CHAPTER 1

Permutations and Combinations

1. INTRODUCTION

This chapter summarizes the simplest and most widely used material of the theory of combinations. Because it is so familiar, having been set forth for a generation in textbooks on elementary algebra, it is given here with a minimum of explanation and exemplification. The emphasis is on methods of reasoning which can be employed later and on the introduction of necessary concepts and working tools. Among the concepts is the generating function, the introduction of which leads to consideration of both permutations and combinations in great generality, a fact which seems insufficiently known.

Most of the proofs employ in one way or another either or both of the following rules.

Rule of Sum: If object A may be chosen in m ways, and B in n other ways, “either A or B” may be chosen in m + n ways.

Rule of Product: If object A may be chosen in m ways, and thereafter B in n ways, both “A and B” may be chosen in this order in mn ways.

These rules are in the nature of definitions (or tautologies) and need to be understood rather than proved. Notice that, in the first, the choices of A and B are mutually exclusive; that is, it is impossible to choose both (in the same way). The rule of product is used most often in cases where the order of choice is immaterial, that is, where the choices are independent, but the possibility of dependence should not be ignored.

The basic definitions of permutations and combinations are as follows:

Definition. An r-permutation of n things is an ordered selection or arrangement of r of them.

Definition. An r-combination of n things is a selection of r of them without regard to order.

A few points about these should be noted. First, in either case, nothing is said of the features of the n things; they may be all of one kind, some of one kind, others of other kinds, or all unlike. Though in the simpler parts of the theory, they are supposed all unlike, the general case is that of k kinds, with nj things of the jth kind and n = n1 + n2 + · · · + nk. The set of numbers (nl, n2, · · · , nk) is called the specification of the things. Next, in the definition of permutations, the meaning of ordered is that two selections are regarded as different if the order of selection is different even when the same things are selected; the r-permutations may be regarded as made in two steps, first the selection of all possible sets of r (the r-combinations), then the ordering of each of these in all possible ways. For example, the 2-permutations of 3 distinct things labeled 1, 2, 3 are 12, 13, 23; 21, 31, 32; the first three of these are the 2-combinations of these things.

In the older literature, the r-permutations of n things are called variations, r at a time, for r < n, the term permutation being reserved for the ordering operation on all n things, as is natural in the theory of groups, as noticed in Chapter 4. This usage is followed here by taking the unqualified term, permutation, as always meaning n-permutation.

2. r-PERMUTATIONS

The rules and definition will now be applied to obtain the simplest and most useful enumerations.

2.1. Distinct Things

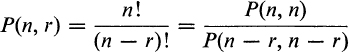

The first of the members of an r-permutation of n distinct things may be chosen in n ways, since the n are distinct. This done, the second may be chosen in n – 1 ways, and so on until the rth is chosen in n – r + 1 ways. By repeated application of the rule of product, the number required is

![]()

If r = n, this becomes

![]()

that is, the product of all integers from 1 to n, which is called n-factorial, is written n! as above. P(n, 0), which has no combinatorial meaning, is taken by convention as unity.

Using (2), (1) may be rewritten

and is also given the abbreviation

![]()

The last is called the falling r-factorial of n; since the same notation is also used in the theory of the hypergeometric function to indicate n(n + 1) · · · (n + r – 1), the word “falling” in the statement is necessary to avoid ambiguity.

The relation P(n,n) = P(n, r)P(n – r, n – r) appearing above also follows from the rule of product.

It is also interesting to note the following recurrence relation

This follows by simple algebra from (1), writing n = n – r + r ; it also follows by classifying the r-permutations as to whether they do not or do contain a given thing. If they do not, the number is P(n – 1, r); if they do, there are r positions in which the given thing may appear and P(n – 1, r – 1) permutations of the n – 1 other things.

Example 1. The 12 2-permutations of 4 distinct objects (n = 4, r = 2) labeled 1, 2, 3, and 4 are:

![]()

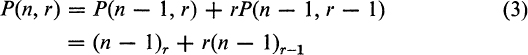

2.2. The Number of Permutations of n Things, p of Which Are of One Kind, q of Another, etc.

Here, permutations n at a time only are considered; that is, the term “permutation” is used in the unqualified sense. Let x be the number required. Suppose the p like things are replaced by p new things, distinct from each other and from all other kinds of things being permuted. These may be permuted in p! ways (by equation (2)); hence the number of permutations of the new set of objects is xp!. The same goes for every other set of like things and, since finally all things become unlike and the number of permutations of n unlike things is n!,

![]()

or

The right of (4) is a multinomial coefficient, that is, a coefficient* in the expansion of (a + b + · · ·)n. It is also the number of arrangements of n unlike things into unlike cells or boxes, p in the first, q in the second, and so on, without regard to order in any cell, as will be shown in Chapter 5.

Example 2. The number of arrangements on one shelf of n different books, for each of which there are m copies, is (nm)!/(m!)n.

The more general problem of finding the number of r-permutations of things of general specification (p of one kind, q of another, etc.) will be treated in a later section of this chapter by the method of generating functions.

2.3. r-Permutations with Unrestricted Repetition

Here there are n kinds of things, and an unlimited number of each kind or, what is the same thing, any object after being chosen is replaced in the stock. Hence, each place in an r-permutation may be filled in n different ways, because the stock of things is unaltered by any choice. By the rule of product, the number of permutations in question, that is, the r-permutations with repetition of n things, is,

![]()

Example 3. The number of ways an r-hole tape (as used in teletype and computing machinery) can be punched is 2r. Here there are two “objects”, clear (unpunched) and punched tape, for each of the r positions of any line on the tape.

In the language of statistics, U(n, r) is for sampling with replacement, as contrasted with P(n, r) which is for sampling without replacement.

3. COMBINATIONS

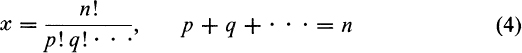

3.1. r-Combinations of n Distinct Things

The simplest derivation is to notice that each combination of r distinct things may be ordered in r! ways, and so ordered is an r-permutation; hence, if C(n, r) is the number in question

![]()

and

where the last symbol is that usual for binomial coefficients, that is, the coefficients in the expansion of (a + b)n. (![]() ,

, ![]() , nCr, and (n, r) are alternative notations; the first two are difficult in print and the superscripts are liable to confusion with exponents, the first subscript of the third is sometimes hard to associate with the C which it modifies, the C is strictly unnecessary since the numbers are not necessarily associated with combinations, but all have the sanction of some usage in and out of print.)

, nCr, and (n, r) are alternative notations; the first two are difficult in print and the superscripts are liable to confusion with exponents, the first subscript of the third is sometimes hard to associate with the C which it modifies, the C is strictly unnecessary since the numbers are not necessarily associated with combinations, but all have the sanction of some usage in and out of print.)

C(n, 0), the number of combinations of n things zero at a time, has no combinatorial meaning, but is given by (6) to be unity, which is the usual convention. The values

![]()

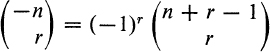

are also in agreement with (6). C(–n, r) has no combinatorial meaning, but it may be noticed that, from (6)

and

Example 4. The 6 combinations of 4 distinct objects taken two at a time (n = 4, r = 2), labeling the objects 1, 2, 3, and 4, are:

![]()

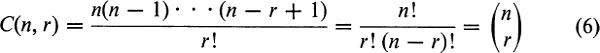

Another derivation of (6) is by recurrence and the rule of sum. The combinations may be divided into those which include a given thing, say the first, and those which do not. The number of those of the first kind is C(n – 1, r – 1), since fixing one element of a combination reduces both n and r by one; the number of those of the second kind, for a similar reason, is C(n – 1, r). Hence,

![]()

Using mathematical induction, it may be shown that (6) is the only solution of (7) which satisfies the boundary conditions C(n, 0) = C(l, 1) = 1, C( 1,2) = C(l,3) = · · · = 0.

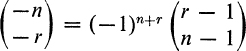

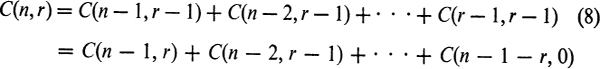

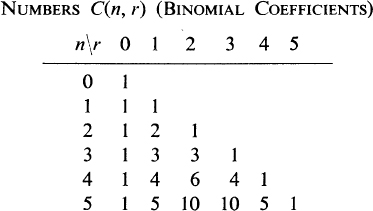

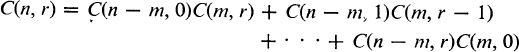

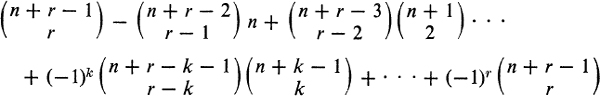

Equation (7) is an important formula because it is the basic recurrence for binomial coefficients. Notice that by iteration it leads to

The first of these classifies the r-combinations of n numbered things according to the size of the smallest element, that is, C(n – k, r – 1) is the number of r-combinations in which the smallest element is k. The similar combinatorial proof of the second does not lend itself to simple statement.

For numerical concreteness, a short table of the numbers C(n, r), a version of the Pascal triangle, is given below. Note how easily one row may be filled in from the next above by (7). Note also the symmetry, that is C(n, r) = C(n, n – r); this follows at once from (6), and is also evident from the fact that a selection of r determines the n–r elements not selected.

3.2. Combinations with Repetition

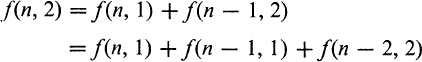

The number sought is that of r-combinations of n distinct things, each of which may appear indefinitely often, that is, 0 to r times. This is a function of n and r, say f(n, r).

The most natural method here seems to be that of recurrence and the rule of sum. Suppose the things are numbered 1 to n; then the combinations either contain 1 or they do not. If they do, they may contain it once, twice, and so on, up to r times, but, in any event, if one of the appearances of element 1 is crossed out, f(n, r – 1) possible combinations are left. If they do not, there are f(n – 1, r) possible combinations. Hence,

![]()

If r = 1, no repetition of elements is possible and f(n, 1) = n. (Note that this determines f(n, 0) = f(n, 1) – f(n – 1,1) as 1, a natural convention.) If n = 1, only one combination is possible whatever r, so f(1, r) = 1. Now

and if this is repeated until the appearance of f(1, 2), which is unity,

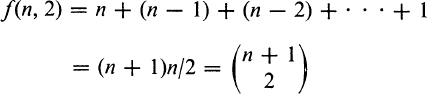

by the formula for the sum of an arithmetical series, or by the first of equations (8).

again by the first of equations (8).

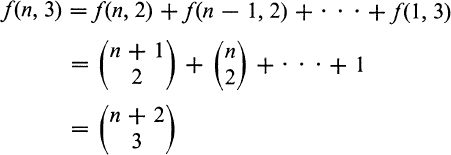

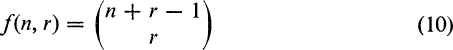

The form of the general answer, that is, the number of r-combinations with repetition of n distinct things, now is clearly

and it may be verified without difficulty that this satisfies (9) and its boundary conditions: f(n, 1) = n, f(1, r) = 1.

Example 5. The number of combinations with repetition, 2 at a time, of 4 things numbered 1 to 4, by equation (10), is 10; divided into two parts as in equation (9), these combinations are

![]()

The result in (10) is so simple as to invite proofs of equal simplicity. The best of these, which may go back to Euler, is as follows. Consider any one of the r-combinations with repetition of n numbered things, say, c1c2 · · · cr in rising order (with like elements taken to be rising), where, of course, because of unlimited repetition, any number of consecutive c’s may be alike. From this, form a set d1d2 · · · dr by the rules: d1 = c1 + 0, d2 = c2 + 1, di = ci + i – 1, · · ·, dr = cr + r – 1; hence, whatever the c’s, the d’s are unlike. It is clear that the sets of c’s and d’s are equinumerous; that is, each distinct r-combination produces a distinct set of d’s and vice versa. The number of sets of d’s is the number of r-combinations (without repetition) of elements numbered 1 to n + r – 1, which is C(n + r – 1, r), in agreement with (10); for example, the d’s corresponding to the r-combinations of Example 5 are (in the same order)

![]()

4. GENERATING FUNCTION FOR COMBINATIONS

The enumerations given above may be unified and generalized by a relatively simple mathematical device, the generating function.

For illustration, consider three objects labeled x1, x2, and x3. Form the algebraic product

![]()

Multiplied out and arranged in powers of t, this is

![]()

or, in the notation of symmetric functions,

![]()

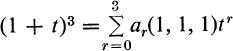

where a1, a2, and a3 are the elementary symmetric functions of the three variables x1, x2, and x3. These symmetric functions are identified by the equation ahead, and it will be noticed that ar, r = 1,2, 3, contains one term for each combination of the three things taken r at a time. Hence, the number of such combinations is obtained by setting each xi to unity, that is,

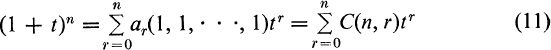

In the case of n distinct things labeled x1 to xn, it is clear that

and

a result foreshadowed in the remark following (6), which identifies the numbers C(n, r) as binomial coefficients.

The expression (1 + t)n is called the enumerating generating function or, for brevity, simply the enumerator, of combinations of n distinct things.

The effectiveness of the enumerator in dealing with the numbers it enumerates is indicated in the examples following.

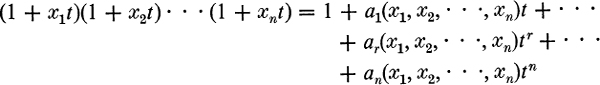

Example 6. In equation (11), put t = 1 ; then

![]()

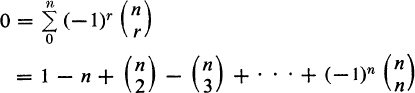

that is, the total number of combinations of n distinct things, any number at a time, is 2n, which is otherwise evident by noticing that in this total each element either does or does not appear. With t = –1, equation (11) becomes

Adding and subtracting these equations leads to

![]()

Example 7. Write n = n – m + m. Since

![]()

it follows by equating coefficients of tr that

or

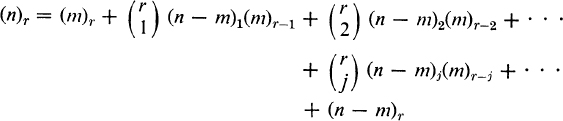

![]()

The corresponding relation for falling factorials (n)r = n(n – 1)· · · (n – r + 1) is

This is often called Vandermonde’s theorem.

Another form is

![]()

which implies the relation in rising factorials:

![]()

namely,

![]()

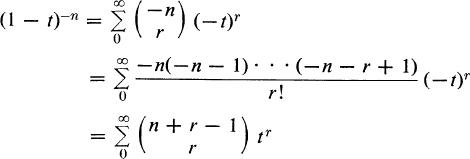

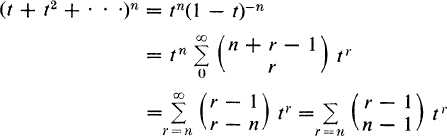

The result in (11) is only a beginning. What are the generating functions and enumerators when the elements to be combined are not distinct?

In the expression (1 + x1t)(1 + x2t) · · · (1 + xnt), each factor of the product is a binomial (2-termed expression) which indicates in the terms 1 and xkt the fact that element xk may not or may appear in any combination. The product generates combinations because the coefficient of tr is obtained by picking unity terms from n-r factors and terms like xkt from the r remaining factors in all possible ways; these are the r-combinations by definition. The factors are limited to two terms because no object may appear more than once in any combination.

Hence, if the combinations may include object xk 0, 1, 2, · · · j times, the generating function is altered by writing

![]()

in place of 1 + xkt. Moreover, the factors may be tailored to any specifications quite independently. Thus, if xk is always to appear an even number of times but not more than j times, the factor (with j = 2i + 1) is

![]()

Hence the generating function of any problem describes not only the kinds of objects but also the kinds of combinations in question. A factor ![]() in any term of a coefficient of a power of t in the generating function indicates that object xk appears i times in the corresponding combination.

in any term of a coefficient of a power of t in the generating function indicates that object xk appears i times in the corresponding combination.

A general formula for all possibilities could be written down, but the notation would be cumbersome and the formula probably less illuminating than the examples which follow.

Example 8. For combinations with unlimited repetition of objects of n kinds and no restriction on the number of times any object may appear, the enumerating generating function is

![]()

This is the same as

which confirms the result in (10).

Example 9. For combinations as in Example 8 and the further condition that at least one object of each kind must appear, the enumerating generating function is

![]()

and

that is, the number of combinations in question is 0 for r < n and C(r – 1, r – n) for r ≥ n. For instance, for n = 3 and elements a, b, c, there is one 3-combination abc and six = C(4, 2) 5-combinations, namely, aaabc, abbbc, abccc, aabbc, aabcc, abbcc.

Example 10. For combinations as in Example 8, but with each object appearing an even number of times, the enumerator is

![]()

![]()

Thus the number of r-combinations for r odd is zero, and the 2r-combinations are equinumerous with the r-combinations of Example 8, as is immediately evident. Note that

![]()

so that the sum

is zero for r odd and equal to ![]() for r = 2s, that is,

for r = 2s, that is,

![]()

Obviously, examples like these could be multiplied indefinitely. The essential thing to notice is that, in forming a combination, the objects are chosen independently and the generating function takes advantage of this independence by a rule of multiplication. In effect, each factor of a product is a generating function for the objects of a given kind. These generating functions appear in product just as they do for the sum of independent random variables in probability theory.

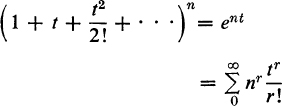

5. GENERATING FUNCTIONS FOR PERMUTATIONS

Since x1x2 and x2x1; are indistinguishable in an algebraic commutative process, it is impossible to give a generating function which will exhibit permutations as those above have exhibited combinations. Nevertheless, the enumerators are easy to find.

For n unlike things, it follows at once from (1) that

![]()

that is, (1 + t)n on expansion gives P(n, r) as coefficient of tr/r!.

This supplies the hint for generalization. If an element may appear 0, 1, 2, · · · , k times, or if there are k elements of a given kind, a factor 1 + t on the left of (12) is replaced by

![]()

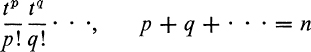

This is because the number of permutations of n things, p of which are of one kind, q of another, and so on, is given by (4) as

which is the coefficient of tn/n! in the product

which corresponds to the prescription that the letter indicating things of the first kind appear exactly p times, the letter for things of the second kind appear exactly q times, and so on.

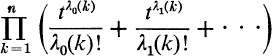

Hence, if the permutations are prescribed by the conditions that the kth of n elements is to appear λ0(k), λ1(k), · · · times, k = 1 to n, the number of r-permutations is the coefficient of tr/r! in the product

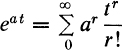

The (enumerating) generating functions appearing here may be called exponential generating functions, as suggested by

These remarks will become clearer in the examples which follow.

Example 11. For r-permutations of n different objects with unlimited repetition (no restriction on the number of times any object may appear), the enumerator is

![]()

But

Hence, the number of r-permutations is nr, in agreement with (5).

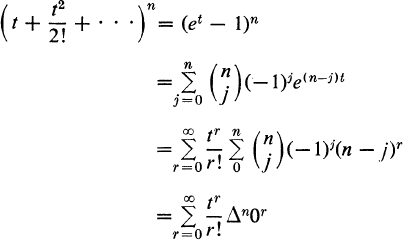

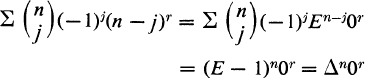

Example 12. For permutations as in Example 11 and the additional condition that each object must appear at least once, the enumerator is

The last result is in the notation of the calculus of finite differences. If E is a shift operator such that Eu(n) = u(n + 1) and Δ is the difference operator defined by Δu(n) = u(n + 1) – u(n) = (E – 1)u(n), the result may be obtained as follows:

For the sake of being concrete, it may be noted that Δ0r = 1r, Δ20r = 2r – 2, Δ30r = 3r – 3 · 2r + 3. These numbers appear again in later chapters.

Example 13. For r-permutations of elements with the specification of Section 2.2, that is, p of one kind, q of a second, and so on, the enumerating generating function is

![]()

It is easy to verify (compare the remark on page 12) that the coefficient of tn/n! is n!/p! q! · · ·, in agreement with (4). The number of r-permutations is the coefficient of tr/r!; hence the generating function above is the result promised at the end of Section 2.2.

Finally it may be noted that the permutations with unlimited repetition of Examples 11 and 12 may be related to problems of distribution which will be treated in Chapter 5. Take for illustration the permutations three at a time and with repetition of two kinds of things, say a and b, which are eight in number, namely

![]()

These may be put into 1–1 correspondence with the distribution of 3 different objects into 2 cells, as indicated by

![]()

the vertical line separating the cells.

This suggests what will be shown, in Chapter 5, namely: the permutations with repetition of objects of n kinds r at a time are equinumerous with the distributions of r different objects into n different cells. The restriction of Example 12 that each permutation contain at least one object of each kind corresponds to the restriction that no cell may be empty.

REFERENCES

1. S. Barnard and J. M. Child, Higher Algebra, New York, 1936.

2. G. Chrystal, Algebra (Part II), London, 1900.

3. E. Netto, Lehrbuch der Combinatorik, Leipzig, 1901.

4. W. A. Whitworth, Choice and Chance, London, 1901.

PROBLEMS

1. (a) Show that p plus signs and q minus signs may be placed in a row so that no two minus signs are together in ![]() ways.

ways.

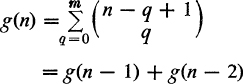

(b) Show that n signs, each of which may be plus or minus, may be placed in a row with no two minus signs together in f(n) ways, where f(0) = 1, f(1) = 2 and

![]()

(c) Comparison of (a) and (b) requires that

![]()

with [x] indicating the largest integer not greater than x. Show that

and g(0) = 1, g(1) = 2, so that g(n) = f(n). The numbers f(n) are Fibonacci numbers.

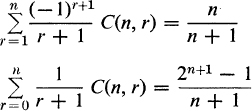

2. (a) Show that

3. From the generating function (1 + t)n Σ C(n, r)tr, or otherwise, show that

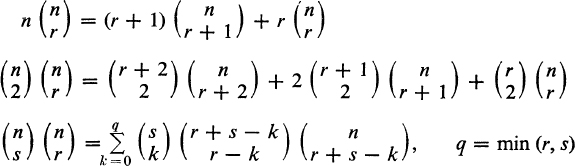

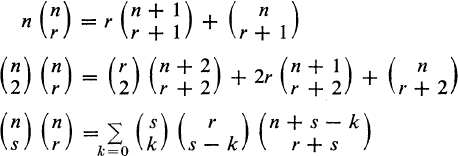

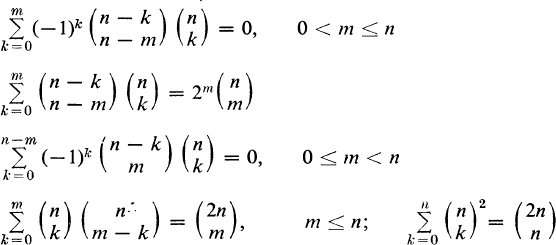

4. Derive the following binomial coefficient identities:

5. Show that the number of r-combinations of n objects of specification p1q(p + q = n), that is, with p of one kind and one each of q other kinds, is

![]()

From this, show that the enumerator is

![]()

and determine the recurrence

![]()

6. Show that the number of r-combinations of n objects of specification 2m1n–2m is

![]()

Derive the recurrence

![]()

7. Show that the number of r-combinations of objects of specification sm (m kinds of objects, s of each kind), sometimes called “regular” combinations, is

![]()

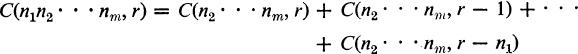

8. Write C(n1n2 · · · nm, r) for the number of r-combinations of objects of specification (n1n2 · · · nm); derive the recurrence

9. For permutations with unlimited repetition, derive the result of Example 12 by classifying the permutations of Example 11, nr in total, according to the number of distinct objects they contain.

10. From the generating function of Example 12, or otherwise, show that

![]()

11. For permutations with unlimited repetition and each object restricted to appearing zero or an even number of times, show that the number of r-permutations may be written δn0r with δun = (un+1 + un–1)/2. Derive the recurrence

![]()

12. Write Pn for the total number of permutations of n distinct objects; that is, Pn = Σ (n)r.

(a) Derive the recurrence

![]()

and verify the table

![]()

(b) Show that Pn = (E + 1)n0! = n! ![]() 1/k! = n!e –

1/k! = n!e – ![]() – · · · and, hence, that Pn is the nearest integer to n!e.

– · · · and, hence, that Pn is the nearest integer to n!e.

(c) Show that

![]()

13. For objects of type (2m), that is, of m kinds and two of each kind, the enumerator for r-permutations is

![]()

where qm, r is the number of r-permutations.

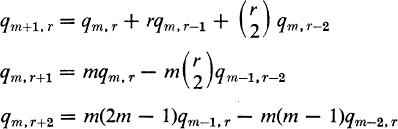

(a) Derive the following recurrences:

Verify the particular results qm, 0 = 1, qm, 1 = m, qm, 2 = m2.

(b) For the total number of permutations, qm = Σqm, r, derive the symbolic expression

![]()

and the recurrence relation

![]()

Verify that q0 = 1, q1 = 3, q2 = 19, q3 = 271.

14. By classifying the permutations with repetition of n distinct objects, show that

![]()

or

![]()

15. Terquem’s problem. For combinations of n numbered things in natural (rising) order, and with f(n, r) the number of r-combinations with odd elements in odd position and even elements in even position, or, what is the same thing, with f(n, r) the number of combinations with an equal number of odd and even elements for r even and with the number of odd elements one greater than the number of even for r odd,

(a) Show that f(n, r) has the recurrence

![]()

(b) ![]()

[(n + r)/2] being the greatest integer not greater than (n + r)/2.

(c) ![]()

The numbers f(n) are Fibonacci numbers, as in Problem 1.

16. Write an,r for the number of r-permutations with repetition of n different things, such that no two consecutive things are alike, and ![]() for the number of these with a given element first. Show that

for the number of these with a given element first. Show that

![]()

![]()

With

![]()

show that

![]()

17. (a) Write bn,r for permutations as in Problem 16 except that no three consecutive things are alike. By use of the corresponding numbers with a given thing first and a given pair of things first, derive the recurrence

![]()

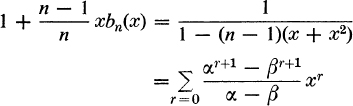

From this and the initial values bn,1 = n, bn,2 = n2, derive the generating function relation

![]()

with

![]()

(b) Show that

with

![]()

Hence,

![]()

18. For permutations as in Problems 16 and 17 and no m consecutive things alike, m = 2, 3, · · · write ![]() and

and ![]() (x) for the numbers and generating functions. Show that

(x) for the numbers and generating functions. Show that

![]()

and, since ![]() = nr, r < m,

= nr, r < m,

![]()