Chapter Seven

The Hell that was Boulogne

22–25 May 1940

‘There was little food and ammunition left and no more water, and after another hour of the greatest discomfort I decided my position was now quite hopeless and that a massacre would occur if I did not capitulate.’

Major Jim Windsor-Lewis, 3 Company, 2nd Welsh Guards on

surrendering his final position in the Gare Maritime at Boulogne.

Having taken Abbeville, elements of the 2nd Panzer Division reached the channel coast at Noyelles shortly before nightfall on 20 May and there, without instructions for the next move, they halted. The speed of Guderian’s race for the sea had taken both the Allies and the Wehrmacht by surprise and it was not until the evening of 21 May that Guderian was ordered to move north and capture the channel ports. His immediate plan was for the 10th Panzer Division to move on Dunkirk via St Omer while the 2nd Panzers seized Boulogne and the 1st Panzers advanced on Calais. Then, perhaps with the Arras counter-stroke still playing on his mind, von Rundstedt held back the 10th Panzers and withdrew them from Guderian’s command in a move that infuriated Guderian and delayed the attack on Dunkirk. Not to be outdone the wily German ‘panzer leader’, without waiting for orders from his immediate superior von Kleist, ordered his remaining two divisions north to take Boulogne and Calais. Although the 10th Panzers were restored to Guderian’s command on 22 May and redirected to Calais, there would be a further Halt Order on 24 May (see Chapter 9) that would have further far-reaching repercussions.

In London, Churchill passed responsibility for the defence of the Channel ports to General Ironside, reasoning that Gort was preoccupied with maintaining the integrity of the BEF and thus had little time to deal with them. London based, Ironside had little first-hand intelligence as to exactly how many German units were operating in the Pas de Calais and was forced to rely on Lieutenant General Sir Douglas Brownrigg’s inaccurate estimation of German forces. Had Brownrigg been correct in his assertion that only light enemy reconnaissance units were at large in the vicinity, the notion of inserting a blocking force into Boulogne and developing Calais as a supply base for the BEF would have been quite logical but as events turned out Brownrigg’s information was dangerously wrong and his subsequent interference, which must have influenced Ironside’s planning, resulted in the destruction of several of the finest British infantry regiments of the day.

The 2nd Panzer Division, under the command of 57-year-old General Rudolph Veiel, began their advance on Boulogne at dawn on 22 May. With the intention of encircling the town he divided his force into two combat groups: Combat Group von Prittwitz which advanced along the coast road via Etaples to attack west of the River Liane and Combat Group von Vaerst which advanced along the N1 towards Baincthun and the high ground of Mont Lambert. If Veiel thought his move north was going to be easy, however, he was mistaken as both columns came under fierce attack from RAF Fighter Command and French ground forces. At Neufchâtel, just south of the Forêt Domaine d’Hardelot, Oberleutnant Rudolph Behr’s platoon of panzers ran into units of General Pierre Lanquetot’s French 21st Division at 12.30pm:

‘While I feverishly try to discover the positions of the anti-tank gun, I see a little cloud of dust and smoke rise up from the panzer ahead. That was a hit! Next moment the hatches are open, the panzer commander drags himself out and falls down to the rear and remains on the ground at the crossroads. The other two men of the crew dismount and run behind my [tank]. In the next second my panzer is trembling from a hard metallic blow, the combat compartment is full of sparks as from a rocket during a firework display. The driver is slumped downwards, his head hangs forward. In the gloom and still dazed I perceive blood running over his face. There is nothing for it but to get out.’1

Behr survived the encounter with the loss of two panzers but had run into the defence line between Samer and Neufchâtel where the French 21st Division had deployed most of its 75mm artillery and anti-tank batteries. It was a desperate struggle but by noon most of those guns and crews had been largely destroyed and as the remnants of Lanquetot’s division withdrew to Boulogne.

Further north meanwhile, Brownrigg, who had moved his headquarters to Wimereux from the Imperial Hotel, was still trying to organize a defence with the mixture of units that had trickled into the port over the previous few days. Amongst these were Captain George Newbery’s party of 70 officers and men of the 7/RWK and Major Tom Penlington and 74 officers and men from HQ Company, 5/Buffs, together with a number of men from the DLI whom he had picked up at Nucq. These men were joined later by the remnants of C Company, 5/Buffs, swelling their number to some 140 officers and men. More substantial was the 1,200 men of 5 Group AMPC, a large proportion of which were elderly reservists – many of them unarmed – who had retired from Doullens with their commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Donald Dean VC.

A Territorial officer, Dean had been awarded the VC in September 1918 serving as a lieutenant with the 8/RWK and, as one would expect from such a man, had led his party in a remarkable journey overland by train and truck – during which time they had had a brush with the 6th Panzer Division – to arrive at Boulogne on 21 May. Dean’s party were immediately set to work as labourers on the docks and in guarding Brownrigg’s rear headquarters BEF at Wimereaux. On 22 May Newbery and the West Kents were detailed to hold two road blocks at Huplandre, 3 miles out on the St Omer road which is where they came into contact with the advanced units of Combat Group von Vaerst:

‘At 3.00pm the refugee stream stopped and all was quiet and peaceful. Suddenly the enemy hurled an attack at the French who were out of sight across the stream to our right. Ten tanks were heard to advance – firing became incessant – something exploded and continued to send up a thick column of smoke – an aeroplane strafed and shots whistled across our front and into the farm. Tanks and artillery followed by infantry were then seen mounting the hill to our right.’2

Newbery noted that the Welsh Guards had by this time taken up positions about one mile behind him.

On the morning of 21 May, having just completed an arduous night exercise with the 2/Irish Guards, Lieutenant Colonel Sir Alexander Stanier, commanding 2/Welsh Guards, was back at the tented camp at Old Dean Common near Camberley. Tired from the ardours of military manoeuvres and hoping for a few hours rest, he confessed to being somewhat dismayed at the arrival of a dispatch rider with movement orders at 11.30am. Half an hour earlier, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Haydon had received an identical dispatch giving the 2/Irish Guards 4 hours in which to pack up and leave for Dover.

Not only did Haydon feel that the new orders ‘could not have arrived at a more inconvenient or tiresome moment’ but this was the second occasion in less than two weeks that he had been called upon to sail to the continent with a small force of Irish and Welsh Guardsmen. On 13 May he and his men had landed at the Hook of Holland to cover the evacuation of the Dutch Royal Family and had only re-embarked by the skin of their teeth 48 hours later, leaving behind eleven dead Guardsmen.3

Arriving at Dover, amidst the chaos of an air raid warning, Stanier and Haydon were finally told by Brigadier Fox-Pitt, commanding 20 Guards Brigade, that their destination was to be Boulogne and to get their men aboard the requisitioned ships. The ensuing dockside confusion resulted in both battalions having to proceed across the channel with a proportion of their men and equipment in separate ships, which in the case of 1 Company and Captain Conolly McCausland of the Irish Guards, meant they were only able to take up their defensive positions thirty minutes before the first German attack commenced at 5.30pm the same evening.

Stanier disembarked at Boulogne at almost exactly the same spot as that which he had first set foot in France as a young subaltern in 1918. This time he was met by ‘hundreds and hundreds of all kinds of troops standing on the quays’ along with numerous wounded and civilian refugees all jostling for space aboard the newly arrived ships that were unloading the Guards Brigade. The majority of these men were non-combatants who were deemed to be making inroads into increasingly scarce resources and were now being evacuated on orders from Gort.

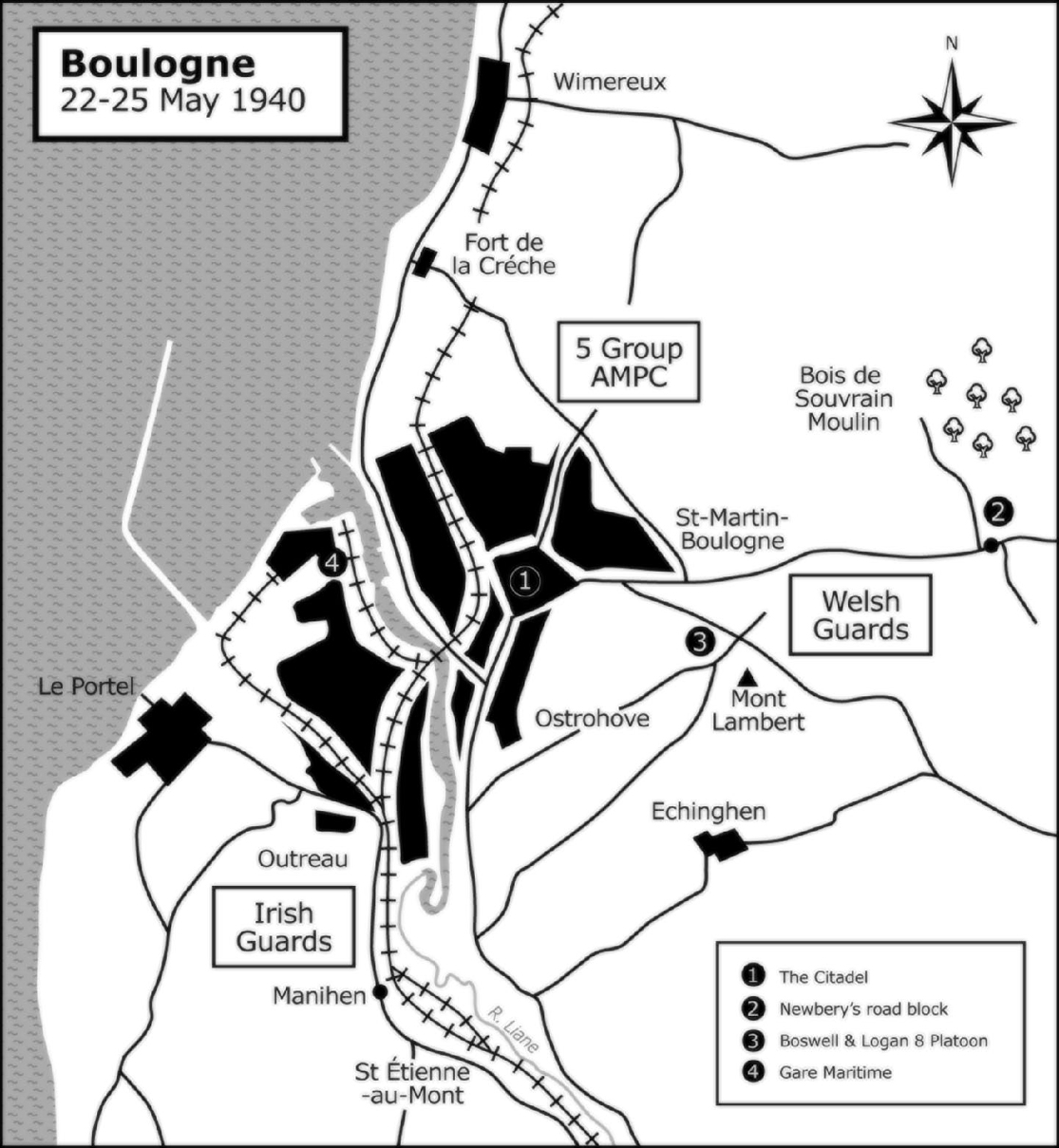

Even the most casual of observers will have little difficulty in noting that Boulogne is a town surrounded by high ground which, although bisected by the valley of the River Liane, immediately dictates the nature and location of any defensive position. From the harbour the Rue de la Lampe climbs before turning into the Grand Rue and continuing its steep ascent to the walled Citadel or Haute Ville, 2½ miles beyond which are the heights of Mont Lambert at 950 feet above sea level. To the west of the river the ground is more undulating and incised with steep valleys. The question of which flank the two battalions would defend was decided by simple mathematics; with the Welsh Guards fielding over 250 more men than the 680 officers and men of the Irish Guards, the longer eastern perimeter was allocated to the Welsh.

Stanier was ordered to hold two sides of a 5-mile triangular perimeter with Major Hugh ‘Cas’ Jones-Mortimer and 2 Company holding a line from the River Liaine to Ostrohove and Major Jim Windsor-Lewis and 3 Company continuing the defensive line up to the crossroads near Mont Lambert. Captain Jack Higgon and 4 Company dug themselves in along the approximate line of the present day D341 as far as the church at St-Martin-Boulogne where they eventually linked with the right flank of Captain Cyril Herber-Percy’s 1 Company after his late arrival. All of which left 3 Company on the apex of the triangle in the shadow of Mont Lambert and facing one of the main roads into the town from the extensive Forêt Domaniale de Boulogne. It was a critical position: if Mont Lambert fell to the Germans then Boulogne would unquestionably follow. Jim Windsor-Lewis would have been under no illusions as to its importance but with only three anti-tank guns at his disposal he and his men were going to be hard pressed to hold a sustained enemy attack.

Haydon was faced with defending a perimeter of over 2 miles. He initially positioned his three companies from the harbour breakwater north of Le Portel to the village of Manihen which sits above the Liane valley. Holding the left flank around the high ground just south of Outreau was Captain Murphy and 4 Company while to their right was Captain Madden’s 2 Company holding Outreau. From Outreau to the sea was the responsibility of Captain Campbell Findlay and 3 Company. The late arrival of 1 Company and Captain Conolly McCausland completed Haydon’s deployment and they were squeezed into position on the high ground leading up towards St-Étienne-au-Mont on the extreme left flank.

At around the same time as Oberleutnant Rudolph Behr had run into French anti-tank guns at Neufchâtel, scout vehicles of 2nd Panzer were seen on the ridge overlooking Outreau from the south and at 3.30pm Captain McCausland’s company came under fire from the artillery of Combat Group von Prittwitz. Brigadier Fox-Pitt was still unsure of the exact location of the units of the French 21st Division, although if better communication between the various British units had existed he would have been aware of the contact made on the St Omer road by Newbery’s men. Notwithstanding, he dispatched Lieutenant Peter Reynolds and a patrol to discover the whereabouts of the French to the south which apart from being fired upon north of Nesles, failed to see any French or enemy units. Hardly surprising as the surviving men of the French 21st Division were by now dispersed around the Boulogne perimeter and Lanquetot himself had taken up residence in the Citadel. However, Fox-Pitt did not have to wait long before the attack intensified. Colonel Haydon’s account:

‘At approximately 5.30pm, shelling recommenced on the left of the battalion’s front and this shelling was followed by an attack which was accompanied by tanks, but which was not heavily pressed. The leading tank advancing up the road towards Outreau was engaged by an anti-tank gun commanded by 2/Lt [Anthony] Eardly-Wilmot. Seven direct hits were obtained and the tank came to an abrupt halt and never moved again ... Number 1 Company’s advance platoon on the lower road near the river was to all intents and purposes isolated from the remainder of the company.’4

Forty-five minutes later, almost at the same time as a short air raid, a second platoon came under attack after which there was a lull until 10.00pm when 1 Company again took the weight of the enemy assault. This time the enemy overran two sections and destroyed two anti-tank guns in the process, an encounter from which few guardsmen managed to escape. Haydon quickly moved the Carrier Platoon into Outreau to block all roads and prevent any further penetration into the battalion’s positions, his written account betraying his unease that the lower road into Boulogne running parallel to the river was now open to the enemy and that he had no reserve, let alone any heavy weapons, to support a counter-attack.

That afternoon the Welsh Guards also had their first sight of von Vaerst’s Combat Group on Mont Lambert in the form of motorcycle units and some artillery which began to shell the light railway behind the Welsh lines. Soon afterwards tanks appeared, probing the 3 and 4 Company positions. Guardsmen Arthur Boswell and Alf Logan with 8 Platoon initially thought the large tank that appeared on the 3 Company front was French:

‘Look Alf, I said, It must be one of those big French tanks – they were seen on cinema news-reels before the war – but it turned out to be a German tank! In a matter of seconds all Hell broke loose. The baptism of fire of the 20th Guards Brigade had begun in earnest. The tanks withdrew as the light failed and after some sporadic gunfire an uneasy calm fell across the line.’5

Apart from copious amounts of small arms ammunition (SAA) being expended, little more took place that evening but, as Stanier remarked later, all they had succeeded in doing was giving away their positions. The Guards still had a lot to learn about their adversaries.

In the early hours of 23 May 200 of Deane’s pioneers were sent to reinforce the Welsh Guards’ left flank running from St-Martin-Boulogne to the Casino on the northern edge of the dock. It was a force which also included Major Tom Penlington and his 5/Buffs. When the expected dawn attack failed to materialize there was an uneasy lull until 7.30am, when the Germans fell on both the Welsh and Irish positions simultaneously. At the Mont Lambert crossroads it was Arthur Boswell’s platoon that once again found itself at the forefront of the fighting. Having ‘volunteered’ to go for breakfast he and Alf Logan had just climbed out of their trench ‘when a German machine gun opened fire. Alf and I slid back into the hole and Jack dropped flat just behind’. But it was only the prelude. Moments later Lieutenant Colonel Stanier, who was at 3 Company Headquarters, observed tanks heading down the road from Mont Lambert village:

‘I saw the German tanks come bursting out of the village and start firing at the little anti-tank guns which were just in the hollow below me. They put one of two rather close to the farm where I was peering over the wall. They fired at the men holding the crossroads at Mont Lambert. They burst out of the village one behind the other and spread out. They were in threes; one would be in front and the other two would be looking out either side to protect it.’6

Second Lieutenant Neil Perrins and 9 Platoon were next in line as 3 Company came under increasingly accurate shellfire. Dug in on the Boulogne side of the crossroads Perrins’ platoon was under heavy machine-gun fire from a tank moving downhill towards 3 Company Headquarters where Corporal Joseph Bryan and three anti-tank guns from 20/Brigade Anti-Tank Company were positioned:

‘Sergeant Green alerted us all to a tank that was coming down the same track as the other one, but it came a little closer to us. This was stopped – fired on by all three guns and it was stuck there. You could see using the telescopic sights of these old guns – you could see very clearly that one of the occupants had got out and was on the opposite side of the tank crawling on his hands and knees to keep out of the fire.’7

But tanks were not the only problem facing the Welsh. The crossroads was continually under sniper fire from fifth columnists and Second Lieutenant Peter Hanbury’s suspicions that 12 Platoon were under fire from the church at St-Martin-Boulogne were heightened when a round hit his trouser leg:

‘I went up to the church to see if anyone was up the tower. I did not wish to upset the priest so took off my tin hat, which he thought strange, so I put it back on and started climbing the stairs. He dragged me down. Then I understood there was a fifth columnist or a parachutist up there ... I returned to my platoon and ordered Bartlett and another guardsman to neutralize his fire with two Bren guns. They slowly shot off the top of the tower and said a rifle had been dropped from the tower. Whether they had killed the opposition or wounded him I do not know but he stopped firing.’8

As the attack grew in intensity the Anti-Tank Platoon under Second Lieutenant Hugh Hesketh ‘Hexie’ Hughes – in position at la Madeleine south of the Mont Lambert crossroads – had decided to withdraw after one of his guns had been knocked out and enemy tanks were now moving behind him. Reasoning he would soon be surrounded he gave orders to fall back across the road to the shelter of the Café Madeleine . He and half his platoon never made it. Another lesson had been learned – albeit at some cost – that moving from a good position of cover whilst under fire is inadvisable, even if the second position appears to be better.

Aware that the battle for the high ground was now lost, Stanier decided the moment had arrived for a withdrawal to form a new perimeter around the docks, a move that was not as straightforward as one would expect. As he later remarked, ‘you must remember we had no maps to speak of – and men had to find their way as best they could.’ But as 3 Company fell back Second Lieutenant Ralph Pilcher’s 8 Platoon found itself cut off on the Mont Lambert crossroads. Arthur Boswell could see at least one enemy tank moving in their direction and several more were heard behind them. Pilcher gave orders for his men to make for a nearby wood one by one:

‘I climbed out slowly and after glancing at the menacing tank to see if there was any movement, crawled very slowly towards the comparative safety of the nearby wood. I have never been so scared as I was then – I could feel the hair on the back of my neck curling! Further into the wood I joined Lieutenant Pilcher, Sergeant Pennington, Corporal Webb and others; about twelve in total.’9

Reports become confused at this point, illustrating perhaps the uncertainty that existed as the Welsh lines were penetrated. Hanbury writes that Captain Henry Coombe-Tennant appeared – having been sent by Captain Jack Higgon commanding 4 Company – and told him to move back to the light railway with his platoon to prevent the enemy from getting behind them. Sometime later Higgon met Hanbury again at 4 Company Headquarters, at La Madeleine crossroads and they had a hurried exchange:

‘Hanbury appeared to give me his situation, bringing with him a few stragglers from 3 Company. Then Guardsman Potter, the battalion orderly arrived on a motorcycle, with a verbal message for us that we were to withdraw at once to the quay. I ordered Coombe-Tennant to take charge of the Company Headquarters and the wounded and directed him to evacuate them in a lorry which was near our position. In the meantime Hanbury was to take over 3 Company and remain in position until 11 Platoon had passed through them ... The enemy could see our movements and proceeded to shell and machine gun our route heavily and accurately, causing a number of casualties. I came back with 10 Platoon and when they had passed I told Hanbury he could move. Then he and I followed his men until we came to his own platoon [12 Platoon] which had been acting as a rearguard under Heber-Percy.’10

Sergeant Denys Cook was with 12 Platoon when the order was given to withdraw to the quay:

‘The commander of another company [possibly Captain Heber-Percy] ordered me and my platoon to fall back toward the centre of the city, for by this time the street corner was a shambles. I found my company with our regimental headquarters in an area that in peacetime would have been a market or bus terminal. More roadblocks were erected at the foot of the hill and around the square near the wharf side.’11

Windsor-Lewis and what was left of 3 Company withdrew to the Citadel sending a message to brigade headquarters letting them know his location. Later in the afternoon he was ordered to put up roadblocks in the town which was carried out with three sections of men who came under ‘intense machine-gun and rifle fire’ from the houses opposite. German infantry had managed to occupy a house on the left flank but ‘were dealt with by the Bren gun fire’ of one of the 3 Company sections. Windsor-Lewis was now established in a large white house at the junction of Rue du Mont St Adrien and Rue des Victoires.

To the west of the Liane the Irish Guards were under similar pressure as the attack opened against 4 Company dug in around the reservoir and high ground north of Manihen. Heavy shelling accompanied the assault, which initially focused on the forward platoon commanded by Lieutenant Peter Reynolds. Reynolds’ platoon had, as Haydon noted at the time, already been ‘rendered somewhat precarious by the destruction of 1 Company’s forward platoon which had been in position immediately to its left’. It was hardly a fair contest and despite Lieutenant Simon Leveson and a section of his carrier platoon coming to their aid, German tanks soon overran the position and surrounded the hapless guardsmen. Orders to withdraw never reached Reynolds and Leveson who were killed defending their positions.

Reynolds was the third member of his family to be killed in action, his father, Major Douglas Reynolds was awarded the VC at Le Cateau in 1914 and was killed in 1916 and his brother-in-law, Lieutenant William Petersen, was killed in 1914 serving with the Life Guards at Zillebeke. Commanding another 4 Company platoon was Second Lieutenant Jack Leslie:

‘There were bullets flashing all around us in our trenches and a lot of noise – people were shouting at the tops of their voices and the next thing we knew was a German sergeant appeared some yards away wielding a stick grenade shouting, ‘Aus, Aus, Aus’. There was nothing for it but to get out of our trench. If we hadn’t he would have blown us all to pieces.’12

Leslie survived – and was taken prisoner along with Lieutenant Pat Butler and the survivors of 4 Company. When contacted in 2000 by historian Jon Cooksey, he claimed he could still ‘smell’ the exhaust fumes of the panzers’ engines in his nostrils from the time he was marched past them into captivity sixty years earlier. From a company roll of 107 officers and men only 19 returned to England.

With 4 Company effectively destroyed and enemy units now pushing forward Haydon was left with no alternative but to shorten his perimeter by withdrawing into Outreau:

‘Thus at this time the line ran from the post held by 1 Company in the village of Outreau itself, covering the road down the hill to the quay, and the road leading to Battalion Headquarters, through some fields which gave a field of fire of some 150 yards on its northern exits from Outreau, and thence to the original position held by 3 Company.’13

Leaving 21-year-old Second Lieutenant George ‘Gipps’ Romer’s platoon in place at Outreau, Haydon’s men withdrew under fire downhill to their new positions, Romer finally receiving orders to retire at 11.45am. There is little doubt that in holding his ground at Outreau, Romer had made it possible for the battalion to retire relatively intact. Haydon was full of praise for his platoon’s stand:

‘They had been in close contact with the enemy for nearly two hours at a range of not more than 30–50 yards. Throughout that time the posts had exchanged bursts of fire one with the other and all attempts to outflank 1 Company’s position had each, in turn, been defeated. In my opinion, the holding of this post by 1 Company, which might easily have been somewhat demoralized by the very heavy losses which the company had suffered, reflects the greatest credit on Capt C R McCausland and 2/ Lt G Romer, and on the other ranks who held the post. I was very apprehensive as to whether they would be able to withdraw from such close contact without further heavy losses. The fact that they were able to, shows they must have made the fullest and most effective use of the ground.’14

At 1.00pm Haydon ordered a further retirement towards the docks, a move that was accompanied by severe shelling and several skirmishes with enemy tanks. It took a good hour to cover the final half mile down to the docks around the Bassin Napoléon where barricades were erected and the remaining men of the battalion ordered to take cover in the variety of sheds and warehouses that lined the dockside.

Meanwhile there had been a profusion of signals between Whitehall and Boulogne. The initial order for all fighting men to remain in Boulogne ‘to the last man’ had prompted Fox-Pitt to signal London with a rather terse request for air cover and heavy artillery, without which he said, Boulogne could not be held. His reply clearly had some effect as, with what must have been some relief to all concerned, the order was rescinded at 6.30pm and the evacuation ordered to go ahead. Unfortunately Lieutenant Colonel Stanier was unable to contact all his company commanders:

‘At 6.00pm, orders came to withdraw into the railway yard and await destroyers who would come into the harbour. I sent an orderly to 3 Company but they could not be found. I had pointed out a white house to Major Windsor-Lewis and suggested that it might make a good Company Headquarters, I myself went to this white house, but there was no sign of Major Windsor-Lewis.’15

With Number 1 Company already across the Pont Marguet and 2 and 4 Companies about to march across, Brigadier Fox-Pitt – who had installed his brigade headquarters in the nearby Hotel de la Paix – warned Stanier that regardless of the whereabouts of Major Windsor-Lewis and his men, the bridge was about to be destroyed. Fully aware that the destruction of the bridge ‘wasn’t a very pleasant decision to make’ and would in effect isolate Windsor-Lewis and the men of Deane’s AMPC detachment, the bridge was blown by naval demolition parties on the orders of Fox-Pitt.

The chances of carrying out a successful evacuation by sea of the 20 Brigade survivors and the waiting lines of ‘useless mouths’ appeared to defy the odds. German artillery was in command of the heights above Boulogne and a hail of gunfire was being directed at the harbour and its approaches. Added to that, German armour was forcing its way through the narrow streets of the town and making life extremely difficult, not only for the Guardsmen defending the dockside area, but also for the crews of the destroyers entering and leaving the harbour.

At 6.45pm the Luftwaffe appeared overhead in some strength, Haydon thought that there were over 100 machines in the air and about 10 of our own fighters; some of which could well have been Hurricanes of the Canadian 242 Squadron flying from Biggin Hill who reported five losses on 23 May. While the twin-engined Heinkel 111s bombed the town the most immediate danger was that posed by the Junkers 87s attacking the destroyers of the Dover Flotilla which were now returning to Boulogne to evacuate the troops they had delivered the previous day. HMS Keith and HMS Vimy were the first to enter the narrow harbour followed by HMS Whitshed and Vimiera who packed their decks with wounded and non-combatants and withdrew under a storm of fire. Next to arrive were HMS Venomous and HMS Wild Swan which entered the harbour and berthed either side of the Gare Maritime on the west side. Lieutenant Commander John McBeath berthed the Venomous on the eastern side of the Gare Maritime and ordered his gunnery officer to open fire with the ship’s main armament on the German tanks and tracked vehicles that were now approaching the harbour.

Able Seaman Don Harris was on the bridge of HMS Vimy as they followed the Keith into the narrow harbour:

‘I noticed our Captain, Lieutenant Commander Donald, train his binoculars on a hotel diagonally opposite but quite close to our ship. I heard another burst of firing from the snipers located in the hotel and then saw our captain struck down. He fell onto his back and as I leapt to his aid I saw a bullet had inflicted a frightful wound to the forehead, nose and eyes of his face. He was choking in his own blood so I moved him onto his side, and it was then I received his final order. It was ‘Get the First Lieutenant onto the bridge urgently.’ As I rose to my feet more shots from the hotel swept the bridge and the Sub Lieutenant fell directly in front of me. I glanced down and saw four bullet holes in line across his chest. He must have been dead before he hit the deck.’16

The 21-year-old Sub Lieutenant Douglas Webster was dead and 35-year-old Lieutenant Commander Colin Donald died from his wounds at Dover later that day. Both men were victims of the open bridge structure which characterised the V and W Class destroyers of First World War vintage.

Although HMS Keith was a B Class Destroyer and commissioned in 1930 it still had an open bridge which is where Sub Lieutenant Graham Lumsden was when the air attacks began in earnest:

‘One squadron of 30 Stukas proceeded to attack the 3 destroyers outside the harbour sinking a French [L’Orage] and damaging a British destroyer. The remaining 30 Stukas in single line wheeled to a point about 2,000 feet above us and then poured down in a single stream to attack the crowded quay and our two destroyers. The only opposition to this was scattered rifle fire mostly from soldiers ashore and the single barrelled two-pounder pom-poms in each destroyer. As the attack began, with immediate and terrible effect on the quay, the Captain ordered the bridge people below because the bridge was just above quay level and therefore exposed to splinters from bombs bursting there.’17

Seconds later 47-year-old Captain David Simson was fatally hit by a German sniper and fell dead on the bridge. The next few rounds narrowly missed the coxswain but wounded Adrian Northey, the ship’s first lieutenant, in the leg and hit the torpedo officer in the arm, resulting in a nervous Lumsden stepping up to manoeuvre the ship out to sea:

‘The First Lieutenant, now our Captain, asked me if I could take the ship out. I had never commanded a ship going astern and certainly not down a narrow and curving channel peering through a small scuttle with bullets hitting people between me and the men who would carry out my orders.’18

It was, in the opinion of Lieutenant David Verney, more like a ‘Wild West shootout’! With no time to cast off, Keith broke her mooring ropes and as Lumsden successfully brought the ship out of harbour they passed another ship going into Boulogne.

The journey across the water to Dover was a short one and it wasn’t long before HMS Whitshed, accompanied by the Vimiera, was again approaching Boulogne. The Whitshed was commanded by 39-year-old Commander Edward Conder, the eldest son of the Canon of Coventry Cathedral. After the death of Captain Simson, Conder assumed the mantle of Flotilla Commander and the senior naval officer at Boulogne. The Whitshed’s guns had a considerable bite and were quickly brought to bear on targets in and around the harbour:

‘A section of Irish Guards were engaging with rifle fire an enemy machine-gun post, established in a warehouse, as coolly and as methodically as if they had been on the practice ranges. “Tell the foremost guns to open fire,” the Captain yelled. The guns swung round and with a crash two 4.7-inch HE shells tore into the building and blew it to the skies. Meanwhile the German infantry now passed ahead of the tanks and infiltrated closer and closer to the quays, the fine discipline of the Guards earned the open mouthed respect of all. Watching them in perfect order, moving exactly together as though on parade ground drill, it was difficult to realize this was the grim reality of battle.’19

Although Whitshed had taken off the surviving members of the brigade anti-tank platoon the main body of guardsmen were taken aboard HMS Wild Swan and Venomous. By 9.30pm Haydon and the Irish Guards were safely aboard Wild Swan and no doubt many of them were witness to the unfortunate HMS Venetia being hit amidships by one of the coastal guns that the Germans had managed to repair at the Fort de la Creche. Erupting in a sheet of flame the destroyer was in great danger of capsizing and blocking the narrow channel into the port. Haydon’s account:

‘The commander of the Venetia however, completely saved the situation by going astern at full speed, firing with every gun that he could bring to bear, and altogether ignoring the fact that the quicker he steamed the quicker the flames spread. There is no doubt that the units on the quayside owe the officers and crew of the Venetia for their great courage and bold seamanship. The same debt is owed to the officers and crews of the remaining ships who remained alongside the quay embarking wounded and unwounded.’20

The quick thinking of 34-year-old Lieutenant Commander Bernulf Mellor had saved the day but it was to be his last active service engagement as the wounds he received at Boulogne consigned him to a desk job for the remainder of the war.

At 9.30pm the vast majority of those guardsmen who had made it back to the quayside were steaming out of the harbour. At Dover the reality of just how many men had been left behind became clear to a distraught Stanier: not only had 3 Company not made it back to the ships but a substantial number from 2 and 4 Company were also missing. Some of those eventually turned up having boarded HMS Windsor at 11.00pm with little enemy interference.

Probably not of direct concern to Stanier was the large contingent of Lieutenant Colonel Deane’s AMPC which had been left very much to its own devices to withdraw to the harbour. Making their way to the quayside and crossing the partially demolished Pont Marguet, Deane and his men were preparing to make a last stand along with a number of guardsmen and other stragglers when a ship was seen just offshore. Signalling frantically with a torch Deane and his men were overjoyed to watch HMS Vimiera slowly back into the harbour under the very noses of the Germans. In total silence Lieutenant Commander Bertram Hicks and his crew embarked 1,400 officers and men and slipped away in the small hours of 24 May without a shot being fired.

Realizing the remainder of the brigade had gone Jim Windsor-Lewis collected together those remaining stragglers who had not joined Captain Higgon’s party – which had attempted in vain to break out towards Étaples – and made their way to the quayside by the Gare Maritime where they settled down to wait for the Navy to arrive. It was not long before their presence was detected:

‘The Germans then began to open fire upon us in the sheds and several men were wounded. I immediately began to retire my force to the station. This was quite easily effected as there was a covered way of approach afforded by a line of railway trucks. The fire from the German tanks was quite severe when we abandoned the sheds which shortly afterwards went up in flames. The Germans then began to fire incendiary bombs into the station and several of those lit up trucks which contained ammunition and inflammable material. I hastily prepared the station for defence by the erection of a sandbagged breastwork in front of the station and on the left flank overlooking the town and custom house.’21

By midday on 24 May Windsor-Lewis and his men had completed their work and kept the Germans at bay for another 24 hours, defying all attempts to prise them from their positions despite the weight of fire being directed at them:

‘Firing from the German tanks, of whom 3 were in front of our position, continued all day, sometimes intense at other times mild, and after 11.00pm, dying down altogether. In the evening of 24 May, about 6.00pm, the Germans made an effort to land a boat on my right flank. Their party of infantry was a small one and we drove them back to the other side of the harbour with Bren and [anti-tank] rifle fire, inflicting losses on them.’22

Still holding out hope of rescue or at least reinforcements the diminishing group held on through the night until the next day when it became obvious to Windsor-Lewis – by now wounded and walking with difficulty – that to continue would be pointless. Guardsmen Syd Prichard and Doug Davies had good cause to remember the surrender:

‘Everybody was dirty and everybody did their stint. Lewis told us there was no hope – there was no way we were getting back. We were on this train [stationary in the Gare Maritime], just three of us firing, Windsor-Lewis was behind us with a load of sandbags and we did not know he had put the white flag up because we were firing after the white flag had gone up. I always say that Syd and I were among the last three blokes in action at Boulogne.’23

During Windsor-Lewis’ stand at the Gare Maritime General Lanquetot, with a mixed force of French soldiers and marines, had been holding out in the Citadel. There appears to have been little communication between Fox-Pitt and the French commander and no French troops had been seen on the perimeter defences, in fact it was not until the Guards fell back that the Citadel came under any enemy pressure. By the morning of 25 May the enemy assault had reduced the garrison to the confines of the fortified Calais Gate and permission was granted from the French command at Dunkirk for surrender.

The subsequent French complaint that the British had abandoned Boulogne without informing Lanquetot developed into a running sore that ultimately influenced the fate of British forces at Calais – but more of that in the next chapter. There is some truth in the French complaint that Fox-Pitt largely ignored the French presence and was only concerned with the welfare of 20 Brigade. Certainly, the rather cavalier manner in which Deane’s AMPC men were treated in being left to their own devices during the retreat to the quayside, suggests a focused arrogance – understandable to a point – on the part of 20 Brigade Headquarters. Whether informing the French of the decision to evacuate Boulogne would have eased matters between the two governments is debatable but what it did was to add to the growing number of Frenchmen that considered the British were only concerned with their own welfare and lacked the determination to fight the common enemy.

The casualty return for the defence of Boulogne was a heavy one but even today a completely accurate return of who was wounded and taken prisoner is almost impossible to find. The Welsh Guards arrived back at Dover with 13 officers killed or missing and over 400 NCOs and other ranks killed or missing. The bulk of those men were from the three companies that were left behind, the majority of which went into captivity. The Irish Guards recorded 201 men killed, wounded or missing, a number that included 5 officers, however recent research had identified some 25 killed and 15 wounded leaving over 160 as prisoners of war. But whatever the number they, like the Welsh Guards, had lost almost a third of their strength. Number 4 Company had suffered the most, only 19 men answering their names on their return to England.24 Amid the profusion of gallantry awards that followed over subsequent months were a DSO for Haydon, Stanier, Windsor-Lewis and McCausland and an MC for Heber-Percy.

Naval casualties from the ships carrying out the evacuation were approximately sixteen killed, nine of these coming from HMS Venetia. There is no complete record of the number wounded. Amongst the honours announced in the London Gazette of 27 August was Lieutenant Commander Clegg’s award of the DSC for his command of the Venetia after it had been hit on 23 May. The gallantry of the captains of three other ships was also recognized with the award of the DSO to Commander Conder, HMS Whitshed, Lieutenant Commander Roger Hicks, HMS Vimiera and John McBeath, HMS Venomous.

Safely back at Dover Don Harris and the crew of HMS Vimy unloaded their human cargo and refuelled. The arrival of a new captain and fresh orders would no doubt send them back to sea again but in the meantime there was time to get some much needed sleep. It was only when the morning edition of the Daily Mirror appeared on the mess deck with the headline, ‘The Hell That Was Boulogne’ emblazoned across the front page, that Harris and his shipmates allowed themselves a wry smile of satisfaction for a job well done.