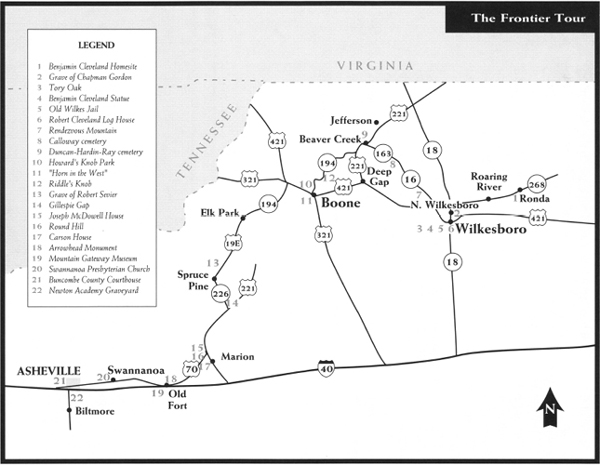

This tour begins at Ronda in Wilkes County and makes its way through Ashe, Watauga, Avery, Mitchell, and McDowell Counties before ending at Enka in Buncombe County. Among the highlights are the story of Ben Cleveland, “the Tory Oak,” the Robert Cleveland Log House, Rendezvous Mountain, the story of Martin Gambill’s ride, Howard's Knob, Wolf’s Den, Pleasant Gardens, the Carson House, historic Old Fort, the story of Samuel Davidson, and historic Asheville.

Total mileage:

approximately 1 71 miles.

This tour visits sites in a mountainous seven-county area in western North Carolina stretching from the Virginia line on the north to the Tennessee border on the west.

By the American Revolution, the first white settlers in the region had begun to lay claim to land that until that time had been the exclusive domain of the Cherokee Indians. As North Carolina prepared to join the other American colonies in the fight for independence, it faced an Indian threat on the western frontier occasioned by the clash of the two cultures.

Revolutionary War–era pioneers were independent, hearty individuals, as they had to be to survive the dangers of the Indians and the mountain wilderness. Many of these rugged trailblazers possessed a fiery spirit that led them to march from their homes down the mountain valleys in 1780 to strike a blow for the American cause at Kings Mountain.

The tour begins on N.C. 268 in the Wilkes County village of Ronda. Named for John Wilkes (1727–97), a British statesman who was an outspoken advocate of American rights during the Revolution period, the county was formed in 1778.

A state historical marker on N.C. 268 near the Ronda Town Hall pays homage to Benjamin Cleveland, one of the most colorful military leaders North Carolina produced during the war. His plantation home, “The Round About,” was located in a horseshoe bend of the Yadkin River about a mile southwest of the current tour stop. Cleveland lived there from 1771 until after the war, when he lost his land because of title difficulties.

Born in Virginia in 1738, Cleveland settled on Roaring Creek, a tributary of the Yadkin, in 1769. A neighbor of legendary frontiersman Daniel Boone, he quickly gained a reputation as a fearless Indian fighter in the mountains of western North Carolina. During the organized expedition against the Cherokees in the summer of 1776, Cleveland served as a militia officer and ranger.

When the Revolutionary War began, the good-natured but fiery-tempered frontiersman and other mountain Patriots found themselves threatened not only by Indians but also by the large numbers of Tories living along the banks of the upper Yadkin. North Carolina had no fiercer fighter against both enemies than big Ben Cleveland.

After a short stint as an officer in the North Carolina Continental Line, during which he fought in the Moores Creek campaign, he resigned his commission to serve in the militia, where he believed his skills as a hunter and backwoodsman could best be utilized. Although a speech impediment prevented him from being a skillful orator, it didn’t stop him from being a forceful leader. When Wilkes County was created from Surry County in 1778, Cleveland assumed a variety of roles: state legislator, presiding justice of county court, colonel of the county militia, and chairman of the local Committee of Safety.

Clothed with military and judicial authority, Cleveland held the upper hand in the civil war that raged in Wilkes. Determined to avenge the criminal acts of Tories who ravaged the homes and farms of mountain Patriots, he and his soldiers sought out the culprits and brought them to justice. Most often, that justice came in the form of hanging. According to noted North Carolina historian Marshall DeLancey Haywood, “Cleveland … probably had a hand in hanging more Tories than any other man in America. Though this may be an unenviable distinction, he had to deal with about as unscrupulous a set of ruffians as ever infested any land—men who murdered peaceable inhabitants, burnt dwellings, stole horses, and committed about every act in the catalogue of crime.”

Though a few captured Tories avoided the noose, Cleveland never wasted an opportunity to exact some manner of revenge. In one instance, just after hanging a Tory who had stolen horses, he gave the victim’s accomplice, who had witnessed the horrible spectacle, a choice: “Either join your companion on a tree limb, or take this knife, cut off your own ears and leave the country.” Choosing to live, the Tory departed with blood pouring down his face after mutilating himself.

Occasionally, Cleveland allowed Tories to take an oath of loyalty and then set them free. One such Tory was a noted enemy leader Cleveland was anxious to execute. He sternly ordered, “Waste no time!—swing him off quick!”

Apparently, the threat of death did not disconcert the prisoner. He calmly remarked to Cleveland, “Well, you needn’t be in such a damned big hurry about it.”

Taken by the bearing of the condemned man, Cleveland shouted another command, “Boys, let him go!”

So appreciative was the Tory that he enlisted in the American cause and eventually proved one of Cleveland’s most faithful and trusted soldiers.

Without question, the brightest moment in Cleveland’s military career came during the titanic struggle at Kings Mountain on October 7, 1780. At the height of the battle, Major Patrick Ferguson attempted to push his Loyalist forces through Cleveland’s line. In response, the mountaineers poured out rifle fire that fatally wounded the British commander and ensured the American victory.

After Ferguson fell, his splendid white charger was captured by the victorious Americans. By common consent, the magnificent animal was given to Colonel Cleveland, whose mount had been lost in the battle. But there was another reason Ferguson’s horse was given to Cleveland—since he weighed more than 300 pounds, the colonel was too heavy to travel afoot.

At the time of his death, Cleveland weighed in excess of 450 pounds. A frequent guest of General Andrew Pickens, Cleveland caused consternation in the Pickens household. One of the general’s daughters recalled, “We were always afraid when Colonel Cleveland came to stay over night with us lest the bedstead should prove unequal to his ponderous weight.”

After he lost “The Round About,” Cleveland moved his family to the Tugaloo River Valley in the South Carolina back country, where he died and was buried.

Proceed west on N.C. 268 for 3.6 miles to the community of Roaring River. En route, you can enjoy views of the northern bank of the Yadkin near the horseshoe where Cleveland’s house stood. The two-story structure rested on a promontory, one of the sites from which the colonel sounded his mighty horn to summon his soldiers, men known as “Cleveland’s Bull-Dogs” to partisans and “Cleveland’s Devils” to Tories.

At Roaring River, a state historical marker pays tribute to Richard Allen, Sr. (1741–1832), a distinguished Revolutionary War officer who served the American cause from 1775 to 1781. Captain Allen was ordered to the scene of four of the most significant engagements in the Carolinas—Moores Creek Bridge, Charleston, Kings Mountain, and Guilford Courthouse. Ironically, because of timing, he took no active part in any of the four.

His marked grave lies 4 miles north.

Continue west on N.C. 268 for 9.6 miles to where it merges with N.C. 18 at North Wilkesboro. Known in Revolutionary War times as Mulberry Fields, North Wilkesboro was where Benjamin Cleveland first lived after he settled in the North Carolina mountains.

Along the way, you’ll pass a state historical marker for Montfort Stokes (1762–1842). Like his older brother, John, Montfort Stokes offered his services to the American cause at the outbreak of the Revolution, enlisting in the Continental Navy and serving under Commodore Stephen Decatur. During action off Norfolk in 1776, Stokes’s vessel was captured by the British fleet. He suffered great deprivation during his subsequent confinement aboard a prison ship in New York Harbor.

His impressive postwar career as a statesman included service as governor of North Carolina and as a United States senator. Stokes’s home, Morne Rouge, stood a mile south of the marker.

Proceed south on N.C. 268/N.C. 18 for 0.8 mile to where it merges with U.S. 421 Business. Continue for 0.3 mile to the junction of Sixth and Main Streets in downtown North Wilkesboro. Drive west on Main for 0.4 mile to Tenth Street, turn right, and go four blocks to D Street. Turn right on D Street and proceed two blocks to Eighth Street. On the northwestern corner of this intersection stands First Presbyterian Church.

A tablet in the basement of the sanctuary serves as the grave marker of Chapman Gordon (1764–1812), one of five Wilkes County brothers—the sons of a member of the Continental Congress—who fought in the Revolution. Although he was only sixteen years old at the time, Chapman Gordon joined his four siblings to fight at the Battle of Kings Mountain.

After the war, he settled in North Wilkesboro. Ironically, he married Charity King, the daughter of Charles King, the man for whom Kings Mountain was named. Their grandson, John B. Gordon, was a Confederate major general and a governor of Georgia.

The Presbyterian church was constructed over Gordon’s grave. When a full basement was excavated, his remains were reburied even deeper.

Retrace your route to U.S. 421 Business/N.C. 268/N.C. 18 at the junction of Main and Sixth. Turn right and follow N.C. 268/N.C. 18 for 0.1 mile to Wilkesboro Avenue. Turn left and proceed 0.3 mile to where Wilkesboro again junctions with N.C. 268/N.C. 18. Turn left and follow N.C. 268/N.C. 18 south for 0.2 mile across the Yadkin River to Main Street in Wilkesboro, the county seat.

Turn right and follow N.C. 268/N.C. 18 (East Main Street) for 0.4 mile to the Wilkes County Courthouse, erected in 1903. Bounded by East Main, Broad, North, and Bridge Streets, the white, three-story Neoclassical Revival structure rests on a square that boasts several Revolutionary War landmarks. Park nearby for a short walking tour.

Near the courthouse green, two “fixtures”—one man-made and the other natural—pay homage to Big Ben Cleveland.

One is a large statue of the notorious Tory-hunter sculpted in 1975 as a bicentennial project. It stands just across Bridge Street on the western side of the courthouse.

The other is “the Tory Oak,” one of the most historic trees in North Carolina. A tall, stately sprout has survived the demise of the mother tree, which was ravaged by a tornado and other storms in recent years. It is located at the rear of the courthouse near the junction of Broad and North Streets.

Benjamin Cleveland used the once-mighty oak as a gibbet for five Tories during the war. Two of the unfortunate men, named Cowles and Brown, were put to death for stealing horses from the plantation of a Patriot in what is now Catawba County. The other three—William Riddle and his associates, Reeves and Goss—were hanged after a hasty court-martial in Wilkesboro, over which Cleveland presided. He was anxious for the trio to die, since Riddle had masterminded a plan that had led to Cleveland’s capture earlier in 1780. Riddle had spared Cleveland from the hangman’s rope, but after his escape, Cleveland was not as benevolent toward his former captor. (The story of Cleveland’s capture by Riddle and his subsequent escape is detailed later in this tour.)

From the rear of the courthouse, walk one block west on North Street and turn right on Bridge Street, where you’ll see the Old Wilkes Jail, a museum of Wilkes County history. Inside the two-story, nineteenth-century brick structure are numerous artifacts and exhibits from the long history of Wilkes.

Immediately behind the jail building is the Robert Cleveland Log House. Believed to be the oldest structure in Wilkes County, the house was constructed in the last quarter of the eighteenth century by the brother of Benjamin Cleveland. Moved to this site in recent years from its original location in western Wilkes County, the carefully restored two-story log structure offers visitors a glimpse of the mountaineers’ way of life during Revolutionary War times.

Robert Cleveland was instrumental in rescuing his brother from William Riddle. He subsequently marched with Benjamin to Kings Mountain, where he was wounded.

Return to your vehicle. Follow N.C. 268/N.C. 18 west for 1.2 miles to N.C. 16/U.S. 421. Turn right and go west for 2.5 miles to where N.C. 16 and U.S. 421 divide. Turn right, follow N.C. 16 north for 5.2 miles to S.R. 1346, turn left, and proceed 2.2 miles to S.R. 1348. Turn right and follow the winding, twisting road up Rendezvous Mountain.

Towering 2,450 feet above sea level, the mountain offers a breathtaking view of the surrounding countryside. Its name is derived from the Revolutionary War activities of Benjamin Cleveland and his mountain militiamen. From the summit of this lofty peak, Cleveland used his legendary horn to summon his soldiers when they were needed to battle Tories. Three strong blasts from the horn, which could be heard for 30 miles in all directions, brought Patriots from several counties to the mountain. It was here that they trained and drilled and here that they rendezvoused before marching to Kings Mountain.

In 1926, Judge Thomas B. Finley donated 142 acres of the mountain for a state park. Thirty years later, the state decided that the site did not meet the criteria for inclusion in the park system. In 1984, however, the mountain was opened for public use as Rendezvous Mountain Educational State Forest. Its facilities include trails, picnic shelters, restrooms, and an amphitheater. Historical markers erected by the D.A.R. are located near the entrance and at the top of the mountain.

Drive down the mountain to the junction with S.R. 1346. Located just southwest of the intersection are the original site of the Robert Cleveland Log House and the graves of Cleveland and his wife.

Retrace your route to N.C. 16. Proceed northwest on N.C. 16 for 9.9 miles to the Ashe County line. Created from Wilkes County in 1799 and named for Revolutionary War hero Samuel Ashe, the county borders both Virginia and Tennessee.

From the county line, it is 0.3 mile to N.C. 163. Turn left on N.C. 163 and proceed 2.5 miles south to the Calloway cemetery, located on the left side of the road near the community of Obids, which is on the southern fork of the New River.

Perhaps the most unusual grave marker here is a tall, slender rock that resembles a cactus. It marks the final resting place of Captain Thomas Calloway, Sr., an officer in the French and Indian War and Daniel Boone’s companion on the famous trailblazer’s trips to Kentucky.

Prior to the Revolution, Calloway settled his family on a plantation on the New River north of the cemetery. There, he maintained a garrison for Patriots during the war. His five sons and two sons-in-law were active participants in the fight for independence.

At one time, the unique stone at Calloway’s grave was used to mark Daniel Boone’s camp at Obids. When Calloway died in February 1800, Boone placed the stone on his friend’s grave and chiseled the initials T. C. into the rock. A D.A.R. plaque near the grave honors Calloway.

Proceed north on N.C. 163 for 7.1 miles to the junction with U.S. 221 and N.C. 194 near the community of Beaver Creek. Go north on N.C. 194 for 0.1 mile to Beaver Creek School Road, turn left, and drive 1.8 miles to S.R. 1225 (Ray Road). At the junction stands Beaver Creek Christian Church. On the opposite side of the road is the Duncan-Hardin-Ray cemetery.

Because much of western North Carolina was on the frontier at the time of the Revolution, it was not the site of a large number of significant battles. However, the frontier was gradually opened by men who had fought in the conflict. Consequently, many old cemeteries in the North Carolina mountains hold the graves of heroes of the fight for independence. The remains of Colonel Jesse Ray, a Revolutionary War officer who died in Ashe County in 1839, lie here. The unusual stone monument at his grave was designed by an American sculptress in Paris and crafted in Georgia. Bronze plaques on the marker detail Ray’s military service.

Retrace your route to the intersection of N.C. 194 and U.S. 221 and go south on U.S. 221. It is 10.8 miles to the Watauga County line. The county takes its name from the Watauga River. An Indian word, Watauga means “beautiful water.” It was also the name of the region in what is now Tennessee where pioneers formed a government by 1776. The Watauga settlement was the source of many of the Overmountain Men who played a prominent role in the victory at Kings Mountain.

The highway roughly follows an old Indian trail used by Martin Gambill when he made his patriotic ride in 1780.

Major Patrick Ferguson began his invasion of western North Carolina and South Carolina in the late summer and early fall of 1780, as part of Cornwallis’s plan to suppress Patriot activity in the region. In response, Patriots ignited large brush piles atop the loftiest peaks as signal fires calling for militia leaders to assemble. Because the signal fires extended only to Watauga County, it was vital that a horseman spread the alarm to points beyond. Gambill, a resident of Ashe County, volunteered for the important duty.

Gambill rode for twenty-four hours without food or water to alert friends, neighbors, and strangers sympathetic to the cause of independence. In the course of his grueling 100-mile ride, two horses fell dead from exhaustion. His route followed the modern U.S. 221 north into Virginia, ending at the home of Colonel Arthur Campbell at Seven Mile Ford. Campbell promptly put his forces on the march to North Carolina, where they united with other militiamen to form a Patriot army commanded by Campbell’s cousin, William. That army subsequently dealt Ferguson his devastating defeat at Kings Mountain.

From the Watauga County line, continue west for 1.2 miles to the community of Deep Gap, where U.S. 221 merges with U.S. 421. Bear right on U.S. 221/U.S. 421 and proceed west for 9.7 miles to Boone, the seat of Watauga County.

Boone was named for the legendary pioneer. Its most prominent landmark is Howard’s Knob, a 4,451-foot peak that towers above the town. Howard’s Knob Park is an excellent place to explore the beauty and history of the mountain. To reach it, follow U.S. 221/U.S. 421 west through downtown Boone, where it becomes King Street. Just west of the post office, turn right onto Water Street and proceed one block as Water circles into North Street. Turn left off North onto Junaluska Road, proceed up the steep, winding road to the park entrance, and turn right to proceed into the park.

During the Revolution, Benjamin Howard—a noted Tory and the man for whom the mountain was named—fled his Wilkes County home while being relentlessly pursued by Benjamin Cleveland. Howard found safety in a small cave at the base of a low cliff on the mountain. The subterranean passages provide an excellent hiding place, and the mountain peak proved a strategic point from which Howard could watch for Cleveland’s approach.

It was thanks to his family that Howard eluded capture. Even a severe switching administered by a group of men could not compel his daughter, Sallie, to reveal the location of his hideout.

In 1778, Howard came forward to take the oath of allegiance. Thereafter, his daughter was a staunch supporter of the American cause.

Retrace your route to the junction of Water and King Streets in downtown Boone. Turn left on King and follow it east to U.S. 321. Turn right on U.S. 321 and follow it south as it skirts the campus of Appalachian State University. After 0.6 mile, you will reach Horn in the West Drive. Turn left and drive east for 0.2 mile to Daniel Boone Native Gardens, one of the two local attractions that honor the North Carolinian who spent most of the Revolutionary War exploring the wilderness and fighting Indians in his quest to further the westward expansion of the new nation.

Adjacent to the gardens is the Daniel Boone Amphitheater, the site of Horn in the West, the third-oldest outdoor historic drama in the United States. (The two oldest—The Lost Colony and Unto These Hills—are also in North Carolina.) Every summer since 1952, Horn in the West has brought to life the story of the Revolutionary War in the North Carolina mountains and the efforts of Daniel Boone to win freedom for his people. Among the characters in Kermit Williams’s play are Boone, Benjamin Cleveland, Patrick Ferguson, and Banastre Tarleton.

Located on the amphitheater grounds is the Hickory Ridge Homestead Museum, which features a log-cabin village typical of the area during Revolutionary War times.

Return to the junction with U.S. 321. Turn right and proceed to U.S. 221/U.S. 421 at the Daniel Boone Inn. Turn right and go 0.9 mile on U.S. 221/U.S. 421 to N.C. 194 (Jefferson Road). Turn left on N.C. 194, follow it for 4.4 miles to S.R. 1335, then continue north on N.C. 194 for another 1.5 miles to Riddle’s Knob.

Nearly five thousand feet tall, this peak provided the backdrop for the only military engagement in Watauga County during the Revolutionary War. An abandoned farmhouse and barn on the left side of the road marks the site. In the forest behind the old farm is a cavern known as Wolf’s Den. It was from this cave that Benjamin Cleveland was rescued by his brother, Robert, and a group of Patriots amid a hail of bullets.

This entertaining piece of Revolutionary War history began six months after Big Ben Cleveland attained immortal fame at Kings Mountain. Captain William Riddle, the noted Tory for whom Riddle’s Knob peak was named, sought to rid the area of his archrival, the rotund militia colonel.

At that time, Cleveland owned Old Fields, a considerable tract of land and cattle farm on the southern fork of the New River near the present-day Ashe County-Watauga County line. On April 14, 1781, he arrived at Old Fields after a 35-mile ride from “The Round About.” Upon learning of Cleveland’s presence, Captain Riddle stole his horse and laid an ambush for him. When Cleveland and fellow Patriot Richard Calloway went searching for the prized animal—the former mount of Major Patrick Ferguson—the following morning, Riddle and his band opened fire. Calloway was unarmed, and Cleveland had but two pistols. Calloway was seriously wounded in the thigh, but Cleveland avoided certain death when he grabbed a local woman, Abigail Walters, and used her as a human shield until Riddle promised he would not be killed if he surrendered. Riddle reasoned that Cleveland would fetch a handsome price from the British if presented alive.

After Cleveland and Calloway were taken prisoner, Riddle and his Tory associates brought their prizes to the current tour stop. Along the way, the ever-resourceful Cleveland broke overhanging twigs to mark the route.

Meanwhile, local Patriot Joseph Calloway learned of the misfortune that had befallen his two comrades. He mounted his horse and galloped to the cabin of Cleveland’s younger brother, Robert. Upon receiving the news, Robert assembled a force of twenty to thirty men who had served under Big Ben Cleveland. They immediately took up the chase.

Riddle and his party decided to camp at Wolf’s Den. After an uneventful night, the Tories prepared an early breakfast. Cleveland sat on a fallen tree under heavy guard, including one sentinel who held the colonel’s pistol to his head. The prisoner was under orders to write out passes to certify that each of his captors was a good Whig. These papers were to be used by the Tories for unfettered passage through the border country. Fearing that he might be considered expendable once he completed his assigned task, Cleveland delaying finishing. As Riddle and his men grew more and more impatient, the prisoner apologized for his lack of progress, blaming it on his poor penmanship.

Cleveland was down to the last pass when his brother and the rescue party attacked with gunfire and loud yells. To avoid the hail of friendly fire, Cleveland rolled off the tree on the side opposite the attackers. Delighted by their presence, Big Ben shouted, “Huzza for brother Bob!—that’s right, give ’em hell.” One of the Tories was badly wounded in the fray. Riddle and the others escaped, only to meet their fate on the Tory Oak.

Retrace N.C. 194 to its junction with U.S. 421/U.S. 321. Turn right and travel west on N.C. 194/U.S. 421/U.S. 321 for 7.6 miles to where N.C. 194 splits off and turns south. It is 8.9 miles on N.C. 194 to the Avery County line. Established in 1911, the year that North Carolina created the last of its hundred counties, Avery was named for Colonel Waightstill Avery, a Revolutionary War soldier and the first attorney general of the state of North Carolina. (For more information on Avery, see The Foothills Tour, pages 235–37.)

Continue 9.2 miles west on N.C. 194 to U.S. 19E near Elk Park. Turn left on U.S. 19E and follow it 7.3 miles south to the state historical marker at Roaring Creek Bridge, located southwest of the village of Frank.

The marker calls attention to the site of Yellow Mountain Road, which took its name from Big Yellow Mountain and Little Yellow Mountain, located nearby. In September 1781, Isaac Shelby and John Sevier of Tennessee, William Campbell of Virginia, and the Overmountain Men traveled Yellow Mountain Road on their way to a rendezvous with Carolina militiamen before their battle with Patrick Ferguson at Kings Mountain.

Near the current tour stop, Yellow Mountain Road followed an old Indian trail known as Bright’s Trace. Samuel Bright, the lawless individual for whom the path was named, settled in the area prior to the Revolution and remained loyal to the Crown during the war.

Continue south on U.S. 19E for 11.7 miles to the Mitchell County line. Here, the road turns abruptly west. Follow it for 3.3 miles to the bridge over the Toe River. Located on the nearby riverbank is the Bright family cemetery. A ceremony was held here by the D.A.R. on September 9, 1951, to mark the grave of Captain Robert Sevier, a casualty of the fighting at Kings Mountain.

In September 1781, Sevier left his wife and two infant sons in the hills of eastern Tennessee to follow his brother John across the mountains to the showdown at Kings Mountain. Toward the close of the battle, a bullet pierced his kidney. A British surgeon unsuccessfully attempted to extract the bullet. He dressed the wound and told Sevier that if he remained quiet and immobile, the bullet could subsequently be removed. Otherwise, the physician warned, the wound would become inflamed and death would soon follow.

Sevier feared capture by the Tories more than death itself, so he mounted his horse and headed for home with his nephew James Sevier. Nine days later, the two were camped near the current tour stop on land owned by Samuel Bright when Robert fell ill and died. His body was wrapped in a blanket, and he was buried in an unmarked grave under “a lofty oak.”

Using descriptions in old court records and research by historians, D.A.R. members concluded that Sevier’s grave was most likely located here. On their annual pilgrimage from Tennessee to Kings Mountain, reenactors of the Overmountain Men’s march hold a service at Sevier’s grave.

Continue on U.S. 19E for 0.7 mile to N.C. 226. The men of Shelby, Sevier, and Campbell camped in this vicinity on September 28, 1780.

Turn south on N.C. 226 and drive 4.8 miles to its intersection with the Blue Ridge Parkway at Gillespie Gap near the McDowell County line. Created in 1842, McDowell County was named for Major Joseph McDowell (1758–95), a young Revolutionary War hero born in the area.

The Overmountain Men poured through Gillespie Gap on Friday, September 29, 1780. Near the site where the North Carolina Mineral Museum stands today, they made the decision to divide their forces for fear that they might march into an ambush. A monument on the museum grounds pays tribute to those long-ago citizen-soldiers.

Approximately 5.4 miles south of Gillespie Gap, N.C. 226 junctions with U.S. 221. Colonel William Campbell and his Virginians camped the night of September 29, 1780, just east of the junction. At the same time, Colonels Sevier and Shelby rested their men near Honeycutt’s Creek, located 3.5 miles north. Sevier reportedly spent the night in a house that stood 1.5 miles from the current tour stop in the community that today bears his name.

Near the junction stands a state historical marker for the site of Cathey’s Fort. Located a mile to the east, the fort served as a rendezvous point for General Griffith Rutherford and his North Carolina militia in their famous 1776 campaign against the Cherokee Indians. (The campaign against the Cherokees is examined later in this tour; for additional information on Rutherford, see The Yadkin River Tour, pages 296–98.)

Continue south on N.C. 226/U.S. 221; remain on the highway’s business route. After 6.8 miles, you will reach U.S. 70 in Marion. Named for Revolutionary War hero Francis Marion, “the Swamp Fox,” the city is the seat of McDowell County. The first sites settled in the town were on land granted to Revolutionary War soldiers.

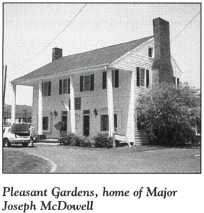

Near this intersection is Pleasant Gardens, the ancestral home of Major Joseph McDowell. A nearby state historical marker calls attention to the site.

In the 1750s, McDowell’s father, known as “Hunting John,” settled here on a tract he named Pleasant Gardens. Soon thereafter, he built the log cabin in which Joseph McDowell was born in 1758. In recent times, the stately two-story house has been converted into a commercial building. Due to its prime location at a busy intersection, its future existence is in doubt.

A renowned Indian fighter, Joseph McDowell took up arms with his Burke County cousins, Joseph “Quaker Meadows Joe” and Charles McDowell, during the Revolution. (For more on the Burke County McDowells, see The Foothills Tour, pages 237–39.) To distinguish himself from his Burke County cousin of the same name, he usually affixed P. G. (for Pleasant Gardens) to his signature.

Turn right on U.S. 70 and proceed 0.9 mile west. An unpaved road on the right leads up the mountain to Round Hill, the historic burial ground of the McDowell and Carson families.

Continue west on U.S. 70 for 0.3 mile to the Carson House, located on the left just off the highway.

Open to the public, this three-story clapboard house was constructed of twelve-inch walnut logs by Colonel John Carson in 1780. An Irish immigrant, Carson settled in the Upper Catawba River Valley in 1773. He served as a delegate to the Fayetteville Convention of 1789, at which the state ratified the United States Constitution.

After the death of his first wife, Carson married Mary Moffitt McDowell, the widow of Major Joseph McDowell. Their son, Samuel Price Carson, born in the Carson House in 1798, was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1825 and went on to serve four terms. After his subsequent relocation to Texas, he became the first secretary of state of the republic of Texas.

Proceed west on U.S. 70 for another 0.2 mile. Just beyond Pleasant Gardens Elementary School is the site of a fort built by local pioneers for protection against Indians.

Continue west for 3.5 miles to S.R. 1214. Nearby stood “The Glades,” the home built by Major William Davidson (not to be confused with General William Lee Davidson). Major Davidson and his twin brother were intrepid Indian fighters and pioneer settlers in the region west of the current tour stop. Because William Davidson was a well-known Patriot, Major Patrick Ferguson stopped at “The Glades” in 1780 to try to capture him.

Resume the route westward on U.S. 70. It is 6.2 miles to the town of Old Fort. In the heart of Old Fort stands its trademark, a fifteen-foot-tall arrowhead monument crafted of pink Salisbury granite, erected in 1928 as a memorial to the pioneer settlers of western North Carolina.

It was this place that marked the dividing line between white settlers and the Cherokee Indians prior to the Revolutionary War. Before 1756, by Royal decree, white people were not allowed to settle beyond the crest of the Blue Ridge, which can be seen towering above Old Fort. Thus, when the first settlers began making their way onto Indian land beyond Old Fort on the eve of the Revolution, Cherokee reprisals were frequent events.

Old Fort took its name from a fort constructed here by colonial militia in 1776 for protection against the Cherokees. It has also been known by three other names: Upper Fort (to distinguish it from Cathey’s Fort and the fort near Pleasant Gardens), Catawba Fort (for the river or the Indian tribe of the same name), and Davidson’s Fort (for Samuel Davidson, twin brother of William, who owned land and a mill here and who became one of the first white settlers west of Old Fort).

Cherokees attacked Old Fort and the surrounding settlements in the spring of 1776, as the first fires of the Revolution were beginning to smoulder. By the time the Declaration of Independence was signed, Old Fort was considered one of the most dangerous spots in North Carolina. Attempts by North Carolina and the other Southern colonies to assure the neutrality of the Cherokees and Creeks were thwarted by the agents under John Stuart, the British superintendent of Indian affairs in the South. Stuart and his men incited the Indians to violence.

Near the arrowhead monument stands a state historical marker describing North Carolina’s military response to the Indian uprisings. General Griffith Rutherford used the old log stockade located here as a staging area for his subsequent campaign to quell the Cherokee threat.

From Old Fort on July 14, 1776, Rutherford dispatched a crudely written letter to the Council of Safety wherein he chronicled the desperate situation on the North Carolina frontier:

I am Under the Nessety of sending you by Express, the Alerming Condition, this Country is in, the Indins is making Grate prograce in Distroying & Murdering, in the frunteers of this County, 37. I am Informed was Killed Last Wednesday & Thursday, on the Cuttaba River, I am also Informed that Col. McDowel 10 men more & 120 women & Children is Beshaged, in sume kind of fort, & the Indins Round them, no help to them before yesterday. … I Expect the Nex account to here they are Distroyed. … Pray Gentelman Considere oure Distress, send us Plenty of Powder. … This Day I set out with what men I Can Raise for the Relefe of the Distrest.

To put an end to the Indian uprisings, Rutherford assembled an army of twenty-five hundred back-country riflemen. Leaving the bulk of his forces at Old Fort, he moved west with five hundred men on July 29. Over the next several months, he and his soldiers marched deep into the mountains, where they burned thirty-six Cherokee towns, destroyed crops, and drove the Indians into hiding. By the year’s end, the Indian threat in western North Carolina was over for the duration of the war, and the militiamen could turn their full attention to the Tory menace.

At the arrowhead monument, turn left onto Catawba Avenue. Proceed two blocks to Water Street and turn left. You’ll notice an old stone building. Constructed by the WPA as a community center, it now houses the Mountain Gateway Museum, a branch of the North Carolina Museum of History. The Mountain Gateway Museum offers interesting exhibits and displays that tell the story of Old Fort and the frontier in Revolutionary War times.

Historians believe that Davidson’s Fort was located on the bank of Mill Creek on the vacant land next to the museum.

Return to Catawba Avenue and drive south to 1-40. Follow 1-40 West, which runs conjunctively with U.S. 70 for a time. It is 5.9 miles to the Buncombe County line. Formed in 1791, the county was named in honor of Colonel Edward Buncombe, a Revolutionary War hero from eastern North Carolina.

Located on an access road just west of the county line is a state historical marker that notes the site of nearby Swannanoa Gap. On September 1, 1776, General Griffith Rutherford pushed two thousand soldiers and fourteen hundred packhorses through this passage on a final drive to end the Indian threat in western North Carolina.

Approximately 2 miles west of the county line, U.S. 70 separates from 1-40 at the town of Black Mountain. Exit onto U.S. 70 and proceed west for 1.9 miles through the town to the junction with Old U.S. 70. Veer right onto Old U.S. 70 and go 3.9 miles to the town of Swannanoa, situated on the banks of the river of the same name. At the junction of Old U.S. 70 and Bee Tree Road (S.R. 2416), turn right. It is 0.7 mile to Swannanoa Presbyterian Church, organized in 1794. Adjacent to the church is Piney Grove Cemetery.

Interred in a marked grave in this burial ground is Major William Davidson, a devoted Patriot and Indian fighter who was instrumental in the preparations for the Battle of Kings Mountain. Following the war, Davidson left his home, “The Glades,” and joined a group of friends and relatives moving across the mountains. They made their homes at the mouth of nearby Bee Tree Creek at what became North Carolina’s first white settlement west of the Blue Ridge.

Two of Davidson’s brothers were killed by the Cherokees. His other brother, John, was killed near Old Fort in July 1776, and his twin, Samuel, was scalped in 1784. The three brothers were cousins of General William Lee Davidson, the Patriot hero who fell at the Battle of Cowan’s Ford. (For more information on General Davidson, see The Tide Turns Tour, pages 282–85, and The Hornet’s Nest Tour, pages 172–75.)

Return to Old U.S. 70 and continue west to Riverwood Road (S.R. 2436). Turn left on Riverwood, follow it across the Swannanoa River to U.S. 70, and turn right.

Jones Mountain towers above the right side of the highway after 2.9 miles. Footpaths lead up the mountain to its summit, where a granite gravestone reads, “Here Lies Samuel Davidson.… First White Settler In Western North Carolina… Killed Here By Cherokees in 1784.”

Davidson and his family ventured into the frontier several months prior to his death and established a homestead at the foot of the mountain. It was Davidson’s custom to turn his horse out to forage with a cowbell around its neck, so he could keep track of the animal’s whereabouts. Cherokee Indians, still smarting from the harsh treatment by Rutherford’s troops and angered by Davidson’s incursion into their territory, decided to catch the horse and use its bell to lure Davidson into an ambush. Using rifles provided by British agents during the war, they shot the unarmed settler as he reached the trail that ran along the top of Jones Mountain.

At the family’s crude cabin, Davidson’s wife heard the gunfire. Upon seeing her husband’s rifle nearby, she knew what had happened. She grabbed up her baby, and she and a servant girl then made haste to the safety of Old Fort.

Immediately, a band of men set out in the darkness to avenge Davidson’s death. They found his lifeless, scalpless body where it had fallen. Lurking nearby were the Indians who had mutilated him. The settlers killed some of them and drove the others away. They buried Davidson at the site.

Though Samuel Davidson’s bold venture resulted in his death, it also opened the frontier to his brother and other Revolutionary War soldiers who settled in the mountains in the late eighteenth century.

Continue west for 5.3 miles to downtown Asheville, where U.S. 70 becomes College Street.

Asheville, the seat of Buncombe County, was incorporated in 1797. It was named in honor of Revolutionary War hero Samuel Ashe. Settled around 1792, the city was originally known as Morristown. Although the origin of the name is uncertain, some historians believe that it honored war financier Robert Morris, who owned vast tracts in the area.

Located on the square formed by College, Davidson, Spruce, and Marjorie Streets are the Buncombe County Courthouse and Asheville City Hall. Several monuments and markers related to the Revolution are located on the square. Dedicated by the D.A.R. in 1923, a huge block of granite with an inscribed bronze plaque pays homage to the life and service of Colonel Edward Buncombe, the man for whom the county was named. Other D.A.R. markers on the square honor Patriots Samuel Ashe and David Vance.

Continue west on College Street for two blocks to Biltmore Avenue. Proceed south on Biltmore for 2.1 miles to Unadalia Avenue, turn left, and go 0.1 mile to Newton Academy Graveyard.

Among the Revolutionary War soldiers interred here is Colonel David Smith. The son-in-law of Major William Davidson, Smith was among the men who went over the mountains to avenge the death of his wife’s uncle, Samuel Davidson.

When William Davidson began the settlement at Bee Tree Creek, Smith was there. He subsequently became one of the first two men to settle at the site of Asheville. His gravestone reads, “The soil which inurns his ashes is a part of the heritage wrested by his valor for his children and his country from a ruthless and savage foe.”

William Forster, the other early white settler here, is also buried in Newton Academy Graveyard. Born in Ireland, he served in the American army during the Revolution. While suffering from sickness, Forster dreamed he was buried under a particular tree on the land where the cemetery is now located. Although he recovered from that illness, Forster’s request that he be interred under the tree of his dreams was honored.

Another marked grave holds the remains of Captain Edmund Sams, an officer in the Revolution and an Indian fighter said to have had “no superior and few equals.” Following the war, Sams established the first ferry across the French Broad River.

Return to Biltmore Avenue. Turn left and go south for 0.5 mile to where Biltmore merges with U.S. 25 on the southern bank of the Swannanoa River. Continue south on U.S. 25 for 0.2 mile to Vanderbilt Road. Here stands one of a number of state historical markers in the mountains that identify Rutherford’s Trace.

During its expedition against the Cherokees in September 1776, General Griffith Rutherford’s army moved along the banks of the Swannanoa River near the present tour stop. On his triumphant return, Rutherford marked his path through the mountains, and the route has been known as Rutherford’s Trace ever since. Some later roads in the mountains have been laid out along Rutherford’s ancient route.

Continue south on U.S. 25 for 0.8 mile to 1-40. Proceed west on 1-40 for 7.1 miles to the exit for Smokey Park Highway (U.S. 19/U.S. 23/U.S. 74). Travel southwest on Smokey Park Highway for 1.9 miles to Sand Hill Road (S.R. 3412). Turn left and drive southeast to the state historical marker near the site of the home of Captain William Moore, an officer in the Revolution and the first white man to settle in North Carolina west of the French Broad River.

Moore, an Irish immigrant, lived in Rowan County when the fight for independence began. He first came to the mountains in November 1776, when he commanded a militia company during an expedition against the Cherokees. Setting up camp along nearby Hominy Creek, Moore was so awestruck by the natural beauty of the wilderness that he exclaimed to his immediate commander (who was his father-in-law), “This is Eden’s land.”

After the North Carolina General Assembly opened the lands west of the Blue Ridge to white settlement in 1783, Moore staked a claim to the area around where the state historical marker stands today. Governor Richard Caswell granted him a 640-acre tract in 1784, upon which Moore constructed a combination cabin and blockhouse. The structure stood until 1930, when it was torn down. Stones from the cabin’s foundation were used in the foundation of nearby Oak Forest Presbyterian Church.

Moore is buried in an old family cemetery near the site of his cabin on land owned by American Enka Corporation, which spearheaded the 1981 effort to restore the ancient burial ground. Among the dignitaries who attended the commemorative rites at the newly restored cemetery that October was former North Carolina governor Dan K. Moore, the great-great-grandson of Captain Moore.

The tour ends at Moore’s grave site.