Beginning in the mid-eighteenth century, European scientists struggled to keep pace with the work of classifying organisms brought back in great batches from overseas expansionary expeditions. The world’s biological expanse and richness rapidly became apparent. Nevertheless, placement of this cornucopia of new species appeared mostly in dry tables and lists that only barely touched the overarching idea of organic organization let alone how it originated, except by resorting to God’s creative powers.

Especially the first half of the nineteenth century saw a hodgepodge of competing ways to illustrate and organize nature’s order, and as we now know, the tree won out in the end, but that was not preordained; rather, the influence of powerful individuals led to the supremacy of the tree as the prominent visual metaphor. Certainly, some illustrative metaphors were better than others for capturing nature’s order—the tree, to be specific—but others were possible; some simply collapsed because of their contrived perceptions of the natural world. It nevertheless is worthwhile to sample the diversity of these perceptions.

Tables, Hierarchies, and All Manner of Other Geometries

Nothing preordained that tree imagery would triumph as the visual metaphor for nature’s order. Indeed, the ladder of life, in its inaccurate simplicity and because of its historical baggage, still stubbornly persists. In the late eighteenth and earlier part of the nineteenth centuries, all manner of devices appeared in an attempt to simultaneously understand the richness and the obvious order in nature. Some of the schemes certainly wished to fathom the mind of God; increasingly, though, they stood on their own right.

These schemes ran from simple tables listing plant and animal names, to hierarchically organized tables and figures with progressively more exclusive groupings, to elaborate geometric shapes purporting to show some underlying mathematical principle in biology. Such schemes survive and thrive in the form of tabular classifications and dichotomous keys used by befuddled students and nature lovers alike to identify species. Who has not at least thumbed through a bird guide or looked through a key to local flowers based on their color? Some of the earlier tables and hierarchies require some comment, but they seldom rise to the level of visual impact that we associate with trees or ladders of life. I mention only the more visually appealing and scientifically important among the older examples.

Although not the first, Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) rightfully occupies the position of most influential arranger of plants and animals, in large measure because of his binomial system of naming species whereby a plant or an animal receives both a more inclusive generic name (for example, Felis) and a specific or trivial name (for example, catus), such as the domestic cat (Felis catus). Linnaeus did not discover this arrangement but applied it and in so doing helped bring stability to the chaotic naming of species and higher taxa. Linnaeus left no indication of evolutionary ideas, yet his classification is possible because of evolution. With the advent of newer views of classificatory schemes and the explosion of molecular technology, a strict Linnaean system is increasingly under fire. Suffice it to note here that however well his ideas have fared, he remains the place of beginning for modern classification.

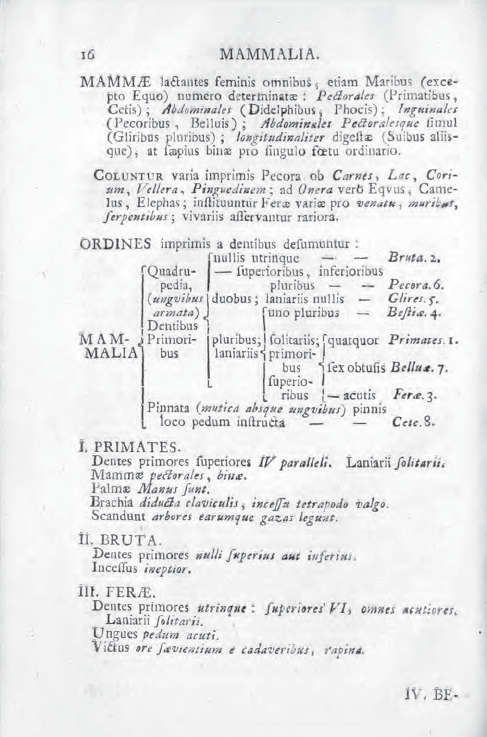

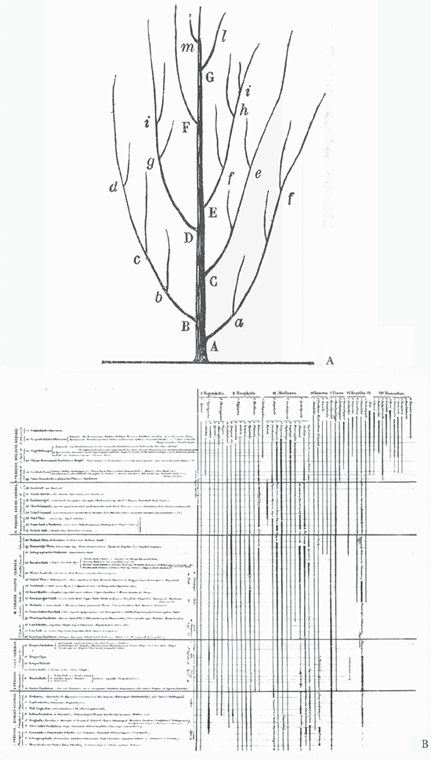

FIGURE 3.1 Carl Linnaeus’s hierarchical key of Mammalia, from Systema naturæ (1758).

Linnaeus wrote twelve editions of his classification Systema naturæ beginning in 1735, but the tenth edition (1758) by agreement serves as the starting place for all later zoological classification. As a simple example of a hierarchical key, figure 3.1 comes from Linnaeus (1758). The key in the middle of the page starts with the more inclusive Mammalia on the left, providing more and more exclusive characters of posture, teeth, and so forth until the individual orders are reached on the right, with the correct page number as to where they may be found in the volume. The top of the page details characters of the mammary glands found in mammals, and the bottom lists features found in three of the orders that Linnaeus recognized. Classificatory keys and hierarchies appear relatively often by the late eighteenth century, but some are as much as two hundred years older, such as a bifurcating key from 1592 for species of hyacinths illustrated by Mark Ragan (2009).

Eloquent but Contrived Geometries

The nineteenth century presented some of the most interesting quackery found in any century—spiritualism and phrenology are two of the best examples. Lest we think that these were fringe practices, recall that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Alfred Russel Wallace were spiritualists and that Queen Victoria and Prince Albert invited the notorious George Combe to perform phrenological readings of their children’s heads. This is the same century in which the scientific method truly began to emerge as a way of exploring the physical world, but this also meant that rather unusual (to put it mildly) hypotheses emerged on how to visualize and organize the natural world.

In 1766, Peter Simon Pallas not only suggested trees and networks for organizing life but also mentioned polyhedrons as possible representations of nature, and in fact fifty years later a rather bewildering diversity of polyhedric representations of nature emerged (Ragan 2009). The best-known, and in England the most widely accepted, version was quinarianism. The basic thesis was that there were cycles within cycles centering on groups of five. The English ornithologist William John Swainson (1789–1855) helped popularize the system (O’Hara 1991). Swainson credited quinarianism’s rise in the early nineteenth century to German-born Russian invertebrate biologist Gotthelf Fischer von Waldheim (1771–1853), who in 1805 arrayed animals in a series of contiguous circles with man at the center (Ragan 2009).

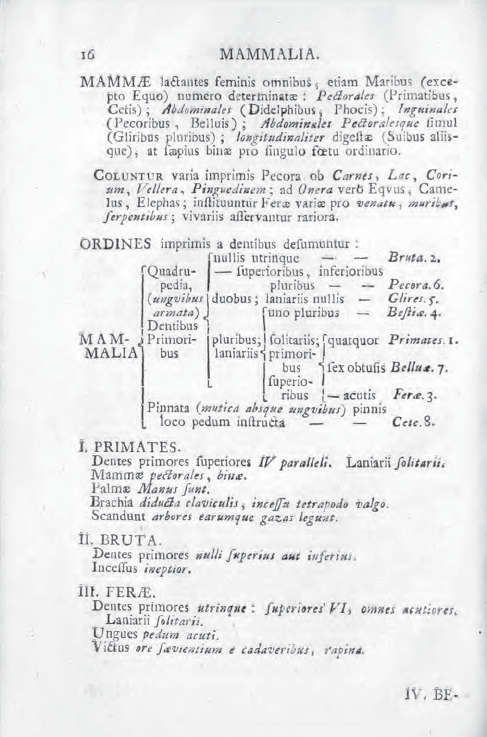

William Sharp Macleay (1792–1865) was the person most responsible for the rise of quinarianism. A Cambridge University–trained Australian amateur entomologist and son of the entomologist Alexander Macleay, William Macleay believed that he had uncovered a five-part division of all animals that he termed the Acrita, Radiata, Annulosa, Vertebrata, and Mollusca (figure 3.2). Recall that Georges Cuvier, whom Macleay met, had recognized four branches of animals. But unlike Cuvier’s system, Macleay claimed that each of the five groups was divisible into five lesser groups, such as Pisces, Amphibia, Reptilia, Aves, and Mammalia within Vertebrata. Macleay was thus claiming something innate about divisions of five in the natural world.

On the same page that his diagram of the five groups appears, Macleay (1819) writes, in reference to various groups of animals: “The foregoing observations I am well aware must be far from accurate; but they are sufficient to prove that there are five great circular groups in the animal kingdom which possess each a peculiar structure, and that these, when connected by means of five smaller osculant groups, compose the whole province of Zoology” (318). By “osculant groups,” he meant intermediary forms. For example, Cephalopoda linked Vertebrata and Mollusca, and the platypus linked mammals and birds (Oldroyd 2001). If five members of some grouping could not be found, it meant that the missing members remained to be recovered, such as the case for the asterisks in Mollusca in figure 3.2.

FIGURE 3.2 William Macleay’s quinarian, or five-part, division of all animals, from Horae Entomologicae (1819).

The quinarian system represented an interesting, if misguided, attempt to recover and visually represent the relationships of groups of species, and it was ahead of its time in trying to ascertain what might be missing in terms of undiscovered groups of species. The latter idea resurfaced in more recent time with a “ghost lineage,” which predicts the presence of its nearest relative in the fossil record (Norell 1992) by comparing what is known of the earliest fossil record of one lineage with what is not known of its nearest related lineage. Although a hypothesis, ghost lineages provide a basis for possible discovery, whereas such a premise in quinarianism does not and never did have any basis in biology. Thus, while testable, the idea of a five-part overarching basis for nature was a contrived hypothesis even in its day and soon collapsed of its own internal inconsistencies.

The quinarian system was adopted by various researchers, mostly British, in the first half of the nineteenth century, but it became increasingly cumbersome and complex, going from five to seven and then to ten cycles, and as Ragan (2009) notes, “these systems began a terminal slide into disfavor” (13). Nonetheless, the system appeared in various well-known, mostly popular texts in the first half of the nineteenth century, notably as a chapter in the evolutionist Robert Chambers’s (1802–1871) anonymously published Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844) and in the creationist Hugh Miller’s (1802–1856) Testimony of the Rocks (1857). It even survived in a few places after the publication of On the Origin of Species in 1859; William Hincks, a professor of natural history at the University of Toronto who had been chosen for his position over a bright, young Thomas Henry Huxley, was teaching the quinarian system as late as 1870 (Coggon 2002).

Dawning of the Biological Tree Motif

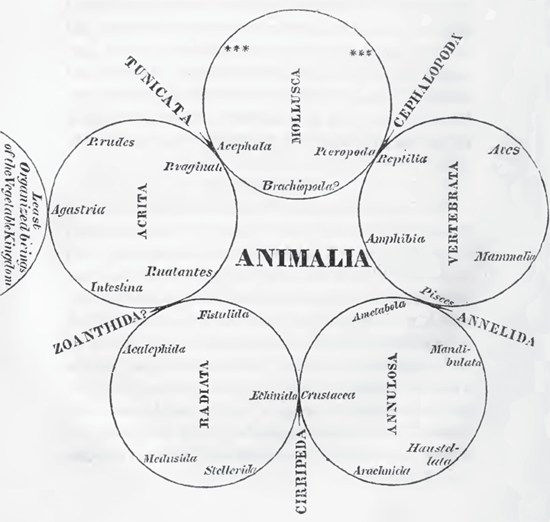

Pallas’s Elenchus zoophytorum (1766), which suggests that life be arranged in a tree-like form, traditionally marks the point in time when European savants first put forward that idea. Pallas never produced such a tree figure, at least of which we are aware, but sixty-three years later a figure produced by Carl Edward von Eichwald (1795–1876) in Zoologia specialis (1829) purports to depict Pallas’s tree (Ragan 2009). Ragan claims that according to a Russian source, S. R. Mikulinskii (1972), Eichwald’s diagram shows Pallas’s tree. In fact, although Mikulinskii notes the works both of Pallas and of Eichwald in the same paragraph (Chesnova 1972:344), she presents no evidence that Eichwald intended his tree to be a visual version of Pallas’s ideas. Nonetheless, Ragan’s close reading of Pallas shows the considerable similarity of Pallas’s description of a tree and Eichwald’s figure of one. According to Ragan, Pallas describes the trunk of his tree as a series of neighboring genera (or lineages) closely appressed one to another and with twigs thrusting from the trunk—exactly what Eichwald presents (figure 3.3). Eichwald (1829) does give credit to others for earlier uses of a tree metaphor when he writes (in Latin), “e) Long ago other authors constructed a nearly similar animal tree of life; foremost among whom must be numbered my very good friend F. S. Leuckart (v Zoologische Bruchstiicke, Helmstädt, Heft I., 1819, and the same Versuch Dying naturgemässen Eintheilung der Helminthen, Heidelberg, 1828), or A. F. Schweigger (v Naturgeschichte der skelettlosen, ungegliederten Thiere, p. 81)” (44). A search of these works uncovered only bracketing classifications but no trees similar to that of Eichwald.

Eichwald’s figure evokes a rather brooding feel, a darker Blakean view of the creation of life, showing what appears to be separate trunks closely joined into one, just as Pallas described. Roman numerals surmount eight of the larger branches, and Eichwald refers different groups of animals to each large branch. He titles this figure and the four and a half pages that follow “The Tree of Animal Life.” Eichwald (1829) describes in the first few sentences how “the first rudiments of animal life [come] from the mass of chaotic organic material” that we find in the ever-present warm water and repeatedly form from a “mucous membrane of globules of various primitive forms” (41). Some of Eichwald’s language suggests biological change, as in several places where he uses variations of the Latin word evolutio, but whether he meant anything like what we call biological evolution or only the older, preformationist sense of unrolling, as of an organism during its lifetime, remains murky. Still, Eichwald (1829:43) tempts us when we read that the highest branches of a tree, which overshadow the lower vertebrates, gradually evolve in a straight line, intricately making it up to the ascending human race, whom he then compares to spring flowers on the tree, and further that each step in the evolution of animals follows different ways, but then again he may simply mean evolution in the sense of unrolling (development) of an individual organism.

Whereas we may be tempted to read some evolutionary thoughts into Eichwald’s writings, the same cannot be said for Pallas. Nevertheless, Pallas not only argued for life to be represented as a tree but most specifically stated that life should not be connected in a series in a scale or ladder (Ragan 2009). Even though Pallas rejected the scala naturae, following Ragan’s interpretation, both Pallas’s and Eichwald’s ideas appear as a hybrid of a scala naturae and a tree that Ragan colorfully describes as a bunch of asparagus shoots rather than a tree.

FIGURE 3.3 Carl Edward von Eichwald’s tree of continuous change, from Zoologia specialis (1829).

Certainly Eichwald’s comments and figure, whether intended or not, suggest repeated spontaneous generations followed by change in closely aligned lineages, an idea that, as we will see shortly, was earlier advocated by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck. Although it cannot be said for Eichwald, nothing of evolution imbues the ideas of Pallas, yet it seems natural for us today to read such ideas into these early works. There is little doubt that before Pallas, others may have suggested similar ideas; they simply do not survive or remain unrecognized.

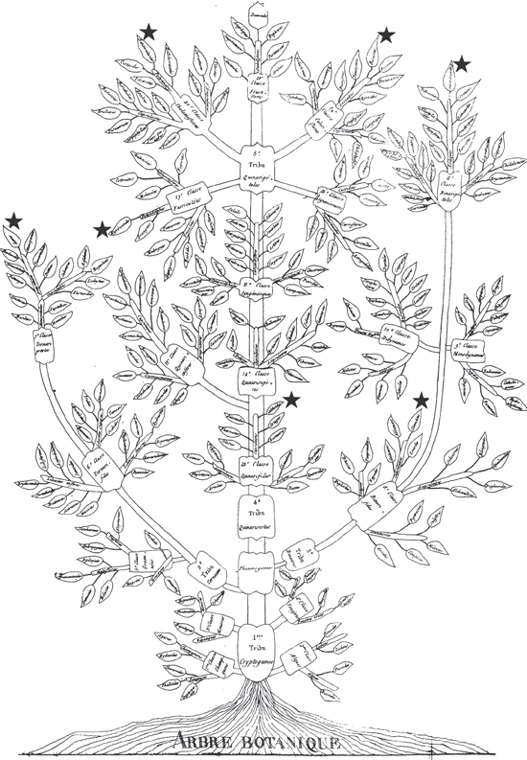

The first known tree presenting biological (but not evolutionary) relationships appeared in a paper written by an obscure French botanist, Augustin Augier (1801) from Lyon (figure 3.4). This work, however, did not go unreported at the time of its publication, at least by its publisher. In 1802, the inaugural annual issue of a catalog of books of seven book publishers (Fleischer 1802), including its Paris distributor Levrault frères, listed Augier’s work under its botanical section as item 59. Augier’s tree even merits a quaint description: “with botanical tree of large grape leaves, with its explanation” (quoted in Stevens 1983:267). As far as determinable, Augier’s tree influenced no later tree motifs and probably would not be known except for its fortuitous recognition and publication in 1983 by botanist Peter F. Stevens. This said, the publication in 1801 of such a tree shows that this motif was beginning to infiltrate scientists’ views on how to show nature’s order. According to Stevens, Augier was not a full-time botanist, certainly not a rarity at the time, but relied on better-known botanists of his era for his information. As Stevens’s translation shows, Augier specifies a creator rather than any acceptance of evolution to explain his tree.

Augier’s tree is reminiscent of Joachim of Fiore’s much older trees, but instead of religious personages gracing the medallions on Fiore’s tree, Augier provides medallions (the ersatz “grape leaves”) showing what he terms classes and tribes of plants, at least as recognized at that time and by him. At the base is the tribe “Cryptogames,” including fungi, mosses, algae, and ferns. Immediately above occurs the “Phanerogames,” including what we would today refer to as angiospermous and gymnospermous plants. Each of the numerous terminal leaves bears smaller groups of plants. The stars scattered around the tree denote families that show the relationship of analogy (Stevens 1983), meaning similarities not the result of being close relatives.

Even though Augier apparently rejected the notion of a scala naturae, his tree retains a scala naturae aspect in that he places what he perceives as more primitive plants nearer the base with more “perfect” forms set higher on the main trunk. Stevens’s (1983) translation shows this intent: “This method starts with the least perfect plants and by gradation leads to the more perfect, as one can convince oneself when reading the exposition of the method and the explanation of the botanic tree” (205). This dual representation continues well into the nineteenth century and beyond, even after evolution triumphed as the basis for such a tree-like form.

FIGURE 3.4 Augustin Augier’s “Tree of Trees,” from Essai d’une nouvelle Classification des Végétaux (1801). (Reproduced by permission of Taxon)

The Evolution of an Evolutionist and His Changing Visual Metaphors

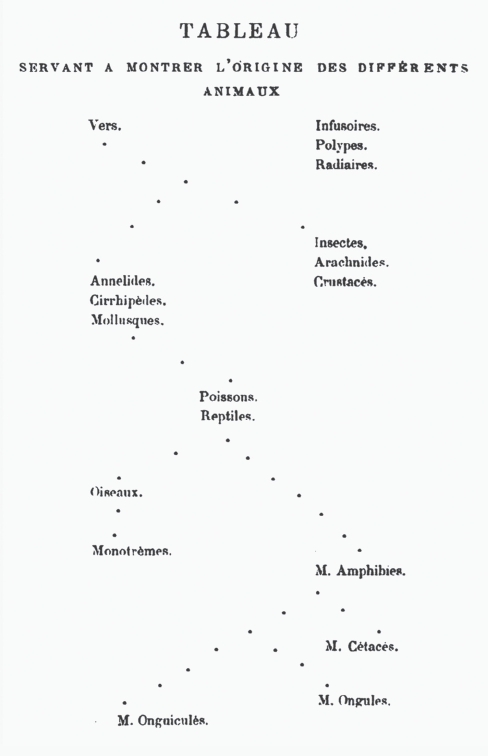

Within a short eight years after the publication of Augier’s (1801) rather picturesque tree, another, much less arborescent, inverted, but nonetheless branching diagram appeared, but for the first time evolution underpinned its form. Augier’s full-blown tree motif provides a stark contrast to Lamarck’s (1809) hesitant figure formed of widely spaced dots in a simple inverted bifurcating diagram (figure 3.5). As far as is known, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829) knew nothing of Augier’s tree, which seems somewhat odd as Lamarck began his career as a botanist who spoke and wrote French, as did Augier. By the time Lamarck published this figure in 1809, his views on how the evolutionary history of life unfolded had themselves evolved, somewhat remarkable for a scientist of almost sixty-five years of age.

At the age of only thirty-four, Lamarck fairly burst on the biological scene with the publication of his over 1,800-page, three-volume botanical work Flore françoise (1778), followed a year later by his rapid election to the French Academy of Sciences. He certainly received help from luminaries at the Jardin du Roi (Jardin des Plantes after the French Revolution) in Paris, which he readily admits in the introductory parts of this work, but he nevertheless begins here to show his own mind. The volumes present a series of mostly dichotomous keys and classifications of plants, quite different from the approach of Linnaeus (Packard 1901).

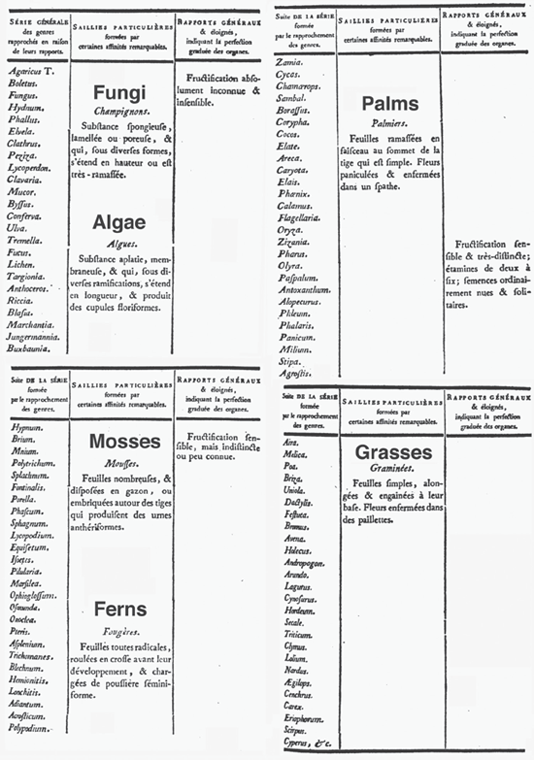

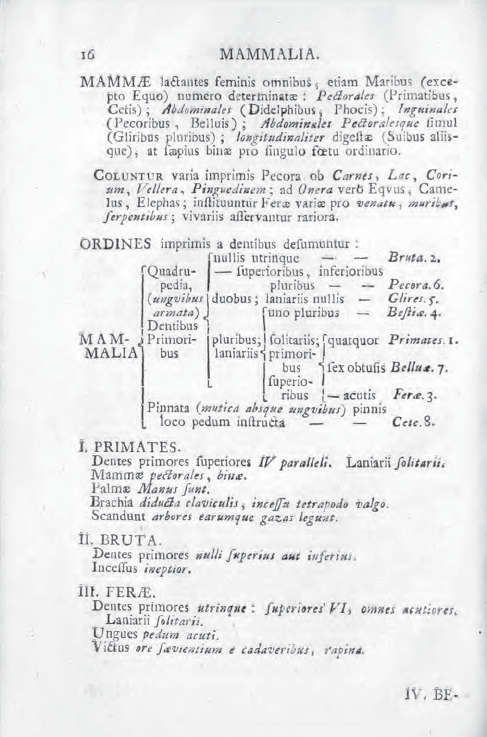

In the preliminaries of volume 1, Lamarck posits three problems dealing with how the succession of plants should begin and proceed, what rules provide these arrangements, and how to order such a succession for which there are no lines of demarcation to divide groups. Lamarck’s choice to deal with these problems, especially the last, comes in the form of a four-page table, which he says samples the natural order using exemplars. Figure 3.6 is a composite of the four pages and is read from the top-left down and then from top-right down. I am not aware of why Lamarck chose to progress these tables from top to bottom, but, as we will see, he does this for some later figures but not others, even though form and intent change.

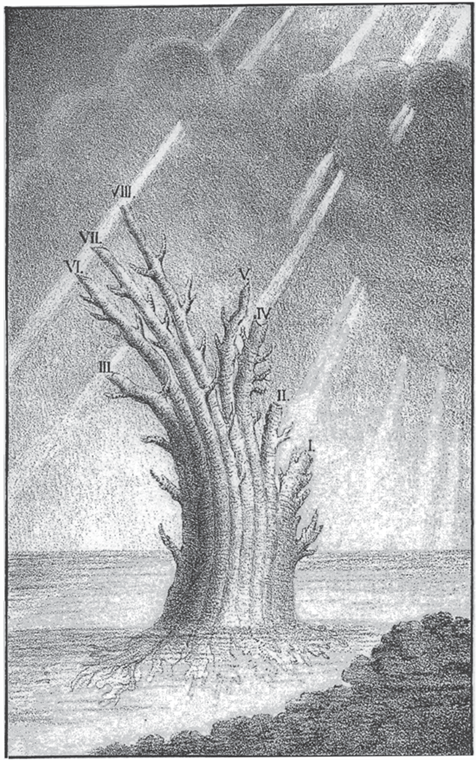

FIGURE 3.5 The first-known evolutionarily based tree, “serving to show the origin of the different animals,” from Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s Philosophie zoologique (1809).

The column headings from left to right indicate a series of closely related genera, the middle column notes specific saliences or characters derived as the result of notable affinities, and the right column refers to more distant, general relationships indicating the gradual perfection of organs. (In the middle column, I provide English translations of the major groups recognized by Lamarck.) Relative to modern classifications, the accuracy of Lamarck’s table varies; for example, fungi is now regarded as its own kingdom, separate from plants. Although read from top to bottom, the table represents a very finely grained scala naturae, much more so than that of Charles Bonnet (see figure 1.4). Further, unlike for Bonnet, we see no horizontal divisions in Lamarck’s tables. It may not be so much that Bonnet wished to show such divisions, but it is clear according to Stevens (1994) that Lamarck intended a continuous scala naturae, with the result that demarcations or limits of higher taxa were arbitrary. As Stevens further notes, Lamarck thought that naturalists erroneously confused reconstructing the order of nature with assigning names to organisms. Although biologists now know that evolutionary change drives the system, they still haggle over how phylogenetic reconstruction should be reflected in the names applied to species and higher taxa. Also, Lamarck’s views on his system did not remain static, for in 1786 he reversed and in part reorganized the whole sequence for some of the plants (Stevens 1994). These and later changes in his scientific views characterize Lamarck as a forward-looking biologist. Although the remainder of the three volumes of Flore françoise carry on through the angiosperms, or flowering plants, of France, for some reason Lamarck stopped with the grasses and relatives or monocotyledonous plants (flower-bearing plants with a single rather double embryo in the seed) in his four scala naturae tables in volume 1. Instead, near the beginning of volume 2, following the title page and four pages of advertisements, Lamarck provides a foldout of his table of principal divisions of the plants he analyzed, not unlike the much simpler table from Linnaeus (see figure 3.1). Lamarck’s table includes bracketed names of major plant groups and their characteristics, leading to smaller, more inclusive groups of plants and finally numbers indicating where they might be found in the volumes. Such tables, which are neither trees nor ladders, became a common method by at least the eighteenth century of providing a convenient way to show an author’s classificatory scheme. Similar schemes continue to this day.

FIGURE 3.6 Composite of Lamarck’s four tables showing the progression of plants (and fungi), read from the top-left down and then from the top-right down, from Flore françoise (1778).

Within the time frame of the publication of Flore françoise, the realization emerged that a purely linear intergradation of species in the scala naturae did not explain the great breadth of nature. Lamarck began his career within this framework, but it soon began to change, and he with it. We cannot be sure, but he probably began to shift his ideas about the immutability of species slightly before he started viewing the pattern of evolutionary change in any sort of bifurcating manner. There appear to be no clear statements of his ideas on the topic within his botanical works in the late eighteenth century, but by 1802, after he began to work on invertebrates, his views clearly reflect an evolutionary bent. In the appendix to Recherches sur l’organisation des corps vivans (1802), he writes: “I have for a long time thought that species were constant in nature, and that they were constituted by the individuals which belong to each of them. I am now convinced that I was in error in this respect, and that in reality only individuals exist in nature” (141; Packard 1901). In the next few pages in the same work, after Lamarck discusses how the changes in the physical earth relate to the biological realm as well as chastising himself and other naturalists for their blindness about the fixity of species, he states: “All changes that each living body has experienced as a result of changes of circumstances that influenced his being, will no doubt spread.…But as new changes necessarily continue to operate, regardless of slowness, not only will it always form new species, new genera, and even new orders” (143). Lamarck could not be more explicit in his argument for evolutionary change causing speciation and the origin of higher taxa such as orders.

In writings of Lamarck from 1801, Packard (1901) believed that he had found indirect evidence that Lamarck lectured in his courses about the possibility of evolutionary change by the 1790s. Whatever the case may be, by the earliest years of the nineteenth century, Lamarck was beginning to write about evolutionary change, which also changed his views from one of straight-line order in nature to some sort of bifurcations in nature’s order.

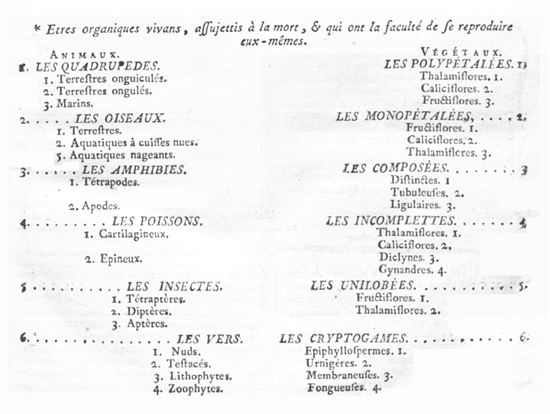

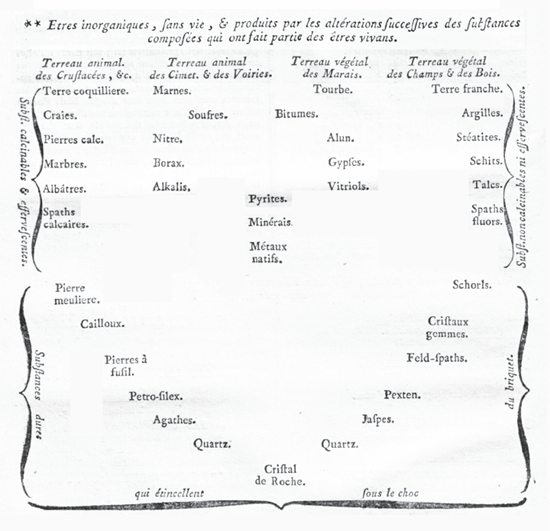

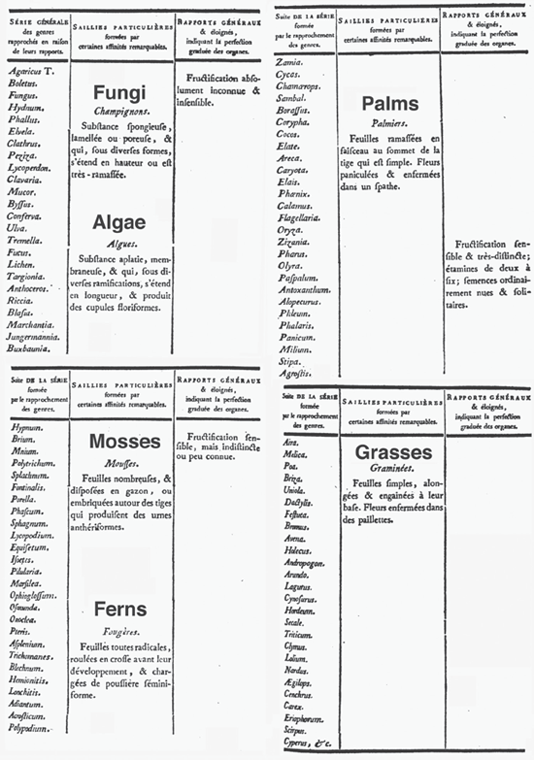

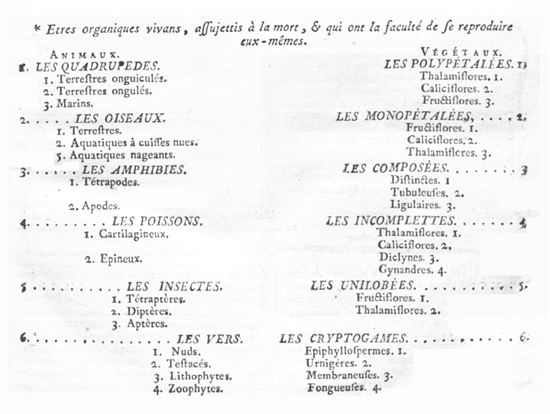

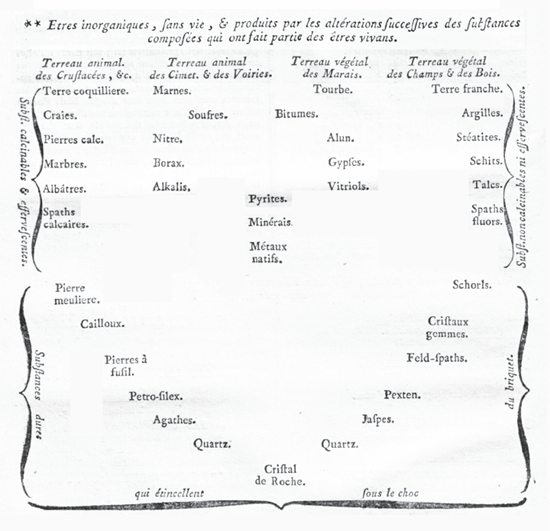

What may be the earliest figure by Lamarck that hints at his changing views on the order of nature, if not evolution, comes in his Encyclopédie méthodique (1786:33). In the figure, he presents what he calls his table of living organic beings—a scala naturae—but of a different kind. Instead of a single line of plants and animals, on the left is the progression of animals and on the right the progression of plants (figure 3.7). Interestingly, unlike Lamarck’s earlier attempt for plants, this diagram opens upward and the two branches diverge. If this were not enough, on the very next page, Lamarck presents us with another scala naturae, but this time of inorganic beings, beginning at the base with crystalline rock and diverging left upward toward animals and on the right toward plants (figure 3.8). He makes the point that in each table, these form different successions, but successions nonetheless. Lamarck has gone beyond the Bonnet-style ladder of life, or even his own earlier work, now seeing in both the inorganic and organic worlds that divergences exist, and not simply ladders.

FIGURE 3.7 Lamarck’s “table of living organic beings”—“Living organic beings, subject to death, and who have the ability to reproduce themselves”—from Encyclopédie méthodique (1786). (The English translation is by the author.)

These earlier figures along with Lamarck’s comments bring his famous 1809 bifurcating diagram—the earliest known evolutionary tree—into clearer focus. He began with a scala naturae (for plants) in 1778 (see figure 3.6), changed to a bifurcating scala naturae of plants and animals diverging one from another in 1786 (see figure 3.7), as well as even more divisions of inorganic matter set below plant and animal life (see figure 3.8), and finally arrived at his bifurcating diagram in 1809 (see figure 3.5). We cannot but notice that he first uses a table opening downward, then one opening upward, and finally one downward again in 1809, but it seems no more than his changing graphic preference. Lamarck’s diagram can fairly be called the first evolutionary tree of life because it marries a branching diagram with evolution as the mechanism creating the branching (Archibald 2009). In his discussion preceding the diagram, Lamarck (1809) hypothesizes that the loss of the hind limbs and pelvis in cetaceans and the similar trend in seals are a result of disuse, one of his themes for the cause of evolution:

If it is considered that, in the seals where the pelvis still exists, this pelvis is impoverished, narrowed and without hip projections; it will be felt that the poor use of the posterior feet of these animals must be the cause, and that if this use entirely ceased, the hind feet and even the pelvis could at the end disappear.…The following chart will be able to facilitate the intelligence of what I have just exposed. It will be seen there that, in my opinion, the animal scale starts at least with two particular branches, and that, in the course of its extent, some branches appear to finish in certain places. (462)

Lamarck’s views changed over time, which results in some confusion as to his intentions at any given time. Earlier he represented the organization of life (actually plants) in a nonevolutionary, infinitely graduated scala naturae; later, as some branching scala naturae during the time he may have first contemplated evolution as a cause; and finally, as a tree-like, bifurcating figure that has been read both as an evolutionary scala naturae and as a figure showing descent. The dual aspects of Lamarck’s theory of evolution—the inherent tendency of matter to develop increasing perfection and the adaptive power of the environment acting on animals through their needs—led Lamarck to his branching diagram (Appel 1980) but does not tell the intent of the 1809 diagram. Similarly, in his essay included in an English translation of Philosophie zoologique, R. W. Burkhardt (1980) addressed Lamarck’s view of the pattern of evolution. Burkhardt noted that by 1802, Lamarck indicated that because of environmental influences, animal species could not be arranged linearly but formed “lateral bifurcations” (xxiv), and further that by 1815, Lamarck viewed a single line of increasing complexity as untenable (xxxiii).

FIGURE 3.8 Lamarck’s “table of inorganic beings”—“Inorganic beings, lifeless, and produced by successive alterations of compound substances that were part of living beings”—from Encyclopédie méthodique (1786). (The English translation is by the author.)

Evolution unquestionably provides the means of change shown in Lamarck’s bifurcating diagram. We must, however, be cautious in interpreting his full intent. As Peter Bowler (1989) clearly articulates, we might assume that Lamarck intended to show in such a diagram the evolution of species from a common ancestor whose descendants adapted and transformed with environmental changes. In fact, Lamarck likely never accepted the idea that living forms descended from a common ancestor. Rather, his view was one of a continually changing scala naturae in which organisms alive today progressed to their present stage separately, probably not unlike what Eichwald (1829) represented in his tree (see figure 3.3). Organisms at different levels of complexity arose from separate events of spontaneous generation at different times shown in his evolutionary diagram. The earlier quote regarding Lamarck’s (1809) bifurcating diagram that “the animal scale starts at least with two particular branches” and that “some branches appear to finish in certain places” (462) makes more sense when viewed in this context.

For Lamarck, what we now call evolution was an ongoing process of multiple spontaneous generations with repeating bifurcations, yielding a tree that shows lines tracking through repeated divergences of one form after another as complexity increased.

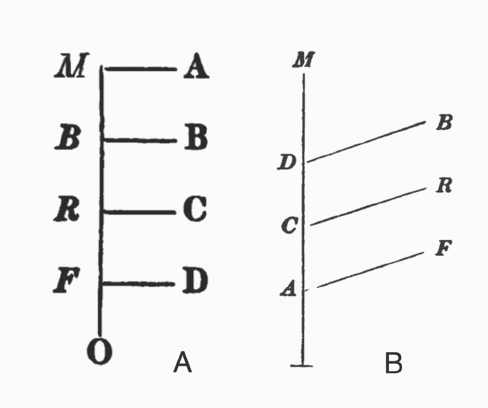

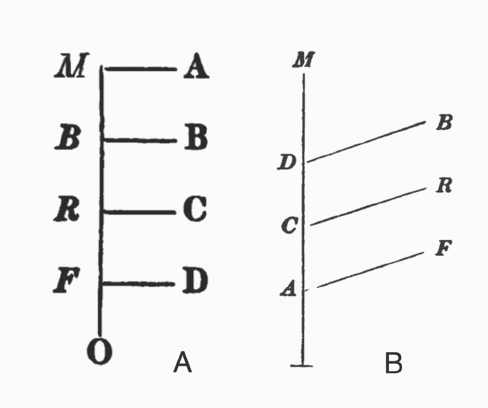

Lamarck was not alone in presenting such diagrams. According to Pascal Tassy (2011), Charles-Hélion de Barbançois (1760–1822) reproduced Lamarck’s tree in 1816, adding greater detail. It was a giant, poster-size, difficult to reproduce figure showing the history from single-celled creatures to monkeys. Tassy notes that the French term filiation was used for the first time, in this context as an unequivocal phylogenetic concept. Although quite fanciful, Barbançois’s tree shows extant groups giving rise to other groups. In 1841, the biologist William Benjamin Carpenter (1813–1885) used a visual metaphor similar to that of Lamarck’s (1809) tree. Unlike either Lamarck’s simple bifurcating diagram or Barbançois’s much more elaborate tree, both of which tracked evolutionary change, Carpenter’s diagram tracked differences in timing of embryological development (figure 3.9A).

Evolving Ontogenetic Diagrams into Phylogenetic Trees

Carpenter was an adept systematizer of the newer biological sciences of the mid-nineteenth century (Desmond 1989). This is well represented by his book Principles of General and Comparative Physiology (1839). Although the volume did include physiology, it dealt in a very major way with what we today call comparative anatomy and development. It covered plants and both invertebrates and vertebrates. Without denying that there may be four great separate Cuverian animal embranchements, or branches of life, Carpenter found strong ties between these groups, in part through their developmental biology.

The work of embryologists such as Karl Ernst von Baer (1792–1876) greatly impressed Carpenter as well as Carpenter’s contemporaries with the argument that during development general characters across various groups of animals appear before the more specific characters of the group appear. He also argued that the embryos of so-called higher animals never resemble the adult forms of so-called lower animals. Both a fish and a mammal have outpocketings in the throat region in earlier stages of embryonic development that go on to develop into true gills in fishes but not in mammals. The mammalian embryo does not replicate adult fish gills in its development. Notably, Carpenter did come to support in a somewhat limited fashion Charles Darwin’s (1859) vision of evolution, and although von Baer finally accepted that evolution was likely, he did not accept Darwin’s natural selection (S. J. Holmes 1947).

FIGURE 3.9 (A) William Carpenter’s diagram tracking differences in timing of embryological development, from Principles of General and Comparative Physiology (1841); (B) Robert Chambers’s very similarly drawn diagram, indicating how embryological changes can be interpreted as an evolutionary history, from Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844).

Carpenter’s diagram (see figure 3.9A) does not appear in the first edition of Principles in 1839 but only in the second edition in 1841 and then not in later editions. I have not found any compelling reasons why this is so. In the preface to the second edition, Carpenter (1841) lists “important additions and alternations” (xi–xii) to numbered paragraphs in the first edition, including the paragraph altered to give a description of figure 3.9A. The first part of paragraph 244 in the second edition corresponds to the entirety of paragraph 203 in the first edition (172), but to it has been added the quite small figure as well as discussion of the figure. This new section of paragraph 244 providing the figure discussion in part reads:

It is to be remembered that every Animal must pass through some change, in the progress of its development from its embryonic to its adult condition; and the correspondence is much closer between the embryonic Fish and the fœtal Bird or Mammal, than between these and the adult Fish.…The new here stated may perhaps receive further elucidation from a simple diagram. Let the vertical line represent the progressive change of type observed in the development of the fœtus, commencing from below. The fœtus of the Fish only advances to the stage F; but it then undergoes a certain change in its progress towards maturity, which is represented by the horizontal line FD. The fœtus of the Reptile passes through the condition which is characteristic of the fœtal Fish; and then, stopping short at the grade R, it changes to the perfect Reptile. The same principle applies to Birds and Mammalia; so that A, B, and C,—the adult conditions of the higher groups,—are seen to be very different from the fœtal, and still more from the adult, forms of the lower. (196–97)

This passage clearly reiterates von Baer’s ideas of general development, yet no mention of von Baer appears, and there is no clear indication of evolutionary change. In the second edition of Principles (1841), Carpenter mentions von Baer only twice in passing, yet Carpenter recognized von Baer’s ideas in the first edition (1839:170), so why not in the second, especially in the context of his figure? As it turns out, this was an unintended oversight. By the fourth edition (1854 [American edition viewed]), Carpenter frequently cites von Baer. In an extended footnote in this edition, Carpenter gives full credit and praise to von Baer for his “great developmental law” (126), noting the use of figures similar to those of von Baer. Although sometimes presented as some sort of rudimentary phylogeny (for example, Barsanti 1992), and as much as we might wish to breathe phylogeny (and evolution) into Carpenter’s branching diagram, it deals solely with von Baerian ontogenetic change from the more generalized embryo to the more specialized adult. This did not mean he accepted Richard Owen’s more idealized Platonic views of embryological morphotypes; rather, Carpenter’s views of embryological development firmly resided with the materialist perspective (Desmond 1989).

This is not the case for a similar branching diagram, which first appeared in Robert Chambers’s Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844) (see figure 3.9B). Chambers (1802–1871) was a successful Scottish publisher, not a scientist, although he was well read in geology. Because of the controversial nature of Vestiges, he chose to publish his book anonymously. His authorship was suspected but not revealed until the twelfth edition of the book (1884), well after his death in 1871. His book was a great success with the public; nevertheless, biologists of the time generally discounted it as unscientific (Secord 2000).

As Stephen Jay Gould notes in Ontogeny and Phylogeny (1977), Chambers’s diagram comes almost straight from Carpenter without attribution. Nor is there attribution of the embryological ideas of von Baer. Chambers’s diagram varies only slightly from Carpenter’s, yet his description transforms it from one of von Baerian embryonic change, as described in Carpenter’s text, into an explication of evolutionary change. The allusion to there being smaller “ramifications” completes the tree analogy, even if Chambers (1844) is not explicit in calling it such:

It has been seen that, in the reproduction of the higher animals, the new being passes through stages in which it is successively fish-like and reptile-like. But the resemblance is not to the adult fish or adult reptile, but to the fish and reptile at a certain point in their fœtal progress; this holds true with regard to the vascular, nervous, and other systems alike. It may be illustrated by a simple diagram. The fœtus of all the four classes may be supposed to advance in an identical condition to the point A. The fish there diverges and passes along a line apart, and peculiar to itself, to its mature state at F. The reptile, bird, and mammal, go on together to C, where the reptile diverges in like manner, and advances by itself to R. The bird diverges at D, and goes on to B. The mammal then goes forward in a straight line to the highest point of organization at M. This diagram shews only the main ramifications; but the reader must suppose minor ones, representing the subordinate differences of orders, tribes, families, genera &c., if he wishes to extend his views to the whole varieties of being in the animal kingdom. Limiting ourselves at present to the outline afforded by this diagram, it is apparent that the only thing required for an advance from one type to another in the generative process is that, for example, the fish embryo should not diverge at A, but go on to C before it diverges, in which case the progeny will be, not a fish but a reptile. To protract the straightforward part of the gestation over a small space—and from species to species that space would be small indeed—is all that is necessary. (212–13)

The branching diagrams in Carpenter’s second edition of Principles (1841) and Chambers’s first edition of Vestiges (1844) are nearly identical. Yet essentially the same iconography has been transformed from showing developmental changes occurring from embryo to adult within four major kinds of vertebrates into an argument of how these embryological changes can be interpreted as an evolutionary history. Interestingly, in this instance the tree of life iconography has here been commandeered for a new scientific purpose from a previous one rather than from a nonscientific source—the scientific method at its best—testable and falsifiable.

God’s Trees

With hindsight, we might think that after Lamarck not only would tree-like diagrams have become prevalent in representing nature’s order but evolution would have become the process to explain these branchings. This was not to be. It was thirty-five years before Chambers anonymously published his small figure expounding on developmental change driving evolution, and it would be another fifteen years until Darwin published his one and only bifurcating foldout diagram in On the Origin of Species (1859), which unequivocally indicated that evolution or transmutation was the process driving the bifurcating. A few tree-like diagrams that toyed with the idea of evolution appeared in the years between Lamarck in 1809 and Darwin in 1859, and these will be discussed, but during most of this time the trees that appeared claimed God’s divine hand rather than evolution as the process.

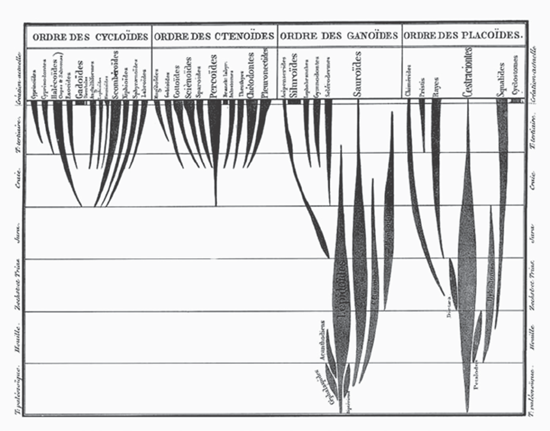

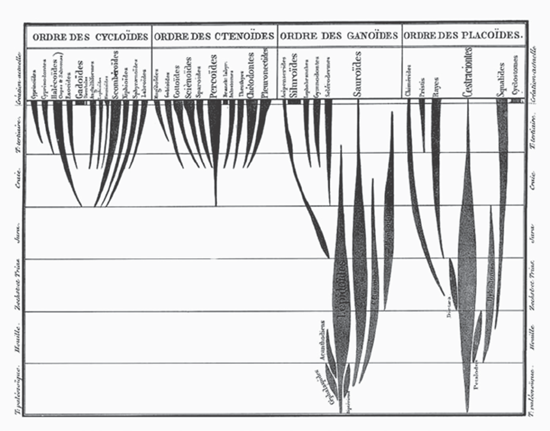

Today when we view a tree diagram replete with names or representations of plants or animals, we visualize “evolutionary history”; why would we not do so? Figure 3.10 shows a nice tree-like figure, and the French title, translated as “Genealogy of the Class Fishes,” surely indicates or at least implies evolution. That the classification is out-of-date is clear from the four orders listed across the top naming kinds of fish scales, a feature that certainly shows an evolutionary stamp but no longer forms the basis for fish classification. The horizontal lines demarcate various geologic times listed on either side, starting in the Paleozoic at the base, again in French, and ending at the top with “Creation actually,” which may be translated colloquially as “present-day appearance or formation.’’ Thus we seem to have not only the evolutionary history of fish but its geologic framework as well. The relative thicknesses of each line of fishes indicate relative abundances at any given time in the geologic past, known today as spindle diagrams because of their spindle-like shape. Although outdated, the diagram presents a hypothesis of relationships.

FIGURE 3.10 Louis Agassiz’s geologically based, nonevolutionary “Genealogy of the Class Fishes,” from Recherches sur les poissons fossiles (1844).

This diagram, by Swiss-born Harvard paleontologist Louis Agassiz (1807–1873), appeared in his Recherches sur les poissons fossils before he first visited and then moved to the United States in 1846. Although sometimes presented as being published in 1833 (for example, Voss 2010), the diagram did not appear until Agassiz’s final volume of the work, published in 1844 (Brown 1890; Archibald 2009). In describing the figure, Agassiz writes:

the family trees on the trunk of which will be registered the oldest kinds, while the branches will bear the names of the more recent types…the time of appearance of each group [is shown] by means of horizontal lines which will cut the branches at various heights…[the] intensity of the development of each family to each time, [is shown] by giving to the various branches of each kind a degree thickness in connection with the importance of the role…in each geological formation…[the diagram] represents the history of the development of the class of fish through all the geological formations and which expresses at the same time the degrees of affinity that between them various families have…[and] finally the convergence of all these vertical lines indicates to the affinity families with the principal stock of each kind. (170)

At the bottom of the page, Agassiz adds: “I however did not bind the side branches to the principal trunks because I have the conviction that they do not descend the ones from the others by way of direct procreation or successive transformation, but that they are materially independent one from the other, though forming integral part of a systematic unit, whose connection can be sought only in the creative intelligence of its author” (170). Thus, as odd as it might seem with our modern perceptions and biases, Agassiz did not intend to represent evolution in this diagram. Published in 1844, it appeared fifteen years before the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species.

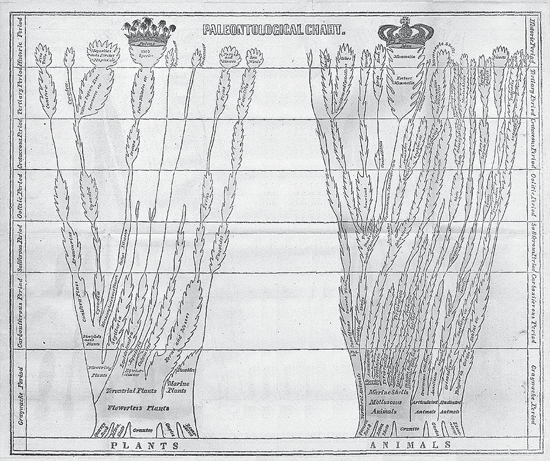

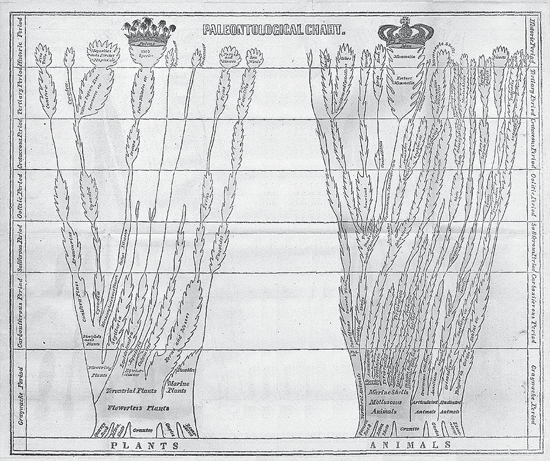

Agassiz’s (1844, not 1833) diagram of fish relationships, at first glance seemingly the earliest evolutionary paleontological tree of life, neither represents the oldest such paleontological tree of life nor shows evolutionary relationships. Today it is the best known of such diagrams, but in its day it certainly was not. Agassiz’s fish diagram appeared in print only once in his lifetime. Edward Hitchcock (1793–1864) had published two trees of similar intent four years earlier, in 1840. Although little known today, in its time his “Paleontological Chart” (figure 3.11) would certainly have been better known than Agassiz’s fish diagram, if for no other reason than Hitchcock’s trees of life were published in his popular Elementary Geology in thirty editions from 1840 to 1856 (or possibly 1859), with another edition, lacking the chart, written with his son Charles between 1860 and 1866.

FIGURE 3.11 Edward Hitchcock’s “Paleontological Chart,” showing geologically based, nonevolutionary trees for plants and animals, from Elementary Geology (1852).

For those who might know of Hitchcock today, it would be for his tenure as president of the small liberal arts Amherst College (1845–1854) and for his description of dinosaur footprints in the Connecticut River valley. Hitchcock held fast to the notion that these footprints were those of giant birds not belonging to Richard Owen’s new-fangled dinosaurs, or “terrible lizards,” a term first used in 1841. We, of course, now know that birds are dinosaurs, so in an ironic sense Hitchcock was correct; possibly we must give him credit for being right for the wrong reason.

Largely forgotten until quite recently (Archibald 2009), Hitchcock’s trees of life seem quite odd to us for the simple reason that while showing the genealogy of various taxa, Hitchcock (and Agassiz) denied that evolution formed this genealogical pattern. Hitchcock maintained a staunchly antievolutionary stance throughout his life, even though he was clearly comfortable using a tree of life to show the history of life. The phrase “history of life” might seem incongruous for a creationist, but Hitchcock was no six-day, Young Earth creationist, for the simple reason that as a geologist he fully accepted an ancient Earth.

Figure 3.11 shows a black-and-white version of the hand-colored, 13- by 16-inch (33 by 41 cm) foldout chart from Hitchcock’s eighth edition of Elementary Geology (1852). Other than slight color variations, this figure appears to be the same from the first edition (1840) until at least the thirtieth edition (1856). Unlike the chart, Hitchcock updated its explanation in later editions. Some salient excerpts, mostly from the first edition, are as follows, using Hitchcock’s (1840) spelling, punctuation, and capitalization:

In order to bring under the eye a sketch of the vertical range of the different tribes of animals and plants, that have appeared on the globe from the earliest times, the Chart which faces the title page, has been constructed. The whole surface is divided into seven strips, to represent Geological Periods.…The animals and plants are represented by two trees, having a basis or roots of primary rocks, and rising and expanding through the different periods, and showing the commencement, developement, ramification, and in some cases the extinction, of the most important tribes. The comparative abundance or paucity of the different families, is shown by the greater or less space occupied by them upon the chart.…The numerous short branches, exhibited along the sides of the different families, are meant to designate the species, which almost universally become all extinct at the conclusion of each period.…While this chart shows that all the great classes of animals and Plants existed from the earliest times, it will also show the gradual expansion and increase of the more perfect groups. The vertebral animals, for instance, commence with a few fishes; whose number increases upward…we ascend, until, in the Historic Period, the existing races, ten times more numerous, complete the series with MAN at their head, as the CROWN of the whole; or as the poet expresses it, “the diapason closes full in man.”…In like manner if we look at that part of the Chart which shows the developement of the vegetable world, we shall see that in the lowest rocks, the flowering plants are very few.…Still more fully developed do we find them in the Historic Period; where 1,000 species of PALMS,—the CROWN of the vegetable world, have been found. (99–100)

Four of the geological “periods” in Hitchcock’s diagram are no longer used: the primary corresponds to the Proterozoic aeon or Precambrian era; the Graywacke spans the Cambrian through the Silurian period; the Saliferous is the Triassic period; and the Oolitic, depending on the source, represents the middle and latter part or the entirety of the Jurassic period.

In describing his trees as “rising and expanding through the different periods,…showing the commencement, developement [sic], ramification, and in some cases the extinction, of the most important tribes [and t]he numerous short branches, exhibited along the sides of the different families, are meant to designate the species,” Hitchcock seems to be describing an evolutionary process, but such is not the case. As noted, he certainly was neither a six-day, literal creationist nor a theistic evolutionist. Rather, Hitchcock regarded God’s direct hand as the agent for biological change over long intervals of geologic time. Thus, unlike the English geologist Charles Lyell (before Darwin’s influence), Hitchcock saw progression in the fossil record, which affected the way he represented it, providing us with a tree of life showing change toward the perfection of man—just below the angels (Archibald 2009).

Beginning with the thirty-first edition of Elementary Geology, which Hitchcock published with his son Charles from 1860 through 1866, the trees appear no more. The absence may be due simply to cost, but there may be a more directed explanation (Archibald 2009). From the first edition (1840) through at least the thirtieth edition (1856), Hitchcock attacked Lamarck’s views on transmutation, as evolution then was often called:

All the important classes of animals and plants are represented in the different formations.…Hence we learn that the hypothesis of Lamar[c]k is without foundation, which supposes there has been a transmutation of species from less to more perfect, since the beginning of organic life on the globe: that man, for instance, began his race as a monad, (a particle of matter endowed with vitality,) and was converted into several animals successively; the ourang outang being his last condition—before he became man. (91)

The next transmutation threat came in the form of Chambers’s anonymously published Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844). Hitchcock’s first response to Vestiges was his inaugural address as president of Amherst College in 1845 (Lawrence 1972), but the first rebuttal in Elementary Geology came in the eighth edition (1847):

[An] anonymous writer very strenuously maintains the doctrine of the creation and gradual development of animals by law, without any special creating agency on the part of the Deity.…But the facts in the case show us merely that the different animals and plants were introduced at the periods best adapted to their existence, and not that they were gradually developed from monads. In the whole records of geology, there is not a single fact to make such a metamorphosis probable; but on the other hand, a multitude of facts to show that the Deity introduced the different races just at the right time. (168)

In the coauthored edition (1862), there is no mention of Vestiges, and the trees of life no longer appear, but now Darwin assumes the mantle of transmutation bogeyman: “‘We find in the history of fishes,’ says Pictet, ‘many arguments against the hypothesis of the transition of species from one into the other.…The connection of faunas, as Agassiz has said, is not material, but resides in the thought of the Creator.’ It is well to take heed to the opinions of such masters in science, when so many, with Darwin at their head, are inclined to adopt the doctrine of gradual transmutation in species” (270).

The reference to so many being inclined to adopt the doctrine of transmutation suggests that Hitchcock saw his antievolutionary views waning. Further evidence comes from the fact that after thirty editions and twenty-two years, his Elementary Geology (1862) no longer carried his trees of life because in 1859 Darwin’s On the Origin of Species appeared, and its sole figure—a foldout hypothetical tree of life—usurped this iconography to support evolution (Archibald 2009). In its place, we find a simple paleontological range chart of reptiles and amphibians modified from the anti-Darwinian Richard Owen’s (1860) text on paleontology. A few thin lines connecting groups of reptiles from one geologic age to the next provide the only concession to the long history of life, and Hitchcock’s exuberant trees of life have vanished.

A final pre-evolutionary tree offers a surprise: it represents the first tree—creationist or evolutionary—by a woman and may well be the only such tree by a woman until well into the twentieth century. Susan Butts (2010) relates the life and work of the author of this tree, Anna Maria Redfield (1800–1888, née Treadwell). Coming from a wealthy Canadian family, Redfield was well educated, including postgraduate classes in Clinton, New York, likely at what became Hamilton College. She was later honored with the equivalent of a master’s degree from the now defunct Ingham University, the first institution of higher learning for women in the United States.

As with most wealthy Victorian women naturalists, Redfield amassed large collections of shells, minerals, botanical specimens, and scientific papers. While living in Syracuse, New York, she attended various scientific conferences and conventions, promoting A General View of the Animal Kingdom (1857), a wall chart showing in tree-like form the relationships of living animals, as well as her textbook Zoölogical Science, or, Nature in Living Forms, which first appeared in 1858 with at least five editions through 1874. Few Victorian women could claim the influence afforded by the publication and use of such an educational wall chart and textbook, yet Redfield remains a poorly recorded, minor figure in the history of women in science, and in the biological and evolutionary sciences (Butts 2010).

Redfield’s remarkable wall chart, which measures just over 4 feet, 11 1/6 inches by 4 feet, 11 1/16 inches (1.5 by 1.5 m), shows considerable artistry in its representation of animal relationships in a clearly tree-like form (figure 3.12A). It remains unclear if she drew this complex lithographic diagram, although she mentions in the dedication to the first edition of Zoölogical Science, or, Nature in Living Forms (1858) that an “esteemed and highly competent friend” assisted. By 1865, this friend, the deceased Reverend E. D. Maltbie, is openly thanked. What role, if any, he played in the production of the diagram remains unclear. In the diagram and in the much simpler version that serves as the frontispiece for all editions examined (see figure 3.12B), the organization follows Cuvier’s four earlier nineteenth-century embranchements: Articulata, Radiata, Mollusca, and Vertebrata. These four main branches occur at the base of the wall chart; although unreadable at the scale provided, they clearly appear in the frontispiece diagram (compare figure 3.12A and B).

FIGURE 3.12 Anna Maria Redfield’s (A) large, complex, tree-like wall chart General View of the Animal Kingdom (1857) and (B) similar but much smaller and simpler frontispiece of Zoölogical Science, or, Nature in Living Forms (1858).

Redfield’s first edition of Zoölogical Science was published a year before Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, so the absence of a discussion of evolution as the basis for her tree might be understandable, but even in the editions of 1865 and 1867, no mention of the evolutionary ideas of Darwin or others appears. Recall that Hitchcock reacted strongly against successive iterations of evolutionary theorizing. Redfield appears consistent through at least the 1867 edition in her sparse but clearly antievolutionary statements. She makes the seemingly evolutionary assertion that in her tree, “each branch puts forth other branches bearing subdivisions” (10), yet later statements belie this sentiment. In her discussion of Owen’s ideas on the muscles in the hands of apes and humans, she concludes, “The teeth, bones and muscles of the monkey decisively forbid the conclusion that he could by any ordinary natural process, ever be expanded into a Man” (22); and her views appear even stronger when writing, “There is no evidence whatever that one species has succeeded, or been the result of the transmutation of a former species” (482). Although unwittingly, the trees of people such as Agassiz, Hitchcock, and Redfield primed the public for accepting, if reluctantly, that trees of life might just represent evolutionary and not merely organizational visual metaphors of life.

One More Tree Before Darwin

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the scientific community, if not the public, was ready for some explanation of why plants and animals appear to emerge from simpler forms. The evidence from geology, paleontology, biogeography, comparative anatomy, and embryology all pointed to the inevitability that evolution occurs. Dismissed by science but embraced by a curious public, the publication of the anonymous Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (Chambers 1844) had primed the intellectual pump in England.

In France in 1850, the Academy of Sciences announced an essay prize competition for a study examining the laws governing how fossils are distributed through geologic time, the timing of appearances and disappearances of species, the relationships between the ranges of fossil species and geologic boundaries, and whether transformation or creation explained species’ originations. Early submissions were not deemed worthy of the prize, so it was offered again, with a deadline in early 1856. The German paleontologist Heinrich Bronn (1800–1862) submitted an essay that was awarded the prize in 1861. It was published in German in 1858 and in French in 1861 with the German title translated as Investigations into the Laws of Development of the Organic World During the Time of the Formation of Our Earth’s Surface (Gliboff 2007, 2008).

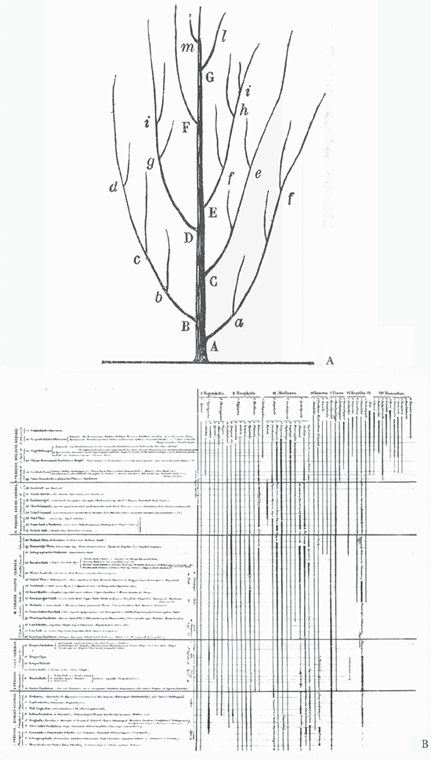

Both the German and French versions of Bronn’s winning essay contained a hypothetical tree of life complete with letters explaining aspects of relationships shown on the tree, not unlike Darwin’s (1960) famous tree in Notebook B and his much more elaborate hypothetical tree that was published in On the Origin of Species in 1859, the year after Bronn’s tree appeared (figure 3.13A). Bronn’s (1861) figure presents us with a wispy, tree-like figure labeled with letters. He appears to have been most concerned with addressing the idea that although there was a trend toward perfection, less perfect forms kept branching even after more perfected forms had appeared:

FIGURE 3.13 Heinrich Bronn’s (A) hypothetical tree of relationships, from Untersuchungen über die Entwicklungs-Gesetze der organischen Welt (1858) and “Essai d’une résponse à la question de prix proposée en 1850” (1861), and (B) “Sequence of the Stratified Formations and Their Members and Distribution of the Organic Remains Therein,” from Lethaea geognostica (1837–1838).

Not only the animals without backbones, the Fishes, the Reptiles, the Birds with hot blood, the Mammals, and finally Man, appeared one after another, but…in lower kingdoms of the Radiates, the Mollusks, the Fishes, the highest branches of the system appeared only after the lower branches, however in such a way that the highest twig of a lower branch appears often later than the lower twig of a higher branch. One wants to represent this state of affairs by a figure, it is necessary to represent the system like a tree, where the more or less high position of the branches corresponds to the relative perfection of the organization, an absolute way and without holding account of the more or less high position of the twigs on the same branch. Thus…[the] first twig g of the fourth branch D appears only after it first twig f of the following branch E already appeared, etc. (899–900)

Although certainly not a creationist, Bronn was less accepting of Darwin’s natural selection as the mechanism for species changes in particular, or any mechanism in general, to explain the pattern of change he saw in the history of life (Gliboff 2007, 2008; Williams and Ebach 2008).

Like Darwin, Bronn struggled to understand what caused the patterns of species distribution in time and space. Both Darwin and Bronn possessed knowledge in geology and paleontology; Bronn’s was more accomplished in paleontology. Unlike Darwin, Bronn did not support the idea that species transformed over time and especially not by Darwin’s natural selection, so the sudden appearances of species in the fossil record must result from some creative force. The cause was unknown to Bronn, although in his view new species always adapted to their ecologic surroundings while maintaining their general taxonomic groupings (a vertebrate remained a vertebrate, a mollusk remained a mollusk); but new forms explored new environments, so a sort of perfection and expansion of diversity occurred over geologic time. According to Bronn, more poorly adapted species decreased in numbers, leading to extinction, only to be replaced by the continuing creation of plants and animals, forming a succession of species over time. He argued that the successional fossil record documented this. In this way, species advanced or progressed over time, again as shown by the fossil record. Further, Bronn argued that the succession of fossils did not support the notions discussed earlier of embryologic development mirroring changes in major taxonomic groups (Gliboff 2007, 2008; Williams and Ebach 2008).

Darwin’s book overshadowed Bronn’s work, soon relegating his efforts to relative obscurity. Ironically, today Bronn (1860) often is best remembered for publishing the first German translation of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. Bronn’s translation influenced the German biologist Ernst Haeckel, sometimes called the German Darwin, who reported having read Bronn’s translation in German in the summer of 1860. As discussed in chapter 5, Haeckel was a consummate artist. Bronn, who experimented with visual methods of comprehending scientific data and ideas, also influenced Willi Hennig’s visual representations of evolution. Bronn died in 1862, soon after the publication of his essay, and thus could contribute no more to the nascent field of evolutionary studies (Oppenheimer 1987; Richards 2004).

Interestingly, Hitchcock (1840) indicated in the footnote to his “Paleontological Chart” (see figure 3.11) that Bronn anticipated his tree figures in Lethaea geognostica (1837–1838). Based on Hitchcock’s comment that Bronn produced “a chart constructed on essentially the same principles,” one would expect to find a tree-like diagram, as in Hitchcock. This is most definitely not the case (see figure 3.13B). Translated from German, Bronn’s figure is titled “Sequence of the Stratified Formations and Their Members and Distribution of the Organic Remains Therein.” Like Hitchcock’s chart, Bronn’s figure shows deep geologic time, many lines representing many different groups known by fossils, and even some variation in line thickness to indicate relative taxonomic abundance. What Bronn’s diagram does not show is any hint of a tree-like or branching diagram. His lines are unswervingly straight, with some change in thickness from bottom to top to indicate an increase in the number of species. What he produced is what paleontologists today refer to as a fossil range chart, which conveys when fossil taxa existed, not how they are related, except very generally by how they group on the diagram. That Hitchcock did not see much difference between his chart and Bronn’s figure indicates that Hitchcock did not realize that his connecting the branches in a tree-like figure held any particular significance beyond what Bronn’s unconnected lines showed (Archibald 2009). It is no wonder, then, that Hitchcock’s tree-like “Paleontological Chart” disappeared from print once he realized that it was more akin to Darwin’s (1859) hypothetical tree figure showing the evolution of life than to Bronn’s diagram showing the paleontological succession of life.