![]()

GETTING OLD ISN’T WHAT IT USED TO BE

Responding to the Challenges of an Aging World

IT’S NOT UNCOMMON FOR A ROBOT TO VACUUM THE FLOOR. IN Japan, robots are quickly evolving to perform the functions of butlers, home health-care aides, and companions. Combining robotic hardware known as WAM (whole arm manipulator), arms with computer intelligence, researchers at Japan’s Nara Institute of Science and Technology and Barrett Technology have invented robotic arms that can help people in and out of their jackets, shirts, and pajamas. Robovie-R3, a humanoid bot designed by ART and Vstone, based in Osaka, is like the Star Wars character R2-D2 come to life. Robovie-R3 shuffles alongside mall shoppers at speeds up to 1.5 miles per hour, takes the hand of elderly users as they navigate through crowds, and totes shopping baskets—all without demanding to stop for coffee.1

It’s not uncommon for first-time visitors to Tokyo to remark that the metropolis looks like the future. In Japanese factories, like the highly efficient plant in Toyota City that produces the Prius, robotic equipment has long substituted for human labor. But Robovie-R3 and other recent robotic products are designed to meet needs other than production for industry—specifically the real and current human need in what is now, with a median age of forty-six and 24 percent of the population over sixty-five, the oldest country in the world.2 Add low levels of immigration and anemic fertility rates (1.4 births per woman over the course of a lifetime), and there simply aren’t enough people to care for Japan’s growing elderly population.3 At a meeting with journalists, officials at Toyota City were asked how their country would cope with its demographic problem. The response—“Maybe the robots will take care of us”—was not encouraging.4

Global analysts are fond of painting a picture of a young world on the move, just waiting to grow up. In large chunks of the globe, that is indeed the reality. In Pakistan, where the median age is 22.6 years, nearly 55 percent of the population is under 25.5 In sub-Saharan Africa, more than 40 percent of the population is under the age of 15.6 Every major consumer and services company is figuring out how to tap into the rising number of young consumers.

But there’s a flip side to this coin, and it is one of the most overlooked trend breaks evident in the world today. In the years after World War II, the world seemed to get younger, and the population grew in virtually every country, rich and poor. Improvements in vaccinations, declining infant mortality, and the absence of massively destructive world wars created a virtuous circle. As the world’s population kept growing, the working-age cohort grew apace, fueling economic growth. This demographic surplus has paid enormous dividends. More people meant more demand for goods and services, more houses, and more schools, which in turn created more jobs and more tax revenues. With technology acting as an amplifier, these people all worked more productively.

Now, simply put, the world is getting older. We have been aware of this development for some time, but long-term forecasts are becoming reality. In many large and highly developed economies—and in the world’s largest developing economy, China—people are living longer and having fewer children. The baby-boom generation is getting older and easing into retirement, while fertility is falling sharply. These trends are reaching a tipping point. Sometime in the next few decades, they will very likely cause the population of most of the world—with the exception of Africa—to plateau for the first time in modern history.7 Large swaths of the world will have dramatically older populations, aging workforces, and ballooning government social programs. In this regard, Japan, whose population has already started to decline, really does look like the future.

These developments require a reset of our intuition to change the way we think about the elderly—as consumers, customers, employees, and stakeholders.

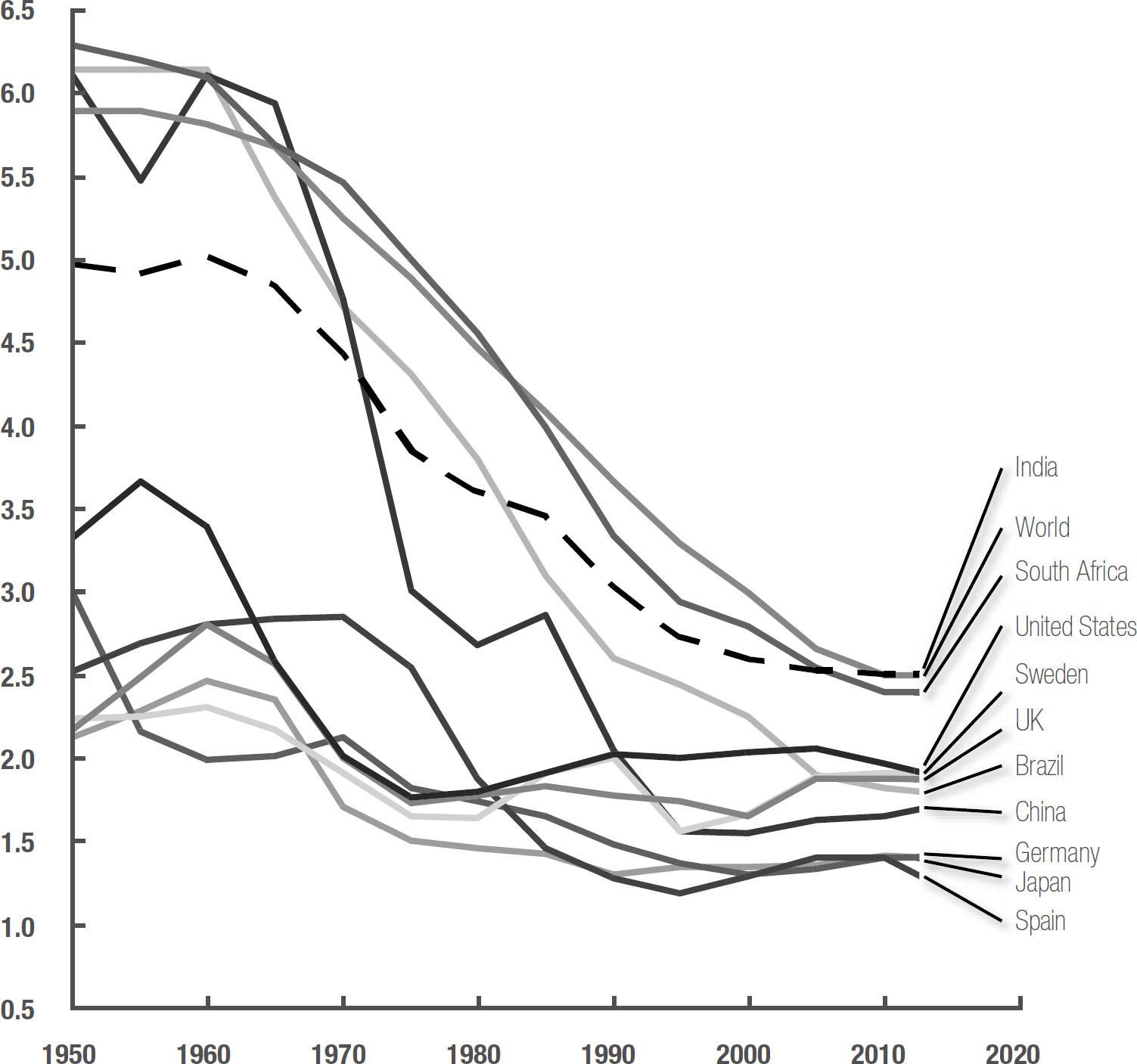

Fertility rates have declined globally

NOTE: Fertility rate is the average number of children a hypothetical cohort of women would have at the end of their reproductive period if they were subject during their whole lives to the fertility rates of a given period and if they were not subject to mortality. It is expressed as children per woman.

SOURCE: UN population data; McKinsey Global Institute analysis

FALLING FERTILITY

Global experience suggests that as nations grow wealthier, their populations become less fertile. As economies develop, residents are more likely to use birth control, women have more choices, parents are less likely to regard large families as an economic necessity, and families are less likely to view having a large number of children as a hedge against high infant mortality rates. Typically, the richer the country, the lower the number of children born over a woman’s lifetime. The total fertility rate (the average number of children that would be born per woman if all women lived to the end of their childbearing years) is 1.4 children per woman in Germany, for instance, while it is over 6 in countries like Niger, Somalia, and Mali.8 While recent research indicates that the fertility trend can reverse in a limited way in high-income countries, particularly those with high immigration—for example, the United Kingdom, which has a fertility rate of 1.96—and countries that implement policies to help families manage children and careers, the long-term trend toward lower fertility rates is unlikely to be disrupted.9

Thirty years ago, only a small share of the global population in just a few countries had fertility rates that were substantially below those needed to replace each generation—about 2.1 births per woman in developed countries and about 2.5 births per woman in developing countries.10 Fertility drove most population growth in developing countries, with 1970 rates as high as seven children per woman in Mexico and Saudi Arabia and five per woman in India, Brazil, and Indonesia.11 In many advanced economies with low fertility rates, immigration propelled population growth. Between the 1960s and 2012, the share of immigrant-born children in the total population quadrupled in the United Kingdom (from 3 to 12 percent), more than doubled in the United States (from 6 to 14 percent), and increased by half in Canada and France.12 By 2014, however, thanks to broadly rising prosperity, about 60 percent of the world’s population lived in countries with fertility rates below replacement rates.13 This includes most of the developed world as well as some large developing countries such as China (1.5), Brazil (1.8), Russia (1.6), and Vietnam (1.8).14 Net migration is also anticipated to decline in eighteen of the world’s nineteen largest economics (the exception is Mexico).15

The 2006 Alfonso Cuarón film Children of Men painted a vision of a dystopic future in which the birth of a child was a rarity, even a miracle. Things haven’t quite come to that, but in nearly every European country, the fertility rate is below the replacement rate. Across the European Union (EU), the population is expected to increase by 5 percent until 2040 and then start to shrink.16 In Germany (2014 fertility rate: 1.4), which has long stood out for its weak population growth, the European Commission believes the population could shrink by 19 percent by 2060.17 The country’s working-age population is expected to fall from fifty-four million in 2010 to thirty-six million in 2060.18

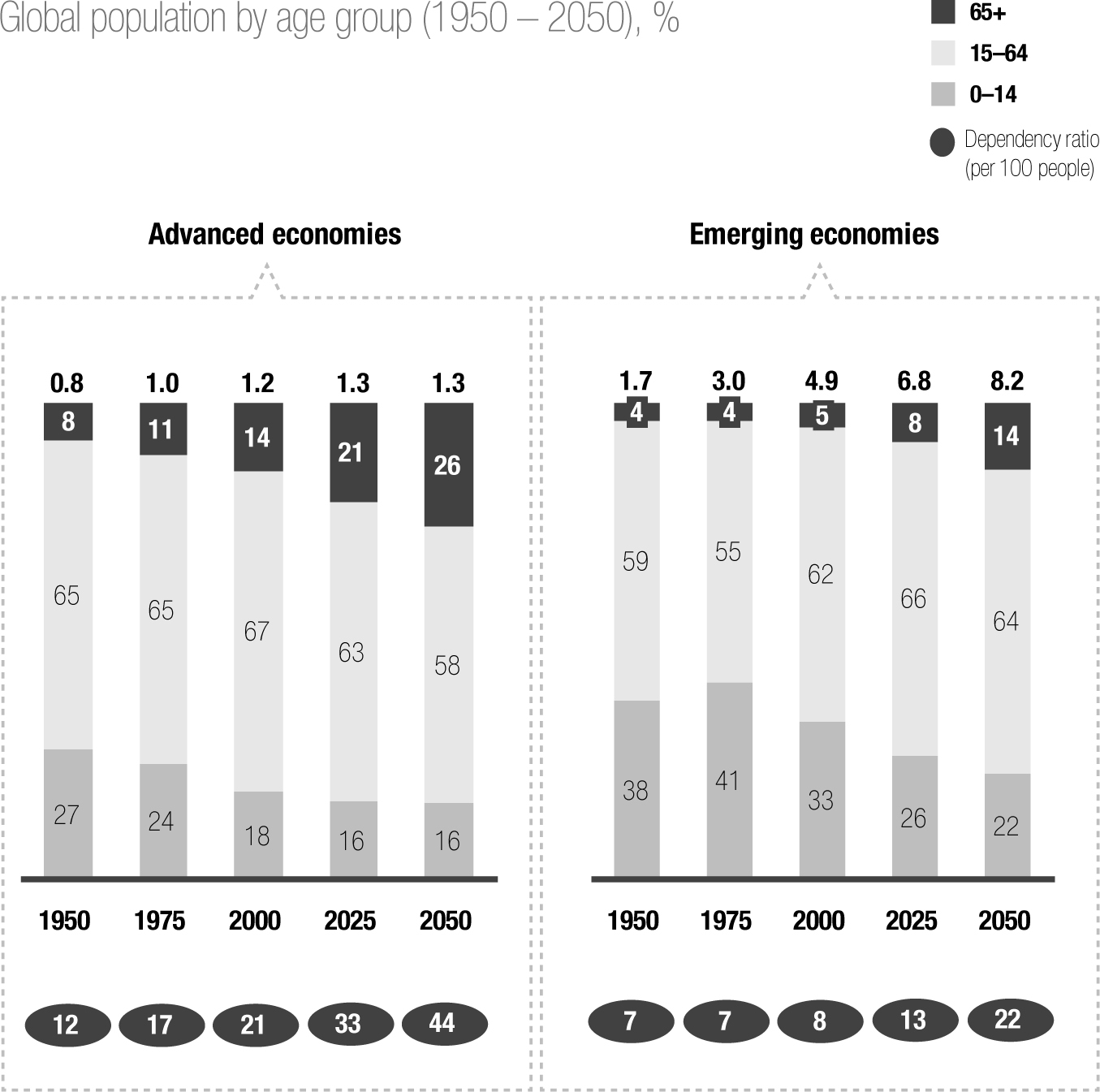

Proportion of elderly in global population is increasing rapidly

NOTE: Old age dependency ratio = Population aged 65+ over population 15-64

SOURCE: McKinsey Global Institute analysis, UN population data

Germany has been able to mask its decline by attracting immigrants from Russia, Turkey, Africa, and elsewhere. But not all countries possess the economic strength or cultural attributes necessary to attract new residents. Many European countries with low fertility rates are already suffering from massive brain drain, as young people leave to seek their fortunes elsewhere. Regions of Europe surrounding the Baltic and Black seas are already depopulating and could turn into ghost towns in the coming decades. The population of Bulgaria is expected to fall by 27 percent by 2060, and the populations of Latvia, Lithuania, and Romania could fall by similar amounts.19 The exception to this trend is the United Kingdom, which may overtake Germany as the EU’s most populous country by 2060—thanks to the high birth rate among families whose forebears were immigrants and to relatively high immigration today. This is not only a European phenomenon. The peak days of global population growth are potentially behind every continent except Africa. Annual population growth could drop from its rate of 1.43 percent between 1964 and 2012 to as low as 0.25 percent over the coming fifty years, a trend that will have profound impacts on the global economy and politics.20

AGING POPULATIONS

The outstanding and often unappreciated feature of the trend break era is the way in which forces act in concert to amplify and produce change at a more rapid scale. We’ve already seen this with urbanization and technological change. The same dynamic is apparent in demographics. At the same time that fertility rates are broadly declining, life expectancy is rising. Put another way, comparatively few new people are being created, while those created several decades ago are sticking around a lot longer. The rise of global life expectancy is one of the great feel-good stories of the postwar era. Around the world, life expectancy at birth rose from forty-seven years in 1950–1955 to sixty-nine today. A few decades from now, between 2045 and 2050, the average person alive can expect to live to an impressive seventy-six years.21

The demographic tables, simply put, have turned upside down. In 1950, developed countries had twice as many children (aged fifteen years and under) as older persons (aged sixty years and over). By 2013, older persons outnumbered children by a margin of 21 percent to 16 percent of the populations in such countries. Given current trends, by 2050 developed economies will have twice as many older persons as children.22 Moody’s, the credit-rating agency, in 2014 projected that the number of “superaged” countries—where more than one-fifth of the population is sixty-five or older—would rise from 3 today (Germany, Italy, and Japan) to 13 in 2020 and to 34 in 2030.23

This cycle won’t play out only in the developed world. China is currently the most populous nation in the world and a rising economic power. On a steaming spring day, throngs of newly minted graduates pose for photos in caps and gowns in scenic spots in Wuhan, an interior city that is home to dozens of higher educational institutions and boasts some 1.2 million students.24 But for quite different reasons, Wuhan and the rest of China are experiencing a demographic pinch similar to Europe’s. The median age in China is about thirty-seven, roughly the same as in the United States.25 The number of Chinese aged fifty-five or older is likely to rise to more than 43 percent of the population in 2030, from 26 percent today.26 The Chinese refer to their impending aging challenge as the “4:2:1 problem.” Every adult child today must care for two parents and four grandparents. By 2040, China could have more dementia patients than the rest of the developed world combined.27 The world’s workshop, peopled by armies of workers performing labor-intensive tasks, will in time become the world’s nursing home.

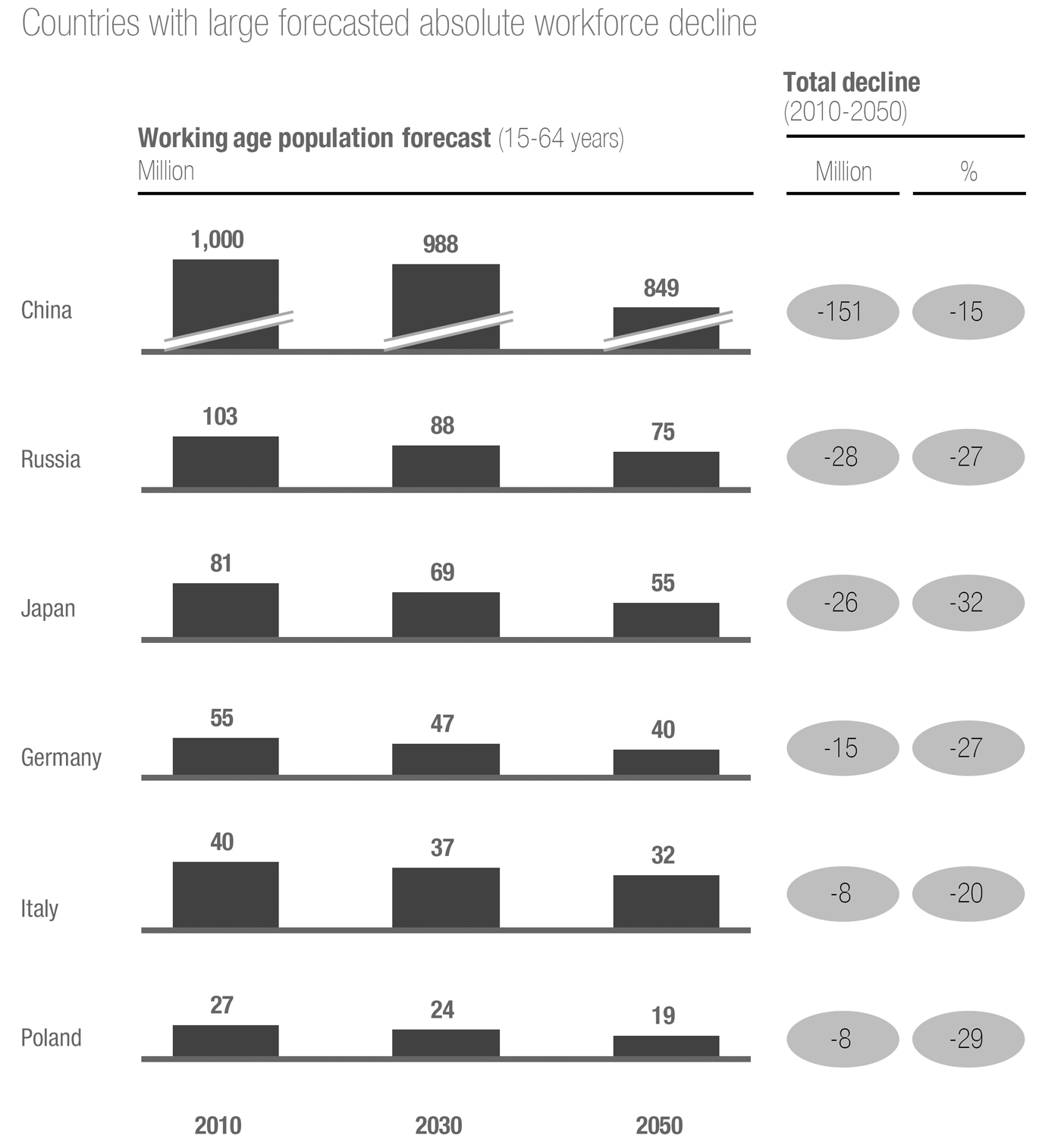

Without migration and policy changes, many countries will see their labor force shrink dramatically

SOURCE: UN Population Data; McKinsey Global Institute analysis

Beyond sheer demographics, technology is adding to the trend of aging. We expect to see significant increases in life expectancy over the next decade as new technologies help people live healthier and longer. For instance, next-generation genomics—the combination of sequencing technologies, big data analytics, and technologies that are able to modify organisms—has the potential to give humans far greater power over biology, helping to cure diseases such as cancer and cardiovascular disease that currently kill around twenty-six million people a year.28 Based on the assessment of cancer experts, we estimate that genomic-based diagnoses and treatments will extend patients’ lives by between six months and two years in 2025.29 Additionally, desktop machines could make gene sequencing part of every doctor’s diagnostic routine, and 3-D printing could soon let doctors “print” biological structures and organs. Finally, advances in materials science could lead to the development of nanomaterials for drug delivery.

GRAYING—AND SHRINKING—LABOR FORCE

Falling fertility, slowing population growth, and aging populations will all have a profound impact on the labor force of the future. New workers will enter at a slower rate. Older people may work for much longer than they do today. And the definition of the labor force itself may change from today’s twenty- to sixty-four-year-olds to include older age groups.

“May your heart always be joyful. And may your song always be sung. May you stay forever young.” So goes the lyric from Bob Dylan’s “Forever Young.” Difficult as it may be to believe, the raspy-voiced troubadour is seventy-three. He still tours. Mick Jagger, a great-grandfather who turned seventy in July 2014, struts around arena stages in leather pants. Baseball player Jamie Moyer pitched—and pitched well—until the age of forty-nine. US Supreme Court justices routinely stay on the job until their eighties; the median age of today’s court is sixty-four.30 In coming years, such phenomena are likely to be more common in lower-profile jobs.

Why? Based on current trends and definitions, the annual growth rate of the global labor force is set to weaken from around 1.4 percent annually between 1990 and 2010 to about 1 percent to 2030.31 In 1964, the working-age group (fifteen to sixty-four) accounted for 58 percent of the total population, reaching a peak of 68 percent in 2012.32 In the next fifty years, however, the working-age population is expected to drop to 61 percent, while the share of elderly (sixty-five and up) in the total population could increase to 23 percent, from 9 percent in 2012.33 In China, some 70 percent of the population works today, one of the highest such shares in the world. But in January 2013, China’s National Bureau of Statistics announced that the country’s working-age population actually fell in 2012. And as the country’s population ages, the proportion of Chinese who are working should fall to 67 percent by 2030. We estimate that developed economies will add about thirty million workers by 2030, only a 6 percent increase from 2010.34 Moody’s predicts that between 2015 and 2030, the world’s working-age demographic will grow at only half the rate it did between 2001 and 2015.35 Most of the growth will be in a handful of countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada.

Longer life expectancy and lower investment returns will mean that the elderly will be less able to afford to retire. And because unfavorable demographics—fewer people working, more people receiving benefits—can increase budget deficits, governments will come under increased pressure to boost retirement ages. So, worldwide, the share of older workers (above fifty-five years) in the workforce is expected to increase from 14 percent in 2010 to 22 percent by 2030. The graying of the workforce will be felt most acutely in advanced economies and in China, where the share of older workers will increase to 27 and 31 percent of the workforce, respectively.36

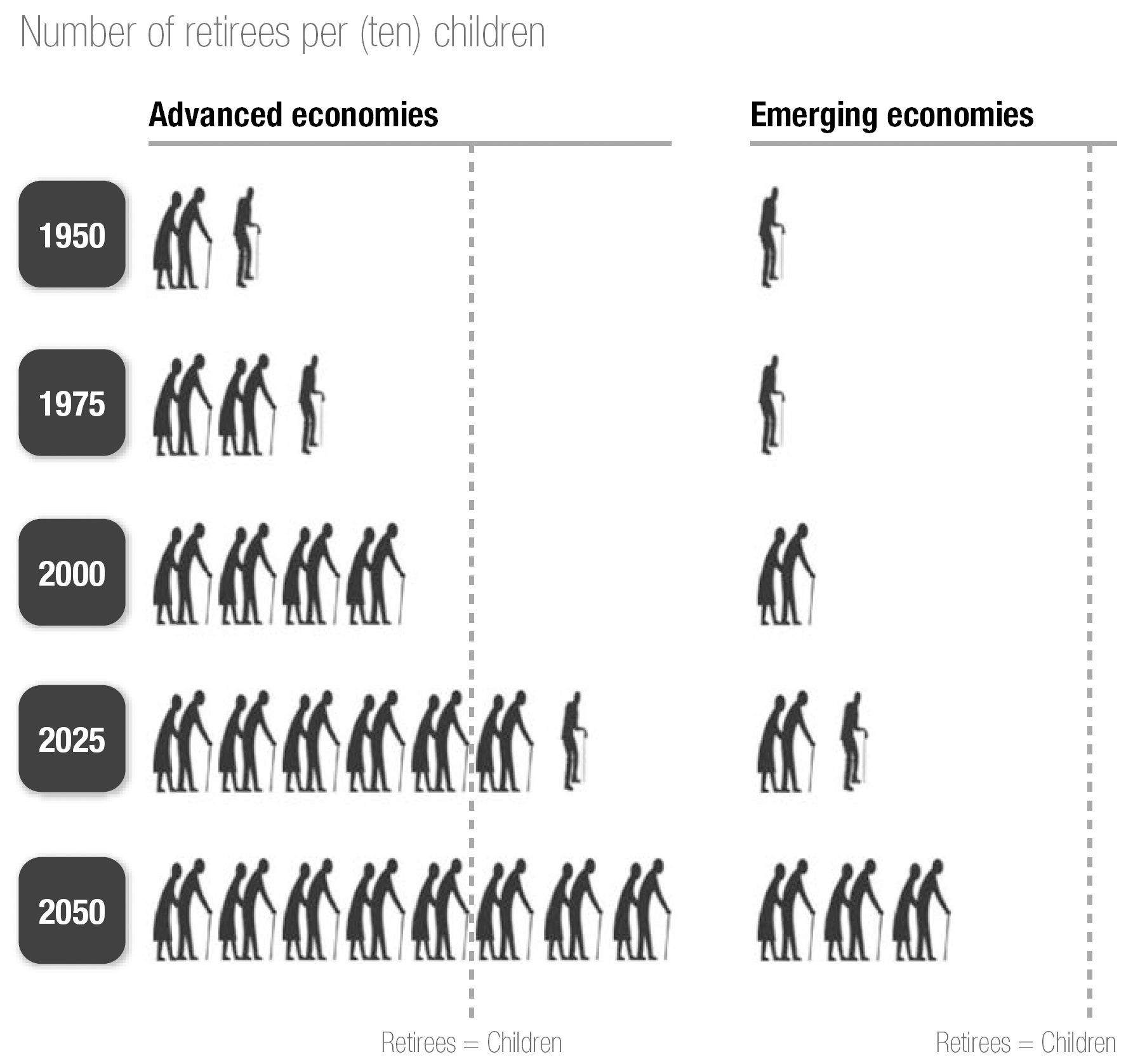

A STRUCTURAL CHANGE

While these demographic changes have long been predicted, countries are struggling to cope with them. Despite spending $265 billion a year on family subsidies, Germany still encounters difficulties changing cultural attitudes toward increased fertility.37 Research suggests that China’s fertility rate is unlikely to recover quickly, if at all.38 And for many countries, including the Nordic nations, Japan, and Russia, immigration—often an effective means of changing a nation’s demographic profile—is culturally and socially problematic. The aging and shrinking of the workforce is unprecedented in modern history, and the disruption will affect us all. The number of likely retirees will grow more than twice as fast as the labor pool, leaving fewer workers to pay for the elderly.39 Over the next two decades, the total population of retirees is expected to reach 360 million.40 Roughly 40 percent of expected retirees will be in advanced economies and China. And of those retirees, roughly 38 million will be college-educated workers with valuable skills.41

In addition to creating pressure on global pension funds, these trends will pressure the world’s pool of savings and create a host of new fiscal stresses.42 A 2013 Standard & Poor’s report found that without policy changes, age-related spending will accelerate the growth of median net general government debt in advanced economies from less than 40 percent today to 190 percent in 2050.43 The conflicts in US states and cities over underfunded pensions, such as the scenario currently playing out in Illinois, are simply the opening skirmishes of a much larger battle.

Governments in economies with established social security and pensions systems are clearly becoming increasingly alarmed about the cost. OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) research shows that the average pension age in thirty advanced economies fell from 64.3 years in the early 1950s to a low of 62.5 years in the early 1990s for men, a drop of nearly two years.44 For women, the average age fell from 62.9 to 61.0 in the same time period. That trend has broken. Since the mid-1990s, fourteen countries have increased or plan to increase pension ages for men, and eighteen have done so or plan to do so for women. Over the next forty years, almost half of OECD countries are set to increase the pension age. But, as the OECD noted, this is just “running to stand still,” because life expectancy is rising. The United Kingdom’s Turner commission on pension reform has suggested that the state pension age should be increased to seventy years.45

Faced with the lengthening retirement periods of their former employees, the private sector is increasingly moving away from defined-benefit pension plans. Starting in the 1980s and accelerating in the 2000s, advanced economies have seen a shift toward defined-contribution plans.* Between 1980 and 2008, the proportion of US private-sector payroll workers enrolled in defined-benefit pension plans fell from 32 percent to 20 percent; the proportion plummeted to 16 percent in 2013. Meanwhile, the proportion of workers in contribution-only plans grew from 8 percent in 1980 to 42 percent in 2013.46 Many employers have frozen their defined-benefit pension plans, and most others are expected to freeze and terminate theirs altogether in coming years.47

Between 1950 – 2050, the ratio of retirees to children will have increased

NOTE: Retirees to children ratio = Population aged 65+ over population <15

SOURCE: UN population data; McKinsey Global Institute analysis

Attitudes about retirement are also beginning to shift in reaction to the financial pressures that many older people anticipate. In the United States, a poll of Americans aged fifty or older showed that nearly one-third thought it was highly likely that they would do some paid work during retirement, and another 28 percent thought it somewhat likely. Yet one in five reported that they had already faced age discrimination in the workplace—before retirement age—and many of those who had looked for work after retirement had found it difficult.48

ADAPTING TO THE AGING TREND

As a leader in your business, you can’t afford to stand still and watch as employees and customers age. Adapting to the new reality will require some fundamental changes in the way most businesses operate and how they manage customers, employees, and stakeholders over their life spans. The health-care industry is at the forefront of these demographic changes. For companies like Hospital Corporation of America, aging is a double-edged sword. Rising numbers of people covered by Medicare and of Americans suffering from health issues common to old age will drive demand for services at its 165 hospitals and 113 freestanding surgery centers. But the same trend will push rising numbers of its experienced professionals out of the workplace, at least as it is currently structured. When a nurse practitioner retires, she may take thirty-five years of accumulated experience with her—knowledge that can be crucial in an emergency. Hospital Corporation of America has come to realize that it can use flexible work arrangements as an important means of keeping older workers engaged for longer periods. So a nurse might shift from full-time work to take a few shifts when needed, continuing to earn income while avoiding the stress and long hours that accompany full-time posts.49

Coping with a Graying Employee Pool

Employers have long focused on youth. In Silicon Valley, executives in their late twenties are often made to feel past their prime. Older workers can be more expensive, so they are often the first to be bought out or let go during restructurings. But in a graying world, employers have to reset their intuition. Rather than seeing older employees as legacy costs, they must view them as assets and resources. Employers want to be fishing in the deepest and most populated parts of the talent pool. As demographics shift, there will be more skilled, educated, talented, and experienced people congregating in the deeper waters.

Historically, the mentality of both employers and the employed has been black and white. Workers are on staff, full-time, and in the office every day until they no longer work for the company. Employers have grown accustomed to dictating the terms and conditions of employment, while unions have become accustomed to negotiating on behalf of full-time employees. However, technology, virtual ways of working, and shifting demographics may change this paradigm. In order to engage workers who are older, and for whom the attraction of a full-time job may be decreasing over time, companies have to become more comfortable dealing with shades of gray. A range of arrangements can help keep employees and companies tethered to one another, but on terms that may be more appealing to older employees.

In Japan, companies like Toyota, which used to maintain strict age-based retirement programs, have implemented reemployment programs that enable retiring workers to apply for positions at Toyota or its affiliated companies. Toyota rehires about half of its retiring employees through the program, allowing the company to retain their skills and experience as it maintains flexibility of production. In return, the retiring employees gain a stream of income, social interaction, and the opportunity to continue plying their trade on a part-time basis.50

Such policies are becoming increasingly important in designing career paths that fit senior skills and constraints. In France, Axa launched its Cap Métiers program, aiming to promote internal job mobility for its staff and particularly targeting older workers. Axa offered non-front-line staffers a job guarantee and vocational training if they decide to change their roles; 30 percent of its staff, including a large proportion of senior workers, switched jobs during the initial years of the program. The electronic systems group Thales, determined to raise the number of employees over fifty-five by 5 percent annually, implemented an integrated policy to anticipate career evolution—for example, through a systematic career review for those aged over forty-five—developing vocational training and mentorship and managing the transition between work and retirement.51

Another crucial initiative is to offer specific training to help retain older workers, redefine their roles, and keep their skills updated. British Gas, a leading UK energy supplier, removed age limits on its training and apprenticeships programs. The average age of apprentices and trainees has risen, with some trainees as old as fifty-seven. The company also actively encourages senior employees to act as mentors to younger workers and deploys flexible practices to support older workers and caregivers.52

Fearing labor shortages as baby boomers age, some companies in the United States have adjusted human resources needs to the well-established migratory patterns of older Americans, from the Northeast, Midwest, and Plains to Florida and the Southwest in the winter. CVS, the drugstore giant, realized that if it “doesn’t learn how to recruit and retain older people,” it wouldn’t “have a business,” Steve Wing, the company’s director of workforce initiatives, said. So CVS rolled out its Snowbird Program, under which pharmacists, photo supervisors, and cosmetics salespeople in New England can work at stores in Florida during the winter. The program has greatly improved satisfaction for the more than a thousand employees who have been participating each year. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that retention rates of the mature workers were 30 percent higher than the industry average.53

Marketing to an Aging Demographic

Consumer-facing companies today are obsessed with their performance in “the demo”—the twenty-five-to-fifty-four demographic. Strategists construct elaborate plans to grab customers when they are young and forming preferences, hold on to them as they mature and pass through their peak earnings and consumption years, and then let them go as soon as they hit their fifties. But in the evolving world, older consumers will make up a larger portion of the market and will be active consumers for a longer time. If more older people are likely to be working longer, they are more likely to have more disposable income. As these customers’ preferences and needs change over time, companies have to reset their intuition so that they can meet older consumers on their own terms.

For example, people facing a difficult transition to retirement tend to become more cost conscious. In France, for example, the gap between the annual purchasing power of households aged 50 to 54 and those aged 70 to 74 is on average €18,000. By 2030, this gap is expected to increase to €22,000.54 Elderly consumers face trade-offs that force a change in purchasing tactics. While nonretirees are more inclined to “shop smarter,” looking for bargains on brand-name products online, retirees prefer to seek value, by, for example, buying supermarkets’ private-label goods.55

There is a second important trend in consuming patterns. Seniors typically reduce their spending on housing, food away from home, and apparel as they move to retirement, while they increase spending on food at home, medical services, and, surprisingly, electronics. Of particular importance is their focus on health and wellness, addressing the need to remain mobile and independent. Products and services that address these needs will have a fast-growing market to capture. Danone, for example, recently launched Densia—which strengthens bone density—in Spain, and it plans to expand to other European markets, such as France.56

As new generations enter this fast-growing segment, it will be important to keep attuned to their needs and not blindly rely on the approaches used in earlier eras. This is especially true for rapidly growing countries like China. Given current demographic trends, China will add 125 million elderly consumers between today and 2020. Their spending patterns will likely differ from those of the current retired generation, which lived through the Cultural Revolution and allocates little to discretionary categories—only 7 percent toward apparel, for example. In fact, our latest Chinese consumer survey shows the spending patterns of today’s 45- to 54-year-olds—who will be the older generation in 2020—are more similar to those of 34- to 45-year-olds, with a greater emphasis on discretionary spending, for example. Companies will need to rethink what older Chinese consumers want.57

The breakdown of traditional family structures will strongly impact the elderly, who will pursue community and digital connectivity. Online platforms and other business innovations could address isolation, a factor particularly relevant to elderly people who live alone. Tapping the desire for a sense of community, ElderTreks offers holiday travel to seniors.58 Thomas Cook (India) launched Silver Breaks tourism packages targeting affluent Indian travelers over sixty years of age with features such as easy-access transportation, relaxed itineraries, and special diets.59 And as older consumers become more used to technologies such as laptops and smart phones, business leaders should expect them to become a major growth driver in these categories. Singapore’s telecommunications operator SingTel, for example, anticipated this trend by developing Project Silverline, which encourages donations of old iPhones, refurbishes them with apps developed specifically for senior users and commits to one-year sponsorship of talk and data plans for the beneficiaries.60

Advertising tactics to build product awareness will need to be adapted as well. Low-concept advertising campaigns pitched at seniors have been a staple of late-night television jokes—the Clapper sound-activated light switch, adult diapers, and reverse mortgages pitched by aging stars like Henry Winkler, who played the Fonz on the 1970s sitcom Happy Days. But companies that have latched onto these trends are becoming more sophisticated and nuanced in their marketing. In 2007, Unilever’s Dove launched Pro-Age, a line of deodorants, hair-care products, and skin-care products targeted at female consumers between the ages of fifty-four and sixty-three. The launch was accompanied by provocative ads showing unclothed models in its target demographic, complete with age spots, wrinkles, and gray hair. One of the spots in the campaign racked up more than 2.5 million views on YouTube.61 In anticipation of aging baby boomers’ needs and issues with the older brand image, Kimberly-Clark embarked on a series of clever repositioning campaigns from 2011 to 2013 for its Depend brand of incontinence products. The campaign involved younger, unexpected celebrities—including actress Lisa Rinna and pro football players—who were willing to break through the stigma associated with incontinence and demonstrate how well the product fits into an active lifestyle.62

Products and Services for Seniors

Smart marketers have always segmented their core markets by consumer demographics and other important characteristics. Around the world, companies, nonprofits, and public institutions are developing new products and services that cater to older people and are thinking in innovative ways about the lifelong value of their customers. Youth must be served, the saying goes. But so, increasingly, must the elderly.

The design of cities and social care will also need to be rethought with new consumer needs in mind. Housing developments with community spaces and tailored activities, retrofitted apartments, easy medical access, and infrastructure centered on shorter trips in electric golf carts may soon become mainstream. In Singapore, where the issue of an aging population has been on the national agenda since the 1980s, mass transit and housing policies, combined with projects such as City for All Ages, are gradually transforming communities to become more accommodating to the elderly.63 Even in India, a country better known for its youth bulge, the topic is very much alive. There are already over one hundred million people over the age of sixty; the elderly segment is expected to grow to over three hundred million by 2050, according to United Nations estimates.64 The first national Association of Senior Living in India was formed in 2011 as a trade association of companies serving the small, fragmented, but rapidly growing market for senior living communities.65 Real estate developers like Tata Housing and Max India Group have announced plans to create residential communities specifically for seniors.

In the private sector, retail, health-care, tech, financial, and leisure companies are among the early birds in developing tailored services and products for the graying market. Here, too, Japan leads the way. Malls are often designed as havens for teenagers and young shoppers. But in 2012 Aeon, a retail-focused conglomerate, opened a senior-focused mall in Funabashi in Chiba prefecture, the first effort in a larger push to reorient many of its 157 malls to tap into the ¥101 trillion ($1.18 trillion) consumption opportunity that Japan’s silver spenders represent.66 At the mall, people can use escalators that move at a slower-than-usual speed, get a medical checkup, and buy groceries that have price tags in large type. And for those who just want to meet new people, the mall offers a senior dating service—the Begins Partner program—which was perhaps one of the reasons about five thousand people waited to enter on opening day.67

Age-friendly customization of products and services in retail banking is increasingly common. Telephone, online, ATM, and physical touch points are getting a makeover to cater to customers’ differing visual, hearing, and access needs. In Canada, TD Canada Trust developed a toolbar, designed with a TV remote in mind, to help customers easily navigate the web, adjust font size and volume, and instantly access help. Brazil’s Banco Bradesco provides a phone for people with hearing difficulties. In Germany, Deutsche Bank has designed its ATMs to be as barrier-free as possible and equipped them with Braille and voice guidance.68 Aging-themed investing and tailored fraud protection services for customers with dementia and Alzheimer’s are examples of propositions that are likely to become more mainstream over the coming decade.

Beyond tailoring marketing, products, and services, companies and organizations have to innovate and conceive of new products as well. Steve Jobs famously noted that consumers didn’t know what they wanted until he showed it to them. Responding to—and anticipating—urgent consumer needs often drives significant innovation in product development. Deploying human and financial capital to fundamentally reimagine products for older people will likely pay significant “silver” dividends.

In 2013, Amazon launched a new retail initiative, the 50+ Active and Healthy Living Store, with nutrition, wellness, exercise and fitness, medical, personal care, and other targeted products. The company said it launched the initiative to “offer customers in the 50+ age range a place to easily discover hundreds of thousands of items that promote active and healthy living.”69 In the United Kingdom, Saga creates products and services exclusively for customers aged fifty and up, covering a range of needs from insurance and travel to health and dating. The company has roughly 2.7 million customers and a market capitalization of £1.7 billion in late 2014.70 Israel’s CogniFit developed a brain-training application that lets the elderly assess their cognitive skills and gives personalized brain training, which is rapidly spreading worldwide through its mobile app.71

In tech, Fujitsu has innovated extensively with a focus on the silver segment. In 2013, the company introduced the second generation of senior smart phones called the Raku-Raku (“easy, easy” or “comfortable, comfortable”). Modeled on an Android device, it is designed to be easier on older eyes and bodies; the touch-screen controls are more like buttons, scrolling only goes up and down, and text and icons are large enough to see clearly without bifocals. The phone can even slow down the speech of the person at the other end of the line. After reaching more than twenty million handset sales in 2011, Fujitsu made the product available in other countries, like France, through local partnerships.72 Fujitsu in 2014 also issued a prototype of a cane with a built-in navigation system that helps people get where they’re going and allows them to be tracked. Future iterations will have the capability to monitor heart rate and temperature and to call for help if necessary.73

The cane is still in the works, but it stands as a powerful metaphor. Here’s a passive object, a tool that most consumers spend their lives trying to avoid, that is synonymous with debilitation. But technology paired with an understanding of an evolving market has quickly shifted and reset the way we think about it. It’s proactive, highly useful, less stigmatizing, and empowering.

This cane, in other words, is able.

![]()

*With defined-benefit (DB) plans, an employer pays its retired employees a fraction of their salary at retirement for the rest of their lives. In contrast, defined-contribution (DC) plans require the employer to match a portion of employees’ annual contribution to their retirement accounts. While DB and DC plans come in a wide range of flavors, fundamentally, DB plans place the risk of financial solvency and longevity of payments on the employer or other plan sponsor; DC plans shift these risks to employees.