Chapter Nine

The Canal Line

20–28 May 1940

‘We advanced in a line through a field on the right. We were met with a fearsome hail of gunfire. We threw ourselves flat on the ground. One of us reached for our machine gun, aimed and gently squeezed the trigger and fired; then he fell to the ground. The group leader jumped up to take the gun but just as he took aim he too was gunned down.’

Infanterist Hofmann coming under fire from B Company, 1/RWF in

Robecq on 26 May 1940.

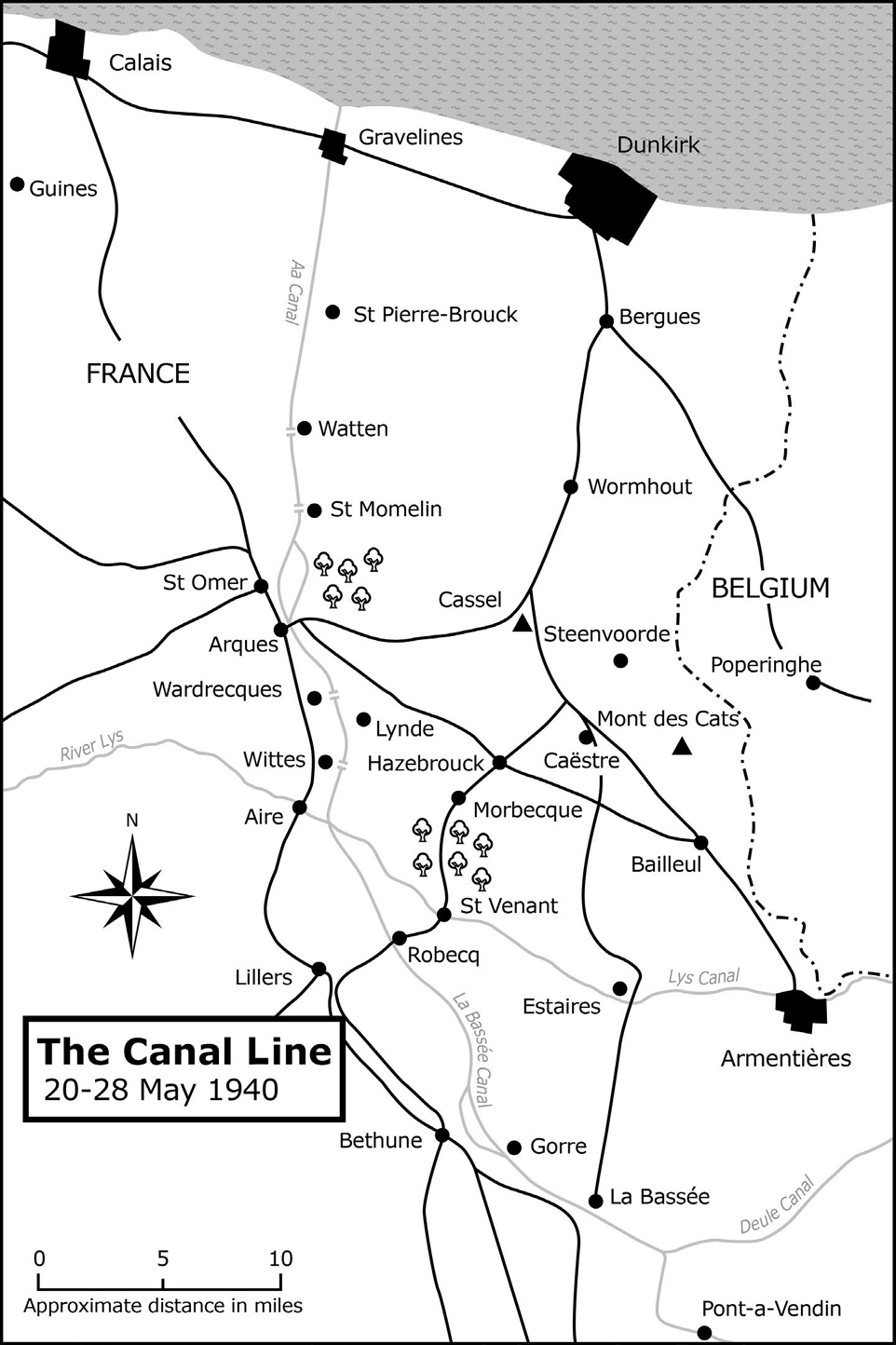

We must now return to the point where we left the BEF withdrawing from Arras and the danger to the British right flank created by the collapse of Belgian forces on the Lys. Lord Gort believed that the German threat was severe enough to move two divisions north from Arras to prevent the BEF’s only avenue of escape from being closed. The threat that the BEF might not only be outflanked but completely encircled had undoubtedly been anticipated well in advance and from 20 May Gort had been moving forces to defend the line of the rivers and canals which run through Gravelines, Aire, Béthune, La Bassée and beyond.

The so-called Canal Line followed the old line of fortified towns which Marlborough had found so necessary to capture in 1710. In 1940 – as they are today – these towns were linked together by an unbroken line of canalised rivers and canals forming a natural barrier to the armoured units of the German Army Group A who were intent on assaulting the rear of the BEF while Gort was facing the pressure of Army Group B from the east. On 20 May ‘Polforce’ had been assembled, under the command of Major General Curtis, to defend the sector between St Omer and Pont Maudit; a development which may have put men on the ground but could hardly be considered to be a coherent fighting force. 137 Brigade, for example, consisted of 2/5 West Yorkshires, men returning from leave known as the ‘Don’ Details and some engineers. Further south, however, Polforce was bolstered by the three battalions of 25 Brigade from the 50th Division and a battery from 98/Field Regiment. To the west, ‘Usherforce’, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Charles Usher, was given the defence of the Canal Line from Gravelines to a point 3 miles south near St-Pierre-Brouck.

On 22 May Major Charles Cubitt and his 25-pounders of 392 (Surrey) Battery arrived on the canal with orders to cover the bridging points along the 15-mile sector between St Momelin and Wittes. There were seven bridges to be covered – at St Momelin, St Omer, Arques, Renescure, Wardreques, Blaringhem and Wittes – and that night one gun was deployed to cover each of them. ‘Everything went smoothly’, wrote Cubbit, with one exception: ‘the second gun of E Troop, destined for the crossing at St Omer, was stopped as it passed through Hazebrouck’ by a staff officer and ordered to defend GHQ which was in the town. Unfortunately another one of E Troops guns was under repair and so the crossing at St Omer was left without artillery, leaving one to speculate on the outcome had 3/RTR – which was still unloading at Calais – been able to arrive in time. However, the 392/Battery gun which had been redeployed was positioned in a garden on the western outskirts of Hazebrouck to cover the road from St Omer and came into action against an enemy column from the 8th Panzer Division advancing up the St Omer road at 2.00pm on 24 May:

‘The first shot disabled one of the leading vehicles. The enemy halted and withdrew, but not without sustaining several more hits from the gun. After about a quarter of an hour the second round of the engagement was opened by the enemy who brought up eleven medium or heavy tanks to attack the gun. As the tanks manoeuvred the gun opened fire. One tank was put out of action by a direct hit and it is probable that at least two others were badly damaged. But the odds were too heavy. Three direct hits were then scored on the gun. The first shell disabled the layer, and his place was at once taken by Sergeant Mordin who was performing the duties of Troop Sergeant Major. The second shot wounded Mordin in the eye, but he carried on until the third shell killed L/Sgt Woolven and badly injured the remaining crew.’1

At that moment the reserve ammunition limber turned up and was destroyed by another direct hit from an enemy tank. With no serviceable gun, Sergeant James Mordin ordered the remaining crew to retire.

Back on the canal the first attacks were launched at 8.30am on 23 May and continued throughout the day, pushing the men of 137 Brigade back to a new line running between Robecq and Calonne. The 392/Battery guns were spaced out along a wide front each gun and its crew fighting its own, independent action. There was some confusion at Arques when the bridge was destroyed at 4.30pm and the gun crew withdrew with the sappers. Ordered back to Arques by Major Cubitt they arrived to find Germans already in the village and came into action near the crossroads about a mile east of the canal. Here they fired nineteen rounds at the advancing enemy before Major Andrew Horsbrugh-Porter arrived with a troop of 12/Lancers and gave covering fire to enable the gun to be limbered up and withdrawn.

The bridge at Blaringhem was defended by a contingent of French infantry, two searchlight detachments and some Royal Army Ordnance Corps (RAOC) personnel. The first attack began at 8.30am and Lance Sergeant Love, commanding the gun, scored direct hits on one tank and two other armoured vehicles. Two hours later a second heavier attack followed, during which the French and British detachments withdrew leaving the 392/Battery gun in position shooting at enemy targets over open sights under the direction of Second Lieutenant Kenneth Payne:

‘In this manner no less than 130 rounds were fired into the advancing enemy and when the German infantry were within hand-grenade range, the order was given to withdraw. Under the very noses of the enemy the gun was limbered up and might well have got away had not an unlucky shell from a German tank severed the engine-connector as the party pulled out of the position. The gun was lost.’2

Kenneth Payne’s award of the MC was announced along with Sergeant Mordin’s DCM in December 1940.

But despite these actions the Germans had got across the canal at St Omer and Wittes and although there was no general advance, the leading troops of the 6th and 8th Panzer Divisions consolidated their hold on the east bank of the canal. At 11.00am on 24 May some thirty enemy tanks from the 8th Panzer Division moved off in the direction of Lynde – heading for Hazebrouck – and it was this column that Sergeant Mordin engaged with his 25-pounder later that day. With GHQ packing up and hurriedly evacuating the town, the defence of Hazebrouck was about to begin – an encounter dealt with in the next chapter.

Further east along the canal the three battalions of 25 Brigade had been in place since 21 May and were defending the sector running from Béthune to Pont-à-Vendin, a distance of just over 15 miles. The 1/Royal Irish Fusiliers, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Guy Gough, were assigned a frontage of just over 6 miles, a sector that Gough quickly recognised was far from ideal. Apart from the difficulties imposed by the ground itself, his initial reconnaissance revealed hundreds of barges which, in places, were packed so tightly together that one could almost cross the canal without getting wet. His worry, that their presence would neutralize the effect of the canal as an obstacle, was shared by the 1/7 Queen’s on his left who had been allocated a 6,000 yard sector running from Givenchy to Salome. Over the next day or so these barges were systematically destroyed, a task that Gough admits was heartbreaking, as ‘we were destroying the homes, the stock-in-trade and the household goods of the Bargees’.

As expected, the 7th Panzer Division’s assaults were focused on the bridging points along the canal and although several of these had been destroyed by 22 May, a further four road bridges and a footbridge were not destroyed until forty-eight hours later, possibly prompted by enemy attempts to rush the road bridge at Béthune on the B Company front. ‘They were stopped short in their tracks’, wrote Gough, ‘with very heavy casualties by withering fire from 11 Platoon.’ The bridge was blown during the second assault. The lessons learned during the retreat of the Fifth Army in March 1918 had still not been fully absorbed by the British Army of 1940 which was having to come to terms with the fact that, unless bridges were totally destroyed and blown to oblivion, enemy infantry were generally able to cross over the wreckage unless the structure remained under fire.

D Company had three road bridges in its sector of canal which ran east from the junction at les Champs Boucquet. In charge was 24-year-old Captain John Horsfall, who despite his age and relative inexperience, was to demonstrate a skill and tenacity on the canal that would earn him the MC. The first real test came soon after the enemy attack on the Béthune bridge when the two forward platoons were located by the enemy:

‘[PSM] Sidney Kirkpatrick’s positions [18 Platoon] gradually became untenable as the enemy pinpointed them, and they were gradually shot to bits. He was hit himself about midday, but although incapacitated he held on until nightfall, saying nothing in the meantime. Connolly had already been killed and his number 2 wounded. Kirkpatrick had taken over the Bren and was still in action with it, with the assistance of Fusilier Wilson, when the run of luck ended for both of them. As the blast from the Spandau came through the place their gun was wrecked, Wilson lay dead and Sidney had a bullet through the shoulder with another that ripped down the side of his leg and had stripped off his gaiter buckles.’3

In the space of an hour 18 Platoon had lost eight men and had been reduced to only one working Bren gun.

On 25 May the battle intensified as enemy artillery units were brought into play. Horsfall admits that had the enemy been allowed to form any sort of front along the opposite bank of the canal, they would have swept across the water in strength. From the very beginning the Irish marksmen held the upper hand over their German counterparts by dispersing any attempts to cross the narrow stretch of water that divided the two sides:

‘Having learned nothing yesterday our assailants were still periodically trying to cross the main street [of Beuvry] and other open ground in small groups. Mostly out of view of 17 [Platoon], 18’s men were still able to fire straight down it and engaged them every time they tried it. After a while a sizeable detachment tried rushing across together, and most of them went down under the storm of fire which greeted them the instant they broke cover – though I doubt all of them were hit.’4

In the early hours of the 26th the 1/8 Lancashire Fusiliers, described by Gough as a ‘stout-hearted but inexperienced battalion’, began their relief of the battalion and, through no fault of their own, were thrown into an already deteriorating situation. Moving forward under severe shellfire the Irish Fusiliers disengaged and headed north towards la Croix Rouge.

At Pont-à-Vendin on the Deûle Canal – 10 miles to the southeast – Lieutenant Anthony Irwin and the 2/Essex were holding a 4½ mile sector from Salome to Estevelles. Irwin and 11 Platoon were at Pont-à-Vendin where the road bridge was blown on 24 May, an event which Irwin described as a source of great relief to all concerned: ‘Once the bridge had gone up the constant flow of refugees would have to go elsewhere to cross the canal.’ In the meantime they had the problem of barges to contend with but, as the canal was somewhat deeper than it was around Béthune, simply towing them midstream and sinking them appeared to do the trick. Apart from the occasional skirmish with German advanced units and bombing raids from twin-engined Dorniers, enemy activity on C Company’s sector didn’t, according to Irwin, ‘begin to get interesting’ until 24 May:

‘Suddenly there was a burst of fire from my left-hand section. I raced down to see what was happening, and was just in time to see a Hun motorcycle combination go head-over-heels into the canal, with its crew of three all dead. Another was turning in the road when a shot from the anti-tank rifle knocked the engine out and into the lap of the man sitting in the sidecar. The other two leapt off and ran into the wood, dragging their pal with them. A third vehicle stopped in the corner and got a machine gun into action against us in double quick time. A long burst of bullets hit the wall by my head, and I got down quick. Then came the shot of the century. It was our anti-tank man again. With one shot he hit the gunner and knocked his head clean off his shoulders.’5

From across the canal they could hear the Germans ‘crashing about in the wood’ and put in a long burst of Bren gun fire to encourage them to run faster. On the road lay the wrecked motorcycles and a machine gun:

‘I shouted for volunteers and Barnes and Fox, two old soldiers with pretty grubby crime sheets and hearts of lions, ran up. We hopped into a small boat and rowed across the canal. We had a quick look into the wood but the Hun seemed to have fled. Fox then ran for the machine gun and I got some maps out of the motorcycle and a couple of boxes of ammunition; we rowed back like hell with the booty.’6

No sooner had they scrambled up the side of the canal when a German tank appeared on the far side and began blazing away at Irwin’s platoon. ‘Bullets at the rate of a thousand a minute plopped, skidded and screamed at our feet. Stewart behind the anti-tank rifle was shooting like a man possessed.’ The tank then retired only to reappear pushing an anti-tank gun into position which opened fire at the very same moment as Stewart – the German gunner missed his target, smashing the brickwork behind Irvine, but Stewart’s round went ‘straight through the shield, hit the gunner and threw him spread-eagled onto the top of the tank’. Twenty rounds were put into the tank which according to Irvine ‘looked like a colander by the time we had finished’.

When Irwin’s MC was announced in October 1940 the regiment made much of the fact that not only was the young subaltern commanding the same platoon as his father had 25 years earlier, but also that the decoration was the first to be awarded to the Essex Regiment. Many more were to follow over the next five years. Anthony Irwin’s father was 48-year-old Brigadier Noel Irwin, then commanding the 2nd Division, who by way of coincidence, had also been the first officer in the regiment to receive the MC in the previous conflict.

The Essex were relieved on 25 May by 2/5 Leicestershire, a Territorial battalion that had arrived in France during April 1940 with 139 Brigade for labouring and construction work. Now with Polforce, desperation had forced the transformation of Lieutenant Colonel Ken Ruddle’s men from a labour battalion to a front line fighting force in the space of less than a fortnight! Faced by units of the German 12th Infantry Division the outcome was inevitable, and over the next 36 hours the Leicesters bravely defended their sector of canal before being overwhelmed, the survivors breaking out toward Dunkirk leaving their dead behind.

As was becoming apparent, German forces along the Canal Line were consolidating and in some areas, such as St Omer, were enlarging their bridgeheads. The reason why there was no determined assault on the BEF positions is explained by the Halt Order of 24 May. Although its architect was von Rundstedt, German armour was halted on the Canal Line by a directive signed by Adolf Hitler. Von Rundstedt’s application of the brakes on the panzer columns was almost certainly necessary as far as rest and refit was concerned but, more importantly, it prevented the complete defeat of the BEF by reducing what could have been an overall strategic victory into a more localized tactical victory. While German High Command certainly underestimated the Royal Navy’s capability to evacuate the BEF, the Halt Order was perhaps the result of a lack of cohesion and the internal struggles that existed between Hitler and his generals. But whatever the reasons behind the order it was a mistake and, as events turned out, proved to be a very costly one.

Yet, despite the Halt Order remaining in force until 3.30pm on Sunday 26 May, there were at least two enemy incursions authorized on 24 May. Guderian sanctioned Sepp Dietrich’s SS Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler Regiment to cross the canal at Watten to take the high ground to the east and he probably knew of the SS Verfügungs Division’s incursion between Thiennes and Robecq in the Polforce sector. Whether the orders for the Verfügungs assault were issued before the Halt Order is open to conjecture but the French units which had been holding the canal came under a furious attack early that morning. German infantry accompanied by motorcycles and armoured cars engaged the French 401/Pioneers Regiment and the sappers of 315/Bridging Regiment from the 5th Motorised Division. Short of ammunition the French units withdrew, leaving a gap in the line which the Germans were quick to exploit. Three battalions of the SS Germania Regiment were ordered across the canal at Robecq, Busnes and Guarbecque to move on St Venant, a small town which lay two miles north on the canalised River Lys – often referred to as the Bourne Canal in regimental histories.

Having thrown temporary bridges over the canal the 15/Motorcycle Company commanded by Hauptsturmführer Mulhenkamp set out for Robecq, whilst other detachments of the SS headed westwards towards St Venant. Horst Kallmeyer and 7 Kompanie of the SS Germania Regiment most likely crossed the canal over the ruined l’Epinette bridge:

‘Our group is the lead company and advances forward making our way across the damaged bridge across the canal, which in places was below the water line. On the other side we advance forward. We receive gun fire. The groups go behind houses to take cover. I am selected as a battlefield observer and get the field glasses of Lengemann. At a fork in the road I lie down in a ditch and observe. We wait for other companies and anti-tank guns to move up to the canal. On the street about 800–1000m on the left, enemy motorized columns withdraw. From the first houses in Saint Venant in front of our position we received some gun fire. [We] fire back. Finally, as we advance further, the gun fire continues, some wounded of our anti-tank are brought back by motorbike. When we finally enter the first houses in Saint Venant we find that the Tommies have gone but left their baggage and ammunition behind.’7

At 12.30am the remaining troops in Robecq – including the 2/5 West Yorkshires who we first met briefly in Chapter 4 – had withdrawn towards Calonne-sur-la-Lys via the Bois du Pacaut. In St Venant 9 Compagnie of the French 401/Pioneer Regiment were surrounded on the edge of the village and almost completely wiped out.

There is an alarming entry in Kallmeyer’s diary which betrays an underlying brutality then prevalent amongst some SS soldiers:

‘We advanced on the left along Saint Venant. A slightly wounded Tommy stands up in his trench with his arms in the air. The horror and the fear are reflected in his face. Unfortunately [two men] over reacted and hit the Tommy in the face with a grenade.’8

Although difficult to pinpoint, this act of barbarism could well have taken place at St Venant where B Company of the 6/King’s Own Royal Regiment ambushed Kallmeyer’s company before withdrawing to Merville, but wherever it took place, it was symptopmatic of the utter disregard for the welfare of prisoners that was to surface again over the coming days.

The loss of St Venant and Robecq now involved the 2nd Division and it is worth noting that the withdrawal of the SS Verfügungs back to the canal was not driven by the Halt Order but by the 1/Royal Welch Fusiliers from 6 Brigade. Their task – to recapture the four bridges over the canal near Robecq – was a tall order for any battalion to undertake, but for a severely under-strength unit with little or no fire support it was all but impossible. The first attempt to take the bridges was made on the evening of 24 May. C Company was detailed to take the l’Epinette Bridge and B Company the two bridges at Robecq. Lieutenant Robin Boyle and D Company took the direct route to the Blackfriars Bridge on the present day D937 down the Calonne – Robecq Road. Leading the way was 16 Platoon with 17 and 18 Platoons checking the buildings on either side of the road for signs of the enemy. Just before Robecq the company was ambushed and in the ensuing fire fight the 24-year-old Boyle was killed before the survivors managed to disengage and withdraw.

As darkness fell 43-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Herbert ‘Harry’ Harrison had no clear idea of exactly where all his companies were and without maps or information concerning the strength of enemy forces, any further attempts to reach the canal seemed inadvisable. Withdrawing his companies around St Floris for the night, Harrison suspended operations until dawn on 25 May. Continuing the advance early the next morning St Venant was cleared by A and C Companies but they were subsequently held up just south of the hospital on the D916 where they dug in. Captain James Johnson and B Company fought their way into Robecq but heavy machine-gun fire prevented them from reaching the bridge. Intent on holding on to their positions, Johnson began fortifying the village, discovering too late that the enemy had worked round behind him and surrounded the company. Whether they expected to be relieved or not there was little the Fusiliers could do that evening apart from strengthen their defensive positions around the brewery at the intersection of the Calonne and St Venant roads. Johnson was wounded that evening and command devolved to Second Lieutenant Michael Edwards.

Apparently unaware of the situation in which the Royal Welch had become embroiled, Brigadier Dennis Furlong, commanding 6 Brigade, ordered the 1/Royal Berkshires to seize the bridges over the Aire at Guarbecque on 24 May to protect the western side of the corridor to Dunkirk, a task they were told would be relatively straightforward. Lieutenant Colonel Geoffrey Bull’s suspicions that all was not as it appeared were first raised by an artillery barrage which greeted his battalion’s exit from St Venant and then by heavy machine-gun fire as it advanced towards Guarbecque on the D186. Without artillery support and unsure of the strength of enemy forces ahead of him, Bull sensibly withdrew the battalion around Bas Hamel placing C Company in reserve across the canal at Haverskerque.

Captain Cyril Townsend’s diary for Saturday 25 May 1940 tells us the 2/DLI left Calonne in companies and marched by separate routes to occupy the line of the railway that ran through St Venant. Regardless of which company a soldier had fought with on the Dyle, the surviving men of the Durhams were by now marching in four amalgamated companies, a situation that was not improved by the temporary loss of two companies a week earlier near Overyssche. The war diary does not record a further reorganization but it is likely there was some further redistribution of men on the mistaken assumption the two missing companies had been overwhelmed by the enemy. All of which may account for Lieutenant Michael Farr writing in his diary, ‘To say we were a bewildered bunch of men would be to put it lightly.’

Meanwhile Harrison had established his headquarters near the railway station at St Venant and leaving Captain Willes, the battalion Intelligence Officer, to collect and redirect men to their new positions, he set off with his adjutant to establish contact with Lieutenant Colonel Simpson. The Welch line ran along the road running south of the railway from the level crossing to the crossroads at the eastern end of the embankment and covered the bridge over the canal where they were in touch with the Durhams. Simpson, concerned at the gap between the Berkshires and the town, deployed D Company with Lieutenant John Gregson on the right flank and the remaining three companies along the railway line between the Robecq and Les Amuzoires road. Establishing his headquarters in the Taverne farmhouse near the canal, he managed to place the battalion transport under cover in one of the barns. The left flank, like that on the right, appeared to be wide open and it was this flank that would ultimately seal the fate of many of those at St Venant.

The brigade was supported by the ever faithful 44/Battery from 13/Anti-Tank Regiment and 226/Battery from 57/Anti-Tank Regiment who had been detached from the 44th Division, together with a battery of guns from 99 (Buckinghamshire Yeomanry) Field Regiment. Still with the brigade was Captain George Frampton and the machine guns of C Company, 2/Manchesters, that had fought with them on the Dyle and Escaut.

As night fell on St Venant the surrounded Welshmen at Robecq could only listen to the movement of enemy forces crossing the canal and await the onslaught that would come the next morning. It began at 7.30am with a barrage of artillery and mortar fire which preceded the 1/IR 3 attack along the Eclème road. Infanterist Hofmann and his company were waiting to advance once the guns had ceased firing:

‘At 7.30am exactly our artillery began firing on Robecq. Houses burst into flames as they were hit; the grey skies above were traced with red light. However our artillery had little effect and nothing moved in the area; even after 300 rounds the nervous silence hung over the rooftops ... We approached the village, our commander leading the way. We had just passed the first houses and we still had not heard a single shot. The road seemed deserted and with each step we took the silence seemed to deepen. The crossroads loomed in front of us; there was the cemetery. It was at this moment that a heavy weight of fire rained down from the surrounding houses.’9

Slowly B Company were driven back into a continually contracting perimeter but with flat ground all around there was little chance of a break-out succeeding in daylight. Edwards split the remaining men of the company into small groups and ordered them to attempt to get back under cover of darkness. But it was not to be. The regimental historian concludes his description of B Company’s stand with the words ‘At 11.00am B Company, as a company, ceased to exist.’ Edwards was taken prisoner along with the majority of the survivors while Johnson, with a bullet wound in the neck and back, was taken to the former English hospital at Camiers from where he eventually made a successful escape over the Pyrenees to Spain.

Quite why Brigadier Furlong deployed 6 Brigade south of the Lys Canal at St Venant is anyone’s guess but it proved to be an error which contributed significantly to the destruction of the two battalions there. It was a decision made even more questionable by his refusal to grant Harrison’s request to withdraw north of the canal on 26 May. His award of the DSO for his command of 6 Brigade specifically mentions the 48 hours of the St Venant defence, ‘not withstanding the very heavy casualties they suffered’. Furlong was killed on the Yorkshire coast on 5 September 1940 whilst inspecting a mine field.

The German assault on 6 Brigade began at around 7.00am on 27 May under the overall command of Oberst Ulrich Kleemann who moved across the La Bassée Canal with three battalions of infantry, a battery of guns from FAR 75 and elements of the SS Germania Regiment. Kleemann’s infantry assault was announced by a heavy artillery bombardment which, noted a delighted Michael Farr, did not prevent the combined fire of the Welch and Durham riflemen mowing [them] ‘down like ninepins’. His euphoria was short-lived: the heavy growl of tanks of the 3rd Panzer Division could be heard behind the infantry swaying the battle in the Germans’ favour. It was the beginning of the end. Cyril Townsend’s diary again:

‘Heavy mortar fire and possibly artillery fire was put down on our company positions. The church spire was hit and movement in the village was difficult and dangerous. The enemy was moving across our front to the left. About 15 tanks could be seen from battalion HQ. Our artillery opened fire but later ceased firing.’10

D Company – with its headquarters at the junction of the Ruelle Berthelotte and Rue d’Aire – was on the western edge of St Venant positioned just south of the Rue d’Aire with the Guarbecque Canal to their front. Having been joined by Sergeant Martin McLane and some of his men from the Mortar Platoon they were on the extreme right flank of the battalion with no contact between themselves and the Royal Berkshires. The previous day enemy artillery fire had claimed the life of 24-year-old John Gregson who was hit with ‘a bowl-sized piece of shrapnel’ which lodged in the base of his spine, leaving command of the company to CSM Norman Metcalf.

The events of 27 May on the D Company front are largely confined to those few accounts that have survived the ravages of time. Once the tanks moved in the company was heavily engaged but without heavy weapons their struggle against armoured vehicles became futile. Inevitably, as their resistance collapsed, the fighting became fractured with small groups of men defending their own piece of ground. Private Dusty Miller, who was still with his mate George Blackburn, was in front of a privet hedge near a farm. ‘We could hear shots going through the hedge, like the sound of bees; we were pinned down and couldn’t do anything’.11

In St Venant the story was much the same. The Royal Welch lost heavily as their much depleted companies came up against enemy armour. A Company, which had already been reduced to two platoons, was soon overwhelmed after being completely surrounded. Twenty-nine-year-old Captain Edward Parker-Jervis commanding C Company, was killed defending a house which had been surrounded and D Company, under Second Lieutenant Kemp, could only muster fifteen men after they retired towards the canal in the face of several German tanks with PSM Jenkins being pushed along in a wheelbarrow.

Nevertheless, with 6 Brigade contesting every inch of ground, enemy units were finding the British defence hard to overcome. Men of 8 Kompanie II/IR 3 found the advance up the Busnes road to be painfully slow as they moved from house to house, losing Leutnant Wallenburg as they reached the railway line. Also taking heavy casualties was 7 Kompanie which reached the water tower by the station under a hail of fire:

‘Leutnant von Bismark was fatally wounded in this attempt. He was quickly taken to a field hospital but was dead on arrival. The company engaged the enemy in the town and a street battle raged, fought across the ruins and debris of burning houses ... During this time Major Zimmermann set up his battalion HQ in the hospital and 6 Kompanie managed to reach the town, in so doing they suffered casualties at the hands of a few isolated machine gunners.’12

Forced back onto the Lys Canal, a runner arrived at at Simpson’s DLI headquarters at Taverne’s Farm with a message from Lieutenant Colonel Harrison who had by this time moved his Royal Welch HQ to the communal cemetery. Cyril Townsend, not knowing exactly where his CO was, made the perilous journey along the canal bank where Harrison told him of his intention to hold the canal bridge to enable the survivors to get across:

‘I crawled back to see Colonel Harrison. He said the position was untenable and that he was taking what men he could to form a bridgehead. I was to bring back any men I could. I sent Lyster-Todd and some men back at once and crawled forward to find CSM Birkitt and Private Worthy, the C Company runner. By this time armoured cars had almost reached the café and although I waved to the men inside, I realized they could no more come out than I could go to them across open space.’13

The bridge over the canal was the only exit available but for Simpson and the men at the Durhams’ headquarters it was a bridge too far. Harrison’s move to the canal crossing was in response to Brigadier Furlong’s orders to retire, but there is some discussion as to what time Furlong actually arrived. The account in Y Ddraig Gogh says 9.15am, Townsend’s diary declared Furlong arrived at 11.00am with orders for the brigade to retire but Michael Farr was quite sure that no orders for retirement arrived at the Durhams’ headquarters at Taverne’s Farm. He may of course have been too occupied with the severity of the fighting to notice the arrival of anything other than German armour:

‘I saw the position getting more and more serious. The Boche had infiltrated around the left flank, snipers had crossed the canal and the bastards were shooting our soldiers in the back. Meanwhile huge and ugly tanks were bearing down upon us. Our one and only anti-tank gun was destroyed. The men were driven to the edge of the river bank; they had nowhere to go but backwards into the water.’14

The Durhams’ last stand by the canal was made at the barn, which by now was under fire and in flames with Simpson defiantly firing his pistol at German tanks which were advancing up the Les Amuzoires road. Enemy units had also got in behind them after advancing up the undefended left flank. Surrounded, the British threw down their weapons and surrendered.

After Cyril Townsend had left the RWF Headquarters, Captain Walter Clough-Taylor was instructed by Harrison to form a defensive flank by the bridge, but first they had to run the gauntlet of enemy fire to get there:

‘I saw many men stagger and fall as they ran. Martin, my trusty servant, had his arm blown off. Then it was my turn. I summoned courage, waited for a burst of fire and dashed forward. I was only a yard or so on to the bridge when I was hit in the leg, I recoiled and staggered crazily back to the culvert. As I stood thinking wildly how I was going to get across alive, I noticed there were girders rising to about a foot in height in the centre, above the roadway ... I got up and was at once hit again in the arm and hip, I staggered on to the shelter of some houses.’15

Clough-Taylor was taken prisoner but fortunately a few of the Durhams did manage to get across the bridge with Townsend who was shot through the face as he reached the other side. He remembered a Welshman putting a field dressing on the wound before he managed to walk away under more machine-gun fire. He describes the final moments at the bridge:

‘When Colonel Harrison saw that no one else could get across the bridge owing to the close proximity of the leading tanks, which by this time were only 150 yards away, he ordered the Royal Engineers to blow [it] unfortunately there were none available. The situation then became impossible as there were perhaps twenty men holding the bridge with only one Bren gun and no anti-tank rifle against at least five tanks. The leading tank came across the bridge and wiped out most of the men holding it.’16

The leading German tank hesitated before crossing the bridge and bringing its fire to bear on the cottages ahead. Harrison was killed ‘in the last flurry of fighting while attempting to delay the crossing’ and those that could began making their way north towards Haverskerque where 6 Brigade Headquarters was situated.

The surviving men of D Company were also heading for the Lys Canal. Dusty Miller remembers there were tanks approaching when he heard the order from Martin McLane to make for the canal:

‘We started running across a field, I did not know there was a canal there, I don’t think any of the other lads knew there was a canal ... As we were running, George was behind me and I heard him shout ‘Jim, Jim’, so I stopped and George was lying on his back, he had been hit in the legs I think, I ran back towards him and I saw a young officer running towards me and he shouted ‘keep going, keep going’ and I had to leave George.’17

The sacrifice of the two 6 Brigade battalions at St Venant was an almost inevitable conclusion from the moment they took up position along the railway line. The Berkshires, although attacked at dawn on 27 May, did manage ‘a discreet battalion withdrawal, under heavy fire’ to new positions behind the Lys Canal but there are still over twenty identified men buried locally. That evening only 212 officers and men answered their names at roll call. The casualty list for the St Venant defenders was significantly greater as the CWGC cemeteries in the area bear witness. In the St Venant Communal Cemetery there are over 120 identified men who were killed in the action including Captain Edward Parker-Jervis. Lieutenant Colonel Harrison and a further ten men lie in the Haverskerque Churchyard and the Robecq Communal Cemetery contains the Fusiliers of B and D Company. This number does not take into account the unidentified dead – whose names appear on the Dunkirk Memorial – the wounded and those taken prisoner.

Yet, there is a darker side to the casualty lists that first came to light when the dead at St Venant were reinterred from the mass grave they had originally been buried in. Post mortem files indicated that in a number of cases there were impact blows to the skull which could only have been inflicted at close range. The testimony from the local population and from survivors, point to units of the SS Germania Regiment being responsible for the shooting and bayoneting of British prisoners to the west of the town after they had surrendered. In the subsequent inquiry the Judge Advocate’s Office initially found that six prisoners had been executed in this manner and although the perpetrators were identified as SS soldiers from the Germania Regiment their names remain unknown. In addition there is also a body of evidence that suggests other war crimes against wounded and captured British soldiers in the vicinity did take place, although to date no confirmation has surfaced in the public domain. There may still be MI19 documents which are still classified and unavailable for public scrutiny and until these files – if they exist – are examined, the full story of the St Venant murders will remain untold.18

Along with the 1/8 Lancashire Fusiliers and the 2/Norfolks, the 1/Royal Scots were withdrawn from the Escaut at midnight on 22 May and ordered to relieve the 25 Brigade units along the La Bassée Canal. The Norfolks were now under the command of their third commanding officer, 37-year-old Major Lisle Ryder, who had taken charge after his predecessor had been wounded on the Escaut. Lisle Ryder was the brother of Robert Dudley Ryder who, as a Commander RN, led the raid on St Nazaire in 1942 resulting in his award of the VC. Even before the battalion arrived on the canal to take up their allotted sector between the Bois Pacault and the bridge at Béthune, two companies of Norfolks had inadvertently deployed to a subsidiary loop in the canal, leaving a large gap on the left flank and no doubt increasing Ryder’s unease.

Although the wayward companies were back in place twenty-four hours later the Pioneer Section from HQ Company had been pushed into the gap by Ryder and told to make every round count. Private Ernie Farrow and his mates found that by using rifle fire instead of the more ‘ammunition hungry’ Bren gun they were able to conserve on ammunition and bluff the Germans into thinking ‘there was a great company of us there’. To Farrow’s amazement they managed to hold off the German assault until B and D Companies finally turned up. That evening Ryder withdrew his headquarters to Druries Farm on the Chemin de Paradis about 500 yards west of the Paradis crossroads where Farrow and the surviving pioneers rejoined. The scene that confronted him was shocking:

‘I ran into this cow shed and was amazed to see all my comrades lying about, some of them had lost a foot, some an arm, they were laying about everywhere, being tended by the bandsmen who were all first aid men. The first thing I wanted was a cigarette, I wanted a fag. I was dying! I’d never smoked a lot but this time to save my nerves I found someone who had some fags, and I just smoked my head off.’19

Overnight on 26 May German forces, including the SS Totenkopf Division, moved up the south bank of the La Bassée Canal in preparation for an assault on British forces the next morning. Temporary pontoon bridges were quickly put across the water to enable armoured vehicles to cross. Advancing with the 2nd SS Battalion, Herbert Brunnegger and 3 Kompanie crossed the ruins of the bridge at Pont Supplie where he came across his first wounded British soldier:

‘His face is distinctive and brown but the proximity of death is making his skin go pale. He is standing up and leaning against a wall made of earth. In his eyes there is an indescribably hopeless expression while the whole time bright spurts of blood are coming out of a wound at the base of his neck. In vain his hands try to press on a vein in order to try and keep the life in his body. He cannot be saved.’20

The fierce fighting around Le Cornet Malo – which was held by the Norfolks – slowed the SS advance considerably although Private Arthur Brough, who was with the B Company Mortar Platoon, considered it was getting a bit hectic:

‘Lots of tanks and heavy gunfire. We were putting as much stuff down the mortar as we could. We were trying to repulse them but we knew it wasn’t a lot of good because there were so many there ... The mortar must have been red hot, anything we could get hold of we were putting down the mortar until it got so bad that we even resorted to rifles.’21

There were only three of the platoon left standing when Brough and his mates resorted to firing their rifles at the approaching enemy which they continued to do until the arrival of enemy tanks, at which point he confesses they ‘just ran for it’.

The actual detail of the fighting remains obscure but we do know from the various war diaries that with the aid of several counter-attacks and with assistance from the Royal Scots, a fragile equilibrium was restored by nightfall with the Germans in occupation of Riez du Vinage and the Bois Pacault. But there had been heavy casualties on both sides and only about sixty men of A and B Companies of the Norfolks remained capable of fighting leaving Lieutenant Murray-Brown wondering just how long they would be able to ‘hold the position to the last man and the last round’. It was, he thought, getting a little desperate.

The attack continued at 3.00am the next morning with German forces emerging from the shelter of the Bois Pacault. Brunnegger and his Kompanie moved slowly towards Le Cornet Malo:

‘The attack is renewed. A weak sun is rising out of the ground mist. A signpost points to Le Cornet Malo. Mortars and sub-machine guns move into position on the edge of the wood and fire at recognizable targets in a village a couple of hundred metres in front of us. While they do this our soldiers move forward on both sides of the path ... Onwards! A surprise as bursts of machine-gun fire hit a section as it moves out of a cutting. The bursts toss them into a tangle of bodies. One stands up and sways past me to the rear – he has a finger stuck into a hole in his stomach.’22

If Brunnegger thought for a moment that the fight for Le Cornet Malo would be relatively easy, his confidence was to be rudely shattered by the dogged defence of the Norfolks and C Company of the Royal Scots:

‘The English defend themselves with incredible bravery ... we are completely pinned to the ground in front of the enemy who are totally invisible and whose ability commands our admiration. We have to adapt ourselves completely to the enemy’s tactics. We work ourselves forward by creeping, crawling and slithering along. The enemy retreat skilfully without showing themselves.’23

However, overwhelmed by the sheer number of German soldiers and their supporting artillery, and with the village in flames, the survivors were slowly pushed back on Paradis.

A Company of the Royal Scots, having now moved east, was in position three-quarters of a mile south east of le Cornet Malo astride the present day D945 Merville road when they beat off a strong German force heading north from the canal. During the fighting Major Butcher was badly wounded but continued to be carried around on the broad back of CSM Johnstone until the arrival of Harold Money who sent him up to the RAP in Paradis. In the subsequent fighting both of the remaining subalterns were either killed or captured leaving Johnstone to maintain their hold on the farm buildings they had by now fortified:

‘The Jocks did their best to turn the place into a strongpoint, blocking windows with tables and chairs and piling grain bags filled with earth in the gateway. Here they were prepared to make a last stand. Everyone realized that there must be no relinquishing a position from which they could deny the enemy passage up this important road.’24

The Scots headquarters at Paradis was in a farm complex on the Rue de Derrière with the RAP nearby, along the same road but closer to the village, was Major Watson’s D Company Headquarters. Realizing a strong attack up the Merville road was forthcoming, Money pulled the remains of Captain Mackinnon and B Company – which up until this point, had been deployed along the Rue de Cerisiers – back into the village. Further south A Company had beaten off several enemy attacks before Captain Nick Hallet of the Norfolks arrived from the direction of le Cornet Malo and ordered Johnstone to withdraw but it was too late. Caught trying to escape along a ditch, the surviving men surrendered and Johnstone – accused of ‘gouging out the eyes of dead German soldiers with his jack-knife’ – was led into a field along with his companions to be shot. ‘By a piece of good luck a staff officer in this division happened to come along in a car. He spoke to me in English and it was he who saved us from being shot.’25

At Paradis, Harold Money was wounded and sent off to the La Gorge dressing-station which was the very spot he had been taken to in May 1915 after he had been wounded in the First World War. The end of the battalion’s stand arrived with a ferocious German attack which shattered the buildings of the village. Lance Corporal James Howe was in the Royal Scots’ RAP at Paradis when SS troops first appeared:

‘We were with the Royal Norfolks; they had one end of the village and we had the other ... We were about fifty yards from the centre of the village. We were in this house tending our wounded in the RAP, with the medical officer and the padre with about six of us attendants, and maybe twenty wounded ... the first thing I saw was a hand preparing to throw a hand grenade through the window of our aid post. This hand grenade came in, blew up and we all dived into the corner. Of course the building caught fire so we had no option but to get out as quickly as we could.’26

In a horrifying episode witnessed by Howe, a German NCO announced his intention to shoot the wounded Scots. Challenged by Padre McLean and the Medical Officer, the NCO attempted to justify himself by saying the British had been using dum-dum bullets. It was only the intervention of those present that prevented the murder of wounded men. Whether or not any of the remaining Royal Scots were executed after they had surrendered is still open to conjecture but there are reports in the various Paradis War Crimes files of men with similar wounds to the back of their heads being discovered in mass graves and another detailing evidence from a local Frenchwoman of the apparent execution of seventeen Royal Scots found hiding in a hayloft. We will probably never know the truth of exactly what occurred on that afternoon in May 1940.27

At Druries Farm the perimeter defences were slowly being taken out by enemy machine-gun sections. Signaller Robert Brown was in the farmhouse when Major Ryder gave the men the option of surrendering or trying to escape. By sheer luck Brown and two others made the decision to leave the building by a door leading onto the road:

‘The smoke from the burning house was going that way so we thought we’d keep in the smoke as extra cover in the hopes of getting away. We went in a ditch at the side of the road and in the ditch was the adjutant [Captain Charles Long], lying on the ground wounded and the medical officer was there. We attempted to go out of the ditch and cross the road but as we did so the German patrols were coming up from the village of Paradis and we couldn’t get over.’28

Druries Farm represented the boundary between the Norfolks and the Royal Scots and the location of the farm on Chemin du Paradis goes some way to explaining the tragic events that followed Ryder’s surrender of HQ Company. The farm was attacked by Brunnegger’s 2nd Battalion and Brown’s decision to leave by the door facing the road undoubtedly saved his life as he was taken prisoner by another unit moving up from the village. Ryder and the remaining men left through the stable door leading to the fields at the rear of the farm. Their fate was now in the hands of of Hauptsturmführer Fritz Knoechlein’s men.

What happened next as Ryder and the men of Headquarters Company were marched up the road to Louis Creton’s farm will always rank as one of the most appalling atrocities committed during the 1940 campaign in France. Signaller Albert Pooley was one of the men who had surrendered with Ryder:

‘There were a hundred of us prisoners marching in column of threes. We turned off the dusty French road through a gateway and into a meadow beside the buildings of a farm. I saw, with one of the nastiest feelings I’ve ever had in my life, two heavy machine guns inside the meadow. They were manned and pointing at the head of our column.’29

Herbert Brunnegger was at the farm when he saw the column of prisoners by the barn:

‘Many of them reach out in despair towards me with pictures of their families ... As I look more closely I notice two heavy machine guns which have been set up in front of them. Whilst I look on, surprised that two valuable machine guns should be used to guard prisoners, a dreadful thought occurs to me. I turn to the nearest machine-gun post and ask what is going on here. ‘They are to be shot!’ is the embarrassed answer.’30

Brunnegger’s account goes on to say that he understood the orders for the prisoners to be shot had been given by Knoechlein. It is difficult to say exactly what we would do in Brunnegger’s place, as it was he writes that he chose to leave the scene in order not to witness the murder of prisoners, but he must have heard the cries of the Norfolks as they were cut down by the barn wall. Albert Pooley wrote afterwards that he felt an icy hand grip his stomach as the guns opened fire on them:

‘For a few seconds the cries and shrieks of our stricken men drowned the crackling of the guns. Men fell like grass before a scythe. The invisible blade came nearer and then swept through me. I felt a searing pain in my left leg and wrist and pitched forward in a red world of tearing agony ... but even as I fell forward into a heap of dying men the thought stabbed my brain, ‘If I ever get out of here the swine who did this will pay for it.’31

Pooley did have his revenge and Knoechlein was brought to trial in 1948 where his defence claimed the British had used soft-nosed dum-dum bullets and had misused a white flag of truce, all of which were denied by the prosecution team. But some of the most damming evidence was given by Albert Pooley and the other survivor of the massacre, William O’Callaghan, all of which resulted in Knoechlein’s conviction and sentencing – death by hanging – which was carried out in January 1949.

The Royal Scots’ D Company made their last stand at a farm north of Paradis where Major Watson was killed and James Bruce – now in command – held out long enough to allow him and a handful of men to escape. Sadly they were captured near the Merville airfield 24 hours later.

The dead of the Paradis massacre were exhumed from their mass grave in 1942 and moved to the Paradis War Cemetery where they now lie with the other casualties from 4 Brigade who were killed in that desperate engagement. Both battalions were practically annihilated, only five officers and ninety men of the Royal Scots and three officers and sixty-nine other ranks from the Norfolks eventually making it home via Dunkirk

North of the Lys Canal lay the expansive Forêt de Nieppe which was the direction in which Private Dusty Miller and Sergeant Martin McLane were running after enemy tanks had overwhelmed D Company of the 2/DLI at St Venant. The shots that felled George Blackburn south of the Lys Canal had, unbeknown to Miller, also wounded him in the shoulder and having been told to wait for an ambulance in a nearby barn he found himself completely alone:

‘I came out of the barn and I did not know where I was, what I should do, where I should go so I just kept walking. I must have been walking northwest because I got into a forest ... There was a battalion standing there behind trees with their bayonets fixed and I said what regiment are you and a young lad said “The West Kents, 4th Battalion”.’32

If Miller is correct then he was walking in the direction of Morbecque when he was picked up by a truck belonging to an artillery unit which was subsequently hit by Stukas. ‘The driver must have been hit and the truck tipped over and I got flung out.’ The next thing he was aware of were German soldiers all around him; the truck had gone as had the artillery unit:

‘I don’t know what the Germans thought of me sitting there with a sleeve off and no equipment. Then this German, he was yelling at me, he was a big paratrooper, I was scared, I was really frightened, he pulled me up and he was shouting at me, I was looking all over the place and as I turned he hit me, I don’t know what he hit me with and down I went ... the soldier had hit me pretty hard, he had mashed my face up, he had knocked some teeth out and knocked half my eyebrow off.’33

Miller had more than likely been hit with a stick grenade being used as a club, an attack that bore a remarkable resemblance to the one described by Horst Kallmeyer at St Venant three days earlier. His reference to ‘a big paratrooper’ may have been influenced by the camouflaged smocks and helmet covers in use by SS troops as there were certainly no parachute troops in the area at the time. What is even more interesting is that according to Kallmeyer’s diary, units of the SS Germania Regiment were in the Morbecque area on 27 May, leaving one to wonder if the violent attack on Miller was carried out by the same unit.

Despite Dusty Miller’s confused state, his reference to the 4/RWK was correct as on 26 May the 4 and 5/RWK had moved to the western edge of the Forêt de Nieppe where D Company at Morbecque came under attack from German tanks. At dawn the next morning the 4/RWK were somewhere along the line running from Croix Mairesse to the Canal de la Nieppe which is where Miller ran into them that afternoon. Corporal Bertie Bell, who was serving in B Company, 4/ RWK, remembers being sent to Morbecque to engage three tanks:

‘After some fighting B Company was forced to fall back to the position on the [Hazebrouck] canal held by the battalion. From this position, after fighting involving heavy casualties, the battalion retired. Later a new position was formed along a forest path running north and south near the east end of the forest. A small group of five men and a corporal, commanded by me, was on the left or southern end of this new position.’34

From all accounts it seems that the RWKs inflicted heavy casualties on the SS units opposing them, which may go some way to explain the treatment inflicted on Bell’s section. Finding themselves cut off from the battalion, Bell’s men came under fire again when Privates Henry Daniels and Fred Carter were wounded. Fortunately they found a barn where they sought shelter for the night. Early the next morning they were discovered by German troops and marched off into the forest:

‘I had heard tales of prisoners being shot in Norway and feared the worst, especially as almost immediately we came upon a section of about six German soldiers lying down parallel to our line of march and facing in our direction with rifles laid out in front of them as though in readiness for action ... When we had proceeded a few steps further the officer who was marching on the left of the parade with drawn revolver gave an order whereupon the rear gunner opened fire without warning and shot down my comrades. I was on the alert and threw myself down unwounded immediately I heard the first shot. I lay perfectly still and held my breath. A few seconds later there were three revolver shots. I then heard the Germans walk away. Remaining in my position for some five minutes more, I got up and looked at my comrades. I saw that one revolver shot had been fired at Private Shilling and blown half his head off. The other two shots appeared to have been aimed at Private Daniels who was shot in both eyes. He was lying on his back with his face to the sky. They were all beyond human aid. I had to move away quickly on account of returning Germans.’35

Evidence given by Bell in 1943 after his escape across the Pyrenees to Gibraltar pointed firmly to the SS Der Fuhrer Regiment being responsible for the murders, which is supported to an extent by the movements of the 3rd Panzer Division. There is differing opinion on the movements of the SS Verfügungs Division on 27/28 May, nevertheless, what is certain is the Der Fuhrer Regiment, together with Germania and Deutschland, crossed the La Bassée Canal on 27 May. Deutschland and, very possibly Der Fuhrer, were part of the right hand column of the 3rd Panzer Division under the command of Generalleutnant Horst Stumpff. Germania we know was further west and Deutschland was across to the east around Bailleul, leaving Der Fuhrer operating in the Merville area and the eastern side of the Forêt de Nieppe.

While the West Kents were fighting in the Forêt de Nieppe the 2/Dorsets were under orders to cover the movement of 5 Brigade by holding Festubert. The battalion had taken over a three mile sector along canal line on 25 May running from Gorre to Pont Fixe at Cuinchy and were very conscious that they were now fighting over the same ground the 1st Battalion had fought on during October 1914 twenty-six years previously. The battalion was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Eric Stephenson, a remarkable individual who, at 48-years-of-age, had already been decorated with the MC and two bars for his gallantry with the regiment in the Great War. He was about to excel once again.

The 27 May opened with a heavy enemy assault on the Dorsets and the 1/8 Lancashire Fusiliers on the battalion’s right flank. Later in the morning Stephenson realized the situation was becoming desperate when a handful of Lancashire Fusiliers arrived with news that the battalion had been overrun. Reports had also come in that 1/Cameron Highlanders had been almost completely wiped out and that the 7/Worcesters on their left ‘were none too happy’. With the enemy enveloping the Dorsets’ right flank and the Argylls’ machine-gun section destroyed to a man, Stephenson was more than a little relieved to receive orders to withdraw to Festubert where the 1st Battalion had been billeted on 16/17 October 1914.

With a textbook display of professional soldiering the Dorsets disengaged and withdrew under fire to establish their new perimeter around the village; with them were the remnants of D Company, 7/Worcesters. Stephenson’s plan was to hold Festubert by defending the four major approach roads: D Company to the north straddling the D116; B Company to the southwest holding the D72; A Company defending the southern approaches from the canal and C Company the eastern end of the D72 and approaches from Violaines. Controlling the battle from battalion headquarters at the crossroads in the centre of the village, Stephenson barely had time to get his men into position before the first attack began at 4.45pm. Infantry supported by six armoured vehicles assaulted the C Company sector but were driven off with the loss of one light tank. Regrouping, the enemy then switched their attack to B Company with nine tanks which, from all accounts, proved to be a ‘hectic action’ as the tanks were driven off again by the remaining 25mm anti-tank guns, Boys rifles and Bren guns. As the enemy withdrew towards Gorre they left eight of the Dorsets’ carriers burning and one destroyed anti-tank gun.

With dusk approaching the B Echelon transport attempted to break out to the north but ran headlong into a German armoured column, the few surviving vehicles managing to return to the perimeter. Time was now running out for the Dorsets as D Company came under attack from six armoured vehicles, one firing straight down the Rue des Cailloux. Major Bob Goff, already wounded from a previous attack, continued to lead the company as they withdrew into an orchard ‘with both sides firing point blank at each other until the Boche decided to pull out’. The final attack came shortly after 7.00pm which, although repulsed, convinced Stephenson the time to break out had arrived.

A lesser individual may well have considered surrendering the battalion at this point but far from beaten and determined to outmanoeuvre his enemy, Stephenson took the decision to lead his surviving men across country to Estaires – a march of about 10 miles. At 9.30pm 15 officers and 230 other ranks – all that was left of the battalion – and a collection of other men from various regiments, assembled south of the village. With Stephenson in the lead and Major Tom Molloy as his assistant navigator, the battalion moved south of the village across the fields before heading northwest to cross the D72. On three occasions they encountered the enemy but each time fortune was on their side and they escaped unscathed. At 2.30am they found themselves on the banks of the canalised River Lawe, a water obstacle they had to cross twice as their route took them unwittingly across a large bend. Tired, wet but triumphant, they arrived at Estaires at 5.00am on 28 May. It had been another impressive chapter in the long history of the regiment and one that was rewarded by Stephenson’s DSO which was announced in October 1940.