Your property settlement

Now that you’ve sorted out your children, if you have them, it’s time to talk about property. Oftentimes child and property matters are negotiated at the same time, especially if you’ve managed to mediate your outcome, but sometimes finalising your property settlement is a major sticking point and can take years to resolve.

Property settlements, especially those including the transfer of shares, investment property, companies or assets from a company, can have serious taxation implications and you should discuss these with your lawyer and your accountant.

De facto threshold

The Family Law Act says that the court can make a property order in de facto matters only if:

• the length of the relationship is two years; or

• there is a child of the relationship; or

• the applicant made ‘substantial contributions’ and it would be an injustice if the court did not make an order; or

• the relationship was registered under a law (civil union).

‘Substantial contributions’ would be:

• financial contributions to the acquisition, conservation or improvement of property—so, actually putting money into your property

• non-financial contributions to the acquisition, conservation or improvement of property—so, something like significant renovations or building, or working in a family business (i.e. doing the books) or on a family farm for no pay for years

• welfare contributions—caring for a child or doing the majority of the housework.

Time limits

Don’t forget the time limits! They have a tendency to sneak up and catch people out.

• For married people, the time limit is twelve months after the date that a divorce order takes effect or decree of nullity is made, although consent orders can be made out of time without the court first giving leave.

• For de facto partners, the time limit is two years after separation, and consent orders cannot be made out of time without the court first giving leave, so really watch this time limit.

If you miss these time limits, you need the leave of the court to proceed and the judge may not necessarily give you this leave.

What is a property settlement?

A property and financial settlement is an agreement reached between you and your former spouse, or one imposed on you by the court, relating to the division of the assets held by one or both parties to the marriage, including:

• superannuation (this is a major source of conflict—many people can’t believe they have to split their super)

• property (including any investments and the marital home, and property owned before marriage)

• business interests

• stocks

• bonds

• inheritances

• savings

• household goods, including artworks

• cars and boats

• personal effects, such as jewellery.

Liabilities of the marriage, such as credit card debts, mortgages, and other debts such as personal loans, will also be taken into consideration. It doesn’t matter if property is held in just one spouse’s name or not—it all goes into the asset pool for divvying up. There’s also no rule that says the assets and liabilities must be divided fifty-fifty—there’s a complex formula that we’ll go into more detail about later.

You don’t need to wait to finalise your divorce before you start your property settlement—you can get it underway as soon as you separate, if you want. Bear in mind that assets are valued as at the date of any order/trial/mediation, so the sooner you have things sorted out, the sooner you can both financially move on.

The family law courts have had power to make orders about superannuation since 28 December 2002; before, superannuation was treated as a financial resource. Back in those days it was not uncommon for the husband to have a lot of super and the wife to have very little super, so the wife would receive all or most of the assets because the husband was going to retire comfortably with his super. The government recognised that this was not a great way to organise finances for either party, so super splitting was brought in. You can also have flagging orders but these are rare. A flagging order is where the court orders that no action is to be taken in relation to splitting the super until the value of the super account is settled. Once the order is lifted, the super can then be split.

Super split—where super is ‘split’ from one party’s super account and put into the other party’s super account, either by a superannuation agreement (usually contained in a binding financial agreement) or by court order.

Some schemes, such as the Defence Force Retirement and Death Benefits Scheme (DFRDB), can be tricky to deal with. Some or all of the DFRDB is generally paid as a guaranteed income for life, rather than as a lump sum, so you should seek advice.

How do I finalise my property settlement?

A property settlement can be finalised a few different ways.

By agreement

You and your former spouse can agree to divide your assets and liabilities without any outside interference. This is often an option where there are very few assets and even fewer liabilities. For example, if you both have roughly the same amount of superannuation, have no children, have only been married for a few years, earn the same amount of money, and are currently renting, you may just decide to divide up the savings account and go your separate ways. The risk here, of course, is that there’s nothing to stop your former spouse from coming after you for more money down the track. An agreement between the two of you isn’t legally binding and you will not be able to transfer assets without paying stamp duty.

If you have a lot of assets, and you and/or your spouse earn high incomes (known as a high-value divorce), you must seek legal advice. Don’t just believe your ex when they say they’ve worked out a fair and reasonable settlement. We know of many cases where one partner has been told that they’re getting a fair deal, when in fact they were entitled to much, much more.

By binding financial agreement

A binding financial agreement (BFA) is a written agreement reached by consent, usually negotiated by your lawyers, that finalises your property settlement without having to go to court. You both have to have independent legal advice and a certificate from an Australian legal practitioner saying you’ve been legally advised on the effect of the agreement on your rights and on the advantages and disadvantages to you at the time of signing. The court does not consider the BFA unless one of the parties requests that it be set aside, and there’s no requirement that it be ‘just and equitable’—that is, a fair deal for both of you.

If a BFA meets all of the criteria set out in the Family Law Act regarding independent legal advice and the court does not find that it should be set aside because of, for example, fraud, misrepresentation or a person trying to use the BFA to defraud a creditor by putting everything into their spouse’s name, the court will usually follow it—so it is actually binding. The BFA has to be done properly, however, and according to the Act, or a court can find that it is not binding and so can set it aside.

Reputable lawyers will refuse to give advice on a BFA if there is any sign of duress or fear from either of the parties. If you want a BFA a week before your wedding, or settlement of a house purchase, it is likely that your lawyer will say, ‘No way’ when asked to give advice. In late 2017 the High Court considered a case where a BFA was signed four days before a wedding. The parents and sister of the bride-to-be had flown to Australia from overseas, guests had been invited, the dress had been made and the reception booked. A further, similar BFA was signed just after the wedding. The parties later separated and the wife asked the Federal Circuit Court to overturn the agreements. The matter went on appeal to the Family Court and then to the High Court, which held that the husband took advantage of the wife’s vulnerability to obtain the agreements, which were entirely inappropriate and wholly inadequate. Although the husband had died by the time the matter was heard in the High Court, the outcome was that the agreements were overturned and the wife’s claim for property settlement would be heard in the Federal Circuit Court at a later date.75

This is because it is pretty well established that weddings and purchasing houses are expensive and stressful events, and being jilted at the altar, possibly being left without a home and maybe with visa issues (and potentially being sued in the process) is a huge fear for some people.

In one case, the judge, not surprisingly, found that the husband threatening the wife with prosecution for forgery if she did not sign a BFA was duress and set the BFA aside.76

By consent orders

Consent orders are drafted by you, or your lawyer, or your ex or their lawyer, and they must be submitted to the court for consideration. A registrar (again, an experienced lawyer employed by the court) will consider whether the parenting arrangements are in the best interests of the children and whether the effect of the property orders is just and equitable in all the circumstances.

If they fail either of these, then the registrar can reject them or ask that parties give an explanation of how on earth they think their proposal is in any way just and equitable or in the best interests of the children.

Consent orders can include your parenting arrangements and your financial arrangements in the one document—they do not need to be separate. So, you can have one application for consent orders for both issues.

By orders of the court

If you cannot reach a mutual agreement as to the finalisation of your property agreement, you can apply to the court to make one for you. You don’t have to get your ex to agree to this—you can just make the application.

In Chapter 6, we discussed what happens when you commence legal proceedings, and what happens when you actually go to court. The procedure is pretty much the same for property matters.

Although an application to the court should be a last resort, it can be necessary if negotiation is dragging on, one party is stalling or it is becoming a huge source of stress for you—this is a hard thing to agree on! If a party seems to have disappeared all the assets or is threatening to disappear all the assets, then court is sometimes necessary.

Your lawyer (or you, if you’re self-representing) will firstly decide which court to file in—the Family Court or the Federal Circuit Court. The Family Court can hear matters that contain certain, more serious, issues, if the hearing will take longer than four days of hearing time. Otherwise, your matter will most likely be heard in the Federal Circuit Court.

As when making a decision about whether to make consent orders or not, the court has to make a decision that is just and equitable in all the circumstances and the same factors will apply. For considerations involving the kids, again refer back to Chapter 6.

What property orders can a court make?

The court can make orders declaring that a party owns property, for the alteration of property interests,77 and injunctions to protect persons or property.78

The power to adjust property interests is pretty far reaching and can include making an order that a home be transferred to either party or a child to the marriage, or that money be paid to either party or to the child of a marriage. The court also has power to order that a party’s property vesting in a bankruptcy trustee be transferred to the non-bankrupt spouse or to a child of the marriage, or that a bankruptcy trustee pay money to the non-bankrupt spouse or to a child of the marriage.

What does the court have to consider when making property orders?

Before making orders altering property interests, the court has to firstly consider whether it is ‘just and equitable’ to even make orders. Then the court has to consider:

• What the net property pool is (that is, all the assets and liabilities must be considered, no matter when they were acquired—even post-separation assets).

• Who made what contribution to the property pool (financial contributions like income and inheritances, nonfinancial contributions like renovations or working for free in the family business and welfare contributions as the primary homemaker or parent) before, during and after the relationship.

• What each party’s future needs are (including the age, state of health, income, property, earning capacity, commitments necessary to support themselves or children or other dependents; the extent to which the party whose maintenance is under consideration has contributed to the income, earning capacity, property and financial resources of the other party; the duration of the marriage and extent to which it has affected either party’s earning capacity; the financial circumstances of any repartnering).79

• Whether the effect of the orders is just and equitable in all the circumstances, including if the orders have an effect on the earning capacity of a party (especially in matters involving the family farm or business).

Duty of disclosure

Each party to a property settlement matter has a duty to make full and frank disclosure of their financial circumstances. Failure to do this may not only result in a very annoyed judge, but could result in that judge making adverse findings regarding the failure to disclose, and also very expensive costs orders against the party who failed to comply with the duty to make the disclosure. It also just drags the matter out needlessly and may make your ex’s lawyer suspicious that you are hiding something, and so they may not only look a little closer than normal into what has been provided, but also start asking the court to issue subpoenas to your bank, the Australian Tax Office, your accountant, Sportsbet, the TAB, and possibly the casino closest to you for your membership to the high roller’s club.

Lawyers can and do go through bank account statements and can and will find things like those funds you’ve transferred to a new partner or the hundreds and thousands spent on online gambling. In this way, usually we can trace the meals out with the new partner or the lingerie or adult toys bought on the joint credit card. Occasionally we find things like visits to brothels paid for on the credit card attached to the family business.

To be clear, we’re not particularly interested in your sex life and there is nothing we have not seen before (and sometimes wish we could unsee), but if you’re trying to convince a court that a post-separation credit card debt should be included, then payments to adult shops with your new partner are not going to help your case, or, indeed, your post-separation relationship with your ex.

Similarly, visits to brothels paid for on the company credit card will not help your argument that the business is all but insolvent. Finding a small fortune has been spent on gambling may also result in an pretty valid argument that your ex should get whatever is left, since you’ve had your fun already.

The net ‘property pool’

In some matters, even establishing what the assets and liabilities are—the property pool—is a nightmare. Common problems are that you and your ex can’t agree on ownership of assets, or the value of assets, or whether funds received from family were a loan or a gift. It can take quite a lot of patience to sift through bank accounts or layers of family trusts and companies to see where money has gone. This can be particularly difficult where there are family farms or companies and everyone weighs into the matter, and all of a sudden your second uncle twice removed is making a claim over the family farm.

If a party has sneakily transferred a property into their best friend’s name, then you can expect the court will undo this transaction and probably make a costs order as well.

If a party has sold a property to a completely innocent third party who has nothing to do with any of this mess, then the court can take any losses incurred by the other party into account when making a property order.

As part of the duty of disclosure that we have discussed, each party must disclose what they actually own. A lawyer may also search registers such as land titles, share registers and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC). A lawyer may comb through all available documents, so you can pretty much bet that if someone is hiding something, a family lawyer will find it. For example, it’s always interesting when you find the signature of a spouse as a joint venture partner on a mortgage lodged with land titles, when the spouse is claiming that they have nothing to do with a major development that they were very involved in only twelve months before.

If you and your ex cannot agree on the value of property, then get it valued by a registered valuer early on. Valuers generally charge less than what you’ll pay for a bunch of letters between lawyers arguing about the valuation of a house or your prized Holden Monaro. Market appraisals by real estate agents are not evidence of value, they are only indicative and useful in the early days of a separation as a guide to a property’s value. Parties may agree to accept a market appraisal in mediation or in negotiations, but they are not good evidence for the court if the matter is being litigated. Only experts can give evidence of opinion and the opinion must be based on their particular expertise using the methodology appropriate to value the particular asset.80

Sometimes you and your ex won’t even be able to agree on a valuer. If this happens, the panel approach works well. One party puts forward a panel of three registered valuers and the other party has seven days to nominate one of them; failing that, the first party nominates the valuer. Sometimes you need an order to force the other party to have property or chattels valued. This is frustrating because the court is most likely going to make that order and so it’s all really just a waste of time and money.

Family lawyers like neat balance sheets showing the assets and liabilities with their values, preferably as valued by a registered valuer. That gives everyone something to work off and it’s all admissible in court, if it comes to that.

As we’ve touched on already, sometimes a client will tell Rebekah that their ex owns four investment properties, a share portfolio and a Maserati but they themselves own nothing, because it’s all in their ex’s name. To which Rebekah answers that this doesn’t matter one little tiny bit, unless, of course, all the assets were acquired before the marriage and there’s an iron-clad pre-nup in place. Which usually they weren’t and usually there isn’t.

Any assets acquired during the relationship—and even before, in many cases—are considered part of the asset pool, regardless of which party’s name it is in. Make sure that you tell your lawyer about every single one of your ex’s assets, including cars, boats, share portfolios, property, artwork, businesses, tools of the trade, jewellery and household items (as well as your own).

Usually all assets are included in the property pool, no matter when or how they were obtained. There can be arguments about whether assets received by way of inheritance or after separation should be put in a separate property pool, but they will still be taken into account. So yes, your tools and your jewels are all part of the property pool, even if they were a gift from your ex to you.

If there is an argument about the value of such assets as jewels, cars, tools or furniture (also known as chattels), then get a joint valuation by a registered chattels valuer (now, there’s a fun job in a growth industry!) This will save time and possibly money and give everyone a basis to negotiate from.

Usually, unless you have highly collectable cars or antiques, chattels are worth surprisingly little. Jewellery is generally worth less than a quarter of what you paid for it, which seems weird because there aren’t really any one carat diamond rings for $2000 floating around (we know, because we’ve looked).

So, it is important to work out the property pool, which is done by using a list like this:

Asset/Liability |

Ownership |

Estimated value |

Home: (address) |

|

|

Investment properties: (address/es) |

|

|

Motor vehicle/s: (year/make/model) |

|

|

Boat/s: (year/make/model) |

|

|

Cash in bank accounts: (account number/s) |

|

|

Investments: (type) |

|

|

Shares: (company/amount/type) |

|

|

Business: (name ABN) |

|

|

Chattels: (antiques, jewellery, tools, coins, furniture etc.—list) |

|

|

Rental bond: (Agent/landlord) |

|

|

Frequent flyer points: |

|

|

|

|

|

Expected money from employment: (redundancies, long service leave that can be taken as cash, bonuses etc.) |

|

|

Liabilities: |

|

|

Home loan/s: (bank/account number/s) |

|

|

Investment property loan: (bank/account number/s) |

|

|

Investment loan: (bank/account number/s) |

|

|

Line of credit: (bank/account number/s) |

|

|

Credit cards: (bank/account number/s) |

|

|

Motor vehicle loans: (creditor/account number/s) |

|

|

Personal loans: (creditor/account number/s) |

|

|

Hire purchase/leases: (creditor/account numbers/s) |

|

|

Tax liabilities: |

|

|

School fees: |

|

|

Contributions

In considering what order to make (if any order is to be made), the court must consider contributions. These are:

• financial contributions made to the acquisition, conservation or improvement of any of the property, and these contributions can be from the sale of property, from income, a gift from a third party (such as a parent), an inheritance, compensation payment or redundancy

• non-financial contributions, such as renovations or working with no pay in a family business

• welfare contributions, including contributions made in the capacity of homemaker or parent.

Usually, in a long marriage where you may have been at home with the kids and your ex may have been working, or you both worked and parented at different times and in different ways, it will not matter to the court who did what. Unless someone brought in a lump sum from a pre-existing house or an inheritance, the court will generally consider your contributions to be ‘equal or thereabouts’. The idea that one party could be said to have made a ‘special contribution’ because they were a very special and important super genius, whereas you were just a stay-at-home parent, has been emphatically rejected by the Family Court in most cases.81

Just to be clear—if you have been the stay-at-home parent, in the eyes of the court you have contributed just as much as the wage-earner. Rebekah has had matters where she has acted for a wife who was married for twenty or thirty years, who has been the stay-at-home parent of a gaggle of children, the bookkeeper of the family business and the general slave of the world for her family, only to have the husband suggest that as she didn’t ‘work’, she shouldn’t get anything. The court usually has other ideas.

Pre- and post-separation contributions can be important. For example, if you inherit a large amount of money before the relationship or late in the relationship or after separation, or you win the lottery, or you save a significant amount of money from your post-separation income, these funds may be treated as a separate pool.

The next thing that the court looks at is the factors set out in section 75(2) of the Family Law Act 1975, usually referred to as the future needs of each of the former couple. The importance of these factors will differ between cases involving short relationships with no children, and very long relationships with children.

In short relationships with no children, usually the relationship has not really changed either of the former couple’s financial situations that much, so a disparity of income won’t be that significant. Exceptions could be if the wife gave up a job so as to move to support the husband’s job or to work in the family business.

In short relationships with children, the questions of who did the most caring for the child or children, and any disparity of income, will become important.

In lengthy relationships with children (whether the kids are now adults or not) there is traditionally a difference in income, if one of the couple has stayed at home and the other went out to work. Sometimes the primary earner is upset because they feel like they have sacrificed time with their kids in order to work, and now they are being ‘punished’. Conversely, the primary parent/homemaker may be upset because they sacrificed their career and are now faced with an uncertain financial future. These are not easy questions to answer, but the court will take the view that consciously or unconsciously, the couple adopted certain roles in the relationship, which led to a difference in financial circumstances and must be addressed so that any orders are ‘just and equitable’. It might be decided that the person in the weaker financial situation will get an ‘adjustment’ of between 5 to 20 per cent, so the final division of property is something like 60 per cent to the wife and 40 per cent to the husband.

Just and equitable

The final consideration is about stepping back and seeing if the orders are ‘just and equitable’ in all the circumstances. This can include whether there is any impact on earning capacity (if one of the assets being dealt with in the orders earns income, such as a family farm or business). Or, perhaps, it will become clear that one party is getting all of the tangible assets, like two houses and the car, and the other is just getting super, and that this may not be exactly fair.

Case study—John and Jane

John and Jane had been married for twenty years and had two boys together. John was a public servant and Jane a personal assistant. Jane stopped working for a while when the boys were born and then returned to work part time so that she could still get the boys to their football training and music lessons.

John and Jane were both active in the community and supported groups like the boys’ school and local football club. Jane was on the school parents’ committee and John was on the committee for the football club.

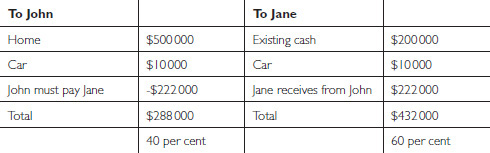

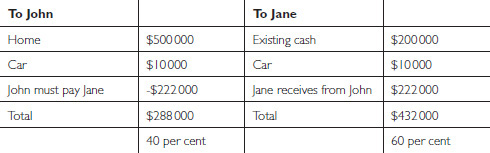

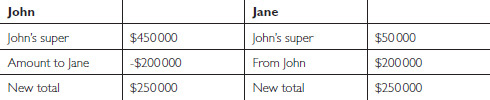

When they separated, the boys were adults and John and Jane had a total non-superannuation pool of $720 000 (they owned their home outright and it was worth $500 000, had some savings, of $200 000, and cars worth about $10 000). John had a lot more super than Jane. John was also earning $200 000 and Jane $50 000. After a hearing, the judge decided that it was just and equitable for the super to be equalised and, regarding the rest of the property, for Jane to receive 60 per cent of the property pool and John to receive 40 per cent. The outcome looked like this (John needed to borrow money to pay Jane, as John wanted to keep the house):

Non-super:

Common questions and issues in property matters

We know this is all a bit complicated. Like much of family law, how property matters are determined really depends on the circumstances of your case. But in every property matter, we see the same issues coming up all the time. Here we’ve summarised the more frequently asked questions.

Can I get a stamp duty exemption?

Each of the Australian states and territories has an exemption from paying stamp duty on the sale of a property if the transfer of property from joint names to one name, or from one name to another name, is done because of a BFA or court order (including consent orders). For example, if you buy your ex out of your joint property, their name will be removed from the title, and ordinarily stamp duty would be payable on that transaction unless you are eligible for the exemption.

Case study—Fred and Jamie

Fred and Jamie had been in a de facto relationship for ten years. When their relationship ended, Fred made Jamie an offer that he would buy Jamie out of the home they shared. The house was in their joint names, and so after finalising their BFA, the transfer of the home into Fred’s sole name was exempt, and Fred saved a substantial amount of money.

Stamp duty can, of course, be more expensive than the cost of getting a BFA or a consent order, so this is a really important consideration, especially when stamp duty on some houses can be $100 000 or more.

Because stamp duty is a state and territory tax, the schemes differ slightly, and it’s important that you make sure the arrangements you enter into will attract a stamp duty exemption. Your lawyer can help you with this, or you can find out more by googling ‘stamp duty exemption family law’ and then the name of your state or territory.

Is it a gift? Is it a loan? No, it’s a mess!

It is very common, especially in these times of high property prices, for parents to give money to an adult child to help them buy a house. Everyone merrily assumes that they all knew what each other meant. Usually when there is then a separation, one party suddenly discovers that the money was ‘always’ going to be repaid to the parents if the home was sold.

These cases cause endless litigation and high levels of emotion and therefore are super expensive. They can also cause huge problems within extended families as everyone gets to stick their two cents in. This does not bode well for those times when you need everyone to turn up and pretend to play happy families, such as at weddings and graduations.

Unless everyone has an attack of the reasonables, it is up to the judge hearing the case to decide whether the funds were a loan or a gift (and therefore a contribution made on behalf of the party receiving it) and whether the funds should be repaid on the sale of an asset. Judges have discretion, but they are also guided by past cases. The Family Court has found that it is up to the judge to decide whether the allegation that a loan is a loan and not a gift is true,82 and the judge will look at things like:

• Is there a loan agreement clearly setting out everyone’s rights and responsibilities?

• Is the loan registered as a mortgage?

• Has there been any acceptance in writing by either party that it was a loan?

• Have regular repayments been made?

• Have homes been sold after the funds were received, with no demand for repayment?

• Were similar amounts given to other siblings?

• Were wills amended to reflect the gift?

Usually it is not clear cut—some things will suggest loan, some things will suggest gift.

The only thing that is certain is that it will be very, very expensive to try to sort it out as it will take many affidavits, days in court and arguments for the judge to get to the bottom of it all. One thing is for sure, no one will be happy. The same issues arise if a parent dies and the other siblings suddenly realise that one sibling received a heap of money.

Case study—Tina and Michael

Tina and Michael were married for ten years. Four years into the marriage, Tina’s mother, Meredith, gave Tina $500 000, as an ‘early inheritance’. Meredith had sold the family home and downsized, and so wanted to help Tina and Michael establish themselves. Tina and Michael used the money to buy a home in Sydney’s inner west, which they otherwise would not have been able to afford.

When the marriage ended a year later, Michael proposed a fifty-fifty property split. Tina resisted this, arguing (eventually in court) that the $500 000 given to her by her mother was hers alone.

The fact that it was a gift solely to Tina and was specified as an inheritance given early, in text messages between Tina and Meredith, became crucial to the case. The court found that the money was only meant to be given to Tina, not Michael, and so was excluded from the property pool.

If you think your ex is hiding assets, has a secret bank account, has regularly been taking trips to the Cayman Islands, is an international drug lord, or seems to be spending a lot of time in his mistress’s suspiciously new $2 million apartment, then a forensic accountant can help you find the money and get your fair share of it. A forensic accountant is a specialist accountant who provides advice that is admissible (that is, can be used as evidence) in court.

Your lawyer will have a forensic accountant they use—if you’re in this situation, and you think there’s a fair bit of cash you don’t know about, then you must get a lawyer. Don’t self-represent in these circumstances, because if there’s money being hidden, you can bet your ex will have a lawyer.

If the judge comes to the conclusion that it is more probable than not that a party has hidden assets away, then they can divide what is left accordingly—even to the extent of giving the innocent party everything else.

My ex has spent all the money on gambling/drinking/who knows what

You can’t get blood out of a stone, and if your ex has indeed spent all the money, and there are no other assets, then there’s not a huge amount you can do except take up voodoo and hope the karma bus gets them. If there are some assets left, then the court can, in certain circumstances, make orders that you get all or most of whatever is left.

If assets have been given away, the court can undo that or make orders that you get more or all of whatever is left. The same can apply if assets have been wasted on purpose or recklessly wasted (such as on extravagant, first class overseas holidays), as long as there are money or assets left to be divided.

My ex won’t pay our kids’ school fees—what do I do?

The court takes the view that children are entitled to a public school education, and if parents cannot afford private school fees, then the kids cannot go to a private school. This can be a really hard situation, especially if the kids have to be pulled out of the school.

If there was a clear agreement that the children go to a particular school, and the parents can demonstrably afford the fees, then the DHS can change the child support assessment to make it so.83 This will probably require a special assessment, which we talked about in Chapter 7.

It’s also worth talking to the school—if your child is in year eleven and only has a little while to go, the school will often agree to let you pay the money back over a period of time, or might agree to a bursary—so long as your kid hasn’t been a right little pest for the past five and a half years, that is!

My ex cut off my access to our joint bank account—what can I do?

Firstly, don’t panic; they have probably been told to do this by their lawyer or they read about it on some website. You must go and see your bank as soon as possible if your ex has done something sneaky like change all the passwords for your accounts. If your name is on that account, you can have your access reinstated. You can also request that the account is made subject to a ‘two to sign’ requirement so your ex can’t take all the money and move to Ipanema.

You can also see a lawyer or community legal service and make a formal request for spousal maintenance (which we’ve talked about earlier) if you are unable to live in the meantime, particularly if you’re a stay-at-home parent and your ex has stopped paying their wages into your joint account.

My ex has run up a huge credit card bill post our split and says I have to pay it—what are my rights?

Let’s be clear here, the court has to make orders that are ‘just and equitable’. Paying for your ex’s new Jimmy Possum furniture, legal fees, his RSVP account or her meals out with her new boyfriend will not be okay (and believe us, these will show up on the statements—hilariously sometimes the RSVP charges come after the meals out with the new partner, leading to some very awkward scenes in mediation when the ex has brought the new partner along for ‘support’ and we all go through the credit card statements together).

Unless there is a court order saying differently, each party bears their own costs, and unless there was an agreement, paying for legal fees from joint funds will usually result in that money being returned to your ex, if there is any money left.

No court is going to make you pay for your ex’s spending spree. They will be responsible for their own post-separation credit card debt unless it is reasonable expenditure for the benefit of the family. Any such expenditure from joint accounts will come out of their cut of the money (if—and it’s a big if—there is any left).

We have no assets and a lot of debt—what happens now?

This can be very difficult as there must be property for the court to have the power to make orders about how that property is divided. You can’t divide nothing. (There’s some maths equation about that, isn’t there?)

Usually parties have some superannuation at the very least and this gives the court the ability to alter property interests, but sometimes there’s no money or assets at all. The court cannot magic up assets to satisfy a debt or to provide a settlement.

This is because the power of the court to make orders comes from the legislation, and the legislation talks about making orders about altering property interests. The court can make orders that a party refinance a debt, or that an asset be sold to pay down debt, or that a party be solely responsible for a debt.

If your ex has no money or assets, then you may simply be throwing good money after bad by spending more on legal bills. It is a cost-benefit analysis of whether it is worth pursuing them, and if there’s no money, then it’s probably not worth it.

‘I’d rather pay the lawyer than my ex’ and other lunatic ideas

A very easy trap to fall into is spending a great deal of money on trying to ‘beat’ your former spouse in court. One or both parties may decide that they’re going to spend every cent they have, and quite a bit more on top, in order to ‘win’ against their ex. The thing is, nobody gets a trophy at the end of litigation. You just get a bill from your lawyer. We’ve all heard stories about people who litigate for years over a tea set. These sorts of people don’t need lawyers, they (genuinely) need a psychologist.

Case study—Annabel and Tom

Annabel had been married to Tom for twenty-five years before she finally left, and eventually filed for divorce. It was a bitterly unhappy marriage at the end, marred by infidelity and horrible fighting. The couple had four children, two of whom still lived at home, and assets in excess of $4 million.

The marital home was a five-bedroom estate in the Perth suburb of Subiaco, and both Annabel and Tom were highly paid medical professionals, but a protracted legal battle resulted in each party walking away with less than $500 000 each—just enough for them to both buy a townhouse in neighbouring suburbs. Tom had lawyered up first, furious with Annabel for leaving him, and Annabel returned fire, angry with Tom over an affair he had at the end of the marriage, and the matter eventually went to the High Court for determination on an obscure point of law.

Their combined legal bills were over $2 million and the matter raged on for more than ten years. Had Annabel and Tom agreed to a fair division of the assets early in their separation without engaging in litigated warfare with each other, they would have each gotten at least $1 million more.

We have a huge mortgage and my ex is refusing to pay it

If your ex has moved out of the family home, and the mortgage is in joint names, it often comes as astonishing news that they can simply stop paying their share (or the whole thing, if you have been a stay-at-home parent and your ex’s wages paid the mortgage).

If you default on the mortgage (in other words, you stop paying it), your lending institution can (and will) call in the loan. That is, they can force the sale of the house, and you’ll be left with whatever is left over after the bank has taken their money and any other fees you have incurred. You’ll also get a black mark on your credit rating. Banks generally engage very expensive lawyers (even more expensive than your lawyer) and you get to cover this cost as well.

This is the worst-case scenario. To avoid this, if you’re in the position where your ex has moved out and won’t help pay the mortgage, talk to your bank or credit union. They don’t want you to default. They want to help you sort out your situation so they get their money without a lot of tedious extra paperwork. Your lender will have a process to help you get your finances in order until you work out a temporary agreement with your ex, or a final agreement where you either buy your ex out of the house or your ex buys you out of the house, or you sell the house and divide the proceeds with your ex according to your settlement.

Generally the court would expect someone to pay for outgoings (including the mortgage) on a home that they are living in. This expectation can change if you simply cannot afford to pay those outgoings on your own and there is a large disparity of earnings between you and your ex.

Sometimes separations occur where one party is a stay-at-home parent and there are good reasons why they should stay in the home with the children but they cannot afford the mortgage (for example, the house has been modified to be compliant with disability standards for your special needs child). If this is the case for you, and your ex is simply refusing to pay the mortgage, seek advice regarding whether you should apply for urgent spousal maintenance. Spousal maintenance is ordered when one party can afford to pay it and the other party has a need for it because they cannot support themselves due to having to take care of children, or because of advanced age or health reasons. The court must not take into account a means-tested Australian pension when working out if a party has a need for or an ability to pay spousal maintenance.

Child support, which is separate from spousal support, can take a long time to start to be received and this can be extremely scary for the receiving parent. Apply for child support early and get advice if you are being asked to agree to child support being paid as mortgage payments or school fees.

Another option is to sell the home immediately if you can’t possibly pay the mortgage by yourself. In this situation, the proceeds of the sale will be held in trust (by your lawyers) until after final settlement of your property matter, when it is then distributed according to your agreement.

It’s also worth noting that any repayments your ex makes on the mortgage if you have sole occupation of the house may be seen as post-separation contributions and may be taken into account when the settlement is calculated.

Who keeps the pets?

In family law, companion animals are classified as property. Therefore, who gets to keep Fluffy and Rex is a matter of dividing property, and the court can make an order as to who gets to keep the cat or dog or snake or fish. The court considers a few things in assessing who should keep the pets, and these include:

• who has looked after the animal the most (walked it, took it to the vet, fed it and cleaned up after it)

• whose name the animal is registered in

• who can best look after the animal in the new family arrangements (i.e. if you live in an apartment and you’re fighting over a horse with your ex, who lives on a farm, you might not win that one)

• any other factors, such as if the dog is a working dog or the cat is the offspring of the childhood pet of one of the parties.

The court will then make an assessment on the facts, will award the animal some nominal sum as a value (unless it’s a very expensive working dog or show cat), and an order will be made that the animal is the property of one of the parties.

Often, the decision as to who keeps the pets is extremely fraught and not as easy as it appears from the factors above. We’ve heard of a couple who stay together by having an agreement that whoever leaves the marriage first gets the kids, and the other person gets the dog.

Many of us see our animals as family, including us—we have three dogs, four cats and a macaw between us—and the idea of losing your animals is heartbreaking. Lots of separated families get around this by ‘sharing custody’ of the pets—easier when the pet is a dog—so that the dog goes with the kids between houses. This is less easy when your pet is a horse.

It’s also important to be aware that many people stay in abusive relationships because they are afraid that their animals will be hurt if they leave. Many organisations are trying to help those in this situation, and some women’s refuges will take pets. 1800RESPECT can help you make a safety plan to leave an abusive relationship in such a way that your pets will also be protected.

Leaving the marital home

One of the toughest times of divorcing (we seem to say that a lot in this book) is selling or leaving your family home. Sadly, it’s the reality for many separating people. There’s very often just not enough money to be able to rehouse both parties without downsizing or moving to a different, cheaper area. But that doesn’t mean it doesn’t massively hurt. You have probably worked really hard for your home, and you probably love it. You don’t have to own it to love it—it can be just as hard to leave your rented home.

Many people won’t realise the depth of your pain at having to leave your home. They just think, ‘Well, that’s what divorce is!’ but housing insecurity is the major reason many people stay in terrible relationships far longer than they should. The insane cost of housing in many Australian cities and towns is a huge impediment to being able to leave even the worst of marriages.

Legally, whether or not you sell your house after separation comes down to a few things. Can your former partner buy you out of your home? Can you buy your former partner out of your home? How do you feel about taking on a potentially huge mortgage, that you expected to be paying as part of a couple, by yourself?

When your property settlement is being worked through, it will become clearer whether or not you’ll be able to stay in your home. It’s not the case that assets are automatically split fifty-fifty—there’s a very complicated formula for working the division out, which your lawyer will help you with. It all depends on contributions, both financial and non-financial, and things like being the primary carer of small children are taken very much into account, as is superannuation!

No matter what happens in terms of the property, you’ll be very worried about the kids being disrupted, and if you’re the one leaving, it can be an enormous source of guilt when you know you’re the reason (no matter how good your reasons are) why the kids have to leave their home and possibly their schools, friends and community.

Staying in the marital home

This can also be a difficult thing, but, of course, being able to stay in your community at a time of horrible upheaval can be a great relief. At the same time, you’re surrounded by memories of your defunct relationship, good and bad—remember when you bought that couch together? Remember when you threw the mug at that wall and left that dent? Remember having that huge fight over the new TV unit at the Homemaker Centre? Good times, good times.

Additionally, you may have a new mortgage so high you can barely jump over it, and the thought of being solely responsible for all those zeros will keep you awake at night.

A point to consider here—it might be worth thinking about selling if you’re finding your mortgage stress is crippling (mortgage stress is where more than 30 per cent of your weekly earnings after tax are going to your housing costs). You don’t have to give yourself a nervous breakdown trying to stay in your home if it’s too hard. It might be better for you, and your children, to live in a smaller home with a more manageable mortgage than to make yourself sick with anxiety and overwork.

If the home is going to have to be sold, then do it as part of your settlement, because then the costs of sale will be shared. If you end up having to sell six months later, then you may end up paying the real estate agent’s $25 000 commission yourself, and that’s not fair.

As we mentioned earlier in this chapter, if you transfer a property from joint names to your sole name, or from your ex’s name to your name because there are court orders or a financial agreement, then the transfer should be exempt from stamp duty. Sometimes it is well worth transferring property to save the costs of sale (real estate agents and conveyancing fees) and to save having to pay stamp duty on a new home.

When you have the good luck and terrible misfortune of staying in your home, one thing that can help is mixing it up as much as you can. We know that money might be tighter than ever, but even moving furniture around can help, or adding new pillows and throws from Kmart or Target. Getting new bed linen is a priority—no need to sleep in the same sheets, after all!

Tips and traps

When you’re negotiating your property settlement, it can be very hard to remain cool, calm and collected, while still fighting for your fair share. We’ve seen clients forget to mention key assets (this rarely ends well), or give up things they’re entitled to, just to make the matter go away.

While it’s important to give and take in order to reach an outcome, don’t forget to divide, or at least take account of, the following easily overlooked items:

• superannuation—yes, this is property and, yes, the orders can equalise or otherwise ‘split’ (divide) super

• frequent flier points—these are actually quite lucrative and even if you’ve been a stay-at-home parent/spouse while your partner has been a corporate high-flyer, you’ll probably be entitled to at least half of these points

• credit card points—if you or your ex paid all the household expenses on a credit card, then there may be thousands of dollars in points on that card

• hotel memberships that accumulate points (also lucrative)

• any long-term incentives and short-term incentives that form part of your ex’s salary package (also known as bonuses)

• any share allocations you or your ex receives as part of your salary package

• iTunes or Spotify accounts—these can be worth thousands and thousands of dollars—and these days, can be worth as much as traditional music collections, if not more

• long service leave—if this is available as a cash payment, then it is property that can be divided; if it is available only as leave, then it is important to take it into account, as it is guaranteed income

• Defence Force Retirement and Death Benefits Scheme (DFRDB)—you should seek legal advice if you or your ex has a DFRDB pension

• if it applies, try to reach an agreement on airport lounge access memberships, especially if you’ll be travelling frequently with your children. While it won’t be relevant to everyone, in many divorces one or both spouses are corporate types, with significant perks of the job that their ex won’t want to lose. Most of these memberships also extend to the spouse. You should ask your lawyer to negotiate you staying on your former spouse’s membership for as long as possible (one couple we know did this until the wife remarried).

Enforcing property orders

So you have negotiated hard and fair and you have sealed orders or a fully executed financial agreement. Or you have been through the trauma of a trial and the judge has made orders. What happens if your ex simply does not comply with them?

If you are to be paid a lump sum of money or periodic payments of money, then interest is payable if you are not paid. The interest rate is the Reserve Bank of Australia target cash rate that is published on 1 January and 1 July each year plus 6 per cent.84

If you are to be paid a lump sum and a property is to be transferred into your ex’s sole name, then hopefully there are default sale provisions. This means if your ex is unable or unwilling to pay you, or to refinance the mortgage into their sole name, the home is sold so you can be paid and the mortgage can be discharged.

Hopefully there is also an order that the registrar can sign a document if a party refuses to, and some default sale orders. If your ex will not (or cannot) pay you, then you can trigger the default sale orders. If they refuse to cooperate, then the registrar of the court can sign documents like contracts for sale or a discharge of mortgage and/or you can ask the court to appoint a trustee for sale.

If a home is being transferred into one party’s sole name and the other party is being paid out, it is good practice to have default sale orders, especially if the party receiving the property has to refinance a mortgage. Post-GFC and with the tightening of lending practices, sometimes, through nobody’s fault, the person taking the property and the mortgage can’t get finance. If there are no default sale orders, then it is back to the negotiating table or back to court to try to get the orders enforced.

While the court has the power to enforce orders, including changing the parts of the orders that make the orders work,85 appointing trustees for sale, and even imprisonment (yes, really—judges don’t like people ignoring their orders),86 this can be expensive and time consuming. Default sale orders can protect both parties.

Case study—Bob and Amy

Bob and Amy worked out a property settlement and were pretty amicable. Bob was going to keep the family home, refinance the mortgage and pay Amy out. Since they were amicable, they didn’t think they needed to have backup orders about what would happen if Bob wasn’t able to refinance the mortgage or make the payment to Amy. Tragically, about a week after the consent orders were made, Bob was hit by a bus as he was cycling to work. He was in hospital for a very long time and was not able to refinance the mortgage or pay Amy out. In fact, he was not able to make any decisions about his financial affairs for a few months and there was no enduring power of attorney in place. In the end, Amy reluctantly took the matter to court and new orders were made.

The lesson here is that things do go wrong, people do get hit by buses, and you have to have workable alternatives in place.

QUESTIONS FOR MY LAWYER REGARDING MY PROPERTY SETTLEMENT

Once again, this worksheet is so you can jot down any questions you have for your lawyer before you go into the meeting or teleconference. Remembering that lawyers charge up to $600 an hour in six-minute units, it’s very important that you don’t waste your money by not having a really clear idea of what questions you want answered.

Date: |

Date: |

Questions for my lawyer regarding my property settlement |

Answers |

1. |

|

2. |

|

3. |

|

4. |

|

5. |

|

6. |

|

7. |

|

8. |

|

9. |

|

10. |

|

75 http://eresources.hcourt.gov.au/downloadPdf/2017/HCA/49)

76 Tsarouhi v. Tsarouhi [2009] FMCAfam 126.

77 Section 79 Family Law Act 1975.

78 Section 114 Family Law Act 1975.

79 Section 75(2) Family Law Act 1975.

80 Makita (Australia) Pty Ltd v. Sprowles [2001] NSWCA 305 (14 September 2001).

81 Kane & Kane [2013] FamCAFC 205.

82 Biltoft [1995] FamCA 45.

83 www.humanservices.gov.au/customer/forms/cs1970.

84 www.familycourt.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/fcoaweb/rules-and-legislation/rate-ofinterest/.

85 Kaljo & Kaljo [1978] FLC 90-445.

86 PDM & JEM [2006] FamCA 1182 (8 November 2006).