Chapter 10

History of Entrepreneurship

Germany after 1815

THE HISTORY OF ENTREPRENEURSHIP in Germany is as tortured as the history the country inflicted on its neighbors and on itself. For much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, entrepreneurs in Germany were confronted by the consequences of political upheaval, shifting borders, major institutional rearrangements in the wake of regime changes, and all the limitations and temptations that went with frequent redefinitions of the rules of the game. With six political systems—two of them side by side for the second half of the twentieth century—two controversial political unifications, two aggressively fought world wars, and continually changing borders, Germany after 1815 was a taxing environment for such planning as building a firm. It is no wonder, therefore, that the two spells of prolonged political stability, from first unification in 1871 until World War I and the post–World War II period in West Germany, were those when most big enterprise was formed and when innovativeness, though very different in style, was a pertinent characteristic of German enterprise.

Schumpeterian entrepreneurs are particularly capable of responding to incentives and opportunities in their environment and of dodging its limitations. Their great contribution to the economy as a whole resides in their ability to put the potentials within their reach to more profitable use than they would receive under established routines and practices. If they are motors of change and productive unrest, innovative entrepreneurs themselves seem to thrive under conditions of institutional predictability amid favorable resource endowments. To assess better the preconditions for innovative entrepreneurship through the history of the Germany economy, I turn to a brief outline of its natural and its human resources as well as its institutional framework.

The German Economy, 1815–2006

Geography, Borders, and Natural Resources

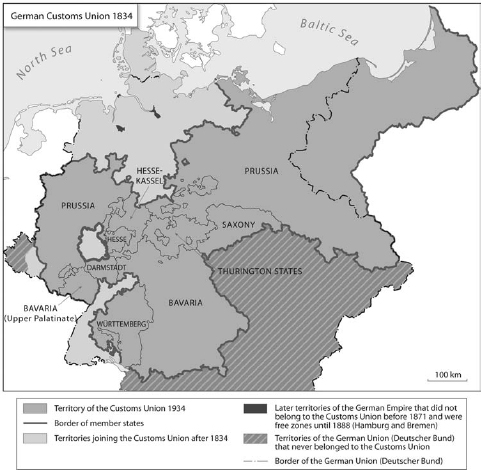

The German Confederation, created in 1815, was a loose formation of thirty-nine sovereign states where German was the dominating if not always the exclusive language. The two major states, Prussia and the Habsburg Empire, had territories within and outside the German Confederation. Against a reluctant Austria, Prussia took the initiative of facilitating trade among the German states and eventually, in 1834, was successful in creating the German Customs Union, which, most significantly, excluded Austria. In the middle of the nineteenth century, the German Confederation was economically divided between Austria and a Prussian-dominated area largely within the borders of what was to become the German Empire in 1871. By 1834, entrepreneurs in the German Customs Union were already operating in a nascent common market long before there was political unification. Economically, the Prussian-dominated German Customs Union developed more quickly than the Habsburg Empire. Politically, however, the situation was anything but stable and predictable. With a revolution in 1848–49 and three “wars of unification” that drove Austria out of Germany and brought the other sovereign German states under Prussian dominance, the political and institutional environment did everything but inspire confidence. Stability did exist, however, within Prussia, which comprised about two-thirds of the later German Empire. In Prussia we find the most vigorous economic development, spreading from there to the other partners in the Customs Union.

Figure 10.1. The German Confederation and the German Customs Union in 1834. (Source: http://www.ieg-maps.uni-mainz.de/mapsp/mapz834d.htm, accessed October 10, 2007.)

Figure 10.2. The Federal Republic and the GDR 1957. (Source: http://www.ieg-maps.uni-mainz.de/mapsp/mapp957d.htm, accessed October 10, 2007.)

Prussia, which had absorbed many territories in the west after the defeat of Napoleon and the dismantling of ecclesiastical territories, was also in a privileged position when it came to natural resources. Germany's main hard coal, lignite, and iron ore deposits were all in Prussian territory. The most valuable asset was an enormous hard coal deposit in the Ruhr district close to the river Rhine. This area became the powerhouse of the German economy well into the twentieth century. It was not coal mining, though, that kicked off industrialization in Germany but railway construction (Fremdling 1985; Holtfrerich 1973). In the absence of suitable waterways—the main rivers run from south to north while the potential domestic market stretched from west to east—railways were to become the integrating infrastructure of the nascent industrial economy. Railway construction, mostly private, but backed by some state guarantees in Prussia, was a great opportunity for the financial sector as well as for iron-making and machine-building. Once the railways were in place, they supported the division of labor within the economy and transport of cheap fuel to places outside the mining areas. Only heavy coal consumers like the chemical industry (Hoechst, BASF) would go for locations along the navigable parts of the river Rhine but closer to consumers in traditionally more urbanized southern Germany. Berlin, the Prussian and later German capital, became a center for modern mechanical and electrical industries, which had to rely on state support in their formative years (von Weiher 1987). A more traditional center of mechanical engineering was Saxony, a semisovereign kingdom south of Berlin. A second coal basin was in Prussian Upper Silesia, in southeast Germany, about the same distance from Berlin as the Ruhr district. The east-west orientation of the German economy as well as the dominance of coal-based industries persisted until the end of World War II.

With the east-west division of Germany after World War II and the loss of the eastern coal basin and agricultural surplus regions to Poland, however, the economic geography of both German postwar states was fundamentally transformed. Geographically and hence economically, post–World War II Germany is a country very different from the former “Reich.” Together with this geographical reorientation, hard coal lost its competitiveness in the late 1950s, leaving only lignite in both German states as a domestic if largely insufficient source of energy and the very last natural resource that could be exploited profitably (Abelshauser 1984). While Germany started with comparatively good resource endowments in the nineteenth century, today only ecologically highly controversial lignite is left for some electricity generation. According to an often evoked self-perception in postwar Germany, its only natural resource is the gray matter in German brains.

Human Capital Formation

Human capital formation was an early success story in Germany. Primary education was fairly advanced in Prussia. Vocational training had traditionally been a stronghold of the guilds and trades. Higher education was very much helped by political fragmentation of Germany in the nineteenth century and by federalism in the twentieth. Since every prince believed he must have a university, a polytechnic, and trade schools of his own, Germany was comparatively oversupplied with these institutions. This was also true of Prussia, as the newly incorporated and rather unenthusiastic territories that had put Prussia on an equal footing with Austria had to have the full array of institutions of higher education not to feel treated as second-class provinces. This fortunate diversity and plurality very much helped the creation of a great number of polytechnics along the model of the French École Polytechnique in the middle decades of the nineteenth century before German unification. The alumni of these polytechnics—there were no formal degrees until 1899—in the majority did not go to industry but became state officials with little if any beneficial effect upon Schumpeterian entrepreneurs' success (Lundgren 1990, 44). The same is true for science graduates from universities. Nevertheless this oversupply of highly qualified scientists and engineers turned to Germany's advantage when the first science-based industries emerged at the end of the nineteenth century. Institutes of technology and science departments in universities were well developed and among the most attractive in the world. Around the turn of the century German was the privileged language of science. German companies could draw from the most productive pool of scientists and engineers and cooperate with the most advanced university departments (Wengenroth 2003, 246–52).

This fortuitous setting was brought down by Nazi politics after Hitler's rise to power early in 1933, in a two-pronged attack on German universities. First, student enrollment was more than halved by the Nazis in the six years up to World War II, out of fear of an academic proletariat. In 1939 Germany had no more students than in 1900 (Berg and Hammerstein 1989, 210). Second, from spring 1934 all state employees who were defined as Jewish by the Nazis were expelled from their positions. The same law applied in all annexed territories beginning with Austria in 1938. Along with much greater tragedy, this led to an enormous loss of scientific elite, with 20 Nobel laureates among them (Titze 1989, 219). The two policies together came close to a self-decapitation of the German innovation system. A second and a third wave of emigration of scientific and engineering talent followed in the years after the war. First, a great number of top scientists left right after the war, either because they feared to be taken to justice for war crimes such as abuse of concentration camp inmates, or because they were hired (in the case of the USSR also abducted) by the victorious allies, and often for both reasons. The third wave occurred in the decade after the war when Germany was banned from developing a number of cutting-edge technologies. Young scientists who wanted to work at the research frontier and have a career in cutting-edge technologies had to leave the country, preferably toward America. In sum, these three waves of elite loss substantially contributed to the fundamental transformation of the German innovation system in the middle decades of the twentieth century from a high-tech pioneer to a fast follower with an uneven product portfolio (Wengenroth 2002). The loss of the leading position in Nobel laureates in physics and chemistry is just one of many illustrations of this transformation, to which of course the stunning success of American science is the other side.

Figure 10.3. Cumulated number of Nobel laureates in physics and chemistry. (Source: nobelprize.org.)

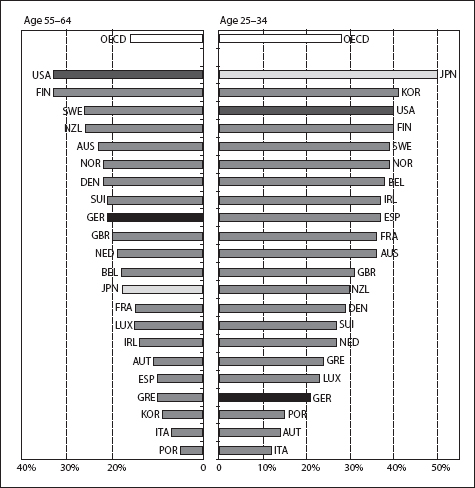

Figure 10.4. Population with a tertiary education as a percentage by selected age groups, 2002. (Source: Federal Ministry of Education and Research, 2005 Report on Germany's Technological Performance—Main statements from the federal government's point of view, 4.)

Today, Germany has barely an average share of population with a university or equivalent degree, compared with other advanced OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries. The times when entrepreneurs could draw on an overabundant supply of excellently educated young people are behind us.

As the OECD compilation in figure 10.4 shows, Germany in 2002 had a respectable if not brilliant position in the age group 55–64, but has failed to keep up with its competitors in the younger age group 25–34. It seems to be a characteristic of the German educational system that it continues to lose steam. The OECD's PISA report came to the same conclusion. And the most recent 2007 OECD report “Higher Education and Regions” confirms this negative trend. Germany is among the underperformers in an OECD-wide comparison of higher education in key sectors like engineering, biotechnology, science, and agriculture.

For German entrepreneurs this means that their home base is no longer privileged to the extent it once was when it comes to recruiting the kind of academic excellence that is usually understood to be the backbone of innovativeness in business. Major companies, therefore, have undertaken to increase their share of foreign employees in R & D in recent years. The inhospitable policy of the German government vis-à-vis foreign labor, however, makes Germany an unattractive destination for the most ambitious and best-educated professionals, who increasingly bypass Germany for more promising careers in other west European countries. Indicative of this somewhat worrisome trend is Germany's position in Richard Florida's Euro- Creativity-Index. While Germany in this comparison of fourteen European societies and the United States still ranked a reassuring third in the overall innovation index and a respectable sixth in the high-tech innovation index, it is only eleventh in the creative class index (Florida and Tinagli 2004, 32). Here again, we have the picture of a downward slide from bustling top performer to struggling second-rater. It is still difficult for a substantial number of politicians to accept that there is no easy way back to the modernist, highly creative, and scientifically stimulating Germany of the early twentieth century when talented students all over the world learned German to visit and participate in a then highly creative milieu. Today, for a bright east European scientist from one of the new member states of the European Union, the UK or the Netherlands is a more promising place to go.

The Institutional Framework

The trade policy of the nineteenth-century Customs Union was based on the principle of “educational tariffs,” that is, tariffs that were adopted to protect infant industries until they could withstand international competition. Customs duties were gradually reduced up to the first years of the German Empire, opening the German market to ever more industrial products and—very important—coal from Britain for places like Hamburg or Berlin that had water access. This trend toward free trade came to a halt and was eventually reversed in the 1870s in the wake of a major international financial and trade crisis triggered by the collapse of the American railway boom. By 1878 the tide had turned and Germany had a protectionist policy, one way or another, until after World War II.

Dependent on tariff protection, a second and even more important anticompetitive arrangement was the enormous spread and, eventually, even enforceability of cartels. Cartels mushroomed after the protectionist reversal of the 1870s. They were defended as freedom of contract, and the highest court of the empire in 1897 decided that cartel agreements were not only legal but binding on all partners and could be enforced (Wengenroth 1985). To Alfred Chandler, Jr., this was a watershed setting Germany firmly on the path of cooperative rather than competitive capitalism (Chandler 1990, 393–95). By 1897, however, big industry in Germany had already twenty years of intensive cartelization behind it. The climax of cartelization came with the Nazis and their Zwangskartellgesetz of 1933, which made cartels mandatory in the interest of Nazi economic planning. After World War II, under pressure from the United States, the cartelization of German industry was largely made illegal if not completely abolished. It was a second watershed when in 1957, after almost a decade of debates and preparations, anticartel legislation reversed the rules of the game after sixty years of formal and almost a century of informal dominance of cooperative capitalism. With integration in the European Economic Union and falling tariffs in a number of GATT agreements the main pillar of cartelization, the protection of the domestic market was finally eroded. This did not spell the end of collusive action, especially since the EEU established its own fabric of market regulation that often came close to cartels, but it greatly reduced its reach and made it an awkward and clandestine refuge rather than a legitimate and legally protected policy.

Intellectual property rights were hardly protected before 1877 when the German patent law was passed. Before that year, governments of German states, and particularly of Prussia, were reluctant to grant patent protection in an effort to ease transfer of knowledge from abroad. There were famous cases of patent denial like both the Bessemer and the open-hearth processes of mass steel production, both of which had successfully been patented in Great Britain. All this changed when Prussia believed that German industry had successfully caught up and was in a position to turn from imitator to bona-fide innovator. The German patent law protected the process rather than the product, thus stimulating research for alternative ways to turn out the same product. This proved to have a highly stimulating effect on corporate research and development (Seckelmann 2006).

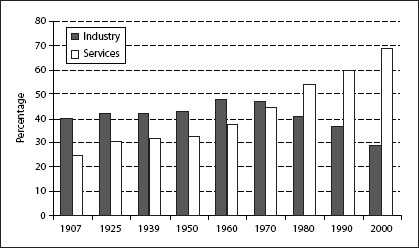

The Overindustrialized Economy

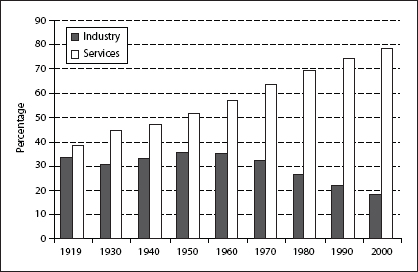

The German economy has mostly been identified with its industrial prowess. Services are not a hallmark of its reputation. In comparison with its nearest competitors and certainly in comparison with the United States, the German economy was overindustrialized all through the twentieth century. This strength of German industry came at some opportunity costs that are currently creating major problems in the transition to markets dominated by immaterial products or the immaterial aspect of “things.” Since productivity per hour worked was not higher in Germany than among its neighbors and often lower, the focus on industrial rather than service production didn't necessarily constitute an advantage. The high share of employment in the industrial sector did, however, strongly influence self-perception and eventually what might be called innovation culture. Germans were confident about their industry, a view that was reaffirmed by many foreign observers, and believed in the competitive advantage of German industrial production. That this advantage might have been more an effect of the size of the effort that went into industry than of productivity did not occur to the public nor to the authors of much of the literature on German economic history.

Comparing the German situation with that of the United States, by all means the most productive economy in the twentieth century, which in the mid-1920s and the mid-1950s turned out about 45 percent of the world's industrial products, makes evident the importance of the fact that in productivity calculations the labor force is the denominator. International productivity comparisons by Baumol and others show the modest productivity of the German economy (Baumol et al. 1989, 92; Maddison 2001, 353).

Germany's great reliance on industry was also reflected and continues to be reflected in its science and technology policy. The federal ministry of education and research favors the promotion of industrial technologies and hardly supports the development of services—including knowledge-intensive services—at all. Over the years 2007–2011 a mere €70 million will be devoted to research in services while billions will go to technologies.1 The lag in transforming the German economy into something like a knowledge and information society has crystallized into a cultural lag of the whole innovation system. It seems extremely difficult for the political system as well as for the business community to overcome the industrialtechnological imprint acquired during the protectionist decades from late nineteenth to mid-twentieth century. Reading official German statistics is sometimes remindful of Marxist terminology, when what is called “industry” or “manufacturing” in other countries in Germany is produzierendes Gewerbe, literally translated as “producing trades,” while no other sector of the economy qualifies as “producing,” suggesting that everything else is “unproductive.” The latter view is certainly still very much in the mind of many engineers, who unsurprisingly find it difficult to appreciate the services let alone the semiotic character of most modern consumer goods.

Figure 10.5. Employment in Services and Industry, Germany. (Data source: 1950–2000: http://www.destatis.de/jetspeed/portal/cms/Sites/destatis/Internet/DE/Content/Statistiken/Zeitreihen/LangeReihen/Arbeitsmarkt/Content75/lrerw13a,templateId=renderPrint.psml (accessed: October 14, 2007); 1907–39: Geißler and Meyer 1996, 29.)

Figure 10.6. Employment in Services and Industry, United States. (Data source: U.S. Census Bureau, Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970, Series D 1-25, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2003, HS 29-30.)

This disrespect notwithstanding, labor in cutting-edge services in Germany is more productive than in cutting-edge technologies (Götzfried 2005, 4). On the other hand, Germany does have a lower than average share of employment in knowledgeintensive services than its neighbors in the European Union of fifteen. Productivity in knowledge-intensive services among Germany's western neighbors is significantly higher (Felix 2006, 3). Here again, the opportunity costs of sticking to traditional strengths in industrial production seem substantial. Because of the overindustrialized structure of the German economy, as much as the overindustrialized mentality in society, we find more entrepreneurial innovativeness in industry than in services. Moreover, of the one hundred largest industrial corporations of 1913, eighty-seven produced raw materials, intermediates, and investment goods, while only thirteen belonged to the consumption good sector, whereas in America and Great Britain the two sectors of industry held about equal shares (Dornseifer 1995, n. 7; Chandler 1990, appendices). While a balanced history of the German economy after 1815 would focus on the service sector at least as much as on industry, a history of innovative entrepreneurship inevitably favors the latter.

Entrepreneurs in German Society

Entrepreneurs in Early Industrialization

Entrepreneurs were newcomers to the elites of nineteenth-century German society. They were mostly close to the reform movements of European liberalism. Those who were young in the 1840s often had great sympathy for the revolutionary parliament in Frankfurt. When the revolution was crushed by Prussia and Austria, many students, among them many future entrepreneurs, left the country. More liberal Switzerland and its splendid Zurich Polytechnic, founded in 1856, were to become a temporary haven for young engineers and scientists. Entrepreneurs in the western provinces of Prussia moved freely among Belgium, France, Luxembourg, and the Rhineland and felt limited solidarity with the new rulers in Berlin. This skepticism was largely mutual and took decades to subside. Railway entrepreneurs of early industrialization were said to have displayed a “profound bourgeois closeness” (Then 1997, 258). There has been an ongoing debate over the extent to which German entrepreneurs after the failed revolution of 1848–49 moved to the right politically or whether they stuck to their republican convictions. This problem is even more complicated by the fact that the more left-leaning democratic faction was both corporatist and protectionist, while more conservative “big business” and landowners favored deregulation. It seems that entrepreneurs with trading interests and in manufacturing industries continued to lean toward liberalism (in the European sense), while those whose business was rooted in domestic raw materials moved to the conservative and protectionist right (Wehler 1995; Biggeleben 2006).

Anti-Semitism

Excluded from such public recognition of respect by the traditional elites were Jewish entrepreneurs. Anti-Semitism was pervasive in the empire (Mosse and Pohl 1992). And in spite of continuous progress toward emancipation, Jews remained sidelined in imperial Germany. Under the Weimar Republic this seemed to change for the better. Although entrepreneurs were not known to appreciate the new democracy, as they favored an authoritarian regime that had made life for them so predictable through the decades of the German Empire of 1871, anti-Semitism was not felt to be on the increase. Even many Jewish entrepreneurs didn't take the anti-Semitic aggressions of the rising Nazi party too seriously, believing it to be more propaganda than policy (Feldman 1998).

Even in the early 1930s, hardly anybody among the Jewish business elites was prepared for the catastrophe to come. With hindsight, this complacency about the Nazis' plans seems very naive. The political scientist Karl W. Deutsch has characterized the 1930s in Germany as a time of “cognitive catastrophes,” when much of the German public and entrepreneurs among them failed to realize the murderous implications of official anti-Semitism (Deutsch in Broszat 1983, 324). The dominant attitude among business elites, including many Jewish entrepreneurs, was the desire for some form of authoritarian regime to reign in socialism and bring back the stability of the late empire that had been glorified retrospectively. To many, Nazi rule was an unpleasant if preferable alternative to, as it was seen, divisive democracy. When outright persecution of the Jewish population set in, however, it became clear that humanitarian values were not a priority to the vast majority of German entrepreneurs. Only very few of them hesitated to enrich themselves on the spoils of “Aryanization.”

It seems true that in their majority entrepreneurs were not ardent Nazis. Nor had German business “paid Hitler.” Support, including support by Jewish entrepreneurs, went rather to other authoritarian parties of the Weimar Republic, which eventually paved the way for Hitler, whom they erroneously had believed to be their puppet (Turner 1985; Neebe 1981; Weisbrod 1978). In the end it was the total absence of morality and compassion that struck their victims as much as most observers from abroad. To German entrepreneurs the company came first, and it was their standard excuse after the war that they had to shepherd the company “through difficult times” (Erker and Pierenkemper 1999). Well into the postwar years it didn't occur to them that moral indifference vis-à-vis a murderous regime constituted a catastrophic failure on their side. As Paul Erker observed, summing up research on the continuity of business elites and their mind-set from the Nazi years to the early Federal Republic, there was “no rethinking and hardly any meditation” (Erker in Erker and Pierenkemper 1999, 16).

Nonmonetary Rewards for Entrepreneurs

While profit is the ultimate yardstick of entrepreneurial success, it is certainly not the only source of respect. Entrepreneurs, like anyone else, aspired to nonmonetary rewards to gain status. Schumpeterian qualities, however, were not a consideration, although they could come into play indirectly. During the nineteenth century and until the end of World War I, nonmonetary rewards most sought after were titles bestowed upon by the monarch. This could range from the Kommerzienrat (councilor of commerce) to nobility. The Kommerzienrat or the more prestigious version, the Geheimer Kommerzienrat, which meant that he had access to the court, was mostly earned for some substantial charitable endowment. The Kommerzienrat was so widespread among entrepreneurs that it didn't carry much prestige. It was more an embellishment of the person's salutatory address and proof that he could afford to be generous. And, equally important, it was not a political commitment to the monarchy.

This was different from nobility. While craving for nobility was notorious among bureaucrats and officers and turned into an inflationary process during World War I, it was not a matter of course that successful entrepreneurs would by all means at their disposal strive for a prestigious von in front of their name. In fact, German entrepreneurs were much less likely to be ennobled than their British counterparts. Some of the most prominent and highly successful entrepreneurs in the German Empire kept their distance from feudal values. Krupp, both Alfred and his son Friedrich Alfred, and August Thyssen, the most successful steel barons of the German Empire, turned down the offer, while Werner Siemens, who began his career in the Prussian army, gladly accepted the distinction. Such was the steel barons' pride in their own name that their children, when they married into the nobility, kept their common name in front of the noble family name.2 In their eyes an industrial empire was obviously already more of an achievement than noble descent. Pride in and respect for entrepreneurial success began to eclipse hereditary status at the turn of the century (Berghoff 1994).

At the same time a new source of respect and status emerged. Kaiser Wilhelm, himself a great admirer of science and engineering, very much against the opposition of the traditional universities created the title of “doctor engineer” for the Technische Hochschulen (institutes of technology). This opened new opportunities for ambitious engineers to gain the kind of respect and recognition that had been the privilege of the humanistic elites of the traditional worlds of learning (König 1999). And it was a watershed; academic titles in engineering and science soon displaced the Kommerzienrat and the Geheimer Kommerzienrat, while the Honorarprofessor(honorary professor), which in everyday life often was stripped of its somewhat depreciating prefix Honorar to sound like a bona-fide professorship, carried the status of nobility. Whatever the dubiousness of some honorary degrees, the currency of status and vanity had changed. More prestigious universities would look more closely at the validity of reasons to confer academic distinction. The Honorarprofessor, even if a CEO, would have to teach students and often was interested in fostering common research programs in his company and his university. The academization of entrepreneurial prestige through the twentieth century was as much an expression as a strengthening of a knowledge-based approach to managing product development. Moreover, empirical studies show that honorary titles toward the end of the twentieth century tended to be given more to distinguished people in the field than to industrialists of the nearby region (Fraunholz and Schramm, forthcoming).

Internationalization of German Entrepreneurs

Even if German nationalism comes first to mind, German enterprise for most of its history had a strong international dimension. In early industrialization we find Belgian entrepreneurs who, by following markets and raw materials, crossed the border into the western parts of Prussia. They were among the most innovative iron- and steelmakers, bringing modern British steel technology to Germany and using their German companies as a launching pad for direct investment in tsarist Russia, taking talented German managers with them (Troitzsch 1972; Wengenroth 1988). The longtime president of the most influential lobbying organization of the west German iron and coal industries in the early years of the empire was William Thomas Mulvany from Dublin, Ireland. With the annexation of Alsace and Lorraine in 1871, a great number of French entrepreneurs, very much to their dismay, found themselves in Germany. At the same time, German-owned companies would recruit top managers in Great Britain. One example is Krupp, who had recruited Alfred Longsdon from the Dowlais Iron company in South Wales as one of his directors (Wengenroth 1994a, 74–91). Longsdon was personified technology transfer and a driving force behind converting Krupp into one of Europe's first mass steel producers. Together with Dowlais and another British steelmaker, Krupp acquired Europe's richest iron ore deposits for high-quality steelmaking in northern Spain in the 1870s, setting up a Spanish company registered in London that turned out to be a backbone of Krupp's profitability until World War I. Thyssen, who had been too late for the Spanish bonanza, created a number of raw material suppliers from France to Sweden, carefully tiptoeing around national sensibilities (Wengenroth 1987). Well into the twentieth century the Netherlands was both the most important channel of trade and a preferred smokescreen of the German steel industry's international operations. The German electrical industry preferred Belgium and Switzerland for their financial operations worldwide (Liefmann 1913). In the decades up to World War I, a number of major German companies made nationality part of their strategy. At the last AEG shareholders meeting before the war, Emil Rathenau was confident that “political unrest and wars in Europe” would do only little harm to the company's business since “a substantial part of our customers is spread all over the globe” (AEG 1956, 189).

The two wars Germany fought against its neighbors and America in the first half of the twentieth century, as well as intensified protectionism, turned earlier international integration into isolation. By losing many of their foreign subsidiaries and much international goodwill, German companies became more German, and German entrepreneurs were increasingly confined to the homeland. If there were still substantial exports, they were no longer accompanied by the extensive networks of foreign direct investment that had helped German entrepreneurs feel at home in the world. The world had turned more into an outside. It took decades of reconstruction and reintegration into world trade after World War II before German entrepreneurs again moved as easily on the international scene as they had before 1914. A German accent wasn't really a recommendation, and German was no longer a lingua franca among European business, especially after the iron curtain had cut off Germany's privileged markets in east and central Europe. Like the Federal Republic in general, German entrepreneurs had to turn west exclusively. Americanization is the catchword in the discussion about German business culture in the second half of the twentieth century (Berghahn 1986). While there is disagreement about how far this went, there is no doubt that massive American investment in Germany as well as German investment first in western Europe and then overseas very much contributed to English becoming the second working language in most major companies. Since the late 1990s even the minutes of the board of directors of big companies like Deutsche Bank or DaimlerChrysler have been kept in English exclusively.3 Moreover, English was quickly established as the working language in European cooperations from SMEs (small and medium enterprises) to Airbus.

Learning Democracy

The widespread antidemocratic attitude among business elites from imperial to Nazi Germany persisted even through World War II, when German entrepreneurs expected Allied and especially American administrations to provide another stable authoritarian framework for business as usual. It was “a painful learning process” for the German business elite to see in democracy more than just an expedient form of governance to ride out international pressure after two lost wars (Henke 1995, 511). Only slowly and very much helped by a change of generations did German entrepreneurs embrace democratic culture as their authentic self-conception rather than a smart implement of American control. From the late 1950s, ideas of democratization and Americanization went hand in hand (Berghahn 1986). An unquestioned democratic culture was not dominant among big German enterprise before the 1960s. There is agreement in the literature that the sixties and not the end of the war was the watershed in the mentalities of German business. Americanization eventually gave way to a more pluralistic approach, incorporating management models from Japan, intensifying cooperation with business in neighboring countries, and developing a European rather than just a German home base (Kleinschmidt 2002, 395–403; Wengenroth 2007).

Entrepreneurs and Entrepreneurship in the German Innovation System, 1815–2006

Innovativeness is always related to its environment. “The national innovation systems approach stresses that the flows of technology and information among people, enterprises and institutions are key to the innovative process,” in which the key actors are “enterprises, universities and government research institutes” (OECD 1997, 4). What did innovative entrepreneurs in Germany make of the setting in which they found themselves? How did they utilize the institutional and intellectual resources available to them, and how did they cope with the changing rules of the game? And the rules of the game did change. In a first approach one can distinguish three phases after 1815. There was a long first phase of expansion of the German economy and its innovative potential until World War I, during which entrepreneurs in Germany were confronted with predictable forms of change. A second, much shorter, violent, and disruptive phase embraced the two closely related and aggressively fought world wars and their aftermaths, which completely disrupted the earlier, seemingly stable trajectory. In a third phase, a reconstructed and closely monitored market economy in a much smaller West Germany had to find its place on a world market where America had become the undisputable benchmark and technology leader.

Expansion (1815–1914)

EARLY INDUSTRIALIZATION

After the defeat by the Napoleonic armies, Prussia set out on a course of reform to strengthen the country's economy and unleash the productive potential of its trade and infant industries. To promote industry, a new institution, the Preußische Gewerbeförderung, the Prussian institution for the advancement of trades and crafts, was created in 1821. This institution engaged in importing machines and especially machine tools from England, much of it clandestinely and by way of smuggling and industrial espionage. Promising craftsmen could study British machinery or might even get state-sponsored machine tools to copy and learn from. A particularly successful investment of that kind was young August Borsig, who, about three decades after he had received his stipend and fifteen yeas after the beginning of the railway boom, turned out his 500th locomotive. Machine building in Prussia and—not much different in its early state support—in Saxony started by copying and adapting to the requirements of the German market. Machine tools were the most crucial element in this technology transfer from Britain, since unlike any other machine, machine tools were the seed of replication. This, after all, was the reason why their export from Britain, unlike that of steam engines and textile machinery, had been banned into the early 1840s. Local mechanics, like August Borsig, and especially clockmakers of heavy tower clocks were well equipped to turn their expertise in metal casting and metal cutting via the new array of industrial machinery (Paulinyi 1982). Innovativeness came with improving design, setting an early example of German incrementalism. By 1850, ten years after the opening of the first significant railway line in Germany, the German machine industry was capable of turning out all rolling stock for the then most dynamic sector of the economy.

As a number of quantitative studies have conclusively shown, railways and railway construction were the leading sector of German industrialization in the decades after 1840. Railways literally pulled all other industries along, first, by helping to create a financial sector that was capable of turning short-term deposits into longterm investment. State guarantees of minimum interest rates on railway stocks had been instrumental in overcoming the hesitation of investors, and very soon railways were more profitable than other stock. State investment itself was insignificant. Second, railway construction and operation created sufficient domestic demand to allow expanding business in machine building, coal mining, and iron and steel production. Third, railways quickly and significantly brought transport costs down in a country that for geographical reasons could not rely on water transport. By 1900 transport costs on the railways were about a quarter of what they had been half a century earlier (Fremdling 1985; Aubin and Zorn 1976, 563).

The banks had looked at the French Credit Mobilier. The machine builders, as a model, as we have seen via the example of the Prussian Gewerbeförderung, had looked to England. Coal mining was developed using as models mostly Belgian companies that had been working the same deposits further to the west, and iron and steelmaking equally looked to industries in Belgium and in England. The innovativeness of all these partners in the railway business did not reside in their creating something fundamentally new but in doing it in a new environment. In not protecting intellectual property rights—or doing so only reluctantly—and by engaging actively in espionage and illegal imports of high technology of the day, the Prussian government went out of its way to promote technology transfer to the nascent domestic industry. This does not mean that German companies could rely solely on imitation. In the case of the iron industry, iron-makers had to find ways to turn German coal, which was chemically different from English or Belgian coal, into coke, had to learn how to use German ores that had a different set of accompanying minerals, and so forth. Plenty of new knowledge and new skills were generated in that way.

HEAVY INDUSTRIES: INNOVATION IN NEGOTIATED MARKETS

With domestic railway construction peaking in the 1870s, the iron industry, which had entered mass steel production by that time, using the two unprotected steelmaking processes mentioned above, had to look for new outlets for its production. “Overproduction” was the scare of the time and it led to a completely new complex of cartelization, tariff protection, and innovativeness that was to become typical for German heavy industries until the interwar years. Overproduction had mostly arisen from rapidly developing economies of scale in the mass production of steel. Domestic cartels were created and very much supported by creditor banks to protect the majority of companies from going bankrupt (Wengenroth 1994a, 124–26). This did not lead, however, to bank control of the iron and steel industry (Wellhöhner 1989). It was a mutual interest in cartels and tariff protection at a time of crisis, not a policy to promote Finanzkapital in sense of Hilferding, a Marxist economist who eventually became minister of finance in the Weimar Republic. The tariff, meant to protect the home market, was developed into an instrument to protect differential pricing on domestic and export markets. Export dumping was the means to buy peace at home while simultaneously creating an opportunity for the most dynamic entrepreneurs. They ran their plant to full capacity, matching American “hard driving,” and by this means effectively reduced production costs. The surplus above the domestic cartel share was dumped at very low prices—prices well below average production costs—on export markets, driving British companies out of the market (Wengenroth 1994a, chap. 4).

Innovativeness in this setting focused almost completely on cost reduction. With prices and quantities fixed on the domestic market, costs became the one variable that was open to innovative design. Without price competition, companies had to resort to cost competition. Production quantities that were needed to achieve the most effective economies of scale could be guaranteed by exports at dumping prices, around which there was plenty of room for maneuver thanks to cartel provisions. There were two main strategies for cost reduction. One, as already mentioned, was to drive the plant at optimum speed. The second was to enter into vertical integration to circumvent high cartel prices of domestic raw materials, especially coal. Eventually, the most successful German steel barons, like Krupp and Thyssen, would have fully integrated works, from coal and ore mining at the bottom to all lines of finished steel at the top. Their plant, especially that of Thyssen, the most dynamic steel manufacturer in imperial Germany, were models of energy efficiency and byproduct recovery. Internally they were examples of successive decentralization, with a number of “modules” (Fear 2005, 40) operating rather independently from each other. These works would not only be self-sufficient in energy but also sell on the market gas and electricity, both by-products of blast furnace and coke oven operations. They were islands of an extensive, privately planned industrial economy.

By integrating as many steps of production as possible, the interface to the market was minimized while internal technical and organizational complexity grew. These vertically integrated companies, with their heat- and gas-exchange systems covering little “counties,” were dreams of engineering control, largely shut off from disturbing environments. They worked fine under tariff protection, which was the convenient if always a bit precarious arrangement to enable lesser competitors to survive. It did not, however, withstand the storm of a real depression. In the mid- 1920s, with demand very low after the stabilization of the mark and concurrent inflation of the French franc, which closed many export markets and blocked the dumping mechanism, most of Germany's big steel producers—a total of about onehalf of production capacity—ran for cover in a merger of desperation, the Vereinigte Stahlwerke (VSt—United Steelworks). The first strategy of VSt was to lay idle as much capacity as possible and to run the remainder at optimum speed. This scheme, however, quickly ran into limits, as the intricate gas- and heat-exchanges broke down, driving costs up (Reckendrees 2000).

The engineering marvel of “total integration” failed miserably when output could no longer be negotiated. It had no flexibility; it was not made for the vicissitudes of real markets. Eventually, almost in a state of absent-mindedness, the German state took the majority of the stock of VSt, effectively if not intentionally nationalizing the company and with it most of German steel. More than any American reeducation toward competition and free markets, the disaster of VSt was a lesson learned by German entrepreneurs. They would begin to plan for individual competitive companies long before World War II was over. The innovative path toward a technological world of market-avoidance had produced great technologies and singular skills in physically connecting many different production lines, but it would only work in an economically stable environment with steady, moderate growth rates, as had been the case in the pre-1914 years (Wengenroth 1994b).

MECHANICAL INDUSTRIES

For the mechanical industries, American manufacture with interchangeable parts had become a model at about the same time that the leading steel manufacturers took to American “hard driving” of their plant. Especially the display of American machine tools at the Paris exhibition of 1867 and the news about mass production of guns and rifles during the Civil War had generated great interest among the more enterprising manufacturers. The great chance for a decisive leap forward came after the Franco-Prussian War of 1871. The Prussian military was absolutely determined both to equip its infantry with better guns and to acquire modern American gun factories as a backbone of future armament. These factories, bought ready to operate from Pratt & Whitney, making them this company's biggest single contract in its history, were the technological seed opening a new era of German manufacturing. Automatic and semiautomatic machine tools, together with innumerable jigs and gauges costing as much as the machines themselves, were models and blueprints for the modernization of a number of army contractors—very much like the imports of the Gewerbeförderung earlier in the century. The idea was to create a dual-use industry that could quickly turn from sewing-machines to guns. And it worked. The most successful army contractor was the Berlin company Loewe, which, after a short detour into mass-producing sewing machines, replicated American automatic and semiautomatic machine tools, and adapted their design to both the European market and European iron and steel qualities. At the same time, Loewe continued to perfect its plant for gun production. In the 1880s, Loewe, to give just one example, was turning out Smith &Wesson revolvers for the Russian army. And Loewe now was in a position to do for Europe what Pratt & Whitney had done for the Prussian state: offering turn-key workshops for the mass production of small iron and steel components that were widely used for bicycles, sewing-machines, typewriters, and so on (Wengenroth 1996).

THE RISE OF SCIENCE-BASED INDUSTRIES

Chemical Industry

The showcase of German science-based industry was undoubtedly organic chemistry. From the 1880s until well after World War II German companies held a commanding position in most products based on carbon hydrates, especially when it came to high-value products like pharmaceuticals. The success story began with synthetic dyestuffs in the 1880s. Although the first synthetic dyestuffs were created in France and England, the latter in a laboratory set up by a student of the German chemist Liebig, it was German firms, supported by academic chemists from universities and engineers from the polytechnics, that turned synthetic dyestuffs into an industry with a highly methodical and scientific approach. The main strategy was always the same: analyze a natural product and then find ways to synthesize it cheaply from the tar derivatives the heavy industries and gasworks would abundantly supply. The overabundant supply of first-rate human capital for industrial research, plus the additional incentive of not having access to natural resources from colonies, created a situation that proved to be immensely fortunate (Reinhardt 1997). Only the Swiss chemical industry, also with a good supply of academically trained scientists and no colonies, could match the progress of German organic chemistry. It was one of the first examples after the Industrial Revolution when the absence of natural resources proved to be beneficial. Apart from the availability of highly qualified human capital, the German dyestuffs industry benefited from having hit a treasure trove of potential products, and the most innovative entrepreneurs were smart enough to see and fully utilize that potential.

Serendipity had it that hydrocarbons are at the root of three major product families: dyestuffs, synthetic materials, and pharmaceuticals. In looking for one, chemists would inevitably find the others. They just had to find out what the properties of the respective stuff were they had hit upon. This was done by massive testing on a hitherto unprecedented scale by hundreds of professionals in the laboratories of the big three (Hoechst, Bayer, BASF) of the German chemical industry. In the words of Carl Duisberg, head of Bayer, there was “nowhere any trace of a flash of genius” in the labs, just academic toil and screening (van den Belt and Rip 1987, 154). Eventually his company found more than 10,000 synthetic dyestuffs before the eve of World War I, 2,000 of which were marketed. At the same time they had hit on dyestuffs that wouldn't dye but could cure ills. Many twentieth-century drugs are “failed dyes,” Valium being just the most profitable among them. Next to drugs a host of synthetic materials was found “on the way” and gave rise to ever more scrutiny when laboratories were testing newly synthesized chemicals.

Charts of tar-based products show a wide spectrum from explosives to anesthesia, Bakelite, and a number of synthetic dyestuffs and their intermediaries. In protecting processes rather than products the German patent law further stimulated the research drive into ever more fields. It took the German chemical industry's competitors decades and the scrapping of all property rights in the wake of wars slowly to erode the position it had built by the turn of the century. Only with two paradigm shifts in the industry, from coal to oil and from chemical synthesis to biotechnology, did foreign—mostly American—companies draw even with and eventually surpass the “big three,” only two of which are still German with BASF being number one globally, while Hoechst has become part of the French Aventis (Wengenroth 2007).

Electrical Industry

An industry that was almost as successful in making the most of the great pool of talent at the many polytechnics was electrical engineering. This industry was governed by two very different titans of German enterprise, Werner Siemens, who had introduced the telegraph to Germany, and Emil Rathenau, the founder of AEG (Allgemeine Elektrizitätsgesellschaft = General Electric Company). Rathenau had been a restless innovator in his early years. He began his career as a designer and director of a company specialized in small, fairly standardized, and cheaply produced steam engines. This is how he met Siemens, who was looking for small mobile steam engines to drive field generators for army telegraphs. Rathenau sold his stake in the steam engine company just before it went bankrupt in the crisis of the 1870s. Looking for new opportunities and with good reason not to be seen for a while by his erstwhile shareholders, Rathenau, like Loewe whom he knew well, went several times to America to look for new products. From his first journey he returned with automatic machine tools—they were to become the business of Loewe. The next trip brought the Bell telephone and, again, cooperation with Siemens, who would manufacture it. To the dismay of Rathenau, the postmaster general decided that the telephone would fall under the same royal privilege as the telegraph and would run as a state company. Eventually Rathenau was lucky. The next business idea imported from America worked: Edison's electric light. Again, Siemens was the partner to do the manufacturing in the jointly owned “German Edison Company.” The partnership with Siemens proved uneasy, however. Rathenau eventually took most of the business out of this partnership and created AEG (Wengenroth 1990).

In a major crisis soon after the turn of the century, most electric manufacturers went bankrupt when the gap between investment costs and returns from municipalities widened. The outcome on the German market was a duopoly of AEG and Siemens and remained that until the decline of AEG in the 1980s. Here again, basic innovations did not originate in Germany, but German entrepreneurs found ways to accommodate the new technology not only to the German market but to a great number of similar markets in smaller countries and overseas. Through these adaptations and modifications of Edison's electric light system, as through the adaptations of machine tools in the earlier example, it was the German companies that benefited most on export markets from what had been American technology. The solid background of a great number of competitive polytechnics provided the human capital and the research input that was needed to support this aggressive policy. Although it has been debated whether electrical manufacturing was a science-based industry or an industry-based science in Germany, there is agreement that the close and extensive cooperation of manufacturers and polytechnics greatly helped to solve innumerable problems occurring on the way to innovations that eventually created the high reputation for equipment “made in Germany” (König 1996).

UNTERNEHMERGESCHÄFT

With AEG, Rathenau was free to run a more enterprising course, the early pillar of which was the Unternehmergeschäft (entrepreneur business). In the Unternehmergeschäft, AEG would finance the erection of its own electric power systems and eventually sell the plant and the installations to the municipalities. This proved to be immensely successful, since many European municipalities could not or would not finance a major electric power plant. They would, however, grant a concession to AEG or other manufacturers to build the plant and operate it for a number of years, provided it would then fall to the city. The same deal applied to electric streetcars. Wary of privately owned infrastructure, European city councils were more easily convinced to go electric that way. To finance the Unternehmergeschäft, Rathenau and the many followers he had in the electric industry created banks and holding companies in Switzerland and Belgium, countries with a very liberal attitude to such institutions (Liefmann 1913). Soon the Unternehmergeschäft branched out to many overseas countries, with a particular stronghold in South America (Jacob-Wendler 1982). The electric manufacturers thereby created their own market. Not all were as clever as Rathenau and Siemens in keeping control over their huge investments on borrowed money.

NATIONAL NORMS

Ludwig Loewe, like so many other German entrepreneurs and engineers, had made it a routine to go to America frequently to scout the works and exhibitions for new ideas and to invite American engineers to his company in Berlin, which was famously credited in the American Machinist as the “finest American workshop” in Europe. Eventually it was Loewe who saw the great potential of a heavy Norton grinding machine that at the turn of the century had failed to convince American manufacturers. Loewe rested on the strength of his environment. He let one of his directors, the twenty-five-year-old Walter Schlesinger, go to the Berlin polytechnic to conduct research in metal cutting using heavy grinding machines. For the highly gifted young Jewish engineer, an academic distinction was one of the few pathways to be respected in the title-minded imperial society (Ebert and Hausen 1979). The result was the first ever German dissertation in mechanical engineering, the establishment of a “norm factory” on the premises of Loewe, and the beginning of what was to become the greatest export success of German mechanical industry ever, the DIN (Deutsche Industrie Normen)—German industrial norms used by countries around the world, among them more recently the Peoples Republic of China. In creating norms for fits, Schlesinger and his comrades-in-arms—literally, because most breakthroughs happened through World War I—established national norms rather than proprietary factory norms. With national norms, all German industry could participate in decentralized mass production. Products and components designed meeting these norms would always fit together. The test run was arms production in World War I, when a highly decentralized German industry had to turn out components for uniform mass products (Santz 1919; Garbotz 1920). It was another American observer who had quickly identified the synergies between the strength of academic training and systematic approaches to “normalization”: „One meets with some undoubted improvement over American designs, due to characteristic Teutonic thoroughness in reducing all calculations to mathematical certainty“ (Tupper 1911, 1481–82).

For smaller economies like those all over Europe, these national norms were a much better solution than proprietary norms. And as Germany moved ahead in creating a system of norms, other countries did not bother to invent something new but adopted DIN norms and later also their electrical counterpart, VDE norms (VDE = German Association of Electrical Manufacturers). There were very few innovations, if any, that helped German industry better to conquer export markets for mechanical and electrical products. Schlesinger and Loewe together had established this path, and others were quick to follow, seeing that agreeing on a common norm helped German business more than going proprietary. It is no surprise that German industry's tradition of collective action and cooperation was further strengthened by that strategy.

MIDDLE RANGE TECHNOLOGIES

A related strategy of German mechanical engineering was combining the versatility of universal machine tools with features of specialized one-purpose machines, as was developed in the American system of manufacture. While the American original, which was much copied ever since it had been imported after the Franco-German war, was tailor-made for large batch production, the German adaptation was a variety of single-purpose add-ons to a universal machine. This didn't give the same low unit-costs an American workshop turning out thousands of identical parts would provide. But it helped small and medium sized enterprise that was so typical for developing industries and for highly differentiated European markets to benefit to some extent from American principles of mass production without having to undertake an investment in single-purpose machinery that would never pay off (Dornseifer 1995; 1993b, 73-4). This innovation strategy, focusing not so much on fundamental breakthroughs as on adaptation of known principles to specific markets, achieved two things at the same time. It brought cutting-edge technology at competitive costs into the reach of small and medium enterprise (Magnus 1936). And, together with the protection of investment offered by the German industrial norms, this portfolio of highly flexible and adaptable machinery gave German industry a strong position in the many markets where entrepreneurs would import rather than manufacture their production technology. In the 1920s this branch of medium-sized firms supplied a fifth of the world machine exports and had more people employed than the iron and steel industry (Nolan 1994, 149–50). German mechanical industry turned into an opportunity the backwardness vis-à-vis the American system of manufacture that German manufacturing industry shared with so many other countries.

PUBLIC ENTERPRISE

An important group of entrepreneurs in Germany were state servants. While imperial Germany and most of its states had favored private enterprise during industrialization, there were some notable exceptions. In the case of postal services it was a royal prerogative that had been quite unceremoniously inflicted on the Princely Mail of Thurn and Taxis, a Frankfurt-based private mail service operating in Germany and its European neighbors. Thurn and Taxis were pro-Austrian, and when Prussian troops occupied Frankfurt at the end of the Austro-Prussian war of 1866–67 the company had to abandon its business to Prussia and its allies. Ever since, until privatization in 1995, postal services, including telegraph and telephone, were staterun in Germany. With the foundation of the German Empire in 1871 the Reichspost (Imperial Post) was created. Heinrich von Stephan, postmaster general until his death in 1897, was an entrepreneur rather than just an administrator. Son of a tailor and with nine siblings, Stephan was a good example of both upward mobility and nonmonetary rewards. Working his way up the career ladder of the Prussian post, he received an honorary doctorate from the prestigious University of Halle for his scientific publications in 1873, was eventually ennobled in 1885, became a member of the Prussian House of Lords, and was canon secular in the city of Merseburg.4 It had been his memoir to the Prussian court that suggested the forcible takeover of the Princely Mail of Thurn and Taxis as soon as this was militarily feasible.

The growth rate of his business, which eventually included simple banking and savings services, was about ten times the growth rate of the economy. In the 1890s its annual budget was about $100 million and continued to grow. But the Reichspost was never meant to make large profits. Very much to the chagrin of Parliament and with strong support by imperial government, Stephan, a system builder par excellence, plowed back profits and subsidized peripheral regions of the empire through a system of standard rates. Among his many institutional innovations was the General Postal Union created in Switzerland in 1874, which very much simplified international mail services. Only three years after the Franco-Prussian War, Stephan had no qualms about agreeing on French as the working language of the Postal Union (Wengenroth 2000, 104–5).

Another important nationalization of private enterprise took place between 1879 and 1885 when the Prussian state nationalized most of its private railways after Bavaria and Saxony had already consolidated their state railways by acquiring the remaining private companies on their territory. There had been many complaints from trade and industry in the 1870s over widespread corruption, cartels for railway tariffs, and mismanagement among private railways, which were seen to be obstacles to industrial growth. At the end of the nineteenth century about 90 percent of German railways were state-run and highly profitable. Unlike the Reichspost, the Prussian railways, like the other state railways, were major contributors to state revenue. While the postmaster general delivered less than $20 million in 1913, the railways contributed more than $160 million to the state budget. In many years the Prussian railways generated more state revenue than all state taxes combined. Nobody doubted that they were more efficient than their private predecessors, and they were certainly a large improvement in safety and reliability. What on the eve of World War I was the largest single enterprise in the world ruthlessly exploited its monopoly (Wengenroth 2000, 106–7). In contrast to the Reichspost, the Prussian railways had a decentralized structure: at the top was the Prussian ministry of trade, while entrepreneurial activity was mostly concentrated in the regional railway directorates.

Both post and railways continued to be successful enterprises after World War I, although the railways had had a disastrous start when they lost 5,000 locomotives and 150,000 carriages to the Allies. This disaster was turned into an opportunity, however, in that the Reichsbahn, now a single national enterprise instead of a number of state railways, thoroughly modernized and standardized its rolling stock, turning the freshly established national system of norms to its advantage. Between 1924 and 1932 the Reichsbahn could contribute about $1 billion to the reparations account. The combined turnover of both, Reichspost and Reichsbahn, in 1929 peaked at $1.8 billion with a favorable balance of $260 million, which was about equal to the annual dividends of all German joint-stock companies in that year (Wengenroth 2000, 111).

Violence and Stagnation (1914–1955)

WARS AND AUTARCHY

The investment strategy developed in the late nineteenth century by the heavily cartelized and protected heavy industries to build tightly coupled, vertically integrated plants to avoid integration via the market as much as possible, was intensified through wars and autarchy. Germany, which was in no position to safeguard its raw material supplies from a vastly superior British navy, during conflict and in preparing for war turned to processing poor raw materials from its own territory and producing Ersatz to overcome supply shortages by second-rate material. Enormous ingeniousness and innovativeness were invested in autarchy technologies that were dead-ends on free markets and steered much effort away from future competitiveness (Wengenroth 2002).

The strength of the German chemical industry in synthesizing chemical compounds that were found in nature or compounds close to them was greatly in demand when the country went into World War I. Just before the war, Fritz Haber had created a process to synthesize ammonia, by this being able to produce nitrogen, which had mostly been imported from South America before the war and, more important, before the blockade by the British navy. Nitrogen was indispensable for both ammunition and fertilizers. Without Haber's invention, the war would have been over in summer 1915, since Germany would have run out of ammunition. Haber's ammonia synthesis was a classical case of industry-university cooperation. Haber, an entrepreneurial scientist par excellence, designed the process at the university and then went to BASF, taking his process with him. Another product Haber developed was weaponized gas. He himself led the first gas attack of World War I. Since Haber was Jewish, he only had the rank of a Vizewachtmeister (vice-constable). The Prussian army's officer corps had been one of the strongholds of anti-Semitism. All these complications of rank and order notwithstanding, it was Vizewachtmeister Haber who effectively ran the first gas attack and not the colonel officially in charge. Only after the “successful” attack was Haber promoted to the rank of a captain (Szöllösi- Janze 1998, 327–30).

More on the autarchy line like ammonia synthesis were developments of coal hydrogenation that were begun during World War I and completed with the advent of World War II to produce both gasoline and rubber from domestic coal. The R & D strategy was not so different from chemical synthesis in the prewar years, but it steered away from international markets and considerations of competitiveness of the new production lines. What was quite rational, given the resource poverty of Germany and its inability to break a British naval blockade, slowly turned into a new paradigm of a self-sufficient Germany that would not have to negotiate its way on international markets but could retreat into some self-designed cage. While before World War I chemical synthesis was a way to beat prices and quality of products based on natural resources, after the war and very much in the Nazi years it became a gospel of independence for conducting wars (Petzina 1968). A great share of innovative capacity was thus diverted toward a long-term economic cul-de-sac.

The German chemical industry—and to some extent also the steel industry, which was forced to process poor domestic ore—became world leaders for products and processes nobody else wanted. Scientific and technological excellence focused on products without markets and without a known future. Talent was wasted on, or rather sacrificed to, unaccomplishable political ambition. Add to this the selfdecapitation of the German innovation system through the Nazis' policies and its aftereffects as described earlier and you get a picture of self-destruction on a grand scale. This is not to argue that Germany could still be something like the world's science and technology leader. Given the size of the economies and their respective productivities it was inevitable that the United States would sooner or later assume that position. But German politics in and between the world wars, in particular anti-Semitism, contributed substantially to hasten that transition. Unabated innovativeness in these years too often followed a disastrous track that took German industry away from international competitiveness. Without a sustainable political perspective, which given the size and geopolitical situation of Germany could only have been peaceful, innovation following military short-term objectives, in the long run neutralized much of the country's economic and technological potential.

STIFLED MARKETING INNOVATIONS

While innovation in industry suffered from being directed toward autarchy and Ersatz, especially during the Nazi years, innovation in marketing and retailing was stifled from the beginning. Because of its focus on investment and intermediary goods, German enterprise had been in a comparatively weak position in marketing in the early twentieth century. In 1907 only twenty-one of the 100 largest German industrial corporations had a bona-fide marketing organization, while forty-nine of the top-100 corporations sold their product exclusively via cartel syndicates (Dornseifer 1993b, 75). This tradition was turned into an aggressive policy and ideology by the Nazis, who, before their rise to power, had promised to expropriate big department stores, which were reviled as manifestations of Jewish and plutocratic exploitation of both German workers and German shopkeepers. While expropriation did not occur—with the important exception of “aryanization” of Jewish property—the Nazis did place a ban on further retail outlets and controlled concessions for retailing a few weeks after Hitler's rise to power. And as they had introduced mandatory cartels in industry, they also introduced enforceable resale price maintenance and thereby effectively abolished price competition. This rule was in effect until January 1974 and kept productivity in retailing low (Wengenroth 1999, 122). It was large, familyowned mail-order firms with good access to nonbranded imported goods that managed to bypass this stifling situation in the fifties and sixties, eventually putting protected retailing under such pressure that price regulation was abandoned. Ironically, the large mail-order companies were among the first to suffer from price deregulation when their price-quality ratio was matched by department stores and specialized dealers. Only a few general mail-order firms managed to survive, but the leader in the field, Otto-Group, which includes a small tourism segment and financial services for consumers with a turnover of more than €15 billion, is today the largest mail-order company in the world (Geschäftsbericht Otto-Group 2006–7). With no limit on the number of retail outlets, retail chains at long last began to flourish in Germany. It is telling of the innovative potential of German retailing that once it was freed from anticompetitive regulations, Germany is the only major market where Wal-Mart failed. After almost a decade of heavy losses amounting to more than €3 billion, Wal-Mart wound up its German business in 2006 and sold most of its 85 shopping centers to a German competitor. At the same time, the owners of the leading German retailer Aldi have been quite successful with their Trader Joe's chain in America.5

Finding Its Place (1955–2007)

RECONSTRUCTION LEGACY: LEADING INCREMENTALISTS

After the autarchic interlude of the years between the world wars, German business in the West—that in the East was quickly nationalized—had to adapt to yet another set of rules, opportunities, and limitations. Autarchy was definitely out. Imported oil replaced domestic coal as the main source of energy and as the main raw material for the chemical industry. World markets were accessible for both imports and exports. Cartels were banned as of 1957. European integration already began in the early 1950s with the formation of the European Community for Steel and Coal. Because of wartime destruction, the capital stock was comparatively young. Reconstruction demand was enormous. On the downside were Allied restrictions on a number of cutting-edge technologies until 1955, which made Germany fall further behind in research for knowledge-intensive products, although they had little effect on industrial production proper since industry was still busy reconstructing (Neebe 1989, 51–52; Abelshauser 2004, 229).

In this situation German companies quite rationally focused on perfecting existing technologies for the purpose of reconstruction at home and supplying export markets with the wide range of not-so-high-tech products like cars, multipurpose machine tools, standard chemical products, and so on. Werner Abelshauser has forcefully argued that reconstruction has been the dominating mode of the German economy in the twentieth century: reconstruction after World War I, extensive reconstruction after World War II, and reconstruction of the ex-GDR after unification in 1990 (Abelshauser 2001). Reconstruction is not technologically daring, since the technologies are all in place and well known. The great opportunity of this reconstruction mode is, however, to become a superior debugger of new technology, the best incremental innovator around. Looking at Germany's export portfolio, it becomes clear that this is very much what happened. Germany is excellent in technologyintensive products that are not cutting-edge, with automobiles being the current top-runner, while German information technology is in a rather modest position (Abelshauser 2003, 185; BMBF 2005, 48–54). Biotechnology is another example. At the first glance German companies are doing quite respectably, but their strength is in so-called platform technologies, that is, the toolbox or machine tools of biotech. When it comes to substances that go into clinical testing, Germany is far behind Switzerland.

Reconstruction has conditioned German industries by creating many opportunities and, most important, career patterns for its scientific and technological elite. The great export success that came out of reconstruction kept German business in industry and prolonged the dominance of industrial employment in comparison to other European countries and certainly in comparison to the United States. There is great concern among leaders in government and business that Germany may fall behind and fail to command new technologies. As the most recent data on Germany's competitiveness shows, however, there is little reason to be worried in the overall picture. In comparison with its main competitors, Germany's balance of trade in R & D–intensive goods is very good.

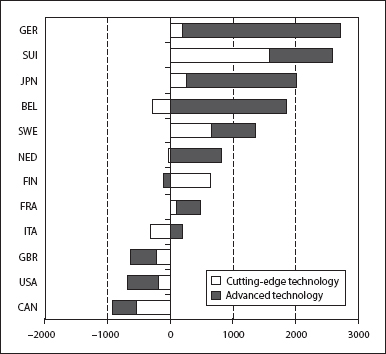

The strength of Germany's position lies overwhelmingly in advanced technologies, not so much in cutting-edge technologies. This comparison confirms the cultural imprint in the German innovation system of reconstruction and incremental innovations—a trait it shares with Japan. But even when it comes to cutting-edge technologies, Germany's balance of trade is still positive, illustrating that the fast follower strategy is working, not in fields like information and communication technology, but certainly on average over all branches of industry. The backbone of Germany's great export successes in Schumpeterian goods is not the heroic entrepreneur who is ushering a new basic innovation to the world but the shrewd manager of continuous novelty that keeps his company in business. Perpetual incremental innovations and close market observation are the foundations for the strong position of German manufacturers on world markets.

Figure 10.7. Balance of Trade per Head with R&D-Intensive Goods in 2004 (in US$). (Source: Federal Ministry of Education and Research, 2007 Report on the Technological Performance of Germany, Summary, 9.)

BUYING INNOVATIVENESS