5

The Histories We Remember

History is a cacophony. There is always more that happened than is passed on in word or on paper. There is always more that occurred than is recorded, more said than unsaid. We pull some things out to preserve, to remember, to analyze, and sometimes, to mourn or to celebrate. What is recalled, commemorated or left behind reflects our individual interests and agendas, and more than that, our social practices and priorities. What histories we choose to remember and what we choose to forget or minimize necessarily tells us more about the present than the past.

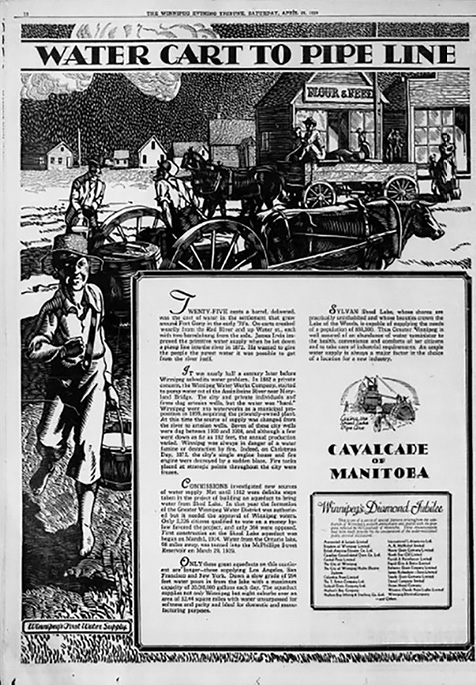

A 1934 story in The Winnipeg Evening Tribune saw the history of Winnipeg’s water supply as evidence of the onward march of modernist progress. Image courtesy of the University of Manitoba Archives and Social Collections.

It took very little time for the Aqueduct to be transformed from a subject of Winnipeg’s auspicious present and its promising future to a subject of the city’s illustrious and portentous past. Here the Aqueduct was described as an example of local genius and civic-mindedness. In 1923 An Historical Souvenir Diary of the City of Winnipeg, Canada was published to document the city’s “progress from a settlement village to a prosperous modern city known as THE GATEWAY OF THE WEST.” It documented and illustrated through the particularly modern medium of photography the selection, building, and use of the Aqueduct. The claim that “There are only four other communities in the world that have gone a greater distance to secure their water supply than have the Greater Winnipeg Water District” speaks to the culture of celebration, and to the reaching claims that sometimes went with it.1 Elsewhere the Aqueduct was described as the “largest public works in the British dominions.”2

The celebration of the Aqueduct and its role in Winnipeg’s past, present, and future continued as Winnipeg’s water system aged and was tested by suburban growth. When the Aqueduct was twenty-five years old, the Winnipeg Evening Tribune paid special tribute to “the group of men who three decades ago planned and carried through the building of an aqueduct over ninety miles of wilderness to the city.”3 Three years later, a souvenir booklet published for the seventy-fifth anniversary of Winnipeg’s incorporation explained how “the great aqueduct” made the city’s drinking water “the envy of cities all over the continent.”4

Monument to the Aqueduct’s Second Branch, opened in 1960. Nestled in a median on the busy Bishop Grandin highway in Winnipeg’s southern suburbs. Photograph by Michael Yellowwing Kannon.

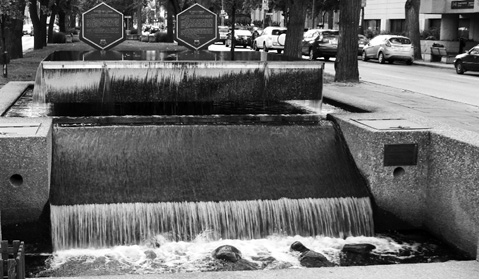

Fountain and plaque dedicated to the Aqueduct. Unveiled in 1975, it is located in the boulevard on Winnipeg’s Broadway Avenue. Photograph by Michael Yellowwing Kannon.

As the twentieth century wore on, these celebrations of the Aqueduct were built into the fabric of the city in monuments and plaques. The first monument to the Aqueduct was unveiled at the opening of the Aqueduct’s Second Branch in 1960. Located in the city’s southern suburbs, this monument celebrates the expansion of the Aqueduct to support mid-twentieth-century suburban growth.5 Roughly fifteen years later a group of private companies funded an ornamental—and suitably watery—fountain and plaque on Winnipeg’s Broadway Avenue. In 1975, a report found that the Aqueduct was “a unique achievement; the first gigantic engineering enterprise in Western Canada” and “a tribute to the spirit and enterprise of Canadians at the turn of the century.”6

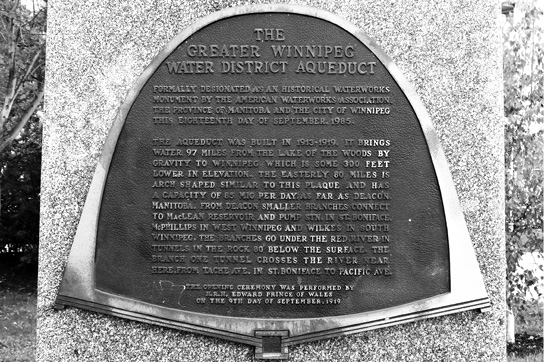

One of the plaques that adorns the Aqueduct monument at Winnipeg’s Stephen Juba Park, named for the famed mid twentieth-century mayor. Photograph by Michael Yellowwing Kannon.

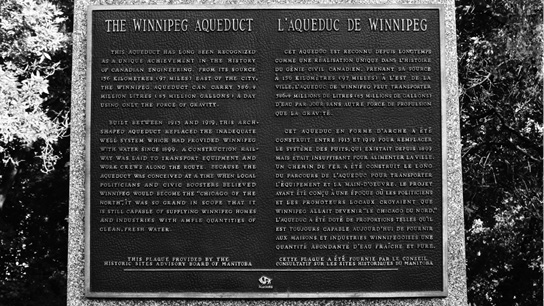

The final decades of the twentieth century saw the public commemoration of the Aqueduct proliferate. An imposing stone monument in Winnipeg’s downtown Stephen Juba Park bears three plaques: one from the American Water Works Association, one from the National Historic Civil Engineering Site, and one contributed by the Historic Sites Advisory Board of Manitoba.7 The engineering organization’s plaques reiterate the Aqueduct’s status within a cross-border community of professionals. The provincial plaque locates the Aqueduct within a proud local history of civic-minded public policy. Installed in 1985, it reminds readers that the Aqueduct “was conceived at a time when local politicians and civic boosters believed Winnipeg would become ‘Chicago of the North’” and recalls the Aqueduct’s provision of “ample quantities of clean, fresh water.”8 Some time later another monument was built, this one a riverside lookout and a detailed bilingual plaque documenting the Seine River crossing of the Aqueduct.9 This plaque located the Aqueduct within the particular space of St. Boniface, once a separate city and now a neighbourhood of Winnipeg, associated with enduring Metis and French-speaking histories of the city.

Riverside lookout and plaque honouring the Aqueduct’s crossing of the Seine River in St. Boniface. Photograph by Michael Yellowwing Kannon.

These commemorations of the Aqueduct inscribe it in multiple layers of Winnipeg’s civic history. The plaques speak of engineering genius, public resources and health, and urban growth. None of these monuments or plaques gives a word or an image to Indigenous history of the Aqueduct. American historian Patricia Limerick’s study of the history of Denver, Colorado’s water supply argues that the forgetting of where water comes from is made possible by modernity.10 In the case of Winnipeg, it is also enabled by the social relations of colonialism. In celebrating what the Aqueduct has done for the city, public commemoration reinforces the dispossession and erasure upon which Winnipeg’s water supply depended.

Stone monument to the Aqueduct bearing multiple plaques. Erected in 1985 and located in Stephen Juba Park. Photograph by Michael Yellowwing Kannon.

Plaque to the Winnipeg Aqueduct provided by the Historic Sites Advisory Board of Manitoba. The emphasis here is on the Aqueduct as an example of public-minded social policy. Photograph by Michael Yellowwing Kannon.

Efforts to reinterpret Winnipeg’s history have drawn our attention to the radicalism and potential of the 1919 General Strike, to the multiple histories of immigration, and, more recently, to the long Indigenous histories of this place and of Red River Settlement. They have had less to say about how colonialism built and maintains the modern city. What might a plaque that acknowledges Shoal Lake’s experience of the Aqueduct history look like, and how might it change the meaning of those that mark the Aqueduct’s achievements?

It was not that the Anishinaabe communities of Shoal Lake did not protest the lot that settler colonialism offered them. As soon as Ottawa sold Shoal Lake 40’s land to Winnipeg, its Chief, Pete Redsky, used available channels to demand a better deal. In 1918 Redsky wrote to Ottawa and declared that “We are now very anxious for ‘The district’ to pay for our land, and if they are not willing to pay for our land, I think they had better hand it back.” Driving the point home, he said “I think it is time for you to fix up with us” and proposed to lead a delegation to Ottawa to meet the minister in person.11 The DIA replied that it would “be useless for the delegation to visit Ottawa during the session.”12 Shoal Lake 40’s advocacy and persistence did prompt the DIA to distribute some of the funds they held “in trust.” On treaty day in 1919, Shoal Lake 40 members each received an additional $15, representing half of the monies received from the GWWD and the interest earned by it in the intervening years.13 A decade later, Chief Redsky was still making pointed inquires about “his band’s land sale to Greater Winnipeg Water District Railway” and how funds had been distributed or not.14

The building of the Aqueduct set in motion a chain of events that had enormous consequences for Shoal Lake 40. The GWWD railroad that provided regular passenger service between Winnipeg and Shoal Lake stopped doing so when Ontario Highway 17 (the Trans-Canada) was built in the 1930s, and Ontario Highway 673 in the 1950s. The reorientation away from rail and toward automobile travel continued. The reduced passenger service offered by the GWWD railroad ended altogether in 1977. The summertime excursion trains ran for a bit longer but completely stopped in 1983.15 The artificial isolation of Shoal Lake 40 was complete, and it remains as such in early 2016, a long string of plans, agreements, and promises notwithstanding.

The story of Winnipeg and the Aqueduct is a particularly revealing and jarring example of how settler colonialism works. It shows how colonialism takes resources from Indigenous peoples and delivers them to settler ones. Often the commodity is land, but the Aqueduct shows us how these colonial logics have played out around the resource of clean drinking water. In vivid terms, the Aqueduct also shows us how the settler colonial politics of dispossession depends on erasure and regularly re-enacted forgetting. For almost a century, Winnipeg has not only benefitted from the water of Shoal Lake, but has done so with very little acknowledgement of what this cost the people at the Aqueduct’s source.

There have always been challenges to these well-worn and remarkably powerful practices of colonial denial. In the early 2000s these challenges grew and came to meaningfully oppose longstanding ideas about the significance of the Aqueduct. Shoal Lake 40 spoke, wrote, and took action that articulated a different understanding of what Winnipeg’s water system meant. “Residents of island reserve march for 5 days to Winnipeg to demand road,” explained The Globe and Mail in May 2007.16

In 2014, the opening of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg put the disjuncture between Indigenous and settler Canada in general—and Shoal Lake and Winnipeg in particular—in a new and sharper light. Shoal Lake 40 pitched a teepee outside the imposing museum and explained where the water in the exhibits came from and what it had cost them. Shoal Lake 40 Chief Erwin Redsky and Pimicikamak Okimawin (Cross Lake) Chief Cathie Merrick explained in the national press that the museum was a “towering shrine to hypocrisy.”17 The community opened their own Museum of Canadian Human Rights Violations on the Shoal Lake 40 reserve, inviting Canadians and international observers to come and see what life was like at the other end of the Aqueduct.18

In 2014 and 2015 Winnipeggers began to demand that a concrete, material measure address the radical inequality that underlies our municipal water. On Canada Day 2015, Rick Harp, the author of the foreword here, asked on Twitter: “In what possible scenario is it just that those who provide the source of the water are somehow left unable to survive from that water?”

Harp’s question cuts to colonialism’s core. It resonates in a country where the pasts, presents, and futures of Indigenous people and settlers were and are under new kinds of scrutiny. This is true for Canada as a whole and especially true for Winnipeg, Canada’s most Indigenous city both in terms of sheer numbers and proportion of overall population.19 With about one in twelve Winnipeggers claiming an Indigenous identity in 2013, the schism between an Indigenous hinterland and a settler city that twentieth-century policy and law worked to enact and shore up has been significantly rearranged.

The mainstream national media has tended to see this transition in sensational terms, describing Indigenous Winnipeg in ways not unlike how early twentieth-century journalists described migrant Winnipeg. But this is not the only way that Winnipeg’s Indigenous present can be interpreted. Award-winning poet Katherena Vermette names Winnipeg’s North End the “heart” of a female, generative, and powerful Indigenous present and future.20 Winnipeg represents a cogent example of Indigenous peoples’ persistence and voluble presence in what anthropologist Audra Simpson calls the teeth of settler colonialism.21

Settler colonialism works to dispossess Indigenous people not only of land but also of resources, including, in this case, the crucial one of good drinking water. Late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Winnipeg was beset with public health problems that were directly and indirectly tied to a lack of clean drinking water. Civic leaders thought that poor water supply limited the city’s growth and hampered the expansion of industry. The Aqueduct was designed to solve these problems, though it was by no means an easy or inexpensive solution.

The building of the Aqueduct between 1913 and 1919 required the coordination of municipal, provincial, federal, and American authorities. It relied on the sweeping powers of the Indian Act and its capacity to legally separate Indigenous people from their lands and resources in a number of ways. The Aqueduct depended on enormous amounts of political will, complicated legal manoeuvers, agreement of multiple levels of government, and a great deal of money and enthusiasm. At its core, the building of the Aqueduct was predicated on a pervasive silencing and denial of Indigenous lives, one that was re-enacted in history books, reports, and on cheerful, informative plaques that dot present-day Winnipeg.

Winnipeg solved its enduring water problems by setting into motion a chain of circumstances that rendered Shoal Lake 40 without essential services, the capacity to travel to and from their homes in relative safety, economic opportunity, and ultimately the very commodity that their isolation was enacted to provide Winnipeg with: clean drinking water. Shoal Lake 40’s Museum of Canadian Human Rights Violations documents a whole string of promises to address the perilous circumstances in which their community has been for a century. Late in December of 2015 an agreement between municipal, provincial, and federal governments to work with Shoal Lake 40 to build Freedom Road was announced amid much ceremony and genuine hope. If all goes well, the road should be ready for use sometime in 2017.

Governments make announcements all the time, and roads get built all the time. What makes Freedom Road different is what it means for Shoal Lake 40 and, in a very different way, for the city that has been nourished on Shoal Lake water. The histories of Shoal Lake 40, of Winnipeg, and the concrete aqueduct that links us to one another tells us a lot about how settler colonialism works in modern Canada, about how it resources settler communities at the direct expense of Indigenous ones. This road, perhaps, will tell us about the power and the limits of our responses to this heavy history.