The Strategic Nuclear Deterrent and Beira Patrol 1965–1969

WITHDRAWAL FROM EAST OF SUEZ – CVA-01 CANCELLED – ROYAL NAVY TAKES OVER THE NUCLEAR DETERRENT – INDONESIAN CONFRONTATION – TIGER TALKS – BEIRA PATROL – ADEN EVACUATION

FIRST SEA LORDS Admirals Begg and Le Fanu

SECOND SEA LORD Admiral Dreyer

MANPOWER 97,000

MERCANTILE MARINE 4,538 merchant ships

The passing of the imperial era was marked on 24 January 1965 when Sir Winston Churchill, the last great icon of the British Empire, died. An ex-First Lord of the Admiralty and Prime Minister, he had steered Britain to ultimate victory in World War II and remained the symbol of Britain’s greatness. It was fitting that the Royal Navy had the honour of providing the gun carriage for the state funeral and leading the procession on 30 January.

In the Far East the USA was being drawn into the war in Vietnam with bombing of the North starting in February 1965, followed by the landing of Marines in the South at Da Nang on 8 March. By the end of the year there were over 184,000 US troops in Vietnam, and the war was to drag on for ten years.

MAJOR CHANGES FOR UK NAVAL STRATEGY

New NATO Strategy In 1967 NATO strategy underwent a fundamental revision. Awareness of the dangers of the ‘Trip Wire’ (immediate nuclear response) strategy and the growing ability of the Warsaw Pact to respond with strategic nuclear weapons necessitated a major revaluation by the West. As a consequence NATO evolved a new military strategy set out in Military Committee Paper 14/3, known as ‘Flexible Response’. The essence of the new strategy was an escalating series of graduated military responses to any Warsaw Pact aggression, rather than an immediate all out nuclear strike.1

Naval Strategy and Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) The new military strategy was to have a fundamental impact on naval strategy and planning for the Royal Navy. The old strategy envisaged a short war scenario with no time for reinforcement or resupply convoys, whereas the new strategy saw the probability of a much longer campaign where reinforcement of Europe would be essential to success.

The reinforcement of Europe depended on resupply across the Atlantic with large convoys. ASW and the defence of NATO convoys transporting vast quantities of troops, arms, ammunition, equipment and supplies would be a prime requirement of NATO navies. Equally the destruction of those convoys would be crucial to the strategy of the Warsaw Pact and thus the main target of the Soviet Northern Fleet. It was in this area that the Royal Navy, with its expertise in ASW, would be required to play a leading role against the threat from the huge Soviet submarine fleet. The expertise of the Royal Navy in ASW was second to none and was one of its most important contributions to NATO. During the Cold War the Royal Navy was to build over 120 ocean escorts.

The UK At the same time political changes in the UK and the USSR were to have a profound effect on UK defence policy in the second half of the sixties. In 1964 a Labour government under Harold Wilson had been elected to power in Britain, and on the same day Khrushchev had been ousted in the Kremlin to be replaced by the hard-liner Leonid Brezhnev.

The Labour government went on to seek an election in March 1966 and was returned with an increased majority of ninety-seven.

Defence Review The new Labour government faced a massive balance of payments deficit and a collapsing currency. Denis Healey, the new Secretary of State for Defence, initiated a fundamental defence review in 1965, based on the new government’s political priorities and the growing economic crisis.

The overriding factor was the need to drive down public spending, and defence was again the prime target. Healey saw the answer in placing full reliance on nuclear deterrence to prevent war in the European area, whilst at the same time maintaining just sufficient conventional forces to cover commitments outside the NATO area. In addition, he saw that progressively reducing those commitments beyond the NATO area would enable the supporting conventional forces to be cut back even further, yielding greater savings. In his 1965 Statement on Defence Healey stated: ‘it was neither wise nor economical to use military force to seek to protect national economic interests in the modern world’.2

The Defence White Paper, setting out the findings of the fundamental defence review, was published on 22 February 1966 and, as expected, entailed major defence cuts.3 The review, which came to be known as the ‘Healey Axe’, called for the withdrawal of British forces from East of Suez and an end to British commitments in the Far East.

Abolition of the Carriers For the Royal Navy the review set out to abolish the Fleet Air Arm and the aircraft carriers. The new aircraft carrier was to be cancelled and the existing aircraft carriers all phased out by 1977. All air defence would become the responsibility of the Royal Air Force, operating from the United Kingdom and overseas island bases. The air defence of the Fleet was to be based on guided missiles, whilst other fixed-wing airborne tasks, such as AEW (airborne early warning), ASW, screening and strike, were to be assigned to naval helicopters.

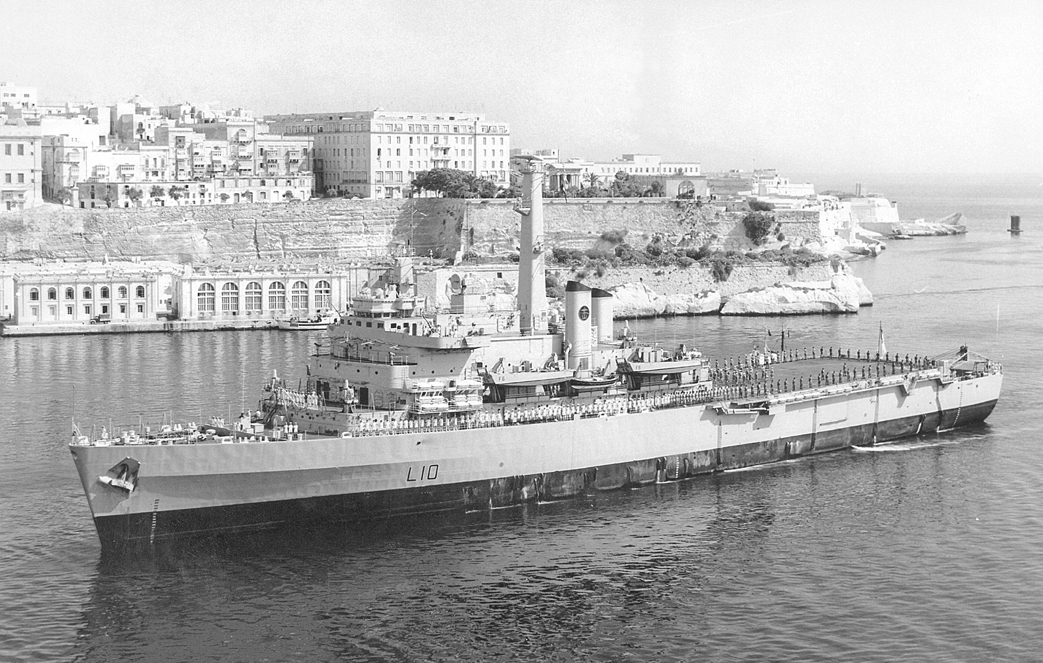

Hermes as converted to a commando carrier

(RNM)

It was considered that aircraft carriers were too vulnerable to long-range missiles and too costly to build, man and maintain. Approaches had been made to the US government to investigate the possibility of buying or leasing a US aircraft carrier but to no avail. The Royal Air Force had suggested to the Treasury that the BAC TSR-2 tactical strike aircraft be procured in place of new aircraft carriers. In the event the Treasury cancelled both the TSR-2 and the new aircraft carrier.

Cancellation of CVA-01 The tragedy for the Royal Navy was the cancellation of the new-generation 50,000-ton fixed-wing strike aircraft carrier CVA-01, announced in July 1963 (see Chapter 2). Much of the money saved was to be devoted to the purchase of fifty US General Dynamics F-111A strike aircraft and some McDonnell Douglas Phantoms for the Royal Air Force. The pro-carrier lobby rightly protested that the RAF would not be able to provide proper air cover for the Fleet or for Atlantic convoys in any major war with the Warsaw Pact. Mr Christopher Mayhew, the Minister for the Navy, and Admiral Sir David Luce, the First Sea Lord, resigned, as they had threatened to do if such a policy was imposed.

The distress felt throughout the Navy was profound and the new First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Varyl Begg, appointed in April 1966, had a major task to rebuild confidence and morale throughout the Fleet. He set up a project team to plan the future navy without the backbone of the new carrier. Rear Admiral Adams headed the project in the newly formed post of Assistant Chief of Naval Staff (Policy) (ACNS (P)).

THE FLEET

In 1965 the Royal Navy continued to be cut back, and although it still possessed a powerful fleet, decisions in 1968 were to impose far-reaching cuts in its size and capability.

Aircraft Carriers The capital ships of the Fleet comprised the remaining aircraft carriers Ark Royal, Eagle and Hermes (Centaur was paid off in 1965 and was used as a depot ship, whilst Victorious was scrapped in 1968 after a fire on board). Eagle had just been commissioned in May 1964 following a four-year major refit and modernisation. In 1967 Ark Royal commenced her major three-year modernisation refit, to enable her to operate the new heavy Phantom strike-fighter aircraft. Later it was decided to convert Hermes to a commando carrier in 1970.

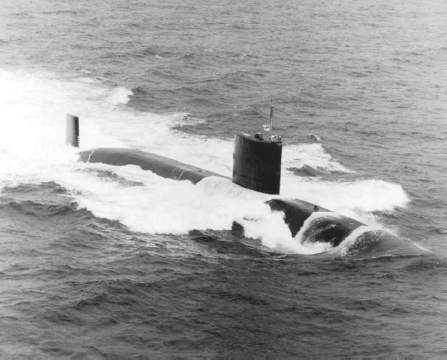

The new capital ships of the Navy, the nuclear-powered submarines, were about to join the Fleet, with the first four SSBNs (nuclear ballistic missile submarines) of the Resolution class being completed between 1967 and 1969. By 1969 three nuclear fleet submarines (SSNs) were in service, with five more under construction.

The assault ships Fearless and Intrepid were completed between 1965 and 1966. The Tiger class cruisers Tiger and Blake were converted to ASW command cruisers and equipped to carry four Sea King helicopters between 1965 and 1973. In 1968, however, the decision was taken not to convert the third cruiser, Lion.

The rest of the Fleet included thirty-eight destroyers, eighty-nine frigates, forty-two conventional diesel-electric submarines and several hundred minesweepers and smaller patrol boats and craft. The Fleet was well supported by the survey ships of the Survey Flotilla and by the supply ships and tankers of the Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA).

Western Fleet In 1967 the fleet structure of the Royal Navy was reordered to reflect the reduced number of ships. The fleets were rationalised into two fleets, and the Home Fleet became the ‘Western’ Fleet.

FIRST SEA LORDS

Admiral Sir Varyl Begg Varyl Begg was born on 1 October 1908 and joined the Royal Navy in 1926. In 1931 he joined the cruiser Shropshire as a lieutenant, and after specialising in gunnery he served as Gunnery Officer of the battleship Nelson. During World War II he served in the cruiser Glasgow and the battleship Warspite, and was awarded the DSC for his part in the Battle of Matapan.

After the war he commanded the Gunnery School in the rank of Captain before commanding the 8th Destroyer Squadron during the Korean War and being awarded the dso. He then commanded the aircraft carrier Triumph, and subsequently, as a rear admiral, he commanded the 5th Cruiser Squadron. He served as Assistant Chief of the Naval Staff from 1961 to 1963, and then as a full admiral he was Commander in Chief Far East during the Indonesian Confrontation.

In 1965 he was appointed Commander in Chief Portsmouth, but when the First Sea Lord, Admiral Luce, resigned over the decision to phase out the aircraft carriers Admiral Begg relieved him. He remained as First Sea Lord until his retirement in August 1968.

Admiral Sir Michael Le Fanu Michael Le Fanu was born on 2 August 1913 and joined the Royal Navy in 1926. As a junior officer he served in the Dorsetshire, York, Whitshed and Bulldog, and during World War II he served in the cruiser Aurora, taking part in the Bismarck campaign. Later he was awarded a DSC for his part in a night engagement whilst serving with Force ‘K’ in the Mediterranean. He also served in the battleship Duke of York, and after the war he served in the cruiser Superb, before commanding the 3rd Frigate Squadron.

He commanded the training establishment HMS Ganges and then served as Flag Captain in the aircraft carrier Eagle. As a rear admiral he was Second in Command Far East, flying his flag in the carrier Hermes, before being appointed Controller of the Navy as a vice admiral in 1961. As Controller he was credited with the hugely successful Leander class frigate programme.

In 1965 he was appointed Commander in Chief Middle East, and in this post he oversaw the withdrawal from Aden in 1967. He was appointed First Sea Lord in August 1968 and faced the difficult task of rebuilding the spirit of the Navy after the damaging cuts and reductions of the Healey defence review.

OPERATIONS AND DEPLOYMENTS, 1965–1969

Throughout the second half of the sixties the Royal Navy continued to be engaged on a whole range of operational deployments and important peace-keeping tasks around the world. First and foremost was the national strategic deterrent.

The Nuclear Deterrent On 14 June 1968 the SSBN Resolution sailed from Faslane to carry out the first submarine nuclear deterrent patrol in the vast depths of the ocean. She carried her full load of sixteen Polaris ICBMs (intercontinental ballistic missiles).

The following year, with sufficient SSBNs in service to maintain the deterrent patrol cycle, the Royal Navy assumed responsibility on 1 July for the national strategic nuclear deterrent from the V-bomber force of the Royal Air Force:‘to ensure a submarine deterrent remained totally credible at all times, it required that, for week upon week when at sea, the crews were in all respects equivalent to being on patrol under conditions of war. Likewise to keep the submarines at sea on a schedule permitting not the slightest variation required a similar approach from all those who worked ashore.’4

‘Delousing’ Operations The location of the British Polaris deterrent base was not secret, and so it was easy for the USSR to send submarines to lie in wait outside the Firth of Clyde to try and trail a Polaris submarine as it deployed to its patrol area. To guarantee the strategic deterrent, it was essential for deterrent patrols to remain undetected and thus invulnerable. This meant that it was necessary to deploy submarine escorts and ASW surface ships in ‘delousing’ operations to protect Polaris submarines and ensure they were not tailed.

Covert Submarine Operations Britain and the USA continued to monitor closely the rapidly expanding Soviet Submarine Fleet. In 1963 the USSR had twenty-six nuclear submarines, and by late 1969 they had forty-three SSBNs and seventeen SSNs. The first of the powerful 9,600-ton Yankee class SSBNs was commissioned in May 1967 and was rated by NATO as good as the Polaris SSBNs. In addition the USSR had fifty missile-armed diesel-electric submarines and 263 other conventional submarines.

US and British submarines maintained a demanding series of covert surveillance operations. These consisted of ‘close-in’ intelligence-gathering patrols off the main Russian naval bases and fleet training grounds in the Barents Sea.

The Royal Navy carried out its share of the important task and continued to deploy conventional diesel-electric submarines, adapted for surveillance with top-secret intelligence intercept equipment, on missions in the Barents Sea off the Murmansk naval base and in the Kola Inlet.

These were dangerous operations, and submarine commanders were fully aware of the difficulties and huge risks if they were detected. One Royal Navy submarine was apparently detected in 1966 in the Barents Sea off Murmansk but managed to elude her pursuers. There were other cases when submarines were attacked and depth-charged.

The following year a Soviet submarine hit a US Polaris submarine in the Mediterranean. In 1968 the USSR claimed that a NATO surveillance submarine, British or American, was involved in a collision with a Soviet nuclear submarine in the Barents Sea, but were not able to determine which navy was responsible. Towards the end of the next year there was yet another collision, this time between a US SSN and a Soviet Hotel class SSBN.

One of the tasks of the surveillance operations was to detect any sudden surge (deployment of a large number of Soviet submarines), which could be a precursor to imminent hostilities, and provide valuable warning time. Towards the end of the 1960s SSNs started being assigned to the surveillance operations. The introduction of SINS (the Ship Inertial Navigation System) made possible much more accurate navigation. In April 1967 the nuclear fleet submarine Valiant returned to the UK from Singapore, carrying out the entire 12,000-mile passage under water.

The Grand Harbour, Malta, in the mid-1960s

(RNM)

Other Operations and Deployments In Hong Kong the three Ton class minesweepers of the 8th Minesweeping Squadron (Fiskerton, Woolaston and Wilkieston) carried out guardship duties and were periodically deployed south to assist with defensive patrols off the east coast of Malaysia. In the Persian Gulf the four Ton class minesweepers of the 9th Mine-sweeping Squadron (Appleton, Flockton, Kemerton and Chilcompton) carried out security patrols against arms smuggling, piracy, slaving and insurgent infiltration. The minesweepers were based in Bahrain (Jufair, which was the headquarters of ‘SNOPG’, the Senior Naval Officer Persian Gulf, was the shore base at Bahrain). Frigates supported the minesweepers on a regular basis. In May 1966 the Tribal class frigate Gurkha embarked a company of troops and sailed for Abu Dhabi. Arriving on 7 May, she stood by during an important oil dispute and her presence was sufficient to bring the dispute to an end after only two days.

Further south in Aden, a garrison unit of Royal Marines from 45 Commando was deployed for anti-rebel operations in both east and west Aden and for internal security duties.

In the Mediterranean, Malta, which had been the base of the Mediterranean Fleet for a great many years, experienced a considerable run-down. By 1965 the only ships permanently based in Malta consisted of a squadron of destroyers or frigates and a minesweeping squadron of six Ton class minesweepers, including Walkerton, Leverton, Shavington, Crofton, Ashton and Stubbington. In June 1967, with the formation of the Western Fleet, the flag of the then Commander in Chief Mediterranean (Admiral Sir John Hamilton) was hauled down for the very last time. Then in 1969 the minesweepers were withdrawn and mothballed in Gibraltar.

The 6th Minesweeping Squadron was based in Singapore for guardship duties. Singapore was of great strategic importance and its dockyard was a large fully operational naval base, with a drydock, built for the largest ships, and a floating dock. Triumph, the fleet repair ship, was based there, and the Inshore Flotilla was run from the fast minelayer Manxman, converted as a minesweeper support ship. The air station at Changi, took disembarked NAS (naval air squadrons) and included a large wireless station, a hospital, gunnery ranges, a fuel tank farm, stores and ammunition depots, a barracks (HMS Terror) and extensive supporting facilities. The Commander Far East Fleet was Vice Admiral Sir Frank Twiss.5

In the Antarctic Protector was deployed for service in the Falkland Islands Dependencies during the Antarctic summer. Protector was a converted netlayer fitted out for guardship and Antarctic survey duties. In 1968 Endurance, with a Royal Marine detachment embarked, took over responsibility from Protector for the protection of British interests in the Antarctic.

NATO Naval Squadrons In January 1968 a permanent NATO Naval Squadron was established with the UK, the USA, Canada, West Germany and the Netherlands each contributing a destroyer or a frigate. The forerunner of the squadron had been the British annual exercise codenamed Matchmaker which combined destroyers and frigates from NATO countries to deploy together as a joint squadron. The Royal Navy allocated the frigate Brighton to join the permanent NATO Squadron when it was formed at Portland under the command of Commodore G C Mitchell rn. Brighton was relieved later in 1968 by the new Leander class frigate Dido. The squadron became the Standing Naval Force Atlantic (STANAVFORLANT, or SNFL for short), and each nation took it in turn to command the squadron on an annual basis. Norway, Denmark, Belgium and Portugal assigned ships to join the squadron from time to time. SNFL enabled NATO ships to develop and improve joint tactics and operating procedures and regularly took part in joint maritime exercises.

The following year a second NATO squadron was formed to cover the Mediterranean, but on an ‘on call’ basis to respond as required, the Naval On Call Force Mediterranean (NAVOCFORMED). The force was regularly activated to participate in NATO maritime exercises.

NATO Flanks Towards the end of the sixties the Commando Brigade reduced its commitment to the Southern Flank of NATO and took over a more important role in the defence of the Northern Flank in Norway. It was on the Northern Flank that highly trained and hardened amphibious forces would be essential. The strategic objective would be to deny the Warsaw Pact access to the airfields of northern Norway, where their strike aircraft would be able to extend their range far out in the Atlantic. As a consequence of the change of role, 45 Commando, recently returned from Hong Kong, was to be based in Arbroath in Scotland, and in 1970 it was assigned to NATO specifically for the Northern Flank. The Royal Marines specialised in winter and mountain warfare, with regular deployments to the Northern Flank such as the annual reinforcement exercise Polar Express. The commando carrier Bulwark was deployed to Norway in Polar Express for the first time in June 1968 with twenty Wessex V helicopters of 845 NAS and 650 Royal Marines of 45 Commando embarked.

Indonesian Confrontation, December 1962 – 11 August 1966

In the Far East in 1965 the Royal Navy remained very heavily involved in the Indonesian Confrontation, defending Malaysia, including Singapore and North Borneo, against attacks from Indonesian forces. Indonesia continued to launch attacks across the Malacca Strait to infiltrate the mainland of Malaysia in an attempt to destabilise the local population. Ships of the Far East Fleet, reinforced by units of the Royal Australian Navy and Royal New Zealand Navy, provided the regular security patrols off the coast. The struggle was to continue until the signing of the Bangkok Agreement in August 1966.

On 8 January a bomb, planted by Indonesian raiders, exploded on board the merchant ship Oceanic Pride in Singapore. That night the Ton class minesweeper Wilkieston intercepted a small Indonesian craft trying to escape from the harbour. One Indonesian was captured and another was seen to leap overboard. It was subsequently discovered that they had been part of the attack team which had planted the bomb on board the Oceanic Pride. The economy of Singapore was totally dependent on seaborne trade, and threats to shipping in the harbour were taken very seriously. The security authorities imposed a night curfew in Singapore harbour and the small Malaysian Navy was involved in various incidents with Indonesian raiders along the coast.

The commando carrier Bulwark embarking Royal Marines of 45 Commando for deployment to exercise Polar Express off Norway

(RNM)

Ton class wooden minesweeper Woolaston

(RNM)

In March 1965 General Suharto took over from Sukarno, but the attacks against Malaysia and Singapore continued. At the same time General Waite-Walker, in command of British forces in Borneo, handed over to General Lea.

On 28 March there was a sharp engagement between two heavily armed Indonesian landing craft and the Ton class minesweepers Maryton, Invermoriston and Puncheston. The landing craft were trying to land soldiers on the south coast of Malaya. The gun battle lasted over an hour before one of the landing craft was sunk. Three ratings were wounded in the action, with seven Indonesians killed and nineteen captured. A little while later the Ton class minesweeper Lullington captured another Indonesian raiding party. In a further engagement with Indonesian raiders Maryton sustained fifty bullet holes. In one incident Midshipman Michael Finch, from the minesweeper Woolaston, was killed when trying to rescue an injured Indonesian from a captured Indonesian patrol craft. The craft had been booby-trapped and blew up. Midshipman Finch and Midshipman Michael O’Driscoll, killed in Invermoriston, were given posthumous mentions in despatches.

Naval helicopters from the County class destroyer Kent in Borneo

(RNM)

In April the Malaysian Navy took over responsibility for inshore coastal patrolling and naval party‘Kilo’ (see Chapter 2), based at Kuching, was disbanded.

The Indonesian Navy was headed by Irian, an ex-Russian Sverdlov class cruiser, and included numerous ex-Russian destroyers and frigates, as well as modern European-built escorts, scores of patrol craft including modern German-built fast patrol boats (FPBs) and twelve ex-Russian ‘W’ class submarines. The potential threat was therefore very serious.6 On the Indonesian border with North Borneo several Indonesian battalions were deployed with artillery, notably at the western and eastern coasts of Borneo (Kalimantan). Attacks on Malaysian civilians by land continued, and it was necessary to deploy British battalions all along the mountainous jungle-covered border, in places up to 2,400 metres high. Forward-deployed Royal Navy helicopters, operating seven days a week in very trying conditions, supported them. In many cases helicopter support, in and out, was the only practical means of transport, as the fighting patrols on the border were up to a month’s march from the coast.

The commando carrier Albion, ‘The Old Grey Ghost of the Borneo Coast’

(RNM)

Throughout the Confrontation the commando carriers Albion and Bulwark played a major role and clearly validated the new commando carrier concept. They alternated on station off the coast of North Borneo and in the Strait of Malacca acting as offshore bases operating helicopters to take Royal Marines, army units and supplies to forward bases and patrols deep into the jungle.

During the Confrontation, between April 1965 and July 1965, Albion’s eighteen Wessex and two Whirlwind helicopters of 848 NAS flew 5,000 hours, transporting 12,000 men and 5,000,000 pounds of freight in Sarawak.7

In December 1965, Albion was going back to Singapore after a roulement to Labuan when an Indonesian patrol boat attacked her. The gunboat opened fire with 40mm guns at close range. Albion, which was commanded by Captain Godfrey Place vc (decorated for his attack on the German battleship Tirpitz during World War II), promptly rammed and sank the gunboat. Sadly the action damaged the bow of the commando carrier and she had to go into the drydock in Singapore for repairs, which put her out of action for a few months.8

In the summer two Royal Navy SR.N5 hovercraft arrived in Borneo, where they operated in the rivers and swamps (see Chapter 2). They carried out valuable work over a period of six months, demonstrating the reliability of such craft, which were later to be used in large numbers by the United States Navy in Vietnam.

Wessex helicopters operating from the commando carrier Albion off Borneo

(NN)

‘Hearts and minds’ operations were critical, and the local villagers (many of whom had only recently given up headhunting) welcomed the visits from the Royal Navy minesweepers on patrol from Kuching, or Tawau, with medical and other support. Rigid raiders were used to penetrate up the many rivers to reach distant villages. The Indonesians were not the only enemy as there had been frequent pirate raids from both the Philippines and Indonesia before the Royal Navy patrols commenced.9

Minesweepers, operating close inshore and up to the border, were within easy gunnery range of the Indonesian heavy artillery. Heavier support in the form of a frigate or destroyer on patrol further off shore was usually available. The wooden minesweepers were vulnerable to modern weapons, and several had many bullet holes, frequently running right through from side to side. Many of the Ton class minesweepers had their after 20mm gun replaced by a second 40mm Bofors gun and carried Vickers fixed machine guns, Bren guns, mortars and small arms.10 Searching small craft such as fishing kotaks or slightly larger kumpits was risky, and in at least one case a kotak blew up alongside a minesweeper that was searching it, killing members of the boarding party.11

By night off Singapore and in the nearby Malacca Strait, up to fifteen ships were deployed, reducing to two by day; most were minesweepers and patrol craft supported by frigates and destroyers.

Royal Fleet Auxiliaries were present in strength, in varying sizes, from the new fleet tanker RFA Tidespring down to the small Eddy class support tankers. Other support ships included the British and Indian Steam Navigation Company’s Empire Kittiwake, a converted army tank landing ship, which was used to ferry wheeled 40mm Bofors guns to and from Borneo. The civilian crews were paid a 30 per cent bonus to man their four 20mm Oerlikon guns.

Fotex 65: Far East Fleet, March 1965 The heavier fleet carriers reinforced the ships deployed off Borneo and in the Malacca Strait from time to time. In February 1965 the carrier Eagle sailed from Hong Kong to Singapore, where she operated with units of the Far East Fleet. The high point was an impressive show of force when she took part with the aircraft carriers Victorious, Bulwark and HMAS Melbourne in exercise Showpiece and Fotex 65 in March. The fleet manoeuvres were witnessed by Tungku Abdul Rahman, Prime Minister of Malaysia, and served as a useful highprofile demonstration of sea power and the strength of Britain’s commitment to defending Malaysian interests. Eagle then sailed for home and refit in the UK.

The End of the Confrontation By the end of 1965 the Royal Navy had notched up 500 days of patrols during the Confrontation. In that time it had killed or captured over 1,400 Indonesian raiders for the loss of two officers and eleven ratings.12 The Confrontation continued into the following year, and in January the Ton class minesweeper Dartington came under heavy fire from shore batteries whilst escorting Malaysian vessels. The following month the minesweeper Puncheston and a Malaysian patrol boat came under fire from shore batteries on the Rhio islands in the Malacca Strait (over a hundred shells were fired by the shore batteries). Then in March the minesweeper Picton was attacked but fortunately was not seriously damaged. The Navy was deploying more submarines to the area, as they were proving most useful in conducting covert coastal patrols. To support them the submarine depot ship Forth was being prepared for the Far East.

HMS Maryton during the Indonesian Confrontation

When I joined the Ton class minesweeper Maryton in early 1965, she had over 300 varied bullet holes in her – some double, i.e. in one wooden side and out the other. My Chinese cook and steward were unimpressed, as their ‘action station’ was the Wardroom Flat – with bullets coming in one side and out the other.

The Captain, Lieutenant Commander Doug Holder, was awarded a DSO and the Leading Seaman gunner, a DSM; the ship had fought a successful engagement against several Indonesian fast craft with huge outboards.

The job of my men was to carry ammunition to the various gun positions: we had two 40mm Bofors (one had replaced the normal twin 20mm Oerlikon aft), six Vickers machine guns (two twins and two singles), three Bren Guns, a couple of rocket flare launchers and a mortar on the bridge roof. Everyone not involved with those had Sterling submachine guns, or in my case as prisoner reception, a 9mm Browning pistol. When we opened fire at night it was spectacular.

As prisoner reception, I had two very large sailors who swung the prisoner from the jumping ladder (only a few feet above sea-level) onto the engine room bulkhead where he was thoroughly searched – they had a trick of hiding hand grenades on their person. On a number of occasions I had to swim out with a grapnel to the stopped Indonesian craft, or perhaps a kumpit, a slower and larger goods carrying boat, as the outboards and cargo were valuable. Sometimes the boats were also carrying contraband like cigarettes. We would then tow the boat back to base.

The swim was OK by day but dangerous at night, as the lights of the action could attract sea snakes and large stinging jellyfish which were of course very difficult to see at night.

Lieutenant Commander Ken Napier MBE, RN

Frigates on Beira Patrol

(JAR)

Indonesia and Malaysia held serious negotiations in the summer, which were to lead to the Bangkok Agreement and the eventual end of the conflict. The last Borneo patrol was conducted by Dartington in September, and the following month the naval helicopters were withdrawn from Sarawak.

The Secretary for Defence, Denis Healey, announced in Parliament that the Royal Navy had successfully intercepted over 90 per cent of the Indonesian attempts to invade western Malaysia.13

The Royal Marines, who were highly skilled in jungle warfare, fought with great distinction throughout the Confrontation. There was always a Commando, usually 40 or 42 Commando, deployed in Borneo during the entire campaign. Not only had the Royal Marines been the first forces engaged but they were also amongst the last to leave. They were extremely effective and suffered only thirty-six casualties (sixteen of them fatal).

Aden and the Radfan

The Radfan Operations by British forces against rebel Yemeni tribesmen continued in the mountains of the Radfan in southern Arabia. On 4 June 1965 a flight of four Wessex was disembarked from Albion and flown up to provide additional forward support. It was during this period that the Royal Marines in Aden and the Yemen were instructed to stop using the expression ‘Wogs’ to avoid causing offence to local people. The Royal Marines readily complied and thereafter referred to local people as ‘Gollies’.14

Aden Whilst in Aden itself the internal security situation deteriorated further and the Governor, Turnbull, was forced to declare a state of emergency. The National Liberation Front (NLF), which was behind much of the agitation and violence, was proscribed. In August the police superintendent and the Speaker of the Assembly were murdered, and then on 23 September schoolchildren were attacked with grenades. Turnbull dismissed President Mackawee and direct rule was imposed.15

In view of the serious political situation Britain decided to send the aircraft carrier Eagle to Aden. 45 Commando was already in Aden and could be embarked on board Eagle if necessary. Eagle was in Malta in September having completed an ASW exercise with the US 6th Fleet, exercise Quick Draw. Accordingly Eagle sailed from Malta, escorted by the frigate Lowestoft and the RFAS Tidesurge and Reliant, and headed east for the Suez Canal en route for Aden.

After a fast passage Eagle anchored off Aden on 1 October and commenced supporting the British forces engaged in maintaining defensive patrols ashore. Her helicopters greatly assisted in internal security operations for a busy period of nine days before she was released to sail to Mombasa for a maintenance and rest period.

Gannet Rescue, 12 October It was a short while later, whilst Eagle was conducting flying operations in the Indian Ocean, that a remarkable recovery occurred. A Gannet aircraft crashed into the sea on launch, and sank dead ahead of the aircraft carrier. Eagle thundered straight over the top of the sinking Gannet at full speed. Amazingly the three members of the crew came to the surface astern of the aircraft carrier clear of the propellers and were picked up safely by the plane guard helicopter, hovering on the port quarter. After leaving Mombasa on 23 October Eagle steamed east, arriving in Singapore on 3 November.

Zambia and UDI, 11 November – 7 December 1965 On 11 November 1965 Ian Smith, the Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia, made a unilateral declaration of Rhodesian Independence (UDI). This action was condemned by the United Nations, but the international community expected Britain to deal with the problem.

President Kaunda of Zambia appealed to the UK for support and in particular for air defence protection. He wished to ensure the safety of the vital Kariba Dam. The aircraft carrier Eagle was by this time in Singapore preparing for a visit to Hong Kong, and was sent an immediate signal on 18 November to prepare for sea. Two days later she sailed from Singapore, escorted by the frigate Brighton, and embarked her aircraft as she steamed through the Malacca Strait. The ships headed west across the Indian Ocean, passing Gan four days later. Eagle then arrived off the coast of Tanzania on 28 November and was fully ready to operate her aircraft in defence of Zambia. She was by this time supported by four frigates.

The carrier Eagle sails from Malta heading east at speed

(NN)

At the same time arrangements were being made to fly ten RAF Javelin aircraft to the region from Cyprus, but problems were being experienced in obtaining over-flight clearance. Eventually the RAF Javelins arrived in Ndola on 3 December and Eagle was able to stand down from her operational state and leave the area. Four days later she sailed north for a break in Mombasa and then on to Aden to resume flying operations. The incident clearly demonstrated the flexibility of naval air power. The Times reported, ‘the sudden appearance of the aircraft carrier Eagle cruising off Tanzania emphasises the advantages and flexibility held by a carrier in the Indian Ocean.16

The frigate Zulu returning from for the Beira Patrol. In 1967 she spent more than 120 days on the patrol, intercepting only four ships

(NJBM)

The Beira Patrol, 1 March 1966 – 25 June 1975 On 20 November 1965 the Security Council of the United Nations instituted a regime of voluntary sanctions against Rhodesia. The Security Council Resolution (UNSCR 217) called for an international embargo on all shipments of oil to Rhodesia. Britain was unwilling to use direct force to intervene in its own colony but nevertheless was fully aware of the need to be seen to be doing something in the eyes of the rest of the world. The government of Prime Minister Harold Wilson hoped that sanctions would work, but it became clear that oil was reaching Rhodesia. In February 1966 the Chiefs of Staff considered that tankers could be arriving in the port of Beira unobserved and recommended a maritime surveillance plan. The Rhodesian Minister of Commerce and Industry even announced that tankers would be arriving in Beira and that in consequence they would have managed to defy the international community and achieve their goal of white rule in the face of economic sanctions.

On 1 March 1966 Britain instituted the Beira Patrol, and the frigate Lowestoft was ordered to head for the port of Beira and to be prepared to intercept suspect tankers. On 3 March the carrier Ark Royal, escorted by the frigate Rhyl, sailed from Mombasa but instead of heading for Singapore she was ordered to operate her Gannet AEW aircraft to search the Mozambique Channel for tankers. Intelligence indicated that the tankers Joanna Vand Manuela were en route to Beira and that oil tanks were being constructed in the port of Beira. On 15 March Eagle arrived off the Mozambique Channel to release Ark Royal to continue en route to Singapore. Eagle had to launch AEW surveillance aircraft straight away, as the RAF Shackletons (maritime patrol aircraft), ordered to Mombasa for the surveillance task, had not arrived.

Once again aircraft carriers had to meet a task that the RAF had been given but had not managed to carry out in time. By the 19 March, however, the Shackletons were flying regular surveillance patrols from Majunga in Madagascar. Ironically newspapers in the UK had been showing photographs of aircraft flying patrols in the Mozambique Channel, and claimed they were RAF aircraft even though they were AEW Gannets from Eagle, clearly marked ‘Royal Navy’.

The ‘Tiger Talks’: Prime Minister Harold Wilson on the quarterdeck of the cruiser Tiger

(JAR)

The destroyer Cambrian and the frigate Plymouth were patrolling close inshore monitoring all shipping approaching the port of Beira, whilst RFAS Reliant, Resurgent and Tidepool were further out to sea in support of the patrol. On 17 March the fully laden tanker mv Enterprise was intercepted by Eagle approaching Beira, but on being challenged claimed that she was bound for South America instead and sailed away. The tanker mv Joanna Vwas intercepted by Plymouth, but as the Royal Navy had not been authorised to use force the Joanna Vwas able to break away and sail into territorial waters at Beira. Eventually the United Nations authorised the Royal Navy to use force if necessary (UNSCR 221) and also authorised the Royal Navy to arrest the Joanna V if she departed from Beira having discharged any oil.

Various tankers were intercepted. On 8 April the frigate Berwick intercepted the tanker Manuella and escorted her well clear of the Mozambique Channel; however, after Berwick had departed to refuel, the Manuella reversed her course and made a run for Beira again. This time the frigate Puma intercepted and prevented the tanker reaching Beira.

On 30 April Eagle was authorised to leave the area and proceed to Singapore for a maintenance period. During her time off Beira she had identified 116 tankers and 651 other ships in the area. Ark Royal arrived in the Mozambique Channel on 7 May to resume the Beira Patrol before finally leaving the area on 25 May to head north for the Suez Canal and return to the UK. The Beira Patrol was to continue for over nine years.

The ‘Tiger Talks’, 1–3 December 1966 On 30 November 1966 the cruiser Tiger was carrying out an official visit to Casablanca in Morocco when she received an ‘immediate’ signal ordering her to sail forthwith and head north for Gibraltar. At the same time the guided missile destroyer Fife was ordered to sail from Madeira and head immediately for Gibraltar. Once in Gibraltar high-level political delegations from Britain and Rhodesia including both Prime Ministers, Harold Wilson and Ian Smith, were embarked on board Tiger. Both ships then sailed east into the Mediterranean whilst intensive talks to resolve the problems of Rhodesia and UDI were conducted on board Tiger. The top-level meetings were dubbed the ‘Tiger Talks’. Unfortunately after two days of exhaustive discussions no solution was achieved and the ships returned to Gibraltar to disembark both groups.

With no agreement reached it was necessary to continue the Beira Patrol, and so the patrol was maintained throughout the year, mostly by two ships, frigates or destroyers, supported by RFA ships and tankers. Many ships were intercepted and escorted away from Beira. The extent of the ‘rules of engagement’ (ROE) used by the Royal Navy were tested in a difficult incident on 19 December 1967 when the frigate Minerva intercepted the French tanker Artois making for Beira. Minerva ordered the Artois to stop but the Artois refused to comply and Minerva fired warning shots across her bow, before the MoD signalled that the Artois could legitimately enter Beira. The Artois incident led to a revision of the ROE and an increased authorisation for the Royal Navy to ‘open fire and continue until the ship does stop. The revised ROE were sufficient as no further attempts were made to evade interception by the Royal Navy.

A further attempt was made to resolve the problem of UDI by a high-level conference at sea in October 1968. Under the codename Operation Diogenes, the assault ship Fearless and the guided missile destroyer Kent arrived in Gibraltar on 8 October and embarked British and Rhodesian delegations. The ships put to sea but no progress was made in the meetings and eventually the talks were called off, with the ships returning to Gibraltar on 14 October. At the end of March 1969 a final round of talks, codenamed Operation Estimate, were held at Lagos with Fearless, sailing from Malta on 15 March. The talks were held from 27 to 31 March, but yet again without a successful outcome.

Aden, September 1966 – May 1967

The situation in and around Aden in 1966 remained tense, with attacks and incidents continuing to take place. In September disturbances occurred in Mural in the East Aden Protectorate, and on 14 September the Ton class minesweeper Kildarton was sent to Mural to restore order. Armed units were also sent to Riyadh to demonstrate a show of force.

Operation Fate The brand new assault ship Fearless, which had successfully completed her trials, sailed from Portsmouth on 13 September bound for Aden. She made a fast passage, via the Suez Canal, to the Gulf of Aden, arriving off the port on 29 September. Seventeen days later she carried out her first operational task, landing a troop of scout cars some seventy miles west of Aden in a surprise operation to catch rebel tribesmen inland. The mission provided experience for Operation Fate two weeks later. On 25 October Fearless departed from Aden and steamed 500 miles east to conduct a surprise ‘cordon and search’ operation (Operation Fate) against rebel tribesmen in the Hauf region. The area was being used as a training ground for members of the Dhofar Liberation Front, and the plan was to surround and capture the rebels. The two-day operation, which was conducted with the Irish Guards and 78 Squadron RAF, was a total success. Twenty-two terrorists were captured and a vast haul of weapons confiscated.17

In the spring of 1967 the situation in Aden continued to cause much concern, and at the end of April the Chiefs of Staff determined to mount a show of force. It was decided to use naval aircraft to carry out the demonstration of power, and the aircraft carriers Hermes and Victorious were ordered to proceed to Aden.

Hermes, which had been on her way to the Far East, was in the eastern Mediterranean standing by off Athens following the army coup (the ‘colonels’ coup d’état’) in Greece on 21 April. Hermes then operated off Cyprus for a week before being released to continue to Aden. She transited the Suez Canal on 3 May and arrived off the port of Aden three days later. On 15 May Victorious, having sailed from the Far East escorted by the frigate Brighton, joined Hermes off Aden.

On 16 May there was an attack by bazooka rockets on the British Residency at Mural. Brighton and the minesweeper Puncheston immediately proceeded to the area and provided a naval presence off the East Aden Protectorate, in case of any further violence.

On 17 May the two aircraft carriers carried out an impressive show of force, with squadrons of jet aircraft roaring in low over Aden and the south Arabian territories. Over fifty aircraft took part, including Buccaneers and Sea Vixens as well as RAF Hunters. With the powerful demonstration completed the aircraft carriers sailed from Aden on 20 May. Hermes continued on her way to Singapore via Gan, whilst Victorious headed for the Red Sea on passage back to the UK. Within two weeks both aircraft carriers would reverse course and head back to a fresh crisis in the Middle East.

The assault ship Fearless

(RNM)

Fearless

Landing Platform Dock

The assault ships (officially landing platform docks or LPDs) were extremely versatile amphibious ships and provided sterling service with the Royal Navy to the end of the nineties, with Fearless remaining in service until 2001.

Launched: |

19 December 1962 |

Commissioned: |

25 November 1965 |

Displacement: |

12,120 tonnes |

Length: |

160m |

Propulsion: |

2 English Electric 2 shaft geared steam turbines |

Armament: |

2 BMARC GAM B01 20mm single mounted guns, |

Complement: |

580 |

No. in class: |

2: Fearless and Intrepid |

The Six-Day War, 23 May – 10 June 1967 Earlier in April 1967 Israeli troops and aircraft clashed with Syrian forces close to their northern border. Then in May, Egyptian troops moved into the Sinai and on 23 May announced a blockade of the Straits of Tiran. It became clear to the Israelis that their neighbours were preparing to invade. UN forces were ordered out of the Sinai by Egypt, and Egypt, Syria and Israel then mobilised for war. On 1 June Jordan was persuaded to join Egypt and Syria and even accepted the deployment of Iraqi troops across her territory.

Although the Western powers had a policy of nonintervention, the UK took steps to prepare for any eventuality and even considered trying to force a passage through the Straits of Tiran to demonstrate the international right of law to transit the strait, but without immediate air cover planning was discontinued. The aircraft carrier Victorious, which was in the Mediterranean homeward bound for the UK, was held at Malta together with five frigates, four minesweepers and a submarine as the basis of a Western task force. At the same time the carrier Hermes, which was off Gan, was ordered west at full speed for Aden and the Red Sea. Hermes made a high-speed passage to Aden and there, together with four frigates, Nubian, Ashanti, Brighton and Leopard, and four minesweepers, formed the elements of an Eastern task force. Hermes started to work up her group straight away with a series of exercises conducted away from the port, which, with its large Arab population, was increasingly hostile to Western forces.

At dawn on 5 June Israel launched all-out pre-emptive air strikes against Egypt, Syria and Jordan, striking initially to cripple their air forces on the ground. Having achieved air superiority these attacks were followed up with further strikes against secondary targets, preparing the ground for swift advances by armoured columns and mechanised infantry.

Victorious and Hermes off Aden

(NN)

The Israeli Navy was already at sea and attacked Port Said and Alexandria harbour on the night of 5 June. After a gun battle with Egyptian missile-armed Osa attack craft off Port Said, the Egyptian Navy was forced to withdraw, leaving the Israeli Navy to blockade Egypt and protect the northern flank. By bottling up the Egyptian Navy it prevented Egyptian Osa and Komar missile craft from launching strikes against Tel Aviv.

In the second phase of the war Israeli ground forces moved fast, penetrating enemy defences and pushing on deep into enemy territory. Within two days the Israelis had pushed Jordanian forces back to the East Bank, taken over the Gaza Strip and captured all the key passes in the Sinai. After a further two days of hard fighting in the south-west the Israelis overran the whole of Sinai and reached the Suez Canal, whilst in the north they took the strategically vital Golan Heights.

Demonstration of naval air power over Aden

(JAR)

On 10 June a cease-fire was declared and the war was halted, with the Israelis occupying the Sinai Peninsula, the whole of the west bank of the Jordan and the Golan Heights. It was an enormous humiliation for Egypt and the Arab nations, which indulged in many recriminations including the belief that the British had assisted the Israelis with their key air strikes in the opening phases of the war. Questions were raised in Parliament about the involvement of the British aircraft carriers and the aircraft of the Fleet Air Arm. The Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, had to explain where the carriers were and deny any involvement of the Royal Navy in the war.18

One important consequence of the war was the closure of the Suez Canal, which was to have a considerable effect on ships travelling to and from the Middle and Far East.

With the cease-fire holding, it was considered safe to disperse the two task forces, and Hermes was released to return east to Singapore, via Gan. Similarly Victorious was permitted to continue with her homeward passage from Malta to the UK.

Incidents continued after the cease-fire, however, and on 12 July the Israeli destroyer Eilat, together with Israeli fast attack craft, engaged Egyptian attack craft at sea off the northern coast of Sinai and sank two. The Soviet Navy, just fifteen miles away to the north, closely monitored the engagement. Three months later, on 21 October, the Egyptian Navy retaliated, firing Soviet-made Styx missiles from attack craft sheltering inside Alexandria harbour, and sank the Eilat.

Hong Kong, May–October 1967 In the Far East, the Cultural Revolution in China in 1967 had a dramatic effect in the region, with thousands fleeing from China. It thus put pressure on Hong Kong, and when serious riots broke out in the colony in May it became necessary to reinforce the garrison. The commando carrier Bulwark, with 40 Commando Royal Marines embarked, and a frigate were immediately sent to Hong Kong. The Royal Marines carried out a high-profile rapid landing by helicopter in the New Territories, which served as a powerful demonstration. The Royal Marines then stood by to restore order until the tension eased at the beginning of June, and on 12 June the Royal Marines were withdrawn.

Rioting broke out again the following month and problems were experienced on the border where the frontier guards were attacked. The police on the border had to be replaced by troops, and again it became necessary to reinforce the garrison. This time the carrier Hermes was ordered to Hong Kong. She arrived in early August and assisted the Royal Hong Kong Police, deploying them by helicopters in successful anti-Communist raids. At one stage it had been discovered that heavily armed Communists had established bases on the rooftops of blocks of flats and tall buildings. The helicopters of 826 NAS were able to deploy units of the Royal Hong Kong Police supported by British troops in a series of daring rooftop raids. The raids were entirely successful and resulted in many arrests as well as the recovery of considerable quantities of arms and ammunition.

In October 1967 the 8th Minesweeping Squadron handed over responsibility for guardship duties to the 6th Mine-sweeping Squadron, which was on regular deployments from Singapore. The minesweeper Fiskerton left Hong Kong that month, en route for the UK to pay off, and Woolaston and Wilkieston left the station shortly afterwards. In September 1965 five specially converted minehunters formed the Hong Kong Squadron.

Nigerian Civil War, June 1967 Onwards The commando carrier Albion, with 41 Commando embarked, sailed from Devonport on 31 May and headed south at speed. Her mission was to protect and evacuate, if necessary, British nationals from Nigeria, which was ravaged by civil war. A short while later four RFA support ships sailed to assist the commando carrier. Albion arrived in the Gulf of Guinea and closed the Nigerian coast on 9 June. The RFA support ships arrived eight days later. The Task Force operated off the coast in protection of British nationals for three weeks. Albion then departed from the area on 23 June, arriving back in Devonport on 5 July. RFA support ships remained in the area for a further week before being withdrawn.

Hermes off Aden

(NN)

The commando carrier Albion off Aden

(NN)

The Evacuation of Aden: Operation Magister (Task Force 318), 11 October 1967 – 25 January 1968

Terrorist attacks and civil disturbances continued in Aden in 1967 and the situation rapidly deteriorated as British forces were steadily pulled back to a series of defence lines. As they slowly withdrew heavy fighting for control broke out in the abandoned areas. By 24 September all British forces were withdrawn behind a Victorian defence works just to the north of RAF Khormaksar, known as the ‘Scrubber Line’. It was decided to bring forward the date of evacuation from Aden to the end of November 1967. The detailed planning for the formation of Task Force 318 for Operation Magister, to cover the final stages of the withdrawal, was speeded up and the ships began to assemble off Aden at the beginning of October 1967. It was to be a very powerful force, including four aircraft carriers and two assault ships, commanded by Rear Admiral Edward Ashmore.

The carrier Eagle on her way to Aden

(NN)

The commando carrier Albion had departed from the UK on 7 September and after participating in Operation Last Fling with 41 Commando steamed south. She rounded the Cape and after a five-day visit to Durban headed north to Aden, arriving on 12 October. As soon as Albion anchored in Aden air staff from 78 Squadron RAF, based at Khormaksar, commenced briefing 848 NAS on joint RN-RAF security operations. The Wessex helicopters were landed ashore and after being fitted with armour plating and GPMGs (general purpose machine guns) started patrols controlled by the operations cell at Khormaksar.

On 23 October the aircraft carrier Eagle, with 820 NAS embarked, sailed from Singapore, bound for Aden. After working up her aircraft in the Malacca Strait she steamed west across the Indian Ocean and joined the Task Force off the coast of Aden at the beginning of November. With the arrival of Eagle, eight RAF Wessex 2 helicopters were transported on board the assault ship Fearless to Sharga. As the last fighter aircraft of the RAF left their base at Khormaksar, on 7 November, responsibility for area air defence was taken over by Eagle. Her Buccaneers and Sea Vixens flew air patrols whilst, with her 984 radar, she provided early warning as well as co-ordination and control of all air operations.

As a powerful demonstration of force the twenty-four ships of Task Force 318, including the new assault ships Fearless and Intrepid, were formed in four lines, just off the entrance to Aden harbour, on 25 November. After a seventeen-gun salute, the Task Force was formally reviewed by Sir Humphrey Trevelyan, the Governor of Aden, embarked on board the minesweeper Appleton.

On completion of the review twenty-four helicopters from 848 and 820 NAS formed up and conducted a fly-past. The helicopter squadrons were followed by the fixed-wing aircraft, Buccaneers, Sea Vixens and Gannets, flying overhead in a final show of power.

The task of evacuating British forces began at dawn on 26 November in three phases. Crater City, Steamer Point and Ma’alla were quickly evacuated whilst a huge airlift was under way. The garrison was evacuated in an orderly manner, with 45 Commando being the last of the garrison to be pulled out. 45 Commando were not, however, the last British forces to leave Aden, as Royal Marines from 42 Commando had been landed from Albion to help cover the final withdrawal phase. So on 28 November at 1500 the last units of 42 Commando Royal Marines were lifted off by helicopter and flown out to Albion, thus gaining the distinction of being the very last British forces to leave Aden.

The Task Force remained just off Aden until midnight, when independence was officially recognised, and then began to disperse, with Eagle heading east for Singapore. On 7 December the commando carrier Bulwark arrived to relieve her sister ship Albion, and three days later Bulwark, escorted by Devonshire and Barrosa, sailed north-east for Masirah. A small naval task force remained in the area for several months to provide cover for the British nationals still employed in the BP oil refinery at Little Aden and for the British Embassy staff.

Bulwark with RFA Tidereach and the destroyer Barrosa

(RNM)

The powerful Task Force formed in the Arabian Sea, including the carriers Eagle and Albion

(NN)

HM Ships and Royal Marine Units Engaged in the Aden Evacuation

Aircraft carriers: |

Eagle and Hermes |

Commando carriers: |

Albion and Bulwark |

Assault ships: |

Fearless (responsible for co-ordinating the withdrawal operation) and Intrepid |

Guided missile destroyers: |

London and Devonshire |

Submarine: |

Auriga |

Destroyer: |

Barrosa |

Frigates: |

Ajax, Phoebe and Minerva |

Minesweeper |

Appleton |

RFA support ships: |

Dewdale, Appleleaf, Olna, Retainer, Stromness, Reliant, Resurgent, Fort Sandusky, Tidespring and Tideflow |

Landing ship (logistic): |

Sir Galahad |

The commando carrier Bulwark in the Far East

(CC)

In 1967 there were over 3,000 terrorist incidents in Aden; fifty-seven British servicemen were killed and 325 wounded. There were also over a hundred British civilian casualties, eighteen of them fatal.19.

Aden, which had been a British colony for 128 years, was bankrupted by Britain’s withdrawal and the closure of the Suez Canal. After the British left, it became a breeding ground for terrorists and also, for a time, a base for the Soviet Navy. Much later an Al-Qaeda cell was to be established in Aden, and this attacked Western shipping including the destroyer USS Cole, which was severely damaged with many casualties.

In February 1968 political trials were held in Aden, and government officials who had been pro-British were put on trial. In view of the situation Bulwark, with 40 Commando embarked, was deployed to the area on 14 February, escorted by the frigates Llandaff and Eskimo, as a standby force. The ships were withdrawn on 20 March. The following month, however, another standby force was required during acrimonious finance talks with the Aden government over the sensitive subject of financial compensation. At the beginning of April the aircraft carrier Eagle, exercising with the US Navy off Subic Bay, was ordered west at speed to form a naval task force secretly in the Arabian Sea. Albion, with 40 Commando embarked, together with supporting frigates and RFA vessels, joined the Task Force, which remained within close range of Aden until 28 May. Eagle was then released to return to UK via Cape Town, as the Suez Canal remained closed.

Gibraltar, 13 October 1967 Onwards Continuous harassment by the Spanish government increased the pressure on Gibraltar. Tactics included closings and restrictions on movements across the border and anchoring Spanish warships in Gibraltar waters. The Spanish had closed the border on 3 February 1965 and maintained a limited blockade ever since. In 1967 a Spanish minesweeper sailed into the bay and refused to leave territorial waters when ordered to do so by the guardship, the frigate Grenville. Eventually, after considerable pressure had been applied, the sweeper was escorted out of the bay. To reassure the people of Gibraltar it was decided to deploy a permanent guardship, and on 13 October 1967 the frigate Brighton arrived to start the first tour of duty on station. A permanent guardship, reinforced from time to time, was to remain in Gibraltar waters for many years, right on into the next century.

Cyprus, 23 November – 2 December 1967 In September 1967, Greek terrorists of EOKA (Ethniki Organosis Kuprion Agoniston) incited violence against Turks in Cyprus, and in an attack against a Turkish village twenty-seven Turks were slaughtered. Turkey then announced its intention to invade Cyprus. On 23 November the minesweepers Walkerton, Leverton, Shavington and Stubbington, supported by Layburn, were deployed from Malta to Cyprus as a standby force to cover immediate emergencies. In the event the Turks were dissuaded from intervening by President Johnson of America, who threatened to expel Turkey from NATO if the invasion took place. President Johnson also insisted that Greek troops be withdrawn from the island and 10,000 were evacuated. The situation eased and the Royal Navy ships returned to Malta on 2 December.

Persian Gulf At the end of March 1968 Iran threatened to invade and occupy the Tunb Islands in the Persian Gulf. On 29 March the assault ship Intrepid and the frigate Tartar, acting as escort, steamed to the islands and spent two days sailing in close proximity, which served as sufficient deterrent to protect the islands from invasion.

Philippines, September 1968 In September 1968, when the Philippine government refused ships the right of innocent passage, the Far East Fleet formed a task group to provide a powerful show of force. The group assembled on 23 September and consisted of the carriers Hermes and Albion, the converted maintenance carrier Triumph, the assault ship Intrepid and the guided missile destroyers Glamorgan and Fife, escorted by four frigates and destroyers. The Task Group then passed through the Sulu Sea, without any interference at all, and dispersed on 24 September.

Anguilla: Operation Sheepskin, 14 March – 5 May 1969 Severe political problems and civil disturbances broke out in Anguilla following its break away from St Kitts-Nevis in March 1969. The frigates Minerva, Rothesay and Rhyl were deployed to the island on 14 March on Operation Sheepskin to restore sovereignty and order. Paratroops, RAF units and civil police assisted the Task Force. Operation Sheepskin was maintained until order was completely restored by 5 May.

Northern Ireland: Operation Banner, 14 August 1969 Onwards

The bitter ‘troubles’ in Ireland and Northern Ireland had endured for hundreds of years and had been a constant intractable problem for the UK. After partition between the Irish Free State and Ulster (Northern Ireland) in 1921, hatred and hostility continued, and ultimately in 1969 serious civil disorder was triggered by Catholic civil rights marches. The marches provoked violent clashes with the largely Protestant authorities, police and ‘B Specials’ (auxiliary police).

On 12 August 1969 the Battle of the Bogside was fought in Londonderry when riots broke out at a parade of Orange Apprentice Boys. This was followed by violent street fighting and rioting in Belfast as well. Two days later it became necessary for the armed forces of the UK to intervene to restore law and order, and two battalions of infantry were sent in as an ‘aid to civil power’. The following month the British army started to erect the ‘peace wall’ between the Falls Road and the Shankill Road in Belfast. On 28 September, 41 Commando Royal Marines, as ‘Spearhead Battalion’ (the duty battalion on standby to deploy anywhere in the world at immediate notice), was deployed to the Divis Street area of Belfast on internal security duties; it was to remain there until 10 November.

Intelligence reports indicated that arms were being smuggled into Northern Ireland by the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), and the GOC NI (General Officer Commanding, Northern Ireland) requested assistance from the Royal Navy. He asked for anti-smuggling patrols to be conducted off the coast of Northern Ireland to intercept arms shipments. The Ton class minesweepers Kellington, Wasperton and Wotton carried out a series of patrols from 25 to 29 October, from 30 October to 17 November and from 17 to 24 November. In addition the Ton class minesweeper Kedleston, which was engaged on fishery protection duties, was put on standby from 11 to 28 December.

FLEET REVIEWS

The NATO Review off Spithead, 16 May 1969 On Friday 16 May 1969 a fleet review was held off Spithead to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of NATO. At 1200 the Royal Yacht Britannia, preceded by the Trinity House vessel Patricia, sailed from Portsmouth harbour and headed out to Spithead. HM the Queen, accompanied by HRH the Duke of Edinburgh, the Secretary General of NATO, Signor Manlio Brosio, Admiral of the Fleet Earl Mountbatten of Burma, NATO representatives and other dignitaries, were embarked on board the Royal Yacht. The Royal Navy was represented by fifteen ships, though the aircraft carrier Eagle, in Portsmouth at the time, did not take part in the review. The Commander in Chief Western Fleet (also NATO Commander in Chief Channel, or CINCHAN), Admiral Sir John Bush, flew his flag in the guided missile destroyer Glamorgan.

British Warships Present at the NATO Review

Helicopter cruiser: |

Blake |

Guided missile destroyer: |

Glamorgan |

Frigates: |

Dido, Phoebe, Eastbourne, Puma, Wakeful, Tenby and Torquay |

Submarines: |

Tiptoe and Olympus |

Ships: |

Shoulton, Alcide and Letterston |

At 1210 the NATO ships at Spithead fired a royal salute. Then, following a reception, the reviewing ships sailed up and down the lines of sixty-three NATO ships from eleven countries. The following day the NATO ships were open to the public in Portsmouth dockyard.

HM Ships and Royal Marine Units Engaged at the Start of Operation Banner

Minesweepers Kellington, Wasperton, Wotton and Kedleston 41 Commando Royal Marines

Royal Review of the Western Fleet, 29 July 1969 Two months later a further review was held in Torbay. This was the Royal Review of the Western Fleet on 29 July, with HM the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh embarked on board the Royal Yacht Britannia.

It was a cloudy day with strong winds blowing when the fleet put to sea, led by Eagle flying the flag of the Commander in Chief, Admiral Sir John Bush. First there was a fly-past of ninety Fleet Air Arm aircraft, and that was followed by an impressive steam-past of two columns of over forty warships, submarines and RFA support ships. Earlier in the day the Queen had presented new colours to the fleet on board Eagle.

OTHER DUTIES

Quelling a Mutiny On 15 January 1966 a mutiny broke out on board the British ship SS Sudbury Hill in the Gulf of Aden. The Leander frigate Dido, on her way back from Indonesian waters, was quickly on the spot and an armed boarding party was put on board the cargo ship. The mutiny was quelled with no serious casualties.

Aberfan Disaster On 21 October 1966 a disaster occurred in South Wales when a slagheap collapsed, engulfing the small mining town of Aberfan and killing 144 people. The cruiser Tiger, flying the flag of Admiral Pollock (Flag Officer Second in Command, Home Fleet), arrived in Cardiff the next day and 380 of the ship’s company were immediately landed to assist in the search for survivors and carry out emergency disaster relief work.

East Malaysia In January 1967 east Malaysia suffered severe flooding and Bulwark, en route to Singapore from Hong Kong, was diverted to provide emergency aid. The commando carrier arrived on 8 January and was able to carry out essential relief work, restoring basic services.

Tasmania At the beginning of February 1967 Tasmania was devastated by bush fires. The submarines Tabard and Trump were in New Zealand at the time, and they immediately sailed on 7 February for Tasmania, where they landed working parties, which provided much valuable relief work ashore. The submarines were withdrawn on 15 February.

Operation ‘Mop Up’: The Torrey Canyon Disaster On 18 March 1967 the tanker Torrey Canyon ran on to rocks off the coast of Cornwall and started to spill vast quantities of crude oil. The destroyer Barrosa and the minesweeper Clarbeston, at Plymouth, were immediately sailed with large quantities of detergent on board, which they used on the spreading oil slick. Gradually more ships arrived to assist, including the destroyer Delight. Eventually on 30 March it was decided to bomb the stricken tanker, and naval Buccaneer aircraft were used, with aircraft from 800, 809, 890 and 899 NAS taking part.

The Essberger Chemist On 24 June 1967 the submarine Dreadnought was ordered to sink the 13,000-ton German tanker Essberger Chemist, which was a hazard to shipping off the Azores. Dreadnought, commanded by Commander Peter Cobb, had sailed from Gibraltar at thirty knots, and when she arrived in the area fired four torpedoes. Three torpedoes struck the stricken vessel, though eventually she had to be finished off by gunfire from the frigate Salisbury.

Sicilian Earthquake An earthquake occurred in north-west Sicily on 15 January 1968, and the minesweepers Walkerton, Stubbington, Crofton and Ashton immediately sailed from Malta to render emergency assistance. The ships provided valuable relief work over the course of five days before returning to Malta on 21 January.

SHIPS, SUBMARINES, AIRCRAFT AND WEAPONS

Nuclear-Powered Ballistic Missile Submarines Britain’s first SSBN, the 8,000-ton Resolution, was launched on 15 September 1966 and commissioned one year later in October 1967. She fired her first Polaris test missile at Cape Canaveral (Cape Kennedy) on 15 February 1968 and was deployed on her first deterrent patrol in June. She was built on time and to budget, which, for a project of such magnitude and immense complexity, was an incredible achievement. Together with her sister SSBNs, Repulse, Renown and Revenge, she maintained deterrent patrols until finally handing over to the next generation Trident SSBNs in 1995.

The Swiftsure Class Submarines By 1969 there was, effectively, a nuclear submarine arms race between the Western Powers and the Soviet bloc. The submarine design bureaus and their associated yards in the Soviet Union were turning out nuclear submarine classes at an alarming rate. Soviet technology was evolving and was fast matching the advantages the West had, greatly assisted by espionage. Technology stolen from the West was being incorporated into the designs in the Soviet Union. Against this backdrop a new class of submarine, the Swiftsure class, was procured, and whilst it was a follow-on from the Valiant class it marked a step change in design and stealth underwater, providing greater speed, a quieter platform and greater diving depths. Displacing 5,000 tons, it incorporated a change in hull shape with a more streamlined design. Its sonar was very advanced, providing greater detection ranges and giving a true range advantage on the enemy. Its weapon outfit had also developed: armed initially with the Tigerfish homing torpedo the submarines were also fitted with the Royal Navy Sub-Harpoon (a sub-surface-to-surface anti-ship missile) and, latterly, the Spearfish torpedo (the successor to the Tigerfish) and the Tomahawk cruise missile. Six were ordered, and one, Sceptre, remained in service in 2008.

Swiftsure class SSN

(NN)

Gas Turbine Engines The Royal Navy had spent over twenty years researching into gas propulsion for warships. As an experiment the Type 14 Blackwood class frigate Exmouth was converted to gas turbine power with a Rolls Royce Olympus engine for full power and two Rolls Royce Proteus engines for cruising. She began sea trials in 1968 and was the first major NATO warship to be propelled by gas turbine engines. The Soviet Navy had launched the first all-gas turbine major warship in the world with the Kashin class destroyers, launched in 1962.

Phantom Fighters for the Fleet Air Arm Despite the decision to phase out the carriers and naval fixed-wing aircraft, procurement of the US-built McDonnell Douglas F-4K Phantom II naval fighters, ordered in 1964, continued. The original order of fifty for the Royal Navy was cut back to twenty-eight. Phantoms were also ordered for the RAF. A Flying Trials Unit was formed at RNAS (Royal Naval Air Station) Yeovilton in May 1968, and one year later the navy won the Daily Mail trans-Atlantic Air Race with a flight of three Phantoms.

A Royal Navy Phantom fighter by LA Wilcox (LW) (RC)

(DD)

ASW The development of ASW sensors, weapons and tactics remained a high priority for the Royal Navy throughout the sixties. As well as submarines being used in the ASW hunter – killer role and ship-borne ASW helicopters, surface ships were improving their ASW weapons and sensors. Considerable advances in submarine detection and prosecution ranges were achieved by the introduction of the VDS (variable depth sonar) and Ikara ASW missile. Sonars mounted on the hulls of ships had many limitations owing to hull water noise and the warmer surface layers of the sea, which could cause sonar beams to be refracted or reflected, allowing submarines to avoid detection. The Canadians pioneered the use of a VDS, which could be towed astern of a ship and be lowered beneath the warm surface layer of the sea to detect submarines hiding in colder layers below. The Australians then developed the ship-launched rocket-propelled Ikara ASW missile, which could be guided to the approximate position of a submarine. On entering the water Ikara homed in on the target submarine. The Ikara ASW system was to be fitted to the Leander class frigates from the beginning of the seventies.

PERSONNEL MATTERS

In 1965 the strength of the Royal Navy stood at 97,000, and by the end of 1969 that had reduced by 9,500 to 87,500. The five-year period was dominated by the devastating decision cancelling the new generation of aircraft carriers. It was a severe blow, and cast doubts over the long-term future of the Service and caused many to wonder whether they should perhaps consider a career outside the Navy.

Leander Class Frigate

Leander was the lead ship of the most successful frigates to serve with the modern Royal Navy. The Leanders were developed from the basic hull form of the earlier Rothesay class frigates, which were highly manoeuvrable at speed with excellent sea-keeping qualities. They had high bows that kept them relatively dry in heavy weather, and they provided a very stable platform for modern sensors and weapon systems. The numbers built and the long period of time for which they remained in service were testimony to their success.

Launched: |

28 June 1961 |

Commissioned: |

27 March 1963 |

Displacement: |

2,860 tonnes |

Length: |

113.38m |

Propulsion: |

2 boilers, 2 steam turbines on 2 shafts |

Armament: |

1 twin 4.5in gun (later replaced by Ikara ASW missile launcher), |

Complement: |

257 |

No. in class: |

26 |

The White Ensign Association Throughout the period the White Ensign Association continued to provide valuable advice and guidance to the large numbers that were still leaving the Service. The Association was also building up its many useful networking contacts, extending the areas where it was able to offer help and finding more job opportunities. It also provided key investment advice and arranged mortgages for the increasing numbers of men who wished to purchase property using their lump sums as a deposit.

Home Ownership The idea of house purchase was starting to spread in the Navy, and more and more of those serving were turning to the Association to arrange mortgages. The incidence of home ownership in the Royal Navy was to be much greater than in the other two services and was to provide a number of significant advantages. Firstly it provided a wise capital investment, and secondly it invested money which otherwise would have been spent and sunk on rent. Thirdly it provided an element of stability for the married family whilst the husband was away at sea, and finally it meant that a man already had a home when he came to leave the Service.

The frigate Rothesay

(RNM)