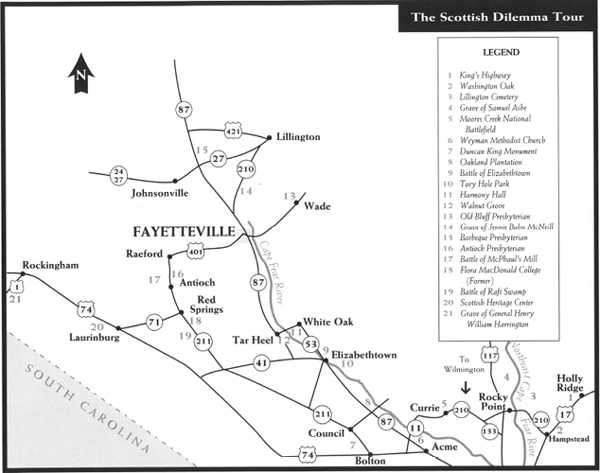

This tour begins at Holly Ridge in Onslow County and makes its way through Pender, Columbus, Bladen, Cumberland, Harnett, Hoke, Robeson, and Scotland Counties before ending south of Rockingham in Richmond County. Among the highlights are the grave of Alexander Lillington, Moores Creek National Battlefield, the story of Duncan and Lydia King, the Battle of Elizabethtown, Harmony Hall, historic Fayetteville, Old Bluff Presbyterian Church, the story of “Jennie Bahn” McNeill, Barbeque Presbyterian Church, the Battle ofMcPhaul’s Mill, and the Battle of Raft Swamp.

Total mileage:

approximately 353 miles.

This tour covers an expansive ten-county area in the southeastern part of the state where thousands of people from the Scottish Highlands settled in the middle of the eighteenth century. Following their bloody defeat by the British at Culloden in 1746, the Highland Scots found their land occupied by English soldiers who made living conditions intolerable. Across the sea, North Carolina offered liberal land grants and the promise of a new life.

Before they were allowed to leave Scotland for the colony, the Scots were required to pledge allegiance to the British Crown and to sign an oath that ended with these harsh, chilling words: “And should I break thee, my solemn oath, may I be cursed in all my undertakings, family and property; may I never see my wife, children, father, mother or other relatives; may I be killed in battle as a coward and lie without Christian burial in a strange land, far from the graves of my forefathers and kindred. May all this come to me if I break my oath.”

When the time came for the fight for American independence, the Highlanders who had poured into southeastern North Carolina faced a dilemma: would they honor their oath and support the hated monarchy or fight for the freedom of the colonies? Most of the Scottish Highlanders in North Carolina chose to remain loyal to the Crown. Others fought for American freedom. A few attempted to remain neutral.

A number of eminent Patriots of English and Scots-Irish descent made their homes in this area of Scottish dominance. Neighbors clashed with each other in bloody encounters on numerous occasions during the war. While the fight for American independence raged throughout the colonies, a virtual civil war was fought along the byways covered on this tour.

The tour begins on U.S. 17 at the village of Holly Ridge in southern Onslow County. Along the highway, you’ll notice a state historical marker commemorating George Washington’s travels through the area. On the night of April 23, 1791, the president lodged at Sage’s Inn, which was located two hundred yards east of the marker.

Drive south on U.S. 17, which passes over the route of the first intercolonial roadway through North Carolina. Known as the King’s Highway, it went from Virginia into North Carolina at Perquimans County and passed through Edenton, Bath, New Bern, and Wilmington before entering South Carolina. Completed in 1727, the highway stretched 275 miles through North Carolina.

Two miles south of Holly Ridge, U.S. 17 enters Pender County. Continue south as it passes just east of the nearly impenetrable wilderness of the 48,500-acre Holly Shelter Game Land.

When President Washington traveled south through this area along the King’s Highway, he was not impressed with the landscape. In his diary, he noted that “the whole Road from New Bern to Wilmington (except in a few places of small extent) passes through the most barren country I ever beheld; especially in the parts nearest to the latter; which is no other than a bed of white sand.”

Little did Washington imagine that the ocean strand only a few miles to the east would be packed with expensive resort homes two centuries later.

From the Pender County line, it is 10.5 miles on U.S. 17 to Hampstead, which boasts a landmark from Washington’s visit. On the right side of the highway stands the Washington Oak, a massive tree with sweeping limbs under which the president rested in April 1791. The tree has been appropriately marked by the D.A.R.

Just south of Hampstead, U.S. 17 junctions with N.C. 210. Turn right onto N.C. 210 and follow it for 9.6 miles to S.R. 1520 on the eastern side of the Northeast Cape Fear River. Turn right on S.R. 1520, proceed 4.1 miles, and turn right on unpaved Lillington Lane. Drive east for 1.2 miles to the Lillington cemetery, taking care not to veer right where Lillington Lane forks in that direction.

Few areas in North Carolina produced such a group of Revolutionary War leaders as did the banks of the Northeast Cape Fear River. Buried in a well-marked tomb in the ancient cemetery is John Alexander Lillington (c. 1720–86), the first of this eminent group you’ll meet on this tour.

Reared in the Cape Fear by his uncle, Edward Moseley, who was perhaps the colony’s most important political figure in the first half of the eighteenth century, Lillington participated in Stamp Act protests in 1765 and 1766. But like many of his contemporaries, he served as an officer in Royal Governor Tryon’s campaign against the Regulators.

Soon thereafter, he became enmeshed in revolutionary activities in the Cape Fear. Lillington’s finest hour came on February 27, 1776, when he and fellow colonel James Moore masterminded the stirring Patriot victory at Moores Creek Bridge. Less than two months later, the Fourth Provincial Congress named Lillington commander of the Sixth Regiment of the North Carolina Continentals, but he declined, citing his advanced age. A militia general for the duration of the war, he rendered effective assistance to Benjamin Lincoln at Charleston and helped defend the Cape Fear area against British and Tory raiders.

Surrounded by a crumbling brick wall, the unkept Lillington cemetery is one of the many isolated shrines of Revolutionary War North Carolina that will soon be lost unless efforts to preserve them are taken. It is located on the grounds where the great plantation house Lillington Hall once stood. Although the manor house was spared the torch during the Revolution by Tories who had great respect for Lillington, it went up in flames at the hands of invading Union troops during the Civil War.

Retrace your route to S.R. 1520. Turn left and proceed 3.4 miles to N.C. 210. Turn right and drive west 1.1 miles to the bridge over the Northeast Cape Fear River.

Several miles down the river from this span were the plantations of Maurice Moore and his son, James. Maurice Moore (1682–1743) was one of the first settlers of the Cape Fear. He was the founder of Brunswick Town, the site of an armed protest against the Stamp Act by Cape Fear residents in 1766.

James Moore (1737–77) led the protest march on Brunswick Town and subsequently became one of the early heroes of the Revolution. An excellent soldier, he served as an officer in the French and Indian War and as the commander of Royal Governor Tryon’s artillery at the Battle of Alamance. But four years later, when the news of the Battle of Lexington reached the Cape Fear, Moore made the appeal that led to the First Provincial Congress in New Bern. Thereafter, he assumed a leadership role in the revolutionary movement that took hold in the colony.

At its meeting in Hillsborough in August 1775, the Third Provincial Congress named Moore commander of the First North Carolina Regiment of the Continental Army. Six months later, Colonel Moore executed the brilliant Patriot victory at the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge. Two days after the battle, the Continental Congress promoted him to the rank of brigadier general and gave him command of all Continental troops in North Carolina. In the autumn of 1776, General Moore was elevated to the command of the Southern Department of the Continental Army upon the recall of General Charles Lee to the North.

When orders came in February 1777 for Moore to march the North Carolina regiments north to aid George Washington, he set out from South Carolina to the Cape Fear to prepare for the campaign. En route, he came down with a case of “swamp fever.” Moore never recovered. He died at his plantation on the Northeast Cape Fear on April 15.

Military scholars have concluded that George Washington’s brilliant victory at Princeton on January 3, 1777, was based on the tactics devised and used by Moore almost a year earlier at Moores Creek.

Local tradition maintains that Moore and his brother, Maurice Jr., a noted colonial jurist and early Patriot who died on the same day as James, are buried in the tangled undergrowth of the old plantation site several miles downriver from the current tour stop.

Continue west on N.C. 210 for 2.8 miles to U.S. 117 at the village of Rocky Point. State historical markers for Maurice Moore, Sr., James Moore, and Alexander Lillington stand here. The Moore plantation was located along the river 3 miles southeast of the markers.

Turn right on N.C. 117 and drive north for 0.7 mile to the state historical marker for General John Ashe.

One of North Carolina’s greatest heroes in the early days of the Revolution, Ashe (1705–81) was the son of noted colonial official John Baptista Ashe. Reared in the Cape Fear, John Ashe constructed a magnificent plantation house, Green Hill, when he reached manhood; the home was located east of the current tour stop on the Northeast Cape Fear.

Ashe was a leader in the Stamp Act protests at Wilmington and Brunswick Town in 1765 and 1766 and in the torching of Fort Johnston at Smithville a decade later. As a militia officer, he fought with distinction under the command of his brother-in-law, Colonel James Moore, at the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge. His heroism was rewarded when he was appointed a brigadier general.

A little over two years later, Governor Caswell promoted him to lieutenant general. In early 1779, Caswell dispatched Ashe and a large command of untrained troops to reinforce General Benjamin Lincoln, then the commander of the Continental Army in the South. On February 25 of that year, almost three years from the day he had enjoyed the sweet taste of victory at Moores Creek Bridge, Ashe failed miserably in his attempt to aid Lincoln at Briar Creek, located 45 miles south of Augusta. As a consequence, Georgia fell to the British.

Ashe returned to North Carolina in disgrace. His request for a trial by court-martial was granted. Although he was exonerated of cowardice, he was censured for his lack of foresight.

Forced into hiding when Wilmington came under British occupation, Ashe was betrayed, taken prisoner, and placed in Major Craig’s infamous open-air “Bullpen” in the port city. During his long confinement, Ashe contracted smallpox. Seriously ill at the time of his release, he died soon thereafter.

Continue north on U.S. 117 for 2.4 miles to S.R. 1411. At this intersection stands a state historical marker for Samuel Ashe, who, like his brother, John, rendered distinguished service in creating an independent North Carolina. To see his grave, turn right on S.R. 1411 and proceed 3 miles to the family cemetery, located approximately 0.5 mile past the site of Ashe’s plantation, “The Neck.” His prominent gravestone acclaims him as “a leader in preparing plans for the Revolutionary War and framing the Constitution of North Carolina.”

Educated as an attorney, Samuel Ashe (1725–1813) organized groups and committees of like-minded men—men with the revolutionary spirit, that is—in the Cape Fear as early as 1774. In 1776, while his brother was serving as a military leader, Samuel ascended to the presidency of the thirteen-man North Carolina Council of Safety. In that position, he supervised the affairs of state.

In one of his first official acts under the new state constitution that Ashe helped draft, Governor Richard Caswell appointed the Cape Fear Patriot to convene the first court of the state of North Carolina. Ashe thus served as the first state judge. He was also elected the Speaker of the state senate by the first legislature convened under the new constitution.

As the judicial and legislative leader of the state through the Revolution, he remained a fiery Patriot. In 1779, with the outcome of the war very much in doubt, Ashe expressed his undying desire for liberty this way: “The feelings of a few men, for himself and for his country, ready to be enslaved, warmed me into resentment, impelled me into resistance, and determined me to forego my expectations and to risk all things rather than submit to the detested tyranny.”

In 1795, Ashe stepped down as presiding judge over the state court after twenty years of service. His retirement from the judiciary was necessitated by his election as governor. He went on to serve three terms as the state’s chief executive.

Retrace your route to the junction with U.S. 117, turn left, and go south for 7.5 miles to N.C. 133. Go right on N.C. 133 and drive 4.9 miles to N.C. 210. Turn left and follow the route west for 6.7 miles to Moores Creek National Battlefield.

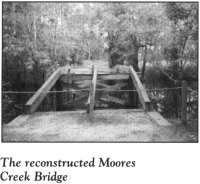

It was at this site on the bitterly cold February 27, 1776, that North Carolina Patriots won what some historians have called the first decisive American victory of the Revolutionary War. Begin your visit to the eighty-six-acre complex at the visitor center, where an audiovisual program and attractive exhibits and displays tell the story of the events that took place here more than four months before the Declaration of Independence.

On January 10, 1776, Josiah Martin, the exiled Royal governor, appealed to loyal subjects in the colony to unite and quell the rebellion. In response to his call to arms, sixteen hundred Highland Scots and Tories gathered at Cross Creek (modern Fayetteville). Commanded by General Donald MacDonald, a British army officer and a veteran of the Battles of Culloden and Bunker Hill, these Loyalist troops prepared to march to Wilmington, where they would join a British expeditionary force from Ireland to form an army of sufficient strength to end insurrection in the colony.

Meanwhile, Colonel James Moore, the commander of Patriot forces in southeastern North Carolina, busied himself with plans to thwart MacDonald’s forces. No sooner did the Loyalists begin their march from Cross Creek than Moore blocked their path. Consequently, MacDonald altered his course by crossing the Cape Fear en route to Corbetts Ferry on the Black River. There, he planned to avoid Colonel Richard Caswell’s militia forces approaching from New Bern. MacDonald would then send his men across the bridge at Moores Creek and on to the rendezvous point at Brunswick Town. (At the time, the swampy creek, which rises in northwestern Pender County and flows into the Black River, was known as Widow Moore’s Creek, as it flowed past land owned by Elizabeth Moore, a widow.)

All seemed well for the Loyalists when MacDonald reached Corbetts Ferry. But Moore countered by dispatching Caswell to Moores Creek, where he was reinforced by a Patriot force under Colonel Alexander Lillington.

On the night of February 26, Caswell and his 800 men camped on the western side of the creek and Lillington and his 150 soldiers on the eastern side. Halfway between Moores Creek and Wilmington, James Moore posted another force of Patriots as a roadblock.

Some 1,500 Loyalists were encamped approximately 6 miles from Caswell on the same side of the creek. Aware that Caswell was in a vulnerable position, MacDonald summoned a council of war, at which it was decided—against MacDonald’s better judgment—that an attack should be launched. While final preparations were being made for the offensive, MacDonald fell ill, which forced his chief lieutenant, Lieutenant Colonel Donald McLeod, to assume command.

In the early-morning darkness on February 27, McLeod put his troops, armed with broadswords and claymores, on the march through the swampy terrain. After a tedious five-hour trek in frigid temperatures, the Loyalists reached Caswell’s camp about an hour before light. To their dismay, it was abandoned. Caswell had pulled his forces to the other side of the creek during the night but had left the campfires burning in a ploy to trick would-be attackers. After his men had crossed the bridge over the creek, Caswell had ordered its planks removed and the girders greased. At their new base on the eastern bank, the Americans had thrown up fortifications and positioned artillery to cover the road and bridge.

The Loyalists regrouped and waited for first light at Caswell’s abandoned camp, believing the enemy forces were in retreat. Instead, Caswell and Lillington were waiting just across the dismantled bridge.

As the sun rose, the rallying cry was passed among McLeod’s troops. Suddenly, gunfire near the bridge broke the stillness of the swamp. McLeod ordered his forces forward. Three cheers were offered, and then the attackers called in unison, “King George and Broadswords!” Drums rolled and bagpipes played as the soldiers moved forward in battle formation.

Most of McLeod’s soldiers were killed as they attempted to cross the creek. Others were wounded, fell into the cold water, and drowned. McLeod, Captain John Campbell, and a small number of their charges were able to make their way over the slippery bridge skeleton. But as soon as they reached the eastern bank, they walked into a hail of bullets. Both McLeod and Campbell were mortally wounded. McLeod fell only a few feet from the Patriot defenses. He attempted in vain to stand once again and spent the last moments of his life shouting encouragement to his soldiers and waving his sword toward the enemy. A post-battle examination revealed that he had taken nine bullets and twenty-four “swan shot.”

His bravery was for naught, because the battle was over almost as soon as it began. In three minutes, the Loyalists suffered eighty casualties. The survivors retreated wildly through the swamps to their previous camp, where they reported the debacle to General MacDonald. A short time later, the Loyalists’ attempt to escape failed when their relentless pursuers captured MacDonald and his defeated army.

The Battle of Moores Creek Bridge produced effects that reached far beyond the swamps of southeastern North Carolina. Royal authority was forever ended in North Carolina by the short but decisive Patriot victory. Moreover, the Patriots’ strong stand here allowed North Carolina to remain free of British troops for most of the Revolutionary War.

In political terms, the victory provided the impetus for North Carolina legislators to be the first in the colonies to instruct their delegates at the Continental Congress to vote for independence.

It was the foresight of subsequent state legislators that preserved the battlefield site. In 1898, the North Carolina General Assembly purchased the historic grounds for a state park. When Congress created Moores Creek National Military Park on June 2, 1926, the state ceded the site to the federal government.

Several trails lead from the visitor center to where the fighting took place in 1776. Located along the paths are a number of impressive monuments and markers, two of which are of particular interest.

The Mary “Polly” Hook Slocumb Monument towers above the graves of Ezekial Slocumb and his wife, Polly. In 1930, the remains of this legendary couple were moved from their original grave site in Wayne County.

Long regarded as one of North Carolina’s greatest Revolutionary War heroines, Polly Slocumb, as the legend goes, left her infant son in the care of a servant and made a 50-mile ride through the swamps from her home to Moores Creek after a premonition warned her that Ezekial had been wounded in the battle. Upon her arrival, she found her husband alive and well, and she immediately set about ministering to the wounded Americans. Her diary provides a vivid account of this heroic adventure.

In recent years, however, this long-cherished tale has been challenged by historians, who cite records that indicate Ezekial was only fifteen years old at the time of the battle. Indeed, his pension papers reveal that he did not join the armed forces until April 1780, more than four years after Moores Creek. Furthermore, Jess Slocumb, the only son of Ezekial and Polly—the infant left with a servant during the famous ride, presumably—listed his date of birth as 1780 when he was subsequently elected to Congress.

Still, Polly Slocumb has not been knocked off of her pedestal at Moores Creek. Her monument remains one of the most honored places on the battlefield.

The Grady Monument (or Patriot Monument) is the oldest stone monument in the park. It honors the memory and sacrifice of Private John Grady, the only Patriot soldier to lose his life at Moores Creek. In 1857, on the eighty-first anniversary of the battle, his remains were disinterred from his original grave in Wilmington, placed in a small lead box, brought here, and laid in the foundation of the monument. When the monument was relocated in 1974 to restore the battle site to its original condition, an examination of the water-filled lead box revealed bone fragments, teeth, a soggy piece of cloth, and some paper that may have once been a Bible.

Beyond the monuments, a trail leads to the reconstructed bridge. A nearby boardwalk crosses the creek to Richard Caswell’s campsite.

When you are ready to leave the battlefield complex, drive west on N.C. 210 for 6.8 miles to N.C. 11 near the Bladen County line. Turn left on N.C. 11 and drive south for 4.8 miles to the bridge over the Cape Fear River. North of the bridge is Lock No. 1 of the mighty river.

Continue south on N.C. 11. On the southern side of the bridge, you will enter Columbus County. One of the largest counties of the state, it was formed in 1808 and named for Christopher Columbus.

After 1.3 miles, N.C. 11 intersects N.C. 87. Turn left on N.C. 87 and proceed southeast for 0.2 mile to Weyman Methodist Church, located on the left.

In the forest near the cemetery of this late-nineteenth-century frame structure is what is purported to be the grave of the highest-ranking Revolutionary War officer from the states south of Virginia. The grave was graced by a D.A.R. marker in 1932.

At the close of the war, Major General Robert Howe ranked seventh in seniority among American generals and enjoyed the respect and admiration of George Washington. But despite his high rank, Howe holds the dubious distinction of being the forgotten man of Washington’s inner circle.

Born in 1732 in Brunswick County, Howe was still a young man when he inherited a fortune from his father and his grandmother, the daughter of the governor of South Carolina.

At its meeting in Hillsborough in August 1775, the Third Provincial Congress created two regiments for the newly authorized Continental Army. James Moore and Robert Howe were commissioned as colonels of the First and Second Regiments, respectively. Colonel Howe took his troops onto the battlefield for the first time in Virginia in late November, at which time he won the respect and admiration of his fellow officers. Four months later, he was promoted to brigadier general.

In August 1777, the command of the Southern Department of the Continental Army devolved to Howe. His promotion to major general followed in October. Political problems in Georgia and South Carolina resulted in Howe’s reassignment to George Washington’s headquarters in September 1778. But before Major General Benjamin Lincoln, Howe’s replacement, arrived in the South, Savannah fell to the British. Much of the blame was wrongfully placed on Howe’s shoulders.

In the North, Howe proved to be one of Washington’s most competent subordinates. At Washington’s request, he presided over the court-martial of Benedict Arnold, which resulted in the conviction of the man remembered as America’s most infamous traitor. Howe later sat as a member of the military tribunal that condemned Arnold’s British conspirator, Major John André.

Following the war, President Washington and Secretary of War Benjamin Lincoln gave Howe little hope that the postwar army would need a major general, and Howe came to the realization that his military career was at an end. Devastated financially by the war, he went to work restoring his Brunswick County plantation, which had been ravaged by the enemy in his absence.

Howe was en route to Fayetteville for a meeting of the general assembly when he died on November 20, 1786, at a site near the current tour stop.

Buried in a well-marked grave in the nearby church cemetery is Elizabeth Hooper Waters, the last surviving child of William Hooper.

Continue south on N.C. 87. It is 1.4 miles to a state historical marker noting the route Cornwallis and his army used on their march from Guilford Courthouse to Wilmington in April 1781.

It is another 1.7 miles on N.C. 87 to U.S. 74. Turn right, drive 10.7 miles to N.C. 211 at the town of Bolton, turn right again, and proceed 3.4 miles to S.R. 1740. Turn left and go 0.1 mile to Shiloh Methodist Church.

In the front yard of this church stands an eight-foot monument honoring Duncan King. His grave and that of his wife, Lydia, are located nearby. Theirs was a storybook tale of fate, love, and romance.

When Captain Duncan King, a young Scottish privateer in the service of the Crown, made port at the mouth of the Cape Fear in 1752, he brought with him a precious cargo—he had rescued a five-year-old French girl, Lydia Fosque, from a Spanish pirate ship. Lydia’s parents had been killed when Spanish raiders attacked the merchant ship on which the Fosque family was sailing. At Fort Johnston, Duncan placed her in the care of Mrs. Holmes, a French-speaking settler who lived in the area.

Duncan returned to his career at sea and subsequently saw service in the British army during the Battle of Quebec. Meanwhile, in North Carolina, Lydia grew into a teenager of breathtaking beauty.

In 1761, Mrs. Holmes decided that she and fourteen-year-old Lydia should move to Savannah. As the two women waited on the dock at Fort Johnston for the ship that was to take them to Georgia, another vessel made port. Down the gangplank walked Duncan King. After years at sea, he had come to North Carolina to settle.

Smitten by Lydia’s beauty, Duncan fell in love with her, and she with him. After they courted briefly, Mrs. Holmes consented to their marriage.

Although Duncan had been rewarded for his military service with sizable land grants in New England, he chose to build a plantation on several thousand acres on the banks of the Cape Fear River at a site still known as Kings Bluff, located near the present tour stop.

During the Revolution, despite pronouncements by the aged Duncan that he intended to remain neutral and wanted no part of the fighting, local Patriots were suspicious of him because of his prior service as a British soldier. On one occasion, as Lydia was returning home from religious services, she was confronted by a group of Patriots who sought information about Duncan’s whereabouts. Without replying, she dug her spurs into her mount and raced home to warn her husband. Her fleet horse beat her pursuers by just the amount of time necessary for Duncan to hide. When the angry Patriots arrived, they demanded to know why Lydia had galloped away. Using her charm to calm a volatile situation, she remarked that she had assumed guests would be staying to eat, so she had hurried home to make sure that dinner would be ready.

Duncan and Lydia lived at Kings Bluff the rest of their lives. Duncan died in 1793 and Lydia in 1819. Descendants of this remarkable couple have included Civil War leaders, the founder of Kings Business College, and a vice president of the United States, William Rufus King.

Return to N.C. 211 and proceed north for 0.4 mile to the Bladen County line. An ancient county, Bladen was founded in 1734 and named for Martin Bladen (1680–1746), an English soldier and politician.

Continue north on N.C. 211 for 3.2 miles to S.R. 1730 at the community of Council. Turn right and proceed 4.3 miles to N.C. 87. Here stands a historical marker for Oakland Plantation, a nearby Revolutionary War site. To see it, proceed across the intersection on S.R. 1730 for 1 mile. Oakland stands on the left at the end of a long driveway marked by eagle statuary.

The two-story, brick plantation house is on a bluff overlooking the Cape Fear River. Adorned with double piazzas both front and rear, it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is among the best preserved of the few surviving plantations on the river. Not open to the public, this spectacular plantation manor house was built in the late eighteenth century for General Thomas Brown (1744–1811), a local Revolutionary War hero.

Brown took part in the campaign against the Regulators at Alamance, but soon thereafter, his allegiance shifted to the growing independence movement. At the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge, he rendered distinguished service as lieutenant colonel of the Bladen County militia. In recognition of his gallantry, he was promoted to full colonel. Later in 1776, Brown served as a delegate to the Fifth Provincial Congress and assisted in the formation of the state’s first constitution.

From 1777 through 1780, Bladen County was free of British troops. During that time Brown, used his militia to suppress Tory activities in the area. A stalwart Patriot, he was known for his vigorous pursuit of Loyalists.

Matters changed after British troops landed in Wilmington in January 1781. Their raiding parties fanned out across southeastern North Carolina and instilled a renewed fighting spirit in the Tories. Brown and his militiamen were forced to take refuge in the area’s swamps and wilderness.

His greatest moment came in August 1781, when he helped mastermind a bold raid by a small band of Patriots that culminated in the dramatic American victory at the Battle of Elizabethtown, the site of which is visited later in this tour.

Retrace your route to N.C. 87. Turn right and drive northwest for 16.7 miles to the intersection with N.C. 41 and U.S. 701 in downtown Elizabethtown, the seat of Bladen County. Park on N.C. 87 (Broad Street) near the Bladen County Courthouse and walk to the courthouse grounds, where two small markers pay tribute to the unheralded but significant battle that took place near here in August 1781.

When eyewitness accounts of the Battle of Elizabethtown began to appear in print in the early part of the nineteenth century, no two of them agreed on the details of the event. Nevertheless, some facts of the fascinating story are incontrovertible.

During the summer of 1781, Elizabethtown was in the center of an area under Tory control. To the west, supporters of the notorious Tory leader David Fanning (see The Regulator Tour) held sway. To the north, Cross Creek (Fayetteville) was under Loyalist dominance. To the southeast, Wilmington was occupied by British troops. Four hundred Tory soldiers under Colonel John Slingsby, a native of England, were encamped in Elizabethtown proper. From this base, they carried out raids into the surrounding countryside, ravaging the plantations of local Patriots.

Meanwhile, the local Patriot militia holed up in Duplin County had dwindled to seventy men. Armed with long rifles and equipped with worn-out horses, the small band under the immediate command of Colonel Thomas Robeson, Jr., marched toward Elizabethtown in late August. They vowed to drive the Tories from the town or die in the attempt.

In the early-morning darkness on August 29, the Patriots left their horses with an attendant, undressed, tied their clothing and ammunition on their heads, and made their way across the Cape Fear. Cognizant that they were outnumbered, they realized that they could only prevail through strategy and cunning.

Whether Robeson or Thomas Brown was in overall command of the attack is uncertain. Some accounts indicate that Brown was recovering from wounds and had conferred the command on Robeson. At any rate, it was Robeson who led the predawn assault on the unsuspecting Tory encampment and perpetrated one of the greatest battlefield ruses of the war.

The small army divided into three companies, each detail approaching the enemy from a different direction. At a given signal, the Patriots charged forward yelling, “Washington!” Their initial volley of musket fire spread panic throughout the Tory camp. From the center of the line, Robeson shouted out orders to phantom companies in a loud, clear voice: “On the right! Colonel Dodd’s Company! Advance! On the left! Colonel Gillespie’s Company!”

Colonel Slingsby and fifteen Tory soldiers fell mortally wounded. Fearing that they were being attacked by Washington’s army, the surviving Tories fled helter-skelter toward a deep ravine located just north of the current tour stop. Many of the frightened soldiers plunged headlong into it in an attempt to escape. Since that day, the ravine (now filled) has been known as Tory Hole.

By the time the smoke cleared, seventeen Tories were dead and many others lay wounded. Among the Patriots, no men were killed and only four were wounded. Although the battle was small in terms of the number of soldiers involved, it was important because it brought a sudden and final end to the power of the Tories along the Cape Fear.

One of the markers on the courthouse grounds, a bronze plaque on a granite boulder, gives a brief account of the battle.

The other is a stone marker that pays homage to the battle’s heroine. Sallie Salter (1742–1800), a member of a distinguished local family, volunteered to make her way into the Tory camp under the guise of selling eggs. Upon completing her mission of espionage, she hurried to Colonel Robeson with a detailed account of the camp. Aided by this information, Robeson crossed the river 1 mile south of the town and launched his main attack from that direction.

From the courthouse, walk one block west on Broad Street and cross over to the northern side of the street to see the state historical marker for the Revolutionary War battle fought here. Near the marker is a covered walkway known as “Tory Hole Alley.”

Return to your vehicle. Turn right off N.C. 87 onto U.S. 701 and proceed 0.2 mile north to the entrance to Tory Hole Park, located on the left along the banks of the Cape Fear. Named for the nearby gully into which the fleeing Tories plunged in 1781, the park offers picnic facilities, hiking trails, and a boat landing in a picturesque, forested setting.

Follow U.S. 701 across the bridge over the Cape Fear. Approximately 1 mile north of the bridge, turn left on N.C. 53. Drive 10.1 miles northwest to S.R. 1318. Located at this junction near a small roadside park is a historical marker for Harmony Hall, which dates from the Revolutionary War era. To reach it, turn left on S.R. 1318, travel southwest for 1.6 miles to S.R. 1351, and turn left. At the end of S.R. 1351 stands Harmony Hall.

Open to the public on a limited basis, this simple, stately, two-story plantation house was constructed prior to 1768 on the twelve-thousand-acre river-side land grant of Colonel James A. Richardson, a native of Stonington, Connecticut, who settled in Bladen County after being shipwrecked off the North Carolina coast at Cape Hatteras.

Richardson was an officer under Nathanael Greene at the time Cornwallis came calling at Harmony Hall in early April 1781. While the British commander was using the house as his headquarters, Colonel Richardson’s wife overheard a strategy-planning session between Cornwallis and his staff. Through the plantation overseer, she promptly relayed the intelligence to Greene, who used the information to great advantage in his military campaign in South Carolina.

By the early 1960s, Harmony Hall had fallen into disrepair, and the plantation grounds were an overgrown wilderness. A 1962 effort to restore the house met with little success. It was not until the general assembly appropriated $150,000 in 1986 that serious restoration efforts began. Since that time, the historic structure and a sizable portion of the plantation lands have become a regional showplace.

Retrace your route to S.R. 1318. Turn left, drive 3 miles west to S.R. 1316, and turn left again. It is 0.9 mile to the river bridge, which provides another spectacular vista of the Cape Fear. Once across the bridge, continue on S.R. 1316 for 0.9 mile to N.C. 87 at the village of Tar Heel. One of the several possible origins of the town’s name dates from Revolutionary War days, when British troops gave North Carolinians a new nickname upon emerging from a river with tar on their heels (see The First for Freedom Tour, pages 52–53).

Turn left on N.C. 87 and drive 0.5 mile southeast to the state historical marker for Thomas Robeson, Jr., one of the heroes of the Battle of Elizabethtown. The marker stands on the left side of the highway at Robeson’s former homesite. Visible from the highway is Walnut Grove, the magnificent plantation mansion constructed by James Robeson in 1855 on the site where his father was born and grew up. The estate is not open to the public.

Thomas Robeson, Jr. (1740–85), served as a delegate at the Fourth Provincial Congress in Halifax in April 1776 and as a member of the first general assembly of the independent state of North Carolina.

Although Tories outnumbered Whigs by five to one in Bladen County, Robeson was an ardent Patriot. He fought as a militia officer at the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge. For the duration of the conflict, he was a Whig leader in the civil war that raged throughout southeastern North Carolina. Using his own personal fortune, he paid the soldiers under his command in order to maintain opposition to local Tories. He never recovered the eighty thousand dollars he spent to further the fight for American independence.

Turn around near Walnut Grove and drive north on N.C. 87. It is 8.3 miles to the Cumberland County line. Formed in 1754 from Bladen County, Cumberland was named for William Augustus, duke of Cumberland (1721–65), the son of King George II and the commander of the victorious English troops at the Battle of Culloden. Ironically, this county, named for a man known as “the Butcher” because of his savagery against his Scottish adversaries, was settled primarily by Scottish Highlanders.

From the county line, it is 7.5 miles north to a state historical marker that calls attention to the site where General James Moore camped from February 15 to February 26, 1776, prior to the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge. Moore and his troops made their temporary home on the banks of Rockfish Creek 1.5 miles north of the marker.

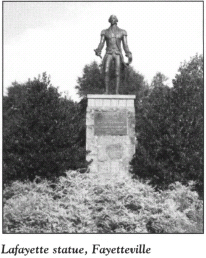

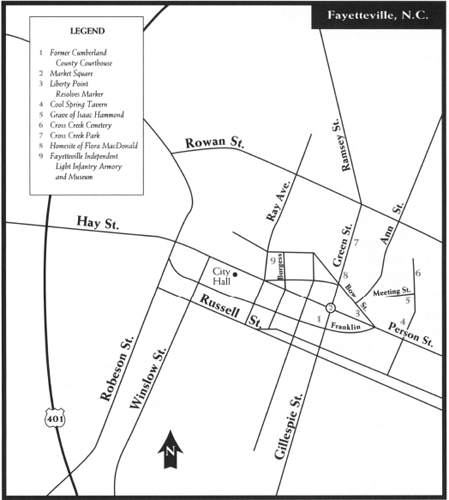

Continue north on N.C. 87 (now alternately known as Elizabethtown Road/Wilmington Highway) for 5.7 miles until the junction with Gillespie Street entering Fayetteville. In the 100 block of Gillespie near the former Cumberland County Courthouse is a state historical marker honoring the man for whom the city was named. During his triumphant visit on March 4 and 5, 1825, the Marquis de Lafayette stayed at the home of Duncan McRae, which stood at the courthouse site.

Lafayette first came to America in 1777 as an inexperienced nineteen-year-old French soldier. Four years later, as a major general in the Continental Army, he pinned down Cornwallis at Yorktown and won the hearts of George Washington and the young American nation. Upon his return to the United States forty-four years later, the aging general toured every American state and became the first foreigner to address both houses of Congress.

Of all the places Lafayette visited on his victory tour, it was perhaps Fayetteville that stirred his proudest feelings. When the city changed its name from Campbellton to Fayetteville in 1788, it became the first in the United States to be named in honor of the most revered foreign soldier of the Revolution. Today, ten Fayettevilles, eleven towns (and fourteen counties) known as Fayette, and one Fayette City are scattered throughout the United States. This North Carolina city is both the oldest and the largest such town.

Proceed one block north on Gillespie Street to Market Square, the site of the city’s most famous landmark. Market House, erected in the heart of old Fayetteville at the intersection of Green, Gillespie, Person, and Hay Streets, was constructed in 1832 on the foundations of the old State House, which was destroyed by fire in 1831.

At this site on November 16, 1789, Governor Samuel Johnston called the North Carolina Constitutional Convention to order. Its mission was to ratify the United States Constitution. There were 294 delegates on hand, representing fifty-nine counties and six towns.

The state legislature met here on December 11, 1789, and enacted a bill sponsored by General William R. Davie to charter the University of North Carolina, the first state university in the new nation.

Impressive in design, the existing brick structure was inspired by its predecessor. The second-story municipal hall is topped by a cupola with a clock and a bell tower. Plaques attached to the open-air columns of the first floor attest to the important events that took place here after the Revolution.

At Market Square, traffic flows counterclockwise into a circle around Market House. Enter the circle from Gillespie and bear right onto Person Street, named for Revolutionary War hero Thomas Person. (For information about Person, see The Statehood Tour, pages 425–456.)

Proceed one block east to Bow Street. A stone marker at the junction pays tribute to the Liberty Point Resolves (actually entitled the Cumberland Association), a manifesto signed by fifty-five local Patriots on June 20, 1775. Inscribed on the marker are the names of thirty-nine of the daring men who affixed their signatures to the document, which boldly declared, in part,

We, therefore, the subscribers, of Cumberland County, holding ourselves bound by the most sacred of all obligations, the duty of good citizens toward an injured country, and thoroughly convinced that, under our distressed circumstances, we shall be justified in resisting force by force, do unite ourselves as a band in her defense against every foe, hereby solemnly engaging that whenever our Continental or Provincial Councils shall decree it necessary, we will go forth and be ready to sacrifice our lives and fortunes to secure her freedom and safety.

Unlike the highly controversial Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence, allegedly signed about a month earlier, the original of the Liberty Point Resolves still exists. It was found in the Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina by Fayetteville researcher David Clark in 1975.

The first signature affixed to the document is that of Robert Rowan, who is believed to have been its draftsman. Rowan’s language was daring for its time, particularly in a place dominated by people whose allegiance lay with the British Crown.

Continue east on Person Street for 0.2 mile to North Cool Spring Street and turn left. Located at 119 North Cool Spring is Cool Spring Tavern. Built between 1788 and 1789 by Dolphin Davis to house delegates at the North Carolina Constitutional Convention, the massive, two-story frame building with double piazzas is the oldest structure in Fayetteville.

In the same block as Cool Spring Tavern but on the opposite side of the street is a historical marker at the spot where, according to tradition, Flora MacDonald bade farewell to her husband, Allan, and his band of Scottish Highlanders as they marched off to do battle at Moores Creek Bridge.

Flora MacDonald (1722–90) was the most famous woman in North Carolina during the Revolution. Born in Scotland, she achieved worldwide fame in her native land long before settling in the colony in 1774. When Charles Edward, the Stuart pretender to the British Crown, decided to challenge the Hanover family for the right to hold the monarchy in 1745, he went to Scotland to muster support for his cause. Flora was among his most devoted backers there.

Bloody warfare ensued. In the wake of his crushing victory over the Scots at Culloden, the duke of Cumberland was intent upon capturing “Bonnie Prince Charlie” in order to prevent further resistance from the people of Scotland. At the very moment when it seemed the prince would be taken prisoner on the Scottish island of Skye, Flora masterminded his miraculous escape to France. For her efforts, she became a heroine in Scotland and an outlaw in England.

Arrested for her part in the conspiracy, she was imprisoned first in Scotland and then in the Tower of London. During that time, grateful Scottish citizens lavished gifts upon her. In 1750, three years after her release, she married Allan MacDonald.

When the MacDonalds made port in Wilmington in 1774, they were welcomed as heroes and feted at a grand ball. They stayed but a short time there, choosing instead to come to the town now known as Fayetteville, where they enjoyed another grand reception hosted by Scottish Highlanders, some of whom they had known across the sea. For almost six months, Allan, Flora, and the three children who had accompanied them to America lived in town while they surveyed the surrounding countryside for a place to settle. They subsequently lived at several places in the area, some of which are visited later in this tour.

Flora and her family arrived in North Carolina at a time when tensions were mounting between the colony and the Crown. Although she had been a rebel in her native land, Flora, ever true to the oath she had taken, was a staunch Tory in her new home. She rode throughout the area demanding that her fellow Scots remain loyal to King George III and seeking volunteers to fight against the American rebels. Allan was appointed lieutenant colonel in the Royal Highland Emigrant Regiment, headquartered at Halifax, Nova Scotia. In that role, he was responsible for recruiting Loyalist troops in North Carolina.

In mid-February 1776, Flora stood on the steps leading to Cool Spring, a tributary of Cross Creek, to cheer and inspire the sixteen hundred Highlanders whom Allan had assembled. After the grand send-off, the soldiers, under the overall command of General Donald MacDonald, marched to their devastating defeat at Moores Creek Bridge.

Allan was taken prisoner in the battle. Because of her outspoken loyalty to the Crown, Flora suffered great hardships in the aftermath of Moores Creek Bridge. Not only was she harassed by local citizens sympathetic to the American cause, but her plantation was raided and plundered. Finally, in October 1777, after living in terror for almost twenty months, she fled to Nova Scotia, where she joined Allan, who had been released from prison.

Continue on Cool Spring Street. Just north of the MacDonald marker, you will pass across Cross Creek, the historic waterway that flows from northern Cumberland County through Fayetteville to the Cape Fear River.

The colonial trading center known as Cross Creek emerged along the banks of this creek around 1760. A rival settlement known as Campbellton was established about a mile away by the colonial assembly in 1762. Even though it was the seat of local government, Campbellton could not keep pace with Cross Creek. The two towns were combined by the state legislature just after the Revolution began and were known as Lower and Upper Campbellton until the present name was adopted.

Follow North Cool Spring Street to Meeting Street. In a tranquil, shaded spot at this junction stands a marker over the grave of Isaac Hammond.

Hammond, a free black man, served as a soldier and fifer in the Revolution. After the war, he was a musician in the Fayetteville Independent Light Infantry, which survives today as the second-oldest active militia in the United States. When death came calling, Hammond is said to have begged to be buried here with his fife: “I shall maybe hear the drum and the fife of the company every parade day when the men throng at the spring, and the sound will gladden me in the long, long sleep of the tomb.”

Cross Creek Cemetery is located a bit farther north on the opposite side of Cool Spring Street. Established around 1785, this beautiful, shaded cemetery is one of the most historic in eastern North Carolina. A retaining wall of handmade brick on the southern edge of the graveyard is the oldest piece of construction in Fayetteville. James Hogg, a noted Patriot from Orange County, donated the tract for the original part of the burial ground.

Lying in the cemetery are some of the most prominent of the city’s early citizens, including a number of men who made their mark during the Revolution. The grave of Robert Rowan was placed here following its removal from nearby Hollybrook Plantation. Rowan’s friend and fellow signer of the Liberty Point Resolves, Lewis Barge, was laid to rest here, as was George Fletcher, who along with Rowan and Peter Mallet was named a commissioner of the combined towns. Gabriel Pubeutz, a native of Bordeaux, France, who sailed to America to assist in the fight for independence, stayed in the new nation after witnessing the British surrender at Yorktown; upon his death in Fayetteville, he was buried in these historic grounds. Also laid to rest here was John Lumsden, a Revolutionary War soldier who lived on North Cool Spring Street; Lumsden hosted renowned Methodist minister Francis Asbury on the cleric’s early visits to Fayetteville.

Turn left off North Cool Spring onto Grove Street, named for William Barry Grove, a delegate to both North Carolina Constitutional Conventions. The stepson of Robert Rowan, Grove was elected to the First Congress of the United States.

After two blocks on Grove, turn left onto Green Street, then go one block south to Cross Creek Park. Landscaped by New York architects, this municipal greenway offers a scenic walkway along cypress-shaded Cross Creek, where the city was born. A large statue of Lafayette, purchased in 1983 by the Lafayette Society, was erected in the park to commemorate the two hundredth anniversary of the naming of the city.

Continue south on Green Street to Bow Street. Allan and Flora MacDonald lived at the northeastern corner of this junction in 1774. A small marker stands at the site.

Follow Green Street south to the traffic circle at Market Square. Proceed counterclockwise into the circle and exit onto Hay Street. In former days, the Donaldson Hotel stood at the southeastern corner of Hay and Donaldson Streets. It was the site of the grand ball held in Lafayette’s honor when he visited in 1825.

Continue one block west on Hay to Burgess Street. Turn right and drive two blocks to the Fayetteville Independent Light Infantry Armory and Museum, located near the junction of Burgess Street and Maiden Avenue.

Included in the museum’s collection are documents, uniforms, and artifacts from more than two centuries of service by the military company. Without question, its most prized possession is the carriage Lafayette rode in during his visit to the city.

During his stay, the French general was welcomed by the governor of North Carolina and the most prominent citizens of the area. Toasting his hosts, Lafayette remarked, “Fayetteville—may it receive all the encouragements and obtain all the prosperity which are anticipated by the fond and grateful wishes of its affectionate and respectful namesake.”

Of all the local citizens who greeted the aging hero, one had the greatest impact. As a teenager, Isham Blake had served as a fifer and bodyguard for Lafayette in the latter stages of the Revolution. He had last seen his commander during the surrender ceremonies at Yorktown. While Lafayette was in Fayetteville, Blake called at the home of Duncan McRae. Word was promptly sent to Lafayette that one of his old soldiers wanted to see him. Blake and Lafayette embraced warmly as tears flowed from their eyes. As soon as the general regained his composure, he called on his fifer to once again play a tune for him.

Turn east off Burgess onto Maiden Avenue and drive to Green Street. Turn left and follow Green to Grove Street. En route, you’ll pass two state historical markers. One pays tribute to Robert Rowan and notes that his grave is in Cross Creek Cemetery. The other commemorates the visit of Cornwallis and his army to Fayetteville. On April 1, 1781, they entered the town on the final leg of their march to Wilmington. Cornwallis stayed in a house that stood nearby, while his soldiers camped here along the creek banks.

Turn right onto Grove Street and proceed east for 0.3 mile to U.S. 301/I-95. Turn left and drive north for 4.8 miles to where I–95 and U.S. 301 divide. Follow U.S. 301 north for 6.4 miles to the village of Wade. One mile north of Wade, U.S. 301 junctions with S.R. 1802. Here stands a state historical marker for Old Bluff Presbyterian Church.

To visit the church, turn left on S.R. 1802 and go 0.6 mile to S.R. 1709. Turn left again and drive west for 0.5 mile. The venerable church stands at the end of the road near the banks of the Cape Fear River.

Constructed in 1858 by the oldest Presbyterian congregation in Cumberland County, the two-story Greek Revival structure stands on the site where the church was organized in 1758. Among the church’s most prized possessions are two inscribed, silver communion cups given by King George III in 1775. In 1908, the membership constructed a new brick sanctuary near Wade. Since that time, the old building has been used only for special occasions.

Graves in the adjacent cemetery date back as far as 1786. Many of the Scottish members of the early congregation are buried here, among them Colonel Alexander McAlister, who represented Cumberland County at the Third and Fourth Provincial Congresses. McAlister subsequently fought for the American cause in the Revolutionary War. A monument stands at his grave.

Another monument memorializes James Campbell (1700–1780), the church’s first minister. An ardent Whig during the Revolution, Campbell espoused the American cause from the pulpits of local Presbyterian churches until Tory threats forced him to move to Guilford County. His actual burial site is located in a family cemetery just across the river.

Around 1770, the Reverend John MacLeod was sent to the area to assist Campbell with his duties at Old Bluff and other nearby churches. It was to MacLeod that the cherished communion cups were presented by the British monarch. In sharp contrast to Campbell, MacLeod was an avowed Tory. His sermon rhetoric eventually led to his arrest while in the pulpit at Barbeque Presbyterian Church, which will be visited later on this tour. After a short imprisonment, MacLeod drowned at sea on a trip to his native Scotland.

Retrace your route to Grove Street in Fayetteville; proceed west as Grove becomes Rowan. Follow Rowan to Bragg Boulevard. Turn left on Bragg, drive south to Hay Street, turn right, go west to Bradford Avenue, and turn left. The Museum of the Cape Fear is on the right after one block.

Located in a renovated three-story building that was once a nurse’s dormitory for nearby Highsmith-Rainy Hospital, the museum offers exhibits that tell the story of early Scottish residents and the impact of the Revolutionary War on the area. It is operated as a branch of the North Carolina Museum of History. There is no admission charge.

Return to Hay Street, turn left, and go 0.3 mile. Two blocks east of the U.S. 401 overpass, Hay Street junctions with Fort Bragg Road. Merge onto Fort Bragg and travel 2.1 miles to Bragg Boulevard (N.C. 24). Turn left, follow Bragg Boulevard for 7.3 miles, and turn right on N.C. 210. It is 3.9 miles to the Harnett County line.

Continue north on N.C. 210 for 0.3 mile to S.R. 2051. Turn right and proceed south for 0.4 mile, where the road passes into Cumberland County and becomes S.R. 1798. Follow S.R. 1798 for 0.1 mile to S.R. 1200 (McCormick Bridge Road) and turn left. After 0.1 mile, you will cross the Lower Little River. Continue 0.4 mile to a dirt lane on the left protected by a chain. Some 0.4 mile down this twisting, nearly impassable path is the McNeill family cemetery. Visitors should not attempt to make their way to the cemetery without first obtaining permission from the property owners.

The isolated burial ground is situated on a knoll overlooking the Lower Little River. In it are the graves of British soldiers who died in Cornwallis’s retreat from Guilford Courthouse. But of all the markers in the historic cemetery, one towers above the rest. A tall obelisk marks the grave of Janet Smith McNeill (1720–91), one of the most fascinating women in North Carolina during the Revolutionary War.

Born in Scotland, Janet came to the Cumberland County area when her parents moved to America in 1739. Nine years later, she married Archibald McNeill. For the rest of their lives, they lived in the area near the current tour stop.

“Jennie Bahn,” as Janet was affectionately known (bahn meaning fair in Gaelic), was stunningly attractive. Petite in size, she had red hair and a fair complexion. But her size and appearance were deceiving. One observer offered this high praise: “For beauty, sprightliness, and wit, she was regarded as second to none in the Scotch settlements; and for energy of character only to Flora MacDonald.”

On the eve of the Revolution, the McNeills were said to be the largest cattle raisers in America. Legend has it that on at least one occasion, the Scottish redhead drove three thousand head to Philadelphia. On one visit to that city, Jennie Bahn met Benjamin Franklin and was greatly impressed by the American statesman. Following Jennie Bahn’s visit to the City of Brotherly Love, every succeeding generation of her family boasted of a member named Benjamin Franklin.

She also participated in driving several herds to Petersburg, Virginia. Because she could not take enough feed for the cattle, Jennie Bahn was forced to purchase it along the route. Once, when a Virginia farmer refused to sell her feed, she instructed her trail hands to dismantle his fence and drive the cows into his hayfield.

When the Revolution began, Jennie Bahn declared her neutrality. Throughout the conflict, she sold cattle to both sides. Tradition maintains that she sent three of her sons to each army, so as to protect her property from the ravages of war. In actuality, five of her six sons served with Loyalist forces. Three of them, “Nova Scotia Daniel” (named for his place of removal after the war), “Leather-eye Hector” (so named after losing his eye in a fight with his father-in-law), and “Cunning John” (named for his sly character) were noted Tory leaders.

Even the monument that marks Jennie Bahn’s grave has an intriguing story behind it. An immense shaft was crafted in Scotland and shipped to Cumberland County for placement on the grave. When the time came for it to be unloaded from a river steamer, it proved so large and heavy that it could not be lifted onto the bank. It was abandoned in the river for years, until its base was cut into foundation stones for buildings in Fayetteville. Finally, 128 years after delivery, the cap of the original monument was lifted out of the mire and placed at the grave site.

Retrace your route to the junction with N.C. 210 in Harnett County. Formed in 1855 from Cumberland County, Harnett is named for Revolutionary War hero Cornelius Harnett.

Turn right on N.C. 210 and drive 11.3 miles north to S.R. 2056. Turn right and follow S.R. 2056 for 0.3 mile to its terminus at the Lillington American Legion building, located on the banks of the Upper Little River. John McLean’s mill, one of the area’s two muster grounds for Tory soldiers during the Revolutionary War, stood near here.

Return to N.C. 210, turn right, and drive 2.2 miles to U.S. 401. Continue north on N.C. 210 for 0.4 mile to U.S. 421 in Lillington, the seat of Harnett County. Incorporated in 1859, the town was named for Alexander Lillington, one of the heroes of the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge. A spirited engagement between Whig forces under Colonel John Hinton and Scottish Highlanders under Captain John McLean took place here in 1781.

Turn right on U.S. 421 and drive west for 10.5 miles to S.R. 1229. Turn left and follow S.R. 1229 for 1.6 miles to S.R. 1280. Lord Cornwallis and his army entered Harnett County near here on April 28, 1781, on their march to Wilmington. They camped at William Buie’s plantation, which was located nearby.

To follow Cornwallis’s route through Harnett County, turn left on S.R. 1280 and drive 0.2 mile to S.R. 1215. Turn right, proceed south for 5.7 miles to S.R. 1209, turn left, and drive 0.5 mile to Barbeque Presbyterian Church, located near the junction with S.R. 1285.

Although the existing building was constructed in the late nineteenth century, the church was started in 1757 by Scottish Highlanders. One explanation of its unusual name relates to the Revolutionary War. As longstanding tradition has it, General Lafayette and his soldiers stopped at the church to feast on barbecued pigs. However, records as early as 1753 cite the name of the nearby creek as Barbeque.

On April 29, 1781, Cornwallis and his army camped at the church. His cavalry chieftain, Banastre Tarleton, engaged in a bloody encounter with Captain Daniel Buie and a small band of local Patriots. In the aftermath of the skirmish, Buie was left for dead, his head split open by a sword.

A couple of geographical landmarks on the church’s eight-acre tract still bear witness to the British presence.

Down the hill from the cemetery is a deep depression called Cornwallis Hole. The British commander is said to have buried his payroll here in order to prevent its capture by American pursuers. As legend goes, one of his own soldiers saw Cornwallis bury the gold. After the war, he returned to recover it. A less-than-tidy individual, the former soldier failed to refill the hole he dug, so it remains today.

Farther into the woods is the Old Spring. Flora MacDonald, who worshiped at Barbeque when she lived nearby, drank from this spring. So did Cornwallis and soldiers from both armies during the war.

Actually, the church was the scene of heated squabbling about the fight for independence long before Cornwallis’s arrival. Although Barbeque was organized by Scottish people, many of whom were still members when the war erupted, the church was said to be “an island of Whigs in a sea of Tories.” Church members were much at odds with each other. Even the minister was not spared the inflamed passions of parishioners.

Perhaps no story better illustrates the Scottish dilemma in wartime North Carolina than the showdown at Barbeque in late February 1776. The Reverend James Campbell was an outspoken Whig who had one son in the American army and another in the British. During a service at Barbeque on the day before the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge, he invoked the blessings of the Almighty on the efforts of the Patriot forces. Following the service, McAlpin Munn, an aged, respected Tory in the congregation, walked up to Campbell, respectfully removed his hat, and said, “Meenister, yo ha’e been a longer time frae Scotland nor me, an’ ye nae ha’ed to take the Blood Oath I ha’ae took. An’, noo, if I e’er hear ye pray ay’in as ye did this day, the bullet has been molded and the powder is in my horn to blow it through yer head.”

The graves of many church members are in the beautiful, well-kept cemetery adjacent to the brick edifice. One special marker at the edge of the cemetery is inscribed, “Sacred to the Memory of a Stranger—1766.” The story behind it explains why Barbeque has long been known as “the Church of the Open Door.” It seems that in the church’s early days, a wayfaring stranger sought refuge here one bitterly cold night but found the doors locked. His frozen, lifeless body was later discovered on the steps. Members vowed from that day that the church would never again be locked.

Inside the church, the Heritage Room holds a number of artifacts from the Revolutionary War era. Among items related to Flora MacDonald are a portrait of the Scottish heroine and fragments from her home at nearby Cameron Hill.

When you are ready to leave the church, turn right on S.R. 1285 and proceed south for 0.1 mile to N.C. 27. Located at this junction is a state historical marker for Barbeque Presbyterian Church.

Turn right on N.C. 27 and follow it south for 5.2 miles to N.C. 24 at the crossroads community of Johnsonville. Turn left and drive 3.3 miles southeast to where N.C. 24 merges with N.C. 87. En route, you’ll notice a state historical marker for the site of Mount Pleasant (also known as Cameron Hill), the home of Annabella MacDonald, Flora’s half-sister. Flora lived here during the winter of 1774–75.

Turn right onto N.C. 24/N.C. 87, drive 3.8 miles southeast to S.R. 1117, turn left, and travel 3.6 miles to S.R. 1120. Follow S.R. 1120 for approximately 6.4 miles to the bridge over Anderson Creek.

The amazing Jennie Bahn McNeill lived on this creek during the Revolution. On one occasion, a British foraging party stopped at her plantation and seized her favorite saddle horse. As Jennie rubbed the animal under the guise of bidding it a final farewell, she cunningly slipped off the bridle, slapped the horse with the reins, and screamed, “Git, you beast!” As the riderless horse sped away, Jennie Bahn remarked to her unwelcome guests, “Catch her if you can.”

Anderson Creek was also where Colonel Thomas Wade—the gallant American officer for whom Wadesboro was named—and his militiamen camped as they made their way west toward their homes in Anson County in 1781. They had been stationed in the area to protect it until Cornwallis departed from the Cape Fear. While Wade’s soldiers were here, one of their number took a coarse piece of cloth that belonged to a Scottish orphan, Marion McDowell. Although the cloth had little value, it was to have been sewn into a dress that the child planned to wear to Barbeque Presbyterian Church. This act of thievery sparked a series of bloody clashes between Whigs and Tories.

Among the Tory leaders who sought to exact revenge for the theft was John McNeill, one of Jennie Bahn’s sons. After the war, McNeill was brought to trial for the bloody reprisals he had masterminded. He was acquitted when an alibi witness lied on the stand. Following the trial, McNeill was forever known as “Cunning John.”

Continue south from the bridge for 0.3 mile to S.R. 2045 and turn right. After 0.3 mile, turn right onto S.R. 2048. Follow S.R. 2048 west for 3.4 miles to N.C. 210. Turn left, heading south. After 2.1 miles, you will reenter Cumberland County.

Approximately 8.5 miles south of the county line, N.C. 210 merges into N.C. 24 (Bragg Boulevard) within the confines of Fort Bragg Military Reservation. Continue south on N.C. 24 for 5.3 miles to U.S. 401 Bypass. Turn onto the bypass and proceed west. After 9.5 miles, you will reach the Hoke County line.

Continue west for 6 miles to U.S. 401 Business. Turn left on U.S. 401 Business and proceed 3.1 miles to N.C. 211 in downtown Raeford, the seat of Hoke County. En route, you will cross Rockfish Creek, a waterway that rises in southeastern Moore County and flows across Hoke County.

This area was the site of a regrettable incident during the war. Following Cornwallis’s march to Wilmington in late March and early April 1781, Colonel Wade deemed the immediate British threat over. Consequently, his Anson County militiamen loaded their wagons and began their march home. In the course of that journey, they set up camp at Piney Bottom, a tributary of Rockfish Creek.

The encampment came to the attention of John McNeill. Seeking retribution for the Patriots’ theft of the cloth from the little Scottish girl, he collected area Tories and ordered them to rendezvous to begin pursuing Wade. The next day, about an hour before first light, McNeill and his soldiers launched their attack. The Tories found all of Wade’s men asleep save for a lone sentinel. The guard hailed the approaching men but received no answer. He hailed them again, with the same result. He then fired, after which the Tories rushed into the sleeping camp with their guns blazing. Wakened from their slumber, the stunned, disoriented Patriots took flight. Five of their number were gunned down.

During the melee, an orphan boy who had been taken in and cared for by Colonel Wade was roused from sleep. Before he was fully awake, he lifted the flap of the wagon where he had been resting and pleaded for mercy by crying out, “Parole me! Parole me!”

Duncan Ferguson, one of McNeill’s soldiers who had long ago deserted the American army, yelled for the boy to come out. The youngster promptly jumped from the wagon and begged for his life. But when Ferguson approached him in a threatening manner, the orphan bolted. Ferguson gave chase and quickly overtook him. Using his broadsword, the Tory split the boy’s head “so that one half of it fell on one shoulder and the other half on the other shoulder,” according to one account.

Outraged by this act of needless violence, Colonel Wade assembled a large force of dragoons upon reaching his home. They soon returned to the area and launched a series of bloody reprisals for the slaughter of the orphan.

Turn left off U.S. 401 Business onto N.C. 211 and follow it south for 6.8 miles to the village of Antioch.

Here stands Antioch Presbyterian Church. Although the existing building was constructed in 1882, the church is a continuation of Raft Swamp Presbyterian Church, which was organized in 1789. Like so many of the old Presbyterian churches in the area, Antioch has a cemetery filled with the graves of Scottish settlers who participated in the civil warfare that raged in the region during the Revolution.

The church is surrounded by Raft Swamp, a wilderness area that extends from southern Hoke County into central Robeson County. During the Revolution, Raft Swamp was a center of local Tory activity. A state historical marker at Antioch calls attention to the Battle of McPhaul’s Mill, one of several fights in the swamp.

To see the battle site, turn right off N.C. 211 onto S.R. 1124 and drive west for 1.7 miles. A large stone with an engraved tablet marks the site of a mill built before the war. On September 1, 1781, Tory partisans under the command of David Fanning and “Sailor” Hector McNeill clashed here with Patriot militia under Colonel Thomas Wade.

In the days preceding the battle, Fanning set out from Wilmington for his base of operations in Chatham County. At McPhaul’s Mill, Fanning learned of the recent disaster at Elizabethtown. He also learned that Colonel Wade had crossed over to the eastern side of the Lumber River and was marching his forces to attack McNeill’s Tory forces in the Raft Swamp.

Acting quickly, Fanning directed McNeill to move down the swamp to cut off Wade’s avenue of retreat. By midday on September 1, Fanning, satisfied that he held the upper hand, launched an attack on Wade’s forces. At first fire, Fanning’s line lost eighteen horses, but once his soldiers dismounted, they attacked with a vengeance, and Wade’s soldiers took flight in utter disarray.

Had McNeill been in position as directed by Fanning, Wade’s entire force would have been captured or destroyed. As it was, Fanning gave chase for 7 miles, took 54 prisoners and 250 horses, and killed 19 of Wade’s men. For the moment, at least, the Patriot enthusiasm sparked at Elizabethtown was vanquished.

Retrace your route to N.C. 211 in Antioch. Turn right on N.C. 211 and proceed south. After 3.6 miles, you will enter Robeson County.

It is another 1.5 miles to N.C. 71 at Red Springs. A state historical marker at the intersection commemorates the former campus of Flora MacDonald College, located 1 mile east. To see the campus, follow N.C. 71/N.C. 211 (Main Street) for 0.9 mile to Third Avenue. Turn left and proceed two blocks to College Street. Nearby are the buildings of the former college named for the Scottish heroine.

Flora MacDonald College existed from 1896 until 1961, when it became part of nearby St. Andrews College. The site remains the burial ground of two children who some historians claim were born to Flora during the Revolution. Their remains were reinterred here at a special ceremony on April 29, 1937, after they were removed from graves along the Richmond County–Montgomery County line. An impressive shrine marks the burial site. Skeptics argue that the children buried here are not those of Flora MacDonald. The former college campus is now the home of Flora MacDonald Academy.

Return to the intersection of N.C. 211 and N.C. 71 in downtown Red Springs. Go south on N.C. 211 for 2.5 miles to the state historical marker for the site of the Battle of Raft Swamp.

Just four days before Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, a portion of a fourteen-hundred-man Patriot force under General Griffith Rutherford came upon Tory forces in the swampy wilderness here. Led by Colonel Thomas Owen and Major Joseph Graham, the Patriots thoroughly routed the Tories, killing sixteen and wounding fifty.

As a result of the Patriot victory at this site on October 15, 1781, the Tory stranglehold on the region was ended and the Loyalist spirit that pervaded many local homes was broken.

Retrace your route to the intersection of N.C. 211 and N.C. 71. Turn left and drive southeast on N.C. 71. It is 8.6 miles to the Scotland County line. Named for the country from which the area’s early settlers came, the county was formed in 1899.

Continue 1.1 miles southeast on N.C. 71 to U.S. 74 Bypass. Turn right and go west on the bypass for 8.1 miles to U.S. 15/U.S. 401 in Laurinburg, the seat of Scotland County. Turn south on U.S. 15/U.S. 401, proceed 0.3 mile to Lauchwood Drive, turn left, and go 0.1 mile to Dogwood Lane. Turn right on Dogwood, which leads to the campus of St. Andrews Presbyterian College.

Of special interest here is the Scottish Heritage Center. Founded in 1990, the center is dedicated to the preservation of the area’s rich Scottish history and culture. Open to the public during regular school hours, it houses a large collection of antiquarian books and artifacts related to Scottish history. It has been estimated that approximately thirty thousand Scots had settled in this part of North Carolina by the time of the Revolution.

When you are ready to leave the campus, return to the junction of U.S. 15/U.S. 401 and U.S. 74 Bypass and head west on the bypass. It is 11.1 miles to the Richmond County line. Formed in 1779, the county was named for Charles Lennox, third duke of Richmond (1735–1806), the British secretary of state who openly opposed the policies of his country toward the American colonies.

Continue west on U.S. 74 Bypass for 10.3 miles to U.S. 1 in Rockingham, the seat of Richmond County. Turn left and travel south for 5 miles to S.R. 1104. Turn right and follow S.R. 1104 for 0.7 mile to S.R. 1103 (Old Cheraw Road). You’ll notice a gated logging road on the western side of S.R. 1103. Park your car and enjoy a walk of approximately 0.3 mile to the Harrington cemetery.

Located in this old burial ground overlooking the Pee Dee River is the grave of Brigadier General Henry William Harrington (1747–1809). A marble slab engraved with Harrington’s achievements marks the site of his interment.

Born in London, Harrington was living in South Carolina when the Revolution began. He was active for the American cause there until he moved to Richmond County in 1779. In North Carolina, he was promptly appointed a colonel of the militia.

After serving in the defense of Charleston during the first half of 1780, he came home to take a seat in the North Carolina General Assembly. In June 1780, the thirty-three-year-old Harrington was promoted to the temporary rank of brigadier general. Headquartered near Fayetteville, he was charged with the procurement and protection of supplies.

Harrington was once described as “a very intelligent gentleman, who is well acquainted with this part of the country and with particular circumstances relating to the enemy and to us.” Nevertheless, he was replaced as brigadier general by William Lee Davidson in September 1780. (For more information about Davidson, see The Hornet’s Nest Tour, pages 172–73.) Although bitterly disappointed, Harrington remarked upon tendering his commission, “So this my country is but faithfully served, it is equal to me whether it be by me or by another.” Horatio Gates implored him to remain in military service, but to no avail. Harrington returned home to Richmond County.

During his wartime absence, Harrington had suffered tremendous personal loss. His wife and children had been forced to flee the plantation on two occasions, first to South Carolina and then to Maryland. His baby daughter had died during the latter flight. And Tory raiders had destroyed his personal papers and his extensive library.

After the war, Harrington became the foremost citizen of Richmond County. In addition to his service in the legislature, he served on many local boards and commissions. In honor of his great success as a planter, two important titles were bestowed upon him: “the First Farmer in the State” and “the Father of Export Cotton in North Carolina.”

Despite the losses he sustained at the hands of Tories, Harrington showed compassion in the war’s aftermath. When he learned that the daughters of Captain John Leggett, the Tory leader who had plundered his plantation, were living in poverty, he conveyed to them the title to their former lands. That property had been awarded to Harrington as compensation for the outrages committed by their father.

When he died at the age of sixty-two, an obituary in a Raleigh newspaper noted about Harrington that “the nicest sense of honor and strictest principles of justice marked every transaction of his life.”

The tour ends here, at the resting place of a great Patriot.