There are few things that feel as good as the sun on your face, clean mountain air in your lungs and sleeping under a bright, star-filled sky. But the sun does not always shine and rain clouds often obscure the stars. Nature, in short, is not always your friend and you need to make sure you are properly sheltered and secure in the field. Any fool, as we used to get told in the military, can be uncomfortable.

In this chapter we will discuss not only how to choose the best campsites but also the different kinds of shelter available to you, both man-made and natural. Then I’ll give you some tips on how to construct shelters by using some of the abundant materials the natural world has to offer.

CAMPSITE SELECTION

When you’re out in the field, chances are that you’ll spend more time in your tent than in any other single place. You’ll sleep in it, use it as shelter from bad weather, rest in it and – depending on what type of tent it is – cook your meals in it. So it makes sense to ensure that you pitch camp somewhere suitable. A few minutes checking the ground and the surroundings could save you a lot of aggro later on. Few campsites are a hundred per cent perfect (that’s half the fun of the wild), so you’ll always have to compromise a bit, but these are the main things you need to think about when selecting your position.

Slope

It goes without saying that you’ll get a better night’s sleep on flatter ground than on a steep slope, but that’s not the end of the story. A very gentle incline will allow rainwater to drain away from the campsite and stop it from becoming a boggy nightmare. If you do find yourself camping on level ground, try to choose an area where the soil is capable of absorbing any rainwater. A good way of judging this is by driving a tent peg into the ground: it should be soft enough to take the peg, but not so marshy or wet as to swallow it. If you camp in a dip, you might find the area prone to mist and midges. Higher up is better, but not so high up that your tent poles attract lightning in a storm. (I once met a man in the Costa Rican jungle who had been struck by lightning while in his tent. He told me how he covered his face in terror, but the flash was so intense he had actually seen the bones of his hands through his closed eyes. He was very lucky to have survived.)

Air and wind

Before you pitch camp, try and work out which way the prevailing winds come from. You want the back of the camp to face the wind so that the camp itself provides shelter. Try not to camp somewhere too exposed, as severe winds can be devastating to a camp (and storms always seem to happen at 3 a.m. when you are cosy in your sleeping bag!); but equally, try to make sure that there is enough space around your camp to allow the sun to dry the ground after a rainstorm and for air to circulate freely.

Supplies

Nothing is going to wear you out quite so fast as having to walk a long way carrying wood or water. If you can, camp near a decent supply of both.

Safety

Although it’s a good idea to be near a wood supply, you don’t want to camp near dead trees, or even live trees that have big, overhanging, old-looking branches. In a storm, these can easily break off and fall. The same is true of trees that are leaning precariously in your direction.

If you’re camping on a slope, check uphill for any loose boulders. And make sure you’re far enough from any stream or water source that might be in danger of flooding as a result of heavy rainfall.

Most animals will avoid you, but it’s worth a quick check that you’re not camping too close to any animal runs or holes.

PITCHING TENTS

Once you have decided on the general location of your camp, it’s worth taking a little bit of time to lay it out properly. Make sure there’s enough space between tents for privacy (people are always secretly grateful for their own personal space); and work out where specific features such as the camp kitchen or the woodcutting area are going to be.

Lay out your groundsheet, but don’t start hammering your pegs in yet. First of all, examine the area under the groundsheet very carefully. Remove any stones, twigs or knobbly bits and do it thoroughly: they might look just like little pebbles now, but after several hours of lying on them you’ll feel like you’re sleeping on Stonehenge! (I have often been guilty of overlooking this task when tired at the end of a long day, and I always regret it.)

Once the ground is cleared, stake down the corners of your tent before erecting the poles or hoops. You can then readjust the corner pegs to make sure everything is in its proper place, before inserting the rest of the pegs and covering with the flysheet. You should be able to tell just by looking at it whether your tent has been properly erected: the shape will be symmetrical and the canvas taught and wrinkle-free. The flysheet and the inner sheet should not be touching; if they do they lose their waterproof properties.

NATURAL SHELTERS

Tents – especially modern ones – are brilliant. But you don’t always have one. Maybe you’ve been stuck out in the wilderness. Or maybe you really want to go old school and back to nature and construct your own shelter from the materials at hand. This is always the most fun and rewarding option. It adds an exciting dimension to your trip, and it’s a great skill to learn.

The easiest kind of natural shelter is the one that’s already there. Unfortunately, suitable natural shelters can be few and far between, and even if you are lucky enough to stumble across one, you need to be aware of the difficulties they can present.

Caves

Caves might seem like the ideal natural shelter. After all, they’ve been there for thousands of years and the earliest humans used them as dwelling places. And it’s true that a good, dry cave can be a great place to stay. But most caves are not like this. They’re often wet and cold and once the sun goes down they can be impenetrably dark. Sounds a bit less enticing now, doesn’t it? If you light a fire in an unvented cave, it will become full of lingering smoke. You also need to be careful of caves that play host to crowds of bats. There is a fungus present in their droppings that can cause a sometimes-fatal illness called Darling’s disease – a decent reason to avoid bat pooh (or bird pooh for that matter). And, of course, in some parts of the world, there are vampire bats, which will suck your blood during the night without you even feeling it. They inject an anti-coagulant that means you stream blood, and they target the soft areas like your eyes, head and fingers. A friend of mine woke up with his hair soaked in blood after being bitten by vampire bats. This can be an annoying way to start the day!

Overhanging cliffs

Again, these aren’t very common but they can provide good shelter, especially if they are south facing – i.e. into the sun. If you decide to set up camp under a cliff, you can estimate how much protection you’ll get during a rainstorm by feeling the ground. If it’s damp, chances are you will be too! Because of their situation, cliff overhangs can be draughty. (This is called the Venturi effect, which is where wind speeds up as it gets compressed when it hits a cliff face.) If you have the materials available, you can protect yourself from the winds by building low walls around you; if not, a warm sleeping bag or bivi could save you from a cold night’s sleep.

Tree canopies

If the canopy overhead is thick enough, it can be sufficient to protect you from all but the fiercest rainstorms, but it can only really be a short-term shelter. Don’t write this option off, however: it can be a lifesaver and can relieve you of hours of unnecessary work if you get the right trees. Remember: the smart Scout uses what nature has already provided.

MAN-MADE SHELTERS

From the simplest wigwam to the tallest skyscraper, all man-made buildings essentially do the same thing: keep the rain out and the warmth in. You don’t need to be an architect to create simple shelters, and if you can master a few basic principles, you’ll be amazed how versatile such man-made shelters can be. All the shelters described here are designed so that the rain runs off their roofs. Dig a ditch about a hand’s span depth around your shelter and you will avoid being flooded from the outside.

But here’s a word of advice before you start. The following shelters all have one thing in common: they need basic materials, mainly logs and foliage, which you’re most likely to find in a forest. Even if you have to go some distance out of your way to find woodland to shelter in, it’s worth it. You’ll more than make up for lost time by having the materials close at hand.

Lean-tos

There are two basic lean-tos: the fallen-down-tree lean-to and the open-fronted lean-to, both well suited to any environment where there are trees.

The fallen-down-tree lean-to

The fallen-down-tree lean-to is probably the simplest man-made shelter you can create. It also has the advantage of not needing any ropes or cordage.

Stage 1

As the name suggests, the first thing you need to find is… a fallen-down tree! In woodland areas these are very common, but try and find one that’s the right size (of course, a suitably shaped boulder can perform the same job). The tree forms the high wall of your triangular lean-to. If it’s too low you won’t have much space and water will drain away less successfully; if it’s too high you might have difficulty insulating the open ends. Aim for a height of about a metre.

Stage 2

The roof of the lean-to is constructed using long, straight branches – either windfalls or, if necessary, ones that you have cut from existing trees. These should be laid close together so that there are as few air gaps as possible.

Stage 3

Once you have constructed the basic shape, you need to insulate the roof. There are all sorts of materials you can use to do this: large bits of bark, leaf mould from the forest floor, even branches thick with leaves. Don’t cut corners when you’re doing this: these materials are going to keep the rain out and the warmth in. Cover your lean-to well, and try to arrange the materials much as you would tiles on a roof, with the upper ones overlapping the lower ones (i.e. start from the bottom and work upwards). This will help the rain run off the roof without leaking into the shelter.

Stage 4

Once the roof is finished, you need to block off one of the open ends to prevent drafts. If you’re expecting the weather to be particularly cold, you can block both ends of the lean-to to increase its insulating properties. Use the same materials as you did for covering the roof, or alternatively build a ‘wall’ of logs.

The open-fronted lean-to

Open-fronted lean-tos are very well suited to cold, dry environments because they rely on a fire built on the open side for their warmth. The heat radiates inwards and reflects down from the roof. The downside, of course, is that they are less suitable for wet weather, or when you’re staying somewhere you can’t light a fire.

The principle is the same as the fallen-down-tree lean-to but, in the absence of a fallen tree, you need to construct something sturdy enough for the slanted roof to lean against.

Stage 1

To make the frame, you need to locate a straight branch that is taller than you, two straight poles about 3 metres long, and two upright poles about 1.5 metres long, preferably each with a forked end. Construct the frame as shown, tying the joins tightly with rope or whatever cordage you have at your disposal (see here).

Stage 2

Collect enough long, straight branches to create the lean-to roof as shown below. You want the roof to be at an angle of between 45° and 60° (don’t worry; you don’t need to get your protractor out – remember the rule of thumb, ‘near enough is good enough’!).

Stage 3

Now cover the roof with the same insulating materials you would use for a fallen-down-tree lean-to (see here). Remember, the more thorough you are at this stage, the warmer and drier you’ll be. Cover each end of the lean-to with insulating material as well. If your roofing material is lightweight, you can weigh it down with some more branches in case the wind picks up.

Stage 4

A fire is crucial to the success of an open-fronted lean-to. As you’ll be lying down, you want to make sure that your fire is the same length as you are if you’re going to stay properly warm. (See Chapter 4 for the lowdown on firecraft.) If you’re building more than one open-fronted lean-to, position them so you have two facing each other – that way two people can share the heat from one fire. Both of you can help keep the fire stoked during the night, and, of course, it is more sociable.

Tripod shelters

Tripod shelters – or wigwams – are one of the oldest kinds of man-made shelter. The large style of shelter that you might be familiar with from stories about Native Americans are good, sturdy structures; but because of their size they can be difficult to cover and thatch, which makes them less well suited as short-term shelters or in inclement weather locations. However, a three-pole shelter can be a useful alternative to the other lean-tos described here: it doesn’t require a fallen-down tree and, if properly constructed, it can offer more insulation than an open-fronted lean-to.

Stage 1

Locate a long, straight branch that is slightly taller than you, plus two shorter straight branches. The size of these smaller branches will depend on your own size: the finished shelter needs to be just big enough for you to fit inside when lying down. Construct the frame as shown, tying the joins tightly with rope or whatever cordage you have at your disposal. It is best to tie all three poles together at the top when the poles are laid down; then splay them out afterwards. This will ensure the knot remains good and tight.

Stage 2

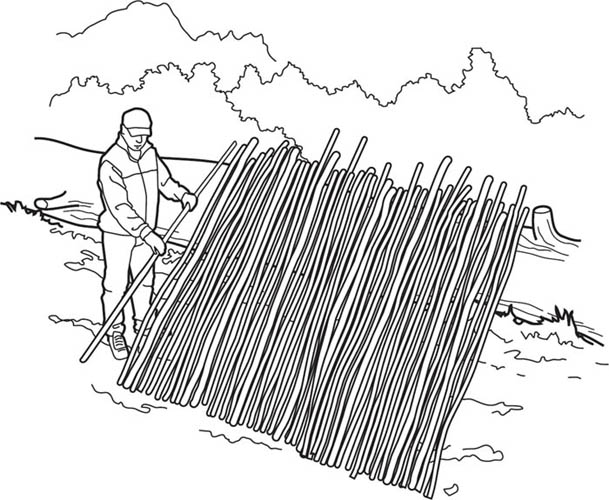

Collect enough straight branches to line the walls of the shelter as shown below. Remember to place these as close together as possible to increase insulation and stop water leaking in.

Stage 3

Cover the tripod shelter with leaves, foliage or whatever natural insulating materials you can find. Make the covering as thick as possible.

Tying knots is one of the most useful skills you can learn for when you’re out in the wild. But before you tie them, you need something to tie and there’s a limit to the amount of rope you can reasonably carry with you. If you’re going to live successfully in the wild, therefore, you need to be able to make your own cordage – another word for thread, string or rope. Happily, it’s a lot easier than it sounds; and it can be more versatile than you think. Natural cordage can be used for shelters and other campcraft projects; it can also make bow-strings, fishing lines, snares and even ‘cotton’ for sewing. All in all, it’s a skill worth learning.

Almost any fibrous material can be turned into decent cord. If these cords are long enough, they can then be plaited into quite sturdy ropes. But first you need to gather your supplies. In your search for suitable cordage material you need to consider four things:

This might sound like quite a demanding list, but, in fact, natural materials that match these requirements are reasonably common: tall grasses; weeds such as stinging nettles (grip the nettle at the base of the stem, pinch your fingers together and run them up the length of the stalk – the leaves will all come off without stinging you); seaweed; fibrous materials from the stalks of certain shrubs; even the moulted hair of animals. Probably your best source of cordage material, however, comes from the inside of dead tree bark, particularly willow and lime. Simply loosen the fibrous material at one end of the bark and pull it off in long strips. Then separate these strips until you have lengths of the required thickness.

You should also bear in mind that most natural fibres will shrink as they dry, which makes the weave looser. However, some materials can be more difficult to process once they are dried out. A good compromise is to soak dry materials in water before you process them: they will shrink a lot less than when they dry from their natural state. (This process is called ‘retting’. If you take pieces of bark off young lime, willow or sweet chestnut trees and soak them in a river for a while, the natural fibres will free themselves from the bark. If these are left to dry they will be soft, pliable and ready for use.)

Once you have your raw material, you need to process it into something useful. There are lots of different ways of doing this. The method I’m going to explain to you is very easy, and will produce versatile cordage that you can use in all sorts of situations.

Making your own laid cordage

Laid cordage is the term for any rope made from fibres that are twisted together.

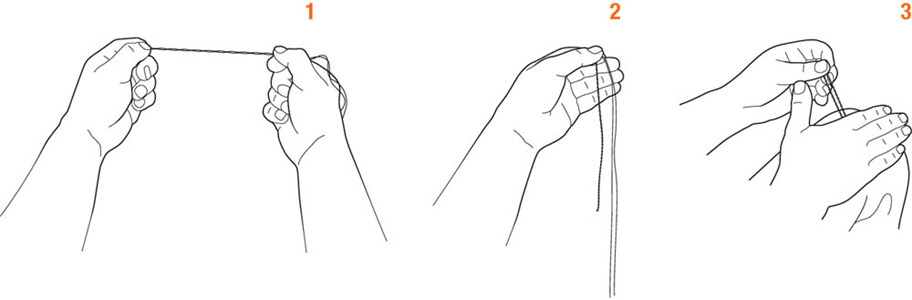

Stage 1

Take a long, single fibre. Twist it repeatedly in one direction until it naturally wants to form a kink.

Stage 2

Fold the fibre about a third of the way along. Don’t be tempted to fold it in half, as this will give you a weaker finished product.

Stage 3

Grasp the fold between the finger and thumb of one hand. Place the doubled-over fibre on your lap and use the palm of your free hand to roll it one full roll away from you. You are not trying to make the fibres overlap at this stage; just aiming to twist each strand individually.

Stage 4

Keeping your palm firmly held down, to stop the cord from untwisting, release your other hand. The cord should twist neatly.

Stage 5

Pinch the cord where the twisting ends and repeat the process until you are 4–5cm from the shortest end. To continue, lay another strand of fibre up to the shortest end and carry on the process as before – the new fibre will automatically entwine itself into the existing cord. When you’ve finished rolling the cord, just tie it at the loose end to stop it unravelling. If the cord is too thick to do this, you can tie a separate piece of cord round the end instead.

Your finished cord will be substantially stronger than your original fibres, but you can make it stronger still by folding over the existing cord and repeating the process. If you do this, make sure you roll the cord in the opposite direction to the way you started.

So, you’ve made your cordage. Now you need to know how to use it. Generally speaking, a cord is no use unless you’ve got a few knots up your sleeve. There are literally hundreds of different types of knot, and you could spend half a lifetime learning them all. You’re better off learning a few, and learning them really well, then getting out and using them! If you learn the knots listed below, you should always find you know one that performs the job you want to do. Here they are, then – Bear’s Top Ten knots.

TRAINING EXERCISES

You can practise this process easily at home without having to go out and forage for materials. Just use lengths of thin string (you can cut out stage 1 of the process). You’ll be amazed how quickly it turns something insubstantial into something very sturdy.

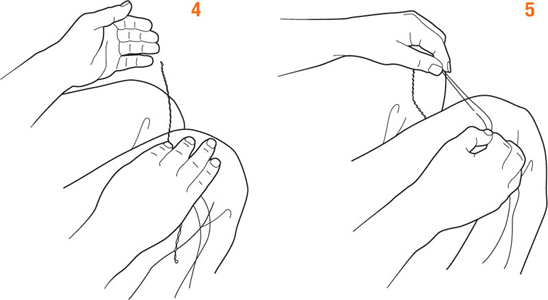

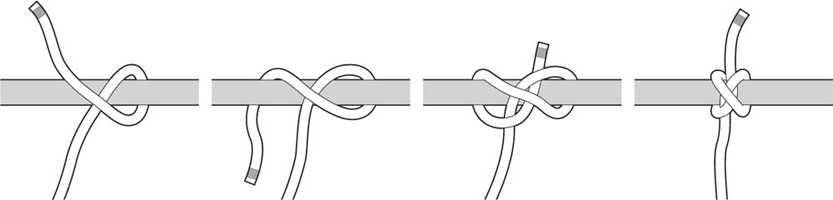

Bowline

This is probably the most useful knot you’ll ever learn. It’s used to form a loop at the end of a rope. It can be tied very quickly and it won’t slip or tighten. There’s a useful mnemonic you can use to remember how to tie it.

1) The rabbit hole 2) The rabbit comes out 3) It runs round the tree 4) It goes back down its hole

If your life depends on a bowline, add a half hitch in the working end when finished. This makes it a hundred per cent secure.

Buntline coil

Not so much a knot as a convenient way of storing your rope without it getting all tangled up.

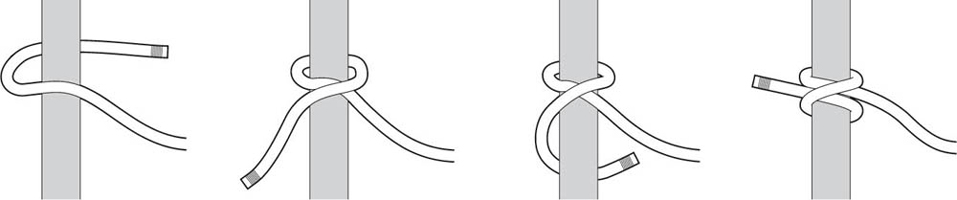

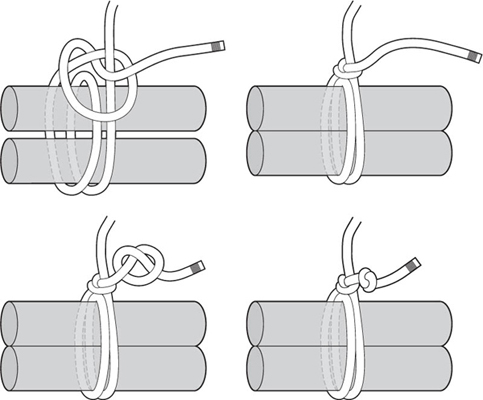

Clove hitch

Use this to attach a rope to a horizontal pole or post.

Constrictor knot

This is really useful for tying the neck of a bag or sack.

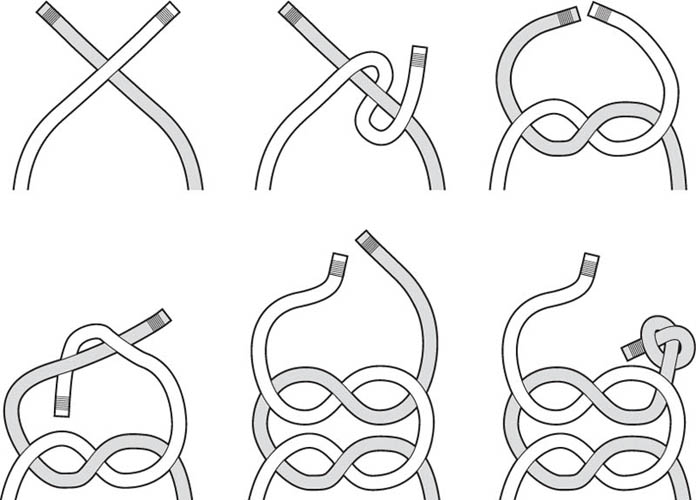

Figure of 8 loop

This knot is easy to learn, reliable and – crucially for a good knot – easy to untie. It is a very popular knot with climbers and sailors, but you can bet you’ll find a use for it in the field. It is particularly useful when the final loop can be passed over a post.

Also known as the locking knot, this is a good knot for general construction, as it can bind two sticks together tightly. This knot is a faster and simpler version of the sledge knot but once you’ve tightened it, put a couple of half hitches at the end so it can’t ever work loose.

Sledge knot

This is the ultimate construction knot, you can put a radiator hose in a car with it and it will hold. However, you cannot undo this knot; you will have to cut it if you no longer want to use it.

One of the most common knots, and used to tie two pieces of rope together provided they are of equal thickness. It’s easy to untie. Add a half hitch to each end if you need to make it a hundred per cent secure.

Sheet bend

This knot performs the same function as the reef knot, but this one works for ropes of different thicknesses.

Timber hitch

This is a good temporary knot for dragging wood or other objects, and also as a general lashing. It will tighten when under strain, but comes undone easily when the rope is slack.

CAMPCRAFT PROJECTS

If you’re staying in one camp for a while, it is always worth spending a little bit of extra time adding a few simple creature comforts. I’m not talking about a TV, but more fundamental things like beds and washbasins. Obviously you can’t take the kitchen sink with you when you’re out in the field; but with a little ingenuity it’s amazing what you can create using easy-to-find, natural materials. You’ll probably discover that you won’t have time to make many of these projects for one-off, overnight stays; but for longer-term fixed camps they can make your life a lot easier and more comfortable. With campcraft projects there are no hard and fast rules: you’ll find yourself improvising and adapting all the time and that, of course, is half the fun. But to get you started, here are a few ideas.

A camp bed

Chances are that you’ll have some sort of inflatable mattress with you, and, if you’ve read my tips here, you’ll know that it’s essential to have something to keep your body off the ground. However, an inflatable mattress can absorb water – not a big issue if it’s being used in conjunction with a bivi bag (see here), but a potential problem if you’re just sleeping under a tarp. Even if the air cavity keeps this moisture away from your body, it’s annoying to have a wet mattress: when you roll it up for storage it can become mildewed and unpleasant.

The solution is to improvise a camp bed, which is a lot easier than it sounds.

Stage 1

Find a couple of substantial logs about a metre long and place them parallel to each other at your head and foot positions, about 15cm away from the top and from the bottom of your mattress (so, if you have a 2-metre mattress, place them 2.3m apart).

Stage 2

Now find several long, straight branches about wrist thickness and support these on the logs, securely fastened with a timber hitch (see here) to form a raised platform. Alternatively, use your knife to cut notches in the end logs on which the poles can rest without moving. You can now lay your air mattress on to your wooden platform and you’ll be raised from the ground.

A camp table

A camp table can be a real asset, for obvious reasons. A table is little more than a raised platform: as long as it’s flat enough, the stump of a tree will do the job. But if you’re in camp for a few days, you’ll probably find that you want something bigger and more permanent.

If the ground is suitable, you can make a good camp table by digging two trenches opposite each other, then putting the displaced soil along the outer edges of the trenches to use as seat backs. The bit in the middle forms the platform or table.

The following drawings show a really good way of constructing a wooden table with seats. Don’t worry if the wood you find isn’t as neat and straight as the wood you see in the picture – (it never is!) – but try and get it as straight and as balanced as possible. Don’t be afraid to use your sharps to cut the poles to the right size and to indent the poles where they join. Use a sledge knot or jam knot (see here) to lash the poles together.

Camp chairs

Camp chairs can be invaluable, especially if the ground is soggy. With a bit of practice, you can construct a camp chair in about 15 minutes. Just follow these diagrams. The secret is to find three sturdy forked branches that you can cut into the shapes shown here. Once you have constructed the frame, cut yourself some shorter branches and lash them to it using a sledge knot or jam knot (see here).

Camp lights

We’re so used to being able to flick a switch to turn on a light that it’s easy to forget how dark it can be outside at night. This is especially true in the jungle where it gets pitch black in minutes when the sun goes down, as all natural light is lost in the dense canopy of jungle foliage. I have been caught out on several occasions by not being prepared enough by sundown. Trying to make camp in the jungle, in the dark, is hard work!

I once made camp in the Transylvanian mountains, which have the highest population of bears in Europe. Only a few hours earlier I had encountered, at close quarters, a huge brown bear, which only served to make me even more determined to make sure my camp that night was as safe as I could build it. I rigged up a simple trip-wire perimeter all around my small shelter. If this was triggered it would dislodge my mess tin that was full of stones and suspended up a tree. At one point in the night I was certain that I heard a noise and went out to check the perimeter wire. But it was absolutely pitch black and I had no torch, and in the process of checking the wire I triggered it accidentally. I almost jumped out of my skin when the stones came crashing down around me, piercing the silence of the night. Sometimes our imagination is our own worst enemy!

If you’ve got a fire going, that will give you a bit of light; and a torch is good for directional light, especially in an emergency. It’s a great idea, though, to carry a few candles with you. Candles don’t stand up by themselves very easily, however. A good trick is to stick your knife into a tree trunk, flat side up. Melt a few drops of wax on to the blade, then stick your candle on to it. (Alternatively use melted wax to stick your candle on to any flat surface – just make sure it’s well away from anything flammable.)

But what if it’s windy? I’m going to show you a neat way of using a glass bottle to make a candle-holder that will keep the wind out. To do this, you need to cut the bottom off an empty glass bottle. Sounds impossible? Bear with me! With care, this can be done safely in the field without any fancy equipment. All you need is a thin piece of wire, a fire and cold water. Heat the wire until it’s red hot then, using gloves to protect your fingers, tie the wire around the bottle where you want to cut it. Plunge the bottle into the cold water and it should break cleanly and easily. Push your candle into the ground (or you can use the melted wax technique to stick it to something) and then place the bottle upright, over the candle. Hey presto: a wind-proof lantern!

BEAR’S SECRET SCOUTING TIPS

Don’t throw away butt ends of candles or the wax that drips off them. They can be melted down into an empty tin can with one end cut off. Insert a small piece of string into the melted wax, let it harden and you’ve just made yourself another camp light (and a potential lifesaver if you run out of other light sources).

If you’re on an expedition with a group and one of you has brought along a lightweight bowl, it’s straightforward to construct a stand for it so that you have a raised washbasin. Arrange the three poles in a tripod formation about 30cm from the top using a sledge knot or a jam knot (see here). The bottom parts of the poles will form the legs, while the top parts make a cradle for your bowl. (For a more elaborate camp washstand suitable for longer-term fixed camps, see here.)

IMPROVISING IN THE FIELD

If you don’t have a bowl, a piece of tarpaulin can be laid over the cradle of a tripod stand with a length of cordage wrapped round to secure it. This will make a simple, improvised camp washbasin.

Real-life campfire story

There are many extraordinary stories about feats of endurance and survival in which intrepid explorers like Scott and Amundsen have battled with the elements, or wartime prisoners have escaped across hostile jungles and mountains. These can be spectacular examples of fortitude and determination. But the truth is that you don’t have to be on an expedition in the Antarctic to find yourself in a survival situation. It can happen right on your doorstep. Having a small amount of simple, logical knowledge – such as how to tie a few knots or use certain materials to make shelters, fires and rope – can save you a lot of misery.

A friend of mine was on Special Forces selection. Having completed the first few stages, he found himself on the run during what is now called the SERE phase – Survive, Evade, Resist, Extract. This wasn’t in some frozen wasteland or in the jungles of Borneo, but in the hills and valleys of North Wales!

Pursued by the hunter force, whose job it was to search for and capture the SAS hopefuls, he found himself charging through a dense coniferous forest with men and dogs hot on his heels. Running through a region of closely planted trees, he didn’t have much opportunity to assess his situation or select his best route. He found himself bursting out from the treeline and jumping straight into a pond. He had got away but it was October, and the water was sufficiently cold to knock the air from his lungs.

The mercury had dropped well below freezing on the previous four evenings and the wind was blowing. He soon realized this could rapidly turn into a life or death situation. Lighting a fire wasn’t an option, as it would alert the hunter force to his whereabouts. His only alternative was to construct a shelter to protect him from the biting wind and try to regain some warmth.

The thick canopy of the forest meant there was not much undergrowth. He clawed away at the forest floor to assess the depth of the spruce needles – about 45cm – not enough to get him below ground level. He needed to build upwards but had no rope or building materials with which to do this.

As he’d been digging, however, he’d come across a number of spruce roots. The spruce root is one of the best naturally occurring materials for tying knots. When split down, they are ideal for lashing together a temporary lean-to shelter. My friend rapidly started to unearth as many roots as he could. He split them down and then collected dead branches from the forest floor. In next to no time he had constructed a low, tactical shelter. All he had to do now was pile spruce needles and forest debris over the windward side and his shelter was complete. Suddenly, a night in the freezing temperatures, in the dark, when soaking wet and in a gale, was survivable.

Necessity, as the old saying goes, is the mother of invention. In other words, if your need is great enough, and you think long enough and hard enough, you can eventually come up with a solution to a challenge – even if you have to improvise materials and tools. You don’t need yards of nylon cord and tarpaulins in the wilderness; with a bit of common sense you can not only survive, you can make yourself very comfortable.

You may not be in a survival situation, but in the field there are always going to be times when you need to improvise. You’ll soon realize that the natural world is your outdoor shop, hardware store and tool shed all rolled into one. And all it requires from you is the willingness to get in there, think smart, smile and never give up! That’s the scouting way.