![]()

FEW PEOPLE FROM THE DEVELOPED COUNTRIES OF THE WEST HAVE visited Kumasi, about 160 miles northwest of Ghana’s capital, Accra, even though getting there is much easier now than it was a few years ago. Kumasi Airport has thirteen flights daily to Accra, serviced by airlines such as Antrak Air, Fly540 Ghana, Africa World Airlines, and Starbow, with one-way fares starting as low as $20.1 With a population of about two million, Kumasi, hometown of former United Nations secretary general Kofi Annan, is roughly the size of Houston, although its population density (21,000 per square mile) approaches New York’s.2 The capital of the Ashanti region, the so-called Garden City, has long been a center of timber and gold production.

The people of Kumasi are active consumers of basic, cheap goods. They are not yet part of the massive global audience for midrange and premium brands. Shopping activity centers on West Africa’s largest open-air market, Kejetia, a ramshackle collection of eleven thousand tin-roofed stalls. Multinational companies are scarce here. The leading hotel built to international standards is a Golden Tulip, owned by the French company Groupe du Louvre. Kumasi has a Standard Chartered Bank Ghana branch and eight branches of Nigeria’s Fidelity Bank. Only a few companies from developed economies have a presence in Kumasi. (Starbucks sells Kumasi-brand coffee in the United States, but there is no Starbucks in town.) And why should they? Kumasi is a poor backwater in a poor country. Ghana’s per capita income last year was about $3,880—163rd in the world.3

But Kumasi—and the thousands of emerging cities in emerging markets like it—is where the future of many companies will lie. Most of them just don’t know it yet. As is the case with many developing world cities, it is on the verge of reaping the fruits of a radically condensed cycle of economic transformation.

The sweeping industrialization of emerging economies has shifted the center of gravity of the world economy east and south. Internal migration in those countries, from the farm and village to the city, is fueling astonishing growth. And it has happened at a speed never before seen in history. These developments are powering an explosive growth in demand, which compels us to reset our intuition. The megacities of these emerging economies—such as Shanghai, São Paulo, and Mumbai—are already on the radar of global companies. But the truly dramatic consumption growth will be in cities that most would find hard to locate on a map today, like Kumasi.

SHIFTING ECONOMIC CENTER OF GRAVITY

From the year 1 to 1500, the world’s center of economic gravity*—a measure of economic power by geography—straddled the border between China and India, the countries with the globe’s largest populations. But urbanization, and the industrial revolutions that accompanied it, started in Britain and then swept across continental Europe and the United States. As it did so, the center of gravity moved inexorably to the north and west—first to Europe and then toward North America. During World War I, the center of financial power hopped the Atlantic from London to New York. The shift was reinforced by two world wars, the effects of the Depression in Europe, and the spread of Communism in Russia and China. The East stagnated while the West, led by the United States, powered ahead. By 1945, the United States stood virtually alone as a vibrant global economic power.

The foundation for a trend break was laid in the decades following World War II. In the second half of the twentieth century, the economic pendulum gradually began to swing back to the East. Starting in the 1950s, Europe recovered, and Japan, embarking upon a remarkable recovery, rebuilt its industry. It grew to become the second-largest economy in the world by the late 1980s. Japan was quickly joined by South Korea. The process accelerated when Asia’s slumbering giants began to stir. Then, finally, economic reform took hold in the world’s two most populous nations.

China began to liberalize its economy in 1978, and it has enjoyed a remarkable three-decade period of growth. India began to integrate into global markets and shift into higher gear in the 1990s, propelled by its rapidly rising information technology sector. Through the 1990s, developed nations still dominated the global industrial landscape. The United States was the world’s largest manufacturer, and Japanese and Western European countries dominated the rankings of manufacturing giants. By 2000, the United States, with 4 percent of the world’s population, accounted for about one-third of economic activity and about 50 percent of the world’s global market capitalization. But these figures belied a shift that was gathering strength. Between 1990 and 2010, the world’s center of economic gravity moved more quickly than at any other time in recorded history.4 The shift in economic activity to emerging regions powered through the 2008 financial crisis and the resulting global recession. While Europe remained mired in recession, Japan struggled to exit its lost decade, and the United States muddled through a low-growth expansion, the developing world decisively picked up the mantle of economic leadership. Of the $1.8 trillion of new global economic activity in 2013, China alone accounted for $1 trillion, or 60 percent of it. That country is now the world’s largest manufacturer.5

It’s not just China. Emerging economies such as India, Indonesia, Russia, and Brazil are now major forces in global manufacturing. Manufacturing value added has doubled in real terms since 1990, from $5 trillion to $10 trillion today, and the share of that value added generated by large emerging economies has also nearly doubled, from 21 to 39 percent, over the past decade.6 The share of global foreign direct investment going to emerging and transitioning economies rose from 34 percent in 2007 to 50 percent in 2010 and to over 60 percent in 2013.7 The growth is just a foreshadowing. Between now and 2025, those regions together will grow 75 percent more rapidly than developed countries, and annual consumption in emerging economies will reach $30 trillion, accounting for almost half of the global total.8 By 2025, the economic center of gravity is expected to be back in Central Asia, just north of where it was in the year 1.9

The pace and scale of forces at work are staggering. Britain took 154 years to double economic output per person, and it did so with a population (at the start) of nine million people.10 The United States achieved the same feat in fifty-three years, with a population (at the start) of ten million people. China and India have done it in only twelve and sixteen years, respectively, each with about 100 times as many people.11 In other words, this economic acceleration is roughly 10 times faster than the one triggered by Britain’s Industrial Revolution and is 300 times the scale—an economic force that is 3,000 times as large.

THE URBAN CENTURY

Why now? An underlying trend is at work that supports and enables the developing world: urbanization. People have been moving to cities for centuries, attracted by the possibility of higher income, more opportunity, and a better life. But the scale and pace of today’s urbanization is without precedent. We are in the midst of the largest mass migration from the countryside to the city in history.

The population of cities globally has been rising by an average of 65 million people a year over the last three decades—equivalent to the entire population of the United Kingdom—and the growth has been heavily driven by rapid urbanization in China and India.12 While Europe and the United States urbanized in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and Latin America in the second half of the twentieth century, China and India, each with a population of more than a billion, are now in the middle of their urban shifts. “Urbanization is not about simply increasing the number of urban residents or expanding the area of cities,” said Chinese premier Li Keqiang. “More importantly, it’s about a complete change from rural to urban style in terms of industry structure, employment, living environment, and social security.”13

For many in China, the change can’t come soon enough. For example, Ta Ping village, in the Qinling Mountains, has a population of 103. About ninety minutes outside bustling Xi’an, it has about forty yards of paved road that are flanked by a couple of dozen buildings with terra-cotta roof tiles. It’s common to see braids of drying corn nailed to the outside walls of the houses, which hold bare lightbulbs, wood-burning stoves, cement floors, and televisions. Here, twenty-eight families scratch out a meager existence. The able-bodied seek work in the cities, and the rest go into the mountains to gather herbs, grow some soybeans and corn, or subsist on extremely meager pensions of about 80 renminbi ($15) per month. “How should I be happy?” asks twenty-four-year-old Teng Ling Dang. “I’m poor, and my parents have illnesses.” Teng, who didn’t complete primary school, earns 70 renminbi (about $12) per day working at a brick factory in Luan, a nearby city. His marriage prospects are poor because he doesn’t earn much money. And he can’t leave for a higher-paying job on the coast because he must take care of his parents.14

Some 400 million people in China live in similar conditions, and the government is engineering their move to the city. “Urbanization,” notes Stephen Roach, the longtime Morgan Stanley China expert who teaches at Yale, “is an essential ingredient of the ‘next China.’”15 On March 17, 2014, China released a new plan to respond to the flow of rural residents into cities. The central government foresees 100 million more people moving to China’s cities by 2020. Current forecasts call for 60 percent of the country’s population to live in cities by then.16 In the near future, China has pledged to link every city with more than 200,000 people by rail and expressways, and to connect every city with more than 500,000 residents to its burgeoning high-speed rail network.17 As goes China, so goes Asia and the rest of the developing world. By 2025, nearly 2.5 billion people will live in cities in Asia—that’s one of every two urbanites in the entire world.18 In little more than a decade, China could have more than triple, and India double, the number of urbanites the United States has today—about 250 million.

Per capita GDP has risen in parallel with increases in the urbanization rate across regions

SOURCE: UN Population Data; The Conference Board; McKinsey Global Institute analysis

This matters because cities are where a country’s population meets the modern world and the global economy. Cities turn poor peasants into more productive workers and into global citizens and consumers. The current wave of urbanization has played a key role in helping to lift 700 million people out of poverty, most of them in China—thereby meeting the Millennium Development Goal of halving the number of people living in extreme poverty five years ahead of schedule.19

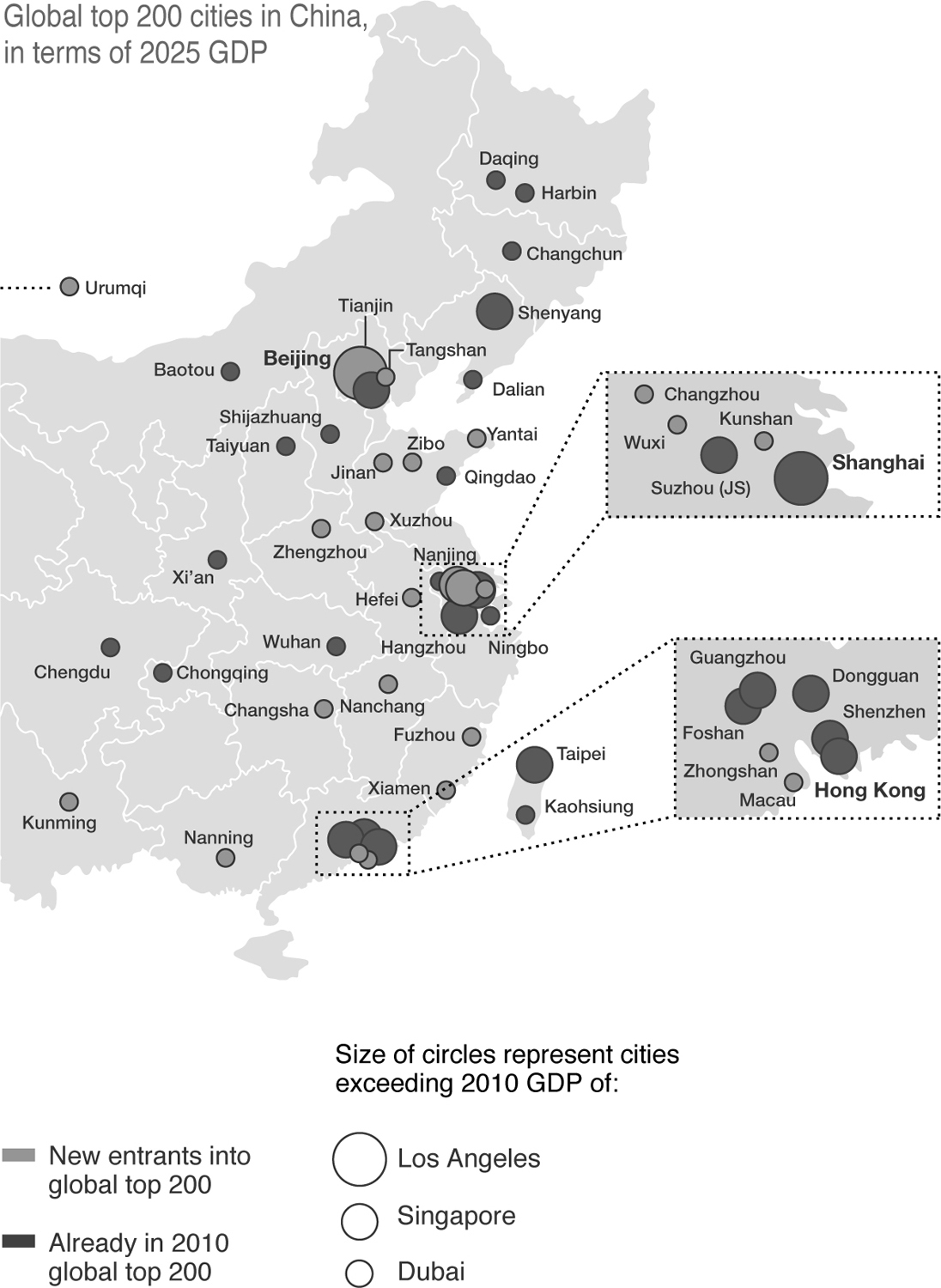

46 of the global top 200 cities will be in China by 2025

SOURCE: McKinsey Global Institute analysis, CityScope Database

Between 1990 and 2025, three billion people around the world are set to become members of the consuming class, defined as having disposable income greater than $10 per day. The vast majority of them will reside in the cities of emerging economies and enjoy opportunities that their parents could scarcely have imagined.20 Never before has so much of the world’s population been as fully engaged in the global economy. The first movie, the first taste of fast food, the first experience with the Internet, the first comprehensive medical checkup, the first bank account: these are all primarily urban experiences.

Tommy Xu grew up in a farming village outside Shanghai and remembers picking frogs out of rice paddies to sell. His village has long since been subsumed by Lujiazui, Shanghai’s gleaming new financial district, which is studded with high-rise towers, parks, and malls. And Tommy, who held his marriage celebration at a KFC in the early 1990s, is now a senior official with a think tank in Beijing. His wife is a marketing executive with a publicly held firm. He drives an Acura. Tommy’s is a singular story, but it is not atypical. In emerging markets alone, we project that this new army of urban consumers like Tommy will spend $30 trillion a year by 2030, up from $12 trillion in 2010.21 They will account for half of the world’s spending.

THE BENEFITS OF CITIES

What’s so great about cities? Throughout history, when people have moved out of farming to jobs in cities, their output has typically doubled. As subsequent generations come of age, their income also increases. To be sure, images of favelas, shantytowns, and slums are part of the landscape. Urban poverty is a real and potentially dangerous phenomenon. But economic historians tell us that for hundreds of years, people living in cities have enjoyed living standards one and a half to three times better than those of their country cousins.

There are many reasons that cities are such powerful engines of growth. Dense population centers generate productivity gains through economies of scale, specialization of labor, knowledge spillovers, and trade. These gains in productivity are reinforced through network effects. Recent research suggests that urban density drives superlinear productivity gains because it affords opportunities for greater social and economic interaction. People and skills attract businesses, which in turn lure migrants from rural areas looking for employment. Companies attract other companies that may want to do business or to share services such as roads, ports, and universities that offer a quick route into the talent pool. They invite ingenuity and the creation of new business models. Fan Milk International, now West Africa’s largest maker of frozen dairy products, grew up in cities like Accra and Kumasi. It pioneered a sales model that worked for its environment. Bicycle vendors rode through the clogged streets with small containers (which could be consumed without being refrigerated). The company has added pushcarts and motorcycles to the mix, and it erects kiosks powered by solar panels (the electricity grid in many of its markets is unreliable) to keep its yogurt and milk cool. Having expanded to seven countries in Africa, Fan counts sales of about $160 million and enjoys high profit margins. Danone in 2013 bought a 49 percent interest in the company at a valuation of $360 million.22

The scale of the city means that urban populations benefit in other ways as well. Cities tend to have more extensive education systems than rural areas, and urban businesses and workers both benefit from the fact that building infrastructure and delivering public services is more efficient and cost effective. Evidence from India shows that it can be 30 to 50 percent less expensive for large cities to deliver basic services, including water, housing, and education, than it is for more sparsely populated rural areas to do so.23 A virtuous cycle ensures that successful cities are able to further boost productivity by attracting better infrastructure, innovation, talent, and economic diversity.

Higher education is a crucial component of economic development. In the United Kingdom and the United States, it is not uncommon to find colleges and universities in rural settings. But in the developing world, they are almost exclusively an urban phenomenon. Kumasi is home to the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, one of the leading science and technology universities in West Africa. Founded in 1950 as a technical school, it’s a full-fledged university set on an eight-square-mile campus, with six colleges, including schools of business, law, and medicine. (Kofi Annan studied there in the late 1950s before leaving for the United States.) It attracts bright, ambitious students from other West African countries as well as Ghana.

ADAPTING TO URBANIZATION

Cities have been around for millennia. A person traveling to Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Latin America, or Asia would encounter common, familiar features—the central square, walls, administrative and government buildings, a large religious complex, the market. Today’s rapid urbanization, however, is altering the very definition and concept of cities. And cities are developing in unpredictable ways. In 1950, New York City and Tokyo were the only two urban areas with more than ten million people. Today, more than twenty geographic agglomerations have populations of more than ten million.24 China has two cities—Shanghai with twenty million people and Beijing with sixteen million—whose populations are roughly the size of the entire country of the Netherlands.25

The movement of the economic future to the cities of emerging economies impels a fundamental shift in the way business leaders need to think about managing growth. The rising urban tide opens up unprecedented access to new consumers, an array of new economic opportunities, and a unique chance to innovate. Infrastructure, smart city technologies, and urban services are in high demand. Huge armies of urban talent are joining the global labor pool. And these densely packed markets function as laboratories in which companies can experiment with different business models, technologies, products, and strategies. Capitalizing on these new growth markets is far from simple; it requires masterful city-level market intelligence, ruthless prioritization, and navigation of risks. However, business leaders need to start seeing these new urban markets as opportunities rather than risks. This is not just a matter of semantics. There’s a big difference between the way resources and talent are mobilized to take advantage of an opportunity and protecting against risk. It’s the difference between playing offense and defense.

Get to Know the Newcomers

In the past, many large companies have done well by focusing on developed economies combined with the megacities of emerging economies. Today, that combination will gain them exposure to markets with 70 percent of the world’s GDP. But by 2025, this combination will generate only about one-third of global growth, which will not be sufficient for large companies trying to position themselves for growth.26 In contrast, between 2010 and 2025, 440 cities in developing nations will generate nearly half of global GDP growth.27

But only about 20 or so of these emerging-market dynamos are likely to be familiar names, such as Shanghai, Mumbai, Jakarta, São Paulo, or Lagos. The other 420 are names that don’t roll off the tips of our tongues. How many people have spotted Surat, Foshan, or Porto Alegre on their strategic radars? Probably not many, despite the fact that all three have populations of more than four million and are considerable economic forces in fast-growing economies. Surat, in western India, accounts for about two-fifths of the nation’s textile production. Foshan is China’s seventh-largest city in terms of GDP. And Porto Alegre is the capital of Rio Grande do Sul, the fourth-largest state in Brazil. Each is growing rapidly and has a vibrant and expanding base of consumers. Each will contribute more to global growth between now and 2025 than Madrid, Milan, or Zurich.

Navigating this new landscape will be far from straightforward. Many of these emerging-market cities aren’t widely known outside their own nations. Operating costs in some of the cities will far exceed those in home markets. Income and demographic trends will vary from country to country and city to city, and even within cities, as the consumption of different products and services starts to rise at different income levels. To make the best decisions, companies will need extensive city-level market intelligence to determine which cities—or clusters of cities with similar characteristics—to focus on.

Create New Services

Consumer ownership models are changing, and cities are at the heart of the shift. Urban populations tend to have higher disposable incomes. In many cities, residents—especially younger ones—are increasingly comfortable renting services rather than buying assets, opening up opportunities for businesses that are smart about spotting consumers’ new needs.

Fueled by technology and assisted by dense urban networks, home-based services and transportation have been perhaps the most prominent examples of innovative services. In 2011, Homeplus, a Korean retail chain owned by British retailer Tesco, opened the world’s first virtual supermarket in a subway station in Seoul. Using an app, commuters can scan the barcodes of life-size pictures of grocery items on the walls and screen doors of the railway platform and have the groceries delivered to their homes the same day. The service was so popular that in one year, Homeplus expanded its virtual stores to more than twenty bus stops. US start-up Instacart now offers customers in ten cities the ability to order goods from multiple stores through one website and get them delivered in one hour. Car-sharing services such as Zipcar and Lyft and transport services such as Uber are becoming increasingly popular among urban residents who have chosen not to purchase their own cars.

The growing ubiquity of such shared services may be hard to replicate outside dense urban environments, but they are not unique to developed economies. In many emerging-market cities, similar services are already routinely offered though informal arrangements with mom-and-pop stores and service providers in local communities and neighborhoods. As incomes rise, consumers in those cities will be increasingly willing to pay for higher-quality services. One example of this trend comes from India, where house calls by doctors were common a generation ago but grew less prevalent as cities became more congested. Today, Portea Medical offers home health care in eighteen Indian cities, using geospatial information to efficiently send the nearest clinician to a patient’s home, capturing health data and uploading it to an electronic platform, and deploying predictive analytics to analyze health trends and recommend interventions.

Tap Urban Talent and Innovation Pools

Cities are increasingly attracting talented, highly educated young people, with larger cities able to attract and retain talent better than smaller cities can. McKinsey research indicates that three-quarters of Europe’s GDP gap with the United States can be explained by the fact that more Americans live in big cities—even American middle-sized cities tend to be larger than large European ones. This matters because larger cities tend to have greater network effects and higher wage premiums compared to rural areas. More densely populated cities are more attractive to innovators and entrepreneurs, who tend to congregate in places where they have greater access to networks of peers, mentors, financial institutions, partners, and potential customers. Cities exhibit superlinear scaling characteristics; with every doubling of a city’s population, each inhabitant becomes, on average, 15 percent wealthier, more productive, and more innovative.28

Companies that seek to tap large cities for talent often worry about the cost of doing business in urban locations. The cost challenge has been made more complex by recent trends that have seen a reversal of the traditional urban ecosystem of businesses locating downtown (or in midtown) and high-skilled residents living in suburbs. Today, many cities are seeing the development of downtown and midtown residential and mixed-use space as workers—increasingly white-collar professionals—seek to live in the urban core.

Firms that locate outside the core—to benefit from lower costs or to locate large assets such as factories and warehouses—can find it harder to attract technical talent that increasingly wants to live near the center of large cities. Companies that can get inside the core can enjoy access to a rich and growing talent base. Universities located in urban settings are benefiting from the influx of talent—making it even more of an imperative for businesses to locate nearby. In June 2014, Pfizer opened a new one-thousand-person R&D facility in Cambridge, Massachusetts, close to MIT. In Pittsburgh, Carnegie Mellon’s Collaborative Innovation Center has attracted companies such as Google, Apple, and Intel, which have set up R&D facilities on campus. Many large cities in the developed world are seeing the growth of innovation districts that attract tech start-ups and small, design-oriented manufacturers. TechCity in London, 1871 in Chicago, 1776 in Washington, DC, and 22@ in Barcelona are all examples of such urban collaborative spaces. In San Francisco, SFMade, a nonprofit set up in 2010, seeks to promote local manufacturing in the city. In New York, Made in NYC has a similar aim, looking to support nearly seven thousand small local manufacturers. And in Europe, organizations such as Design for Manufacturing Forum connect industrial designers, engineers, and manufacturers with the fast-growing “maker” movement to create a decentralized, lean manufacturing ecosystem around urban clusters in cities like Rotterdam.

Think of Cities as Laboratories

Cities are demographic and political microcosms well suited for both private- and public-sector experimentation. Compared with their rural counterparts, city leaders often have greater license to experiment, be it in school reform or regulation of self-driving cars. Private- and public-sector leaders are increasingly collaborating on R&D to find innovative solutions to evolving city needs. As a result, cities are becoming increasingly important partners in innovation—particularly for companies that need to pilot new products and services in self-contained markets before rolling them out nationally.

Some of these “experiments” in urban innovation are driven by new technologies that repurpose legacy installations. Telekom Austria has converted hundreds of disused phone booths in Vienna into electric-car-charging stations where drivers can pay for fuel with a text message. In New York City, a partnership between Cisco and 24/7 has repurposed 250 of the city’s unused phone boxes into interactive information touch screens.29 From technology demonstrations to marketing campaigns, cities can be attractive targets to test new ideas and business models in a rich and diverse environment that is still of manageable scale.

Urban administrators benefit from these innovative pilot programs as well. Take infrastructure as an example. On the outskirts of Lima, Peru, engineers at the local University of Engineering and Technology have found an innovative way to tackle the lack of access to clean drinking water by harnessing one of the city’s most abundant resources: humid coastal air. Essentially, they installed a humidity collector, which turns water vapor in the air into liquid when air gets in contact with the cooler surface of water condensers, and a water purifier on top of a large advertising billboard. The system produces nearly one hundred liters of clean drinking water a day, which flows through a pipe to a tap at the base of the installation.30 In Umea, Sweden, long, dark winters and a chronic lack of sunlight have spurred a local company, Umea Energi, to install therapeutic UV light in thirty bus stops. Commuter traffic has since risen by 50 percent.31 MIT’s Senseable City Lab illustrates the potential of smart city technologies. The lab focuses on studying cities and urban life through new kinds of sensors and hand-held electronics. On its new campus in Singapore, the Senseable City Lab has worked closely with Singapore’s Land Transport Authority and developed three interactive applications that provide insight into the city’s transportation infrastructure.32

Manage Operational Complexity

For businesses looking to locate or expand in cities, operating costs are high and rapidly growing. Emerging-market megacities such as Shanghai and Mumbai are already home to some of the priciest commercial real estate in the world. In built-up areas, infrastructure can get congested easily, further raising the cost and unpredictability of doing business. Some Latin American and Asian cities are beginning to lose their power as engines of prosperity because they are clogged with traffic, scarred by urban sprawl, polluted, and crime ridden. Any visitor to Jakarta is familiar with the traffic gridlock that results from 1.5 million vehicles using roads designed for 1 million. Traffic congestion alone costs Indonesia’s capital city an estimated $1 billion a year in lost productivity.33 In Mercer’s Annual Cost of Living survey, the most expensive city for business isn’t San Francisco or Tokyo. Rather, it’s Luanda, Angola, where a dearth of quality office space and living quarters, poor public services and supply chains, and underdeveloped business and physical infrastructure impose huge costs on corporations.34

On top of land costs, businesses face other challenges, such as stringent zoning rules, land-use regulations, and environmental rules—in emerging and developed cities alike. These regulations may still be manageable for service companies, but businesses that require heavy machinery, land, or warehouses face prohibitive costs of operation. While many large emerging-market cities remain significant industrial hubs in their own right, growing demand for commercial and residential space is squeezing out industrial users. Mumbai’s Parel neighborhood housed textile mills for more than one hundred years; over the past thirty years, the mills have given way to upscale restaurants, premium office space, and luxury hotels and apartments, including World One, slated to be among the world’s tallest residential buildings when it is completed in 2015.

Companies are trying a range of solutions to such pressures—and are finding new opportunities. In March 2014, Panasonic decided to pay bonuses to expatriate workers in China to compensate for their exposure to high pollution.35 In July 2014, Google expanded its office space in downtown San Francisco, buying an eight-story building and leasing 250,000 square feet nearby. The company now has a cluster of offices near the San Francisco waterfront. In Bangalore, the hub of India’s IT industry, companies run their own buses and power generators to ensure that unreliable public transport and electricity supply don’t affect commercial activity. And to provide better reliability of urban delivery, logistics providers are investing in two-tier urban distribution centers and smart trucks with real-time telematics, hoping to minimize delivery delays and reduce unpredictability.

Companies are also trying to partner with city administrations to offer solutions to these challenges. Infrastructure financing and delivery is one area; public-private partnerships were successfully used to build New Delhi’s Metro Rail, modernize Singapore’s water system, develop a public cable-car system in Medellín, Colombia, and invest $3.5 billion in various transportation projects in Vancouver. In March 2014, Kumasi’s government announced the construction of a sky train, an elevated transit system, to relieve chronic traffic. Standard Bank of South Africa is financing the $170 million project.36 Technology and smart apps are other areas where large companies and start-ups have collaborated with cities. Transport for London shared its data to encourage new apps such as BusIT London, which suggests the best bus route for any journey, given the user’s current location; NextBus provides real-time bus information in several cities in the United States and Canada. The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency partnered with tech companies and parking meter providers to develop SFPark, a parking solution that combines new meters with sensors, mobile apps, and dynamic pricing to reduce congestion and parking delays.

![]()

It is easy for the leader of a business to take a quick look at Kumasi, and at the thousands of up-and-coming cities in the developing world, and conclude that his or her company is not missing out on all that much by not being there today. But at a time of rapid, surprising change, snapshots that capture a moment in economic time can be deeply misleading. In this age of Instagram, we must apply new filters to the mental and financial pictures we take. Our intuition—the nerve center that turns images into narratives—has to reset so that it processes the incoming data intelligently. The portraits we take of cities must capture the dynamism underneath the surface and highlight the brightness of opportunities, while toning down the alarming flares of risk. Most of all, they must be able to project forward motion.

![]()

*Economic center of gravity is calculated by weighting locations by GDP in three dimensions and projecting the center to the nearest point of the earth’s surface.