Chapter 2

Neo-Babylonian Entrepreneurs

THE NEO-BABYLONIAN EMPIRE under the so-called Chaldaean rulers1 lasted nearly a century, from 626 to 539 BC. It ended when Cyrus the Great conquered Babylonia and made it part of the much larger Achaemenid Persian empire. Its center and power base was southern Mesopotamia, from where it controlled large parts of the Near East. Babylon, its capital, was situated on one branch of the Euphrates River, circa 75 km to the south of the modern-day Iraqi capital Baghdad.

From 626 BC on Nabopolassar gradually had seized and consolidated control over Babylonia until his troops, with help by Median allies, finally defeated Assyria and destroyed its capital Nineveh in 612 BC. Babylon then became the capital of a large empire, reversing the effects of its prior military devastation and subjugation under Assyrian rule. Tribute flowed into it rather than being drained from it.

Nabopolassar's famous successors Nebuchadnezzar and Nabonidus used these resources to finance large-scale building projects, such as renewing, renovating, and expanding temples and palaces, extending city fortifications, and expanding the irrigation system. Nebuchadnezzar followed the Assyrian policy of relocating substantial parts of the local population from conquered regions by settling them in Babylonia.2 This helped stimulate economic growth under relatively peaceful domestic conditions resulting in sustained population growth and relative prosperity.

Cyrus' conquest in 538 BC marked the end of Babylonia's sovereignty and therefore a hiatus in its political history, but it did not cause a break in Babylonian administrative or legal institutions. The transition was made smooth by the early imperial Persian policy of relying as much as possible on existing legal and economic structures in the conquered areas.3 The Achaemenids4 typically superimposed their own administrative layer on preexisting structures. With its much larger scope, their empire afforded new business opportunities, although Babylon no longer was the center of power; the royal court resided elsewhere.

Babylonia's economic capacities were a major asset to the Persians, providing a third of the empire's tribute, as Herodotus reports.5 Resources thus were drained, as had been the case under Assyrian rule, but economic growth helped soften the impact.6 Despite Babylonia's wealth, privileges and relatively independent local power, the yoke of the Persian rule was increasingly resented. Attempts to cast it off were triggered whenever the succession to the Persian throne was fought over. When political unrest ensued after the death of Darius in 486 BC, two pretenders (presumably from prominent Babylonian families and well connected with the local Persian administration) temporarily gained power over northern Babylonia. This fight prompted the victorious Xerxes to punish their backers and reorganize the way in which Babylonia was governed. As a result, many archives of the traditionally leading Babylonian families do not survive beyond his second regnal year.7

Subsequent sources, such as the business archive of the Murašû family from Nippur in the fifth and early fourth centuries, portray a different kind of entrepreneurial activity as compared to the sixth century, organized around the administration of large Babylonian estates held by members of the Persian aristocracy. As a result we have a fairly homogeneous picture for a period of over 120 years or five generations, until around 485 BC. Rich sources attest to economic continuity through the dynastic change, as well as a continuity of administrative and legal institutions. The subsequent period is less well documented—and by different types of sources—indicating that more than merely minor details have changed.

Periodization in terms of broad political history thus will not do justice to the socioeconomic dynamics at work. In the absence of a more accurate terminology—and to avoid long hyphenated terms, hybrids, or acronyms—the term Neo-Babylonian (unless applied to the empire as such) in the course of this study will tacitly include the first decades of Achaemenid rule (until about 485 BC) as well as the preceding period of the Neo-Babylonian empire (626–539 BC).

Primary information about Neo-Babylonian economic activity comes from business records in Akkadian, a now defunct Semitic language related to Hebrew, Aramaic, and Arabic. It was written in cuneiform script on clay tablets, created by pressing a writing implement into the wet medium in numerous combinations of wedge-shaped impressions. Tablet shapes and sizes vary, depending on their purpose. The majority of Neo-Babylonian contracts fit in the palm of a hand, with fifteen to twenty-five lines of text. Because clay is a durable material, tablets easily can survive millennia once they are buried in the ground, be it accidentally or on purpose. Museums around the world house nearly 100,000 such tablets and fragments from the Neo-Babylonian period alone; about 16,000 are published.8 Most of them were dug up by local people or licensed excavators in the late 1800s, before controlled excavations by modern standards began.

These Neo-Babylonian tablets predominantly come from two temple archives (Uruk to the south and Sippar to the north of Babylon) and from private archives of some well-to-do urban families and entrepreneurs from several places. Only a few remnants of the royal archives have come to light so far, thus inevitably biasing our view of this period.9

The last two decades have seen a surge in Neo-Babylonian archival studies with dozens of small- to medium-size private archives studied and published, or at least made accessible thanks to a more generous attitude of museums granting access to their materials. Scholarly effort has resulted in the publication of new source material, leading to a new level of sophistication in interpreting these sources.

Our discussion will focus on the activities of the Egibi family, which left the largest private archive, containing more than 2,000 tablets (including fragments and duplicates) from five generations covering nearly the whole time span under discussion.10 To be sure, an average between one and two records per month seems meager as compared to the legacy of one single fourteenth-century Italian merchant from Prato, of about 150,000 papers in total.11 Even if the Egibis had generated only one-tenth of this amount, our known records would represent such a small fraction as to fall below the margin of significance. To make matters worse, the wording of cuneiform tablets is notoriously formulaic and terse, revealing mere bare-bone facts without any hints at the intentions or motives of the parties involved and rarely including descriptions of previous proceedings. We therefore only get glimpses and have to rely on a few exceptionally well-documented transactions as explanatory models where the evidence is sketchy.

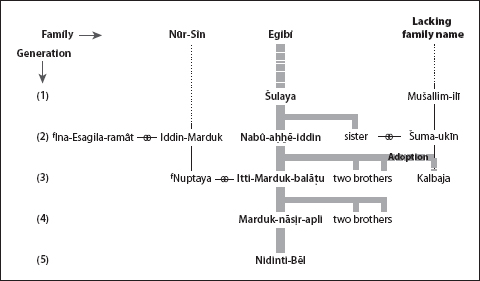

Figure 2.1

Nevertheless this archive reveals much about Neo-Babylonian entrepreneurs and their activities, involving commodity trade, food processing, agrarian credit, and tax farming. On the one hand it serves as a key to understanding other, even more tersely documented archives. On the other hand, some smaller archives elaborate on details that are spelled out less clearly in the Egibi tablets and otherwise would remain obscure.

The Neo-Babylonian Economy12

Natural Conditions

Southern Mesopotamia is an alluvial plain with limited natural resources. It lacks metal deposits, stone, and hardwood suitable for building material, and therefore is completely dependent on raw-material imports. Although the soil is fertile, average rainfall cannot sustain regular crops. The Euphrates and Tigris carry abundant waters for irrigation, but they tend to flood their plains and—unlike the Nile in Egypt—do so when water is least needed: at grain harvest time. Irrigation therefore is a precondition for farming in southern Mesopotamia. It requires a large-scale and sophisticated system of dams, dikes, and sluices both to supply water and to protect the fields from floods. Because the rivers also carry large amounts of silt, these structures need constant supervision and regular maintenance work. With irrigation in place, grain yields can reach proverbial abundance, while water-logged areas of low ground unsuitable for tilling or gardening yield fish and fowl. The alluvial plains are surrounded by steppe land and mountain ranges providing pasture.

The Large Institutions

The crown. The royal administration is not well documented, as only minuscule remnants of the central archives have come to light so far, and provincial administrative archives are lacking. Therefore most of what we know stems from the interface of the royal administration with temples or private individuals.

The king as the single most important landowner controlled large domains all over Babylonia. Other land was held by members of the royal family (e.g., a distinct “house of the crown prince” is known from cuneiform sources)13 and high officials, such as the royal treasurer.14 We can assume that the management of large estates was organized in a similar way to that of temple land described below. Large tracts of land, especially newly claimed areas along the canals, were parceled out to settle diverse population groups as small landholders in return for military service.

The royal administration needed managers to oversee domain lands, to collect taxes and user fees for irrigation, canal transport, and other public infrastructure, and to organize and supervise the corvée, a duty on landowners to provide labor for public projects. This involved provisioning a widening range of forced labor as well as free hired workers who, temporarily or permanently, needed to be fed and supported. Distribution, marketing, and conversion of crops into money equivalents offered major opportunities for enterprise. This required the creation of synergies to facilitate the payment of taxes and fees to the palace. A complex set of relationships developed among the royal, temple, and city administrations, involving large movements of commodities and personnel.

Temples as landholders. Although most temple land was in the vicinity of the cities, some was more outlying, and of diverse quality. Efficient agriculture was possible only along the irrigation canals. Digging and maintaining them was a royal task, and the temples provided manpower and resources to build and maintain infrastructure such as watercourses, dams, locks, and roads. Land was abundant, but the temples were short of people and draft animals to cultivate it.

Much temple land was worked by unfree dependent personnel (oblates).15 Such temple farmers typically were organized in plow teams based on extended family groups for grain farming, but they often were given larger work assignments than they were able to till. Temples also employed tenants on a sharecropping basis, with the portion of the harvest to be delivered depending on the quality of the property.16 Eventually, to increase productivity and achieve a stable income, temples introduced rent farmers, who would take on part or all of the temples’ grain fields or date orchards, including personnel and equipment, in exchange for a fixed delivery quota of commodities and cash.17 On the one hand, temples introduced certain incentives more beneficial than usual to the rent farmer, expecting him not only to contribute a considerable amount of time and effort, but also to invest his personal means in desperately needed equipment, and therefore taking considerable personal risk. On the other hand, temples had to make sure that he would not use such arrangements to their detriment. This was a difficult balance to maintain.

It is far from obvious whether such seemingly entrepreneurial activity always was undertaken voluntarily. In ancient Greece, for example, the wealthiest citizens were subject to special fiscal burdens such as the trierarchy (equipment and maintenance of a battleship), to finance the staging of dramatic choruses and other expensive civic duties. The tendency seems to have been for most of these individuals to use this tax as a vehicle for prestige rather than seeking to make money of it. Rostovtzeff has described this problem in late Roman time.18

This raises the question of whether Babylonian rent farmers were always eager participants or had to be pushed into these arrangements. The records disclose that even temple officials doing tasks within their normal “scope of employment” often were held personally liable for accidents or shortfalls that occurred. Many examples exist of people compelled to sell assets to the temple in lieu of their backlogs due for barley, dates, sheep, or wool deliveries. Such deficits could be considerable, indicating that these temple debtors were not small farmers or shepherds but major players.

In one case a notorious entrepreneurial temple official named Gimillu either refused to accept or returned a rent-farming license because an insufficient inventory of draft animals and personnel for seed plowing came with it.19 Someone else eventually took up the license, but only after having negotiated for twice the amount of draft animals so as to make the arrangement more profitable. In another situation a rent farmer returned his rent-farming license to the temple authorities because he had substantial arrears that he clearly had difficulty meeting, and therefore he felt he no longer could afford to continue the venture.20 We have little way of knowing whether his backlog (and those of other rent farmers) came from especially difficult years with a poor harvest, or whether rent farmers generally worked on tight margins. In other words, we do not know whether such backlogs were accidental and occasional, or systematic and regular.

One might postulate that temple authorities used debts arising from such shortfalls as a way to keep certain families from growing too rich and powerful, much as kings attempted to keep the temples’ power in check by imposing extra duties on special occasions. Allowing entrepreneurs to accumulate a large backlog may also have constituted a capital infusion, increasing the rent farmer's working capital by letting him use the commodities or silver owed for other business. Temples in any event were always crucial credit institutions in the ancient Near East.21 But to understand the exact meaning of these large backlogs, each case needs to be assessed individually, where the context permits.

Babylonia's growing population, its incorporation into the much larger Persian Empire, and its heavier tax duties called for intensified agricultural activity. Temples responded by moving away from subsistence farming, increasingly focusing on cash crops, and delegating more tasks to entrepreneurs, who either came from the rank and file of temple officials, or were outsiders, much in the vein of modern outsourcing practices.

Animal husbandry was of special importance in the south. In Uruk raising animals was the main cash crop.22 Herds were entrusted to shepherds, who might be temple dependents or independent contractors. Temple sheep and goats would roam freely in the steppe and be driven large distances from one season to the next, being brought back at shearing time. Shepherds had to account for their flocks and deliver a specified quota of lambs for sacrificial purposes, and hides and wool to be processed in the temple workshops.

Dairy products were of minor importance because the sheep and goats were unavailable most of the year. Cattle were difficult to maintain and feed over the summer. As a result, they were a scarce resource and hence of eminent importance to the temple administration. The major use of cows and oxen was as draft animals for plowing.

The swampy areas unsuitable for tilling or gardening provided fish and fowl. In those areas under temple authority, fishing and fowling were done by temple personnel; the involvement of outside entrepreneurs is not attested so far. The temples tried to control access to these resources within their domains by licensing systems.23

Temples and their cities. Southern Mesopotamia's temples were institutions of long tradition as vital economic centers, not just cultic entities. At the very least they were in charge of the implements and services required for the care of the gods, maintenance of the temple site, and support and care of its personnel. In addition to providing for the religious needs of the community by housing, feeding, clothing, and maintaining the gods, the temples controlled vast amounts of land and personnel. As a result, temples and their cities formed a symbiotic unit: Cities thrived around the cultic center, and the temple in turn needed the city and its region for support.

The prebendary system. Prebends were entitlements to shares in the temple revenue in return for priestly services and professional work required for the cult. Prebendaries prepared and served ceremonial meals, created and mended cultic garments, cleaned, dressed, and moved around the cult statues, performed rituals, and maintained the inner sanctuary. These tasks not only required certain skills, but the status of a person was important in the sense of his being fit for his particular service, that is, being “pure” in a cultic sense. Thus many craftsmen working for the temple were prebend holders, not dependents or slaves. Prebendaries represented society's free, skilled urban elite, and the prebendary system integrated these oldest and most important local families with the temple.

Remuneration for prebendary service usually comprised commodities such as barley, dates, and beer, as well as leftovers of the meals of the gods, and thus generated a steady and dependable income stream. Such offices originally were associated with certain families and were inheritable. Duties were broken down into monthly and daily units, and in the process of inheritance divisions ran even further to fractions of days.

Enterprise versus Rival Avenues to Wealth: Opportunities and Costs

Economic attitudes and mentalities of the propertied urban classes in Babylonia can be described in terms of two basic (although necessarily idealized) models: a rentier type and an entrepreneur type.24 Rentiers seek to obtain a reliable income from mostly inherited positions and resources with little risk, by exploiting prebends and landed property. Entrepreneurs tend to engage in highly profitable but also risky venture businesses in a competitive environment.

Many families linked with the temple through prebendary duties and entitlements had a rentier attitude, being the civil servants of the ancient world. Their office was hereditary and although prebends became tradable in time, only certain individuals could perform the core duties in the inner sanctuary. This meant that prebendaries were indispensable, but were restricted in assigning such duties to anyone but their colleagues. But although such offices were not in and of themselves key entrepreneurial situations, some did provide opportunities for enterprise, especially those involving food preparation.

For example, prebend holders could have their slaves perform the prebendary task for them, so long as it did not require a certain status, such as in the direct presentation and care of the gods. This freed up the prebend holder for other gainful activity. Ownership and the service could be bifurcated by sophisticated business contracts for prebendaries outsourcing services for payment of a share in the prebendary income.

The commercialization of prebends made some more desirable than others. Those with long duties and no chance to delegate them might entail prestige, but were a burden from an economic rationale by preventing their holders from more profitable activity. This is indicated by one record where a father urges his youngest son (not the eldest!) to perform his duties as a temple singer and take care of him. In exchange, the father grants this son an extra share in the inheritance. Even if this mainly was meant to reward him for caring for his elderly father, it shows that this prebend cannot have been much of an asset.

During the Neo-Babylonian period a polarization among the traditional urban propertied classes can be observed, as their wealth declined in relative terms, unless they embraced enterprise. The economic potential must have been enormous, although not for all of them: some entrepreneurs went bankrupt. But one example shows that prior to this they had amassed large real estate in a very short time.25

From the city of Borsippa a group of private archives of traditional temple-related families indicates that while some used their position and income to become entrepreneurs, others did not.26 No clear-cut pattern emerges to show which course prebend holders might take. There probably was a special incentive for younger sons who inherited very little to become entrepreneurs. But that route took a robust mental disposition, good health, and possibly a business drive that not everyone had.

The Status of Entrepreneurs

The historical record makes it clear that entrepreneurial activity was socially rewarded, not considered beneath anyone's social status. There is no indication that enterprise was considered “dirty business” or something to be delegated to an underling as in Roman times. A temple's rent farmer often came from the ranks of its officeholders or prebendaries. But in general relatively few entrepreneurs came from well-established urban families already endowed with wealth, offices, and good connections.

Of those who did, our records unfortunately do not indicate just how these families rose to their level of fortune and influence, because they already were important by the time our textual evidence resumes at the beginning of the sixth century BC after centuries of extremely sparse documentation. We find members of these families as prebendaries or in the higher echelon of the temples for several generations prior to the business transactions documented in our records. One such example comes from the Ē iru family: By the time of king Neriglissar one of their members held a butcher's prebend at the main temple, and was married to the daughter of a royal judge, but at the same time was involved in a venture business.27

iru family: By the time of king Neriglissar one of their members held a butcher's prebend at the main temple, and was married to the daughter of a royal judge, but at the same time was involved in a venture business.27

Belonging to an important family—however loosely connected—certainly helped in developing business contacts and prospects. But not all branches of these families were rich and influential. For instance, by the end of the seventh century the Egibi family had firmly established itself in several Babylonian cities, holding both prebends and offices. But the Babylon branch that left the impressive five-generation archive rose from humble beginnings, initially owning neither real estate nor prebends.

The majority of entrepreneurs seem to have been ambitious social climbers. Characteristically, they were men without a family name; that is, they did not belong to the urban establishment. Many made their mark within the royal administration or developed significant links to it. As soon as they achieved some measure of financial success, they sought to affiliate themselves with influential families, much as ambitious eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europeans married into less glamorous branches of noble families. For instance, Itti-Šamaš-balā u from Larsa, an entrepreneur “of no name,” engaged in tax farming, agricultural contracting, and presumably trading, married his daughter into a well-known prebendary family from Larsa.28 Marriage links thus helped to achieve status and widen one's access to financial opportunities.

u from Larsa, an entrepreneur “of no name,” engaged in tax farming, agricultural contracting, and presumably trading, married his daughter into a well-known prebendary family from Larsa.28 Marriage links thus helped to achieve status and widen one's access to financial opportunities.

Marriage and entrepreneurial strategy. Advancing business connections through marriage has been a constant for most of recorded history. Certainly in the case of the Egibis, this can be demonstrated by their marriage patterns. In the earliest instance we find a daughter married to a man of some means, but without a family name. He did business with his brother-in-law and seems to have had good connections to, or even a position in the royal administration. This marriage link helps explain some aspects of the Egibi's takeoff, whose early stages are largely undocumented. The Egibi brother-in-law claims to have taught his sororal nephew to read and write cuneiform among other skills, and later adopted him, but without granting him an inheritance share beside his three natural sons. This indicates that the purpose of the sister's marriage was to advance the Egibis' business, while the adoption served to mend her son's handicap of being “of no name” as a result of her marriage.

In the following generations the eldest sons married upward, to women whose fathers were of “good” families, had good connections, and provided rich dowries. By contrast, their daughters were married off to business partners with dowries that typically cost only a fraction of what their eldest sons received, reflecting the Egibis' superior status in relation to these in-laws.29

Reputation of lenders. Creditors have a poor reputation in ancient societies in general, as can be seen from biblical sources. We know little, however, about the social standing of creditors in the Neo-Babylonian period. Our terse records generally disclose no information about emotional attitudes toward creditors. Literary sources occasionally urge creditors to be kind to their debtors. We also have a tablet where a creditor is said to have taken mercy upon his debtor.30

The Entrepreneur's Activities

Several areas of entrepreneurial activity are significant in addition to the rent farming discussed above.

Agricultural enterprise and changing land use. Throughout antiquity a person's landownership was the criterion on which his political, fiscal, and social status was based. Land provided for a family's basic self-sufficiency and supported dependents and clients. What was true of most Roman traders—that as soon as they had made money, they would put it into land as a prestige good—also applies to the Neo-Babylonian period.

The Egibis invested their business profits in farmland and rented it out on a sharecropping basis. Their perspective was long term. For instance, their leasing arrangements gave tenants an economic motive to invest in cultivating more capital-intensive crops, shifting from grain to dates. In return for planting date palms, the Egibis allowed their tenants to pay little rent in the early years, foregoing short-term grain rent in order to obtain higher long-term returns from date trees, which take several years to mature and yield a crop. They also require good irrigation and maintenance, and thus can be grown only in areas close to a water supply.

Over the course of three Egibi generations, date cultivation on one specific plot along the New Canal increased from just one-thirtieth to one-quarter of the terrain.31 Much of the land beyond the orchard was suitable for grain, but the part furthest from the canal could not be reached by irrigation. Therefore the tenant was granted especially favorable terms if he would cultivate and water it by bucket.

Niche products. Specialization on a niche product was the key to success for Iddin-Marduk from the Nūr-Sîn family. He focused on onions, which were grown as a by-product alongside the canals. Shipment and distribution certainly required more effort as compared to the same value in grain or dates, but his strategy worked.

Transport and marketing opportunities. There is a tendency to think of entrepreneurs primarily as promoting new industrial technologies. But transportation and marketing have been equally important throughout history (e.g., most recently the Walton family's Wal-Mart stores). In the sixth century BC, major opportunities for enterprise lay in organizing the flow of commodities and payments between cultivators and large institutions.32 Managers had to establish market relations among the rural areas where cultivators had to pay rent, taxes, and fees for irrigation and other necessities, the urban areas where commodities were needed, and the temple and royal institutions that needed cash or bulk deliveries to support their personnel.

The problem was that tenants and owners of small plots had limited means to ship their crops to the cities and sell them there. The key to linking these spheres was to develop arrangements to collect and ship crops from the countryside to urban consumers, palace dependents, the army, and the temple. Contracts demanding delivery in kind suited the needs of rural farmers as the contracts guaranteed that their crops would be accepted as money equivalent. The traditional Mesopotamian practice was to draw up debt contracts to deliver a given volume of crops at harvest time, in payment for money advanced for seed or draft animals, fees for irrigation water, kindred taxes, or similar items. In this respect early enterprise benefited from arbitrage opportunities associated with creating an articulated system of market relations that helped stimulate market-oriented production above the subsistence level. Almost from the outset, quite modern practices emerged as part of this system.

Tax farming. Tax farming is an arrangement whereby an individual undertakes to collect the taxes due from a given region, in exchange for paying a lump sum to the institution entitled to extract them. The amount is based on the expected tax revenues from that area. Tax farmers make their money by the margin of the collection over payment, and the ancillary lending opportunities that usually go with this activity—most notoriously, rural usury to cultivators who lack the ready cash to pay on the spot.

A high rate of collection was the tax farmer's chief goal, and the business incentive that drove the enterprise. Such activity has the danger of being corrosive unless it is accomplished in a way that sustains the tax base and leads to higher or more efficient production. Tax farming in the ancient Near East could have a positive effect when linked to transport and marketing opportunities.

One of the major problems for small producers was that taxes were increasingly payable in money rather than commodities. Given the limited marketing possibilities in more remote regions, farmers were burdened with produce they could not sell. The Neo-Babylonian tax farmer often established himself as the go-between, accepting commodities for the tax payment from the small rural cultivator, converting the crops to cash through transport and sale, thereby linking the producer and consumer, and then delivering the tax money to the crown. This stimulated market production by linking the producer and consumer and by organizing transport. The tax farmer made his profit in two ways: first, by collecting taxes in excess of what he paid the state, and second, by marketing the crops to consumers to raise the money. An increasing number of people lived in cities and hence had to buy commodities. Intermediaries therefore became critical to a well-functioning economy.

The Egibi family focused their tax-farming business in rural areas along the canals, hiring boats and boatmen to transport goods. Landowners, including the temples, had to pay specific rates to maintain the canals and irrigation system. Establishing contacts with the local official responsible for maintaining the canals and collecting fees from their users, the Egibis supplied him with money to pay the palace in return for the right to extract these fees in kind. They then would establish lending, crop-purchase, and delivery arrangements (all of which were drawn up as debt contracts) that called for cultivators to bring their crops to loading sites along the canal by a specific date as tax payment. Boats were scheduled to deliver the harvest in Babylon, and if the crop was not delivered at the canal by the specified date, the debtor-cultivator was obliged to deliver it in Babylon at his own expense. This tax-farming system enabled the Egibis to transport their crops to Babylon for a flat payment to the local canal official rather than having to pay the retail rate for individual deliveries.

While the Egibis increased access to commodities for trade, their effective control over such toll-collecting points enabled them to obtain a major part of their profit margin at the disadvantage of competitors, much in the way that John D. Rockefeller built up his Standard Oil monopoly by negotiating favorable freight rates with the railroads. Tax farming probably was not their main business purpose, but dovetailed efficiently with other aspects of their commodity trade. Once they had built up a strong shipping, storage, and food-processing network, they had an interest in keeping the supply moving. Whether tax farming was the primary or a secondary profit motive, the family fit into the tax system as intermediaries, advancing money to pay royal taxes against an equivalent amount in the form of crops, spurring agricultural and consumer activity while enlarging their profit margin through market control.

The family appears to have maintained its position as tax farmers even in periods of dynastic change, for example, from Nabonidus to Cyrus (539 BC). To preserve their role, Itti-Marduk-balā u journeyed to the Persian court and sought out other high-ranking Babylonians, evidently to befriend the officials responsible for administering taxes under Persia's empire. The result was that when the Persians took over the Babylonian tax system, they delegated responsibility to local officials and businessmen such as the Egibis and other important Babylonian families who knew how the system functioned.

u journeyed to the Persian court and sought out other high-ranking Babylonians, evidently to befriend the officials responsible for administering taxes under Persia's empire. The result was that when the Persians took over the Babylonian tax system, they delegated responsibility to local officials and businessmen such as the Egibis and other important Babylonian families who knew how the system functioned.

Lending activities. Individuals borrowed money for a broad number of reasons. The less affluent, of course, often borrowed money to cover their subsistence expenses as long as they had some assets that could be used for collateral. When private individuals borrowed, it generally was to pay taxes or to bridge temporary shortfalls. They also might borrow money to pay a hireling to perform their military or corvée service.

Entrepreneurs borrowed to increase liquid capital, raw materials, equipment, personnel—and, in the case of farmers, seed. But unlike the modern world, we find no cases of buying houses or arable fields on credit. There was no mortgage market and hence no financial inflation of property prices A Neo-Babylonian entrepreneur could raise the price of real estate only by actively improving the land, for example, by putting buildings or dwellings on urban plots or planting date palms on irrigated land.

Food processing, distribution, and marketing. Commodity traders tended naturally to extend their activities to processing and distribution down the line to consumers. For example, date traders might have dependents who brewed date beer.33 The result was an increasing degree of vertical integration.

Textile production. Textiles were a major Mesopotamian export. The Egibis, or at least their relatives, were involved in this trade. Documents show that they bought the wool income of Belshazzar, the crown prince of Nabonidus, enabling them to participate in textile production and export.

The Entrepreneurial Use of Slaves

Slave labor is expensive as compared to free labor, unless the supply is so abundant as to keep replacement costs low.34 Many Roman slave-owners worked their slaves to death at an early age, but such a practice could be sustained only for a limited period of time. Neo-Babylonian slaves were precious commodities, not easily replenished, and sold for an equivalent of several years' income of a hired worker. They might originate in foreign lands as war captives or through slave trade. Exposed children or those sold by their parents could be brought up as slaves. House-born slaves also were utilized or traded. Slave women typically were given as a dowry to help daughters in the household and in rearing their children. Slaves had to be fed and clothed, which was not cheap.

It made economic sense to raise the value of slaves by training them in professions and renting them out. This is an early example of “human capital,” although it took the form of a return on an investment by the owner rather than by the individual being educated. Family members often assigned administrative duties to slaves who showed good business ability. This involved employing them in mercantile trade or delegating management of the family business to them.

Few families voluntarily sold their slaves. Sales usually were preceded by pledging the slave for debt. Slave families typically were sold together, and children were separated from their mother only when they had reached working age. Personal treatment and living conditions certainly were harsh for most of them, but there was no Babylonian anticipation of Rome's slave-stocked latifundia. In agriculture, slaves usually appear as tenants rather than as forced laborers. Most agricultural work, as well as maintenance of the irrigation system, required diligence, foresight, and care. It was more practical to give slaves contracts to work independently so that they would have an interest in the result. Again in contrast to Roman experience, there was little problem of slaves rebelling and using their agricultural tools as weapons. However, some of the inventories made by business partners, or by families for inheritance divisions, report that slaves had run off.

Slaves could live and work independently of their master by paying him a mandattu fee. They basically were hiring or renting themselves from their master. As they had to earn much more than an average hireling, this was an option only for clever and well-trained slaves. In addition to paying their own mandattu, some privileged Egibi slaves also paid that of their wife so that she could accompany them. Other slaves entered partnerships as junior partners. Such business arrangements will be discussed in more detail below.

As in Greek practice, some Neo-Babylonian slaves acted as proxy for their masters and managed their affairs, but unlike the case in Greece, Neo-Babylonian slaves apparently did not engage in large-scale moneylending. Perhaps this is because in Babylonia there was no moral stigma attached to the practice, which might have prevented their masters from doing it themselves.

Itti-Marduk-balā u of the Egibi family entrusted at least three of his slaves with running his on-the-spot affairs during prolonged periods of his absence. Their letters address the master as “my lord,” while he addresses his slave as “my brother.” One such slave is known to have started a business of his own with five minas of silver and two junior partners.35 By contrast, Itti-Marduk-balā

u of the Egibi family entrusted at least three of his slaves with running his on-the-spot affairs during prolonged periods of his absence. Their letters address the master as “my lord,” while he addresses his slave as “my brother.” One such slave is known to have started a business of his own with five minas of silver and two junior partners.35 By contrast, Itti-Marduk-balā u seems not to have trusted his own brothers in business matters.

u seems not to have trusted his own brothers in business matters.

In contrast to Roman practice, no evidence exists for Babylonian slaves buying their liberty with money they earned through their enterprise, no matter how rich they became. Manumission was a voluntary act that only could be initiated by the master. In Babylonia manumission normally was connected with the obligation to care for the aging master and mistress until their death. Manumission therefore occurred most often near the end of the slave's working life.

Neo-Babylonian Economic and Legal Institutions: Property and Contract Law

Over a century ago J. B. Say remarked: “English economists almost always confuse under the name of profit, the return that the entrepreneur obtains from his industry and his talent, and that which he derives from his capital.”36 The contrast between entrepreneurs and more passive financial backers is spelled out in remarkable clarity in Neo-Babylonian harrānu37 contracts that organized trade and business partnerships on a debt/equity basis.

These partnerships commonly were formed between a senior financial backer (the sleeping partner) and an on-the-spot junior partner who did the actual work.38 Drafted as an interest-free debt contract, they implied that the backer would recoup his original capital upon the dissolution of the business, so that only the profits were shared and either reinvested or distributed in regular intervals. Such partnerships were neither new nor unique, as similar forms of enterprise already are known from the beginning of the second millennium BC under the name of tappûtum, especially in long-distance trade. A stipulation in the laws of Hammurabi (ca. 1750 BC) reads:39

If a man gives silver to another man for investment in a partnership venture, before the god they shall equally divide the profit or loss.

The way in which such partnerships are set up corresponds to the principles of the Islamic mu āraba,40 Italian commenda, and the Hanseatic trade partnerships, of which they may be considered ancient ancestors. What is new in Neo-Babylonian times is the scope and the field of activity: many people are doing it, applying its business principle to intraregional trade.

āraba,40 Italian commenda, and the Hanseatic trade partnerships, of which they may be considered ancient ancestors. What is new in Neo-Babylonian times is the scope and the field of activity: many people are doing it, applying its business principle to intraregional trade.

Success would allow junior partners to gradually pay off their backer and reap the fruits of their efforts in full. One such contract, Nbk 216 from the thirtieth year of Nebuchadnezzar (575 BC), illustrates this process:

“Six minas (= 3 kgs.) of silver, (the working capital owed) to person A (is) at the debit of person B, for a harrānu (business venture). (Of) whatever he makes (with it) in city and country, one half of the surplus person B shares (lit. “eats”) with person A. The(se six minas of) silver are the remaining (unpaid balance of the original) harrānu debt note of eleven minas from the twenty-fourth year of Nebuchadnezzar (that was) at the debit of person B.”

Names of three witnesses and the scribe, place and date.41

In this arrangement person A was the senior financing partner and person B the junior working partner. The latter would have to share equally with the senior partner whatever profit he made through his own efforts and use of the senior partner's capital. He returned nearly half the original venture capital (in this case amounting to eleven minas of silver) to the venture capitalist over the course of six years.

Such partnerships typically divided the profit equally, as in the above example. But this legal instrument was flexible, and could be adapted to different circumstances depending on the number of partners, their function, and the ratio between capital and work-input.42

Such arrangements enabled well-to-do individuals to play the role of venture capitalists by finding capable partners to manage their harrānu businesses. There must have been many individuals eager to establish business but without enough capital to set themselves up on their own—for instance, younger sons who did not inherit much. Some Neo-Babylonian archives show such men entering a business as junior partners, working with money put up by a backer, and making enough to rise to the position of senior partner, financing other newcomers to work for them.

One such example is Kā ir from the Nūr-Sîn family. He started out as a junior partner in 581 BC with eleven minas (ca. 5.5 kg) of silver, and in six years was able to repay his backer nearly half of the original capital out of his earnings.43 He then was joined by his younger brother Iddin-Marduk from 576 to 572 BC. They already (if possibly only partially) were working with their own funds, and employed an acting partner, although at least on one occasion not successfully.44 The brothers' business profited from Iddin-Marduk's marriage, as he put seven minas (3.5 kg) of his wife's dowry silver into their risky affairs.45 Creditors must have had substantial claims against the two of them and their father, for Iddin-Marduk's father-in-law in 571 BC urged him to transfer all his property to his wife as security for her dowry silver that he had invested in his family's business. He dutifully signed over two slave women and their five children—evidently all his property not tied up in the business.46

ir from the Nūr-Sîn family. He started out as a junior partner in 581 BC with eleven minas (ca. 5.5 kg) of silver, and in six years was able to repay his backer nearly half of the original capital out of his earnings.43 He then was joined by his younger brother Iddin-Marduk from 576 to 572 BC. They already (if possibly only partially) were working with their own funds, and employed an acting partner, although at least on one occasion not successfully.44 The brothers' business profited from Iddin-Marduk's marriage, as he put seven minas (3.5 kg) of his wife's dowry silver into their risky affairs.45 Creditors must have had substantial claims against the two of them and their father, for Iddin-Marduk's father-in-law in 571 BC urged him to transfer all his property to his wife as security for her dowry silver that he had invested in his family's business. He dutifully signed over two slave women and their five children—evidently all his property not tied up in the business.46

Occasionally two or more partners would pool funds, acting as partners on equal terms in order to achieve a critical mass for business. Dar 97 from the Egibi archive (518 BC) is an example of this kind of arrangement:

“Five minas of A and five minas of B they have put together for a harrānu (business venture). (In) whatever they make from these ten minas, they (have) equal (shares).” Names of at least four witnesses and the scribe, place and date.47

We find this type of arrangement also in the affairs of the aforementioned Iddin-Marduk. Ultimately separating himself from his brother's business, he entered into a harrānu venture with another person, first as junior partner but soon shifting to a parity arrangement that lasted seven years. Simultaneously, he employed junior partners of his own. In this manner he still did part of the field work himself, while spreading his risks and testing the capabilities of his underlings. His career was typical of entrepreneurs of the time, and is exceptional only because of his remarkable success.

The returns to harrānu enterprise typically were high. They had to be, given the customary annual interest rate of 20 percent. This was the “opportunity cost” of capital—what backers could get simply by lending out their money against security. Because the return had to be shared, a harrānu venture would make sense for the financial backer only if it promised to return at least 40 percent annually, twice the 20 percent interest rate on secured loans.

The junior partner's objective was to return the venture capital out of his earnings so that he might come to own the business outright. Even after establishing a business with his own equity, however, he might borrow money from the former senior partner or other individuals at interest to bridge a short period or even to expand his operations.

Harrānu ventures might last beyond an entrepreneur's own lifetime when sons inherited and carried on the business. Whereas the relatively short-term Greek and Roman commercial partnerships normally divided up the proceeds upon the completion of each voyage or other venture, the Egibi archive includes one partnership that lasted over forty-two years from one generation to the next. The heirs did not dissolve and divide up the business until such time as the managing partner grew too old to continue running it any longer.48 Even so, for at least three more years both parties jointly shared the income from a field purchased with business proceeds.

Entrepreneurial Efficiency: A Case Study

How the Egibi family rose from junior partners to large financial entrepreneurs. The Egibi family represents an outstanding example of Schumpeter's idea that the main entrepreneurial opportunities for profit or quasi-rent lie in creating new business practices. The key to their far-flung operations was the ability to turn commodities into money by creating a marketing plan that integrated agricultural production, tax payments, and the shipment of crops to the cities along Babylon's canal system.

It took many years for the founders of the family fortune to accumulate enough money to become backers of their own operations. The archive does not document who provided the money for their earliest ventures. Evidently they were able to find (or be found by) backers, starting out as junior managing partners in profit-sharing harrānu ventures. Over a span of two generations the family built up its relationships with some royal officials responsible for collecting taxes and fees linked to land ownership. By the third generation the family is documented maintaining close relations with the governor of Babylon, who was in charge of collecting taxes, organizing corvée labor and the military draft.

Account-keeping and enterprise. Once established, the Egibi family typically conducted its business in partnership arrangements with others, usually on-the-spot entrepreneurs whom they found and backed, just as their own family's business founders were once backed. These partnerships involved a specific activity, such as brewing date-beer or buying local crops and selling them in Babylon. The Egibi prepared regular accounts for these ventures to calculate the surplus.

These businesses usually maintained their working capital at a steady level, distributing profits to the individual partners to do with as they chose. Rather than using them to expand the joint venture, partners typically took their profits out of the business to invest in their own. Their detailed accounts show how much each party put into specific enterprises, and the records assign property and its income to the partners of each venture. The level of detail is comparable to those of Europe's Hanse towns some two thousand years later.

Economic innovation. At the beginning of Nabonidus' reign (555 BC), or maybe even earlier, the Egibis are known the have developed a special relationship to the chief administrator of the crown prince's household. After they had acquired a house adjacent to the crown prince's palace, the Egibis leveraged this real estate investment by borrowing against the house. They arranged a loan-rental mortgage transaction, by borrowing the funds from the man who rented the house, with the rent corresponding to the customary interest charge of 20 percent—the modern definition of equilibrium between asset price, rent, and carrying charges. In other words, the Egibis borrowed to buy a prestigious house, and then turned around and rented it out to their creditor.49

Antichretic credit arrangements (where use of the pledge is granted to the creditor in lieu of interest payments) were not new in themselves, but normally they were used in a different context. When an individual in need of cash had pledged his house or field as security to a creditor, but at a certain point could not catch up with the interest payment, he would relinquish to his creditor the right to use the pledged asset, in lieu of the interest payment. This typically was the final, and sometimes long-lasting, stage before transfer of ownership. The Egibis, in contrast, were not debtors in distress. They rather used this legal instrument to acquire title to the house but kept its value liquid for other business ventures, a clear sign of their creative approach to a given legal framework. The brilliance of this arrangement was that it involved the administrator of the crown prince's palace as creditor-tenant, who thus could make use of the premises. For the Egibis, this transaction essentially was an interest-free loan, and did not require any real flow of funds until the debt eventually was repaid. This loan/rent contract was occasionally renewed and remained in place under four different rulers and through the dynastic change, from the reign of Nabonidus to Darius. This was important in view of the standard 20 percent per annum rate of interest on secured loans, which did not allow profitable real estate speculation—a major factor keeping real estate prices fairly stable, except as they reflected economic growth and prosperity.

Moneylending and the question of banking. Late nineteenth-century literature, written shortly after the Egibi archive was discovered, described them as bankers of Jewish descent. Their family name was thought to derive from Hebrew Jacob. This fit contemporary perceptions (or rather misconceptions) about Jews and their role in banking. Even today some publications apply these labels without explanation, though the ideas both of “bankers” and the allegedly Jewish ethnicity of the Egibis were shown to be inappropriate many decades ago. The family name Egibi is of straightforward Sumero-Babylonian origin,50 and the business of the branch that left the famous archive fits the description of entrepreneurs rather than being associated with deposit banking.51

Investment of business profits. Successful business operations yielded high profits, but it made sense to add this gain to the working capital only under conditions where a healthy expansion could be achieved. Partners typically chose to retire some capital by distributing it among themselves, to buy land, houses, slaves, and luxury goods whenever opportunities were available. This generated further income and helped build up their prestige while serving as a store of value that could be collateralized for a loan when necessary. One set of Egibi records regards the sale of assets worth fifty minas of silver to settle debts that were probably accumulated backlogs.

When the Egibi inheritance was divided among the fourth-generation sons in 508 BC, the family owned sixteen houses in Babylon and Borsippa and more than one hundred slaves, not to mention agricultural land not inventoried on this occasion.

Economy-Wide Efficiency of Enterprise

Rent and tax farming are much like the privatization of modern public utilities: they may or may not be efficient. The motive for institutions to privatize is understandable. They need reliability, stability, and accountability, which they may be unable to get internally for one reason or another. Entrepreneurs, of course, get into the arrangement for the money. In such cases the question is always whether the private entrepreneur can serve the public better and more efficiently than a public institution or its officials. Will the profit motive invite efficiency, or become corrosive as investors extract as much profit as possible in as short a time as possible, leaving the business in ruins? However we may answer such questions, it seems that Neo-Babylonian society found the outsourcing of various royal and temple functions to be an important and productive economic practice. But constraints were put on them.

Incentives and Disincentives for Innovation

Two obstacles to enterprise can be identified: the effort needed for political lobbying and the inheritance system.

Political lobbying. Businessmen engaged in rent or tax farming depend upon certain political institutions and officials. Such undertakings demand care of political relationships. Rent or tax farmers may have had to spend a great deal of time establishing and maintaining such contacts, and expended resources on prestige goods to give as presents, incentives, or bribes. This is inherently risky business because the entrepreneur never can be fully sure that powerful benefactors will not turn against him. Itti-Marduk-balā u traveled to Persia for extended periods to secure his tax-farming business. These trips were apparently strenuous and dangerous, as he made his will before he left the first time. They were critical to his success, as they were to other Babylonian families.

u traveled to Persia for extended periods to secure his tax-farming business. These trips were apparently strenuous and dangerous, as he made his will before he left the first time. They were critical to his success, as they were to other Babylonian families.

Inheritance divisions. Inheritance rules often are blamed as business disrupters by causing productive assets to be divided between many heirs, each receiving a share too small to be profitable. This happens under traditional Islamic law and has been cited as one of the reasons why capitalist development did not occur in Islamic societies in the same way as in the West.52 In Neo-Babylonian practice, sons were the only heirs, who excluded collateral relatives, and women could not inherit through intestate succession. Furthermore, at least half of the legacy remained in one hand, as the law provided that the eldest son receive twice as much as his brother, or half of the estate if there were more than two sons.53 This middle-of-the-road approach assured that none of the brothers went penniless, while keeping the core business intact.

Moreover, Neo-Babylonian society had the institution of “undivided brothers” comparable to the Hindu joint family,54 allowing the business to be kept running as a single entity for a considerable period of time after the father's death. Without any need for legal formalities, the eldest son succeeded to his father's business and represented the heirs collectively. This delayed the inheritance division—an essential condition for a smooth transition. As long as brothers did not divide their father's inheritance, all business proceeds belonged to all of them according to their shares in the inheritance, regardless of who did the actual work.

Such arrangements were not always without conflict. Evidence again is glimpsed from the Egibi records. When Itti-Marduk-balā u's eldest son finally sorted out the family business with his two brothers, some fourteen years after his father's demise, he tried to claim certain objects on the ground that they had been bought with money of his wife in her own name. The brothers refused to accept his claim, as the dowry's usufruct lay with the husband's father, and subsequently with his heirs as long as they maintained their undivided status. In the end everything had to be included in the division.55 In sum, Neo-Babylonian inheritance rules had some dysfunctional business consequences as compared to primogeniture, but did not cause the same level of disruption found in many other systems that practice partible inheritance or include a wider circle of heirs.

u's eldest son finally sorted out the family business with his two brothers, some fourteen years after his father's demise, he tried to claim certain objects on the ground that they had been bought with money of his wife in her own name. The brothers refused to accept his claim, as the dowry's usufruct lay with the husband's father, and subsequently with his heirs as long as they maintained their undivided status. In the end everything had to be included in the division.55 In sum, Neo-Babylonian inheritance rules had some dysfunctional business consequences as compared to primogeniture, but did not cause the same level of disruption found in many other systems that practice partible inheritance or include a wider circle of heirs.

Lessons for Contemporary Innovative Entrepreneurship

The Neo-Babylonian political and economic environment provided ample room for innovation toward higher levels of productivity in an agriculturally based economy. It permitted and required entrepreneurs to function as intermediaries between the basic level of agricultural production and consumers on the one hand, and between the individual landholder and all levels of royal or temple administration on the other. As intermediaries they helped extend and intensify agricultural production and processing of raw materials. By extending credit and monetizing commodity payment-in-kind into money-taxes they helped monetize and integrate different sectors of production.

The moral is that new technologies and equipment are not the only important ways to increase productivity. Critical aspects of entrepreneurial success include the way relationships are established, the way labor and profit is shared, the methods of financing, and the manner of product marketing and distribution.

Notes

1 Nabopolassar (21 years, 626–605), his son Nebuchadnezzar II (43 years, 605–562), the latter's son Evil-merodach (2 years, 562–560; murdered), Nebuchadnezzar's son-in-law Neriglissar (4 years, 560–556), followed by the latter's son Laborosoarchod, who only reigned for two or three months until Nabonidus usurped power. His son Belshazzar was left in charge of Babylonia when Nabonidus spent several years in the Arabian desert, but was never recognized as king; hence all contemporary Babylonian records date to the reign of Nabonidus (17 years, 556–539).

2 The best-known example is the biblical account on the Judaeans in Babylonian captivity. Tablets excavated in the southern palace of Babylon document the issuing of commodities to high-profile captives or hostages (Weidner 1939). Among the recipients are dignitaries from Judah, most prominently King Jehoiachin (cf. 2 Kings 24.8–12; 25.27–30; 2 Chr. 36.9–10; for an easy-to-find summary of the Babylonian sources see www.livius.org/ne-nn/nebuchadnezzar/anet308.html). Recent tablet discoveries allow a glimpse of the lives of ordinary Judaean people, deported and settled in rural Babylonia. For an overview see Pearce 2006; a full edition is being prepared by her and the present author.

3 On this transition see most recently Jursa 2007 with previous literature.

4 Cyrus (9 years, 539–530), his son Cambyses (8 years, 530–522), and Darius (from a side branch of the Achaemenids, 36 years, 522–486). The short-lived reigns of Smerdis (alias Bardiya, also called Gaumata) and the usurpers Nebuchadnezzar III and IV date to 522 and 521.

5 Herodotus, Histories I (Kleio), 192.

6 This has been suggested by van Driel 2002, 164–65, 318–19, and discussed by Jursa (2004), who argues that an increase in productivity and export volume offset the negative effects of Persian taxation. Babylonia must have exported textiles and food to obtain the silver paid to Persia. Productivity increase can be demonstrated for institutional agriculture, although probably it was not enough to offset the increasing tax burden in the long run.

7 For the dates of the Babylonian revolts against Persian rule and their political consequences, as well as a thorough study and interpretation of the phenomenon of the end of these archives, see Waerzeggers 2003–4, with discussion of previous literature.

8 According to Jursa 2005, 1.

9 Jursa (2005, 57–152) provides an overview in English of Neo-Babylonian archival documents according to provenance and excavation history, as well as a brief summary of their contents.

10 For an overview see Wunsch 2007 (in English); more detailed in Wunsch 2000a, esp. 1–19 (in German).

11 Francesco di Marco Datini (1335–1410); most of them business letters (Origo 1997, 8).

12 Jursa 2007 provides the most recent and reliable overview in English on the economic situation of Mesopotamia during the first millennium BC.

13 Known as bīt redûti “house of succession” or bīt mār šarri “house of the king's son” in sources from Neo-Babylonian as well as Achaemenid times, this institution seems to have survived the political and dynastic change virtually unchanged.

14 Akkadian rab kā ir, Persian ganzabara. Estates of this official are known from the vicinity of Babylon, and the Egibi family was involved in managing them.

ir, Persian ganzabara. Estates of this official are known from the vicinity of Babylon, and the Egibi family was involved in managing them.

15 The term oblate, derived from Latin offerre “to offer,” essentially means the same as Akkadian širkū, i.e., a person given or presented to a religious institution, although the concepts behind the terms differ a bit. Babylonian temple dependents (also referred to as “temple slaves”) were bound to live and work in their temple or on its land (much as the serfs of Indian temples), but in contrast to Christian oblates they were encouraged to live in families to reproduce and allowed to own personal property. Nevertheless, living conditions must have been harsh for most of them, as temple records constantly report on escaped personnel.

16 These were better conditions than granted to temple oblates. The temple administration had to deal with the fact that their dependents tried to rent out portions of their (usually too large) assignments in outlaying areas where administrative control was less effective; see Janković 2005.

17 On details of rent farming in the temple context see Cocquerillat 1968 (concerning date orchards of Eanna in Uruk [in French] and Jursa 1995 (on arable land and date orchards of Ebabbar in Sippar [in German]).

18 See Hudson, chap. 1 in this volume.

19 Van Driel 1999 discusses this dossier of texts.

20 The tablet dates to the eighth year of Darius (514 BC). See MacGinnis 2007, text no. 1.

21 This does not mean banking. Banking in its narrow definition refers to taking in deposits, giving out credit, and living off the interest differential. That did not happen until the third century, as Jursa 2007 has shown.

22 See Kozuh, forthcoming, for details.

23 Fishing is best documented in the Eanna archive of Uruk; see Kleber 2004 (in German).

24 This was spelled out by Jursa 2004, based on ideas of Vilfredo Pareto and Max Weber.

25 The example of the Šangû-Gula family is treated by Wunsch 2000a, 139–50.

26 The evidence has been studied by Caroline Waerzeggers and presented at a conference in 2004; the results will be included in a forthcoming study. This summary is based on her communication.

27 Wunsch 2004, 370–71.

28 See Jursa 2005b, 108–9, sub 7.9.1.1. for an overview of the archive of Itti-Šamaš-balā u and the Šamaš-bāri file with a brief discussion on their connection. Itti-Šamaš-balātu's activities are covered in greater detail by Beaulieu 2000.

u and the Šamaš-bāri file with a brief discussion on their connection. Itti-Šamaš-balātu's activities are covered in greater detail by Beaulieu 2000.

29 Roth 1991.

30 References are discussed by Jursa 2002, 203–5.

31 This land probably was claimed early in Nebuchadnezzar's reign, in 2,000-meter-wide strips on both sides of the canal, subdivided into units of 1/50 and 1/1000. The Egibis bought it in 559 BC from the heirs of a former governor of Babylon.

32 See Cocquerillat 1968 (for Eanna at Uruk) and Jursa 1995 and 1998 (for Ebabbar at Sippar).

33 This is known from the Egibi and Bēl-e ēri-Šamaš archives.

ēri-Šamaš archives.

34 Compare Goody 1980. In some societies slavery existed for considerations of prestige: “By supporting slaves who might be less productive than hired workers the masters are, in effect, displaying their wealth for all to see.…The exhibition of idleness may be the slave's only real duty but this has to be extracted like any other service” (Watson 1980, 8).

35 Nbn 466 (Strassmaier 1889b; 545 BC): Nergal-rē ūa. He still nominally belonged to Ina-Esagil-ramât (the wife of Iddin-Marduk and mother-in-law of Itti-Marduk-balā

ūa. He still nominally belonged to Ina-Esagil-ramât (the wife of Iddin-Marduk and mother-in-law of Itti-Marduk-balā u), and probably was the son of one of her dowry slaves.

u), and probably was the son of one of her dowry slaves.

36 Say 1803, book 2, chap. 5; 1972, 352. English translation after Charles Gide, “Jean Baptiste Say,” Palgrave's Dictionary of Political Economy (London, 1926).

37 Originally meaning “path, road,” the term broadened to include all sorts of road travel, such as “military campaign, expedition, business trip, caravan.” Its use as a legal term designates a special kind of partnership venture and the capital provided for it.

38 Lanz (1976) studied the legal aspects of these partnerships. For additional details see Jursa 2005a, 212–22 (both in German). A comprehensive study of the economic aspects of such partnerships (including the source material published after 1976) is much desired.

39 The translation follows Roth 1995 (p. 99, gap ¶ cc; in other editions counted as  98).

98).

40 See the contribution by Timur Kuran, chap. 3 in this volume.

41 Nbk 216 (Strassmaier 1889a) from 21/ix/30 Nebuchadnezzar = 25.10.575 BC, edited in Wunsch 1993 as no. 5. The conversion of Babylonian dates into the Julian calendar is based on Parker and Dubberstein 1956.

42 As pointed out by Jursa (2004), who discusses the many possibilities.

43 Nbk 216; see translation above at note 38.

44 BRM 1 49 (Clay 1912), edited in Wunsch 1993 as no. 7.

45 Nbk 254 (Strassmaier 1889a) (572 BC, edited in Wunsch 1993 as no. 9) reads: “The account balance concerning the silver that PN1 (the father-in law) has put as dowry at the disposal of PN2 and that is at the debit of PN2 and PN3 (the brothers) they have not yet finished.”

46 Nbk 265 (Strassmaier 1889a), edited in Wunsch 1993 as no. 13.

47 Dar 97 (Strassmaier 1897) from 14/xii/3 Darius = 12.3.518 BC.

48 First partnership contract: Nbk 300 (Strassmaier 1889a; 569 BC). The dissolution in the third year of Cambyses is mentioned in BM 31959 (edited in Wunsch 2000a as no. 10; for more detail see 1:99–104).

49 For details see Wunsch 2000a, 103–4.

50 Egibi is an abbreviation of Sumerian E.GI-BA-TI.LA, the full form being used occasionally in the archival records. In a learned text on the meaning of their most ancient family names Babylonian scribes equate it to the Babylonian name Sîn-taqīsa-liblu , which can be translated as “O Sin [the moon god], you have granted (us this child), may he now live and thrive,” which follows a well-attested Semitic name pattern. The Assyriologist F. E. Peiser already in 1897 pointed out that it had nothing to do with Jacob, and occurs in cuneiform records in the eighth century BC, long before the time of the Babylonian captivity.

, which can be translated as “O Sin [the moon god], you have granted (us this child), may he now live and thrive,” which follows a well-attested Semitic name pattern. The Assyriologist F. E. Peiser already in 1897 pointed out that it had nothing to do with Jacob, and occurs in cuneiform records in the eighth century BC, long before the time of the Babylonian captivity.

51 R. Bogaert's exhaustive 1966 study on early “banking” shows that the essential characteristic of taking money as a deposit and lending it out at a higher rate cannot be found.

52 See Timur Kuran's contribution to this volume for details.

53 These rules are derived from practical texts such as records of inheritance divisions, property transfers, wills, etc., as law collections covering this topic comparable to the Codex Hammurabi from the early second millennium are not preserved from this period. The preferential double share for the eldest son also features in pre-Neo-Babylonian times. The fact that the eldest of more than three sons takes one-half of the inheritance (i.e., more than a double share) has been a recent discovery; see Wunsch 2004, 130–31, 144–45. A comprehensive study of inheritance law in first-millennium Mesopotamia is being prepared by the present author.

54 Joint families consist of several generations, with all the male members being blood relatives. The family is headed by the pater familias, usually the oldest male, who makes decisions on economic and social matters on behalf of the entire family. All property is held jointly with virtual shares assigned according to each member's inheritance rights. As long as the undivided status remains, all income achieved by any of the members accrues to all of them proportionately.

55 The record on the inheritance division is Dar 379 (Strassmaier 1897) from 508 BC. It contains the following stipulation (ll. 55–56 and 59–60): “(Concerning) all their fields, as many as there are, including the fields that…(the eldest son) has bought in in his (own) name, (in the name of)…, his wife, or in the name of someone else:…(the eldest son) will take a half share, and…(the younger brothers) will take a half share (of the aforementioned assets).”

References

Abraham, Kathleen. 2004. Business and Politics under the Persian Empire. The Financial Dealings of Marduk-nā ir-apli of the House of Egibi. Bethesda, MD: CDL Press.

ir-apli of the House of Egibi. Bethesda, MD: CDL Press.

Baker, Heather D., and Michael Jursa, eds. 2005. Approaching the Neo-Babylonian Economy: Proceedings of the START Project Symposium Held in Vienna, 1–3 July 2004. Alter Orient und Altes Testament 330. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag.

Beaulieu, Paul-Alain. 2000. “A Finger in Every Pie: The Institutional Connections of a Family of Entrepreneurs in Neo-Babylonian Larsa.” In Interdependency of Institutions and Private Entrepreneurs: Proceedings of the Second MOS Symposium (Leiden 1998), ed. A.C.V.M. Bongenaar, 43–72. Istanbul: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul; Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten.

Bongenaar, A.C.V.M., ed. 2000. Interdependency of Institutions and Private Entrepreneurs: Proceedings of the Second MOS Symposium (Leiden 1998). Istanbul: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul; Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten.

Cocquerillat, Denise. 1968. Palmeraies et cultures de l'Eanna d'Uruk (559–520). Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft in Uruk-Warka 8. Berlin: Mann.

Clay, Albert T., ed. 1912. BRM 1. Babylonian Records in the Library of J. Pierpont Morgan. Part 1. New York, privately printed.

van Driel, Govert. 1999. “Agricultural Entrepreneurs in Mesopotamia.” In Landwirtschaft im Alten Orient (CRRAI 41, 1994), ed. Horst Klengel and Johannes Renger, 213–23. Berliner Beiträge zum Vorderen Orient 18. Berlin: Reimer.

——. 2002. Elusive Silver: In Search of a Role for a Market in an Agrarian Environment. Aspects of Mesopotamia's Society. Istanbul: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten.

Goody, Jack. 1980. “Slavery in Time and Space.” In Asian and African Systems of Slavery, ed. James L. Watson, 16–42. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Janković, Bojana. 2005. “Between a Rock and a Hard Place: An Aspect of the Manpower Problem in the Agricultural Sector of Eanna.” In Approaching the Neo-Babylonian Economy: Proceedings of the START Project Symposium Held in Vienna, 1–3 July 2004, ed. Heather D. Baker and Michael Jursa, 167–81. Alter Orient und Altes Testament 330. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag.

Joannès, Francis. 2000. “Relations entre intérêts privés et biens des sanctuaires à l'époque néo-babylonienne.” In Interdependency of Institutions and Private Entrepreneurs: Proceedings of the Second MOS Symposium (Leiden 1998), ed. A.C.V.M. Bongenaar, 25–41. Istanbul: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul; Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten.

Jones, David. 2006. The Bankers of Puteoli: Finance, Trade, and Industry in the Roman World. London: Tempus.

Jursa, Michael. 1995. Die Landwirtschaft in Sippar in neubabylonischer Zeit. Archiv für Orientforschung, Beiheft 25. Vienna: Institut für Orientalistik.

——. 1998. Der Tempelzehnt in Babylonien vom siebenten bis zum dritten Jahrhundert v. Chr. Alter Orient und Altes Testament 254. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag.

——. 2004. “Grundzüge der Wirtschaftsformen Babyloniens im ersten Jahrtausend v. Chr.” In Commerce and Monetary Systems in the Ancient World: Means of Transmission and Cultural Interaction. Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Symposium of the Assyrian and Babylonian Intellectual Heritage Project Held in Innsbruck, Austria, October 3rd–8th, 2002, ed. Robert Rollinger and Christopf Ulf, 115–36. Melammu 5. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

——. 2005a. “Das Archiv von Bēl-e ēri-Šamaš.” In Approaching the Neo-Babylonian Economy: Proceedings of the START Project Symposium Held in Vienna, 1–3 July 2004, ed. Heather D. Baker and Michael Jursa, 197–268. Alter Orient und Altes Testament 330. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag.

ēri-Šamaš.” In Approaching the Neo-Babylonian Economy: Proceedings of the START Project Symposium Held in Vienna, 1–3 July 2004, ed. Heather D. Baker and Michael Jursa, 197–268. Alter Orient und Altes Testament 330. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag.

——. 2005b. Neo-Babylonian Legal and Administrative Archives: Typology, Contents, and Archives. Guides to the Mesopotamian Textual Record 1. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag.

——. 2007a. “The Transition of Babylonia from the Neo-Babylonian Empire to Achaemenid Rule.” In Regime Change in the Ancient Near East and Egypt: From Sargon of Agade to Saddam Hussein, ed. Harriet Crawford, 73–94. Proceedings of the British Academy 136. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

——. 2007b. “The Babylonian Economy in the First Millennium BC.” In The Babylonian World, ed. Gwendolyn Leick, 220–31. London: Routledge.

Kleber, Kristin. 2004. “Die Fischerei in der spätbabylonischen Zeit.” Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes 94:133–65.

Kozuh, Michael. Forthcoming. The Sacrificial Economy: On the Management of Sacrificial Sheep and Goats at the Neo-Babylonian/Achaemenid Temple of Uruk.

Lanz, Hugo. 1976. Die neubabylonischen  arrânu-Geschäftsunternehmen. Münchener Universitätsschriften, Juristische Fakultät. Abhandlungen zur rechtswissenschaftlichen Grundlagenforschung 18. Berlin: J. Schweitzer.