FOR HALF A CENTURY or more, the history of modern Germany pivoted around one central issue: imperialist expansion through war. With the appearance of socialism as an industrial and political movement threatening the established position of industrial, financial, and agricultural wealth, fear of this challenge to imperialism dominated the internal policy of the empire, Bismarck tried to annihilate the socialist movement, partly by enticement and even more by a series of enactments outlawing the Social Democratic party and trade unions (1878-90). He failed. Social Democracy emerged from this struggle stronger than ever. Both Wilhelm I and Wilhelm II1 then sought to undermine the influence of the socialists among the German workers by introducing various social reforms—and also failed.

The attempt to reconcile the working class to the state was carried as far as the ruling forces dared; further efforts in this direction would have meant abandoning the very foundation on which the empire rested—the semi-absolutistic and bureaucratic principles of the regime. Only political concessions to the working classes could bring about a reconciliation. The ruling parties were unwilling, however, to abolish the Prussian three-class franchise system and to establish a responsible parliamentary government in the Reich itself and in the component states. With this recalcitrance, nothing remained for them but a war to the death against socialism as an organized political and industrial movement.

The methods of struggle selected took three basic forms: (1) the re-organization of the Prussian bureaucracy into a stronghold of semi-absolutism; (2) the establishment of the army as a bulwark of monarchical power; and (3) the welding together of the owning classes.

The absence of any liberal manifestation in this program is significant. The liberals had been defeated in Germany in 1812, in 1848, and again in the constitutional conflict of 1862. By the last quarter of the nineteenth century, liberalism had long ceased to be an important, militant political doctrine or movement; it had made its peace with the empire. On theoretical grounds, furthermore, the spokesmen of absolutism rejected liberalism as a useful tool against socialism. Take the doctrine of inalienable rights. What was it but an instrument for the political rise and aggrandizement of the working classes? Rudolph Sohm, the great conservative legal historian, expressed the current conviction this way:

From the circles of the third estate itself there have arisen the ideas which now . . . incite the masses of the fourth estate against the third. What is written in the books of the scholars and educators is nothing other than what is being preached in the streets . . . The education that dominates our society is the one that preaches its destruction. Like the education of the eighteenth century, the present-day education carries the revolution beneath its heart. When it gives birth, the child it has nourished with-its blood will kill its own mother.2

The reorganization of the bureaucracy was undertaken by Robert von Puttkamer, Prussian minister of the interior from 1881 to 1888. Contrary to common belief, the earlier bureaucracy of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was far from conservative and made common cause with the champions of the rising industrial capitalism against feudal privilege. The transformation of the bureaucracy set in when the nobility itself began to participate extensively in capitalist enterprise. In a thorough-going purge, Puttkamer dismissed the ‘unreliable’ elements (including even liberals). The civil service became a closed caste, and the campaign to inject a spirit of thorough conservatism was as successful as in the army. The king was finally able to demand by edict that the ‘civil servants to whom the execution of my governmental acts is entrusted and who,, therefore, can be removed from office by disciplinary action,’ support his candidates in elections.3

Puttkamer brought still another weapon into the fight against socialism. Inspired by the conviction that ‘Prussia is the special favorite of God,’4 he made religion a part of bureaucratic life.5 Bureaucracy and religion together, or rather the secular and clerical bureaucracies, became the primary agencies against socialism. The ideological accompaniment was an unceasing denunciation of materialism and the glorification of philosophical idealism. Thus Heinrich von Treitschke, the outstanding German historian of the period, clothed his eulogies of power, of the state, and of great men in the same language of modern idealism that was being repeated in every university, school, and pulpit. A firm union was cemented between the Conservative party, the Protestant church, and the Prussian civil service.

The second step was the transformation of the army into a solid tool of reaction. Ever since Frederick II of Prussia, the officer corps was drawn predominantly from the nobility, who were supposed to possess the natural qualities of leadership. Frederick II preferred even foreign-born noblemen to Prussian bourgeois, whom he-together with the men serving in his armies—regarded as ‘canaille’ and brutes.6 The Napoleonic Wars shattered this army and demonstrated that troops held together solely by brute discipline were far inferior to the revolutionary armies of France. Under Gneisenau and Scharnhorst, the German army was then reorganized and even democratized to a limited extent, but this development did not last long. In 1860, when Manteuffel had finished his purge, fewer than a thousand of the 2,900 line infantry officers were non-nobles. All the officers’ commissions in the guard cavalry and 95 per cent in the other cavalry and in the better infantry regiments were noblemen.7

Equally important were the adaptation and reconciliation of the army to bourgeois society. In the ‘80s, with the defeat of liberalism among the bourgeoisie and the rising threat of the socialist movement, the bourgeoisie abandoned its earlier opposition to the army-extension program. An alliance developed between the two former enemies and the ‘feudal bourgeois’ type appeared on the scene. The institutional medium for this new type was the reserve officer, drawn largely from the lower middle classes to meet the tremendous personnel problem created by the increase of the army to a war strength of 1,200,000 in 1888 and 2,000,000 (3.4 per cent of the total population) in 1902. The new ‘feudal bourgeois’8 had all the conceit of the old feudal lord, with few of his virtues, little of his regard for loyalty or culture. He represented a coalition of the army, the bureaucracy, and the owners of the large estates and factories for the joint exploitation of the state.

In France during the nineteenth century, the army was fused into the bourgeoisie; in Germany, on the contrary, society was fused into the army.9 The structural and psychological mechanisms that characterized the army crept steadily into civilian life until they held it in a firm grip.10 The reserve officer was the key actor in this process. Drawn from the ‘educated’ and privileged stratum of society, he replaced the less privileged but more liberal Landwehr officer. (Reactionaries had always distrusted the Landwehr and considered its officers ‘the most important lever for an emancipation of the middle class.’)11 In 1913, when the supply of reserve officers from the privileged strata proved too small for the larger army that had been projected, the Prussian army ministry calmly cancelled its plans for an increase rather than open the doors to ‘democratization’ of the officer corps.12 One lawyer lost his commission in the reserve for defending a liberal in a cause célèbre; so did a mayor who had not stopped a tenant of city property from holding a socialist meeting.13 As for socialists, it was decided that they lacked the necessary moral qualifications to be officers.

The third step was the reconciliation between agrarian and industrial capital. The depression of 1870 had hit agriculture hard Additional difficulties were created by the importation of American grain, the rise of industrial prices,14 and Chancellor Caprivi’s whole trade policy, which was dominated by a desire to keep agrarian prices low. Driven to the point of desperation, the agrarians organized the Bund der Landwirte in 1893 and began a fight for protective tariffs on grain,15 arousing the resentment of industrial capital.

A historic deal put an end to the conflict.* The industrial groups were pushing a big navy program and the agrarians, who had been either hostile or indifferent before, agreed through their main agency, the Prussian Conservative party, to vote for the navy bill in return for the industrialists’ support for the protective tariff. The policy of amalgamating all the decisive capitalist forces was finally completed under the leadership of Johannes von Miquel, who, first as leader of the National Liberals in 1884 and later as Prussian minister of finance from 1890 to 1901, swung the right wing majority of his party behind Bismarck’s policies and inaugurated his famous Sammlungspolitik, the concentration of all ‘patriotic forces’ against the Social Democracy. The Sammlungspolitik received its supreme expression in the direct coupling of grain tariffs with naval construction in 1900. The National Liberals, the Catholic Center, and the Conservative party had arrived at a common material basis.

The conclusion and aftermath of the First World War soon showed that the union of reaction was too fragile a structure. There was no universally accepted ideology to hold it together (nor was there a loyal opposition in the form of a militant liberal movement). It is strikingly evident that Imperial Germany was the one great power without any accepted theory of the state. Where was the seat of sovereignty, for example? The Reichstag was not a parliamentary institution. It could compel neither the appointment nor the dismissal of cabinet ministers. Only indirectly could it exert political influence, especially after Bismarck’s dismissal, but never more than that. The constitutional position of the Prussian parliament was still worse; with the help of his specially devised ‘theory of the constitutional gap,’ Bismarck had even been able to get along without parliamentary sanction for his budgets.

The sovereign power of the empire resided in the emperor and princes assembled in the second chamber (the Bundesrat). The princes derived their authority from the divine right of kings, and this medieval conception—in the absolutistic form it had taken during the seventeenth century—was the best Imperial Germany could offer as its constitutional theory. The trouble, however, was that any constitutional theory is only an illusion unless it is accepted by the majority of the people, or at least by the decisive forces of the society. To most Germans, divine right was a patent absurdity. How could it have been otherwise? In a speech at Königsberg on 25 August, 1910, Wilhelm II made one of his frequent divine-right proclamations. This is what he said:

It was here that the Great Elector made himself sovereign Duke of Prussia by his own right; here his son put the royal crown upon his head . . . Frederick William I here established his authority like a rocher de bronze . . . and here my grandfather again put the royal crown on his head by his own right, definitely stressing once again that it was granted to him by God’s Grace alone and not by parliaments, popular assemblies, and popular decision, and that, therefore, he considered himself a selected instrument of Heaven . . . Considering myself an instrument of the Lord, I go my way . . .

The innumerable jokes and cartoons that appeared deriding this particular restatement of the theory leave little doubt that no political party took it seriously except the Conservatives, and they only to the extent that the emperor identified himself with their class interests. The justification of sovereign power is the key question of constitutional theory, however, and German writers had to avoid it. There was no alternative in a country split along so many lines—Catholic and Protestant, capitalist and proletarian, large land owner and industrialist—and with each so solidly organized into powerful social organizations. Even the most stupid could see that the emperor was far from being the neutral head of the state and that he sided with specific religious, social, and political interests.

Then came the test of a war that called for the greatest sacrifices in blood and energy on the part of the people. The imperial power collapsed and all the forces of reaction abdicated in 1918 without the slightest resistance to the leftward swing of the masses—all this not as the direct consequence of the military defeat, however, but as the result of an ideological debacle. Wilson’s ‘new freedom’ and his fourteen points were the ideological victors, not Great Britain and France. The Germans avidly embraced the ‘new freedom’ with its promise of an era of democracy, freedom, and self-determination in place of absolutism and the bureaucratic machine. Even General Ludendorff, virtual dictator over Germany during the last years of the war, acknowledged the superiority of the Wilsonian democratic ideology over Prussian bureaucratic efficiency. The Conservatives did not fight—in fact, they had nothing with which to fight.

Constitutions written at the great turning points of history always embody decisions about the future structure of society. Furthermore, a constitution is more than its legal text; it is also a myth demanding loyalty to an eternally valid value system. To establish this truth we need only examine characteristic constitutions in the history of modern society, such as the French revolutionary constitutions or the Constitution of the United States. They established the organizational forms of political life and also defined and channelized the aims of the state. This last function was easily accomplished in the liberal era. The charters of liberty, whether they were embodied in the constitution or not, had merely to provide safeguards against encroachment by the constituted authorities. All that was necessary for the free perpetuation of society was to secure freedom of property, of trade and commerce, speech and assembly, religion and the press.

Not so in post-war Germany. The constitution of 1919 was an adaptation of Wilson’s new freedom. Confronted with the task of building a new state and a new society out of the revolution of 1918, however, the framers of the Weimar Republic tried to avoid formulating a new philosophy of life and a new all-embracing and universally accepted value system. Hugo Preuss, the clear-sighted democratic constitutional lawyer who was entrusted with the actual drafting of the constitution, wanted to go so far as to reduce the document to a mere pattern of organization. He was not seconded. The makers of the constitution, influenced by the democrat, Fried-rich Naumann, decided on the opposite course, namely, to give a full elaboration of the democratic value system in the second part of the constitution, to be headed the Fundamental Rights and Duties of the German People.

Simply to take over the tenets of political liberalism was out of the question. The revolution of 1918 had not been the work of the liberals, but of the Socialist parties and trade unions, even though against the will and inclination of the leadership. True, it had not been a socialist revolution: property was not expropriated, the large estates were not subdivided, and the state machine was not destroyed, the bureaucracy was still in power. Nevertheless, working-class demands for a greater share in determining the destiny of the state had to be satisfied.

Class struggle was to be turned into class collaboration—that was the aim of the constitution. In point of fact, the ideology of the Catholic Center party was to become the ideology of Weimar, and the Center party itself, with a membership drawn from the most disparate groups—workers, professionals, civil servants, handicraftsmen, industrialists, and agrarians—was to become the prototype of the new political structure. Compromise among all social and political groups was the essence of the constitution. Antagonistic interests were to be harmonized by the device of a pluralistic political structure, hidden behind the form of parliamentary democracy. Above all, there was to be an end to imperialistic expansion. Republican Germany would find full use for its productive apparatus in an internationally organized division of labor.

The pluralist doctrine was a protest against the theory and practice of state sovereignty. The theory of the sovereign state has broken down’ and must be abandoned.16 Pluralism conceives of the state not as a sovereign unit set apart from and above society, but as one social agency among many, with no more authority than the churches, trade unions, political parties, or occupational and economic groups.17 The theory originated in Otto von Gierke’s interpretation of German legal history, fused in a curious combination with reformist syndicalism (Proudhon) and the social teachings of neo-Thomism. Against a hostile sovereign state, the trade unions and the churches demanded recognition of their assertedly original, non-delegated right to represent autonomous groups of the population. ‘We see the state less as an association of individuals in a common life; we see it more as an association of individuals, already united in various groups for a further and more embracing common purpose.’18

Underlying the pluralist principle was the uneasiness of the impotent individual in the face of a too-powerful state machine. As life becomes more and more complicated and the tasks assumed by the state grow in number, the isolated individual increases his protests against being delivered up to forces he can neither understand nor control. He joins independent organizations. By entrusting decisive administrative tasks to these private bodies, the pluralists hoped to accomplish two things: to bridge the gap between the state and individual, and give reality to the democratic identity between the ruler and the ruled. And, by placing administrative tasks in the hands of competent organizations, to achieve maximum efficiency.

Pluralism is thus the reply of individual liberalism to state absolutism. Unfortunately, it does not accomplish its self-imposed tasks. Once the state is reduced to just another social agency and deprived of its supreme coercive power, only a compact among the dominant independent social bodies within the community will be able to offer concrete satisfaction to the common interests. For such agreements to be made and honored, there must be some fundamental basis of understanding among the social groups involved, in short, the society must be basically harmonious. However, since the fact is that society is antagonistic, the pluralist doctrine will break down sooner or later. Either one social group will arrogate the sovereign power to itself, or, if the various groups paralyze and neutralize one another, the state bureaucracy will become all-powerful—more so than ever before because it will require far stronger coercive devices against strong social groups than it previously needed to control isolated, unorganized individuals.

The compact that is the basic device of pluralism must be understood in a literal sense. The Weimar Democracy owed its existence to a set of contracts between groups, each specifying important decisions on the structure of the state and public policy.

1. On 10 November 1918, Field Marshal von Hindenburg, who had supervised the demobilization of the army, and Fritz Ebert, then leader of the Social Democratic party and later the first president of the Republic, entered into an agreement the general terms of which were not divulged until some years later. Ebert is quoted as having said afterwards: ‘We allied ourselves in order to fight Bolshevism. The restoration of the monarchy was unthinkable. Our aim on 10 November was to introduce as soon as possible an orderly government supported by the army and the National Assembly. I advised the Field Marshal not to fight the revolution . . . I proposed to him that the supreme army command make an alliance with the Social Democratic party solely to restore an orderly government with the help of the supreme army command. The parties of the right had completely vanished.’19 Although it was consummated without the knowledge of Ebert’s party or even of his closest collaborators, this understanding was in full accord with the Social Democratic party’s policy. It covered two points: one negative, the fight against bolshevism; the other positive, the early convening of a national assembly.

2. Nothing was said in the Hindenburg-Ebert agreement about the social structure of the new democracy. That was covered by the Stinnes-Legien agreement of 15 November 1918, establishing a central working committee between employers and employees. Stinnes, representing the former, and Legien, the leader of the Socialist trade unions, agreed on the following points. Henceforth, employers would withdraw all support from ‘yellow dog’ organizations and would recognize only independent trade unions. They accepted the collective-bargaining agreement as the means for regulating wages and labor conditions and promised to co-operate with the trade unions generally in industrial matters. There could hardly have been a more truly pluralist document than this agreement between private groups, establishing as the future structure of German labor relations a collectivist system set up and controlled by autonomous groups.

3. The agreement of 22 and 23 March 1919 between the government, the Social Democratic party, and leading party officials contained the following provision:

There shall be legally regulated workers’ representation to supervise production, distribution, and the economic life of the nation, to inspect socialized enterprises, and to contribute toward bringing about nationalization. A law providing for such representation shall be passed as soon as possible. It must make provision for the election of Industrial Workmen’s and Employee’s Councils, which will be expected to collaborate on an equal footing in the regulation of labor conditions as a whole. Further provision must be made for district labor councils and a Reich labor council, which, in conjunction with the representatives of all other producers, are to give their opinion as experts before any law is promulgated concerning economic and social questions. They may themselves suggest laws of this kind. The provisions outlined shall be included in the Constitution of the German Republic.

Article 165 of the constitution did then incorporate the provisions of this joint resolution, but nothing was done to carry out the promise except for the 1920 law establishing the works councils.*

4. The relation between the Reich and the various states was fixed by an agreement of 26 January 1919. The dream of German unification was abandoned, as was Hugo Preuss’s demand for the dismemberment of Prussia as the first step in the unification of Germany. The federative principle was again made part of the constitution, though in a milder form than before.

5. Finally, all earlier agreements were blanketed by an understanding among the parties of the Weimar coalition: the Social Democrats, the Catholic Center, and the Democrats. This understanding included a joint decision to convene a national assembly as early as possible, to accept the existing status of the bureaucracy and of the churches, to safeguard the independence of the judiciary, and to distribute power among the various strata of the German people as later set forth in that section of the constitution devoted to the Fundamental Rights and Duties of the German People.

When it was finally adopted, the constitution was thus primarily a codification of agreements already made among different sociopolitical groupings, each of which had demanded and received some measure of recognition for its special interests.

The main pillars of the pluralistic system were the Social Democratic party and the trade unions. They alone in post-war Germany could have swung the great masses of the people over to democracy; not only the workers but also the middle classes, the section of the population that suffered most from the process of monopolization.

Other strata reacted to the complex post-war and post-revolution situation exactly as one would have expected. The big estate owners pursued a reactionary policy in every field. Monopolistic industry hated and fought the trade unions and the political system that gave the unions their status. The army used every available means to strengthen chauvinistic nationalism in order to restore itself to its former greatness. The judiciary invariably sided with the right and the civil services supported counter-revolutionary movements. Yet the Social Democracy was unable to organize either the whole of the working class or the middle classes. It lost sections of the former and never won a real foothold with the latter. The Social Democrats lacked a consistent theory, competent leadership, and freedom of action. Unwittingly, they strengthened the monopolistic trends in German industry, and, placing complete reliance on formalistic legality, they were unable to root out the reactionary elements in the judiciary and civil service or limit the army to its proper constitutional role.

The strong man of the Social Democratic party, Otto Braun, Prussian prime minister until 20 June 1932 when he was deposed by the Hindenburg-Papen coup d’état, attributes the failure of the party and Hitler’s successful seizure of power to a combination of Versailles and Moscow.20 This defense is neither accurate nor particularly skilful. The Versailles Treaty naturally furnished excellent propaganda material against democracy in general and against the Social Democratic party in particular, and the Communist party unquestionably made inroads among Social Democrats. Neither was primarily responsible for the fall of the Republic, however. Besides, what if Versailles and Moscow had been the two major factors in the making of National Socialism? Would it not have been the task of a great democratic leadership to make the democracy work in spite of and against Moscow and Versailles? That the Social Democratic party failed remains the crucial fact, regardless of any official explanation. It failed because it did not see that the central problem was the imperialism of German monopoly capital, becoming ever more urgent with the continued growth of the process of monopolization. The more monopoly grew, the more incompatible it became with the political democracy.

One of Thorstein Veblen’s many great contributions was to draw attention to those specific characteristics of German imperialism that arose from its position as a late-comer in the struggle for the world market.

The German captains of industry who came to take the discretional management in the new era were fortunate enough not to have matriculated from the training school of a county town based on a retail business in speculative real estate and political jobbery . . . They came under the selective test for fitness in the aggressive conduct of industrial enterprise . . . The country being at the same time in the main . . . not committed to antiquated sites and routes for its industrial plants, the men who exercised discretion were free to choose with an eye single to the mechanized expediency of locations . . . Having no obsolescent equipment and no out of date trade connections to cloud the issue, they were also free to take over the processes at their best and highest efficiency.21

The efficient and powerfully organized German system of our time was born under the stimulus of a series of factors brought into the forefront by the First World War. The inflation of the early ’20s permitted unscrupulous entrepreneurs to build up giant economic empires at the expense of the middle and working classes. The prototype was the Stinnes empire and it is at least symbolic that Hugo Stinnes was the most inveterate enemy of democracy and of Rathenau’s foreign policy. Foreign loans that flowed into Germany after 1924 gave German industry the liquid capital needed to rationalize and enlarge their plants. Even the huge social-welfare program promoted by the Social Democracy indirectly strengthened the centralization and concentration of industry, since big business could far more easily assume the burden than the small or middle entrepreneur. Trusts, combines, and cartels covered the whole economy with a network of authoritarian organizations. Employers’ organizations controlled the labor market, and big business lobbies aimed at placing the legislative, administrative, and judicial machinery at the service of monopoly capital.

In Germany there was never anything like the popular anti-monopoly movement of the United States under Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson. Industry and finance were of course firmly convinced that the cartel and trust represented the highest forms of economic organization. The independent middle class was not articulate in its opposition, except against department stores and chains. Though the middle class belonged to powerful pressure groups, like the Federal Union of German Industries,* big business leaders were invariably their spokesmen.

Labor was not at all hostile to the process of trustification. The Communists regarded monopoly as an inevitable stage in the development of capitalism and hence considered it futile to fight capital concentration rather than the system itself. Ironically enough, the policy of the reformist wing of the labor movement was not significantly different in effect.22 The Social Democrats and the trade unions also regarded concentration as inevitable, and, they added, as a higher form of capitalist organization. Their leading theorist, Rudolf Hilferding, summarized the position at the party’s 1927 convention: ‘Organized capitalism means replacing free competition by the social principle of planned production. The task of the present Social Democratic generation is to invoke state aid in translating this economy, organized and directed by the capitalists, into an economy directed by the democratic state.’23 By economic democracy, the Social Democratic party meant a larger share in controlling the monopolist organizations and better protection for the workers against the ill effects of concentration.

The largest trusts in German history were formed during the Weimar Republic. The merger in 1926 of four large steel companies in western Germany resulted in the formation of the Vereinigte Stahlwerke (the United Steel Works). The Vereinigte Oberschlesische Hüttenwerke (the United Upper Silesian Mills) was a similar combination among the steel industries of Upper Silesia. The I. G. Farbenindustrie (the German Dye Trust) arose in 1925 through the merger of the six largest corporations in this field, all of which had previously been combined in a pool. In 1930 the capital stock of the Dye Trust totaled 1,100,000,000 marks and the number of workers it employed reached 100,000.

At no time in the Republic (not even in the boom year of 1929) were the productive capacities of German industry fully, or even adequately, utilized.24 The situation was worst in heavy industry, especially in coal and steel, the very fields that had furnished the industrial leadership during the empire and that still dominated the essential business organizations. With the great depression, the gap between actual production and capacity took on such dangerous proportions that governmental assistance became imperative. Cartels and tariffs were resorted to along with subsidies in the form of direct grants, loans, and low interest rates.25 These measures helped but at the same time they intensified another threat. The framework of the German government was still a parliamentary democracy after all, and what if movements threatening the established monopolistic structure should arise within the mass organizations? As far back as November 1923, public pressure had forced the Stresemann cabinet to, enact a cartel decree authorizing the government to dissolve cartels and to attack monopolistic positions generally.* Not once were these powers utilized, but the danger to privileges inherent in political democracy remained and obviously became more acute in times of great crisis.

The whole process of rationalization, concentration, and bureaucratization had serious repercussions on the social structure. Certainly one of the most significant was the serious weakening of the power of the trade unions, best illustrated by the decline of the strike. The strike weapon has its greatest effectiveness in a period of comparatively free competition, for the individual employer’s power of resistance is relatively low. It becomes more difficult to strike successfully as monopolies develop and the strength of employers’ organizations grows, and still more so when monopolies reach the scale of international cartels, as in steel. Even stoppage of production on a nation-wide scale can be compensated by the cartel. These are rules of general application.

The pluralism of Weimar led to additional factors in Germany. Growing state intervention in business enterprises gave labor disputes the taint of strikes against the state, while governmental regulation led many workers to consider it unnecessary to join unions. The unions for their part were not eager to fight a state in which they had so much at stake. Above all, monopoly was making major—and for the unions deleterious—changes in the social stratification. The increasing percentage of unskilled and semi-skilled workers (and particularly of women workers); the steady increase in foremen and supervisory personnel; the rise in the number of salaried employees in office positions and in the growing distribution apparatus, many organized in non-socialist unions with a middle-class ideology26—all these factors weakened the trade-union movement. The great crisis made matters worse, first because of the tremendous decline in production and the creation of large masses of unemployed, and secondly because the accompanying political tension tended to make every strike a political strike,* which the trade unions flatly opposed because of their theories of revisionism and ‘economic democracy.’

The close collaboration between the Social Democracy and the trade unions on the one hand and the state on the other led to a steady process of bureaucratization within the labor movement. This development and the almost exclusive concentration on social reform rendered the Social Democratic party quite unattractive to the younger generation. The distribution of party membership, according to length of membership and by age group, is very revealing.

LENGTH OF MEMBERSHIP |

PER CENT |

5 years and under |

46.56 |

6 years to 10 |

16.26 |

11 years to 15 |

16.52 |

16 years and over |

20.66 |

|

100.00 |

|

AGE GROUP |

PER CENT |

|

25 years and under |

7.82 |

|

26 years to 30 |

10.34 |

|

31 years to 40 |

26.47 |

|

41 years to 50 |

27.26 |

|

51 years to 60 |

19.57 |

|

61 years or over |

8.54 |

|

|

100.0027 |

What little freedom of action Social Democracy retained was further restricted by the Communist party. Except for the revolutionary days of 1918 and 1919 and the heyday of inflation and foreign occupation reaching a peak in July 1923, the German Communist party was not a directly decisive political force. At one time it sought to be a small sect of professional revolutionists patterned after the Bolshevik party of 1917; and at other times a ‘revolutionary mass organization,’ a kind of synthesis between the early Russian model and a structure such as the Social Democratic party. Its real significance lay in the fact that it did exert a very considerable indirect influence. A close study of the Communist party would probably reveal more about the characteristics of the German working class and of certain sections of the intelligentsia than would a study of the larger Socialist party and trade unions.

Both the Communists and the S6cialists appealed primarily to the same social stratum: the working class. The very existence of a predominantly proletarian party, dedicated to communism and the dictatorship of the proletariat and stimulated by the magic picture of Soviet Russia and of the heroic deeds of the October Revolution, was a permanent threat to the Social Democratic party and to the controlling forces in the trade-union movement, especially in periods of depression and social unrest. That this threat was a real one though its magnitude was never constant is clear from the election and membership figures. True, the Communists failed to organize a majority of the working class, smash the Socialist party, or capture control of the trade unions. The reason was as much their inability to evaluate correctly the psychological factors and sociological trends operating among German workers as it was their inability to break the material interests and ideological links that bound the workers to the system of pluralistic democracy developed by reformism. Nevertheless, the reformist policy was always wavering simply because of the threat that the workers might desert the reformist organizations and go over to the Communist party. An excellent example is offered by the Social Democratic party’s hesitating tolerance of the Brüning cabinet (1930-32) as compared with its definite opposition to the Papen and Schleicher cabinets (1932). The Communist party had attacked all three as fascist dictatorships.

Reactionaries found in the Communist party a convenient scapegoat, not only in the attack against communists and Marxists but against all liberal and democratic groups. Democracy, liberalism, socialism, and communism were branches of the same tree to the National Socialists (and Italian Fascists). Every law aimed supposedly against both Communists and National Socialists was invariably enforced against the Socialist party and the entire left, but rarely against the right.

The policy of the Communist party itself was strikingly ambivalent. On the one hand, it gave the workers sufficient critical insight to see through the operations of the economic system and thus left them with little faith in the security promised by liberalism, democracy, and reformism. It opened their eyes quite early to the transitory and entirely fictitious character of the post-inflation boom. The fifth World Congress of the Comintern had declared on 9 June 1924 that capitalism was in a stage of acute crisis. Though this analysis was premature and the consequently ‘leftist’ tactics of the Communist party completely erroneous, it did prevent the complacency that developed among the Socialists, who saw in a boom financed by foreign loans the solution of all economic problems and who considered every Social Democratic mayor or city treasurer a first-rate financial wizard if he succeeded in securing a loan from the United States. Even at the very peak of the boom Communist leaders predicted that a severe depression was in store for the world and their party was thus immunized from the dangers of reformist optimism.

On the other hand, the creditable features of the Communist analysis were more than balanced by the profoundly backward character of their policy and tactics: the spread of the leadership principle within the party and the destruction of party democracy, following the complete dependence on the policy of the Russian party; the strong prevalence of revolutionary syndicalist tactics; the ‘National-Bolshevist line’; the doctrine of social fascism; the slogan of the Volksrevolution; and finally, the frequent changes in the party line.

The one other potential ally, the Catholic Center party, proved completely undependable. Under Erzberger and for a time under Josef Wirth, it had provided the most inspiring democratic leadership the Republic experienced. With the growth of reaction, however, the right wing became more and more predominant in the party, with Brüning as the exponent of the moderate conservatives and Papen of the reactionary section. Of the other parties, the Democratic party disappeared from the political scene, and numerous splinter groups tried to take its place as spokesman of the middle class. Houseowners, handicraftsmen, small peasants formed parties of their own; revaluators organized a political movement. They could all obtain some political expression because the system of proportional representation allowed every sectarian movement a voice and prevented the formation of solid majorities.

On the very day that the revolution broke out in 1918, the counter-revolutionary party began to organize. It tried many forms and devices, but soon learned that it could come to power only with the help of the state machine and never against it. The Kapp Putsch of 1920 and the Hitler Putsch of 1923 had proved this.

In the center of the counter-revolution stood the judiciary. Unlike administrative acts, which rest on considerations of convenience and expediency, judicial decisions rest on law, that is on right and wrong, and they always enjoy the limelight of publicity. Law is perhaps the most pernicious of all weapons in political struggles, precisely because of the halo that surrounds the concepts of right and justice. ‘Right,’ Hocking has said, ‘is psychologically a claim whose infringement is met with a resentment deeper than the injury would satisfy, a resentment that may amount to passion for which men will risk life and property as they would never do for an expediency.’28 When it becomes ‘political,’ justice breeds hatred and despair among those it singles out for attack. Those whom it favors, on the other hand, develop a profound contempt for the very value of justice; they know that it can be purchased by the powerful. As a device for strengthening one political group at the expense of others, for eliminating enemies and assisting political allies, law then threatens the fundamental convictions upon which the tradition of our civilization rests.

The technical possibilities of perverting justice for political ends are widespread in every legal system; in republican Germany, they were as numerous as the paragraphs of the penal code.29 Perhaps the chief reason lay in the very nature of criminal trials, for, unlike the American system, the proceedings were dominated not by counsel but by the presiding judge. The power of the judge, furthermore, was strengthened year after year. For political cases, the favorite statutory provisions were those dealing with criminal libel and espionage, the so-called Act for the Protection of the Republic, and, above all, the high treason sections (80 and 81) of the penal code. A comparative analysis of three causes célèbres will make it amply clear that the Weimar criminal courts were part and parcel of the anti-democratic camp.

After the downfall of the Bavarian Soviet Republic in 1919, the courts handed down the following sentences:

|

407 |

persons, fortress imprisonment |

|

1737 |

persons, prison |

|

65 |

persons, imprisoned at hard labor |

Every adherent of the Soviet Republic who had the slightest connection with the unsuccessful coup was sentenced.

The contrast with the judicial treatment of the 1920 right-wing Kapp Putsch could not possibly have been more complete. Fifteen months after the putsch, the Reich ministry of justice announced officially on 21 May 1921 that a total of 705 charges of high treason had been examined. Of them,

412 in the opinion of the courts came under the amnesty law of 4 August 1920, despite the fact that the statute specifically excluded the putsch leaders from its provisions

had become obsolete because of death or other reasons |

|

|

174 |

were not pressed |

|

11 |

were unfinished |

Not one person had been punished. Nor do the statistics give the full picture. Of the eleven cases pending on 21 May 1921, only one ended in a sentence; former Police President von Jagow of Berlin received five years’ honorary confinement. When the Prussian state withdrew Jagow’s pension, the federal supreme court ordered it restored to him. The guiding spirit of the putsch, Dr. Kapp, died before trial. Of the other leaders, some like General von Lüttwitz and Majors Papst and Bischoff escaped; General Ludendorff was not prosecuted because the court chose to accept his alibi that he was present only by accident; General von Lettow-Forbeck, who had occupied a whole town for Kapp, was declared to have been not a leader but merely a follower.

The third significant illustration is the judicial handling of Hitler’s abortive Munich putsch of 1923.30 Hitler, Pöhner, Kriebel, and Weber received five years; Röhm, Frick, Brückner, Pernet, and Wagner one year and three months. Ludendorff once again was present only by accident and was released. Although section 9 of the Law for the Protection of the Republic clearly and unmistakably ordered the deportation of every alien convicted of high treason, the Munich People’s Court exempted Hitler on the specious argument that, despite his Austrian citizenship, he considered himself a German.

It would be futile to relate in detail the history of political justice under the Weimar Republic.31 A few more illustrations will suffice. The penal code created the crime of ‘treason to the country’32 to cover the betrayal of military and other secrets to foreign agents. The courts, however, promptly found a special political use for these provisions. After the Versailles Treaty forced Germany to disarm, the Reichswehr encouraged the formation of secret and illegal bodies of troops, the so-called ‘black Reichswehr.’ When liberals, pacifists, socialists, and communists denounced this violation of both international obligations and German law (for the treaty had become part of the German legal system), they were arrested and tried for treason to the country committed through the press. Thus did the courts protect the illegal and reactionary black Reichswehr. Assassinations perpetrated by the black Reichswehr against alleged traitors within their ranks (the notorious Fehme murders), on the other hand, were either not prosecuted at all or were dealt with lightly.31

During the trials of National Socialists, the courts invariably became sounding boards for propaganda. When Hitler appeared as a witness at the trial of a group of National Socialist officers charged with high treason, he was allowed to deliver a two-hour harangue packed with insults against high government officials and threats against his enemies, without being arrested for contempt. The new techniques of justifying and publicizing National Socialism against the Weimar Republic were defended as steps designed to ward off the communist danger. National Socialism was the guardian of democracy, they shouted, and the courts were only too willing to forget the fundamental maxim of any democracy and of every state, that the coercive power must be a monopoly of the state through its army and police, that not even under the pretext of saving the state may a private group or individual take arms in its defense unless summoned to do so by the sovereign power or unless actual civil war has broken out.

In 1932 the police discovered a National Socialist plot in Hessen. A Dr. Best, now a high official in the regime, had worked out a careful plan for a coup d’état and documentary proof was available (the Boxheimer documents).33 No action was taken. Dr. Best was believed when he stated that he intended to make use of his plan only in the event of a communist revolution.

It is impossible to escape the conclusion that political justice is the blackest page in the life of the German Republic. The judicial weapon was used by the reaction with steadily increasing intensity. Furthermore, this indictment extends to the entire record of the judiciary, and particularly to the change in legal thought and in the position of the judge that culminated in the new principle of judicial review of statutes (as a means of sabotaging social reforms). The power of the judges thereby grew at the expense of the parliament.*

The decline of parliaments represents a general trend in post-war Europe. In Germany it was accentuated by specifically German conditions, especially by the monarchist-nationalist tradition of the bureaucracy. Years before, Max Weber pointed out that sabotage of the power of parliament begins once such a body ceases to be just a ‘social club.’34 When deputies are elected from a progressive mass party and threaten to transform the legislature into an agency for profound social changes, anti-parliamentary trends invariably arise in one form or another. The formation of a cabinet becomes an exceedingly complicated and delicate task, for each party now represents a class, with interests and views of life separated from the others by sharp differences. For example, negotiations went on for four weeks among the Social Democratic, Catholic Center, Democratic, and German People’s parties before the last fully constitutional government, the Müller cabinet, could be formed in May 1928. The political differences between the German People’s party, representing business, and the Social Democratic party, representing the worker’s party, were so deep that only a carefully worked out compromise could bring them together at all, while the Catholic Center was always at odds with the others because of its dissatisfaction over insufficient patronage.

So precarious a structure could not permit its delicate balances to be upset too easily and it became necessary to modify whatever parliamentary principles might tip the scales. Criticism of the governing parties had to be toned down, and the vote of censure was actually used on but two occasions. When no agreement could be reached among the parties, ‘cabinets of experts’ were set up (like the famous Cuno cabinet in 1923), allegedly standing above the political parties and their strife. This travesty on parliamentary democracy became the ideal of the reactionaries, for it enabled them to conceal their anti-democratic policies beneath the cloak of the expert. The consequent impossibility of applying parliamentary controls to the operation of the cabinet was the first sign of the diminution of parliamentary strength.

The Reichstag’s actual political power never corresponded to the wide powers assigned to it by the constitution. In part the explanation lies in the striking social and economic changes that had taken place in Germany, resulting in an enormous complexity of economic life. Growing regimentation in the economic sphere tended to shift the center of gravity from the legislature to the bureaucracy and growing interventionism made it technically impossible for the Reichstag fully to control the administrative power or even to utilize its own legislative rights in full. Parliament had to delegate legislative power. Democracy might have survived none the less—but only if the democratic value system had been firmly rooted in the society, if the delegation of power had not been utilized to deprive minorities of their rights and as a shield behind which antidemocratic forces carried on the work of establishing a bureaucratic dictatorship.

It would be wrong to assume that the decline of parliamentary legislative power was merely an outcome of the last, pre-fascist, period of the German Republic, say from 1930 to 1933. The Reichstag was never too eager to retain the exclusive right of legislation, and from the very beginning of the Republic three competing types of legislation developed side by side. As early as 1919, the Reichstag voluntarily abandoned its supremacy in the legislative field by passing an enabling act that gave sweeping delegations of power to the cabinet, that is, to the ministerial bureaucracy. Similar measures were enacted in 1920, 1921, 1923, and 1926.

The enabling act of 13 October 1923, to cite but one example, empowered the cabinet to ‘enact such measures as it deems advisable and urgent in the financial, economic and social spheres,’ and the following measures were promulgated under this authority: a decree relative to the shutting down of plants, the creation of the Deutsche Rentenbank, currency regulation, modifications in the income tax law, a decree introducing control of cartels and monopolies. In the five years from 1920 through 1924, 450 cabinet decrees were issued as compared with 700 parliamentary statutes. The legislative power of the cabinet thus had its beginning practically with the birth of the German parliamentary system.

The second index of parliamentary decline is to be found in the character of the statute itself. The complexity of the legislative set-up led the Reichstag to lay down only vague blanket principles and to give the cabinet the power of application and execution.

The third and final step was the presidential emergency decree, based on article 48 of the constitution. While the Reichstag did have the constitutional right to repeal such emergency legislation, that was small consolation, since the right was more apparent than real. Once measures are enacted, they affect social and economic life deeply, and though parliament may have found it easy to abolish an emergency decree (the lowering of the cartel prices and of wages, for example), it could not so easily pass a substitute measure. This consideration played some part in determining the attitude of the Reichstag to the Brüning decrees of 1930 introducing profound changes into the economic and social structure of the nation. Mere repeal would have disrupted the flow of national life, while a substitute was impossible to achieve because of the antagonisms among the different groups in parliament. As a matter of fact, much as the parties may have decried the delegation of legislative power to the president and the bureaucracy, they were often quite happy to be rid of the responsibility.

The keystone of any parliamentary system is the right of the legislature to control the budget, and this collapsed during the Weimar Republic. The constitution had restricted the Reichstag somewhat by forbidding it to increase expenditures once they were proposed by the cabinet, except with the consent of the federal council. Apart from this limitation, however, all the necessary safeguards of the budgetary rights of parliament had apparently been written into the budget law (Reichshaushaltsordnung) of 31 December 1922 and into articles 85, 86, and 87 of the constitution. But enough loopholes remained for the bureaucracy to encroach steadily. The matter of auditing and accounting was taken away from the Reichstag entirely and transferred to the Rechnungshof für das Deutsche Reich, an administrative body independent of both cabinet and parliament, to which no member of parliament could belong. Finally, the minister of finance occupied so strong a position in relation to his colleagues that he could veto any minor expenditure alone, and he and the chancellor together could veto other expenditures even against a majority decision of the whole cabinet. Ultimately the president of the Reich enacted the budget by emergency decrees, against the advice of constitutional lawyers.

Once again we find in Germany only the specific working out of a general trend. Parliament’s budgetary rights always tend to decline in interventionist states, as the English example shows. Fixed charges increase at the expense of charges for supplies. Where there is a huge permanent bureaucracy and increasing state activity in many economic and social fields, expenditures become fixed and permanent, and, in fact, fall outside the jurisdiction of the parliament. In Germany, furthermore, only the income and expenditure of the Reich proper were recorded in the budget. The financial operations of the independent federally owned corporations, whether organized under public or private law, lay outside budgetary control. The post and railways, mines, and factories owned by the Reich were not dependent on the budget. Only their balances appeared, either as income to the Reich or as a subsidy demanded from it.

This entire trend was in full conformity with the wishes of German industry. Their major lobbying organization, the Federal Union of German Industry, demanded ever greater restrictions upon the Reichstag’s budget rights. The German People’s party took over their proposals in its platform. They insisted that all expenditures should have the approval of the cabinet and that the auditing body, the Rechnungshof, should be given a decisive position in determining whether or not the budget was to be accepted. The reason for this attempt to sabotage the budget rights of the Reichstag was frankly stated by Dr. Popitz, the foremost expert on public finance in the federal ministry of finance. Universal suffrage, he said, had brought into the Reichstag the strata of society that do not pay high income taxes and surtaxes.35

The decline of parliamentary supremacy accrued to the benefit of the president and hence to the ministerial bureaucracy. Following the American model, the Weimar constitution provided for popular presidential election. The similarity between the two constitutional systems ended right there, however. In the United States the president is the independent head of the executive branch of the government, whereas the German president’s orders had to be countersigned by the appropriate cabinet minister or by the chancellor, who assumed political responsibility for presidential acts and pronouncements. The German president was relatively free, nevertheless. For one thing, the popular election gave him a position of some independence from the various parties. He could appoint the chancellor and ministers at his discretion; he was not bound by any constitutional custom, such as the English tradition of calling upon the leader of the victorious party. Presidents Ebert and von Hindenburg both insisted on making their selections freely and independently. The president’s right to dissolve parliament gave him further political power. The provision that he could not do so twice for the same reason was easily evaded.

Nevertheless the president could not be termed the ‘guardian of the constitution,’ as the anti-democratic theorists would have it. He did not represent democracy and was far from being the neutral head of the state, standing above the squabbles of parties and special interests. Throughout the Weimar Republic and especially under Hindenburg, the presidency was eminently partisan. Political groups arranged for and financed the president’s election; he remained dependent on partisan groups surrounding and advising him. He had preferences and a political alignment, which he attempted to carry far beyond constitutional limits. When Communists and Socialists tried to expropriate the princely houses through a popular initiative, President von Hindenburg condemned the attempt in an open letter (22 May 1926) for which he did not even bother to get the signature of the chancellor, insisting that such a letter was his private affair. On the occasion of Brüning’s second appointment, Hindenburg demanded that two of his conservative friends (Treviranus and Schiele) be included in the cabinet. Then he betrayed them.

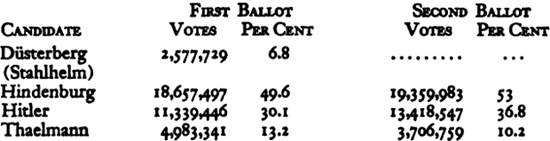

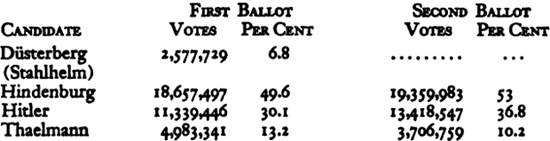

Ebert’s authority had been limited. Being a Socialist, he could not command the respect due the head of the Republic. But Hindenburg was the Field Marshal, the great soldier, the old man. That was different, especially after Brüning had created a veritable Hindenburg myth to assure the former’s re-election in 1932. Hindenburg’s strength lay predominantly in his close connections with the army and large estate owners of East Prussia. From 1930 on, when the presence of 107 National Socialist deputies made ordinary parliamentary legislation well-nigh impossible, he became the sole legislator, using the emergency powers of article 48 of the constitution.36

The Reichswehr, reduced to 100,000 men by the Versailles Treaty, continued to be the stronghold of conservatism and nationalism. With army careers now closed to many and promotion slow, there is little wonder that the officers’ corps became militantly anti-democratic, despising parliamentarianism because it pried too closely into the secrets of army expenditure, and detesting the Socialists because they had accepted the Versailles Treaty and the destruction of the supremacy of German militarism. Whenever a political crisis arose, the army invariably sided with the anti-democratic elements. Hitler himself was a product of the army, which had made use of him as far back as 1918 and 1919 as a speaker and propaganda officer. None of this is surprising. What is surprising is that the democratic apparatus tolerated the situation.

The Reichswehr ministers, the inevitable Gessler and the more loyally democratic General Groener, were in an extremely ambiguous constitutional position. As cabinet ministers they were subject to parliamentary control and responsibility, but as subordinates of the president, the commander-in-chief, they were free from parliamentary control. The contradiction was easily solved in practice: the Reichswehr ministers spoke for the army and against the Reichstag. In fact, so completely did they identify themselves with the army bureaucracy that parliamentary control over the army became virtually non-existent.

The Social Democracy and the trade unions were completely helpless against the many-sided attacks on the Weimar democracy. Moderate attempts were made to spread the idea of an economic democracy, but this new ideology proved even less attractive than the old Socialist program. Salaried employees remained aloof; the civil-service organization affiliated with the Socialist trade unions declined in membership from 420,000 in 1922 to 172,000 in 1930, while the so-called neutral, but in fact Nationalistic, civil-service body organized 1,043,000 members in 1930, primarily from the middle and lower ranks. The significance of these figures is obvious.

The Social Democratic party was trapped in contradictions. Though it still claimed to be a Marxian party, its policy had long been one of pure gradualism. It never mustered the courage to drop one or the other, traditional ideology or reformist policy. A radical break with tradition and the abandonment of Marxism would have delivered thousands of adherents into the Communist camp. To have abandoned gradualism for a revolutionary policy, on the other hand, would have required cutting the many links binding the party to the existing state. The Socialists therefore retained this ambiguous position and they could not create a democratic consciousness. The Weimar constitution, attacked on the right by Nationalists, National Socialists, and reactionary liberals, and on the left by the Communists, remained merely a transitory phenomenon for the Social Democrats, a first step to a greater and better future. And a transitory scheme cannot arouse much enthusiasm.*

Even before the beginning of the great depression, therefore, the ideological, economic, social, and political systems were no longer functioning properly. Whatever appearance of successful operation they may have given was based primarily on toleration by the antidemocratic forces and on the fictitious prosperity made possible by foreign loans. The depression uncovered and deepened the petrification of the traditional social and political structure. The social contracts on which that structure was founded broke down. The Democratic party disappeared; the Catholic Center shifted to the right; and the Social Democrats and Communists devoted far more energy to fighting each other than to the struggle against the growing threat of National Socialism. The National Socialist party in turn heaped abuse upon the Social Democrats. They coined the epithet, November Criminals: a party of corruptionists and pacifists responsible for the defeat in 1918, for the Versailles Treaty, for the inflation.

The output of German industry had dropped sharply. Unemployment was rising:37 six million were registered in January 1932, and there were perhaps two million more of the so-called invisible unemployed. Only a small fraction received unemployment insurance and an ever larger proportion received no support at all. The unemployed youth became a special problem in themselves. There were hundreds of thousands who had never held jobs. Unemployment became a status, and, in a society where success is paramount, a stigma. Peasants revolted in the north while large estate owners cried for financial assistance. Small businessmen and craftsmen faced destruction. Houseowners could not collect their rents. Banks crashed and were taken over by the federal government. Even the stronghold of industrial reaction, the United Steel Trust, was near collapse and its shares were purchased by the federal government at prices far above the market quotation. The budget situation became precarious. The reactionaries refused to support a large-scale works program lest it revive the declining power of the trade unions, whose funds were dwindling and whose membership was declining.

The situation was desperate and called for desperate measures. The Social Democratic party could choose either the road of political revolution through a united front with the Communists under Socialist leadership, or co-operation with the semi-dictatorships of Brüning, Papen, and Schleicher in an attempt to ward off the greater danger, Hitler. There was no other choice. The Social Democratic party was faced with the most difficult decision in its history. Together with the trade unions, it decided to tolerate the Brüning government when 107 National Socialist deputies entered the Reichstag in September 1930 and made a parliamentary majority impossible. Toleration meant neither open support nor open attack. The policy was justified ideologically in the key address of Fritz Tarnow, deputy and head of the Woodworker’s Union, at the last party convention (1931):

Do we stand . . . at the sick-bed of capitalism merely as the diagnostician, or also as the doctor who seeks to cure? Or as joyous heirs, who can hardly wait for the end and would even like to help it along with poison? . . . It seems to me that we are condemned both to be the doctor who earnestly seeks to cure and at the same time to retain the feeling that we are the heirs, who would prefer to take over the entire heritage of the capitalist system today rather than tomorrow.38

This was the policy of a man who is hounded by his enemies but refuses either to accept annihilation or to strike back, and invents excuse after excuse to justify his inactivity.

Continuing the policy of the lesser evil, the party supported the re-election of Hindenburg in April 1932.

Hindenburg promptly re-paid his debt by staging the coup d’état of 20 June 1932, replacing the legally elected Prussian government of Otto Braun by his courtier, Papen. All that the Social Democratic party did in opposition was to appeal to the Constitutional Court, which rendered a compromise verdict that did not touch the political situation. Papen remained as Reich commissioner for Prussia. The Social Democratic party became completely demoralized; the last hope of resistance against the National Socialists seemed to have vanished.

The Communists had been no less optimistic than the Socialists, but for different reasons. ‘We insist soberly and seriously,’ said Thaelmann, ‘that the 14th of September was, so to speak, Hitler’s best day; that no better will follow but rather worse.’39 They looked forward to a social revolution in the immediate future, leading to the dictatorship of the proletariat.

In the November elections of 1932 the National Socialists lost 34 seats. The Social Democrats, thinking only in parliamentary terms, were jubilant: National Socialism was defeated. Rudolf Hilferding, their leading theorist and editor of the party journal, Die Gesellschaft, published an article in the January 1933 issue entitled ‘Between Two Decisions.’ He argued that National Socialism was blocked by parliamentary legality (Malaparte’s idea).* Hilferding became bold. He refused collaboration with Schleicher, Hitler’s immediate predecessor, and he rejected the united front with the Communist party. The primary aim of the Socialists, he said, was the fight against communism. He ridiculed Hitler’s attempt to get dictatorial power from President von Hindenburg: To demand the results of a revolution without revolution—this political construction could arise only in the brain of a German politician.’40 Hilferding forgot that the Italian politician Mussolini had held the very same idea and had carried it out successfully.

Only a few days after the publication of Hilferding’s article, Hitler took power. On 4 January 1933 the Cologne banker Kurt von Schroeder, whose name looms large in National Socialist history, arranged the conference between Papen and Hitler that brought about a reconciliation between the old reactionary groups and the new counter-revolutionary movement, and paved the way for Hitler’s appointment as chancellor on 30 January. It was the tragedy of the Social Democratic party and trade unions to have had as leaders men with high intellectual qualities but completely devoid of any feeling for the condition of the masses and without any insight into the great social transformations of the post-war period.

The National Socialist German Workers Party was without an ideology, composed of the most diverse social strata but never hesitating to take in the dregs of every section, supported by the army, the judiciary, and parts of the civil service, financed by industry, utilizing the anti-capitalist sentiments of the masses and yet careful never to estrange the influential moneyed groups. Terror and propaganda seized upon the weak spots in the Weimar democracy; and from 1930 to 1933 Weimar was merely one large weak spot.

‘The man with power,’ said Woodrow Wilson in his Kansas address of 6 May 1911, ‘but without conscience, could, with an eloquent tongue, if he cared for nothing but his own power, put this whole country into a flame, because this whole country believes that something is wrong, and is eager to follow those who profess to be able to lead it away from its difficulties.’41

Every social system must somehow satisfy the primary needs of the people. The imperial system succeeded to the extent and so long as it was able to expand. A successful policy of war and imperialist expansion had reconciled large sections of the population to the semi-absolutism. In the face of the material advantages gained, the anomalous character of the political structure was not decisive. The army, the bureaucracy, industry, and the big agrarians ruled. The divine-right theory—the official political doctrine—merely veiled their rule and it was not taken seriously. The imperial rule was in fact not absolutistic, for it was bound by law, proud of its Rechtsstaat theory. It lost out and abdicated when its expansionist policy was checked.

The Weimar democracy proceeded in a different direction. It had to rebuild an impoverished and exhausted country in which class antagonisms had become polarized. It attempted to merge three elements: the heritage of the past (especially the civil service), parliamentary democracy modeled after Western European and American patterns, and a pluralistic collectivism, the incorporation of the powerful social and economic organizations directly into the political system. What it actually produced, however, were sharpened social antagonisms, the breakdown of voluntary collaboration, the destruction of parliamentary institutions, the suspension of political liberties, the growth of a ruling bureaucracy, and the renaissance of the army as a decisive political factor.

Why?

In an impoverished, yet highly industrialized, country, pluralism could work only under the following different conditions. In the first place, it could rebuild Germany with foreign assistance, expanding its markets by peaceful means to the level of its high industrial capacity. The Weimar Republic’s foreign policy tended in this direction. By joining the concert of the Western European powers the Weimar government hoped to obtain concessions. The attempt failed. It was supported neither by German industry and large landowners nor by the Western powers. The year 1932 found Germany in a catastrophic political, economic, and social crisis.

The system could also operate if the ruling groups made concessions voluntarily or under compulsion by the state. That would have led to a better life for the mass of the German workers and security for the middle classes at the expense of the profits and power of big business. German industry was decidedly not amenable, however, and the state sided with it more and more.

The third possibility was the transformation into a socialist state, and that had become completely unrealistic in 1932 since the Social Democratic party was socialist only in name.

The crisis of 1932 demonstrated that political democracy alone without a fuller utilization of the potentialities inherent in Germany’s industrial system, that is, without the abolition of unemployment and an improvement in living standards, remained a hollow shell.

The fourth choice was the return to imperialist expansion. Imperialist ventures could not be organized within the traditional democratic form, however, for there would have been too serious an opposition. Nor could it take the form of restoration of the monarchy. An industrial society that has passed through a democratic phase cannot exclude the masses from consideration. Expansionism therefore took the form of National Socialism, a totalitarian dictatorship that has been able to transform some of its victims into supporters and to organize the entire country into an armed camp under iron discipline.

* See pp. 204, 209 for a more detailed discussion.

* See pp. 406, 423 for a discussion of the works councils.

* See pp. 236-7.

* See pp. 261-3.

* On strikes, see pp. 411-12.

* See also pp. 442, 446.

* See also pp. 45-6.

* See p. 41.