The So-called Transformation Problem

In Volume 1 of Capital, Marx is concerned with the production of value and surplus value, and in Volume 2 with its circulation and exchange. A major part of Volume 3 deals with distributional relations as they arise out of the interaction of production with exchange. In his analysis, Marx focuses on the distribution across the economy of the surplus value produced by competing industrial capitals, including its appropriation, in part, by commercial and financial capital and the landowning class.

The starting point of Marx’s analysis of distribution is his argument that capitals of equal size generally produce different quantities of surplus value, because each capital employs a different quantity of value-producing labour. In spite of this, all capitals tend to enjoy equal rates of return, otherwise they would shift to more profitable areas of the economy. Marx explains the distribution of capital and labour across the economy, and the distribution of the surplus value produced by industrial capital (in the absence of other forms of capital), through the transformation of values into prices of production. At an even more concrete level of analysis, commercial and financial capitalists, and the landowners, capture in exchange part of the surplus value produced by industrial capital. Marx explains these processes through his analysis of commercial profit, interest and rent (covered here, respectively, in Chapters 11, 12 and 13).

From Values to Prices of Production

For the distribution of surplus value between industrial capitals in different sectors of the economy, Marx focuses initially on the tendency for the rate of profit to be equalised. The general rate of profit is r = S ⁄ (C + V), where the value quantities S, C and V are aggregates of surplus value and constant and variable capital for the economy as a whole. Marx argues that each industrial capitalist would share in the total surplus value produced according to their share in capital advanced, rather than simply appropriating the surplus value that they had themselves produced: it is as if each capitalist receives a dividend on an equity share in the economy as a whole. As a result, the profit share of the ith capitalist, whose advance of constant and variable capital is ci + vi, would be represented by r (ci + vi). For example, if the general profit rate is 50 per cent and the average capitalist, producing widgets, advances £100,000 (made up of variable and constant capital, including the depreciation of fixed capital), the firm’s annual profits would tend to be £50,000.

Corresponding to this would be a price of production for the commodity concerned, formed out of cost plus profit:

pi = ci + vi + r (ci + vi) = (ci + vi) (1 + r)

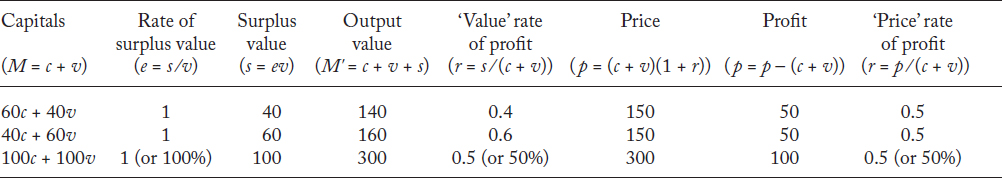

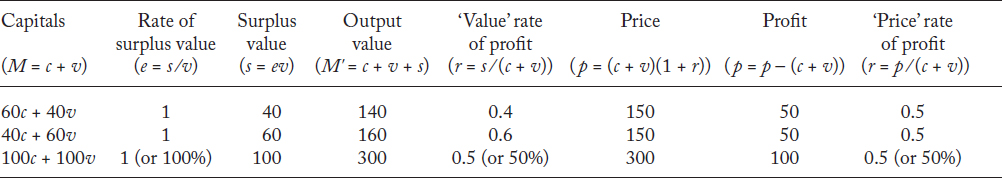

A simple example will illustrate this (see Table 10.1). Suppose there are only two capitals producing distinct goods, one of which uses 60c + 40v and the other 40c + 60v, with the rate of surplus value being 100 per cent. (Here we follow Marx’s notation in adding c, v or s after the quantities of value, 60 or 40, to indicate the value composition of the commodity.) In this case, the value of the output of the first capital will be 60c + 40v + 40s = 140, and the value of the output of the second capital will be 40c + 60v + 60s = 160.

This example raises a serious problem. For it implies that capitalists advancing equal sums of money but using distinct proportions of c and v would have different individual profit rates. In our example, the first capital reaps only r1 = 40 ⁄ (60 + 40) = 40 per cent, while the second capital enjoys a higher profit rate, r2 = 60 ⁄ (40 + 60) = 60 per cent. This is due to the difference in the composition of the advanced capitals, with a relatively higher proportion of variable capital leading to a higher profit rate. This should not be surprising. If only labour creates value (and, therefore, profit), while the means of production merely transfer their value to the output, the capital employing more labour produces more value and surplus value and, all else constant, has a higher profit rate.

Table 10.1 Marx’s transformation*

(*): The last row indicates totals or averages, where appropriate.

Capitals earning different profit rates will not coexist for long, given the possibility of migration across sectors. In other words, since each capitalist contributes equally in capital advanced (100), each must share equally in profit distributed (50 each). This can only come about if the prices of production are each 150. This is despite the differences in the values produced in the two sectors – the equalisation of profit rates between capitals in different sectors requires the transfer of (surplus) value across sectors of the economy, which is effected by differences between prices of production and commodity values.

Since capitals in different sectors will generally use distinct proportions of labour, raw materials and machinery to produce commodities, Marx draws the conclusion that outputs do not exchange at their values, but at prices of production. These prices of production differ from values, as the composition of capital, ci ⁄ vi, is greater or less than the average for the economy as a whole. (Note that for the first capital in Table 10.1, c ⁄ v = 3∕2 and, for the second, c ⁄ v = 2∕3, compared with an average of 1 for the economy as a whole.)

Marx’s Transformation and Its Critics

Marx’s explanation of the relationship between values and prices has been one of the most controversial aspects of his value theory. It has led some, even if otherwise sympathetic to Marxism, to reject the labour theory of value as irrelevant or even erroneous.

The reason for this reaction is that Marx’s solution to the transformation problem is perceived to be incorrect, and that the consequences of this presumed ‘error’ are, supposedly, far-reaching. The crux of the critique is the following: Marx has shown that, when capitals compete across sectors (and migration of capital can occur from one sector to another), commodities no longer exchange at prices equal to their values. This leads both to the empirical objection that values are irrelevant, since they do not drive actual exchanges, and to the logical critique that, in Volume 3, Marx has continued to evaluate the inputs, c and v (and the ‘value’ rate of profit, used in the calculation of the prices of production), as if they were values, rather than prices. In other words, it is as if, for the critics, Marx presumes that commodities are purchased ‘at values’ (respectively, 140 and 160), but are sold ‘at prices’ (150 and 150) – which is inconsistent, since selling and buying prices must be the same.

For the problem of translating given values into prices of production in an economy in equilibrium, this would be a deficiency, but one of which Marx was fully aware and which can be corrected easily. It is merely a matter of transforming the inputs as well as the outputs simultaneously through a simple algebraic procedure. The implication of this ‘correction’ is straightforward: commodities have values as well as prices, and two distinct accounting systems (not necessarily equally significant, either in theory or in practice) are possible. One of these accounting systems expresses the socially necessary labour time required to produce each commodity, and the other the quantity of money which, in general, the commodity would fetch upon sale.

More significant than the algebraic ‘solution’ of the transformation ‘problem’ is the observation that Marx’s labour theory of value cannot founder on such quantitative conundrums, as the search for a corrected algebraic solution seems to imply. Crucially, Marx has shown that values exist as a consequence of the social relations between producers, and that price formation translates the conditions of production into exchange relations. Because they exist (rather than being merely a construct of the imagination), values cannot be challenged or rejected according to algebraic interpretations of Marx’s theory. Rather, the real relationship between values and prices has to be recognised theoretically and explored analytically – for example, why do the dominant relations of production give rise to the value form, how do values appear as prices in practice and change over time, and how do tensions between values and prices contribute to economic crises?

In this light, it is significant that the literature on the transformation problem traditionally focuses on the implications of differences in the value composition of capital (VCC) across different sectors in the economy – as if c and v in Table 10.1 were quantities of money, with 140 and 160 being the ‘original’ prices of the unit of output, and 150 the unit prices ‘modified by competition’.

This is not the case for Marx. In Volume 3, Marx considers the transformation entirely in terms of the organic composition of capital (OCC) which, as was shown in Chapter 8, is only concerned with the effects of the differing rates at which raw materials are transformed into outputs (in contrast, the differing values of the inputs are captured by the VCC). As such, Marx is less concerned with how the inputs (c and v) originally obtained their prices, and more concerned with how differing OCCs, or differing rates of productivity across sectors, influence the formation of prices and profits.

Marx’s problem is the following. If a given amount of living labour in one sector (employed through the advance of variable capital v) works up a greater quantity of raw materials, represented by c (regardless of its cost) than in another sector, the commodities produced will command a higher price relative to value, as previously discussed and numerically illustrated in Table 10.1. In other words, the use of a greater quantity of labour in production will create more value and more surplus value than a lesser quantity – regardless of the sector, the use value being produced, and the cost of the raw materials. This is a completely general proposition within value theory, and it underpins Marx’s explanation of the existence of prices and profit. Marx’s use of the OCC rather than the VCC in his transformation is significant because the OCC connects the rate of profit with the sphere of production, where living labour produces value and surplus value. In contrast, the VCC links the profit rate with the sphere of exchange, where commodities are traded and where the newly established values measure the rate of capital accumulation.

His emphasis on the OCC shows that Marx is primarily concerned with the effect on prices of the different (surplus-) value-creating capacity of the advanced capitals, or the impact on prices of the different quantities of labour necessary to transform the means of production into the output – regardless of the value of the means of production being used as raw materials. The use of the OCC in the analysis of profit creation and distribution is important, because it pins the source of surplus value and profit firmly down to unpaid labour. This helps Marx to substantiate his claims that machines do not create value, that surplus value and profit are not due to unequal exchange, and that industrial profit, interest and rent are shares of the surplus value produced by the productive wage workers.

In his transformation of values into prices of production, Marx is not dealing with equilibrium price theory (as in mainstream economics and in many conventional interpretations of the labour theory of value), but with the relationship between differences or changes in production and price formation. This acts in Volume 3 as a prelude to the treatment of the law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall (LTRPF) (although the order of presentation is reversed in this book). Finally, the transformation problem and the LTRPF have generally been considered as two separate problems (although an author’s stance on each has often been read as a commitment for or against Marx’s value theory more generally). However, in this chapter and the previous one, through the consistent use of the OCC as distinguished from the VCC, it has been found that the two problems are closely related to each other. They are both concerned with the tensions created by the integration of production with exchange and, especially, with the consequences of differences or changes in conditions of production for price formation in particular and movements in exchange more generally.

It is remarkable how, even among those sympathetic to Marx, the transformation of values into prices of production has floated free from other ‘problems’ in Marx’s political economy to become a debate over (equilibrium) price formation. Not surprisingly, the literature on the transformation problem is vast. The original treatment is presented in Marx (1981a, pts 1–2). The interpretation of the transformation in this chapter was pioneered by Ben Fine (1983a), and it is explained and developed further by Alfredo Saad-Filho (1997b; 2002, ch.7). Several alternative approaches are available; for an overview, see Simon Mohun (1995) and Alfredo Saad-Filho (2002, ch.2). Sraffian analyses, rejecting value theory as irrelevant and/or erroneous, are concisely presented in Ian Steedman (1977) – for critiques, see the papers in Ben Fine (1986) and Bob Rowthorn (1980), as well as Anwar Shaikh (1981, 1982). Gérard Duménil (1980) and Duncan Foley (1982) have proposed a ‘new interpretation’ of the problem, focusing on the value of money as a means of resolving Marx’s supposed conundrums. This is critically reviewed by Ben Fine, Costas Lapavitsas and Alfredo Saad-Filho (2004) and Alfredo Saad-Filho (1996). More recent debates about the nature and definition of value, with direct implications for the transformation problem, can be found in the journals Cambridge Journal of Economics, Capital & Class, Historical Materialism and Science & Society. Again, Moseley (2015) offers his own original interpretation.