LIMESTONES OF WALES AND THE WELSH BORDER

![]()

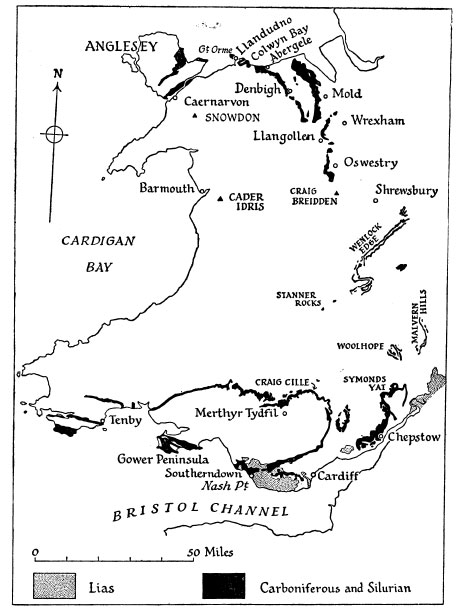

SOME OF the limestone areas of Wales and the Borderland are as well known to the tourist as to the botanist. Others are difficult of access and seldom visited except by people in search of uncommon flowers. No less than six of the geological systems provide habitats for calcicoles of greater or less importance:

Jurassic.—Limestone outcrops in the Lower Lias of the Glamorgan coast.

Rhaetic.—Calcareous beds of White Lias of the Glamorgan coast.

Carboniferous.—Provides important fine scenery and habitats for limestone flowers in (a) the Wye Valley, (b) South Wales, including Gower and Tenby, and (c) North Wales, including the Great and Little Orme and hills near Llangollen.

Silurian.—Hills and outcrops of Woolhope, Wenlock and Aymestry Limestones in the border counties and elsewhere.

Ordovician.—Provides small scattered exposures of limestone and also the basic volcanic soils of Snowdon, Cader Idris and the Breidden Hills.

Pre-Cambrian.—Scattered very small outcrops of no special botanical interest.

Of these the third is of by far the greatest importance and forms the main subject of this chapter.

The Carboniferous Limestone is much older than the Chalk and Oolites, and by contrast to these younger rocks it is massive and hard. It weathers relatively slowly and, following solution along the cracks, often forms vertical cliffs. Thus craggy precipices and gorges with more or less inaccessible sides often provide beautiful scenery and at the same time sanctuary for rare and attractive plants. The value of this protection has already been remarked on in connection with Cheddar and the Avon Gorge. In addition to saving flowers from destruction by holidaymakers, the steepness of much of the Carboniferous Limestone has protected it from the plough. On this rock the botanist makes for natural landscape features, in contrast to the old quarries and roadside verges of the Jurassic regions described in the last chapter. The habitats described in this chapter are arranged in a clock-wise sequence round Wales.

THE WYE VALLEY

There are two places in the lower part of its course where the “sylvan Wye” breaks through the Carboniferous Limestone to form some of the most beautiful scenery in Britain. That beauty is in great measure due to the lovely colourings of the woods which clothe the precipices and slopes. The more interesting plants are mostly those of limestone woodland. Patches of natural turf or even exposed rocks are relatively scarce.

The lower limestone area extends for about three miles north of Chepstow and includes the rocks below the Castle, Piercefield Cliffs, and the Wyndcliff on the western bank of the river, and Tutshill and Lancaut rocks to the west. These places between them have produced a most interesting list of wild flowers. Formerly the richest flora was to be found at the Wyndcliff, but in recent years this has been turned into a tea-garden with well-kept paths and a charge for admittance. Some of the choice plants still linger and doubtless others are to be found in the adjacent woods, but the place is too crowded to encourage a thorough search. The Mossy Saxifrage, Saxifraga hypnoides, under such conditions, might well be a garden outcast, and no botanist has seen the small white flowers of the Toothed Wintergreen, Orthilia secunda, for many years. I have, however, seen the Mountain and Fingered Sedges, Carex montana and C. digitata, and the Mountain Melic, Melica nutans, but these are humbler plants which the tourist ignores.

Across the Wye, the Martagon Lily, Lilium martagon, grows in hundreds in coppiced woodland. Dr. W. A. Shoolbred, who practised in Chepstow for many years and had an unrivalled knowledge of the flowers of the district, regarding it as native and I am inclined to agree with him. The lovely hanging purple flowers of this Lily are to be found in several spots, and certainly at the one where I know it there seems no likely reason why it should have been planted. On the other hand, one must take into account the ease with which the plant has become naturalised in woods and copses in other parts of England.

In the Wye Valley a Spurge, Euphorbia stricta, has its main British localities. It is a dainty, much branched plant of rather a yellowish-green and quite the prettiest of all our Spurges. The only place where I can depend on finding it is by a stream off the limestone, but when conditions are right—probably after coppicing—it is said to come up in quantity in the calcareous woods. Its erratic appearance may be compared to that of the Caper Spurge, E. lathyrus, which has been found in two woods in this district and also higher up the river.

The second place where the Wye cuts through the Carboniferous Limestone is at Symond’s Yat, some 15 miles north of Chepstow. Here the river comes right up to the base of the great wooded hills and then swings north again in a five-mile loop to pass the base of the Yat only a quarter of a mile from the spot where it first approached. On the east side, in Gloucestershire, there is the Yat itself with extensions to Huntsham Hill and the Coldwell Rocks. On the west, in Herefordshire, the Great and little Doward, with Lord’s Wood between them, drop down to the water. The trees, which add so much to the scenery, are very much the same as those in the woods near Chepstow.

Here the Beech forms almost pure woods over small areas, and the dark-leaved Yew contrasts with the silvery leaves of the Whitebeams, Sorbus spp., as on the chalk. Holly, Dogwood, Field Maple and Privet are other common trees and shrubs adding their quota of harmonious colouring. But in addition there are rarer species. The two native Limes, the Large-leaved and Small-leaved, Tilia platyphyllos and T. cordata, grow out of the cliffs on both sides of the Wye. In a quarry below the steepest end of the Great Doward I have seen several trees of a Wild Pear closely related to the scarce Pyrus cordata. There are also several rare Sorbi, including Sorbus vagensis, which A. J. Wilmott described as new to science from Symond’s Yat. The upper woods on the hills have a deeper layer of soil over the limestone, and the trees and flowers are not always those characteristic of calcareous soils.

At Symond’s Yat and the Dowards the wild flowers are mostly woodland species. The Green and the Stinking Hellebores, Helleborus viridis and H. foetidus, both occur on the Great Doward. Their flowers resemble those of the garden Christmas Rose and appear almost equally early in the year. In these woods there are also three rare sedges. The Fingered Sedge, Carex digitata, and the Mountain Sedge, C. montana, are fairly plentiful by the sides of paths, but the Dwarf Sedge, C. humilis, is extremely rare. It grows in a very small patch of limestone turf high up on one of the hills, and when I saw it in 1935 it covered an area of only about two yards square. The story of how it was first discovered here is an interesting one. A botanist named Abraham T. Willmott, who lived at Ross-on-Wye, visited Bristol in 1851 and saw plenty of the Dwarf Sedge in the Avon Gorge. He was particularly impressed by the similarity of the Carboniferous Limestone and, as he called it, “the correspondence of the surface of the rocks” of the Dowards to those at Clifton. Therefore on his return home he made a special search for the sedge and was rewarded by the discovery of the tiny patch which is still the only one known in the Wye Valley. Other Bristol plants which also grow here include Bloody Cranesbill, Geranium sanguineum, Rock Pepperwort, Hornungia petraea (this I failed to find), Wall Pennywort, Umbilicus rupestris, and Narrow-leaved Bitter-cress, Cardamine impatiens. It is a little remarkable that Spring Cinquefoil, Potentilla tabernaemontani, which is so abundant on carboniferous rocks in several other districts, is not to be found on the Dowards, but in Herefordshire is restricted to Silurian limestones.

The Wye Valley can be recommended with confidence not only as a delightful place for a holiday but also as one of the best districts for studying the woodland plants of calcareous areas. It was with good reason that W. H. Purchas claimed that of all the rocks in Herefordshire the Carboniferous limestone is “by far the richest as to the number of plants it produces.”1 It should, however, be made clear that there are other limestones both within the county and just beyond its borders, though they extend over much more restricted areas. Thus parts of the Malvern Hills are calcareous and there are basic rocks at Stanner to the west. In the upper parts of its course there are places where the Wye flows over limestones, but although all these produce rare and interesting flowers they are unimportant in comparison with the areas already described.

SOUTH WALES

Carboniferous Limestone outcrops round the South Wales Coalfield. It extends in a narrow strip running east from Kidwelly in Carmarthenshire to near Abergavenny, where it turns south past Pontypool and behind Cardiff runs westwards to beyond Porthcawl. Interrupted by Swansea Bay, the rock outcrops extensively in the Gower Peninsula and again about Tenby in Pembrokeshire. It thus gives rise to two contrasting kinds of flora—one of the steep inland cliffs above the mining villages characterised by a certain number of upland species, the other of coastal cliffs with maritime plants. Both floras are exceedingly interesting and beautiful, and I think their charm is enhanced by the contrast with the industrial areas through which one has to pass to reach them.

The best place I know on the inland part of the limestone is a magnificent stretch of cliff high up above Crickhowell. Here there is a shrub allied to the Whitebeam and known as Sorbus minima. It grows freely on the precipitous rock and spreads freely from seed, and yet this cliff and another about two miles to the west are the only places in the world where it is known to grow. There was once a threat that the area would continue to be used as a military training ground where live shells would be employed. Energetic protests from botanists, supported by Members of Parliament, prevented this unique little shrub from any risk of being blown out of existence. On the same cliffs I have seen Sorbus porrigentiformis, another scarce tree allied to the Whitebeam, and Miss E. Vachell also showed it to me at a place near Cardiff which is on the same kind of limestone.

The Crickhowell cliffs have Beech growing at over 1000 feet above sea-level in what is probably its most westerly station in Britain as a native plant. They produce both the Large- and Small-leaved Limes, and they have other good things like the little Rock Pepperwort (which I was too late to see myself) and Limestone Polypody, Thelypteris robertiana.

It is surprising how rich this Breconshire limestone is in rare Sorbi. The Rock Whitebeam, Sorbus rupicola, which may be known from the common Whitebeam, S. aria, by its narrower leaves with a tapering base, fans out its branches on the cliffs. And in addition to the other two rare species already mentioned, Sorbus leyana has its only known locality on a single short rock-face in the Merthyr Tydfil district. When I visited it in 1948 I found that a number of the trees were dead. Others had their leaves so eaten by caterpillars that they were almost unrecognisable.

To the south the Carboniferous Limestone outcrops again on and near the coast from Southerndown to beyond Porthcawl. It forms the humps of Ewenny and Ogmore Downs. The Mountain Sedge, Carex montana, grows here near the roadside in a more open place than the Symond’s Yat localities discussed above. Chalk Violet, Viola calcarea, is found near it, but in 1935 I thought it far less uniform and even less convincing as a distinct species than the Box Hill plant. Wall Germander, Teucrium chamaedrys, grows on limestone rocks where it has been known for a century.

The lower beds of the Lias consist of alternating layers of hard impure limestone and shale, whilst the Rhaetic Beds, which extend east from Southerndown, are locally calcareous. They form limestone cliffs along parts of the coast of south Glamorgan, and are quarried for lime and cement at Bridgend. The flora has a good deal in common with that of similar soils in Somerset on the other side of the Bristol Channel. Blue Gromwell, Lithospermum purpurocaeruleum, is frequent, just as it is in parts of the Mendips. Woolly-headed Thistle, Cirsium eriophorum var. britannicum, is abundant, as it is on the Lias near Bristol. Madder scrambles about the cliffs and over bushes, as at the Avon Gorge. Although the traveller from Somerset to Glamorgan has to make a very long journey by land, the direct distance across the Channel is only about 12 miles.

But the Welsh Lias has some plants to offer which are not to be seen on the opposite coast. As Miss Vachell wrote1: “Near Nash Point, at a height of approximately 200 feet, the cliffs are bright in spring with the yellow flowers of the Sea Cabbage (Brassica oleracea) and the magenta blooms of the Hoary Stock (Matthiola incana) which, in such an inaccessible position, might well be considered native.” A mile away there is a most interesting colony of the rare Tuberous Thistle, Cirsium tuberosum. When this was discovered a century ago it set in train a long argument about the correct identification of the Glamorgan plant. The trouble was caused by the ease with which this species hybridises with other thistles both here and in Wiltshire, where it was first found. Because of this it is often very difficult to find pure specimens of the Tuberous Thistle and hence botanists in this country had trouble in getting to know just what the species really was. Now that it has been seen in more places (Distribution Map 8), the arguments of past generations seem almost unnecessary, but I must admit that I saw more of the hybrids than of the pure plant in the South Wales locality!

Another very special rarity of the Lias is the Maidenhair Fern, Adiantum capillus-veneris. I very much doubt if it is still to be found at populous Barry Island, but it grows at a number of places along this coast. At the one where I have seen it a white streak of calcareous matter runs down the cliff. Opinions may differ as to whether the Maidenhair Fern is a calcicole, but from my own experience of it on widely scattered places on the coast I am inclined to think that it is, and that the presence of calcium carbonate in quantity is just as important as freedom from severe frosts in determining where it can grow.

A little to the west is the Gower Peninsula with its fine cliffs of Carboniferous Limestone. At week-ends it becomes the playground of Swansea, from which it is only a short bus or cycle ride, but nevertheless the coast remains unspoiled and a paradise for the naturalist. Except in the places where sand has accumulated—and there is a lot of it at Oxwich Burrows—nearly the whole of the south coast is limestone, which is eventually extended on the western side into the long promontory known as Worm’s Head.

The plant for which Gower is most famous is a small Crucifer, Yellow Whitlow-grass, Draba aizoides var. montana, which grows nowhere else in Britain. It is best known on some old ruins, but I have also seen it on the cliffs, where it occurs for several miles. Like the Maidenhair Fern, it is fortunate that some of the colonies are inaccessible, for otherwise such an attractive plant might soon be exterminated. It has tight little rosettes of leaves rather like those of some of the smaller rockery plants and the heads of yellow flowers appear very early in the year. Just how early they first open I do not know, but at the time of my earliest visit in mid-April they were well past their best and fruits were forming.

The limestone cliffs where the Yellow Whitlow-grass grows rise up from the sea in a series of narrow steps which form a delightful natural rock-garden. In the spring they are blue in places with the flowers of the Vernal Squill, Scilla verna, which is like a miniature Bluebell with erect instead of hanging bells. These contrast with the bright yellow blooms of the Spring Cinquefoil, Potentilla tabernaemontani, and the paler yellow of the Hoary Rock-rose, Helianthemum canum. The last may easily be known from the Common Rock-rose, H. chamaecistus, by the very much smaller flowers and the greyish appearance of the leaves due to white hairs, and absence of stipules. Hoary Rock-rose is a very local plant (Distribution Map 3), but in the places where it occurs it is nearly always abundant. In one place where I saw Draba aizoides it was accompanied by exceptionally large plants of Rock Pepperwort. A little later in the year patches of Bloody Cranesbill, Geranium sanguineum, add their quota of bright colour to parts of these cliffs.

I suppose early spring is the best time of the year to visit the Gower limestone, and yet I have a feeling that too many botanists go in April to the neglect of later months. As some evidence for this there is the Western Spiked Speedwell, Veronica hybrida, which flowers in July and August. It is a handsome and conspicuous plant and there are fairly old records for these cliffs, and yet it was not until 1945 that Glamorganshire botanists could be sure that it grew there. Having regard to its occurrence in the Avon Gorge and in various places in North Wales, it is a flower one would expect to find in Gower. Small Restharrow, Ononis reclinata, now known elsewhere only in South Devon, is another plant recently refound. Specimens were collected from the Gower cliffs in 1828 and it was not seen again for a hundred and twenty-five years.

For many years I expected that someone would find Hair-leaved Goldilocks, Crinitaria linosyris, in Gower. It grows in Somerset and North Wales on the Carboniferous Limestone, and there are plenty of suitable habitats on this coast. My expectation has proved to be well justified. When I visited the Gower cliffs with Miss E. Vachell and Mr. D. McClintock in 1948 for the purpose of checking what I had written for this chapter, we were fortunate enough to discover the Goldilocks. There were only a few plants, but they grew in a wild place far from houses in limestone turf and are undoubtedly native.

The limestone woods of this peninsula are also of interest. I have seen Stinking Hellebore near Park Mill, and Gladdon and Caper Spurge at Nicholaston. The last seems to be much more regular in appearance than in most of its other native habitats, and I think the reason is that it favours the open edge of the woods, where it extends out on to the sand-dunes and is therefore not dependent for light on periodical felling of the trees. Blue Gromwell, Lithospermum purpurocoeruleum, is found in the same wood and in other bushy places in the neighbourhood.

In southern Pembrokeshire there are considerable outcrops of Carboniferous Limestone, particularly on the coast near Tenby. Here it occurs about the town and forms part of Caldey Island, and then extends as a long ridge from Giltar Point until it meets the Old Red Sandstone near Manorbier. Vernal Squill is abundant and there is some quantity of Small Meadow-rue, Thalictrum minus, with many common limestone plants.

The chief object of my visits to these limestone cliffs has been to see the very rare Sea Lavender, Limonium transwallianum, in the place from which H. W. Pugsley described it as new to science in 1924. It looks very like the Rock Sea-Lavender, Limonium binervosum, but has flowers only half the size in short, dense spikes, and leaves less dilated towards their ends. It has since been found in other places in Pembrokeshire and in the Burren district of Ireland. I do not know whether the special Tenby Daffodil, Narcissus obvallaris, is on limestone or not, but Madder, Rubia peregrina, and Ivy Broomrape, Orobanche hederae, are certainly among the flowers which grow here on that rock.

NORTH WALES

Throughout the whole of Central Wales limestone flowers are scarce. From the Tenby district to the Menai Straits acid soils are the rule, and the traveller becomes accustomed to mile after mile of peaty moorland and heath. There are small outcrops of volcanic rocks giving rise to basic soils on a number of the mountains, and especially on Cader Idris and in Snowdonia—such as the well known “hanging garden” of the Glyders—but these are outside the scope of this book. There are also calcareous areas in the coastal dunes, but the only lowland place with a really rich limestone flora recorded is a little hillock on the outskirts of Barmouth. Here there were a number of nice plants, including Western Spiked Speedwell, Veronica hybrida, and Vernal Squill, Scilla verna, forming an interesting link between South and North Wales.

But this is a trivial affair in comparison with the Carboniferous limestone of Anglesey and Caernarvonshire. On the Bangor side of the Menai Straits there was a fairly rich flora until perhaps fifty years ago, when it was spoiled by the extension of the town. In Anglesey the best limestone is three or four miles north of Beaumaris. Here there is a ridge extending from Marian-dyrys, where there is limestone turf by the roadside and round quarries, to Arthur’s Seat a little to the west. Bwrdd Arthur (as the Welsh call it) is a very fascinating place for the botanist. From the road there is a short slope up to a wall of limestone rock about ten feet high. This forms a circle with a flat top, to which a track gives access, enabling the farmer to use it for grazing. In June the ledges on the low cliffs are covered with flowers of brilliant colours in which yellows predominate. Clumps of Hoary Rock-rose are mixed with the less compact but larger flowered Common Rock-rose. Kidney Vetch, Mouse-ear Hawkweed and Lady’s Bedstraw are other abundant yellow flowers here. There are big patches of Bloody Cranesbill, Geranium sanguineum, and bushes of the excessively prickly and dwarf Burnet Rose, Rosa pimpinellifolia. Both in Anglesey and near Llandudno the last two grow on limestone and also on sand-dunes within a few miles. Near Arthur’s Seat there is a small colony of Rock Pepperwort.

The larger area of Carboniferous Limestone marked on the map across the centre of the island is disappointing. I have noticed a few calcicoles here and there by the roadsides, but most of the rock on the lower ground is covered with unsuitable soils.

But the limestone flora of Anglesey is only a curtain-raiser to that of the Carboniferous ridge which begins at the Great Orme and extends with only short gaps through Denbighshire to Denbigh and Ruthin. Llandudno is the usual centre for exploring the riches of this area, and the town nestles under the massive headland of the Great Orme on the one side and the hills running from the Little Orme through Gloddaeth to Deganwy on the other. To many botanists this Creuddyn Peninsula, as it is called, is the limit of their knowledge of the limestone of North Wales, but there is plenty of less well known but almost equally interesting country farther east. From Bryn Euryn, near Colwyn Bay, and Llysfaen to Cefn-yr-Ogof, near Abergele, and then along by Cefn Rocks and Henllan to Denbigh and beyond, there is a chain of fine limestone habitats. In Flintshire a broader range runs southwards from Prestatyn. Many places on these hills have such a profusion of wild flowers that it is a pity they are not better known.

Most readers will already know the Great Orme’s Head (Plate XVI). On three sides there is a toll motor road giving grand views of the coast, and above this steep cliffs rise to the plateau, which attains a height of 679 feet above sea-level; on the fourth side there is the town of Llandudno. The botanist can therefore approach it in two ways. On the first day a walk round the four mile long road with careful examination of the cliffs affords an ample programme. A second day can be devoted to the old quarries and the plateau approached by way of the tramway.

The botanical season on the Orme is a very long one, but to see the full beauty of the flowers here it is necessary to come well before the usual holiday times. My own earliest visit was in the first week in May, and I am not sure that even this was quite early enough to see the spring plants at their best before the shallow soil over the limestone had been baked by the sun. At this time of the year many of the rarities are of course not yet out, but their absence was more than compensated for by an abundance of charming plants of which I had only previously seen the last lingering blossoms. There were sheets of Spring Cinquefoil, Potentilla tabernaemontani, of which the bright yellow flowers contrasted with the blue of Vernal Squill, Scilla verna. On the Little Orme Mr. J. E. S. Dallas told me there are three parallel bands of this last little gem growing where the rocks are steepest. During the short flowering period these show up from a distance as blue bands across the hill. On my early visit a few last flowers of Hairy Violet, Viola hirta, on the Great Orme showed that there had been an earlier display of blue of a different sort, while the rather pale flowers of Hoary Rock-rose were already open. Another early plant in greater abundance than I had previously see it was Rock Pepperwort. Though too small to add conspicuous colour to the display, the daintiness of this little plant is extremely attractive. White was added to the show by the masses of flowers produced by tufts of Spring Sandwort, Minuartia verna.

The Marine Drive on the north side of the Orme divides the limestone cliffs above the road from rocks of a different kind with a contrasting flora below. Maritime plants ascend well up on the limestone. Amongst the earliest to flower is the Sea Cabbage, Brassica oleracea, of which the yellow blooms are also to be seen in abundance in a quarry on the Little Orme. A white-flowered Crucifer which grows by the road is Common Scurvy-grass, Cochlearia officinalis. Although most frequent by the sea, this fleshy-leaved plant seems to thrive on the limestone, for it is also found inland on that rock at Cheddar. The pink flowers of the Thrift, Armeria maritima, and the white Sea Campion, Silene maritima, are very little later, and are followed towards the end of summer by the yellow Umbellifer, Samphire, Crithmum maritimum. Some of these maritime plants get quite a long way from the sea. Mr. Dallas told me that he has seen Yellow Sea-Poppy, Glaucium flavum, inland here in a limestone quarry, just as it occurs away from the shore in Sussex, Kent and the Isle of Wight.

On these cliffs above the road there are also patches of Bloody Cranesbill and a profusion of Hawkweeds, Hieracium spp. These yellow-flowered Composites, with blooms somewhat like those of the Dandelion, are a puzzling lot not only to the tyro but also to the experienced botanist. Several rare ones occur on the Orme and it happens that one of these is quite easily identified. Hieracium cambricum has narrow glaucous leaves with long teeth on each side, and is only found in Wales and chiefly on the limestone about Llandudno.

On the top the cliffs are exposed to the full force of the wind and it is interesting to see its effect on the shrubs. Common Buckthorn, Juniper, Privet, Hawthorn and Wild Cotoneaster, Cotoneaster integerrimus, all grow with prostrate, woody, knotted stems hardly rising above the rocks and with very few leaves. The Cotoneaster is the special plant which many people come to the Orme to see. I have found it in two places well over a mile apart in recent years, but it was once more common. Probably grazing by sheep has prevented its regeneration from seed and they, rather than unscrupulous botanists, are to be blamed for its present rarity. Where protected from the wind, it grows into a bush some five feet tall, but here the plants show signs of dying from old age, if one can judge from the amount of dead, or almost dead, wood they now show.

Our native Cotoneaster integerrimus has small pinkish-white flowers and almost round leaves which are white with short, dense hairs underneath. Until the present century its identification never caused the slightest difficulty, but now a number of allied shrubs have become so thoroughly naturalised that many people mistake the foreigners for the rare plant of our Floras. On the Orme the usual shrub they name in error is Cotoneaster microphyllus, which is abundant in places at the Llandudno end. Here it is probably bird-sown from fruits brought from the public gardens. This Himalayan species grows almost flat on the rocks and has numerous small white flowers which are very attractive to bees. The evergreen leaves are only about a third of an inch long and shining green above, whereas the deciduous leaves of the native plant are three times as long. The Chinese Cotoneaster horizontalis is rather similar to microphyllus, growing flat on the rocks with branches spreading out to form flat sprays, and leaves only a trifle larger, but the flowers are pink and the leaves only very slightly hairy below. The shrub which is really most like integerrimus is C. simonsii, a native of Assam, but this has densely hairy young twigs and the leaves have long scattered hairs on both surfaces. These are all naturalised in various places on the limestone in North Wales. On one hill, Cefn-yr-Ogof, on the Abergele side of Llanddulas, I have seen all three aliens growing close together. But I think the native Cotoneaster has never been found off the Great Orme, and even there not all recent records are reliable.

To see all the rarities of this great limestone headland it is necessary to make quite a number of visits at different times of the year. In June I have seen the great yellow flowers (nearly two inches across) of the Spotted Catsear, Hypochoeris maculata, but it seems to be restricted to one limited part of the Orme. In July and August there are lovely blue spikes of the Western Spiked Speedwell, Veronica hybrida. This is much more widespread and so abundant in places that it attracts the attention of people who are not specially interested in flowers. Late September or even early October is the time to go for Goldilocks, Crinitaria linosyris. I have seen this in two places on the Orme and it is known elsewhere in the district.

With the exception of the Cotoneaster and the Hawkweed, which are special rarities of the Orme, all the plants so far mentioned for the headland have been discussed earlier. In other words, they are species which occur farther south and in many cases have a distribution in Britain along the west coast. Some indication of the northern element in the flora is given by the greater abundance of Mountain Everlasting, Antennaria dioica, which here and in Anglesey is much more constant and plentiful than in southern counties. A more definite sign is the Dark-flowered Helleborine, Epipactis atrorubens, which grows in the chinks of the Carboniferous Limestone. This orchid is met again in the north of England and it is also found on limestone rocks in Scotland and Ireland. Early in the summer it may be recognised by the oval shape of the leaves, and in July the rich red colour of the flowers, with their characteristic rugged bosses, make identification easy. The Dark-flowered Helleborine is nearly always seen growing out of narrow chinks in the limestone (Plate 41) but sometimes, in the Peak District and Yorkshire, for example, it favours screes.

Facing the Great Orme and on the other side of Llandudno, there is another series of hills extending from the Little Orme’s Head to Gloddaeth. Here some of the limestone flowers are better grown and more plentiful than they are on the more popular headland.

Likewise many of the Orme plants are abundant on the hills which run eastward from Colwyn Bay almost to Abergele, where they turn south. The nicest hill on this range is, I think, Cefn-yr-Ogof, where the three Asiatic Cotoneasters (see above) grow in great abundance with interesting native plants.

Some six miles south-east of Abergele there is another good patch of limestone on both sides of the river Elwy, and extending on through Galltfaenan and Henllan to Denbigh. In one place in this area there is a colony of Western Spiked Speedwell and the woods contain a good deal of the Small-leaved Lime, Tilia cordata, and some Herb Paris, Paris quadrifolia. But the specially exciting plant here is Blue Gromwell, Lithospermum purpurocaeruleum.

This was first discovered by John Ray, the greatest of early English naturalists, when he stayed at Denbigh on Saturday and Sunday, 17 and 18 May, 1662. He described it as “an elegant plant” and gave the locality in such clear terms that even now it is easy to find from his published note. And yet I must admit that the Blue Gromwell caused two friends and myself to search very hard on the evening of 12 June, 1947. Perhaps it was because we were tired after a hard day’s botanizing—or maybe we were just stupid—but although we went straight to the right place it was over three hours before we saw our plant. In the meanwhile we had decided to search elsewhere and spent valuable time in the failing light without success. At last we decided to abandon our botanical pride and inquired at a farmhouse whether a plant with brilliant blue flowers which appeared in April and May grew in the neighbouring woods. The farmer’s wife knew it at once and took us straight to the spot. We were pleased to observe that she was proud of the rarity in her keeping and intended to take care that no harm came to it. At this place the Blue Gromwell grows, not on a sunny wood border as I had expected from my previous experience, but well within the wood amongst hazels and in considerable shade. It produces flowers very sparingly, and it is likely that it is less flourishing than it was before the trees and shrubs reached their present height.

From Denbigh Castle Hill the Carboniferous Limestone is discontinuous as it runs south-east by Ruthin. Just west of Wrexham a narrow outcrop runs south for some 20 miles and on the way forms magnificent cliffs near Llangollen. Here on the Trevor Rocks and precipices above Tan-y-graig on the Eglwys Mountain there is an interesting limestone flora, though the choicer plants are in small quantity and difficult to find. Of these the Dark-flowered Helleborine and the Rock Pepperwort have already been discussed in connection with the Great Orme, where they are more plentiful. The Limestone Polypody, Thelypteris robertiana, and Rigid Buckler Fern, Dryopteris villarii, are two ferns found sparingly. The latter is particularly interesting as it is only known elsewhere in Britain in a limited area in north-west England, where it is locally plentiful, and in Snowdonia, where it is extremely rare.

The extension of this outcrop south of Llangollen does not seem to be well known botanically. A careful search might well reveal uncommon plants in new localities.

So much for the Carboniferous Limestone of Wales, but before this chapter closes brief mention must be made of a few areas where calcicoles occur on older formations. The most famous of these is on the Ordovician rocks of Breidden Hill in Montgomeryshire. Here igneous rocks give rise to basic soils on which some of the limestone flowers abound. This steep, well-wooded hump between Welsh-pool and Shrewsbury has long been a mecca for botanists. To them it is still a “mine of wealth” (as the Rev. W. W. How described it in 1859), but it must have been even more attractive before the plantations of firs and larches grew up and before quarrying destroyed some of the best ground. The naturalist who now climbs to the rough column of stones erected to the memory of Lord Rodney on the 1200-feet high top may be disappointed in his finds. Nevertheless most of the rarities are still there.

The gem of Craig Breidden is Rock Cinquefoil, Potentilla rupestris, which was first recorded in 1688. Thanks to the removal of plants to cottage gardens and the attacks of unprincipled collectors, it became so rare that it was regarded as probably extinct until a few plants were found again about 25 years ago. Western Spiked Speedwell, Veronica hybrida, Sticky Catchfly, Lychnis viscaria, Bloody Cranesbill, Geranium sanguineum, and Welsh Stonecrop, Sedum forsteranum, are other rarities which have been found on these precipitous crags.

The Silurian system includes the Woolhope, Wenlock and Aymestry Limestones. Those of the Wenlock series are exposed along the fine Edge of that name which runs from Much Wenlock to Craven Arms and has a fairly good limestone flora. But the Silurian limestones as a whole have relatively little botanical importance. Although more extensive than those of the Ordovician and Pre-Cambrian systems, they are equally dwarfed by the Carboniferous as providing calcareous habitats in Wales and the border counties.