Your style is an emanation from your own being.

—KATHERINE ANNE PORTER

The whodunit is not limited to the world of crime; it’s also a staple of literary scholarship. A book lands with a thud on an editor’s doorstep one morning, with no clues to its origins. It’s anonymous, pseudonymous, unattributable—yet unignorable.

Who wrote it? Interested critics might have their favorite suspects. Opportunistic writers may even quarrel over credit. But the answer, as with any mystery, lies in the cold, hard facts. Which is to say, aspiring literary detectives will need to turn to the numbers.

Let’s return to The Federalist Papers controversy from the introduction, one of the most famous literary mysteries solved in the past century. In order to urge ratification of the Constitution in the late 1780s, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay each wrote essays that appeared in New York newspapers under the pseudonym “Publius.” Between them, the three men wrote a total of 85 essays, but no one took credit for any individual essays until decades later. When Madison and Hamilton outlined who wrote each essay, there was a contradiction. Twelve of the essays were claimed by both Madison and Hamilton.

In 1963 two statistics professors, David Wallace and Frederick Mosteller, put forward evidence in Inference in an Authorship Problem that would end the near two-century-long debate. Their probabilistic case was objective and detailed. It quantified writing styles. It succeeded where qualitative arguments had suffered.

Their biggest step forward was treating words like random variables. Instead of viewing the words as sacred they looked at them the same way they would study the rolls of a die or a flip of a coin. The two looked at the frequency of hundreds of words, which was not easy to do in 1963. They took copies of each essay and dissected them, cutting the words apart and arranging them (by hand) in alphabetical order. At one point Mosteller and Wallace wrote, “during this operation a deep breath created a storm of confetti and a permanent enemy.”

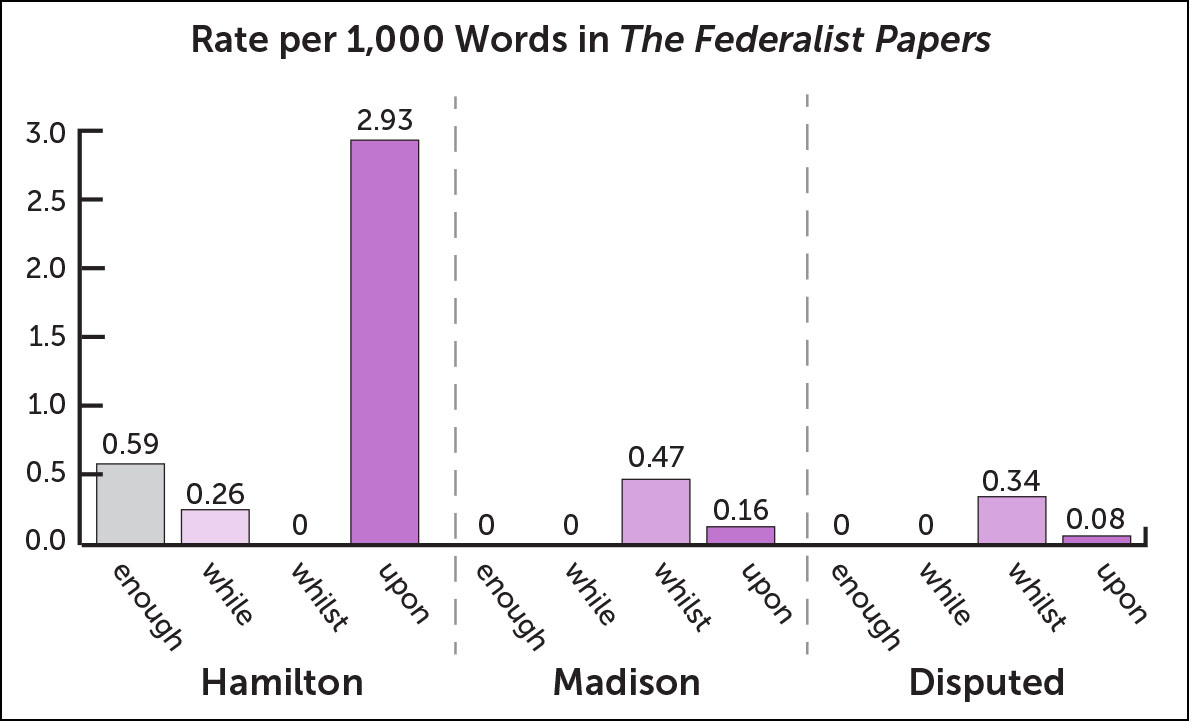

In particular, they started looking at a handful of words that were used by one author but not the other. In his known papers Alexander Hamilton used the word while but never the word whilst. Madison used the word whilst but not while. The professors listed the rate of enough, while, whilst, and upon per 1,000 words in the Hamilton, Madison, and disputed papers.

The graph of Mosteller and Wallace’s figures on the previous page lends itself to an easy conclusion. Hamilton used enough and while but Madison and the disputed papers never did. Hamilton used upon to a high degree, but Madison and the disputed papers used it at a much lower rate. Whilst is absent from Hamilton’s writing but present in the disputed papers. It looks like it can’t be Hamilton, right?

But this was not enough for Mosteller and Wallace. It was just four words. If that’s all you saw you might think there is no reason for more data or more analysis. However, if Mosteller and Wallace had looked at according, whatever, when, and during they would have found the opposite:

The graph above makes the disputed papers line up with Hamilton’s patterns. I had to search through hundreds of words to find numbers this contradictory, but the point remains that not every word’s frequencies are constant in every text. Most words don’t line up perfectly for either Madison or Hamilton—the eight you see here are rare. And if you look through enough words, you’ll be able to find a handful that can support any conclusion: Hamilton, Madison, even you or me.

That’s why Mosteller and Wallace created a system to weigh the importance of a large number of factors. The exact details rely on some equations that we don’t need to get into here. But the thought process is straightforward. Each word allowed them to make a small calculation about who the likely author was. When the differences in word frequencies were all combined, the outliers cancelled out. All of those small probability calculations, when multiplied together, amassed to a rock-solid prediction: A text with this level of the usage, that level of during usage, that level of whatever usage, etc., would never in a thousand years have been written by Hamilton. It would have taken an outright miracle, a sudden change to every marker of his writing style, for Hamilton to pen those 12 essays. On the other hand, they sat neatly within the realm of Madison’s own style.

It’s worth noting that Mosteller and Wallace make a huge assumption by treating words like dice. The two assume that writers use roughly the same word frequencies throughout their works, and this assumption is critical to their equations’ success. If writers change their style to match different subjects, characters, and plots, then Mosteller and Wallace’s method would fail frequently. At the very least, the variation that a writer uses between their works needs to be insignificant compared to the variation between other authors for the method to work. That assumption ultimately held up for Hamilton and Madison: The method’s ability to arrive at a prediction confirms that there was an underlying consistency to the two Founding Fathers’ writing styles.

But I’ve long wanted to see just how far the theory can go—to test whether something like a literary fingerprint exists for famous writers.

The rest of this chapter will look in depth at Mosteller and Wallace’s assumption that word choice is constant. If it is correct, and style does not change from book to book, then their method should work just shades off 100 % of the time, regardless of genre. Forensic scientists are able to use fingerprints to identify people because the ridges on people’s fingers do not change. But are the stylistic fingerprints that each author leaves in their writing unique enough, and permanent enough, for Mosteller and Wallace to pick them up without fail?

The uniqueness of fingerprints has been known for thousands of years. No two fingerprints are the same, and civilizations as early as ancient Babylon and China used them to ensure contracts.

Fingerprints don’t tell you anything about the suspect by themselves. The identification process only works if you have a set of the suspect’s fingerprints on file or a database to compare against an unknown print. What if the same could be done for books? Mosteller and Wallace’s method suggests that writers have a hidden fingerprint, too: Authors leave a pattern of words wherever they write. And in the last two chapters we’ve assembled quite a few samples.

To start experimenting with this idea, I gathered a mixed collection of great and popular books, almost 600 books by 50 different authors. This would serve as my full database. (The full list is included in the Notes section on page 264.) Then I chose one book, Animal Farm by George Orwell, and removed it from the sample.

Mosteller and Wallace didn’t build their method specifically for novels. And though people will sometimes attempt to identify one particular book, no one has ever gone through and replicated the professors’ original methods on a large set of novels by known authors. To find out if it could work, I started with a small test.

First I set Animal Farm as the unknown fingerprint. I then treated Hemingway’s ten novels and Orwell’s five other books as my known sample. With two possible options, Mosteller and Wallace pinpointed Orwell as the author of Animal Farm. It was a good start, but a coin would have a 50-50 chance of being accurate after one test.

Then, I expanded the list of candidates. One by one I set my computer to test Animal Farm against each of the other 48 authors in the sample. This includes authors considered among the greats, such as Faulkner and Wharton. It features many writers who have found huge popularity, such as Stephen King and J. K. Rowling. And it includes a handful of other writers who have achieved recent literary success, such as Jonathan Franzen and Zadie Smith. For each author I included their complete bibliography of novels. In each of the 48 test cases the result was the same: Mosteller and Wallace were able to correctly identify Orwell as the author of Animal Farm.

I wanted to see if this was a fluke. Perhaps Animal Farm was an outlier with a weird style that had unusual results. I compared each of Orwell’s other five books (Burmese Days, A Clergyman’s Daughter, Keep the Aspidistra Flying, Coming Up for Air, and 1984) to the other 49 writers in the sample. Each time, I removed the book in question from Orwell’s sample and treated it as an unknown text. Out of 245 comparisons using Mosteller’s system, it was right 245 times. In every case it listed Orwell as the more probable author.

I then expanded further, testing every single book in the sample, pitting each one head-to-head against its actual author and each of the 49 other authors. This totaled 28,861 tests. I figured it would be the best way to confirm if Mosteller and Wallace has validity on long fiction.

Every time, the method was looking at the same basic 250 words. Of the almost 29,000 tests Mosteller’s system worked all but 176 times. This is over a 99.4 % success rate.

How is it possible that a system so simple works so well?

The reason it works is that authors do end up writing in a way that is both unique and consistent, just like an actual fingerprint is distinct and unchanging.

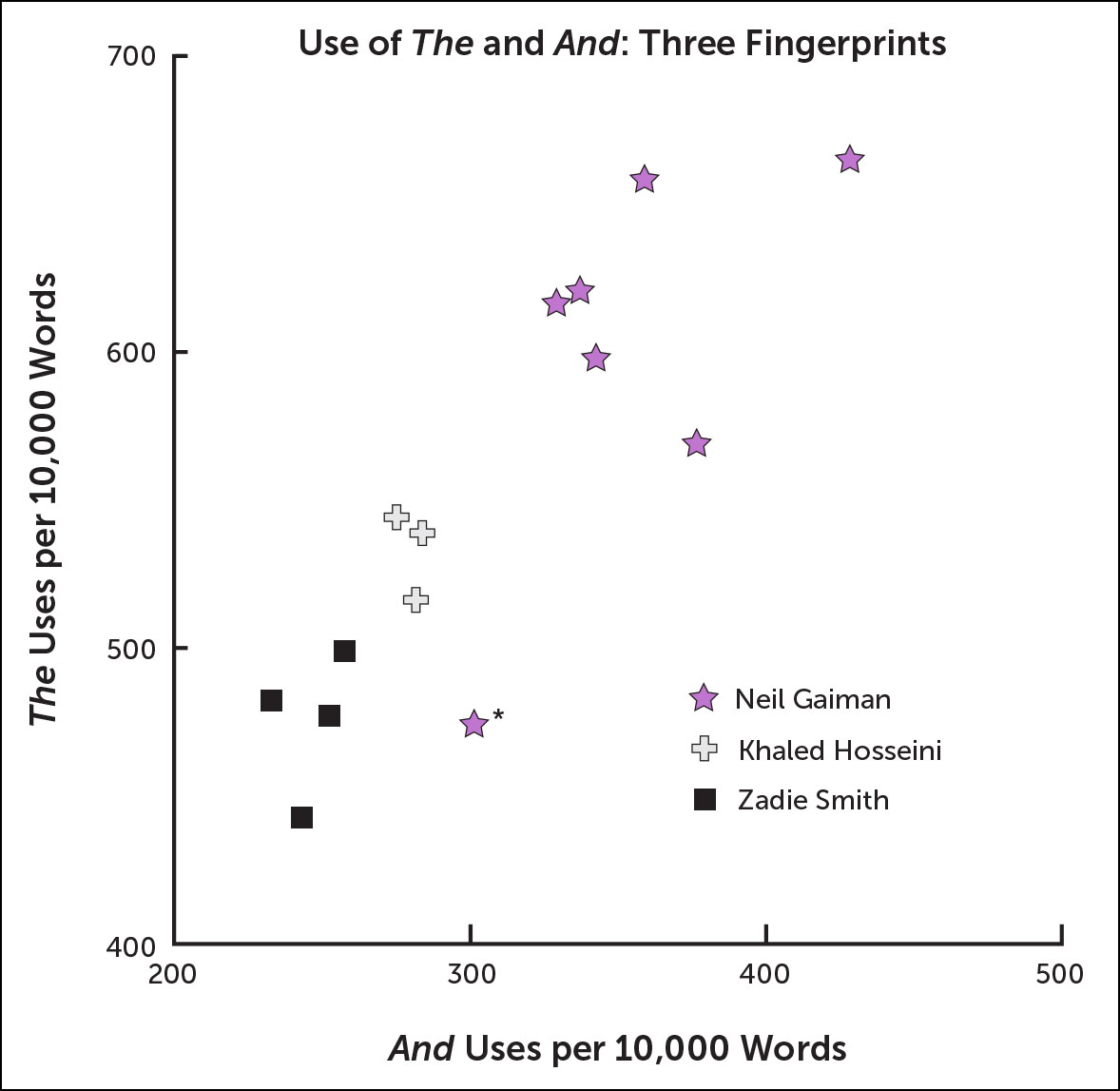

Consider Khaled Hosseini, Zadie Smith, and Neil Gaiman. They do not write about the same subjects or with the same tone, but they are all modern-day popular authors with overlapping international audiences. Mosteller and Wallace can distinguish their work with 100 % accuracy (28 out of 28) by looking only at 250 simple words. In fact, even just looking at the and and, the two most common words in the sample, you can see distinctions among the three writers. Take a look at the graph below.

The “fingerprint” of the and and is illuminating. If one datapoint’s label were removed from this chart, we’d have little trouble predicting the author based on where it falls. With the simple eyeball test you could guess right the majority of the time using only the two most common words.

There are exceptions of course. The most obvious is Anansi Boys. It is the one book (asterisked below) by Gaiman with fewer than 500 thes per 10,000 words. This looks like it could be categorized as Hosseini or Smith before Gaiman.

But Mosteller and Wallace has something going for it. The and and are just a fraction of the words used to distinguish texts. On the sample of 50 writers, using Mosteller and Wallace to predict authorship with just the word the is correct in 71 % of head-to-head comparisons. With the and and it’s right 83 % and with the top ten most common words it gets by at 96 %.

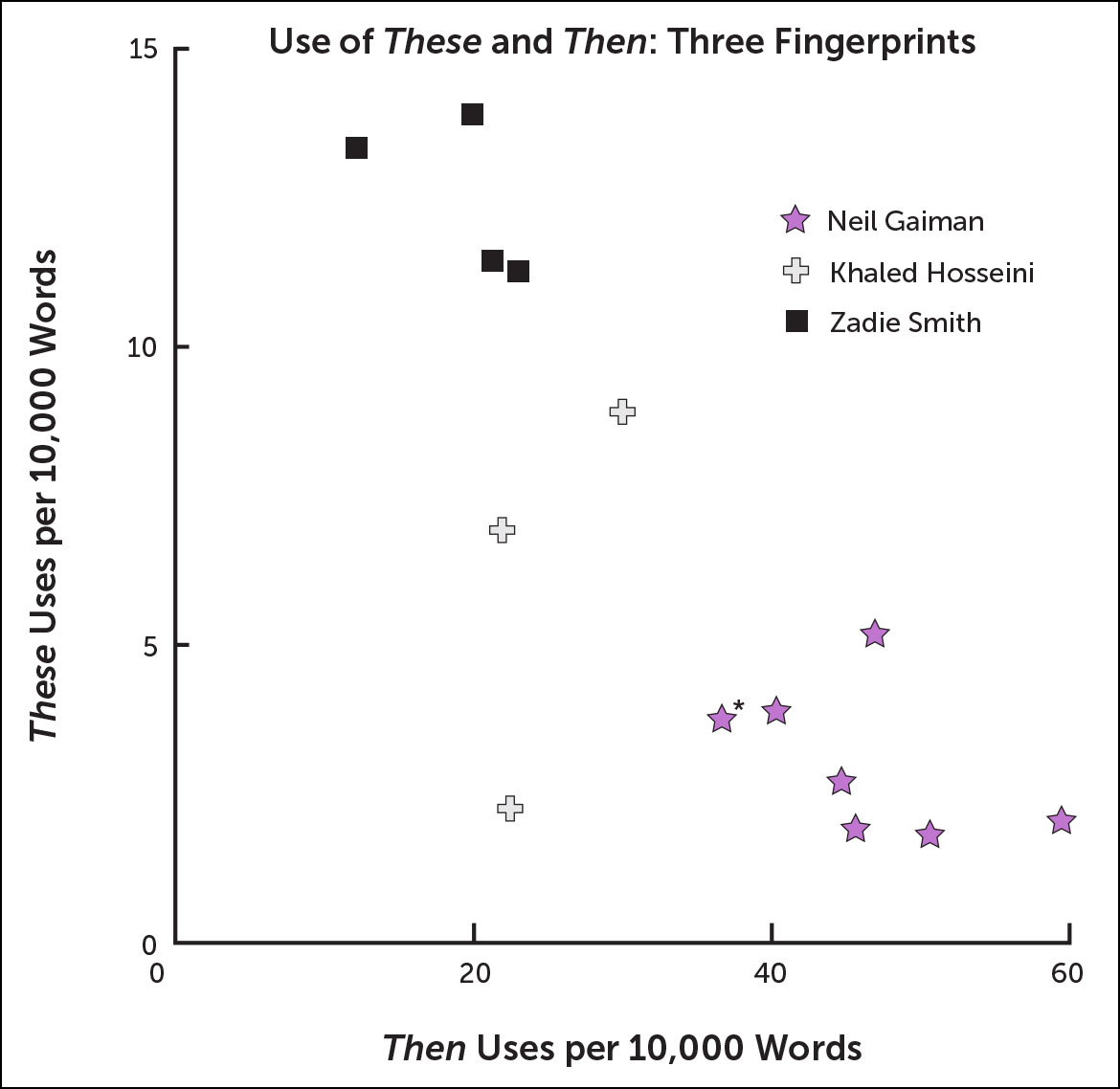

Though writers may have a book with indistinguishable or out-of-character patterns for a single word, by the time the couple hundred most common words are accounted for, the style is undeniable. Consider these and then, which when graphed reveal a distinct Gaiman cluster. Anansi Boys, which was out of character on the the and and plot, is asterisked again. This time, it’s right in the middle of Gaiman’s other works.

The method is not entirely perfect. Of every comparison, William Gaddis’s The Recognitions was the most misidentified novel, with 39 out of 49 authors coming up as the more likely author than Gaddis. Three out of nineteen Steinbeck novels listed Mark Twain as the more probable author. But with a failure rate of just one for every 165 head-to-head tests, Mosteller and Wallace’s system works wonders.

The previous section showed that Mosteller and Wallace worked 99.4 % of the time on known works, but what happens when a writer is actively trying to disguise themselves? The central assumption of the model is that writing style is constant, but can an author stay incognito by trying to write for a different fan base or in a different genre?

Consider the cases of Richard Bachman and Robert Galbraith.

Richard Bachman is a horror writer. For years he ran a dairy farm in New Hampshire and wrote at night. His life was tragic. Bachman’s only son drowned in a well and the author himself died of cancer in 1985. Fortunately for his readers, he left behind a large volume of works that are still being published to this day.

Richard Bachman is also alive and well. He is a pen name of Stephen King.

The true identity of Bachman was unmasked when a reader noticed similarities between the style of Bachman’s writing and another of his favorite suspense writers. He did a search of the Library of Congress catalog and found the book listed under, just as he’d suspected, Stephen King. The master of mystery novels had failed to cover his tracks.

But could Mosteller’s formula have detected Bachman’s true identity from the text of his novels alone?

The simple answer is no. It can be used to detect if the true author is writer A or writer B when A and B are both known. In the case of Bachman the alternative was that Bachman was real, or at the least a separate unpublished author. There would have been no way to tell with any certainty that King was the author.

However, what if that industrious reader in 1985 had decided to take the investigation into his own hands and replicate Mosteller on Bachman with a sample of bestselling authors? Who was more probable to be Bachman? Agatha Christie or James Patterson? Elmore Leonard or Tom Wolfe? Or Stephen King?

These tests could show distinct similarities or differences, even if they couldn’t catch the true author red-handed. If King and Bachman turned out to have little in common by the numbers, then Mosteller and Wallace could at least dissuade you of your pet theory.

For all four of Bachman’s books, when compared to our fifty top authors, Stephen King comes up as number one every time. That’s 196 correct identifications out of 196. Of course, many of these pairings seem trivial. Charles Dickens would not be confused for a horror novelist by anyone. But the success is still lopsided enough that it could have added firm confidence to the reader who noticed the qualitative similarities.

Following are the ten authors who were top five most probable and least probable.

Most Probable to be Richard Bachman

1. Stephen King

2. James Patterson

3. Tom Wolfe

4. Gillian Flynn

5. Neil Gaiman

Least Probable to be Richard Bachman

1. Suzanne Collins

2. J. R. R. Tolkien

3. Veronica Roth

5. Jane Austen

Not all pseudonym speculations turn out to be true. In 1976 American radio host John Calvin Batchelor forwarded one of the more far-out literary conspiracy theories I’ve heard. In SoHo Weekly he wrote:

What I am arguing . . . is that J. D. Salinger, famous though he was, simply could not go on with either the Glass family, which had by 1959 his weight to bear, or with his own nationally renowned reputation . . . So then, out of paranoia or out of pique, J. D. Salinger dropped ‘by J. D. Salinger’ and picked up ‘by Thomas Pynchon.’

Since then Batchelor has backed down from his theory. He received a letter from Thomas Pynchon after the article was written saying he was mistaken. The rumor has persisted, even if in jest, as a function of how reclusive both Pynchon and Salinger are or were.

We’ve seen Mosteller’s math work well on The Federalist Papers and Stephen King. What does it say about Pynchon and Salinger?

Again, we would not be able to definitively confirm the theory that Salinger and Pynchon are the same person, but the empirical evidence here can rule out that Salinger and Pynchon are the same person.

I compared Salinger’s work (excluding short stories, so just The Catcher in the Rye and Franny and Zooey) against 49 other authors. Combined with Pynchon’s eight books, this amounted to 392 different tests. In 42 of these tests it identified Salinger as the more probable author. For instance, J. D. Salinger was more probable to be the writer of Pynchon’s Inherent Vice than Ernest Hemingway. But in 350 out of 392 cases, Salinger turned out less likely to be the author.

Quantitatively, then, Salinger’s writing bears no similarity to Pynchon’s novels on the word-for-word level. The test confirmed what we already know: Pynchon is not Salinger, and radio hosts who put forward attention-seeking theories are more often wrong than right.

There is one more pseudonym challenge that I’ve wanted to test—one where the author is switching genres. And the perfect example arose when Robert Galbraith arrived on the scene. Like Richard Bachman, Galbraith doesn’t actually exist. He’s J. K. Rowling’s pen name. But whereas King wasn’t trying to change his writing much as Bachman, Rowling was trying to change her style in the Galbraith books. The Galbraith books are detective novels written for Muggle adults, while the entirety of our Rowling sample consists of the Harry Potter books, full of magic and geared toward young adults. This is a major shift. What if Mosteller had been born fifty years later and decided to investigate Robert Galbraith and J. K. Rowling instead of obsessing over The Federalist Papers? Would the change in genre mean a departure in style?

Remarkably, even with the leap out of the Harry Potter universe, Mosteller and Wallace could pick out J. K. Rowling as the best match for all three Galbraith books.

Most Probable to be Richard Bachman

1. J. K. Rowling

2. Jonathan Franzen

3. Stephen King

4. James Patterson

5. Jennifer Egan

Rowling wrote one detective novel, The Casual Vacancy, under her own name, but that wasn’t included in my earlier sample. Her Harry Potter books alone were the best match for all three of her Cormoran Strike novels. It was accurate in 147 out of 147 head-to-head tests.

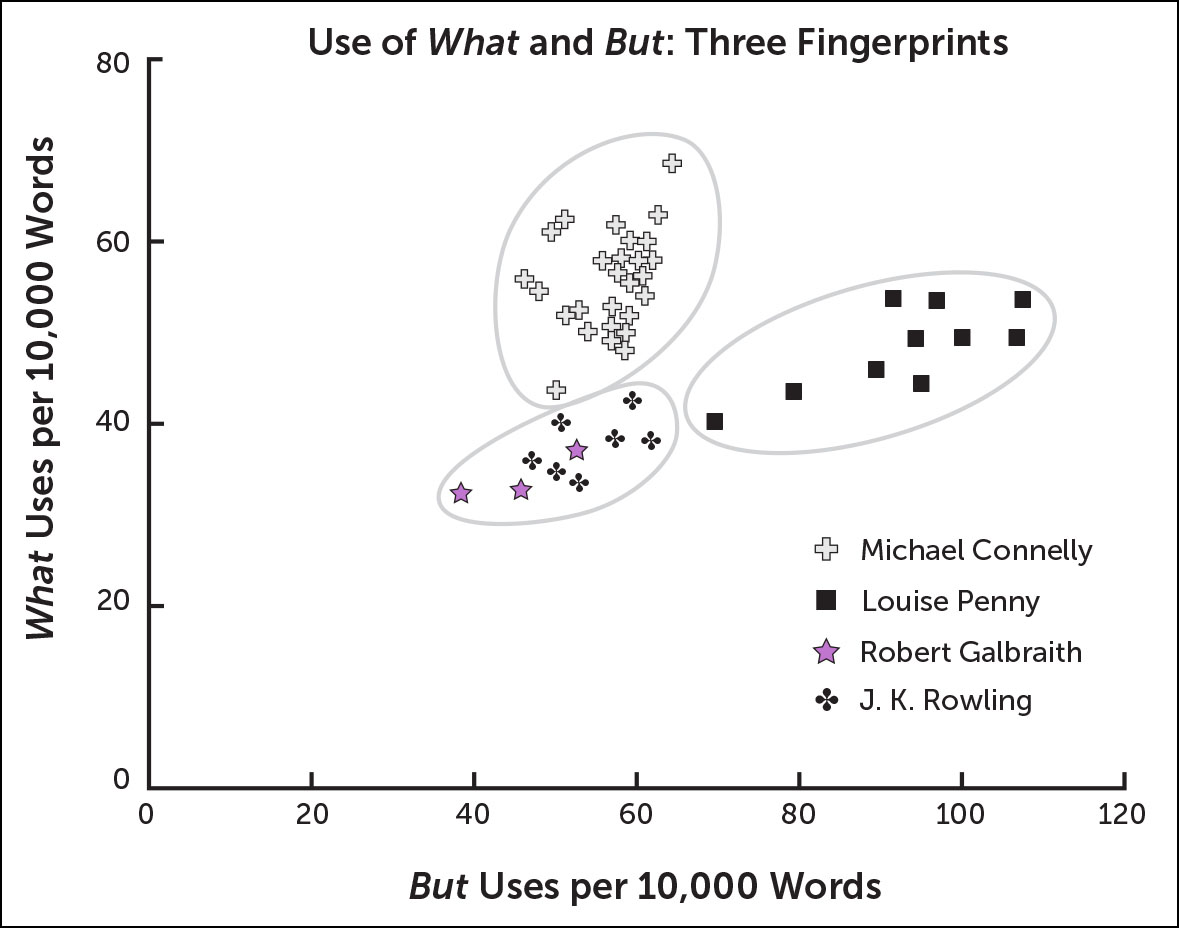

Here’s Harry Potter compared to Cormoran Strike as well as the two other most popular detective series (according to a Goodreads.com vote), Inspector Gamache by Louise Penny, and Harry Bosch by Michael Connelly. The two words being compared are but and what.

Perhaps there are slight differences among word frequencies from Potter to Cormoran, but when Rowling shifts in writing detective fiction her prose doesn’t change at its core. The word frequencies depend more on the writer than the genre. Her writing style stayed closer to the Harry Potter universe than the worlds of Louise Penny or Michael Connelly, and when hundreds of words are taken into consideration (instead of just two) it becomes exceedingly hard for her work to be mistaken for that of many other writers.

Rowling’s transformation to detective writer is just one test case, but it’s a powerful one. Writers can change genre, and attempt to hide their identity, but that doesn’t mean they can hide their writing.

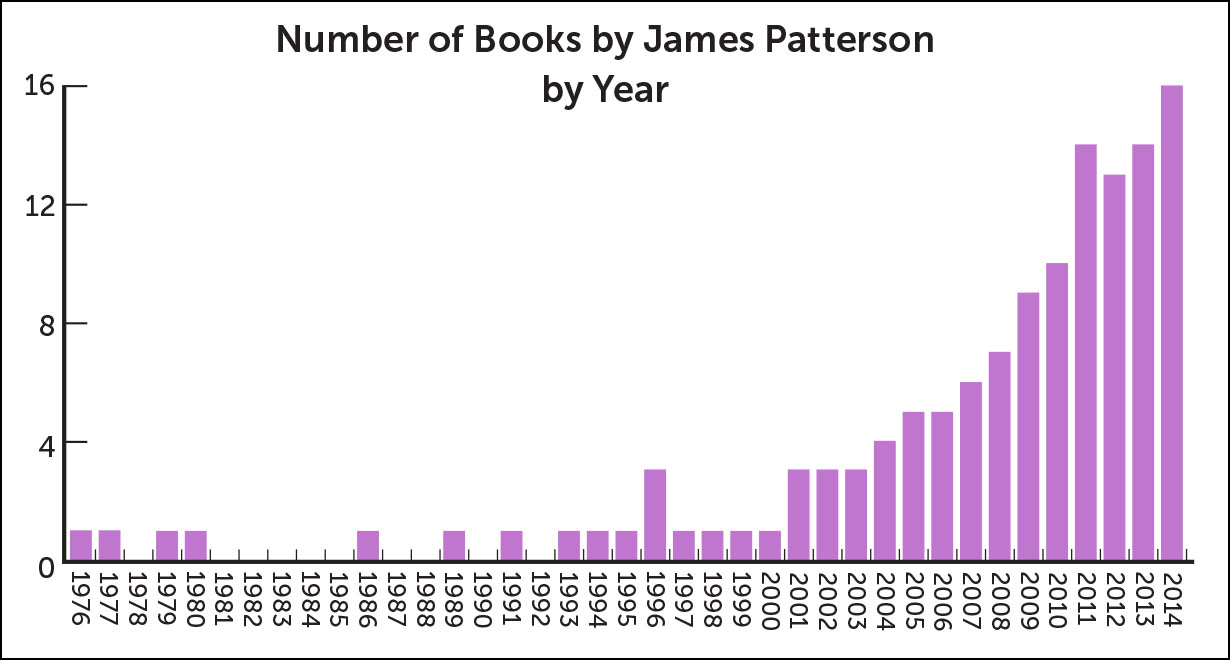

James Patterson is a prolific writer and his readers are prolific in their consumption of his work. A New York Times article on the writer stated that between 2006 and 2010 Patterson was the author of one out of every 17 hardcover novels bought in the United States.

Even since then, Patterson has ramped up production. He started as a thriller writer, publishing around a book a year and now runs multiple series. In 2014 he published 16 books. Patterson has also started to branch off from his thriller roots into fiction geared toward young middle schoolers with his series titled Middle School.

Patterson is quoted as saying, “I believe we should spend less time worrying about the quantity of books children read and more time introducing them to quality books that will turn them on to the joy of reading and turn them into lifelong readers.” But it’s not as if he has anything against quantity. In all of the 1990s he published a total of ten books, fewer books than he puts out per year these days.

Here is a graph showing the number of books by James Patterson published each year between 1976 and 2014.

Despite what the pattern of the graph suggests, James Patterson is not on pace to keep writing books at an increasing rate ad infinitum. For one thing, he’d run out of co-authors first.

How does Patterson manage to publish so many books a year? He is not shy about his process. In a Vanity Fair profile of Patterson by Todd Purdum, the author said that the way he works with collaborators is to detail an outline. Then the co-authors are responsible for turning the outline into a draft. Here’s an excerpt from Purdum’s piece of one of Patterson’s outline descriptions: “Nora and Gordon continue their quick banter, funny and loving. We like them. They’re good together—and not just when they’re standing up. A minute later the two engage in some terrific, earth-moving sex. It makes us feel great, horny, and envious.” That’s a lot of weight left on the co-author’s shoulders.

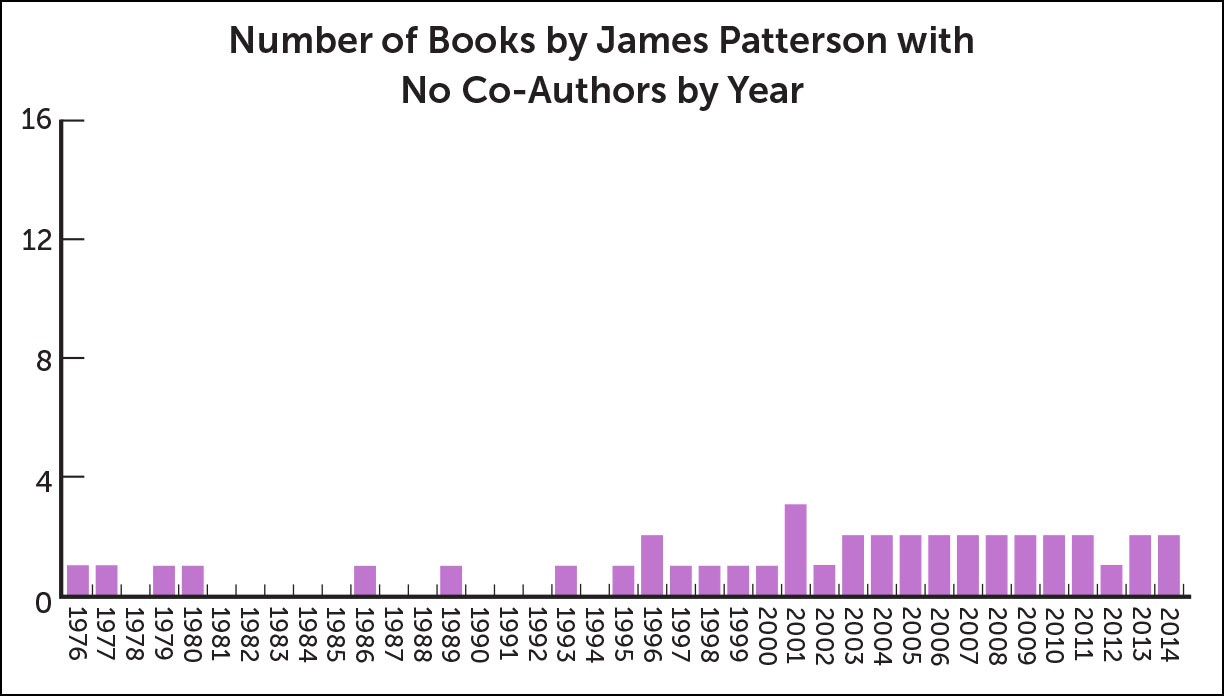

For comparison, below is the number of books by James Patterson without a listed co-author.

Patterson has four writers with whom he’s published at least five novels: Andrew Gross, Howard Roughan, Maxine Paetro, and Michael Ledwidge. These four have worked with Patterson (but not with each other) on a combined 37 novels.

Most of Patterson’s co-authors have not published enough independent works to judge against the books they co-authored. However, we can compare these partnerships against one another. If we run the Mosteller test on all of these 37 novels the test is 111 for 111. It recognizes all the books co-written with Andrew Gross, for instance, and can distinguish them from those co-written with Maxine Paetro.

And on the other side of the coin it has a low error rate distinguishing between a Patterson solo project and a Patterson co-write. The word frequency equations were correct 94 % of the time (117 times out of 125). It misidentified, for instance, that Confessions of a Murder Suspect was a solo project when it was actually co-written with Maxine Paetro. It also misidentified a few books (like Cross My Heart) as more similar to the co-written books with Michael Ledwidge even though they are solo books. But on the whole Mosteller and Wallace can tell.

The results on the previous page suggest that as much consistency as Patterson and his editors may strive for there are still major distinguishing differences between the different co-authors. If you are a fan of some Patterson books more than others, it may be time to pay attention to the second name on the cover as well.

Even when writing within a single series, Patterson’s co-authors have a noticeable impact on the writing style. Because of the huge number of combinations in Patterson’s works, we can answer the following question: Are James Patterson’s works more consistent across series or across co-authors?

The Women’s Murder Club book series started with 1st to Die and has continued through 2014, when Unlucky 13 was published. Andrew Gross co-wrote two of the books in this series while Maxine Paetro co-wrote ten. Both these authors have written other books with Patterson not in the series.

Does Mosteller say Gross’s book 2nd Chance is more similar to other books in the same series co-written with Paetro or more similar to other books co-written with Gross, even if they’re in a different series?

The math places 2nd Chance closer to Gross’s other works than to Paetro’s books in The Women’s Murder Club series. If we look at the ten books co-written by Paetro the same is true. Mosteller picks out the co-author even across series.

Without a point of comparison, it’s impossible to tell if a Patterson-Gross book is more similar in style to Patterson or Gross. None of the many Patterson co-authors have a sizable library of their own. So although the numbers show there is a clear difference between each co-writer and the co-written books from the solo projects, it’s possible that each co-author was just adding a dash of flavor that made them unique.

The burning question that many readers have, however, is whether their favorite writer is using a co-writer or essentially employing a ghostwriter. This line between ghostwriter and co-writer is not always clear or agreed upon. Some people may argue that just because one writer does the outlining and the other writer does the actual writing, that doesn’t mean it was ghostwritten. No matter your viewpoint on the distinction, the books—Patterson’s and other big-name authors’—are marketed in a way that obscures the roles. Consider the cover here of a book listed as “Tom Clancy with Mark Greaney.”

The average reader seeing this mass-market cover in a grocery store would assume that Clancy was the lead writer of the story in every way. Clancy is a huge name, known for his hits like The Hunt for Red October and Patriot Games. In his career he wrote 13 novels as the sole author. He also co-wrote a number of novels as well as getting involved in “creating” novels. The series Tom Clancy’s Op-Center bears Tom Clancy’s name, and he is credited as the “creator.” But he wrote none of them; Jeff Rovin did.I For every one book that Tom Clancy authored himself he “created” five others.

When Clancy did co-write, the author he shared a byline with the most was Mark Greaney. They wrote three books together. Greaney has also published five books independent of Clancy. All his collaborations with Clancy are listed as “Tom Clancy with Mark Greaney,” even if you have to squint to find Greaney’s name on the cover.

If we run Mosteller and Wallace on each author’s solo novels, the results are what we would expect. It correctly identifies Clancy’s books 13 times out of 13 and Greaney’s five out of five. The authors’ styles are distinct.

The three books that Clancy and Greaney co-authored were Command Authority, Threat Vector, and Locked On, all novels in the Jack Ryan series. When we run the numbers on these books, however, all three come out Greaney over Clancy. If the disputed documents in Mosteller and Wallace’s paper had been the three co-written books instead of the 12 Federalist essays, they would pick Greaney every time. Look, for instance, at what we see when we compare but and what.

The nondisclosure agreements that co-authors sign to work with mega-authors restrict them from revealing how the writing was split up. Without the breakdown of the method, it’s hard to get too detailed in the analysis. But to get a more granular look, I split all of the Clancy, Greaney, and “Clancy with Greaney” books into 5,000-word chunks. I then used Mosteller and Wallace methods on each small section. The attribution of the divided books is shown on page 78.

For these short 5,000-word snippets, Mosteller and Wallace is nowhere near the 99 % perfection that it achieves on entire novels. We know that because sections in The Hunt for Red October are attributed to Greaney despite the fact that he was 16 years old when Clancy published it. Maybe the sections that show up as more Clancyesque in the collaborative books were written by Clancy. Or maybe Clancy wrote around 2,000 of every 5,000-word section, and there are just a few samples that happened by luck to resemble his writing more. In either case, the patterns in the “Clancy with Greaney” books suggest that the co-authorships relied more on Greaney’s writing than Clancy’s.

In an interview Greaney said that when collaborating with Clancy he “never tried to copy [Clancy’s] style,” and Mosteller and Wallace bear this out. Greaney’s writing style came through much more in the final drafts than Clancy’s own. If you loved the plot twists and structure, then you could likely thank both Clancy and Greaney. But, if you happened to think it was filled with great descriptions and fast-paced sentences, you may be best advised to pick up another Greaney book next.

To test the breaking point of Mosteller and Wallace I thought long and hard over what the worst literary nightmare for the mathematical model might be. Was there any type of writing that could trip up the equations? After deliberating I came up with the perfect challenge (which perhaps should have been obvious all along): Twilight fan fiction.

In the sections above I looked into the question of genre and writing style, but fan fiction has an element of specificity. The works are not just the same genre or sub-genre, but the same sub-sub-sub-genre. The actual characters stay the same between different authors. All the texts are written within a short window of time. And even more so, the writers are all heavily influenced by the same canonical author.

If Mosteller and Wallace could identify different authors, even when genre has been neutralized, then it seems like it’s a good bet to take on any long-form fiction. This, I imagined, was the method’s final showdown.

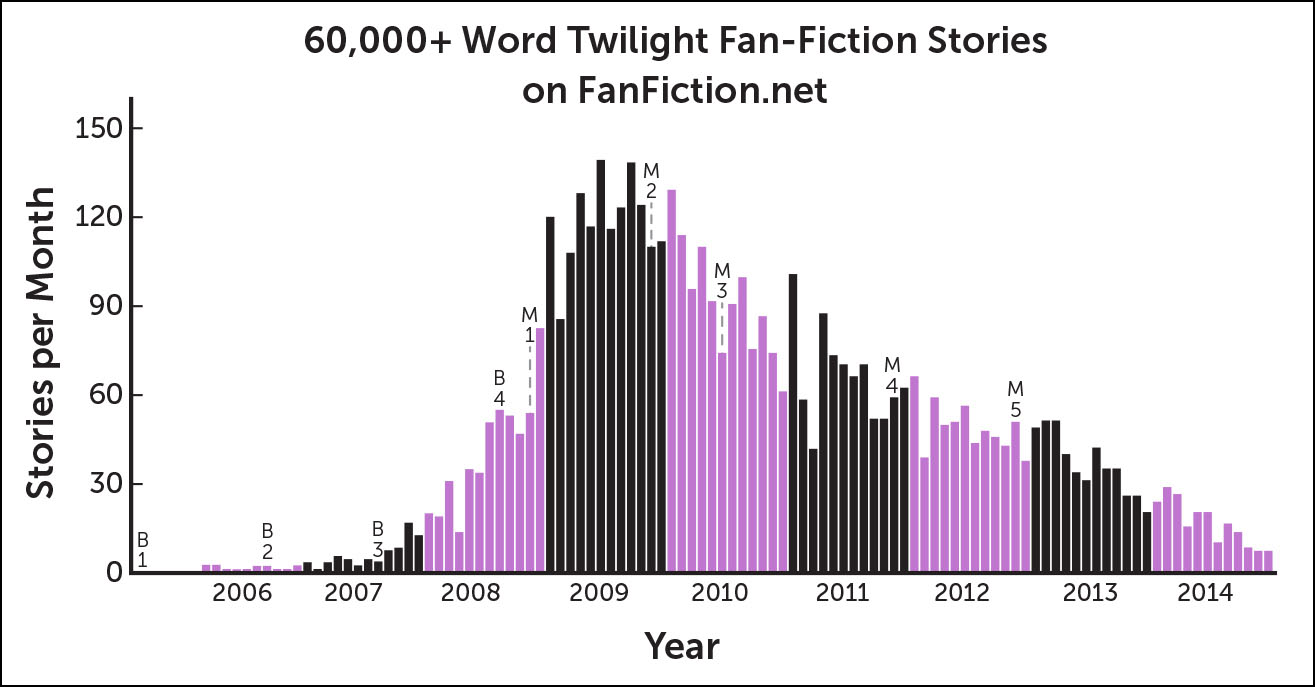

On the website FanFiction.net, the most popular of many fan-fiction websites, people have written more than 1 billion words of Twilight fiction. I chose Twilight for its enormous sample size. Below is a plot of all stories with 60,000-plus words (long enough to be a full novel) dating from Twilight’s first release until the end of 2014. In total, there have been 5,000 novel-length Twilight stories posted on FanFiction.net, which I would be comparing to the four novels in the original series. You can see the mounting popularity of fan fiction as the books (marked B1 to B4) came out, and the huge leap immediately after the first movie (marked M1) was released.

Stephenie Meyer wrote 600,000 words in the Twilight series, and 153 writers on FanFiction.net have bested her word count in their own Twilight fan fiction.

I ran the Mosteller and Wallace test on Meyer’s Twilight books and the top fifty most prolific authors. All these authors, except for Meyer, have written more than 1 million words.

Harkening back to my initial test on Animal Farm, I removed one Twilight book at a time and compared that to (A) the other three books in the series and (B) the complete bibliography of each of the fifty fan-fiction writers. No author passed for Meyer. That’s a record of 200 for 200.

If you compare all fan-fiction writers, like airedalegirl1, against one another, the results are nearly as strong. Out of all 24,445 combinations of comparing one fan-fiction work to the other fan-fiction authors (or Meyer), the math was right 24,365 times.

The 99.7 % success rate is near identical to what we found when looking at writers who varied greatly in genre, era, and subject. If you think that genre is a major tipoff, then Twilight fan fiction would be a major obstacle. Still, Mosteller and Wallace recognize the differences between each author.

I reached out to the top-writing Twilight fan-fiction author of all time, airedalegirl1. I wanted to know how her writing process works (and how long she spends on it). Airedalegirl1, whose real name is Jules, has written 38 stories of 60,000-plus words, totaling 3.7 million words. She is a married woman in her fifties who lives in England. She writes “each day for two to three hours.” When I told her she’d written more than anyone else, Jules said, “I’ve never really thought about how much I’ve written. I don’t plan my stories, they evolve . . . it’s just organic.”

In addition to sample size, I think airedalegirl1’s attitude explains part of the success of Mosteller and Wallace on the fan-fiction corpus. Because these are writers who have written an incredible amount of fan fiction in an incredibly small span of time, they are more or less putting words on the page as they think of them. Once they finish one story they start the next. Almost all of these amateur fan-fiction authors have written more words in a few years than professional literary novelists do in a lifetime. The chance that a fan-fiction author decides to shift style and write an experimental novel with a new voice is slim.

The Twilight example and the J. K. Rowling/Galbraith example demonstrate two sides of the question of how genre affects writing style. Rowling changed genres, yet her writing style was still distinct. Fan-fiction authors write the same exact genre, yet their voices remain quite distinct from one another.

Mosteller and Wallace would likely not be surprised by the success of their model on Twilight because their first test of the case was also on the study of two writers with similar backgrounds, writing in the same series. They postulated that because writers use a consistent voice, it was possible to tell them apart.

All I did here was replicate the simple equations to test their theory on novelists. Ninety-nine times out of 100 the two statisticians were right: Within the prose of every writer, whether obvious to the reader or not, there is an underlying fingerprint setting them apart from all other authors who anyone has ever read.

I. Since Clancy’s death in 2013 the series was relaunched after a nine-year break. The new books are written by new authors, Dick Couch and George Galdorisi.