Pretending to care about our health is often just part of the drug and other medical industries’ overall strategy to increase their sales. They dominate the medical journals, airwaves, newspapers, and magazines with “information” designed to convince doctors and patients that their products are essential for good health. They focus attention on the health problems and solutions that are the most commercially advantageous rather than most beneficial for our health. They even pathologize normal human experiences such as menopause and aging, reframing the transitions of a healthy life into medical problems that require diagnoses and drugs—and in the process alienating us from the meaning inherent in the landmarks of a healthy life.

The truth, as we have seen, is that the benefits of medical care are real but limited, and more is by no means always better, and is often worse. These awkward facts get shoved into the background of our common wisdom by the bright lights of advertising and medical news that shine incessantly on the “breakthroughs” in medical progress and the drugs that you should “talk to your doctor about.” By saturating our sources of information, the medical industry has convinced most Americans that the answer to almost every health problem can be found in a brand-name pill or high-priced medical procedure.

That’s the bad news. And it’s very bad, costing Americans hundreds of billions of dollars a year and, even worse, compromising our health and quality of life. But there is good news, too—and it’s enormously good: the evidence from study after study, including gold-standard randomized clinical trials, shows that we can usually do a great deal more to maintain our own health than the medical industry, particularly the drug industry, promises it can do for us.

The goal in this chapter is not to reject medical care, but to use the best available scientific evidence to place it in the proper perspective. Exposing the distortions of commercially driven medicine is an essential part of this process, but still it is important to remember that about two-thirds of our medical care is beneficial and even lifesaving. The challenge in determining optimal medical care is to identify the boundary between the effective care that truly improves health and the commercially driven care that at best misdirects our efforts to stay healthy and at worst is actually harmful (like routine hormone replacement therapy). These research findings may surprise you—and will probably surprise your doctor even more.

Most postmenopausal women worry about their bones becoming fragile. The National Osteoporosis Foundation states the problem succinctly: “Osteoporosis is often called the ‘silent disease’ because bone loss occurs without symptoms. People may not know that they have osteoporosis until their bones become so weak that a sudden strain, bump, or fall causes a fracture or a vertebra to collapse.” Twenty percent of all women over the age of 50 have osteoporosis and another 40 percent have osteopenia, thinning of the bones that puts the women at risk of developing osteoporosis.

What causes osteoporosis? Healthy bones undergo constant remodeling to repair minor injuries, maintain strength in response to stress, and provide the body with a reservoir of calcium. The bone remodeling process is accomplished by a balance between the activity of cells that absorb the calcium out of existing bone, called osteoclasts, and cells that lay down new bone, called osteoblasts. In women, this balance changes somewhere between the ages of 30 and 45, so that more bone is absorbed than is replaced, leading to the net loss of calcium. As women (and men to a lesser degree) age, the mineral density of their bones naturally decreases, which can lead to osteoporosis.

Hip fractures are by far the most feared consequence. Data from the National Osteoporosis Foundation show that 24 percent of people who suffer a fractured hip die within one year; a quarter of those who had been living independently require long-term care; and only 15 percent are able to walk across a room unaided six months later. A bone mineral density (BMD) test can quickly determine the degree of bone loss in a woman’s skeleton and whether or not she has osteoporosis or osteopenia.

If you are a woman who has reached the age of 50 and has not yet had a bone density test, you are probably thinking about calling your doctor to schedule one as soon as possible. And you are probably comforted to know that there are a number of new medications on the market that can reverse age-related bone loss for women who have osteoporosis or who are at high risk of developing it. But you may want to read on before making the call.

Most women were not even aware of the risk of osteoporosis before the early 1980s. As discussed in Chapter 5, this changed largely as a result of an educational campaign initiated in 1982. Researchers from the British Columbia Office of Health Technology Assessment point out that the campaign succeeded by addressing women’s growing interest in preventive health care and their fear of aging. But it wasn’t until 1993, when a study group hosted by the World Health Organization established clear-cut definitions of osteoporosis and osteopenia, that doctors were provided with straightforward criteria to make these diagnoses and upon which to base their treatment recommendations. According to the WHO study group, a woman has osteoporosis when her bone mineral density (BMD), as measured by a simple x-ray test, is 2.5 or more standard deviations below the average peak bone mass of healthy young adult women. This is defined as a T score of -2.5 or less. Osteopenia is diagnosed when a woman’s T score is between -1.0 and -2.5.

So far this may sound compelling, but a closer look presents a very different picture: The definitions developed by the WHO Study Group are based on the assumption that the young adult skeleton is healthy and that as people age, their bones become progressively more “diseased.” The study group’s criteria, however, ignore the fact that loss of bone mass is a perfectly normal part of aging, especially in postmenopausal women. Simply on a statistical basis, according to the WHO study group’s definition, about half of all women at age 52 who have BMD tests will be diagnosed as having osteopenia, and this percentage goes up quickly with age. Similarly, according to the WHO study group’s definition of osteoporosis, about half of all American women will have the “disease” by the age of 72.

WHO’s definitions transform the majority of healthy postmenopausal women whose bones are aging normally into “patients” having or being at risk of having a frightening bone “disease.” A decrease in T score is usually no more a measure of disease than is the greater amount of time it takes an elderly jogger to run a mile than it did when she was at her peak performance. This reframing of normal aging into a pathological process is reminiscent of Dr. Robert Wilson’s successful campaign to convince women and their doctors that menopause was not a natural event but a hormone-deficiency disease. We fell for that, hook, line, and sinker, with great harm to many women, and only later discovered that Dr. Wilson had been funded by the drug companies. In this case, however, the source of information is the trusted World Health Organization, on which public health officials in every country rely for health information and policy recommendations. Can’t we trust that its recommendations are free of commercial influence and in the best interests of women around the world? Unfortunately, we cannot.

At the time that the WHO study group did its work, there were several new drugs for osteoporosis in the pipeline. The drug companies stood to benefit greatly if definitions of osteoporosis and osteopenia included large numbers of postmenopausal women and if bone mineral density testing was adopted into their routine medical care. It turns out that the WHO study group that developed the criteria for diagnosing osteoporosis and osteopenia was funded by three drug companies: the Rorer Foundation, Sandoz, and SmithKline Beecham. Of course, commercial funding does not necessarily impugn the conclusions of the study group, but its conclusions did happen to be in the drug companies’ interest.

In a 1994 paper published in the journal Osteoporosis International, the WHO study group recommended that “an appropriate time to consider screening and intervention is at the menopause.” If BMD became part of routine care for postmenopausal women—based on the statistical definitions developed by the study group—the drug companies would be assured that millions of women would be seeking billions of dollars’ worth of their drugs, hoping to prevent and treat osteoporosis.

It may be hard to believe, especially with the debacle of routine HRT so fresh in our minds, but there has never been a randomized controlled study done to determine whether there is a benefit to screening women for osteoporosis with BMD tests. There simply is no gold-standard evidence showing that ordering all these tests and prescribing all those drugs is leading to better health for women. Nonetheless, the current recommendations call for women to have a BMD test at age 65 or earlier if there are risk factors for osteoporosis.

In 1995, Fosamax, the brand name for alendronate, was the first of the new generation of drugs approved by the FDA for the treatment of osteoporosis. Fosamax works by attaching itself to the surface of bone, interposed between the osteoclasts and the bone the osteoclasts are trying to absorb. Randomized clinical trials of Fosamax published in medical journals show dramatic reductions in the relative risk of hip fracture for women with osteoporosis. In a study published in JAMA in 1998, for example, women with an average age of 68 and a T score of -2.5 or less who took Fosamax for four years were 56 percent less likely to suffer a hip fracture than women in the control group.

This sounds like very good news for women with osteoporosis, but how many hip fractures were really prevented? With no drug therapy at all, women with osteoporosis had a 99.5 percent chance of making it through each year without a hip fracture—pretty good odds. With drug therapy, their odds improved to 99.8 percent. In other words, taking the drugs decreased their risk of hip fracture from 0.5 percent per year to 0.2 percent per year. This tiny decrease in absolute risk translates into the study’s reported 56 percent reduction in relative risk. The bottom line is that 81 women with osteoporosis have to take Fosamax for 4.2 years, at a cost of more than $300,000, to prevent one hip fracture. (This benefit does not include a reduction of less serious fractures, including wrist and vertebral fractures. Most vertebral fractures cause no symptoms.)

A study published in the NEJM in 2001 showed that even women with severe osteoporosis* derived only small benefit from these drugs. The study randomized women between the ages of 70 and 79 to receive Actonel (the brand name of risedronate, a cousin of Fosamax) or a placebo for three years. Hip fractures were significantly reduced only in the women who already had a spine fracture when the study began (40 percent of the women in the study). One hundred such women would have to take Actonel for about one year to prevent one hip fracture. For the other 60 percent of women in the study without a preexisting spine fracture, Actonel did not significantly reduce the risk of hip fracture. Moreover, the drug appeared to have no beneficial effect on their overall health. There was no difference in the number of serious illnesses (causing death or hospitalization), including fractures, that occurred in the women who took Actonel compared with those who took the placebo. The same result was found in younger women, with an average age of 69, who had been diagnosed with osteoporosis and at least one spinal fracture: fewer fractures but no reduction in the occurrence of serious illness in the women who took Actonel. The net effect of drug treatment on the risk of serious illness in the highest risk women? Nothing—except the cost of the drug.

A study conducted in the Netherlands helps to put these lackluster results into perspective. It turns out that bone mineral density tests identify only a small part of the risk of hip fracture. The study found that for women between the ages of 60 and 80, only one-sixth of their risk of fracturing a hip is identified by BMD testing. Other factors were just as important as T score: increased frailty, muscle weakness, the side effects of other drugs, declining vision, and cigarette smoking. As a result of the WHO study group’s definition of osteoporosis, however, women and their doctors mistakenly latch on to the results of BMD testing as the sole or primary predictor of fracture risk. Routine BMD testing may not be the best way to help women prevent hip fractures, but it is an excellent way to sell more drugs.

While nearly every postmenopausal woman fears osteoporosis, the reality is that two out of three hip fractures occur in women who have reached the age of 80. With 90 percent of hip fractures resulting from falls, it makes sense that the oldest and frailest women would be at the greatest risk. It also makes sense that a broken hip in these frail elderly women often marks the transition to no longer being able to live independently or walk safely without assistance.

Do the osteoporosis drugs protect these women from hip fractures? They don’t appear to. The study of Actonel published in NEJM in 2001 included 3880 women over the age of 80 who had been diagnosed with osteoporosis or who had at least one major risk factor for falls (approximately 80 percent of the women in the study had osteoporosis). Treatment of these women with Actonel was reported in the article to have “no effect on the incidence of hip fracture.” So it looks as though the women who have by far the greatest risk of hip fracture, and for whom the consequences of hip fracture are the most devastating, do not benefit from the drugs that are sold to help women with osteoporosis.

What about using these drugs to prevent osteoporosis? Fosamax and Actonel were approved by the FDA to treat women with osteopenia based on studies that showed that they significantly increase the bone density of these women. It is important to remember, however, that bone density is only a surrogate end point; the real reason for taking these drugs is to reduce fractures, and hip fractures in particular. The study of Fosamax published in JAMA in 1998 (mentioned earlier) also included women with osteopenia. Did Fosamax reduce their risk of fracture? The results show that the risk of hip fractures actually went up 84 percent with Fosamax treatment.* The risk of wrist fractures increased by about 50 percent (that figure may be statistically significant—but this can’t be determined from the data as presented in the article).

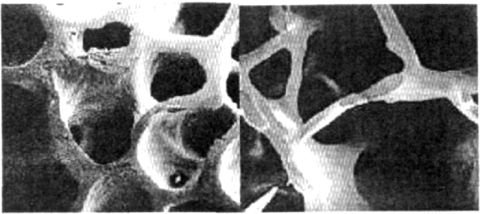

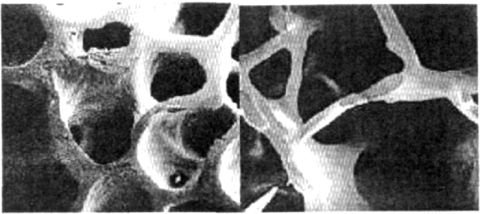

How can it be that drugs approved for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis succeed in increasing bone density but have such limited impact on reducing hip fractures? The answer can only inspire awe at Mother Nature’s elegance. There are two types of bone. Eighty percent of the body’s bone is made up of the hard and dense outer layer called cortical bone. In some areas of the body, bones also have an internal structure of trabecular bone, which works like an organic three-dimensional geodesic dome, providing additional strength in the areas of the skeleton most vulnerable to fracture, such as the hips, wrists, and spine.

The lacelike structure of trabecular bone creates a much greater surface area than the densely packed cortical bone and therefore allows the former to be more metabolically active when the body needs calcium. Its greater metabolic activity also makes trabecular bone more vulnerable than cortical bone to the changed balance between osteoclast and osteoblast activity. As a result, when bone mass starts to decline in women, trabecular bone is lost more quickly than is cortical bone. Once the architecture of these internal struts is lost, there is no structure left onto which calcium can be added. (See Figure 13-1.) The new bone, formed as a result of taking the osteoporosis drugs, is then formed primarily on the outer part of the bone, the cortical bone. This increases the score on the bone density test but does not necessarily contribute proportionately to fracture resistance.

FIGURE 13-1. NORMAL BONE (LEFT) AND OSTEOPOROTIC BONE (RIGHT). REPRODUCED FROM THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND MINERAL RESEARCH 1 (1986): 15–21, WITH PERMISSION OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR BONE MINERAL RESEARCH.

More drugs are now available to “help” women with osteoporosis. Evista (raloxifene) is in a new class of drugs called selective estrogen-receptor modulators, or SERMs. These drugs are designed to protect bones the same way that natural estrogen does, but without the risk of hormone therapy. Sounds great, but research shows that in women with osteoporosis, Evista reduces only vertebral fractures, not fractures of the hip or wrist. Nonetheless, Eli Lilly’s advertising for Evista, according to an FDA letter to the company dated September 2000, “misleadingly suggests” that it does just that. The letter requested that Eli Lilly “immediately discontinue the broadcast of this violative advertisement” along with other marketing material that contained “the same or similar violative claims or representations.”

Two other hormone-like drugs that regulate calcium metabolism are offered to treat osteoporosis; both were tested in women with osteoporosis and preexisting vertebral fractures. Miacalcin, administered by a nasal spray, has an inconsistent effect on hip fractures and vertebral fractures depending on the dose. Forteo, administered by daily self-injection, reduces fractures overall but has not been shown to significantly reduce hip fractures.

Even if loss of bone mass is a naturally occurring part of aging, hip fractures in old age are still a serious threat. So how can older women reduce their risk of hip fractures? As we’ve just seen, there are no magic pills. But there are ways to significantly strengthen bones and reduce the risk of fracture at any age.

Proper exercise and good nutrition are important through all stages of life to build and maintain strong bones. Reaching young adulthood with bones strengthened by routine exercise and a diet with adequate calcium makes future problems far less likely. There is good evidence that exercise builds up trabecular bone, which can then provide the internal support to vulnerable areas of the skeleton later in life.

The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures, sponsored by the NIH, included almost 10,000 independently living women aged 65 and older. Over seven years, women who exercised moderately had 36 percent fewer hip fractures (statistically significant) than the least active women. In absolute terms, the reduction in hip fractures in the women who exercised most compared with those who exercised least was 6 per 1000 per year—twice the reduction achieved with Fosamax. At least two hours of moderate-to-vigorous exercise each week is best.

In a study in Sweden, nursing home residents averaging 83 years of age, one-third of whom had dementia, were randomized to participate in a fall-prevention program (including exercise, medication reviews, hip protectors, and conferences among the staff after falls to minimize the risk of a repeat fall). During the course of the eight-month program, only 1.6 percent of the people in the fall-prevention program suffered a hip fracture compared with 6.1 percent in the control group—a dramatic reduction with no osteoporosis drugs involved (remember, Actonel did not reduce hip fractures in women of similar age).

Because nine out of 10 hip fractures result from falls, engaging in activities that increase strength and balance helps decrease the risk. Strength training is one of the best ways to increase bone density in the spine naturally and prevent falls. Tai chi, a form of exercise often used by elderly Chinese that is becoming popular throughout the world, improves balance and cuts the risk of falls in half for people 70 years of age and older.

Adequate calcium and vitamin D intake is also essential: the daily goal should be 1200–1500 mg of calcium (usually no more than 1000 mg from supplements are needed), and 400 to 800 IU of vitamin D. The cost of generic calcium and vitamin D is about $3.60 per month. Studies also suggest that diets with a higher ratio of animal to vegetable proteins increase the rate of bone loss in women 65 and older. In an observational study, women whose diets contained the highest proportion of animal protein were almost four times more likely to suffer a fractured hip than women whose primary source of protein was vegetables.

This is just a sampling of some of the research that doesn’t get pushed out into the public’s awareness by commercial sponsors. Where might you find additional information about bone health to guide your decisions? Almost half of Americans turn to the Internet for health information. If you go to the website sponsored by Merck, the manufacturer of Fosamax, you will be advised to “know your T score” and told that “If your T score is less than -1.0, talk to your doctor about treatment options.” (Remember, on a statistical basis, half of women in their early fifties have a T score of -1.0 or less, but treating these women with drugs does not decrease, and may actually increase, their risk of fractures.) The information you find on the National Osteoporosis Society website won’t be free of commercial influence, either. This tax-exempt nonprofit institution receives a large amount of drug company support, as indicated in its annual report.

Popular search engines quickly bring up numerous sites with information about BMD testing, many with no apparent ties to the drug industry. A 2004 article published in the International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care shows just how difficult it is to get unbiased information from the Internet. Researchers from the British Columbia Office of Health Technology Assessment identified the consumer health websites most frequently selected by widely used search engines. They then compared the information about bone mineral density testing presented on those sites with the information presented on the websites of noncommercially funded health technology assessment organizations.

The difference in the “information” could not have been greater. Consumer health sites, primarily commercially sponsored, present a consistent message: BMD is a simple, painless test that predicts the risk of fracture from osteoporosis—sounds like apple pie and motherhood. The message on the health technology assessment organizations’ websites was equally consistent: BMD measurements are not good predictors of fracture risk.

One website with good information about osteoporosis (and many other medical issues as well) is offered by the Center for Medical Consumers. Our Bodies, Ourselves is an excellent reference book on women’s health issues.

In the final analysis, the “disease” of age-related osteoporosis is not a disease at all, but the quintessential example of successful “disease mongering.” The drug industry has succeeded in planting the fear that bones will suddenly and without warning “snap” in women who had naively believed they were healthy. This is very far from the reality of osteoporotic fractures, and in the end it harms women’s health by diverting attention away from the constructive, evidence-based, inexpensive, do-it-yourself ways to prevent fractures and maintain overall health. All postmenopausal women should be exercising routinely, eating a healthy diet, taking calcium and vitamin D supplements, and decreasing their risk of falls. Bone density tests are hardly needed to make these recommendations.

If a fraction of the resources spent on the exaggerated risk of osteoporosis were invested in these other ways to improve women’s health, hip fractures could be greatly reduced and overall health greatly improved. Unfortunately, the mainstream women’s health movement seems to have been hijacked by commercial interests, acting more like a wolf in sheep’s clothing or, more specifically, the biomedical-commercial model of health dressed in a healer’s garb, and quite convincingly pretending to care.

The first thing most middle-aged and older people conjure up when they think about the greatest risk to their health is the “number one killer”: heart disease. And the next thing they think about is their cholesterol level. Everyone knows that high cholesterol is the greatest risk factor for coronary heart disease, right? The National Cholesterol Education Program has been remarkably successful in achieving its goal of raising “awareness and understanding about high blood cholesterol as a risk factor for CHD [coronary heart disease] and the benefits of lowering cholesterol levels as a means of preventing CHD.” So successful, in fact, that about twice as many people discuss cholesterol with their doctors during physical exams (67 percent) as are counseled about the importance of routine exercise (34 percent) or as are advised (if smokers) to quit smoking (37 percent). Even the most obvious counseling, advising obese people to lose weight, occurs at only 42 percent of obese people’s yearly checkups.

Heart disease is the number one killer only because eventually, if nothing else kills us, our hearts will give out. Of much greater importance is what robs us of the prime years of our lives. On that score, cancer is far worse; it deprives Americans of twice as many years below the age of 75 as heart disease does. Nonetheless, CHD is still a major health problem that deserves major attention.

The good news is that the death rate from coronary heart disease has dropped quite dramatically since its peak in 1968. Several factors have contributed to this improvement: After the first Surgeon General’s report on the dangers of smoking was issued in 1964, the percentage of adult smokers in the United States declined steadily, from 42 percent in 1965 to 25 percent in 1990. (Smoking is responsible for as much as 30 percent of all deaths from coronary heart disease in the United States each year.) Beginning in 1970, Americans’ per capita consumption of beef, eggs, and whole milk began to decline, leading to a decrease in the percentage of calories derived from saturated fats and cholesterol. And good progress was made during the 1970s and 1980s in reducing the number of Americans with uncontrolled high blood pressure. Largely as a result of these lifestyle changes and improved blood pressure control, the death rate from heart disease in the United States went down by half between 1970 and 1990.

In the second half of the 1980s, the “revolution” in prevention and treatment of heart disease began with the introduction of clot-busting drugs and angioplasty to open up blocked arteries in people who were having heart attacks. The number of angioplasty procedures in the United States tripled in the 1990s, accelerated by the introduction in 1995 of wire mesh stents to keep narrowed coronary arteries from becoming completely blocked. Despite the advent of stents, the number of coronary artery bypass surgeries increased by about a third during the 1990s. In 1987 the FDA approved the first cholesterol-lowering statin drug, Mevacor. Sales of statins climbed steadily, so that in 2002 they took over as the best-selling class of drug in the United States.

What effect did all of these breakthroughs have on the death rate from coronary heart disease? Instead of a dramatic improvement, the rate of decline in the death rate actually slowed during the 1990s (from an average decline of 3.1 percent per year between 1970 and 1990 to 2.8 percent per year between 1990 and 2000). Why didn’t the death rate decline at an even faster rate after all these great breakthroughs in prevention and treatment?

The advances, it appears, diverted attention from the lifestyle changes that had been working so well over the previous two decades. The declining percentage of Americans who smoked abruptly leveled off in 1990, with no further decline through 2002. The decline in per capita beef and egg consumption stalled in the 1990s and actually went up slightly in 2000. The decline in whole milk consumption leveled off, while the increase in the consumption of lower-fat milk peaked in 1990. There was little improvement in the number of Americans engaging in regular exercise. The percentage of obese Americans nearly doubled between 1990 and 2002 (11.6 percent versus 22.1 percent). The number of Americans with type 2 diabetes, which significantly increases the risk of heart disease, increased proportionately. Likewise, the progress made in reducing the number of people with uncontrolled high blood pressure in the 1970s and 1980s stalled in the early 1990s—the total number of people with high blood pressure actually increased, probably as a result of the increasing prevalence of obesity combined with inadequate exercise.

The problem is that all the current medical recommendations, public education campaigns, drug advertisements, and news of breakthroughs in the prevention of heart disease give the benefits of a healthy lifestyle just enough lip service to preempt criticism that these issues are being ignored. The end result is that doctors and patients are being distracted from what the research really shows: physical fitness, smoking cessation, and a healthy diet trump nearly every medical intervention as the best way to keep coronary heart disease at bay.

An article published in JAMA in 1999, for example, shows how much more of a health risk poor fitness is than elevated cholesterol levels. The study collected data on 25,000 executive and professional men at the time they underwent “executive physical exams.” Ten years later, the findings of the exams were correlated with the deaths that occurred from cardiovascular disease (heart attack, stroke, and blood clots) and from all causes to determine which factors contributed the most. It turns out that being among the 20 percent least physically fit (as determined by the results of a treadmill test) is a far greater health risk than is an elevated total cholesterol level (above 240 mg/dL). For the normal-weight men, low fitness accounted for three times as many deaths from cardiovascular disease as did elevated cholesterol. For the overweight and obese men, low fitness accounted for one and a half times as many cardiovascular deaths as did elevated cholesterol. Even more important was the overall risk of death: The normal-weight men with elevated cholesterol levels had no additional risk, but the unfit men had a 60 percent higher risk of death. For the overweight men, elevated cholesterol levels increased the rate of death from all causes by 30 percent, but low fitness increased the death rate by more than twice as much, 70 percent. In absolute terms, poor physical fitness was associated with seven extra deaths per thousand normal and overweight men each year. For comparison, among the very high-risk men in the WOSCOPS study (LDL cholesterol averaged more than 190 mg/dL), not taking a statin was associated with only two extra deaths per thousand men each year.

Don’t despair if you have let yourself get out of shape. The evidence shows that it’s not too late to change your sedentary ways. A study published in JAMA followed almost 10,000 men who underwent exercise testing to establish a baseline level of fitness. They were retested five years later to see if their level of fitness had changed, and then followed for another five years after that. The men who had been among the least fit on the first test but who then improved on the second test cut their risk of dying of cardiovascular disease over the subsequent five years in half, compared with the men who remained among the least fit at both exams. In absolute terms, there were five fewer deaths each year for each 1000 men who became fit.

There is also good evidence showing that physical fitness plays a major role in protecting women from heart disease. In the early 1970s, 3000 women underwent physical exams, blood tests, and exercise testing on a treadmill. The findings were somewhat of a surprise. The typical reason for performing stress tests is to see if the EKG pattern changes in ways that suggest that the heart is not getting enough blood during maximum exercise. It turned out, however, that these changes did not predict an increased risk of premature death. The women who were among the least fit, on the other hand, had far more risk of dying of CHD and more than twice the overall risk of death during 20 years of follow-up than did the most fit women.

Does exercise help people who already have heart disease? Post–heart attack patients randomized to participate in an exercise program had a statistically significant (27 percent) lower death rate than those in the control group. (Most of the randomized studies of statin treatment in post–heart attack patients do not show this much benefit.) It is likely that for secondary prevention of heart disease, statins and exercise together result in lower mortality rates than either alone, but such a study has not yet been done. It would be a risky proposition for a drug company when sales were going so well, especially when the current evidence suggested that the benefits of exercise would outshine the benefits of taking a statin drug.

Exercise isn’t everything when it comes to reducing the risk of coronary heart disease. Diet and other lifestyle changes can also make a big difference, as shown by the randomized studies of primary and secondary prevention of heart disease done in Oslo and Lyon reviewed in the last chapter.

The American Heart Association was so impressed with the findings of the Lyon Diet Heart Study that it issued an “AHA Science Advisory” in July 2000, calling the results an “unprecedented reduction in coronary recurrence rates,” and noting that, “it clearly points to other important risk factor modifications [besides cholesterol levels] as major influences in the development of coronary heart disease.” The American Heart Association’s Advisory concluded with the statement that “it would be short-sighted to not recognize the enormous public health benefit that this diet could confer.”

The expert panel of the National Cholesterol Education Project, on the other hand, was not even impressed enough to mention the American Heart Association’s Advisory in its 2001 cholesterol guidelines. The guidelines were strikingly understated with regard to the spectacular results of the Lyon Diet Heart Study, saying simply “compared to the control group, subjects consuming the Mediterranean diet had fewer coronary events.” There was no mention that the patients in the Lyon Diet Heart Study derived more than two and a half times more benefit from eating a Mediterranean diet than did similar patients taking cholesterol-lowering statin drugs.

Why the cold shoulder? Not only did the Lyon Diet Heart Study show that the Mediterranean diet was much more effective at reducing the risk of recurrent heart disease than the statins, but the decrease in risk came without lowering cholesterol levels. Giving the Lyon Diet Heart Study its due would have called into question the NCEP’s very mission of bringing LDL cholesterol to the public’s attention as the single most important culprit in heart disease. Given the amount of resources committed to educating people about lowering cholesterol compared with helping people eat a healthy diet, one might correctly surmise that drug companies have much more money to spend promoting the “scientific evidence” that supports lowering LDL cholesterol with statins than do the flaxseed, canola, olive, soybean, walnut, and vegetable farmers who would benefit from the widespread promotion of the Mediterranean diet.

The only reasonable conclusion from the best scientific evidence available is that taking a statin while ignoring routine exercise, a healthy diet, and the dangers of smoking may be good for drug company profits but is not good for your health. It’s not uncommon to hear doctors say that we should “just put statins in the water.” Wherever that phrase came from, it is certainly not from unbiased research. The narrow focus on cholesterol levels, statins, and cardiac tests and procedures has succeeded in drawing attention away from far more effective lifestyle changes that cost little more than a shift toward vegetables, whole grains, and unprocessed foods at the supermarket; and a pair of sneakers for a walk or jog around the park or a workout at the gym.

Stroke is the third leading cause of death in the United States. Between 1970 and 1990 the death rate from stroke declined even more quickly than the death rate from coronary heart disease. But then progress in stroke mortality stalled even more abruptly than it did with coronary heart disease.

Why? The risk factors for stroke are similar to the risk factors for heart disease, and the lack of progress after 1990 had an even greater effect. In October 2003, at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Third Annual Primary Care and Prevention Conference, Dr. Wayne H. Giles (an epidemiologist with the CDC) reported that compared with participating in regular exercise, a sedentary lifestyle increases the risk of stroke eightfold. Smoking increases the risk sixfold. High blood pressure increases the risk of stroke by two to four times. And diabetes doubles the risk of stroke.

It’s the same basic story: attention diverted from prevention to lucrative, but less effective, intervention. For example, you may have noticed that strokes today are sometimes called “brain attacks.” The name is actually quite fitting as a description of the problem. Eighty percent of strokes are caused by blockage of an artery that cuts off the supply of oxygen and nutrients to an area of the brain, causing the death of brain cells in much the same way that blockage of coronary arteries causes heart attacks. These are called “ischemic strokes.” (The other 20 percent of strokes, called “hemorrhagic strokes,” are caused by bleeding either within or just outside the brain.) The analogy also holds for the consequences of stroke, which can be as devastating as a severe heart attack. But the analogy does not hold quite so well for the benefit of emergency treatment, which is really what is behind the proposed name change.

The term “brain attack” was introduced into the lexicon by a marketing campaign sponsored by the biotech company Genentech. Genentech makes an expensive clot-busting drug, Activase (generic name, alteplase), that has been used, and perhaps overused, in the United States to treat heart attacks. It is now being pushed as a breakthrough in the treatment of ischemic strokes, at the cost of $2700 per patient treated. The term “brain attack” is designed to focus public attention on the urgency of getting stroke victims to the hospital as quickly as possible so that appropriate treatment (the term “lifesaving” was deleted because it wasn’t true) can be administered.

The results of a manufacturer-sponsored study show that when Activase is administered to 100 properly selected patients within three hours of the onset of stroke symptoms, 12 more patients have minimal or no disability three months later. In order to make sure that a stroke patient is more likely to be helped than harmed by Activase, within those three hours patients must have blood tests, a review of their medical history, a medical examination, and a CT scan to make sure that the symptoms are not being caused by a hemorrhagic stroke, in which case the clot-busting properties of Activase would make the stroke worse. In a paper published in the British Medical Journal in 1999, Danish researchers calculated that if all stroke victims got to the hospital in time (an admittedly unrealistic goal), only one out of 25 would derive any benefit from being given Activase. The Danish researchers concluded that “. . . treatment with alteplase [Activase] may benefit single patients but will have no impact on the general prognosis of stroke.. . . Before it is decided to offer this expensive, potentially harmful, and possibly only marginally effective treatment we suggest that another, much larger, European trial is needed to test the results of the U.S. trial.”

Nonetheless, the 2000 American Heart Association guidelines for the treatment of acute stroke, published in its journal Circulation, upgraded the recommendation for the use of Activase in ischemic strokes from “optional” to “recommended.” Dr. Rose Marie Robertson, president of the AHA, described the nine experts who formulated these guidelines as “independent.” Each of the panelists had been required to file conflict-of-interest statements with the AHA, but no conflicts were reported in the American Heart Association’s guidelines published in Circulation. In a 2002 article published in the British Medical Journal, investigative journalist Jeanne Lenzer reported that the American Heart Association “will not release the conflict of interest statements for public inspection and verification.” However, a subsequent independent investigation reported that six out of the eight experts who supported the upgrade in the recommendations had financial ties to Genentech. In addition, contributions from Genentech to the AHA totaled $11 million between 1991 and 2001, including $2.5 million to help build the AHA’s new headquarters in Dallas.

This investigative work provides a rare look into the financial relationships among the American Heart Association, a drug manufacturer, and respected medical experts. Although there is no evidence of impropriety, one would expect that in the face of a decision as important and potentially controversial as its recommendation on the use of Activase for strokes, the American Heart Association would have gone out of its way to avoid even the hint of financial influence. The end result is that Activase, a very expensive therapy that can help fewer than 1 out of 25 stroke victims, is getting the majority of our medical attention regarding strokes, while exercise, not smoking, control of blood pressure, and prevention of diabetes are all far more effective ways to decrease the terrible toll of strokes and improve overall health at the same time.

Activase hasn’t been getting all of the attention. “Worried about having a stroke?” read the ads in widely circulated magazines and newspapers. They continue, “Pravachol is the only cholesterol lowering drug proven to help protect . . . against stroke.” The problem with these ads is that Pravachol has never been shown to prevent strokes in people who don’t already have heart disease. The manufacturer just publicly repeated the little slip it had made in the original misleadingly titled NEJM article “Pravastin and the Risk of Stroke,” which may have led busy readers to draw the same incorrect conclusion. But in this case the FDA was paying attention. These “false and misleading” ads earned Bristol-Myers Squibb one of only five Warning Letters sent to drug makers for advertising violations in 2003. The FDA seemed particularly irked because, the letter said, it had sent two less severe letters to Bristol-Myers Squibb for similar “overstated” and “unsubstantiated” claims in 2001.

If stroke prevention is the goal, lowering cholesterol with a statin drug is hardly the first strategy we should turn to. According to the data presented by Giles at the CDC conference, an elevated cholesterol level increases the risk of stroke one-eighth as much as diabetes, one-eighth to one-sixteenth as much as elevated blood pressure, and less than a thirtieth as much as a sedentary lifestyle.

With expensive therapies getting all the attention, the very effective and inexpensive basics of stroke prevention have been pushed aside. Engaging in routine exercise, not smoking, eating fish at least once a week, and controlling blood pressure (often with diuretics that cost less than $0.15 a day) would go a long way toward decreasing the amount of harm done by strokes in the United States.

The United States is in the midst of an epidemic of type 2 diabetes. In the past 12 years, the number of people with this disease increased by 78 percent, to more than 16 million, and the number is going up by 1.3 million each year.

There are two forms of diabetes. Type 1 starts abruptly, typically in childhood or adolescence. Its cause is unknown, but it is thought to involve an immune reaction against the cells in the pancreas that make the hormone insulin, perhaps triggered by a viral infection. The vast majority of Americans with diabetes (90 to 95 percent) have type 2. This has a more gradual onset, and is caused by slowly decreasing insulin production in the pancreas combined with decreasing sensitivity to the insulin that is produced. The risk factors for type 2 diabetes are excess body weight, lack of physical exercise, advancing age, and a family history of diabetes.

In the United States, deaths caused directly by high and low blood sugar are rare, but the complications of diabetes are responsible for more than 200,000 deaths and many other serious health problems each year. Almost half of the new cases of kidney failure in the United States are caused by diabetes. More than 80,000 diabetics undergo amputation of a foot or lower leg each year. Diabetes is the most common cause of blindness in American adults. Diabetics have twice the risk of stroke and two to four times the risk of developing heart disease. In 2002, the total cost of diabetes was $132 billion; $92 billion in direct medical costs and $40 billion in disability, work loss, and premature death.

Given the enormous toll of type 2 diabetes in terms of both human suffering and health care resources, one would expect that controlling this epidemic would be a top health priority. But most of what doctors and the public are hearing about diabetes recently has more to do with statin drugs. In April 2004, the American College of Physicians issued clinical guidelines recommending that all diabetics age 55 and older take a statin to protect against cardiovascular disease. One of the important studies upon which these guidelines are based is the widely publicized Heart Protection Study, which showed that treatment of diabetics with a statin drug decreases their relative risk of developing cardiovascular disease by 22 percent and the overall death rate by 13 percent. These sound like important reductions in risk and are the basis of the television advertisements recommending that diabetic viewers “talk to their doctor” about taking a statin. As with so many other studies, translating the relative risk reduction into the absolute risk reduction produces a different picture. More than 100 people with diabetes must be treated with a statin for a year to prevent a single cardiovascular complication.

Though drug therapy for diabetes is getting most of the attention, a number of recent studies show that changes in lifestyle offer much greater potential to control the number of new cases of diabetes and to decrease the health risks for people who already have diabetes. Data from the Nurses’ Health Study, published in NEJM in 2001, for example, show that 91 percent of the risk of developing type 2 diabetes can be attributed to lifestyle factors such as being overweight, getting insufficient exercise, having a poor diet, and smoking. The study found that overweight women had 7.5 times the risk of developing diabetes as normal-weight women, and obese women had 20 times the risk. As a result of the childhood obesity epidemic, even young children in the United States are beginning to develop type 2 diabetes, a disease that until recently was seen only in adults.

Perhaps doctors don’t put much effort into encouraging patients to exercise and lose weight because they don’t believe their efforts will produce positive results. This conventional wisdom is not borne out by the scientific evidence. Two randomized studies, for example, tested the effectiveness of counseling for people at high risk of developing diabetes and came up with exactly the same results. Both studies found that overweight men and women at high risk of developing diabetes randomly assigned to receive exercise and weight loss counseling were 58 percent less likely to develop diabetes than the people randomized to receive no counseling. Among those who received counseling, six fewer people out of 100 developed diabetes each year.

Why is there so little public awareness about the effectiveness of simple measures to prevent diabetes and its complications? A big clue is provided on the nonprofit American Diabetes Association’s website, in an announcement for a program called “Make the Link! Diabetes, Heart Disease and Stroke,” an initiative of the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Cardiology. The home page informs the reader that diabetes management involves more than just blood sugar control: “People with diabetes must also manage blood pressure and cholesterol and talk to their health provider to learn about other ways to reduce their chance for heart attacks and stroke.” There is no mention of the benefit of exercise or diet; for this you must access other web pages. However, the site does mention that the two nonprofit organizations participating in this educational initiative have a number of “corporate partners,” namely AstraZeneca, Aventis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Merck/Schering-Plough, Monarch, Novartis, Pfizer, and Wyeth.

When corporate partners fund the flow of information, the message is likely to accentuate treatment strategies that are in their interest and downplay those that are not. For example, fewer than one-third of the diabetics in the United States get adequate exercise. Simply by walking two or more hours each week, diabetics can lower their death rate by 39 percent. How does this compare with the highly touted benefit of cholesterol-lowering statin therapy? Treating 250 diabetic patients in the Heart Protection Study with a statin drug for one year prevented one death. In contrast, inactive diabetics can get four times more benefit simply by walking for at least two hours weekly, preventing four deaths among 250 formerly inactive diabetics each year.

Similarly, the 13 percent reduction in death rate among those treated with a statin in the Heart Protection Study is greatly overshadowed by the benefit of moderate weight loss. A study done in Sweden treated overweight and sedentary diabetic and prediabetic men with a diet and exercise program for five years. The men in the program who sustained at least a 5 lb. weight loss over the five years of the study had an 83 percent lower death rate than the men who did not lose weight—almost five times more benefit than treatment with a statin. Given the clarity of research about the impact of lifestyle on diabetes, one would expect a special effort by doctors to counsel their diabetic patients about the benefits of exercise and diet. However, according to an article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, only half of diabetic patients were counseled about exercise at their last physical exam.

Another study showed that a 12-week intensive weight-loss program for diabetics decreased their expenditures on prescription drugs and diabetic supplies by two-thirds; and at one year the expenditures were still only half of what they had been at the beginning of the study. In a more effective and efficient health care system, these savings could be reinvested in health promotion campaigns that help people adopt healthier lifestyles, improve the quality of their lives, stem the diabetes epidemic, and at the same time reduce deaths from heart disease, stroke, and cancer. This is the kind of strategy that most Americans probably expect from major nonprofit institutions ostensibly dedicated to improving Americans’ health. But when drug companies are funding the “educational” effort, nonprofit organizations can be used to direct doctors and patients toward their drugs.

The bottom line is that type 2 diabetes is primarily a disease of lifestyle. When doctors and the public are encouraged to pursue drug therapies over changes in health habits, patients miss the opportunity to benefit from the most effective interventions—exercise, diet, and not smoking. Ideal care combines both approaches, with the emphasis proportional to the potential benefit.

Social anxiety disorder used to be a rare disease—that is, before public relations firms went into action representing the makers of the new antidepressants. Today, according to an advertisement for Zoloft, this “medical condition affects over 16 million Americans.” “Sufferers” feel anxious about meeting new people, talking to their bosses, speaking before large crowds, or drawing attention to themselves. (Most of us can think of times when we have experienced these unpleasant feelings.) Pfizer’s website for Zoloft promises that these symptoms can be treated with drug therapy. According to the Pfizer website, depression is an even more common disorder, affecting 20 million Americans each year. Published studies show that treatment with the new SSRI (selective seratonin reuptake inhibitor) antidepressants provides significant benefit to people suffering from both of these conditions.

An exquisitely designed study (sponsored—to give credit where credit is due—by Pfizer, the manufacturer of Zoloft) randomized people suffering from social anxiety disorder into four groups: two of the groups were treated with Zoloft for 24 weeks and two with a placebo. In turn, one of the groups treated with Zoloft received “exposure therapy” consisting of eight 15-minute sessions with a primary care doctor to talk about their symptoms. These patients also received “homework” to do between sessions to help them learn how to identify and break through their social habits and fears. Similarly, one of the groups treated with the placebo received exposure therapy, and the other group no counseling. The patients’ symptoms were then monitored for 52 weeks—the first 24 weeks while undergoing therapy, and then for 28 weeks after the therapy had been completed.

During the first 24 weeks of the study, the patients in all four groups showed significant improvement, but an unexpected finding emerged when the drug was no longer being taken. The patients who had received “exposure” training without Zoloft continued to improve significantly, while the people who had received Zoloft (with or without counseling) showed slight worsening of their symptoms after the drug was stopped. The most likely explanation is that the people whose symptoms were relieved by drug treatment were less motivated to learn how to change the dysfunctional patterns of reaction and interaction that had given rise to their symptoms in the first place. On the other hand, the patients not given medication were probably more motivated to learn how to make these changes, and proved that it could be done successfully. The discomfort of social anxiety is real, but approaching these symptoms as a fundamentally biomedical disorder and treating dysfunctional social skills or habits with a drug makes about as much sense (for all but the most severe cases) as “treating” a splinter with a narcotic painkiller instead of removing it.

A similar picture emerges in the treatment of depression. In a study published in the journal Psychosomatic Medicine, patients suffering from major depression were randomly assigned to one of three groups: a group to receive Zoloft, a group to receive three exercise sessions a week, and a group to receive both Zoloft and exercise for four months. Depression in all three groups was significantly improved after four months of treatment. Six months after the completion of treatment, however, the results were quite different. Depression had recurred in only 8 percent of the people in the exercise-only group. In contrast to this lasting benefit, relapse occurred in 38 percent of the people treated with Zoloft alone and 31 percent of the people treated with both Zoloft and exercise.

This pattern mirrors the study of social anxiety: short-term treatment with an antidepressant medication relieves symptoms but appears to decrease the likelihood of patients making the positive life changes necessary to prevent symptoms from recurring. These randomized controlled studies suggest that at least some depression could be called an “exercise-deficiency disease,” and some social anxiety disorder could be thought of not as a medical disease but as the consequence of dysfunctional patterns of social interaction shown to be amenable to significant improvement by eight 15-minute sessions of counseling with a family doctor.

To see these “diseases” through this evidence-based lens would turn American medicine on its head. The drug companies have a great deal at stake in persuading doctors and the public to limit their view of social anxiety disorder and depression to the biomedical model of disease. They provide persuasive “scientific” explanations for mental health symptoms, while deflecting consideration of the evidence that, in many cases, lifestyle changes and short-term counseling offer more enduring benefit. Not coincidentally, their approach is also the best way to sell more drugs. Though successful in the short term, these biomedical interventions undermine the natural motivation provided by patients’ symptoms to make the real and lasting changes that would lead to sustained improvement in the quality of their lives.

While medical science works toward finding cures for cancer with occasional but all too limited success, we already know a lot about how to prevent cancer. We know, for example, that from 1965 to 1998, lung cancer quadrupled in women, overtaking breast cancer as the number one cancer killer in women in 1986. Smoking not only is responsible for 87 percent of lung cancers but also increases the risk of cancer of the mouth, throat, esophagus, and bladder.

A review of all the studies that looked at the relationship between cancer and exercise showed that the risk of developing some of the most common cancers is significantly reduced by exercise. For example, routine exercise is associated with a 40 to 50 percent reduction in the risk of developing cancer of the colon and with a 30 to 40 percent reduction in the risk of breast cancer. It is also possible that exercise reduces the risk of prostate cancer.

Diet plays a role in about 30 percent of the cancers that occur in developed countries, according to a review of international cancer rates published in The Lancet in 2002. Age-adjusted rates of the four most common cancers (lung, breast, prostate, and colon) are all much higher in the developed countries, and increase when diets change or people move from less to more developed countries.

Another study compared the diet of 2000 people who developed colon cancer with a control group of the same number. Eating a “Western diet”—associated with a higher body mass index and a greater intake of calories and dietary cholesterol—was twice as common among those diagnosed with colon cancer, and the association was strongest among people diagnosed at a younger age.

Consistent with these findings, the patients in the Lyon Diet Heart Study who developed less heart disease on a Mediterranean diet (high in vegetables and fruits, whole grains, and vegetable oil, and low in red meat) also developed 61 percent fewer new cancers compared with the people who ate the “prudent Western-style heart diet” (meaning lower in total and saturated fats than the normal diet).

A study conducted in Canada found that being obese (compared with having a normal body weight) increased the overall risk of developing cancer by 34 percent, with much larger risks for certain cancers: 95 percent for cancer of the ovary, 93 percent for cancer of the colon, 66 percent for breast cancer in postmenopausal women, and 61 percent for leukemia. The researchers calculated that obesity was responsible for 7.7 percent of all cancers in Canada. Given that twice as many Americans are obese as Canadians (31 percent versus 15 percent, in 2003), obesity may be responsible for about 15 percent of cancer in the United States.

Finding medical cures for this terrible disease is desperately important, but we can’t forget that the very best cure is prevention. (The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations for cancer screening are widely recognized as the best available resource. These can be accessed through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.)

The biomedical-commercial approach to health fragments medical care into seemingly separate and unrelated diseases—each with its own cause and its own cure. This distracts people (including health professionals) from the fact that many diseases share the same cause, and that cause is often rooted in lifestyle choices such as poor diet, smoking, and lack of exercise; environmental factors; or economic status. The telling characteristic of the biomedical-commercial approach to health is that regardless of the primary source of disease, the biomedical-commercial approach offers (“pushes” is perhaps a better word) commercially advantageous solutions.

The obesity epidemic in the United States is a perfect example. As awareness of this serious problem grows, attention is becoming focused not on its cause, but on medical treatments to mitigate its consequences. These interventions include preventing heart disease (with statin drugs), mitigating the complications of diabetes (with drugs to control blood sugar, statins to protect the heart, and ACE inhibitors to protect the kidneys), treating strokes after they occur (with an expensive new treatment that actually helps fewer than one out of 25 stroke victims), and relieving the pain of osteoarthritis (with expensive new arthritis drugs). There are also medical treatments for obesity itself: surgery (now even in children) and new medications in the pipeline that are sure to be instant blockbusters.

The real cause of obesity is embarrassingly simple: Americans consume more calories than they need to maintain a healthy body weight. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the average American consumed 500 calories more per day in 2000 than in 1970. Much of this increase is explained by the doubling in the amount of food eaten outside the home from the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s, by which time restaurant and takeout food accounted for one-third of total energy consumption. Restaurants offer high-calorie foods and increased portion sizes to attract customers. Marketing of fast food and high-calorie snacks to children continues to become ever more sophisticated, creating an unhealthy appetite for calorie-rich foods.

Americans’ increase in sugar consumption tells an interesting story. The USDA recommends that the average diet include no more than 10 teaspoons of sugar each day. In the 1950s, Americans’ average daily intake of sugar and other sweeteners was 23 teaspoons. By 2000 this had increased to 32 teaspoons of sweeteners per day, providing an additional 135 calories. (Just one 20-ounce bottle of soda, for example, contains about 16 teaspoons of sugar.) Without any other changes in diet or exercise, a person taking in an extra 135 calories per day gains more than 1 pound each month (3500 extra calories lead to 1 pound of weight gain). The result is perfectly predictable: the percentage of obese adults doubled between the early 1970s and 2000, and during the same period, the percentage of obese children and adolescents increased by a factor of almost four.

Dr. Julie L. Gerberding, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, told the Washington Post in March 2004 that by 2005 the number of deaths in the United States caused by obesity and physical inactivity was projected to reach 500,000—more deaths than are caused by smoking, and almost the same number of deaths caused by cancer. Genetic predisposition and just plain bad luck play a role in most diseases, including those contributed to by obesity, but the greatest determinants of health are the habits, choices, demands, and environment of daily life. Obesity is primarily a social disease—the result of aggressive marketing of high-calorie foods and our physically inactive culture—in much the same way that tuberculosis was largely a social disease of the nineteenth century, the result of overcrowding and the uncontrolled ravages of the industrial revolution. Clearly, the outlook for Americans’ health is not good when one of the key risk factors for most chronic diseases is increasing at an epidemic pace and little is being done to get at the heart of the problem.

What does the research show that we can do to increase our chances of staying healthy? On an individual basis, the answers are remarkably simple. In 2002 the medical journal of the American Heart Association,* Circulation, published an article that reviewed the important studies on coronary heart disease prevention through diet and lifestyle interventions. The article concluded that by following the recommendations that emerge from the scientific evidence, “coronary heart disease can be eliminated to a large extent” among people less than 70 years of age. From the studies presented in this chapter, we see that these same recommendations also apply to the prevention of type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis, and stroke, and help prevent cancer and depression as well. With slight modifications and the inclusion of safety recommendations, here is the list:

1. Avoid tobacco.

2. Exercise moderately for at least 30 minutes or more on most days, engaging in activities such as brisk walking, biking, or gardening.

3. Consume alcohol in moderation, if at all.

4. Eat a healthy diet:

• Cut down on red meat in favor of chicken, fish (including fatty fish at least once a week)*, and vegetable proteins.

• Eat at least a pound of vegetables and fruits every day.

• Limit salt to less than a teaspoon a day.

• Cut down on sugar.

• For cooking, use vegetable oils such as canola and olive oil.

• Minimize intake of saturated fats and cholesterol.

• Consume less than 2 percent of calories in trans fat (the “partially hydrogenated oil” found in many margarines and many baked goods, cookies, crackers, candy bars, and breakfast cereals; check ingredient labels). The optimal daily intake of trans fat: none.

5. Keep your body mass index (BMI) from going over 25 (meaning, don’t be overweight for your height). The good news is that if you do the other things on this list, your weight will be much easier to keep in check.

6. Use seat belts and bike helmets. Most important, don’t drink and drive; and do work within your community to help create a social climate that discourages those most at risk—young adults between the ages of 16 and 25—from drinking and driving.

7. Don’t engage in unsafe sex.

This may sound quite formidable at first, but two studies show just how simple and effective healthy habits can be. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine followed the activity level and health of retired, nonsmoking men in Honolulu between the ages of 61 and 81. During the 12 years of the study, almost twice as many of the men who walked less than 1 mile each day died (41 percent) as the men who walked more than 2 miles per day (24 percent).

Another study, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2003, followed the health of 9700 independently living women, age 65 and older, for up to 12 years. (This study was originally designed to determine risk factors for fractures in older women.) Among the women who were walking 2 miles or less each week at the beginning of the study, those who increased their walking to at least 1 mile per day cut their death rate in half compared with those who remained sedentary. (Both of these studies are observational and could be biased by underlying differences that led to healthier people walking more, though the researchers took all possible measures to exclude this possibility.)

Just knowing these recommendations, however, is not enough: Making positive changes is often complicated by personal inertia and social, economic, and environmental factors beyond the control of individuals and even whole communities. This is where ongoing relationships with primary care doctors and other medical professionals can help to bridge the gap between the science that informs preventive health care and the personal resistance that can make change so difficult. Still, the obesity and diabetes epidemics show that the focus of medicine cannot be limited to the health of individuals. The cultural environment in which our lives unfold also plays a major role in determining our health. Pediatricians and family doctors, for example, cannot possibly stem the tide of childhood obesity by themselves when advertisements for fast food and snack foods and vending machines containing high-calorie snacks saturate children’s environment, presenting a far more compelling message.

Hopefully, in the years to come we will look back and see how ridiculous we were to have believed that biomedicine alone—without considering the health consequences of how we live our lives—could possibly provide optimal health. The measure of America’s recovery from this era of commercially distorted medicine will be the extent to which real and effective encouragement of healthy ways of living is reintegrated into the best medical care available—not replacing, but supported by, the appropriate clinical application of biomedical science.