Economic Reproduction

The previous chapter examined a single circuit of industrial capital. For capital as a whole, there are a large number of different circuits, each moving at its own pace and each expanding at its own rate, and these circuits must be integrated with each other. Marx analyses these processes in Volume 2 of Capital by dividing the economy into two broad sectors, department 1, which produces means of production (MP, purchased with constant capital, c) and department 2, which produces means of consumption (purchased by workers out of the wage equivalent of variable capital, v, and by capitalists out of surplus value, s). This chapter examines the process of reproduction of capital as a whole. It begins with simple reproduction, where there is no capital accumulation. It subsequently examines expanded reproduction, where part of the surplus value is invested. Finally, it considers the social reproduction of the capitalist economy.

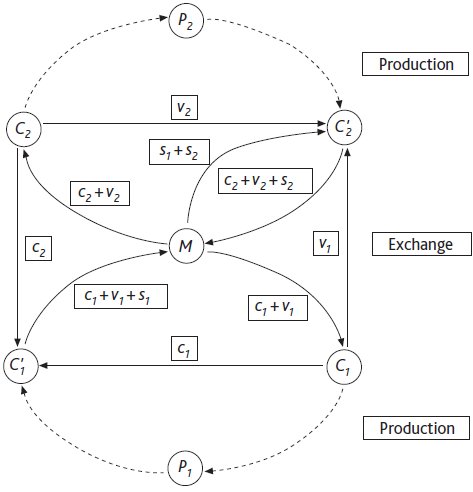

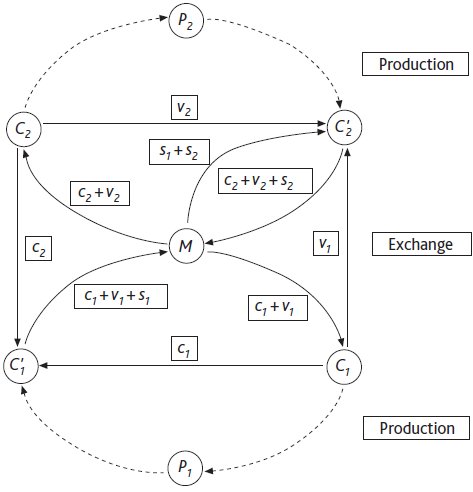

In Figure 5.1, the balance between departments 1 and 2 in conditions of simple reproduction is illustrated by a flow diagram showing values and commodities from each sector and money. The two circuits are shown, M1 – C1… P1 … C’1 – M’1, and M2 – C2 … P2 … C’2 – M’2 (with M’1 and M’2 being absorbed into the central pool of money, M, after which they flow out again). The figure also shows the commodity flows. These go in the opposite direction to the money that is used to purchase them, with workers and capitalists buying consumption goods from department 2 with their wages, v1 and v2, and surplus value, s1 and s2, and capitalists buying means of production, c1 and c2, from department 1 (workers do not buy means of production, and we ignore savings).

Figure 5.1 Economic reproduction

If there is no technical change, and if the capitalists spend all their surplus value on consumption and merely repeat the previous pattern of production, the economy can reproduce itself at the same level of activity. This is what Marx calls simple reproduction, which implies a certain balance between the values produced by the two departments. The value of the output of department 1 is c1 + v1 + s1, and the value of its sales of means of production is c1 + c2. So in simple reproduction:

For department 2, similarly, the equality of values of output and value of sales of means of consumption gives:

c2 + v2 + s2 = v1 + v2 + s1 + s2

Each of the above expressions simplifies to:

v1 + s1 = c2

This is Marx’s famous equation for balance between the two departments in simple reproduction.

If the capitalists do not consume their entire surplus value, but spend part of it buying additional means of production, capital accumulation takes place. In this case, capitalists’ purchases of means of production, c1 + v1 + s1, for the next period exceed current use, c1 + c2. It follows that, for expanded reproduction, c1 + v1 + s1 > c1 + c2:

v1 + s1 > c2

with the extent of the inequality depending upon the rate of accumulation.

Marx’s reproduction schema have been interpreted in various ways. One of the most popular is that they offer an analysis of conditions of economic equilibrium, either static (in the case of simple reproduction) or dynamic (expanded reproduction). Alternatively, taking mainstream growth theory as its model, expanded reproduction is seen simply as an enlarged version of simple reproduction. The economy looks the same in all respects, except that it is bigger.

Neither interpretation is within the spirit of Marx’s analysis. First, his methodology is sharply opposed to the use of equilibrium as an organising concept for the analysis of capitalism. Second, in the reproduction schema Marx is concerned to show how, despite the seemingly chaotic co-ordination of producers in exchange, both simple and expanded reproduction exist within the capitalist system. In other words, simple and expanded reproduction are not alternatives, either theoretically or empirically. Rather, the former exists within the latter: expanded reproduction simultaneously depends upon and breaks with the conditions associated with simple reproduction that are its starting point – both in aggregate value magnitudes, and in the values of commodities themselves, as these are subject to productivity increase as a result of accumulation. Furthermore, Marx never draws the implication, as in general equilibrium theory or for the proponents of laissezfaire, that different producers and consumers are harmoniously co-ordinated through the market at high levels of employment of resources. Rather Marx’s schema points to three separate balances required by the reproduction and accumulation of capital.

The first is in values, as has been illustrated above. The second is in money and prices, since the circuit requires these to balance as flows take place. And, third, the need for balance applies to use values too, for the appropriate quantities of commodities have to be produced and exchanged with each other, both within and between the two departments.

According to the schema above, the value quantities displayed have an unspecified quantitative relationship to the use values involved. However, they cannot be entirely independent of each other. Given the value flows, asymmetric productivity growth, for example, would lead to the transfer of resources between the two departments and to a change of the use value flows between them. Therefore, Marx’s balance between the two departments must involve not only the co-ordination across the economy between the value flows already specified, together with the complementary flows of money, whose magnitudes are determined by the price system, but also the balance of flows of use values determined by technology, the composition of the output, and so on.

The diagram of economic reproduction in Figure 5.1 can be used to reinforce the partial views of the economy that were presented in the light of the single circuit of capital in the previous chapter. Little is added qualitatively, but the figure suggests what might be considered to be the factors determining the level of economic activity. Note, first, that mainstream economic theory and ideology tend to focus on the central ‘box’ of exchange activity, relative to which the two spheres of production appear to be extraneous. Generally, this supports the erroneous view that production can be taken for granted, or that it is simply a technical relation that forms the unproblematic basis for exchange relations, as in the neoclassical production function.

This is most apparent for neoclassical general equilibrium theory, where ‘free market’ exchanges are considered sufficient to guarantee equality of supply and demand at full employment of economic resources. And, in stability analysis, it becomes a question of whether disproportion between the various quantities embodied within the circuits is self-correcting through price movements in response to excess supplies and demands.

For Keynesian theory, the role of aggregate demand becomes determinant. If we focus on the investment multiplier, the level of c1 + c2 assumes a central role. If we also include the role of consumption, then this expenditure out of national income (v1 + v2 + s1 + s2) also becomes important. In this form, the consumption function has more affinity with the post-Keynesian methods of determining aggregate demand, in which income is divided into wages and profits. But the important point remains that, from these perspectives, a particular set of expenditure flows drives aggregate economic activity. However, in these approaches there is no role for the production of surplus value and the conflict between capital and labour over this fundamental economic relation.

A more sophisticated post-Keynesian economics includes the role of money. In this approach, the level of economic activity is determined by the size of the flows of money streaming out of the central pool, M. If these are restricted, either because of entrepreneurial timidity or through contractionary monetary policies imposed by the central bank, the economy will falter. The roles of the banking system and the rate of interest are taken up in Chapter 12. Here it is important to note that, from this point of view, the source of unemployment is to be found in insufficient exchange activity, which determines the (in)ability of the economy to generate profitability. In Keynes’s own theory, this depends largely on waves of pessimism, in which poor expectations about business profitability (and expectations of high interest rates) become self-fulfilling prophecies. More generally, recent developments within mainstream economic theory have given (so-called ‘rational’) expectations a considerably enhanced role in determining the path of the economy.

Finally, a more radical theory of the economy views the level of economic activity as being determined by distributional relations between capital and labour. Such a view is associated ideologically with both the right and the left, with the former arguing that the power of trade unions needs to be curbed to restore profitability, and the latter arguing that the conflicts involved are irreconcilable within the confines of capitalism. Analytically, this outlook depends on a ‘fixed cake’ understanding of the economy, in which national income v1 + v2 + s1 + s2 is divided between the two classes, with one gaining only at the expense of the other. For example, if wages, represented by v1 + v2, rise too much, then profits, represented by s1 + s2, must fall, and this undermines both the motive and the ability to accumulate.

Despite its ‘radical’ appearance, this view diverges sharply from Marx’s own presentation of the structure of the capitalist economy. The attribution of a central role to distribution in the determination of profitability is only possible by confining the analysis to (one part of) the arena of exchange. Once the sphere of production is incorporated as well, the apparent symmetry between capital and labour, in distributional relations and in receiving profits and wages out of national income, evaporates; for the payment of wages is a precondition for the production process to begin (or, more exactly, this is true of the purchase of labour power, whose actual payment may well come later). In contrast, profits are the residual after the payment of wages and other production costs, rather than being a ‘slice of the cake’ with a size that may be negotiated in advance. For Marx, the distributional relations between capital and labour are not of the fixed-cake variety, even if, ceteris paribus, profits are higher if wages are lower (although post-Keynesians might argue otherwise in view of inadequate demand). Profits depend first and foremost on the ability of capitalists to extract surplus value in production: whatever the level of wages, the capitalists need to coerce labour to work over and beyond the labour time required to produce those wages, with a productivity that depends both on the machinery available and on the level of discipline in the workplace.

Uncertainty about the production of surplus value is only one of the aspects of uncertainty facing the capitalists. Four other types of uncertainty are also relevant. First, having produced surplus value, capitalists are uncertain about how much can be realised until the output is sold. Second, the extraction of surplus value under competitive conditions leads to continuous productivity-enhancing technical change. However, it was shown above that technical change disrupts the value and use-value balances in the economy (and may contribute to antagonistic relations on the shop floor), further increasing uncertainty. Third, as is shown in Chapters 12 and 14, credit makes the resources of the entire financial system available to individual capitalists, facilitating an accumulation of capital that cannot always be sustained and creating conditions which may lead to financial and economic crisis. For example, credit might mislead industrial capitalists into anticipating favourable returns when none is forthcoming and, when fresh credit is used to pay for maturing obligations, the over-expansion of accumulation might create conditions of economic crisis. Finally, uncertainty becomes even greater when trading in money itself takes place, creating a class of money dealers only loosely connected to production and trade. Trading in money and money-related instruments is likely to lead to destabilising speculation and fraud, creating further uncertainty even for those not directly involved in such activities.

On the one hand, for Marx the production of absolute and relative surplus value is crucial to the understanding of distributional relations; but the latter cannot be read off from production conditions alone. On the other hand, uncertainty generated by capitalist production (rather than the shifting humours of industrial and financial capitalists) plays an essential role in the production of surplus value as well as in the unleashing of crises.

The previous sections have focused on simple and expanded reproduction from within the economic system alone. In principle, with one crucial exception, the circuits of capital appear to be self-sustaining. The striking exception is labour power, whose reproduction requires, first, that the provision of wage goods is adequate for that purpose. Second, by virtue of the workers’ freedom once the working day is over (as well as their resistance on the shop floor and outside), capital has little control over the processes of reproduction of the workforce and, in a sense, this is where social reproduction takes over. The latter involves a complex array of non-economic relations, processes, structures, powers and conflicts that, interpreted in narrow terms, includes the processes necessary for the reproduction of the workforce both biologically and as compliant wage workers. More generally, social reproduction is concerned with how society as a whole is reproduced and transformed over time.

In short, and largely appropriately, social reproduction has become an umbrella term within which to gather all non-economic factors. It covers the entire ground between the abstract category of capital and the empirical reality of capitalism. But even this is only a partial understanding of the scope and significance of social reproduction. Capitalism clearly depends upon satisfactory economic as well as social reproduction, of which economic reproduction is a part. Misperception of the relationship between the two is commonplace, as if economic and social reproduction were separate from one another, like work and home. To a large extent, the inappropriate juxtaposition of the economic and the social (the latter as a political, cultural or any other kind of ‘superstructure’) is most marked in the disciplinary boundaries between the social sciences.

One of the most significant sites of social and economic reproduction is the state. Through the state are constituted and expressed political relations, processes and conflicts that are distinct from, but not independent of, those of economic reproduction. The extent to which the state is dependent upon the economy is highly controversial. Views range, to put it in somewhat one-dimensional terms, from those in which the state is reducible to economic, especially capitalist, imperatives, to those in which the state is seen as autonomous from the economy. The nature of the capitalist state will be taken up in Chapter 15, but the issues here of what has been termed reductionism, on the one hand, and autonomy, on the other, are of more general methodological, theoretical and empirical significance. The important point is to recognise both the causal significance of the capitalist economy for the non-economic – what sort of state, property law, customs, politics, and so on, prevail in each kind of society.

Similar considerations apply to those areas of social reproduction that lie outside the immediate orbit of the state, what is often referred to as ‘civil society’. Social reproduction also depends upon the household or family system and the more general areas of private activity, not least consumption and other activities of the working class that induce and enable it to present itself for work on a daily basis.

The emphasis so far has been upon the social reproduction of labour; but economic reproduction is equally dependent upon the formation and transformation of the conditions that enable the circuits of capital as a whole to be reproduced – not least the market and monetary and credit systems which require laws, regulations, and so on. These inevitably promote the interests of some capitalists at the expense of others, as well as preventing rivalry between capitalists from being unduly destructive. Such matters are equally the subject of politics, the state and civil society.

At the abstract level of this introductory exposition, only the conditions necessary for, and induced by, economic reproduction can be identified, along with the way in which economic and social reproduction are structured in relation to one another: how is the accumulation of capital accommodated socially and conflict over it contained? To progress further than this, it is necessary to introduce historical specificity, a task beyond the scope of this text.

As suggested in the previous chapter, Marx’s analysis in Volume 2 of Capital has been neglected and so has been relatively free of controversy. For further analysis of Volume 2, with some emphasis on the three different, but integrally related, circuits of capital (associated with money capital, productive capital and commodity capital) and with implications for economic ideology and crises, see Ben Fine (1975). The same cannot be said of social reproduction. This has been heavily debated, whether within Marxism or against it. Controversy covers the relationship between the economic and the non-economic (and how they do or do not depend upon one another), and the different aspects of the non-economic itself, from the nature of the autonomy of the state and politics to the role of ‘civil society’.

This chapter focuses on the material contained in Karl Marx (1978b, pt.3). The interpretation of social reproduction developed above draws upon Ben Fine (1992b, 2013), Ben Fine and Ellen Leopold (1993) and Ben Fine, Michael Heasman and Judith Wright (1996); see also John Weeks (1983). The value of labour power and the reproduction of the working class are discussed by Ben Fine (1998, 2002, 2003, 2012a), Ben Fine, Costas Lapavitsas and Alfredo Saad-Filho (2004), and Alfredo Saad-Filho (2002, ch.4); see also Kenneth Lapides (1998), Michael Lebowitz (2003a and 2009, ch.1) and David Spencer (2008), and Ben Fine’s debate with Michael Lebowitz in Fine (2008, 2009) and Lebowitz (2006, 2010).