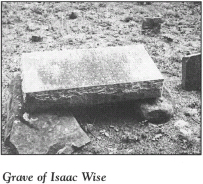

This tour begins at Forest City in Rutherford County and makes its way through Burke and Caldwell Counties before ending at Lookout Shoals in Catawba County. Among the highlights are Gilbert Town, the site of Biggerstaffs Old Fields, Brittain Presbyterian Church, the Battle of Cane Creek, Quaker Meadows, Fort Defiance, the story of Isaac Wise, the Catawba County Museum of History, the graves of Francis McCorkle and Betsy Brandon McCorkle, and the story of Sam and Charity Brown.

Total mileage:

approximately 206 miles.

This tour covers a four-county area lying at the edge of the mountains in southwestern North Carolina. In the two decades preceding the Revolutionary War, white settlers put down stakes here along the fertile banks of the many rivers and creeks that flow down from the mountains. When the fight for independence came, the foothills settlements provided a number of heroes and heroines. While the tour area was for the most part spared as a battleground, it served as a staging ground for action that took place in counties to the east.

The tour begins on U.S. 74 Business/U.S. 221A in the Rutherford County community of Forest City. Follow the highway west for 5.6 miles to N.C. 108. Turn left and drive 3.6 miles to Mountain Creek. Set in the wilderness along the eastern banks of this tributary of the Broad River is the Miller-Twitty graveyard. Buried here are three family members who were staunch Patriots during the Revolution.

William Twitty, a militia captain, was killed in 1775 by Indians while blazing a trail to Kentucky with Daniel Boone. His daughter, Susan Twitty Graham, was born in 1763 in a log cabin located near her final resting place. Susan was only seventeen when she gained enduring fame for her exploits at Graham’s Fort in Cleveland County. (For more information, see The Tide Turns Tour, pages 251–53.)

Interred beside the heroine is her first husband, John Miller (1758–1807). A participant in a number of Revolutionary War engagements, Miller later served in the North Carolina General Assembly.

Near the graves of the couple is that of Susan’s older brother, William. At nineteen, William was already an experienced soldier when he took part in the Battle of Kings Mountain. During the ferocious fighting there, young Twitty was distressed when one of his best friends was shot down by his side. Noticing powder smoke at a nearby tree and anxious to exact revenge for his fallen comrade, he waited with a loaded musket until a head poked out from the tree. Fire flashed from Twitty’s weapon, and the Tory fell dead. When the battle was over, he walked to the tree and found the soldier he had slain. The dead man was one of Twitty’s neighbors, a noted Loyalist.

Continue west on N.C. 108 for 1.6 miles to the bridge over the Broad River. Located near this stop was Denard’s Ford, the site where Patrick Ferguson and his army camped on October 1, 1780.

Throughout much of September, Ferguson and his force of over a thousand men had operated in the back country of North and South Carolina in a cat-and-mouse hunt for area Patriots, many of whom were in hiding. These mop-up operations were designed to pave the way for the conquest of North Carolina by Cornwallis, who entered Charlotte with his army on September 25.

While camped at Gilbert Town (located 8 miles north of Denard’s Ford) on September 30, Ferguson received the alarming news that a sizable frontier army was coming over the mountains in pursuit of him. He had two choices: he could march east to unite with Cornwallis or he could make a stand against the mountaineers and put an end to resistance in the area once and for all. Ferguson chose the latter course. While the bulk of his soldiers made their way to the river at the current tour stop, he dispatched messengers to Cornwallis with pleas for assistance.

In an effort to spread fear before the coming fight, Ferguson issued an inflammatory ultimatum to the people of the foothills while he was encamped at Denard’s Ford:

I say if you want to be pinioned, robbed, and murdered, and see your wives and daughters, in four days, abused by the dregs of mankind—in short, if you wish or deserve to live, and bear the name of men grasp your arms in a moment and run to camp.

The Back Water men have crossed the mountains; McDowell, Hampton, Shelby, and Cleveland are at their head, so that you know what you have to depend upon. If you chose to be pissed upon by a set of mongrels, say so at once, and let your women turn their backs upon you and look out for real men to protect them.

Ferguson’s appeal backfired, as he would tragically learn six days later when he made his fateful stand at Kings Mountain.

Turn around at the bridge and retrace N.C. 108, following it to the junction with U.S. 221 (Main Street) in Rutherfordton. Turn left onto U.S. 221 and proceed through the heart of the seat of Rutherford County. Both city and county were named in honor of General Griffith Rutherford, one of North Carolina’s greatest Revolutionary War heroes. (For information on Rutherford, see The Yadkin River Tour, pages 296–98.)

After approximately 1.6 miles on U.S. 221, you’ll reach a state historical marker calling attention to Gilbert Town, the county seat from 1781 to 1785. In the days leading up to the showdown at Kings Mountain, both Ferguson’s army and the Overmountain Men camped here.

To see the site of Gilbert Town, continue north on U.S. 221 for 1.2 miles to S.R. 1535 (Broyhill Road). Turn right, go 1.5 miles to S.R. 1520 (Rock Road), turn left, and drive 0.6 mile to a crude wooden sign in a field on the right side of the road.

This sign marks the site of the abandoned county seat. The old, two-story frame house on the opposite side of the road—the McKinney-Twitty House—occasionally flies the colors of the two nations whose soldiers camped here within days of each other in 1780. Other than the homemade sign and the old house, there is nothing in this green, rolling farm country to bear testimony that here was the apogee of Patrick Ferguson’s campaign in western North Carolina.

According to tradition, the McKinney-Twitty House contains boards stained with the blood of Ferguson’s soldiers. When Ferguson broke camp here in late September, he was forced to leave behind one his most trusted lieutenants, Major James Dunlap. Suffering from a severe wound sustained in the fighting at nearby Cane Creek (a subsequent stop on this tour stop), Dunlap remained behind at the home of William Gilbert, which stood across the road from the existing dwelling.

Although he was confident that the Gilbert family, which was loyal to King George III, would properly care for the injured officer, Ferguson assigned one of his soldiers to wait on Dunlap. Soon after Ferguson departed Gilbert Town, that soldier was murdered when he antagonized one of Gilbert’s slaves. According to historian Lyman C. Draper, this incident was an “ill-omen” of another tragedy soon to follow.

Three Patriots hellbent on exacting revenge for recent cruelties perpetrated by Major Dunlap in Spartanburg, South Carolina, appeared at the Gilbert residence upon learning that Dunlap was there. They confronted the wounded officer and shot him. Tradition maintains that Dunlap died and was buried on nearby Ferguson Hill. Draper maintained that he may have survived the wound and recovered to fight another day.

At any rate, boards from the Gilbert home stained with Dunlap’s blood can be seen in the existing house. Former occupants of the dwelling maintain that the ghost of the officer continues to haunt the place.

Four days after Ferguson and his army departed Gilbert Town, the Overmountain Men, in hot pursuit of the Loyalists, set up camp at almost the same site. While they were here, a letter signed by Benjamin Cleveland, Isaac Shelby, John Sevier, Andrew Hampton, William Campbell, and Joseph Winston was dispatched to Major General Horatio Gates, then the commander of the American army in the South. The officers requested that General William Lee Davidson or General Daniel Morgan be appointed to command the mountain soldiers. Proud of their efforts but anxious for leadership, the militia leaders noted, “We have collected at this place about 1500 good men, drawn from the Counties of Surry, Wilkes, Burke, Washington, and Sullivan Counties in this State, and Washington County in Virginia. … As we have at this time called out our Militia … with the view of Expelling the Enemy out of this part of the Country, we think such a body of men worthy of your attention.”

Time did not allow Gates to act upon the request. At Kings Mountain three days after the letter was dispatched, the Americans struck a defining blow in the fight for independence. Clarence Griffin, eminent historian of western North Carolina, captured the mood of the American encampment at the current tour stop: “Never was the war cry of the ancient Romans more ceaseless and determined that Carthage must be destroyed than that of the mountaineers—to catch and destroy Ferguson.”

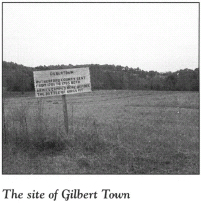

Turn around at Gilbert Town and follow S.R. 1520 south for 0.7 mile to U.S. 64. Go left on U.S. 64 and proceed north for 3.2 miles to S.R. 1510. Turn right, drive 1.6 miles east to S.R. 1538 (Whiteside Road), turn left, and travel 4.7 miles to a historical marker at the site of Biggerstaffs (or Bickerstaffs) Old Fields. Well into the twentieth century, a storied oak tree long known as “the Gallows Oak” stood near this site.

Less than a week after the Battle of Kings Mountain, the victorious Americans camped here for three days. During their stay, word of the recent hangings of eleven Patriots at the community of Ninety-Six, South Carolina, reached the campsite. That news spelled doom for some of the Tory prisoners captured at Kings Mountain, who were being held by the mountaineers.

In order to retaliate for the South Carolina executions, a group of Patriot officers lodged a complaint with Colonel William Campbell. They informed their commander that a number of the Tory prisoners were guilty of lawless acts including murder and house burning. In accordance with North Carolina law, Campbell ordered a court-martial to inquire into the complaint. Big Ben Cleveland, never one to miss an opportunity to hang a Tory, was one of the presiding justices of the wilderness court. By early evening on October 14, the trials were completed, Cleveland and his fellow magistrates having pronounced the death sentence thirty-two times.

The giant oak was selected for the gallows, and the condemned men were paraded to the site through a forest illuminated only by the flames of hundreds of pine-knot torches held high by the victorious Patriots. The Tories were hanged in groups of three; included in the first trio was Colonel Ambrose Mills. During the initial executions, several prisoners awaiting their trip to the gallows managed to escape. After nine men had died, Colonel Isaac Shelby, sickened by the spectacle, put a stop to the hangings. The other condemned men were pardoned.

Turn around near the historical marker and drive 2 miles south on S.R. 1538 to S.R. 1007. Turn right, follow S.R. 1007 north for 3.5 miles to U.S. 64, and turn left again. After 0.1 mile, you will pass a historical marker for Fort McGaughey, which was erected during the Revolutionary War.

Continue south on U.S. 64 for 0.1 mile to Brittain Presbyterian Church, located on the left. A state historical marker stands alongside the road.

Organized in 1768, Brittain Presbyterian is one of the oldest churches in western North Carolina. It began in a log building that stood at the foot of a hill to the rear of the existing structure. The historic church cemetery grew from a burial ground already here when the church was established.

Because the church site was on land that belonged to Great Britain, it was originally given the name Little Britain. When the Revolution came, that name caused consternation among members who sided with the American cause. Consequently, the Mecklenburg Presbytery granted permission to add a t to the spelling to distinguish it from the mother country. Some historians believe that the additional t was a compromise between independence-minded members, who wanted to change the name altogether, and Loyalist members, who wanted no change.

The Overmountain Men camped near the church on their march home after the victory at Kings Mountain. They sadly laid to rest the body of Lieutenant Thomas McCollough in the cemetery here. A Virginian who died on October 12 from wounds sustained at Kings Mountain, McCollough is one of seventy-five Revolutionary War soldiers in the ancient burial ground, which was restored during the church’s bicentennial celebration in 1968. Many of the graves have D.A.R. markers or identifiable stones.

From the church, proceed south on U.S. 64 for 1.9 miles to the historical marker for Colonel John Walker, located on the left just north of the bridge over the Second Broad River.

Born in Delaware to Irish immigrants, Walker (1728–95) was an intrepid Indian fighter who settled in Lincoln County around 1755. He moved to Rutherford County prior to the Revolution. An ardent Patriot, Walker had six sons, all of whom fought for American independence, five as commissioned officers. Walker’s home, located near the current tour stop, was the site of the first court of Rutherford County.

Turn around near the historical marker and proceed north on U.S. 64 for 6.9 miles to S.R. 1700. On October 3, 1780, the Overmountain Men camped beneath Marlin’s Knob beside Cane Creek, which parallels U.S. 64 on its route north into McDowell County.

On the day of their encampment here, the American colonels assembled their soldiers, advised them of the task that lay ahead, and offered the opportunity for men to withdraw from the expedition. Colonel Shelby then stood before the assembled Patriots, dressed in their back-country attire, and spoke to them in the plain language to which they were accustomed: “You have all been informed of the offer. You who desire to decline it, well, when the word is given, march three steps to the rear, and stand, prior to which a few more minutes will be granted you for consideration.”

In one of the most dramatic moments of the war in North Carolina, the order was then given. Not a man budged. Visibly moved by the determination and loyalty of the soldiers, Shelby told them, “I am heartily glad to see you to a man resolve to meet and fight your country’s foes. When we encounter the enemy, don’t wait for the word of command. Let each one of you be your own officer, and do the very best you can, taking every care you can of yourselves, and availing yourselves of every advantage that chance may throw your way.”

Continue north on U.S. 64. After 1.3 miles, you will cross into the southeastern corner of McDowell County. It is another 1.4 miles to a series of bridges over Cane Creek. A state historical marker notes that the Battle of Cane Creek took place here.

At nearby Cowan’s Ford on Cane Creek, Colonel Charles McDowell of Burke County and his American militiamen ambushed Patrick Ferguson’s soldiers on September 12, 1780. This skirmish served as a prelude to the pivotal battle at Kings Mountain. Caught off guard by the sudden attack, the Loyalists suffered a number of casualties before they regrouped and chased McDowell’s men west into the mountains.

As a result of his modest victory here, Ferguson came to the erroneous conclusion that serious resistance to the Crown in western North Carolina was at an end. He didn’t know that McDowell was biding his time until the arrival of the mountaineers he had called to assist him.

In the dense undergrowth on the virtually inaccessible creek banks are fieldstones marking the graves of nine of Ferguson’s soldiers who fell here.

Continue north on U.S. 64. It is 2.8 miles to the Burke County line. Formed in 1777, the county takes its name from Dr. Thomas Burke (1747–83), a member of the Continental Congress and the governor of North Carolina during a portion of the Revolutionary War. (For more information on Burke, see The Regulator Tour, pages 408–10.)

Pilot Mountain rises approximately 0.8 mile north of the county line. At the foot of this 2,050-foot prominence stood the early log house of Captain William Moore, the famous Indian fighter of the Revolutionary War era who subsequently became the first white settler west of the French Broad River. (For more information about Moore, see The Frontier Tour, pages 224–25.)

The Overmountain Men camped just south of Pilot Mountain at Bedford’s Hill on October 1 and 2, 1780. It was here that they prevailed upon the unpopular Charles McDowell, their senior colonel, to step aside as commander. His reluctant replacement was Colonel William Campbell. According to Lyman C. Draper, the meticulous historian of the campaign of the Overmountain Men, Colonel McDowell “had the good of his country at heart more than any title to command, [and] submitted gracefully to what was done.” Anxious to ensure the success of the expedition against Ferguson, McDowell left the encampment en route to a conference with General Horatio Gates. He hoped to persuade the commander of the American army in the South to provide a general officer for the Overmountain Men. As a result, McDowell was not on hand for the victory at Kings Mountain.

Proceed northeast on U.S. 64 for 12.9 miles to U.S. 70 Business (Union Street) in Morganton.

The seat of Burke County, Morganton was established in 1777 as Morgansborough. It was named to honor General Daniel Morgan (1736–1802), the farmer-turned-soldier who masterminded the Patriot victory at Cowpens, South Carolina, in 1780 and aided Nathanael Greene on his successful retreat through the North Carolina Piedmont. After the war, when Morgan was asked what role he had played in the struggle for independence, he responded simply, “Fought everywhere; surrendered nowhere.”

Turn right on U.S. 70 Business and follow it into downtown Morganton to the Old Burke County Courthouse, located at the town square. Built in 1833, the two-story building surmounted by a cupola now houses the Burke County Museum of History. The museum offers artifacts from the long history of Burke, including some from the Revolutionary War era.

It was in the log courthouse that once stood on the site of the present museum that Revolutionary War hero John Sevier was brought to trial in 1788. Sevier was charged with treason for his role in attempting to establish the State of Franklin in western North Carolina. He walked out of the courthouse in the middle of the trial and was never convicted. As a member of the North Carolina General Assembly, he subsequently voted for legislation that pardoned himself. Ultimately, he got his new state, Tennessee, and was elected its first governor.

You will reach a junction with N.C. 181 on the northern side of the Old Burke County Courthouse. Proceed northwest on N.C. 181 for 0.7 mile to N.C. 126. Near the intersection stands a historical marker for Swan Ponds, the plantation of Revolutionary War Patriot and statesman Waightstill Avery.

To see the estate, turn left on N.C. 126, drive west for 2.4 miles, turn left on S.R. 1222, and follow it to its terminus at Swan Ponds. Neither the home nor the plantation grounds is open to the public.

It was during the Revolution that Waightstill Avery (1741–1821) established a thirteen-thousand-acre plantation at this site. A portion of the property has remained in the Avery family ever since that time.

Born in Connecticut and educated at Princeton, Avery came to Edenton, North Carolina, as a young attorney in 1769, There, he became associated with Joseph Hewes and James Iredell. His long career as a legal scholar and jurist began in 1772, when he was appointed by the Crown as attorney general for the colony.

As tensions with Great Britain mounted, Avery was an outspoken advocate for independence. After signing the Mecklenburg Resolves in 1775, he served in the Provincial Congresses that set up the framework for the government of the independent state of North Carolina. In November 1776, he was one of the prime movers in the final Provincial Congress at Halifax, which produced the first North Carolina Constitution. According to Governor David Lowry Swain, Avery’s handwriting appeared in the constitution more often than that of any other member of the committee that drafted the document. When the first state legislature met at New Bern in 1777, Avery was selected North Carolina’s first attorney general. During the British occupation of Charlotte in 1780, Cornwallis ordered Avery’s office burned, a punishment he inflicted only upon “the most foul” Patriots.

Until he was well into his seventies, Avery continued to practice law throughout North Carolina and Tennessee. On one occasion, he engaged in a heated courtroom exchange with a young lawyer who had served in the Revolution as a teenager. Prior to that time, Avery and Andrew Jackson had enjoyed an amicable relationship, indulging in horse racing and cock fighting at Quaker Meadows in Burke County; among their mutual friends was Davy Crockett. But when Jackson, ever the prankster, invaded Avery’s saddlebag to substitute a slab of bacon for Bacons Abridgement of the Law, Avery found himself the subject of courtroom jest when he sought to cite a legal precedent from the book-turned-meat. As a result of the humiliating experience, Avery challenged Jackson to a duel.

Both men survived the battle of pistols and parted friends. Avery later recounted that he allowed Jackson to fire first, with no effect. Avery then discharged his pistol into the air, approached Jackson, and lectured the future president “very much in the style a father would use in lecturing a son.”

The existing plantation house at Swan Ponds was built in 1830 by Avery’s only son, Isaac. Brick from the original home constructed by Waightstill Avery was incorporated into the dairy house.

Return to the junction of N.C. 126 and N.C. 181, where you’ll see a state historical marker for Quaker Meadows, an area on the outskirts of Morganton steeped in Revolutionary War history. It received its name in 1752, when Moravian bishop A. G. Spangenberg passed through the region and was mistaken for a Quaker by the Indians. This grassy area in west-central Burke County was the stage for some of the most dramatic events leading up to the Battle of Kings Mountain.

Drive west on N.C. 181 for 0.4 mile to St. Mary’s Church Road. Turn right and go 0.2 mile to the historic house known as Quaker Meadows.

Constructed in 1812, this two-story brick home is the oldest structure in Burke County. It was built by Charles McDowell on the site of the house where his father and uncle, Charles and Joseph, had grown up. Since 1986, the house has been owned by the Historic Burke Foundation, which is in the process of restoring the historic dwelling.

Brothers Charles and Joseph McDowell were militia officers from the beginning to the end of the Revolution. Serving together for much of the war, they participated in Griffith Rutherford’s campaign against the Cherokees in 1776 and fought in the Battle of Ramsour’s Mill on June 20, 1780. But their signal contribution to the American war effort came following that Lincoln County battle.

To counter the incursions of Patrick Ferguson’s Loyalists into western North Carolina during the summer of 1780, the McDowell brothers called for the assistance of the Overmountain Men. In response to their plea, soldiers from all over the mountains assembled at Quaker Meadows on September 30, 1780. Joining the expedition at this site were Benjamin Cleveland, William Lenoir, Joseph Winston, and the men under their commands.

Return to N.C. 181, turn left, and proceed 0.1 mile to Bost Road. Turn left into the parking lot of the restaurant located on the left side of the junction.

Here stands a D.A.R. marker for the Council Oak, a local landmark until it was destroyed by a storm many years after the war. The mighty oak sheltered the council of war among the McDowells and the other commanders. From their deliberations came the plan that resulted in the devastating blow dealt to Ferguson a week later at Kings Mountain.

Return to the junction of N.C. 181 and N.C. 126. To see the McDowell burial ground, known as Quaker Meadows Cemetery, turn right on N.C. 126, drive south for 0.3 mile to Sam Wall Road, turn right, and proceed 0.1 mile to Brandston Drive. Turn right on Brandston and follow it to its terminus at the cemetery.

Located in a majestic setting on a hill overlooking Morganton, Quaker Meadows Cemetery is one of the earliest identified sites associated with white settlement in the western part of the state.

Of the fifty-three marked graves, the oldest is that of David McDowell, the first permanent settler in the area. He died in 1767.

Colonel Charles McDowell is among the other family members interred here. For him, the extraordinary Patriot victory at Kings Mountain was a bittersweet event. It was McDowell who put together the mountaineer army that won the battle, yet he was not on the field to share in the victory. Nonetheless, he has since received his due. As distinguished North Carolina jurist and historian David Schenck noted, “The brothers, Charles and Joseph McDowell of Quaker Meadows, and … their no less gallant cousin, Joseph McDowell, of Pleasant Gardens … are due more credit and honor for the victory of Kings Mountain than … any other leaders who participated in that decisive wonderful battle.”

Interred beside Colonel McDowell is his wife, Grace Greenlee Bowman McDowell, one of the most noted wartime heroines of western North Carolina.

Grace’s first husband was John Bowman. As the commander of a militia company, Captain Bowman was away from his Burke County home for extended periods during the war. In his absence, Grace proved a thorn in the side of Ferguson’s operations in the North Carolina foothills. On one occasion, Loyalist soldiers made off with some of the Bowmans’ horses. Grace forthwith made her way alone to Ferguson’s camp some miles away, demanded the return of the animals, and promptly rode home with them. On another occasion, a group of Tories raided the Bowman residence while Grace was away. Upon her return, she immediately gave chase, caught up with the culprits, and, at rifle point, forced them to surrender the items they had taken.

When word reached Grace that Captain Bowman had been badly wounded at the Battle of Ramsour’s Mill, she climbed upon the family’s speediest mount, her child of fifteen months in her arms. She galloped down lonely roads on the 40-mile ride to Lincoln County, reaching her husband’s side just before he died on the battlefield, where he was buried.

She married Charles McDowell near the close of the Revolution.

Buried in an unmarked grave beside Charles and Grace is Joseph McDowell. His postwar public career in helping to build the new state and nation was impressive. Like his brother, he was a delegate to both Constitutional Conventions. Unlike Charles, however, Joseph was an adamant anti-Federalist. Nonetheless, after the United States Constitution was ratified by North Carolina, he served two terms in Congress.

Alexander and Sarah Ervin—another married couple of Revolutionary War renown—are buried here.

During the war, Alexander Ervin (1750–1830) served as a captain under Joseph McDowell. Once the hostilities ended, he acted as a military auditor in the North Carolina foothills. His books remain one of the best sources on the Revolutionary War service of the men of western North Carolina.

Ervin’s first wife, Sarah, died as a result of a wound sustained during an act of wartime bravery. When a Tory drew his sword to assault a wounded Patriot under her care, Sarah stepped between the two men and received the sword blow meant for the American soldier.

Ervin subsequently married Margaret Crawford Patton, whom he met while delivering the riderless horse and personal effects of her late husband, who had died at the Battle of Ramsour’s Mill.

Return to the junction of N.C. 126 and N.C. 181. Turn right and drive east on N.C. 181 to U.S. 70 Business in downtown Morganton. Turn left, go one block north, and turn left on N.C. 18. Drive north for 3 miles to S.R. 1423. Turn left, travel 2.5 miles to S.R. 1440, and turn left again. Cedar Grove Plantation is 0.5 mile ahead.

Not open to the public but visible from the highway, the two-story Federal-style house located here was built by Jacob Forney, Jr. (1754–1840), in 1825. Forney was one of three Lincoln County brothers who fought for the American cause. His father, too old to serve in the Patriot army, attempted to kill Cornwallis when the British commander was quartered at the family’s plantation in Lincoln County. (For more information, see The Tide Turns Tour, pages 281–82.)

Jacob Forney, Jr., settled near the current tour stop in 1780. He is buried in a marked grave in the nearby family cemetery.

Return to the junction with S.R. 1423. Turn left and proceed 6.9 miles northwest to S.R. 1405 at the community of Joy. Turn right and follow S.R. 1405 northeast for 3.2 miles to the Caldwell County line. At the county line, the road changes to S.R. 1335. Continue northeast for 1.1 miles to the community of Adako, where S.R. 1335 becomes S.R. 1337. Proceed 1.6 miles on S.R. 1337.

The Johns River is visible on the right side of the road. Martin Davenport, one of Caldwell County’s greatest Revolutionary War heroes, lived along this 32-mile watercourse, which flows southward through the western portion of the county.

Because of his distinguished service for the Patriot cause, Davenport was a wanted man among area Loyalists. On one occasion, John McFall led a group of Burke County Tories to Davenport’s home. Dismayed to learn from Mrs. Davenport that her husband was away, McFall demanded that she prepare breakfast for the Tories. He also directed the Davenports’ ten-year-old son, William (who would later kill the last elk ever seen in North Carolina), to fetch some corn from the barn and feed the Tories’ horses.

After McFall finished his meal, he came out of the house and asked William Davenport in a harsh tone why the horses had not been fed. With all the spirit and boldness of his Patriot father, the lad told McFall, “If you want your horses fed, feed them yourself.” McFall was outraged. He immediately cut a switch and thrashed the boy.

At the court-martial proceedings at Biggerstaffs Old Fields in Rutherford County following the Battle of Kings Mountain, one of the Tory captives brought before the tribunal was John McFall. When the case against McFall was presented, “Quaker Meadows” Joseph McDowell reasoned that the Tory’s conduct was not of such a heinous nature that it merited death. Consequently, he recommended leniency. But Ben Cleveland, one of the judges of the tribunal, thought differently. He snapped, “That man, McFall, went to the house of Martin Davenport, one of my best soldiers, when he was away from home, fighting for his country, insulted his wife, and whipped his child, and no such man ought to be allowed to live.”

Cleveland had his way, and McFall paid for the whipping with his life. He and his eight fellow Tory victims were left suspended from the Gallows Oak after they were executed.

Continue northeast on S.R. 1337 for 1.6 miles to N.C. 90 at Collettsville. Follow N.C. 90 east for 4.1 miles to Mulberry Creek Road at the community of Olivet. Turn left, drive north for 1.1 miles to Roby Martin Road, turn right, and go 3.9 miles to U.S. 321. Turn right, go south for 0.9 mile to N.C. 268, turn left, and drive east for 1 mile to the bridge over the Yadkin River, where a state historical marker notes that Fort Defiance, the home of Revolutionary War luminary William Lenoir, is located nearby.

To visit the site, continue east on N.C. 268 for 4.8 miles to S.R. 1513 and turn right. Fort Defiance, a red, two-story frame dwelling, is on the right just after the turn. The restored home is open to the public for tours on a limited basis.

William Lenoir (1751–1839) began constructing the house in 1788 near a stockade that stood nearby to afford early settlers protection against Indians. A native of Virginia, Lenoir grew up in Edgecombe County, North Carolina. In 1775, on the eve of the Revolution, he moved with his wife and small child from Halifax to Wilkesboro, where he could better use his skills as a surveyor.

Lenoir proved himself an invaluable militia officer during the fight for independence. He first caught the eye of his superiors as a young lieutenant in Rutherford’s campaign against the Cherokees. As a captain at the Battle of Kings Mountain, he was wounded in the thick of the fight. Lenoir later described the experience this way: “I received a slight wound in my side, and another in my left arm, and after that, a bullet went through my hair about where it was tied, and my clothes were cut in several places.” A year later, at Pyle’s Massacre on the Haw River (see The Regulator Tour, pages 400–402), Lenoir escaped injury even though his horse was shot from under him and his sword was broken.

Following the war, he served effectively in the state legislature. However, his numerous attempts at higher offices—United States senator in 1789, governor of North Carolina in 1792 and 1805, and United States representative in 1803 and 1806—proved unsuccessful because Lenoir did not believe in electioneering. He simply refused to campaign for office.

Located at the edge of a field near the house is the family cemetery, where Lenoir is buried. The Masonic symbol on his tombstone convinced Union soldiers to spare Fort Defiance from the torch during the Civil War. The original stockade stood on the site of the cemetery.

When Lenoir’s home was acquired by the Caldwell County Historical Society in 1965, a number of important period furnishings and artifacts were included in the purchase. Many of these treasures, including Lenoir’s eyeglasses, are on display in the house.

Retrace your route to U.S. 321 and turn left. Proceed south for 6.1 miles to N.C. 18 Business/N.C. 90 at Lenoir, the seat of Caldwell County. The town was named for the builder of Fort Defiance.

Turn right on N.C. 18 Business/N.C. 90 and follow it for 0.5 mile to Main Street in downtown Lenoir. Turn left, proceed 0.2 mile to College Avenue, turn right, then turn left on Vaiden Street. It is 0.1 mile to the Caldwell County Heritage Museum.

Located in the last extant building of Davenport College—a nineteenth-century girls’ school named for the family of Martin Davenport—the museum showcases area history from the time prior to the arrival of the first white settlers. Its displays and exhibits provide a wealth of information about the involvement of the area and its residents in the Revolution.

Return to the junction with College Avenue. Turn left, drive 0.2 mile to Willow Street, turn right, and go one block to Harper Avenue.

Fort Grider once stood on the left side of Willow at this junction. An outpost built by Patriots early in the Revolution for protection against Indians, it stood on land owned by Frederick Grider, the man for whom it was named. A monument placed here by the D.A.R. in 1930 marks the site where North Carolina soldiers camped en route to the Battle of Kings Mountain. The large, multistory building now covering the site once housed Lenoir High School.

Turn right on Harper Avenue, drive 0.8 mile to U.S. 321, and turn right again. It is 14.1 miles to the Catawba County line at the Catawba River. From the river, follow U.S. 321 south for 2.9 miles to U.S. 64/U.S. 70 in Hickory. Proceed east on U.S. 64/U.S. 70 for 5.6 miles to St. Pauls Church Road. Turn right, drive 1.8 miles to Old Conover-Startown Road, and turn right again. After 0.1 mile, you’ll see Old St. Paul’s Church on the right.

Organized in 1759, Old St. Paul’s began as a church for people of the Lutheran and Reformed faiths. The tall, two-story sanctuary at the current stop was constructed in 1818 of logs from the original church, which stood nearby. The charter members of Old St. Paul’s were the area’s earliest settlers. They took up residence along the banks of the nearby South Fork (Catawba) River in the early 1750s.

Two decades later, when the call went out for volunteers to fight for American independence, many of the male members of the church answered. A number of graves of Revolutionary War veterans are located in the ancient burial ground adjacent to the church. Among the soldiers laid to rest here was John Wilfong, Sr. (1762–1838). A teenager during the war, Wilfong holds the distinction of being the only man from what is now Catawba County to serve as a soldier in the Continental Army. But the height of the war in western North Carolina saw Wilfong serving as a militiaman. In 1780, he was involved in some of the fiercest fighting at Kings Mountain, where he was badly wounded in the side.

Continue southwest on Old Conover-Startown Road for 1.9 miles to S.R. 1005 (Startown Road). Turn left, drive 0.9 mile to N.C. 10, turn right, and go west for 0.7 mile to S.R. 1146 (Robinson Road). Turn right on S.R. 1146. After 2.6 miles, slow down and look to the left. The field here was the site of the home of Henry Weidner, the first permanent white settler in Catawba County, and the famous Weidner Oak. The ancient tree died in the 1930s, after standing for centuries.

In colonial times, when area settlers faced a constant threat from the Cherokees to the west, Henry Weidner and his family were forced to flee their home on numerous occasions. The oak was located forty feet from the house. When danger from the Cherokees was imminent, a Catawba chief friendly to Weidner would paint the oak bright red. When all was clear, he would paint it white. Thus, when Weidner slipped back home to check on the state of affairs, he could gauge the Indian threat by the color of the tree.

When the Revolutionary War began, settlers along the banks of the South Fork found themselves at odds with each other over their loyalties. It was under the shade of the mighty oak that Henry Weidner, George Wilfong, Conrad Yoder, John Hahn, and several others met to pledge their support for the American cause. That pledge, known as the South Fork Covenant, exposed the Patriots to great danger from their Tory neighbors.

Weidner and his associates used horns to warn of an attack by Tories or Indians. On one occasion, a band of Tory robbers called at the present tour stop to seize the Weidner family’s money. According to contemporary records, the raiders roughed up Henry and “hung him up by the joints.” His wife, Catherine, used a mussel shell to sound the alarm, and a band of Patriot neighbors quickly arrived and gave chase to the Tories.

A similar incident took place nearby when Tory robbers arrived at the home of John Hahn. When Hahn refused to reveal the hiding place of his money, he was seized by the Tories, who “drew him up till he turned blue.” Unsuccessful in their efforts to gain the desired information, the robbers started for the barn to steal horses when they were confronted by Hahn’s two daughters, armed with axes. As soon as the female Patriots told their unwelcome neighbors that they intended to “make sausage” of the first Tory to enter the stable door, the robbers departed as quickly as they had arrived.

In early October 1780, George Wilfong, the father of Continental Army soldier John Wilfong, assembled twenty-five men under the Weidner Oak and then marched them to Kings Mountain, where they suffered heavy casualties as part of “the South Fork Boys.”

Retrace your route to N.C. 10. Turn left and drive 4.2 miles east to U.S.321/N.C. 155. Turn right and go 5.7 miles to downtown Maiden.

After his victory over the impetuous Banastre Tarleton at Cowpens on January 17, 1781, General Daniel Morgan began a retreat to escape the wrath of Cornwallis’s full army. Morgan’s flight took him to Morganton and then to the current tour stop, where he prepared his army to cross the Catawba River and join up with Nathanael Greene’s forces.

In Maiden, follow U.S. 321/N.C. 155 (East Main Street) south through town for 1.1 miles to Providence Mill Road. Turn left and proceed south for 0.8 mile to the old Providence Mill, located on the left. Captain Daniel McKissick, a Patriot militiaman who was seriously wounded just miles away at the Battle of Ramsour’s Mill, once lived near here. He recovered in time to fight several months later at Kings Mountain.

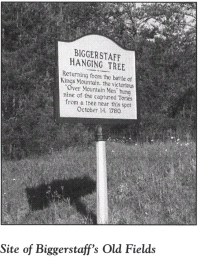

From the mill, continue north on Providence Mill Road for 0.2 mile to Fred Beard Road. Turn left, drive 0.5 mile to Mays Chapel Road, turn left again, and head west for 1.1 miles to U.S. 321/N.C. 155. Turn right and proceed north for 2 miles to Prison Camp Road. Turn right and drive east for 1 mile. At the edge of a forest across a field on the left side of the highway is the old Haas family cemetery. Buried here is Isaac Wise, who was executed nearby in 1776.

According to Catawba County tradition, seventeen-year-old Isaac Wise ignored the Loyalist leanings of his father, Daniel, and many of his neighbors. At the outbreak of the war, he threw his support to the cause of American independence.

A militant band of local Tories captured Wise near the house of Simon Haas, a pioneer who had settled in the vicinity of the current tour stop. The decision was made to hang the young Rebel, but no rope was readily available. One of the Tory leaders, Martin Shuford, raced away on his steed to secure some. In the process, his horse stumbled and threw him. Shuford broke his nose in the fall, after which he was forever known as “Crooked Nose.” (Four years later at the Battle of Ramsour’s Mill, Crooked Nose Shuford gave his life while fighting for the Crown.)

After Wise’s hanging, his body was left dangling from the tree. Simon Haas finally cut the body down and removed it to his home, where his wife used her best linen sheet as a burial shroud.

Wise’s grave is marked by a bronze plaque erected by the Catawba County Historical Association in 1951. The cemetery is on private property, so ask permission from the owner of the nearby farmhouse if you wish to visit the grave.

Return to the junction with U.S. 321/N.C. 155. Turn right and proceed 3.4 miles north to N.C. 10 in Newton, the seat of Catawba County. Turn right, follow N.C. 10 for 0.4 mile to College Avenue, turn left, and proceed three blocks to the Catawba County Museum of History, located on the old courthouse square.

Housed in the former Catawba County Courthouse, the museum has emerged as one of the most attractive and respected county history museums in the state. Among its holdings related to the Revolutionary War are a British officer’s greatcoat (a real redcoat!); a small British ceremonial sword; the worn Bible carried by the Reverend Johann Gottfried Arends, the first Lutheran minister west of the Catawba and a strong supporter of American independence; and the intricately decorated powder horn of Henry Weidner.

On the museum’s well-landscaped grounds is a granite monument dedicated to the memory of Matthias Barringer. Barringer was an early settler in the Newton area. His log house, constructed in 1762 approximately 1.5 miles southeast of the museum, served as the first courthouse in Catawba County. After World War II, it was moved to downtown Newton, restored, and used as a public library and museum until it burned in 1952.

When the colonies embarked upon their fight for independence, Barringer cast his lot with the American cause. A militia captain, he used his plantation as a mustering ground for the company of local soldiers he commanded in Griffith Rutherford’s expedition against the Cherokees.

He and seven of his men were on a scouting expedition in the Quaker Meadows area of Burke County in early July 1776 when they were massacred by a Cherokee war party armed with British rifles. Barringer was the first to fall. He was subsequently scalped.

Local legend has it that Barringer’s wife, back home caring for their two small children, told neighbors on the day of the ambush that she knew her husband had fallen in battle. She said she had heard him groan.

Return to the intersection with N.C. 10. Turn left and drive 1.3 miles to where the highway forks. Take the right fork (N.C. 16) and proceed southeast for 10.1 miles to N.C. 150. Turn left, drive 2.2 miles east to McCorkle Lane, turn right, and follow the short road to the McCorkle family cemetery, located on the shore of Lake Norman. Buried at the most prominent marker in the cemetery are Major Francis McCorkle and his second wife, Betsy Brandon McCorkle.

The son of Scottish immigrants who settled in what is now Iredell County in colonial times, McCorkle lived along nearby Mountain Creek. One contemporary description of him noted that he was a handsome man about six feet tall, with a florid complexion and auburn hair. A staunch advocate of independence, he served as a militia officer throughout the war.

Following the Battle of Ramsour’s Mill, a local soldier returning home from the fight stopped by the McCorkle residence to report that the major had been killed. McCorkle’s family was overjoyed when he subsequently rode up unharmed.

Several days later, McCorkle was awakened at his home by the clatter of hooves. Voices called his name and directed him to get up and come to the door. Fearing he had been surprised by a band of Tories, McCorkle reluctantly complied. In the darkness, he was asked which side he was for. Unwilling to waver from his convictions even as death awaited, he responded boldly, “I will not die with a lie in my mouth—I’m for liberty!”

Suddenly, one of the party of men began laughing, and McCorkle realized the hoax. The would-be Tories were his fellow Patriots, who had come to take him to a celebration over the recent victory at Ramsour’s Mill.

McCorkle also served in the crucial battles at Cowpens, Kings Mountain, and Torrence’s Tavern.

Betsy Brandon McCorkle was buried beside her husband. She married Major McCorkle around 1795, when she was but a teenager. Her legendary meeting with President Washington is recounted in The Yadkin River Tour.

Return to the junction with N.C. 150. Turn right and proceed east for 3.4 miles to Sherrills Ford Road (S.R. 1848) at the crossroads community of Terrell. Turn left, drive 2.4 miles to Island Point Road at the village of Sherrills Ford, turn right, and follow the road to its terminus near Lake Norman.

The waters of Lake Norman—that massive “inland sea” created by Duke Power Company in the 1960s—now cover Sherrills Ford, a former river crossing located nearby. During the Revolution, Sherrills Ford served as an important passage over the Catawba River. Named for Adam Sherrill, a pioneer settler west of the Catawba, the ford was one of a number of routes over the river between what are now Catawba and Iredell Counties.

Daniel Morgan arrived at Sherrills Ford with a large portion of his army in late January 1781. Cornwallis and 2,000 Redcoats were in hot pursuit. Morgan’s entourage—850 American soldiers, 500 British prisoners, 800 horses, 40 wagons, and two captured cannon—stretched along area roads for more than 2 miles. It was a spectacle few residents ever forgot.

Before Morgan made his river crossing here to link up with Major General Nathanael Greene, he buried two of his finest soldiers from the Maryland Continental Line on Adam Sherrill’s farm.

Return to Sherrills Ford Road. Turn right, go 5.3 miles to Lowrance Road, turn right again, and proceed north for 2.9 miles to N.C. 10 in the town of Catawba. Turn right on N.C. 10 and follow it through town for 0.7 mile to U.S. 70. Turn left and drive 0.1 mile to S.R. 1717 (Oxford School Road). Turn right and travel north for 3.6 miles to Lookout Dam Road at the community of Catfish.

This crossroads village received its name during the Revolutionary War when a portion of Daniel Morgan’s army caught a large quantity of fish at nearby Lookout Shoals. Morgan’s men were in the process of escorting the British prisoners taken at Cowpens to Virginia.

Turn right on Lookout Dam Road and follow it for 1.3 miles to its terminus on the banks of the Catawba River at Lookout Dam. Island Ford, where Morgan’s troops made their way across the river with their British captives, was located near this site.

It was also on the nearby river shore that two of the most notorious outlaws of the Revolutionary War had their hideout. The names of Sam Brown and his sister, Charity, were infamous throughout western North Carolina during the war. Members of a family loyal to the Crown, they raided homes and farms in the foothills of North and South Carolina while many of the menfolk were away fighting for independence. Sam Brown was one of the culprits in the attempted robbery of Henry Weidner recounted earlier on this tour.

Known throughout the region as “Plundering Sam” to the Patriots and “Captain Sam” to the Tories, Brown met his demise toward the close of the war when he was shot in the Tyger River region of South Carolina by a Patriot defending his wife from the robber. After Sam’s death, Charity fled to the North Carolina mountains.

The Browns’ hideout was located on a bluff that once rose three hundred feet near the present tour stop. Their cave stood sixty feet from the base. Although the last plunder the Browns took during their crime spree was supposedly stored in the cave, nothing has ever been found by treasure hunters.

Over the years, the river has covered the cave. Yet the area remains one of mystery and intrigue. Local legend maintains that eerie noises come from the vicinity of the cave whenever someone approaches it. Some locals say that in the distant past, a tree near the cave blown down by a storm yielded twelve sets of pewter ware from its trunk.

The tour ends here, at the Catawba.