CRAVEN IN YORKSHIRE

![]()

NORTH OF the Derbyshire Dales there is a gap of some 50 miles before the next big exposure of Carboniferous Limestone in the Craven district of West Yorkshire. On the intervening stretches of the Pennines, Coal Measures and Millstone Grit give rise to acid soils with large areas of some of the most dreary vegetation in the whole of Britain. To this the varied flora of the limestone is a welcome contrast.

Craven is near the southern end of a large area marked as Carboniferous Limestone on small-scale geological maps. Stretching from coast to coast at the Solway Firth, and some 135 miles from south to north, this area includes much of Yorkshire and Northumberland and parts of Lancashire, Westmorland, Durham and Cumberland, and it extends into Scotland. In the south there are extensive exposures of massive limestone, the best of which are considered in this chapter. Going north along the Pennines, the limestone becomes increasingly replaced by beds of shale and sandstone. In Northumberland the latter predominate and beds of limestone are only exposed on a relatively small scale.

It is not easy to generalise about the flora of the limestone of the north of England, but I think its characteristic feature is its “upland” nature. Carboniferous Limestone descends to sea-level at Humphrey Head. It ascends so high on Ingleborough (2,373 ft.), Penyghent (2,273 ft.) and Mickle Fell (2,591 ft.) that it becomes the habitat of mountain flowers outside the scope of this book. Excluding these two extremes, most of the country favoured by botanists is upland rather than mountainous and the flowers are mostly northern species. The Derbyshire Dales served as an introduction to this type of flora—in Yorkshire the northern plants are more numerous.

In this region magnificent cliffs are the homes of rare plants. The Yorkshire and Westmorland Scars, such as Gordale, Malham Cove, Dib Scar, Scout Scar, Whitbarrow Scar, and the sea-washed cliffs of Humphrey Head, are famous for the richness of their flora. Where the limestone comes down to low levels, as in the Silverdale district of Lancashire, it is often well wooded, but on higher ground only scattered trees and open scrub are to be seen except in sheltered places.

On the west side of the Pennines the Carboniferous Limestone shares the heavy rainfall for which the Lake District is famous, and here the interesting feature known as “limestone pavement” is locally extremely well developed. This is due to the same cause as leaching. Rain-water containing carbon dioxide in solution is capable of dissolving calcium carbonate to the extent of about 1 in 16,000 parts, and its action continued over many centuries has an important effect on limestone rock. Joints in the rock yield first; the jointing of the Carboniferous Limestone here, being rectangular, leads to a characteristic product of weathering. Yielding along the horizontal bedding-planes, it gives rise to a bare, jointed, flattish surface known as “clints.” The vertical joints are widened into crevices (Plate 36) called “grikes,” which commonly extend down to a depth of 5 to 15 feet. These are the home of many interesting and rare plants which find shelter both from the desiccating action of the wind and from attacks of grazing animals, which are unable to reach them. The “Pot-holes,” which are particularly well developed on Ingleborough, are also due to the solubility of the limestone and offer shelter to a luxuriant vegetation.

Maritime cliffs, upland crags, pavement and pot-holes, old mine workings, gorges through which run rivers and streams, and flat hilltops are amongst the places where the botanist has to search in this vast and often wild stretch of country. Some of the localities have been the subject of pilgrimage throughout the history of British botany; others are inadequately explored even now.

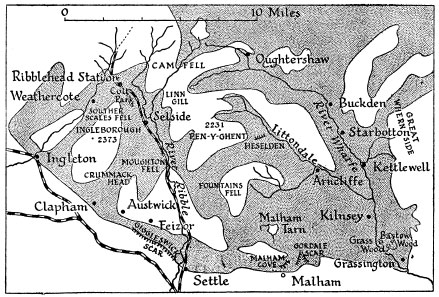

Only the Craven district of west Yorkshire will be considered in the present chapter. This is a tract of wild hilly country extending east from Ingleborough. Here the rivers Wharfe and Aire, which drain to the North Sea, and the Ribble, which runs south-west to the Irish Sea, have their sources. All the important roads follow their valleys, which provide a convenient way of arranging the limestone habitats of Craven.

WHARFEDALE

The Wharfe runs through an interesting bit of wooded limestone at Bolton Abbey; but it is at Grassington, some nine miles farther up the valley, that the really exciting limestone country commences. Here there are good plants found on calcareous rocks by the river at Ghaistrills, and Grass and Bastow Woods and Dib Scar are famous for their flowers. Near Kilnsey Crag the valley forks. One branch leads through Kettlewell, Starbotton and Buckden; the other by Arncliffe and Littondale to Heseltine (Hesleden) Gill and the slopes of Penyghent. There are few more exciting places for the botanist in Britain.

The sides of these two valleys are fairly steep and there is much bare limestone, but in many places there are also narrow strips of open scrub woodland—so open that much of it we should hardly regard as worthy of the name of wood in the south of England. Below the scrub on the open ground the limestone is often damp—at least locally—and here the most characteristic plant is the Bird’s-eye Primrose, Primula farinosa. This little gem has numerous small lilac-purple flowers arranged on a common stalk like a Cowslip, and the lower surface of the leaves is mealy. Its distribution in Britain is limited to approximately the area considered in this and the next chapter, though it strays across the border into the south of Scotland. Near Kilnsey it grows with a plant which is usually found only on the coast—the Sea Plantain, Plantago maritima.

In several places the Bird’s-eye Primrose is associated with one of the special rarities of this valley—the Bitter Milkwort, Polygala amara. They both thrive over wet limestone where there is no undue competition with coarser plants. Bitter Milkwort, like the Kentish Milkwort, P. austriaca, has very small flowers and a rosette at the base of the stem. Apart from the adjoining upper Aire valley, its only other British station is in Teesdale (Distribution Map 4). The flowers are usually of a pale slaty-blue and not easy to find, and it was probably for this reason that it remained undetected in Wharfedale until the comparatively recent date of 1883.

Another very special rarity for which the valley is famous is the Lady’s Slipper Orchid. The old botanists knew this farther west round Ingleborough, but there it has not been seen for many years. The days when ten Lady’s Slippers could be bought at Settle market from a man who had brought about forty to sell, as Thomas Frankland informed Curtis in 1781,1 are long over. We may deplore the destruction of the flowers which resulted from such transactions, but they indicate that the plant must have been tolerably plentiful. Formerly this orchid ranged over a fairly wide area: it extended into Westmorland on the Carboniferous, and grew on the Oolite in eastern Yorkshire and on the Magnesian Limestone in Durham (Distribution Map 15). To-day it is one of the rarest and most elusive of British plants and one of the few I have not seen wild myself. The nearest I have come to getting practical knowledge of the Lady’s Slipper is to be shown places where it has been found in previous years.

There is little doubt that, apart from its rarity, the chief reason why this orchid is so seldom seen is its shyness of flowering. Growing among Lily-of-the-Valley, or on limestone scree under scattered trees, its yellow sabot-shaped flowers are conspicuous enough not to be easily missed. Many of those which do occur are found by children from the villages. In the past they have often been transplanted into cottage and inn gardens. The fact remains that some plants rarely produce flowers, although there is a case on record where twenty blooms were cut from one clump in the space of seven years. Many botanists go to look for it too late in the year, being misled by the dates given in the text-books; the last week in May or early June would seem to be the best times.

It is not entirely easy to account for the decrease of the Lady’s Slipper. The depredations of botanists and villagers are obviously to some extent responsible, but these may not be the only causes. From the records over three centuries it would seem that it has always been rare, but that there have been periodical “assurgences” when for a few years it has been found in increased quantity. It is likely that the occasional notes of a number of flowers being found in one or several places have coincided with these periods. There have been no “assurgences” during the present century and it is possible that one is almost due. But against this theory there is the undoubted fact that there have been important general changes in the vegetation of some of its old haunts. Thus Helks Wood, Ingleton, where botanists used to find it in the seventeenth century, is now a rather unlikely place for it to grow.

Calceolus Mariae, or Mary’s Shoe, as it was once called, has shallow roots and an underground stem which creeps in leaf mould just below the surface of the soil. it can thus live for a number of years without flowering, while putting up pairs of leaves in shape and colour very similar to those of the Lily-of-the-Valley. The blooms have an elaborate mechanism for ensuring cross-pollination but, as Lees remarks that he never saw them visited by insects and that he doubted if they commonly ripened seed, it seems probable that in this country the mechanism is a failure. Nevertheless I very much hope that any reader finding a flower will follow the example of Yorkshire naturalists and leave it lightly covered with brushwood so that it stands a chance of fulfilling its mission.

There are three places on the high limestone west of Littondale where Mountain Avens, Dryas octopetala, is to be found. This is a most attractive little plant commonly obtainable from nurserymen. In cultivation many people find it a shy flowerer and have to rest content with the leaves, which are shaped rather like those of the oak (though very much smaller) and are downy white on their lower surface. In the wind-swept places where it grows wild there are usually plenty of blooms, and these with their commonly eight snowy white petals are a glorious sight in early summer. The fruits which follow are feathery and not unlike those of the Pasque Flower, Pulsatilla vulgaris, though this belongs to the Ranunculaceae and Mountain Avens to the Rosaceae.

These are some of the special rarities of Upper Wharfedale and Littondale, but a better idea of the interesting vegetation can be obtained from a brief description of a rough limestone valley near Grassington which I visited in July, 1946, for the second time. The valley ended in an amphitheatre of cliffs some 150 feet high, and these continued along its south side for about a quarter of a mile. A track ran along the bottom where there was a lot of Ash and Hazel and some Downy Birch, Betula pubescens, Mountain Ash, Sorbus aucuparia, and Aspen, Populus tremula. On the cliffs were a number of plants of Rock Whitebeam, Sorbus rupicola, and a great deal of Ivy.

Below the cliffs a scree ran down to the track, and on this we found common southern calcicoles, such as Fairy Flax, Small Scabious and Common Rock-rose, growing with Mountain Bedstraw, Galium pumilum, and northern plants like Grass-of-Parnassus, Parnassia palustris, Bird’s-eye Primrose and Bitter Milkwort. Towards the top of the scree there was one place which even from a distance appeared blue—almost like that blue haze one associates with Bluebell woods. As we climbed up it became evident that this was caused by a glorious patch of Jacob’s Ladder, Polemonium caeruleum, which has already been described in connection with the Derbyshire Dales.

The sheer limestone cliffs had a wonderful flora in their cracks and narrow ledges. There were ferns like Hart’s-tongue, Phyllitis scolopendrium, Common Polypody, Polypodium vulgare, and Brittle Bladder Fern, Cystopteris fragilis, and the much rarer Limestone Polypody, Thelypteris robertiana, and Green Spleenwort, Asplenium viride. Then there were interesting flowers similar to those of the Derbyshire limestone such as Germander Whitlow-grass, Draba muralis, Hoary Whitlow-grass, D. incana, with its twisted pods, Bloody Cranesbill, Geranium sanguineum, Field Garlic, Allium oleraceum, and Mossy Saxifrage, Saxifraga hypnoides. With these were Hairy Rock-cress, Arabis hirsuta, Crosswort, Cruciata chersonensis, Horseshoe Vetch, Dropwort, Marjoram and Salad Burnet. The presence of these common plants of the southern chalk on this northern limestone cliff at an altitude of some 750 feet above sea-level serves to stress the “common factor” which exists between all the calcareous soils in Britain.

Grass Wood is a well-known place both for plants and picnics. Angular Solomon’s-seal, Polygonatum odoratum, and Dark-flowered Helleborine, Epipactis atrorubens, are in the district. Much of the lower part of the woodland is planted and its character has been artificially changed. On the other hand, Bastow Wood, which adjoins it at a higher level (900–950 ft.), is more natural. The dominant trees are Ash and Downy Birch, widely spaced and dwarfed owing to the shallowness of the soil and exposure to winds. Many of them seem to be dying, and the dead stumps and branches scattered about give an eerie appearance which is enhanced by the dense webs of caterpillars which cover the Bird Cherries, Prunus padus.

GORDALE SCAR AND MALHAM COVE

Six miles west of Grassington, across the watershed into the region drained by the head-waters of the Aire, there is another limestone district which every botanist should visit. The longest tributary of the river is Gordale Beck, which drains down from Malham Moor through a mile-long rocky gorge and then runs over a waterfall at Gordale Scar. This is one of the finest sights in Britain. The visitor is awed by the towering cliffs around him and the knowledge that to reach the ledges and the valley above he must climb up the difficult track by the waterfall.

The flowers of Gordale Scar are very much the same as those described for the valley at Grassington, but Small Meadow-rue, Thalictrum minus, is very much more abundant.

People who know Gordale Scar will readily appreciate how inaccessible are some of the ledges on the cliffs, and that a botanist, scrambling about, may, by chance, find his way on to one of them by a route not easily retraced. This is the simple explanation of how a locality for a rare little sedge was lost for sixty years although the locality was recorded so precisely that one would have supposed its rediscovery presented no difficulty. In June, 1878, William West found Carex capillaris growing on the terraced limestone rocks of Gordale “on the left-hand as the ascent is made, above the large mass of debris.” It was previously unknown south of Teesdale and so the find was an important one. In the years which followed many botanists searched carefully for the little sedge without success, but it was ever in the minds of local naturalists. When I visited Gordale in 1935 with Mr. C. A. Cheetham, the Secretary of the Yorkshire Naturalists’ Union, he expressed the view that it would one day be refound. His optimism was justified and in 1939 Mr. G. A. Shaw found Carex capillaris in a place which agreed with West’s description. Since then several botanists have seen it.

From Gordale it is a short walk to Malham Cove, a magnificent amphitheatre of grand and precipitous cliffs (Plate 34). On each side of the scar big screes lead down to the stream which issues from the bottom of the cliff. At the bottom and on the screes there is open woodland made up chiefly of Ash, Hazel and Hawthorn.

The glory of Malham Cove is a magnificent display of Jacob’s Ladder, which is all the more interesting on account of the fact that John Ray found it here over 270 years ago. The words in which he recorded it1 are worth quoting:

“Greek Valerian, called by the vulgar Ladder to heaven or Jacob’s Ladder. Found … about Malham Cove, a place so remarkable that it is esteemed one of the wonders of Craven. It grows there in a wood on the left hand of the water as you go to the Cove from Malham plentifully; and also at Cordill or the Whern [Gordale Scar], a remarkable Cove where comes out a great stream of water, near the said Malham.”

It is not to be found now at the exact spot indicated by Ray, and it seems to have disappeared completely from Gordale, where it was plentiful as late as 1805. As the eye follows the blue flowers up the scree at Malham Cove on a day when the sky is cloudless, one is tempted to follow the example of the “vulgar” and call it “Ladder to heaven.”

The precipice at the Cove holds a botanical mystery which has not been blessed with a satisfactory solution like the one at Gordale Scar. In 1862 L. C. Miall published a record on his own authority of Hoary Rock-rose, Helianthemum canum, as growing at “Malham, near the Cove.” Later, F. Arnold Lees claimed to have confirmed the record (there is a specimen in his collection) and said that the plant grew “on the step-like ledges of rock near the top of the face of the Cove, with a S.W. aspect.” He hastened to add that reaching it was risky for all but the cool-headed! Like Carex capillaris, this has acted as a challenge to a generation of Yorkshire botanists to break their necks, but the plant still eludes them.

The cliffs here are also adorned with Rock Whitebeam, and there is a good deal of Germander Whitlow-grass, Hoary Whitlow-grass, Bloody Cranesbill, Mountain Bedstraw and various Hawk-weeds. Just above the top is a small but famous bit of limestone pavement, but the plants that grow in it are so heavily grazed whenever they appear above the level of the clints that their description will be reserved for better examples.

Leaving the bottom of the Cove, visitors are very likely to find Spring Sandwort, Minuartia verna, and more locally they may see Alpine Penny-cress, Thlaspi alpestre. These occur in a good many places in Craven and particularly, as between Malham and Settle and at Grassington, about the workings from old lead-mines. At Malham the Penny-cress, like Jacob’s Ladder, suffers severely from the nibbling of grazing animals.

RIBBLESDALE

On the other side of the road west of Malham Cove and almost opposite to it (though half a mile farther up the steep hill from where the public track comes out), there is a gate labelled “To Settle via Stockdale Farm.” This is the route to follow across the watershed into Ribblesdale. It is the way the old botanists used to reach Malham from Settle. The market town is just as good a centre to-day for exploring the limestone country as it was three centuries ago.

The period of greatest activity in the exploitation of the mineral mines of Craven seems to have started soon after A.D. 1600 and continued throughout that century. It is therefore almost certain that the workings at Pikedaw, Grizedales, Stockdale and Attermire Scar were either still being dug or had only recently been abandoned when John Ray came along the track. The “lead-plants,” Spring Sandwort and Alpine Penny-cress, were probably very much more plentiful than they are to-day.

A mile and a half north-west of Settle the wooded Giggleswick Scar borders the main road to Kirkby Lonsdale. From Settle to Clapham this road is almost the precise boundary between the Carboniferous limestone to the north and Millstone Grit to the south, and it therefore provides a useful opportunity of comparing their respective floras. Giggleswick Scar figures prominently in the old botanical records, many of which were given as “above the Ebbing and Flowing Well.” This may still be seen by the side of the main road, and provided it is not choked up with fallen leaves and you have the time to spare to wait while it empties and fills, it will intrigue you. Several rare plants are still to be seen on the screes and cliffs of the Scar, but I fancy that the growth of the trees (Beeches have been planted on the lower part) and the digging of the quarry at the east end have made great changes.

From Settle there is a big area running south-west almost to Preston marked on the map as Carboniferous Limestone, but little calcareous rock is exposed on the surface. It is north of Settle up the Ribble valley beyond Horton that the best country is to be found. The road runs between the mighty hills of Ingleborough on the west and Penyghent on the east, rising all the time until it is over 1000 feet above sea-level, near Ribblehead station. The railway, the “Midland” route to Carlisle, runs near the road all the way, and Horton and Ribblesdale stations are convenient for exploring the dale. It is interesting to see from the train how the cuttings through rocks which are not limestone are immediately picked out by the presence of Foxglove, Digitalis purpurea, and Broom, Sarothamnus scoparius.

There is one plant which has been found in a number of places in Ribblesdale and on tracks leading up on to Ingleborough which is not known anywhere else in the British Isles. Yorkshire Sandwort, Arenaria gothica, was first found in 1889 at Ribblehead station, and there was considerable argument about its identity before it was named. A little tufted plant with small leaves and white flowers resembling those of the commoner Spring Sandwort, it is very closely allied to Arenaria ciliata, which only grows with us on the Ben Bulben range, Co. Sligo, and A. norvegica, which is restricted in Britain to north-west Scotland, the Hebrides, Shetland and Ireland. (Distribution Map 5). These three are regarded by some botanists as subspecies of one collective species, and it is remarkable that they are restricted to such very limited and widely scattered localities. Abroad the Yorkshire Sandwort has its main home in Sweden, but in spite of the fact that it was first noticed by a road near a railway station it is generally regarded as a native plant in Ribblesdale.

Between Selside and Ribblehead there is one of the most remarkable and uncanny woods in Britain. Colt Park is the best example in Britain of an aboriginal scar limestone ashwood, and the variety and interest of its flora is astonishing, having regard to the small area concerned. I was there last on 16 July, 1946, and my notes ran to four closely written pages, but as the general flora has been described fully in a fairly recent book,1 only a brief account will be given here.

Colt Park Wood consists mainly of Ash, with some Bird Cherry (covered with caterpillar webs as at Grassington), Mountain Ash, various Sallows, Guelder Rose, Viburnum opulus, Soft-leaved Rose, Rosa villosa, Hawthorn and Elder. These grow on a limestone pavement with some of the widest and deepest cracks (grikes) that I have ever seen. In places it is difficult to jump across from one slab to the next, and the intervening crack may go down for some eight feet—in others the grikes are much less wide and shallower. Every footstep has to be carefully chosen if bruised shins and possibly even broken bones are to be avoided. On account of the danger to their limbs, grazing animals are kept out. Down in the cracks there is plenty of moisture and plants are sheltered from the wind. Here vegetable remains accumulate and plants which favour woodland humus thrive. Bracken is sometimes eight feet tall with its fronds expanding above the surface of the rock. Dog’s Mercury, Mercurialis perennis, can be found a yard in height. The general ground vegetation is much as one would expect in an Ashwood but modified by the extraordinary conditions under which it grows.

Lily-of-the-Valley is abundant and so is Ramsons, Allium ursinum, which is easily distinguished by the pungent smell of onions which arises every time you tread on the lily-like leaves. Angular Solomon’s-seal is there and so is Baneberry, Actaea spicata (see Plate 38). This is a curious plant belonging to the Ranunculaceae, with divided leaves having their leaflets arranged in threes each side of the midrib, spikes of small white flowers, and purplish-black berries. Herb Christopher, the old botanists called it; but even Gerard and Johnson were unable to find a use for it. “I finde little or nothing extant in the antient or later writers, of any one good propertie wherewith any part of this plant is possessed: therefore I wish those that love new medicines to take heed that this be none of them, because it is thought to be of a venomous and deadly qualitie.”1 Perhaps this warning has played its part in preserving this rare species from destruction! The area over which it is found in Britain is restricted to a narrow band across northern England (Distribution Map 7). In Craven there are a fair number of localities and it extends westwards on the Carboniferous Limestone to near the shore of Morecambe Bay at Arnside. As already stated, it is also found east of Craven on the Magnesian Limestone and on Oolite near Scarborough. In addition there is one very puzzling locality in Yorkshire for Baneberry. Although elsewhere restricted to calcareous soils, it grows in a wood near Mirfield on the Coal Measures—but here it has been suggested that it has been introduced.

One of the glories of Colt Park Wood is sheets of a lovely large-flowered Pansy, Viola lepida, with very pretty variegated blooms. In one place there is Alpine Cinquefoil, Potentilla crantzii. Yellow Star-of-Bethlehem, Gagea lutea, grows here in its highest British locality. I have only seen leaves and believe it seldom flowers. Herb Paris is also to be found in the wood.

In the damper spots there is plenty of Melancholy Thistle, Meadow Sweet, Filipendula ulmaria, Water Avens, Wood Cranesbill, Geranium sylvaticum, and Giant Bellflower, Campanula latifolia. I also noticed Marsh and Soft Hawksbeards, Crepis paludosa and C. mollis, which are plants with a northern distribution. The former is fairly common in hilly or mountainous districts, but Soft Hawksbeard is a rare plant which I have only seen a few times. They are both rather like Hawk-weeds and not too easy to tell apart before the fruits are ripe. This, however, did not present the slightest difficulty when I was last at Colt Park, for on 16 July the Marsh Hawksbeard was in full bloom while the later-flowering Crepis mollis was only just opening.

A mile and a half away, and on the other side of the road, there is a most beautiful gorge known as Ling Gill. The sides are clothed with a luxuriant vegetation thriving under the constantly moist atmosphere and protected from the wind and from grazing animals by the steepness of the slopes. There is only one way to see Ling Ghyll and that is by walking in the bed of the stream, and this presents considerable difficulty after heavy rain when it may be impossible to negotiate the waterfall half-way through.

The flowers here include Marsh Hawksbeard, Melancholy Thistle, Wood Cranesbill, Herb Paris, Giant Bellflower, Globe Flower and Mountain Everlasting, Antennaria dioica. There is also a record of London Pride, Saxifraga umbrosa, which I have seen under very similar conditions in Hesleden Gill on the other side of Penyghent. This is a little different from the larger-flowered London Pride commonly grown now in town gardens, but it seems to be the same as a form which was once cultivated in this country, now rejected by gardeners in favour of a more showy plant. It is possible that some scrap of it got into these remote Yorkshire Gills from cottage gardens, but this is not supported by the situations of the few human habitations in the district and it seems just as likely that it is a true native.

The district from Ling Ghyll and Cam Fell to Oughtershaw, to the east at the head of Wharfedale, may hold the key to another mystery of British field botany. The Eyebrights are quite a difficult critical group, but one of the most distinct of them is the Narrow-leaved Eyebright, Euphrasia salisburgensis, which occurs in some plenty on the limestones of the west of Ireland. As Praeger remarks, it “is easily recognised in the field by its dwarf bushy growth, characteristic colour, and jagged upper leaves.” He adds that the latter assume a beautiful coppery brown colour when the plant grows in exposed places. In Britain it has only been found in Yorkshire (the Devon record is an error) and the finder was F. Arnold Lees.

As I write I have before me Lees’ own annotated copy of Dr. G. C. Druce’s British Plant List, edition 1, which was given to him by the author and eventually found its way into my library. Against E. salisburgensis, Lees has written: “Cam, Outershaw and on exposed table limestone to Conistone Cold!” but he never published the record. In his herbarium at the British Museum (Natural History) there are specimens from Outershaw and Buckden (farther down the Wharfe Valley) collected in 1885 and 1886 which H. W. Pugsley said exactly match the Irish plants. It will be seen that these place-names extend over a large area of country and it is perhaps not to be expected that the plant will be found again easily. The rediscovery of Narrow-leaved Eyebright in Yorkshire would be a find of first-class botanical importance.

INGLEBOROUGH

The fissured massive limestone of the Craven area reaches its finest development on the slopes of Ingleborough; a mighty hill which is most conveniently explored from Austwick, Clapham or Ingleton. The alpine plants which grow near the summit, like those of Penyghent, belong to a book on mountain flowers rather than to this volume, but there is plenty of interest on the scars and limestone pavements on the flanks of the hill. These are beautifully illustrated by the photographers in Plate 36 to 42.

One of the finest areas of limestone pavement is on Souther Scales Fell. This is less wooded than at Colt Park, a couple of miles to the north-east, but the main features are very similar. The fissures afford protection to the plants from grazing animals, and, if allowed, trees such as the Ash, Sycamore and Downy Birch grow up to form open woodland (Plate 37). In places there are sheets of Lily-of-the-Valley (Plate 36), while on account of the heavy rainfall and accumulation of humus in the cracks there is local development of plants which will grow under acid conditions, like Melancholy Thistle (Plate 40), Bracken and Devil’s-bit Scabious, Succisa pratensis. Baneberry (Plate 38) is found in the district, and so are many other plants already mentioned. Just below, at Weathercote Cave, Chapel-le-dale, the Kidney-leaved Saxifrage, Saxifraga hirsuta, has been naturalised for over a century. It is rather like London Pride but has much rounder leaves with blunt teeth.

The south-west side of the hill is equally interesting, and especially about Crummack Head, Sulber and Moughton Scars. This is the area where a rare fern, the Rigid Buckler Fern, Dryopteris villarii, has its headquarters in Britain. It is particularly a plant of the tabular Carboniferous Limestone, growing in the cracks of the pavement or on the screes. To the east it is found in small quantity above Settle and at Malham, and to the west it is scattered through the south of Westmorland to Whitbarrow and Arnside Knott and into Lancashire at Warton Crag. There is a slight extension of its range north into the Eden drainage area and it has been found very rarely in North Wales. Apart from this it is a very local plant (Distribution Map 16). Rigid Buckler Fern has fronds of a curious bluish-green colour and usually grows stiffly erect (Plate 42). The Holly Fern, Polystichum lonchitis, has also been found near here and elsewhere in Craven, but it is intensely rare and it is to be hoped that anyone finding it will leave it undisturbed.

On Moughton Fell the Ecological Committee of the Yorkshire Naturalists’ Union have been making a most interesting study of Juniper, Juniperus communis. It was noticed that this shrub was showing signs of decadence—that many of the old plants were sickly and that seedlings to take their place were rare. Several explanations have been offered, such as the attacks of rabbits and fungi, but in spite of the careful work of Mr. A. Malins Smith and his colleagues the reasons for the decrease of the Juniper here and in other places are not yet known.

The inconspicuous little Field Lady’s Mantle or Parsley Piert, Aphanes arvensis, is common throughout the British Isles and grows on various soils. It is, for example, frequent on mole-heaps on the chalk downs. So-called “Common” Lady’s Mantle, Alchemilla vulgaris, a much larger plant with rather inconspicuous green flowers, is rare in the south of England though plentiful enough in hilly districts in the north. It has now been divided into a number of segregates most of which are fairly easy to distinguish by the careful use of the keys in standard floras. The characters by which they are separated are derived mainly from the distribution of the hairs, and whether they are spreading or not, and the shape of the leaves and their toothing. A. glaucescens (A. hybrida auctt.) with spreading silky hairs, and A. minima, with rather few hairs, are small plants especially associated with the Ingleborough district.

The seeds of Lady’s Mantles are known to remain capable of germinating after they have passed through the intestines of sheep, cows, horses and other grazing animals. In Derbyshire and Yorkshire I have noticed that the distribution of these plants often seems to be associated with the droppings of such beasts.

Grasses are not particularly the subject of this book, but it is hardly possible to leave Craven without mention of the Blue Moor Grass, Sesleria caerulea. Most visitors see it in the summer when the flower-heads are dry and look like chaff, and the leaves are coarse and yellow. In this state it is far from handsome. But as I first saw it one May, when snow still rested on the hills, with the spikes fresh and suffused with a bluish tint, the Blue Moor Grass looked very different. It is abundant on the limestone of the whole of this area and over many stretches by far the most common grass.

Mention of the Mezereon, Daphne mezereum, has been intentionally left until last. This is partly because the little winter-blooming shrub is so persecuted by people who dig it up for their gardens that I dare give no clue to its precise localities. The other reason is that it is out of flower when most visitors go to Craven and therefore unlikely to attract their attention. Mezereon grows about two to three feet tall, and in February and March bears red flowers towards the end of its stem. The leaves are leathery and resemble those of its ally, the Spurge Laurel, Daphne laureola, but unlike those of that evergreen species they are shed in autumn. I have seen the two growing together in one scrub-wood in Craven and it is believed that they may hybridise. The Mezereon has been found in a number of wild and remote woods in the district, and to my mind it is more certainly wild here than in most of the other parts of England where it occurs. There is always the question whether birds have carried the seeds from gardens or if man transplanted the roots into cultivation at nearby cottages, but in Craven it seems likely that transport has been mainly in the latter direction.

Craven, with its fissured massive tabular limestone, is one of the most important calcareous areas in Britain. It has a characteristic flora with a number of rare species and a long botanical history. Grassington, Gordale Scar, Malham Cove and Ingleborough are places which every nature-lover should visit, and if it is necessary to omit any of them from an itinerary no time should be lost in making good the omission.