This tour begins at the Dismal Swamp Canal Welcome Center in northern Camden County and makes its way through Pasquotank, Perquimans, Chowan, Washington, and Bertie Counties before ending at Murfreesboro in Hertford County. Among the highlights are the Dismal Swamp Canal, the homesite of General Isaac Gregory, historic , Hertford, historic Edenton, Rosefield, and historic Murfreesboro.

Total mileage:

approximately 199 miles.

This tour traverses the Albemarle, the most ancient of North Carolina’s political subdivisions. Established in 1664 by the Lords Proprietors in their new province of Carolina, Albemarle County covered 1,600 square miles in the northeastern part of the colony. Named for George Monck, duke of Albemarle, one of the Lords Proprietors, the massive county was the site of the first permanent white settlement in what is now North Carolina.

The area is rich in sites related to the Revolutionary War. “The Cradle of the Colony,” as the region is known, produced many of the leaders who guided North Carolina through the hardships of the war and toward the creation of the new republic. For example, tour stops include the homes of the man known as “the Father of the American Revolution in North Carolina,” a signer of the Declaration of Independence, two signers of the Constitution, and a justice on the first United States Supreme Court.

The tour begins at the Dismal Swamp Canal Welcome Center, located on the western side of U.S. 17 approximately 3 miles south of the Virginia line in Camden County, which is in the far northeastern corner of North Carolina.

Named for Sir Charles Pratt, earl of Camden, a distinguished English jurist and statesman who strongly opposed British taxation of the American colonies, Camden County was born of the Revolution in 1777, when it was carved from adjacent Pasquotank County. Camden men fought in large numbers for the American cause. By war’s end, the county had provided 416 officers and men, a total greater than any other county in old Albemarle.

The welcome center is located on the fringes of the Great Dismal Swamp. Though this vast wilderness of marshes, peat bogs, lakes, and cypress forests was almost four times as large in Revolutionary War times as it is today, it still covers almost three hundred thousand acres, an area about the size of Rhode Island. Approximately 60 percent of the swamp is located in North Carolina within Camden, Currituck, Pasquotank, Perquimans, and Gates Counties.

On May 25, 1763, a thirty-one-year-old soldier and surveyor from Virginia received his first taste of the Great Dismal. George Washington, the same man who subsequently served as commander in chief of the American armies in the Revolutionary War, made his initial visit to the swamp to inspect the nearly fifty thousand acres granted to a group of land and timber speculators known as “the Adventurers for Draining the Dismal Swamp.” Among Washington’s associates in the venture were Patrick Henry and Richard Caswell, two statesmen who would play leading roles in the upcoming fight for independence. (For additional information on Caswell, see The Coastal Rivers Tour, pages 56–59.) Washington made five trips to the Great Dismal between 1763 and 1768.

The Dismal Swamp Canal Visitor Center was developed by the state of North Carolina in 1989 to provide travel information for motorists as well as for water traffic on the canal. The docks just west of the parking area are a good place to view the canal and the adjoining swamp wilderness.

One of the earliest legends of the Great Dismal had its origins during the American Revolution. A French warship filled with gold to pay French troops in America sailed to Hampton Roads to avoid a ferocious storm. A British man-of-war sighted the enemy ship, promptly gave chase, and forced the fleeing vessel into the shallow waters of the Elizabeth River. There, the French captain ordered his crew to load the precious cargo onto smaller boats and to burn the ship.

Fearing a British capture of the treasure, the French sailors buried the gold in the river and on its banks, then sought refuge in the Great Dismal. But their attackers hunted them down. In the course of the vicious hand-to-hand combat that followed, all of the French crewmen died without divulging the location of the hidden gold. According to legend, visitors can still hear the voices of the French sailors emanating from the swamp on some nights.

From the parking lot of the visitor center, turn right and proceed south on U.S. 17. This highway, known as George Washington Highway, parallels the Dismal Swamp Canal on the 5-mile drive to the town of South Mills.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the 22-mile canal has been in almost continuous operation since construction began in 1790. Hugh Williamson, one of North Carolina’s signers of the Constitution, planted the seed for the canal project in letters to George Washington while the Continental Congress was in session. President Washington ultimately gave his blessing to the waterway in 1785, and the legislatures of Virginia and North Carolina granted their approval in 1787 and 1790, respectively.

Just north of South Mills, turn right on U.S. 17 Business and proceed 1.3 miles to S.R. 1243. Turn right and follow S.R. 1243 for 0.7 mile into the heart of the village. Here, the southern locks of the canal bear testimony to a project initiated in Revolutionary War times. A state highway historical marker for the canal stands nearby.

Return to U.S. 17 Business. Turn right and proceed 0.1 mile to N.C. 343. Follow N.C. 343 south for 12.9 miles to U.S. 158 in Camden. Continue south on U.S. 343 for 2.2 miles, then turn right on S.R. 1132. Near this junction was the estate of Abner Harrison (1745–90). In 1776, the North Carolina Provincial Congress appointed Harrison to serve as a confiscation commissioner, an office unique to the Revolutionary War. Harrison’s official duties were “to receive, take care of and make disposition of” the property of Tories and other disloyal persons.

Drive south on S.R. 1132 for 1.1 miles to its terminus near the mouth of Areneuse Creek. This site, now being developed as residential property, was confiscated from Tories during the Revolution. It was granted to Lieutenant Colonel Hardy Murfree as a reward for his distinguished service in the Continental Army. Murfree was the namesake of Murfreesboro, a town visited later in this tour.

Return to the junction with N.C. 343, turn right, and drive 1.6 miles south to S.R. 1121. Turn left and proceed 0.5 mile to the site of Fairfield (Fairfax) Hall, the home of General Isaac Gregory (1737–1800). Until the three-story brick English manor house collapsed into a pile of rubble several decades ago, it stood as a monument to one of the most distinguished Revolutionary War officers of northeastern North Carolina.

General Gregory grew up in the house and inherited it upon his father’s death. Before the war, he served as a local judicial official and opposed the Stamp Act. He was a delegate to the Provincial Congresses of 1775 and 1776 and was instrumental in the establishment of Camden County. Gregory began his military service in September 1775, when he was commissioned lieutenant colonel of the militia. On May 12, 1779, the North Carolina General Assembly promoted him to brigadier general.

General Gregory’s finest hour came, ironically, in the devastating American defeat at Camden, South Carolina, in 1780. In the course of that fight, the American militia acquitted itself rather poorly. Gregory and his men were an exception. During the intense battle, the general’s horse was shot from under him and he was twice wounded by bayonets, the scars of which he bore for the rest of his life. Lord Charles Cornwallis, the commander of British forces in the South, mistakenly listed Gregory among the American fatalities at Camden.

During March and April 1781, Gregory was back in northeastern North Carolina to defend against potential raids from British camps just across the line in Virginia. Before the Redcoats abandoned one of those camps, their commander, Captain Stevenson, penned a fanciful letter wherein he suggested that General Gregory might betray the American forces to the British. Stevenson then affixed Gregory’s signature to the letter.

When American soldiers came upon the deserted British camp, they found the letter. They turned it over to military authorities, who promptly charged Gregory with treason and scheduled a court-martial. In the meantime, Captain Stevenson learned of the sensation the letter had caused. With great dispatch, he forwarded a communication that explained the source of the letter. Though Gregory was exonerated, he was greatly puzzled as to how anyone could doubt his loyalty in light of his record of service in the fight for independence.

In a letter to George Washington, Hugh Williamson offered great praise for Gregory: “Gen’l Gregory is recommended as a gentleman where Character as a soldier and Citizen stands high in the universal esteem of his fellow Citizens. He is a man of respectable property; has the full confidence of his Country and is the constant Enemy to public officers suspected of corrupt practices.”

After his death in April 1800, Gregory was buried on his plantation. His mansion was located on the left side of the road in what is now a field. On the opposite side of the road is an ancient family burial ground.

From the site of the Gregory plantation, retrace your route to the N.C. 343 junction. Turn left on N.C. 343 and drive 3 miles to Shiloh. The most famous landmark here is Shiloh Baptist Church. Although the existing sanctuary was constructed in 1848, the church was organized in 1727, making it the oldest Baptist church in North Carolina.

During the Revolutionary War era, the pulpit at Shiloh Baptist Church was filled by Reverend Henry Abbott, one of the most learned men in North Carolina. Born in London, Abbott was an ardent Patriot from the onset. A champion of individual liberties, he is recognized as the author of the article in the first state constitution that acknowledges that “all men have natural and inalienable rights to worship almighty God according to the dictates of their own conscience.”

Abbott died in 1791 and is believed to have been buried at a site 5 miles northeast of Shiloh.

Among the graves in the historic cemetery at Shiloh Baptist Church is that of Dempsey Burgess (1751–1800). In 1775 and 1776, Burgess served as a youthful member of the Provincial Congresses that met at Hillsborough and Halifax. He rendered distinguished service as a militia officer, rising to the rank of colonel. In the aftermath of the war, he became the first Camden County resident to be elected to the United States House of Representatives, serving from 1795 to 1798 as a member of the Fourth and Fifth Congresses.

From the church, return to Camden via N.C. 343. Just north of Shiloh, the route passes the road leading to Texaco Beach, a small resort on the Pasquotank River. Nearby was the plantation of Captain John Forbes (1737–81). Forbes was killed in action at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse in March 1781.

Turn left off N.C. 343 onto U.S. 158 at Camden and drive west. Near the intersection are state historical markers for Isaac Gregory and Dempsey Burgess. The 3.2-mile drive from Camden to Elizabeth City is via an ancient causeway and the Pasquotank River Bridge.

Nearby is the site of Lamb’s Ferry. A river ferry was operated here by the Lamb family from 1779 to 1912. Colonel Gideon Lamb (1740–81), the man to whom the ferry franchise was initially granted, was one of the many unsung North Carolina heroes of the American Revolution.

While serving as a delegate to the Provincial Congress at Halifax in April 1776, Lamb was commissioned a major in the Continental Army. After meritorious service in the South early in the war, he accompanied his troops to reinforce George Washington in the North. An active participant in the important engagements at Trenton, Germantown, and Brandywine, Lamb was court-martialed by General Jethro Sumner for his conduct at the latter battle. A court of inquiry subsequently cleared him, noting that “the Charge is not Supported” and recommending that Lamb “be Acquitted with Honour.”

Lamb spent the last three years of his life performing a vital but thankless task. He was charged with recruiting, organizing, and supplying Continental forces in eastern North Carolina. Stricken with “bilious fever,” he died at his home, Mount Pleasant, which stood nearby, on November 8, 1781, less than three weeks after his Continental Army had enjoyed the sweet taste of success at Yorktown, Virginia.

Colonel Lamb was the elder member of a rare father-and-son team of commissioned officers. His son Abner was sixteen when the colonies declared their independence in 1776 and only twenty when he sustained a crippling wound at Eutaw Springs, South Carolina, on September 8, 1781, five weeks before Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown.

Just west of the Lamb’s Ferry site, the bridge affords a magnificent view of the 40-mile-long Pasquotank River, which marks the boundary between Camden and Pasquotank Counties. This beautiful river provided local residents vital access to Albemarle Sound during the Revolution.

Once across the bridge, continue on U.S. 158 as it heads west through Elizabeth City and runs conjunctively with Elizabeth Street for six blocks. Turn north on North Road Street. After 0.9 mile, turn left on U.S. 17 (Hughes Boulevard). The Museum of the Albemarle, a branch of the North Carolina Museum of History, is located 3.6 miles ahead.

U.S. 17 crosses into Perquimans County approximately 7 miles west of the museum. After crossing the county line, continue 6.5 miles to where U.S. 17 Business splits off U.S. 17 Bypass. Turn right on U.S. 17 Business and proceed 1.1 miles to Hertford. Just before reaching this quaint, old river town, you will cross the scenic Perquimans River via the only S-shaped bridge in the United States and the largest of its kind in the world.

Once across the bridge, drive three blocks on U.S. 17 (now Church Street) and park in one of the on-street spaces near the courthouse in downtown Hertford.

At the beginning of the American Revolution, Hertford, named for a town in England, was a thriving river village. Many of its street names still proclaim their English heritage: Hyde Park, Covent Garden, Punch Alley.

From the courthouse, follow Church Street to Grubb Street. One of the most famous hostelries in northeastern North Carolina in the last third of the eighteenth century once stood near here. The Eagle Tavern opened in a home in 1762 and quickly grew into a sprawling, two-and-a-half-story, twenty-five-room inn that covered six lots.

According to tradition, George Washington lodged at the Eagle while he was surveying the Great Dismal Swamp. William Hooper, one of North Carolina’s three signers of the Declaration of Independence, was among the other notable guests at the tavern in the eighteenth century. In 1915, the old frame structure was razed.

Return to your car and follow Church Street two blocks south to Dobb Street. Two nearby state historical markers pay tribute to a pair of native sons who gained fame during the Revolutionary War era.

One of the markers honors John Skinner (1760–1819). Born into one of the county’s earliest families, Skinner served several tours in the Continental Army. When North Carolina officially joined the Union, President Washington appointed him as the state’s first federal marshal. He held that post for four years.

The other historical marker honors John Harvey, a man who was instrumental in obtaining the charter for Hertford. Harvey’s life is chronicled later in this tour.

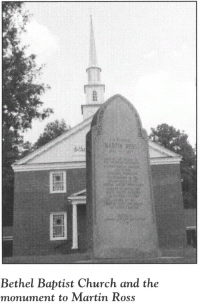

Continue on Church Street as it leads out of town. After 1.9 miles, you will reach U.S. 17 Bypass/N.C. 37. Turn right onto U.S. 17 Bypass, proceed 2.5 miles, then turn left on S.R. 1340, which leads south on the river peninsula called Harveys Neck. After 1.6 miles on S.R. 1340, turn right onto S.R. 1341. You will see Bethel Baptist Church on the left just after the turn.

The handsome two-story sanctuary was built more than a half-century after the war. But the old church cemetery to the rear contains some of the oldest accessible graves in the county. Among the eighteenth-century grave sites here is that of Charles Blount, a Revolutionary War soldier.

A large stone monument on the front lawn of the church pays tribute to another Patriot. Martin Ross (1762–1828) came home to northeastern North Carolina and took up the ministry soon after the war. A Baptist missionary, he founded Bethel and other area churches. The monument proclaims him to be “the Father of the Baptist State Convention of North Carolina.”

Return to S.R. 1340 and drive 0.2 mile south to S.R. 1339. Turn left and proceed 2 miles to the Isaac White House. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, this handsome two-story frame dwelling was constructed around 1760. During the American Revolution, it was owned and occupied by Jonathan Skinner, who served Perquimans County as a wartime delegate in the North Carolina General Assembly.

Continue on S.R. 1339 for 2.3 miles to S.R. 1336. Turn right and drive 6.5 miles south to the southern tip of Harveys Neck on Albemarle Sound. The road ends at the Harvey Point Testing Area, a restricted national defense facility.

Harveys Neck bears the name of one of the most important and influential families in early North Carolina history. Thomas Harvey, the progenitor of this illustrious clan, settled on a 691-acre tract near the current tour stop in the last quarter of the seventeenth century. He began an almost century-long tradition of public service by the Harvey family when he was elected justice of the county court of Albemarle in 1683. Eleven years later, he served as deputy governor of the colony. From 1695 until his death in 1699, he was the chief executive of the colony, since the governor was absent for most of that time.

His son, Thomas Harvey, Jr., built upon the family tradition of public service until his death in 1729 at the age of thirty-six. He was buried beside his father. In 1865, when erosion began to claim the cemetery, his grave and marker were moved to the Harvey family cemetery at Belgrade Plantation. Today, personnel from the nearby military installation maintain the ancient burial ground. Harvey’s gravestone, the oldest in the county, can still be seen.

When Thomas Harvey, Jr., died, he left a four-year-old son, John. Seventeen years later, young John Harvey was elected to the colonial assembly. Over the next thirty years, he established himself as one of the most dynamic statesmen and political firebrands in the colony.

In 1766, his unanimous election as speaker of the colonial assembly propelled him to the forefront of the growing crisis with Great Britain. Within two years, he was North Carolina’s undisputed leader of the opposition to British colonial policies.

As tensions heightened, Royal Governor Josiah Martin issued a proclamation in 1774 that forbade the defiant Harvey and his political associates from convening a provincial congress. Nevertheless, “Bold John,” as Harvey was known, convened the First Provincial Congress at New Bern on August 25, 1774. He was chosen moderator of that assembly, which elected North Carolina’s first delegates to the Continental Congress and passed a “no tea” resolution. Members of the First Provincial Congress empowered “Bold John” to convene another assembly at his discretion. Accordingly, the Second Provincial Congress met on April 3, 1775, much to the consternation of Governor Martin.

Tragically, the man who earned the title of “Father of the American Revolution in North Carolina” did not live to see the fruits of his dream for an independent America. His death in May 1775 was the result of a fall from a horse. His large granite tomb at Belgrade now rests in the waters of Albemarle Sound.

Turn around and drive north on S.R. 1336 for approximately 6.5 miles as the road parallels the Perquimans River. The Skinner cemetery is hidden in dense overgrowth near the junction with S.R. 1339. Here, a large marble slab marks the grave of General William Skinner (1728–98), a militia commander who helped save the day for the Americans at Great Bridge, Virginia, in December 1775.

From the cemetery, drive 2.1 miles north on S.R. 1336 to U.S. 17. Turn left on U.S. 17 and proceed 11.7 miles to Edenton; the route crosses into Chowan County after 7 miles.

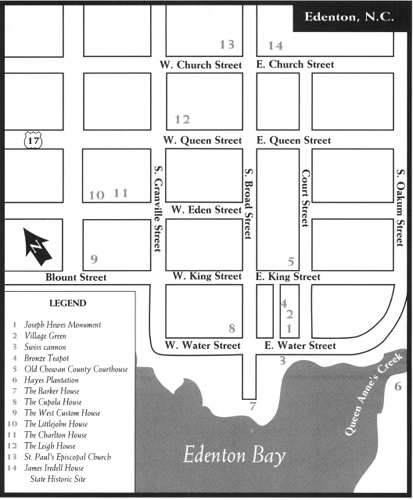

In Edenton, U.S. 17 runs conjunctively with Broad Street as it winds its way through the heart of this venerable city. The sheer number of state highway markers along Broad Street relating to the Revolutionary War era gives a hint of the importance of Edenton and its residents in the struggle for American independence.

South Broad Street dead-ends at Water Street near the waterfront. Park at or near East Water Street to begin a brief walking tour along the historic waterfront. Begin at the Village Green, which is bounded by East Water Street, Court Street, King Street, and Colonial Avenue. This ancient public area features flowers, walkways, monuments, and a green lawn that slopes gracefully toward the waterfront. It may seem difficult to believe that it once housed stocks, racks, and a pillory and served as the military training site.

A small public park along the water at the foot of the Village Green offers a splendid view of Edenton’s picturesque setting on Queen Anne’s Creek, a tributary of the Chowan River. In 1712, the colonial assembly authorized a town to be laid out at the forks of the creek. Soon thereafter, Governor Charles Eden, the man for whom the town is named, established his residence nearby on the Chowan. As a result, Edenton served as North Carolina’s unofficial capital until 1740. Its economic vitality during the colonial period was enhanced by its designation as the Port of Roanoke, an official port of entry. Edenton remained one of the leading cities in the colony on the eve of the American Revolution. Blessed with a wealth of citizens of rare talents and abilities, it assumed a leading role in the struggle for independence.

Two centuries later, reminders of the revolutionary spirit that pervaded Edenton are evident throughout town. For example, the three Swiss cannon prominently displayed at the park have a fascinating story behind them. Captain William Boritz brought a shipment of twenty-three cannon to Edenton in 1778 aboard his ship, The Holy Heart of Jesus. Two Edenton Patriots, Thomas Benbury and Thomas Jones, had, with the aid of Benjamin Franklin, purchased the artillery pieces in France for use in the war effort. When Boritz arrived at Edenton with his important cargo in July 1778, he attempted to levy a transportation charge of 150 pounds of tobacco for every 100 pounds of cannon. But all of the tobacco in the warehouses of Edenton did not total the combined weight of the heavy guns!

Why the cannon were ultimately dumped into the dark waters of Edenton Bay is a subject of dispute. One tradition maintains that they remained on board the anchored ship until British troops threatened the town, at which time patriotic citizens pushed them into the water to prevent their being captured by enemy forces. A more likely story is that the unyielding Boritz ditched the cargo when he realized that his demands were not going to be met.

Although some of the cannon remain in their watery grave, six were rescued for use during the Civil War. Three of the recovered cannon are now mounted on the Edenton waterfront, and others are displayed on Capitol Square in Raleigh.

From the park, walk across Water Street to the Joseph Hewes Monument, located on the southern edge of the Village Green.

During the Revolution, an outside observer remarked that “within the vicinity of Edenton,” there were “in proportion to its population a greater number of men eminent for ability, virtue, and erudition than in any other part of America.” Foremost in the ranks of Edenton’s statesmen in the quest for independence were Joseph Hewes, Samuel Johnston, Hugh Williamson, and James Iredell.

Joseph Hewes earned the respect and admiration of his colleagues as one of the most influential members of the Continental Congress. Some historians consider him the father of the American navy. In effect, his appointment to the Naval Board in 1775 made him the first secretary of the United States Navy. In that position, Hewes procured John Paul Jones’s commission in the Continental Navy. By so doing, he provided America with its first naval hero. (For more on Jones’s connection to North Carolina, see The First for Freedom Tour, page 44.)

In early 1776, the growing tensions between Great Britain and the colonies led Hewes to remark that “nothing is left but to fight it out.” He wrote, “I have furnished myself a good musket and bayonet, and when I can no longer be useful in council, I hope I shall be willing to take the field.” Representing North Carolina at the Continental Congress in Philadelphia later that year, he proudly affixed his signature to the Declaration of Independence.

In 1779, as the war wore on, the forty-nine-year-old Hewes was still laboring on the most important and busiest committees of the Continental Congress. Suddenly, his health broke. Unable to travel, he died in Philadelphia on November 10. The stunned members of Congress attended his funeral and burial at Christ Church as a body. In respect to their fallen comrade, they declared a one-month period of mourning. Hewes was immediately recognized as one of the architects of the American nation. One statesman eulogized him thus: “His name is recorded on the Magna Carta of our liberty—his fame will lie until the last vestige of American history shall be blotted from the world.”

The Hewes Monument, the only monument to a signer of the Declaration erected by congressional appropriation, was dedicated in Edenton in 1932. Designed by Rogers and Poor, the granite shaft is a fitting tribute to the statesman who, in the spring of 1776, requested instructions from the citizens as to how he should vote on the issue of independence. On April 12, his state answered him. Accordingly, Hewes was the man who made the first utterance for national independence in the Continental Congress when he presented the Halifax Resolves on May 27. (For more information on the Halifax Resolves, see The First for Freedom Tour, pages 33–36.)

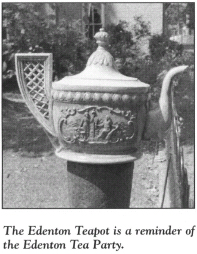

Walk north from the Hewes Monument to the bronze teapot monument on the Colonial Street (western) side of the green. This simple marker was crafted in 1910 to honor the patriotic ladies who participated in the so-called Edenton Tea Party on October 25, 1774.

Considered one of the most revolutionary acts in the colonies prior to the Declaration of Independence, the tea party was convened by Mrs. Penelope Barker in the home of Mrs. Elizabeth King. There, fifty-one local ladies executed resolutions in support of the Provincial Congress, which had banned the import and consumption of British tea.

After agreeing to refrain from drinking British tea until it was once again tax free, the defiant women offered a toast with a drink brewed from dried raspberry leaves. Not surprisingly, the town symbol of Edenton is a teapot.

Because this was the earliest known instance of organized political activity on the part of women in the American colonies, the tea party garnered attention outside Edenton. When a copy of the resolutions was published in a London newspaper, it caused quite a commotion. The London Advisor subsequently ran a political cartoon of the event.

Gracing the northern end of the Village Green is the old Chowan County Courthouse. Constructed in 1767 to replace its 1719 predecessor, the building is one of the finest examples of Georgian public-building architecture in the United States. Even though Chowan County erected a modern courthouse in 1980, the courtroom in the old courthouse is still used, making the structure the oldest functioning courthouse in the state and perhaps the nation. The two-story brick building features a T-shaped roof adorned with a cupola.

Through every day since colonial times, this venerable house of justice, now listed on the National Register of Historic Places, has been used for public affairs. During the American Revolution, local Patriots frequently used it to plot their strategy. When the news reached Edenton that North Carolina had ratified the United States Constitution in 1789, local citizens illuminated the cupola.

Return to your vehicle and proceed a short distance to the end of East Water Street. On the right, a private road leads across a bridge over Queen Anne’s Creek to Hayes Plantation, the historic estate of Samuel Johnston (1733–1816).

Johnston was born in Scotland. While still a baby, he was brought to North Carolina by his uncle, Gabriel Johnston, the Royal governor of the colony.

By 1775, Samuel Johnston had become one of the Patriot leaders of North Carolina. He served with distinction in the First and Second Provincial Congresses, then served as president of the Third and Fourth Congresses after the death of John Harvey. When Royal Governor Josiah Martin fled Tryon Palace in New Bern in May 1775, Johnston became the de facto governor—and the first man to act as governor of the colony without Royal authority.

Throughout the Revolution, he served in the Continental Congress. On December 13, 1787, he was elected governor of North Carolina. At both of North Carolina’s Constitutional Conventions, Johnston, a staunch Federalist, was elected president. Six days after the state ratified the constitution in Fayetteville in November 1789, the legislators elected North Carolina’s first United States senator—Samuel Johnston.

Johnston acquired Hayes Plantation in 1765. He constructed the majestic cupola-topped, two-story mansion with adjoining single-story wings in 1801. Today, the well-maintained home features a two-story portico overlooking Edenton Bay. Johnston’s grave is in the family cemetery on the estate. Among the other notable Revolutionary War figures buried there are James Iredell and Penelope Barker.

At the end of East Water Street, turn around and retrace your route to South Broad Street. Near the intersection, take note of The Homestead, located at 101 East Water Street. Constructed in 1771, this two-story frame dwelling has a Revolutionary War history. Built by a business partner of Joseph Hewes, the house was later acquired by Stephen Cabarrus (1754–1808) for use as his town residence.

As news of the hostilities between Great Britain and its American colonies spread throughout Europe, Cabarrus—the son of nobility in Bayonne, France—grew excited about the American cause and set sail for North Carolina. The twenty-two-year-old foreign Patriot settled in Edenton and quickly took his place as a leader.

A Federalist, Cabarrus served as a delegate to both of the state’s Constitutional Conventions. In 1789, the North Carolina General Assembly elected him to the first of several terms as its speaker. In that position, he cast the deciding vote to locate the permanent state capital in Raleigh.

Turn left on South Broad Street. On the waterfront at 509 South Broad stands the Barker House, one of the most-photographed houses in a town filled with beautiful historic homes. Erected in 1782 several blocks up the street, the two-and-a-half-story clapboard house was moved to its present location in 1952. Thomas Barker, a successful colonial agent for North Carolina in Great Britain prior to the Revolution, and his wife, Penelope, an instigator of the Edenton Tea Party, were the original owners of the house.

Turn around at the end of South Broad Street and drive north to the Cupola House, located at 408 South Broad. This unique two-and-a-half-story frame structure, named for the large octagonal “lantern” atop its roof, was constructed sometime between 1735 and 1758. The most famous structure in Edenton, it was once owned by Dr. Samuel Dickinson and his wife, Elizabeth. During the Revolution, the physician was a staunch Patriot. His spouse participated in the Edenton Tea Party.

Just north of the Cupola House, turn left on West King Street and proceed west; this block contains a fine assemblage of stately mansions built in the nineteenth century. Continue on West King across South Granville to Blount.

The West Custom House, a large, two-story frame dwelling at 108 Blount Street, was the home of Swiss sea captain William Boritz (of waterfront cannon fame) from 1787 until 1798. The house was built before the Revolution.

Just beyond the West Custom House, turn right on Moseley Street, proceed one block north, and turn right on West Eden Street. Several houses here have a connection with the Revolutionary War.

The two-story frame Littlejohn House, located at 218 West Eden, dates from the early 1790s. William Littlejohn, the commissioner of the Port of Roanoke, and his wife, Sarah, one of the signers of the Tea Party Resolutions, built this home.

Charlton House, located at 206 West Eden near the end of the block, was constructed in the 1760s. Jasper Charlton, an attorney and ardent Patriot, built the handsome gambrel-roofed house. His wife, Abigail, was the first signer of the Tea Party Resolutions.

Turn left off West Eden onto South Granville Street. After one block on South Granville, turn right on West Queen Street. The Leigh House, the gambrel-roofed dwelling at 120 West Queen, was the home of Lydia Bennett, another signer of the Tea Party Resolutions. Gilbert Leigh, the architect of the Chowan County Courthouse, built the house in 1756.

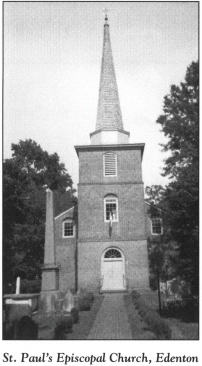

Continue east on West Queen to South Broad Street. Turn left and proceed north on Broad for one block, then turn left onto West Church Street. At the northwestern corner of Broad and Church stands St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, one of the nation’s most historic religious shrines. Constructed in 1736 and beautifully restored after a terrible fire in 1948, the tall, vine-covered brick edifice is the second-oldest church building in North Carolina. Organized in 1701, the congregation is the oldest in the state.

Many of the colonial and Revolutionary War leaders of the Albemarle worshiped in this church. From the outset of the Revolution, the leaders of St. Paul’s supported the American cause. At a meeting on June 19, 1775, members of the local vestry recorded their allegiance to King George III. But with rebellious overtones, they duly noted, “We do solemnly and sincerely promise and engage, under the sanctions of virtue, honor, and the sacred love of liberty and our country, to maintain and support all the acts and resolutions of the said Continental and Provincial Congress to the utmost of our power and ability.”

Adjacent to the church and spilling over into the churchyard is the historic St. Paul’s Cemetery. Buried in these hallowed grounds are numerous leaders from the colonial and Revolutionary War periods. Charles Eden, Thomas Pollock, and Henderson Walker—all colonial governors—are buried here. Among the Patriots interred in the cemetery are Stephen Cabarrus and Thomas Benbury, one of the men responsible for bringing the controversial cannon to Edenton.

From St. Paul’s, drive west on West Church Street to the end of the block. Turn right on Granville and proceed one block. Located at 108 North Granville near the southeastern corner of Granville and Gale, the Williams-Flury-Burton House (also known as the Booth House) was constructed in 1779. Captain Willis Williams, who built the gambrel-roofed structure as a residence, was commander of the Caswell, which helped keep the vital American supply route at Ocracoke Inlet open during the Revolutionary War.

Turn right onto West Gale Street, drive one block to North Broad Street, and turn right. As previously noted, the state historical markers along Broad pay homage to the illustrious sons, places, and events of Edenton during the American Revolution. Of all the markers, one deserves special attention, as there is no other tangible reminder on the Edenton landscape of one of the town’s greatest citizens—Hugh Williamson.

Few Americans in the Revolutionary War period were more talented than Williamson (1735–1819), a well-educated Pennsylvanian. Over the course of his long life, Dr. Williamson served as a physician, educator, scientist, scholar, businessman, and statesman.

Even before his arrival in Edenton, Williamson was a fervent Patriot. By 1776, he had witnessed the Boston Tea Party, been a prisoner of war, and carried secret dispatches for the Continental Congress. He settled in Edenton in 1777. Soon thereafter, Governor Richard Caswell named him surgeon general of North Carolina. In that position, Dr. Williamson was a tireless worker on the battlefield, behind enemy lines, and in the laboratory, where his experiments resulted in improved health for the state’s fighting men.

Not until the war was over did Williamson embark upon a political career. He served in the Continental Congress and represented North Carolina at the Constitutional Convention at Philadelphia in 1787. Some of the key elements of the Constitution—the procedure for impeaching the president and the six-year term for United States senators—were proposed by Williamson. He was one of three North Carolinians to sign the document.

At the intersection of North Broad and East Church, turn left and proceed to the James Iredell House State Historic Site, located at 105 East Church. Erected in 1773, the white-frame Georgian two-story house was purchased by James Iredell, Sr., in 1776.

A native of England, Iredell (1751–99) was the chief legal officer of North Carolina during much of the Revolutionary War. In his role as the state’s attorney from 1779 to 1781, the high-spirited Patriot instituted legal action against Loyalists who interfered with the war effort.

Although he was financially unable to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787, Iredell joined with his brother-in-law, Samuel Johnston, to lead North Carolina toward ratification of the Constitution. In 1789, the year North Carolina adopted the Constitution, President George Washington, without Iredell’s knowledge, appointed him as an associate justice of the first United States Supreme Court. Iredell served on the nation’s highest court for nine years. During his tenure, he wrote the dissenting opinion in the landmark case of Chisholm v. Georgia, which later served as the basis for the Eleventh Amendment to the Constitution. In the presidential election of 1796, three electoral votes were cast for Iredell.

Admission to the house and grounds is free. In one of the upstairs bedrooms, James Wilson, Iredell’s friend and a fellow associate justice of the Supreme Court, died in 1798. Wilson, a Pennsylvanian, was a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Continue east on East Church Street as it leads out of town and becomes N.C. 32. Approximately 3 miles southeast of Edenton, N.C. 32 intersects S.R. 1114. Turn right onto S.R. 1114 and follow it for 5.9 miles as it parallels the Chowan River to its confluence with Albemarle Sound.

Turn right at the junction with S.R. 1113. This short road leads to Mulberry Hill. Built on the sound in 1810, this magnificent, four-story, brick Georgian mansion stands on the site of James Blount’s plantation. Blount served as a militia colonel in the Revolutionary War, and his wife, Anne, signed the Tea Party Resolution.

Return to S.R. 1114, turn right, proceed 0.8 mile to N.C. 32, and turn right again. The spectacular Albemarle Sound Bridge will come into view almost instantly. Proceed over the 5-mile span, built in 1985 to replace a forty-five-year-old structure. The bridge offers a splendid view of the vast Albemarle Sound, one of the important supply routes for the American cause during the Revolutionary War. Midway across the bridge, Chowan County gives way to Washington County. Established in 1799, the county was named in honor of George Washington.

After crossing the bridge, continue south on N.C. 32 for 1.9 miles to U.S. 64. Turn right and drive 8.9 miles west to the junction with U.S. 64 Business at the old lumber town of Roper. Follow U.S. 64 Business through town.

In the heart of Roper, a state historical marker calls attention to Buncombe Hall, one of the plantations that covered the landscape in and around Roper in the colonial and Revolutionary War periods. Edward Buncombe (1742–79), a native of St. Kitts in the British West Indies, first came to the Albemarle in 1766 after inheriting the 1,025-acre plantation from his uncle. Two years later, he took up permanent residence here in the plantation manor, which he had authorized to be constructed in his absence. The elegant structure, the likes of which had never before been seen in the area, was massive. The two-story, L-shaped mansion boasted fifty-six rooms and three cellars.

Among the guests Buncombe welcomed to his mansion in the months leading up to the Revolution were John Harvey and Samuel Johnston. There, on April 3, 1774, the three men sowed the seeds for the first colonial legislature convened in America in defiance of British orders. (For more information, see The Coastal Rivers Tour, pages 75–76.)

By September 1775, Buncombe was a colonel of the militia. The following April, he was transferred to the Continental Army as commander of the Fifth North Carolina Regiment. He trained and equipped the soldiers under his command at his own expense.

After leading his regiment in the engagement at Brandywine, Pennsylvania, on September 11, 1777, Buncombe fought what was to be his last battle at Germantown three weeks later. Shot down on the same field that cost the life of General Francis Nash and many other North Carolinians, the gallant colonel was left for dead by the American forces as they retreated. It was not until the next day, when a British officer recognized him as an old school chum, that Buncombe received medical care.

He was taken to Philadelphia as a prisoner of war. There, his recovery was hampered by a lack of funds, as Buncombe had depleted his cash resources for the military expenses of his regiment. During a sleepwalking episode, he fell down a flight of steps and reopened his wound. Colonel Edward Buncombe, then thirty-six years old, bled to death.

In the aftermath, his magnificent mansion fell into ruin. The last remnants of the historic dwelling vanished when the Norfolk and Southern Railroad brought its line to Roper.

U.S. 64 Business will return you to U.S. 64 on the western side of Roper. Drive 4 miles to N.C. 45 and turn right. After 3.3 miles, N.C. 45 crosses the Roanoke River into Bertie County. Two miles farther north, turn left on N.C. 308, then proceed west for 11.7 miles to where the road merges with U.S. 13/U.S. 17. Turn right and follow U.S. 13/U.S. 17/N.C. 308 for 1.4 miles as it becomes King Street in Windsor, the county seat of Bertie County.

A state historical marker at the intersection of King and Gray Streets notes that the birthplace of William Blount (1749–1800) stands 0.2 mile southwest. Blount was one of the South’s premier statesmen in the late eighteenth century.

To reach the site, turn left on Gray and proceed two blocks to Queen Street. Just after crossing Queen, you’ll notice a narrow paved driveway leading up a knoll to Rosefield, the plantation where Blount was born while his mother was visiting his grandfather, John Gray. The original portion of the existing massive frame house was constructed in 1786 and has remained in the Gray family since that time.

William Blount was involved in the pre-Revolutionary War hostilities that engulfed North Carolina. Both he and his father took part in the Battle of Alamance on May 16, 1771. Soon after the war began, Blount enlisted in the Continental Army. He served as paymaster of the Third North Carolina Regiment for the duration of the conflict.

While a member of the Continental Congress in 1787, Blount represented North Carolina at the Constitutional Convention. Though he was one of the thirty-nine men who signed the Constitution, he was not enthusiastic about it. Blount later explained that he affixed his signature only to make the document “the unanimous act of the States in Convention.”

In 1790, he moved to the part of western North Carolina that was to become Tennessee. President Washington named Blount governor of “the Territory South of the Ohio River” less than a year later. When Tennessee was admitted to the Union in 1796, its legislature elected Blount the first United States senator from the new state.

Return to the intersection with U.S. 13 in Windsor and proceed north. After 18.1 miles, the route crosses into Hertford County. Continue north on U.S. 13 for 4.8 miles as it passes through Ahoskie. Just north of the town, turn left onto N.C. 561, then drive 2.4 miles to Fraziers Crossroads. Colonel John Frazier, the man for whom the community was named, maintained a home here during the Revolutionary War. He served as a Tory officer.

Turn right onto S.R. 1108 at Fraziers Crossroads and drive north 1.8 miles to N.C. 461. Turn right and proceed 3.8 miles east until the route merges again with U.S. 13. Continue north on U.S. 13 for 2.5 miles to U.S. 158 and N.C. 45. Turn right on N.C. 45 and proceed 0.3 mile to Winton, the seat of Hertford County.

Laid out on the banks of the Chowan River in 1766, Winton was named for Benjamin Wynns (1710–88), a planter and militia officer during the Revolution. As a colonel of the Hertford Regiment of the North Carolina militia, he led his soldiers in the Battle of Great Bridge and the siege at Norfolk that followed. Upon his triumphant return to Hertford County in 1776, Colonel Wynns was rewarded with praise from people all along his route.

At the intersection of N.C. 45 and King Street, turn left on King. Follow it for seven blocks to Cross Street, where you’ll note the Hertford-Gates Health Department. Turn left and proceed one block to Taylor Street. Located at the rear of the Health Department building is the Dickinson cemetery, the site of the grave of Eli Foote. Foote was an attorney who remained a Tory during the Revolution but managed to live in accord with his Patriot neighbors after the war. He died in 1792 at the age of forty-four. He was the grandfather of Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

The Chowan River is just north of the cemetery. Downriver from Winton at a place called Wyanoke Ferry, a Tory raiding party torched a riverside settlement as Cornwallis marched through northeastern North Carolina toward Yorktown in July 1781.

Retrace your route to the intersection of U.S. 13 and U.S. 158. Proceed west on U.S. 158 for 10.9 miles to Murfreesboro. Turn right onto Second Street and follow it two blocks to Broad Street. Turn right and go one block to East Street. Turn left on East and follow it to Cedar Street and the site of Old Town Cemetery and King’s Landing.

Pleasantly situated on the western bank of the Meherrin River, Murfreesboro traces its roots to a settlement that began here in 1707. Named for colonial and Revolutionary War leader William Murfree, the town was known as Murfree’s Ferry as early as 1770, when it served as a river port and a “King’s Landing,” where cargo was inspected by representatives of the Crown. Over the past quarter-century, historic Murfreesboro has benefited from a comprehensive restoration project. Today, its streets are lined with stately old homes and buildings that date from colonial times.

When you are ready to leave King’s Landing, retrace your route to U.S. 158, which becomes Main Street as it enters Murfreesboro. A glimpse down the street reveals more than a half-dozen state historical markers, an indication of the historic importance of the town.

Near the intersection of Main and Third Streets stands a marker that honors perhaps the most distinguished visitor ever to call upon Murfreesboro. On the evening of Saturday, February 26, 1825, the Marquis de Lafayette, a Revolutionary War hero, made Murfreesboro and its Eagle Tavern the first stop on his triumphant tour of North Carolina.

To see the site of the Eagle Tavern (later known as the Indian Queen Inn), turn right onto Third and drive two blocks to Broad Street. The tavern stood nearby on the northern side of Broad.

In anticipation of Lafayette’s visit, the citizens of Murfreesboro planned a grand ball for their honored guest. But after Lafayette and his entourage crossed the Meherrin River four miles north of town, the muddy roads proved treacherous. As the party neared Murfreesboro, it found the road up the hill to town virtually impassable. Lafayette’s carriage sank to its axles, the horses mired up to their knees.

It was nine o’clock that night before the weary sixty-eight-year-old general reached town. Among those traveling with him were his son, George Washington Lafayette, and his personal secretary, August Levasseur. As he entered the town, Lafayette was cheered wildly by every able-bodied resident. A brass band serenaded him.

Levasseur later made notes about the arrival: “We … were greatly relieved by the candid hospitality of the inhabitants of Murfreesboro, who neglected nothing to prove to General Lafayette, that the citizens of North Carolina were as sincerely attached to him as those of other states.”

Thomas Maney, the only attorney in Murfreesboro at the time, offered the official welcome: “To you, next to dear, great Washington, we are indebted for the triumph of our arms. We salute you as father of our common country, and we hail you also as a benefactor of the human race and gallant champion of the rights of men.”

Lafayette delivered a reply. Then, because of the lateness of the hour, he was escorted into the inn’s flag-and-bunting-draped dining room, where he enjoyed a meal with forty townspeople. By the time dinner was completed, the clock struck midnight, and the ball was canceled. It was later rescheduled—148 years later, that is. In an effort to raise funds for the restoration of their town, civic-minded Murfreesboro residents held the Lafayette Ball on Saturday, January 27, 1973.

Turn left on Broad Street and proceed to the northwestern corner of Broad and Fourth. Here stands the Wheeler House, a handsome, two-story dwelling of the Revolutionary War era. The bricks used in its construction came from King’s Landing, where they had been brought in as ballast.

John Wheeler, the son of a Revolutionary War surgeon, built the house. Tradition has it that Continental forces used it as a headquarters during the war. Wheeler’s son, John Hill Wheeler, an eminent historian of Revolutionary War–era North Carolina, was born in the house in 1806.

Continue west on Broad for one block to Fifth. The Captain Meredith House has stood on the northwestern corner of this intersection since 1775. Colonel Hardy Murfree, whose house is a block away, was honored at a grand ball in the Captain Meredith House in 1781 upon his return from the Revolutionary War.

The Murfree House, better known as Melrose, is one of the most distinctive homes in a city blessed with historic structures. To see it, continue west on Broad; the home is on the northern side of the street midway between Sycamore and Wynn Streets. The original portion of the elegantly restored Georgian-Colonial mansion was constructed in 1757 by William Murfree. Upon his death, he left the house to his son, Hardy.

Hardy Murfree (1758–1809) served with distinction as an officer in the North Carolina Continental Line. He was singled out for his bravery and heroism in the American assault on Stony Point, a British stronghold on the Hudson River. After the war, he successfully petitioned for the incorporation of the town named for his father.

The tour ends at the Murfree House. If you desire a more extensive look at the restored town, you may arrange a tour at the nearby Roberts-Vaughan Village Center, located at 116 East Main Street.