coralroot, Epipogium aphyllum, has been described as our rarest British plant. It has been found in this country only in three small areas, two on the Chilterns, and the other near Ludlow, and is so intensely scarce that you could search unsuccessfully for years. It is a curious and fascinating plant, living like the Bird’s-nest Orchid, Neottia nidus-avis, and Yellow Bird’s-nest, Monotropa hypopitys, on the decaying remains of dead leaves. Flowers appear only at long intervals, and even when the exact locality at which they have been found is known, it may be very many years before search is rewarded with success. It has been seen in at least three places, many miles apart in the woods of the Chilterns, and on several occasions. The recorded dates range from May to August, so evidently it has an exceptionally long flowering season.

The Chiltern wood borders are the place to look for the Military Orchid, Orchis militaris. At one time this was not extremely rare, and up to about a century ago there are records of it being seen in considerable numbers. Moreover, the records extend from east of Tring across the Thames into Berkshire; and they were from places well scattered over the Chilterns (Distribution Map 13). Then it disappeared from one district after another, until by about 1914 it seemed to be extinct. Whatever the reason for its going—and there are quite a number of theories—there must have been some factor which affected it over a wide area. In May, 1947, I rediscovered the Military Orchid! In a way it was just luck. The excursion was intended as a picnic, so I had left my usual apparatus at home and took only my note-book. But I selected our stopping places on the chalk with some care, and naturally wandered off to see what I could find. To my delight I stumbled on the orchid just coming into flower. The following week-end I returned to make a careful survey of the colony and to take the first opportunity given to any British botanist for well over thirty years of studying the particular conditions under which the Military Orchid lives in our country. It was on this second visit that I took the colour photograph used for Plate 26—the first to be taken of this plant in England.

Careful plotting showed that there were 39 plants in the colony and that 18 of them had thrown up flowering spikes. Of these, the 5 most exposed had the flower-stems bitten right off—almost certainly by rabbits. The plotting also revealed that the plants most in shade either failed to flower or put up only pale, small spikes. Trees on one side of the colony had been cut down in the early days of the war, as I estimated from the growth of bushes round their stumps, and it is likely that this had stimulated germination of dormant seeds of the orchid. Analysis of a sample of the soil revealed that the free carbonate of lime amounted to no less than 50.2 per cent—an astonishingly high proportion.

It was interesting to compare this locality with the marshes near Brunnen in Switzerland, where I saw the Military Orchid in May, 1930. Whereas on the Chilterns it was growing on a shallow chalk soil under almost the driest possible conditions, in Switzerland it thrived in very wet marshy meadows. It is probable, however, that the soil-water there was basic, although I made no tests at the time.

The plants on the Chilterns varied greatly in size. The smallest was only about four inches tall with two flowers—a miserable, depauperate little plant. The largest—the one which is illustrated—was 14 inches (35 cm.) tall with no less than 26 flowers. This must be about the finest Military Orchid seen in England; for most of the herbarium specimens (dating from the time when it was plentiful) are only some 7 to 9 inches in height.

The flowers are extremely beautiful; in saying this I think I can fairly say that I have not allowed the rarity of the plant to bias my judgment. The pointed sepals are folded together to form a hood over each flower and are a pale ashy-grey on the outside. The flowers open at the bottom of the spike first and therefore the buds at the top appear slightly pinkish-grey from the colour of the sepals, which act as wrappers. It is the resemblance of the hood to an ancient helmet which has led to the plant being called the Soldier or Military Orchid; the name is a very apt one. The lip, which projects beneath the helmet, has two lobes on each side and one very small pointed terminal one: it is spotted and flushed with a colour which is usually described as pink but which is far less red than is shown in most of the published colour pictures. It is a colour which is very difficult to match, but perhaps comes nearest to the one described as “roseine purple” of the old R.H.S. colour chart. In 1955 a second fine colony of the Military Orchid was discovered in Suffolk—far from previously known habitats.

The Monkey Orchid is now less rare so far as numbers are concerned. The best known locality is a tiny area of down on the Chilterns, and for many years this was a secret shared by a considerable number of botanists who visited it annually. They kept the secret so well that in 1943 a paper was published in a scientific journal recording its “rediscovery” although, in fact, the plant had never been lost! Unfortunately the numbers have been reduced considerably by the ploughing of the lower part of the habitat, and increase of the downland scrub. As the bushes were fast making the down unsuitable, a party of public-spirited botanists now make an annual visit in winter to clear away the scrub, and there are already indications that the orchid may be increasing. There are old records from several parts of Kent but for a time the Monkey Orchid was thought to be extinct in the county. Then in 1952, a single plant reappeared, and flowered in each of the next three years. Shortly afterwards it was refound in greater numbers in another part of the county, and here Mr. H. M. Wilks has taken active steps to conserve it and his efforts seem likely to be successful. In Sussex and Berkshire the orchid appears to be extinct, and there are doubtful records from Surrey.

The Monkey Orchid flowers about a week earlier than the Military Orchid. It shares with this species, the Lady Orchid, O. purpurea, and the Man Orchid, Aceras anthropophorum, the possession of coumarin in the leaves. On account of this the drying foliage emits a strong and very pleasant smell resembling new-mown hay. The resemblance of the lip to a monkey is clear. Like the Man Orchid, it is chiefly a plant of the open downs, while the Military and Lady Orchids are generally characteristic of woods and wood borders.

Before leaving the orchids there is one more species which should be mentioned. The Green-flowered Helleborine, Epipactis leptochila, is, as far as my own experience goes, far more common in the Chilterns than anywhere else. In the beechwoods within easy access of Henley-on-Thames it is quite a common plant. It flowers a little earlier than the allied Broad-leaved Helleborine, E. helleborine, from which it differs in having yellow-green flowers, with longer and more pointed sepals and petals and in other characters.

In the same district the Cut-leaved Self-heal, Prunella laciniata, has recently been discovered in two places. It will be discussed in a later chapter.

The beechwoods of the Chilterns are not only more extensive than those of the North and South Downs, but they also differ somewhat in their associated flora. For example, the handsome grass Wood Barley, Hordelymus europaeus, is relatively frequent. I have seen it in various places between Tring and Henley forming fine colonies in the lighter parts of the woods. Similarly the Lesser Wintergreen, Pyrola minor, with its lovely cream-coloured bells of flowers, is fairly frequent in isolated patches in the extensive woods of the Chilterns. On the whole of the North and South Downs I can remember only one record for this plant, though in Surrey, Kent and Sussex it occurs on sandy or boggy soils in a few places. There is thus a great contrast in behaviour. Then again in some of the Chiltern woods there is a display of Hawkweeds, Hieracium spp., such as we never see on the North and South Downs. In these three respects the resemblance of the flora is to that of the beechwoods of the Cotswolds rather than to the chalk hills farther south.

Within a limited area roughly bounded by High Wycombe and Amersham, Watford and Harefield, the Coralroot, Cardamine bulbifera, is locally common. It also occurs just across the Thames in Berkshire. It is a plant with a surprisingly short flowering season, being at its best for less than a week during May. I have never seen fully-formed fruit of Coralroot, which must be uncommon, and the plant evidently depends mainly for reproduction on bulbils, which form in the axils of the leaves. The woods where it grows are on chalk, but it does not follow that the soil is always chalky. In fact I have seen it in some places on soil which was almost certainly somewhat acid.

East of the Colne there are small areas of chalk in Middlesex; the best and most famous of these is near Harefield. Here, within 16 or 17 miles of London, chalk flowers persist, and Mr. D. H. Kent has been successful in refinding many of those recorded by Blackstone over two centuries ago. The Military Orchid was seen in this district at the beginning of this century.

HERTFORDSHIRE AND BEDFORDSHIRE

The escarpment of the Chilterns is continued across Buckinghamshire and a small corner of Hertfordshire, near Tring, into Bedfordshire. One locality for the Pasque Flower, Pulsatilla vulgaris (Plate X), in this district has received a good deal more than its fair share of publicity. It is not only well known to local country people and to visitors, but on at least two occasions has been the subject of letters to Sunday newspapers. There are several places where the plant is more plentiful. A little beyond Tring are the last of the big beechwoods and, farther east, I remember only comparatively small copses and belts of beech. It is perhaps for this reason that the Military Orchid has never been found farther east on these hills than Aldbury.

Just east of Tring is thus the approximate position of a change in the character of the flora. Not only does it mark the end of the fine Chiltern beechwoods, but also the beginning of certain plants of a more eastern distribution. A good example is the Great Pig-nut, Bunium bulbocastanum. This plant has been found in Britain only in contiguous parts of Hertfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire, and it occurs locally in great abundance. Yet it is as adaptable to quite a wide range of different habitat conditions. I have seen it equally at home in the dense downland turf and in arable fields, on shallow chalk soils and in deep marl. As a weed in cereal crops its deep “bulbs” are so much below the surface of the soil that they are hardly disturbed by ploughing. In downland turf it is apparently able to compete with the grasses. From near Cambridge almost to Tring there are areas where the plant is to be seen in countless thousands, and yet it has never spread beyond these limits.

Purple Milk-vetch, Astragalus danicus, which is absent from the Buckinghamshire Chilterns, has a number of localities on the chalk to the east of them. Field Fleawort, Senecio integrifolius, becomes more frequent. These are plants which are chiefly associated with the drier chalk areas.

Along the hills which extend north-east from the Chilterns the best places for chalk flowers are, as usual, on the hill slopes. These are found on the steep escarpment which, in contrast to that of the North Downs, faces north. Much of the chalk on the flattish top is covered with other soils. The escarpment in places forms fine promontories which project into the lower ground to the north, while intervening bays form great sheltered amphitheatres. Pitstone Hill and Ivinghoe Beacon and the slopes between them are of great interest. Near Dunstable the best places are Dunstable Downs and Blow’s Downs on the higher ground, and the much quarried country east of Castle Hill, Totternhoe. The famous philosopher and economist, John Stuart Mill, was one of the first to point out that the Box, Buxus sempervirens, was to be found on the hills between Dunstable and Tring. Here, as at Great and Little Kimble farther west, it is usually regarded as having spread from trees which were originally planted; but the matter is not beyond doubt.

Beyond Dunstable the north-facing escarpment forms a magnificent range from Sundon through the Barton and Pegsdon Hills almost to Hitchin. Here I have seen Purple Milk-vetch and Field Fleawort in abundance, while at one spot Mountain Stone Parsley, Seseli libanotis, Pasque Flower, Pulsatilla vulgaris, and Spotted Catsear, Hypochoeris maculata, all grow together. The flowers of the latter are often eaten off by cattle. In two localities on the range Upright Cinquefoil, Potentilla recta, is naturalised. Elsewhere in the district there was until recently a fine colony of Lizard Orchids, Himantoglossum hircinum. It has been known in the vicinity since 1938, and in 1947 I saw 23 plants. When the photograph reproduced on Plate 27 was taken in 1946 there were even more, but it seems likely that the orchids suffered from the severe weather early in 1947 and from the drought which followed. Ploughing then destroyed the colony.

CAMBRIDGESHIRE

East of Hitchin there is no continuous chalk escarpment, though in a few places such as Therfield Heath, near Royston, there are slopes sufficiently steep to have discouraged ploughing. In general, however, the chalk is heavily cultivated and it is only on earthworks and in narrow strips by tracks and round quarries that the old downland turf still remains. This destruction of the native plants doubtless took place at a rapid rate in the eighteenth century, but it was in the early part of the nineteenth century that successive Enclosure Acts resulted in loss on a grand scale. It led to the complete extinction of some of the recorded plants and greatly reduced the number of localities of others.

Professor Babington of Cambridge was able to observe the closing stages of the worst of this destruction at first-hand. Referring to the Cambridgeshire chalk country, he wrote :

“Until recently (within 60 years) most of the chalk district was open and covered with a beautiful coating of turf, profusely decorated with Pasque Flower, Purple Milk-vetch, and other interesting plants. It is now converted into arable land, and its peculiar plants mostly confined to small waste spots by roadsides, pits, and the very few banks which are too steep for the plough. Thus many species which were formerly abundant have become rare; so rare as to have caused an unjust suspicion of their not being really natives to arise in the minds of some modern botanists. Even the tumuli, entrenchments, and other interesting works of the ancient inhabitants have seldom escaped the rapacity of the modern agriculturalist, who too frequently looks upon the native plants of the country as weeds, and its antiquities as deformities.”1

This was published in 1860, and at this distance of time it is difficult to appreciate the magnitude of the change which took place over the chalk of the adjoining parts of north Hertfordshire and Essex and southern Cambridgeshire.

It is in the records of the rarer plants that the destruction of the downland flowers can be traced. An example is the Early Spider Orchid, Ophrys sphegodes (Plate 31), which has already been referred to in Chapter 5. Gibson still knew it on chalky banks near Hildersham in 1842, and it is believed that he found it on the baulks left between arable fields. These were destroyed by more intensive cultivation. Babington found it on a baulk near Abington on 24 May, 1837, but three years later he found that someone had “dug up all the plants.” There were vandals even in those days! But these records seem to have been the very last chapters in the story, and although the Early Spider Orchid was probably never plentiful in Cambridgeshire, it is fairly safe to say that the last known localities were merely those which had dodged the plough longest.

FIG. 7

Chalklands north of the Thames. Upper Cretaceous (Chalk) hatched where at the surface and stippled where covered by Glacial Drift

The history of the Pasque Flower is rather similar. It still persists on earthworks and other places where it has been protected from the plough. But many of its haunts have been lost and the baulks between fields where it was known to botanists of a century ago have long been destroyed. The Purple Milk-vetch can now be found at very few of the spots given in the old floras. Field Fleawort—which Relhan called Cambridge Ragwort—may well be another example of a flower which was once much more common.

The ploughing up of the downland has not been all loss. In the chalky arable fields which took its place many interesting weeds characteristic of this part of East Anglia are to be found. Perhaps the most general of these are three small-flowered Fumitories, Fumaria micrantha, F. parviflora and F. vaillantii. There are also rare Poppies. The Rough Round-headed Poppy, Papaver hybridum, with dark crimson petals, each with a purplish-black patch at the base, seems to be more common than it was a century ago. On the other hand, Lecoq’s Poppy, P. lecoqii, with its headquarters for Britain here, is much rarer. The Larkspur, Delphinium ambiguum, which was for a time rather widespread in chalky fields, is now almost if not quite gone in such places. The Greater and Lesser Bur-parsleys, Caucalis latifolia and C. platycarpos, are both now very rare, though I saw a fair quantity of the latter in 1947 and 1948. Such changes are due to improved cultivation and cleaner seed. On the credit side we have Madwort, Asperugo procumbens. This had not been recorded in Cambridgeshire for over two centuries until refound on the chalk about 1927. In a field, which adjoins one where Professor Babington made a special study of the Fumitories many years earlier, it varies in quantity from season to season according to the weather and the crop. It is an annual which completes its life-cycle in a very short period, and usually a few plants appear in May and a much larger number after the late summer rains. During the dry middle of the summer I have found it completely burnt up.

Fortunately a considerable number of rare downland plants still occur on the small patches which escaped the ploughing. One of these is Mountain Everlasting, Antennaria dioica, which is common enough on the wetter limestone of the north and west, but exceedingly scarce and erratic in appearance in the south and east of England. It was found on a heath near Royston about 1841, and a note made about the same time says that there was only a square yard of it. Later it was noticed in two places in the same district, and in 1882 it is known to have flowered freely. After this I can trace no further records for 65 years until, in 1947, it was rediscovered by Mr. Donald Pigott. During the 1939–45 war a large part of the down had been ploughed but the place where it grows had been left alone.

Another remarkable survival is the Tuberous Thistle, Cirsium tuberosum, which owes its protection to a very ancient trackway. It is restricted to a very small area where it was discovered by Dr. W. H. Mills in July, 1919. Between the two world wars it spread out into the adjoining chalky fields, but when these were again taken into cultivation early in the second war, the Thistle once more became limited to the edge of the trackway. Along hedge-banks and field borders on the Gog Magog hills there are two pretty bulbous plants: the Grape Hyacinth, Muscari atlanticum, and Common Star-of-Bethlehem, Ornithogalum umbellatum. They are both grown in gardens but the first is almost certainly native and the second has been there for a very long time. Another very beautiful plant which is one of the features of these hills is the lovely blue-flowered Perennial Flax, Linum anglicum. It has been known from Newmarket for three centuries, but even on the Gogs, which is the place where most people go to see it, the plant is local. From north Essex it is to be found in scattered localities on the chalk and limestone right up the eastern side of England to Durham, and then, rather strangely, it reappears on the limestone to the west in Westmorland and also in Kirkcudbrightshire.

It is on the Gogs that the Mountain Stone Parsley, Seseli libanotis, and Great Pig-nut, Bunium bulbocastanum, grow within a few yards of one another. In the downland turf by the Roman Road over the Gogs, and on the Devil’s Ditch near Newmarket, there is a very rare little sedge, Carex ericetorum, which is not easy to find. These are the only two places where I have seen it in Cambridgeshire, but in Breckland, shortly to be discussed, it is certainly more plentiful, and it has been discovered on the limestone farther north. On chalk in this county I was shown Spiked Speedwell, Veronica spicata (Plate XI), in 1947, in a place which may well be the same as one where John Ray found it in the seventeenth century. The flowers are of a most intense blue, and although there are several localities for it in Norfolk and Suffolk (Distribution Map 11), the plant is much more scarce than its western subspecies, V. hybrida. In a few places I have seen the spring Cinquefoil, Potentilla tabernaemontani, but it is here usually much smaller than in the limestone districts of western England with their heavier rainfall.

Some mention must be made of the Boulder Clay, which in places contains a considerable proportion of lime. It is a glacial deposit derived from rocks which have been crushed by ice and contains a heterogenous mass of material. Where it overlies the chalk it often contains boulders of chalk and flint, and the flora includes a number of calcicoles. Boulder Clay occurs widely over England and, although it is only marked on the “drift” (and not on the “solid”) editions of the geological maps, it is of considerable importance to the botanist. The best known areas are to the north-west and south-east of the Cambridgeshire chalk, around Hardwick, Caxton and Eversden, and from Saffron Walden and Quendon towards Haverhill respectively.

The most characteristic flower of the Boulder Clay is the Oxlip, Primula elatior. In very general terms this has flowers rather like those of a Primrose, P. vulgaris, carried at the end of a long stalk like those of the Cowslip, P. veris. A hybrid between the last two species is not uncommon in some parts of the country, and this hybrid or False Oxlip is sometimes confused with the true Oxlip, which is restricted to the Eastern Counties. In many of the woods on the Boulder Clay the latter occurs in the greatest abundance—a most beautiful sight when in flower in April. It sometimes hybridises with Cowslip and also with the Primrose. In Britain the species is restricted to this particular kind of clay.1 Another characteristic plant of these woods is the Crested Cow-wheat, Malampyrum cristatum, with handsome red and yellow flowers recalling those of the Field Cow-wheat, Melampyrum arvense. It is strangely local in its occurrence and prefers the edges of woods and open rides. After coppicing it sometimes appears in great quantity, only to decrease as the bushes grow up again.

Sulphur Clover, Trifolium ochroleucon, is locally abundant on field borders and roadsides on the Boulder Clay, though it also occurs on chalk. In the cultivated fields a number of uncommon weeds are probably more frequent here than anywhere else in England. These include Slender Tare, Vicia tenuissima, Warty Spurge, Euphorbia platyphyllos, and a rare Brome-grass, Bromus arvensis.

BRECKLAND

Commencing near Chippenham, a few miles beyond Newmarket, and extending through Mildenhall to north of Brandon, east of Thetford, and nearly to Bury St. Edmunds, is a fascinating area known as “Breckland.” Here a layer of sand overlies the chalk, and this has given the district a wild and unique character. Many rare plants are to be found, and a holiday spent at any of the towns mentioned will provide plenty of interest for the botanist.

Over a great part of the Breck the wild flowers are sand-loving species and often plants which avoid lime. But here and there the sand is thin, and chalk is very close to the surface. It is in such spots that the vegetation is most varied and that most of the rarer plants are found. These places can usually be recognised by the presence of chalk-pits which have been dug there because it is more economical to dig chalk where the sand is thin rather than where it is deep. Round these pits the sand looks the same as elsewhere, but it contains an appreciable percentage of calcareous matter. Many of the plants are lime-lovers.

Some of the plants I have seen in such places are certainly calcicoles, such as Burnt Orchid, Orchis ustulata, Purple Milk-vetch, Astragalus danicus, Spring Cinquefoil, Potentilla tabernaemontani, Spiked Speedwell, Veronica spicata, and a Meadow-rue, Thalictrum babingtonii. All these are true chalk plants in Cambridgeshire, which has just been discussed. But I strongly suspect that a good many other species which grow here are likewise calcicoles although there is less certainty about them. Examples are Grape Hyacinth, Muscari atlanticum, and Common Star-of-Bethlehem, Ornithogalum umbellatum, which both occur over considerable areas of Breckland sand. Similarly the rare sedge, Carex ericetorum, which I have only seen here and in Cambridgeshire and Yorkshire on limestone soils, may perhaps not be restricted to them as my experience would indicate. Then Spotted Catsear, Hypochoeris maculata, which is always on chalk in the Eastern Counties and on limestone in the north-west, does occur in Cornwall in a place which may not be calcareous. Again, the dainty little Spanish Catchfly, Silene otites, which I have seen on chalk in north Norfolk, grows on sand near Thetford quite near plants which avoid limestone. Thus about these there is an element of doubt, but I feel fairly sure in my own mind that in Breckland they are chalk-rather than sand-lovers. The same probably applies to other rare species.

The influence of man has produced some interesting changes in Breckland vegetation. Thus the enormous artificial mound known as Castle Hill, Thetford, has a number of calcicoles, including Thalictrum babingtonii. The chalk débris round the entrances to the underground workings started by prehistoric man in search of flint at Grime’s Graves, near Weeting, has a flora very different from the surrounding sand. The various embankments such as that of the Devil’s Ditch nearly all have chalk flowers. Where the Breck has been ploughed plants of the usually chalk-loving Fine-leaved Sandwort, Minuartia hybrida, are common. Round the edges of fields I have found Maiden Pink, Dianthus deltoides, and the large flowers of Field Mouse-ear Chickweed, Cerastium arvense. Both of these are usually chalk plants elsewhere.

NORFOLK AND SUFFOLK

In the counties of Norfolk and Suffolk chalk is by far the most important rock formation, and yet so much of it is covered by other deposits that it is only in relatively few places that it is important to the botanist. There are only the tiniest patches of anything approaching downland and these are mostly by chalk-pits or along roadsides. Perhaps the largest stretches are Ringstead Downs and Massingham Heath. On the latter there were formerly chalk grassland plants growing between anthills on which the calcifuge Ling was to be seen. But Massingham Heath was ploughed up during the second world war. A little over a mile to the west there is an excellent chalk flora, including Spanish Catchfly, Maiden Pink and a rare grass, Phleum phleoides, but the best ground extends only for a hundred yards or so. To the south there are good calcicoles near Castle Acre, and Swaffham is the centre of other scattered chalk exposures.

LINCOLNSHIRE AND YORKSHIRE

Much the same must be said of Lincolnshire. Chalk is the formation of the Wolds, but in many places it is covered with Glacial Drift. Elsewhere it is mostly under cultivation. There may be small areas of downland turf left, but as I have never botanized in this part of the county I cannot say. In any case, most of the recorded stations of calcicoles are on the limestone farther west, and the chalk of Lincolnshire is of little importance to the botanist.

In east Yorkshire there is the most northerly exposure of chalk in England, occupying an area which has been estimated at as much as 400,000 acres. It extends from the Humber north to the Vale of Pickering and includes the magnificent cliffs of Bempton and Flamborough Head. Although much broken up by cultivation and superficial deposits, there is an interesting ground, especially towards the north.

Many of the common plants are the same as those of the southern chalk—Common Rock-rose, Hairy Violet, Fairy Flax, Common Birds-foot Trefoil, Dropwort, Salad Burnet, Clustered Bellflower, Marjoram, Hoary Plantain, and so on. Some of the scarcer species are those with an eastern distribution, found also farther south, like Perennial Flax, Linum anglicum, and Purple Milk-vetch, Astragalus danicus. But the southern botanist will notice that many of the plants with which he is familiar on the South and North Downs are absent, while others, such as Bee Orchid, Ophrys apifera, are much rarer, or even rare and here doubtfully native, like Traveller’s Joy. The Beech is quite common, but here, as in all the glaciated parts of England, it is suspected of having originated from planted trees. Deadly Nightshade, Atropa belladonna, is very frequent and exceptionally fine. In general, Yorkshire chalk lacks many of the attractive southern plants and has very few additional northerners by way of compensation.

This chapter concludes the review of the English chalk. While there is a list of common plants to be found in all districts, yet each area considered has special characteristics. People interested in flowers will always find plenty to see in any of the places discussed, and the fortunate chance that so much of the best English chalk is near to favourite holiday resorts will make it familiar to most readers. Some of the limestone areas to be reviewed in the following chapters are much more difficult of access.