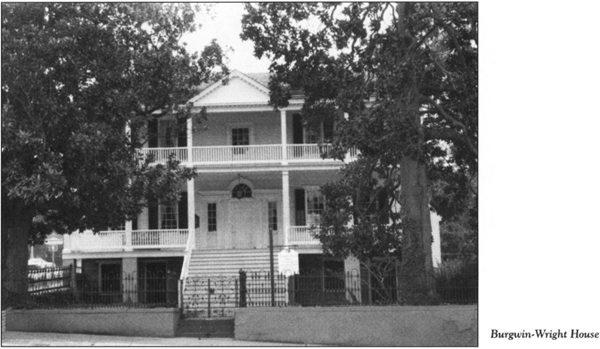

This tour begins near Dudley in southern Wayne County and makes its way through Sampson, Duplin, and New Hanover Counties before ending at Southport in Brunswick County. Among the high, lights are the story of Polly Slocumb, the story of Zebulon Hollingsworth, Liberty Hall, the Battle of Rockfish Creek, historic Wilmington, Orton Plantation, Brunswick Town State Historic Site, and historic Southport.

Total mileage:

approximately 134 miles.

This tour makes its way through five eastern North Carolina counties that lie along the banks of the mighty Cape Fear River and its tributaries. One of the great rivers of America, it winds its way for 320 miles from the Chatham County-Lee County line in central North Carolina to Cape Fear in Brunswick County.

Because the Cape Fear is the only river in the state that offers a direct deepwater outlet to the Atlantic, the lands along its banks attracted some of the colony’s first settlers. Soon after it was chartered in 1739, Wilmington, located 30 miles upriver from the Cape Fear’s mouth, became the most important port in North Carolina, a status it enjoyed during the Revolutionary War and that it retains to this day.

Downriver from Wilmington, the ancient port of Brunswick Town served for a time as the colonial capital. As a result, many of North Carolina’s leading statesmen were attracted to the area. A number of these men were early leaders of the Revolution. The Cape Fear was thus the stage on which some of the most important acts in the struggle for independence were played out.

At Brunswick Town eight years before the much-heralded Boston Tea Party, Cape Fear Patriots offered the first armed, open resistance to British rule in all of colonial America. And a year before the Declaration of Independence was signed, North Carolina’s last Royal governor, Josiah Martin, boarded a British warship at the mouth of the Cape Fear and fled North Carolina in the wake of mounting tensions.

The tour begins at the junction of U.S. 117 Bypass and U.S. 117 Business in southern Wayne County. Born of the American Revolution, the county was named for Major General “Mad Anthony” Wayne, the energetic officer who captured the heart of the emerging American nation with his brilliant victory at Stony Point, New York, in July 1779.

Follow U.S. 117 Business south for 4.9 miles to the granite marker erected by the D.A.R. on the campus of Southern Wayne High School. It honors the site of the home and former burial site of Ezekial Slocumb and his wife, Polly, whose remains were later interred at Moores Creek National Military Park.

Polly Slocumb had an interesting encounter with the British army at the two-story home that once stood here, an incident that illustrates the defiant spirit of the people of the Cape Fear.

In late April 1781, as the Redcoats marched north from Wilmington toward Virginia, Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton, accompanied by several aides and a squadron of twenty cavalry troopers, rode up to the Slocumb house. The son of a prominent Liverpool family and a graduate of Oxford University, Tarleton had the charm and grace of a gentleman despite his cocky attitude and short temper. When he saw Polly, he removed his cap, bowed his horse’s neck, and addressed her with great courtesy: “Have I the pleasure of seeing the mistress of this house and plantation?”

“It belongs to my husband,” Polly responded curtly.

“Is he at home?”

“He is not.”

“Is he a rebel?” Tarleton asked.

Without trepidation, Polly replied, “No, sir! He is in the army of his country and fighting against our invaders, therefore not a rebel.”

Maintaining his composure, the British officer quipped, “I fear we differ in opinion, madame. A friend to his country will be the friend of the king, our master.”

Polly was quick with a comeback: “Slaves only acknowledge a master in this country.”

Tarleton had heard enough. Still suffering great pain from the slash wound he had taken from Colonel William Washington at Cowpens and from the two fingers he had lost at Guilford Courthouse, the cavalry chieftain announced that he would occupy the plantation house as his headquarters.

By the time the lady of the house prepared a meal for her unwelcome guest, Tarleton’s temper had subsided. Again the gentleman, he made a polite request: “May I be allowed, without offense, madame, to inquire if any part of Washington’s army are in this neighborhood?”

In the manner of the patriotic ladies of Halifax, this heroine of the Cape Fear could not forgo the opportunity to vex Tarleton: “I presume that it is known to you, that the Marquis [de Lafayette] and [General Nathanael] Greene are in this state. You would of course not be surprised at a call from [Lieutenant Colonel Henry] Lee, or your friend Colonel [William] Washington, who, although a perfect gentleman, it is said, shook your hand very rudely, when you last met.”

Tarleton’s response is unknown, but it is said that he sped away soon thereafter, never to return to the Slocumb homestead. The exploits of the legendary Slocumbs are further chronicled in The Scottish Dilemma Tour.

From the Slocumb marker, continue south on U.S. 117 Business for 3.1 miles to N.C. 55. Turn right on N.C. 55 and drive 3 miles west to S.R. 1117, better known as Thunder Swamp Road. Cornwallis’s army camped in this area while Tarleton made his visit to the Slocumb plantation. Just east of here, the Northeast Cape Fear River begins its run south to Wilmington, where it enters the Cape Fear.

Continue west on N.C. 55 for 4.2 miles to S.R. 1111 and turn left. It is 0.8 mile south to the Sampson County line. Carved from nearby Duplin County in 1784, the county takes its name from John Sampson, a local planter and colonial official who died the year the county was formed.

From the county line, continue south as the road becomes S.R. 1725. After 7.9 miles, S.R. 1725 intersects N.C. 403 at Hargrove Crossroads. Proceed across the intersection and follow S.R. 1740 for 3.6 miles to S.R. 1904. Turn left on S.R. 1904 and head north for 1.3 miles to S.R. 1909. Turn right and drive 4.2 miles to “The Sycamores,” a two-story frame structure on the right. This home was built around 1780 by Thomas Hicks. An officer of the colonial militia before the war, Captain Hicks served as a delegate to the First and Third Provincial Congresses at New Bern and Hillsborough. You’ll notice that several of the sycamores from which the house took its name are still growing nearby.

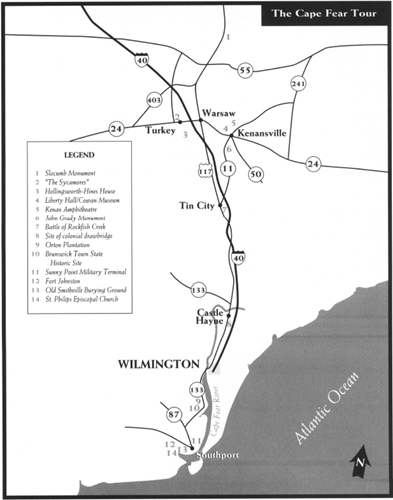

Follow S.R. 1909 for 0.4 mile to N.C. 24 in the village of Turkey. Proceed across the intersection and drive south on S.R. 1004 (Needmore Road) for 3.6 miles to S.R. 1926 (New Hope Church Road). Turn left and head east on S.R. 1926 for 1 mile to the Hines-Hollingsworth House, located on the right.

Built around 1750, this handsome, two-story frame dwelling stands on a farm that has remained in the Hollingsworth family for nine generations. But had it not been for fate, the family would have left the area for Tennessee after the Revolutionary War.

Buried in a grave in a field across the road is Zebulon Hollingsworth, a Revolutionary War soldier who once lived in the house. Hollingsworth served in the North Carolina Continental Line throughout the war and found himself in Massachusetts when the fighting ended. He began the long, arduous trip home on foot. Dressed in his tattered uniform, he endured the cold of winter and the blazing sun of summer; he swam rivers and creeks; and he braved swamps and wilderness areas alone. During the journey, which took more than a year, Hollingsworth often had to stop to find work in order to buy food.

When he finally arrived at the family farm one night, he called at the house, only to find it abandoned. Nearby, his family members were holding a “goodbye dance,” for, on the morrow, they planned to start out with their loaded wagons for the Tennessee wilderness. The family had lost all hope for Zebulon months before, but when he appeared from the darkness on the very night before the departure, they tearfully welcomed the young hero home, unpacked their belongings, and resumed their residence here.

Today, the house, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and the farm are owned by James L. Hines and his wife, Esther. James L. Hines is a direct descendant of the Hollingsworth family.

Retrace your route to the intersection with N.C. 24 in Turkey and turn right. It is 1.7 miles to the Duplin County line. Formed in 1750, Duplin County was named in honor of a British colonial official, Thomas Hay, Lord Duplin (1710–87).

From the county line, continue east on N.C. 24 for 3.7 miles to where it merges with N.C. 50 in Warsaw. Follow N.C. 24/N.C. 50 for 6.5 miles to the Liberty Hall Restoration in the town of Kenansville, the seat of Duplin County.

Here stands the jewel of Duplin County. Open to the public since 1968, the Liberty Hall Restoration features the exquisite two-story, eleven-room Greek Revival house constructed by Thomas Kenan (1771–1843) in the first decade of the nineteenth century. The complex takes its name from the family plantation near Turkey.

On the grounds is the grave of James Kenan (1740–1810), which was moved here from the original Liberty Hall site. James Kenan was one of Duplin’s greatest Revolutionary War heroes. As the county sheriff in 1765, he was a leader in the organized protest against the Stamp Act in Wilmington. Elected a militia colonel by the Third Provincial Congress in September 1775, he orchestrated the defense of the Duplin County area throughout the war. He was conspicuous in the campaign that led to the American victory at the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge.

Just weeks after the setback at the hands of Major James Craig at nearby Rockfish Creek on August 2, 1781, Kenan mustered four hundred militiamen and moved on the Tories responsible for the recent reign of terror in the Cape Fear area. According to one of Kenan’s men, “[We] marched straight into the neighborhood where the Tories were embodied, surprised them; they fled, our men pursued them, cut many of them to pieces, took several and put them instantly to death. The action struck … terror on the Tories in our county.”

Adjacent to the Liberty Hall Restoration is the Duplin County-Cowan Museum. Displayed in the facility are artifacts from the colonial and Revolutionary War periods. Restored buildings from the county’s historic past are located on the museum grounds.

Continue on N.C. 24/N.C. 50 to N.C. 11. Turn left on N.C. 11 and proceed 0.4 mile northeast to the Kenan Amphitheatre.

One of the finest amphitheaters in the state, this facility is the venue for an outdoor drama that chronicles the story of the Revolution in North Carolina. Written by playwright Randolph Umberger, The Liberty Cart: A Duplin Story is a dramatization of events that shaped the area from 1755 to 1865. Among the Revolutionary War characters and events presented in the play are Colonel James Kenan, the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge, and the Battle of Rockfish Creek.

Return to the intersection with N.C.24/N.C. 50 in Kenansville, then continue south on N.C. 11 for 1.4 miles to James Sprunt Community College. The John Grady Monument is located at the flagpole on the front lawn of the campus. Dedicated in October 1976, it is a memorial to a brave Patriot killed at the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge. His story of heroism is recounted later in this tour.

Continue south on N.C. 11 for 16.1 miles to the battlefield park at Rock-fish Creek. Turn left at the sign for the water treatment plant. The park is located on the left side of the road within sight of the highway.

Other than a state historical marker and a chipped marble monument, there is nothing here to remind visitors of the spirited battle that took place on the banks of this tributary of the Northeast Cape Fear on August 2, 1781.

Five years after the Declaration of Independence, Cornwallis and his army were long gone from North Carolina, but Major James Craig maintained a base of operations in Wilmington. Strong bands of Loyalist soldiers continued to menace Patriots in the area.

On the day of the battle, Craig and 600 Loyalists appeared on the southern side of the creek in their quest to plunder the counties of eastern North Carolina. To oppose the crossing, Colonel James Kenan placed 150 militiamen behind breastworks lining the creek banks. He was reinforced by 180 men commanded by Richard Caswell.

After an initial attack by the Patriots, Major Craig ordered a counterattack. Craig had one great advantage: artillery. According to Kenan, after a few rounds from the big guns, his men “broak [sic] and it was out of my power and all my Officers to rally them.” The result was a rout of the American militia. Once across the creek, Craig marched his army north to New Bern, causing damage all along the way.

From Rockfish Creek, follow N.C. 11 south to U.S. 117. Drive south on U.S. 117 for 20.1 miles to N.C. 133 at the town of Castle Hayne. Continue south for 1.7 miles to the state historical marker near the bridge over the Northeast Cape Fear at the Pender County-New Hanover line. This was the site of one of the few drawbridges in the American colonies. Constructed in 1768, the structure was destroyed by British troops during their occupation of the Wilmington area in 1781.

Formed in 1729 from Craven County, New Hanover County was named in honor of the British Royal family, which was from the house of Hanover. Despite its regal name, the county was anything but loyal to the Crown during the American Revolution. As respected North Carolina historian John H. Wheeler noted, “There is no portion of North Carolina more early and more sincerely devoted to liberty than New Hanover.”

One mile south of the Northeast Cape Fear River, U.S. 117 intersects N.C. 132. Take N.C. 132, the left fork, and continue south for 5.3 miles to Market Street (U.S. 17/U.S. 74). Turn right on Market Street and drive west toward downtown Wilmington.

Wilmington National Cemetery, located on the right side of Market Street at its intersection with Twentieth Street, was established in 1867 as a permanent burial ground for Union soldiers who had been killed during the Cape Fear campaign two years earlier. However, there is one grave here that is related to Revolutionary War history. Set amid the long, straight rows of white, government-issue gravestones is the marker for renowned novelist Inglis Fletcher.

Fletcher (1879–1969) penned a widely read, twelve-volume series of historical novels that dramatized the events in the colonial and Revolutionary War periods in North Carolina. Among her most popular titles were Raleigh’s Eden (1940), Lusty Wind for Carolina (1944), Toil of the Brave (1946), Roanoke Hundred (1948), Queen’s Gift (1952), and The Scotswoman (1955). Her grave, located northwest of the flag circle, lies next to that of her husband, a veteran of the Spanish-American War.

Continue on Market Street to the Cape Fear Museum, located at 814 Market. Home to the museum since 1970, the modified Gothic Revival building was constructed as an armory in the mid-1930s. The growing popularity of the museum has led to numerous modifications of and additions to the structure. Inside, a multilevel exhibition area chronicles the long history of Wilmington and the surrounding area.

On the eve of the American Revolution, Wilmington was the leading city in North Carolina. Its fine harbor, protected from the fierce storms of the Atlantic, was jammed with ships from distant ports. Most came for cargoes of tar, pitch, and turpentine, which were in high demand in Europe. North Carolina was the world leader in the production of naval stores from 1720 to 1870, and Wilmington was the primary port through which they were shipped.

Because of its importance as a port and its location on the King’s Highway (see The Scottish Dilemma Tour, page 110), the city became a center for the exchange of political opinions in the years leading up to the Revolution. Wilmington attracted men of great stature, many of them ardent Patriots in the struggle for independence.

Continue west on Market Street. In the middle of Market just east of the intersection with Fourth Street stands the Harnett Obelisk, a monument to one of the most remarkable and talented, yet unsung, heroes of the American Revolution.

Cornelius Harnett (1723–81), a man known as “the Pride of the Cape Fear,” was one of the earliest and most ardent leaders in the quest for independence. Born in Chowan County, he spent his formative years at Brunswick Town on the lower Cape Fear River, where he was exposed to the revolutionary ideas being bandied about town.

As a young adult, Harnett moved upriver to Wilmington, where he became active in the political life of the city and colony. An outspoken opponent of British taxation, Harnett provided the leadership that made enforcement of the Stamp Act virtually impossible at Wilmington and Brunswick Town. In February 1766, he served as one of the ringleaders of an armed showdown against Royal authority at Brunswick Town. As a result, Harnett became an overnight hero throughout North Carolina.

In 1770, at a time when most Americans were reluctant to take a public stand against British authority, Harnett openly announced that he was “ready to stand or fall with the other colonies in support of American liberty” and that he “would not tamely submit to the yoke of oppression.” These bold statements were made more than four years before the first shots of the war were fired.

Following a meeting with Harnett in March 1773, noted Boston Patriot Josiah Quincey, Jr., spread the fame of the Cape Fear revolutionary throughout the North, calling him “the Samuel Adams of North Carolina.”

On May 8, 1775, a horse bearing a special courier galloped into Wilmington with an important dispatch. When it was placed in Harnett’s hands, he learned the exciting news that Americans had done battle with British forces in Lexington, Massachusetts. He directed the rider to Brunswick County with a message for fellow Patriots there. Suddenly, the pace of Harnett’s quest for independence was quickening.

Fearful of Harnett and other Patriot leaders in the colony, Royal Governor Josiah Martin fled North Carolina in the summer of 1775. Meanwhile, at Hillsborough, the Third Provincial Congress established a thirteen-man Provincial Council. Unanimously selected as president of the council was Cornelius Harnett. In that capacity, Harnett endured great personal risk to serve as chief executive of the colony.

At the Fourth Provincial Congress, held at Halifax in April 1776, Harnett chaired the committee appointed to draft a resolution “to take into consideration the usurpations and violences attempted by the King and Parliament of Britain against America.” On April 12, Harnett, the author of the committee report, stepped to the podium and read the Halifax Resolves.

Around this time, Sir Henry Clinton arrived in southeastern North Carolina with a sizable British force. He soon abandoned his plans to invade the colony. But before leaving North Carolina waters, he issued a proclamation from his warship: All subjects who would lay down their arms and pledge allegiance to the Crown would be pardoned by the king, “excepting only from the benefits of such pardon Cornelius Harnett and Robert Howe.”

Ten months after he gave the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence in North Carolina, the fearless Harnett was elected—against his wishes—to replace William Hooper in the Continental Congress. During his three terms, the Cape Fear statesman proved one of that body’s most prominent and effective members.

Crippled by gout and hardly able to hold a pen, Harnett came home to Wilmington in February 1780. Less than a year later, when Major James Craig began the British occupation of Wilmington, he made it his first order of business to track down the man whose name appeared at the top of the England’s “most wanted list.”

Having received advance notice of Craig’s approach, Harnett fled Wilmington and sought sanctuary with his old friend James Spicer at a plantation in Onslow County 30 miles north of Wilmington. Craig’s men quickly closed in on their prey. They found Harnett, pulled him from his bed, and drove him on foot down the road toward Wilmington until fatigue and illness overcame him. When the crippled man fell on his face in the sandy road, his captors grabbed him up, bound his hands and feet, and strapped him across the back of a horse.

Craig was delighted to see his trophy delivered to him. With total lack of regard for his prisoner’s frail condition, the British officer ordered Harnett confined in a roofless blockhouse called “the Bullpen.” The harsh winter weather soon took its toll, and Harnett grew gravely ill. Only after Whigs and Tories alike implored Craig was Harnett released. But personal freedom came too late. Surrounded by family and friends, Harnett died on April 28, 1781, before his dream of a free and independent America had fully become reality.

Near the thirty-foot obelisk is the cemetery of St. James Episcopal Church, located at the southeastern corner of Market and Fourth Streets. It contains the marked graves of Harnett and several other Revolutionary War figures, among them John “Jack” Walker (1741–1813), an officer who served under George Washington at Germantown, Brandywine, and Valley Forge. As a colonel, Walker acted as aide-de-camp on Washington’s staff. Also buried in the cemetery is Thomas Hooper (1746–1821). The younger brother of a signer of the Declaration of Independence, Hooper was a suspected Loyalist during the Revolution.

Continue on Market Street across Third and park nearby to enjoy a short walking tour of downtown Wilmington.

Peter Du Bois, a visitor to Wilmington in 1757, praised the city in this manner: “The Regularity of the Streets are equal to those of Philadelphia and Buildings in General are very good. Many of Brick, two or three stories high with double piazzas which make a good appearance.” The town’s European-style street grid, laid out in 1739 and modified four years later, has survived virtually intact. Nevertheless, the downtown streets boast few buildings from the Revolutionary War era. Although Wilmington was spared armed conflict, several devastating fires in the nineteenth century destroyed many of the town’s eighteenth-century structures.

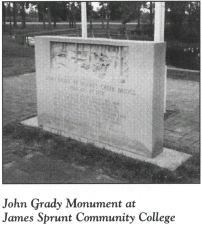

One of the few pre-Revolutionary War houses still standing and open to the public is the Burgwin-Wright House, located at 224 Market Street, just across Third Street from St. James Episcopal Church. John Burgwin, colonial treasurer under Royal Governor Arthur Dobbs, constructed the magnificent, two-story Georgian mansion in 1770. Its foundation consists of the massive stone walls of a former jail located at the site. Because of his allegiance to the Crown, Burgwin fled Wilmington at the outbreak of war and remained in England until the cessation of hostilities.

For much of the war, Wilmington was free of British troops. But in late January 1781, thirty-three-year-old James Craig sailed up the Cape Fear to take possession of the defenseless city. Major Craig, a soldier since the age of fifteen, immediately commandeered Burgwin’s house as his headquarters because it was “the most considerable house in town.”

When the battered, demoralized army of Lord Cornwallis limped into Wilmington on April 12, 1781, after its costly “victory” over Nathanael Greene’s Americans at Guilford Courthouse, the British commander made his headquarters at Burgwin’s House. Consequently, it is sometimes known as “the Cornwallis House.”

Cornwallis rested his weary army for almost two weeks in Wilmington while he took on supplies for his march north to Yorktown and destiny. The floorboards inside the Burgwin-Wright House display marks made by British muskets during Cornwallis’s stay.

More than two hundred years after the Redcoats lodged here, another intriguing reminder of the British presence in the house came to light. One particular British soldier under Cornwallis had fallen in love with a beautiful young woman in South Carolina. While he was quartered at Burgwin’s house, the soldier etched his sweetheart’s name in a windowpane with his diamond ring.

After the war, the soldier returned to South Carolina, married his girlfriend, and took her to live in England. Subsequently, the couple emigrated to the United States and settled in New York. On a visit to Wilmington in 1836, their son was the guest of Dr. Thomas H. Wright, who had inherited the house. In fact, the visitor slept in the same bedroom occupied by his father during the Revolutionary War. He noticed the name etched in the windowpane and immediately recognized it to be his mother’s.

John W. Barrow, the grandson of the British officer, came to Wilmington in search of the windowpane forty years later, having been told of it by his father. When he called at the Burgwin-Wright House, the owner informed him that the home had been remodeled. They descended into the cellar, where prisoners had been held during the Revolutionary War. Among the remnants stored there after the renovations was the special pane.

From the Burgwin-Wright House, walk west on Third Street for one block to Princess Street. Located at this intersection is a state historical marker on the site of William Hooper’s town house. (For information on Hooper, one of North Carolina’s three signers of the Declaration of Independence and one of the foremost Patriots of the American Revolution, see The Regulator Tour, pages 373–423.)

Return to the intersection of Third and Market. Walk south on Market Street past the Burgwin-Wright House in the direction of the waterfront.

Located under the street is Jacob’s Run, the most famous of the labyrinthine brick tunnels constructed in Wilmington’s distant past. A bricked-over section of the cellar wall of the Burgwin-Wright House was once the opening to a tunnel that runs with the flowing waters of an underground stream to the Cape Fear. Although the original purpose of this tunnel has never been explained, it has been speculated that American prisoners used it to escape from the British jail in the basement of the Burgwin-Wright House.

Continue south on Market Street. On November 17, 1781, famed cavalry officer Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, the father of Robert E. Lee, galloped down this street with the glorious news of Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown.

A marble tablet at the intersection of Market and Front Streets marks the site of the town’s courthouse during colonial days. On November 16, 1765, Dr. William Houston, Wilmington’s unfortunate stamp master, was escorted here by a hostile crowd. He executed his resignation to the delight of local citizens who had assembled to protest the Stamp Act.

It was also at this courthouse that the members of the local Committee of Safety met on June 19, 1775, and entered into a pledge that contained this bold language: “We do unite ourselves under every tie of religion and honor and associate as a band in her defense against every foe; hereby solemnly engaging that whenever our continental or provincial councils shall decree it necessary we will go forth and be ready to sacrifice our lives and fortunes to secure her freedom and safety.”

Continue south on Market Street. Near the junction with Water Street is a granite marker at the site of the home of Royal Governor William Tryon, who maintained a residence here until Tryon Palace was completed.

It was at this residence that the angry mob confronted Dr. Houston, who remembered the showdown this way: “The inhabitants immediately assembled about me and demanded a categorical answer whether I intended to put the Act relating [to] the Stamps in force. The town bell was rung, drums beating, colors flying and a great concourse of people were gathered together.”

Walk across Water Street to Riverfront Park, which affords a spectacular view of the Cape Fear. Although the wharves and docks of the Revolutionary War era vanished long ago, the municipal park is located at the site where tall-masted ships once tied up.

If you look north across the river, you’ll see a spit of land at the forks of the Cape Fear. Formerly known as Mallette Point in honor of Colonel Peter Mallette, a Revolutionary War hero, it is now called Point Peter. During the war, the area was nothing more than a cypress swamp. But when Cornwallis called on Wilmington in the spring of 1781, it became a makeshift fort for a small band of Patriots incensed by the arrival of the Redcoats.

The fort was located in the most unlikely of places—the base of a hollow cypress so large that it could have housed a small family. One of the partisans, a skilled gunsmith, crafted a rifle long enough to send a ball from the big tree to the Wilmington waterfront. Soon, unsuspecting British soldiers began dropping like flies about the docks. The small Patriot band continued its reign of terror for more than a week, until a Tory neighbor alerted the Redcoats. When they came ashore on the point, British soldiers found the abandoned cypress outpost.

Walk east along the waterfront to the junction of Water and Dock Streets. Turn left and go one block north to the intersection of Dock and Front.

This is the former site of the Quince House, where President George Washington lodged on Sunday and Monday, April 24 and 25, 1791. While being feted at Dorsey’s Tavern, Washington commented about the many swamps he had observed en route to Wilmington and about his concern over the quality of local drinking water. When the president asked the tavern owner about the water, Lawrence A. Dorsey is said to have replied that he could not speak on the subject because he never drank it.

Continue north on Dock Street for two blocks to Third Street, where you’ll see a state historical marker commemorating Washington’s visit. Turn left on Third and go one block west to Market to return to your vehicle.

Drive east on Third through the downtown area to the intersection with U.S. 17/U.S. 74/U.S. 76. Turn right and proceed west over the river via the magnificent Cape Fear Memorial Bridge. Once across the bridge, you will enter Brunswick County. Created in 1764 from New Hanover County, it was named for the old port town by the same name just downriver.

Continue west approximately 3 miles from the Cape Fear Memorial Bridge to the intersection with N.C. 133 at Belville. Turn onto N.C. 133 and proceed south. The route roughly parallels the Cape Fear River as the mighty waterway makes its way to its mouth at Southport. Just south of the U.S. 17/U.S. 74/U.S. 76 overpass, you’ll encounter a long row of state historical markers, including a half-dozen related to the Revolutionary War; the sites described on the markers are included in this tour.

It is 13.2 miles on N.C. 133 to S.R. 1529, where you’ll notice historical markers for three important sites of the Revolutionary War era: Orton, Brunswick Town, and St. Philips Church. To see the first of these sites, turn left onto S.R. 1529 and proceed to the entrance of Orton Plantation, marked by massive stone pillars surmounted by eagles with outspread wings.

Once inside the gate, you’ll be treated to views of the only surviving colonial mansion on the Cape Fear and its surrounding gardens, considered some of the most beautiful in America. Mansion and gardens are the focus of an estate that once contained ten thousand acres.

Orton was the dream of Roger Moore, a renowned Indian fighter who received an enormous land grant on the banks of the Cape Fear in 1725. Erected by Moore in 1730 and subsequently modified, the mansion is considered one of the finest examples of Greek Revival architecture in the United States. With the exception of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, the mansion at Orton is perhaps the most-photographed structure in the state. The house is private, but the adjacent gardens are open to the public for an admission fee.

When “King Roger” died in 1750, the plantation came into the possession of his sons, George and William. George (1715–78), the father of twenty-eight children, became caught up in the revolutionary fervor that took hold of the Cape Fear in the mid-1760s. He was a participant in the armed resistance against the Stamp Act at Brunswick Town in 1766. Fifteen years later, the British army retaliated when a landing party of Cornwallis’s soldiers looted Orton.

Return to the entrance of Orton on S.R. 1529. Turn left and drive 0.8 mile to S.R. 1533. Turn left and proceed east on S.R. 1533 for 1.1 miles to the ruins of Brunswick Town on the Cape Fear River.

At this state historic site, visitors have an opportunity to take a leisurely stroll along the tree-shaded lanes of a former port town where one of the first events—if not the first event—of the American Revolution took place. Tours of the site begin at the visitor center, located adjacent to the parking lot. Inside the center, interpretive displays and artifacts tell the story of the rise and fall of Brunswick Town.

Established in 1726 by the Moore family of nearby Orton, the town was named in honor of King George I of England, the German-born monarch who was duke of Brunswick. The father of Revolutionary War hero Cornelius Harnett purchased the first two lots in the town and moved his family here from Edenton. The town’s prosperity appeared to be insured in 1731, when it was named one of the five official ports of entry of the colony.

Brunswick was the seat of New Hanover County from 1729 to 1741, when Wilmington usurped the honor. Upon the formation of Brunswick County in 1764, Brunswick reclaimed its honor as a county seat. Six years earlier, the town had already begun to take on renewed prominence when Royal Governor Arthur Dobbs established his residence at Russellborough, a fifty-five-acre estate on the northern edge of town.

Dobbs (1689–1765), a former member of the Irish Parliament and a promoter of the search for the Northwest Passage, served as Royal governor of North Carolina from 1754 to 1765. Drawn to Brunswick because of its moderate climate, he established the town as the seat of colonial government. From 1758 to 1770, Russellborough was the home of Dobbs and his successor, William Tryon. During the two governors’ residency, the general assembly met here.

Governor Tryon was in Brunswick Town on February 19, 1766, when he became embroiled in an armed showdown over Royal authority in the colony. Dissatisfied with Tryon’s position on the Stamp Act, a group called the Sons of Liberty—which had several months earlier pledged to prevent enforcement of the legislation—marched from Wilmington to Brunswick Town. Led by Cornelius Harnett, John Ashe, and other Cape Fear Patriots, the angry men surrounded the governor’s residence. There, Harnett and George Moore informed the governor that the Patriots were willing to take whatever action was necessary to make the Stamp Act unenforceable.

For a time, Tryon was held under virtual house arrest, as 150 Patriots encircled the house. Several days later, bloodshed was averted when Harnett escorted customs officials and other agents of the Crown into the streets of Brunswick, where, in front of the armed Patriots, they took an oath to refrain from issuing any stamped papers in North Carolina. Soon thereafter, the Patriots returned to their homes. They had taken a firm stand against British colonial rule and won.

In reporting the event, the Virginia Gazette, the foremost journal in Virginia at the time, urged its readers to emulate the example set at Brunswick Town: “It is well worthy of observation that few instances can be produced of such a number of men being together so long, and behaving so well, not the least noise or disturbance, nor nay person seen disguised with liquor, during the whole of their stay in Brunswick, neither was there any injury to any person, but the whole affair conducted with the decency and spirit, worth the imitation of all the Sons of Liberty throughout the Continent.”

At the time of the showdown, no one could foresee the course the colonies would take toward independence. Since then, the events at Brunswick have been neglected by many historians. But George Davis, the celebrated North Carolina statesman and historian of the nineteenth century, eloquently put them into perspective: “This was more than ten years before the Declaration of Independence and more than nine before the Battle of Lexington, and nearly eight before the Boston Tea Party. The destruction of the tea was done at night by men in disguise. And history blazoned it, and New England boasts of it, and the fame of it is world wide. But this other act, more gallant and more daring done in open day by well-known men, with arms in their hands, and under the King’s flag—who remembers it, or who tells of it?”

When Governor Tryon left for his new residence in New Bern in 1770, Brunswick—which had never boasted a population of more than four hundred—began a decline from which it would never recover. In one of the ironies of American history, the town where the sparks of the Revolution first glowed was torched by British attackers in 1776.

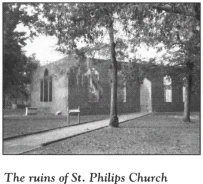

A free brochure at the visitor center provides a detailed tour route of the town ruins. Located near the center is the most prominent reminder of colonial Brunswick Town—St. Philips Church.

Authorized by the general assembly in 1759, the Anglican church was completed by Governor Tryon in 1768. Only its massive, thirty-three-inch-thick brick walls stand today. Within these roofless walls are a couple of graves of importance to the Revolutionary War. Royal Governor Dobbs and Alfred Moore are buried here, as is the infant son of Royal Governor Tryon.

Alfred Moore (1755–1810), was the son of Maurice Moore, Jr., a noted jurist in the early days of the Revolution. As a young officer fighting for the American cause, Alfred saw his first action under the command of his uncle, James Moore, at the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge. Near the close of the war, he directed the Cape Fear militia’s reprisals against Major Craig’s forces at Wilmington.

Like his father, Moore became a distinguished attorney and jurist. Upon the death of James Iredell in 1799, President John Adams appointed Moore to fill the vacancy on the Supreme Court. Due to ill health, Moore retired five years later. He stands as the last North Carolinian to serve on the nation’s highest court.

From the church, visitors can make their way down old Second Street, which veers sharply east toward the river. This quiet, peaceful route passes the ballast-stone foundations of homes and buildings where some of the most important men in colonial North Carolina lived and visited. There are no tangible reminders of the hustle and bustle of the colonial period and the excitement of the early days of the struggle for independence. But legend has it that the specter of the Revolution lingers here. Not surprisingly, a place that became a ghost town two centuries ago counts ghosts as its current residents.

In the days leading up to the Revolution, two Scotsmen fled to America from their native land after a fight against British authorities. They were taken into custody near Wilmington by the infamous Tory David Fanning. (For more information on Fanning, see The Regulator Tour, pages 373–423.) Charged with treason, the two prisoners were held in chains deep in the bowels of a prison ship anchored off Brunswick Town.

Following several unsuccessful escape attempts, the unfortunate men were brought ashore at Brunswick Town. Tried and convicted by a kangaroo court, they were sentenced to death by Fanning himself. They were subsequently killed by a firing squad, but local tradition holds that on stormy nights, they can still be seen in a phantom boat on the river searching for rescuers.

When you are ready to leave Brunswick Town, retrace your route to Orton Plantation and turn left on S.R. 1530. After 0.3 mile, turn left onto N.C. 133, heading south toward Southport, 11 miles distant. En route, you’ll pass a sign marking the entrance to the massive Military Ocean Terminal at Sunny Point. This terminal—the nation’s largest shipper of weapons, tanks, explosives, and military equipment—covers much of the historic Brunswick riverfront, including one Revolutionary War site. Howes Point, located 1 mile south of Brunswick Town within the confines of Sunny Point, was the site of Job Howe’s plantation. His famous Revolutionary War son, Robert Howe, was born here in 1732. (For information on Robert Howe, see The Scottish Dilemma Tour, pages 118–19.) British troops plundered Howes Point on May 12, 1776.

Near the entrance to Sunny Point, N.C. 133 merges into N.C. 87. Continue south on N.C. 87 for 3.7 miles to Southport, where the road becomes Howe Street. Named in honor of Robert Howe, the main thoroughfare into the historic port city is one of a number of local streets that bear the names of Revolutionary War notables. For example, Moore Street honors James Moore, one of the heroes of the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge, and Caswell Street pays homage to Richard Caswell.

Follow Howe Street to its terminus at the picturesque Waterfront Park. Leave your car in the parking lot to enjoy a brief stroll. In the distance looms the mouth of the Cape Fear. Through this inlet, vessels have made their way into the river from the Atlantic for more than four hundred years.

Walk east to the nearby City Pier. Located along the waterfront between the park’s picnic area and the pier is an almost unnoticeable wall of crumbling rock now covered with masonry and debris. This wall is the only remnant of the original fortifications of Fort Johnston.

In 1730, Fort Johnston became the first of six military installations authorized by the colonial assembly. Construction did not begin until 1745, and then the project took ten years to complete. Named in honor of Governor Gabriel Johnston (1699–1752), the fort was the last place of refuge in mainland North Carolina for Josiah Martin, the last Royal governor of the colony. A nearby state historical marker commemorates Martin’s flight to this spot.

After sending his family north to the relative safety of New York, Martin hastened south from New Bern in the late spring of 1775. Arriving at Fort Johnston on June 2, he holed up temporarily at the installation, which he described as “a contemptible thing, fit neither for a place of arms nor an asylum for the friends of government.”

Royal government in North Carolina was now a thing of the past. Nevertheless, Martin formulated plans at the Cape Fear outpost to recover his authority and subjugate the colony to the Crown. But as revolutionary fervor continued to grow, he was forced to flee again. This time, he took refuge on the HMS Cruizer, a British warship patrolling the nearby waters. On the morning of July 18, Martin’s dreams went up in flames when he scrambled from his berth aboard the Cruizer to witness Fort Johnston falling victim to an inferno started by Cornelius Harnett, John Ashe, and a large group of Cape Fear Patriots.

During the war that followed, British troops camped for a time at the ruins of the fort, but there was no fighting at the site.

Just across Bay Street from the City Pier stands the much-altered two-story building that was constructed when the fort was rebuilt around 1800. From its commanding position overlooking the river, this historic structure is the centerpiece of the modern Fort Johnston, which, at eight acres, may be the smallest active military installation in the United States. The old building is used as living quarters for the commander and other officers at the Sunny Point complex. A state historical marker for Fort Johnston stands nearby on Bay Street.

Return to your vehicle and drive one block north on Howe Street to Moore Street. Turn right and proceed east through downtown Southport for four blocks to St. Philips Episcopal Church. Constructed about 1860, the white frame building holds treasures inherited from St. Philips Church at Brunswick Town. Among the fixtures predating the American Revolution are the baptismal font, the altar cloths, and the wooden collection plates.

It is another two blocks on Moore to the Old Smithville Burying Ground, located at the northeastern corner of Moore and Rhett Streets.

Southport celebrated its bicentennial in 1992, but its roots as a seafaring village can be traced to the settlement that grew up around Fort Johnston before the Revolution.

The town was originally named Smithville in honor of Benjamin Smith (1756–1826), one of the greatest soldiers and statesmen of the colony and state. The Old Smithville Burying Ground, consecrated as a cemetery in 1792, holds the remains of Smith, whose life ended in great tragedy and sorrow.

Born in the lap of luxury, Smith was the grandson of “King Roger” Moore. At the age of twenty-one, he served as an aide-de-camp to George Washington in the brilliant American retreat from Long Island in August 1776. Three years later, he was with William Moultrie in South Carolina when the British were driven from Port Royal Island. Following the war, Smith enjoyed a successful political career. He was elected governor of North Carolina in 1810.

At one time, his personal wealth seemed boundless. He owned Belvedere Plantation, Orton Plantation, Smith Island (Bald Head Island), Blue Banks Plantation (located on the Northeast Cape Fear River), a winter residence in Brunswick Town, a summer residence in Smithville, and twenty thousand acres in Tennessee (a gift in recognition of his Revolutionary War service).

It was Smith’s generous nature that led to his downfall. After signing as a surety for the debt of a friend, he was forced to sell his vast holdings to pay creditors when the friend defaulted. As a result, he became a virtual pauper.

On the stormy night of January 10, 1826, the penniless hero lay dying in a cold, decrepit house on Bay Street, attended only by his physician friend, Dr. Clitheral, and the physician’s wife. Mrs. Clitheral described the pitiful scene this way: “The large street door flew open nor cou’d the strength of one man close; in intervals was heard, the hard breathing and thicken’d ejaculations of the dying.—A quilt had been fastened from the head of his bedside, to supply the place of the door, its flappings, add[ing] to the cold air of the apartment.”

At length, Smith gasped, “Doctor, doctor, oh, doctor!” and then a convulsive struggle brought to a close the life of one of the most colorful figures of the Cape Fear.

The tour ends here, at Smith’s final resting place.