History

With everything from ancient artworks to Gothic cathedrals and regal châteaux, France is a living history textbook. Even the tiniest villages are littered with reminders of the nation’s often turbulent past. Encompassing everything from courtly intrigue to intellectual enlightenment, artistic endeavour and bloody revolution, French history is far from dull.

Prehistory

The first people to settle in France in significant numbers were small tribes of hunter-gatherers, who arrived around 35,000 to 50,000 years ago. These nomadic tribes lived seasonally from the land while pursuing game such as mammoth, aurochs, bison and deer. They used natural caves as temporary shelters, leaving behind sophisticated artworks.

The next great wave of settlers arrived after the end of the last Ice Age, from around 7500 BC to 2500 BC. These Neolithic people were responsible for the construction of France’s megalithic monuments, including dolmens, burial tombs, stone circles and Brittany's massive stone alignments in Carnac. During this era, warmer weather allowed the development of farming and animal domestication, and humans increasingly established themselves in settled communities, often protected by defensive forts.

Gauls & Romans

Communities further developed from around 1500 BC to 500 BC by the Gauls, a Celtic people who migrated westwards from present-day Germany and Eastern Europe. But the Gauls’ reign was short lived; over the next few centuries their territories were gradually conquered or subjugated by the Romans. After decades of sporadic warfare, the Gauls were finally defeated in 52 BC when Caesar’s legions crushed a revolt led by the Celtic chief Vercingetorix.

France flourished under Roman rule. The Romans constructed roads, temples, forts and grand aqueducts like Provence's Pont du Gard to transport water from one town to another. They also planted the country’s first vineyards, notably around Burgundy and Bordeaux.

oBest History Museums

oBest History Museums

MuCEM, Marseille

Musée d'Art et d'Histoire, Bayeux

Mémorial – Un Musée pour la Paix, Caen

Centre d'Histoire de la Résistance et de la Déportation, Lyon

The Rise of the Kings

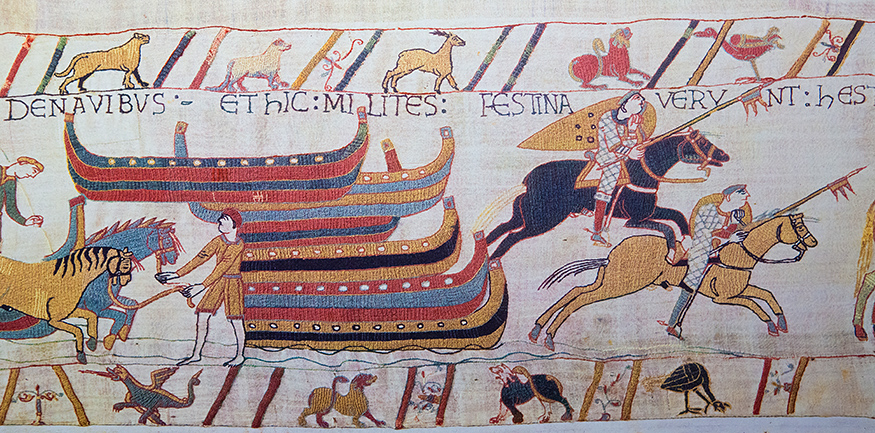

Following the collapse of the Roman Empire, control of France passed to the Frankish dynasties, who ruled from the 5th to the 10th century, and effectively founded France’s first royal dynasty. Charlemagne (AD742–814) was crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 800, around the same time that Scandinavian Vikings (also called Norsemen, thus Normans) began to raid France’s western and northern coasts. Having plundered and pillaged to their hearts’ content, the Normans eventually formed the independent duchy of Normandy in the early 11th century. In 1066, the Normans launched a successful invasion of England, making William the Conqueror both Duke of Normandy and King of England. The tale of the invasion is graphically recounted in the embroidered cloth known as the Bayeux Tapestry.

During this time, Normandy was one of several independent duchies or provinces (including Brittany, Aquitaine, Burgundy, Anjou and Savoy) within the wider French kingdom. While each province superficially paid allegiance to the French crown, they were effectively self-governing and ruled by their own courts.

Intrigue and infighting were widespread. Matters came to a head in 1152 when Eleanor, Queen of Aquitaine, wed Henry, Duke of Anjou (who was also Duke of Normandy and, as William the Conqueror’s great-grandson, heir to the English crown).

Henry’s ascension to the English throne in 1154 brought a third of France under England’s control, with battles that collectively became known as the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453).

Following heavy defeats for the French at Crécy and Agincourt, John Plantagenet was made regent of France on behalf of Henry VI in 1422, and less than a decade later he was crowned king of France. The tide of the war seemed to have taken a decisive turn, but luckily for the French, a 17-year-old warrior by the name of Jeanne d’Arc (Joan of Arc) rallied the French forces and inspired the French king Charles VII to a series of victories, culminating in the recapture of Paris in 1437.

Joan was subsequently betrayed to the English, accused of heresy and witchcraft, and burnt at the stake in Rouen in 1431.

Renaissance to Revolution

During the reign of François I (r 1515–47), the Renaissance arrived from Italy, and prompted a great flowering of culture, art and architecture across France. Lavish royal châteaux were built along the Loire Valley, showcasing the might and majesty of the French monarchy.

The pomp and profligacy of the ruling elite didn’t go down well with everyone, however. Following a series of social and economic crises that rocked the country during the 18th century, and incensed by the corruption and bourgeois extravagance of the aristocracy, a Parisian mob took to the streets in 1789, storming the prison at Bastille and kickstarting the French Revolution.

Inspired by the lofty ideals of liberté, fraternité, égalité (freedom, brotherhood, equality), the Revolutionaries initially found favour with the French people. France was declared a constitutional monarchy, but order broke down when the hard-line Jacobins seized power. The monarchy was abolished and the nation was declared a republic on 21 September 1792. Three months later Louis XVI was publicly guillotined on Paris’ place de la Concorde. His ill-fated queen, Marie-Antoinette, suffered the same fate a few months later.

Chaos ensued. Violent retribution broke out across France. During the Reign of Terror (September 1793 to July 1794) churches were closed, religious monuments were desecrated, riots were suppressed and thousands of aristocrats were imprisoned or beheaded. The high ideals of the Revolution had turned to vicious bloodshed, and the nation was rapidly descending into anarchy. France desperately needed someone to re-establish order, give it new direction and rebuild its shattered sense of self. Enter a dashing (if diminutive) young Corsican general called Napoléon Bonaparte.

Off With His Head!

Prior to the Revolution, public executions in France depended on rank: the nobility were generally beheaded with a sword or axe (with predictably messy consequences), while commoners were usually hanged (particularly nasty prisoners were also drawn and quartered).

In the 1790s a group of French physicians, scientists and engineers set about designing a clinical new execution machine involving a razor-sharp weighted blade, guaranteed to behead people with a minimum of fuss or mess. Named after one of its inventors, the anatomy professor Ignace Guillotin, the machine was first used on 25 April 1792.

During the Reign of Terror, at least 17,000 met their death beneath the machine’s plunging blade. By the time the last was given the chop in 1977 (behind closed doors – the last public execution was in 1939), the contraption could slice off a head in 2/100 of a second.

The Napoléonic Era

Napoléon’s military prowess turned him into a powerful political force. In 1804 he was crowned emperor at Paris' Notre Dame Cathedral, and he subsequently led the French armies to conquer much of Europe. His ill-fated campaign to invade Russia ended in disaster, however; in 1812, his armies were stopped outside Moscow and decimated by the brutal Russian winter. Two years later, Allied armies entered Paris and exiled Napoléon to Elba.

But in 1815 Napoléon escaped, re-entering Paris on 20 May. His glorious ‘Hundred Days’ ended with defeat by the English at the Battle of Waterloo. He was exiled again, this time to St Helena in the South Atlantic, where he died in 1821. His body was later reburied under Hôtel des Invalides in Paris.

A Date with the Revolution

Along with standardising France's system of weights and measures with the metric system, the Revolutionary government adopted a 'more rational' calendar from which all 'superstitious' associations (ie saints' days and mythology) were removed. Year 1 began on 22 September 1792, the day the First Republic was proclaimed.

The names of the 12 months – Vendémaire, Brumaire, Frimaire, Nivôse, Pluviôse, Ventôse, Germinal, Floréal, Prairial, Messidor, Thermidor and Fructidor – were chosen according to the seasons. Each month was divided into three 10-day 'weeks' called décades. The five remaining days of the year were used to celebrate Virtue, Genius, Labour, Opinion and Rewards. These festivals were initially called sans-culottides.

The Revolutionary calendar was ditched and the old system restored in 1806 by Napoléon Bonaparte.

New Republics

France was dogged by a string of ineffectual rulers until Napoléon’s nephew, Louis Napoléon Bonaparte, came to power. He was initially elected president, but declared himself Emperor (Napoléon III) in 1851.

While the so-called Second Empire ran roughshod over many of the ideals set down during the Revolution, it proved to be a prosperous time. France enjoyed significant economic growth and Paris was transformed by urban planner Baron Haussmann, who created the famous 12 boulevards radiating from the Arc de Triomphe.

But like his uncle, Napoléon III’s ambition was his undoing. A series of costly conflicts, including the Crimean War (1854–56), culminated in humiliating defeat by the Prussian forces in 1870. France was once again declared a republic – for the third time in less than a century.

The Belle Époque

The Third Republic got off to a shaky start: another war with the Prussians resulted in a huge war bill and the surrender of Alsace and Lorraine. But the period also ushered in a new era of culture and creativity that left an enduring mark on France’s national character.

The belle époque (‘beautiful age’) was an era of unprecedented innovation. Architects built a host of exciting new buildings and transformed many French cities. Engineers laid the tracks of France’s first railways and tunnelled out Paris' metro system. Designers experimented with new styles and materials, while young artists invented a host of new ‘isms’ (including impressionism, which took its title from one of Claude Monet’s seminal early paintings, Impression, Soleil Levant).

The era culminated in a lavish World Fair in Paris in 1889, an event that summed up the excitement and dynamism of the age, and inspired the construction of one of France's most iconic landmarks – the Eiffel Tower.

The Great War

The joie de vivre of the belle époque wasn’t to last. Within months of the outbreak of WWI in 1914, the fields of northern France had been transformed into a sea of trenches and shell craters; by the time the armistice had been signed in November 1918, some 1.3 million French soldiers had been killed and almost one million crippled.

Desperate to forget the ravages of the war, Paris sparkled as the centre of the avant-garde in the 1920s and ’30s. The liberal atmosphere (not to mention the cheap booze and saucy nightlife) attracted a stream of foreign artists and writers to the city, and helped establish Paris’ enduring reputation for creativity and experimentation.

WWII

The interwar party was short-lived. Two days after Germany invaded Poland in 1939, France joined Britain in declaring war on Germany. Within a year, Hitler’s blitzkrieg had swept across Europe, and France was forced into humiliating capitulation in June the same year. Following the seaborne retreat of the British Expeditionary Force at Dunkirk, France – like much of Europe – found itself under Nazi occupation.

The Germans divided France into two zones: the west and north (including Paris), which was under direct German rule; and a puppet-state in the south based around the spa town of Vichy. The anti-Semitic Vichy regime proved very helpful to the Nazis in rounding up Jews and other undesirables for deportation to the death camps.

After four years of occupation, on 6 June 1944 Allied forces returned to French soil during the D-Day landings. Over 100,000 Allied troops stormed the Normandy coastline and, after several months of fighting, liberated Paris on 25 August. But the cost of the war had been devastating for France: many cities had been razed to the ground and millions of French people had lost their lives.

The French Resistance

Despite the myth of ‘la France résistante’ (the French Resistance), the underground movement never actually included more than 5% of the population. The other 95% either collaborated or did nothing. Resistance members engaged in railway sabotage, collected intelligence for the Allies, helped Allied airmen who had been shot down and published anti-German leaflets, among other activities. Though the impact of their actions was relatively slight, the Resistance served as an enormous boost to French morale – not to mention the inspiration for numerous literary and cinematic endeavours.

Poverty to Prosperity

Broken and battered from the war, France was forced to turn to the USA for loans as part of the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe. Slowly, under the government of French war hero Charles de Gaulle, the economy began to recover and France began to rebuild its shattered infrastructure. The debilitating Algerian War of Independence (1954–62) and the subsequent loss of its colonies seriously weakened de Gaulle’s government, however, and following widespread student protests in 1968 and a general strike by 10 million workers, de Gaulle was forced to resign from office in 1969. He died the following year.

Subsequent French presidents Georges Pompidou (in power 1969–74) and Giscard d’Estaing (1974–81) were instrumental in the increasing political and economic integration of Europe, a process that had begun with the formation of the EEC (European Economic Community) in 1957, and continued under François Mitterrand with the enlarged EU (European Union) in 1991. During Mitterrand’s time in office, France abolished the death penalty, legalised homosexuality, gave workers five weeks’ annual holiday and guaranteed the right to retire at 60.

In 1995 Mitterrand was succeeded by the maverick Jacques Chirac, who was re-elected in 2002. Chirac’s attempts at reform led to widespread strikes and social unrest, while his opposition to the Iraq war alienated the US administration (and famously led to the rebranding of French fries as Freedom fries).

Recent Politics

Following Chirac’s retirement, the media-savvy Nicolas Sarkozy was elected president in 2007, bringing a more personality-driven, American-style approach to French politics. Despite initial popularity, Sarkozy’s time in office was ultimately marred by France’s fallout from the 2008 financial crisis, as well as controversy about his personal affairs – particularly his marriage to Italian supermodel and singer Carla Bruni.

Presidential elections in 2012 ushered in France’s first socialist president since 1995, François Hollande (b 1954). His firmly left-wing policies (including increases in corporation tax, the minimum wage and income tax for high-earners) initially proved popular, but Hollande has had a rocky ride since coming to power.

Scandal broke in 2013 after finance minister Jerome Cahuzac admitted to having a safe-haven bank account in Switzerland and was forced to resign. Two months later France officially entered recession – again. France's AA+ credit rating was downgraded still further to AA and unemployment dipped to 11.1% – the highest in 15 years. Rising anger at Hollande's failure to get the country's economy back on track saw his popularity plunge fast and furiously, and his Socialist party was practically wiped out in the 2014 municipal elections as the vast majority of the country swung decisively to the right. Paris, with the election of Spanish-born socialist Anne Hidalgo as Paris' first female mayor, was one of the few cities to remain on the political left.

France’s economy remains stubbornly in the doldrums, while Hollande's own personal affairs have come under uncomfortable scrutiny – in 2014 his alleged affair with actress Julie Gayet hit the tabloids, and led to the end of his relationship with France’s First Lady, Valérie Trierweiler. With his popularity at an all-time low, it remains to be seen whether Hollande can turn things around.

Timeline

c 7000 BC

Neolithic people turn their hands to monumental menhirs and dolmen during the New Stone Age, creating a fine collection in Brittany.

1500–500 BC

Celtic Gauls move into the region and establish trading links with the Greeks, whose colonies included Massilia on the Mediterranean coast.

c AD 455–70

France remains under Roman rule until the 5th century, when the Franks and the Alemanii invade the country from the east.

987

With the crowning of Hugh Capet a dynasty that will rule one of Europe's most powerful countries for the next eight centuries is born.

1066

William the Conqueror occupies England, making Normandy and Plantagenet-ruled England formidable rivals of France.

1152

Eleanor of Aquitaine weds Henry of Anjou sparking a French–English rivalry that will last three centuries.

1337

Incessant struggles between the Capetians and King Edward III over the French throne degenerate into the Hundred Years' War.

1530s

The Reformation sweeps through France, pitting Catholics against Protestants and leading to the Wars of Religion (1562–98).

1789

The French Revolution begins when a mob arms itself with weapons from the Hôtel des Invalides and storms the prison at Bastille.

1851

Louis Napoléon leads a coup d'état and proclaims himself Emperor Napoléon III of the Second Empire (1852–70).

1905

The emotions aroused by the Dreyfus Affair lead to the promulgation of läcité (secularism), the legal separation of church and state.

1918

The armistice ending WWI sees the return of Alsace and Lorraine, but the war brings about the loss of a million French soldiers.

1939

Nazi Germany occupies France and divides it into a zone under direct German occupation, and a puppet state led by General Pétain.

1944

Normandy and Brittany are the first to be liberated following the D-Day landings in June, followed by Paris on 25 August.

1968

Large-scale anti-authoritarian student protests, aimed at de Gaulle's style of government by decree, escalate into a countrywide protest.

1994

The 50km-long Channel Tunnel linking France with Britain opens after seven years of hard graft by 10,000 workers.

1995

Jacques Chirac becomes president, winning popular acclaim for his direct words and actions.

2002

The French franc, first minted in 1360, is thrown onto the scrap heap of history as the country adopts the euro as its official currency along with 14 other EU member-states.

2004

France bans the wearing of crucifixes, the Islamic headscarf and other overtly religious symbols in state schools.

2007

Pro-American pragmatist Nicolas Sarkozy beats Socialist candidate Ségolène Royal to become French president.

2011

French parliament bans burkas in public. Muslim women wearing the burka can be fined and required to attend 'citizenship classes'.

2012

France loses its top AAA credit rating. Presidential elections usher in François Hollande, France's first Socialist president in 17 years.

2013

Same-sex marriage is legalised in France. By the end of the year, 7000 gay couples have tied the knot.

2014

Municipal elections usher in Paris' first female mayor Anne Hidalgo.