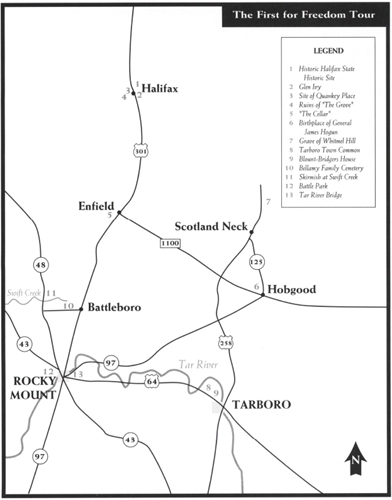

This tour begins at Halifax in Halifax County and makes its way through Edgecombe County before ending at Rocky Mount in Nash County. Among the highlights are Historic Halifax State Historic Site, Loretta (the home of William R. Davie), Glen Ivy (White Hall), the ruins of “The Grove,” “The Cellar,” Tarboro Town Common, the Blount-Bridgers House, the site of the skirmish at Swift Creek, and the place on the Tar River where Tar Heels received their name.

Total mileage:

approximately 79 miles.

This tour covers the three-county region in the northeastern part of the state that saw the birth of a free and independent North Carolina in 1776. The area was also the site of the final departure of Lord Cornwallis and the British army from the state five years later. Many of the stirring events that fostered the early spirit of independence took place here: the passage of the Halifax Resolves; the adoption of the first state constitution; and the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence in North Carolina.

The tour begins at the junction of U.S. 301 Bypass and U.S. 301 Business on the western side of Halifax, the seat of the county of the same name. Both town and county were named for George Montague, second earl of Halifax (1716–71). Montague, who served as president of the British Board of Trade and Plantation, is known as “the Father of the Colonies” for his successful efforts in developing American commerce.

Along U.S. 301 Bypass, a half-dozen state historical markers related to the Revolutionary War give a hint of the history written in the nearby village. These markers pay tribute to the Halifax Resolves, the first state constitution, the colonial Masonic lodge, and visits by Cornwallis and George Washington.

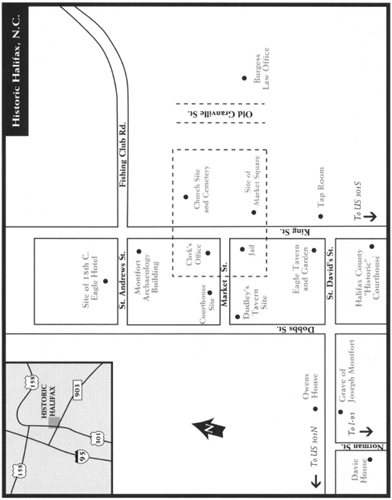

Follow U.S. 301 Bypass for 0.2 mile to where it junctions with N.C. 903 and Pittsylvania Street. Turn left onto Pittsylvania. After one block, turn left onto Norman Street. Drive a block, then turn right on St. David’s Street. The visitor center for Historic Halifax State Historic Site is just ahead at the corner of St. David’s and Dobbs Streets. Park in the lot on Dobbs and walk across the street to the visitor center.

Inside the spacious, modern center, a thirteen-minute slide show orients visitors to the story of the emergence of Halifax as a key town in colonial North Carolina. Attractive exhibits of artifacts from the Revolutionary War era are displayed in the center’s museum. A gift shop, an information center, and restrooms are also located in the facility.

There are few sites in all of what was once colonial America that are more historically significant and better preserved than Halifax, located on the banks of the Roanoke River. It was in this town on April 12, 1776, that North Carolina statesmen took the bold initiative that led the other twelve colonies toward a formal declaration of independence from Great Britain.

Founded in 1760, Halifax quickly became an important crossroads town. It was located on the main north-south route of the colonies (a portion of which is traced by King Street today) and the route leading west into the interior of North Carolina. The town was a vital river port and a trading center. Men from the west brought furs and skins to trade for imports stored in the warehouses that once stood along the river. Area planters brought their goods to town for sale or export. Because it was the seat of local government and the headquarters of the militia district, Halifax was the site of many fiery discussions of the revolutionary ideas that began to take hold in colonial America in the mid-1770s. Local taverns provided the setting where early Patriots exchanged opinions and plotted strategy.

Today, while Halifax is not as large or as popular among tourists as Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia, it is an authentic village—restored, not reconstructed. Free guided tours of Historic Halifax and its magnificently restored buildings are available throughout the day and begin at the visitor center. A map for a self-guided tour is also available at the center; however, the interiors of the sites cannot be seen on the self-guided tour.

It is best to take the self-guided tour on foot. To begin, proceed southeast on St. David’s Street from the visitor center. You will reach the Eagle Tavern and Tavern Garden at the northwestern corner of St. David’s and King Streets. A state historical marker for the tavern stands nearby. Constructed around 1790, this handsome, two-story, Federal-style structure was enlarged in 1845. It originally stood farther north on King Street at the site now occupied by Andrew Jackson Elementary School. A pre-Revolutionary War tavern preceded the Eagle at the modern school site.

Walk across King Street to the Tap Room. The small, red, gambrel-roofed building was once attached to Pope’s Hotel, a larger structure that contained nine chimneys and nineteen fireplaces. Built in 1760, the entire complex served as a tavern where political discussions, dances, and slave auctions took place.

After visiting the Tap Room, walk north along King Street to the site of Market Square. In colonial times, this was the economic center of Halifax. During the American Revolution, the public area here was given over to military activity. A barracks was constructed near the market house, and militia troops paraded and drilled on these grounds.

Behind and to the east of Market Square is the Constitution-Burgess House.

In the late 1800s, the granddaughter of Halifax Patriot Willie (pronounced Wiley) Jones referred to this structure as the “small house in which the constitution [of North Carolina] was framed.” While it is certain that North Carolina’s first constitution was framed in Halifax in 1776, subsequent historical research has indicated that it was not signed in the Constitution-Burgess House, which was built in the late 1700s at the earliest.

Named for Thomas Burgess, a local attorney who had an office here in 1821, the small Georgian-style house is simply furnished and neatly painted in blue. It was purchased and restored by the Daughters of the American Revolution (D.A.R.) in 1921 and was donated to the state in 1964.

Behind and to the south of the Constitution-Burgess House lies Magazine Springs. Used long before the American Revolution by Indians and then by colonists, this watering hole took its name from a nearby Revolutionary War factory that made ammunition and ironwork for the American cause. A military storehouse was also located here during the war.

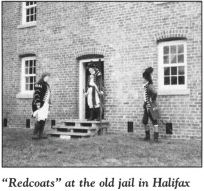

Return to the site of Market Square and cross to the other side of King Street, where the town’s jail stands. Constructed in 1838, the two-story, brick, fireproof building is on the exact site occupied by two previous wooden jails. The first, built in 1760, was destroyed when escaping prisoners set it afire. The second, erected in 1764, eventually met a similar fate. But it stood during the Revolutionary War, when it was used to house prisoners of war.

Perhaps the most famous of its wartime captives was Allan MacDonald, a Scottish Highlander taken prisoner at the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge in February 1776. (For more information on this battle, see The Cape Fear Tour, pages 89–90.) Allan was the husband of the famed Flora MacDonald, one of the most noted women of North Carolina during the Revolutionary War period. (For more on Flora MacDonald, see The Scottish Dilemma Tour, pages 114–18.)

Governor Luther Hodges dedicated the restored jail in 1955.

Remain on the same side of King Street as you walk across Market Street to the Clerk’s Office. Constructed in 1833, this brick building was designed as a fireproof place to store court and county records. This came in the wake of a holocaust in Raleigh 1831 that destroyed the Capitol and the many irreplaceable documents contained therein.

Walk along Market Street behind the Clerk’s Office to the bronze marker at the site where the original Halifax County Courthouse stood. Other than the simple marker, there is nothing on the grassy lawn to proclaim that this is the most historic spot in a town blessed with them. It was in the courthouse built here around 1760 that two of the most stirring events of the American Revolution occurred.

On Thursday, April 4, 1776, delegates from throughout North Carolina assembled in Halifax to attend the Fourth Provincial Congress. Halifax seemed the logical place for the assembly at a time when the spirit of independence was spreading throughout the colonies. In the years leading up to the Revolution, the citizens of Halifax had exhibited a strong distaste for British rule. For example, when Royal Governor William Tryon recruited eastern North Carolina volunteers to suppress the Regulators in 1771, he attracted not a single one from Halifax.

Many of the most distinguished and able statesmen of the colony assembled for the Fourth Provincial Congress: Samuel Johnston, Samuel Spencer, Richard Caswell, Thomas Person, John Ashe, Samuel Ashe, Allen Jones, Thomas Burke, Thomas Harvey, Nathaniel Rochester, Griffith Rutherford, Abner Nash, Cornelius Harnett, and Willie Jones. Virtually every one of them was filled with the revolutionary ardor that characterized Halifax at the time. After his arrival, Samuel Johnston, the presiding officer of the congress, noted that “all our people here are up for independence.” Robert Howe, who would soon take the field of battle, concurred: “Independence seems to be the word; I know not one dissenting voice.”

The congress was convened to prepare a response to a March 3 request from North Carolina’s three delegates to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Specifically, William Hooper, John Penn, and Joseph Hewes sought instructions concerning the direction that North Carolina should take in the growing rift between the colonies and Great Britain.

On April 8, the statesmen at Halifax appointed a committee composed of Cornelius Harnett, Allen Jones, Thomas Burke (who would later serve as governor of the new state), Abner Nash (who would likewise later serve as governor), and others “to take into consideration the usurpation and violences attempted and committed by the King and Parliament of Britain against America, and the further measures to be taken for frustrating the same and for the better defense of this Province.”

Four days later, the committee delivered a document that would have far-reaching consequences in American history. Harnett, the chairman of the committee, rose to his feet and in his Irish brogue presented to the delegates the bold words that would lead to a national Declaration of Independence less than three months later: “Resolved, That the delegates of this colony in the Continental Congress be empowered to concur with the delegates of the other colonies in declaring independence, and forming foreign alliances, reserving to this colony the sole and exclusive right of forming a constitution and laws for this colony.”

Working late into the night on Friday, April 12, the delegates expressed unanimous support for the report, which was known as the Halifax Resolves. Harnett’s stirring words and their enactment by the Provincial Congress represented the most revolutionary official act taken by an American colony to that date. North Carolina thus became the first colony to issue an official utterance of independence and a request that its sister colonies follow suit.

Indeed, Hooper, Penn, and Hewes were given an answer in just the terms and the tenor they desired. A copy of the Halifax Resolves was promptly dispatched to Philadelphia for the three men. But only one of their number—John Penn—was there. His two compatriots were in Virginia en route to Halifax, where they planned to take their seats in the Provincial Congress to orchestrate the move toward independence. When Hooper and Hewes rode into town on Monday, April 15, they were elated to learn of the action taken three days earlier.

The importance of these events cannot be minimized. The two dates that appear on the modern North Carolina state flag both have their roots in the American Revolution. One date (April 12, 1776) commemorates the Halifax Resolves, and the other (May 20, 1775) honors the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. (For more information on events in Mecklenburg County, see The Hornets’ Nest Tour, pages 189–92.)

The words and spirit of the Halifax Resolves were quickly heard and felt well beyond the boundaries of North Carolina. When the document was read in the Continental Congress, its revolutionary language was well received. In fact, the delegates at Philadelphia sent copies home with the request that their constituents “follow this laudable example.” On May 15, Virginia became the first colony to follow North Carolina’s lead. Less than two weeks later, the delegates from North Carolina and Virginia presented their instructions to the Continental Congress. On June 7, Richard Henry Lee moved “that these United Colonies are and of right ought to be free and independent states.”

The defiant act of the North Carolina statesmen who took a stand in Halifax bore fruit on July 4, when the Continental Congress approved the final draft of the Declaration of Independence. News that independence had been declared reached the Provincial Council (the executive branch of government in North Carolina) at Halifax on July 22. Upon receiving a copy of the Declaration, the council voted that it should be read in public for the first time in North Carolina on August 1.

It was only logical that the place chosen for the momentous event should be the lawn of the courthouse where the first seeds for the Declaration had been sown only months earlier. There was also no question as to the statesman who should offer the state’s first public proclamation of the Declaration. Cornelius Harnett, the fearless Cape Fear Patriot who had inspired his colleagues to adopt the Halifax Resolves, was the man accorded the honor.

At high noon on August 1, 1776, the Provincial Council marched to the courthouse amidst an immense gathering of people. Drums reverberated; flags fluttered in the soft summer breeze; and soldiers, dressed in the best uniforms they could find, stood at attention. Suddenly, the crowd roared with delight as a militia detail escorted Harnett to a platform. When the fifty-three-year-old hero mounted the rostrum with the scrolled Declaration clutched in his hand, a hush descended upon the excited multitude. His Irish voice was clear and loud as he began to read the historic words: “When in the Course of human Events …” No sooner had he finished the proclamation than an exuberant celebration began. At its height, the jubilant soldiers near Harnett grabbed the staid gentleman, put him on their shoulders, and paraded him through the streets of Halifax as the champion of American independence.

Return to the Clerk’s Office, then cross King Street to the colonial cemetery. From 1793 to 1911, this was also the site of the village church. The oldest known grave in the cedar-shaded graveyard dates to 1766. Among the notable persons buried here are two women of the Revolutionary War era.

Justina Davis (1745–71) was laid to rest here at the age of twenty-six. In her short life, she married two men who served as governors of North Carolina. Her first husband was Royal Governor Arthur Dobbs, who married her when he was seventy-eight and she fifteen. (For more information about Dobbs, see The Cape Fear Tour, page 101.) After Dobbs died, his widow married Abner Nash. Nash was elected governor after Justina died.

Also located in the cemetery is the grave of Sarah Jones Davie. Throughout her life, she was surrounded by heroes of the American Revolution. She was the daughter of Allen Jones, the niece of Willie Jones, and the wife of William Richardson Davie.

Adjacent to the cemetery is the Joseph Montfort Amphitheater. This outdoor theater is the venue for the summer drama First for Freedom. Written by Maxville Burt Williams, the play has been presented every summer since it premiered in 1976. It dramatizes the events of 1776 that culminated in the Halifax Resolves.

Resume your walk on King Street, continuing about three and a half blocks to the river overlook; the pavement ends en route to the overlook. Vast warehouses and other commercial structures of the eighteenth century once stood at this serene site on the forested banks of the Roanoke River. As Cornwallis was moving his army north toward Virginia in May 1781, he was forced to tarry in Halifax because floodwaters along the river here delayed his crossing. A river ferry operated at Halifax into the twentieth century.

From the river overlook, retrace your route on King Street; follow King to St. Andrews Street. Andrew Jackson Elementary School stands on the northwestern corner of this intersection. In Revolutionary War times, the Eagle Hotel and the Eagle Tavern were located here. It was at this site that North Carolina’s first state constitution was drafted and adopted by the Fifth (and final) Provincial Congress, convened in late 1776. On December 19, two days after the constitution was approved, the representatives at Halifax elected Richard Caswell the first governor of the independent state of North Carolina.

Almost five years later, Cornwallis came calling. The British general quartered Colonel Banastre Tarleton and other officers at the Eagle Hotel. A decade later, President George Washington visited Halifax on his famous Southern tour. During his stay on April 16 and 17, 1791, he was feted at a ball at the Eagle Hotel. Halifax was the first North Carolina town visited by Washington after he crossed the Virginia line. “It seems to be in a decline & does not it is said contain a thousand Souls,” the president wrote of Halifax.

On February 27, 1825, the Marquis de Lafayette was entertained at the Eagle Tavern during his one-night stay in Halifax. While enjoying his triumphant visit, the aged French general recalled that it was at Halifax where Cornwallis had made his final decision to leave North Carolina for Virginia. Addressing the local citizenry, Lafayette remarked, “It has long been my desire to visit the citizens of Halifax, where the Constitution of the State was framed and the principles of liberty declared.” In response to the welcome he received from Major Allen J. Davie, the son of General William R. Davie (who had died five years earlier), Lafayette told the crowd, “The regard and the respect evinced toward me by the citizens are highly gratifying to my feelings, and they are rendered more so by being tendered to me by the son of my old and esteemed friend.”

Proceed to the Montfort Archaeology Building, located on King Street near its intersection with St. Andrews. Constructed in 1984, the large, white, two-story structure stands on what was Lot 52 in the original town plan of Halifax. Inside the building are artifacts, exhibits, and the archaeological remains of the town house of Joseph Montfort.

Although Montfort died on March 25, 1776, three weeks before the Halifax Resolves, he exhibited during his life the revolutionary spirit synonymous with his hometown. A regular figure at colonial assemblies until his health began to deteriorate in 1775, Montfort was intensely disliked by Royal Governors Tryon and Martin. In a scathing attack on Montfort, Governor Martin once wrote, “He is well received by all, esteemed by very few, and considered a Problem by everybody.”

Two of his daughters married Revolutionary War leaders of North Carolina; Mary Montfort wed Willie Jones, and Elizabeth Montfort married John Baptiste Ashe.

Montfort’s greatest claim to fame was his high office in Masonic activities, which will be detailed later in this tour.

Return to the intersection of King and St. Andrews. Turn left and walk west on St. Andrews past the school to Dobbs Street. Turn left on Dobbs and proceed south toward the visitor center.

This quiet, peaceful street gives little hint of the tempestuous events that gripped Halifax more than two centuries ago. Living in and around the village were dozens of lesser-known individuals who had an impact on the struggle for American independence. For example, there were the Pasteurs. Believed to have been brothers, Charles, Thomas, and William Pasteur were descendants of Huguenot immigrants. Thomas served as an officer in the North Carolina Continental Line. William was a surgeon for North Carolina troops and played a vital role in obtaining medicines and supplies for soldiers from his adopted state. Charles, likewise a surgeon and apothecary, furnished state troops with medical supplies.

And then there was Thomas Gilchrist (1735–89), a man best remembered for presenting a future Revolutionary War hero with his first case as an attorney. The young lawyer so engaged was Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence. During the war, Gilchrist was suspected of treason. His name was subsequently cleared through a petition filed by his wife, Martha, the sister of Willie and Allen Jones.

Stop at the southeastern corner of Dobbs and Market Streets. The tavern of Christopher Dudley stood here on the eve of the Revolution. The mulberry trees growing at its site are more than two hundred years old. They are the remains of an ill-fated attempt to begin a silkworm industry in eighteenth-century Halifax. One significant problem doomed the industry to failure: the trees were of the wrong variety.

Continue south on Dobbs Street. Take notice of the garden at the rear of the visitor center. Its walkways follow the design of a garden shown on the map of the town prepared by C. J. Sauthier in 1769. The plantings here include flora of significance to the colonial and Revolutionary War periods.

At the junction of Dobbs and St. David’s Streets, turn right and walk past the visitor center parking lot to the Owens House. A typical eighteenth-century English town house, the handsome gambrel-roofed structure was constructed in 1760 and moved to its present site before 1807. Decorated with furnishings from colonial times and the days of early statehood, the Owens House is the last building open to the public on this tour of Halifax.

Located directly across St. David’s Street is the Royal White Hart Masonic Lodge. Constructed in 1769, the two-story white frame building is the oldest Masonic temple built for that purpose that is still in use in the United States.

On the front lawn, enclosed in an iron fence, is the grave of Joseph Montfort. A bronze tablet on the fence gate bears a warning: “This gate swings only by order of the Worshipful Master of Royal White Hart Lodge to admit a Pilgrim Mason.”

Inside the fence, an elaborate marble slab pays tribute to Montfort, whose body was originally interred at the colonial cemetery. It notes that he was an orator, statesman, Patriot, and soldier. Montfort served as the first clerk of court of Halifax County, as treasurer of the province of North Carolina, as a colonel of colonial troops, and as a member of the Provincial Congress.

The slab proclaims that Montfort was appointed “Provincial Grand Master of and for America” on January 14, 1771. As such, he stands as the highest Masonic official ever on the continent. In bold letters, the grave marker boasts that Montfort was “THE FIRST—THE LAST—THE ONLY GRAND MASTER OF AMERICA.”

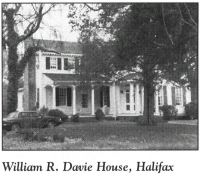

Continue on St. David’s Street to Norman Street. On the southwestern corner, a state historical marker and a D.A.R. marker pay tribute to William Richardson Davie (1756–1820). His former home, privately owned, stands on Norman Street just beyond the markers.

Without question, William Richardson Davie was one of the most remarkable of the many Revolutionary War heroes of North Carolina. Born in England, he moved to America with his Scottish parents in 1764. Davie graduated from the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University) in 1776, just as the war was beginning. He served throughout the conflict as a Patriot officer.

After the war, Davie settled in Halifax to practice law. He married Sarah Jones, the daughter of Allen Jones, and assumed a leading role in the political and social affairs of the area.

Davie was but thirty-three years old when he was elected a delegate to the Constitutional Convention at Philadelphia in 1787. In the heated debates that characterized the convention before the Constitution was presented for consideration, the small, lightly populated states maintained that every state should have the same number of senators, while the larger states contended that the number of representatives in both houses of Congress must be based on population.

When a vote was taken, the result revealed a tie. Confusion was the order of the day. Both sides were intransigent. Gloom prevailed, as it appeared that the convention was about to collapse.

Suddenly, one of North Carolina’s five delegates rose to his feet and began to address the assembly of distinguished Americans. In an emotional speech, William Richardson Davie saved the Constitution for the new nation when he proclaimed, “North Carolina is one of the largest states who voted against the plan suggested by the smaller states, but the time has now come when the larger states ought to yield. I am ready, and I believe my colleagues are ready, to vote that each state should have the same number of members in the Senate.” Davie’s historic oration brought the house down. A new vote was taken, and the North Carolinian’s forceful words carried the day.

Back home, Davie worked tirelessly—and successfully—for ratification despite strong opposition from his wife’s uncle, Willie Jones.

Elected governor of North Carolina in 1798, Davie was subsequently appointed as a special envoy to France by President John Adams. When he was introduced to Napoleon as “General Davie,” the emperor sneered in derision. In an audible aside, Napoleon said, “Oui, General de Melish,” the implication being that officers of the militia were of a lesser quality than regular-army officers. But through his intelligence and charm—and his ability to speak French fluently—the North Carolinian soon won the emperor’s admiration and respect.

Loretta, Davie’s home in Halifax, was constructed in 1787. The tall, well-preserved, two-story frame dwelling retains much of its original interior craftsmanship.

From the junction of St. David’s and Norman, turn around and walk east on St. David’s to King Street. Turn right and walk one block south on King to the former Halifax County Courthouse. This stately, three-story, tan-brick Neoclassical Revival structure was built in 1909. On its first floor are three items related to the Revolutionary War: a bronze plaque listing the Revolutionary War soldiers from Halifax County; a framed copy of the Halifax Resolves; and a reproduction of an artist’s rendition of the signing of the Resolves.

Retrace your route to the parking lot at the visitor center. This ends the walking tour. Return to your car and drive to the junction of St. David’s Street and King Street/Main Street. Turn right and follow Main Street (U.S. 301 Business) as it makes its way through modern downtown Halifax; just after the turn, you’ll notice the large seal on the former Halifax County Courthouse commemorating the Halifax Resolves.

Approximately 0.5 mile south of the courthouse, as U.S. 301 Business winds gracefully among stately homes, you’ll pass a private home on the right known as Glen Ivy (White Hall). This handsome frame dwelling, built in the 1840s, bears the name of the earlier estate of Revolutionary War leader John Baptist Ashe and his wife, Elizabeth, who was the daughter of Joseph Montfort and the sister of Mrs. Willie Jones. The couple are believed to be buried in unmarked graves near here.

While her husband was away fighting for the American cause (see The Cape Fear Tour, page 102), Mrs. Ashe showed herself a heroine, as did the wives of other local Patriot leaders.

When Cornwallis’s army headed for Halifax on its march northward in the spring of 1781, only a small band of militiamen was available to defend the town. Colonel Banastre Tarleton led advance units of the British army against the local militia in a skirmish below the town. After routing the hapless Americans, Tarleton altered his route toward Halifax upon the receipt of intelligence that a large force of militia had gathered there. Striking from the west instead of the south, Tarleton’s horsemen quickly cleared Halifax of American soldiers by chasing them across the river.

Writing in her diary in 1862 in the house that stands at the current tour stop, Mary Conigland remarked on the conflict from the previous century, noting that “even this spot on which I write has felt the weight of British bullets. The kitchen we now use was made of timbers taken from [the earlier] house in this lot, and in several places [is] perforated with British balls.”

For several days while awaiting the arrival of Cornwallis and the main body of the British army, Tarleton’s soldiers subjected Mrs. Ashe and the other citizens of Halifax to outrages. They appropriated cows, chickens, pigs, and other animals for food and destroyed what they could not eat. But even the much-feared Tarleton was no match for the defiant Elizabeth Jones Ashe.

During the British occupation, Major General Alexander Leslie made Glen Ivy (White Hall) his headquarters. On one occasion, Tarleton called at the house. In the course of a conversation with some fellow officers, he began to berate his archrival in the American army, Colonel William Washington. Four months earlier, Washington had bested—and personally wounded—Tarleton at the Battle of Cowpens. Tarleton considered Washington a boor, a pest, and a nemesis. In a sarcastic tone, he proclaimed that he “would be happy to see Colonel Washington,” because he understood that the American was small and ugly.

Upon overhearing the conversation, Mrs. Ashe remarked, “If you had looked behind you, Colonel Tarleton, at the Battle of Cowpens, you would have enjoyed that pleasure.”

The British officer reached to draw his sword just as General Leslie entered the room. The general asked Mrs. Ashe to explain the situation. When she did so, Leslie remarked with a smile, “Say what you please, Mrs. Ashe, Colonel Tarleton knows better than to insult a lady in my presence.”

From Glen Ivy (White Hall) continue south on U.S. 301 Business for 0.3 mile to U.S. 301 Bypass. At this intersection, state historical markers calling attention to the Halifax Resolves and Washington’s visit to Halifax stand in a parklike plaza. Also located here is a D.A.R. boulder with a bronze plaque memorializing the Halifax Resolves.

Drive across U.S. 301 Bypass onto Quankey Avenue, a short, narrow lane that curves sharply to the south. Park where the pavement ends.

This short street bears the name of the nearby creek where most of Cornwallis’s soldiers camped during their stay here. The name also preserved the memory of a plantation that stood in the vicinity during Revolutionary War times. Quankey Place was the plantation of Colonel Nicholas Long (1728–98), who represented Halifax County in the First, Second, and Third Provincial Congresses. After that, Long turned his attention to the military affairs of North Carolina. In May 1776, the Continental Congress appointed him deputy quartermaster under General George Washington.

Leave your vehicle and walk across the railroad tracks, taking care to watch for the speeding Amtrak trains that pass by here on their north-south route. Walk several hundred yards in the field on the western side of the tracks. To the right in a clearing shaded by cedars is a single marked grave in an ancient cemetery. Buried here is Mary Montfort Jones, the three-year-old daughter of Willie and Mary Jones.

Just south of the cemetery in a forested thicket are the remnants of “The Grove,” the magnificent plantation house of Willie Jones (1741–1801). Now owned by the state, the three-acre site contains the crumbling chimney and foundation bricks from the two-story house that was once an eastern North Carolina showplace. A cluster of massive oak trees that once surrounded the mansion gave their name to the structure. State officials have given consideration to rebuilding the house, but the cost of such a project has proven prohibitive.

More important than the house itself were the people who lived in it during the American Revolution. Willie Jones was one of the greatest Patriots of his day. Born into an aristocratic family, he was educated at Eton College in England after spending his youth in Northampton County, located on the Virginia border just north of Halifax County. Upon his return to North Carolina, he built “The Grove” with timbers from his family’s old home, many of which had been transported from England.

Upon the departure of Royal Governor William Tryon from North Carolina in 1771, Willie Jones’s allegiance began to shift to the American cause. He was subsequently elected to all five Provincial Congresses, where he established himself as a champion of democracy and states’ rights. When the Fifth Provincial Congress convened in 1776, Jones was appointed to the committee that was to draft the first state constitution. Historians believe he was the chief author of the document.

Throughout the war, Jones served in the general assembly and was one of the leading statesmen in North Carolina. He then went on to serve one term in the Continental Congress. Jones was opposed to the Constitution in its original form because it lacked a bill of rights. He noted his opposition thus: “For my part, I would rather be eighteen years out of the Union than adopt it in its present defective form.”

A long-enduring but oft-challenged tradition in North Carolina maintains that America’s first naval hero received his last name from Willie Jones. According to the legend, a young Scottish sailor made his way to Halifax in 1775 after a checkered career at sea. Known at the time as John Paul, he made the acquaintance of Willie Jones, who befriended him and opened his home. Greatly impressed with his guest, Willie Jones recommended to Joseph Hewes that the young man be given a commission in the Continental Navy, to which Hewes agreed. When the time came for the young lieutenant to go to sea to fight for American independence, he served under the name John Paul Jones. As the story goes, he selected his new name to express his gratitude to Willie Jones. The newly christened John Paul Jones then proceeded to sail into history. His famous war cry—“I have not yet begun to fight”—remains one of the most famous statements of the Revolutionary War.

An avid sportsman, Willie Jones built a racetrack near his home. The estate acquired a reputation as a social center and a place of hospitality. In addition to the famous naval hero, “The Grove” hosted many other notables, among them George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette.

Among the less welcome guests were Cornwallis and Tarleton, who were “entertained” at the plantation during their stay in Halifax. Mrs. Willie Jones, the daughter of Joseph Montfort, could not refrain from baiting Tarleton. The feisty cavalry leader, still smarting from a severe slash on his hand inflicted by Colonel William Washington at Cowpens, used the occasion to once again demean his hated adversary. After listening to Tarleton describe Washington as an illiterate fellow who could hardly write his name, Mrs. Jones retorted, “Colonel, you ought to know better, for you bear on your person proof that he knows very well how to make his mark.” Tarleton’s response was not recorded.

Return to the junction of Quankey Avenue and U.S. 301 Bypass. If you care to see the state historical markers commemorating several sites and events already covered on this tour (the Masonic lodge, Cornwallis’s visit, the creation of the state constitution), turn left and proceed north. Otherwise, turn right, leave Halifax via U.S. 301, and proceed south for 11.9 miles to Enfield.

This venerable town served as the county seat of Edgecombe County from 1745 until 1759, when Halifax County was established. Although few tangible reminders of Enfield’s long history survive today, two state historical markers on McDaniel Street (U.S. 301) honor significant sites.

One marker notes that the town was the site of the famous Enfield Riot, which took place on May 14, 1759. Some historians consider this incident the forerunner of the Regulator movement and the spark that ignited the drive for independence. Dissatisfaction among area citizens over illegal fees, corruption, and excessive taxes reached a boiling point that day. When some of the citizens behaved “riotously,” Royal Governor Arthur Dobbs had several of their number jailed. Their friends and neighbors, further angered by the imprisonment, broke into the jail and released the protestors.

The second marker, located at the corner of McDaniel and East Franklin Streets, honors John Branch, Jr., a distinguished American statesman. To reach his family’s historic home, continue south on U.S. 301 for one block to N.C. 481. Turn right on N.C. 481 and follow it through downtown Enfield, where it becomes Whitfield Street. Continue four blocks on Whitfield.

Located at 404 Whitfield, “The Cellar,” as the beautifully restored, two-story home has long been known, was constructed around 1800 by John Branch, Sr., a wealthy landowner, sheriff, and local hero. The elder Branch won celebrity during the Revolutionary War because of his ability to identify and round up Tories. When he died, he left the home to his son Joseph, who had served the American cause as a major of the militia.

When his tour of North Carolina brought him to Enfield in 1825, Lafayette was the guest of Joseph Branch at “The Cellar” and addressed the local citizens from the balcony.

Retrace your route to the intersection with U.S. 301. Proceed east across the intersection onto S.R. 1003 and follow it for 4.3 miles to S.R. 1100. Turn right, drive 12 miles to N.C. 125, turn right again, and proceed 2.4 miles south to the state historical marker for James Hogun, one of North Carolina’s lesser-known Revolutionary War heroes. His home stood sixty yards east of the marker.

When tensions began to heighten between the American colonies and Great Britain, Hogun emerged as a political and military leader. As commander of the Seventh North Carolina Continental Line, he joined General Washington in July 1777 during the campaign in the North. At the Battle of Germantown, Hogun was cited for “distinguished intrepidity.”

In December 1778, Hogun and his command were assigned to Philadelphia at the request of Major General Benedict Arnold, the commander of the city. Early the next year, North Carolina was authorized by the Continental Congress to name two brigadier generals. Hogun and Jethro Sumner were selected. (For more information about Sumner, see The Statehood Tour, pages 444–45.) These two men joined Robert Howe, Francis Nash, and James Moore as the only men from North Carolina to serve as generals in the Continental Army.

Soon after his promotion, Hogun succeeded Arnold as commandant of Philadelphia. In November 1779, he was forced to relinquish that post when he was called to reinforce the beleaguered Continental forces at Charleston, South Carolina. When General Benjamin Lincoln surrendered the port city to the British on May 12, 1780, Hogun was incarcerated at Haddrel’s Point near Sullivan’s Island. (For more information on General Lincoln, see The Tide Turns Tour, page 270.)

During his confinement, Hogun was offered a parole by British authorities, but he refused, choosing instead to remain in prison with his half-starved soldiers. For the remaining six months of his life, the general attempted to lift morale and maintain discipline. While enduring the same hardships as his men, he fell ill. Hogun died on January 4, 1781, and was buried in an unmarked grave.

Turn around near the historical marker and proceed north for 6 miles on N.C. 125 to its merger with U.S. 258. Go north on U.S. 258 as it passes through Scotland Neck. After 2 miles, you’ll notice a state historical marker for Whitmel Hill. To visit the grave of this Revolutionary War leader, park at Old Trinity Episcopal Church, located adjacent to the marker.

Hill (1743–97) was laid to rest in this expansive, gardenlike church cemetery after a life of distinguished service to North Carolina and America. Born into a wealthy family in nearby Bertie County, he received an excellent education, graduating from the University of Pennsylvania.

Devoted to the American cause from the outset of the Revolutionary War, Hill, like many of his compatriots, divided his time between military duties and legislative service. His patriotic activities were a source of great irritation to area Loyalists. As a result, Hill lived under the threat of assassination during the summer of 1777. His timely discovery of a Tory plot to kill the leaders of the Revolution in North Carolina enabled Governor Richard Caswell to foil the plan and arrest the desperate Loyalists.

Hill began a three-year stint in the Continental Congress in 1778. An avid horseman, he was proud of both his skill as a rider and the speedy animals he owned. In an April 1779 letter to Thomas Burke, his fellow North Carolina congressman and roommate in Philadelphia, Hill boasted that he had made the 350-mile journey home in seven and a half days, “a ride scarcely performed before in so short a time.”

From the church, drive south on U.S. 258. After approximately 9 miles, you will enter Edgecombe County. Continue south on U.S. 258 for 10.8 miles to U.S. 64 at Princeville. Turn right and follow U.S. 64 Business/N.C. 33 for 1.5 miles to Tarboro, the seat of Edgecombe County. Upon reaching the town, U.S. 64 Business/N.C. 33 becomes Main Street.

Among the several historical markers on Main Street related to the Revolution is one that calls attention to the Tarboro Town Common, a sixteen-acre, multiblock public green bounded by Albemarle Avenue, Wilson Street, Park Avenue, and Panola Street. Park nearby and walk to this historic area.

Created by the same legislative act that established Tarboro in 1760, the common covers three tree-shaded blocks. More than two centuries later, the well-maintained grounds lend beauty and a feeling of spaciousness to the town that has grown up around them. Located on Tarboro Town Common is a pin oak brought from George Washington’s home at Mount Vernon. It was planted here by the D.A.R. in 1925 as a memorial to the president’s visit to Tarboro on April 18, 1791.

A nearby state historical marker commemorates the night Washington spent in town. “This place,” the great man recorded in his diary on the subject of Tarboro, “is less than Halifax, but more lively and thriving;—it is situated on Tar River which goes into Pamplico Sound and is crossed at the Town by a means of a bridge a great height from the water. We were recd, at this place by as good a salute as could be given by one piece of artillery.”

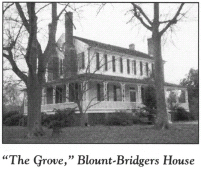

From the Tarboro Town Common, walk two blocks north on Main Street to Bridgers Street and turn right. Located at 130 Bridgers is the Blount-Bridgers House, also known as “The Grove.” Restored to its original elegance in recent years, the two-story frame mansion was constructed in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century for Thomas Blount.

Blount (1759–1812) was a member of a famous eastern North Carolina family that produced seven sons who distinguished themselves in the Revolutionary War era. His brother William (see The Albemarle Tour, page 23) was one of the North Carolinians who signed the Constitution. Like his brother Reading (see The Coastal Rivers Tour, page 62), Thomas Blount served in the fight for American independence. While a lieutenant in the Fifth North Carolina Regiment, he was captured and imprisoned in England.

Following the war, the state appointed him major general of the militia. With the return to peace, Blount resumed his participation in the lucrative family mercantile and shipping enterprise, based in Washington, North Carolina. The Blounts’ business, one of the largest in the state, brought Thomas in contact with one of his former comrades in arms, General Jethro Sumner. In 1796, Sumner’s daughter, Jackie Mary, became Blount’s wife.

Blount gave much of his postwar life to the establishment of the new state and nation. In 1793, he began the first of his six terms in the United States Congress.

Now owned by the town of Tarboro, the Blount-Bridgers House is open to the public. There is no admission charge.

Return to the junction of Bridgers and Main. Turn left and walk seven blocks to St. James Street in downtown Tarboro. A state historical marker here directs visitors to the grave of W. L. Saunders, located four blocks east in the cemetery of historic Calvary Episcopal Church. Turn left on St. James and walk to the cemetery, which covers the yard around the magnificent brick church.

More than a century after his death, William Laurence Saunders (1835–91) remains the most celebrated historian on the subject of colonial North Carolina. A Confederate officer, Saunders served as North Carolina’s secretary of state from 1879 until 1892. In 1879, he came across a cache of colonial records in the old arsenal on Capitol Square. This discovery led him on a quest to locate, preserve, and put into book form the colonial records of North Carolina.

Saunders’s tireless efforts resulted in the publication of a ten-volume set, Colonial Records of North Carolina. Containing 10, 982 pages of material and documents covering the period from 1622 to 1776, the massive project was completed in 1890. It has been estimated that Saunders, as editor of the series, has been cited in more footnotes than any other North Carolinian. His tombstone in the Tarboro churchyard reads, in part, “For twenty years he exerted more power in North Carolina than any other man.”

Following Saunders’s death, another Confederate veteran, Judge Walter Clark, continued the project by compiling the sixteen-volume State Records of North Carolina, which covers the Revolutionary War period through 1790.

Also buried in the churchyard is Mary Sumner Blount, the daughter of General Jethro Sumner and the wife of Lieutenant Thomas Blount.

Return to Main Street. Turn left on Main and go one block to Pitt Street. The commercial building at the southeastern corner of this intersection contains a plaque memorializing George Washington’s visit to Tarboro.

Return to your vehicle and proceed north on U.S. 64 Business/N.C. 33. After approximately 7.3 miles, turn right onto S.R. 1252, then drive 4.1 miles north to S.R. 1407. Turn right, proceed 0.8 mile, and turn left on S.R. 1409. Travel north for 1.7 miles to S.R. 1428. Near this junction stood Mount Prospect, a traditional two-story farmhouse that was the home of Exum Lewis, a Revolutionary War soldier. George Washington stopped at Lewis’s home in 1791.

Return to the junction with S.R. 1407. Turn right and proceed north for 7.5 miles to Battleboro, located just across the line in Nash County. Established in 1777, the county was named for General Francis Nash, a North Carolina hero killed at the Battle of Germantown. (For more information on Nash, see The Regulator Tour, pages 415–16.)

In Battleboro, S.R. 1407 becomes West Main Street. Follow West Main to U.S. 301 and turn left. After 0.6 mile, you will reach 1-95 Business/N.C. 4. Turn right and proceed 0.8 mile to the Bellamy family cemetery, located on the northern side of the highway five hundred feet north of the Bellamy House, which dates from around 1820.

Inside the walled cemetery is the grave of Lieutenant Colonel John Clinch, Jr., an officer in the North Carolina Continental Line. Near the end of the war, Clinch married a daughter of Duncan Lamon, whose bridge is the focus of a stop later in this tour. Clinch’s gravestone bears a bronze marker provided by the Sons of the American Revolution.

Continue west on 1-95 Business/N.C. 4 for 1.8 miles to N.C. 48. Turn right on N.C. 48 and proceed north for 0.7 mile to the state historical marker for the skirmish at Swift Creek.

At a site several miles west of the marker, Patriot militiamen made a feeble attempt to battle Cornwallis’s troops on May 7, 1781, as the British army continued its march north. Untrained and poorly armed, the American forces were no match for Tarleton’s dragoons. After suffering a rout at Swift Creek, the Patriots fell back 5 miles north to Fishing Creek, where once again they were swept aside by the experienced British horse soldiers. As Tarleton noted in his journal, “The Americans at Swift creek, and afterwards at Fishing creek, attempted to stop the progress of the advanced guard, but their efforts were baffled, and they were dispenced with some loss.”

Turn around near the historical marker and drive south on N.C. 48 for 0.9 mile to Halifax Road (S.R. 1527). Turn right and drive south for 3.9 miles through the town of Dortches to the bridge over Stony Creek.

After he crossed the Tar River in southern Nash County, Cornwallis marched his army north along Halifax Road. When he encountered the waters of Stony Creek, the general decided to camp the army near Hunter’s Mill. Grain to feed the British soldiers was ground at the mill. A large, round, bowl-shaped rock can still be found in Stony Creek. Local legend holds that the rock, known as “the Cornwallis Horse Trough,” is so named because Cornwallis fed his horse from it.

While Cornwallis was camped here, Robert Beard, a local Tory and a deserter from the American army, met with the British commander. Pursuant to a proclamation by Governor Richard Caswell, Beard was considered an outlaw. As a result of his meeting with Cornwallis, Beard was commissioned as a captain and given the authority to recruit a band of Tories for the British army. Cornwallis also promised Beard a reward of ten guineas for each man active in the American cause whom he could capture.

A bottle of aged brandy proved to be Beard’s undoing. Emboldened by Cornwallis’s confidence in him, he led a Tory uprising in Nash County, collected a band of twenty followers, and set out for the home of James Drake on Sandy Creek in the northwestern part of the county. The fifty-four-year-old Drake was a strong Patriot who had earlier ordered Beard to stay away from his home and family. Drake’s son, Brittain, was a captain of the local Light Horse Company.

Upon Beard’s arrival at the Drake home, a gunfight ensued between the small army of twenty Tories and the two Drake men. Two neighbors who had been visiting the Drakes made their escape to get help. The unfortunate Drakes were wounded and taken prisoner.

In the meantime, Mrs. Drake had prepared some food and brought forth a jug of seventeen-year-old brandy. She invited Beard and his men to refresh themselves before leaving with her captive husband and son. It was her fervent hope that this ploy would buy time for Patriot reinforcements to arrive.

Once the brandy gave out, Beard ordered his men to prepare to leave with the prisoners. In the nick of time, seventy soldiers of the Light Horse Company came riding up. Beard was knocked off his horse and arrested. He was subsequently tried and executed as a traitor.

When you are ready to resume the tour, turn around and proceed north on Halifax Road for 0.1 mile to Hunter Hill Road (S.R. 1604). Turn right and drive east toward Rocky Mount. This street is named for Thomas Hunter (1735–84), a local Patriot who served as a militia officer and as a delegate in the First Provincial Congress. Hunter participated in the skirmish at Swift Creek. His home stood nearby.

Follow Hunter Hill Road for 3.7 miles to N.C. 43/N.C. 48. Turn left, drive 0.2 mile to Battle Park, and turn left on Battle Park Lane.

This municipal park provides a splendid view of the scenic Tar River. A state historical marker and a D.A.R. marker for Donaldson’s Tavern are located near the river bridge adjacent to the park. During his tour of North Carolina in February 1825, Lafayette stayed overnight at the tavern, which stood near the marker.

From the park, cross the Tar River via N.C. 43/N.C. 48 and drive south for 1.1 miles to U.S. 301 Business. Turn left on U.S. 301 Business (also known as Hardee Boulevard, for the fast-food chain born here) and go 0.6 mile north to the Tar River bridge. For a good view of the bridge and the river, turn into the parking lot of Rocky Mount’s animal shelter, located on the right side of the highway. The tour ends here.

According to some, it was at this river crossing that North Carolinians received the nickname “Tar Heels.”

For much of the colonial period, North Carolina led the world in the production and export of naval stores. When Nash County residents learned that Cornwallis’s army was making its way toward the county in May 1781, they decided that it would be better to destroy all the naval stores on hand rather than allow them to fall into enemy hands. In advance of the invading army, the tar and pitch were brought to the river and dumped into the dark waters.

When the British soldiers reached the crossing, they pulled off their shoes and stockings, rolled up their breeches, and forded the river. In the process, they stepped into the tar, which greatly impeded their progress. Upon their arrival in Virginia several weeks later, the Redcoats were said to still have a healthy coating of tar on their feet. When someone asked about this, the embarrassed soldiers told of their ordeal in North Carolina. They issued a warning that the rivers down there “flowed tar,” and that any one who forded one would get tar on his heels. And so the state’s residents got their famous name.