Genesis of the Modern Navy 1957–1959

THE COLD WAR – NUCLEAR, NATO AND NAVAL STRATEGY – THE POST-SUEZ DEFENCE REVIEW AND FLEET REDUCTIONS – CYPRUS EMERGENCY – MIDDLE EAST CRISIS AND OPERATION FORTITUDE – FIRST COD WAR – OPERATION GRAPPLE AND NUCLEAR WEAPONS

FIRST SEA LORDS Admiral of the Fleet the Earl Mountbatten of Burma and Admiral Lambe

SECOND SEA LORDS Admirals Lambe and Holland-Martin

NAVAL MANPOWER 121,500

MERCANTILE MARINE 5,508 merchant ships1

A traditional challenge being flashed from a Royal Navy destroyer

(NN)

At dawn on a clear day in the western Mediterranean two warships, a US cruiser and a British destroyer, were on a converging course some sixty miles south-east of Gibraltar. The sea was flat calm with the early morning sun rising over the eastern horizon. The ships were approaching each other at a combined speed of over twenty-eight knots. When they had closed to within visual range a challenge was flashed from the signal deck of the larger warship, a US heavy cruiser of the 6th Fleet. A short while later, on receipt of the correct identification signal, a brief further message was flashed from the US cruiser: ‘Greetings to the second biggest navy in the world!’ She then courteously dipped her ensign in the traditional salute to the Royal Navy.

An equally brief reply was flashed back from the bridge of the Royal Navy destroyer as she hove to on the cruiser’s starboard bow: ‘Greetings to the SECOND BEST navy in the world!!’ The destroyer then dipped her ensign, acknowledging the salute from the US cruiser.2

This story of the exchange of signals between the Royal Navy and the United States Navy in the Mediterranean, some time after the end of World War II, poignantly summed up the dramatic change of status of the Royal Navy. For nearly 200 years, from the Seven Years War (1756–63) to World War II, the Royal Navy had been the supreme maritime power, exercising command of the sea and dominating the world’s oceans. She had played the key role in supporting and defending the British Empire. At the end of World War II the Royal Navy had 8,940 ships and vessels of all types in commission and 864,000 people in uniform, yet the United States Navy was even bigger. Despite this the traditions, expertise and standards set and maintained by the ‘Senior Service’ of the world’s leading maritime nation remained second to none.

Although the United States Navy had overtaken the Royal Navy in terms of size, Britain still held her position as the world’s greatest maritime nation. The Royal Navy and Merchant Navy combined outnumbered the total number of warships and registered merchant ships belonging to the United States. Britain’s merchant fleet was to remain the world’s largest until well into the 1960s.3 Britain clearly remained a great maritime trading nation dependent on the sea. Over forty years later, in 2001, the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Alan West, stated that ‘The Royal Navy was still the second most powerful Navy in the world and certainly the best.’4

The early post-war years were overshadowed by Britain’s rapid economic, industrial and political decline as she struggled to shoulder the crippling burden of paying the cost of the war and rebuilding her shattered industries and infrastructure. The national debt had soared to a record level and Britain was unable to pay the ‘Lend-Lease’ debt to America at the end of World War II. Britain was forced to take on a further loan of $3,750 million to be repaid in fifty equal payments until 2001.

In step with the huge economic and political decline was the continued break-up of the British Empire. By the mid-1950s only a relatively small number of colonies and protectorates were left of an empire which at its peak, in 1921, had covered a quarter of the surface of the globe, and included a quarter of the world’s population. It was known as ‘the empire on which the sun never set’.

Britain’s true place in the new world order was finally recognised in the Defence White Paper of 1957 (Cmnd. 230), which resulted from a fundamental defence review ordered in response to Britain’s rapidly declining economic situation. It was a defining moment for the armed forces of the United Kingdom marking the major shift in defence policy from large expensive conventional forces to smaller specialised forces more reliant on nuclear weapons and missiles. It was a watershed for the Royal Navy, being the turning point from the old traditional imperial navy towards the modern Royal Navy of the nuclear age.

NATO, NUCLEAR DEFENCE POLICY AND NAVAL STRATEGY

At the end of the fifties the government of the United Kingdom had four prime requirements for their naval and military planners to meet: defence of the realm, maintenance of defence commitments to NATO and the mainland of Europe, support of the colonies and overseas interests, and finally the protection of Britain’s worldwide trade. Whilst the first two requirements were met in conjunction with allies, the last two were covered solely by the armed forces of the UK, primarily the Royal Navy.

The Cold War By 1957 the ‘Third World War’, commonly known as the ‘Cold War’, had reached its eighth year. Predominantly a political and economic war of force deployment, manoeuvre and military technology, it was fought slowly and with much less intensity than its two immediate predecessors between 1914 and 1945. Nevertheless it was a perilous and dangerous confrontation, which seriously threatened the Western world with catastrophic destruction. It dominated all defence planning and expenditure, and nuclear weapons became the key components of the overall strategy.

HMS Vanguard

The Last of the Vanguard Class Battleships

The Vanguard was the very last of the battleships and had been replaced by the aircraft carrier as the capital ship of the fleet.

Launched: |

30 November 1944 |

Commissioned: |

9 August 1946 |

Displacement: |

46,000 tonnes |

Length: |

246.8m |

Propulsion: |

8 Admiralty 3-drum water-tube boilers, 4 Parsons single reduction steam turbines, 4 shafts |

Armament: |

8 BL 15 in guns in 4 twin mountings, |

Complement: |

1,500 |

No. in class: |

1 |

NATO As the political situation in Europe had steadily deteriorated and the threat from the Soviet Union had relentlessly increased, the Western allies explored their common defence needs. The Washington Treaty of 1949, built on the ‘Western Union’ Brussels Treaty of 1948, established NATO as the security alliance for the collective self-defence of the West. By the end of that year NATO had formulated its defence strategy (the Strategic Concept for the Defence of the North Atlantic Treaty Area-DC 6). DC 6 set out the basic principles of military co-operation and force co-ordination to provide collective defence in the event of an attack against any member state.

Military Strategy DC 6 was then refined and modified to respond to the growing might of the Soviet armed forces, mostly land and air forces. The NATO Military Committee set out the allied military planning framework in Plan MC 14, and the detailed military strategy (MC 14/1) was finally approved in December 1952.

The battleship Vanguard, flagship of the Reserve Fleet

(RNM)

The Royal Yacht Britannia leadingthe Fleet

(RNM)

Cruisers firing the traditional royal salute

(OJ) (CH) (RC)

Operation Steadfast

(NN)

Nuclear Strategy By the mid-fifties the West had become thoroughly alarmed by the massive build-up of Soviet and Warsaw Pact conventional forces and realised it would have little alternative but to depend on nuclear weapons in order to counter them. Fears of Warsaw Pact aggression and expansionism were further fuelled by Soviet intervention in Hungary and the Lebanon in 1956. Consequently in 1957 the Allies formulated the fundamental NATO strategy of ‘massive retaliation’, known as the ‘trip wire’ strategy, whereby the Alliance would use nuclear weapons to respond to any major Soviet attack. By concentrating on nuclear weapons the NATO Allies reduced the need to inflate their defence spending on expensive conventional forces in order to try and match the huge Soviet arms build-up. As regards naval strategy, the effect of a short war scenario was to reduce the reliance of NATO and Europe on resupply across the Atlantic and hence lessen the importance of ASW (anti-submarine-warfare) ships. The NATO strategy was however inherently dangerous, as the Soviets had already developed a hydrogen bomb, and in 1957 they successfully launched their first satellite, ‘Sputnik’ with an SS-6 Sapwood ICBM (intercontinental ballistic missile).

In 1958 Khrushchev demanded the withdrawal of all Western occupying forces from Berlin. Next, after the Cuban Revolution in 1959, he formed an alliance with Fidel Castro and was in a position to start deploying forces in close proximity to the United States. East-West tension was steadily rising by the turn of the decade.

UK Defence Review 1957 In the Suez Crisis of 1956 Britain and France had launched Operation Musketeer against Egypt in response to President Nasser’s nationalisation of the Suez Canal. The military operation had been a success but severe economic pressure from the USA had forced a cease-fire and an embarrassing climb-down by Britain and France. Anthony Eden, the British Prime Minister, resigned on 9 January 1957 and was replaced by Harold Macmillan. One of Macmillan’s early actions was to order Duncan Sandys, his new Defence Minister, to carry out a fundamental defence review. The main driver of the review was the need to achieve huge savings in the defence budget in order to ease the many pressures on the failing British economy. The result was the Defence White Paper (Cmnd. 230), published in April 1957 and entitled ‘Defence: Outline of Future Policy’. The White Paper set out huge cuts in equipment and reductions in uniformed manpower across all three armed services, with the Royal Navy taking the brunt.

The cruiser Bermuda at Malta, April 1958

(RNM)

Defence policy was reordered to concentrate on the immediate requirements of defence of the homeland and commitments to NATO, with reliance on nuclear deterrence and modern military technology. This shifted the emphasis from large conventional forces deployed worldwide to smaller more professional forces based much closer to home. National Service was to be phased out, regiments and air squadrons scrapped, and big reductions imposed on the Fleet and naval manpower. Most of the Reserve Fleet, of over 500 ships, was to be paid off and ultimately scrapped or sold. Over 100 shore establishments were to be closed.

Sandys was certainly no friend of the Royal Navy and was very much opposed to the concept of big expensive fleets. He saw the Royal Navy as ripe for yielding the greatest savings of the three armed forces and added to his Defence White Paper the infamous phrase ‘The role of naval forces in total war is uncertain’. The phrase was based on the perception that total war would rapidly resort to crippling nuclear strikes and thus all be over within a matter of a few weeks at the most, before naval forces would have any opportunity to participate. The White Paper did accept however that a nuclear exchange might not prove conclusive, in which case it would be vital to defend reinforcement convoys across the Atlantic against Soviet submarines.

Desmond Wettern stated that the defence review of 1957 ‘set a precedent that would be followed by successive governments in that it established the paramountcy of the economy over national security’.5

Defence Review 1958 (ASW) Following on from the 1957 White Paper, the 1958 Defence White Paper provided some clarity on the role of naval forces, stating that the priority in home waters would be ASW, as well as an effective contribution to the combined naval forces of the Western Alliance. This would be at the expense of balanced forces, and outside the NATO area the prime role would be the protection of shipping in peace and limited war. Even the two operational aircraft carriers, one deployed with the Mediterranean Fleet and one with the Home Fleet, would have ASW as their primary role.

THE FLEET

At the very end of 1956, when the last ships of Operation Musketeer had been withdrawn from the eastern Mediterranean, the Royal Navy still possessed a massive fleet, deployed in four operational fleets – Home, Mediterranean, Far East and East Indies – and supported by a huge Reserve Fleet. As well as five large naval bases in home waters the Royal Navy maintained overseas naval bases in Gibraltar, Malta, Simonstown, Trincomalee, Singapore and Hong Kong.

Operation Steadfast The Home Fleet, including the aircraft carriers Ark Royal, Albion and Ocean, was reviewed by HM the Queen on board the Royal Yacht Britannia in the Cromarty Firth on 27–9 May 1957. The impressive review was codenamed Operation Steadfast.

During that year, however, a large number of warships, many from the Reserve Fleet, were scrapped as a result of the Duncan Sandys’ defence review. Six aircraft carriers, including Ocean and Theseus, which had only just been converted to improvised helicopter carriers and deployed to Suez, were scrapped. The other aircraft carriers, Perseus, Glory, Illustrious and Unicorn, which had already been laid up in reserve, were also consigned to the scrapyard.

The aircraft carrier Victorious leaving New York on 3 August 1959

(RNM)

The great King George V class battleships, Anson, Duke of York, Howe and King George V, were all finally scrapped, leaving Vanguard, flagship of the Reserve Fleet, as the sole remaining battleship, the very last of the mighty super-Dreadnoughts. The cruisers Liverpool, Glasgow, Bellona, Cleopatra, Dido, Euryalus, and Cumberland also went to the breakers’ yards.

In addition six destroyers, forty frigates, twenty ocean minesweepers and a whole range of other ships, submarines and vessels were scrapped. Some warships were sold to other countries, including the aircraft carrier Warrior, which had been fitted with an angled flight deck and was sold to Argentina.

Strength of the Fleet Despite the large-scale reductions the strength of the fleet at the end of 1957 was still impressive. Officially the Navy had nearly 800 ships and vessels on its books in 1957. The backbone of the fleet, the capital ships, included seven aircraft carriers, the 43,000-ton fleet carriers Ark Royal and Eagle, the newly, and extensively, rebuilt Victorious (30,000 tons), the three Centaur class light fleet carriers, Albion, Bulwark and Centaur (22,000 tons), and Magnificent (15,700 tons), just returned from loan to the Royal Canadian Navy. In addition the fourth and final Centaur class light fleet carrier Hermes was nearing completion. The Bulwark was being converted for her modern commando carrier rol as a result of lessons learnt during the amphibious phase of Operation Musketeer, and work started on converting the light fleet aircraft carrier Triumph to a repair ship.

The cruiser squadrons comprised thirteen cruisers including Superb, Swiftsure and Belfast, three Southampton class, five Mauritius class and two Ceylon class. In addition work was being continued on the three Tiger class cruisers, Blake, Lion and Tiger, which had been laid down at the end of World War II but never completed. The rest of the fleet consisted of fifty-six destroyers, 107 frigates, forty-eight submarines, 200 minesweepers, fifty-two coastal and landing craft and eighty-eight support ships as well as large numbers of auxiliaries.

HMS Ark Royal

Audacious Class Aircraft Carrier

Ark Royal and Eagle were the two largest fixed-wing fleet carriers in the Royal Navy and served up until the mid-seventies (Eagle to 1972 and Ark Royal to 1978). They operated nuclear strike capable aircraft and were the backbone of the fleet. The fleet carriers were the capital ships of the Royal Navy until the 1970s.

Launched: |

3 May 1950 |

Commissioned: |

25 February 1955 |

Displacement: |

36,800 tonnes |

Length: |

245m |

Propulsion: |

8 Admiralty 3-drum boilers in 4 boiler rooms, 4 sets of Parsons geared turbines, 4 shafts |

Armament: |

As built 16 4.5 in gun (8 2) |

Complement: |

2,250 (2,640 with embarked air staff) |

No. in class: |

2: Ark Royal and Eagle |

Ark Royal’s Visit to New York In June 1957 the aircraft carrier Ark Royal, escorted by the destroyers Diamond and Duchess, crossed the Atlantic and visited New York before taking part in the US Navy’s International Naval Review and ‘Fleet Week’. The naval review, which marked the 350th anniversary of the founding of the first colony at Jamestown, included 103 warships from seventeen nations and, at the time, was the largest naval review in history. The US Navy was impressed with Ark Royal and her escorts, stating, ‘The Royal Navy was still an efficient, modern and powerful fighting force’.

Follow-Up Visit to New York by Victorious Two years later the aircraft carrier Victorious carried out a further successful visit to New York, where her ship’s company received a great welcome.

FIRST SEA LORDS

Admiral the Earl Mountbatten had been appointed First Sea Lord on 18 April 1955 and right from the start had tackled his important task with energy and relish reminiscent of the great Admiral Jackie Fisher. He was full of enthusiasm and ideas, which were essential at such a difficult time for the Royal Navy facing decline and huge cut-backs in ships and manpower. He foresaw the cuts of the Sandys defence review and had already formed a ‘Way Ahead Committee’ to identify economies and savings and to modernise and streamline the Royal Navy. The committee selected many shore establishments to be closed and also ships to be taken out of the Fleet.

Admiral Mountbatten Mountbatten was born on 25 June 1900 and joined the Royal Navy as a cadet in 1913. He served on board Admiral Beatty’s flagship Lion and also in the battleship Queen Elizabeth during World War I. Between the wars he served in the battleships Revenge and Centurion and the battlecruisers Renown and Repulse before being given command of the destroyers Daring and Wishart.

In World War II Mountbatten commanded the destroyer Kelly and the 5th Destroyer Flotilla until the Kelly was sunk off Crete in 1941. He was subsequently appointed Chief of Combined Operations and then Supreme Allied Commander South-East Asia as an admiral. After the war he became Viceroy and Governor-General of India, and he had to deal with Indian independence and the partition of the Indian Empire in 1947.

In 1948 Mountbatten commanded the 1st Cruiser Squadron, and two years later he was the Fourth Sea Lord. He then commanded the Mediterranean Fleet in 1952, being promoted full Admiral the following year. In April 1955 he was appointed First Sea Lord, in which post he was to remain for four years until Admiral Sir Charles Lambe relieved him in July 1959. Mountbatten was then appointed Chief of the Defence Staff and continued sadly to witness the decline of his great Service. He was passionate about everything that concerned the Royal Navy and proved to be one of the most important and influential of the post-war senior admirals. Many of his ideas and innovations had significant and lasting effects on the future of the Royal Navy.

Admiral Lambe Charles Lambe was born in December 1900 and joined the Royal Navy as a cadet in 1914, going to sea in the battleship Empress of India at the end of World War I. At the outbreak of World War II he was in command of the cruiser Dunedin, but he spent most of the war in the Naval Plans Division at the Admiralty. In 1944 he commanded the aircraft carrier Illustrious in the Pacific. He then returned to the Admiralty in charge of flying training before commanding the 3rd Aircraft Carrier Squadron. He was promoted Vice Admiral in 1950 and was Flag Officer Air (Home) before being appointed Commander in Chief Far East Station. He served as Second Sea Lord for three years from 1954 and then became Commander in Chief Mediterranean Fleet before relieving Lord Mountbatten as First Sea Lord in 1959.

The Home Fleet at sea for the spring cruise

(RNM)

Admiral Lambe suffered a heart attack six months after taking over and had to be relieved on 10 May 1960. He died three months later aged fifty-nine.

OPERATIONS AND DEPLOYMENTS, 1957–1959

In 1957 the Royal Navy was deployed on a range of operational peace-keeping tasks around the world. Ships and squadrons were maintained on station as guardships in key strategic bases on the main shipping routes and SLOCs (sea lines of communication). At home, in early 1958, the Home Fleet sailed for its last deployment as a fleet. The aircraft carrier Bulwark, escortedby cruisers and destroyers, led the Home Fleet for its spring cruise, which was to be its last regular one. In the future ships of the Home Fleet would be deployed in task groups for specific operations, deployments, tasks or exercises.

The Persian Gulf In the Persian Gulf a squadron of four Loch class frigates (Loch Fada, Loch Fyne, Loch Killisport and Loch Ruthven) was stationed at Jufair, the naval station in Bahrain. The frigates conducted extensive patrols, searching dhows, intercepting arms and slave trafficking and preventing smuggling, piracy and rebel infiltration. They also had to carry out policing actions ashore, protecting British nationals and property and quelling local riots and disturbances.

The East Indies Station was disbanded in 1958 and replaced by the Arabian Seas and Persian Gulf Station, covering the Persian Gulf, Straits of Hormuz, Arabian Sea and north-east Indian Ocean.

The Far East The Malayan Emergencywas continuing, and Royal Navy ships and naval aircraft were employed in support of British troops, carrying out coastal patrols, aerial reconnaissance and naval gunfire support, as well as resupply and reinforcement tasks. In one incident, in early December 1957, the cruiser Newcastle carried out an intensive shore bombardment of terrorist positions with her main armament of 6-inch guns, having sailed up the Kota Tinggi River in Malaya. Further south, Indonesian gunboats were interfering with British merchant vessels and had to be deterred by British frigate patrols. Piracy continued to be a problem in the area and naval ships were needed to conduct regular deterrent patrols.

Hong Kong In Hong Kong the six inshore minesweepers of the 120th Minesweeping Squadron took over guardship duties from the hard-worked HDML (harbour defence motor launch) squadrons.

The Crown Colony of Cyprus By the middle of the 1950s Cyprus had become an important UK strategic base, dominating the eastern Mediterranean. Cyprus lacked a deep-water port for the Royal Navy, though ships could use the port at Famagusta, but Nicosia provided a vital airfield to counter Soviet encroachment in the Middle East. It had also proved crucial for the mounting of Operation Musketeer during the Suez crisis in 1956.

Sadly the local Greek and Turkish Cypriots were at each other’s throats, each wanting independence from the UK and alignment with their mother country. In 1955 the rebel EOKA (Ethniki Organosis Kuprion Agoniston) guerrillas of General Grivas started their terrorist campaign of attacks, bombings and shootings. It became necessary for more and more UK troops, including Royal Marines, to be deployed to try and maintain the peace. For two years 40 and 45 Commandos were continually engaged on a rotational basis from Malta in anti-terrorist operations in Cyprus. A lot of the offensive operations were conducted in the inhospitable Troodos Mountains, used as hideouts by various local terrorist groups.

45 Commando was deployed to Kyrenia, one of the main strongholds of the EOKA guerrillas, and within three months established complete dominance over the area, severely limiting EOKA operations throughout the rest of Cyprus.

Throughout the period ships of the Mediterranean Fleet were required to conduct coastal patrols on a regular basis in order to prevent the smuggling of arms and ammunition as well as supporting operations being conducted by security forces ashore.

Jordan In early 1957 Britain was pulling all her forces out of Jordan, as decided by mutual agreement in March, following the expiry of the original Anglo-Jordanian Treaty. Considerable unrest remained in Jordan, which threatened to break out in violence against British nationals. On 15 April the frigate Opossum, which was lying at Port Sudan, was brought to immediate notice to proceed to Aqaba and evacuate British personnel, but on 25 April King Hussein of Jordan declared martial law. As martial law restored security, the situation eased and the frigate was stood down a week later. On 6 July the ss Devonshire, escorted by the destroyer Modeste, evacuated the last British troops from Jordan.

Cyprus Emergency The situation in Cyprus steadily worsened, and in April 1958 it was decided to reinforce the security forces with 45 Commando, Royal Marines from Malta. The cruiser Bermuda embarked 45 Commando and helicopters from 728 NAS (Naval Air Squadron) and sailed from Malta on 16 April, bound for Cyprus.

Two days later Bermuda arrived off Akrotiri and landed 45 Commando and the naval helicopters ashore in Cyprus. The following month, on 23 May, a state of emergency was declared.

Aden Trouble was also being experienced in Aden and reinforcements were needed to deal with the internal unrest. On 18 April 1958 the cruiser Gambia, escorted by the frigate Loch Fyne, arrived in the Port of Aden with the first echelon of British troops.

Crisis in the Middle East

Formation of the Arab Federation Following the formation of the United Arab Republic by President Nasser of Egypt in 1958, much of the Middle East had become very unstable with the rapid rise of Arab nationalism. Jordan and Iraq were forming the Arab Federation, and ‘Nasser’s’ call was being spread to other Arab countries. There were problems from increased agitation in Lebanon, Libya, Jordan, Aden and Cyprus.

Lebanon On 13 May 1958 Lebanon requested military assistance following clashes between Muslims and Christians. On 14 May the Amphibious Warfare Squadron sailed from Malta and headed east for the coast of Lebanon. The aircraft carrier Ark Royal, conducting exercise Medflexfort, was put on alert to evacuate British subjects from Lebanon. On 22 May Ark Royal completed the exercise and headed east but was ordered to remain on stand by off the coast of Cyprus. Whilst off Cyprus Ark Royal, with her air squadrons, supported British troops engaged in security operations ashore, where EOKA was continuing to wage a violent terrorist campaign. The UN Assembly reviewed the whole situation, and plans for joint British and US operations, including landings by US Marines were drawn up.

The cruiser Gambia en route to the Middle East

(NN)

Cyprus On 10 June the aircraft carrier Eagle arrived off the coast of Cyprus. She sailed into the Bay of Akrotiri and came to anchor a short distance from Ark Royal. As soon as she had anchored, the helicopters of 820 NAS together with all their equipment and stores from Ark Royal were transferred to Eagle.

The next day Ark Royal, having handed over patrol duties to Eagle, weighed anchor and headed west en route for Malta, Gibraltar and ultimately Devonport for refit. Eagle maintained operational support to the Royal Marines and British troops ashore engaged in anti-terrorist patrols and internal security operations. At the same time Eagle was on standby to deploy to the Lebanon.

Jordan The problems in the Middle East were made worse by a revolution in Iraq and the murder of King Feisal on 14 July 1958. Both President Chamoun of Lebanon and King Hussein of Jordan appealed to the West for military assistance to maintain order. It was agreed internationally that the US 6th Fleet would respond over Lebanon’s request, whilst Britain would assist over Jordan and also a subsequent request from Libya.

On 16 July Eagle, escorted by the cruiser Sheffield, sailed from Cyprus, heading south-east at speed to join the rest of the Mediterranean Fleet, which was deployed off the coast of Israel. The carrier Albion sailed from Rosyth and embarked 42 Commando Royal Marines at Portsmouth before heading south and making a fast passage to Malta.

Meanwhile the cruiser Bermuda and her escorts were detached to Malta to transport units of 45 Commando Royal Marines to the Libyan ports of Tobruk and Benghazi. 45 Commando held the Libyan ports until relieved by the 1st Battalion of the Royal Sussex Regiment, transported from Gibraltar by the old heavy cruiser Cumberland. On being relieved, 45 Commando was transported to Cyprus on board the cruiser Bermuda to take over from 40 Commando. Sheffield was detached to take 40 Commando back to Malta. In parallel the US 6th Fleet conducted operations in Lebanon.

Operation Fortitude, July 1958 After a swift passage from Cyprus Eagle arrived off the coast of Israel, joining the destroyers Dunkirk and Cavendish and the frigates Salisbury and Torquay for Operation Fortitude. The operation was for the reinforcement of Jordan. Eagle’s aircraft provided support and cover for the major airlift of British troops to the Jordanian capital, Amman. On 17 July two battalions of the 16th Independent Parachute Brigade were airlifted to the city. During the operation Eagle’s air group flew 500 sorties and 136 combat missions. Operation Fortitude was successfully completed on 23 July with the loss of only one Sea Venom aircraft, a considerable achievement.

Ships from the East Indies Fleet, including the carrier Bulwark, escorted by the frigate Ulysses, were despatched west across the Indian Ocean to assist with the crisis. The ships called into Mombasa, where, on 7 August, Cameron Highlanders were embarked on board Bulwark to reinforce the troops deployed in Jordan. She then transported the troops up the Red Sea, escorted by the frigates Ulysses and Bigbury Bay, and landed the Cameron Highlanders at Aqaba in the Gulf of Sinai. Meanwhile, in the Persian Gulf, a frigate was stationed up the Shatt al-Arab waterway in Iraq.

With the situation in Jordan stabilised Eagle returned to Cyprus and resumed support operations off the coast for a month. She was then relieved by Albion, which had transported 42 Commando from the UK. Only then could Eagle sail for Malta and some well-deserved rest and recreation for her hard-worked ship’s company and air group.

The following month Bulwark returned through the Gulf of Aden and was deployed further east off the coast of Muscat, where she operated her aircraft in a series of strikes against rebels in the Jebel Akhdar Mountains from 12 to 21 September.

By late October the crisis in Jordan had eased sufficiently for British troops to be withdrawn. On 2 November the troops embarked on board the cruiser Ceylon and the frigates Chichester and Loch Fyne. King Hussein of Jordan flew down from Amman to Aqaba to review and thank the departing British troops. The swift and positive action taken by British and US forces in the eastern Mediterranean had undoubtedly managed to restore order in a volatile region at a particularly dangerous time.

Cyprus On 3 October Eagle left Malta and returned to Cyprus, where, on arrival, she relieved Bulwark. Having handed over responsibility, Bulwark departed from Cyprus and sailed west across the Mediterranean on passage to the UK, where she was due to commence important dockyard work to be converted to a commando carrier.

On 18 October the Ton class minesweeper Burnaston intercepted the Turkish vessel mv Denil and, having boarded her, discovered she was carrying a considerable quantity of arms and ammunition to Cyprus. After the crew were evacuated and arrested the mv Denil and her cargo of arms were scuttled.

A short while later, the aircraft carrier Victorious joined Eagle, and the two carriers conducted a series of joint flying exercises off the coast of Cyprus. On their completion Victorious took over responsibility for support of counterterrorist operations ashore in Cyprus, enabling Eagle to sail for the UK to arrive in Devonport in time for Christmas.

The situation ashore eased in late 1959 with the Zurich Agreement, which renounced union with Greece and partitioned the island into separate Greek and Turkish enclaves. Naval patrols were reduced as the situation improved in the period running up to independence.

The Persian Gulf The Royal Marines were involved in minor operations conducted in the Persian Gulf in 1957. In the summer the frigate Loch Alvie was en route to Abadan, with Royal Marines embarked, when she received an immediate signal to divert to the Shatt al-Arab waterway at best speed. A mutiny had broken out on board a British tanker loaded with aviation fuel. On arrival off the coast Loch Alvie ran up her battle ensign and increased speed to full ahead. The Royal Marines boarded the tanker, and after a brief action the mutiny was quickly quashed.6

Two months later the Royal Marines were in action again further south. A revolt had broken out against the Sultan of Oman, who appealed to Britain for help. The Loch class frigate squadron on station in Bahrain quickly sailed and headed south at full speed. Ashore in Oman the Royal Marines were soon in action. They were supported by the frigates, which provided further supplies of ammunition and equipment and acted as the communications link with area command HQ at Bahrain. The frigates also blockaded the coast to prevent any arms and reinforcements from reaching the rebels on shore. The Royal Marines quickly and efficiently suppressed the revolt.

North Borneo At the beginning of March 1958 British merchant vessels were being attacked by Indonesian gunboats off Tawau and appealed for help. On 8 March the frigate Modeste was despatched to the area and immediately deterred the Indonesian gunboats from any further attempts to interfere with British ships in the area. On 12 March Modeste patrolled off the coast of Mendao, North Celebes, for several more days and then departed from the area when order had been restored.

The First Cod War, 1 September 1958 – 11 March 1961

Extension of Territorial Limit On 1 September 1958 Iceland unilaterally extended the limits of her territorial waters from three miles to twelve miles to protect her fishing grounds from over-fishing. This had been announced earlier in May, and despite the declaration being condemned in The Hague on 14 July the Icelandic government was determined to go ahead to conserve ‘her’ fish stocks, which were so vital to her economy.

Operation Whippet The Royal Navy was prepared, and the Captain of the Fishery Protection Squadron (‘Captain Fish’) had issued orders for Operation Whippet in June. The frigates Eastbourne, Russell and Palliser and the ocean minesweeper Hound were on patrol off Iceland on 1 September when the Icelandic gunboats Aegir, Albert, Odinn, Thor and Maria Julia appeared and started harassing British trawlers, threatening and trying to arrest them. There then followed a series of confrontations, hostile manoeuvrings at close quarters and opposed boardings. In most incidents Royal Navy frigates managed to defend the trawlers. In the first skirmishes Eastbourne managed to free several trawlers and capture two Icelandic boarding parties. The Aegir rammed several trawlers and also attempted to ram Russell, which was manoeuvring to protect the trawlers. Russell threatened to open fire and sink the Aegir before she finally backed off.

The destroyer Trafalgar in the Cod War, August 1959

(RNM)

On 5 September the destroyer Lagos was sent to the area as the gunboats continued their attempts to arrest British trawlers, and eight days later the destroyer Hogue arrived. On 18 September Aegir attempted to arrest the trawler Valafell, which then in response tried to ram the gunboat.

On 20 September the powerful Daring class destroyers Diana and Decoy arrived in the disputed area. Nine days later the gunboat Maria Julia fired warning shots when attempting to arrest the trawler Kingston Emerald. Both Odinn and Thor then fired warning shots when trying to arrest other trawlers.

Hostile engagements between gunboats, trawlers and defending destroyers and frigates continued throughout the rest of the year, by which time twenty-two Royal Navy warships, supported by five RFA (Royal Fleet Auxiliary) tankers, had been involved. In several engagements the Icelandic gunboats had opened fire with solid shot. There had been some thirty unsuccessful attempts to arrest trawlers. Although incidents had eased over the winter months, encounters continued in the spring of the following year as the trawlers returned to the fishing grounds and Icelandic gunboats maintained their persistent attempts to arrest trawlers in the disputed waters. As incidents continued the Royal Navy sent more warships to patrol closer into the disputed areas. In encounters in April both Odinn and Thor fired warning shots at trawlers. Then in May Thor fired on the trawler Arctic Viking, first with warning shots and then directly at her masts to knock out her radio and prevent her calling for help. The destroyer Contest arrived on the scene and opened fire with star shell, which was sufficient to prevent Thor from continuing and persuade her to break off the action. A little while later the destroyer Chaplet was involved in a collision with Odinn, though fortunately the damage was not too serious.7 In July Maria Julia, Thor and Aegir all fired shots in separate incidents. Throughout the rest of the year sporadic incidents continued, with the warships on patrol managing to thwart attempts by the Icelandic gunboats to arrest British trawlers.

The Cod War: a trawler astern of the frigate Eastbourne

(RNM)

Many of the incidents were very confused, with differing accounts resulting in claim and counter-claim. Different reports from commanding officers made it difficult for accurate assessments to be made of many of the dangerous incidents. The fact that no lives had been lost was down to the great ship-handling skills and seamanship on both sides.

All political attempts to resolve the dispute failed, and the ‘Cod War’, as it had become named, dragged on for a further fifteen months, involving thirty-seven warships and six Royal Fleet Auxiliaries. It was not until midnight on 14 May 1960 that British trawlers were finally withdrawn from Iceland’s extended territorial waters and Operation Whippet was suspended. The Royal Navy had protected the British fishing fleet for eighteen months, enabling the trawler men to fish almost normally, despite continuous harassment and some seventy attempted arrests as well as a great many hostile encounters.

Trouble in the Indian Ocean, August 1959 On 6 August 1959 trouble broke out on the important strategic island of Gan in the Maldives. Gan was a key island in the Indian Ocean that acted as a staging post to the Far East, which made it essential to restore order and protect the British military and airfield installations. The destroyer Cavalier was immediately despatched to the island and a company of soldiers was flown in from Singapore.

The presence of a powerful British warship in the harbour and a company of soldiers was sufficient to protect the vital RAF installations. Order was eventually restored and Cavalier remained at Gan until the end of the month. The destroyer Caprice arrived off Gan on 29 August and took over from Cavalier.

OTHER DUTIES

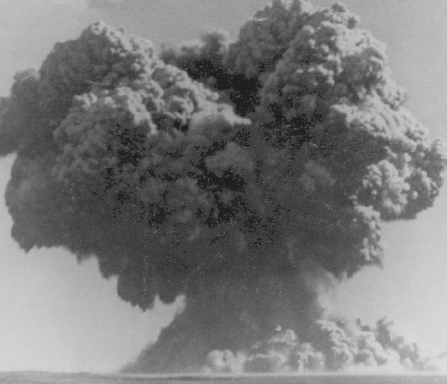

Operation Grapple Between March and June 1957 the Royal Navy formed a special task group known as the Grapple Squadron, to assist in the thermo-nuclear weapon tests being conducted on Malden Island under the codename Operation Grapple. In early January 1957 the light fleet carrier Warrior sailed with the armament stores ship RFA Fort Rosalie, bound for the Pacific Ocean.

The Commodore of the Grapple Squadron was embarked in Warrior, and the rest of the squadron comprised two landing ships (tanks), nine smaller landing craft (tanks), a survey vessel, a salvage vessel, a despatch vessel and two Royal New Zealand Navy frigates. An additional landing ship (tanks) and various support vessels remained at Christmas Island some 400 nautical miles north-north-east of Malden Island. The ships of the squadron performed a range of tasks associated with the tests. After the final test on 19 June Warrior and most of the Grapple Squadron returned to the UK.

‘Showing the Flag’ In addition to operations, deployments and security patrols, the Royal Navy was engaged in a great many other duties, not the least of which was the traditional ‘showing the flag. Goodwill visits were an important element of British foreign policy and were considered to be ‘one of the best ways of maintaining British prestige and influence abroad’. In 1959 Royal Navy ships and submarines paid over 300 foreign visits. Ships were often ‘dressed overall, with signal flags, and open to visitors. Ships of the Fleet also visited home ports regularly and conducted ‘Meet the Navy’ programmes.

Naval Exercises As well as ‘showing the flag’ the Royal Navy was also heavily involved in joint naval exercises all round the world. In 1957 a massive NATO exercise, Operation Strikeback, was conducted in the North Sea, involving the carriers Ark Royal, Bulwark, and the US Navy carriers Forrestal and Essex and the missile cruiser USS Canberra. In 1959 the Royal Navy took part in seven major NATO exercises in the Atlantic, Channel and Mediterranean, Commonwealth naval exercises in the Indian Ocean and South Atlantic, a SEATO (South East Asia Treaty Organisation) exercise in the South China Sea and a CENTO (Central Treaty Organisation) naval exercise in the northern Gulf.

Rescue and Relief Operations

Fishery Protection On 20 April 1957 the ocean minesweeper Bramble was ordered into Norwegian waters, where there was a dispute over Russian interference with fishing on the Viking Bank. Russian vessels had damaged British fishing gear. By swift action Bramble was able to resolve the dispute without provoking an international incident.

The following year on 17 April there was further Russian interference with British fishing vessels some 250 miles north-east of Aberdeen. The coastal minesweeper Belton was sent to the area and the dispute was quickly resolved. As a result of intervention by the Royal Navy, the Russian trawlers agreed to pay compensation for damage to the nets of British trawlers.

Earthquake Relief Work In the Mediterranean the Daring class destroyer Dainty was sent to Fethiye following an earthquake in Turkey on 25 April 1957. On arrival the destroyer was able to provide important emergency relief aid in the wake of the disaster.

Sea Rescue On 20 August 1957 the tanker ss World Splendour caught fire after a major explosion on board. She was off Gibraltar, and the Daring class destroyer Delight was immediately sailed to attempt a rescue. The destroyer managed to rescue forty survivors and assist the disabled tanker, which was taken in tow. Sadly the tanker sank the next day but the Admiralty tug Confident arrived from Gibraltar and rescued the remaining survivors.

The light fleet carrier Warrior

(RNM)

Dubai In the Persian Gulf the frigate Loch Ruthven sailed for Dubai on 24 November 1957 with emergency medical and food supplies following a severe storm, which had devastated the area. On arrival the frigate was able to carry out emergency relief operations.

West Indies Violence broke out on the island of Nassau in the Bahamas following a strike on 18 January 1958. The frigate Ulster was summoned to the island at full speed and arrived shortly afterwards. Immediately a naval party was landed from the frigate and took over the power station to safeguard emergency services during the disturbances. The presence of the British frigate helped to calm the situation and order was soon restored.

Mediterranean Whilst the aircraft carrier Eagle was operating in the western Mediterranean she was off the port of Hyeres on 8 March 1958 when she received an urgent order to sail due south at full speed. Two French naval aircraft had collided in mid-air and crashed into the sea sixty miles north of Cape Bon, Tunisia, and both pilots were missing. Eagle arrived in the area several hours later but after an intensive search only one pilot was recovered.8

Indian Ocean On 1 April 1958 the Norwegian tanker SS Skaubrun was on fire in the Indian Ocean. The frigate Loch Fada hastened to assist the tanker, which was abandoned as the fires raged. Merchant ships in the vicinity had taken off most of the survivors but the frigate was able to assist in extinguishing the fire and then took the tanker in tow.

West Indies A strike in Grenada on 21 August 1958 caused severe problems, and the frigate Troubridge was sent at speed to the island. An emergency relief party was quickly landed from the frigate. Once ashore the relief party managed to restore power and run the power station, maintaining emergency supplies during the strike. Five days later the strike was over and Troubridge was able to hand over to the local authorities, sailing from the island on 26 August.

Persian Gulf On 13 September 1958 the French tanker Fernand Gilbert collided with a 21,000-ton Liberian-registered tanker, the Melika. Both tankers were on fire and the aircraft carrier Bulwark, escorted by the frigate, Loch Killisport, was ordered to the area. The frigates Puma and St Brides Bay were also in the vicinity and quickly arrived on the scene. Survivors were rescued by helicopter from Bulwark, and helicopters were also used to convey firefighting parties to the blazing French ship. The fires were brought under control and Bulwark, assisted by Puma, towed the Melika to Muscat, arriving on 20 September, whilst Loch Killisport towed the Fernand Gilbert to Karachi.

A Royal Navy cruiser open to visitors on a port visit

(TT)

Libya Severe floods struck Libya at the beginning of October 1959, and 40 Commando Royal Marines was quickly sent to provide emergency relief work. The Royal Marines provided much valuable assistance, helping to restore essential services and distribute emergency food and medical supplies.

Philippines On 23 November 1959 the SS Szefeng was in distress in the Sulu Sea, and the destroyer Solebay was immediately diverted to the area to render assistance. The destroyer managed to secure a tow and then towed the SS Szefeng to Pujada Bay in south-east Mindanao.

SHIPS, SUBMARINES, WEAPONS AND AIRCRAFT

The late 1950s saw the Royal Navy taking major steps forward into the era of nuclear technology and missile warfare. Research and development of naval gunnery was discontinued whilst missile and ASW technology were allocated high priority. Development of ‘afloat support (fleet tankers and replenishment ships) was also undertaken to reduce the Fleet’s reliance on shore base support, which could be vulnerable in the event of nuclear war.

The Royal Navy still possessed a large fleet of aging conventional warships, the majority of World War II design or construction, though large numbers were assigned to the Reserve Fleet (over 400) and a great many were laid up. Much of the design work for new construction was still based on revised and improved conventional ship classes.

Nuclear Weapons Between 1956 and 1958 Britain conducted a series of hydrogen bomb tests at Malden Island and Christmas Island in order to become a thermo-nuclear power. Britain’s first megaton H-bomb was detonated on 8 November 1957. These tests, carried out under the codename Operation Grapple, mentioned above, were successful. They impressed the Americans, and in 1958 the US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement was signed, bringing in an era of US-UK nuclear co-operation and development. The agreement was to prove crucial to the development of Britain’s submarine-based strategic nuclear deterrent in the future.

Eagle on trials after modernisation

(RNM)

As regards strategic weapons, Britain’s deterrent force was, from 1956, the responsibility of the RAF operating the ‘Quick Reaction Alert’ V-Bomber squadrons of Valiant, Vulcan and Victor manned bombers, armed with ‘Blue Danube’ free-fall bombs.

British hydrogen bomb test

(RNM)

First RN Nuclear Weapons The Royal Navy took delivery of its first nuclear weapons in 1959. These were free-fall tactical nuclear bombs, designated Red Beard and carried in the Supermarine Scimitar, and later the Buccaneer, aircraft of the Fleet Air Arm operating from aircraft carriers. The initial main tactical role for these weapons was ship strike in the north-east Atlantic, though clearance for aircraft to take off with the weapons armed for this role was not finally approved until August 1960.

Aircraft Carriers and Naval Aircraft Although the aircraft carriers of the Royal Navy were of World War II design and construction, naval jet aircraft had become progressively heavier and faster, making deck operations much more difficult and dangerous. In 1958 two new fast and powerful naval strike fighters, the Supermarine Scimitar and the de Havilland Sea Venom, joined the Fleet Air Arm. Fortunately many advances had been pioneered by Britain to improve the operating of modern heavy jet aircraft from aircraft carriers. These included the angled flight deck, steam catapults, improved radar and data control and deck landing sights. The angled flight deck and steam catapult were great innovations, allowing much of the flight deck to be used during both launching and recovery operations. These innovations were quickly taken up by the US Navy, which found them a huge help in operating modern heavy US naval aircraft.

Aircraft Carrier Refits Ark Royal was refitted in 1959, and at the end of the year Eagle commenced a major four-year modernisation and update refit in Devonport. The £30m refit provided her with an 8½° angled flight deck, steam catapults and the large state-of-the-art 984 radar.

Commando Carriers Operation Musketeer, during the Suez crisis, had proved the effectiveness of launching airborne assault waves using helicopters embarked in carriers, and the concept of the commando carrier had then been accepted. The Naval Staff decided to convert the light fleet carriers Albion and Bulwark to the commando role. In December 1959 Bulwark was commissioned as the Royal Navy’s first commando carrier with 848 Naval Air Squadron.

Nuclear Submarines The Royal Navy commissioned two experimental HTP (high test hydrogen peroxide) submarines, Excalibur in 1956 and Explorer in 1958. They were based on a German HTP U-boat, U 1407, which had been scuttled at the end of the war. U 1407 was salvaged and then commissioned into the Royal Navy as Meteorite for trials and evaluation.

Bulwark as a commando carrier

(NN)

Trials of the commando helicopter carrier concept

(RNM)

Excalibur and Explorer were both assigned to the 3rd Submarine Squadron but spent little time at sea. The fuel was highly unstable and very dangerous. Explorer was known as ‘Exploder as a result of several serious accidents, and Excalibur was known as ‘Excruciator’. Although they achieved an impressive twenty-five knots submerged, the project was not a success and it was clear from the US Navy nuclear submarine programme that nuclear propulsion was the only way forward. Thanks to the relentless drive of Admiral Hyman Rickover the US Navy had made great progress with nuclear propulsion and submarine design, culminating in the first nuclear submarine, the 4,040-ton USS Nautilus (SSN 571), commissioned in September 1954. The USSR was not far behind and had built its first ballistic missile nuclear submarine (SSBN) by the following year.

When the USS Nautilus made an official visit to Portsmouth in October 1957, the Defence Minister, Sandys, and Lord Mountbatten went aboard and were greatly impressed by all they saw. Sandys said, ‘The nuclear submarine represents, in the sphere of naval warfare a revolutionary advance as great as the change from sail to steam’.

The British nuclear submarine programme, however, made very slow progress. The Dreadnought Project did not get properly underway until 1957, and then there were problems with her UK-designed gas coolant propulsion system. It was not until March 1958, when Admiral Rickover visited the UK, that a deal was made to install a US Skipjack propulsion unit (a water-cooled Westinghouse S5W power plant) into the UK’s first nuclear submarine. The deal was entirely due to the close personal relationship between Mountbatten and Rickover and was part of the emerging special relationship between the UK and the USA.

The Mutual Defence Agreement Behind the veil of national security the Macmillan government was embarking on wide-reaching agreements with the United States of America, which fundamentally altered the structure and modus operandi of the Royal Navy Submarine Service for decades to come. The major agreement came on 4 August 1958 with a document entitled ‘Cooperation on the Uses of Atomic Energy for Mutual Defence Purposes’. This laid the foundations for the exchange between the USA and UK of controlled nuclear information, sensitive nuclear technology and materials. For the submarine service this meant the transfer of submarine nuclear propulsion plant and other materials to enable the Royal Navy to play a major role in the Cold War.

In August 1958 the USS Nautilus completed her famous voyage under the polar ice cap (Operation Sunshine),9 arriving at Portland on 12 August. When she arrived in the Channel the Royal Navy was given operational control of her for a week’s operational evaluation in exercise Rum Tub. The exercises were conducted in the South-Western Approaches (SWAPS), with the carrier Bulwark, ASW escorts, aircraft and submarines. Post-operational analysis by the naval staff confirmed the enormous tactical advantages of the SSN (nuclear fleet submarine), which were due to her high underwater speed.

Guided Missiles Although the guided missile trials ship, Girdle Ness, was coming to the end of her time she had achieved her purpose, and two surface-to-air guided missiles (SAMs) were shortly to join the Fleet; the short-range, wire-guided Seacat missile and the medium-range, beam-riding Seaslug missile. The Seaslug system was also to have a limited surface-to-surface (SSM) capability. Both missile systems were to serve in the Falklands War some twenty-five years later. The Seacat was to be credited with destroying a number of Argentinean aircraft. Girdle Ness was paid off as a guided missile trials ship in December 1961 and was reclassified as an accommodation ship in the following year.

Guided Missile Destroyers The Royal Navy’s first class of guided missile destroyers (GMDs), the County class, had been ordered, and the first of class, Devonshire, was laid down in March 1959. These 6,000-ton ships were, to all intents and purposes, light cruisers but were officially categorised as DLGs (destroyer leader guided). They were designed to provide area defence for aircraft carriers and high-value assets and were to be equipped with both Seaslug and Seacat missile systems.

Kent, one of the first batch of guided missile destroyers

(RNM)

Gas Turbines The DLGs were to be constructed with a new propulsion system, a combination of steam and gas turbines known as COSAG (combined steam and gas). The Royal Navy had been experimenting since the end of World War II with the use of gas turbines for ship propulsion. Trials had started with a converted steam gunboat (Grey Goose) and gas turbines had then been fitted in fast torpedo boats. A developed marine gas turbine (G6) was installed in a frigate (Ashanti, the first of the Tribal class general-purpose frigates), and was next fitted to the DLGs.

The first batch of DLGs was under construction in 1958, with the ships (Devonshire, Hampshire, Kent and London) scheduled to join the Fleet in the early 1960s.

Devonshire, the first Royal Navy guided missile destroyer

(CC)

The Wasp Helicopter and ASW As anti-submarine tactics evolved helicopters were considered as a possible ASW weapon platform. In 1957 trials were conducted with the frigate Grenville to investigate the concept of operating light helicopters from small ships. This led to the development of the small anti-submarine warfare Wasp helicopter, armed with depth charges and homing torpedoes, being deployed to sea in frigates. The quick-reaction Wasp helicopter could be rapidly vectored (directed) out to a distant target and thus greatly extended the operational tactical range of ASW frigates.

Propulsion and Ship Design In 1958 the great majority of the Royal Navy’s major warships were steam-driven, as they had been throughout World War II. Most had main boilers of standard, war-proven and reliable Admiralty three-drum design, burning viscous furnace fuel oil (FFO) to supply main steam turbines designed for greatest fuel efficiency at high speed. The smaller war-construction escorts were propelled by reciprocating steam engines. In all steam ships, however, the need for adequate supplies of high quality ‘feed’ water for the boilers, as well as large quantities of fresh water for the crews from inefficient seawater distillation plants, was a constant problem. Electricity supply was direct current from steam-driven turbo-generators.

The destroyer Daring

(RNM)

Modern Design By the late 1950s, fast modern Daring class destroyers had begun to join the Fleet. These were designed and built with lighter, more compact boilers working at higher pressure and greater efficiency with superheated temperatures. The Darings also confirmed the use of allwelded construction for warship hulls. A start was also made in using alternating current electrical supplies, with significant advantages in terms of weight, space and ease of transmission.

Anti-Submarine Frigates The Daring class destroyers were overlapped by modern frigate designs; the Whitby class (Type 12), the Rothesay class (Type 12M) and the smaller, less capable single-shaft Blackwood class (Type 14). All were designed for fast anti-submarine warfare in the North Atlantic, with innovative hull shape and relatively light and compact propulsion machinery. They had all welded hulls and better sea-keeping abilities as well as enclosed bridges. Steam was still generated from FFO, but at higher pressure and temperature to turbines designed for greatest fuel efficiency at cruising speeds, a lesson learnt from World War II operations with the US Navy over large ocean distances in the Pacific.

The Type 14 Blackwood class frigate Russell

(TT)

Leander Class Frigates Through the 1960s, these post-war designs evolved into the three variants (batches) of the Leander class of general-purpose frigate, of similar hull form and main machinery but specially designed to operate the small anti-submarine Wasp helicopter. The earlier Rothesay class was later modified so as to operate the Wasp helicopter as well. The later, Batch 3, broad-beam Leander frigates remained in service right up until the early 1990s.

The second rate anti-aircraft frigate Morecambe Bay

(RNM)

Anti-Aircraft Frigates Over a similar period two classes of specialist frigate, the Salisbury class (Type 61) for aircraft direction, and the Leopard class (Type 41) for anti-aircraft roles, were introduced with a hull form similar to that of the Whitby class but propelled by four Admiralty-design diesels on each of two shafts. These provided much greater fuel endurance and introduced remote engine controls, but had limited top speed and required controllable pitch propellers for astern manoeuvring. The new machinery design introduced diesel oil (‘Dieso’) as a major warship propulsion fuel in the surface fleet.

Bay and Loch class frigates Whilst the new frigate classes were joining the fleet, some older frigates were retained in commission as second-rate frigates to cover general duties serving all over the world. The three prime classes of World War II frigates retained in service were the Bay class (antiaircraft escorts), the Loch class (anti-submarine escorts) and the smaller Castle class (anti-submarine). The Loch class provided valuable service in the Persian Gulf and Arabian Sea.

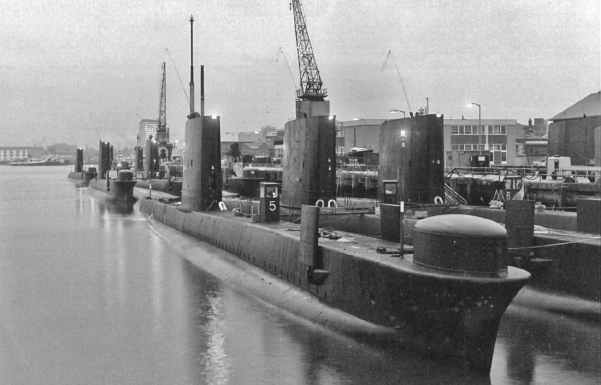

Conventional Submarines Between 1959 and 1964, thirteen all diesel-electric Oberon class submarines were built. The first of class, Oberon, was launched at Chatham on 18 July 1959. The submarines were capable of high underwater speeds of up to seventeen knots and carried the latest technology in detection equipment and weapon systems. The most significant of the improvements came from the designed soundproofing of all internal machinery, making them the quietest diesel submarines of their time. They were designed to conduct continuous submerged patrols conducting ‘Indicators and Warning’ missions vital to countering the emerging Soviet Cold War threat. As a class of submarine they were workhorses, operating primarily in arctic Europe, but saw service all over the world. In 1982 they saw service in the Falklands, and in 1991 they played a significant part in Operation Desert Storm. They also made a valuable contribution as a modern submarine to train the future commanding officers of the nuclear submarine fleet.

Oberon class submarines of the 1 st Submarine Squadron

(NP)

NBCD (Nuclear, Biological and Chemical Defence) In the late 1950s the Royal Navy developed new defensive measures and procedures against the very real threat of modern nuclear, biological and chemical weapons. Ships were designed and built with isolation ‘citadels’ and upper-deck spray systems enabling them to close down and continue to operate whilst under attack from NBC weapons. NBCD exercises became an important element of general training.

NAVAL PERSONNEL

In 1957 the Royal Navy was manned by 121,500 officers and men, a considerable reduction from the 865,000 in uniform only twelve years earlier in 1945. Various personnel changes had been introduced in the late fifties to improve professionalism and conditions of service. The 1956 Armed Forces Pay Code increased pay, allowances and pensions. The naval estimates in the same year announced a new regular nine-year engagement, though it remained at twelve years for artificers. Centralised drafting from the shore establishment Centurion was introduced with shorter foreign drafts. As it became clear that more of those serving were married, measures were introduced to curtail long periods of separation and long foreign drafts.

Officer Structure Two main changes affected the officer structure and resulted from the COST committee (Committee on Officer Structure and Training) set up in 1954. First was the formation of the single ‘General List’ of officers on 1 January 1957; this had been set out in AFO 1/56 (Admiralty Fleet Order No 1 of 1956). The new General List consolidated into a single list the four separate professional branches of the Navy, namely: X, or Executive Branch; E, or Marine Engineering Branch; L, or Electrical Engineering Branch; and S, or Supply and Secretariat Branch. The aim was to foster an ‘all of one company’ concept with a period of common training on entry, all exercising equal powers of military command ashore, and the old distinctive coloured cloth worn between the gold stripes by non-executive officers since 1863 was abolished. The basic idea was not new, having been one of the aims of the great Admiral Jackie Fisher at the beginning of the century. Fisher’s plan was known as the Selbourne-Fisher reform after the recommendations of the Selbourne Committee, but its inception was delayed by the outbreak of World War I and then by some considerable resistance from members of the Executive Branch.

Post and General Lists The smaller fleet meant a reduced number of sea commands, which caused problems with the rationing of the important command appointments, so essential for qualification for future promotion. This problem was resolved by introducing a split list for seaman specialist commanders and captains, dividing them between the categories of Post List, known as ‘Wet’, for those who would be appointed to sea command, and General List, known as ‘Dry’, for those who would not but nevertheless would be eligible for promotion for staff and general shore appointments.

Manpower Reductions The most far-reaching effects on both manpower and morale throughout the Fleet, however, were caused by the drastic cuts of the Duncan Sandys defence review. The whole emphasis of defence policy, on high-tech modern weapon systems and nuclear deterrence, encompassed a move away from large manpower-intensive conventional forces to smaller highly trained armed forces.

Accordingly National Service was phased out and a large redundancy programme was introduced. In the Royal Navy the aim was to reduce manpower to about 95,000 by 1959. Over 2,000 naval officers and 1,000 naval ratings were compulsorily retired in the first phase.

Naval Engineering Training In 1958 the Duke of Edinburgh opened the wardroom at the new RNEC (Royal Naval Engineering College) at Manadon on the northern outskirts of Plymouth. For many years engineers had been trained at Keyham College, but that site was transferred to the Dockyard Technical College in 1959. All engineering training was then consolidated at RNEC Manadon, where facilities and courses existed for all engineer officers, including those studying for university degrees.

Over the next thirty-five years engineering training was developed to deliver nationally accredited university degree courses in mechanical and electrical engineering. Four-year courses were tailored to meet the Royal Navy’s ever-changing demands on naval constructors as well as seagoing officers of the Marine, Electrical, Weapons and Air engineering subspecialisations in response to rapid technological change throughout the second half of the century. Courses were also developed in marine engineering at MSc level for newly commissioned Special Duties List engineer officers as well as for engineering management training of junior engineer officers. Courses were also established for improving the engineering knowledge and awareness of junior warfare officers. RNEC Manadon was to educate several generations of engineer officers until its closure in 1995.

THE WHITE ENSIGN ASSOCIATION

The ‘Sandys Axe’ was not the first time the Royal Navy had been savagely cut back, and bitter memories recalled the ‘Geddes Axe’ between the wars. In 1921 the Royal Navy had been forced to carry out major manpower reductions when the country was facing a severe economic crisis. The former First Lord of the Admiralty, Sir Eric Geddes, presided over a committee, which recommended drastic reductions in naval expenditure and manpower. This became known as the infamous ‘Geddes Axe’ and was described by a senior officer: ‘the Geddes’ Axe, surely the most cruel and unjust instrument ever used on a splendidly loyal service, descended with brutal force. None of us who saw those days can ever forget the stunning effect of that monstrous measure.’ A great deal of distress and suffering was caused, and the name of Geddes was reviled by a generation of naval officers.

Steaming the Fleet (The Men Who Made the Fleet Go)

In 1958 men of ships’ Engine Room Departments had been ‘going down below’ to their steam machinery for well over 100 years: the Stoker Petty Officer (properly known as a P. O. Mechanic (E)) in his steam-faded blue overalls, some 4 hours before sailing time, to the Boiler Room to ‘flash up’ and begin to ‘raise steam’, followed some 2 hours later by the Engine Room Artificer 1st Class, in his battered, oily ‘steaming cap’, to the main engine throttle control position in the Engine Room, there to supervise draining and ‘opening out’ of the steam systems and startup of auxiliary machines such as turbo-generators and pumps. Qualified to control one Boiler Room and one Engine Room ‘Unit’ he was rated Chief Petty Officer and in larger ships, such as cruisers and aircraft carriers with more than one Unit, was followed ‘below’ by the ‘Chief Tiff’ (Chief ERA), and the Engineer Officer of the Watch; both ‘Charge’ qualified to control several Units or take sole charge of a small ship’s machinery.

Cruising at sea these men normally followed a 1 in 4 watchkeeping routine of 4 hour watches in physically arduous conditions, standing on the ‘plates’ throughout or climbing ladders on endless ‘rounds’ of machinery inspection and always in mind-numbing noise, without protection. In the Boiler Room the POM (E) hung from his handwheel controlling the boiler fans, one eye always on the boiler water ‘gauge glass’ level, especially when manoeuvring and at high power, whilst he foot-adjusted fuel oil pump speed and hand-signalled his Mechanics (E) how many fuel oil ‘sprayers’ to ‘flash up’ or shut down at the boiler front, anticipating the brusque order from the Bridge – ‘stop making black smoke’. He might respond by requesting to ‘blow soot’ – a frequent routine in the 50s and 60s, when thick black Furnace Fuel Oil (FFO) fired boilers. In the Tropics, even under Engine Room ventilation fans, they all sweated the last of the daily tot of rum from their bodies helped by pints of lime juice, supplemented with salt tablets. In the North and South Atlantic winters they froze, especially at high power in an aircraft carrier’s Boiler Room, wrapped in layers of warm clothing against rushing icy air, and all longing for bubbling hot kye (Navy cocoa) at midnight. These working conditions endured until most steam ships decommissioned, notably HMS Ark Royal in 1978 and early Leander class frigates in the mid 1990s.

Machinery Control Rooms (MCR) first appeared in Diesel-engined Ton Class minesweepers and Type 41 and Type 61 frigates in the 1950s, then installed in steam-propelled Tiger Class cruisers to provide control of machinery when engine and boiler rooms were vacated and closed down to minimise nuclear, biological or chemical contamination. But it was the MCRs of the COmbined Steam And Gas turbine (COSAG) Type 81 frigates and GMDs of the early 1960s which most dramatically changed the working conditions of a ‘steaming watch’, providing them with primary control positions whilst sitting in air-conditioned, relatively quiet comfort. Key changes were: the introduction of air-driven controls to automatically adjust boiler output and remotely control main steam and gas turbines, as well as the start-up and shut-down of auxiliary machinery; and specialised clutches allowing the synchronous engagement of main turbines to a rotating main gearbox. But the greater complexity of engine combinations via remote control threw greater emphasis on correct operating procedures and their frequent practice. However, watchkeeping life outside the MCR in any steam ship – including the LPDs of the mid-’60s and Leanders of the late ‘60s – remained physically demanding, especially to complete extensive ‘rounds’ both to monitor machinery and to counter the ever-present threat of fire from fuel and oil in large machinery spaces. Indeed these remained manned only by some of the most junior and youngest men, on their own, though backed-up by a relatively large engineering crew.

Captain Jock Morrison RN

The White Ensign Association

(WEA)

The Royal Naval Reserve and Minesweeping, 1958

The Royal Naval Reserve had Sea Training Centres (STCs) round Britain, as well as Headquarters Units. The STCs trained crews for minesweeping operations, as well as reinforcing the RN when necessary in many Branches.

The HQ Units were tied to specific RN Headquarters such as Northwood near London, Pitreavie near Edinburgh and Faslane, near Glasgow and in times of emergency or war would be called up for work in their HQs. Pitreavie was the official war alternative HQ to Northwood.

Depending on their background, officers and men came from several lists, with differing levels of training. List 3 for example was for professional Merchant Naval officers and men, and many were to prove their value in the Falklands War. The RNR [Royal Naval Reserve) also provided a means of introducing the RN to men and women who would not otherwise have had anything to do with the Navy. Even if they only joined up for short periods, their experiences and influence was most important in educating the British public as a whole, on Naval matters.

The Korean War had shown that the Russians were experts in laying mines in very large numbers, and over 100 wooden hulled Ton class Minesweepers were subsequently built. Each STC was allocated a minesweeper, and practised sweeping regularly alone or team sweeping with other RN and RNR MCMVs [mine counter-measures vessels), at weekends and on fortnightly training cruises.

Many minefields remained extant or only partially swept after World War II. The Germans used contact mines – the ones with spike triggers, often still seen at seaside resorts as RNLI collecting boxes; influence mines, which were set off by the magnetic influence of steel hulled ships, and acoustic mines which listened to engines. There were combination mines, and some that had been fitted with ship counts – they would not be activated until several ships (including minesweepers) had passed over them. These would sometimes activate themselves years after the end of World War II.

NEMEDRI10 routes had been produced for merchant shipping and telephone cables, which were deemed safe, but these were checked, and gradually the other sea areas cleared to allow fishing (and eventually oil rigs).

The RNR in the 50s had plenty of ex RN officers and senior rates, but were sometimes short of junior rates; Trinity Sea Cadet Unit at the shore establishment Claverhouse in Granton, Edinburgh, allowed Sea Cadets to go to sea regularly, including live minesweeping. (As a Sea Cadet aged 12 and a half I was allowed to shoot a short butt Lee-Enfield at the mines we’d swept). Detonating the mines allowed the crewmembers – and Cadets – to take home fresh fish.11

The RNR STCs provided a naval presence all over Britain and support of all sorts. Sadly many have been closed down for reasons of economy, and training is now concentrated on relatively few areas, including Logistics and Medical.

Lieutenant Commander Ken Napier MBE, RN

Thus when the Sandys’ axe cut naval manpower by some 26,000, to be achieved by 1962, there was a determination to avoid some of the worse suffering caused by the ‘Geddes Axe’. At the instigation of Lord Mountbatten, the First Sea Lord, an association was set up to help all those leaving the Service. This was the White Ensign Association, founded in the City of London on 24 June 1958 under the chairmanship of Admiral Sir John Eccles GCB, Kcvo, CBE.

The reason for setting up the Association was stated by Admiral Eccles as follows:

‘The present day “Axe” [The Duncan Sandys Defence cuts) is the second in this century. After the first there was much distress and waste, particularly amongst ex-naval officers who, because they had spent the majority of their adult life afloat, were comparatively unversed in financial and commercial matters. The object of the Association is to avoid this in future.’

He added; ‘The Association is a measure of the goodwill felt for the Royal Navy by many prominent men in the City of London and elsewhere.’ The establishment of the Association was promulgated by Admiralty Fleet Order.12

The Admiralty officially recognised the White Ensign Association, and welcomed its formation as a valuable addition to the existing Regular Forces Resettlement Service under the Minister of Labour, which embraced the Officers’ Association and the Regular Forces Employment Association.

The Association was not a profit-making organisation. Funds, sufficient to cover its expenses for a limited period, would be donated by the business institutions which sponsored its formation.13

The Council and Staff A Council of Management was formed of thirteen leading people, chairmen, managing directors and senior partners drawn from the City, commerce and industry under the presidency of David Robarts, Chairman of the National Provincial Bank. An office was established in the City, and Commander Charles Lamb DSO, DSC, RN was appointed as the first Manager.

Commander Charles Lamb Commander Lamb was a naval Swordfish pilot who had an illustrious career in the Fleet Air Arm. He had survived the sinking of the aircraft carrier Courageous, flown at the Battle of Taranto, escaped as a prisoner of war and been seriously wounded in the Pacific campaign whilst serving in the aircraft carrier Implacable. He was to serve as Chief Executive of the White Ensign Association for fifteen years.

Work In its first two years of operation the White Ensign Association directly assisted 1,453 officers and men. Financial advice and guidance was provided on gratuities and redundancy lump sums and, with the help of financial expertise in the City of London, an investment trust, the Sheet Anchor Investment Company, was formed on 11 September 1959, open to all qualified to use the services of the Association.