4

The Aqueduct

The last decades of the nineteenth century and the first of the twentieth were a critical period for the development of civic infrastructure across North America, or as one participant later described it, the “awakening of the municipal conscience.”1 It is impossible to separate this process of civic building from the context of western Canadian colonialism within which it occurred. As historian James Daschuk has shown, the turn of the century witnessed the radical dispossession of prairie Indigenous people through outright military action, radical ecological change, and a complicated and devastating campaign of food politics.2 As Cree, Metis, and Anishinaabe people were in different ways put down, eliminated, or relocated, urban growth was cultivated and celebrated as a particular manifestation of colonial and capitalist success. Alan Artibise’s book-length study of urban development in Winnipeg documents a local elite deeply enamoured with Winnipeg’s possible future as a site of liberal capitalist development, and well aware that municipal infrastructure was a necessary predicate for this new, ambitious wealth.

In 1906 Manitoba’s provincial legislature established a Water Supply Commission mandated to find an adequate water supply for Winnipeg.3 Fairly soon they returned to an idea that had been floated at least since the mid-1880s:4 that water be diverted from the Lake of the Woods drainage basin to Winnipeg. In September of that year, the city’s Water Commission visited Shoal Lake and discursively transformed it into a solution to Winnipeg’s problems. The Manitoba Free Press called Shoal Lake an “Immense Reservoir of Pure Water,” one that could be transmitted to Winnipeg, albeit at a steep cost. In making this assessment, the newspaper noted but minimized the presence of Shoal Lake’s Indigenous and settler inhabitants: “There is practically no habitation with the exception of a few Indians and an odd mining camp.”5

Here is the classic language of settler colonialism, minimizing and even denying outright the presence of Indigenous people. These are not innocent manoeuvers. By declaring Indigenous people to be few, none, or of no real consequence and land to be uninhabited or pristine, narratives like these separate Indigenous people from their lands and resources, or at least the ones that settlers might want, in this case the precious commodity of clean drinking water. A variation on this rhetorical move was routinely enacted throughout the colonial world, and to particular effect in the Antipodes and North America. The language of colonial erasure was flexible and persisted even when Indigenous presence, the lived reality of Indigenous persistence, proved it wrong.

The language of Indigenous absence persisted in the face of an obvious and enduring Indigenous presence at Shoal Lake. Located in Lake of the Woods, Shoal Lake was in the centre of a vibrant Indigenous world that had connected people from around the continent for thousands and thousands of years. The Anishinaabe of Shoal Lake and neighbouring areas lived in an environment rich in white fish, in animals that supplied meat and furs for use and trade, and in manoomin, or wild rice. Shoal Lake people had been partners in the European fur trade for centuries and did wage-labour in the industries—gold mining, transportation, and other areas—that had developed in the last half of the nineteenth century. For much of the nineteenth century, agricultural production among the Anishinaabe of the region increased in step with the general population.6 Shoal Lake Anishinaabe were among the tough treaty negotiators who held Canada to account in negotiating the third of Canada’s number treaties, concluded in 1873.7

Settler rhetoric about human scarcity or absence around Shoal Lake continued in the face of persistent and—within the context of early twentieth-century northwestern Ontario—demographically significant communities at Shoal Lake. The same year that the Winnipeg press reported that there were only “a few Indians,” the Indian Agent reported that there was a population of 134 in the communities of Shoal Lake 39 and Shoal Lake 40. “Hunting, fishing, berry and wild rice picking, working for the fish companies and lumber camps are the principal occupations of the band,” the agent explained about Shoal Lake 40, adding that “some of them have very nice gardens, with good results.”8 In 1914, the agent wrote that the fifty-nine people at Shoal Lake 39 and the eighty-three at Shoal Lake 40 lived in log homes that were “well built, of fair size, with good shingled roofs, well furnished and ventilated, and clean.”9 The township of Kenora had a reported population of 844 in 1912, indicating the relative local significance of Shoal Lake’s size.10

The communities of Lake of the Woods were relatively well resourced and certainly resourceful in the face of the enormously complicated circumstances faced by Indigenous people in western Canada at the turn of century. This included residential schooling, a critical component of the Canadian state’s efforts to regulate and transform Indigenous peoples that took on new authority and power in the 1880s.

The Presbyterian Church of Canada built the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School at Shoal Lake in 1901.11 Historian Victoria Freeman shows how in 1902, Shoal Lake 40 Chiefs Redsky and Pagindawind negotiated an unusual and important agreement with the school’s administers, making them agree to a long list of revealing conditions: that young children should not be baptized without their parents’ consent; that children not be transferred without their parents’ consent; that children under eight years of age not be given heavy labour; that older children were to attend school at least half the day; that children could share in whatever profits the school might receive from farm produce; that parents be allowed to take children to Anishinaabe ceremonies; that older children would get at least three weeks’ holiday for berry picking or manoomin harvest; that children be allowed to visit sick kin; and that police not be used to retrieve children who left the school.12

The long histories, active and complicated presents, and possible futures of Shoal Lake’s Anishinaabe communities received little and sometimes no mention in the discussions that identified Shoal Lake as a source of good, plentiful drinking water for Winnipeg. The city decided on Shoal Lake after considering a range of other options. The artesian wells provided water that tested as safe, but it was hard and always in short supply. They considered the Winnipeg River and Poplar Springs. By 1912 the idea of building an aqueduct from Shoal Lake had picked up traction. The advice of another hired American expert, in this case engineer Charles Slichter, was again given special weight. In 1912, one local official explained that Slichter’s advice was that of “a widely travelled gentlemen of keen observation and mature judgement.” Slichter argued that building an expensive and ambitious aqueduct was justified, since “A perfect water supply is worth all it costs.”13

![Black and white image of a small two-tiered steamboat moored at a dock with an expanse of water behind. Eleven people are seen standing in the boat, many of them Annishinaabe children. Five men stand beside the boat on the dock in the foreground. Some white text appears at the top and bottom of the image. At top left: May 26th, 1914. At bottom only part of the text is legible: “W.W.D [..] Bay – Steamer Wondere[..]Indian school Children.”](../Images/3_children_on_boat_to_school.jpg)

Children on their way to the Cecilia Jeffrey Residential School, located near the Shoal Lake 40 reserve from 1901 to 1929, photographed in November 1914. Published with permission of Shoal Lake 40 First Nation, the City of Winnipeg Water and Waste Department, and the City of Winnipeg Archives. GWWD photograph 36.

Consolidation of support for the Aqueduct was closely tied to the leadership of Thomas Russ Deacon. Deacon was one of a number of Ontario-born white men who rose to prominence in the rapidly changing political space of early twentieth-century Winnipeg. He also represented the connections between Winnipeg’s commercial elite and northwestern Ontario as a kind of capitalist resource frontier, and the close and indivisible ties between private industry and civic government. Deacon was a surveyor on Lake of the Woods and Shoal Lake, a councillor in the town of Kenora, and Managing Director of the Mikado Gold Mine in Shoal Lake. He moved to Winnipeg and founded Manitoba Bridge and Iron. These connections were legible and noted at the time. In 1916 a journalist explained to a wide Canadian audience that Deacon was a “former city engineer, mining engineer, and superintendent of construction on the North Bay waterworks; a man that had a great deal to do with bridge and iron and other industrial matters, had a summer home somewhere on the Lake of the Woods.”14

In 1906 Deacon was elected to city council, and in that same year the province agreed to incorporate the Greater Winnipeg Water District (GWWD), forming a kind of consortium between Winnipeg and what were then the separate municipalities of Transcona, St. Vital, and St. Boniface.15 In 1913, Winnipeg elected Deacon mayor on what amounted to a Shoal Lake water ticket. Within a fairly short time he had come up with a plan to finance the ambitious scheme that sceptics had long decried as implausibly expensive.16 “The Mayor was elected frankly on a Shoal-Lake-water platform,” explained the Manitoba Free Press, “and he is now delivering the goods.”17 Twice in 1913 those eligible to vote as city taxpayers—overwhelmingly property-owning white men—voted on the plan. In October 1913, a vote of 2,951 in support and 90 against approved the creation of a debt of thirteen and a half million dollars to build the Shoal Lake Aqueduct.18 In 2015 values, this is a little over 281 million Canadian dollars. The final parts of the Aqueduct plan would be administered by another anti-labour mayor, R.D. Waugh.19

Anishinaabe community and GWWD staff, Shoal Lake 40, June 1914. Published with permission of Shoal Lake 40 First Nation, the City of Winnipeg Water and Waste Department, and the City of Winnipeg Archives. GWWD photograph 22.

Published discussions of Shoal Lake as a potential source of Winnipeg’s water framed the issue as an arena of white, male, and largely professional knowledge, and saw the water as a commodity that might be learned about, managed, and possessed. As support and resources for the Aqueduct were marshalled, the Indigenous people at its source retreated further from settlers’ view. That Shoal Lake was more or less uninhabited and axiomatically pristine became an accepted sort of truth, one that didn’t even need to be said very often. A 1913 article in The Western Home Monthly described the Cecilia Jeffrey school and made note of “a number of Indian camps and shacks” at Indian Bay.20 This article, complete with highly racialized descriptions, was the exception rather than the rule. Engineers explained that “the entire region for miles around is uninhabited.”21 Four decades later, these descriptions had changed very little. “The shores of the Lake of the Woods are virtually uninhabited,” wrote the GWWD’s Assistant General Manager in 1955.22

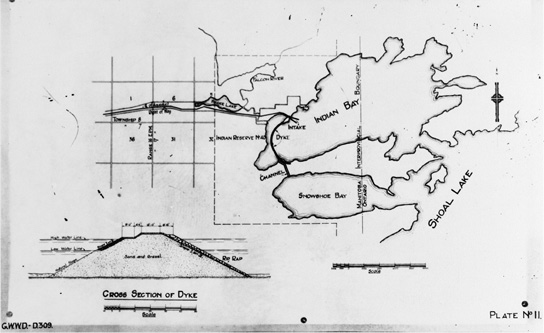

Map of the Aqueduct and cross-section of the dyke. City of Winnipeg Water and Waste Department and the City of Winnipeg Archives. GWWD Misc. Images, Plate 11, CD R74.

Such language strategically and self-servingly ignored the Indigenous presence at Shoal Lake and actively masked the Indigenous knowledge and resources upon which Deacon and no doubt others depended. In 1975 Deacon’s son wrote a letter to the editor, explaining that it was his father’s “Indian companion” who first identified Shoal Lake in 1901.23 Alfred Deacon explained:

While practicing as an engineer and Ontario Land Surveyor in Kenora, 1892-1902, he [Thomas Deacon] put in Kenora’s first water system. He was also manager of the Mikado Gold Mine on Shoal Lake. One fall while timber-cruising in Indian Bay for fuel for the steam-operated mine, his Indian companion showed him a stream running east into Indian Bay: a mile or so upstream the Indian pointed out that the water was running in an opposite direction, west, away from Shoal Lake.24

In archival fragments like these the Indigenous history of the Aqueduct surfaces, awkwardly disrupting the settler celebration and Indigenous erasure that undergirds the planning and building of the Aqueduct.

Deacon’s “Indian companion” is part of the story of the Aqueduct, and so is the residential school that was located at Shoal Lake from 1901 to 1929. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Final Report documents how the late 1910s were difficult years at the Cecilia Jeffrey Residential School, marked by epidemic illness and persistent concerns about abusive staff.25 The school was also a resource for the GWWD and its staff. In 1913, the GWWD created a small “laboratory” at Cecilia Jeffrey.26 The GWWD paid chemist C.W. Aitken four dollars a day to test water samples. The GWWD paid another ten dollars per week to the Residential School for Aitken’s room and board and use of rooms for the laboratory.27 When Winnipeg’s city council toured Shoal Lake in 1913, they paid a visit to “the Indian Industrial School at the entrance to Snowshoe Bay,” and the main thing they reported was that “a chemist is hard at work in a well-equipped laboratory testing Shoal Lake water.”28 The colonialism of water met the colonialism of residential schooling in intimate terms and at close and dependent proximity.

Chief Pete Redsky, November 1913. Published with permission of Shoal Lake 40 First Nation, the City of Winnipeg Water and Waste Department, and the City of Winnipeg Archives. GWWD photograph 2.

Photographs taken by the GWWD further complicate the image of a land without people. Photographs show Anishinaabe children boarding the boat to go to residential school. They show Anishinaabe men working. A photograph of Chief Pete Redsky is taken at close distance. This is not a photograph taken by a stranger of an Indigenous person stripped of their individuality through anonymity, but a relative intimate or at the least an acquaintance that knew and recorded the name of their subject.

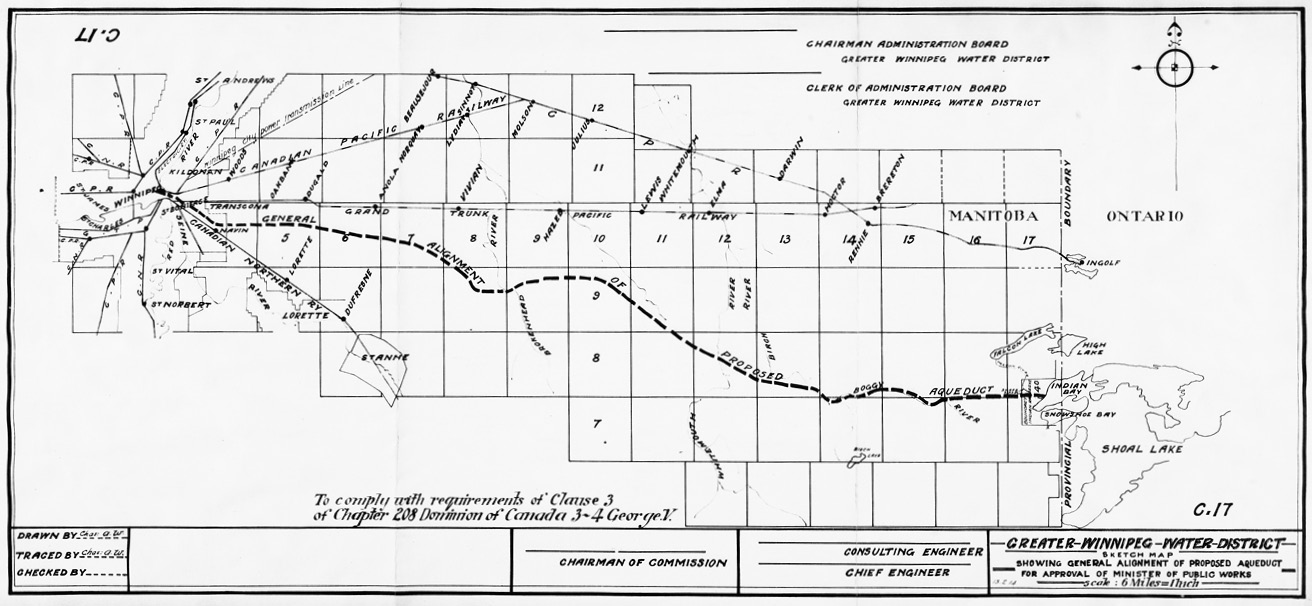

The building of the Aqueduct required the coordination and agreement of multiple levels and manifestations of the North American state. Under the British North America Act, Manitoba at this point lacked authority over its resources, but the federal government granted permission for the waters of Shoal Lake to be diverted in 1913. Ontario’s permission was granted with stipulations a little later.29 This was not simply a Canadian matter. Lake of the Woods was defined as an international body of water, so the diversion of its waters to the city of Winnipeg required the permission of the International Joint Commission. After serious deliberation, the Commission approved the project in 1914.30

The power of the federal government over Indigenous people and Indigenous lands is a critical part of the story of the building of the Winnipeg Aqueduct. The British North America Act of 1867 gave the federal government control over “Indian affairs,” including lands reserved for Indigenous people. Scholar David Ennis explains that almost all the land required for the intake—Indian Bay, Snowshoe Bay, and the adjacent shorelines—were located on Shoal Lake 40’s reserve.31 The Indian Act—a sweeping piece of legislation first passed in 1876, regularly revised thereafter, and still in effect today—included a couple of mechanisms whereby First Nations could lose their legal rights to reserve lands. In the years of rapid settler expansion in western Canada, these mechanisms, especially that of surrender, would be used routinely. In the fifteen years between 1896 and 1911, a remarkable twenty-one per cent of lands reserved for prairie First Nations were surrendered.32

The GWWD took the lands and resources reserved for Shoal Lake 40 through at least three distinct legal processes, each provided for and codified by federal legislation. It began in the fall of 1913, when the GWWD’s lawyer simply made a written request to the Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) for permission to set up camp and do preliminary surveys on the Shoal Lake 40 reserve. The DIA granted this without charge and with no evidence of having consulted Shoal Lake 40, asking only that the GWWD pay for any damages that might occur.33 The genial, mutually supportive relationship between the DIA and the GWWD was thus established. Canada’s deferential accommodation of Winnipeg’s interests over those of Shoal Lake 40 continued through the building and the operation of the Aqueduct.

Sketch map of the Aqueduct’s proposed route, 1913. City of Winnipeg Archives, A1381, File 58.

The next legal mechanism that separated the people of Shoal Lake 40 from their lands and rights in the interests of the Aqueduct was the one that was most often employed to transfer territories and resources from First Nations to settlers: surrender. Soon after the setting up of the GWWD’s survey camp, Chief Redsky negotiated a deal with one of the GWWD’s more enterprising early contractors to sell him gravel and sand for a royalty of $30 and 3 cents per cubic yard.34 The DIA intervened and explained that Shoal Lake 40 could not sell any gravel and sand unless they surrendered their rights to it. The DIA initiated a surrender process, and the surrender of Shoal Lake 40’s rights to the sand and gravel on their reserve was completed in January 1914.35

Here was early twentieth-century settler colonialism in all its caprice, preventing Indigenous people from acting as economic agents in ways that mainstream twentieth-century Canada considered routine and even admirable. During the same time frame that the surrender of Shoal Lake 40’s rights to their gravel and sand were surrendered, the local Indian Agent negotiated another deal with the same contractor that would have delivered two cents more per cubic yard than he had agreed to pay Chief Redsky. The contractor also promised to hire “all Indians wanting to work,” something that the agent thought “will be a great benefit to them.”36 Redsky continued to look for economic opportunities and made inquiries about the sketchy legal processes at play around him. In December 1913 Redsky wrote to the DIA, asking “Has the Greater Winnipeg Water District made any arrangement about occupying any part of the reserve or about taking sand, gravel, or timber from it?”37 But Redsky and, in a very different way, the local Indian Agent had both run up hard against a Canadian state willing to avail itself of a range of legal mechanisms for dispossessing Indigenous people of their resources and lands at the least possible cost.

The dispossession of Shoal Lake 40’s rights to their gravel and sand paled to the ultimate form of taking authorized by the Indian Act, one that would have particularly enduring consequences. In February 1914 Duncan Campbell Scott, famous for being both a sad ethnographic poet and Deputy Secretary of Indian Affairs, wrote to the GWWD politely reminding them where the authority over reserve lands lay: “I have to request that you will kindly advise the Department fully as to your plans in connection with carrying on operations on this reserve, as you are aware no rights can be granted without the consent of the Indians.”38 Here Scott seems to presume that Shoal Lake 40 would be asked to make a formal surrender of their lands requested by the GWWD. So, it seems, did both the community and the local Indian Agent. In February of 1914 the Agent, R.S. McKenzie, noted that the GWWD was eyeing “quite a large piece of the corner of the reserve” and claimed that Shoal Lake 40 was interested in a surrender process.39

But the legal mechanism that would ultimately be employed to strip Shoal Lake 40 of its rights to a significant part of its reserve would not require even the nominal, easily manipulated, strictly patriarchal, and brittle sort of consent of the DIA’s surrender process. The GWWD made clear that it wanted the land and was prepared to cash in the political chips necessary to secure it. In January 1914 the GWWD’s chair wrote that Deacon would be travelling to Ottawa to “personally explain to you our position” and “indicate to you just what our desires are in this respect.”40

A month later Deacon wrote as both mayor of Winnipeg and chair of the GWWD, requesting permission to purchase Shoal Lake 40’s reserve land. “We recognize that the Indians are entitled to reasonable compensation for this and we are prepared to pay what the Department would think just,” Deacon acknowledged, adding that he hoped “title could be arranged” in the coming summer.41 The DIA replied that the land could be acquired through Section 46 of the Indian Act, making surrender wholly unnecessary.42 This section laid out a process by which reserve lands might be taken for “any railway, road, public work, or work designed for any public utility” without the consent or approval of the First Nation.43

The deal for Shoal Lake 40’s reserve lands was brokered when mayor Deacon personally travelled to Ottawa to meet with Scott in March of 1914. They would spend the next months haggling over certain specifics by letter. Deacon complained about a “much higher” rate for reserve lands than for Crown lands, making clear that he regarded the two kinds of land as more or less the same, presumably available for settlers with nominal costs and process. Deacon balked at the suggestion that the city should have to pay for gravel and sand at all.44 Scott, acting on behalf of the DIA, quickly caved in the face of the mayor’s disagreement and sent a telegram to Winnipeg confirming that “the price is to be $3.00 per acre to cover everything.”45 Earlier agreements, including the one made by the DIA, were put aside in the interests of satisfying the settler city. Deacon agreed to pay something for the lakebed of Indian Bay with some reluctance, not having considered it part of the reserve.46

In June of 1914 the city of Winnipeg paid the federal government $1,500 for approximately 3,000 acres of Shoal Lake 40’s reserve, which translates to a little over $31,000 in 2015 values.47 The sum of $1,500 was arrived at by calculating three dollars an acre for 355 acres of Shoal Lake 40’s land and fifty cents an acre for lakebed and islands.48 The paperwork was shuffled to a law clerk in Ottawa, who agreed in December of 1914 that the GWWD had “the requisite statutory authority referred to by Sec 46 of the Indian Act as amended by SL Ch 14 1-2 for taking and using land without consent of the owner.”49 In March of 1915, the representative of the British Crown in Canada, the Governor General, added his approval.50 At some point an additional amount was paid, and, when pressured by Shoal Lake 40 early in 1919 to account for how their lands had been disposed of, the DIA would report that the GWWD had paid the $1,500 for land covered by water and $1,065 for reserve lands, making a total of $2,565.51

The especially critical dispossession of land and lakebed for the Aqueduct intake was carried out without the consent of Shoal Lake 40 and, it seems, with little or no knowledge of the local Indian Agent. Soon after the money passed hands between Winnipeg and Ottawa, R.S. McKenzie, Indian Agent for the Kenora district, reported that the people of Shoal Lake “were very much excited about the work of the Greater Winnipeg Water Works, and requested me to tell them what right they had to operate on their Reserve, and demanded to know what they were to get for the land taken, and what quantity is taken from them.” McKenzie did not know how to answer.52 The Secretary of the DIA, J.D. McLean, responded with some blueprints, a reiteration of the GWWD’s statutory authority to dispossess Shoal Lake 40’s lands, and an unconvincing promise to guard Indigenous rights, writing that “The Corporation of the city of Winnipeg has the power to expropriate the lands required, but you may assure the Indians that their rights will be safeguarded by the Department.”53 A few years later they would clarify that this included the sand and gravel used to build the diversion dyke and Aqueduct, and that they were not bound by the earlier agreement to pay anything at all for those resources.54

The colonial archive records these transactions in dispassionate, administrative language. At no time did the GWWD seem to consider that their request for reserve land might be denied. In February of 1914 McKenzie summed it up, noting that “sooner or later they will be given the privelage [sic] asked for.”55 The DIA sometimes showed frustration with the GWWD’s slow responses, but on the whole, DIA archives suggest a federal government committed to helping Winnipeg, even when doing so involved sacrificing the interests of the Indigenous communities they had a political obligation to represent. This means that the negotiations around the 1914 land loss were conducted by federal officials committed to helping Winnipeg get what it wanted. Scott explained that the question was “how we can effectively grant you the bed of that portion of Indian Bay situated in the province of Manitoba” and declared that he was “quite disposed to deal favourably with this proposition if the Department has the power to act in the matter at all.”56

The building of the Aqueduct was an enormously expensive enterprise, and one celebrated for being so. But in his correspondence with the DIA, Deacon was miserly, tight-fisted, and reticent to see Indigenous lands and resources as worthy of anything more than the most symbolic of payments. In 1914 Deacon explained why he didn’t want to pay for gravel and sand, arguing that the Shoal Lake 40 reserve was “such a remote place and is only to be reached by our line,” which Deacon promoted as “purely…a public service work.”57 Here, the only meaningful value of the land lay in the capacity of settlers to reach and use it. In the municipal archives, the records that document the sale of Indigenous land appear as routine matters of business, alongside, say, purchases of pipe. At Shoal Lake 40 in 1918, Chief Redsky described the land loss of 1914 as enormous, consequential, and deeply unfair. Redsky explained that the land taken by the GWWD was “the best part of our Reserve,” adding that it is “very good farming, good timber, good hay land.”58

The dispossession of Shoal Lake 40 in 1914 was one especially powerful chapter in a much wider pattern of Indigenous land loss in the years of Canadian nation building and expansion. The Department of Indian Affairs’ annual report for 1915 catalogued all the Indian lands sold, and there, on the “Indian Land Statement,” Shoal Lake 40—with a loss of 3,737.89 acres—is one of a long list of Indigenous people who lost their land in the previous year.59 Loss of reserve lands had been swift in the years of rapid western expansion and continued during the Great War. As historian Sarah Carter explains, the political alliances and languages of the Great War only reinforced ongoing pressure on Indigenous communities in western Canada to surrender their reserve lands.60

Shoal Lake 40’s land loss was part of broad patterns, but the precise mechanism of the 1914 dispossession was unusual. Section 46 of the Indian Act was introduced in 1911, one of the amendments that represented the federal government’s “acceding to the demands of those who coveted Indian Land,” as historian Brian Titley explains.61 But Section 46 of the Indian Act was not used very often,62 and its role in the dispossession of Shoal Lake 40 should give us pause. Given the extensive use of the surrender process in these years, including in Shoal Lake 40, and early discussion of a surrender process, why did the DIA and the GWWD pass over this well-worn mechanism? What resistance to the GWWD’s designs might have been anticipated? How much political capital was Winnipeg willing to put into the effort to dispossess Shoal Lake 40 in the interests of the Aqueduct, and how willing and able was the federal government to facilitate that?

Construction of the Aqueduct began in 1914. The GWWD was concerned with the fact that what they called “dark” or humus-rich water drained into Shoal Lake from Falcon River and Snake Lake. The GWWD had a costly and politically touchy project to sell to the taxpayers of Winnipeg, and delivering “dark” water would not help convince those taxpayers that this solution to Winnipeg’s ongoing water woes was worth it. There were two apparent ways to separate this less desirable “dark” water from the clearer drinking water destined for Winnipeg. One was to build a five-mile extension of the Aqueduct, which would have cost about one million dollars. The other was to build a dyke, which was estimated at around $147,000 and was therefore the much less expensive choice.63

Chief Engineer W.G. Chance stands in the arch of the Aqueduct, still very much in construction at mile 43, probably October 1914. Published with permission of the Greater Winnipeg Water District and the City of Winnipeg Archives. GWWD photograph 264.

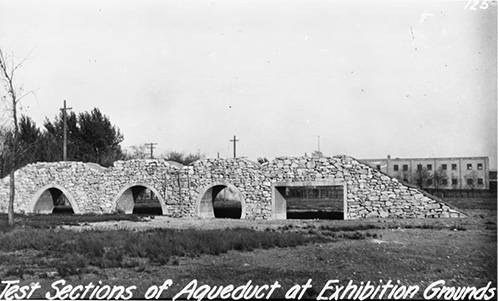

Test sections of the Aqueduct on display at Winnipeg’s annual Fair and Exhibition, undated. Published with permission of the City of Winnipeg Water and Waste Department and the City of Winnipeg Archives. GWWD photograph 125.

The GWWD chose the cheaper option, creating remarkable and enduring consequences for Shoal Lake 40. In 1914 the GWWD began “preparatory work” on the Aqueduct, which included the earth-filled dyke intended as a guiding wall to divert the flow of the Falcon River along the west end of Indian Bay and into a canal.64 The men who wrote about the diversion project in American scientific and engineering journals didn’t generally mention it, but this also worked to effectively maroon the community of Shoal Lake 40, leaving it on what became, in effect, an artificial island.

The building of the Aqueduct was expensive, ambitious, closely watched, and widely celebrated. Those engaged with the Aqueduct’s construction understood the project as historic, meaningful, and worthy of its considerable costs. They thought the Aqueduct told important truths about themselves and the particular settler society they lived in and championed. In 1919 a city engineer explained that the building of the Aqueduct was “typical of western ambition and energy.”65 The Aqueduct spoke to particularly western Canadian virtues on a global scale. The Toronto press reported that “The completion of the aqueduct will make it rank probably only second on the continent with undertakings of this nature.”66

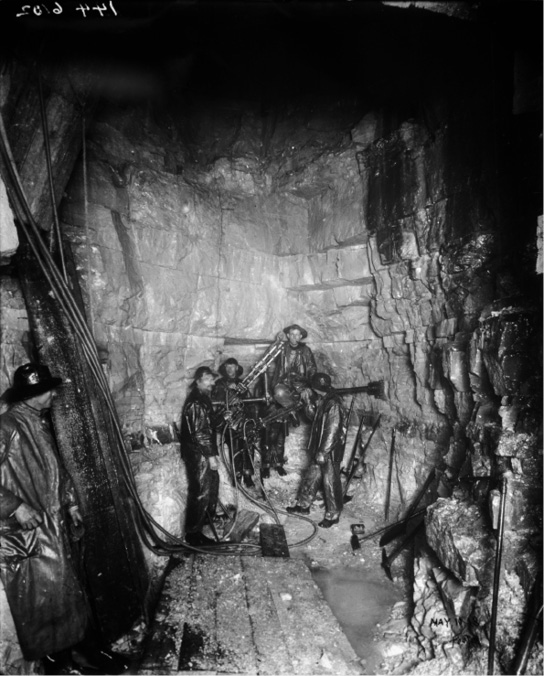

The building of the Aqueduct was predicated on two technologies that traversed space and time and linked people and places in new ways, at least for this corner of northern North America. One was the telephone. A telephone wire was laid along the length of the Aqueduct. The other and more important technology was the railway that was purposely built for the Aqueduct. It had 111 miles of track, six locomotives, twenty flatcars, and ten boxcars.67 According to the chief engineer, W.G. Chase, the building of the GWWD railroad was “a sine qua non of the successful building of the aqueduct.” The building of the railroad was a matter of overt colonial symbolism and practical expediency. “The country traversed was virgin land between miles 40 and 96 and nearly altogether swamp covered,” Chase explained. “[R]ailway transport was recognized immediately as the key to rapid construction of the aqueduct.”68

The railroad and telephone line were each powerful symbols and crucial material ingredients in colonial modernity and capitalist ambition in early twentieth-century western North America. Railroads carried Canadian troops to put down the Metis and their allies who took up arms in the Northwest in 1885. Railroads carried settlers into western Canada, and wheat and coal away from it. Railroads were messy and political in the last decades of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth. The railroad that came with the Aqueduct made clear the ways in which this project of empire was tied to so many others.

Railroads were built and laid by people, and so was the Aqueduct itself. The construction process required an enormous amount of human labour. The organization of the construction of the Aqueduct was a huge feat, especially after Canada entered World War One as part of the British Empire. The building of the Aqueduct and World War One would almost entirely coincide, and the commitment of the GWWD and its supporters in both provincial and federal governments to this mega-project during the financial insurgencies and labour shortages that marked the war is notable.

![Black and white photograph taken at some distance of a group of Annishinabe men working in a forest; at the centre two workers seem to be cutting down a tree with a long saw while seven other workers stand close by. White script at bottom: G.W.W.D. Falcon River Dyke – Pete Redsky, Indians Clearing [illegible].](../Images/8_men_at_work_SL40.jpg)

Men from Shoal Lake 40 at labour, June 1914. Published with permission of Shoal Lake 40 First Nation, the Greater Winnipeg Water District, and the City of Winnipeg Archives. GWWD photograph 39.

Some of this labour was Indigenous labour. Photographs document Anishinaabe men working at the intake during the Aqueduct’s early stages. But most of the work—laying track, digging trenches, pouring concrete, tunneling—was done by the same people who were the critical labour force for most of the projects of early twentieth-century western Canada: young, mobile, and migrant men, disproportionately European. At one point there were 2,000 men working on the Aqueduct. The scope of the project meant that these men moved into Indigenous territories and lived in camps severed from usual patterns of sociability. What oil and gas industry observers now call “man-camps” were and continue to be an example of how gender, race, and class collide in extractive resource economies. In 1915, there were eleven work camps associated with the Aqueduct; in 1916, there were fourteen camps; in 1918, twenty-two.69

In the documents that describe the building of the Aqueduct, it is the men who did the difficult work of building who are the most legible objects of human concern. The first decades of the twentieth century were years of labour protest and radicalism in Winnipeg and western Canada as a whole. Labour conditions were a political matter. The GWWD required that their subcontractors follow a “fair wage schedule,” and provide working men with what they called “good board and lodging” at the cost of five dollars per week.70 Working people did not always find these conditions appealing, especially when the wartime economy produced other options. By 1916 a journalist could write that “at present the big trouble with the aqueduct is lack of labour.”71

The building of the Aqueduct was closely observed and monitored. Early in 1916 there was a concern that the cement would not hold, and some civic politicians argued that the Aqueduct plan should be scrapped.72 But work continued. In May of 1918 Winnipeg’s labour newspaper, The Voice, let its readers know that the GWWD was holding a “public excursion” on Victoria Day, that particularly imperial holiday. For a dollar, people could travel by GWWD rail to “the terminus of the aqueduct pipe line,” and have an opportunity to view camps “now in full operation” and “the work being done.”73

![Black and white photograph of a small cluster of white tents and buildings surrounded by trees, and a dirt road in the foreground. White script at upper left: June 17th, 1914; at bottom: G.W.W.D. Falcon River Diversion – Contractors [sic] Camp.](../Images/10_man_camp.jpg)

A GWWD construction camp, June 1914. Published with permission of the Greater Winnipeg Water District and the City of Winnipeg Archives. GWWD photograph 31.

It was the GWWD’s sideline running excursion trains for tourists that would prompt an additional dispossession of Shoal Lake 40’s land. In October 1919 Waugh wrote to John Semmens, then Dominion Inspector of Indian Agencies, explaining that the GWWD wanted another thirty-two acres of reserve lands. Waugh almost admitted that this was a lot to ask. “We have no desire to further encroach on the Indian reserve,” he explained, before asking that the GWWD be given “jurisdiction or control” over the swimming beach in order to protect the water supply. Again this matter was framed as one between the DIA and the GWWD, though Waugh did make a half-hearted promise to do “everything in reason” to protect “the Indian cemetery” that the tourists were so interested in and such a threat to.74

Workers tunnelling under the Red River to build the Aqueduct, May 1918. Photograph by the iconic Winnipeg photographer L.B. Foote. Courtesy of the Archives of Manitoba, N2379. Thanks to the University of Manitoba Press and Ariel Gordon.

Federal officials were unimpressed with the GWWD’s lackluster response to their request for a “proper survey” and, later, with the meager price offered by the GWWD. In December 1919 Semmens announced that he was going to travel to Shoal Lake 40, “to assure myself that nobody’s claim is being interfered with under the desired possession of the land asked for” and to “consult the Indians so as to be able to tell the Department what they think about the surrender of the portion specified.”75 Correspondence had earlier mentioned again invoking Section 46 of the Indian Act, but instead the DIA returned to the more conventional surrender process. The DIA recommended $15 per acre as a price, but reported that Shoal Lake 40 “would not let this piece of their Reserve go for less than $25 per acre, as it was the best piece of land on the Reserve.” The surrender process was complete early in June 1920, and the GWWD wrote a cheque for $640.76

A photograph labelled “Party at Indian Bay” ca. 1916-17 suggests how the GWWD railroad made Shoal Lake a location of genteel, gender-segregated settler recreation and sociability. Published with permission of the Greater Winnipeg Water District and the City of Winnipeg Archives. GWWD photograph 547.

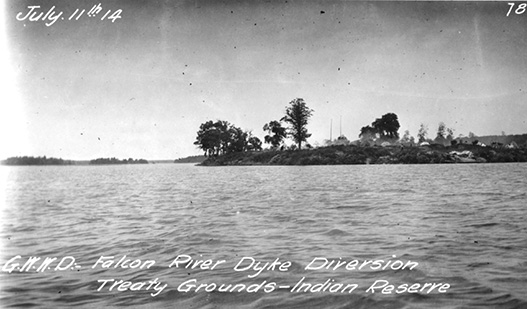

Shoal Lake 40 reserve and treaty grounds, July 1914. Published with permission of Shoal Lake 40 First Nation, the Greater Winnipeg Water District, and the City of Winnipeg Archives. GWWD photograph 78.

Alongside the Aqueduct came what its boosters proudly called a “colonization scheme” to encourage and coordinate non-Indigenous settlement and agriculture along the GWWD’s route. Cooperating with the federal government, the GWWD announced “Free homesteads of approximately forty acres each” along the Birch River. With the provincial government, the GWWD announced plans for a model farm at Reynolds.77 A detailed work of community history documents the modest settler communities that came out of these plans, and suggests a more complicated and less secure history of resettlement. Here mainly eastern European migrants farmed, worked for the GWWD, and lived lives along the Aqueduct’s path.78

Shoal Lake water flowed in Winnipeg mains for the first time in March 1919, about five months after the armistice that ended World War One and a few months before Winnipeg would be rocked by the General Strike. It had cost about $17 million to build the Aqueduct, roughly $4 million over the initial estimates.

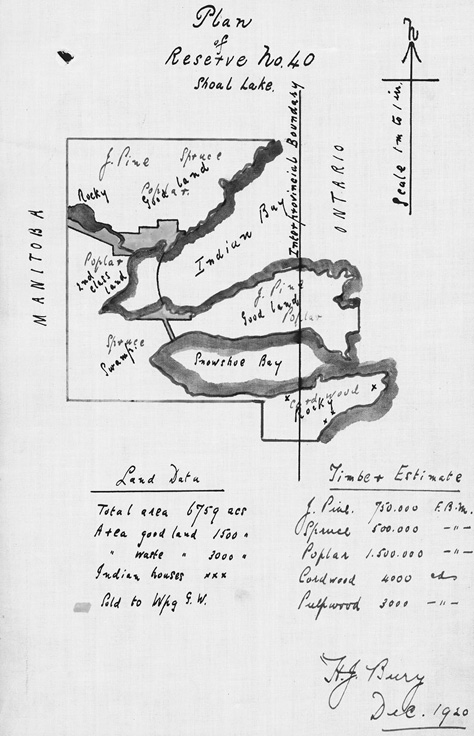

A map of the Shoal Lake 40 reserve showing the Aqueduct intake, land “sold to” the GWWD, and the international boundary, December 1920. Image courtesy of Library and Archives Canada, Mikan 3719724.

Steep costs did not dampen the local press’s enthusiasm. The Tribune celebrated, declaring: “At last! Shoal Lake Soft Water in Winnipeg Mains.” They reminded readers that this reflected spectacular urban growth and promise, commenting that “Wondrous growth of city” was the reason for the Aqueduct. The Tribune promised that “Unlimited Supply is obtained” and “Water is Free from Impurities.”79

It was not until September of 1919 that Edward, Prince of Wales, would officially “open” the Aqueduct.80 Winnipeg declared a civic holiday and the streets were “gay with bunting.”81 This was a suitably imperial way to conclude the very colonial act of transporting drinking water from an Anishinaabe community to the settler city of Winnipeg. Of course, Prince Edward did not go to Shoal Lake, to the GWWD intake, or the Anishinaabe community whose lands were expropriated in order to build the Aqueduct. This celebration of the Aqueduct occurred entirely within the urban space of Winnipeg.

This urban and imperial celebration foreshadowed the relationship between Winnipeg, memory, and water supply that existed for the century that followed. The city that needed a good source of drinking water and devised an ambitious scheme to get it would recall their triumph fondly and often. In these discussions, what occurred and was occurring at the other end of the pipe rarely received even a passing glance.