15. Rest of Body Anatomy

Clavicula & Scapula

Fig. 15.1 Clavicula

Right clavicula. A Superior view; B inferior view. The S-shaped clavicula is visible and palpable along its entire length. Its medial end articulates with the sternum at the articulatio sternoclavicularis. Its lateral end articulates with the scapula at the articulatio acromioclavicularis. The clavicula and scapula connect the bones of the upper limb to the cavea thoracis.

Fig. 15.2 Scapula

Right scapula. A Anterior view; B right lateral view; C posterior view. In its normal anatomic position, the scapula extends from the 2nd to the 7th rib.

Humerus & Articulatio Glenohumeralis

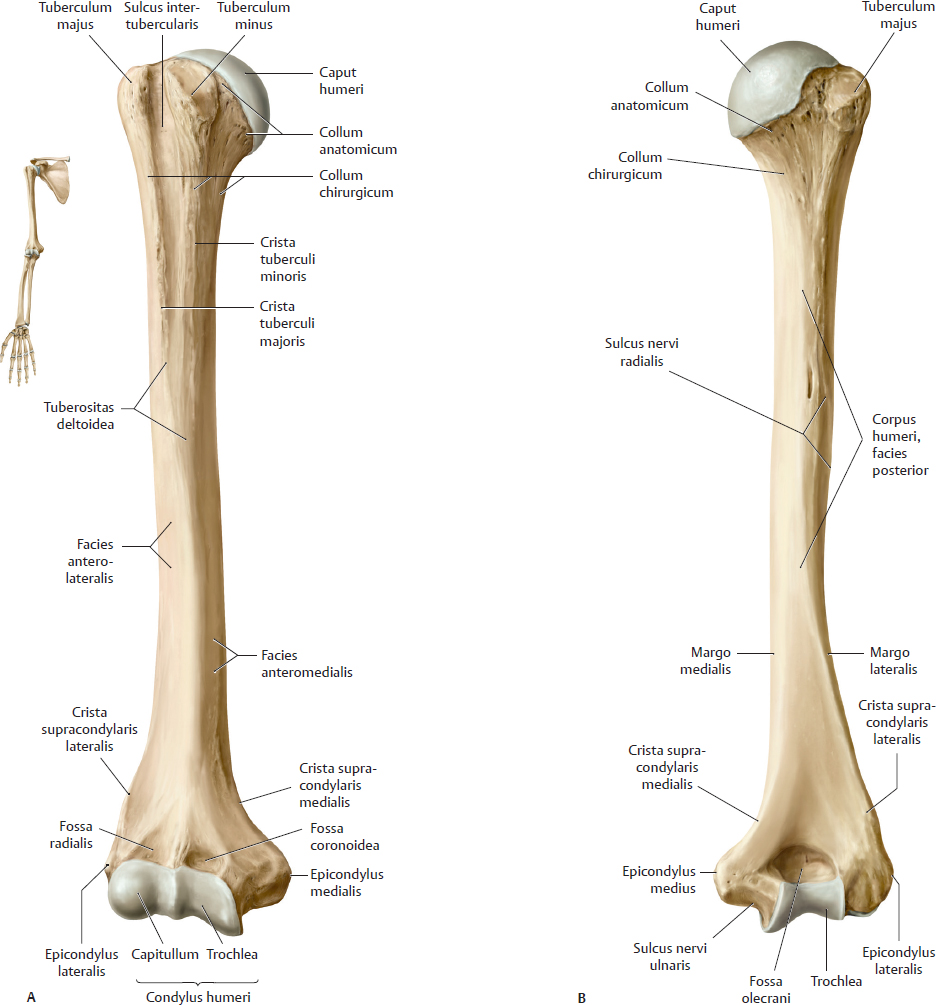

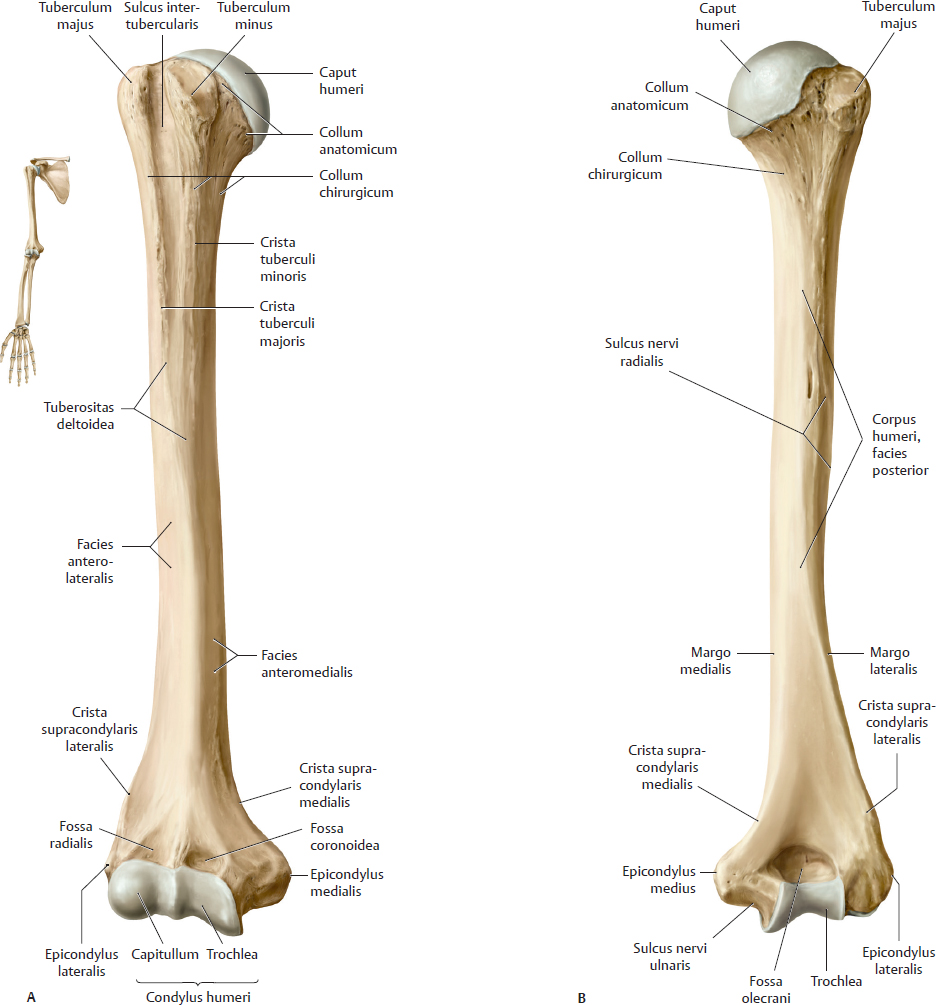

Fig. 15.3 Humerus

Right humerus. A Anterior view. B Posterior view.

The caput humeri articulates with the scapula at the articulatio glenohumeralis. The capitullum and trochlea of the humerus articulate with the radius and ulna, respectively, at the articulatio cubiti.

Fig. 15.4 Articulatio glenohumeralis: Bony elements

Right shoulder. A Anterior view. B Posterior view.

Bones of Forearm, Wrist, & Hand

Fig. 15.5 Radius and Ulna

Right forearm, anterior view. A Supination. B Pronation.

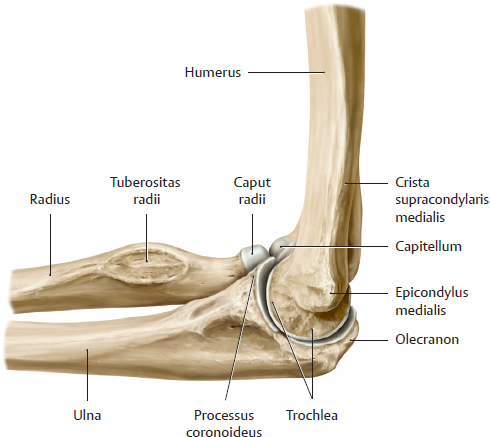

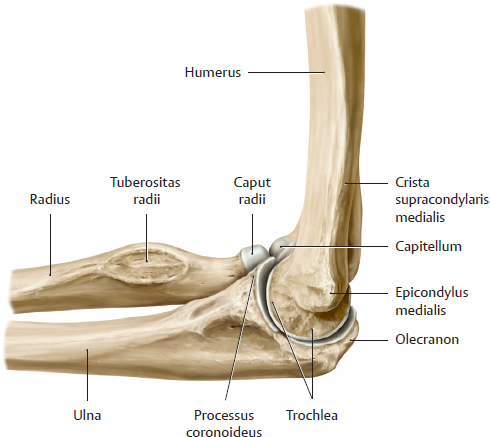

Fig. 15.6 Articulatio cubiti

Right limb. The cubitus consists of three articulations between the humerus, ulna, and radius: the articulationes humeroulnaris, humeroradialis, and radioulnaris proximalis.

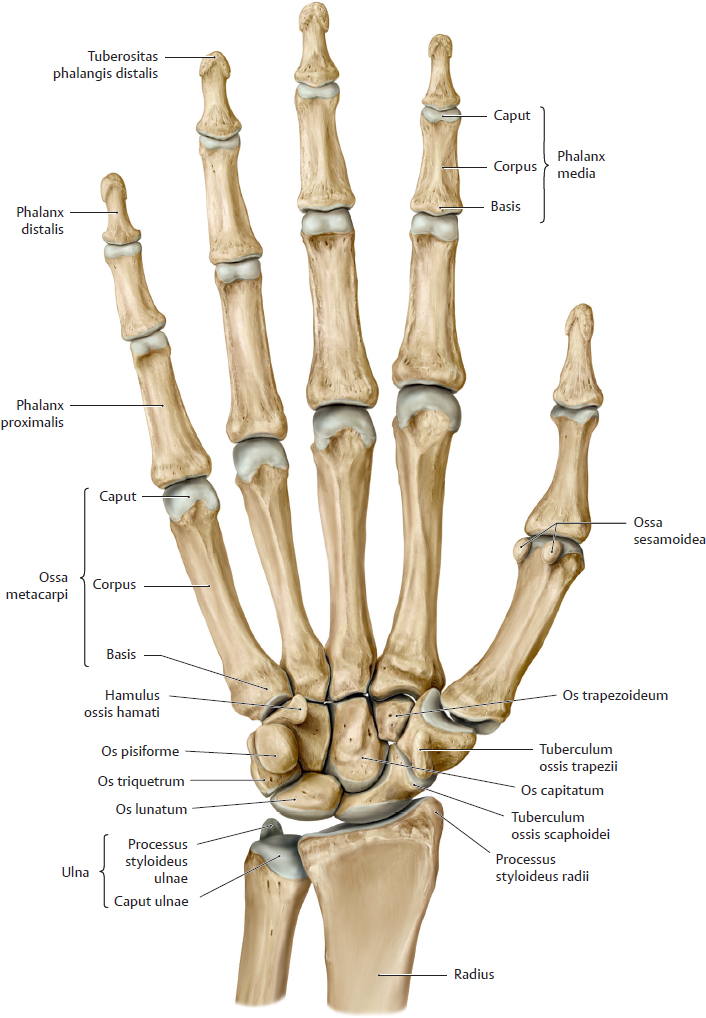

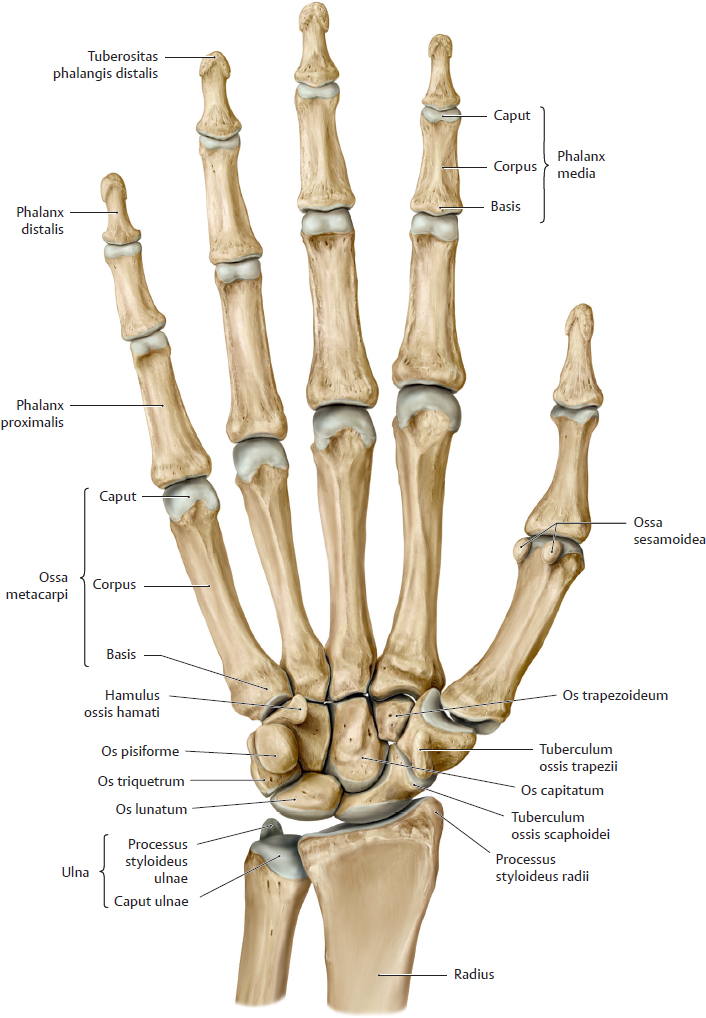

Fig. 15.7 Hand

Right hand, palmar view.

Muscles of the Shoulder (I)

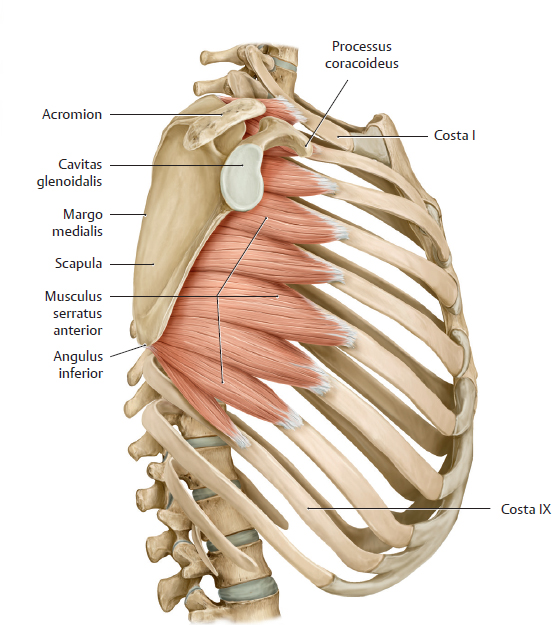

Fig. 15.8 Serratus anterior

Right shoulder. A Anterior view. B Posterior view.

The rotator cuff consists of four muscles: musculi supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis.

Fig. 15.9 Musculi subclavius and pectoralis minor

Right side, anterior view.

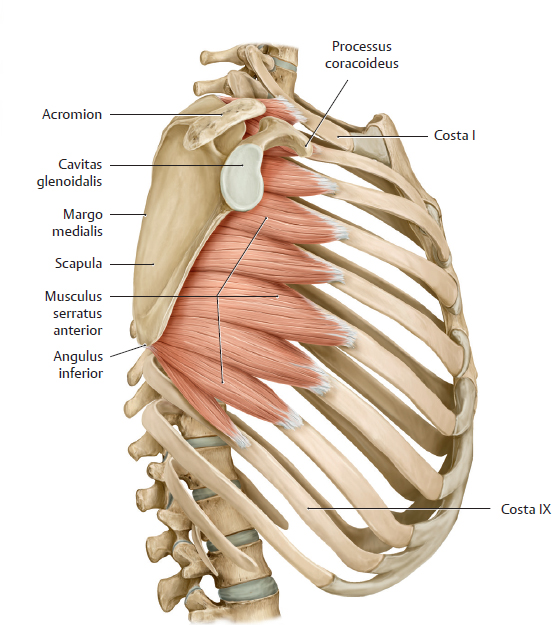

Fig. 15.10 Musculus serratus anterior

Right lateral view.

Muscles of the Shoulder (II) & Arm

Fig. 15.11 Musculi pectoralis major and coracobrachialis

Anterior view.

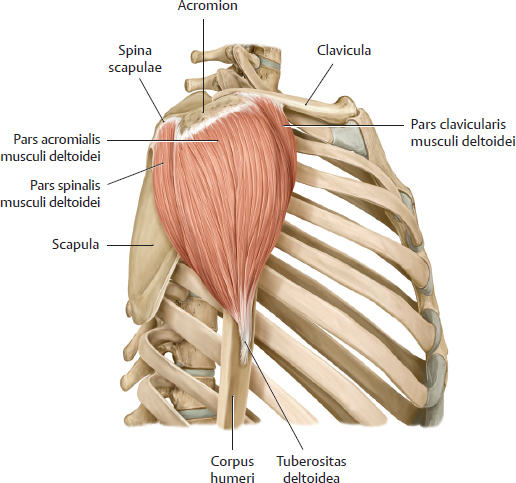

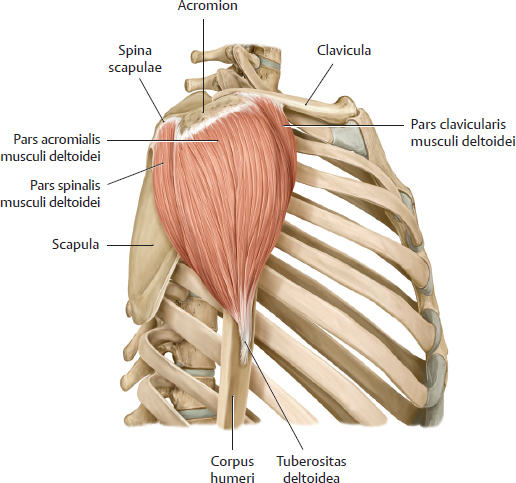

Fig. 15.12 Musculus deltoideus

Right shoulder, right lateral view.

Fig. 15.13 Right shoulder, right lateral view.

Right arm, anterior view.

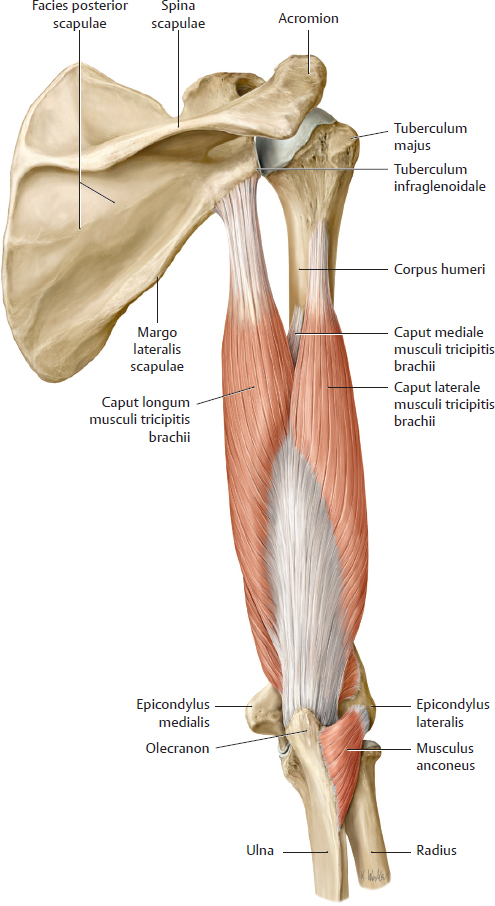

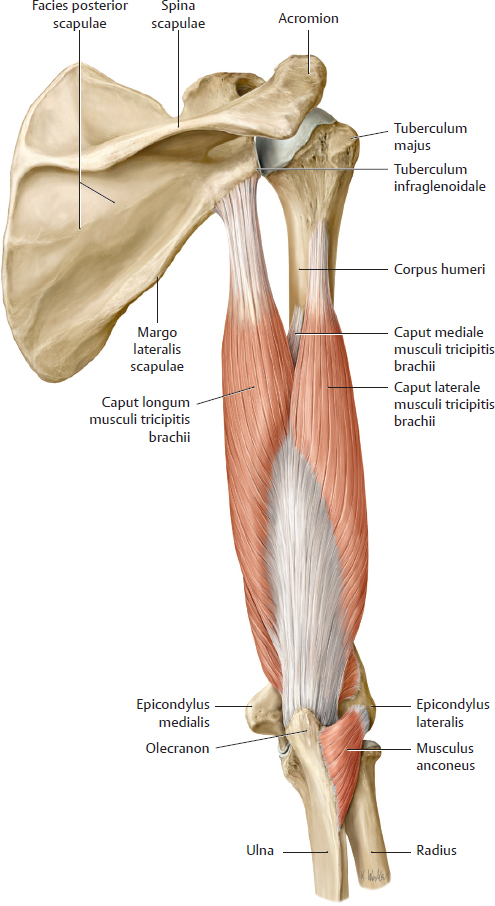

Fig. 15.14 Musculi triceps brachii and anconeus

Right arm, posterior view.

Muscles of the Forearm

Fig. 15.15 Muscles of the posterior compartment of the forearm

Right forearm, posterior view.

A, B Superficial extensors. C Deep extensors with supinator.

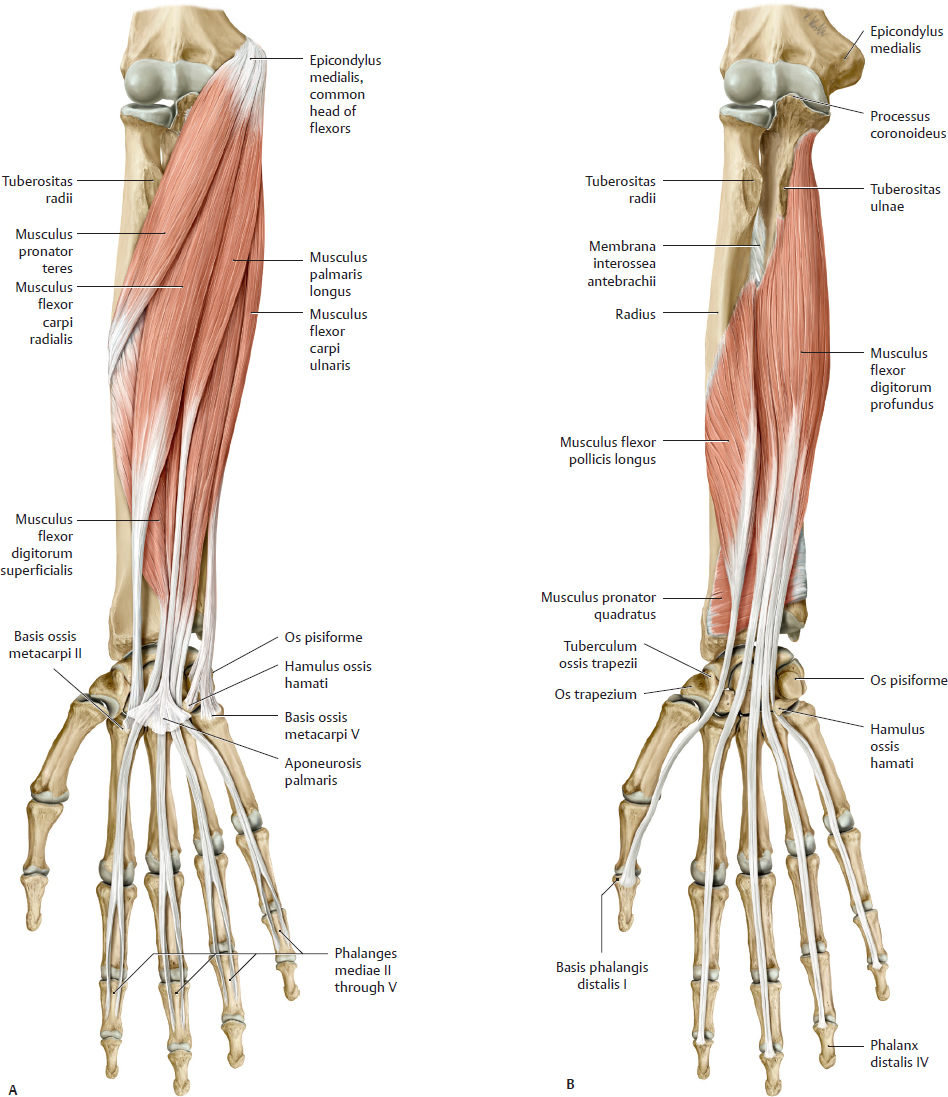

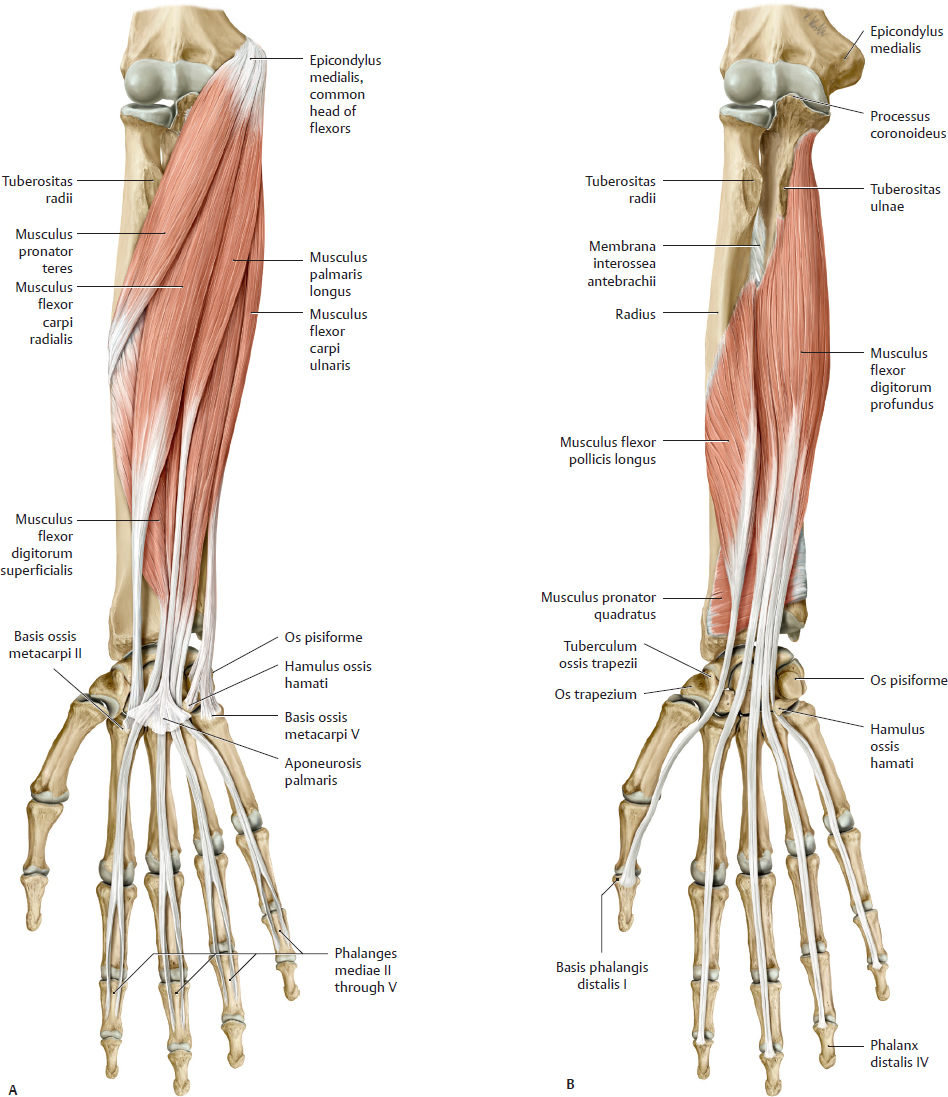

Fig. 15.16 Muscles of the anterior compartment of the forearm

Right forearm, anterior view.

A Superficial and intermediate muscles.

B Deep muscles.

Muscles of the Wrist & Hand

Fig. 15.17 Thenar and hypothenar muscles

Right hand, palmar (anterior) view.

A Removed: Musculi flexor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis, and flexor digiti minimi brevis.

B Removed: Musculi adductor pollicis, abductor pollicis brevis, abductor digiti minimi, and opponens digiti minimi.

Fig. 15.18 Metacarpal muscles

Right hand, palmar (anterior) view.

A Musculi lumbricales.

B Musculi interossei dorsales.

C Musculi interossei palmares.

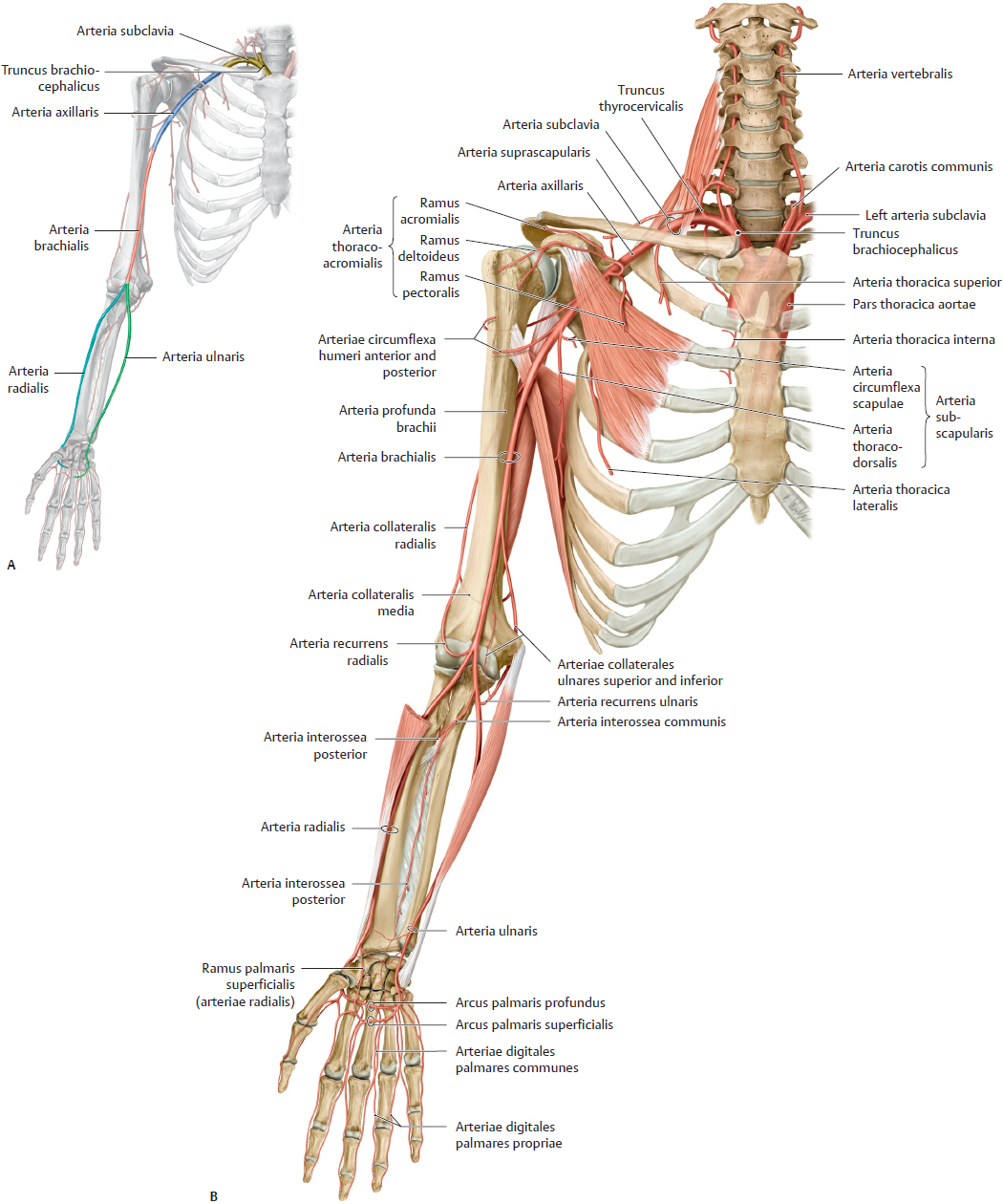

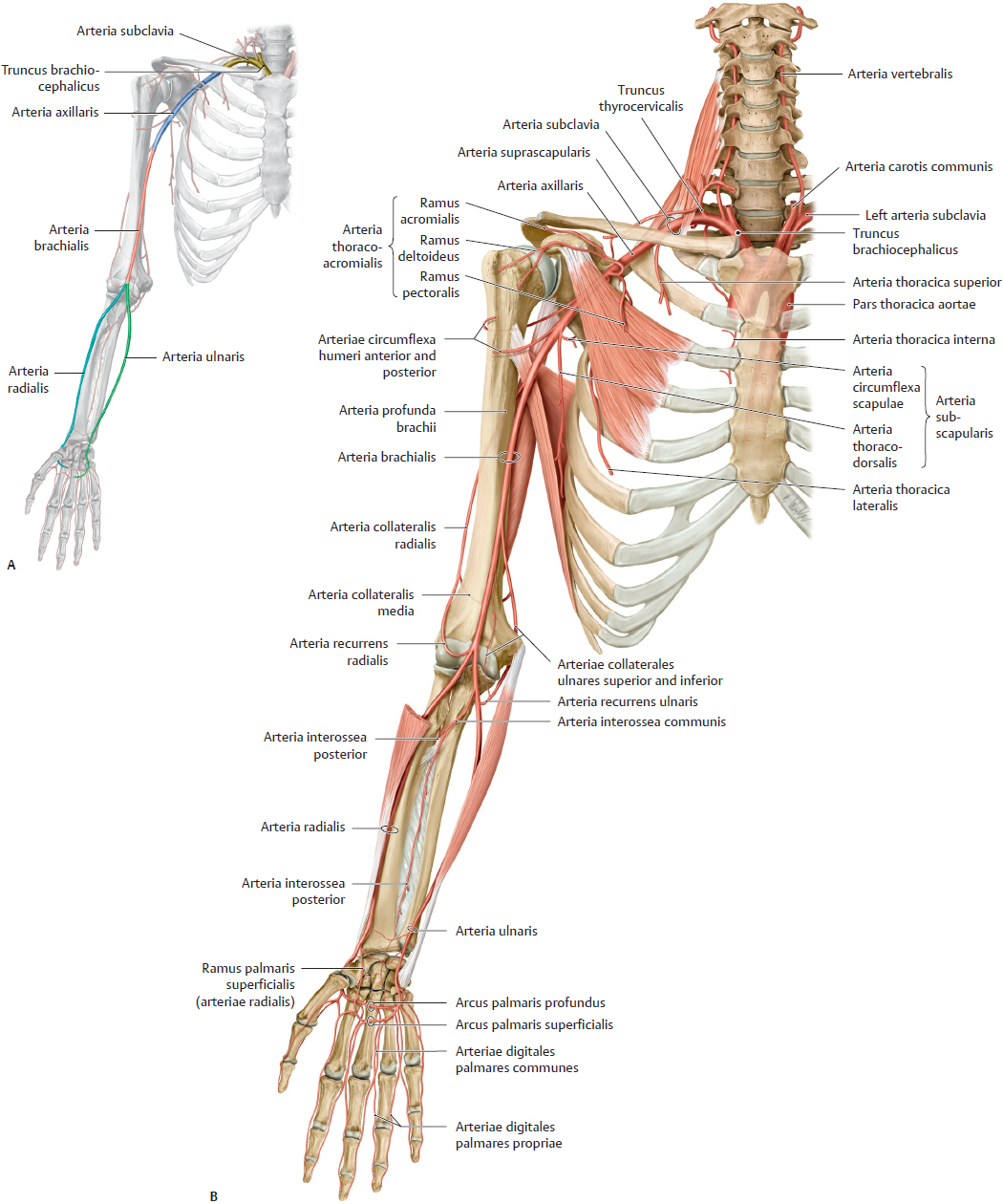

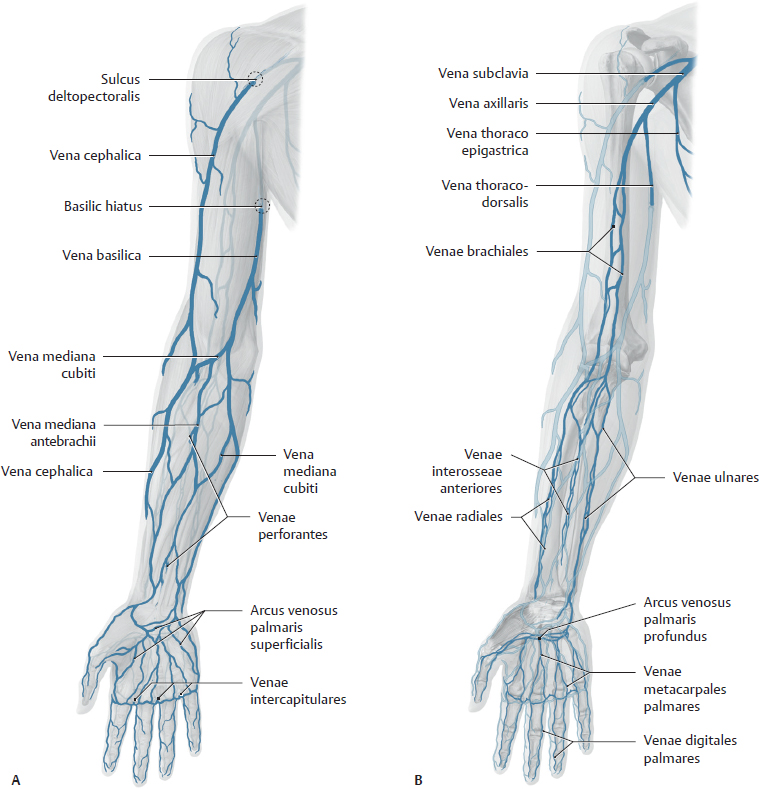

Arteries & Veins of the Upper Limb

Fig. 15.19 Arteries of the upper limb

Right limb, anterior view.

A Main arterial segments.

B Course of the arteries.

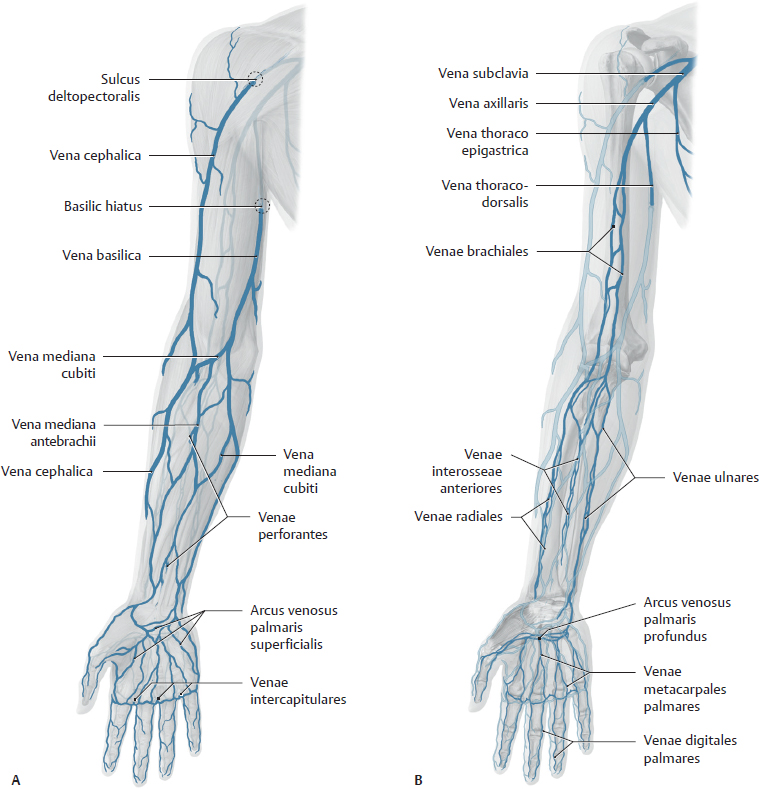

Fig. 15.20 Veins of the upper limb

Right limb, anterior view.

A Superficial veins.

B Deep veins.

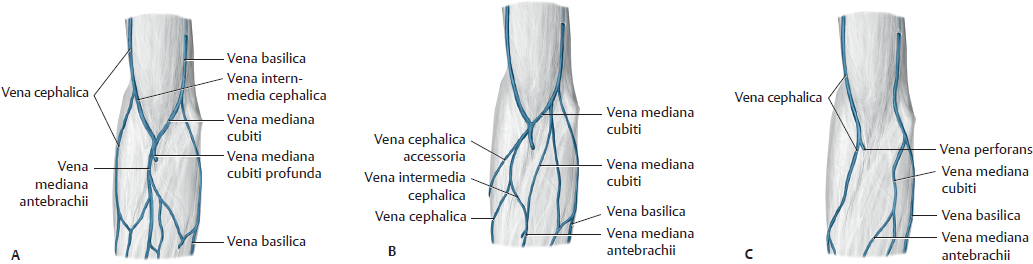

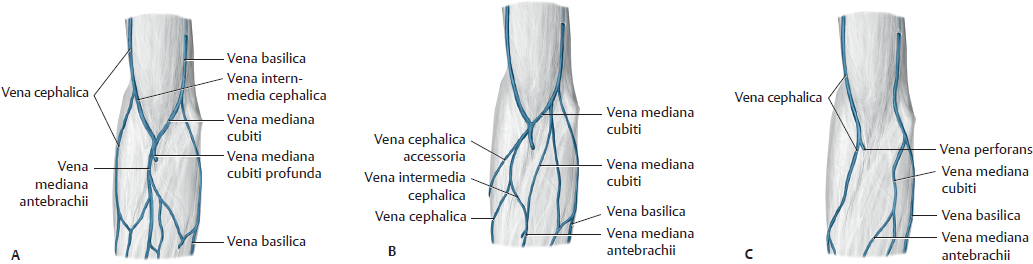

Fig. 15.21 Veins of the fossa cubitalis

Right limb, anterior view. The subcutaneous veins of the fossa cubitalis have a highly variable course.

A M-shaped.

B With vena cephalica accessoria.

C Without vena mediana cubiti.

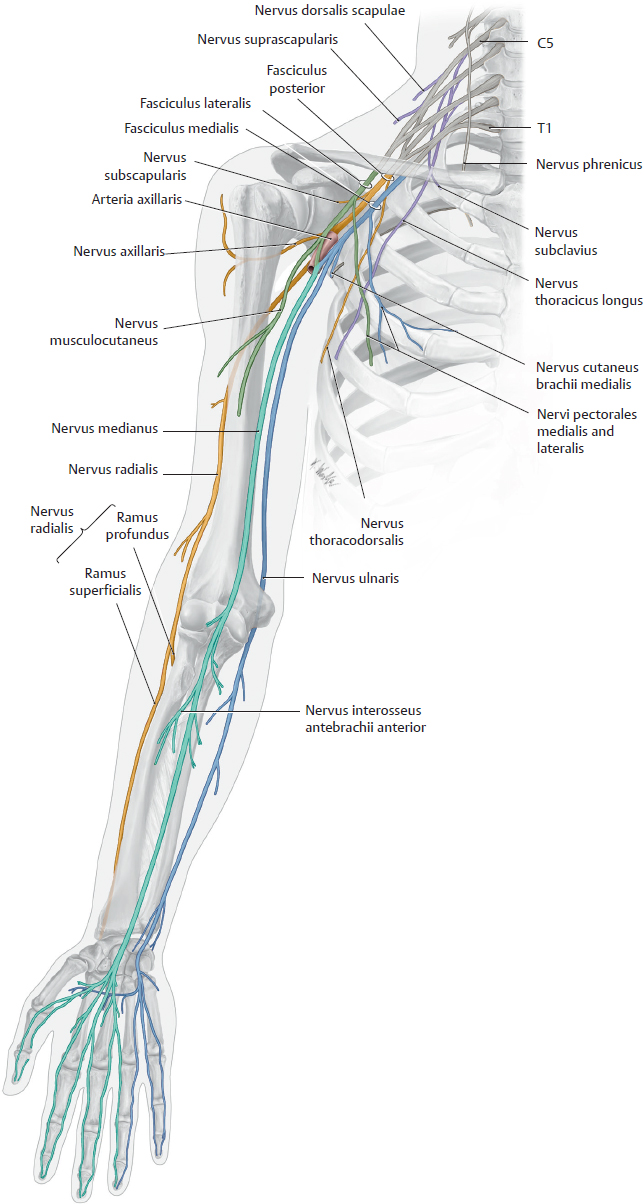

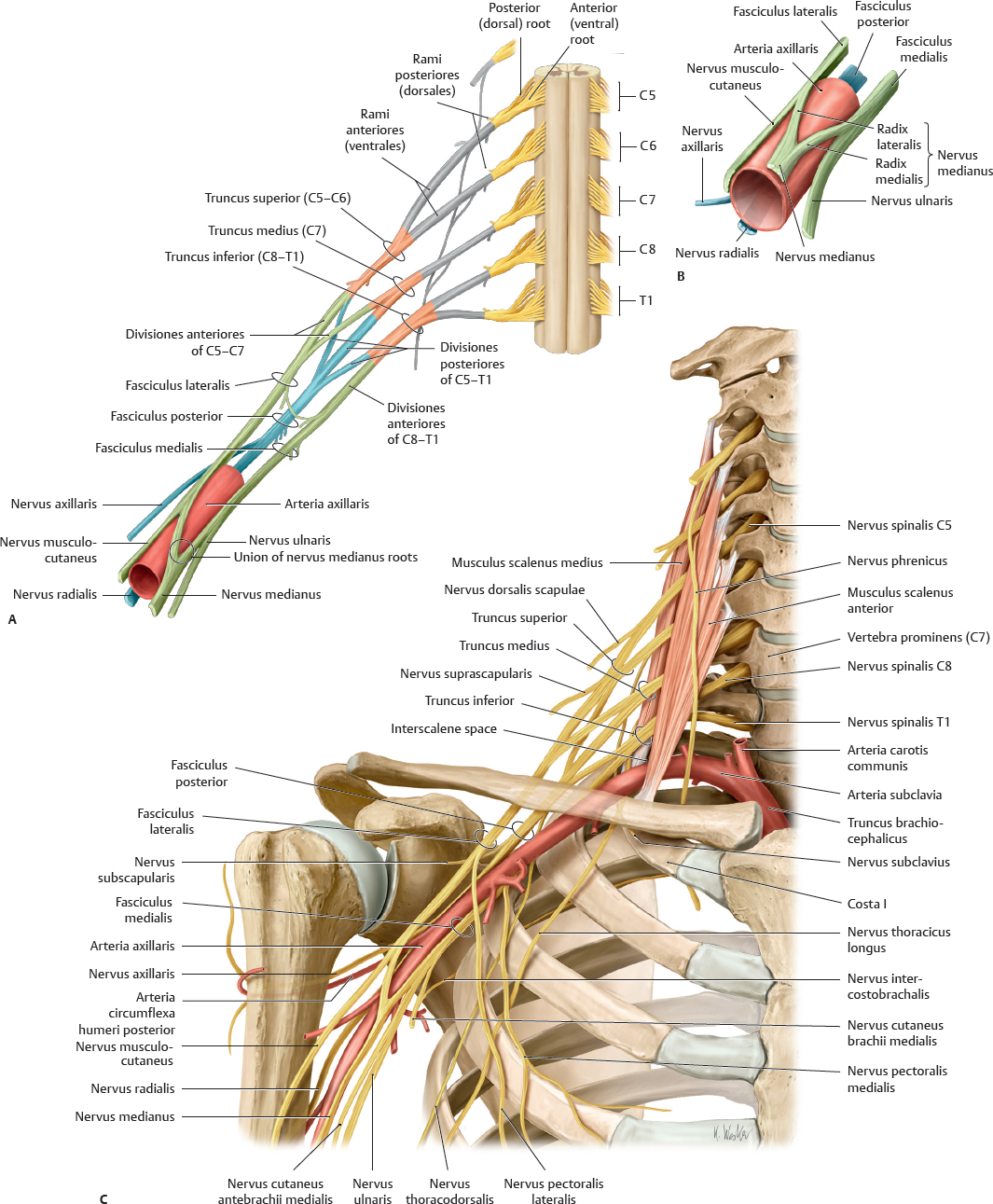

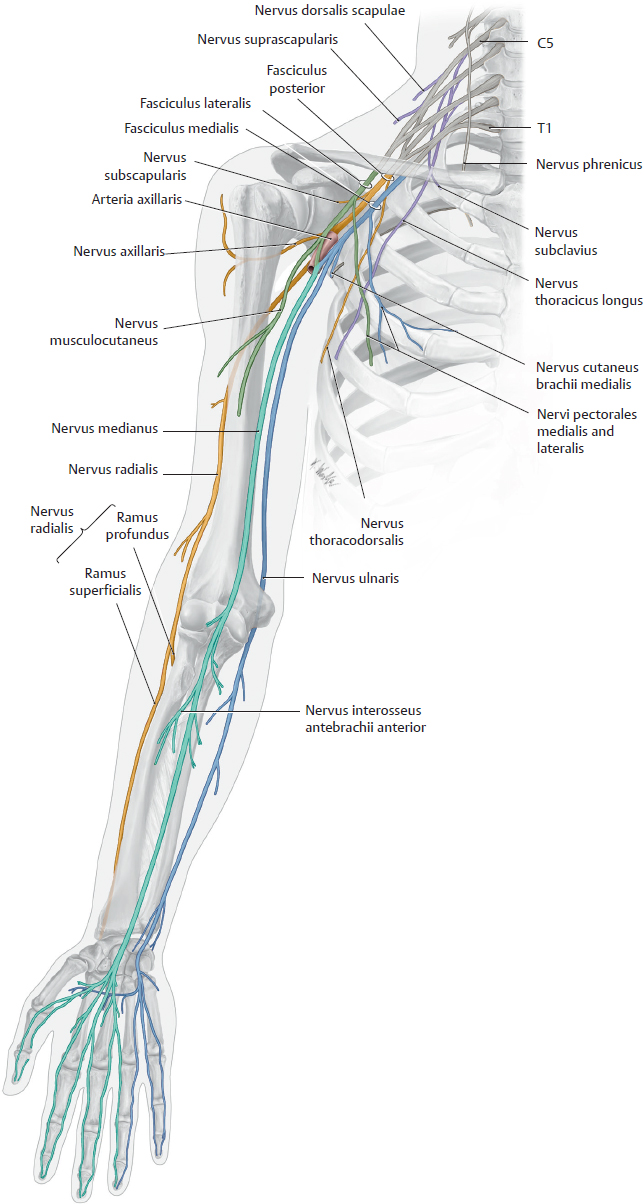

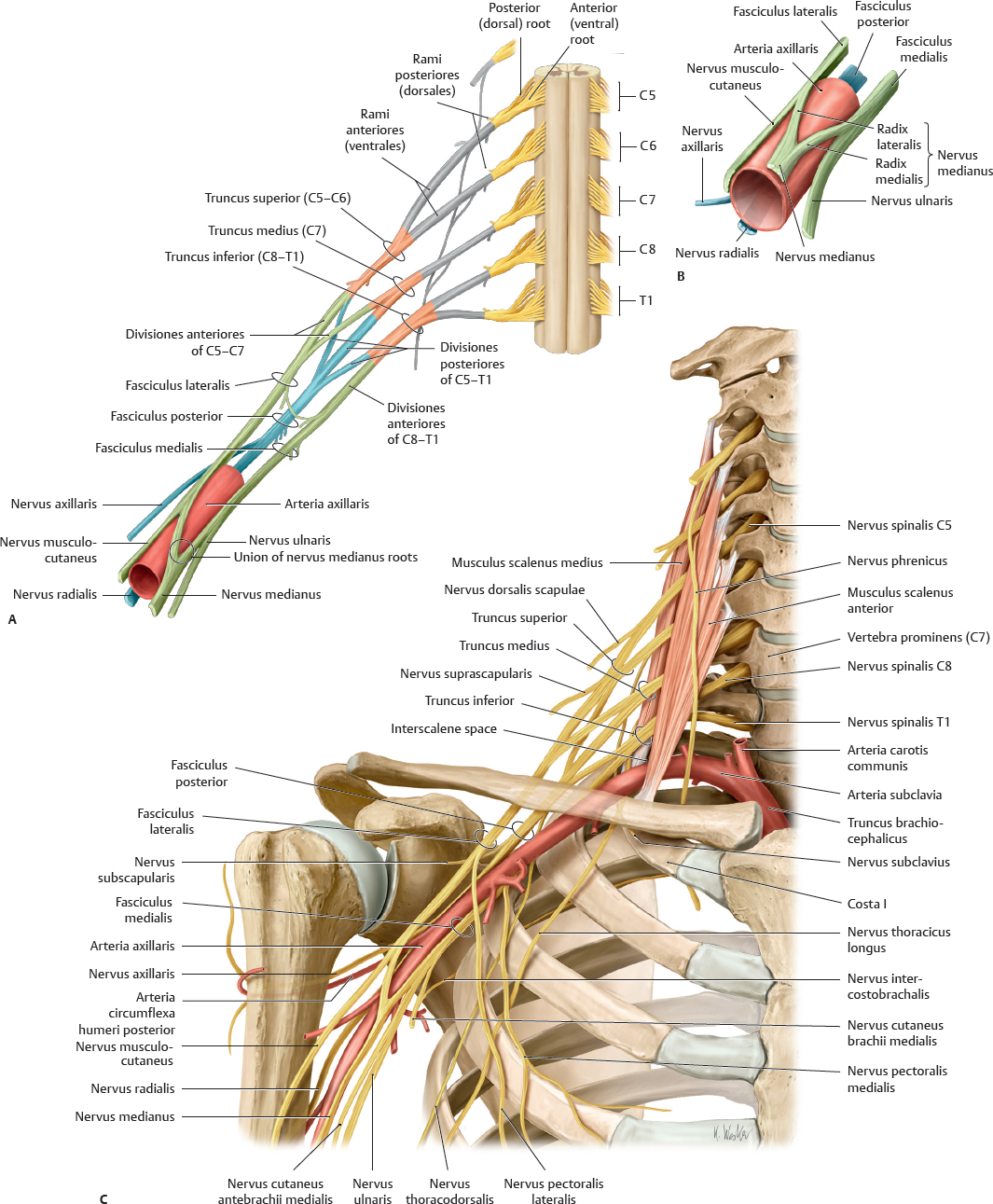

Plexus Brachialis

Almost all muscles in the upper limb are innervated by the plexus brachialis, which arises from segments C5 to T1 of medulla spinalis. The rami anteriores of the nervi spinales give off direct branches (pars supraclavicularis of the plexus brachialis) and merge to form three trunci, six divisiones (three anterior and three posterior), and three fasciculi. The pars infraclavicularis of the plexus brachialis consists of short branches that arise directly from the fasciculi and long (terminal) branches that traverse the limb.

Fig. 15.22 Plexus brachialis and its branches in the upper limb

Right side, anterior view.

Fig. 15.23 Plexus brachialis

Right side, anterior view.

A Structure of the plexus brachialis.

B Division of the fasciculi into terminal branches.

C Course of the plexus brachialis, stretched for clarity

Skeleton Thoracis

Fig. 15.24 Skeleton thoracis

A Anterior view. B Left lateral view. C Posterior view.

Fig. 15.25 Structure of a thoracic segment

Superior view of 6th rib pair.

Fig. 15.26 Ribs

Right ribs, superior view.

Muscles & Neurovascular Topography of the Thoracic Wall

Fig. 15.27 Muscles of the thoracic wall

Anterior view. The musculi intercostales externi are replaced anteriorly by the Membrana intercostalis externa. The musculi intercostales interni are replaced posteriorly by the membrana intercostalis interna (removed in Fig. 15.28).

Fig. 15.28 Transversus thoracis

Anterior view with cavea thoracica opened to expose posterior surface of anterior wall.

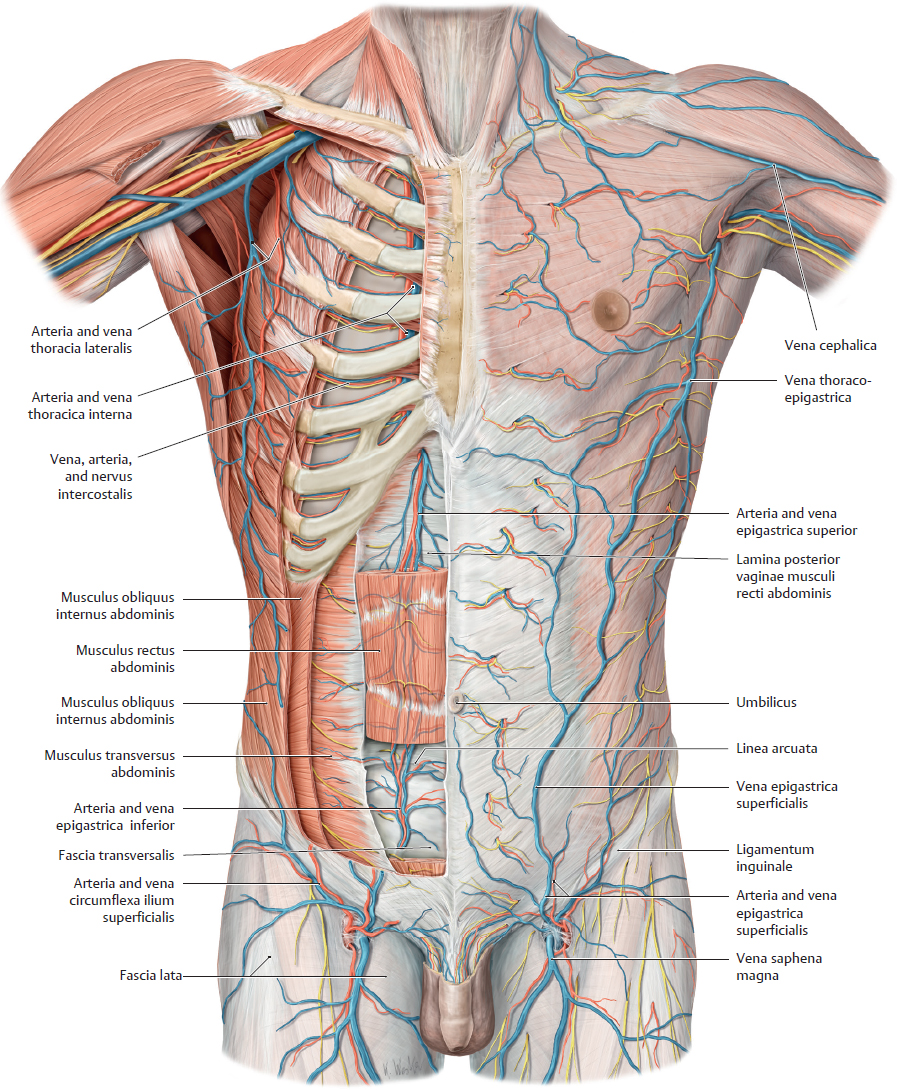

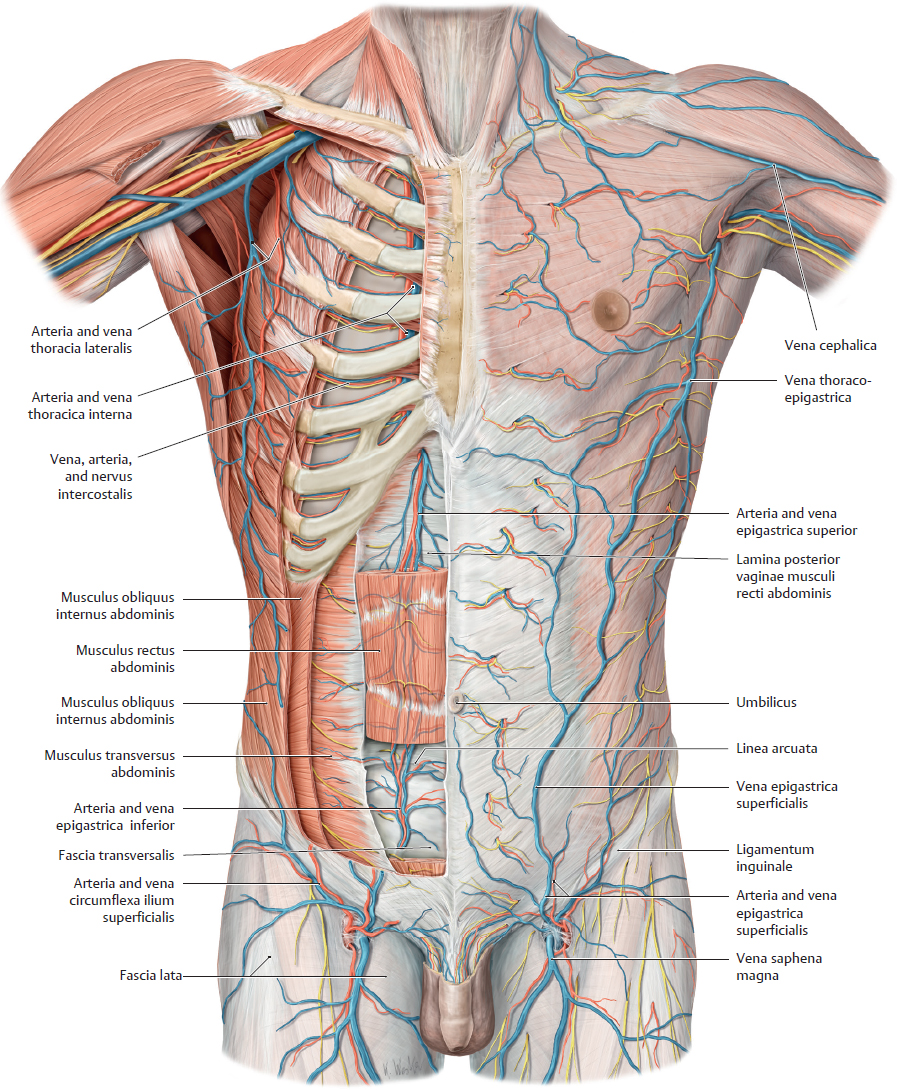

Fig. 15.29 Neurovascular structures on the anterior side of the anterior trunk wall

Anterior view. The superficial (subcutaneous) neurovascular structures are demonstrated on the left side of the trunk and the deep neurovascular structures on the right side.

Removed on right side: musculi pectorales major and minor, musculi obliqui externi and interni abdominis (partially removed), musculus rectus abdominis (partially removed or rendered transparent). The spatia intercostales have been exposed to display the course of the intercostal vessels and nerves.

Note: The intercostal vessels run in the sulcus costae. From superior to inferior they are vein, artery, and nerve.

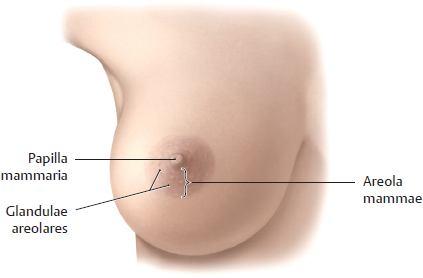

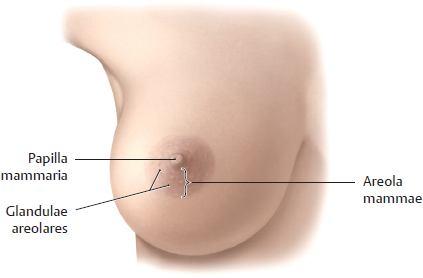

Female Breast

The female breast, a modified sweat gland in the subcutaneous tissue layer, consists of glandular tissue, fibrous stroma, and fat. The breast extends from the 2nd to the 6th rib and is loosely attached to the pectoral, axillary, and superficial abdominal fascia by connective tissue. The breast is additionally supported by suspensory ligaments. An extension of the breast tissue into the axilla, the axillary tail, is often present.

Fig. 15.30 Female breast

Right breast, anterior view.

Fig. 15.31 Mammary ridges

Rudimentary glandula mammaria form in both sexes along the mammary ridges. Occasionally, these may persist in humans to form accessory nipples (polythelia), although only the thoracic pair normally remains.

Fig. 15.32 Blood supply to the breast

Fig. 15.33 Sensory innervation of the breast

Fig. 15.34 Structures of the breast

A Sagittal section along linea mediclavicularis. B Duct system and portions of a lobe, sagittal section. In the nonlactating breast (shown here), the lobuli contain clusters of rudimentary acini. C Terminal duct lobular unit (TDLU). The clustered acini composing the lobulus empty into a terminal ductule; these structures are collectively known as the TDLU.

The glandular tissue is composed of 10 to 20 individual lobi, each with its own ductus lactiferus. The gland ducts open on the elevated papilla mammaria at the center of the pigmented areola. Just proximal to the duct opening is a dilated portion called the sinus lactiferus. Areolar elevations are the openings of the glandulae areolares (sebaceous). The glands and ductus lactiferi are surrounded by firm, fibrofatty tissue with a rich blood supply.

The most common type of breast cancer, invasive ductal carcinoma, arises from the lining of the ductus lactiferi. Typically it metastasizes through lymphatic channels, most abundantly to nodi lymphoidei axillares, but it may also travel to nodi supraclaviculares, the contralateral breast and the abdomen. Obstruction of the lymphatic drainage and fibrosis (shortening) of the ligamenta suspensoria can cause a leathery (peau d’ orange) and dimpled appearance of the skin. Because the venae intercostales that drain the breast communicate with the azygos system and through that the plexus venosi vertebrales, breast cancer can spread to the vertebrae, cranium and brain. Elevation of the breast with contraction of the musculus pectoralis major suggests invasion of the retromammary space.

Fig. 15.35 Lymphatic drainage of the breast

The lymphatic vessels of the breast (not shown) are divided into three systems: superficial, subcutaneous, and deep. These drain primarily into the nodi lymphoidei axillares, which are classified based on their relationship to the pectoralis muscle as Levels I, II, and III. Level I is lateral to musculus pectoralis major; Level II is along this muscle; Level III is medial to it. The medial portion of the breast is drained by the nodi lymphoidei parasternales, which are associated with the internal thoracic vessels.

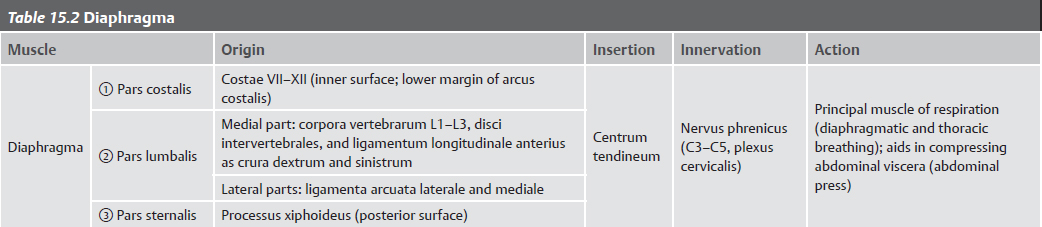

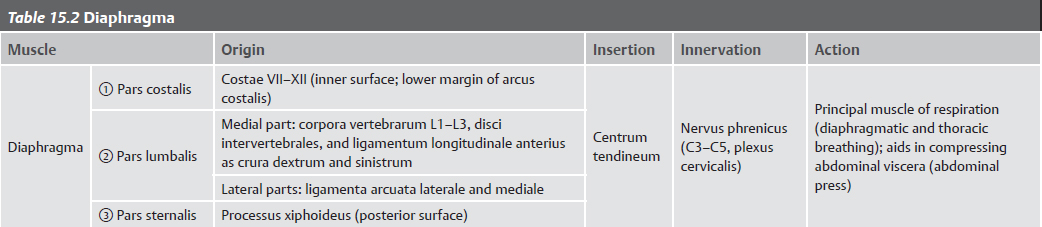

Diaphragma

Fig. 15.36 Diaphragma

A Anterior view.

B Posterior view.

C Coronal section with diaphragma in intermediate position.

The diaphragma, which separates the thorax from the abdomen, has two asymmetric domes and three apertures (for the aorta, vena cava, and oesophagus; see C).

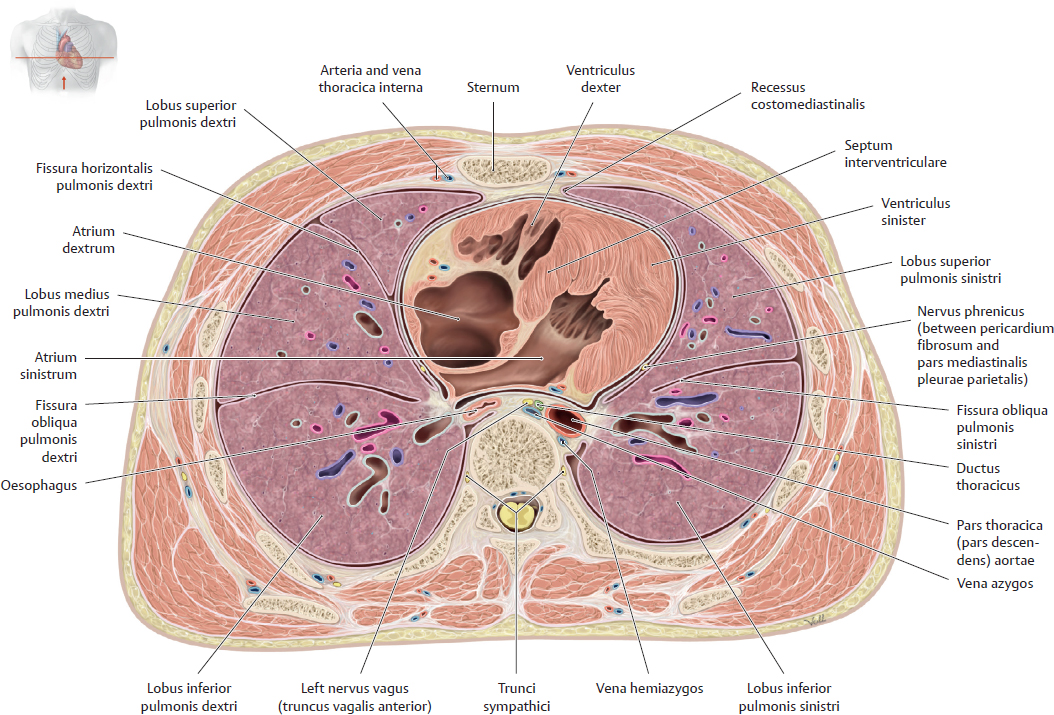

Fig. 15.37 Thoracic section

Transverse section, anterosuperior view.

Neurovasculature of the Diaphragma

Fig. 15.38 Neurovasculature of the diaphragma

Anterior view of opened cavea thoracica.

Fig. 15.39 Innervation of the diaphragma

Anterior view. The nervi phrenici lie on the lateral surfaces of the pericardium fibrosum together with the arteriae and venae pericardiacophrenicae. Note: The nervi phrenici also innervate the pericardium.

Fig. 15.40 Arteries and nerves of the diaphragma

A Superior view.

B Inferior view. Removed: Peritoneum parietale.

Note: The margins of the diaphragma receive sensory innervation from the lowest nervi intercostales.

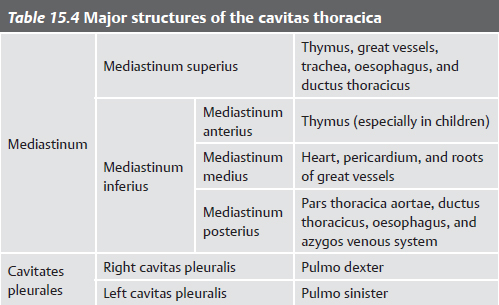

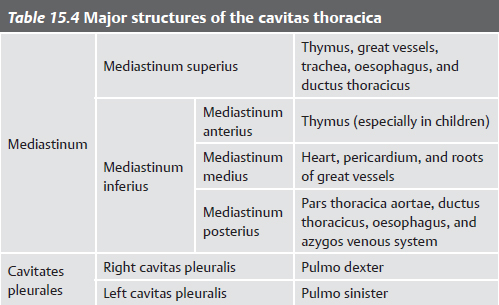

Divisions of the Cavitas Thoracis & Lymphatics

Fig. 15.41 Cavitas thoracica

Coronal section, anterior view.

A Divisions of the cavitas thoracica. The cavitas thoracica is divided into three large spaces, the mediastinum (p. 418) and the two cavitates pleurales (p. 432).

B Opened cavitas thoracica. Removed: Thoracic wall; connective tissue of mediastinum anterius

Fig. 15.42 Trunci lymphatici in the thorax

Anterior view of opened thorax.

The body’s chief lymph vessel is the ductus thoracicus. Beginning in the abdomen at the level of L1 as the cisterna chyli, the ductus thoracicus empties into the junction of the left venae jugularis interna and subclavia. The ductus lymphaticus dexter drains to the right junction of the venae jugularis interna and subclavia.

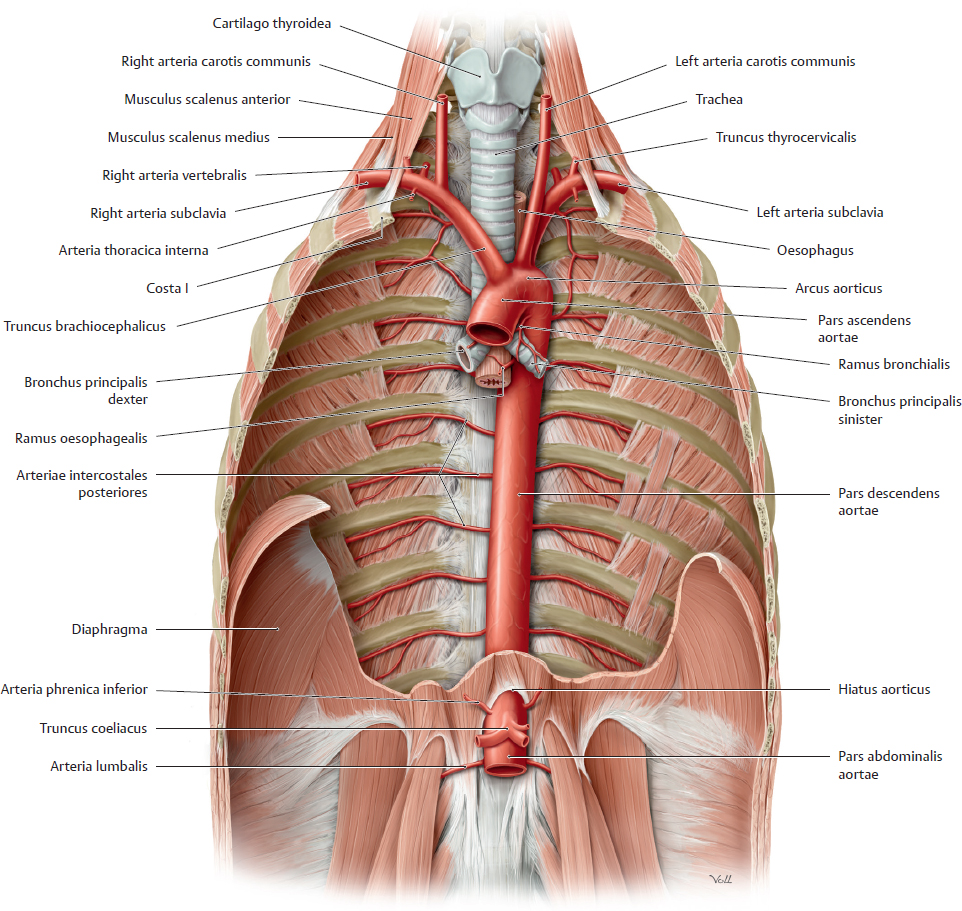

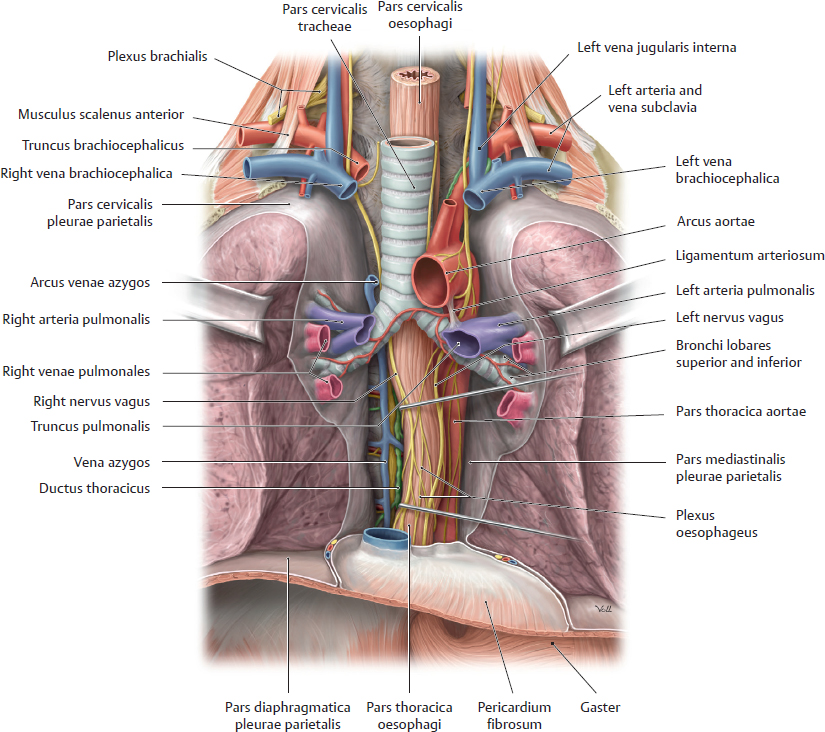

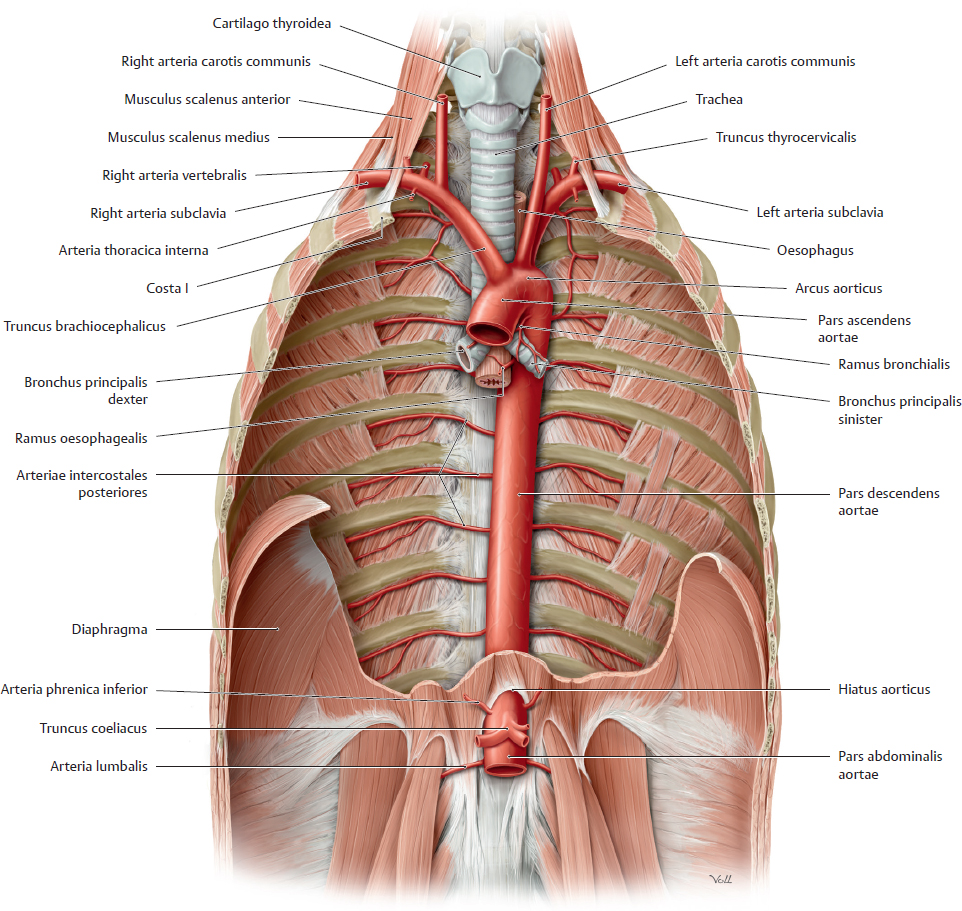

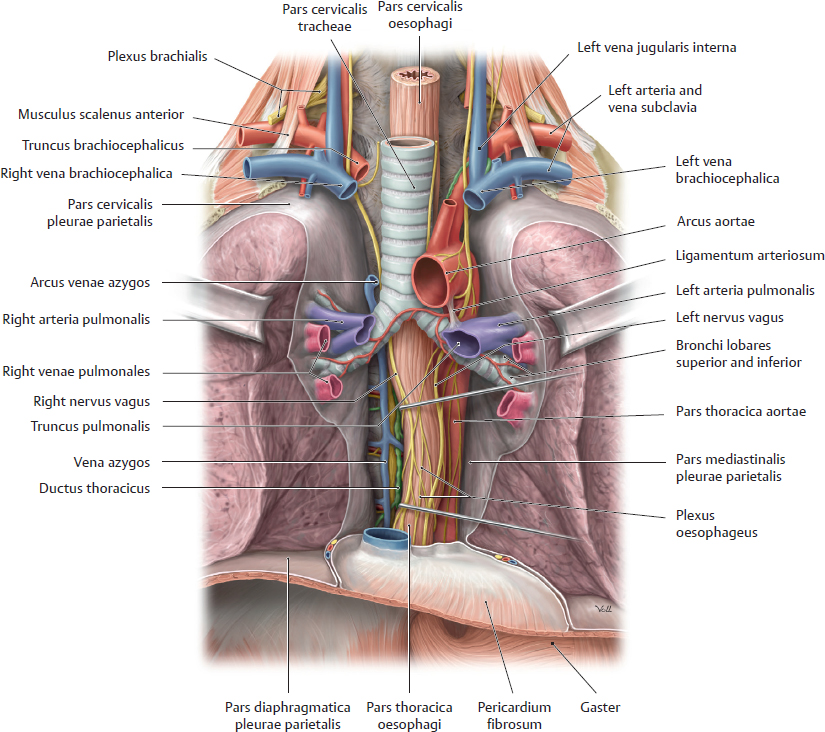

Thoracic Vasculature

Fig. 15.43 Pars thoracica aortae in situ

Anterior view. Removed: Heart, lungs, and portions of the diaphragma.

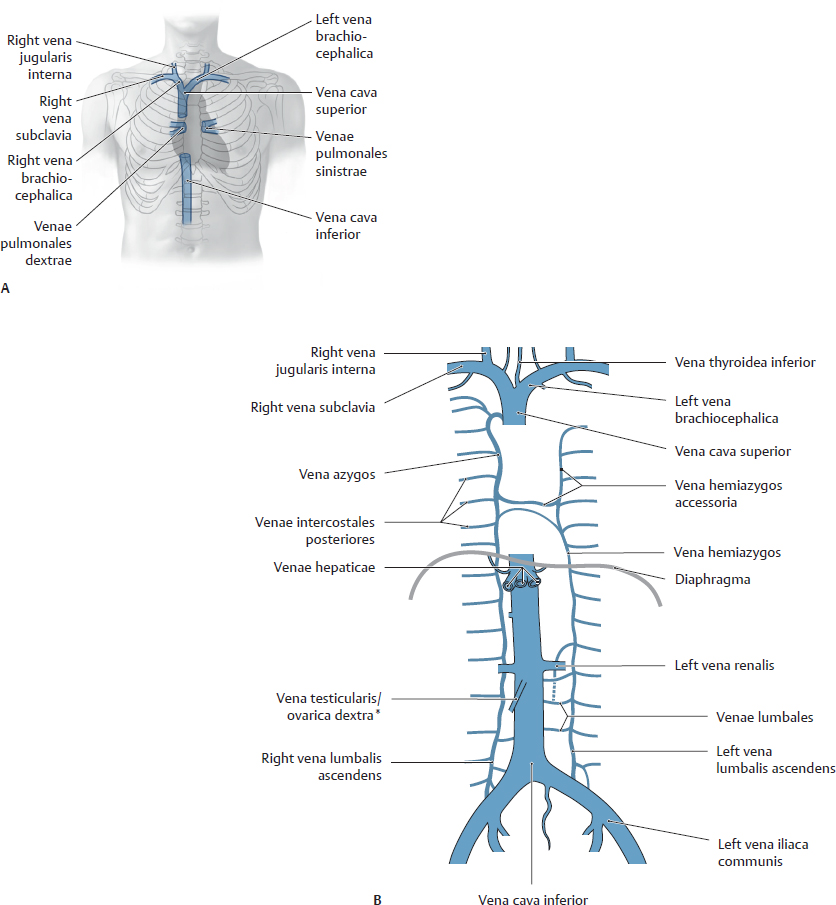

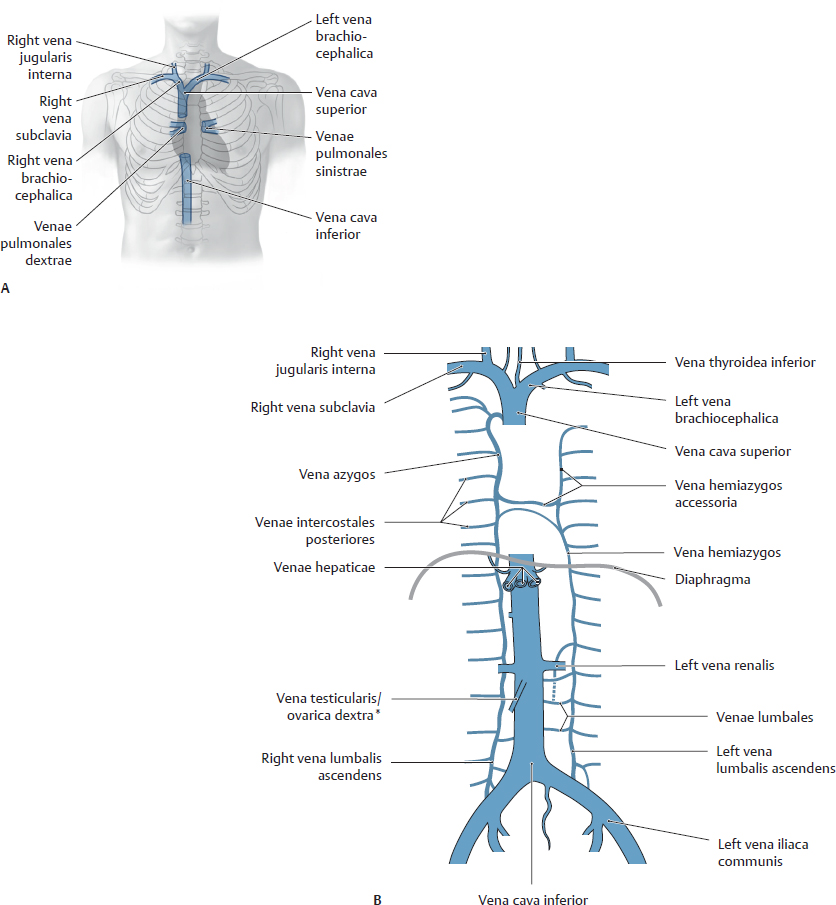

Fig. 15.44 Vena cava superior

Anterior view. A Projection of venae cavae onto chest. B Veins of the cavitas thoracica.

Nerves of the Cavitas Thoracis

Fig. 15.45 Nerves in the thorax

Anterior view of opened thorax.

Thoracic innervation is mostly autonomic, arising from the paravertebral trunci sympathici and parasympathetic nervi vagi. There are two exceptions: the nervi phrenici innervate the pericardium and diaphragma and the nervi intercostales innervate the thoracic wall.

A Thoracic innervation.

B Nerves of the thorax in situ. Note: The nervi laryngei recurrentes have been slightly anteriorly retracted; normally, they occupy the groove between the trachea and the oesophagus, making them vulnerable during glandula thyroidea surgery.

Fig. 15.46 Sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems in the thorax

The autonomic nervous system innervates smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, and glands. It is subdivided into the sympathetic (red) and parasympathetic (blue) nervous systems, which together regulate blood flow, secretions, and organ function.

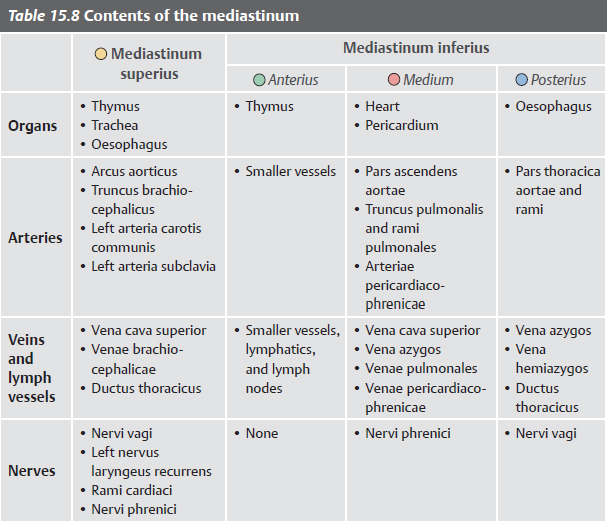

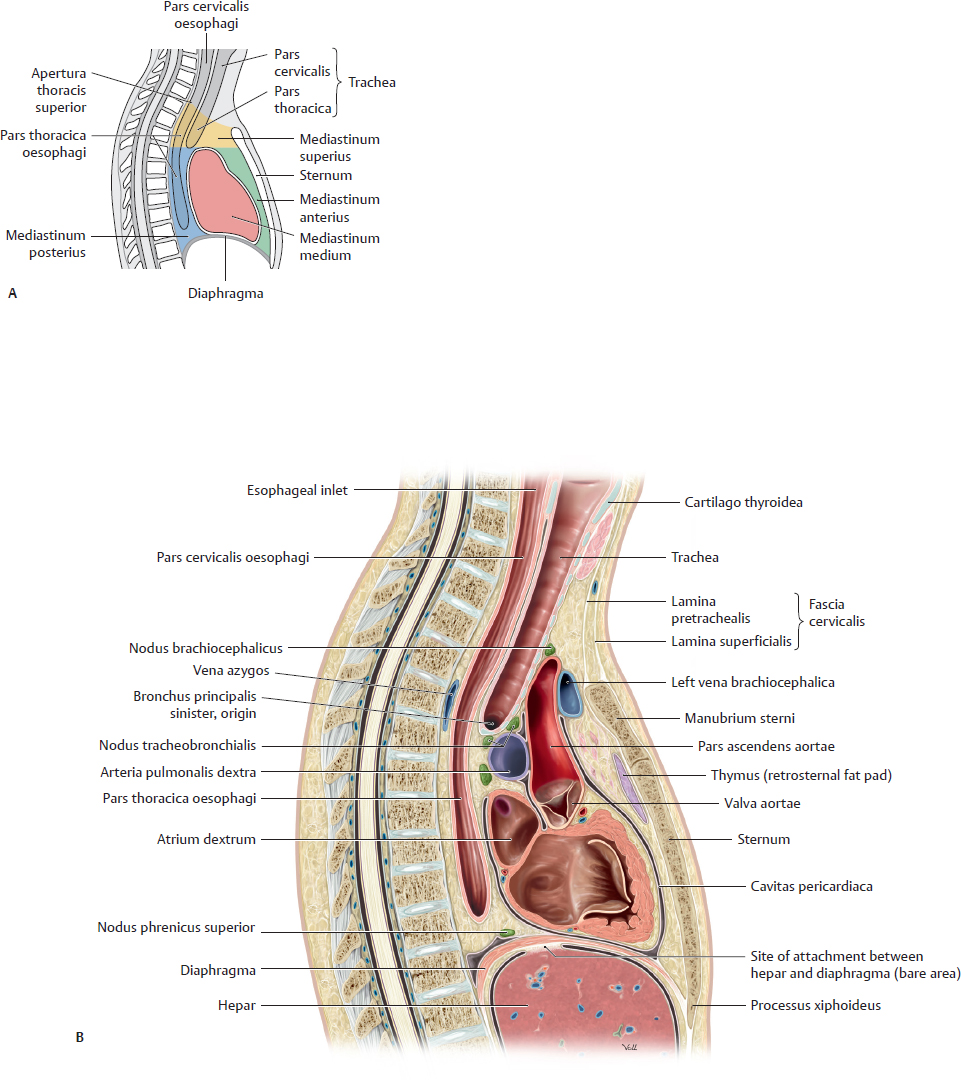

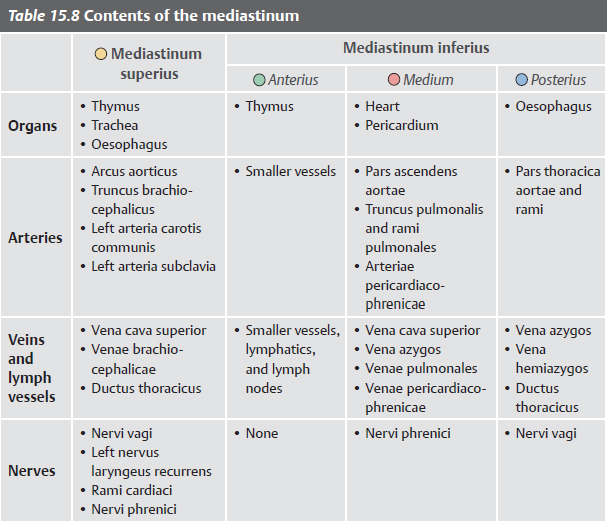

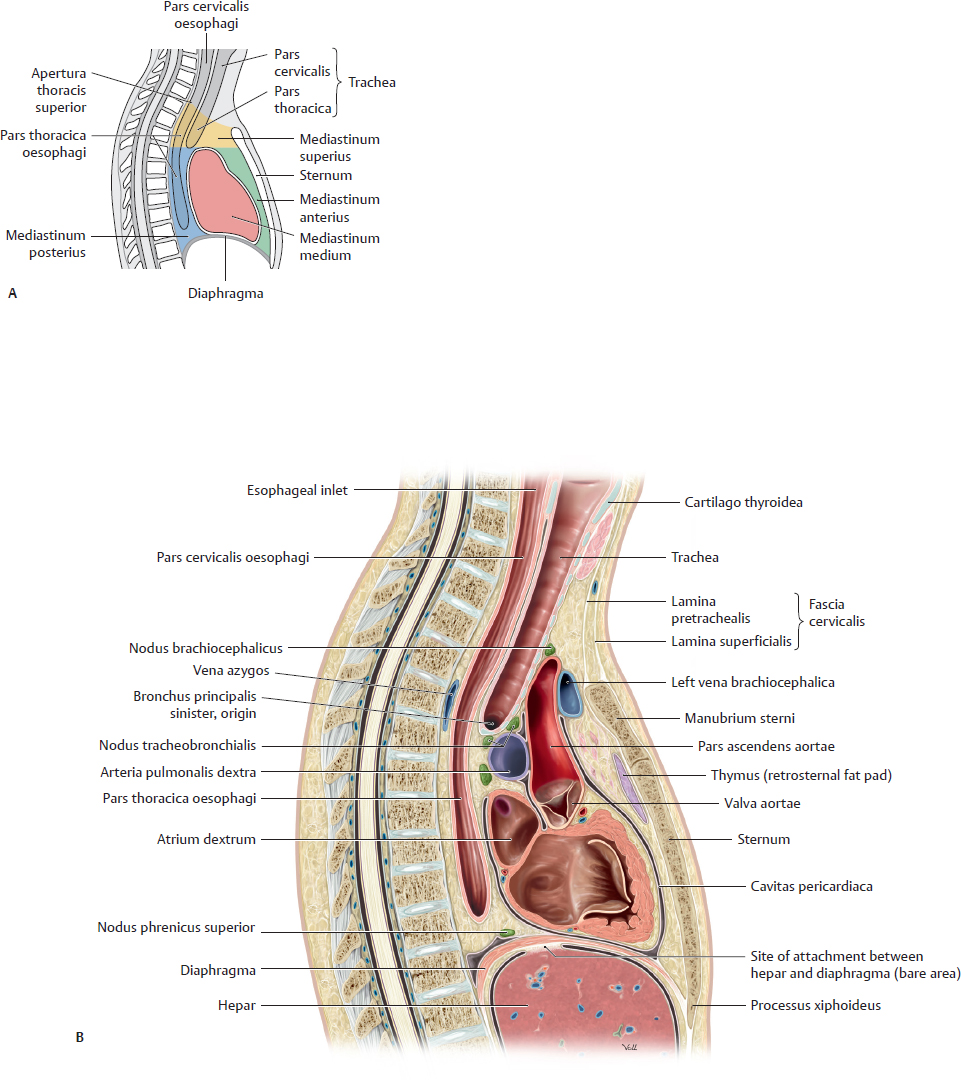

Mediastinum: Overview

The mediastinum is the space in the thorax between the pleural sacs of the lungs. It is divided into two parts: superius and inferius. The mediastinum inferius is further divided into anterior, middle, and posterior portions.

Fig. 15.47 Divisions of the mediastinum

A Schematic. B Midsagittal section, right lateral view.

Fig. 15.48 Contents of the mediastinum

A Anterior view. The thymus, which lies on the pericardium fibrosum surrounding the heart, extends into the mediastinum inferius and grows throughout childhood. At puberty, high levels of circulating sex hormones cause the thymus to atrophy leaving the smaller adult thymus, which extends as shown only into the mediastinum superius.

B Anterior view with heart, pericardium, and thymus removed.

C Posterior view.

Mediastinum: Structures

Fig. 15.49 Mediastinum

A Right lateral view, parasagittal section. Note the many structures passing between the superior and inferior (middle and posterior) mediastinum.

B Left lateral view, parasagittal section. Removed: Pulmo sinister and pleura parietalis. Revealed: Posterior mediastinal structures.

Heart: Surfaces & Chambers

Fig. 15.50 Surfaces of the heart

A Facies anterior (sternocostalis). B Posterior surface (base). C Facies inferior (facies diaphragmatica).

Note the reflection of visceral pericardium serosum to become the parietal serous pericardium.

Fig. 15.51 Chambers of the heart

A Ventriculus dexter, anterior view. Note the crista supraventricularis, which marks the adult boundary between the embryonic ventricle and the bulbus cordis (now the conus arteriosus).

B dextrum, right lateral view.

C Atrium sinistrum and ventriculus sinister, left lateral view. Note the irregular trabeculae carneae characteristic of the ventricular wall.

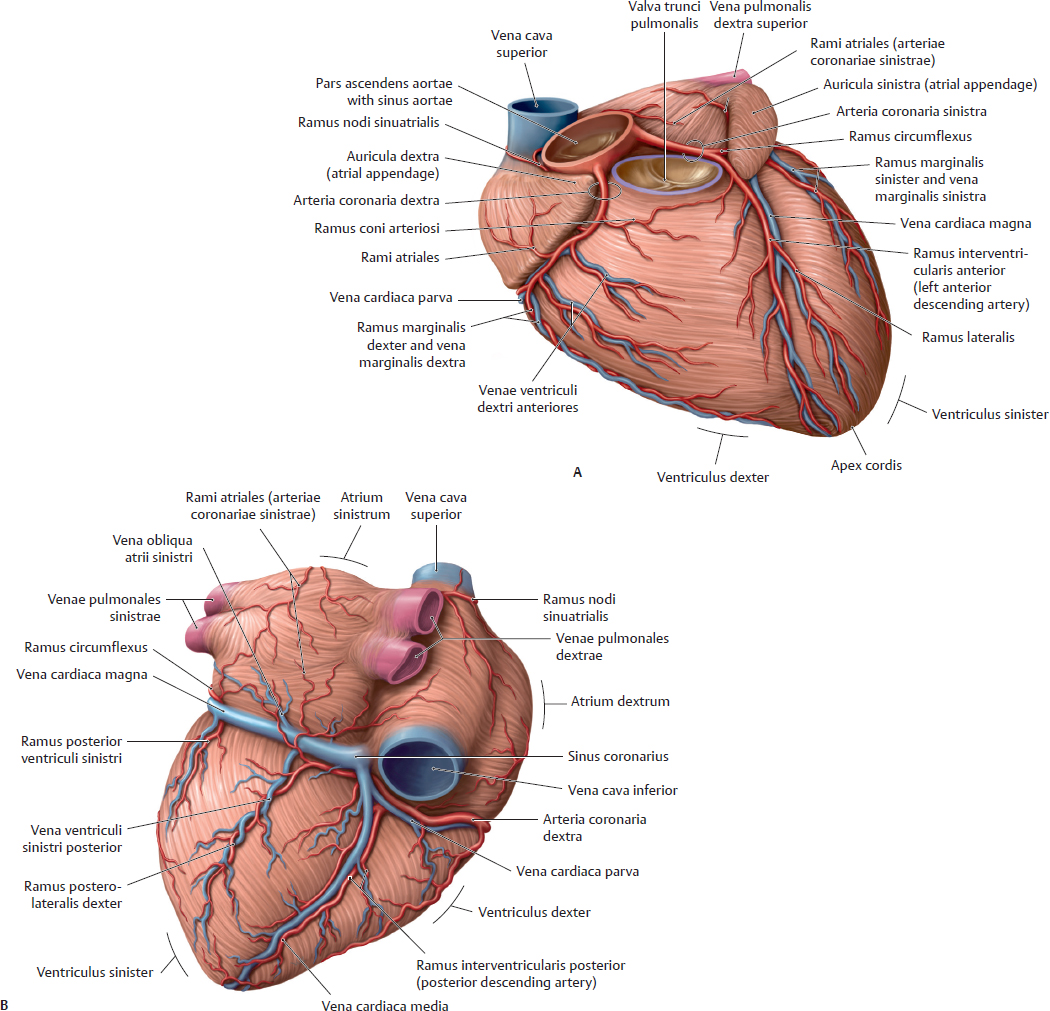

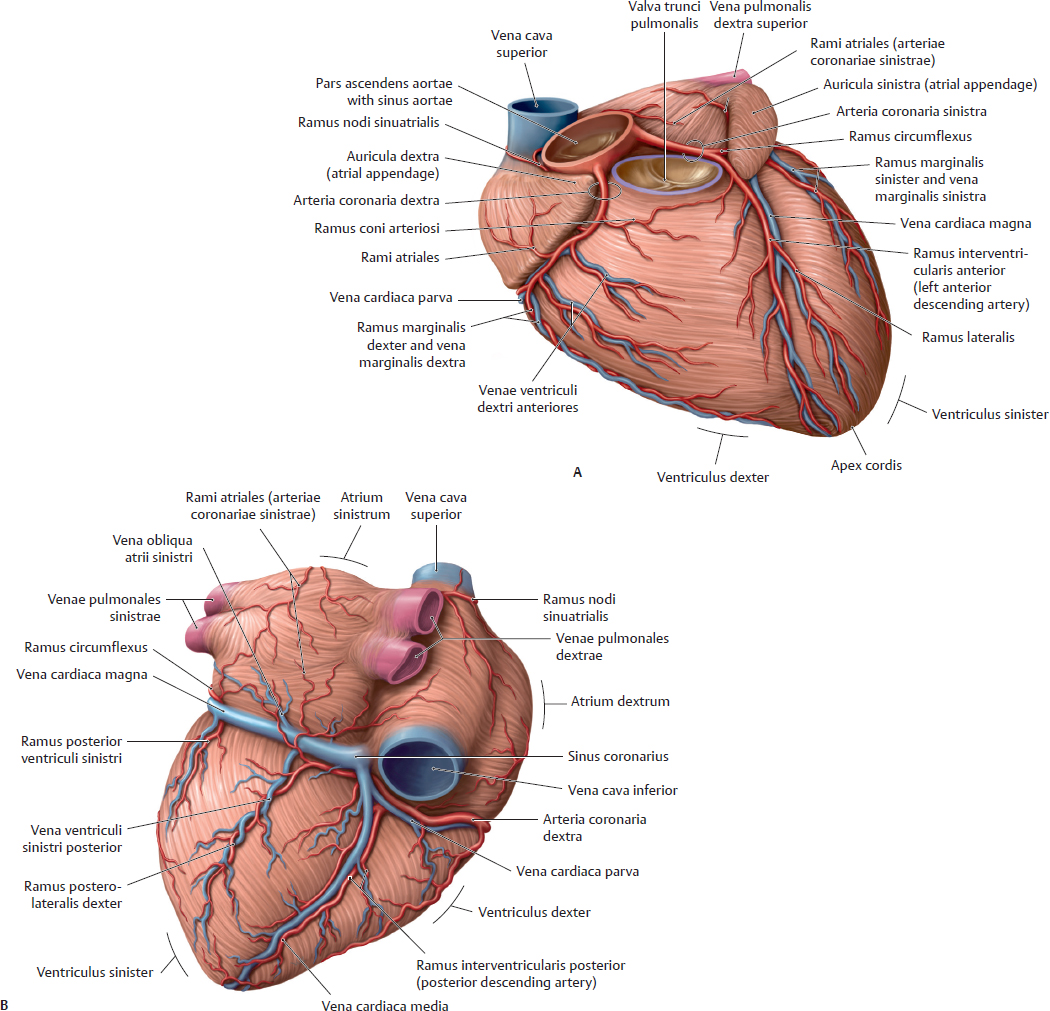

Heart: Valves, Arteries, & Veins

The cardiac valves are divided into two groups: semilunar and atrioventricular. The two Valva semilunaris (valva aortae and valva trunci pulmonalis), located at the base of the two great arteries of the heart, regulate passage of blood from the ventriculi to the aorta and truncus pulmonalis. The two valvae atrioventriculares (sinistra and dextra) lie at the interface between the atria and ventriculi.

Fig. 15.52 Cardiac valves

Plane of cardiac valves, superior view. Removed: Atria and great arteries.

A Ventricular diastole (relaxation of the ventriculi). Closed: Valvae semilunares. Open: Valvae atrioventriculares.

B Ventricular systole (contraction of the ventriculi). Closed: Valvae atrioventriculares. Open: Valvae semilunares.

Fig. 15.53 Arteriae coronariae and venae cordis

A Anterior view.

B Posteroinferior view. Note: The right and sinistra typically anastomose posteriorly at the atrium sinistrum and ventriculus sinister.

Table 15.9 Rami of the arteriae coronariae

Arteria coronaria sinistra |

Arteria coronaria dextra |

Ramus circumflexus

• Rami atriales

• Ramus marginalis sinister

• Ramus posterior ventriculi sinistri |

Ramus nodi sinuatrialis |

Ramus coni arteriosi |

Rami atriales |

Ramus marginalis dexter |

Ramus interventricularis anterior (left anterior descending)

• Ramus coni arteriosi

• Ramus lateralis

• Rami interventriculares septales |

Ramus interventricularis posterior (posterior descending)

• Rami interventriculares septales |

Ramus nodi atrioventricularis |

Ramus posterolateralis dexter |

Table 15.10 Divisions of the venae cordis

Vein |

Tributaries |

Drainage to |

Venae cardiacae anteriores (not shown) |

Atrium dextrum |

Vena cardiaca magna |

Vena interventricularis anterior |

Sinus coronarius |

Vena marginalis sinistra |

Vena obliqua atrii sinistri |

Vena ventriculi sinistri posterior |

Vena cardiaca media (vena interventricularis posterior) |

Vena cardiaca parva |

Venae ventriculi dextri anteriores |

Vena marginalis dextra |

Heart: Conduction & Innervation

Fig. 15.54 Autonomic innervation of the heart

A Schematic. Sympathetic innervation: Preganglionic neurons from T1 to T6 segments of medulla spinalis send fibers to synapse on postganglionic neurons in the ganglia cervicalia and upper ganglia thoracica. The three nervi cardiaci cervicales and their rami cardiaci thoracici contribute to the plexus cardiacus. Parasympathetic innervation: Preganglionic neurons and fibers reach the heart via cardiac branches, some of which also arise in the cervical region. They synapse on postganglionic neurons near the nodus sinuatrialis and along the arteriae coronariae.

B Autonomic plexuses of the heart, right lateral view. Note the continuity between the plexus cardiacus, aortici, and pulmonalis.

C Autonomic nerves of the heart. Anterior view of opened thorax.

Fig. 15.55 Systema conducens cordis

A Anterior view. Opened: All four chambers.

B Right lateral view. Opened: Atrium dextrum and ventriculus dexter.

C Left lateral view. Opened: Atrium sinistrum and ventriculus sinister. Contraction of cardiac muscle is modulated by the systema conducens cordis. This system of specialized myocardial cells (rami subendocardiales; Purkinje fibers) generates and conducts excitatory impulses in the heart. The conduction system contains two nodes, both located in the atria: the nodus sinuatrialis (SA), known as the pacemaker, and the nodus atrioventricularis (AV).

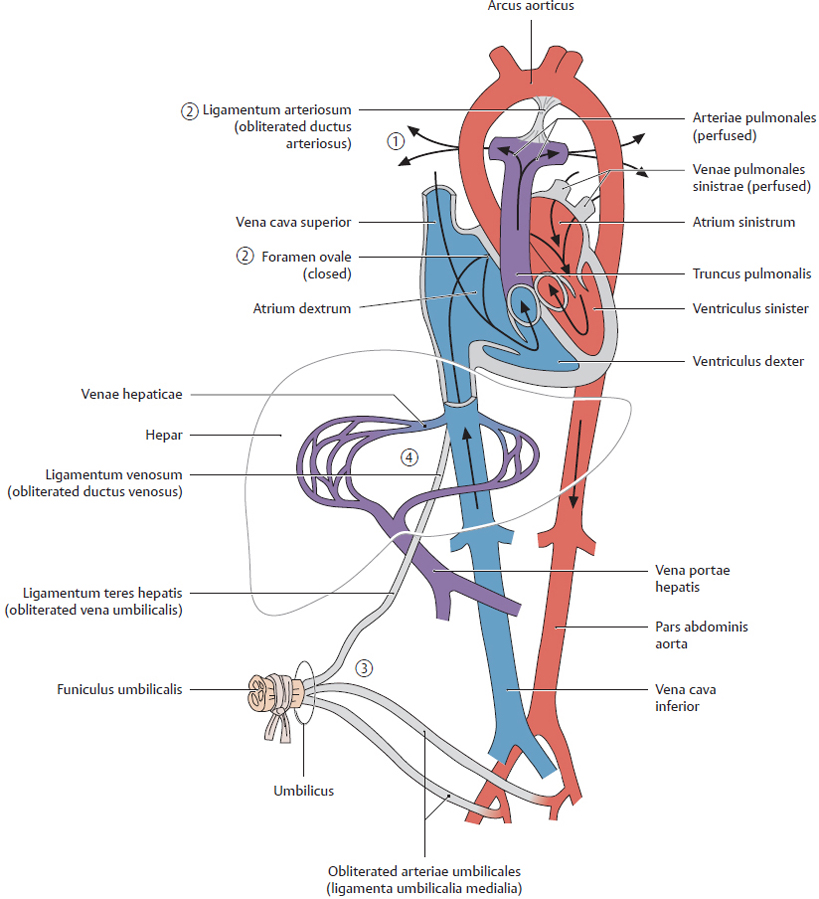

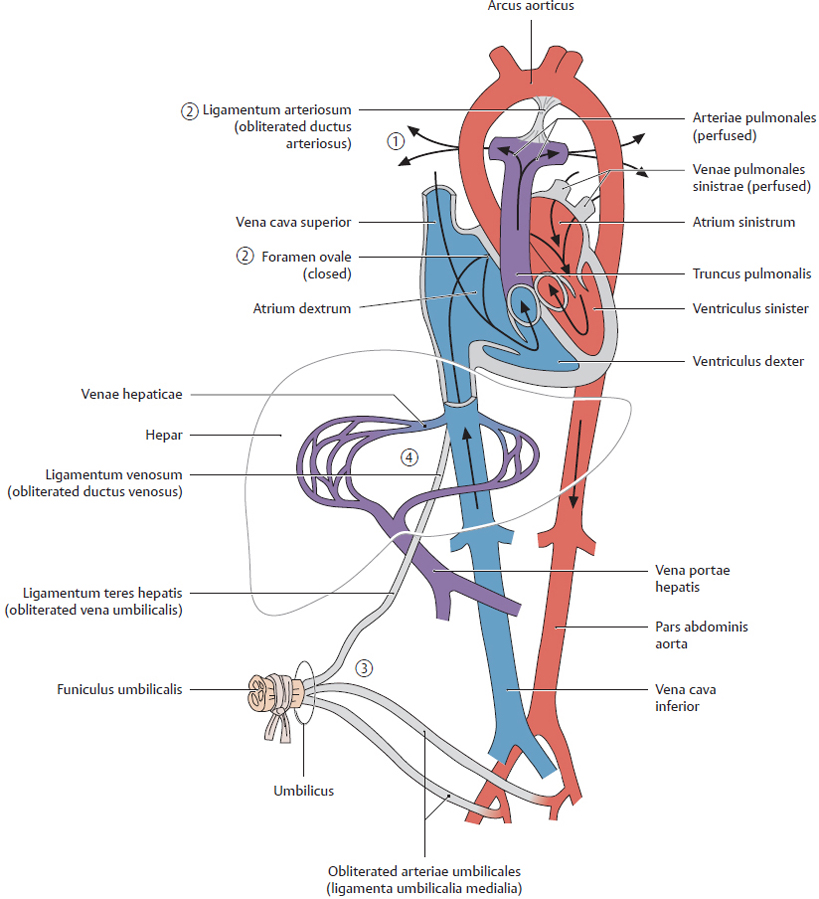

Pre- & Postnatal Circulation

Fig. 15.56 Prenatal circulation (after Fritsch and Kühnel)

Oxygenated and nutrient-rich fetal blood from the placenta passes to the fetus via the vena umbilicalis.

Oxygenated and nutrient-rich fetal blood from the placenta passes to the fetus via the vena umbilicalis.

Approximately half of this blood bypasses the liver (via the ductus venosus) and enters the vena cava inferior. The remainder enters the vena portae hepatis to supply the liver with nutrients and oxygen.

Approximately half of this blood bypasses the liver (via the ductus venosus) and enters the vena cava inferior. The remainder enters the vena portae hepatis to supply the liver with nutrients and oxygen.

Blood entering the atrium dextrum from the vena cava inferior bypasses the ventriculus dexter (as the lungs are not yet functioning) to enter the atrium sinistrum via the foramen ovale, a right-to-left shunt.

Blood entering the atrium dextrum from the vena cava inferior bypasses the ventriculus dexter (as the lungs are not yet functioning) to enter the atrium sinistrum via the foramen ovale, a right-to-left shunt.

Blood from the vena cava superior enters the atrium dextrum, passes to the ventriculus dexter, and moves into the truncus pulmonalis. Most of this blood enters the aorta via the ductus arteriosus, a right-to-left shunt.

Blood from the vena cava superior enters the atrium dextrum, passes to the ventriculus dexter, and moves into the truncus pulmonalis. Most of this blood enters the aorta via the ductus arteriosus, a right-to-left shunt.

The partially oxygenated blood in the aorta returns to the placenta via the paired arteriae umbilicales that arise from the arteriae iliacae internae.

The partially oxygenated blood in the aorta returns to the placenta via the paired arteriae umbilicales that arise from the arteriae iliacae internae.

Fig. 15.57 Postnatal circulation (after Fritsch and Kühnel)

As pulmonary respiration begins at birth, pulmonary blood pressure falls, causing blood from the truncus pulmonalis to enter the arteriae pulmonales.

As pulmonary respiration begins at birth, pulmonary blood pressure falls, causing blood from the truncus pulmonalis to enter the arteriae pulmonales.

The foramen ovale and ductus arteriosus close, eliminating the fetal right-to-left shunts. The pulmonary and systemic circulations in the heart are now separate.

The foramen ovale and ductus arteriosus close, eliminating the fetal right-to-left shunts. The pulmonary and systemic circulations in the heart are now separate.

As the infant is separated from the placenta, the arteriae umbilicales occlude (except for the proximal portions), along with the vena umbilicalis and ductus venosus.

As the infant is separated from the placenta, the arteriae umbilicales occlude (except for the proximal portions), along with the vena umbilicalis and ductus venosus.

Blood to be metabolized now passes through the liver.

Blood to be metabolized now passes through the liver.

Fig. 15.58 Circulation

Oxygenated blood is shown in red; deoxygenated blood in blue. See Fig 15.56 for prenatal circulation.

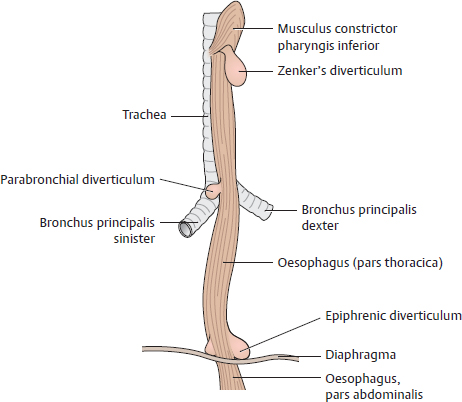

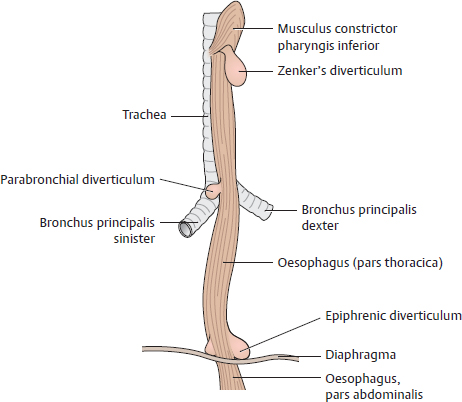

Oesophagus

The oesophagus is divided into three parts: pars cervicalis (C6–T1), pars thoracica (T1 to the hiatus oesophageus of the diaphragma), and abdominal (the diaphragma to the cardiac orifice of the stomach). It descends slightly to the right of the pars thoracica aortae and pierces the diaphragma slightly to the left, just below the processus xiphoideus of the sternum.

Fig. 15.59 Esophagus: Location and constrictions

A Projection of esophagus onto chest wall. Esophageal constrictions are indicated with arrows.

B Esophageal constrictions, right lateral view.

Fig. 15.60 Oesophagus in situ

Anterior view.

Fig. 15.61 Structure of the oesophagus

A Esophageal wall, oblique left posterior view.

B Esophagogastric junction, anterior view. A true sphincter is not identifiable at this junction; instead, the diaphragmatic muscle of the hiatus oesophageus functions as a sphincter. It is often referred to as the “Z line” because of its zigzag form.

C Functional architecture of esophageal muscle.

Fig. 15.62 Esophageal diverticula

Diverticula (abnormal outpouchings or sacs) generally develop at weak spots in the esophageal wall. There are three main types of esophageal diverticula:

— Hypopharyngeal (pharyngo-esophageal) diverticula: outpouchings occurring at the junction of the pharynx and the oesophagus. These include Zenker’s diverticula (70% of cases).

— “True” traction diverticula: protrusion of all wall layers, not typically occurring at characteristic weak spots. However, they generally result from an inflammatory process (e.g., lymphangitis) and are thus common at sites where the oesophagus closely approaches the bronchi and bronchial lymph nodes (thoracic or parabronchial diverticula).

— “False” pulsion diverticula: herniations of the tunica mucosa and tela submucosa through weak spots in the tunica muscularis due to a rise in esophageal pressure (e.g., during normal swallowing). These include parahiatal and epiphrenic diverticula occurring above the hiatus oesophageus of the diaphragma (10% of cases).

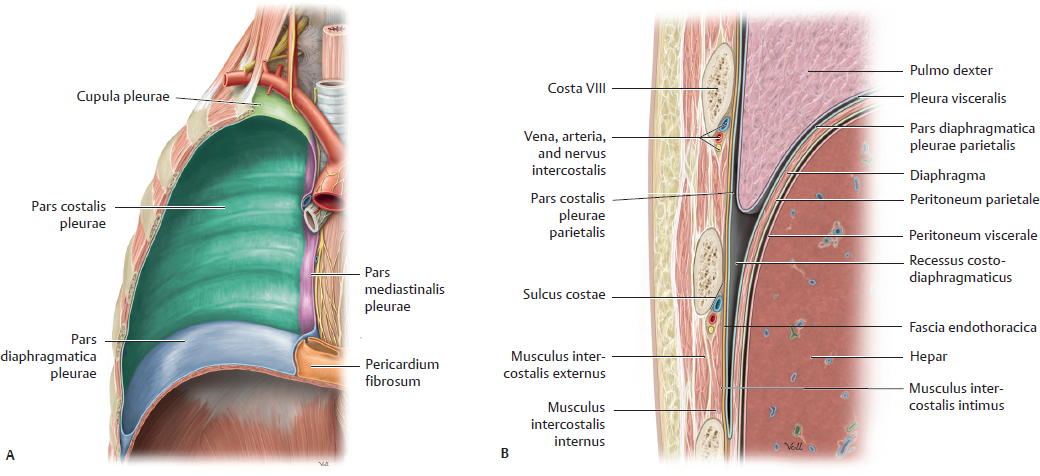

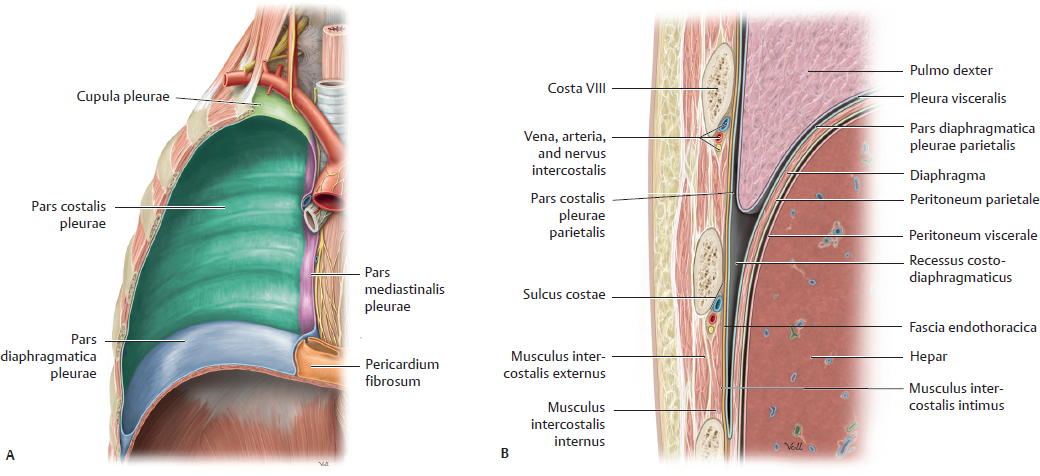

Pleura

Fig. 15.63 Vertical reference lines of the thorax

A Anterior view. B Right lateral view.

Fig. 15.64 Pleura parietalis

A Parts of the pleura parietalis. Opened: Right cavitas pleuralis, anterior view.

B Recessus costodiaphragmaticus, coronal section, anterior view. Reflection of the pars diaphragmatica pleurae onto the inner thoracic wall (becoming the pars costalis pleurae) forms the recessus costodiaphragmaticus.

The cavitas pleuralis is bounded by two serous layers. The pleura visceralis (pulmonalis) covers the lungs, and the pleura parietalis lines the inner surface of the cavitas thoracica. The four parts of the pleura parietalis (pars costalis, pars diaphragmatica, pars mediastinalis, and cupula) are continuous.

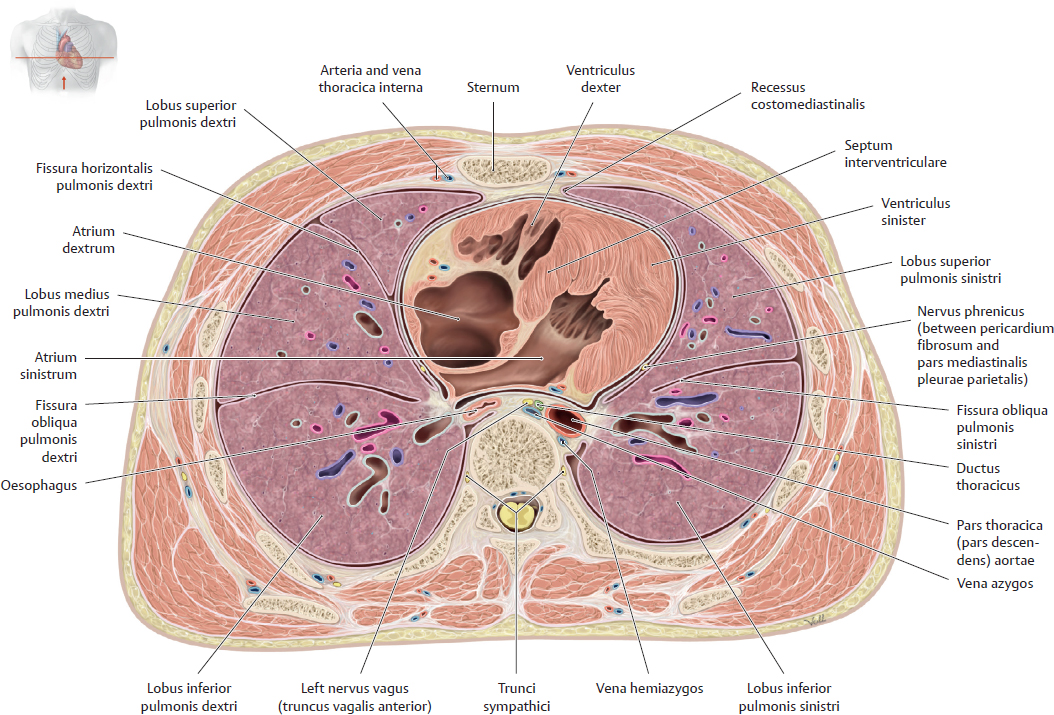

Fig. 15.65 Thorax in transverse section

Transverse section through T8, inferior view.

Lungs in situ

Fig. 15.66 Lungs in situ

The pulmones sinister and dexter occupy the full volume of the cavitas pleuralis. Note that the pulmo sinister is slightly smaller than the pulmo dexter due to the asymmetrical position of the heart.

A Topographical relations of the lungs, transverse section, inferior view.

B Anterior view with lungs retracted.

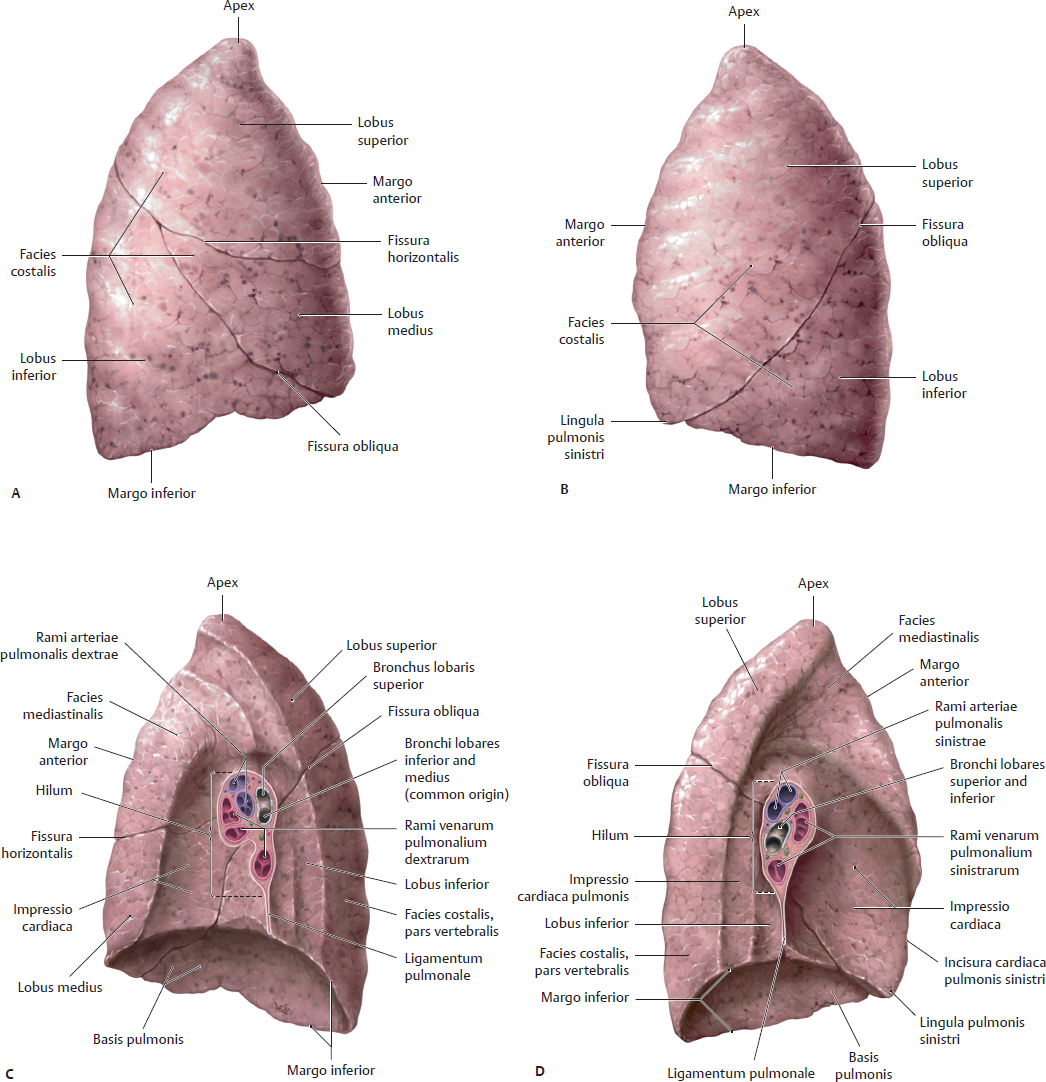

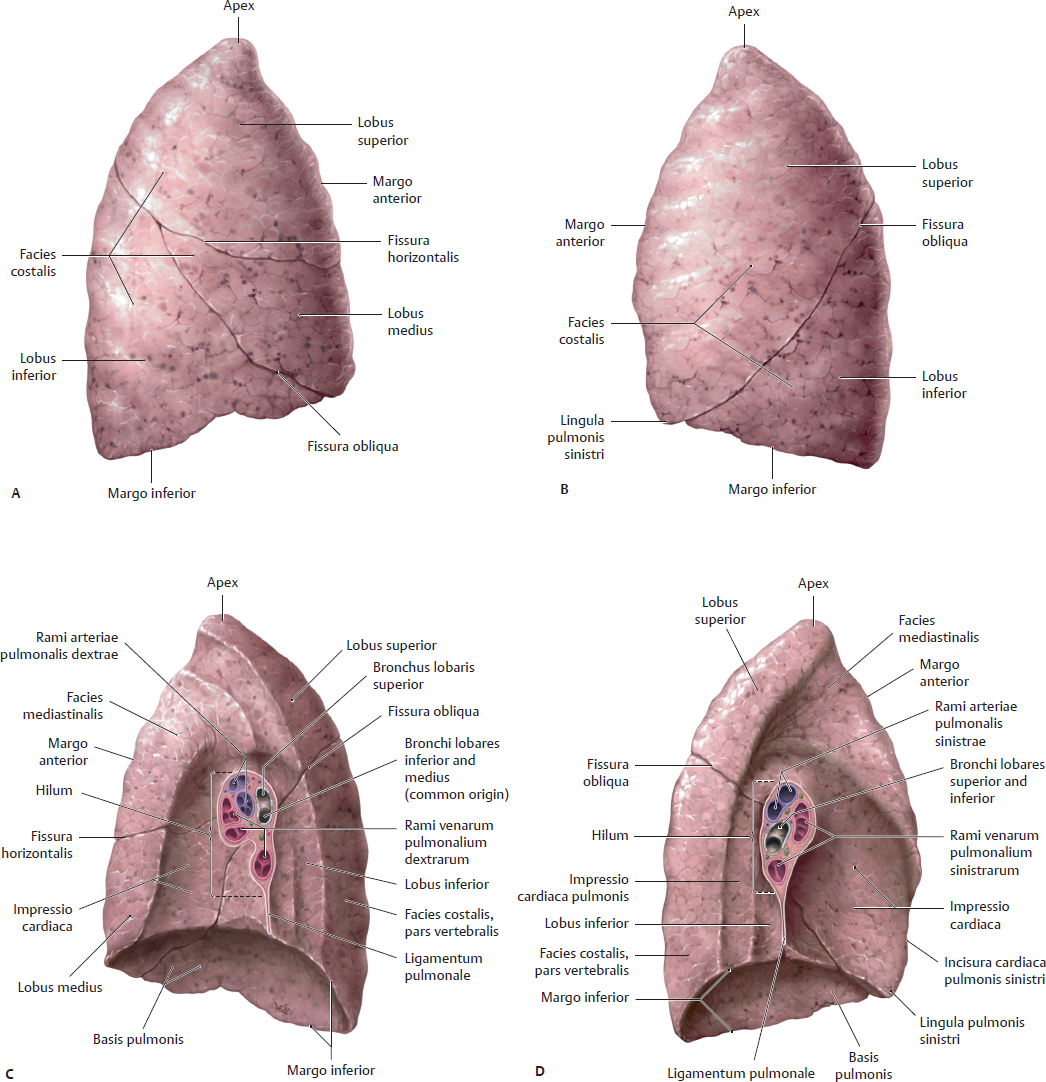

Fig. 15.67 Gross anatomy of the lungs

A Pulmo dexter, lateral view. B Pulmo sinister, lateral view.

C Pulmo dexter, medial view. D Pulmo sinister, medial view.

The fissurae obliqua and horizontalis divide the pulmo dexter into three lobi: superior, medius, and inferior. The fissura obliqua divides the pulmo sinister into two lobi: superior and inferior. The apex of each lung extends into the root of the neck. The hilum is the location at which the bronchi and neurovascular structures connect to the lung.

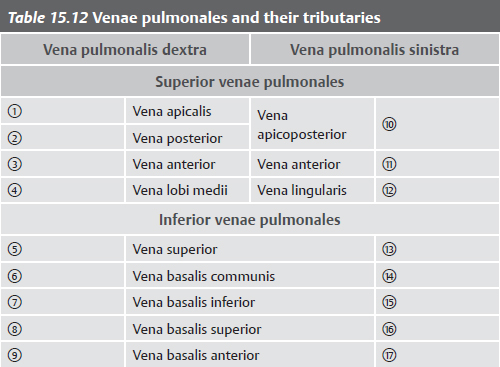

Pulmonary Arteries & Veins

Fig. 15.68 Arteriae and venae pulmonales

Anterior view. The truncus pulmonalis arises from the ventriculus dexter and divides into an arteria pulmonalis sinistra and dexter. The paired venae pulmonales open into the atrium sinistrum on each side. The arteriae pulmonales accompany and follow the branching of the bronchial tree (arbor bronchialis), whereas the venae pulmonales do not, being located at the margins of the lobuli pulmonales.

Fig. 15.69 Arteriae pulmonales

Schematic.

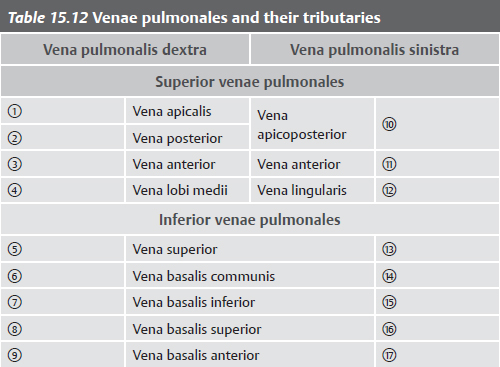

Fig. 15.70 Venae pulmonales

Schematic.

Fig. 15.71 Autonomic innervation of the tracheobronchial tree

Sympathetic innervation (red); parasympathetic innervation (blue).

Surface Anatomy & Muscles of the Abdominal Wall

Fig. 15.72 Muscles of the posterior abdominal wall

Coronal section with diaphragm in intermediate position.

Table 15.13 Transverse planes through the abdomen

Planum transpyloricum Planum transpyloricum

|

Transverse plane midway between the superior borders of the symphysis pubica and the manubrium sterni |

Planum subcostalis Planum subcostalis

|

Plane at the lowest level of the costal margin (the inferior margin of the cartilago costalis X) |

Planum supracrestale Planum supracrestale

|

Plane passing through the summits of the cristae iliacae |

Planum transtuberculare Planum transtuberculare

|

Plane at the level of the tubercula iliaca (the tuberculum iliacum lies ~5 cm posterolateral to the spina iliaca anterior superior) |

Planum interspinale Planum interspinale

|

Plane at the level of the spina iliaca anterior superior |

Fig. 15.73 Plana transversalia through the abdomen

Anterior view. See Table 15.13.

Fig. 15.74 Muscles of the abdominal wall

Right side, anterior view.

A Superficial abdominal wall muscles.

B Removed: Musculi obliquus externus abdominis, pectoralis major, and serratus anterior.

Fig. 15.75 Anterior abdominal wall and vagina musculi recti abdominis

Transverse section, superior to the linea arcuata.

The vagina musculi recti abdominis is created by fusion of the aponeuroses of the musculi transversus abdominis and obliqui abdominis. The inferior edge of the lamina posterior of the vagina musculi recti abdominis is called the linea arcuata.

Arteries of the Abdominal Wall & Abdomen

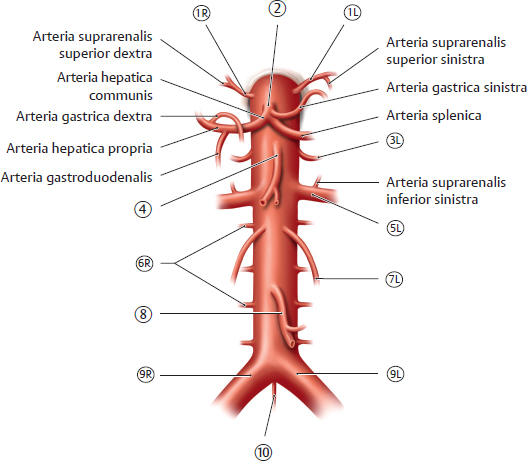

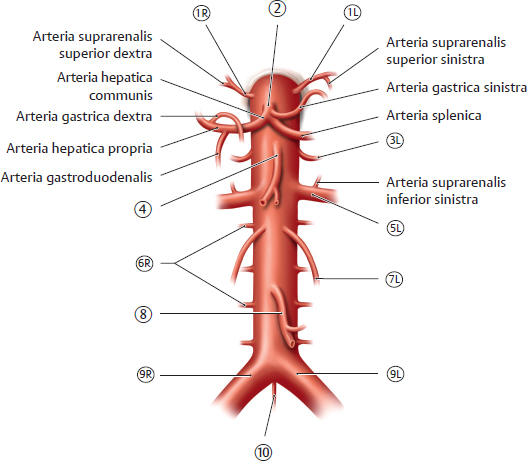

Fig. 15.76 Pars abdominalis aortae and major branches

Anterior view. The pars abdominalis aortae enters the abdomen at the T12 level through the hiatus aorticus of the diaphragm. Before bifurcating at L4 into its terminal branches, the arteriae iliacae communes, the aorta abdominalis gives off the arteriae renales and three major trunks that supply the organs of the alimentary canal:

Truncus coeliacus: supplies the structures of the foregut, the anterior portion of the alimentary canal. The foregut consists of the oesophagus (abdominal 1.25 cm), stomach (gaster), duodenum (proximal half), liver (hepar), gallbladder (vesica biliaris), and pancreas (superior portion).

Arteria mesenterica superior: supplies the structures of the midgut: the duodenum (distal half), jejunum and ileum, caecum and appendix, colon ascendens, flexura coli dextra, and the proximal one half of the colon transversum.

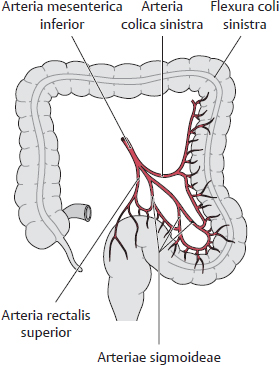

Arteria mesenterica inferior: supplies the structures of the hindgut: the colon transversum (distal half), flexura coli sinistra, cola descendens and sigmoideum, rectum, and canalis analis (upper part).

Fig. 15.77 Arteries of the abdominal wall

The arteriae epigastricae superior and inferior form a potential anastomosis, or bypass for blood, from the arteriae subclavia and femoralis. This effectively allows blood to bypass the aorta abdominalis.

Fig. 15.78 Branches of the aorta abdominalis

Anterior view. See Table 15.14.

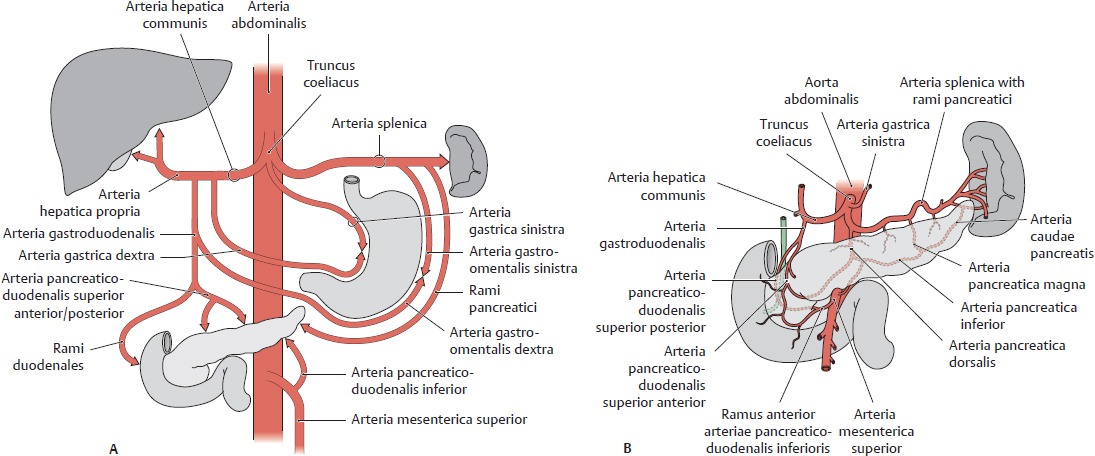

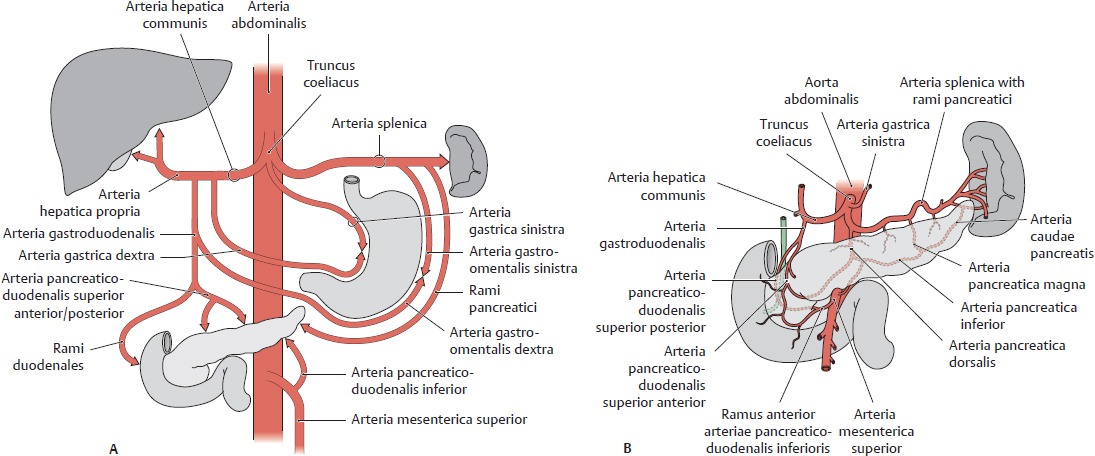

Fig. 15.79 Truncus coeliacus

A Truncus coeliacus distribution. B Arterial supply to the pancreas.

Fig. 15.80 Abdominal arterial anastomoses

The three major anastomoses provide overlap in the arterial supply to abdominal areas to ensure adequate blood flow. These are between

the truncus coeliacus and the arteria mesenterica superior via the arteriae pancreaticoduodenales,

the truncus coeliacus and the arteria mesenterica superior via the arteriae pancreaticoduodenales,

the arteriae mesentericae superior and inferior via the arteriae colicae media and sinistra, and

the arteriae mesentericae superior and inferior via the arteriae colicae media and sinistra, and

the arteriae mesenterica inferior and the iliaca interna via the arteriae rectales superior and media or inferior.

the arteriae mesenterica inferior and the iliaca interna via the arteriae rectales superior and media or inferior.

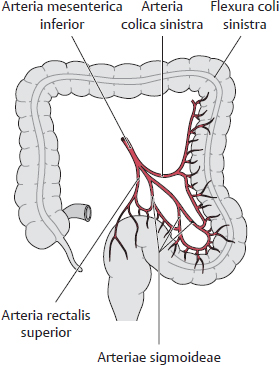

Fig. 15.81 Arteria mesenterica superior

Fig. 15.82 Arteria mesenterica inferior

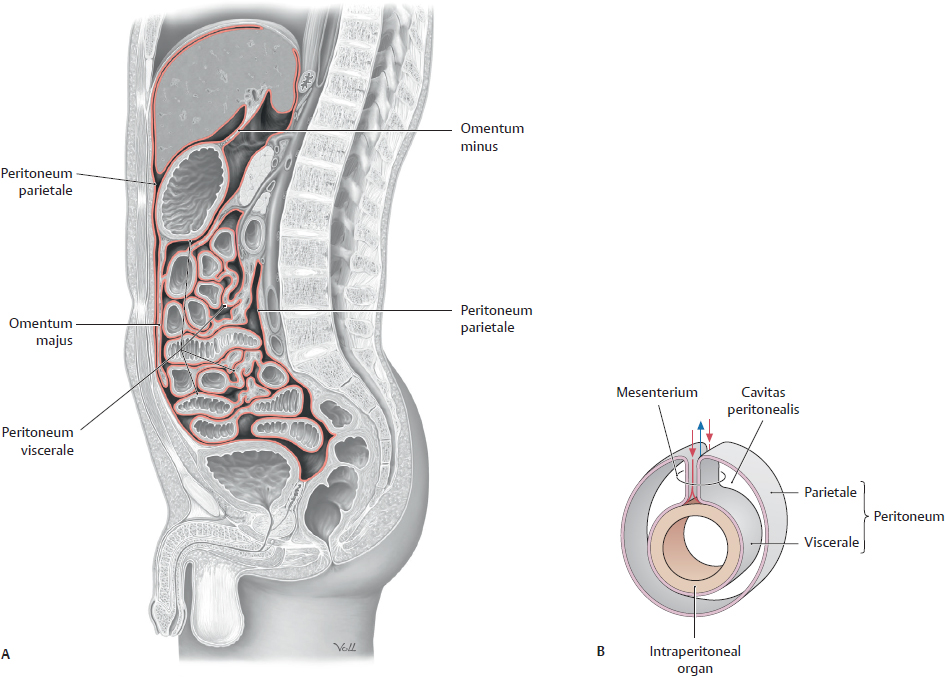

Divisions of the Cavitas Abdominis & Pelvis

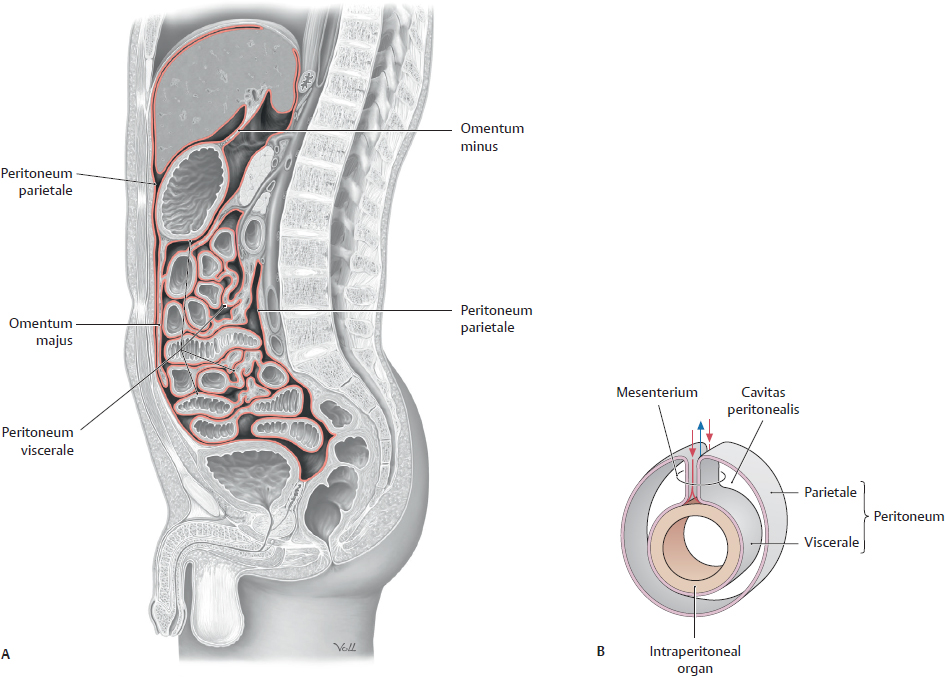

Organs in the cavitas abdominis et pelvis are classified by the presence of surrounding peritoneum (the serous membrane lining the cavity) and a mesenterium (a double layer of peritoneum that connects the organ to the abdominal wall) (see Table 15.15).

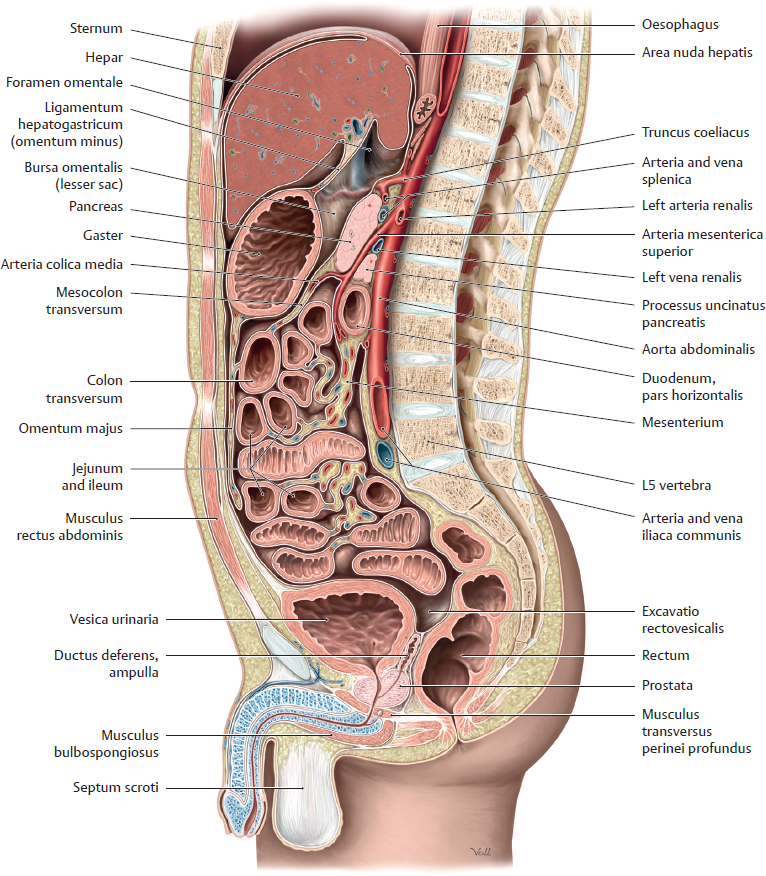

Fig. 15.83 Cavitas peritonealis

A Midsagittal section through the male cavitas abdominis et pelvis, viewed from the left. The peritoneum is shown in red.

B An intraperitoneal organ, showing the mesenterium and surrounding peritoneum. Arrows indicate location of blood vessels in the mesenterium.

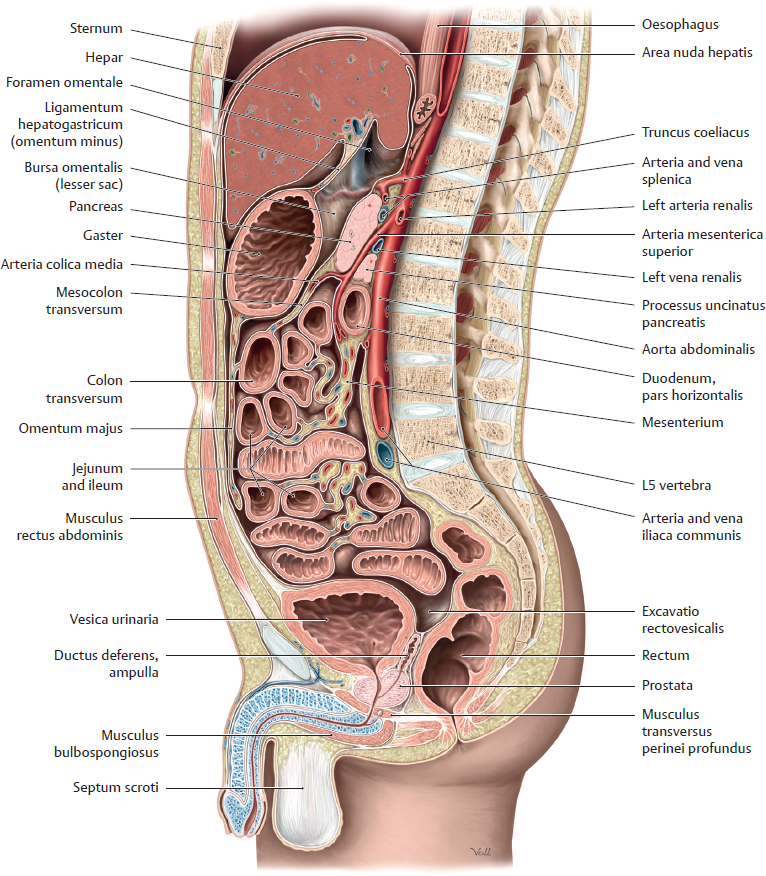

Fig. 15.84 Peritoneal relationships of the abdominopelvic organs

Midsagittal section through the male cavitas abdominis et pelvis, viewed from the left.

Cavitas Peritonealis & Mesenteria (I)

The cavitas peritonealis is divided into the large greater sac and small bursa omentalis (lesser sac). The omentum majus is an apron-like fold of peritoneum suspended from the curvatura major gastri and covering the anterior surface of the colon transversum. The attachment of the mesocolon transversum on the anterior surface of the pars descendens duodeni and the pancreas divides the cavitas peritonealis into a supracolic compartment (hepar, vesica biliaris, and gaster) and an infracolic compartment (intestines).

Fig. 15.85 Dissection of the peritoneal cavity Anterior view.

A Greater sac. Retracted: Abdominal wall.

B Infracolic compartment, the portion of the cavitas peritonealis below the attachment of the mesocolon transversum. Retracted: Omentum majus and colon transversum.

C Mesenteria and mesenteric recesses in the infracolic compartment. Retracted: Omentum majus, colon transversum, intestina tenua, and colon sigmoideum.

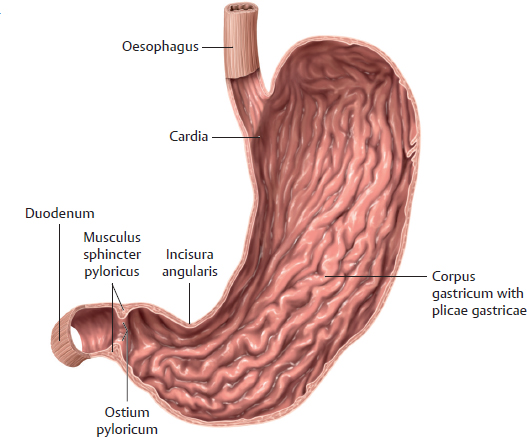

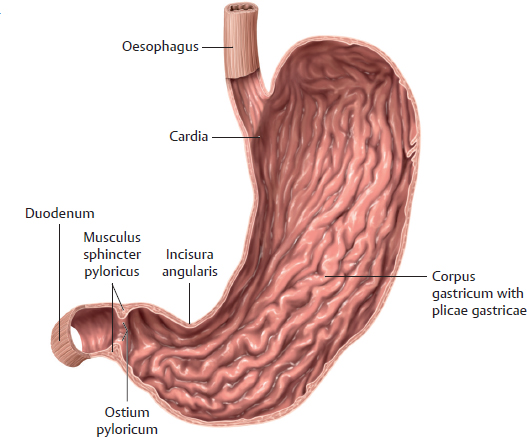

Gaster & Bursa Omentalis

Fig. 15.86 Gaster in situ

Anterior view of the opened upper abdomen. Arrow indicates the foramen omentale.

Fig. 15.87 Gaster

Anterior view. Removed: Anterior wall.

Fig. 15.88 Bursa omentalis

Anterior view. Divided: Ligamentum gastrocolicum.

Retracted: Hepar. Reflected: Gaster.

Mesenteria (II) & Intestinum

Fig. 15.89 Mesenteries and organs of the cavitas peritonealis

Anterior view. Divided: Gaster, jejunum, and ileum.

Retracted: Hepar.

Fig. 15.90 Duodenum

Anterior view with the anterior wall opened. The intestinum tenue consists of the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. The duodenum is primarily retroperitoneal and is divided into four partes: superior, descendens, horizontalis, and ascendens.

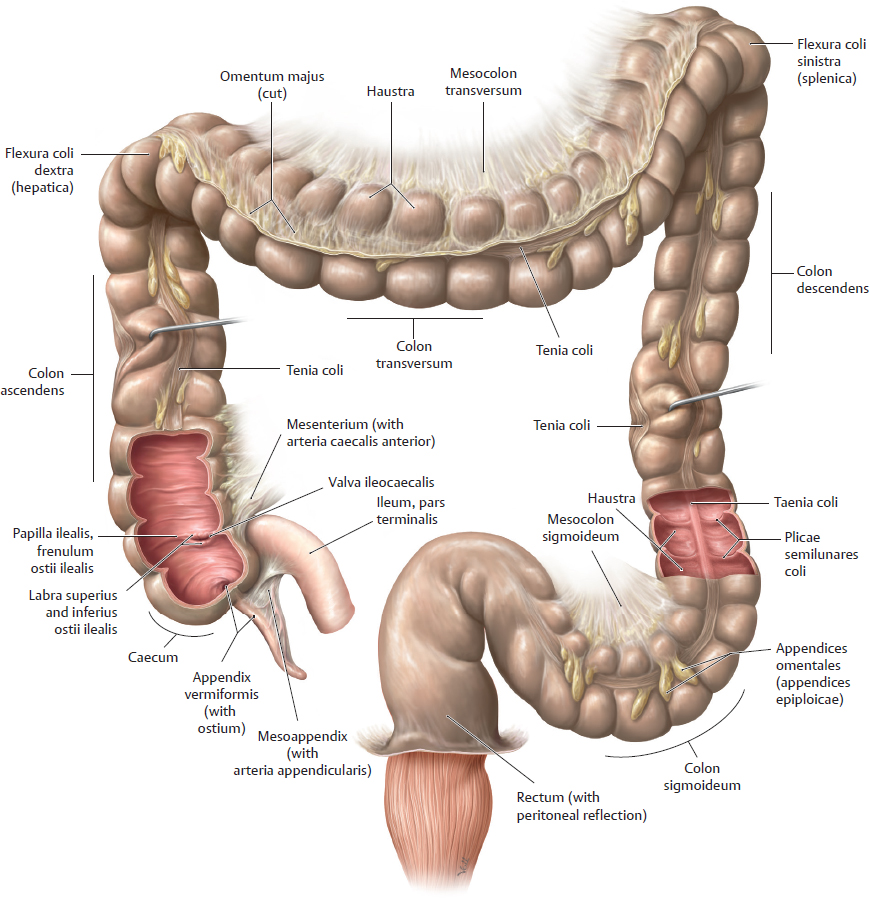

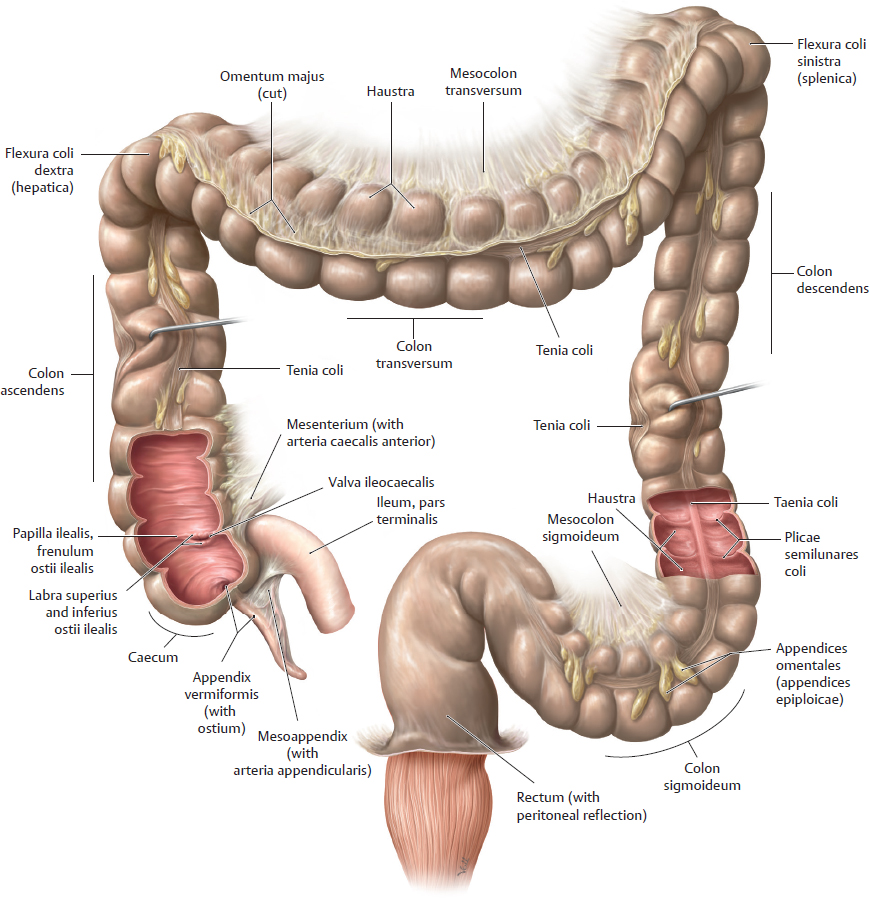

Fig. 15.91 Intestinum crassum

Anterior view.

The cola ascendens and descendens are normally secondarily retroperitoneal, but sometimes they are suspended by a short mesenterium from the posterior abdominal wall. Note: In the clinical setting, the flexura coli sinistra is often referred to as the flexura coli splenica and the flexura coli dextra, as the flexura hepatica.

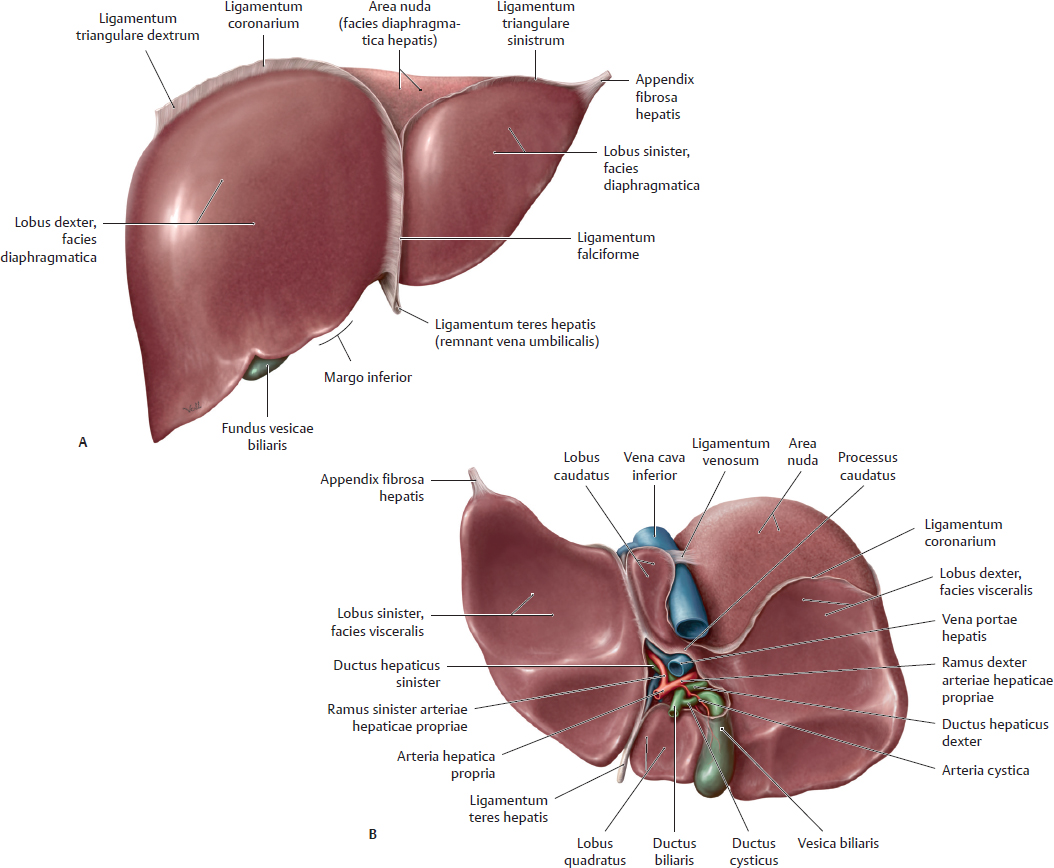

Hepar, Vesica Biliaris, & Biliary Tract

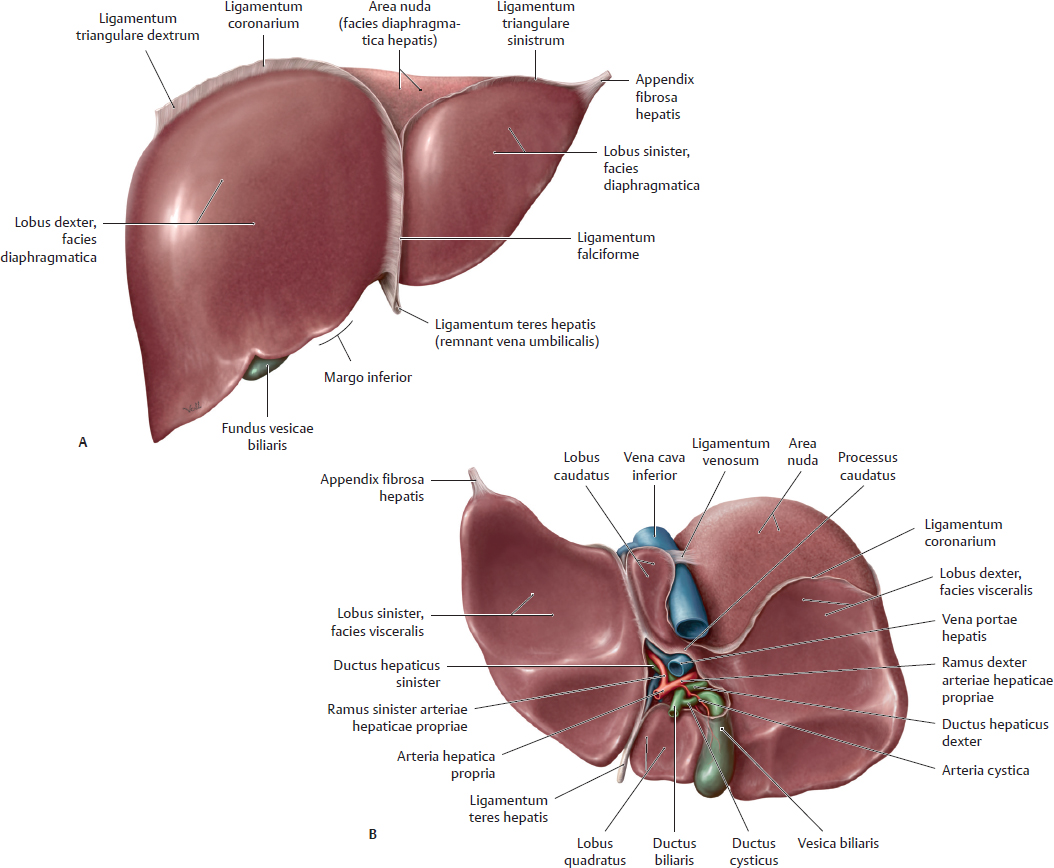

Fig. 15.92 Surfaces of the hepar

A Anterior view. B Inferior view.

The hepar is divided into four lobes by its ligaments: lobi dexter, sinister, caudatus, and quadratus. The ligamentum falciforme, a double layer of pertioneum parietale that reflects off the anterior abdominal wall and extends to the liver, spreading out over its surface as peritoneum viscerale, divides the liver into (anatomic) lobi dexter and sinister. The ligamentum teres hepatis is found in the free edge of the ligamentum falciforme and contains the obliterated vena umbilicalis, which once extended from the umbilicus to the hepar.

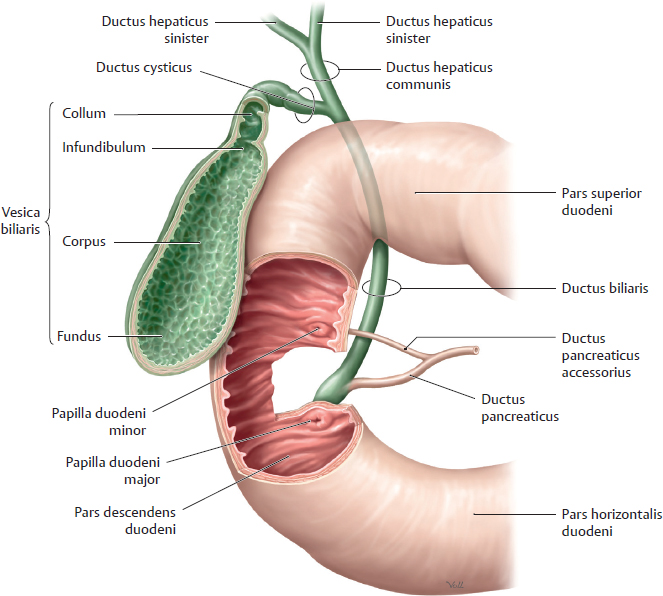

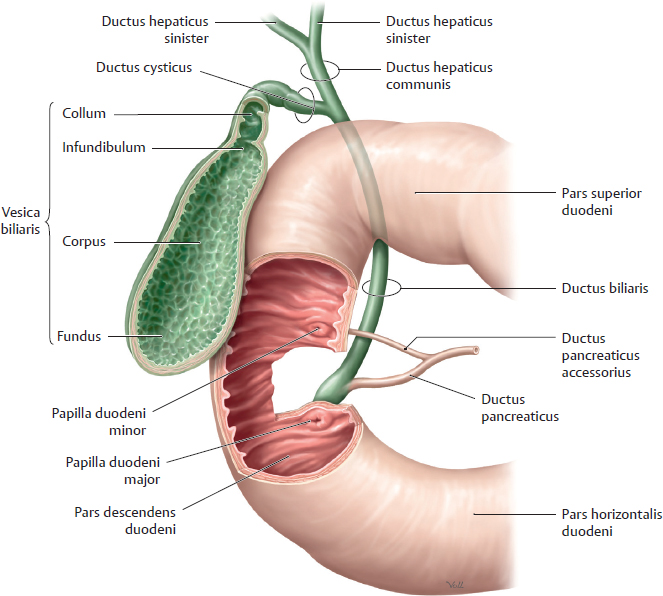

Fig. 15.93 Biliary sphincter system

A Musculi sphinctri of the ductus pancreaticus and biliaris. B Sphincter system in the duodenal wall.

Fig. 15.94 Extrahepatic bile ducts

Anterior view. Opened: Vesica biliaris and duodenum.

Fig. 15.95 Biliary tract in situ

Anterior view. Removed: Gaster, intestinum tenue, colon transversum, and large portions of the hepar. The vescia biliaris is intraperitoneal and covered by peritoneum viscerale where it is not attached to the hepar.

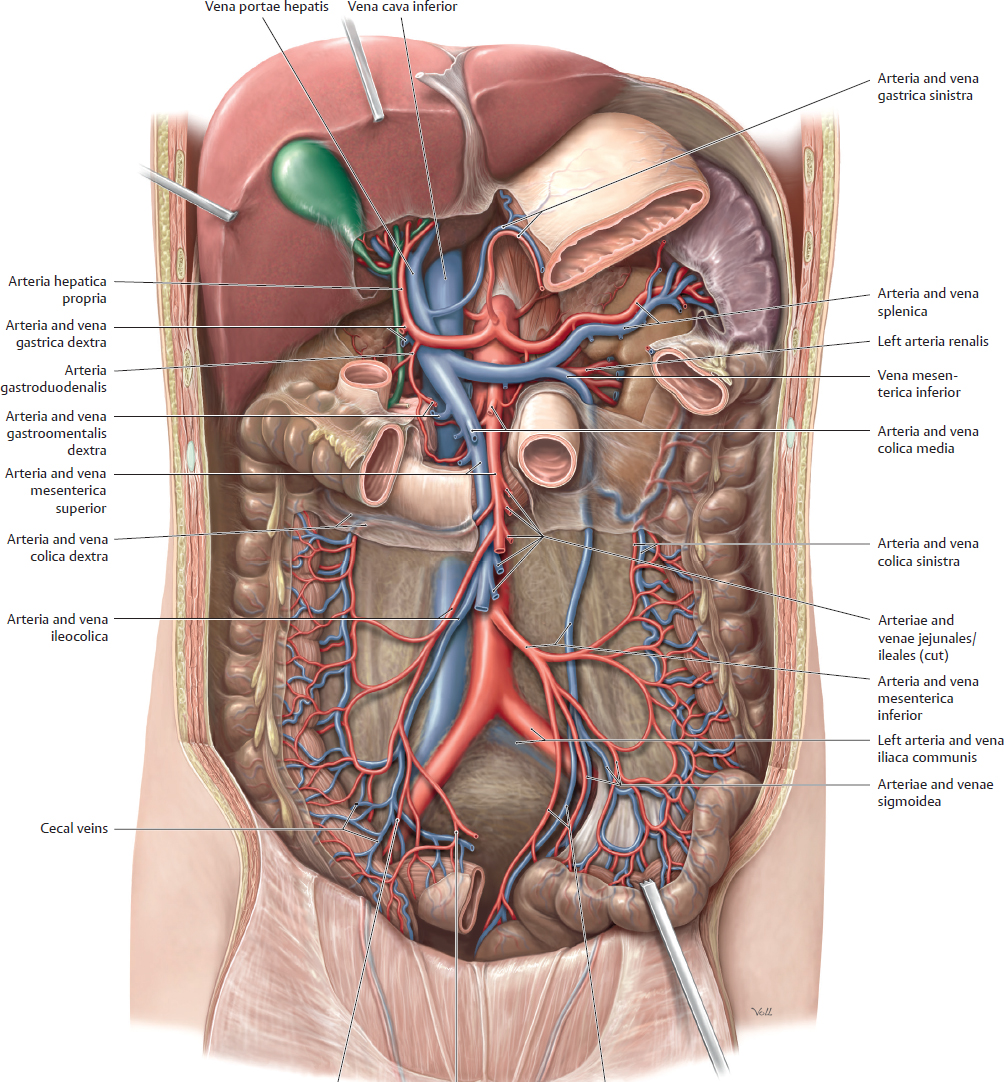

Aorta Abdominalis & Truncus Coeliacus

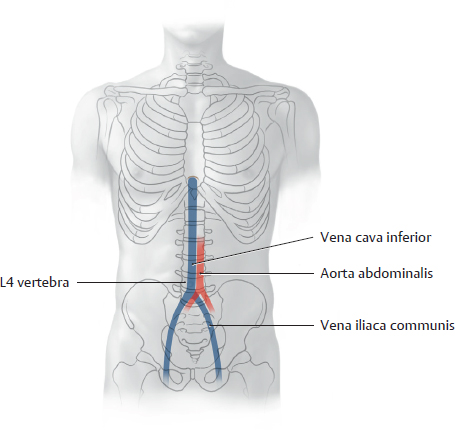

Fig. 15.96 Abdominal aorta

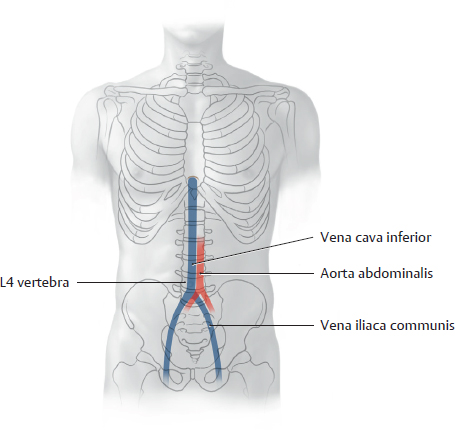

Anterior view of the female abdomen. Removed: All organs except the left ren and glandula suprarenalis. The aorta abdominalis is the distal continuation of the aorta thoracica (see Fig. 15.43, p. 414). It enters the abdomen at the T12 level and bifurcates into the arteriae iliacae communes at L4.

Fig. 15.97 Truncus coeliacus: Gaster, hepar, and vesica biliaris

Anterior view. Opened: Omentum minus. Incised: Omentum majus. The truncus coeliacus arises from the aorta abdominalis at about the level of T12.

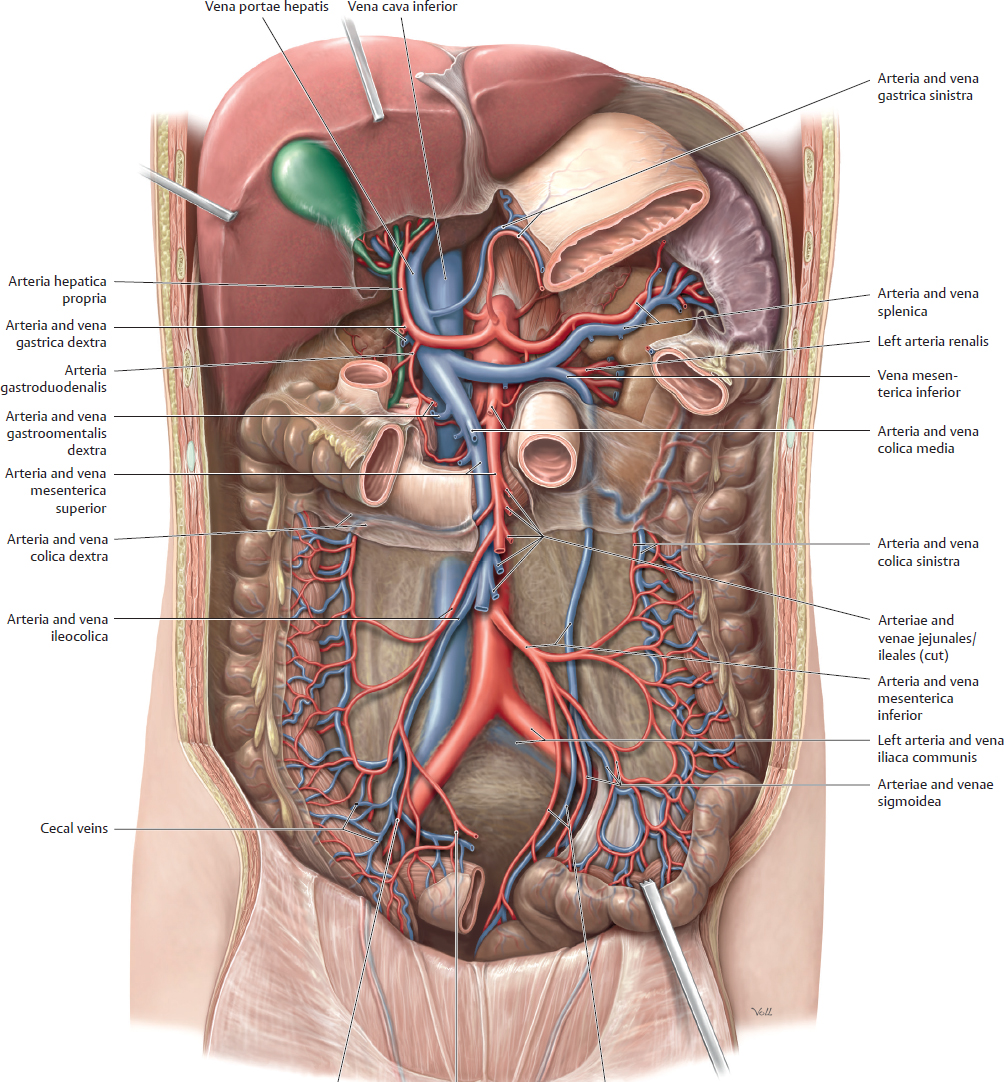

Arteriae Mesentericae Superior & Inferior

Fig. 15.98 Arteria mesenterica superior

Anterior view. Partially removed: Gaster, duodenum, and peritoneum. Reflected: Hepar and vesica biliaris. Note: The arteria colica media has been truncated (see Fig. 15.99). The arteriae mesentericae superior and inferior arise from the aorta opposite L2 and L3, respectively.

Fig. 15.99 Arteria mesenterica inferior

Anterior view. Removed: Jejunum and ileum. Reflected: Colon transversum.

Veins of the Abdomen

Fig. 15.100 Location of the vena cava inferior

Anterior view.

Fig. 15.101 Tributaries of the vena cava inferior

Schematic. See Table 15.16.

Fig. 15.102 Tributaries of the venae renales

Anterior view.

Table 15.16 Tributaries of the vena cava inferior

|

|

Venae phrenicae inferiores (paired) |

|

Venae hepaticae (3) |

|

|

Venae suprarenales (the vena dextra is a direct tributary) |

|

|

Venae renales (paired) |

|

|

Venae testiculares/ovaricae (the vena dextra is a direct tributary) |

|

|

Vena lumbales ascendentes (paired), not direct tributaries |

|

|

Venae lumbales |

|

|

Venae iliacae communes (paired) |

|

Vena sacralis mediana |

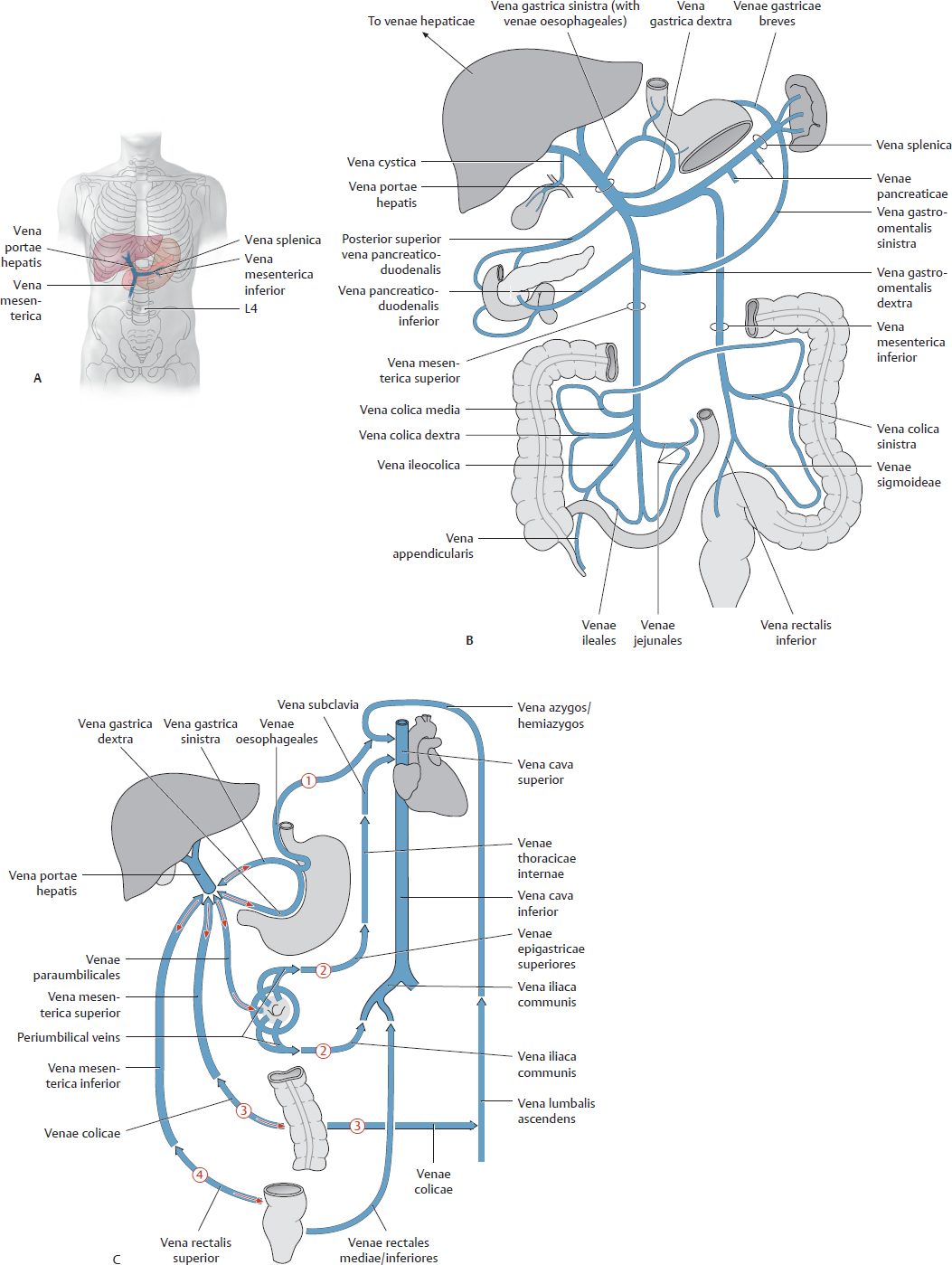

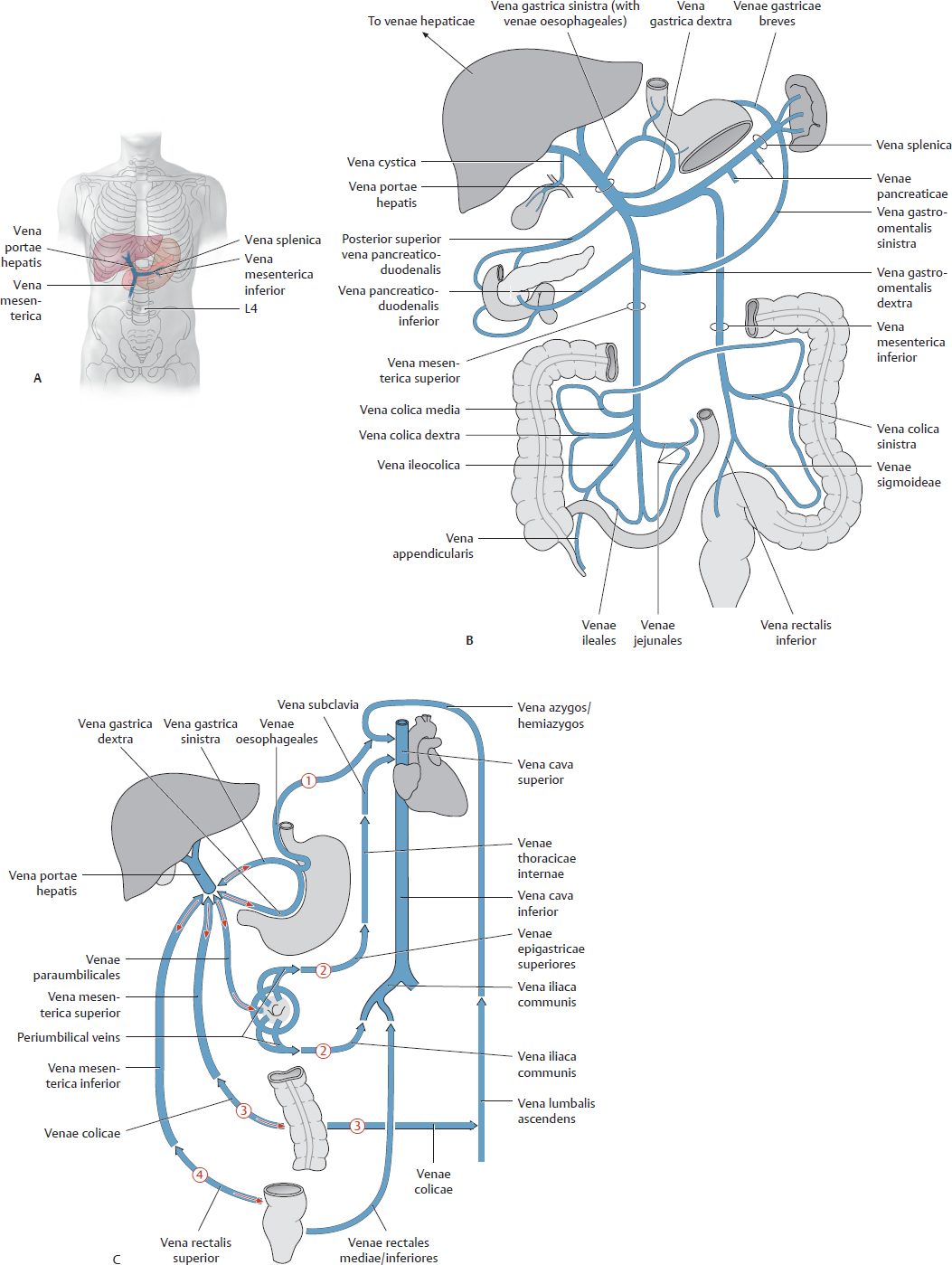

Fig. 15.103 Vena portae hepatis

The vena portae hepatis drains venous blood from the abdominopelvic organs supplied by the truncus coeliacus and arteriae mesentericae superior and inferior.

A Location, anterior view.

B Vena portae hepatis distribution.

C Collateral pathways between the portal system and the heart. When the portal system is compromised, the vena portae hepatis can divert blood away from the liver back to its supplying veins, which return this nutrient-rich blood to the heart via the venae cavae. The red arrows indicate the flow reversal in the (1) venae oesophageales, (2) venae paraumbilicales, (3) venae colicae, and (4) venae rectales mediae and inferiores.

Vena Cava Inferior & Venae Mesentericae Inferiores

Fig. 15.104 Vena cava inferior

Anterior view of the female abdomen. Removed: All organs except the left ren and glandula suprarenalis.

Fig. 15.105 Vena mesenterica inferior

Anterior view. Partially removed: Gaster, duodenum, and peritoneum. Removed: Pancreas, omentum majus, colon transversum, and intestinum tenue. Reflected: Hepar and vesica biliaris.

The vena mesenterica inferior is part of the portal system.

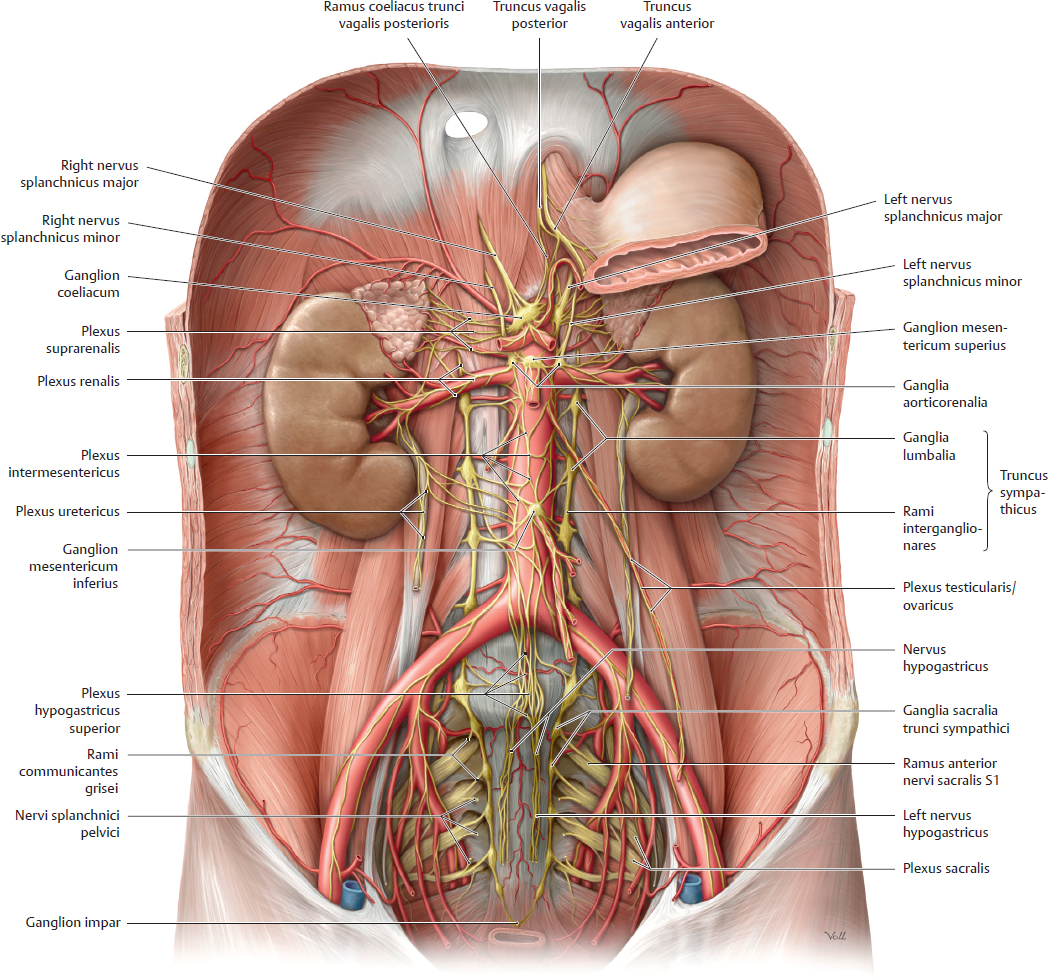

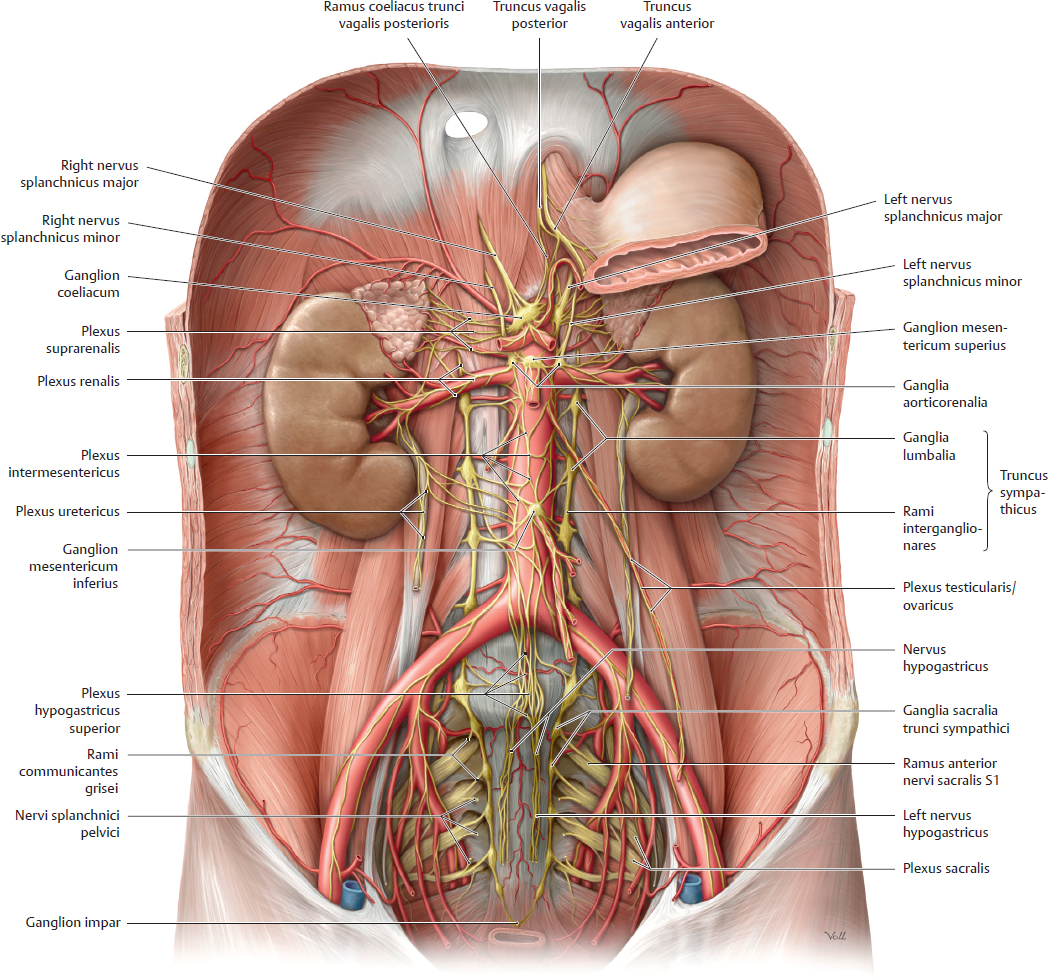

Autonomic Plexuses & Sectional Anatomy of the Abdomen

Fig. 15.106 Autonomic plexuses in the abdomen and pelvis

Anterior view of the male abdomen and pelvis. Removed: Peritoneum, majority of the gaster, and all other abdominal organs except rena and glandulae suprarenales.

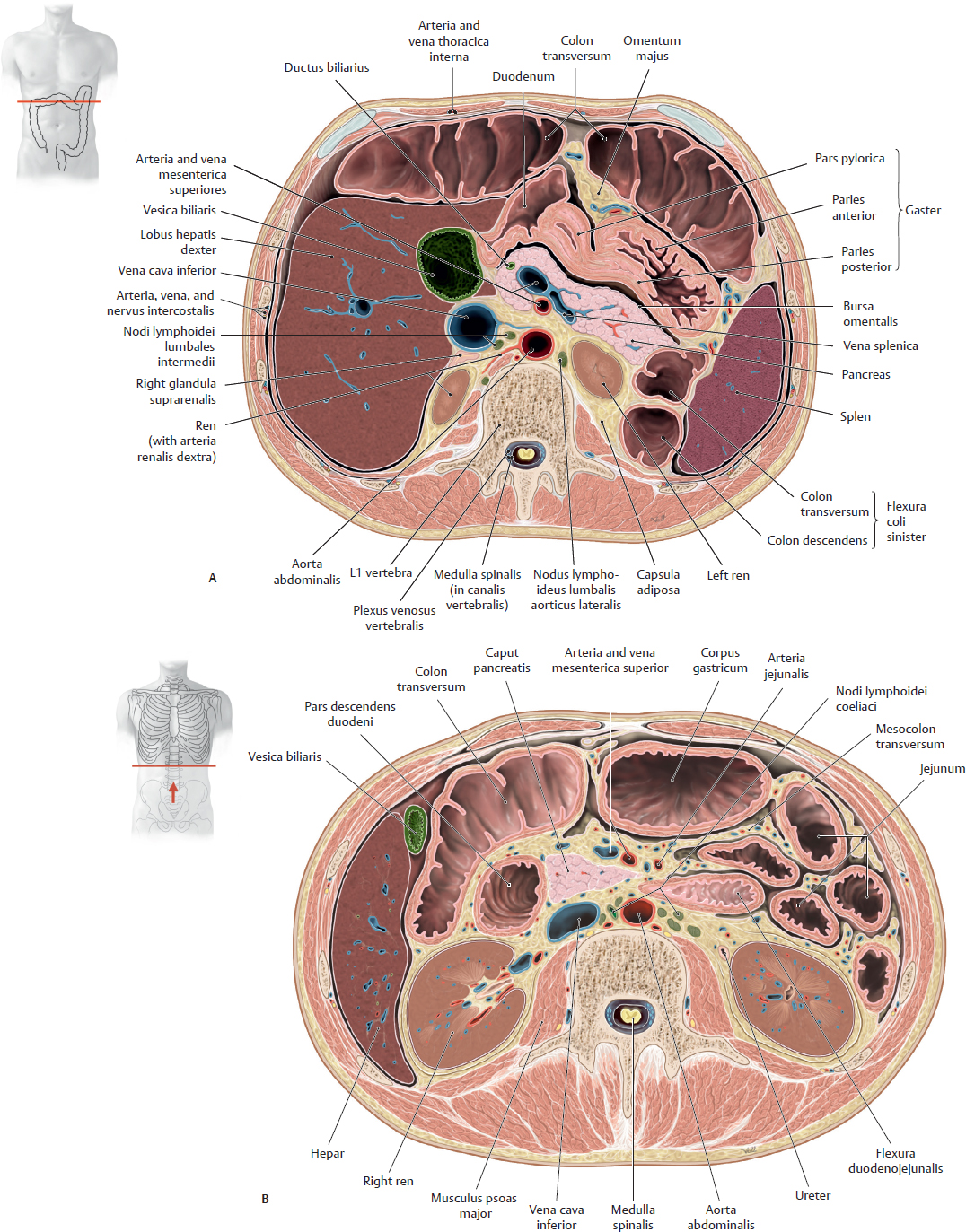

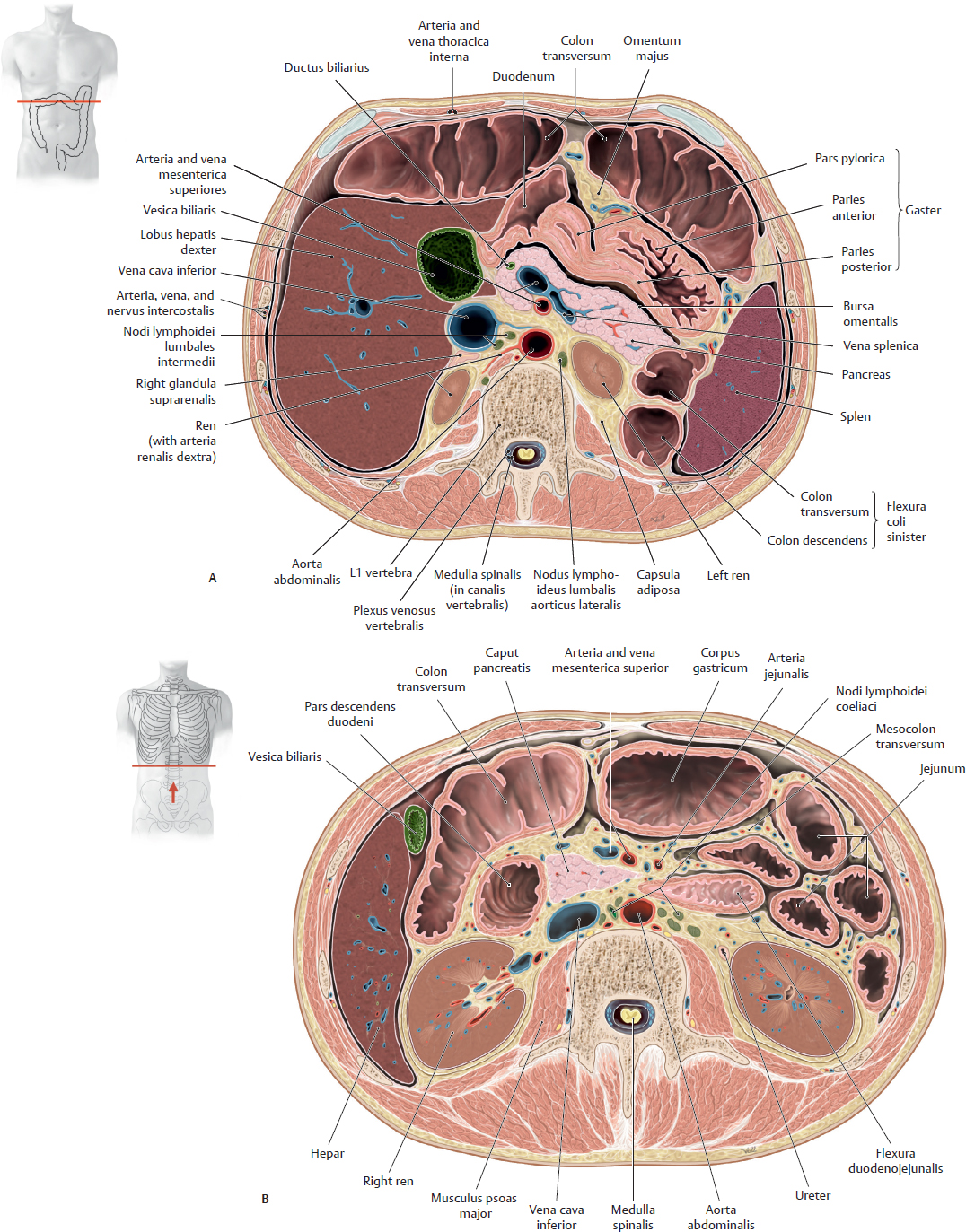

Fig. 15.107 Transverse sections of the abdomen

Inferior view. A Section through L1 vertebra. B Section through L2 vertebra.

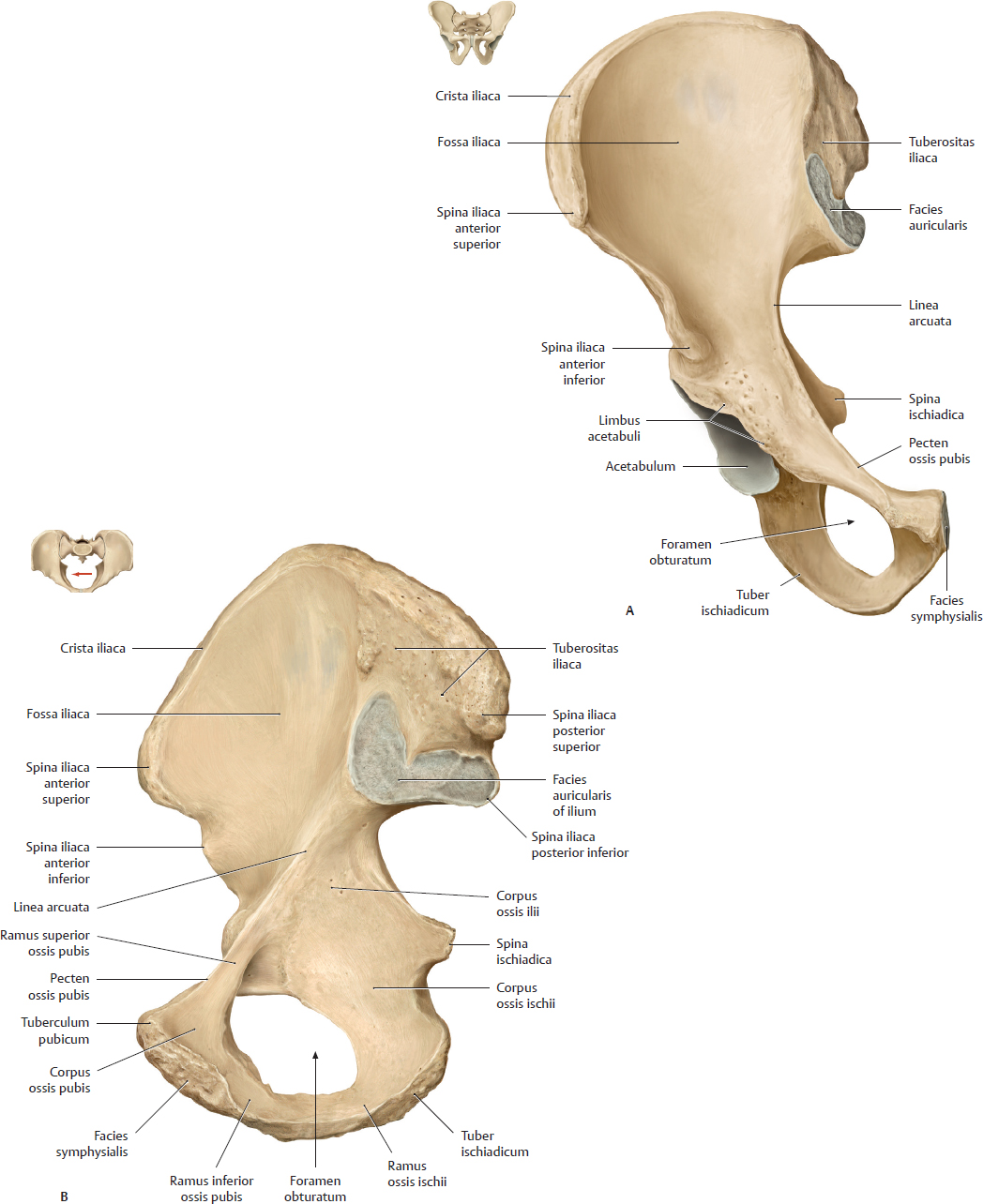

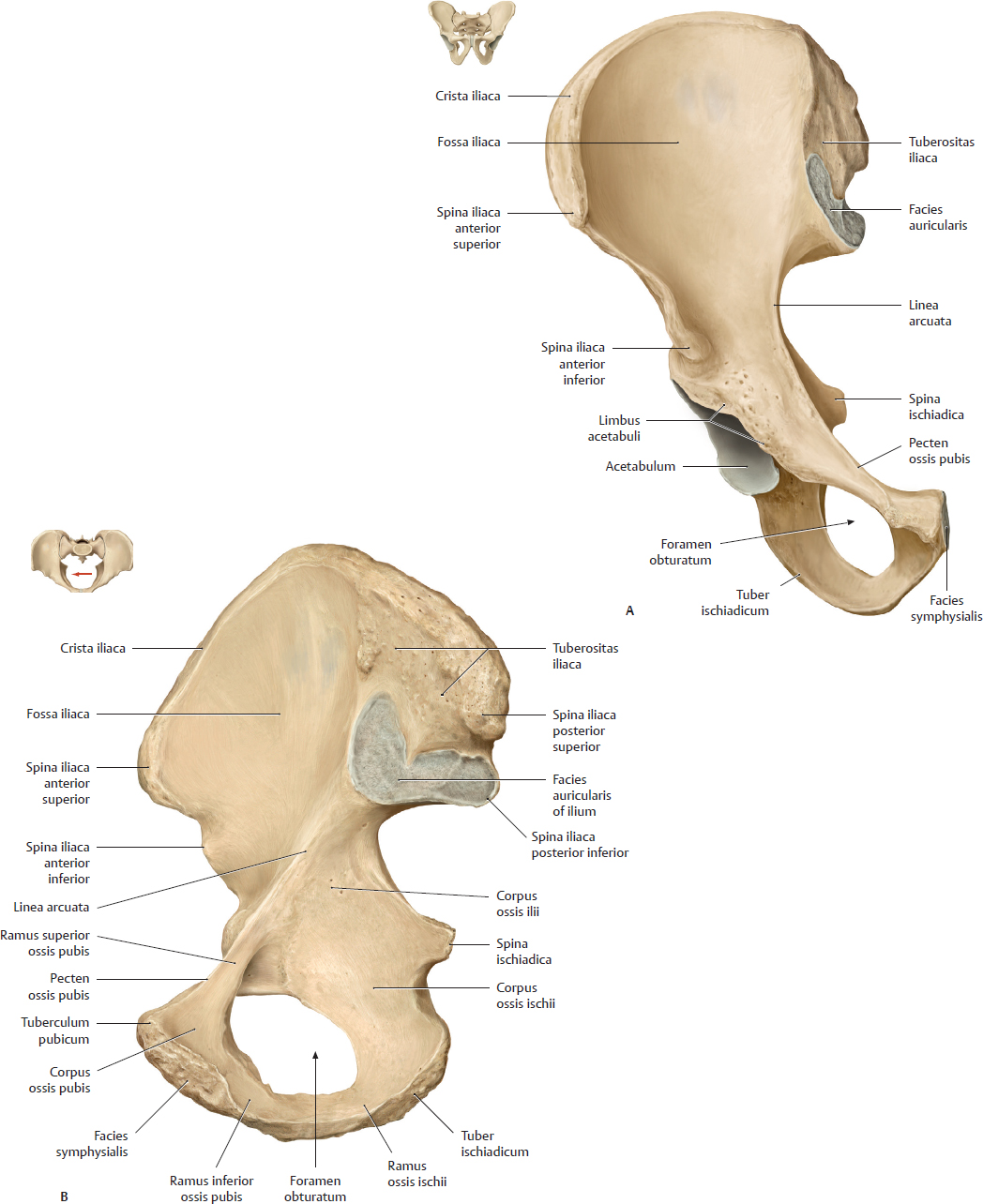

Cingulum Pelvicum & Ligaments of the Pelvis

Fig. 15.108 Cingulum pelvicum

Anterosuperior view. The cingulum pelvicum surrounds the pelvis, the region of the body inferior to the abdomen. It consists of the two ossa coxae and the os sacrum that together connect the columna vertebralis to the femur. The stability of the cingulum pelvicum is necessary for the transfer of trunk loads to the lower limb, which occurs in normal gait.

Fig. 15.109 Os coxae

Right os coxae (male). A Anterior view. B Medial view.

The two ossa coxae are connected to each other at the cartilaginous symphysis pubica and to the os sacrum via the articulationes sacroiliacae, creasting the pelvic brim (seen in red in Fig 15.108).

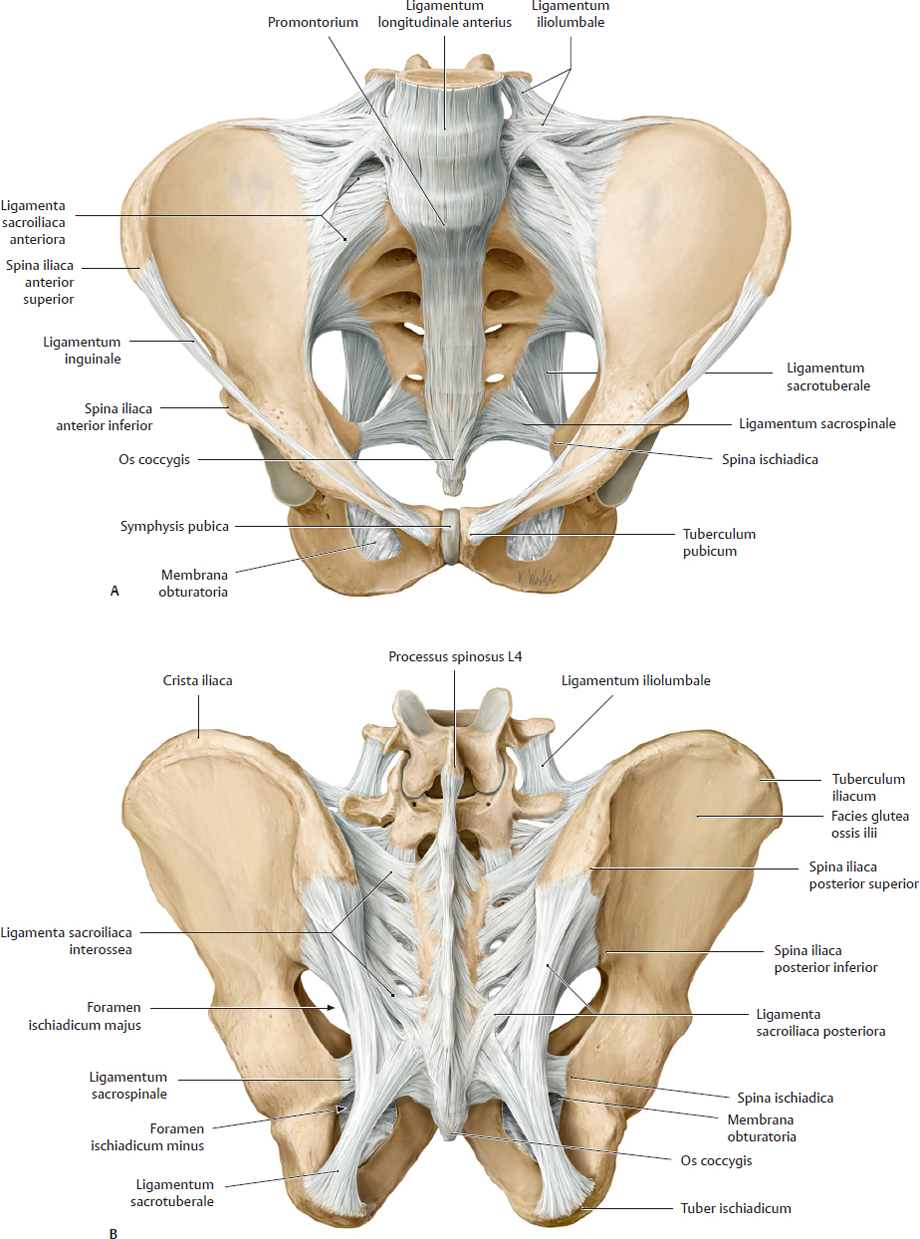

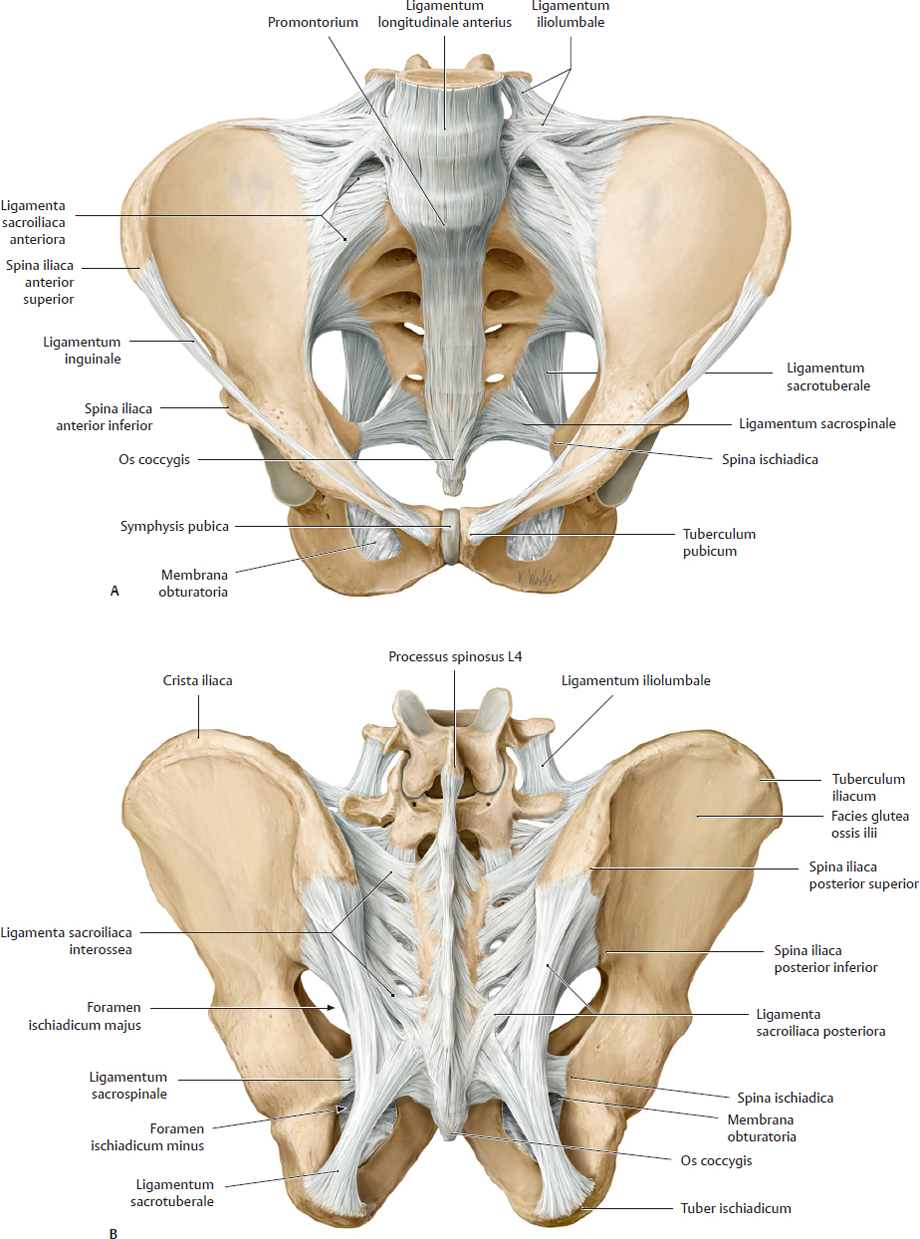

Fig. 15.110 Ligaments of the pelvis

Male pelvis. A Anterosuperior view. B Posterior view. Removed on the right side: some of the ligamenta sacroiliaca posteriora to reveal the ligamenta sacroiliaca interossea.

Contents of the Pelvis

Fig. 15.111 Male pelvis

A Parasagittal section, viewed from the right side. B Midsagittal section, viewed from the right side.

Fig. 15.112 Female pelvis

A Parasagittal section, viewed from the right side. B Midsagittal section, viewed from the right side.

Arteries & Veins of the Pelvis

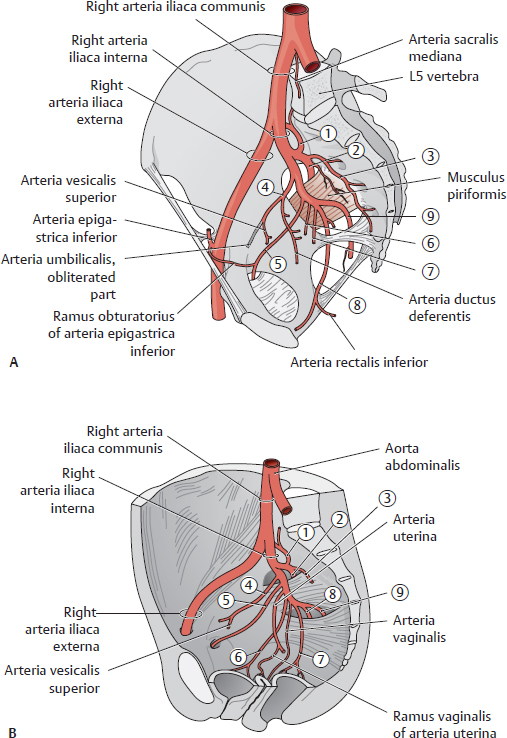

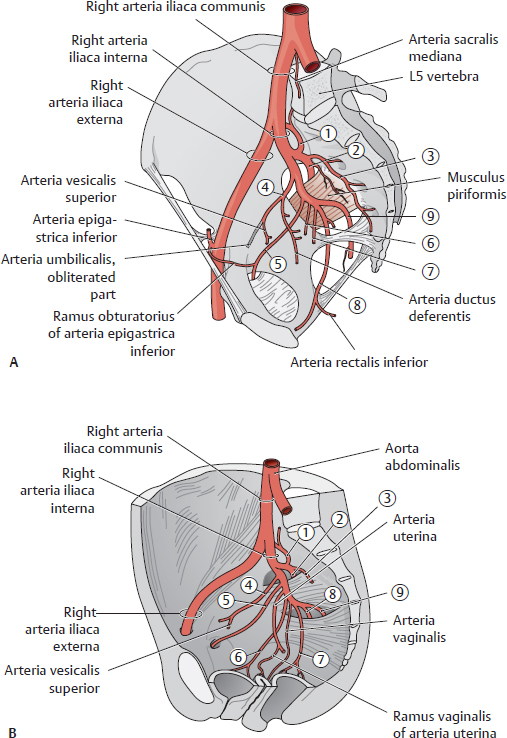

Fig. 15.113 Arteries of the pelvis

A Male pelvis. B Female pelvis. See Table 15.17.

Fig. 15.114 Veins of the pelvis

A Male pelvis. B Female pelvis. See Table 15.18.

Table 15.17 Branches of the arteria iliaca interna

The arteria iliaca interna gives off five parietal (pelvic wall) and four visceral (pelvic organs) branches.* Parietal branches are shown in italics. |

Branches |

|

Arteria iliolumbalis |

|

Arteria glutea superior |

|

Arteria sacralis lateralis |

|

Arteria umbilicalis |

A. ductus deferentis |

Arteria vesicalis superior |

|

Arteria obturatoria |

|

Arteria vesicalis inferior |

|

Arteria rectalis media |

|

Arteria pudenda interna |

Arteria rectalis inferior |

|

Arteria glutea inferior |

* In the female pelvis, the arteriae uterina and vaginalis arise directly from the anterior division of the arteria iliaca interna. |

Table 15.18 Venous drainage of the pelvis

Tributaries |

|

Vena glutea superior |

|

Vena sacralis lateralis |

|

Venae obturatoriae |

|

Venae vesicales |

|

Plexus venosus vesicalis |

|

Venae rectales mediae (plexus venosus rectalis) (also venae rectales superior and inferiores, not shown) |

|

Vena pudenda interna |

|

Venae gluteae inferiores |

|

Plexus venosus prostaticus |

|

Plexus venosi uterinus and vaginalis |

The male pelvis also contains veins draining the penis and scrotum. |

Fig. 15.115 Blood vessels of the pelvis

Idealized right hemipelvis, left lateral view. A Male pelvis. B Female pelvis.

Oxygenated and nutrient-rich fetal blood from the placenta passes to the fetus via the vena umbilicalis.

Oxygenated and nutrient-rich fetal blood from the placenta passes to the fetus via the vena umbilicalis. Approximately half of this blood bypasses the liver (via the ductus venosus) and enters the vena cava inferior. The remainder enters the vena portae hepatis to supply the liver with nutrients and oxygen.

Approximately half of this blood bypasses the liver (via the ductus venosus) and enters the vena cava inferior. The remainder enters the vena portae hepatis to supply the liver with nutrients and oxygen. Blood entering the atrium dextrum from the vena cava inferior bypasses the ventriculus dexter (as the lungs are not yet functioning) to enter the atrium sinistrum via the foramen ovale, a right-to-left shunt.

Blood entering the atrium dextrum from the vena cava inferior bypasses the ventriculus dexter (as the lungs are not yet functioning) to enter the atrium sinistrum via the foramen ovale, a right-to-left shunt. Blood from the vena cava superior enters the atrium dextrum, passes to the ventriculus dexter, and moves into the truncus pulmonalis. Most of this blood enters the aorta via the ductus arteriosus, a right-to-left shunt.

Blood from the vena cava superior enters the atrium dextrum, passes to the ventriculus dexter, and moves into the truncus pulmonalis. Most of this blood enters the aorta via the ductus arteriosus, a right-to-left shunt. The partially oxygenated blood in the aorta returns to the placenta via the paired arteriae umbilicales that arise from the arteriae iliacae internae.

The partially oxygenated blood in the aorta returns to the placenta via the paired arteriae umbilicales that arise from the arteriae iliacae internae.

Planum transpyloricum

Planum transpyloricum Planum subcostalis

Planum subcostalis Planum supracrestale

Planum supracrestale Planum transtuberculare

Planum transtuberculare Planum interspinale

Planum interspinale