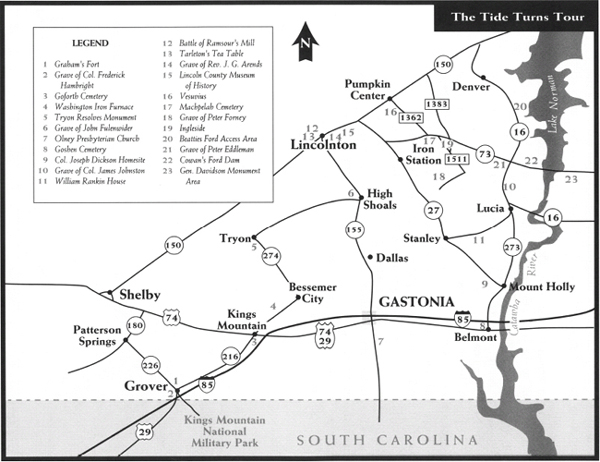

This tour begins at Patterson Springs in Cleve, land County and makes its way through Gaston County before ending at Cowan’s Ford on the Lincoln County-Mecklenburg County line. Among the high, lights are the story of Graham’s Fort, the grave of Frederick Hambright, the Battle of Kings Mountain, the Henry Howser House, the story of the Tryon Resolves, the grave of JohnFulenwider, the Battle of Ramsour’s Mill, Machpelah Cemetery, the grave of Peter Forney, the story of Jacob Forney, the grave of Peter Eddleman, and the Battle of Cowan’s Ford.

Total mileage:

approximately 167 miles.

This tour traverses a three-county area in the southwestern Piedmont of North Carolina and dips into the northern portion of two adjacent South Carolina counties. In a seven-month period from mid-1780 to early 1781, three crucial Revolutionary War battles occurred within this relatively small geographical area.

In this land of gently rolling hills punctuated by a few peaks, the tide of the Revolution began to turn in favor of the American colonies with the Patriot victories at Ramsour’s Mill and Kings Mountain in the summer and fall of 1780. Then, in January 1781, Cornwallis moved in with his full army to begin his pursuit of Major General Nathanael Greene, which ultimately brought ruin to the British war effort.

The tour begins at the junction of N.C. 226 and N.C. 180 in the community of Patterson Springs in southern Cleveland County, which takes its name from Revolutionary War hero Benjamin Cleveland.

Follow N.C. 226 south for 6.1 miles to the site of Graham’s Fort, located on a knoll on the right side of the road three hundred yards northeast of the state historical marker near Buffalo Creek. The fort stood on a site now occupied by a late-eighteenth-century house incorporated into—and disguised by—a private home that has a modern appearance.

Experienced in building forts for the protection of settlers along the frontier of western North and South Carolina, Colonel William Graham constructed a large log cabin here that became known as Graham’s Fort during the Revolutionary War. Graham was an outspoken advocate of American independence. As a delegate to the Fifth Provincial Congress, he took part in the deliberations that produced North Carolina’s first state constitution. As a militia officer, he fought courageously in both Carolinas, participating in the important victories at Moores Creek and Ramsour’s Mill.

As summer was about to give way to fall in 1780, Graham was a wanted man among local Tories. A band of marauders came calling at Graham’s Fort that September. The events that unfolded here that day constitute one of the most dramatic, if unheralded, stories of the American Revolution in western North Carolina.

Congregated inside the fort were many people, most of them young, old, or otherwise unable to take up arms to defend against the twenty-three soldiers in the Tory band. Colonel Graham had only David Dickey and nineteen-year-old William Twitty to help him defend the place.

When the Tories sought to enter the cabin, Graham adamantly refused. To force the issue, they opened fire. After each volley, a demand for capitulation could be heard: “Damn you, won’t you surrender now?”

Graham was unyielding, and the attack continued, without much effect. Finally, John Burke, one of the more brazen Tories, decided to take matters into his own hands. He left ranks and raced up to the cabin, where he aimed his musket through a crack at young William Twitty. Just as Burke was about to squeeze the trigger, Twitty’s seventeen-year-old sister, Susan, pulled her brother to safety. Burke’s musket ball missed its target and penetrated the opposite wall of the cabin.

Susan then observed that Burke was on his knees, reloading in anticipation of firing into the cabin again. She cried out, “Brother William, now’s your chance—shoot the rascal!” In an instant, the young Patriot sent a ball that crashed into Burke’s head.

As soon as the Tory fell, Susan unbolted the door, ran out into the open, and grabbed Burke’s gun and ammunition. Stunned by the teenager’s bravery, the Tories momentarily held their fire. But as she headed back toward the door, their guns blazed again. Safely inside, Susan put the captured weapon to use, taking shots at the Tories.

At length, the standoff ended when the attackers left, having suffered four casualties. Fearing another attack, Graham sent his pregnant wife and the others at the fort to a safer location.

Soon thereafter, his fears were realized when Tories plundered the unde-fended fort.

Less than a month later, Graham was with his command—the South Fork Boys—at the base of Kings Mountain when a courier brought news that his wife was in a “precarious condition” and needed him at once. Torn between his desire to take part in the impending battle and his family responsibilities, Graham chose the latter. He asked Colonel William Campbell for permission to leave.

Reluctant to grant the request, Campbell asked Major William Chronicle, one of Graham’s subordinates, “Ought Colonel Graham to have leave of absence?”

Chronicle, who would die leading the men from what are now Lincoln, Gaston, and Cleveland Counties in Graham’s stead, responded, “I think so, Colonel, as it is a woman affair, let him go.”

There is some dispute as to what happened next, but most accounts indicate that just as Graham headed home, he heard the firing that announced the opening of the battle. Although separated from his command, he could not resist the fight. He returned to the scene, arriving in time to take part in the final charge up the mountain.

The Patriot victory assured, Graham was seen riding away on his black charger waving his sword. He made his way to his wife’s side, where, just hours later, she gave birth to his only child, Sarah.

After the war, he returned to the site of Graham’s Fort, where he built the house that now stands.

As for Susan Twitty, the young heroine whose quick thinking saved her brother’s life, she returned to her home in Rutherford County, where she married John Miller, a Revolutionary War soldier. Years later, after each of their spouses had died, William Graham and Susan Twitty married.

Graham and his first wife are buried in marked graves in an isolated family cemetery several miles from the current tour stop.

Continue south on N.C. 226 for 2.7 miles to U.S. 29 in the town of Grover. Located along the railroad tracks near the junction are two state historical markers marking the sites of important British movements during the campaign in the Carolinas.

One of the markers notes the site of the encampment of Patrick Ferguson and his Loyalist army October 4 and 5, 1780, just before their fateful showdown with the frontier Patriots at Kings Mountain.

The other marker stands at the place where Cornwallis and his British army entered North Carolina on their second invasion, which took place during the third week of January 1781. It was here that Cornwallis began the chase of Nathanael Greene and Daniel Morgan that over the next two months led the British army halfway across the state, then to Virginia, then back into North Carolina.

Despite the costly setback that Banastre Tarleton had just suffered at nearby Cowpens, South Carolina, Cornwallis exuded confidence while encamped at the current tour stop. Reinforced by 1,530 soldiers, the British commander wrote his superior, Sir Henry Clinton, “Be assured, that nothing but the most absolute necessity shall induce me to give up the important object of the Winter’s Campaign.”

Turn left on U.S. 29, then turn right on S.R. 2278 (Elm Street) and go 0.7 mile to Shiloh AME Zion Church. S.R. 2278 junctions with a short, unnamed, unimproved road almost opposite the church. This treacherous, deeply rutted road terminates at the old cemetery of Shiloh Presbyterian Church. Buried in a well-marked grave in this forested, unkept graveyard is Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Hambright (1727–1817), one of the leastknown Patriot heroes at Kings Mountain.

A native of Germany, Hambright settled in North Carolina at a fort near the mouth of the South Fork of the Catawba River around 1760. An Indian fighter in colonial times, he was an early advocate of American independence. In 1777, he was appointed lieutenant colonel of the militia, a position he held for the duration of the war.

When his immediate commander, Colonel William Graham, prepared to start for home just before the Battle of Kings Mountain, the fifty-threeyear-old Hambright relinquished command of the South Fork Boys to Major William Chronicle, a much younger soldier. When Major Chronicle fell mortally wounded while leading the soldiers up the steep northeastern side of Kings Mountain, the German-born officer assumed command of the brave band, which included his eldest son, John Harden Hambright.

Frederick Hambright was in the thick of the fight when a rifle ball smashed into his leg. Though blood overflowed his boot, he refused the urgent pleas of his men to care for his wounds. Instead, he said, “Huzza, my brave boys, fight on a few minutes more and the battle will be won.” Despite the severity of his wound, Hambright fought on with his men until victory was achieved.

He never fully recovered from the effects of the gunshot and walked with a limp the rest of his life.

Return to the junction of S.R. 2278 and U.S. 29 in Grover. Turn right and drive 1.5 miles northeast to N.C. 216. A state historical marker near the intersection calls attention to the Battle of Kings Mountain and notes that the national military park is located 5 miles southeast.

Turn right on N.C. 216 and drive 1.2 miles south, where the route enters South Carolina and becomes S.C. 216. After another 1.3 miles, you will enter Kings Mountain National Military Park. Follow S.C. 216 as it slices through the forested landscape. Metal signs along the road mark the routes taken by soldiers as they made their way to the showdown on the nearby mountain.

It is approximately 1.9 miles from the park entrance to the visitor center, which is housed in a spacious, modern building of wood and stone. Turn left into the parking area and walk to the center.

Inside, visitors are treated to an excellent audiovisual orientation program and numerous exhibits related to the pivotal fight that occurred here. A self-guided tour of the mountain battleground is also offered. Special events related to the battle and the Revolution are held throughout the year in the amphitheater located nearby. Each year on the anniversary of the battle, reenactors arrive at the park after following the route of the Overmountain Men. Admission to the park is free.

After his overwhelming victory at Camden, South Carolina, on August 16, 1780, Cornwallis began to formulate plans to invade North Carolina, the one state that stood in the path of his total conquest of the South. To pave the way, he dispatched his trusted lieutenant, Major Patrick Ferguson, to northwestern South Carolina and the Piedmont of North Carolina. The thirty-six-year-old career officer from Scotland was to punish insurgents, recruit Loyalist soldiers to assist in the invasion, and protect the left flank of the British army as it poured into North Carolina.

Ferguson was fearful of the frontier Patriots of North Carolina, with whom he had skirmished throughout the summer in the South Carolina upcountry. In late September, he was at his encampment at Gilbert Town when he learned that the Overmountain Men had mustered near their homes across the mountains in what is now Tennessee. In a vain attempt to dissuade the frontiersmen from doing battle with him again, Ferguson sent forth a courier with a threat to “the backwater men,” as he called them. If they did not “desist from their opposition to the British arms,” he would “march his army over the mountains, hang their leaders, and lay their country waste with fire and sword.”

On the other side of the mountains, the fiercely independent frontiersmen of Scots-Irish descent did not wait for Ferguson to make good his threat. Instead, they came after him. They poured over the mountains to join ranks with Patriots from the foothills of the Carolinas and Virginia.

When they reached Gilbert Town in early October, the frontiersmen—attired in hunting shirts and leggings—were disappointed that their opponents had fled. Undaunted, they continued south to Cowpens, South Carolina (where just three months later Americans under Daniel Morgan would inflict a severe defeat on Banastre Tarleton).

At Cowpens on Friday, October 6, the Patriots received intelligence that Ferguson and his 1,100-man army were in the vicinity of Kings Mountain, 30 miles distant. There was no time to be lost. A mounted force of 910 soldiers—approximately half the American army—galloped off in pursuit of Ferguson at nine o’clock that evening. The remainder of the men would follow on foot in the dark, rainy night. As Colonel Isaac Shelby put it, “It was determined … to pursue him [Ferguson] with as many of our troops as could be well armed and well mounted, leaving the work horses and footmen to follow as fast as they could.”

Throughout the miserable night, the men rode and walked in a torrential downpour. When fatigue and exposure threatened both soldiers and horses, Colonels William Campbell, John Sevier, and Benjamin Cleveland conferred with Shelby about the need for rest. Voicing his grim determination, Shelby said, “I will not stop until night if I follow Ferguson into Cornwallis’s lines.” His fellow commanders gave no argument, and the march continued.

Meanwhile, Ferguson had positioned his army on a promontory located within walking distance of where the visitor center stands today. The mountain—a rocky, forested spur of the Blue Ridge—has a six-hundred-yard-long plateau that rises sixty feet above the surrounding plains. Ferguson believed himself to be in a defensible position while he waited for reinforcements and an enemy attack.

On October 5, he had written Cornwallis, who was then in Charlotte, that “three or four hundred good soldiers, part dragoons, would finish the business. Something must be done soon. This is their last push in this quarter and they are extremely desolate and [c]owed.” Although he was anxious to receive additional manpower, Ferguson exuded confidence: “I … have taken a post where I do not think I can be forced by a stronger enemy than that against us.”

Now, just prior to the battle, tradition has it that Ferguson restated his assuredness about his army’s position with these words: “God Almighty could not drive [us] from it.”

By early afternoon on Saturday, October 7, Campbell, Shelby, Sevier, Cleveland, and their soldiers were poised to prove Ferguson wrong. When they were within a mile of the enemy position, the Patriots tied their horses in the mist and proceeded to encircle the mountain. Perhaps a sign that the fortunes of the American war effort were about to turn, the gray skies gave way to bright sunshine in midafternoon. So quiet and secretive was the Patriots’ approach—and so ineffective was Ferguson’s intelligence—that the Americans were within a quarter-mile of the enemy encampment before the first skirmishers opened fire around three o’clock. The ensuing battle lasted exactly one hour. When it was over, the frontiersmen had achieved one of the most important victories of the Revolutionary War. Patrick Ferguson was dead. His Loyalist army had suffered staggering casualties: 157 killed, 164 wounded, and 698 captured. The Patriots had lost but 38 killed and 64 wounded.

To experience the very landscape where the battle was played out, walk the 1.5-mile battleground trail from the visitor center. This paved path follows a circular route that passes along the forested mountain slopes and onto the plateau of Ferguson’s encampment before ending near the visitor center. Numerous monuments, markers, and signs interpret the events that transpired along the route.

The first significant marker is the D.A.R. monument at the site where Major William Chronicle fell during the battle; the marker is on a hillside to the left.

Chronicle and his friend Captain John Mattocks were able to provide invaluable intelligence about the geography of the battleground, for the two men had maintained a deer-hunting camp the previous autumn at the very site of Ferguson’s encampment.

In the absence of Colonel William Graham, Major Chronicle assumed command of the South Fork Boys just before the battle began. Sword in hand, the young Lincoln County major spurred his horse up the steep slope to a point near the site of his former camp. There, he spotted the swarming enemy. He turned and exclaimed to his dismounted soldiers, who had put bullets in their mouths for quick loading, “Face to the hill! Come on my boys, never let it be said a Fork boy run!”

No sooner had Chronicle uttered the command than a Loyalist bullet pierced his heart and toppled him from his saddle. But his shouting men rushed onward. Well-directed fire from the ridge took a deadly toll on the Patriots. Soon after Chronicle was mortally wounded, so were his comrades Captain Mattocks, Lieutenant William Rabb, and Lieutenant John Boyd.

Return to the trail. On the right, you’ll notice a marker at the common grave of Chronicle, Mattocks, Rabb, and Boyd.

All along the trail, you can observe the treacherous terrain the frontiersmen faced as they stormed up the mountain. As it turned out, the densely wooded slopes worked to the advantage of the attackers. Firing down the mountain, Ferguson’s sharpshooters often aimed too high. Moreover, they were forced to shoot at targets who fought from behind trees. As one of the victorious Patriots reported, “[I] took right up the side of the mountain and fought from tree to tree … to the summit.”

The next significant site is the Hoover Monument, located approximately 0.4 mile from the Chronicle markers. A short side trail on the right leads to the monument, which was erected to commemorate President Herbert Hoover’s visit to the battleground on October 7, 1930, during the sesquicentennial commemoration of the Patriot victory. At this site, the president delivered a twenty-two-minute address to an audience of seventy-five thousand—an enormous crowd, considering the isolated location of the battleground and the scarcity of motor vehicles at the time.

Resume the trail as it turns south and begins a steady climb. The Centennial Monument stands near the crest of the hill less than 0.2 mile from the Hoover Monument. Inscribed on this granite memorial are the names of the Patriots killed in the battle.

Soon after the last shots were fired that Saturday afternoon, darkness enveloped the landscape. The victorious frontiersmen, exhausted from their all-night march and the battle itself, had to camp on the ground among the dead and wounded. Injured soldiers suffering from loss of blood screamed out for water. Propped against trees and boulders where they fell, men from both armies expired during the night.

Sunday dawned with a bright sun that cast its rays through the orange, yellow, and red leaves of the dense hardwoods onto a forest floor littered with bodies. One eyewitness described what he saw that day: “The scene became distressing. The wives and children of the poor Tories came in great numbers. Their husbands, fathers, and brothers lay dead in heaps. … We proceeded to bury the dead, but it was badly done. They were thrown into convenient piles and covered with old logs, the bark of old trees, and rocks, yet not so as to secure them from becoming a prey to the beasts of the forests, or the vultures of the air. And the wolves became so plenty, that it was dangerous for anyone to be out at night.”

Near the Centennial Monument, you can enjoy a spectacular view of the surrounding countryside. This was the vantage point that emboldened Patrick Ferguson to make his fateful boast.

Proceed east on the trail as it makes its way along the plateau to the United States Monument, the most impressive marker in the park. Plaques on the base of the towering obelisk bear the names of the American forces involved in the battle.

Among the prominent officers listed are Colonels William Campbell and Isaac Shelby. These two gallant commanders led their soldiers up the southwestern and northwestern slopes in the face of galling fire.

When the battle stood in the balance, Shelby shouted his famous words of encouragement: “Now boys, quickly reload your rifles and let’s advance upon them and give them another hell of fire. … Shoot like hell and fight like demons!”

Colonel Campbell, sensing that triumph was near at hand, charged ahead of his Virginians, exclaiming, “Boys, remember your liberty! Come on! Come on, my brave fellows; another gun—another gun will do it! Damn them, we must have them out of this!”

From the courage of Campbell, Shelby, and all the Indian fighters who had left their frontier homes undefended came the decisive victory at Kings Mountain.

The United States Monument proclaims that the battle here was the turning point of the Revolution.

Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the republic born of the war, described the importance of the events at Kings Mountain: “It was the joyful annunciation of that turn of the tide of success which terminated the Revolutionary War with the seal of our independence.”

Sir Henry Clinton, the longest-serving British commander in chief during the war, termed the Battle of Kings Mountain “a fatal catastrophe.”

Indeed, when news of the devastating setback reached Charlotte, Cornwallis promptly called off his invasion of North Carolina and scampered back to South Carolina, where he lingered for three months while Nathanael Greene assumed command of and reorganized the American forces in the South.

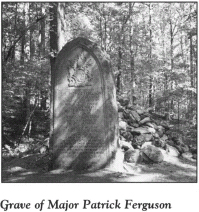

Just east of the United States Monument is a marker at the site where Patrick Ferguson fell.

Until he was brought down, the fearless officer—who was, ironically, the only British soldier on the field—displayed the same gallantry that had earned him a sterling reputation on countless battlefields during the war.

Even as the Patriots began to close in on his position on the plateau, Ferguson, attired in a checkered vest, rode about his troops and blew his silver whistle to urge them to continue the fight. As soon as his junior officers realized the futility of continuing, they pleaded with Ferguson to surrender rather than to have his men annihilated. Their commander was unyielding. Replying that he would not submit “to such a damned banditti,” Ferguson galloped forward with sword in hand in a last desperate charge. As he slashed his way through the oncoming Patriots, his sword broke, yet he rode on until he encountered the waiting rifles of John Sevier’s men. Numerous shots rang out. Six or eight struck their target. One pierced Ferguson’s head. The Loyalist commander’s body and clothing were riddled by bullets. Both of his arms were broken. When he fell from his mount, one of his feet caught in a stirrup. Four of his soldiers stopped his fleeing animal, laid their commander on a blanket, and bore him out of harm’s way.

Turn to the left and walk down the stone steps to a marker at the site where Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Hambright was wounded in the dramatic charge of the South Fork Boys.

When Major Chronicle and his fellow officers fell, Captain Joseph Dickson ordered their surviving comrades to charge. With loud yells, they scrambled up the mountain, only to come face to face with a bayonet charge by the enemy. The Patriots momentarily fell back to a safe position to reload. Then they charged again, this time led by the mounted Frederick Hambright, who continued the fight even after being badly wounded in the thigh.

Return to the stone marker where Ferguson was fatally wounded and continue the trail, which turns sharply south. At the bottom of the hill, you’ll notice a large monument and cairn on the left at Ferguson’s grave site. The dying officer was carried to this spot, where he was propped up with rocks and blankets.

The son of a Scottish judge and the nephew of a major general in the British army, Ferguson (1744–80) aspired to a military career from an early age. By the time he arrived in New York in 1777, he was a veteran soldier who had seen action in Europe and the West Indies. He had achieved his greatest fame in 1776 with his invention of a breechloading rifle. It was said that the weapon could be fired six times a minute by a marksman while lying on his back in a drizzling rain.

Ferguson was considered the best marksman in the entire British army. While serving in the North in the early stages of the war, he once had within the sight of his deadly accurate rifle an unidentified American officer. Yet he refused to squeeze the trigger because he deemed the officer “an unoffending individual who was acquitting himself very cooly [sic] of his duty.” The American officer turned out to be none other than General George Washington.

Tradition maintains that Ferguson had two female companions with him at Kings Mountain. One of them, a woman known as Virginia Sal, was killed early in the battle and laid to rest beside her lover. Her red hair was said to have made her a target for American riflemen. Virginia Paul, the other camp follower, survived the battle. Her coolness impressed her captors, including Colonel William Campbell, who told his victorious soldiers, “She is only a woman, our mothers were women. We must let her go.”

From the Ferguson grave site, the trail winds approximately 0.2 mile to the visitor center. Return to your vehicle. To resume the tour, turn left out of the parking lot and drive south for 0.8 mile to the D.A.R. marker on the left side of the highway.

This stone monument, which stands near the southern boundary of the national park, notes that the Battle of Kings Mountain was fought in York County on South Carolina soil. Without question, the site is now just south of the state border. However, when the battle was fought, it may very well have been in North Carolina. Tradition in the Tar Heel State has it that engineers assigned to survey the line in later years detected the aroma of “mountain dew” in the area and strayed from their path to find the source. Thus, the battleground wound up in South Carolina.

At any rate, it was a joint effort by the two states that made the national military park a reality. In 1926, Congressmen A. L. Bulwinkle of North Carolina and W. E. Stevenson of South Carolina introduced the legislation that led to the park’s establishment.

Turn around near the marker and proceed north for 1.7 miles to the administration office at the national park. Stop here to obtain permission to visit the Henry Howser House, a prominent early-nineteenth-century landmark acquired by the National Park Service in the 1930s.

To reach the house, go north from the administration office for 1.1 miles to Rock House Road (S.R. 11-86). Turn left and drive 0.9 mile to a fire lane on the left. Park nearby and walk 0.3 mile down the lane to the magnificent rock house constructed in 1803 by Henry Howser.

A Revolutionary War soldier who fought in the North, Howser settled near Kings Mountain after the war. Here, he became a friend and neighbor of Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Hambright.

Howser, a talented mason, built the two-story rock masterpiece with the assistance of his wife, Jane, and their slaves. It is similar in construction to the Hezekiah Alexander House in Charlotte.

After years of neglect, the structure was carefully restored by the park service in 1977. Today, it stands in an excellent state of preservation and is surrounded by the forests of the national park.

Retrace your walk on the fire lane. About midway back, you can find the grave of Henry Howser in an ancient family cemetery in the woods on the left.

Return to your vehicle and proceed to the junction of Rock House Road and S.C. 216. Directly across S.C. 216 is an unimproved lane on the eastern side of the highway. The home of Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Hambright stood a hundred yards down this lane until it burned in 1926.

Before Hambright built the house, he lived in a cabin that stood to the east. Traces of the cabin’s foundation are still visible on the forest floor. Following the battle here, Hambright purchased significant acreage in the area. In his later years, the former militia officer could proudly proclaim that he owned the very peak where he had gallantly fought to turn the tide for American independence.

Turn left on S.C. 216 and drive back into North Carolina to where N.C. 216 junctions with U.S. 29. Turn right, and follow N.C. 216 for 4.9 miles to U.S. 74 Business (King Street) in the city of Kings Mountain. You’ll notice a state historical marker for the battle.

Turn left on U.S. 74 Business and follow it west for 1.6 miles to Afton Drive. Turn left, go 0.1 mile to a driveway on the left, and park nearby. Walk up the driveway approximately a hundred yards to the Goforth cemetery.

Buried in the small, untended graveyard is Preston Goforth (1739–80), one of four Rutherford County brothers killed in the Battle of Kings Mountain. His grave tells one of the many stories of fratricide written during the war. Preston was the only brother to fight for the Patriots. When he and one of his siblings encountered each other in the heat of battle at Kings Mountain, they promptly fired their weapons. According to Colonel Shelby, “Two brothers, expert riflemen, were seen to present at each other, to fire and fall at the same instant.”

Retrace your route to the intersection with N.C. 216. Proceed east on King Street for six blocks to N.C. 161 and turn left. It is 1.6 miles to the Gaston County line. Created from Lincoln County in 1846, Gaston County was named for Judge William Gaston, the noted North Carolina jurist whose Patriot father was murdered on the New Bern waterfront by Tories. (For an account of this incident, see The Coastal Rivers Tour, page 77.)

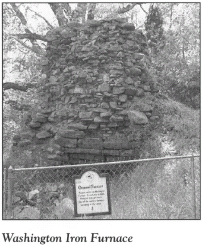

Continue northeast on N.C. 161 for 1.8 miles to S.R. 1402 (Long Creek Road). Turn left and proceed 0.7 mile to the bridge over Long Creek. On the left side of the road near the bridge are a large picnic shelter and the marked remains of the Washington Iron Furnace, a facility that produced cannonballs during the Revolution.

Benjamin Ormand maintained a farm along the banks of Long Creek, the same waterway Frederick Hambright lived on for many years. When Cornwallis passed through the area in January 1781, Banastre Tarleton’s cavalrymen raided the Ormand residence, taking bedding and cooking utensils. As they prepared to depart, they removed the blanket from the cradle in which James Ormand, an infant, was lying. One of their number used it as a saddle blanket. In a final act of desecration, the raiders took the large family Bible belonging to Benjamin Ormand and used it for a saddle.

Return to the junction with N.C. 161. Turn left, drive 1.5 miles to N.C. 274 in Bessemer City, and turn left again. It is 4.6 miles to a state historical marker for Tryon County in the community of Tryon. Created by the colonial assembly in 1769 and named in honor of Royal Governor William Tryon, the massive, short-lived county stretched from the Catawba River on the Mecklenburg County line to the western frontier. Because of its less-than-Patriotic name, Tryon County was abolished in 1779, when it gave way to Lincoln and Rutherford Counties.

In 1774, commissioners chose to locate the Tryon County Courthouse at the site of the current tour stop, halfway between what are now Bessemer City and Cherryville. In July 1775, the Tryon County Committee of Safety was organized here. Several weeks later, when the committee convened again, its members joined other county freeholders to form “An Association.”

On August 14, the forty-nine members of the “Association” adopted a set of resolutions that were the result of the growing unrest in the colonies. Even though the document did not go so far as to declare independence from Great Britain, its fiery language left no doubt that the signers were displeased with the policies of the mother country.

Resolving to unite “under the most sacred ties of religion, honor, and love of country” in defense of their “natural freedom and constitutional rights against all invasions,” the signers pledged to “take up arms and risk” their lives and fortunes in order to maintain “the freedom of their country.” While the members of the “Association” agreed to “profess all loyalty and attachment” to King George III as long as he would secure them “those rights and liberties which the principles of our Constitution require,” they foresaw the bloodshed that was soon to come. Consequently, the men of Tryon County resolved to obtain a supply of gunpowder, lead, and flints from the Patriots of Charleston.

Despite its irregularities in spelling and grammar, the Tryon Resolves served as strong testimony of the defiant spirit that characterized the North Carolina frontier in 1775. In 1780, some signers of the resolves (including Frederick Hambright) and their families took part in the important battles at Ramsour’s Mill and Kings Mountain.

Near the Tryon County marker, a bronze tablet on a granite boulder erected by the D.A.R. commemorates the resolves drafted and adopted at this site. The names of the signers are listed on the tablet.

At Tryon, turn right onto S.R. 1440 (Tryon School Road). Proceed 2.2 miles to N.C. 279, turn right, drive east for 2.9 miles to S.R. 1448, turn left, and head north for 1.2 miles to Pasour Mountain, located on the left.

This 4-mile-long ridge reaches a maximum altitude of eleven hundred feet. It was once known as LaBoone Mountain, for a Tory couple by that name who lived in a cave on the mountainside during part of the Revolution. Area Patriots ultimately pressured the LaBoones to leave their cave. The mountain assumed its present name in honor of a local family whose allegiance was with the cause of independence.

Continue 1.6 miles north on S.R. 1448 to S.R. 1703 (Ike Lynch Road). Turn right, proceed 0.9 mile to N.C. 155, turn left, and go 1.8 miles to the town of High Shoals, located on the banks of the South Fork River. A state historical marker for John Fulenwider stands on the left side of N.C. 155 just north of the small, white High Shoals United Methodist Church.

Fulenwider (1756–1826) came from Switzerland to North Carolina with his family when he was a boy. As a member of the Rowan County militia, he fought with the Patriots in the victories at Ramsour’s Mill and Kings Mountain. At the close of the war, he settled in Lincoln County, where, like many of his fellow veterans, he engaged in the lucrative iron-manufacturing business. Through his skill, hard work, and business acumen, Fulenwider accumulated a twenty-thousand-acre estate. He is buried in the rock-walled cemetery adjacent to the church.

From the Fulenwider grave, follow N.C. 155 south for 7.1 miles to U.S. 321 at Dallas, the former seat of Gaston County. Drive south on U.S. 321 through Gastonia, the modern county seat. After 6.6 miles, turn left on S.R. 2411, then drive 0.2 mile east to Olney Presbyterian Church.

This historic church was established in 1792. Located adjacent to it is its equally historic cemetery. A bronze plaque near the old entry gate lists the names of eighteen Revolutionary War soldiers interred here.

Among the names on the list is that of Isaac Holland. A native of England, Holland arrived in America as a child after a harrowing transatlantic crossing. During the voyage, a leak developed that threatened to fill the ship with water. Just as everyone aboard had all but given up hope, the leak suddenly stopped. It seems that a fish got caught in the hole and thus sealed the leak.

A private throughout the Revolution, Holland fought at Kings Mountain. Despite his exhaustion following that engagement, he walked to his house near what is now Gastonia on the night after the battle.

Return to U.S. 321. Turn right and proceed north for 3.3 miles to U.S. 29/U.S. 74 (Franklin Boulevard). Turn right, drive east for 8.9 miles to N.C. 7, turn left, and go north for 0.9 mile to Woodlawn Street (S.R. 2021) at Belmont Abbey College. Turn left and drive 0.7 mile to Goshen Presbyterian Church in North Belmont. The church is on the right at the junction of Woodlawn and Roper Streets.

Organized in 1764, this is believed to be the first Presbyterian church west of the Catawba River. The present brick structure is the latest in a series of buildings that began with a small log church that was located adjacent to the nearby cemetery. Many charter members of the church were ardent Patriots who fought in the Revolution; some are buried in the cemetery.

To visit the historic burial ground, proceed north on Woodlawn for 0.2 mile. A bronze plaque on the rock-walled entrance to the oldest portion of the cemetery lists the names of nineteen Revolutionary War soldiers interred here. Among the distinguished Patriots is Captain Samuel Martin, a native of Ireland and a veteran of the Battle of Kings Mountain who died in 1836 at the age of 104. Three years before his death, he was granted a pension for his service in the Revolution.

Continue north on Woodlawn for 0.5 mile to Hickory Grove Road. Turn right, then turn right again almost immediately onto Perfection Avenue (S.R. 2040). Follow Perfection as it winds east for 0.9 mile to West Catawba Avenue; continue 1.8 miles on Perfection to Hawthorne Street in the town of Mount Holly. Turn left on Hawthorne and proceed one block north to West Central Avenue, where you’ll notice a number of public-school buildings. The home of Captain Robert Alexander—another of the distinguished Patriots buried in the cemetery at Goshen Presbyterian Church—once stood in the vicinity of the school buildings.

Alexander was a respected statesman in the days leading up to the war, serving at the First and Third Provincial Congresses at New Bern and Hillsborough, respectively. Some historians have concluded that he was the draftsman of the Tryon Resolves. When the war of words became a war of bullets, Alexander turned his attention to military matters. He rendered effective service as a militia captain for the duration of the war.

Alexander was married to Mary Jack, the sister of James Jack, the famous courier of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. Their daughter, Margaret Alexander, was the fiancée of Major William Chronicle. Like Chronicle, Captain Alexander fought at Kings Mountain.

Continue on Hawthorne for 0.2 mile to N.C. 27 (West Charlotte Avenue). Turn right and drive east for 0.5 mile to an unpaved road on the left side of the highway just before the bridge over the Catawba River. Turn left and follow the road to its terminus at a landing. This site provides an excellent view of the Catawba at a point near two important fords used during the Revolution.

As Cornwallis pushed his army east through Lincoln County (which at that time encompassed all of what are now Gaston and Catawba Counties) in pursuit of Nathanael Greene in January 1781, General William Lee Davidson posted small bands of American militiamen at Tuckaseegee Ford (on the south) and Tool’s Ford (on the north). Tuckaseegee Ford, located on the road leading from Charlotte to Ramsour’s Mill, was defended by two hundred men under the command of Colonel Joseph Wilson of Surry County. Less than half that number were stationed at Tool’s Ford under the command of Captain Potts of Mecklenburg.

Return to N.C. 27. Turn right and proceed northwest for 2.9 miles to Westland Farm Road (S.R. 1924). A state historical marker here honors Colonel Joseph Dickson (1745–1825), a remarkable soldier and statesman.

Turn left on Westland Farm Road. After 0.3 mile, you’ll notice a large house on the left set back from the road. The brick building in the rear (now used as a swimming-pool house) is what remains of the eighteenth-century home constructed by Colonel Dickson.

Six months before the American colonies declared their independence, Dickson was appointed a captain in the Continental Army. When the war came to western North Carolina in 1780, he rendered effective service as a major of “the Lincoln County Men,” a militia unit that was conspicuous at Kings Mountain. His leadership in the stand against Cornwallis during the British invasion of North Carolina in 1781 led to his promotion to colonel.

Upon his election to the United States House of Representatives in 1799, Dickson became a strong supporter of Thomas Jefferson’s candidacy for president. When the 1800 election resulted in an electoral tie between Jefferson and Aaron Burr, the contest was thrown into the House. After thirty-five ballots, Dickson rose to the floor and used his influence to gain the deciding votes for Jefferson.

General Griffith Rutherford camped at this site on June 19, 1780, in his futile attempt to reach Ramsour’s Mill in time for the battle there.

Turn around near the Dickson home and retrace your route to N.C. 27. Turn right, drive 2.6 miles to N.C. 273 in downtown Mount Holly, turn left, and go north for 5.2 miles to N.C. 16. Turn left and go 0.2 mile north to the state historical marker calling attention to Oak Grove, the home of Colonel James Johnston.

To see the grave of this Revolutionary War luminary, turn right just north of the marker onto S.R. 1916 (Killian Road). Proceed 2 miles east to Pine Valley Drive, turn left, go 0.1 mile, and turn left onto Meadow View. After 0.3 mile, you’ll notice a small cemetery enclosed by an iron fence on the left side of the road. Johnston (1742–1805) is buried here.

Johnston’s father was one of the early settlers along the banks of the Catawba in Tryon County. As a young man, James Johnston was one of the first local citizens to openly advocate independence. It was he who, on the morning of June 19, 1780, notified Griffith Rutherford at his encampment near Joseph Dickson’s plantation that Colonel Francis Locke intended to attack Tory forces at Ramsour’s Mill in Lincolnton the following morning. Ironically, Locke had not received an earlier dispatch from Rutherford ordering him to come to Dickson’s plantation to confer with Rutherford.

At Kings Mountain, Johnston commanded the reserves, who were called into service soon after the battle began.

His magnificent two-story home stood near the cemetery until well into the twentieth century.

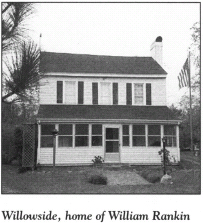

Return to N.C. 16. Turn left, proceed south for 0.2 mile to N.C. 273, turn right, and drive 0.2 mile to Stanley-Lucia Road. Turn right and follow Stanley-Lucia as it winds east for 3.3 miles to Willowside Drive (S.R. 1935). Turn left and go 0.5 mile to the Rankin House—otherwise known as “Willowside”—located on the right at 201 Willowside.

William Rankin settled with his family along nearby Stanley Creek prior to the Revolution and began construction on the two-story structure in 1778. The war intervened before the dwelling could be completed. Rankin volunteered as a private in the company of Captain Robert Alexander. Over the next two years, he saw action in both Carolinas against British regulars, Tories, and Indians.

According to his great-grandson, who now owns and lives in the dwelling, Rankin was badly wounded and lost a leg at Kings Mountain. Rather than entrust his well-being to the scant medical care available on the battlefield, he hired someone to bring him home, where he recuperated. When Rankin died at the age of ninety-three, he was the last surviving Revolutionary War soldier in Gaston County.

Beneath the existing exterior walls of the home are the logs of the original structure. The interior furnishings include two pieces crafted by Peter Eddleman, a local Revolutionary War soldier covered later in this tour.

Return to Stanley-Lucia Road. Turn left, drive west for 1.9 miles to Old N.C. 27. Merge onto old N.C. 27 and proceed west for 0.8 mile to the town of Stanley, and turn right. It is 3.1 miles north to the Lincoln County line.

Created when Tryon County was abolished in 1779, Lincoln County was named in honor of Major General Benjamin Lincoln. Concerning the county’s contribution to the war, noted historian John C. Wheeler wrote, “There are few portions of North Carolina, around which the halo of chivalric deeds and unsullied patriotism clusters more brilliantly than this section.” In the closing years of the Revolution, Lincoln County served as the landscape for two of the most important battles fought in North Carolina.

A native of Hingham, Massachusetts, Benjamin Lincoln (1733–1810) was a key player at both the high and low points of the war. As commander of the Southern Department of the Continental Army, he suffered the loss of Charleston in 1780. A year later, General George Washington selected him to accept the British sword of surrender at Yorktown. Soon thereafter, Lincoln was appointed the nation’s first secretary of war, a post he held until 1783.

From the county line, continue northwest on N.C. 27 for 7.3 miles to N.C. 150. Follow N.C. 27/N.C. 150 west for 1.7 miles to N.C. 155 on the east side of Lincolnton, the seat of Lincoln County. Like the county, the town was named in honor of Benjamin Lincoln. Chartered in 1785, it is the second-oldest incorporated town west of the Catawba.

Turn right on N.C. 155 and drive 1.1 miles north to Sigmon Road at the Lincolnton Plaza Shopping Center. Turn left, proceed west for 0.2 mile to North Aspen Street, turn left again, and go south for 1.2 miles to the state historical marker for the Battle of Ramsour’s Mill; the marker is on the right side of the road at Lincolnton High School.

To reach the battlefield, turn right onto Skip Lawing Drive just south of the marker and proceed west for 0.3 mile to Jeb Seagle Drive. Follow Jeb Seagle Drive as it circles around to Battleground Stadium (on the left) and Lincolnton Middle School (on the right). Turn right into the school’s parking lot.

Although much of the battlefield’s historical integrity has been lost as a result of the construction of three public schools, there is much to be seen at this place where the struggle for American independence ever so subtly began to turn in favor of the colonies. From the parking lot, walk up the hill between Lincolnton Middle and Battleground Elementary Schools. Stop at the audio station, located in a grove of trees, where a three-minute taped message gives a synopsis of the battle fought on this very spot in the earlymorning hours of June 20, 1780.

British military control of South Carolina and Georgia was virtually complete with the surrender of Charleston by Benjamin Lincoln on May 12, 1780. Cornwallis then began to shift his attention to North Carolina, which had been relatively free from British troops up to that time. Though anxious to move north, Cornwallis remained in South Carolina for the summer, so his soldiers might rest and be resupplied.

Two of his American officers—Lieutenant Colonel John Moore and Major Nicholas Welch—wanted to pave the way for the British invasion of North Carolina. In early June, they made their way home to Lincoln County, where they began organizing Tories to aid in the conquest of the state. Their efforts paid off. By June 13, their Tory recruits began to arrive at Ramsour’s Mill, which was located on Clarks Creek several hundred yards west of the current tour stop.

Upon learning of the Tory gathering, General Griffith Rutherford, camped 35 miles away in Charlotte, dispatched orders to Colonel Francis Locke of Rowan County and Major David Wilson of Mecklenburg County to raise a force to scatter the Loyalists.

On the night of June 19, Locke put his small army of four hundred poorly trained, ill-equipped militiamen from Rowan, Mecklenburg, and Lincoln Counties on a 15-mile march west from Mountain Creek in what is now Catawba County to Ramsour’s Mill. By that time, the contingent of Loyalists camped in the woods atop the hill at the current tour stop had grown to thirteen hundred. As many as one-fourth of their number were unarmed. Others were either too young or too old to fight.

Before first light on June 20, Locke’s forces were close to the Tory encampment when the colonel was approached by Adam Reep, a local Patriot who had scouted the Tories’ position. After being briefed by Reep about the Loyalists’ troop strength and the local terrain, Locke decided to launch a surprise attack.

His cavalry captains out front, Locke sent his men up the eastern slope of the hill at dawn. It was a foggy morning, with visibility limited to fifty feet. Despite being caught off guard, the Tories quickly rallied. For almost two hours, a horrific battle was fought atop the hill. The hand-to-hand action pitted neighbor against neighbor—even brother against brother. None of the combatants had uniforms. The Patriots pinned white paper to their hats for identification, and the Loyalists stuck green twigs in theirs.

Symbolic of the fratricidal feelings at Ramsour’s Mill is the story of Reuben and William Simpson, two brothers who married daughters of a local Whig, William Sherrill. Like his father-in-law, William Simpson was a Patriot, but Reuben was an avowed Tory. While the Patriot brother was on a scouting party, he learned that Reuben was fighting for the Tories at Ramsour’s Mill. William galloped off toward the battlefield, ran his horse to exhaustion, and ran the rest of the way on foot—all for the purpose of seeking out and killing his brother. Upon his arrival, however, he learned that the battle was over.

Although the Patriots were outnumbered more than three to one, they carried the day. The thoroughly routed Tories retreated down the western side of the hill toward the mill. Once the fog lifted and the smoke from the muskets dissipated, the battlefield displayed a grim scene. More than seventy men were dead, some with skulls broken by gun butts. Another two hundred were badly wounded. Losses were equally divided between the two factions.

You’ll notice a small marker near the audio station. In a long trench at this spot, where the Tories made their final stand, the bodies of seventy soldiers were interred in a mass grave the day after the battle.

Much like Kings Mountain, the Battle of Ramsour’s Mill involved no British troops. Nevertheless, the decisive Patriot victory was of extreme importance to the outcome of the war. It effectively put an end to Tory support of the British war effort throughout the area. Thus, Cornwallis was robbed of assistance he desperately needed when he subsequently crossed into North Carolina. But of more immediate importance, the battle provided the inspiration for the pivotal Patriot victory 30 miles away at Kings Mountain less than four months later.

From the mass grave site and the audio station, walk up the hill to the Warlick Monument, located at the summit in the middle of Battleground Elementary School’s playground. This large stone memorializes Captain Nicholas Warlick, a Tory officer who died while bravely leading his men on horseback. Also buried here are his brother, Phillip, and another Loyalist, Israel Sain.

Continue walking east to the bus parking lot at the rear of Lincolnton Middle School. A small park on the eastern side of the lot contains several millstones from Ramsour’s Mill. Ironically, Cornwallis camped here, several hundred yards from the mill, just seven months after the disastrous defeat at the same site.

On January 24, 1781, Cornwallis’s army, which had swollen to twenty-five hundred men after a recent infusion of troops under General Alexander Leslie, poured into Lincoln County. The Redcoats were in hot pursuit of the fleeing Daniel Morgan, whose march was slowed by British prisoners taken at Cowpens. Cornwallis hoped to catch General Morgan and destroy his army before he could cross the Catawba and join forces with Nathanael Greene.

By the time Cornwallis, Tarleton, General Charles O’Hara, and the Redcoat army converged at Ramsour’s Mill on January 25, Morgan was already on the eastern bank of the river. For three days, the massive British army camped all about the landscape at the current tour stop. Cornwallis set up his headquarters under a chestnut tree. Camped near him were some of his Hessian troops. Cornwallis sent foragers into the countryside to secure grain, and Ramsour’s Mill was kept in continuous operation to produce food for the British soldiers and their animals.

Walk through the parking lot to the southern end of Lincolnton Middle School. Proceed around the corner of the building along the trail that runs on the edge of the athletic field. After several hundred yards, look down the hill to your left. You’ll see a large brick tomb between the field and Jeb Seagle Drive. Buried here are six of the Whig captains who fell at Ramsour’s Mill. Among their number was Captain Galbraith Falls, who led the initial Patriot charge on horseback. He was the first soldier killed in the battle.

Cross the athletic field to the parking lot in front of Lincolnton Middle School. Walk to the western side of Jeb Seagle Drive near the entrance to Battleground Memorial Stadium. Turn left and walk along the shoulder of the road for 0.2 mile to the second driveway on the right. Turn right at the driveway and go through an opening in the trees to the bottom land along Clarks Creek. After passing through the opening, you’ll notice the marked grave of Martin “Crooked Nose” Shuford. This Tory leader acquired his soubriquet after suffering a mishap while preparing to hang Isaac Wise, a teenager. (For more information, see The Foothills Tour, pages 245–46.) Wounded at Ramsour’s Mill, Shuford died two days after the battle and was laid to rest.

The cabin of Christian Reinhardt was located just south of the Shuford grave site, and Ramsour’s Mill was several hundred yards north of Reinhardt’s cabin and outbuildings. During the three-day occupation of this site by the British army in January 1781, Cornwallis’s Hessians pilfered the Reinhardt farm. Trouble quickly ensued.

One of the mercenaries, upon smelling soup that Mrs. Reinhardt had cooking in the fireplace, stole into the cabin to help himself to some home cooking. When he heard Mrs. Reinhardt’s footsteps, the young German quickly gulped a cupful of boiling soup. He fell dead soon thereafter.

His comrades in arms, convinced that Mrs. Reinhardt had poisoned the dead man, threatened to do her bodily harm. Christian Reinhardt reported the threats to Cornwallis, who promptly placed a guard around the Reinhardt place for the protection of the occupants.

Cornwallis asked Reinhardt to show him the position that Lieutenant Colonel Moore and his Loyalists had held at the beginning of the Battle of Ramsour’s Mill. After touring the field, Cornwallis remarked, “Moore had a good position, but he did not know how to defend it.… In the first place, he ought to have obeyed orders and fallen back on Colonel Ferguson’s command. Often the most sanguine are the most disappointed. But Moore deserves credit for his loyalty.”

While camped at Ramsour’s Mill, Cornwallis made one of the most fateful decisions of his campaign in the Carolinas. Contrary to standard European military practice, the British commander ordered that all his army’s expendable baggage—including large quantities of rum—be burned. Most of his wagons—beginning with his own—were torched. Only those carrying salt, medicine, and ammunition were saved. Cornwallis reasoned that he must lighten his army to hasten the chase of Greene and Morgan.

Even Charles O’Hara, Cornwallis’s trusted brigadier general, questioned his commander’s judgment: “In the situation, without baggage, necessaries, or provisions of any sort for officer or soldier, in the most barren, inhospitable, unhealthy part of North America, opposed to the most savage, inveterate, perfidious, cruel enemy, with zeal and bayonets only, it was resolved to follow Greene’s army to the end of the world.”

When Nathanael Greene received intelligence of Cornwallis’s decision at Ramsour’s Mill, he uttered words that predicted the ultimate outcome of the war: “Then he is ours!”

Before he put his army on the march toward the Catawba on January 28, Cornwallis offered his gratitude to the Reinhardt family for its kindness to him and his soldiers. He paid Christian Reinhardt for the leather and beef his army had used. To Mrs. Reinhardt, he addressed a polite note, to be delivered to her with his personal mahogany tea box. Upon mounting his horse to depart, Cornwallis doffed his hat and said to Christian Reinhardt, “I do hope and think that the time is near when you can be down under your own shades in peace with the British Flag floating over your heads.” He then rode away to take up pursuit of the Americans—a chase that would lead him to the British surrender at Yorktown.

Eight acres of bottom land at the current tour stop are owned by the Lincoln County Historic Properties Commission. A long-range master plan is being formulated for the development of a site with period buildings that will re-create the Reinhardt farm and mill site.

Return to your car. Retrace Jeb Seagle Drive and Skip Lawing Drive to Linwood Drive. Turn right on Linwood and proceed 0.3 mile to North Grove Street. Turn left, go to West Main Street, turn left again, and drive east toward the imposing Lincoln County Courthouse. Built around 1923, the courthouse stands on a square in the heart of the county seat.

Park just west of the courthouse near the Lincoln County Citizens Center, the large auditorium/office building on the right. Walk into the lobby of the Citizens Center to see a wall-size mural depicting the scene at Ramsour’s Mill at daybreak on June 20, 1780, just as the battle was about to begin.

From the Citizens Center, walk across the street to the courthouse grounds. Near the end of the northern lawn is a granite rock known as “Tarleton’s Tea Table.” It is marked by a D.A.R. plaque. Legend has it that the infamous British cavalry commander enjoyed tea upon the rock while camped in Lincolnton in 1781. It was moved to its present site from the Ramsour’s Mill battleground.

Walk to the southern end of the courthouse grounds and cross the street to South Aspen. Follow the sidewalk for one block to the junction with Church Street at Emmanuel Lutheran Church. A state historical marker for John Gottfried Arends stands in the next block on the left side of the street, at the entrance to the Old White Church Cemetery.

Just inside the cemetery is the imposing gravestone for Arends (1740–1807), the founder and first president of the North Carolina Synod of the Lutheran Church. Born in Germany (his marker is inscribed in German and English), Arends settled in Rowan County in 1773. There, he served as a schoolteacher. On August 28, 1775, as tensions with Great Britain were mounting, he became the first man to be ordained a Lutheran minister in North Carolina.

Throughout the Revolution, Arends traveled by horseback to preach to congregations in Lincoln, Catawba, Iredell, Cabarrus, Rowan, Davidson, Guilford, and Stokes Counties. From his makeshift pulpits came a message of American independence. As a result of his outspoken support for the cause of the colonies, he was threatened, harassed, and persecuted. Nevertheless, he was unflappable, often riding more than 50 miles a day to preach and teach.

Return to your vehicle. Enter the traffic circle around the courthouse, proceeding counterclockwise. On the eastern side of the courthouse, turn right onto East Main Street. Drive through Lincolnton’s central business district for three blocks to the junction with Cedar Street at the post office. The Lincoln County Museum of History, located in the Lincoln Cultural Center at the northeastern corner of the intersection, features exhibits and displays dating from precolonial days. Of special interest is an outstanding diorama of the Battle of Ramsour’s Mill.

Continue on East Main Street for 0.7 mile to the junction with N.C. 27/N.C. 150/N.C. 155. Proceed east on N.C. 27/N.C. 150 for 2 miles to where the roads separate. Turn left onto N.C. 150 and drive 5.4 miles to S.R. 1349. Turn right, travel 1.2 miles to S.R. 1362, turn right again, go 1.8 miles to S.R. 1382 (Vesuvius Furnace Road), and turn left. Vesuvius, the oldest house in Lincoln County, is on the left after 1.2 miles.

The eastern end of the imposing, two-story frame mansion was constructed in 1792 by Revolutionary War hero Joseph Graham (1759–1836). He made subsequent additions to the structure in 1810 and 1820.

Born in Pennsylvania, Graham came to Mecklenburg County with his widowed mother and four siblings when he was seven years old. As a teenager, he witnessed the proceedings that produced the disputed Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence on May 20, 1775. Three years later, he enlisted in the Continental Army.

From 1778 to 1781, Graham participated in nineteen engagements and rose from private to major. After serving as quartermaster for Benjamin Lincoln in South Carolina, he returned home. At the Battle of Charlotte on September 26, 1780, he commanded the rear guard of William R. Davie’s army. His tactics against Tarleton’s cavalry enabled Davie to elude capture by Cornwallis.

After the war, Graham settled in Lincoln County, where he began construction of the home at the current stop. He and other Revolutionary War heroes developed the local iron industry, which gave the county an unusually high standard of living in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The state used his Vesuvius Iron Furnace to help construct the bridge that stands near the house.

In 1787, Graham married Isabella Davidson, the daughter of Revolutionary War notable John Davidson. (For information on Davidson, see The Hornets’ Nest Tour, pages 174–75.)

Return to S.R. 1362, turn left, and drive 1.3 miles to N.C. 73. Turn left, go east for 1.3 miles to S.R. 1511 (Old Plank Road), turn right, and proceed 0.2 mile to S.R. 1360 (Brevard Place Road). Located at this junction is a state historical marker for Machpelah Cemetery.

To visit the cemetery, turn right on S.R. 1360 and park in the lot of Machpelah Presbyterian Church, located 0.1 mile south of the junction. The burial ground is adjacent to the church, which was built around 1848.

Prominent among the historic graves is that of Joseph Graham.

Also buried here is Alexander Brevard (1755–1829). Born in Iredell County, Brevard was one the eleven children of John Brevard. Alexander’s oldest sister, Mary, married General William Lee Davidson, the Patriot martyr at the Battle of Cowan’s Ford. Another sister married Ephraim Davidson, who as a young soldier alerted Daniel Morgan of the movement of Cornwallis’s army toward the Catawba. Alexander’s brothers John Jr. and Adam served in the Continental Army. Adam and another brother, Hugh, both fought at Ramsour’s Mill. Ephraim, Alexander’s oldest brother, is believed to have been the draftsman of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. (For more information on the “Meek Dec,” see The Hornets’ Nest Tour, pages 189–92.)

Alexander Brevard was one of the few regular soldiers who participated in the American Revolution from beginning to end. Commissioned a lieutenant in the Continental Army, he showed great promise as a young officer in George Washington’s campaign in the North. In 1780, when the war shifted to the South, Brevard served as quartermaster under General Horatio Gates. After the American debacle at Camden, he served under Nathanael Greene until the end of the war. He won accolades for his valor in the ferocious fighting at Eutaw Springs, South Carolina, less than a month before Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown.

An iron-industry associate of Joseph Graham, Brevard married a daughter of John Davidson, as did Graham. He settled in Lincoln County after the war.

Continue south on S.R. 1360 for 1.6 miles. Mount Tirzah, the magnificent Georgian plantation house constructed by Alexander Brevard around 1800, once stood on the left side of the road here. A fire destroyed the mansion in 1969.

It is another 0.2 mile south on S.R. 1360 to the bridge over Leeper’s Creek. The almost unidentifiable remains of Mount Tirzah Forge, one of the iron-manufacturing facilities of Alexander Brevard, are on the creek to the left of the bridge.

Turn around and retrace S.R. 1360 to S.R. 1511. Turn right and drive 0.2 mile southeast to a stone D.A.R. marker on the left side of the road. The Old Dutch Meeting House, a church that served the settlers in the eastern part of Lincoln County during the Revolution, once stood at this site. Buried in unmarked graves in the field near the marker are Jacob Forney, Sr., and his wife, Maria. This daring couple braved the Indians and the wilderness west of the Catawba to settle in the area about 1754.

Born in 1721, Forney was too old to shoulder a musket during the Revolution. Nonetheless, he was an unwavering supporter of the Patriot cause. Three of his sons—Peter, Abram, and Jacob Jr.—returned from the war as heroes. While they were away fighting, their father almost capitalized on an opportunity to kill Cornwallis. His encounter with the British commander is recounted later in this tour.

Continue southeast on S.R. 1511 for 3.2 miles to S.R. 1412. Here stands a state historical marker for Peter Forney (1756–1834), whose grave and homesite are located nearby.

Born soon after his father settled in Lincoln County, Peter grew up on the frontier. Over the course of the fight for independence, he battled Indians, Tories, and British troops. He arrived with General Griffith Rutherford just hours too late to participate in the Patriot victory on his home turf at Ramsour’s Mill.

In late January 1781, Captain Forney played a key role in General Davidson’s unsuccessful attempt to hold back Cornwallis at Cowan’s Ford. Later in 1781, the company of dragoons commanded by Forney was instrumental in convincing Major James Craig to evacuate British troops from Wilmington. Following the war, the state appointed Forney general of the North Carolina militia. He also served the new republic as a presidential elector and congressman.

To visit his grave, turn right on S.R. 1412 and go 0.5 mile south. Park on the shoulder and walk to the driveway on the left side of the road. Proceed along the edge of the woods in a direction parallel to the driveway for 50 yards, then turn right into the woods and walk 150 feet to the forested site containing the graves of Forney, his wife, and other family members. This isolated cemetery is being restored by its owner, the Lincoln County Historic Properties Commission. The knoll on which it rests lies above the site of Forney’s plantation home, Mount Welcome.

Return to your vehicle and continue south on S.R. 1412 for 0.6 mile. Park again on the right shoulder and walk to the steel bridge on the right. Now closed to vehicular traffic, the span is owned by the Lincoln County Historical Association. From the bridge, you can enjoy a magnificent view of Dutchman’s Creek, where Peter Forney’s Mount Welcome Iron Forge was once located. Until 1791, when he sold his interest, Forney was a partner with fellow Patriots Alexander Brevard, Joseph Graham, and John Davidson in “the Big Ore Bank,” as the extensive iron deposits east of Lincolnton were known. Forney’s mansion stood on the hill across the road on the northern side of the creek.

Walk back to your vehicle and retrace your route to S.R. 1511. Turn left, drive west for 0.6 mile to S.R. 1383 (Ingleside Farm Road), turn right, and drive north for 1.6 miles to N.C. 73. On the left side of the intersection is Ingleside, one of the finest antebellum mansions in the North Carolina Piedmont. For many years, this magnificent two-story brick structure, built around 1817, was considered the finest dwelling in the western part of the state.

Daniel Forney, who succeeded his father, Peter, in the United States House of Representatives, constructed Ingleside. It is said that while he was in Washington, Daniel persuaded Benjamin Latrobe, the architect of the Capitol, to draw the plans for the Lincoln County mansion.

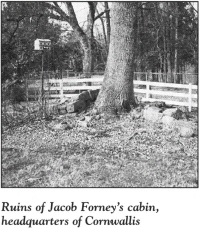

Forney’s elegant mansion stands at the site of the home of his grandfather, Jacob Forney, Sr. A pile of foundation rocks on the western side of the house is all that remains of Jacob’s multistory log cabin, which stood during the Revolution. A tall wooden structure with gunports is nearby. It served as a fortress for Forney and his family when Indians attacked.

Although he was an accomplished Indian fighter in colonial times, Jacob Forney was too old to serve as a soldier in the Revolution. Nonetheless, he was an unrepentant supporter of the American cause. In 1775, he was on hand at Tryon to sign the defiant resolves enacted there.

Forney suffered his greatest indignity of the war when Cornwallis used his flourishing plantation as a headquarters in early 1781.

After leaving Ramsour’s Mill on January 28, Cornwallis, in his quest to overtake Greene and Morgan, marched his Redcoats east across Lincoln County to the Catawba River at nearby Beatties Ford. Upon finding the river impassible because of heavy rains, he moved his army back 5 miles to the current tour stop.

For three days and four nights, the massive British army camped at Jacob Forney’s plantation. Stretching for more than a mile, the encampment extended to the plantation of Peter Forney, located northwest of Ingleside at that time. The British commander took up residence on the upper floor of Jacob Forney’s cabin, while his reluctant hosts were sequestered in the basement.

During their stay, the British soldiers slaughtered and ate Forney’s complete stock of cattle, swine, sheep, geese, and chickens and consumed his grain and brandy. Upon being informed by local Tories that Forney had a large treasure of gold, silver, and jewelry hidden on the premises, the Redcoats scoured the entire estate until they found the aged couple’s lifetime savings.

The discovery and plunder of the Forney treasure almost cost Cornwallis his life. Jacob had somehow maintained his composure while the enemy troops killed his animals and ate his food. However, when he learned that he had been robbed, Forney grabbed his gun and rushed up the basement steps to kill Cornwallis. His wife interceded and stopped him before a showdown took place.

At two o’clock in the morning on February 1, Cornwallis put his army on the march toward the Catawba, and Jacob Forney was left with a devastated plantation. Historian Cyrus L. Hunter, himself the son of a Revolutionary War hero, Dr. Humphrey Hunter, noted that “few persons during the war suffered heavier losses than Jacob Forney.”

Forney soon learned that his misery had been occasioned by a Tory neighbor, a Mr. Deck, who had directed Cornwallis to the plantation. Deck was promptly warned that he must leave the area or Forney would kill him. Deck did not heed the warning, so Forney hunted him down and captured him. Touched by Deck’s pleas for his life, Forney spared him upon his promise that he would leave and never return.

From the bridge at the intersection of S.R. 1383 and N.C. 73, drive north on S.R. 1383 for 0.4 mile. There is a large rock on the northern side of the house to the left of the road. (Note that there are large rocks on either side of this house.) This rock, covered with moss and lichen, is known as “Cornwallis’s Tea Table,” since the British general enjoyed afternoon tea here. His soldiers used the stone table to slaughter Jacob Forney’s animals.

Return to the junction with N.C. 73. Go east on N.C. 73 for 2.4 miles to N.C. 16. Turn left, drive north for 2.4 miles to S.R. 1349, turn right, and drive east for 3.7 miles to Beatties Ford Access Area, located near where the road terminates at the Catawba River. Park in the public lot. This stop provides an outstanding view of the river near one of its most historic fords.

Named for John Beatty, considered the first permanent white settler west of the Catawba, the ford assumed strategic value in the last year of the Revolution. Cornwallis marched his army here on January 28, 1781, only to find the rain-swollen river too treacherous to cross. Four days later, he resolved to cross at Cowan’s Ford, located 4 miles south. In preparation for crossing, the British commander dispatched Lieutenant Colonel James Webster and some artillery pieces to feint a major British crossing at Beatties Ford in the predawn hours on February 1.

Webster arrayed his soldiers along the riverbank. For thirty minutes, while the bulk of the British army was beginning to attempt a crossing at Cowan’s Ford, the early-morning stillness was broken by Webster’s booming cannon.

Opposing Webster on the eastern side of the river at Beatties Ford was a small contingent of General William Lee Davidson’s militia. Davidson had been assigned the unenviable task of preventing or at least impeding the crossing, in order to give Greene and Morgan time to escape with the haggard remnants of the American army in the South.

As you gaze across to the eastern bank, you can see the spot where Davidson plotted the defense of the Catawba with Greene, Morgan, Colonel William Washington, Colonel William Polk, and Captain Joseph Graham on the afternoon of January 31. While seated on a log at Beatties Ford, the six men devised the strategy to be used to stop Cornwallis. Within twenty minutes, Greene and Morgan departed to push the American army east, out of harm’s way. Left behind were Davidson, Polk, and Graham, who on the morrow would lead eight hundred militiamen against twenty-five hundred British regulars.

From the access area, you can look downriver and see Duke Energy’s McGuire Nuclear Plant. That facility is located near Cowan’s Ford, where Davidson ultimately battled Cornwallis for control of the Catawba on the morning of February 1.

Retrace S.R. 1349 to N.C. 16. Turn left and proceed south for 3.3 miles to unpaved Ben McLean Lane. Turn right onto Ben McLean Lane and park on the shoulder. Walk into the forest on the southern side of the road, where a rock wall borders the ancient cemetery that once belonged to White Haven Episcopal Church. One prominent grave here, marked by the Sons of the American Revolution, is that of Peter Eddleman.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1762, Eddleman moved with his family to North Carolina when he was a child. He grew up in the vicinity of Machpelah Presbyterian Church. As a teenager, Eddleman took up arms with the Patriot forces in the fight for independence. He participated in the pivotal American victories at Cowpens and Kings Mountain. Among the American troops who proudly stood at attention when General Benjamin Lincoln accepted the sword of surrender from General Charles O’Hara at Yorktown on October 19, 1781, was nineteen-year-old Peter Eddleman.

He returned home after the war and became a renowned furniture maker. He married for the first time in 1830, at the age of sixty-eight. Two sons were born of the marriage.

Return to N.C. 16, turn left, and drive north for 1 mile to N.C. 73. Turn right and proceed east for 2.5 miles to the public parking area on the left side of the road at Cowan’s Ford Dam. A state historical marker here chronicles the history of the region.

Constructed in the early 1960s, the immense dam towers above the very site where Cornwallis crossed the Catawba while doing battle with American militia in the frigid early-morning hours of February 1, 1781. At that time, the river was a quarter-mile wide here at Cowan’s Ford.

Countless stories of gallantry were played out on that fateful morning. Among the militiamen who had taken a defensive position with Davidson’s forces on the far side of the river the night before the battle was Robert Beatty, a crippled man who taught at a school downriver near Tuckaseegee Ford. Upon learning that British soldiers were scouring the area to capture local boys for service as musicians, Beatty had dismissed his pupils, picked up his rifle, and limped away to join the fight.

When the British began to attempt their crossing, bullets flew. Beatty was stationed in a group of thirty Lincoln County volunteers that included sixteen-year-old Robert Henry, already a veteran of the Battle of Kings Mountain. Suddenly, a British bullet struck the lame schoolmaster. As he slumped to the ground mortally wounded, he proclaimed to young Henry, “It’s time to run, Bob!”

The Redcoats faced a terrific resistance from Davidson’s marksmen. They also had to deal with the swirling waters of the mighty Catawba. Mounted on his spirited charger, General Cornwallis was led into the river by a local Tory guide, Frederick Hager. Cornwallis’s horse was badly wounded during the crossing but managed to carry its rider to the eastern riverbank, where it dropped dead. When General O’Hara plunged into the raging waters, his mount rolled over, and horse and rider were swept downriver for forty yards. General Leslie encountered the same difficulty.

British foot soldiers lashed themselves together in an effort to gain stability in the dangerous waters. Even then, they were forced to contend with a river bottom that was rocky and filled with holes. Patriot bullets whizzed by the heads of the first Redcoats to reach the opposite shore.

General Davidson was shot from his horse. He was one of the three Americans killed in the battle. British losses were substantially higher: thirty-one killed (including a colonel) and thirty-five wounded.

After several hours of ferocious fighting, the gallant stand at Cowan’s Ford was over. The American militiamen fled as seemingly endless waves of Redcoats poured out of the river. Cornwallis, who was now set to put the heat on Greene, later offered “thanks to the brigade of Guards for their cool and determined bravery in the passage of the Catawba, while rushing through that long and difficult ford under a galling fire.”

Among the items lost by the crossing army was an elegant beaver cap. It was found floating in the river 10 miles downstream the day after the battle. Inside the fashionable piece were the words, “Property of Josiah Martin, Governor.” The last Royal governor of North Carolina had been among the distinguished personages in the British entourage as it crossed the river. In his correspondence following the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, Cornwallis noted that Martin had accompanied him throughout the North Carolina campaign in an attempt to render assistance to the British cause. He said that Martin bore the hardships of camp and the march with cheer.