A DEMOCRATIC society operates on the pluralistic principle of competition among social organizations, the scope and character of which are determined by the natural differences modern society produces: class, occupation, ancestry, religion, cultural interests, and so forth. No matter how thoroughly the society may be organized, such competition still preserves some of man’s spontaneity. Since there is no authority which can compel the behavior of the mass organizations, however, the establishment of a social equilibrium requires that the various organizations adjust their conflicting interests by agreements. Antagonisms, strikes, disputes, lock-outs, political disturbances can safely be allowed to exist in a democracy as long as the society can count upon the good will of the leaders and rank and file of the social organizations, upon their readiness to make adjustments and compromises.

National Socialism has no faith in society and particularly not in its good will. It does not trust the various organizations to adjust their conflicts in such a way as to leave National Socialism’s power undisturbed. It fears even the semi-autonomous bodies within its own framework as potential nuclei of discontent and resistance. That is why National Socialism takes all organizations under its wing and turns them into official administrative agencies. The pluralistic principle is replaced by a monistic, total, authoritarian organization. This is the first principle of National Socialist social organization.

The second principle is the atomization of the individual. Such groups as the family and the church, the solidarity arising from common work in plants, shops, and offices are deliberately broken down. The treatment of illegitimacy and procuring, for example, reveals the complete collapse of traditional values. The birth of illegitimate children is encouraged, despite the fact that the sacredness of the family is supposed to be the cornerstone of National Socialism’s ‘domestic philosophy.’1 Thus, when the federal supreme labor court had to decide whether an employer could dismiss an unmarried pregnant woman without notice, it ruled in the negative on the ground that such pregnancy need no longer be regarded as ipso facto ‘immoral and reproachable.’2 The commentator adds:

Our views of today, based on a concept of morality that is in unison with nature, living force, and the racial will to life, must, if it affirms the [sexual] drive, affirm the naturally willed consequence, or more correctly, the naturally willed aim. For it is solely the latter which justifies and sanctifies the drive.

This attitude, we must remember, is not part of a progressive social and eugenic policy. On the contrary, it is thoroughly hypocritical, an imperialistic attitude accompanying the ideological glorification of the family.

A second example is perhaps even more illustrative not only of the destruction of family life but also of the prostitution of the judiciary. Pre-National Socialist courts had generally ruled that toleration by the future parents-in-law of sexual intercourse between an engaged couple was punishable as procuring. Under pressure from the regime, particularly in the Schwarze Korps, organ of the SS, the courts have reversed themselves. One decision actually quotes the diatribes in the Schwarze Korps in justification of the reversal.3 Again it is not a matter of a new and honest philosophy of society. It is merely a function of its imperialism, intensified by a bohemian desire to épater le bourgeois.

There must be no social intercourse outside the prescribed totalitarian organizations. Workers must not talk to each other. They march together under military discipline. Fathers, mothers, and children shall not discuss those things that concern them most, their work. A civil servant must not talk about his job, a worker must not even tell his family what he produces. The church must not interfere in secular problems. Private charity, even of a purely personal nature, is replaced by the winter help or by the other official (and totalitarian) welfare organizations. Even leisure time is completely organized, down to such minute details as the means of transportation provided by the authoritarian Strength through Joy organization. On the argument, purely, that the bigger the organization the less important the individual member and the greater the influence of its bureaucracy, National Socialism has set about increasing the size of its social organizations to the utmost limit. The Labor Front has about twenty-five million members. Of what account can the individual member be? The bureaucracy is everything.

The natural structure of society is dissolved and replaced by an abstract ‘people’s community,’ which hides the complete depersonalization of human relations and the isolation of man from man. In terms of modern analytical social psychology, one could say that National Socialism is out to create a uniformly sado-masochistic character, a type of man determined by his isolation and insignificance, who is driven by this very fact into a collective body where he shares in the power and glory of the medium of which he has become a part.

So vast and undifferentiated a mass creates new problems. It cannot be controlled by an ordinary bureaucratic machine. National Socialism therefore seeks to carve out from the masses certain élites who receive preferred treatment, greater material benefits, a higher social status, and political privileges. In return the élites act as the spearhead of the regime within the amorphous mass. When necessary one group can be played off against the other. The racial Germans are the élite in contrast to the peoples living around them. The National Socialist party is the élite within the racial German group. Within the party, the armed forces (S.A. and S.S.) constitute further élites. And even within the S.S., there are élites within an élite.* The same is true of the Hitler Youth, the Labor Front, and the civil service. The élite principle not only preserves the distinction between manual and white-collar workers but goes still further and differentiates among the working classes as well. One small body of skilled workers is raised above the level of the unskilled and semi-skilled.† None of these stratifications are the natural outcome of a society based on division of labor. They are the product of a deliberate policy designed to strengthen the hold of the leadership over the masses. Differentiation and élite formation make up the third principle of National Socialist social organization.

To prevent the masses from thinking, they must be kept in a permanent state of tension. That is accomplished by propaganda. The ideology is in an unceasing process of change and adaptation to the prevailing sentiment of the masses. The transformation of culture into propaganda and the transience of the slogans constitute the fourth principle of National Socialist social organization.

Propaganda wears out, however, and it wears out all the more rapidly the faster the slogans are changed. So it is supplemented by terror. Violence is not just one unimportant phenomenon in the structure of National Socialist society; it is the very basis upon which the society rests. Violence not only terrorizes but attracts. It is the fifth and final principle of National Socialist social organization.

The position of the working class alone of the ruled classes will be analyzed to illustrate the methods of mass domination and the status of the subject population. Certain historical trends and general sociological consideration must be studied first, however, to provide the necessary background.

Property is not merely control over material things.4 It is a relation between men through the medium of things and thus confers power over human beings as well. The owner of property in the means of production controls the individual as worker, consumer, and citizen. The worker’s only property is his labor power. He is separated from the means of production and yet he can turn his labor power to useful account only by combining it with the means of production, which do not belong to him and concerning which he has no say. Property in the means of production, therefore, exerts a twofold influence upon the worker: It attracts him into its orbit and it controls him. From the moment the worker enters the factory gate he surrenders part of his personal freedom and places himself at the disposal of an outside authority.

The owner of property controls the worker as worker in five spheres: the plant (the technical unit), the enterprise (the economic unit where business decisions are reached), the labor market, the commodity market, and the state. The power of property to draw men into labor contracts and to dictate their behavior while at work sets a series of problems for the working class and for the state. The major problem is how to replace the employer’s dictatorial power by a democratic power in which the workers too shall share. This is the task of the trade unions. Their function may be divided under three heads. First, they act as friendly (or benefit) societies. They provide sickness and accident benefits, unemployment benefits, strike and lock-out pay, old-age pensions, and legal aid. Almost all the state systems of unemployment relief, labor exchanges, accident and sickness insurance are modeled after arrangements devised by the trade unions. This group of trade-union activities (the inner trade-union function) has been carried furthest in England, whose example had a marked effect on German trade unionism.

The second function of a union is its marketing function or collective bargaining. The union seeks control of the labor market, confronting the power of private property with the power of organized workers and either laying down the conditions of work and pay or, where the state regulates these conditions, seeing to it that the governmental regulations are actually carried into effect. The more important of the two is the collective agreement backed by the threat of a strike.

Finally, the trade unions are political bodies bringing pressure on the state in all three of its functions, legislative, executive, and judicial. It is impossible to say which of the three types of union activity is of greatest importance. The answer depends on the particular historical, political, and economic situation in each case. The attempt to influence the state is always present and always basic, however, partly because the state can so strongly affect the benefit and market functions of the workers’ organizations.

Four stages can be distinguished in the historical development of the relation between the trade unions and the state, with some overlapping and repetition. Trade unions were illegal in the early period of capitalism. Every state prohibited any combination of workmen formed for the realization of social aims, as in the French Le Chapelier law passed early in the Revolution on 14 June 1791. In England, the French Revolution frightened the governing class to such an extent that they too suppressed the trade unions in order to prevent revolution. The Prussian General Civil Code (das allgemeine Landrecht) forbade stoppages on workdays and thus blocked the use of the main trade-union weapon, the strike. Collective contracts regulating conditions of employment were null and void during this early period. Trade unions were forcibly dissolved and membership became a punishable offense.

Despite all opposition, however, the trade-union movement continued to grow and at some point every state was forced to rescind its anti-combination laws. The earliest signs of this second stage appeared in England in 1824. In France, a law of 25 May 1864 gave recognition to labor’s freedom to organize, though, as in the English statute of 1825, the restrictive criminal laws were retained. In Germany the period of prohibition lasted until 1869. The Industrial Code of the North German Federation, adopted in May of that year, lifted the ban on combinations for the first time, but only for industrial workers. Agricultural laborers, domestic servants, seamen, and state employees were excluded from the privilege. Criminal laws continued to impose heavy obstacles.

The repeal of Bismarck’s anti-socialist laws and the enactment of the industrial code made possible the establishment in 1890 of the Generalkommission der Gewerkschaften, a central body of the ‘free’ or socialist trade unions. In 1919, this body was transformed into the Allgemeine Deutsche Gewerkschaftsbund, similar to the British Trades Union Congress or the American Federation of Labor.

The common characteristic of this second period, the era of toleration, was that the social power of the working-class movement had forced the state to abandon direct prohibition of trade unionism and to resort to indirect interference through a whole series of special provisions and with the help of the penal code, the courts of law, and particularly the police force. Philip Lotmar, pioneer in German labor law, summed the situation up in these words: ‘The trade union is free, as free as an outlaw’ (Die Gewerkschaft ist frei, aber sie ist vogelfrei).

The triumph of democracy brought with it recognition of the trade unions; it gave them a new status and their threefold function was acknowledged without qualification. The clearest expression of this stage was found in Germany, England, and Austria.4

The German trade-union movement had a short but stormy history dating from 1877. The German Constitution of 11 August 1919 gave the trade unions special recognition. Articles 159 and 165 acknowledged their existence as free bodies vis-à-vis the state. Neither the cabinet, the legislature, nor the police was to have the right to dissolve the unions. In return, they were called upon to fulfil certain positive tasks. In the pluralistic collectivism of Weimar, the trade unions played the decisive role. More than the political parties, they were the bearers of the new form of social organization, the bridge between the state bureaucracy and the people, the agency for developing a political democracy into a social democracy.

A law of 11 February 1920 introduced the system of works councils restricting (to draw an analogy between factory and state) the employer’s power and introducing the elements of constitutional government into the plant.5 Like the state, an industrial enterprise has three powers: legislative, executive, and judicial. Prior to the works-council law, the employer exercised all three powers: he was the legislator because he issued the factory rules; the executor because he hired and fired; the sole judge because he inflicted the punishments for violations of the factory rules. The works-council act vested the legislative power jointly in the hands of the employer and the council. The members of the council were elected by secret ballot according to the principle of proportional representation, with various trade-union tickets competing and without any influence from either the state or the employer. If no agreement could be reached between the works council and the employer, a board of arbitration (later the labor court) issued the factory rules.

The works council also had a voice in factory administration, though only a limited one. If it upheld the protest of a dismissed worker, for example, the latter could sue in the labor court for reinstatement or for monetary damages. The council also supervised the execution of collective agreements and the observance of the factory rules, and generally protected the employees. It had the right to have two delegates attend meetings of the corporation’s board of directors and to examine the balance sheets and profit-and-loss statements. These provisions had little practical importance, however.

The works councils were what the Germans called ‘the elongated arms’ of the trade unions. Though formally independent of the unions, they constantly relied on them for assistance in the fulfilment of their duties. Council members were trained in trade-union schools and supported by the unions in every conflict with the employers. The unions in turn leaned heavily on the councils for such functions as enforcement of maximum-hour legislation.

In general, the attempt to give the working class direct influence in the sphere of the private enterprise was not particularly successful. Reaction, impotent when the statute was enacted early in 1920, set in again too soon for that. Trade-union influence in the commodity market was equally weak—except in the coal and potash industries in which special laws (erroneously called socialization acts) provided for partial state management. The coal and potash unions could delegate representatives to the public boards of directors and were thus to a certain extent participants in management.

The most important influence of the unions was in the labor market. A decree of 23 December 1918, issued by the Council of People’s Deputies, recognized collective agreements as the legal means of determining wages and conditions of employment. Whenever trade unions and employers’ associations arrived at collective agreements, the provisions became part of the employment contract between the employer and each of his workers. They had the force of objective law. No deviation could be made in the individual labor contract unless it favored the employee. This statutory provision formed the cornerstone upon which the whole structure of Republican German labor relations rested. Only organized workers and employers were affected by such agreements, however. To meet the danger that employers would hire only non-union men, the same law authorized the minister of labor, at his discretion, to extend an agreement to the whole of an industry or trade by decree. Frequent use was made of this power until 1931.

When a voluntary agreement could not be reached, the supposedly neutral state could intervene. Arbitration boards were created by a 1923 decree.6 The chairman was to be a state official and the members equally divided between employers and union representatives. If either party rejected a board decision, then an official of the Reich made an award that was binding, an imposed wage agreement between the employers’ association and the trade union.

With a few unimportant exceptions, the famed German system of unemployment insurance was the creation of the Weimar constitution and of the trade unions. The basic law of 1927 also provided for the regulation of labor exchanges, placing the whole system under the Reich Board for Employment Exchanges and Unemployment Insurance, divided into one central, 13 regional, and 361 local boards. Each had an equal number of representatives of employers, workers, and public bodies (states, municipalities, etc.) under the chairmanship of a neutral official. Ultimate supervision rested with the minister of labor. We have here one more expression of collectivist democracy, with the state calling upon autonomous private groups to help execute the business of government efficiently.

The regulation of wage rates and conditions of employment can be effective only if accompanied by unemployment benefits sufficiently high to prevent a severe drop in wages. After many struggles and legal disputes, the trade unions eventually succeeded in establishing the principle that the union scale of wages should be paid to relief workers in order to prevent a downward pressure on the wages of employed workers. The whole system was supplemented by extensive insurance against accident, illness, and old age, applying to manual and professional workers alike.

The fifth and last domain in which the rule of property comes to the fore is the state. The trade unions could not participate directly in the legislative process because the framers of the constitution had rejected the proposal of a second chamber organized along professional and occupational lines of representation.* They could exert considerable influence, nevertheless. In 1920, for example, the trade unions defeated the Kapp Putsch by a very effective general strike. All the trade unions were attached to political parties, furthermore, and exercised a strong political role in that way. The free unions were attached to the Social Democratic party and the Democratic to the Democratic party. The Christian unions were linked with the Center party, though their white collar and professional wings were more closely allied with the German Nationalist party and later with the National Socialists.

The Social Democratic party was financially dependent on the unions, and the increasing frequency of elections increased this dependence. As a result, a large number of trade-union functionaries found their way into the Reichstag. There they naturally spoke for the union policy, social reform, and at times created peculiar situations. In 1930, for example, the Reich cabinet, headed by the Social Democratic leader Hermann Müller, had to resign at the request of the free trade unions because the other parties in the coalition were unwilling to raise the unemployment-insurance contributions. No important political decision was made without the trade unions. In fact, their influence was invariably stronger than that of the Social Democratic party.

In the judicial sphere the trade unions participated actively in the administration of labor law. They had great influence in the labor courts created by act of 1927 to settle disputes between employers and employees, between employers and works councils, between the parties to a collective bargaining agreement, and among employees in group work. The three courts of the first, second, and third instance each consisted of a judge and an equal number of trade union and employers’ association representatives. Only trade-union officials could represent the worker in the first court; in the second the worker could select either a union official or an attorney; but only lawyers could plead in the third. Thus, as the recognized representatives of workers, the unions were called on to advise in state affairs in this sphere as well.

It must be said in conclusion that this vast system of collectivist democracy was never carried through completely. The constitution promised it, but the continued and growing political power of reaction blocked fulfilment of the promise. The Weimar Republic, a democracy of the Social Democratic party and trade unions, did achieve two things. It won for the working man a comparatively high cultural level and it had begun to give him a new political and social status.

Two basic developments occurred during the period of trade-union recognition. The competitive capitalist economy was fully transformed into a monopolistic system and the constitutional state into a mass democracy. Both trends changed the whole structure of state and society. The influence of the state enjoyed uninterrupted growth. The state itself assumed extensive economic functions. With its representatives presiding on all parity boards, it acquired an increasingly decisive influence in the sphere of social policy, especially because the two sides could so rarely reach an agreement by themselves.

Mass democracy strengthened the political consciousness of the working class. The First World War had made the working class throughout the world conscious of its needs and its power and finally detached the working-class movement from the bourgeois political parties.

The functioning of the trade unions was seriously affected by each of these developments. The extensive introduction of improved scientific methods of production created technological unemployment. Growing standardization and rationalization of industry altered the composition of the working population. The rise of cartels, trusts, and combines created a new bureaucracy. The number of office workers, clerks, officials, and technical superintendents increased. There was a leap in the proportion of unskilled and semiskilled workers (especially women) at the expense of skilled labor. Contracting markets and intense competition requires an enlarged distributive apparatus, increasing the number and proportion of workers engaged in this sphere.

Social legislation facilitated the trend toward the concentration of capital, with all that it brought in its train. A pattern of high wages, short hours, and good working conditions places the heaviest financial burden on medium and small-scale undertakings. Large-scale enterprises escape because they use relatively little labor and much machinery. Every enforced rise in wages and every increased expenditure imposed by the demands of social legislation forced the producer to save elsewhere. The ‘saving’ usually took the form of labor-saving devices.

The German trade unions deliberately fostered this rationalization process because they believed with undue optimism that the technological displacement of workers would lead to greater employment in the capital-goods industries and that the ensuing rise in purchasing power would increase production all around and lead to reabsorption of the unemployed in the industries producing consumers’ goods.

Faced with powerful monopolist opposition, the trade unions needed the help of the state. But at the same time the growth in governmental economic activity led to a new conflict. By participating in industry as a producer and shareholder, the state itself frequently became the opponent of the unions in matters of wages and working conditions.

The altered composition of the working population and the chronic unemployment of the depression era measurably weakened the appeal of the trade unions. Their membership fell off and unemployment drained their treasuries. They had to reduce their benefit payments—at the very time when vast unemployment forced a sharp cut in the size and number of state unemployment payments.

Unskilled workers, inspectors, administrative officials, shop assistants, and women workers increased in proportion, and they are extremely difficult to organize. The increased role of the professions and salaried posts heightened the significance of their trade unions, but most of these unions were middle class in outlook. The salaried and professional employee did not want to ‘be reduced to the level of the masses.’ He fought to retain his tenuous middle-class status and his privileges, and he succeeded. White-collar and manual workers were treated differently in the social legislation. Social insurance benefits were higher for the former. The period of notice to which they were entitled before being dismissed was longer. No party dared oppose their demands nor those of the minor government officials, whose henchmen were present in every political faction. The attitude of capital was simple—divide to rule; grant privileges to a small group at the expense of the larger. The ‘new middle class’ thus became the stronghold of the National Socialists.

Even the trade unions’ appeal to the vocational interests of the workers was weakened by the increased governmental activity in the regulation of wages and conditions of employment. The arbitration system, the legal extension of collective wage agreements to unorganized workers, unemployment insurance, and the entire paraphernalia of social insurance made the worker feel that he no longer needed his union. ‘If the state takes care of all these things, of what use are the trade unions?’ was a stock question in Germany.

The number of strikes diminished steadily. In 1931 not a single offensive strike was called by a German trade union. The risk involved became greater, success less certain. Only large sympathetic strikes could hold out any real prospect of victory. Every strike could easily have led to civil war, both because of the acute political crisis and because in a monopolistic economy every strike affects the entire economic system and the state itself.

A collectivist democracy, finally, binds the trade unions and the state in a closer relation. Though the unions remain independent and free, their close contact with the state leads them to develop a psychological attitude of dependence that discourages strikes.

Neither the trade unions nor the political parties were able to cope with the new situation. They had become bureaucratic bodies tied to the state by innumerable bonds. In 1928 the Social Democratic party boasted of its phenomenal achievements in government. The following statistical summary was captioned, ‘Figures every official should know.’7

33 |

regional organizations |

152 |

Social Democratic Reichstag deputies |

419 |

Social Democratic provincial deputies |

353 |

Social Democratic aldermen (Stadträte) |

947 |

Social Democratic burgomasters |

1,109 |

Social Democratic village presidents (Gemeindevorsteber) |

4,278 |

Social Democratic deputies of the Kreistag (sub-provincial bodies) |

9,057 |

Social Democratic deputies of the municipal diets |

9,544 |

local organizations |

37,709 |

Social Democratic village deputies |

1,021,777 |

party members (803,442 men, 218,335 women) |

9,151,059 |

Social Democratic votes (Reichstag election of 1928). |

The Communist party indulged in similar boasts:

360,000 |

members |

33 |

newspapers |

20 |

printing houses |

13 |

parliamentary deputies |

57 |

deputies in state diets |

761 |

municipal deputies |

1,362 |

village deputies.8 |

Nor is this all. The trade-union bureaucracy was much more powerful than the corresponding party bureaucracy. Not only were there many jobs within the unions but there were jobs with the Labor Bank, the building corporations, the real-estate corporations, the trade-union printing and publishing houses, the trade-union insurance organizations. There was even a trade-union bicycle factory. There were the co-operatives attached to the Social Democratic party and trade unions. And there were innumerable state jobs: in the labor courts, in the social-insurance bodies, in the coal and potash organization, in the railway system. Some union officials held five, six, and even ten positions at the same time, often combining political and union posts.

Bound so closely to the existing regime and having become so completely bureaucratic, the unions and the party lost their freedom of action. Though they did not dare to co-operate fully with Brüning, Papen, or Schleicher, whose cabinets had severely curtailed civil liberties and the democratic process generally and had cut wages and living conditions, neither could oppose these regimes. Real opposition would have meant strikes, perhaps a general strike and civil war. The movement was neither ideologically nor organizationally prepared for drastic struggle. They could not even fulfil their inner trade-union functions. What little funds remained after the depression were invested in beautiful office buildings, trade-union schools, real estate, building corporations, and printing plants. There was not enough left for their unemployed members.

The pluralistic social system of the Weimar Republic had broken down completely by 1932. No organization could fulfil its aims. The social automatism no longer functioned. The spontaneity of the working classes had been sacrificed to bureaucratic organizations, incapable of fulfilling their promise to realize the freedom of each by pooling individual rights into collective organizations. National Socialism grew in this seed-bed.

Upon seizing power, the National Socialist party planned to continue the trade-union organizations, merge the three different wings, and place the unified group under National Socialist leadership. Through their workers’ cell organization (the NSBO), they began negotiations with the Social Democratic union leadership. The two chairmen of the free unions, Leipart and Grassmann, were cooperative. They agreed to abdicate if the trade-union structure were retained. They publicly dissolved the alliance of the unions with the Social Democratic party and promised the future political neutrality of the trade-union movement. When the new regime proclaimed May Day a national holiday in 1933, the free trade unions passed a resolution of approval. This action, they said, was the realization of an old working-class dream.

The betrayal of a decade-old tradition in an attempt to save the union organizations from complete destruction was more than just cowardice. It was a complete failure to appreciate the real character of National Socialism, and it opened the eyes of the National Socialists. They saw that even the little strength they had attributed to the trade unions was an illusion. Besides, German industry did not trust the National Socialist workers’ cell organization too far. Had it not in the past instigated and supported strikes, though only for propaganda purposes? The ambitious Dr. Ley at the head of the party’s political organization therefore decided to seize control of the trade unions.

On 1 May 1933, the new national holiday was celebrated. A number of trade-union officials and a few members, still hoping to save their organizational structure, participated side by side with the National Socialists. The next day truck-loads of Brown Shirts and Black Shirts raided all union headquarters, arrested the leaders, seized the funds, and placed National Socialists in charge. Dr. Ley had in the meantime set up a ‘committee of action’ composed of Brown Shirts, Black Shirts, party officials, and representatives of the NSBO, with himself at the head.9 It took exactly thirty minutes for the huge trade-union structure to collapse. There was no resistance; no general strike, not even a demonstration of any significance. What further proof is needed that the German trade-union organizations had outlived their usefulness? They had become machines without enthusiasm or flexibility. They no longer believed in themselves.

On 12 May 1933, the property of the trade unions and their affiliated organizations was attached by the public prosecutor of Berlin—no one has ever been able to explain the legal basis for this action—and Dr. Ley was appointed trustee. He had been appointed leader of the German Labor Front two days before. On 24 June, the offices of the Christian unions were occupied and on 30 November, the Federation of German Employers’ Organizations decided to liquidate.

Under the influence of corporative ideas, the National Socialists originally planned to organize the Labor Front on three pillars: salaried employees, workers, and employers. For this purpose a simplified organizational structure was announced on 1 July 1933, with the workers divided into fourteen organizations and the salaried employees into nine, each under a leader and council. The corporative set-up was quickly abandoned in Germany, however.* It was particularly dangerous to the regime in the field of labor because, by articulating the working class into bodies distinct and separated from the employers, it implicitly recognized the differences created in society by the division of labor. Italy has retained at least the outward forms of a syndical and corporate structure; Germany not a trace. The reasons seem to be that the German working class is far more numerous and highly trained than the Italian, and, though not so militant as some groups in the Italian labor movement, far less amenable to authoritarian control.

After the one false start, the German Labor Front was deliberately planned to destroy the natural differentiations created by the division of labor. The first change occurred on 27 November 1933, initiating the transformation to a system of ‘federal plant communities’ (Reichsbetriebsgemeinschaften). To prepare the way, no new members were admitted to the Labor Front.10 On 7 December 1933, the old organizations were finally dissolved.

The Labor Front is now a body of approximately 25,000,000 members, including every independent and every gainfully employed person outside the civil service. It is the most characteristic expression of the process of complete atomization of the German working classes. It is divided into sixteen federal plant communities: food, textiles, cloth and leather, building, lumber, metal, chemistry, paper and printing, transportation and public enterprises, mining, banks and insurance, free professions, agriculture, stone and earth, trade, and handicraft. The important point is that the individual workers are not members of the federal plant communities. They are solely and exclusively members of the total body, the Labor Front itself. The plant communities are not lower organizational units out of which the Labor Front is formed. They are merely administrative departments within the Labor Front, organizing plants but not individuals. That is how much the regime fears that articulation along even occupational lines might lead to opposition.

The basic statute is the Leader’s decree of 24 October 1934. The Labor Front was raised to the rank of a party grouping* and its leadership is party leadership. At the head is the leader of the political organization of the party, Dr. Ley, who appoints and dismisses the lower leadership selected chiefly from the NSBO, the S.A., and the S.S. The finances of the Labor Front are under the control of the party treasury.† It has a central office divided into a number of departments. Departments 1 to 5 comprise the closest collaborators of the leader, the central supervisory staff, the legal and information departments, the training department, and so on. Department 6 is called ‘securing the social peace’ and is subdivided into the offices for social policy, for social self-administration, for youth and women, and for the sixteen federal plant communities. Department 7 is concerned with ‘raising the living standards.’ Its most important sub-division is the Strength through Joy office with its own sub-departments. Departments 8 to 10 are concerned with vocational training, the disciplinary courts of the Labor Front, and the plant troops.

The central office also has a number of auxiliary offices, such as the Institute for the Science of Labor, an institute of technology, and an office for the execution of the Four Year Plan. There are regional and local organizations sub-divided along territorial (street blocks) and functional (plant blocks) lines.

Even this monstrous structure does not complete the picture. Aping the autonomous organization of business, the National Socialists have set up a national chamber of labor and regional chambers. The national body is composed of the leaders of the federal plant communities, the provincial chiefs and the heads of the main departments of the Labor Front, and certain other individuals. It has never functioned. The provincial chambers have a similar composition and are equally inactive.

The tasks of the Labor Front were defined by the famous Leipzig agreement of 21 March 1935 between the leader of the Labor Front and the ministries of labor and economics.11 The minister of transportation entered the agreement on 22 July 1935 and the food estate on 6 October 1936. It is a most revealing document, for, by specific provision, it surrenders all the economic activities of the Labor Front to the national economic chamber and the ministry of economics. The national economic chamber was admitted to the Labor Front as a body, which meant that all the economic groups, every chamber of industry and commerce, every chamber of handicraft, and all provincial economic chambers are also affiliated as a body. So are the six national transportation groups and the food estate.

In order to compensate the Labor Front for this loss of independence, another elaborate body was created on paper, a federal labor and economic council composed of the councils of the national economic chamber and of the national labor chamber. This body has never functioned. Its tasks were defined in the Leipzig agreement and in Dr. Ley’s executive decree of 19 June 1935 as follows:

a. To deal with those tasks that the federal government, the German Labor Front, and the National Economic Chamber delegate to it;

b. to answer, clarify, and prepare . . . in joint discussions essential and fundamental questions of social and economic policy;

c. to receive pronouncements of the federal government, the German Labor Front, and the National Economic Chamber.

There could be no more patent fraud. The sole purpose of this elaborate mechanism is to create the impression that the Labor Front has an organization and tasks similar to those of the employers. In actual fact, the Labor Front exercises no genuine economic or political functions. It is not a marketing organization, since it has nothing to do with the regulation of wages and labor conditions. It is not a political organization of labor. It is not even an organization solely of labor. It has five functions: the indoctrination of labor with the National Socialist ideology; the taxation of the German working class; the securing of positions for reliable party members; the atomization of the German working classes; and the exercise of certain inner trade-union functions. Business, on the other hand, does have a functioning organization of its own on a territorial and functional basis. Labor has none. The Labor Front is merely one more organization of the whole German people without distinction as to occupation, training, or social status.

The primary task of the Labor Front is the indoctrination of the German working class and the destruction of the last vestige of Socialism and Marxism, of Catholic and democratic trade-unionism. This task is entrusted to the Labor Front proper through its countless officials in the central, regional, and local offices, above all through the so-called plant troops, reliable party members in each plant acting as the agents of National Socialist terrorism, and through the political shock troops.12 In the words of Dr. Ley, the shock troops are ‘the soldier-like kernel of the plant community which obeys the Leader blindly. Its motto is “the Leader is always right.” ’13 The shock troops are hot fused into a national organization. Each group is controlled by the local party organization in conjunction with the local Labor Front, and supervised by the main department of plant troops.

The NSBO, the original party organization in plants, shops, and offices, has been dissolved. Its fate was shared by the National Socialist handicraft and retail cell organizations (NS Hago). They had been the fighting outposts of the movement among the working classes and the small businessmen. Both were super-local organizations, and therefore out of harmony with the pulverizing policy of National Socialism. There was the danger that they could become centers of dissatisfaction and opposition through communication between workers of various plants and businessmen of different communities. They had to go.

What remains is only the Labor Front for party members and outsiders alike. Although there is no legal compulsion to join the Labor Front, the pressure is so strong that it is inadvisable for anyone to stay out. The members must attend meetings, but must not enter into discussion. They may put questions but have no right to insist on an answer. Its papers and periodicals are poor substitutes for the trade-union publications of the Republic. They are filled with pictures of the Leader and his entourage, war photographs, the speeches of the leadership, idyllic descriptions of life in the New Germany, glorification of the party and the Reich, and little else—certainly little information relevant to labor conditions.

The ties created by common work and common training are no longer articulated for the working classes. There are special organizations for doctors, dentists, lawyers; there are handicraft guilds, groups, chambers of commerce and industry, chambers of handicraft for businessmen—but the German worker and salaried employee alone of all the sections of the population have no organization built on the natural differences and similarities of work and occupation. The Labor Front has driven the process of bureaucratization to its maximum. Not only the relations between the enterprise and the worker but even the relations among the workers themselves are now mediated by an autocratic bureaucracy.

In no other field has the National Socialist community and leadership ideology encountered so much trouble as in labor law. The basis of labor law and labor relations is the individual contract in which the employee sells his labor power for a specified time, price, performance, and place. Even in a completely collectivistic system of labor law in which every worker is organized, there are individual agreements upon which the collective contract rests. The individual agreement remains the indispensable basis of all labor relations. For a collective agreement becomes effective only if individual agreements exist, whether forced upon the employer or employee or upon both. The individual labor contract of course hides the fact that the employee is subject to the power of the employer, but it is none the less a rational instrument dividing labor from leisure and clearly limiting the power of the employer in space, time, and function. In any modern society it must consider labor power as a commodity, though not exclusively so.

This simple consideration has been hotly denied by National Socialism. Labor power is not a commodity, they insist.15 The very concept of the individual labor contract is Romanistic.16 ‘The labor relationship is a community relationship based on honor, faith, and care, in which a follower utilizes his labor power for an entrepreneur, either in the latter’s plant or otherwise in his service. The labor contract is the agreement which creates and molds the labor relationship.’17

The basis of labor relations is ‘the ethical idea of faith.’18 ‘Not the materialistic Roman locatio conductio operarum but the Germanic structure of a contract of faith is decisive for the labor relationship . . . the follower enters the service of the entrepreneur and not only receives remuneration but above all protection and care. He not only performs work but promises faith and work, which is, so to speak, the materialization of it.’19

These quotations can be repeated endlessly. National Socialist politicians and philosophers provide a chorus chanting that labor is no commodity; labor is honor; the relation between employer and employee is a community relation.

The so-called charter of labor (the act for the regulation of national labor, 20 January 1934) begins with the following provision: ‘In the plant, the entrepreneur as the plant leader and the salaried employees and workers as the followers work jointly for the furtherance of the aims of the plant and for the common benefit of people and state.’ This plant community ideology bears a strong resemblance to the theory of the ‘enterprise as such’* and has the same function. While the latter theory delivers the corporation to its board, the community plant doctrine delivers the workers into the power of the owner.

The community ideology in labor relations is one of the worst and one of the most significant of the heritages from the Republic. Section 615 of the imperial civil code had provided that every employee who offered his labor to an employer must receive wages even when the latter was unable to let him work either because of technical mishaps in the factory or because of economic conditions or a strike in another factory. The legislators argued that the employer, as the owner, had to bear the full risk involved in the operation of his enterprise. The federal supreme court reversed this statutory provision in 1921. It argued that the establishment of works councils had created a plant community in which the employee was a ‘living link’ and therefore had to share the risks.20 Lower courts were advised to examine the equity in each specific case. If the disturbance is caused by strikes, for example, the employer is not obligated to pay wages even if the stoppage occurs in a wholly unrelated enterprise.

The so-called plant community was a very strange community even during the Republic. It was a community of losses but never of profits. Neither during the Republic nor after has a single court reached the logical conclusion that higher profits must automatically lead to higher wages. The plant-community theory was nothing but an anti-democratic doctrine by which the judiciary sabotaged progressive labor legislation.

Leadership in labor relations has a different meaning and function from leadership in politics or business. All political leaders are chosen from above. The employer is the leader of the plant simply because he is the owner or manager. Ownership of the means of production automatically means authoritarian control over the workers, and the ‘community’ thus established is comparable to a barracks. Section 2 of the National Socialist charter of labor makes that unmistakably clear:

‘The leader of the plant decides as against the followers in all matters pertaining to the plant in so far as they are regulated by statute.

‘He shall look after the well-being of the followers, while the latter shall keep faith with him, based on the plant community.’

All the attempts of the National Socialist legal experts to supplant the labor contract by a community theory have failed. They have been unable to find a legal basis for labor relations that will not resemble the condemned liberal, Romanistic, and materialistic individual labor contract. In despair the leading commentator has accepted the conclusion that the labor contract is essential for the establishment of the community.21 The language of the community ideology remains—and the burdens upon the employee have been increased considerably.

The duty of the employer to look after the welfare of his workers is no innovation of National Socialism. It was stated in sections 616-18 of the civil code of 1900, based upon the insight that the labor contract is not a pure exchange relation but is a power contract placing one man under the sway of another. Power entails duties—that much was clear to the framers of the ‘materialistic’ and ‘Romanistic’ civil code. The obligation of the employer to prevent accidents and to look after the health and security of his employees does not follow from an alleged community, but from the fact that the owner controls the means of production. The community ideology of the National Socialists has added nothing here. I have been unable to find a single decision by the supreme labor court that substantially improves the protection of the worker by invoking the community ideology.22 But I have found innumerable instances in which the new theory has been used to deprive workers and salaried employees of the remnants of those rights which the rational character of the individual labor agreement had granted to them.

The essence of rational law consists in clearly defining and delimiting rights and duties. Such rationality has been almost completely destroyed. In a liberal society the worker sells his labor power for a given time, place, performance, and price. Under National Socialism all limitations have disappeared unless defined by statute, or by the regulation of the trustee of labor, or by a plant regulation.* In the unanimous view of National Socialist lawyers, the new theory that the worker owes faith means that he is obliged to accept any work the employer demands within reason, whether previously agreed upon or not; that he must work at any place the employer determines within reason, whether previously agreed upon or not; that he must accept any wages that the employer equitably fixes, unless they are fixed in trustee or plant regulations.23

In sum, the community and leadership theory in labor relations uses a medieval terminology to conceal the complete surrender of the rights of the workers by the destruction of the rationality of the individual labor contract. How completely the ideology contradicts reality becomes still clearer when we remember the discussions of the control of the labor market.† Compulsory repatriation, compulsory training, and deportation are hardly devices to awaken a plant community spirit. The textile workers or the retail employees who are carted off in trucks and freight trains to distant parts of the grossdeutsche Reich and then forced into new occupations cannot possibly develop a plant community feeling.

Through the works councils, the Weimar democracy permitted workers to choose plant representatives in secret competitive elections. National Socialism has suppressed the works councils and replaced them by the so-called councils of confidence, chosen in typical National Socialist fashion. The leader of the plant (that is, the employer or his manager) jointly with the chairman of the NSBO cell names the slate (two to ten members according to the size of the plant) and every March the employees approve or reject it in so-called elections. No other slate is admitted, of course. The council, furthermore, is a ‘leader council,’24 and section 6 of the charter of labor defines that term to mean that it is directed by the employer. The duty of the council is to ‘deepen the mutual trust within the plant community’; to discuss measures ‘pertaining to the improvement of efficiency’ and to the creation and execution of the general conditions of labor; to concern itself with the protection of the workers and the settlement of disputes. A councilman may be deposed by the trustee of labor but can be dismissed from his regular job only if the plant closes or if his labor contract is terminated for an important reason. If an employer owns several plants belonging to the same technical or economic unit and if he himself does not manage all of them, he must set up an enterprise council from among the members of the various plant councils to advise him in matters of social policy.

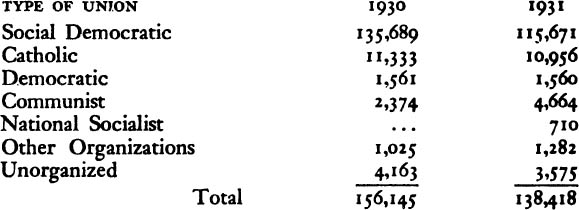

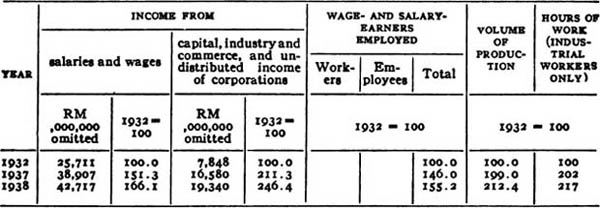

The almost complete control of the Labor Front (assisted by the plant troops) and the employer over the composition of the ‘council of confidence’ would seem to guarantee against their becoming centers of opposition. In many cases, however, the councils were apparently dominated by old trade unionists and did become spearheads of opposition. National Socialism has not been able to conquer the manual worker or even the entire group of the salaried employees. To evaluate the sentiment of the Weimar working classes, particular attention should be given to the works-council elections. They are perhaps even more important than the parliamentary elections, for in choosing the council the workers based their decision almost exclusively upon actual social experience. The composition of the works councils in 1930 and 1931 is striking—not a single National Socialist in 1930 and only 710 out of 138,000 as late as 1931:

Composition of Works Councils for Manual Workers in 1930 and 1931

(Reported by the Socialist Trade Union ADGB)25

When broken down properly, the parliamentary election figures show the same thing. In the election of 31 July 1932, when the National Socialist party achieved its biggest parliamentary victory under democratic conditions, the Social Democrats and Communists received 13,241,000 votes. There were about 18,267,000 manual and white-collar workers in Germany at that time. Although the left-wing voters were not all workers, the bulk was. This can be shown by comparing the results in a mixed industrial and agricultural district with a considerable Catholic minority (Hessen-Nassau), a highly industrialized and predominantly Protestant district (Saxony), a mainly agrarian and predominantly Protestant district (East Prussia), and a predominantly Catholic, agrarian district (Baden).26 We may safely conclude that about 65 per cent of the workers and salaried employees voted for the Social Democratic and Communist parties in the middle of 1932. Even in the election of 5 March 1933, when the Communist party was illegal and the Social Democratic press completely suppressed, the two parties together mustered 30.6 per cent of the votes; the Catholic Center, 11.2; the Nationalists, 8.0; the Peoples party, 1.1; the Bavarian Peoples party, 2.7; and the National Socialists 43.9 per cent.

The National Socialist regime published official statistics of the elections to the councils of confidence, but they do not reveal the true results. We have a simple but sure indication of the results, however—there have been no elections since March 1936.27 The terms of the existing councilmen have been extended year by year and the replacements are appointed by the trustees of labor. In other words, the workers have not even the shadow of plant representation, despite fine words in the charter of labor. The councils of confidence are mere tools of the plant troops and the Labor Front. They are used to terrorize both the workers and the employer and to increase efficiency. The articulation of opposition and criticism is impossible.

The process of isolating the worker and terrorizing him is carried still further by stretching the concept of treason. Any document, drawing, other object or ‘fact or news about them’ may be considered a state secret according to the penal code. Betrayal of such information to a third person, not necessarily a foreign government, constitutes treason to the country. Even preparation for betrayal is punishable by death, unintentional betrayal by imprisonment up to three years. Since most plants are engaged in war work in a preparedness and war economy, virtually all plant secrets become state secrets and the threat of imprisonment, the concentration camp, or death hangs over most workers and their families. The isolation of the worker is completed. Nor is that all. The war economy decree of 4 September 1939 orders imprisonment or death for anyone ‘who destroys, puts aside, or retains raw material or products that belong to the vital needs of the people and thereby maliciously endangers the satisfaction of these needs’ (Section 1).28 Penal legislation has been tightened and special courts have been created.

We must come to the conclusion that community theory, plant leadership, councils of confidence, Labor Front, and plant troops have but one function: They are devices for the manipulation of the working classes, for the establishment of an authoritarian control, for the destruction of the natural differences created by work, training, and occupation, for the isolation of each individual worker from his family, and for the creation of élites. It is not merely the requirements of war that are responsible; it is the very structure of labor and other social relations.

Entrepreneurs and managers who belong to groups and chambers, so the decree says, are duty bound to be decent and honorable in their economic activities. Gross violation is punishable by a warning, reprimand, or fine, or by loss of the right to hold office in the groups and chambers, penalties that do not hurt the entrepreneur economically but merely in his political status. Special disciplinary courts have been set up for each provincial economic chamber and one federal appeal court. They are peer courts, composed of two entrepreneurs or managers and a chairman appointed by the minister of economics upon recommendation of the president of the national economic chamber (the appellate court has four entrepreneurs or managers and a chairman).29

The contrast with the social courts of honor in labor relations is strikingly revealing. According to the Charter of Labor, each ‘member of the plant community bears the responsibility for the conscientious fulfilment’ of the community duties. Employers are guilty of violating the social honor if they ‘maliciously misuse their power position in the factory to exploit the labor power of the followers or to injure their honor.’ Employees are punishable when they ‘endanger the labor peace by malicious sedition of the followers’; when councilmen consciously arrogate to themselves the right of illegal interference in management; when they disturb the community spirit; when they ‘repeatedly make frivolous appeals . . . to the trustee of labor or strenuously violate his orders’; or when they betray plant secrets. Employers may be punished by a warning, a reprimand, a fine up to 10,000 marks, or loss of the right to be plant leaders. The maximum penalty for the employee is dismissal.

The social honor courts are not peer courts. The provincial courts are composed of a judge, appointed jointly by the ministries of labor and justice, and a plant leader and councilman selected from lists prepared by the Labor Front. The federal appellate court has three judges, a plant leader, and one councilman. The influence of the workers is non-existent. Their punishment is much more severe, for dismissal threatens their means of existence, whereas the maximum employer’s penalty, loss of plant leadership, leaves ownership untouched. The federal honor court has further ruled that an employer may be deprived of plant leadership for a limited time only and only for one plant if he has several.30

Actually, this particular judicial machinery has been little more than an ornament. In 1937, 342 charges were filed, 232 in 1938, and only 142 in 1939. The 156 trials in 1939 were distributed as follows:31

against plant leaders, 119

deputies, 1

superintendents, 19

followers, 14

Lest the disproportionate number of employers and foremen tried by the honor courts be misleading, a further breakdown of these trials is necessary:

against handicraft plants, 32

agrarian enterprises, 32

industrial plants, 12

retailers, 9

transportation firms, 4

innkeepers and restaurant owners, 11

building firms, 16

others, 4

The overwhelming majority are obviously small businessmen. They are always the violators of labor legislation, not because they are especially malicious but because big plants are far more able to digest the burden of social reform. Only in seven cases, finally, were plant leaders actually deprived of their right to be plant leaders.

There were about 20,000,000 manual and white-color workers employed in 1939, and only 14 cases against ‘followers.’ That seems astounding, but the explanation is simple and significant. The terroristic machinery is far tighter and far more complete against the follower than against any other stratum in society. Why should the police, the Labor Front, or the employer initiate a cumbersome procedure before the honor courts when much cheaper, swifter, and more efficient means are available? There is the army service, the labor service, protective custody (a polite word for the concentration camp) requiring no procedure whatsoever, and, in emergency, the special criminal courts, which can render decisions within twenty-four hours. In so far as the social honor courts have any function, in other words, it is to reprimand an occasional offense by a small businessman and thus demonstrate to labor the social consciousness of the regime.

As for the labor law courts, the outstanding contribution of the Republic to rational labor relations, they remain in existence with hardly a change in structure.32 Like every court, however, they have lost most of their functions. Since there are no collective agreements, there can be no law suits between trade unions and employers’ organizations. There are no more works councils and so there can be no disputes between councils and employers. Only individual disputes between employee and employer remain. And since it is a major task of the legal-aid departments of the Labor Front to negotiate settlements, in fact no law suit can be brought before the courts without the consent of the Labor Front. When the Front does consent, it acts as counsel for both parties and has the sole decision whether or not to admit attorneys.33

The exclusion of professional attorneys from labor cases began under the Republic as a progressive step. The employee had either to act for himself or employ a trade-union secretary as counsel. The ensuing union monopoly of legal representation in the courts of first instance undoubtedly influenced workers to join unions (the closed shop did not exist), though they retained a choice between competing unions, and if they remained unorganized they often enjoyed the benefits of the collective agreements concluded between trade unions and employers’ organizations. Today, the monopolization of legal aid by an authoritarian body leads to complete annihilation of the remnants of labor rights.

While liberal theories, and especially the utilitarian, hold that work is pain and leisure is pleasure, in modern society leisure is almost completely devoted to reproducing the strength consumed in the labor process. And in mass democracy, leisure has come under the full control of monopolistic powers. The major forms of entertainment—the radio, the cinema, the pulp magazine, and sports-are all controlled by financial interests. They are standardized in the selection and treatment of topics, and in the allocation of time.

Under democratic conditions, however, the family, the church, and the trade union continue to provide other incentives, diametrically opposed to the prevailing conditions of life—of labor and leisure. Such progressive trends were clearly apparent in the leisure-time activities of the German labor movement, both Catholic and Social Democratic. Unfortunately a conflicting trend was equally manifest—envy of petty-bourgeois culture and a desire to imitate it, and its worst elements at that. In the field of labor education, for example, the program of the central trade-union body, the ADGB, was geared primarily to romantic, petty-bourgeois incentives. It is not surprising therefore that nearly all ex-teachers in the ADGB school are now National Socialists; some of them were actually secret members of the National Socialist party as far back as 1931. The educational program of many of the affiliated unions, on the other hand, led by the metal-workers union, was diametrically opposed. For this group, education and leisure activities were designed to make men critical of the existing labor process. The conflict between the two principles within the workers’ education movement was never solved.

The same situation prevailed in the other cultural activities of the labor movement. Some of the trade-union book guilds, theater guilds, and radio guilds were experimental. They did not consider leisure merely as the basis for reproducing labor power or culture simply as mass culture. Here too there were conflicts and a resulting instability. Nevertheless the German workers’ educational and cultural groups retained a marked vitality. In both Catholic and non-Catholic circles they were the most powerful antidotes against a standardized mass culture dictated by private monopoly. As time went on, the leisure policy of the unions aimed more and more at changing the conditions of labor rather than at relaxation and the regaining of bodily strength for greater efficiency.

Free leisure is incompatible with National Socialism. It would leave too great a part of man’s life uncontrolled. ‘Of 8760 hours a year, only 2100 hours (24 per cent) are work hours, and 6660 are leisure. Even if we deduct 8 hours a day for sleep from this leisure time, there still remains an actual leisure time of 3740 hours a year.’34 This is the official arithmetic of the Labor Front.

National Socialist theory of the relation between labor and leisure has been worked out fully. One example will serve for analysis—the vocational training of apprentices. A preliminary word of warning: The official statements of the Labor Front addressed to the workers betray considerable uneasiness on the question of leisure. Leisure is not merely a preparation for labor, they say; the two are not oppo-sites but interrelated. ‘Economic, social and cultural policy will have to work for this aim: that in the future one need no longer speak of the “working life of the people” but of racial life as such.’35 In publications and communications addressed to professional educators and organizers, the language is very different. The leading expert on the social policy of the Labor Front writes: ‘To win strength for daily work was therefore the final goal toward which the new creation strove. Thus the leisure organization “After Work” became the National Socialist community, Strength through Joy.’36

The co-ordinator of all vocational training in the Reich is K. Arnhold.37 At the founding of the Dinta, the German Institute for Technical Work Training,38 in 1925, Arnhold, its director, announced its aim to be to take ‘leadership of all from earliest childhood to the oldest man, not for social purposes—and I must emphasize this once more—but from the point of view of productivity. I consider man the most important factor which industry must nourish and lead.’39 During the Republic, the Dinta, run by the most reactionary of German psychologists and sociologists, was the inveterate foe of trade unionism of any kind. It promoted company unions and they in turn compelled industrial apprentices to attend the Dinta schools. The Dinta has been taken over by the Labor Front and is now called the German Institute for National Socialist Technical Work Training. By the end of 1936 there were 400 apprentice training centers in existence and 150 more under construction. There were 113 Dinta plant newspapers with a combined circulation of 1,500,000 as compared with 95 Labor Front plant publications with a circulation of only 350,000.40 (There are also other Labor Front papers published for whole branches of industry or for the whole Labor Front.)

The work of the Dinta is supplemented by the Federal Institute for Vocational Training in Trade and Handicraft and by a number of scientific institutes attached to industrial combines. The latter may be exemplified by the Siemens Society for Applied Psychology, attached to the most powerful German electrical combine. Its publication formulates our problem this way: ‘It is true that there is a marked separation . . . between labor and leisure . . . Man often uses . . . leisure for creative work . . . in the garden and for personal education. Fully recognizing the ardor and energy [of such endeavors] . . . it must be pointed out, however, that the most important aim of leisure is relaxation for the collection of strength.’ ‘It is impossible to shift the essence of our existence from the realm of labor to another realm.’41 Education must therefore be education for work. ‘The concept of duty must be known even to the ABCdarian.’42

The reduction of leisure to a mere auxiliary of work is the official leisure philosophy of National Socialism. It is all the more brutal because it coalesces with the National Socialist principle of social organization: drive the workers into huge organizations where they are submerged; lose their individuality, march, sing, and hike together but never think together. The Labor Front thus takes particular pride in one achievement of its Strength through Joy organizations; the yearly efficiency competition among boys and girls (in 1936, there were 720 professions with 1,500,000 participants; in 1937, there were 1,800,000 participants). Plants developing the most successful vocational-training institutes receive from Dr. Ley an efficiency medal. The design is a cog-wheel enclosing a swastika above a hammer with the initials DAF (German Labor Front) and below the words ‘recognized vocational training plant.’43

Strength through Joy makes full use of the findings of applied psychology to prescribe in detail the correct methods, time, and content of leisure for the one aim of enhancing the worker’s productivity. The same purpose is served by the Beauty of Labor department of the Labor Front, whose function is to beautify factories and canteens. These organizations have of course given material benefits to many working-class groups. But much as glee clubs, orchestras, and baseball teams may improve the lot of prisoners, they do not tear down the bars.

The wage policy serves the same purpose of controlling and isolating man as the social policy. National Socialism is built on full employment. That is its sole gift to the masses, and its significance must not be underestimated. The business cycle has not been brought to an end, of course, nor has the economic system been freed from periods of contraction. But state control over credit, money, and the labor market prevents slumps from taking the form of large-scale unemployment. Even if production should sag after the war and the inherent contradictions of monopoly capitalism should make it impossible to direct the flow of capital back into consumers goods, there will probably be no mass dismissals. Women will be sent back to the kitchen and invalids to their pensions. Over-age workers will be compulsorily retired on meager old-age grants. War prisoners and foreign workers will be repatriated. If necessary, the work will be distributed and labor time shortened, technical progress stopped or even reversed, wages lowered and prices raised. There are dozens of such devices available in an authoritarian regime. The crucial point is that unemployment must be prevented so as to retain this one link that still ties the masses to its ruling ciass.

Full employment is accompanied by an elaborate social-security program. The system developed by the Weimar democracy has been streamlined and brought under authoritarian control. Unemployment assistance, health and accident insurance, invalidity and old-age pensions—that is how National Socialism wins the passive toleration of the masses for the time being. Social security is its one propaganda slogan built on the truth, perhaps the one powerful weapon in its whole propagandistic machinery.

The wage policy of the Weimar Socialist trade unions was aimed at increasing the workers’ share of the national income and at achieving a class wage. They sought to level wage differentials among unskilled, semi-skilled, and skilled workers in each branch of industry and within the economy as a whole. Even apprentices were included. Apprenticeship was transformed into a genuine labor contract, with genuine wages. The trade-union movement was hostile to such devices as family allowances, both because they might drive out the married man with dependants and because they conflicted with the class wage theory. Employers fought union policy bitterly. They tried deliberately to play off a labor aristocracy against the plebeians by granting concessions to the skilled workers and by extending special treatment to salaried employees.

Full employment and social security have been achieved by National Socialism at the expense of wage rates and hence of the standard of living of the masses, or at least of those who did not face unemployment during the Republic. Wages are cost elements. They are the basis for an adequate reproduction of labor power and a device for distributing workers among the various branches of trade and industry. The class wage of the Socialist trade unions has been replaced by the ‘performance wage’ (Leistungslohn) defined in Section 29 of the Charter of Labor.44 ‘It has been the iron principle of the National Socialist leadership,’ said Hitler at the Party Congress of Honor, ‘not to permit any rise in the hourly wage rates but to raise income solely by an increase in performance.’ The rule of the wage policy is a marked preference for piece work and bonuses, even for juvenile workers.45 Such a policy is completely demoralizing, for it appeals to the most egotistic instincts and sharply increases industrial accidents.

Apprentices have lost their status as workers and their contract is no longer a labor contract but an ‘educational agreement.’ The federal supreme labor court has therefore held that the apprentice is not entitled to overtime pay nor may the employer make pay deductions for lost time.46 (The latter is no problem in a period of full employment anyway.) The power of the trustees of labor has been extended by the war economy decree of 4 September 1939, so that they may now not only issue tariff regulations for whole branches of industry but also specific regulations for each plant and even for subdivisions of a plant without regard to existing obligations.47 Two decades of progress have been wiped out completely.

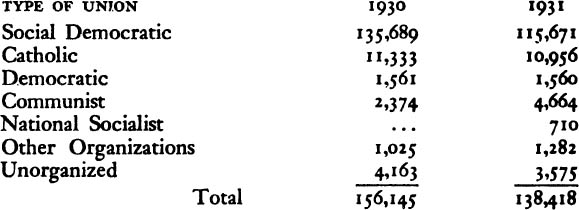

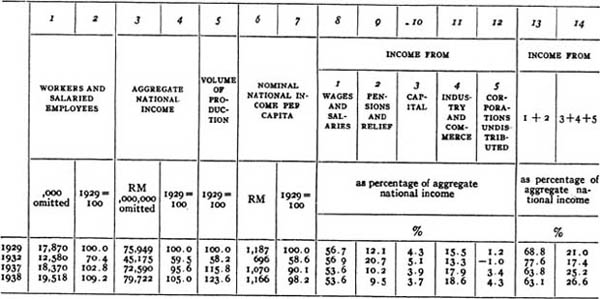

The preponderance of the performance wage brings the problem of wage differentials into the forefront of social policy. It is essential that this problem be understood not as an economic question but as the crucial political problem of mass control. Official wage statistics say nothing about it, but there is ample proof that the process of differentiation is in full swing.* Hourly wage rates reveal nothing about the process of differentiation48 in a system that relies largely upon the performance wage. The indices of income from work49 show that despite the stability of differentials in the hourly wage rates, the gap between actual earnings of skilled and semi-skilled workers has widened noticeably. The trend would become even clearer if the figures included the unskilled, for that group of wage earners has increased most. Within each of the three groups, furthermore, there is a great variety of differences.50

Wage differentiation is the very essence of National Socialist wage policy. That becomes clear from the debate of the past two years preparatory to an expected federal wage decree. ‘The amount of wages is no longer a question of an adequate share of the followership in the plant profits but a problem of incorporating the folk comrade into the racial income order according to his performance for the people’s community.’51 Clearly Dr. Sitzler, once a democratic ministerial director in the ministry of labor and now editor of Soziale Praxis, has learned the language of National Socialism well. He leaves no doubt that the wage policy is consciously aimed at mass manipulation. His successor in the ministry of labor, Mansfeld, who came to his post from an employers’ organization, says flatly that the one problem for National Socialism in this field is to provide a legal basis for the performance wage. In a detailed study, another author proposes no less than seven wage groups, each to be further differentiated according to sex, age, family status, territory, and any other category that will divide the working classes.52