![]()

Accelerating Technological Change

LONDON IS A CITY CHOCKABLOCK WITH ICONS RECOGNIZED BY PEOPLE around the world—Big Ben, Westminster Abbey, Buckingham Palace, and the thousands of black cabs that ply the crowded, twisting roads and lanes. For tourists and locals alike, the black cabs are a quintessential part of the London experience. London cabbies are justly proud of their trade, heritage, and skill. They must pass a notoriously tough multiyear training course, known simply as “the Knowledge,” which requires drivers to memorize over sixty thousand streets.1 On average, drivers take the final exam twelve times before passing. Yet on June 11, 2014, London cabbies decided that they had had enough.2 That afternoon, more than ten thousand black cabs blocked off London’s iconic areas in a wide-ranging strike. They brought Trafalgar Square, Parliament Square, and Whitehall to a standstill. The reason? In a word, Uber.3 To be more precise, they were protesting London’s handling of transport start-ups like Uber, whose business model depends on a GPS-enabled smart-phone app that cheaply and efficiently connects riders to drivers and that acts like a taxi meter. Cabbies argue that the city’s Private Vehicles Act bars privately hired vehicles from having taxi meters.4

Advances in digital technology are fueling the rise of new, nimble competitors that have their sights set on a slice of London’s lucrative taxi market.5 Protection from competition and high barriers to entry have allowed London’s cabbies to thrive, even though they’ve been reluctant to embrace new technology: the knowledge obviates the need for GPS, and most taxis only take cash—and keep prices high. The average journey is estimated to cost about £27.6 Hailo, a smart-phone app that allows customers to hail a black cab virtually, did not launch until the end of 2011.7

Drivers of London’s black cabs—along with those in several other European cities that day—were channeling their anger at San Francisco–based Uber. Since launching in 2009, Uber has been an enormous success, rapidly expanding into more than 230 cities in fifty countries.8 Backed by Google Ventures and private equity firm TPG, among other high-profile investors, Uber in June 2014 closed a round of financing that valued the company at $18 billion.9 Since Uber entered London in 2012, the city has been one of its fastest-growing markets, with over seven thousand drivers active in late 2013.10

As car-hailing apps proliferate—Uber’s competitors include Hailo, Addison Lee, and Kabbee—black cabs have been caught in the slow lane. Hailo, originally designed to work exclusively with black cabs, has responded to Uber’s success by opening up its services to private-hire vehicles, a move seen by many cabbies as a significant betrayal. In response, Hailo’s offices were vandalized.11 Meanwhile, on the day of the June protest, Uber announced that it would welcome black cabs into its service.12

London’s cabbies aren’t alone in finding their once-venerable and impregnable business models rapidly upended with apparent ease. Advances in technology have always disrupted the status quo. But they have never done so across so many markets and at the speed and scale that is being seen today. As digital platforms reduce to near zero the marginal costs of scaling up business activity, such platforms are enabling new business models, new entrants, and even new market models such as peer-to-peer transactions and the “sharing” economy. With lowered barriers to entry, it is now common to see small companies take on incumbents and gain critical mass in a matter of months. The boundaries separating sectors have become blurred, and digital capabilities are often driving the shift of economic values between players and sectors. While companies struggle with technological churn, consumers are big beneficiaries—far beyond the extent captured in official data releases. Take, for instance, the ability to search the Internet, a service provided by Google, Microsoft’s Bing, and Apple’s Siri, among others. Consumers would have happily paid a great deal for this service. As recently as the 1980s, customers paid each time they dialed 411 to get a phone number. But from the outset, web search has generally been free. As a result, it is not captured in official statistics such as GDP. The acceleration of the “metabolic rate” of the global economy has profound implications for all consumers, businesses, and governments. Accelerating technological changes shortens the lifespan of ideas, business models, and market positions. It forces leaders to rethink the way they approach and manage information, the way they define, monitor and respond to competition, and the way they navigate and respond to technological churn. And it also creates significant opportunities for reinvention, growth and differentiation.

ACCELERATING INNOVATION

From the first stabs at mechanization during the Industrial Revolution to the computer-driven revolution we are living through now, technological innovation has always underpinned dynamic economic change. But today is different because, as noted in the introduction, we are in the second half of the chessboard.

In a process that is both gratifying and terrifying, the period between historic breakthroughs has been decreasing by orders of magnitude. More than five hundred years passed between Gutenberg’s printing press and the first computer printer. It then took only another thirty years for the 3-D printer to be invented. Two hundred years separated the spinning jenny, the yarn-producing machine invented in 1764, from GM’s Unimate, the world’s first industrial robot.13 It took only a quarter of that time for Shaft, the world’s most advanced humanoid robot, to be invented. As W. Brian Arthur, a former Stanford economist, who pioneered the study of positive feedback and wrote The Nature of Technology, noted, “With the coming of the Industrial Revolution—roughly from the 1760s, when Watt’s steam engine appeared, through around 1850 and beyond—the economy developed a muscular system in the form of machine power. Now it is developing a neural system.”14

Moore’s law, which holds that the processing power of computer technology doubles every eighteen months, has long underpinned our expectations of technological change.15 Faster, more powerful computers, combined with access to exponentially increasing amounts of data, have altered our vision of what is possible. In the 1990s, sequencing the human genome was a project equivalent to constructing the Panama Canal—a multiyear endeavor that required armies of workers and battalions of steam-powered shovels. A team of scientists spent thirteen years and $3 billion to unlock the mysteries of the human blueprint.16 Today, a $1,000 machine could soon be available that will be able to sequence a human genome in a few hours.17

THE DISRUPTIVE DOZEN

More technological change is coming—faster. The list of possible “next big things” grows longer every day. A lot of noise and confusion surround transformative technologies, with claims and counterclaims that range from the utopian to the catastrophic. We cut through the clutter and highlight the twelve technologies that could truly challenge the status quo in the years ahead.18 They range from the familiar to the more surprising. We estimate that select applications of each of these technologies could generate a potential economic value of between $14 trillion and $33 trillion a year by 2025.19 (Our measure of economic value is a broad one that encompasses measurements such as revenues, money saved through efficiency, and consumer surplus.) The disruptive dozen fall into four broad categories.

1. Changing the building blocks of things. To successfully sequence the first human genome in 2003, it took thirteen years, $3 billion, and teams of scientists from all over the world. Rapid advances in technology mean that the speed of gene sequencing has exceeded Moore’s law. Barely a decade later, in January 2014, Illumina, the world’s leading seller of gene sequencing machines, unveiled the HiSeq X, a supercomputer that can sequence twenty thousand genomes a year at a cost of $1,000 each.20 The rapidly declining cost of gene sequencing is spurring studies in how genes determine traits or mutate to cause disease. Increasingly affordable genetic sequencing combined with big data analytics will allow rapid diagnosis of medical conditions, pinpointing of targeted cures, and potentially even the creation of customized organisms through synthetic biological methods, with applications in agriculture, food, and medicine.

Advances in materials science are another disruptive innovation. The process of manipulating materials at the molecular level has made nanomaterials possible. Such breakthroughs have already transformed ordinary materials such as carbon and clay to take on surprising new properties—greater reactivity, unusual electrical properties, and greater strength. Nanomaterials have already been used in products ranging from pharmaceuticals to sunscreens to bicycle frames. Now, new materials are being created that have attributes such as enormous strength and elasticity and remarkable capabilities such as self-healing and self-cleaning. Smart materials and memory metals (which can revert to their original shapes) are finding applications in a range of industries such as aerospace, pharmaceuticals, and electronics.

The period between historic breakthroughs has been decreasing dramatically

2. Rethinking energy comes of age. In North America, fracking—a combination of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing—has unleashed a shale energy boom that few saw coming. In less than a decade, the price of natural gas has fallen from more than $12 per unit (million British thermal units) to around $4 to $5 per unit in the United States. And as gas supply outstrips demand and prices remain low, producers are turning to fracking for oil in formations like North Dakota’s Bakken Shale. Other unconventional sources are also being explored, including coal-bed methane and methane clathrates.

Meanwhile, even as the unconventional fossil fuel revolution takes off, the cost of renewable electricity generation continues to fall rapidly. Since 1990, the cost of solar cells has dropped from nearly $8 per watt of capacity to one-tenth that amount. Countries around the world—including large emerging economies such as China and India—are working on aggressive plans to accelerate adoption of wind and solar installations and increase the amount of energy they produce. By 2025, solar and wind power could become a source of 15 to 16 percent of global electricity generation, up from 2 percent today, and reduce emissions by up to 1.2 billion tons of CO2 annually.21

Finally, energy storage technologies are also seeing disruption. Technologies such as lithium-ion batteries and fuel cells are already powering vehicles and portable consumer electronics. Prices for lithium-ion battery packs for cars could fall from over $500 per MWh to $160 per MWh by 2025, even as their life cycle increases. Such advances in energy storage have the potential to make battery-powered vehicles cost competitive. When used in the electric grid to improve reliability, reduce outages, and enable distributed generation, energy storage can dramatically improve the efficiency of our utility grids and bring electricity to remote and underserved areas around the world.22

3. Machines working for us. Industrial automation has been around for several decades, and the robots on the factory floor are now changing fast. Past generations of robots were isolated from humans, sometimes bolted to the floor or even caged. They cost hundreds of thousands of dollars and needed engineers to program instructions into them, a process that could take several days. Today, a new generation of increasingly capable robots with enhanced perception, dexterity, and intelligence is being developed thanks to advances in machine vision and communication, sensors, and artificial intelligence. One example is Baxter, a $22,000 general-purpose robot that can work safely alongside humans. It can learn a new routine simply by having a human guide its arms through the motions needed for the task. Baxter even has a “head,” which it nods to indicate that it has understood instructions, and a “face” with a pair of eyes, which take on different expressions. As their capabilities grow, robots are performing tasks once considered too expensive or delicate to automate. Their application extends beyond industry to services, robotic surgery, and even human augmentation.

Autonomous vehicles are another disruptive technology that has made dramatic advances in a single decade. In 2004, DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) funded the Grand Challenge, a competition that offered $1 million to the first driverless car that could drive 150 miles across the Mojave Desert. Nobody won the prize money; the best-performing car (from Carnegie Mellon) managed a little over 7 miles. Ten years later, Google’s fleet of self-driving cars has already logged 700,000 miles in city streets—with the only accident occurring when a human was operating one of the Toyota Prius cars. Today, new car models offer the latest advances in driver-assist systems, such as braking, parking, and collision avoidance. By 2025, the driverless revolution in ground and airborne vehicles could be well underway, especially if the regulatory framework keeps pace with the changes.

Finally, additive manufacturing technologies could become another disruptive force in production. While they are not new, 3-D printers are becoming more prevalent because of better technology and performance, new materials, and falling prices. Their use in simple consumer goods and prototypes is widely known. Today, they are also used in medical and dental products, such as hearing aids, dental braces, and prosthetic limbs, and are starting to be used in other high-complexity, low-volume applications, such as aerospace components and turbines. New applications are proliferating. The world’s first 3-D printed car, the Strati (made by start-up Local Motors), was assembled and driven in Chicago in September 2014. Artificial human organs have already been 3-D printed, using a sugar-based hydrogel to create a scaffolding of a kidney or other body part and an inkjet-like printer to spray onto it stem cells from the patient’s own tissue. Over the coming decade, such uses could expand further. The manufacturing process will “democratize” as consumers and entrepreneurs start to print their own products.

4. IT and how we use it. We may think of the mobile Internet as a familiar technology, but with over one billion people already using smart phones or tablets, it is dramatically changing the way we perceive and interact with the world around us. Consider the rapid growth of the Internet of Things—embedded sensors and actuators in machines and other physical objects that are being adopted for data collection, remote monitoring, decision making, and process optimization in everything from manufacturing to infrastructure to health care. Sensors in limekilns can tell operators how to optimize temperature settings; in consumer goods, they can inform manufacturers about how products are being used; and in bridges, they can warn city administrators about maintenance needs. Today, over 99 percent of physical objects remain unconnected, highlighting a vast opportunity.23

Increasingly affordable, capable, and connected mobile computing devices are spurring innovation in services and worker productivity and are creating vast consumer surplus in the process. This trend is only likely to grow in strength as smart mobile technology brings another two billion to three billion people, predominantly from developing economies, into the connected world over the coming decade.24 Cloud technologies are supporting these information trends. Cloud technologies are already making the digital world simpler, faster, more powerful, and more efficient and are changing how companies manage their IT. In the years ahead, cloud technology will continue to spur growth of new business models that are asset light, flexible, highly mobile, and scalable. The technologies will continue to expand, increasingly accompanied by advances in machine learning, artificial intelligence, and human-machine interaction. These changes make it possible for computers to do jobs that it was assumed only humans could perform. From IBM’s Watson supercomputer—which beat human champions on the TV quiz show Jeopardy!—to automated discovery processes in the legal world and even software that can automatically write sports coverage, knowledge work is being automated on a scale we couldn’t imagine just a few years ago.

A DIGITAL, DATA-RICH THREAD RUNS THROUGH IT ALL

Digitization is the common thread running through many of these technology disruptions. At its most basic, digitization is a simple proposition: converting information into 1s and 0s so that it can be processed, communicated, and stored in machines. That simple notion has transformed our lives in the past thirty years in the form of personal computers, consumer electronics, and the global Internet. Now it underlies these new disruptions. Digitization slashes to nearly zero the cost of discovering, transacting, and sharing information. In the process, it creates a deluge of information—big data. Information used to be precious and scarce; think of a book having to be borrowed from a library for only a few weeks. Now it is ubiquitous; according to Eron Kelly, a senior director for product management at Microsoft, “in the next five years, we’ll generate more data as humankind than we generated in the previous 5,000 years.”25 One exabyte of data is the equivalent of more than four thousand times the information stored in the US Library of Congress.26 By 2020, the volume of data could reach more than forty thousand exabytes—an increase of nearly three-hundredfold since 2005. 27

Digitization is changing the world around us in three ways. First, it converts physical goods into virtual ones. E-books, news websites, MP3 files, and other forms of digital media have largely disrupted sales of LP records, cassette tapes, CDs, DVDs, and printed media. In the future, 3-D printing could redefine the sale and distribution of physical goods. Items such as shoes, jewelry, and tools may in the future be sold with the transfer of an electronic file, allowing the buyer to print the object on demand or at the point of consumption.

Second, digitization enhances the information content of many of our routine transactions, enriching them and making them more valuable and productive. Examples include the digital tracking of physical shipments with the use of RFID tags and the use of 2-D barcodes to convey information to consumers.

Third, digitization is creating online platforms that facilitate production and transaction and allow minnows to compete head-to-head with sharks. Online exchanges and platforms like eBay and Alibaba, two of the linchpins of global e-commerce, allow even the smallest companies and individuals to become micro-multinationals. More than 90 percent of eBay commercial sellers export to other countries, compared with an average of less than 25 percent of traditional small businesses.28

The Disruptive Dozen

Twelve technologies have massive potential for disruption in the coming decade

![]()

CHANGING THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF EVERYTHING

1. Next-generation genomics

Fast, low-cost gene sequencing, advanced big data analytics, and synthetic biology (“writing” DNA)

2. Advanced materials

Materials designed to have superior characteristics (e.g., strength, weight, conductivity) or functionality

RETHINKING ENERGY COMES OF AGE

3. Energy storage

Devices or systems that store energy for later use, including batteries

4. Advanced oil and gas exploration and recovery

Exploration and recovery techniques that make extraction of unconventional oil and gas economical

5. Renewable energy

Generation of electricity from renewable sources with reduced harmful climate impact

![]()

MACHINES WORKING FOR US

6. Advanced robotics

Increasingly capable robots with enhanced senses, dexterity, and intelligence used to automate tasks or augment humans

7. Autonomous and near-autonomous vehicles

Vehicles that can navigate and operate with reduced or no human intervention

8. 3-D printing

Additive manufacturing techniques to create objects by printing layers of material based on digital models

![]()

IT AND HOW WE USE IT

9. Mobile Internet

Increasingly inexpensive and capable mobile computing devices and Internet connectivity

10. Internet of things

Networks of low-cost sensors and actuators for data collection, monitoring, decision making, and process optimization

11. Cloud technology

Use of computer hardware and software resources delivered over a network or the Internet, often as a service

12. Automation of knowledge work

Intelligent software systems that can perform knowledge work tasks involving unstructured commands and subtle judgments

The data avalanche is set to become more powerful only because of a movement toward “open data,” in which data are freely shared beyond their originating organizations—including governments and businesses—in a machine-readable format at low cost. More than forty nations, including Canada, India, and Singapore, have committed to opening up their electronic data, everything from weather records and crime statistics to transport data. The excitement about open data has largely revolved around the potential to empower citizens and improve the delivery of public services, ranging from urban transportation to personalized health care. We estimate that select applications of open data could help unlock more than $3 trillion in economic value every year—an amount equal to 4 percent of global GDP.29

Kenya became the first sub-Saharan African nation to launch an open data initiative in 2011, with the hope that making government procurement data more transparent would enable the country to save up to $1 billion a year. “We are moving to e-procurement, so now . . . our pen will cost 20 shillings, not 200, and times to process payments will be faster,” said Bitange Ndemo, permanent secretary of Kenya’s Information and Communications Ministry. “But it isn’t just about removing the manual aspects. The much more powerful thing, open data, is making the public aware.”30 Pune, India, uses data analytics to identify accident-prone locations and isolate common factors in accidents (such as the lack of crosswalks or too-short traffic-light cycles) in order to improve the city’s traffic infrastructure.31 The OpenStreetMap project, set up after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, combined data from different sources and became a critical source of reliable information for government and private aid agencies in delivering supplies to hospitals, triage centers, and refugee camps.32

ACCELERATING ADOPTION

It’s not simply that computers run more quickly today. So do consumers. One of the most striking aspects of the new age of accelerated technological change is the sharply increased pace of adoption. Historically, new technologies encountered a certain amount of friction on their way to world domination. It took a while for people to become comfortable with using new gadgets, for manufacturing to scale up, for distribution channels to develop, and for other businesses to create more compelling reasons for people to purchase the devices.

After Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone, more than fifty years elapsed before half of American homes had one. It took radio thirty-eight years to attract fifty million listeners. Adoption curves are much steeper in the twenty-first century.33 Half of all Americans acquired a smart phone within five years of the devices’ introduction. After reaching six million users in its first year, Facebook multiplied that number by one hundred times in its next five years of existence.34 In less than two years, WeChat, the mobile text and voice messaging communication service developed by China’s Tencent, has reached three hundred million users—more than the entire adult population of the United States.35 Accelerated adoption invites accelerated innovation. In 2009, two years after the iPhone’s launch, developers had created around 150,000 applications.36 By 2014, that number hit 1.2 million, and users had downloaded more than 75 billion total apps, over 10 for every person on the planet.37 As a distribution system for digital goods, the Internet is friction free. The only obstacles to scale are consumer interest and curiosity.

The types of rapid adoption curves seen in the digital sector also characterize physical goods and their manufacturing process. A new generation of industrial robots with enhanced perception, dexterity, and intelligence is being developed thanks to advances in machine vision and communication, sensors, and artificial intelligence. Sales of industrial robots grew by 170 percent in just two years between 2009 and 2011, and the industry’s annual revenues are expected to exceed $40 billion by 2020.38

The pace of this change will continue to accelerate. The more people online, the more people connected, the more rapidly innovations can spread. About 2.5 billion people were online around the world in 2013, and nearly 4 billion people are expected to be online by 2018.39 If current trends in innovation and adoption continue—and there is every reason to think that they will, as technology becomes ever more affordable and products can easily go global—it will not be uncommon for new offerings to be used by hundreds of millions of people in less than a year. This is a true disruption to the status quo.

SOURCE: The Social Economic Report, McKinsey Global Institute

The benefits from the application of data, digitization, and disruptive technologies discussed in this chapter are tremendous—think of the ease and speed with which you can experiment with new business models and the value you can extract from the data you already collect. Or the drastically reduced marginal costs of scaling up the production and distribution of goods and services. Or of how quickly you can now reach customers around the world, thanks to a proliferation in the number of platforms, distribution channels, and payment systems that abet them. Or even of the insights you can glean from your data to improve design, pricing, and marketing of your products—as well as all aspects of your operations.

But monetizing the value of these technologies isn’t always easy. MGI research indicates that the consumer is king in our technological age. As much as two-thirds of the value created by new Internet offerings is captured as consumer surplus—in the form of lower prices, improvements in productivity, or greater choices and convenience.40 The disruptive technologies discussed earlier will likely deliver the lion’s share of their value to consumers, even while providing companies with sufficient profit to encourage adoption and production. To illustrate the scale of the opportunity, consider this change: on July 31, 2013, the US Bureau of Economic Analysis released GDP figures that for the first time categorized research and development and software into a new category of “intellectual property products.” We estimate that digital capital is now the source of roughly one-third of total global GDP growth, with intangible assets (think of the value of Google’s search algorithm or Amazon’s recommendation engine) being the main driver.41

For businesses and governments alike, failing to navigate today’s technological tide will mean losing out on a huge economic opportunity as well as increasing vulnerability to potential disruptions. Digitization and technological advances can transform industries in the blink of an eye, as BlackBerry has learned. History is littered with such corporate casualties. The breathless wait for an updated smart phone may be a delicious pleasure for consumers. For businesses, however, anticipating and preparing for the next wave of the technological tsunami can be the difference between success and failure. Early birds will be challenged to place technology bets amid the extraordinary diversity of new technologies. For instance, within the realm of additive manufacturing—just one of the dozen disruptions we identify—a wide range of technologies and materials exists. They include laser sintering with powdered metal, fused deposition molding with melted plastic, and 3-D printers, which range in size and cost from $1,000 hobby printers to industrial-scale printers costing hundreds of thousands of dollars. Even if you are not an early bird in their application, you will need to determine when, how, and whether to take advantage of them—and be prepared to follow fast.

Lastly, understanding technology is now a core skill required of every business leader. You don’t need to know how to use the programming language SQL or be able to run a 3-D printer, though. Far more important is the ability to zero in on what your most tech-savvy customers are doing. Leaders must build and manage systematic ways of keeping the skills of employees up-to-date and must ensure that executive teams and boards remain well informed about the latest technological developments. Long-established strategic planning processes will also need to be reimagined—to include reliable monitoring of trends, to plan for a range of scenarios, and to jettison old assumptions about potential sources of competition and risk.

ADAPTING TO TECHNOLOGICAL DISRUPTION

On the first day of classes at Ivy League colleges, it was common for the dean to warn students: “Look to the left, look to the right. One of you won’t be here next year.”42 A similar dynamic is unfolding in the top echelons of the corporate world. In 1950, the average S&P 500 company could expect to stay on the index for more than sixty years.43 In 2011, that average was down to eighteen years, and the trend shows no sign of easing. At the current rate of churn, thanks to mergers and acquisitions, the rapid rise of upstart companies, and frequent falls of incumbent firms, 75 percent of the S&P 500 will be replaced by 2027.44 Companies are increasingly finding that their era of dominance is more like the career of a professional athlete than the tenure of a distinguished college professor—it lasts a few years rather than a few decades.45

While there is no technology silver bullet that is effective across different sectors, functions, and markets, we find that business leaders who adhere to five principles stand the best chance of staying on top and reinventing themselves to keep up with the “new normal.”

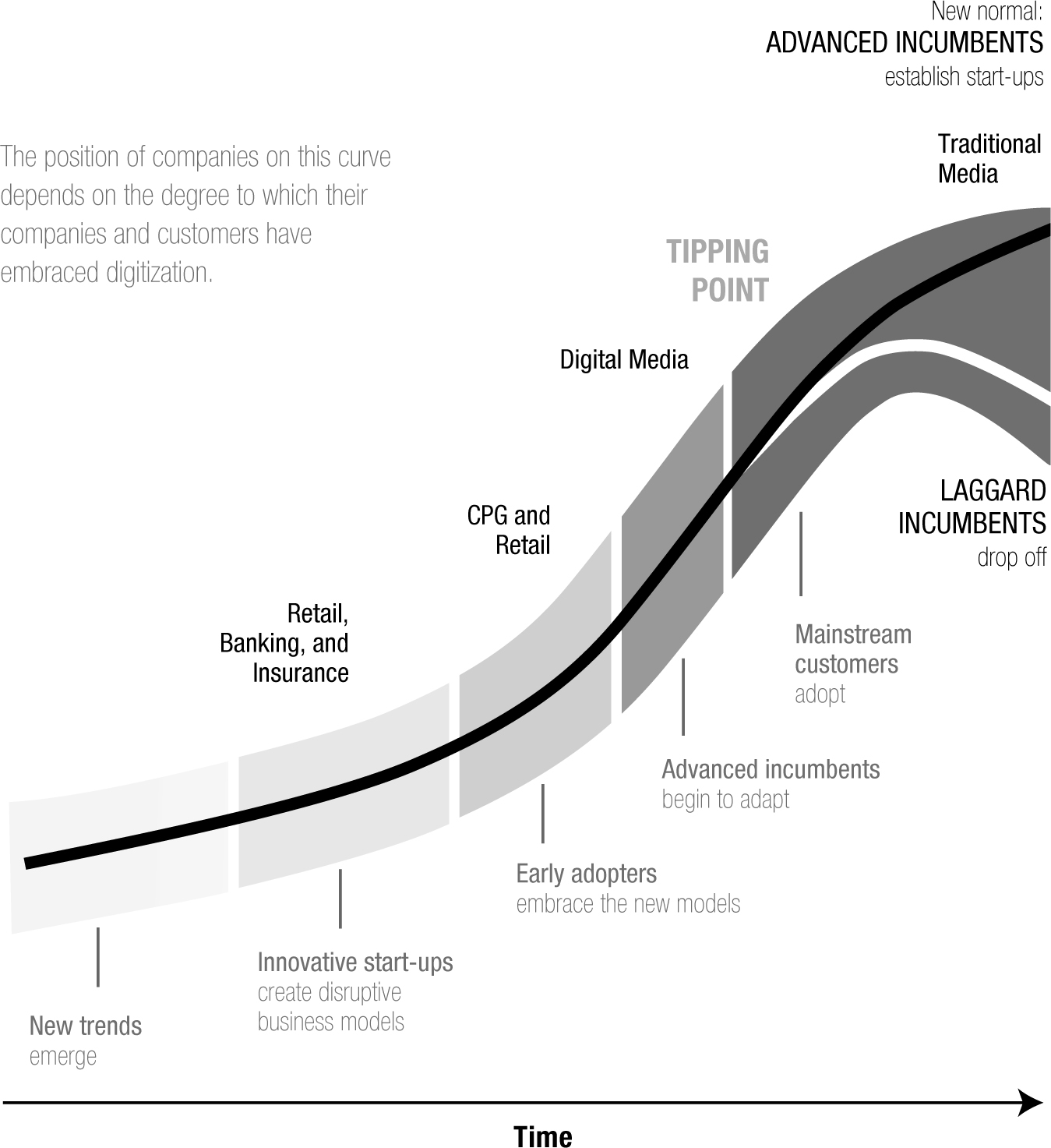

How digitization transforms industries

Make the Most of Your Digital Capital

Many companies are starting to awaken to the important role their currently unstructured data can play in sharpening existing processes and future business strategies. Everywhere we look, companies are putting data to use—driving market share, reducing costs, raising productivity, and improving products and services. Retailers are using big data to optimize prices dynamically, forecast demand, generate recommendations, and improve stock management. Manufacturers are using big data to create bespoke products that better serve customer needs and to optimize their supply chains. At Alibaba, China’s largest online merchant, the live data room resembles NASA mission control. Data-as-service start-ups are booming, and giants such as IBM, Microsoft, Oracle, and SAP have spent billions of dollars in the past several years snapping up companies that develop software for advanced data analytics.

In fact, intangible digital assets—such as behavioral data on consumers and tracking data from logistics—can be the seeds of entirely new products and services. The disruption in taxi services is one example. Uber uses algorithms to determine “surge” prices in times of peak demand.46 Lyft, another on-demand ride-sharing start-up, employs a “happy hour” pricing model to lower rates in times of soft demand.47 Health care is another example of a sector where the marriage of data, analytical models, and decision-support tools—all key components of digital capital—can create immense economic value, improve customer experience, and create difficult-to-replicate capabilities. Some five million Americans suffer from congestive heart failure, which is treatable with drug therapy or implantable devices.48 Medtronic has built an industry first, CareLink Express Service, a remote heart-monitoring network that connects implanted cardiac monitoring devices to sites where physicians can remotely view and interpret data, improving the quality and efficiency of patient care in the process. During the pilot phase of the program, patient wait times fell sharply, to less than fifteen minutes.49 “This kind of data is the currency of the future,” notes Ken Riff, vice president of strategy and patient data management at Medtronic.50

Look to Exploit Lower Marginal Costs of Digital

Digitization significantly reduces the costs associated with the access, discovery, and distribution of goods and services. More efficient distribution and lower barriers to entry have spurred more individuals, entrepreneurs, and businesses to participate in the digital marketplace and experiment with new business models. Digitization has drastically lowered geographic barriers as well, fueling the growth of micro-multinationals, microwork, and micro supply-chain companies.

Kiva, the world’s largest online platform for peer-to-peer microlending, has facilitated loans worth more than $630 million, mostly in the emerging world.51 Kickstarter, a crowd-funding platform that connects entrepreneurs to individuals interested in funding creative projects, has facilitated pledges of more than $1.4 billion to fund 70,000 creative projects since 2009.52 Small or individual registered investment advisors are the fastest-growing segment of the investment advisory business in the United States; they purchase turnkey back-end systems from companies like Fidelity and Charles Schwab to get all the capabilities they need in order to provide direct advice to consumers.53

In markets such as search, e-commerce, social media, and the sharing economy, the low marginal costs of digital infrastructure allow upstarts to build business models with near-limitless scale. WhatsApp, the mobile messaging platform that Facebook recently snapped up for $19 billion, reached 500 million monthly active users within five years of its launch.54 Snapchat surpassed the photo-sharing activity on both Facebook and Instagram with 400 million users only two years after its foundation.55 Sharing economy start-ups are growing at breathtaking speed. In 2013, some 450,000 active users were launching the Uber app every week, and more than a million Lyft users had requested a ride with the tap of a button.56

Traditional players have also benefited from changes in marginal cost economics to enter new markets, grow rapidly, or optimize processes and cost structures. French telecom operator Free Mobile reinvented the “mobile attacker model” by exploiting a large and active digital community of brand fans and advocates as its core asset. Free Mobile signed up more than 2.6 million new subscribers in less than three months in 2012 and captured 13 percent market share in one year with no above-the-line budget.57 Luxury retailer Burberry is synonymous with best-in-class multichannel customer experience; its flagship store at 121 Regent Street in London boasts the world’s tallest retail screen, real-life digital feeds, and RFID chips that are sewn into Burberry products. These tiny chips trigger bespoke content in front of RFID-enabled mirrors.58 Nordstrom, the luxury department store, first exploited the marginal cost advantages of digital for internal purposes, to develop shipping and inventory-management facilities. The company then turned its digital investments outward, building a strong e-commerce site, mobile-shopping apps, kiosks, and capabilities for managing customer relationships across channels.

Find New Ways to Monetize Consumer Surplus

There’s an interesting and perhaps counterintuitive implication to the rise of big data and increasingly cheap digital business tools. In theory, both trends should be immense boons to the companies that can afford to gather, maintain, and use data to their advantage. Consumers, however, remain king and queen in our age of accelerating technological change. Consumers capture as much as two-thirds of the value created by new Internet offerings in what is known as consumer surplus—lower costs, better products, and improved quality of life.59 The challenge for companies is how to get consumers to pay for all of the great new stuff—video, content, games, storage, messaging, convenience—being made available to them.

So far, only a few monetization models have proven effective at shifting value back to companies. One is advertising revenue, which has fueled the highly profitable growth of tech giants such as Facebook and Google. The advertising revenue model will remain viable, but users’ expectations surrounding the ability to target, measure, and analyze ads effectively will continue to rise.

Direct payments and subscriptions reflect an increasing ability to charge for online content. Under this model, the use of “freemium” pricing strategies—offering no-fee basic services and charging for enhanced features such as the ability to avoid advertising, virtual goods in games, or a higher level of service and access to valuable features—is increasingly common. Examples range from Zynga and Spotify to LinkedIn and Apple. Joining LinkedIn is free, for example. Upgrading to premium membership—monthly prices start at $59.99 per month for the Business Plus account—affords the user greater insight into who has been looking at his or her profile, the ability to send more messages to potential leads, and the use of more advanced search filters.60

A third model is monetization of big data, either through innovative business-to-business offerings (for example, crowd-sourcing business intelligence or outsourced data science services) or through developing more relevant products, services, or content for which consumers are willing to pay. LinkedIn, for example, makes 20 percent of its revenue from subscriptions, 30 percent from marketing, and 50 percent from talent solutions, a core part of which is selling targeted talent intelligence and tools to recruiters.61

You will have to keep experimenting in order to capture more consumer surplus for your business. Turning traditional transaction-based e-commerce into subscription models is one increasingly popular way. In an effort to lock in consumer loyalty and repeat business, a host of companies have created offerings that put the relationship on autopilot. In retail, for instance, Glossybox, based in Berlin, Germany, has already shipped over four million boxes of new beauty products to Internet subscribers, many of whom pay a $21 monthly fee for five surprise luxury items.62 Companies like Dollar Shaving Club and Harry’s, which ship razor blades and cartridges to customers each month for a fixed price, are challenging longstanding incumbents like Gillette. Graze, a UK-based subscription service for weekly personalized healthy snack boxes, nearly doubled its revenues in 2013, to £40.2 million ($64.1 million).63 In media, experimentation with digital content monetization models is commonplace. Creating digital paid subscriptions as well as bundling digital and print subscriptions has helped the New York Times mitigate declines in advertising and print circulation. CEO Mark Thompson has dubbed the adoption of an aggressive paywall “the most important and successful business decision in years.” The Times boasts more than 875,000 digital subscribers, and circulation revenues now surpass advertising revenues.64 Piano Media, a start-up in Slovakia, created a paywall system that encompassed most leading media in that country. In its original revenue model, the company split subscription revenue with the original site through which the user joined (30 percent) and other media sites based on the time users spent on each site. Piano drove subscriptions and proved the concept in a five-million-strong, linguistically closed market, before moving onto other Central European markets in 2012.65 In August 2014, Piano extended its reach by acquiring Press+, a US-based pioneer of micropayments and paywalls that is nearly nine times Piano’s size in revenues.66

Don’t Wait for the Dust to Settle

The instinct, in the face of rapid technological churn, can be to wait for the dust to settle before placing your bets on a new technology. But time is the enemy. Today’s technology could be outdated tomorrow, and a seemingly irrelevant acquisition or strategic move may wind up shaking up the industry. Figuring out which of the dozen types of 3-D printing technologies will become standard is a time-consuming effort with a low likelihood of success. Most companies struggle to make such efforts an integral part of their business-as-usual processes.

For many established companies, placing big bets on early technologies is simply not an option due to strictly defined risk appetite, high hurdles for new investments, and legacy IT systems. In the auto insurance industry, for instance, many established players continue to limit investments in telematics and behavioral data to small-scale pilot programs, while they nervously watch new nimble attackers enter the space. Embracing innovation could potentially redefine the way companies monitor customers’ actions—and hence set prices and assess risk. Companies in the beauty business have also been caught off guard by technology. Mink, a 3-D printer that allows customers to “print” customized makeup from the comfort of home, threatens to challenge the healthy margin of incumbents once it launches at its target retail price of $200 in 2015.67

Tech giants have stood out as an unsurprising exception to the rule, using their deep pockets and eagle eyes for the latest innovations to place large bets on the next transformative technologies. Google acquired Android in 2005 when the mobile Internet was in its infancy.68 The following year, when online video advertising was in its infancy, it paid $1.6 billion for YouTube.69 Both proved to be masterstrokes, defying the prevailing conventional wisdom. Google cofounder Larry Page gives a sense of the nervousness that thinking in advance of the crowd can engender. Talking about the decision to buy Android, he said, “I felt sort of bad and sort of guilty. Why am I spending time on this? Why aren’t I spending time on, you know, search or advertising or something that was more core to our business? But it turned out to be a pretty important thing to do.”70

Large companies in other sectors have realized that establishing symbiotic relationships with vibrant tech start-ups can be an increasingly effective way to place technology bets. Doing so minimizes risk and disruption to the core business, while potentially providing companies with the option to take ownership of or deploy promising new products and services. Companies do so by embedding accelerators and innovation labs, which provide supportive environments, mentoring, equipment, and funding to promising entrepreneurs, in their existing structures.71 In 2012, General Electric launched GE Garages, a lab incubator concept focused on reinspiring innovation in advanced manufacturing. GE Garages sets up workshops in the United States to provide start-ups with access to equipment, such as 3-D printers, computerized numerical control machines, and laser cutters, and to give them access to expert advice and potential partners. In 2014, GE took the concept global; the most recent GE Garage established is in Lagos, Nigeria.72 In 2013, Allianz launched its first Digital Accelerator, cosponsored by Google, which focuses on how big data can help drive the development of new insurance and finance business models, in Munich.73

Think Technology for Your Talent, Organization, and Investments

Some companies have successfully institutionalized the technology mind-set by appointing a chief digital officer and elevating the role throughout the organization. In 2008, Sona Chawla joined Walgreens, the large US pharmacy and retail chain, from Dell as senior vice president of e-commerce. A couple years later, she was promoted to president of e-commerce, and in 2013 she became the president of digital and chief marketing officer, reporting directly to the CEO.74 Under Chawla, Walgreens acquired drugstore.com in 2011 and developed one of the most popular US mobile health apps, which allows customers to refill prescriptions by scanning bar codes and set personal medication reminders.75 Today, more than 40 percent of the chain’s online refill requests come from the app, and multichannel customers spend 3.5 times more than brick-and-mortar customers.76

Other companies have used the “acqui-hire” approach—buying a startup in order to acquire the team that runs it—or established partnerships to catch up on promising trends and accelerate access to intellectual property, talent, and technology. Yahoo laid out $1 billion for Tumblr in part to bring wunderkind founder David Karp into the fold.77 In May 2014, Walmart acquired Silicon Valley–based ad software company Adchemy for $300 million and incorporated Adchemy’s sixty-person team into @Walmart Labs, the company’s in-house tech shop.78 In 2013, Sephora, the cosmetics retailer with 1,300 stores in twenty-seven countries, acquired Scentsa, a specialist in digital technologies, to improve the in-store shopping experience and keep Scentsa’s technology out of the reach of competitors. 79

German media conglomerate Axel Springer has embraced technology and digitization in its investment approach. In 2014, it sold off its regional newspapers along with its women’s and TV magazines, then invested heavily in three digital pillars: paid content, digital advertising, and online classifieds.80 It also launched the Berlin-based Axel Springer Plug and Play Accelerator. In 2013, the company started a joint venture with private equity firm General Atlantic, dedicated to digital classifieds.81 An in-house VC outfit, Axel Springer Ventures, has investments in start-ups, such as price comparison sites and loyalty shopping apps, and in a leading early stage investment fund.82

![]()

There’s no guarantee that any of these efforts will enable companies to thrive in an age of rapid technological advance. But in a world in which business models and strategies grow old quickly, leaders must constantly think about ways to rejuvenate their enterprises.