2.

The Power of Family Ownership

Unlike public companies, in which market forces dictate nearly all decisions, family business owners get to write their own rules, fundamentally shaping not just the business but the family as well. Owners define success for the company. They decide who leads it, whether to stay private or go public, and how much of the profits are kept in the business or distributed.

Whether you are an owner, an in-law, a nonfamily manager, or a competitor, you can’t truly know what is going on in a family business until you appreciate the power of family ownership. In this chapter, we will explain this power—which can be used to destroy your family business or sustain it for generations. We describe the five critical rights that allow you to harness the power of family ownership to achieve your desired goals. Understood and wielded properly, ownership is the most important tool to help your family business thrive in the long run.

The hidden pyramid

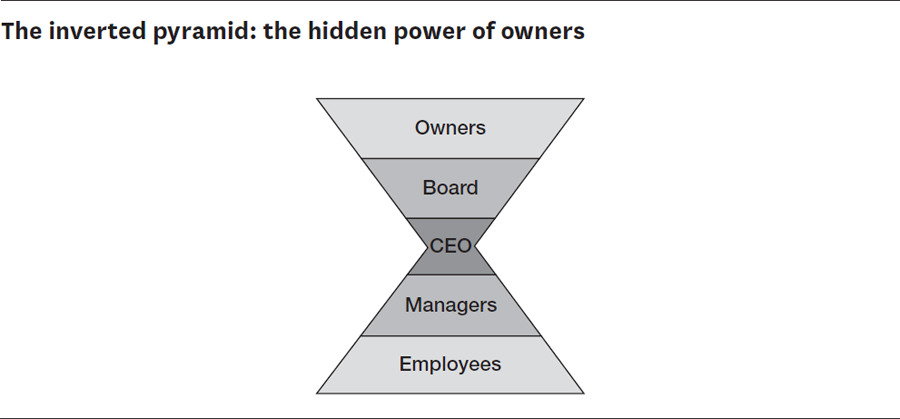

We’re all familiar with the classic corporate pyramid, in which a CEO sits above everyone else. But in family businesses, an inverted, hidden pyramid sits on top of the classic one (figure 2-1). In this power structure, the CEO reports to a board, which is hired by the owners to pursue their objectives. Owners are on top of the entire pyramid structure.

The idea of owners at the top makes little sense at a widely held public company, given their limited influence beyond selling their shares. In the long-term potential of a public company, the owners aren’t terribly important. The board and the CEO are the voices that matter.

But ownership is central to a family business. Think of the difference between renting and buying a house—a renter is transient, seldom investing in making the house a home. But when you own your own home, it becomes an important part of your identity. Think of how long you might have spent deliberating over investing in new windows or whether to update your kitchen. Being an owner of a family business is much the same. Ownership can be the source of resources, of identity, of responsibility. It can bring enormous pride in your family and its legacy, a deep connection to the communities in which you employ people and do business. And ownership can offer what may be the ultimate reward: getting to call your own shots. Whether positive or negative or a mixture of the two, ownership of your family business probably means something significant to you. When we speak of ownership in this book, we are referring not only to direct holders of shares but also ownership that occurs through trusts, which will include trustees and beneficiaries.

The importance of ownership has often been overlooked, even by family business experts. Instead, they have focused on family unity and developing the next generation in the business. These efforts to organize and strive for consensus in the business family led to the creation of globally recognized, valuable approaches such as family councils, family meetings, family constitutions, and protocols (discussed later).

These are important ideas, but they skip over the critical role of family members in making decisions as the owners of the company. The exercise of ownership power is very different from efforts to unify and develop the family. Most families strive to be inclusive and harmonious. By contrast, ownership decisions need to ultimately trace back to the shareholders themselves, a practice that may be imbalanced and exclusive. Some families have tried to use their family governance to make ownership decisions. This approach mixes apples and oranges and typically doesn’t work. Other families focus instead on containing the family so that it does not interfere with the business. While those boundaries can be useful, they can also create a vacuum in which the power of family ownership isn’t exercised by anyone. So, despite all the good work done in the name of organizing the business family, the critical role of ownership has been a particular weakness.

Instead, ownership-related issues have been largely left to lawyers, whose primary job is to protect assets from the government (or other family members). Lawyers are hugely important to certain aspects of protecting family businesses through labyrinthine legal structures such as trusts, estates, and shareholder agreements. Because of these difficult structures, family members seldom fully understand how ownership works in their own family business. And of course, other dimensions of ownership beyond the legal—for example, financial, tax, psychological, cultural, strategic, and political—make ownership challenging to grasp. But the powers and responsibilities of ownership are far too important to simply leave to lawyers to map out in complex documents. Misunderstood and misdirected, the power of ownership can destroy what your family has spent generations trying to build.

The power to destroy

In any work setting, people disagree about strategy, money, status, authority, and so on. Family businesses, of course, are no exception. However, conflict can escalate in a family business in a much different way. In a public company, the rules and ruler are clear. The owners delegate most of their power to the board of directors. CEOs may have almost unlimited power to make decisions while they are in office, but even they can be replaced by the board. And when they are fired, that’s the end of the story. A CEO may leave the business (often a lot richer than when they started) but the board’s ability to make such significant decisions is rarely challenged. In a family business, it’s much harder to keep conflict under control.

To see the destructive power of ownership in action, consider the story of Market Basket, a third-generation grocery chain based in Massachusetts and owned by the Demoulas family. During his tenure as CEO, Arthur T. Demoulas, grandson of the founder, grew sales to more than $5 billion in total and nearly doubled the company’s number of employees. Market Basket opened new locations throughout New England at a time when other grocery stores were retrenching because of financial troubles and competition from Walmart and Costco. Affectionately dubbed “Artie T” by Market Basket staff, the CEO became known for his ability to remember employees’ names and his personal connections to them, including attending their weddings and funerals. Artie T created a generous employee-benefits program and even put money back into the profit-sharing program after the 2008 recession so that employees would still get their bonuses. His leadership fostered deep loyalty among his employees and customers.

But Demoulas’s run as CEO came to a crashing halt in 2014, after years of intrafamily fighting over the fate of the company, when he was fired by the Market Basket board. Though the board made the formal decision, the move was engineered by his cousin, and co-owner, Arthur S. Demoulas, whose branch had gained control after a small but important shift in the balance of ownership power. The firing of Artie T led to the resignation of six high-level managers and massive employee protests, including picket lines. Moved by the extraordinary employee loyalty to Artie T, Market Basket customers stayed away, eventually triggering a reported loss of more than $400 million in the process. After months of painful public and private wrangling, Arthur S. Demoulas agreed to sell his branch’s half of the company to Artie T’s branch. Artie T returned as CEO in late 2014 to the jubilant support of his loyal workforce. Market Basket survived the owner battle, but the business had to scramble to get back on the sound economic footing it had previously enjoyed for decades. The damage was real.

The Market Basket saga perfectly illustrates the destructive power of family ownership. Conflict among the owners spiraled into a bare-knuckle brawl that nearly destroyed the business in a matter of months. The two branches of the Demoulas family originally owned the business equally, but after a lawsuit in the second generation, Arthur S’s branch had been granted control of 50.5 percent of the company and gained control of the board. After internal board maneuvering had allowed Artie T to impose his will on the company as CEO, family branch loyalties returned to side with Arthur S in firing his cousin—setting in motion the conflict that threatened the company’s survival. Through their inability to agree on a path forward for the company, the owners almost destroyed one of the most respected, profitable businesses in their industry.

Because the owners of family-owned companies make the rules, they can also break them. Independent boards cannot resolve disputes, since owners can fire the board at will. Absent the involvement of the judicial system, owners have no higher power to appeal to. Unless they figure it out for themselves, conflict can continue to escalate. (For a full discussion of how conflict can spiral out of control in a family business—and how to prevent that fate—see chapter 12, “Conflict in the Family Business.”) When that happens, the power of ownership to destroy what has been built over years and generations can be unleashed. Family businesses rarely survive a civil war among the owners. As one family we work with puts it, “The biggest danger to this company is us.”

These kinds of destructive stories, often played out in public, can make failure seem to be the destiny for many family businesses. This sentiment is reinforced by an often-cited adage about family businesses: the so-called three-generation rule says that only 30 percent of family businesses make it through the second generation, 10 to 15 percent through the third, and 3 to 5 percent through the fourth. According to this rule, few family businesses survive beyond three generations, and the family fortune is lost in the process, too. These disheartening numbers generate anxiety in the third generation in any family business; the generation worries that it will have to beat the odds to survive.

But the adage is misleading. Although the majority of family businesses don’t make it through three generations, this failure rate also applies to businesses of every kind. Making a company last for decades is a great achievement. And no evidence suggests that family businesses are more fragile than are other kinds of businesses. In fact, most lists of the longest-lasting companies in the world are dominated by family companies. The three-generation rule also ignores the possibility that some families may not have been trying to keep their companies for longer or that some families may have sold their businesses and then started something new. For more, see the box “Debunking the three-generation rule.”

This three-generation rule is destructive because it creates an inferiority complex for family business owners, who believe their business, and family, are doomed to fail. That point of view, in turn, creates a self-fulfilling prophecy. Instead of focusing their energy on how to succeed, they worry themselves to failure. Or they are so concerned about the perils that they don’t even try.

The pervasive fear that family businesses can’t survive over generations almost derailed one family we advised. An independent board member had told the founding siblings of a successful business, “Family businesses never make it beyond three generations. If you want your business to survive, you should not pass it down to your children.” The siblings indeed cared deeply about their business and the people who worked there. They also very much valued the idea of leaving this business as a legacy for their family rather than cashing out and giving the next generation the sale money. So, when the siblings were ready to retire, they agonized over whether to sell the business to their long-standing nonfamily managers or pass ownership to the next generation. The board member’s advice had them believing that they had to choose between making their company last and keeping it in the family. But after realizing that, as owners, they didn’t have to assume that their business couldn’t survive to the next generation, they decided to give family ownership a try. They are now well into a successful transition to the next generation, with a thriving business led by nonfamily managers who are bridging the gap between the retiring owners and their children.

Debunking the three-generation rule

A 1980s study of manufacturing companies in Illinois is the basis for most of the facts cited about the longevity of family businesses. The researchers took a sample of companies and then tried to figure out which of them were still around during the period they studied. They then grouped the companies into thirty-year periods based on their longevity to estimate generations.

A few observations about the study are worth noting. First, its core findings are often described incorrectly. Many people interpret the results to say that 30 percent of family businesses only make it to the second generation. But the study actually says that 30 percent make it through the end of the second generation, or sixty years. That’s a thirty-year difference in business longevity, so choose your words carefully!

Second, the researchers found that 74 percent of family businesses made it for at least thirty years, 46 percent lasted for sixty years or more, and 33 percent survived for ninety years or longer. Finally, the study provides no insight on why some businesses disappeared. Although a family dispute or a business issue could have destroyed the company, perhaps the owners simply sold the business and started a new one.

Those caveats aside, the study still raises the question: Do family businesses have longer or shorter lives than do other types of businesses? A study of twenty-five thousand publicly traded companies from 1950 to 2009 found that on average, they lasted around fifteen years, or not even through one generation. In addition, tenures on the S&P 500 have been getting shorter. If the average company joined the index in 1958, it would stay there for sixty-one years. By 2012, the average tenure was down to eighteen years. A BCG analysis in 2015 found that public companies in the United States faced a five-year “exit risk” of 32 percent, meaning that almost a third would disappear in the next five years. That risk compares with a 5 percent risk public companies faced in 1965.

The data can be interpreted another way: making a business last for decades is hard and, at least for public companies, is getting harder. The studies do not indicate that family businesses are fundamentally flawed with grim survival rates. In fact, the data suggests that the average family business lasts far longer than a typical public company does.

The power to sustain

Owners no doubt have the power to destroy. But we have learned a different lesson in our work: the owners of family companies also have the power to build enterprises that can be sustained for generations.

Take, for example, the amazing story of Italian winemaker Marchesi Antinori, which was established in 1385 and has survived as a family business for more than six centuries. Among many other crises, Marchesi Antinori has survived default from the English royals as bankers, World War II, and the 1980s methanol crisis, which killed scores of people who had drunk certain wines from the Piedmont region in Italy and which threatened to shut down the then $900 million Italian wine export industry. By 2020, the business was in its twenty-sixth generation of ownership by the Antinori family.

While its longevity has certainly involved some good fortune, the owners have also made specific decisions to sustain the business from generation to generation. For example, the practice of passing control of the business to one male descendant had always ensured that the land and business remained united rather than divided up and that there was a family member who dedicated his career to winemaking. The twenty-sixth generation has no males, however. Instead, patriarch Piero Antinori has three daughters: Albiera, Allegra, and Alessia. This presented a dilemma: “I’m from a different generation, and women didn’t participate in the business affairs of the family,” he told us. But Piero’s daughters began to show interest in managing and owning the business together. Rather than giving the business to one of his daughters, Piero ultimately decided to make them all owners. The connection between ownership and being active in the company remains, but now three voices will decide instead of one.

Part of continuing the legacy has been an explicit investment in developing the next generation. As Piero likes to say, “people are like vineyards. It is important to understand their qualities and potential, but also to sow seeds in the right kind of soil so that they can blossom and grow to the best of their abilities.” Piero started teaching his daughters about his love of wine and the business when they were young girls, bringing them on business trips and enabling them to develop early relationships with the business, the employees, and the work.

The Antinoris have made other decisions that have enabled both generational development and financial stability. For example, they always remain fiscally conservative, incurring low debt levels, financing growth through retained earnings, and diversifying their holdings only within their concentrated focus on wine.

For companies like Marchesi Antinori, family ownership has become a source of advantage that helps them thrive in an increasingly competitive marketplace. Family businesses have greater employee retention and engagement, a longer-term orientation toward investments (as opposed to focusing on quarterly results), and more trusted relationships with customers (as confirmed by the Edelman Trust Barometer) than do public companies. And compared with public companies, family enterprises make big decisions faster and better align the interests of owners and managers.

For most of the last century, those benefits have been largely outweighed—at least in the advanced economies of North America and Europe—by the limits on growth that come from lack of access to outside capital, especially through selling ownership to the public. In the race to scale, family companies were at a marked disadvantage. But the game has changed. In the 2015 list of the Fortune 500, 84 percent of CEOs agreed with the statement “It would be easier to manage my company if it were a private company.” These CEOs believed that “surviving the new technological revolution requires long-term thinking and smart investment. But public shareholders . . . are demanding short-term results. Public-company CEOs are caught in the crosshairs.”

So, rather than believing that your family business is somehow doomed to failure, realize that it has the potential to build a sustainable competitive advantage in the twenty-first-century economy. (For more on this point, see “Why the 21st Century Will Belong to Family Businesses,” cited in the “Further Reading” section.) Your decision to sustain the company can help it succeed beyond any others. And that’s good not just for the owners of family businesses, but for society as well. Family companies have been shown to be better employers and more committed members of their communities. At their full potential, these businesses represent capitalism at its best.

The five rights of family owners

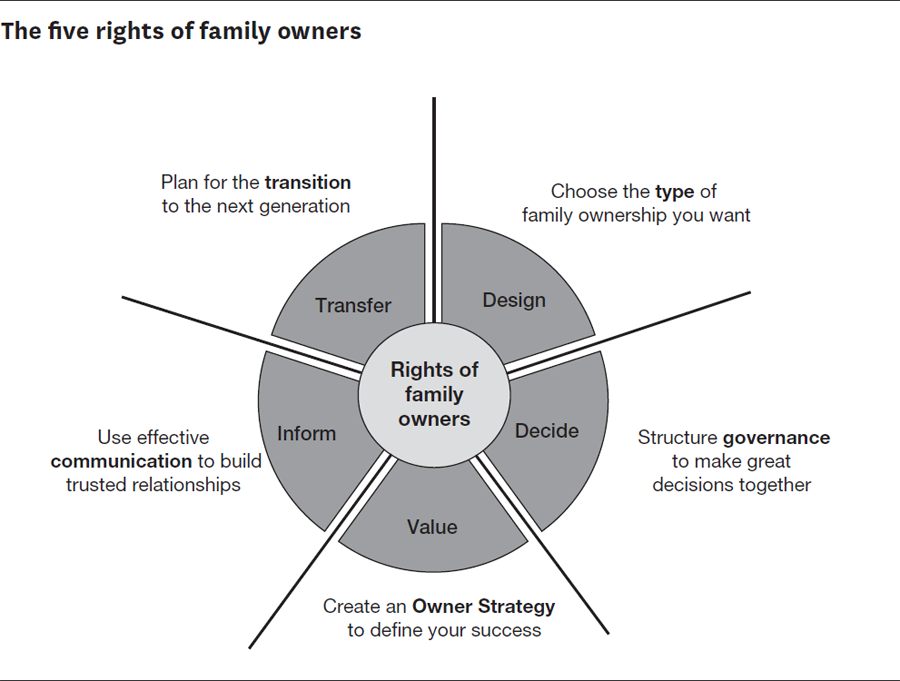

The power to destroy or sustain a family business comes from the owners’ unique ability to make choices that influence virtually every aspect of their companies. Ownership can be considered a series of rights. Exercising these five rights gives owners the power to shape not only the business but also the business family:

- Design. Owners have the right to decide what type of family business they will create. Only they can determine what they will own together, who is eligible to be an owner, and how ownership control is divvied up. Through those choices, the owners design their family business.

- Decide. Owners have the right to make every decision involved in running the business, if they so desire. They choose which decisions to keep for themselves and which to delegate to others. They also determine how decisions will be made, whether by majority rules, unanimity, or some other way. And they can choose to make each decision as situations arise or to establish policies that set precedents in advance. In doing so, owners exercise their right to decide.

- Value. Owners have the right to define success as they see fit. They can maximize shareholder returns, much as public companies do, or sacrifice returns for nonfinancial objectives such as environmental sustainability. Owners can also determine how much of their annual profits they retain in the company or instead pay out in dividends. And they can decide whether to maintain total control over the company or relinquish some of it by bringing on equity partners or taking on external debt.

- Inform. Owners have the right to access information about their business, in particular, how it’s performing financially and who owns what. This access, in turn, gives the owners the right to determine what to share with others, including family members, employees, and the community. If a business goes public, owners give up much of this right as part of meeting disclosure requirements. When a business is private, the owners choose how much of their information to make available both to those inside the company and to those outside it.

- Transfer. Finally, owners have the right to choose how and when to exit ownership. Owners can decide who will own the business after them, what form that ownership will take (e.g., shares or trust), and the timing of the transition. Transfer rights have varying levels of restrictions, depending on where the owners live. For example, in the United States, owners can essentially sell or give their companies to whomever they want, except if the shares are held in a trust, which sets out specific requirements. In Brazil, by contrast, inheritance laws require owners to distribute 50 percent of their assets equally among their children and spouse. The owners have flexibility for the other half. While the degree of discretion varies, the decision about who receives ownership in the company and when they receive it is up to the current owners.

The key to longevity of a family business lies in how its owners exercise these five core rights (figure 2-2). Understanding and effectively exercising these five rights leads to the long-term success of a family business. But misunderstanding or misdirecting those rights can also destroy what a family has spent generations trying to build.

Owners need to work together as they make these choices (detailed in part 2). The specific choices made are often less important than whether all the owners are behind them. And these choices have to be revisited over time. What worked brilliantly in one generation may sow the seeds of collapse in the next.

We won’t sugarcoat our point: without the hard (and smart) work of the owners, family, employees, and others, family businesses all too often naturally implode. It takes energy to keep the inevitably competing interests from destroying the company, and it takes work to sustain a family business across generations. But we clearly lay out the path in this book. You and the other owners of the business have the power to sustain the company if you cooperate. United you can stand, divided you will fall.

Take a moment to capture how you are wielding the power of ownership today. To see this information in an easy-to-visualize format, make two lists. In the first list, note the major actions you have taken to help sustain your family business. They might be tangible things, such as a shareholder agreement or a dividend policy, or less tangible things, such as a next generation that is committed to the business or annual vacations that strengthen family bonds. For the second list, write down the issues that you think create the biggest risk of a major rift in your family business—which issues, if unaddressed, could destroy your family business. They may be current conflicts or ones that you see coming down the line.

Review this initial inventory with others in your family business—next-generation owners, extended family members, and trusted advisers and employees. And come back to it after you finish reading the book. Doing so will help you develop greater insight into your powers as owners and the actions you can take to sustain your family business. You should ultimately see a path to building on the strengths of your family business and addressing its vulnerabilities.

Our message to you is this: you must understand ownership if you want your family business to last. You can hire an outside management team or bring in independent directors for the board. But ownership is the one thing in your family business you can’t outsource. In the next part of the book, we will explore each of the five rights of family owners and help you understand how you can thoughtfully exercise them to create a platform for multigenerational success of your family business.

Summing up

■Ownership is what unites family businesses of all sizes around the world. Companies owned by people related to each other are fundamentally different from those owned by investors who have delegated most of their rights to the board.

■Family ownership brings with it a destructive power that is activated when the owners are divided. Nothing can ruin a great business faster than acrimony among the owners.

■Beware of the myth of the three-generation rule. Despite the challenge of ensuring longevity for any business, there is no evidence that family businesses are more vulnerable than other kinds of businesses. To the contrary, most of the longest-lasting companies in the world are family owned.

■Family owners have five key rights: design, decide, value, inform, and transfer. In part 2, we will discuss how to exercise these rights to create lasting success for your business.