XI. The Battles of the Chemin Des Dames and of the Ardres

May 27 to June 2

The rest cure of the Aisne—Attack upon the Fiftieth Division—Upon the Twenty-first— Fifth Battery R.F.A.—Glorious Devons—Adventure of General Rees—Retreat across the Aisne—Over the Vesle—Arrival of Nineteenth Division—Desperate fighting—Success of 4th Shropshires—General Pelle’s tribute—General prospect of the Allies midway through 1918

It had been determined to rest four of the crippled British divisions which had been heavily engaged first on the Somme and then in the battle of the Lys. These divisions were the Twenty-fifth (Bainbridge), Twenty-first (Campbell), Eighth (Heneker), and Fiftieth (Jackson), all forming the Ninth Corps (Hamilton-Gordon). Each of them had been cut to pieces twice in the course of little more than a month, and should by every pre-war precept have been incapable of exertion for a long time to come. They were reconstituted with numbers of recruits under fresh officers, both leaders and men with slight experience of actual warfare. They were then sent, via the outskirts of Paris, the direct route being under fire from the German guns in front of Amiens, and they were thrust into the French line just north of the Aisne in the region of the Chemin des Dames. The intention was to give them repose, but the change was looked upon with misgiving by the divisional generals, one of whom wrote to the present chronicler at the time saying, “They think it will be a rest cure, but to my mind it is more likely to be a fresh centre of storm.

As a matter of fact the Germans, who had now made two colossal thrusts, the one on March 21 on the Somme, the other at the Lys on April 9, were planning a third desperate attack at this very point. The competent military historian of the future with all the records before him will no doubt be able to pronounce how far it was wise for the German high command to leave two unfinished tasks in order to undertake a third one. On the face of it, it seemed an unlikely thing to do, and that perhaps is why they did it. The line at this position had few natural advantages and was not strongly held. In the opinion of British generals it would have been wise if it could have been drawn south of the Aisne, since a broad river is a good friend in one’s front, but a treacherous enemy in one’s rear. There were reasons, however, why it was not easy for the French to abandon the north bank, for they had spent much time, labour, and human life in capturing Craonne, the California Plateau, and other positions within that area, and it was a dreadful thing to give them up unless they were beaten out of them. They held on, therefore—and the British divisions, now acting as part of the French army, were compelled to hold on as well. The Fiftieth Northern Territorial Division had a frontage of 7000 yards from near Craonne to Ville-aux-Bois, including the famous California Plateau; on their immediate right was the Regular Eighth Division, and to the right of that in the Berry-au-Bac sector, where the lines cross the Aisne, was the Twenty-first Division, this British contingent forming the Ninth Corps, and having French troops upon either side of them. The Twenty-fifth Division was in reserve at Fismes to the south of the river. The total attack from Crecy-au-Mont to Berry was about thirty miles, a quarter of which—the eastern quarter—was held by the British.

Confining our attention to the experience of the British troops, which is the theme of these volumes, we shall take the northern unit and follow its fortunes on the first day with some detail, remarking in advance that the difficulties and the results were much the same in. the case of each of the three front divisions, so that a fuller account of one may justify a more condensed one of the others. The position along the whole line consisted of rolling grass plains where the white gashes in the chalk showed out the systems of defence. The Germans, on the other hand, were shrouded to some extent in woodland, which aided them in the concentration of their troops. The defences of the British were of course inherited, not made, but possessed some elements of strength, especially in the profusion of the barbed wire. On the other hand, there were more trenches than could possibly be occupied, which is a serious danger when the enemy comes to close grips. The main position ran about 5000 yards north of the Aisne, and was divided into an outpost line, a main line of battle, and a weak system of supports. The artillery was not strong, consisting of the divisional guns with some backing of French 75’s and heavies.

The Fiftieth Division, like the others, had all three brigades in the line. To the north the 150th Brigade (Rees) defended Craonne and the slab-sided California Plateau. On their right, stretching across a flat treeless plain, lay the 151st Brigade (Martin). To the right of them again was the 149th Brigade (Riddell), which joined on near Ville-aux-Bois to the 24th Brigade (Grogan) of the Eighth Division. It may give some idea of the severity with which the storm broke upon the Fiftieth Division, when it is stated that of the three brigadiers mentioned one was killed, one was desperately wounded, and a third was taken before ten o’clock on the first morning of the attack.

The German onslaught, though very cleverly carried out, was not a complete surprise, for the experienced soldiers in the British lines, having already had two experiences of the new methods, saw many danger signals in the week before the battle. There was abnormal aircraft activity, abnormal efforts also to blind our own air service, occasional registering of guns upon wire, and suspicious movements on the roads. Finally with the capture of prisoners in a raid the suspicions became certainties, especially when on the evening of May 26 the Germans were seen pouring down to their front lines. No help arrived, however, for none seems to have been immediately available. The thin line faced its doom with a courage which was already tinged with despair. Each British brigade brought its reserve battalion to the north bank of the Aisne, and each front division had the call upon one brigade of the Twenty-fifth Division. Otherwise no help was in sight.

The bombardment began early in the morning of May 27, and was said by the British veterans to be the heaviest of the war. Such an opinion meant something, coming from such men. The whole area from Soissons to Rheims was soaked with gas and shattered with high explosives, so that masks had to be worn ten kilometres behind the lines. A German officer declared that 6000 guns were employed. Life was absolutely impossible in large areas. The wire was blown to shreds, and the trenches levelled. The men stuck it, however, with great fortitude, and the counter-barrage was sufficiently good to hold up the early attempts at an infantry advance. The experiences of the 149th Infantry Brigade may be taken as typical. The front battalion was the 4th Northumberland Fusiliers under Colonel Gibson. Twice the enemy was driven back in his attempt to cross the shattered wire. At 4 A.M. he won his way into the line of outposts, and by 4:30 was heavily pressing the battle line. His tactics were good, his courage high, and his numbers great. The 6th Northumberland Fusiliers, under Colonel Temperley, held the main line, and with the remains of the 4th made a heroic resistance. At this hour the Germans had reached the main lines both of the 151st Brigade on the left and of the 24th on the right. About five o’clock the German tanks were reported to have got through on the front of the Eighth Division and to be working round the rear of the 149th Brigade. Once again we were destined to suffer from the terror which we had ourselves evolved. The main line was now in great confusion and breaking fast. The 5th Northumberland Fusiliers were pushed up as the last reserve. There was deep shadow everywhere save on the California Plateau, where General Rees, with his three Yorkshire battalions, had repulsed repeated assaults. The French line had gone upon his left, however, and the tanks, with German infantry behind them, had swarmed round to his rear, so that in the end he and his men were all either casualties or captives.

Colonel Gibson meanwhile had held on most tenaciously with a nucleus of his Fusiliers at a post called Centre Marceau. The telephone was still intact, and he notified at 5:45 that he was surrounded. He beat off a succession of attacks with heavy loss to the stormers, while Temperley was also putting up a hopeless but desperate fight. Every man available was pushed up to their help, and they were ordered to hold on. A senior officer reporting from Brigade Headquarters says: “I could hear Gibson’s brave, firm voice say in reply to my injunctions to fight it out, ‘Very good, sir. Good-bye!’” Shortly afterwards this gallant man was shot through the head while cheering his men to a final effort.

The experience of the Durhams of the 151st had been exactly the same as that of the Northumberlands of the 149th. Now the enemy were almost up to the last line. The two brigadiers, Generals Martin and Riddell, together with Major Tweedy of the reserve battalion, rushed out to organise a local defence, drawing in a few scattered platoons for the purpose. As they did so they could see the grey figures of the Germans all round them. It was now past six o’clock, and a clear, sunny morning. As these officers ran forward, a shell burst over them, and General Martin fell dead, while Riddell received a terrible wound in the face. In spite of this, he most heroically continued to rally the men and form a centre of resistance so as to cover Pontavert as long as possible. The 5th Northumberland Fusiliers with a splendid counter-attack had regained the position of Centre d’Evreux, and for the moment the pressure was relieved. It was clear, however, both to General Jackson and to General Heneker that both flanks were exposed, and that their general position was an acute salient far ahead of the Allied line. The Twenty-first Division was less affected, since it already lay astride of the river, but the French line on the left was back before mid-day as far as Fismes, so that it was absolutely necessary if a man were to be saved to get the remains of the two British divisions across the Aisne at once. Pontavert, with its bridges over river and canal, was in the hands of the Germans about 7 A.M., but the bridge-heads at Concevreux and other places were firmly held, and as the men got across, sometimes as small organised units, sometimes as a drove of stragglers, they were rallied and lined up on the south bank. The field-guns had all been lost but the heavies and machine-guns were still available to hold the new line. Some of the 5th Northumberland Fusiliers were entirely cut off, but fought their way through the Germans, and eventually under Major Leatheart reported themselves at the bridges. So rapid had been the hostile advance that the dressing-stations were captured, and many of our doctors and wounded fell into the hands of the Germans to endure the hard fate which these savages so often reserved for the brave but helpless men who fell into their power. It is a terrible fact which should not be forgotten, that among these torturers the nurses and the doctors held in many cases a prominent position. The 150th Brigade, under General Rees, which was defending the Craonne position, had endured an even heavier ordeal than the others. It was. on the extreme left of the British line, on the right of the French 118th Regiment. This latter seems to have been entirely destroyed or taken early in the attack.

The British brigade lay in front of Craonne upon the edge of the California Plateau, with the 5th Yorks on the right and the 4th East Yorks on the left. The 4th Yorks were in brigade reserve in Craonelle, immediately behind the fighting line. The Germans got through the French on the left, also through a gap down the Corbeny railroad on the right of the 150th and left of the 151st Brigade. Colonel Thomson of the 5th Yorks, a very brave and experienced soldier who was said by those who knew him best to be worth half a battalion in his own person upon the day of battle, was in charge on the right, and hung on with tooth and claw to every inch of ground, but his little force, already greatly weakened by the cannonade, was unable to resist the terrible onslaught of the German infantry. Two counter-attacks were attempted by reserve companies, but each was swept away. The Germans were on the flank in Craonne and enfiladed the line with a machine-gun. Colonel Thomson’s last words over the telephone to Headquarters were, “Good-bye, General, I’m afraid I shall not see you again.” He was killed shortly afterwards. Major Haslett of the East Yorks made an equally desperate resistance on the other flank, and finally he and a wounded sergeant-major were captured with their empty pistols in their hands. Meanwhile the Brigade Headquarters at La Hutte were practically surrounded and under a terrible fire. General Kees endeavoured to get into touch with his only remaining battalion, the 4th Yorks, but they had already been overrun by the enemy. Colonel Kent, with sixteen men, had thrown himself into a house in Craonelle, and had fought until the whole party were killed or wounded. The enemy was now several miles to the rear of the few survivors of the 150th Brigade, who endeavoured to make their way back as best they might. It gives some idea of how completely they were cut off that General Rees, after many adventures and escapes, was finally stopped and taken by encountering the main line of the German traffic coming down the road which he had to cross. This was late in the day of May 27, when the enemy was well across the Aisne. It may be of interest to add that General Rees was taken before the Kaiser next morning, whom he found upon the California Plateau. The emperor behaved with courtesy to his prisoner, though he could not refrain from delivering a monologue of the usual type upon the causes of the war and the iniquity of Great Britain in fulfilling her treaty obligations. Some account must now be given of the experiences of Heneker’s Eighth Division which occupied the centre of the British line. This division, like the others, had been sent to the Aisne for a rest cure after its terrific exertions upon the Somme. Full of raw soldiers and inexperienced officers it would have seemed to be entirely unfit for battle, but it had the two solid assets of experienced leading in the senior officers and great regimental traditions, that ever present stand-by of the British Army. Young as were the troops they took General Heneker’s orders literally when he issued the command that the posts were to be held at all costs, and, as a consequence. hardly a single battalion existed as a fighting unit after the engagement.

The British field-batteries were mostly to the north the river, and were greatly damaged by the preliminary German fire. They were accurately located by the enemy, and were smothered in poison and steel. So were the Gernicourt defences, which formed an important tactical position with a permanent garrison on the right of the division. All three brigades were in the line, the 25th on the right, the 24th in the centre, and the 23rd on the left. The outpost line was utterly overwhelmed in the first rush, the experience being much the same as on March 21, for each small body of men found itself isolated, and could only do its best to hold its own patch of ground. Thus at 5:15 A.M. a pigeon message was sent, “H.Q. 2nd Berks, consisting of Colonel Griffin, Captain Clare, and staff, are surrounded. Germans threw bombs down dug-out and passed on. Appeared to approach from right rear in considerable strength. No idea what has happened elsewhere. Holding on in hopes of relief.” Their position was typical of many similar groups along the front, marooned in the fog, and soon buried in the heart of the advancing German army. The right of the 25th Brigade had been thrust back, but on the left the 2nd Berkshires made a desperate resistance. The whole front was intersected by a maze of abandoned trenches, and it was along these that the enemy, shrouded in the mist, first gained their fatal footing upon the flank. The 2nd East Lancashires were brought up in support, and a determined resistance was made by the whole brigade within the main zone of battle. The German tanks were up, however, and they proved as formidable in their hands as they have often done in our own. Their construction was cumbrous and their pace slow, but they were heavily armed and very dangerous when once in action. Eight of them, however, were destroyed by the French anti-tank artillery. At 6:30 the 25th Brigade, in shattered remnants, was back on the river at Gernicourt.

The attack on this front was developing from the right, so that it came upon the 24th Brigade an hour later than upon its eastern neighbour. The 2nd Northamptons were in front, and they were driven in, but rallied on the battle zone and made a very fine fight, until the German turning movement from the south-east, which crossed the Miette south of the battle zone, took the line in flank and rear. In the end hardly a man of the two battalions engaged got away, and Haig, the brigadier, with his staff, had to cut their way out at the muzzle of their revolvers, shooting many Germans who tried to intercept them. The 23rd Brigade was attacked at about the same time, and the 2nd West Yorkshires managed to hold even the outpost line for a time. Then falling back on the battle position this battalion, with the 2nd Devons and 2nd Middlesex near the Bois des Buttes, beat off every attack for a long time. The fatal turning movement threatened to cut them off entirely, but about 7:30 General Grogan, who had set his men a grand example of valour, threw out a defensive flank. He fell back eventually across the Aisne south of Pontavert, while the enemy, following closely upon his heels, occupied that place.

Many outstanding deeds of valour are recorded in all the British divisions during this truly terrible experience, but two have been immortalised by their inclusion in the orders of the day of General Berthelot, the French general in command. The first concerned the magnificent conduct of the 5th Battery R.F.A., which, under its commander, Captain Massey, stuck to its work while piece after piece was knocked out by an overwhelming shower of German shells. When all the guns were gone Captain Massey, with Lieutenants Large and Bution and a handful of survivors, fought literally to the death with Lewis guns and rifles. One man with a rifle, who fought his way back, and three unarmed gunners who were ordered to retire, were all who escaped to tell the heroic tale. The other record was that of the 2nd Devons, who went on fighting when all resistance round them was over, and were only anxious, under their gallant Colonel Anderson-Morshead, to sell their lives at the price of covering the retreat of their comrades. Their final stand was on a small hill which covered the river crossing, and while they remained and died themselves they entreated their retiring comrades to hurry through their ranks. Machine-guns ringed them round and shot them to pieces, but they fought while a cartridge was left, and then went down stabbing to the last. They were well avenged, however, by one post of the Devons which was south of the river and included many Lewis guns under Major Cope. These men killed great numbers of Germans crossing the stream, and eventually made good their own retreat. The main body of the battalion was destroyed, however, and the episode was heroic. In the words of the French document: “The whole battalion, Colonel, 38 officers, and 552 in the ranks, offered their lives in ungrudging sacrifice to the sacred cause of the Allies.” A word as to the valour of the enemy would also seem to be called for. They came on with great fire and ardour. “The Germans seemed mad,” says one spectator, “they came rushing over the ground with leaps and bounds. The slaughter was frightful. We could not help shooting them down.”

Whilst this smashing attack had been delivered upon the Fiftieth and Eighth Divisions, Campbell’s Twenty-first Division on the extreme right of the British line had also endured a hard day of battle. They covered a position from Loivre to Berry-au-Bac, and had all three brigades in action, six battalions in the line, and three in reserve. Their experience was much the same as that of the other divisions, save that they were on the edge of the storm and escaped its full fury. The greatest pressure in the morning was upon the 62nd Brigade on the left, which was in close liaison with the 25th Brigade of the Eighth Division. By eight o’clock the posts at Moscou and the Massif de la Marine had been overrun by the overpowering advance of the enemy. About nine o’clock the 7th Brigade from the Twenty-fifth Division came up to the St. Auboeuf Wood within the divisional area and supported the weakening line, which had lost some of the outer posts and was holding on staunchly to others. The Germans were driving down upon the west and getting behind the position of the Twenty-first Division, for by one o’clock they had pushed the 1st Sherwood Foresters of the Eighth Division, still fighting most manfully, out of the Gernicourt Wood, so that the remains of this division with the 75th Brigade were on a line west of Bouffignereux. This involved the whole left of the Twenty-first Division, which had to swing back the 62nd Brigade from a point south of Cormicy, keeping in touch with the 7th Brigade which formed the connecting link. At 3:20 Cormicy had been almost surrounded and the garrison driven out, while the 64th Brigade on the extreme right was closely pressed at Cauroy. At six in the evening the 7th Brigade had been driven in at Bouffignereux, and the German infantry, beneath a line of balloons and aeroplanes, was swarming up the valley between Guyencourt and Chalons le Vergeur, which latter village they reached about eight, thus placing themselves on the left rear of the Twenty-first Division. Night fell upon as anxious a situation as ever a harassed general and weary troops were called upon to face. The Twenty-first had lost few prisoners and only six guns during the long day of battle, but its left had been continually turned, its position was strategically impossible, and its losses in casualties were- very heavy. It was idle to deny that the army of General von Boehm had made a very brilliant attack and gained a complete victory with, in the end, such solid trophies as 45,000 Allied prisoners and at least 400 guns. It was the third great blow of the kind within nine weeks, and Foch showed himself to be a man of iron in being able to face it, and not disclose those hidden resources which could not yet be used to the full advantage.

The capture of Pontavert might have been a shattering blow to the retreating force, but it would seem that the Germans who had pushed through so rapidly were strong enough to hold it but not, in the first instance, strong enough to extend their operations. By the afternoon of May 27 they were over at Maizy also, and the force at Concevreux, which consisted of the remains of the Fiftieth and part of the Eighth and Twenty-fifty Divisions, was in danger of capture. At 2 P.M. the Germans had Muscourt. The mixed and disorganised British force then fell back to near Ventclay, where they fought back once more at the German advance, the Fiftieth Division being in the centre, with the 75th and 7th Brigades on its right. This latter brigade had been under the orders of the Twenty-first Division and had helped to hold the extreme right of the position, but was now involved in the general retreat. Already, however, news came from the west that the Germans had not got merely to the Aisne but to the Vesle, and the left flank and rear of the Ninth Corps was hopelessly compromised. Under continuous pressure, turning ever to hold up their pursuers, the remains of the three divisions, with hardly any artillery support, fell back to the south. On the western wing of the battle Soissons had fallen, and Rheims was in a most perilous position, though by some miracle she succeeded in preserving her shattered streets and desecrated cathedral from the presence of the invaders.

The Eighth Division had withdrawn during the night to Montigny, and, in consequence, the Twenty-first Division took the general line, Hermonville — Montigny Ridge, the 64th Brigade on the right, with the 62nd and 7th in succession on the left. Every position was outflanked, however, touch was lost with the Eighth on the left, and the attack increased continually in its fury. Pronilly fell, and the orders arrived that the next line would be the River Vesle, Jonchery marking the left of the Eighth Division. On the right the Twenty-first continued to be in close touch with the French Forty-fifth Division. All units were by this time very intermingled, tired, and disorganised. The 15th Durhams, who had fought a desperate rearguard action all morning upon the ridge north of Hervelon Château, had almost ceased to exist. The one gleam of light was the rumoured approach of the One hundred and thirty-fourth French Division from the south. It had been hoped to hold the line of the River Vesle, but by the evening of May 28 it was known that the Germans had forced a passage at Jonchery, where the bridge would have been destroyed but for the wounding of the sapper officer and the explosion of the wagon containing the charges. On the other hand, the Forty-fifth French Division on the right was fighting splendidly, and completely repulsed a heavy German attack. When night fell the British were still for the most part along the line of the Vesle, but it was clear that it was already turned upon the west. Some idea of the truly frightful losses incurred by the troops in these operations may be formed from the fact that the Eighth Division alone had lost 7000 men out of a total force of about 9000 infantry. About eight in the morning of May 29 the enemy renewed his attack, pushing in here and there along the line in search of a gap. One attempt was made upon the Twenty-first Division, from Branscourt to Sapicourt, which was met and defeated by the 1st Lincolns and 6th Leicesters. Great activity and movement could be seen among the German troops north of the river, but the country is wooded and hilly, so that observation is difficult. Towards evening, the right flank of the fighting line was greatly comforted by the arrival of the French Division already mentioned, and the hearts of the British were warmed by the news that one of their own divisions had come within the zone of battle, as will now be described.

When the Ninth Corps was sent to the Aisne, another very weary British division, the Nineteenth and of the (Jeffreys), had also been told off for the French front with the same object of rest, and the same actual result of desperate service. So strenuous had the work of this division been upon the Somme and in Flanders, that the ranks were almost entirely composed of new drafts from England and Wales. Their destination was the Chalons front, where they remained for exactly twelve days before the urgent summons arrived from the breaking line on the Aisne, and they were hurried westwards to endeavour to retrieve or at least to minimise the disaster. They arrived on the morning of May 29, and found things in a most critical condition. The Germans had pushed far south of the Aisne, despite the continued resistance of the survivors of the Eighth, Twenty-fifth, and Fiftieth British Divisions, and of several French divisions, these debris of units being mixed up and confused, with a good deal of mutual recrimination, as is natural enough when men in overwrought conditions meet with misfortunes, the origin of which they cannot understand. When troops are actually mixed in this fashion, the difference in language becomes a very serious matter. Already the Allied line had been pushed far south of Fismes, and the position of the units engaged was very obscure to the Higher Command, but the British line, such as it was, was north of Savigny on the evening of May 28. Soissons had fallen, Rheims was in danger, and it was doubtful whether even the line of the Marne could be held. Amid much chaos it must, indeed, have been with a sense of relief that the Allied generals found a disciplined and complete division come into the front, however young the material of which it was composed.

A gap had opened in the line between the Thirteenth French Division at Lhery and the One hundred and fifty-fourth near Faverolles, and into this the 57th and 58th Brigades were thrust. The artillery had not yet come up, and the rest of the Allied artillery was already either lost or destroyed, so there was little support from the guns. It was a tough ordeal for boys fresh from the English and Welsh training camps. On the left were the 10th Worcesters and 8th Gloucesters. On the right the 9th Welsh Fusiliers and 9th Welsh. It was hoped to occupy Savigny and Brouillet, but both villages were found to be swarming with the enemy. Remains of the Eighth and Twenty-fifth Divisions were still, after three days of battle, with their faces to the foe on the right of the Nineteenth Division. They were very weary, however, and the 2nd Wiltshires were brought up to thicken the line and cover the divisional flank north of Bouleuse. This was the situation at 2 P.M. of May 29.

The tide of battle was still rolling to the south, and first Savigny and then Faverolles were announced as being in German hands. A mixed force of odd units had been formed and placed under General Craigie-Hackett, but this now came back through the ranks of the Nineteenth Division. On the right also the hard-pressed and exhausted troops in front, both French and British, passed through the 2nd Wiltshires, and endeavoured to reform behind them. The Nineteenth Division from flank to flank became the fighting front, and the Germans were seen pouring down in extended order from the high ground north of Lhery and of Treslon. On the right the remains of the of the Eighth Division had rallied, and it was now reinforced by the 2nd Wilts, the 4th Shropshire Light Infantry, and the 8th Staffords, the latter battalions from the 56th Brigade. With this welcome addition General Heneker, who had fought such a long uphill fight, was able in the evening of May 29 to form a stable line on the Bouleuse Ridge. By this time the guns of the Nineteenth Division, the 87th and 88th Brigades Royal Field Artillery, had roared into action—a welcome sound to the hard-pressed infantry in front. There was a solid British line now from Lhery on the left to the eastern end of the Bouleuse Ridge, save that one battalion of Senegal Tirailleurs was sandwiched in near Faverolles. Liaison had been established with the Thirteenth and One hundred and fifty-fourth French Divisions to left and right.

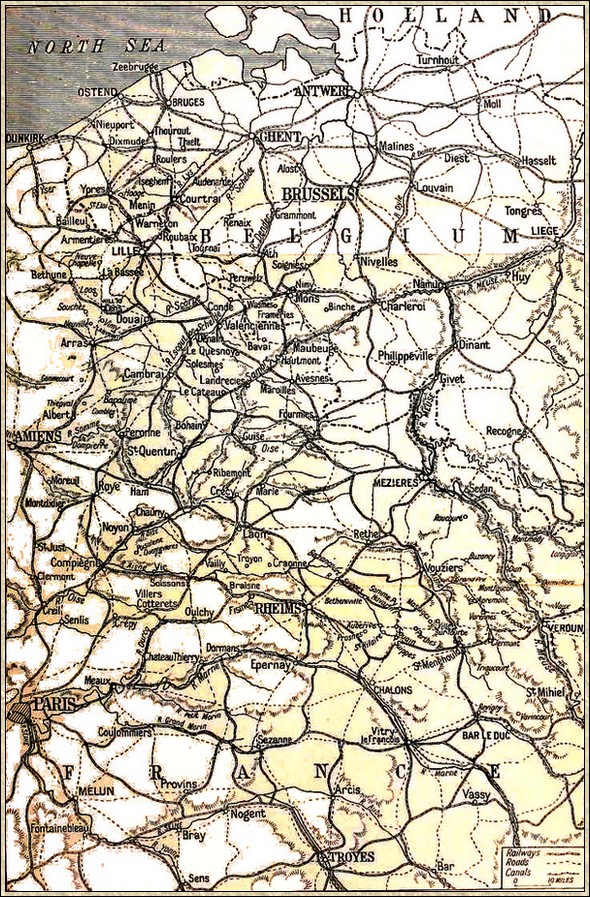

The general positions of the British Divisions during the battles of the Chemin des Dames and the Ardre, May 27-June 3.

The early morning of May 30 witnessed a very violent attack along all this portion of the line. By 6 A.M. the enemy had worked round the left flank of. the 10th Worcesters at Lhery, driving before them some of the troops, French and British, who were exhausted from the long battle. It is difficult for either writer or reader to imagine the condition of men who have fought a losing battle for three days without cessation. If Foch saved up his reserves during these weeks of agony, it was surely at a precious cost to the men who bore the weight. The left company of the 10th Worcesters lost all its officers and 60 per cent of its men, and Lhery had to be left to the enemy. Meanwhile, the Senegalese, who, like all tropical troops, are more formidable in attack than in defence, were driven in near Faverolles, the Germans making a frontal attack in eight lines. They pushed through the gap, outflanked the 9th Welsh Fusiliers on the left and the 2nd Wiltshires on the right, cutting off a platoon of the former battalion. Both these battalions suffered very heavily, the Welsh Fusiliers especially being cut to pieces. At both ends of the line the remains of the front battalions had to fall back upon their supports. The 74th Composite Brigade, already referred to as being under General Craigie-Hackett, fought on the left of the Nineteenth Division, and was ordered to hold the Lhery-Rohigny road. The pressure, however, upon these tired troops and upon the remains of the 10th Worcesters continued to be very great, and by 11 A.M. the situation was critical on the left of the line, the flank having been driven in, and the 8th Gloucesters enfiladed so that the D’Aulnay Wood could no longer be held. These changes enabled the Germans to close in upon the 9th Welsh and the remains of the 9th Welsh Fusiliers, attacking them in front and flank. The troops on their right gave way, and the assailants were then able to get round the other flank of these two devoted battalions, and practically to surround them, so that very few won their way back. The whole front line had gone with the exception of the 10th Warwicks on the left. For a time it seemed as if there was nothing to limit this powerful thrust of the enemy, but in the usual miraculous fashion a composite party of odds and ends, drawn from stragglers and details, hastily swept together by General Jeffreys, were hurried up to the high ground south of Ville-en-Tardenois. With the aid of four machine-guns from the Nineteenth Division this force held the victorious enemy from coming further, covered the left flank of the 10th Warwicks, and formed a bastion from which a new wall could be built. A second bastion had been made by the 5th South Wales Borderers, pioneers of the Nineteenth Division, who had dug in south of Rohigny and absolutely refused to shift. Up to 2 P.M. the 2nd Wilts also held their ground north of Bouleuse. Between these fixed points the 57th and 58th Brigades were able to reorganise, the 15th Warwicks and 9th Cheshires covering the respective fronts. On the right the Twenty-eighth French Division had relieved the One hundred and fifty-fourth, while the 4th Shropshires and 8th North Staffords, both still intact, formed a link between the two Allies. Touch had been lost on the left, and patrols were sent out to endeavour to bridge the gap. At this period General Jeffreys of the Nineteenth Division commanded the whole British line. A serious loss had been caused by the wounding of General Glasgow, the experienced leader of the 58th Brigade. General Heath of the 56th Brigade took over the command of both units.

The Germans had reached their limit for the day, though some attempt at an attack was made in the afternoon from the wood of Aulnay, which was beaten back by the British fire. It was rumoured, however, that on the left, outside the British area, he was making progress south of Rohigny, which made General Jeffreys uneasy for his left wing. Up to now the British had been under the general command of the Ninth British Corps, but this was now withdrawn from the line, and the Nineteenth Division passed to the Fifth French Corps under General Pelle, an officer who left a most pleasant impression upon the minds of all who had to deal with him. On May 31 the front consisted of the French Fortieth on the left, the French Twenty-eighth on the right, and the British Nineteenth between them, the latter covering 12,000 yards. The weary men of the original divisions were drawn out into reserve after as severe an ordeal as any have endured during the whole war. The 74th Composite Brigade was also relieved. Some idea of the losses on the day before may be gathered from the fact that the two Welsh battalions were now formed into a single composite company, which was added to the 9th Cheshires.

The morning of the 31st was occupied in a severe duel of artillery, in which serious losses were sustained from the German fire, but upon the other hand a threatened attack to the south-west of Ville-en-Tardenois was dispersed by the British guns. About two o’clock the enemy closed once more upon the left, striking hard at the 6th Cheshires, who had been left behind in this quarter when the rest of the 74th Composite Brigade had been relieved. The 10th Warwicks were also attacked, and the whole wing was pushed back, the enemy entering the village of Ville-en-Tardenois. The Warwicks formed up again on high ground south-east of the village, the line being continued by the remains of the 10th Worcesters and 8th Gloucesters. Whilst the left wing was driven in, the right was also fiercely attacked, the enemy swarming down in great numbers upon the French, and the 9th Cheshires. The former were driven off the Aubilly Ridge, and the latter had to give ground before the rush.

General Jeffreys, who was on the spot, ordered an immediate counter-attack of the 2nd Wilts to retrieve the situation. Before it could develop, however, the French were again advancing on the right, together with the 4th Shropshires. A local counter-attack had also been delivered by the 9th Cheshires, led on horseback with extreme gallantry by Colonel Cunninghame. His horse was shot under him, but he continued to lead the troops on foot, and his Cheshire infantry followed him with grim determination into their old positions. The ground was regained though the losses were heavy, Colonel Cunninghame being among the wounded.

The attack of the 2nd Wiltshires had meanwhile been developed, and was launched under heavy fire about seven in the evening, moving up to the north of Chambrecy. The position was gained, the Wiltshires connecting up with the Cheshires on their right and the Gloucesters on their left. Meanwhile, advances of the enemy on the flank were broken up by artillery fire, the 87th and 88th Brigades of guns doing splendid work, and sweeping the heads of every advance from the Tardenois-Chambrecy road. So ended another very severe day of battle. The buffer was acting and the advance was slowing. Already its limit seemed to be marked.

On the morning of May 31 the British position extended from a line on the left connecting Ville-en-Tardenois and Champlat. Thence the 57th Brigade covered the ground up to the stream which runs from Sarcy to Chambrecy. Then the 56th Brigade began, and carried on to 1000 yards east of the river Ardres. The line of battalions (pitiful remnants for the most part) was from the left, 10th Warwicks, 10th Worcesters, 8th Gloucesters, 2nd Wilts, 9th Cheshires, 8th Staffords, and 4th Shropshires. Neither brigade could muster 1000 rifles, while the 58th Brigade in reserve was reduced to three sapper field companies, the personnel of the trench-mortar batteries, and every straggler who could be scraped up was thrust forward to thicken the line.

The German attack was launched once more at 4 P.M. on June 1, striking up against the Fortieth French Division and the left of the British line. Under the weight of the assault the French were pushed back, and the enemy penetrated the Bonval Wood, crossed the Tardenois-Jonchery road, and thrust their way into the woods of Courmont and La Cohette. Here, however, the attack was held, and the junction between the French and the Warwicks remained firm. The front of the 57th Brigade was attacked at the same time, the 8th Gloucesters and the 2nd Wilts on their right being very hard pressed. The enemy had got Sarcy village, which enabled them to get on the flank of the Gloucesters, and to penetrate between them and the Wiltshires. It was a very critical situation. The right company of the Gloucesters was enfiladed and rolled up, while the centre was in deadly danger. The left flank and the Worcesters held tight, but the rest of the line was being driven down the hill towards Chambrecy. A splendid rally was effected, however, by Captain Pope of B Company, who led his west countrymen up the hill once more, driving the enemy back to his original line. For this feat he received the D.S.O. At this most critical period of the action, great help was given to the British by the 2nd Battalion of the 22nd French Regiment, led in person by Commandant de Lasbourde, which joined in Pope’s counter-attack, afterwards relieving the remains of the Gloucesters. Lasbourde also received the D.S.O.

The success of the attack was due partly to the steadiness of the of the 10th Worcesters on the left, who faced right and poured a cross-fire into the German stormers. It was a complete, dramatic little victory, by which the high ground north of Chambrecy was completely regained. A withdrawal of the whole line was, however, necessary on account of the German penetration into the left, which had brought them complete possession of the Wood of Courmont on the British left rear. The movement was commenced at seven in the evening, and was completed in most excellent order before midnight. This new line, stretching from Quisles to Eligny, included one very important position, the hill of Eligny, which was a prominence from which the enemy could gain observation and command over the whole valley of the Ardres, making all communications and battery positions precarious. The general order of units in the line on June 2 was much the same as before, the 5th South Wales Borderers being held in reserve on the left, and the 2/22nd French on the right of the Nineteenth Division. These positions were held unbroken from this date for a fortnight, when the division was eventually relieved after its most glorious term of service. The British Ninth Corps was busily engaged during this time in reorganising into composite battalions the worn and mixed fragments of the Eighth, Twenty-fifth, and Fiftieth Divisions, which were dribbled up as occasion served to the new battle-line. A composite machine-gun company was also organised and sent up.

Several days of comparative quiet followed, during which the sappers were strengthening the new positions, and the Germans were gathering fresh forces for a renewed attack. Congratulatory messages from General Franchet d’Esperey, the French Army Commander, and from their own Corps General put fresh heart into the overtaxed men. There was no fresh attack until June 6. On that date the line of defence from the left consisted of the Fortieth French Division, the Eighth Division Composite Battalion (could a phrase mean more than that?), the 10th Warwicks, 10th Worcesters, 8th Gloucesters, 58th Brigade Composite Battalion, 9th Cheshires, 8th North Staffords, 4th Shropshires, and Twenty-eighth French Division. At 3 A.M. there began a tremendous bombardment, mostly of gas-shell, which gave way to the infantry advance at 4 A.M., the attack striking the right and centre of the British line, in the section of the all-important Bligny Hill. As the enemy advanced upon the front of the 58th Composite Battalion, the men who were the survivors of the 2nd Wilts, 9th Welsh Fusiliers, and 9th Welsh, fired a volley, and then, in a fashion which would have delighted the old Duke, sprang from their cover and charged with the bayonet, hurling the Germans down the slope. It was a complete repulse, as was a second attack upon the front of the Gloucesters and Worcesters who, with a similar suggestion of the legendary Peninsula tactics, waited till they could see their foemen’s eyes before firing, with the result that the storming column simply vanished, flinging itself down in the long grass and hiding there till nightfall. There was no attack on the left of the line, but the 9th Cheshires and the North Staffords both had their share in the victory. The Twenty-eighth French Division on the right had given a little before the storm, and the British line was bent back to keep touch. Otherwise it was absolutely intact, and the whole terrain in front of it was covered with German dead.

The German is a determined fighter, however, and his generals well knew that without the command of Bligny Hill no further progress was possible for him in the general advance. Therefore they drew together all their strength and renewed the attack at 11 A.M. with such energy and determination that they gained the summit. An immediate counter by the 9th Cheshires, though most gallantly urged, was unable to restore the situation, but fortunately a battalion was at hand which had not lost so grievously in the previous fighting. This was the 4th Shropshires, which now charged up the hill, accompanied by the remains of the undefeated 9th Cheshires. The attack was delivered with magnificent dash and spirit, and it ended by the complete reconquest of the hill. For this feat the 4th Shropshires received as a battalion the rare and coveted distinction of the Croix de Guerre with the palm. This local success strengthened the hands of the French on the right, who were able in the late afternoon to come forward and to retake the village of Bligny. June 6 was a most successful day, and gave fresh assurance that the German advance was spent.

There was no further close fighting in this neighbourhood up to June 19, when the young soldiers of the Nineteenth and other divisions were withdrawn after a sustained effort which no veterans could have beaten. In the official report of General Pelle to his own Higher Command, there occurs the generous sentence: “L’impression produite sur le moral des troupes françaises par la belle attitude de leurs alliés a été très bonne.” Both Allies experienced the difficulty of harmonising troops who act under different traditions and by different methods. At first these hindrances were very great, but with fuller knowledge they tended to disappear, and ended in complete mutual confidence, founded upon a long experience of loyalty and devotion to the common end.

From this date until the end of June no event of importance affecting the British forces occurred upon the Western front. The German attack extended gradually in the Aisne district, until it had reached Montdidier, and it penetrated upon the front as far south as the forest of Villers-Cotteret, where it threatened the town of Compiègne. In the middle of June the German front was within forty miles of Paris, and a great gun specially constructed for the diabolical work was tossing huge shells at regular intervals into the crowded city. The bursting of one of these projectiles amidst the congregation of a church on a Sunday, with an appalling result in killed and wounded, was one of those incidents which Germans of the future will, we hope, regard with the same horror as the rest of the world did at the time.

The cause of the Allies seemed at this hour to be at the very lowest. They had received severe if glorious defeats on the Somme, in Flanders, and on the Aisne. Their only success lay in putting limits to German victories. And yet with that deep prophetic instinct which is latent in the human mind, there was never a moment when they felt more assured of the ultimate victory, nor when the language of their leaders was prouder and more firm. This general confidence was all the stranger, since we can see as we look back that the situation was on the face of it most desperate, and that those factors which were to alter it—the genius of Foch, the strength of his and of the reserves, and the numbers and power of the American Army—were largely concealed from the public. In the midst of the gloom the one bright light shone from Italy, where, on June 17, a strong attack of the Austrians across the Piave was first held and then thrown back to the other bank. In this most timely victory Lord Cavan’s force, which now consisted of three British Divisions, the Seventh, Twenty-third, and Forty-eighth, played a glorious part. So, at the close of the half year Fate’s curtain rang down, to rise again upon the most dramatic change in history.

THE END

Map to illustrate the British Campaign in France and Flanders