Chapter Eight

Calais – The Bitter Agony of Defeat

22–26 May 1940

‘Two of my subalterns were shot dead by snipers outside my HQ, another of my officers was killed further up the street, and my second-in-command was mortally injured when a shell landed flush against my HQ.’

Major Jack Poole, commanding B Company,

2nd Battalion King’s Royal Rifle Corps at Calais.

Twenty miles up the coast from Boulogne, the port of Calais had been an English possession for over 200 years prior to 1558, when Henry II of France finally conquered the last of the English territories taken during the Hundred Years War. In 1805 it was a staging area for Napoleon’s troops during his planned invasion of the United Kingdom. Unlike Boulogne, Calais was not enclosed by semi-circle of rising ground to its direct hinterland making its defence an arguably easier task than that of Boulogne, particularly as it was blessed with numerous obstacles in the form of a network of canals and marshes, which gave defenders of the port an inherent advantage.

At the time of writing very few veterans of the Battle of Calais in 1940 are left and if they were able to cross the channel today they would recognize very little of the ground over which they fought. The expansion of the port as a major ferry and transport hub has seen development that has erased much, if not all, of the nineteenth century outer ramparts and bastions that once encased the town leaving only the canals to bear witness to one of the bloodiest battles of the 1940 Flanders campaign; one that shook this little town to its very foundations over four days in May 1940.

Late on 21 May Major Austin Brown commanding C Company, 1st Battalion Queen Victoria’s Rifles, (QVR) was having supper at the Saracen’s Head in Ashford when a phone call summoned him back to battalion headquarters. Orders had arrived for the battalion to proceed immediately to Dover leaving all vehicles in England and embark for what was described as ‘an undisclosed destination’. Arriving at Dover by 7.30am on 22 May the light drizzle and accompanying mist failed to mask the boom of gunfire from across the water, leaving little to the imagination as to where the battalion was bound. Major Theodore ‘Tim’ Timpson, the battalion’s second-in-command, recalled the confusion on the quayside as the embarkation staff struggled to deal with the units that were arriving:

‘A corporal on the RTO’s staff handed [me] an envelope marked ‘secret’ and addressed to the Officer Commanding. This contained written orders from the War Office; they stated that a few German tanks had broken through towards the Channel ports and that 30 Infantry Brigade would disembark the next day either at Calais or at Dunkirk, according to the situation; the battalion was ordered to proceed to Calais and the CO to get in touch with the local commander or, if unable to do so, to take the necessary steps to secure the town.’1

Having been informed ten days previously that the QVR were being transferred to the 1st London Division most of their vehicles had been handed over to units of the 1st Armoured Division, it now appeared from these new orders that the QVR were about to be reunited with 30 Brigade. Any pleasure that Lieutenant Colonel John Ellison-MacCartney may have gleaned from this news was immediately tempered by the alarming prospect of a Territorial Motor Cycle Reconnaissance Battalion embarking for active service without a single vehicle of any description and little, if any, training in infantry tactics. Rifleman Sam Kydd, serving in 11 Platoon with D Company, greeted their ‘new’ role with stoic resignation:

‘We were of course a motorised battalion and had been trained as a mechanized reconnaissance unit with scout cars and motor cycle and sidecar combinations upon which a machine gun was to be mounted to search out and account for the enemy – in theory that was – and in practice in England. But not in France. All of a sudden we were now infantry and as infantry we marched.’2

Infantry they may have been in theory but in reality the fire power that the battalion of 550 officers and men could generate was significantly below that of a conventional infantry battalion. Timpson was particularly concerned that none of his officers were armed at all and many of the men only possessed the service revolvers that had been standard issue to mechanized reconnaissance drivers.

Part of the problem faced by the embarkation staff at Dover was the influx of men from the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment (3/RTR) who were boarding the SS Maid of Orleans. Their troop train, which had arrived from Fordingbridge in the early hours of the morning, had been greeted by a furious Lieutenant Colonel Reginald Keller who had expected to be reunited with the regiment’s tanks which were being loaded on the SS City of Christchurch at Southampton. Dealing with the irate Keller, who had assumed he was en-route to Cherbourg to join the 1st Armoured Division south of the Somme, was Major Henry Foote from SD 7 at the War Office:

‘He was very angry and wanted to know what the hell was happening and where his tanks were. I explained the situation and gave him the last intelligence reports I had received before leaving London. I told him his tanks would arrive in Calais that morning. He pointed out that all his tank guns were in mineral jelly and it would take at least a day to clean and zero them.’3

Nevertheless, Keller was instructed to report to the senior British officer in Calais for further instructions. His mood was not improved by the fact that neither the name nor the location of this individual was provided.

The two ships taking the QVR and 3/RTR steamed out of Dover harbour at 11.00am to arrive at Calais two and a half hours later. As the Maid of Orleans tied up alongside the Gare Maritime the devastation that met the gaze of Major Bill Reeves, commanding B Squadron 3/RTR, was one that remained etched on his memory as he tried to reconcile the peace-time Calais with the scene that confronted him:

‘The glass from the windows of the customs house and restaurant was strewn all over the quay-side and railway platforms. Black smoke was belching from most of the quay-side buildings and warehouses and the whole area was pretty much pock marked with bomb craters. We were told to get off the quay-side as quickly as possible as it was going to be bombed soon.’4

Reeves’ tanks were by this time moving with the mass of the regiment round the Bassin des Chasses to the sand dunes where there was at least some cover from enemy aircraft.

If Keller had some difficulty locating the senior British officer in Calais it was nothing compared to the surprise on the face of Colonel Rupert Holland when the 46-year-old Keller arrived at his headquarters on the Boulevard Leon Gambetta brandishing the sealed orders he had been given at Dover. Although in daily contact with the War Office, Holland had been given no indication of the arrival of 3/RTR or, for that matter, the QVR and it was only when he read Ellison-MacCartney’s orders that he realized that two battalions of 30 Brigade would more than likely be landing the next day. Furthermore, apart from rather lamely telling Keller his orders would come from GHQ at Hazebrouck, the only intelligence he could impart revolved around reports of light German armour in the area. At the time there were in fact three panzer divisions in the Pas de Calais.

Apparently incredulous that a motor cycle battalion had been sent to him without any of its transport, Holland sent the QVR to secure the six main roads leading into the town beyond the outer perimeter. With no transport, apart from what they could requisition on the spot, the QVR was to defend a wide frontage of 15 miles, which, for a lightly armed battalion without the benefit of any prior reconnaissance or heavy weaponry, was a ludicrous proposition at the best of times. Nevertheless, having established battalion headquarters at the Dunkirk Gate, Ellison-MacCartney returned to the quayside where the QVR had taken up defensive positions to pass on his orders to company commanders. Faced with the longest march along the D940 coast road to Sangatte, B Company, under the command of Captain George Bowring, requisitioned Oyez Farm as their headquarters and sent 5 Platoon and Second Lieutenant Dizer into Sangatte itself. Major Austin Brown and C Company were detailed to block the eastern roads to Dunkirk, Gravelines and Fort Vert while the road block on the Boulogne road was the preserve of Captain Tim Munby’s Scout Platoon and the men of Second Lieutenant Nelson’s 6 Platoon. D Company, which was possibly the least ‘experienced’ company, with a subaltern in command was sent to hold the roads to the south around Les Fontinettes. Appointed to command the company only days before leaving Ashford, Lieutenant Vic Jessop and his 26-year-old second-in-command, Second Lieutenant Anthony Jabez-Smith were very much aware that the road accident which had deprived them of their regular commanding officer two days earlier had removed the one officer who had any experience of warfare. This was soon to change.

By the time Jabez-Smith and D Company were in position, the tanks and Dingo scout cars of 3/RTR were still being unloaded from the SS Christchurch which had finally docked at 4.00pm. As work progressed feverishly to unload 3/RTR’s stores and equipment the tiresome figure of Lieutenant General Brownrigg arrived from Boulogne with orders for the regiment to move immediately to relieve 20 Guards Brigade. Unable to comply, Keller was at pains to point out to an agitated Brownrigg that it was going to be some time before his regiment was ready to move:

‘Tanks are not put into ships by squadrons and are unloaded piecemeal. In consequence it was probable that squadrons would not get their tanks together. I was constantly asked how soon I could be ready and eventually, very reluctantly, said 1.00am on 23 May. Unloading went on during the night of 22/23 May, but very slowly and was considerably delayed.’5

The delay was fortuitous. At roughly the same time Brownrigg was directing Keller to move to the aid of 20 Brigade, the 2nd Panzer Division was beginning its assault on the Boulogne garrison and the tanks of 1st Panzers were heading towards the Forêt de Boulogne; the very place Brownrigg was proposing Keller should direct his tanks towards! Fortunately these orders were superseded by a Major Bailey of the Ox and Bucks Light Infantry who arrived at 11.00pm from Gort’s Headquarters with orders for 3/RTR to move immediately to secure the crossings over the Aa Canal at St Omer and Watten.

Since first arriving at Dover, Keller had been in receipt of three sets of orders in the space of some twelve hours and Bailey’s verbal orders from GHQ – which would see 3/RTR moving southeast instead of southwest towards Boulogne – quite understandably aroused Keller’s suspicions. As far as Keller was concerned he was still under Brownrigg’s orders until Bailey’s identity was vouched for by Holland himself. One cannot help but sympathise with the tank commander: torn between setting out for either Boulogne or St Omer it was only Bailey’s insistence that GHQ orders had priority over all others which eventually won the day.

The task of unloading 3/RTR’s armoured vehicles had not been helped by the loading schedule at Southampton. The twenty-seven Cruisers – the heaviest tanks – had been stowed in the bottom of the ship’s hold with the twenty-one lighter Mark VI tanks and scout cars on the two levels above. Ammunition and spares had been distributed around the various holds without any regard to access and the whole cargo was capped by 7,000 gallons of petrol in four gallon ‘flimsies’ lashed to the deck. On arriving at Calais the job was not made any easier by the French dock workers disappearing shortly after the Christchurch had tied up. But, with the help of a section of RASC dock workers, each tank was slowly unloaded and filled with fuel while the main armament was cleansed by removing the mineral jelly which had been applied prior to travelling. Many, like Trooper Robert Watt, were more concerned with the leaking cans of petrol on the deck, expecting any minute an ‘unfriendly enemy’ to ignite the whole lot and blow them all to kingdom come! Given the huge task confronting the battalion it was hardly surprising that at 12.20am on 23 May 3/RTR was still not in a state of readiness.

Ultimately it was the urgency of the situation that pressed Keller into action. As soon as enough light tanks were unloaded Major Simpson, commanding A Squadron, was tasked with sending out a patrol towards St Omer. Second Lieutenant Mundy with 2 Troop got through to St Omer and reported the town to be in flames but devoid of Germans. Bailey, evidently dissatisfied with Mundy’s report, urged Keller to try to reach St Omer again with his main force while he returned to GHQ with an escort of light tanks from A Squadron. Simpson’s feelings regarding the use of his tanks as escort are not recorded but it is unlikely he was entirely happy about it:

‘About 8.00am I received orders to send a light tank troop to escort Major Bailey to St Omer where he believed GHQ to be. I ordered 2/Lt Eastman with 3 Troop consisting of 3 light tanks to do this. About half an hour after they moved off I received a wireless message from 2/Lt Eastman to say they didn’t know where Major Bailey had got to and asked me what to do. I told him if he could not find Major Bailey at once, to proceed on to St Omer and get in touch with GHQ.’6

Three miles south of Ardres on the N43 Eastman and his patrol ran into enemy forces and only one tank returned to Coquelles. Bailey, who had taken a wrong turning, managed to return after running into a German patrol near Les Cappes with his vehicle punctured by numerous bullet holes as a souvenir of his narrow escape.

By the time Bailey had made his way back to Calais the bulk of 3/RTR was formed up around Coquelles and Keller had established his headquarters at La Beussingue Farm, which today is almost encircled by the channel tunnel terminal and the A16 Autoroute. On his return Bailey stressed the need for Keller to continue on to St Omer, a move that Keller admits was ‘much against his better judgement’ and a view shared by Major Bill Reeves who was now commanding B Squadron from a tank he was unfamiliar with:

‘Owing to the urgency squadrons were formed of the tanks as they were unloaded, with the result that Squadron Commanders did not get their own tanks and in some cases not even their own crews, because the light tanks only had a crew of three, whereas the Cruisers had a crew of five. As squadrons were formed they moved off from the quayside to Coquelles where we arrived at approximately 11.00pm. There the CO gave out his orders. We were to proceed immediately to St Omer for the role of protecting GHQ.’7

3/RTR left Calais shortly after 2.00pm with a troop of light tanks from B Squadron pushing ahead as advance guard. Having passed through St Tricat the fleeting glimpse in the rain of enemy light tanks on the right flank was the first indication of an enemy column in the vicinity, a column that was finally spotted as Lieutenant Williams crested the rise which overlooked Guines. They had found the 1st Panzer Division en-route to Gravelines and there was little alternative but to engage them as best they could:

‘It was not possible to gauge the exact strength of the enemy column, the CO decided to take up a position on the hill south of Guines and attack the column in the left flank. This would have been extremely sound tactics in normal circumstances but on this occasion all was against us. We had no supporting artillery, anti-tank guns, or infantry and our guns were far outranged by those of the enemy ... It was very impressive to see the reaction of the German column on being attacked. They very rapidly dismounted from their vehicles and got their anti-tank guns into action, and soon shots were whizzing past our ears. My own tank was a Cruiser A9, which only had a smoke howitzer and one MG on it. This was not encouraging, as I could only watch other tanks fighting and not hit back myself.’8

Although it quickly became apparent the battalion was outgunned, in the seconds following the initial contact there was a concern that the ‘enemy’ tanks may actually be French. This thought may well have crossed the mind of Captain Barry O’Sullivan, who was second-in-command of B Squadron:

‘On our mutual encounter, both forces appeared to hesitate for some seconds before opening fire. The German tanks were halted on the road and all in position behind trees. We were deployed on the fields and advancing towards them. From the start the enemy were able to concentrate superior fire power on us, as there appeared to be only 3 or 4 of our Cruisers up, who would reply with any effect. We concentrated our machine guns on the lorries.’9

The poor visibility may have provided 3/RTR with a modicum of cover but the battle which ranged over the fields and tracks around Hames-Boucres was still very much a one-sided affair. The lesson that was being dished-out by the German panzers division was simple: that armour alone was unlikely to succeed in the face of an enemy who was able to deploy a combination of tanks, artillery and anti-tank weapons. It was a lesson many British tank units were slow to grasp in the early stages of the war with often fatal consequences: O’Sullivan’s tank was amongst those to feel the full weight of the German fire:

‘My tank was hit twice by 2-pounder shells which smashed part of the off-side suspension and track. We swung broadside to the enemy and managed to crawl down a bank into an extremely well camouflaged hull-down position. On examining the damage, I saw the suspension was damaged beyond repair, and the track was some seventy yards away.’10

O’Sullivan continued to engage the enemy for another ten minutes before the machine guns were put out of action by two further hits on the turret. With one of the crew wounded O’Sullivan managed to operate the third machine gun from the top of the turret until German troops who had moved up through the woods opened fire again with anti-tank guns from 600 yards range:

‘I therefore dismounted the machine gun from the top of the tank and found a gap some fifteen yards away from which to deal with this threat. Whilst engaged in this and in getting the ammunition boxes out, with 4 members of the crew, Galbraith and Price were firing the machine gun ...The two light tanks with me were by now knocked out and appeared deserted and the A13 Cruiser was on fire ... There was no sign of the battalion reappearing and I judged by the shelling they had met heavy opposition behind the wood and had been forced to withdraw towards Calais.’11

They had indeed been forced to withdraw but Keller was determined to have another crack at the panzers, this time from the south. With his own tank damaged by a shell exploding against the turret and disabling the main armament, Keller ordered his tanks to retire under the cover of a smoke screen to a new position behind the railway line that ran southwest from Calais round Pihen-les-Guines:

‘I rallied the battalion back behind the railway and had just ordered a squadron forward when a message from Calais was picked up saying a Brigadier Nicholson wanted to see me. I queried this but was told, as far as I could make out, that there were new orders for me. The wireless was very indistinct and neither I nor my Adjutant could quite make out what was required.’12

Nicholson’s ill-timed request had caught Keller in the midst of a tank battle and although Keller’s account – which was written sometime after the battle – makes no mention of it, the story that echoed across the airwaves of the 3/RTR radio network was that Keller had replied with the words, ‘Get off the air, I’m trying to fight a bloody battle’. Nevertheless, an order was an order and the surviving tanks of 3/RTR made their way back to Coquelles where the meeting between Keller and Nicholson took place at 8.00pm on 23 May.

While the tank encounter between 3/RTR and the 1st Panzer Division was taking place during the afternoon of 23 May, the two Green Jacket battalions were disembarking at Calais. Both were regular battalions with a long pedigree whose parent regiments had been raised over 140 years previously. Both regiments had fought with distinction during the Napoleonic Wars and were arguably amongst the best trained rifle regiments in the British Army. Earmarked initially for the Norwegian campaign they were the only two mechanized infantry battalions the British Army possessed in 1940 and thus considered eminently suitable for securing Calais as a supply route for the beleaguered BEF.

The first to arrive was the 2/King’s Royal Rifle Corps (2/KRRC) on board the SS Royal Daffodil. In command was 43-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Euan Miller who had served in the 4th Battalion in France with Jack Poole – now commanding B Company – in 1915. An experienced soldier, who had been awarded the MC in 1918, he was less than happy with the time it took to unload the battalion’s vehicles and equipment from the SS Kohistan which finally nosed its way into the harbour at 4.00pm.

The 1/Rifle Brigade together with Brigadier Nicholson and the brigade staff arrived on the SS Archangel which docked shortly after the KRRC. In command of the Rifle Brigade was 44-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Chandos Hoskyns, a well respected officer who had been appointed in 1938 and, like Miller, had served in the previous war. The Rifle Brigade’s vehicle ship, the SS City of Canterbury, the same ship that had brought the QVR from Dover the previous day, arrived an hour behind the Kohistan and did not berth until almost 5.00pm by which time the dock was being shelled by German artillery.

Nicholson had very little time in which to grasp the increasingly desperate nature of the picture that was now unfolding around him. Late in the afternoon, having made the return journey to see Holland at his Calais Headquarters, he briefed Miller and Hoskyns. Miller’s recollection of that meeting, which he later relayed to his company commanders, bore little resemblance to the task they were expecting to carry out: that of securing the lines of communication between Calais and the BEF:

‘The situation was that the QVR, who had landed yesterday, were blocking the main roads leading into the town. These blocks were generally a mile or two outside the town. 3/RTR Tanks had been sent off towards St Omer about midday on orders from GHQ and after some rather heavy losses near Guines were now astride the roads west of Coquelles and were in touch with the enemy. In and around the town were various AA and searchlight units and also troops from Boulogne. Most of these were disorganized and of little value. Germans with tanks and artillery were rapidly approaching the town and had begun to shell it. 30 Infantry Brigade could obviously not carry out its original role and the immediate problem was the defence of Calais itself.’13

It was now becoming obvious that the enemy was far stronger than originally expected. 3/RTR had already lost four light and three Cruiser tanks in the encounter at Hames-Boucres and although some crews like O’Sullivan’s were trying to get back to the safety of British lines, the unit’s introduction to mobile warfare had been hard. In a separate action at Les Attaques – some two hours before 3/RTR became engaged – the men of 1/Searchlight Battery had also clashed with the tanks of Kirchner’s 1st Panzer Division. Arriving with three detachments from C Troop, Second Lieutenant Barr barricaded and held the crossroads for almost three hours before they were forced to surrender. Another detachment was in action at the Le Colombier crossroads just east of Orphanage Farm where the panzers were again held up for two hours before the survivors withdrew to the outer perimeter.

In Calais, Lieutenant Gris Davies-Scourfield – in command of 5 Platoon of B Company of the KRRC – noted the the precarious nature of the proposed defence as outlined during the short briefing given by his company commander, Major Jack Poole:

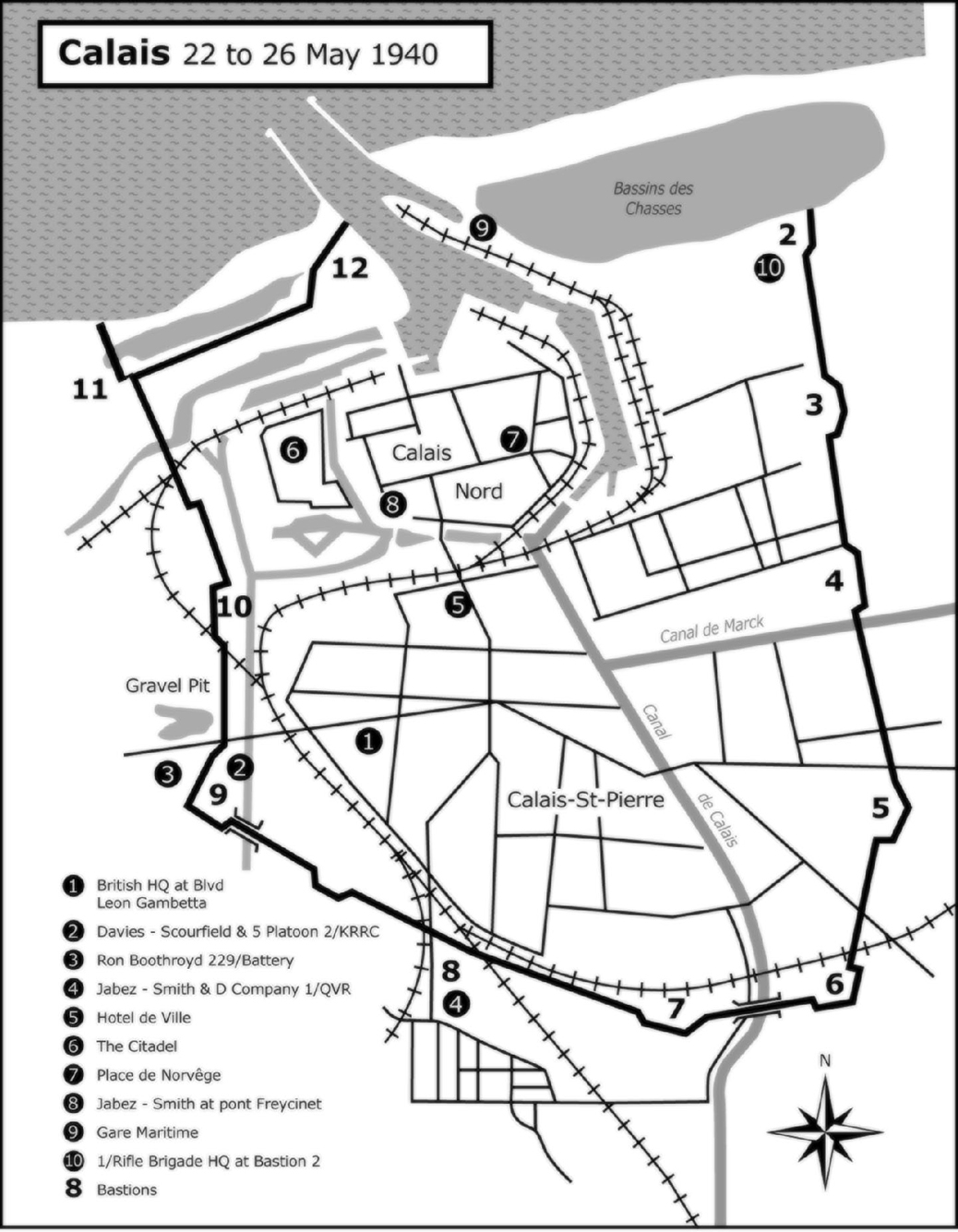

‘Our battalion’s immediate task was to secure the outer perimeter of Calais from the coast on the west to a point on the southern edge of town where the Rifle Brigade would continue to hold the line to the coast on the east side, a front of about 8 miles. The QVRs and 3rd Tanks would continue to hold their forward positions as long as possible: on withdrawing, the QVR companies would come under command of the battalion whose front they had been covering. The 2-pounder guns of 229 Anti-Tank Battery were to cover the main roads.’14

Nicholson opted to defend the seventy-year-old heart shaped, outer perimeter of Calais part of which, to the south of the town, roughly followed the line of the railway to Gravelines. This perimeter was interspersed by twelve bastions which had originally been an integral part of the outer earth rampart. While units of 30 Brigade would garrison the majority of the perimeter, the northernmost bastions and fortifications around the harbour would be manned largely by French naval reservists under Capitaine de Lambertye. The term ‘bastion’ was somewhat of a misnomer as many of these ageing redoubts – where they existed at all – now bore little resemblance to their original grandeur, as Lieutenant Davies-Scourfield found when deployed to Bastion 9 with 5 Platoon on the Coquelles road. He found himself defending ‘a high semi-circular mound with blocks of stone and concrete round the crest of its circumference’, which was all that remained after the embankment and bastion had been demolished to make way for the railway.

The 229/Battery anti-tank guns had arrived on the SS Autocarrier earlier in the afternoon of 23 May still carrying the vehicles of 12/Wireless Section which it had failed to unload two days earlier. According to Lieutenant Austin Evitts, the ship’s captain had scuttled out of the harbour after being told he would have to wait until morning before power was restored to the dock cranes.15 Now berthed alongside the Gare Maritime, there had only been room for eight of the twelve guns in the crowded hold. Disembarking with the men of the anti-tank battery was Gunner Ron Boothroyd, a territorial with eight year’s service, who was soon employed with his mates digging a gun pit by ‘the side of a country lane between two small hills’. Quite where Boothroyd’s gun was is unclear but he may have been near Bastion 9 in front of the flooded gravel pit. Every gun, he wrote, went to a different spot outside the town about one mile apart. One of these guns was in position with D Company of the QVR at Les Fontinettes.

The QVR had passed a relatively peaceful night on 22 May with nothing particularly untoward taking place. Dawn the next day saw the platoons of D Company consolidating their road blocks on the approach roads to the town. The first brief contact with the enemy came at around 9.00am when two attempts by German light tanks were repulsed by the guns of a French detachment. There was little further excitement until later in the afternoon when two platoons of the KRRC and RB took up positions astride the St Omer Gate on the ramparts behind them. Jabez-Smith’s account records that orders to retire to the area around Bastion 8 came soon after dawn on 24 May when D Company were ordered to reinforce the perimeter line held by the KRRC. From all accounts it was not a moment too soon. ‘Immediately the men were in position, firing took place, the enemy being in houses and gardens in the neighbourhood we had just left.’ After establishing company headquarters in a house behind the firing line, Jabez-Smith set off to visit the platoon positions:

‘Bill [Brewster, 11 Platoon] was already in great trouble. He had, at the suggestion of the 60th [the old regimental number of the KRRC] platoon commander on his left, taken up a position with no protected line of withdrawal. There was an exposed railway embankment to cross to get to and from him and he was unable to get across because the railway was under constant fire. Apparently Bill had reported to Vic [Jessop] that the position was untenable. He had already two dead and two wounded. Vic gave orders for him to withdraw behind the railway but the runner had been unable to get over [the railway].’16

Realizing Brewster’s platoon desperately needed covering fire to escape their predicament Jabez-Smith resolved to see for himself the state of Brewster’s men:

‘So I made a run for it, up over the embankment – a bullet whistled past my right ear – down the other side and I was soon with Bill. In a lock-up under the embankment were crowds of refugees. A dead soldier was lying up above in the open and could not yet be brought in. Another, wounded, had to be brought down behind the shelter.’17

Running the gauntlet of enemy fire again Jabez-Smith safely negotiated the railway embankment ‘with his heart in his mouth’ and organized covering fire from the two platoons of the KRRC. Using the short breathing space this gave them, Brewster and his surviving men escaped the confines of the embankment without further casualties. The QVR – apart from Munby’s men on the Boulogne road who had, by now withdrawn into Fort Nieulay – were now back on the perimeter, the battalion coming under the orders of the Green Jacket unit they were reinforcing..

At Bastion 9, Davies-Scourfield and 5 Platoon were being pressurised by an increasing level of fire as the German attack gradually gathered momentum during the morning. From his vantage point he was able to see an enemy armoured attack begin to move forward:

‘I watched fascinated and I’m sure the eyes of all of us were on them, as what seemed to be a squadron of medium tanks slowly deployed into two long lines ... I wondered how we would stop them if they kept rolling forward, which was probably what they intended to do. In fact they eventually descended into dead ground where we could not see them, by-passed Fort Nieulay and supported an infantry advance against Wally’s [Findlayson] two sections south of the road and against the gap between us and C Company on our right: here enemy infantry succeeded in getting into a cemetery but were quickly driven out.’18

Support soon clattered up in the form of three light tanks from 3/RTR, under the command of 21-year-old Second Lieutenant Tresham Gregg. Gregg’s opinion of Bastion 9 as a laughable defensive position against tanks proved to be alarmingly prophetic and was one that Davies-Scourfield remembered throughout his subsequent captivity. But there was little time to consider Gregg’s opinion as German infantry and tanks advanced on their position in strength:

‘Martin Willan’s [8 Platoon] was severely pressed, but after a prolonged and at times desperate fight, repulsed the enemy and destroyed two of his light tanks, but only after two counter-attacks had restored their original positions. Meanwhile Wally Findlayson and his two sections were forced to abandon their forward posts and come back to join us in the redoubt. This cleared the way for the enemy to come forwards into the houses and gardens immediately facing us, and a lot of bullets started whizzing past our ears or chipping the concrete blocks.’19

It looked very much as though Nicholson’s fears of a breach in the outer perimeter was becoming a reality.

On the Rifle Brigade sector Lieutenant Colonel Hoskyns had established his headquarters at Bastion 2 near the Bassin des Chasses de l’Est and was still fuming over the loss of half his battalion’s fighting vehicles. Incredibly the City of Canterbury had closed down the hatches at 7.30am on 24 May and sailed full of wounded before the RB could complete their unloading. His subsequent concerns over the battalion’s severe deficiency of equipment -which left them 50 per cent short of weapons and ammunition – may well have been further fuelled by the intelligence brought back by 22-year-old Second Lieutenant Tony Rolt.

During the evening of 23 May Rolt’s Scout Platoon was sent out from Calais ahead of a ration column which was waiting to leave for Dunkirk and escorted by 40-year-old Major Arthur ‘Boy’ Hamilton-Russell and four Rifle Brigade platoons. As darkness fell, Rolt’s patrol reached Fort Vert on the D119 where they discovered from the locals that German tanks had been seen in the area. It was while pondering his next move that a dispatch rider (DR) arrived with orders for the platoon to return to Calais. Rolt, fearing the DR may be a Fifth Columnist, was suspicious and asked for written confirmation while he moved his vehicles into an all-round defence position to wait for the ration column to pass. It failed to arrive. With the darkness came the full realization that the myriad of bonfires they could see all around them were in fact the fires lit by the tank crews and units of the 1st Panzer Division and it was only with great dexterity that they managed to slip away undetected early the next morning.

While Rolt’s patrol was contemplating the strength of the German panzer units which appeared to completely surround them, another episode was unfolding along the Gravelines road. Having met Lieutenant Colonel Keller at 11.00pm on 23 May at the Pont St Pierre, Brigadier Nicholson asked that a patrol be sent out towards Marck with the intention of getting through to Gravelines and making contact with 69 Brigade. Bill Reeves left Calais with three light tanks and a heavier Cruiser later that evening:

‘Sergeant [Jim] Cornwell was commanding the point tank of my troop, followed by Peter Williams, the troop commander, with his reserve tank in rear of him. I followed close behind ready to give covering fire with my 2-pounder should we encounter anything ... Nothing happened for the first two miles as we drove out of Calais to the clear air of the open country [and] our spirits began to rise. They soon dropped off again though when we saw in front of us an ominous black looking mass in the middle of the road.’20

The ‘black looking mass’ was a road block made up of abandoned vehicles that had been towed across the road. Reeves, determined to get through to Gravelines if at all possible, gave the order to continue through the gap that had been left between the vehicles. All four of Reeves’ tanks managed to squeeze through. But as Reeves later wrote, there were three road blocks which fortunately were not defended or even manned as check-points:

‘No sooner had we got through than we realized that whatever happened there was no turning back, for the enemy was present in large numbers on either side of the road ... we pushed on rapidly and in another few hundred yards we were among German troops who were sitting and walking about, they did not seem to be in the least perturbed at seeing us, and I soon realized that they thought we were their own tanks.’21

Passing German troops who waved at them, they pressed on to Pont Pollard in Marck where the road crosses the canal. Here the vigilant Cornwell in the lead tank spotted a ‘daisy chain’ of eight tank mines wired together. If a tank ran over one, the whole lot would explode together:

‘I called up Bill Reeves and he used his 2-pounder but no luck. The noise we made roused the enemy and things were getting a bit hectic so I asked him to give me covering fire while I had a look ... Luckily the tow rope on the front of the tank was handy and I got Davis (the driver) to come up close and I hooked the rope over the [mines].’22

Davis reversed the tank and cleared the bridge of its deadly payload, but their troubles were not over. A short distance further on another tank obstacle brought two of the light tanks to a standstill. Coils of anti-tank wire, designed to wind itself around a tank’s sprockets, had been laid across the road and it took several more heart-pounding minutes to remove this with wire cutters. That done Reeves and his tanks were clear of the enemy and arrived at Gravelines at 2.00am on 24 May.

There are conflicting accounts concerning the radio message that was reported to have been sent from Reeves to Keller. Reeves is adamant that his radio was not working and no warning was sent back to Calais but in one of the three reports of the Calais action written by Keller he mentions a garbled message from Reeves containing the words ‘Gravelines’ and ‘canal’. If this is correct then Nicholson may very well have taken this to mean the route was clear of the enemy and consequently ordered the ration convoy to proceed.

Hamilton-Russell got away some time after 4.00am on 24 May along the D248 – over a mile south of Rolt’s route – with five tanks from C Squadron 3/RTR leading. About 2 miles outside Calais amongst the ‘suburban ribbon development and allotments’ they found the road blocked at le Beau Marais with the same road blocks that Reeves had passed earlier. This time the brazen approach used by the B Squadron tanks was clearly not going to work and the convoy stuttered to a halt under a hail of enemy fire. Despite Lieutenant John Surtees pinning down German riflemen with his carrier platoon and Lieutenant Edward Bird’s platoon attempting to outflank them, the enemy were too strong. With increasing casualties from mortar fire and with every chance of being surrounded, Hamilton-Russell received orders to withdraw with two dead and several wounded.

Dawn on Friday 24 May began with a hail of heavy mortar fire on the 30 Brigade positions along the outer perimeter. Generalleutnant Ferdinand Schaal’s 10th Panzer Division had now surrounded the town and two battalions of IR 86 were intent on capturing the old town of Calais Nord and the Citadel, while a further two battalions from IR 69 had the harbour and Gare Maritime as their objective. The IR 69 attack on the Rifle Brigade did not really materialize until later in the afternoon as their first task was to relieve the units of the 1st Panzer Division allowing them to continue towards Dunkirk.

By late afternoon the situation along the perimeter had become critical and hour by hour it was becoming obvious that it could not be held much longer. Enemy attacks along the KRRC front were so severe that on several occasions Hoskyns was asked by Miller for assistance from his reserve platoon to plug gaps in the line. At 4.00pm Tony Rolt was ordered to take his mortar section and 11 Platoon to put down mortar fire on the Rue Gambetta. Here he learned from the QVR that enemy tanks had already penetrated the KRRC perimeter and were at large in Calais-St-Pierre. As the day drew to a close Nicholson would have drawn some consolation from the assessment of his defence recorded in the 10th Panzer Division war diary which noted that British resistance from ‘scarcely perceptible positions’ was strong enough to prevent anything more than local successes along the perimeter. The diary also noted that ‘a good half ’ of their tanks and a third of their personnel, equipment and vehicles had been lost.

However, on the debit side, the French garrison at Fort Nieulay in the west had surrendered along with Captain Tim Munby’s detachment of QVR who had taken refuge there. The surviving units of the QVR had all withdrawn from their positions and, ceasing to operate as a separate battalion, had been distributed between the two Green Jacket battalions. Six of the eight guns of 229/Anti-Tank Battery had been destroyed including Ron Boothroyd’s, his detachment needing no persuasion to climb aboard the truck and make ‘like lightning for Calais’.

Although the outer perimeter was now under considerable pressure, Nicholson’s decision to order the brigade to fall back at dusk onto a shorter line along the Canal de Marck was given further impetus by the encouraging signal he had received earlier informing him that the evacuation of 30 Brigade had been agreed ‘in principle’. It would begin at 7.00am the next morning, a decision heartily welcomed by Lieutenant Colonel Miller of the KRRC:

‘[Nicholson] ordered companies to hang on where they were until after dark and organised a line of posts across the centre of the town to prevent any further penetration by the enemy from the southwest. These posts consisted of two platoons of the Rifle Brigade sent up to help, some parties of A and B Companies and the Cruiser tank, which was left on the main crossroads on Rue Gambetta, and one searchlight platoon which blocked the road by the station behind the right of B Company.’23

It was a short lived reprieve. At 11.30pm that evening the imposing figure of Admiral James Somerville arrived at Nicholson’s headquarters with a brusque message from the War Office. Somerville, who had crossed the channel in HMS Wolfhound to explore the possibility of using dismounted naval guns as anti-tank weapons, reported that Nicholson received the message with a stoical calm. Its contents were blunt and to the point:

‘In spite of the policy of evacuation given you this morning, fact that British forces in your area now under Fagalde who has ordered no, repeat no, evacuation means you must comply for the sake of Allied solidarity. Your role is therefore to hold on, harbour being for the present of no importance.’24

Commanding the French XVI Corps, General Robert Fagalde had been appointed by Weygand on 24 May to command the troops in the three Channel ports and had at once issued orders forbidding evacuation from Calais. It is probable that had Churchill not been personally ‘stung’ by Reynard’s complaint that the British had abandoned Arras, Fagalde’s almost resentful order would have been ignored. As it was Churchill was of the opinion that British honour was at stake and 30 Brigade was to be sacrificed to appease the French and bolster the alliance.

Giving little credence to the notion that the British 48th Division had been ordered to fight its way through to Calais – although orders had indeed been given to 145 Brigade to move there – Nicholson decided to make Schall’s tanks and infantry fight for every inch of the disputed port and so moved his headquarters to the Gare Maritime. The British withdrawal to Calais Nord was marked by the failure of the French to destroy the three main bridges, making the security of 30 Brigade far more difficult for 40-year-old Major ‘Puffin’ Owen, second-in-command of the KRRC, who had been given responsibility for holding the bridges.

At dawn on 25 May Second Lieutenant Jabez-Smith and D Company of the QVR were established behind the canal close to the barricaded Pont Freycinet alongside D Company of the KRRC. Since leaving Les Fontinettes they had lost some twenty men either killed or wounded including Lieutenant Rae Snowden who had been hit in the eye the day before. Though the day had begun with the usual mortar bombardment, which continued intermittently throughout the morning, Lance Corporal Richard Illingworth was more concerned with the escalating level of machine-gun fire that was being directed at them from across the canal. German forces were a matter of yards away:

‘Heavy machine-gun fire started from the direction of the bridge over the canal near 13 Platoon. As many of D as was possible returned fire: this was difficult as our line was at right-angles to the bridge. The Boche fire was all too accurate; as I was going along the road to battalion HQ I could feel the whiz of bullets. One rifleman (I forget who) was killed as I was talking to him.’25

With every bridge blocked by abandoned vehicles and practically every house along the perimeter turned into a defensive position, the men of 30 Brigade were certainly in no mood to give up their ground. Completely overlooked from the clock tower of the Hotel de Ville they were at the mercy of German snipers making any movement around the bridges particularly difficult. Anthony Jabez-Smith admitted to being more than a little rattled by spasmodic bullets that whistled past him like mosquitoes, noting at one point that he thought they were coming from behind him!

After the German swastika was raised over the Hotel de Ville the captured Calais mayor, a Jewish shopkeeper named Andre Gershell, was escorted to the Citadel with a demand from his German captors for Nicholson’s surrender. Lieutenant Austin Evitts was present when Gershell arrived:

‘It was in the courtyard of the quadrangle where the Brigadier received him and the message was an ultimatum. If he had not surrendered in 24 hours, the Germans had said, Calais would be bombed and shelled and razed to the ground, and the Mayor was making a special plea, he said, to save the town from further destruction and loss of life.’26

Evitts tells us that Nicholson’s answer was decidedly brusque and was spoken loud enough for all those in the vicinity to hear. ‘Tell the Germans’, he said, ‘that if they want Calais they will have to fight for it.’ This reply, which has passed into Green Jacket legend, was hardly what the 51-year-old Schaal was expecting. In what seemed like a fit of pique the British refusal was met by a ferocious bombardment which rained down on the British positions in a blizzard of high explosive. Near Pont Freycinet Rifleman Sam Kydd was taking cover with the men of 11 Platoon and remembered the ‘shattering crack of mortar fire ... one direct hit wiped out a pocket of our chaps and a rain of shrapnel incapacitated several near me’.

At 2.15pm, while still under this ferocious attack, Nicholson received a message from Anthony Eden, the Secretary of State for War, which Lance Corporal Jordan dutifully recorded in the wireless log before handing it to Lieutenant Evitts:

‘Defence of Calais to utmost is of vital importance to our country and BEF as showing our continued co-operation with France. The eyes of the whole Empire are upon the defence of Calais and we are confident you and your gallant Regiments will perform an exploit worthy of any in the annals of British History.’27

Then, abruptly the German barrage stopped. Tightening their grip on their weapons the riflemen of 30 Brigade waited for the next onslaught. But instead of infantry and tanks it came in the form of a flag of truce carried by a blindfolded 69th Panzer Grenadier officer called Hofmann, flanked by a French captain and a Belgian soldier. Once again surrender was demanded and once again Nicholson refused: ‘The answer is no as it is the British Army’s duty to fight as it is the German’s.’ Hofmann was sent back alone with Nicholson’s reply in his hand.

The inner perimeter was finally pierced after a German radio message was intercepted indicating an assault on the southwest defences was being planned. Whether Nicholson’s decision to tackle this threat with a counter attack was an error of judgement is debatable, but the subsequent order for the Rifle Brigade to release all its carriers to join the attack may well have been imprudent in the circumstances as Major Allen was at pains to point out:

‘All reserves had become involved from the previous day with the exception of Headquarters and two platoons of C Company. I Company relied particularly on their three carriers and Corporal Blackman’s mortar section of Tony Rolt’s carrier platoon to cover bridges on their extended front, and both these and A Company’s bridges were in imminent danger of being forced.’28

With Nicholson out of radio contact, the objections voiced by Hoskyns were overruled by Holland who insisted the attack went ahead. Even though the attack was cancelled at the last minute, several vehicles were already committed and it was too late to prevent the enemy from entering Calais Nord.

By 3.00pm enemy units had succeeded in breaking through the Rifle Brigade positions in two places and after working their way through the narrow streets established themselves behind the platoons holding the southern perimeter line. In the street fighting that followed 21-year-old Second Lieutenant David Sladen was killed during a counter-attack and Major John Taylor commanding A Company was severely wounded. Also amongst those killed during this desperate encounter were Second Lieutenant George Thomas and 36-year-old PSM Ivan Williams who lost his life on almost the same spot as Second Lieutenant Adrian Van der Weyer.

As the Rifle Brigade fell back, the left flank of the KRRC became exposed; a situation not helped by the canal bridges in their sector remaining intact which handed the advantage to the superior strength of the enemy. But what really added to the already high casualty rate was the heavy and increasingly accurate mortar fire, directed from the vantage point of the Hotel de Ville clock tower. It engulfed the Citadel in sheets of flame during which two tanks were knocked out on the bridges and Major Owen of the KRRC was killed; news which Davies-Scourfield found ‘quite devastating’.

But there was worse to come. At 3.30pm a shell exploded in the Rifle Brigade HQ Company positions wounding Company Quarter Master Sergeant Clifton and the unfortunate John Taylor for a second time. As the smoke cleared it became obvious that Hoskyns had also been hit, and although at the time he put on a brave face his wounds were so severe that he died in England after being evacuated.29 Taylor survived but never regained his fitness for further active service.

With command of the Rifle Brigade now in the hands of Major Alexander Allan and each company reduced to fighting its own battle, they withdrew street by street towards the harbour. Soldiers fight for their mates and rely on their training and experience to see them through adversity. These men were no different. They gave ground reluctantly, counter-attacked when they could and continued their resolve to make their enemy fight for every inch of the battered streets. Fortunately the enemy assaults died away at dusk giving the Royal Navy the opportunity to bring in more ammunition and evacuate some of the wounded. Amongst these men was Second Lieutenant Gregg of 3/RTR who had been badly wounded by mortar fire, Major John Taylor and Chandos Hoskyns.

Sunday 26 May opened with the usual artillery bombardment but the expected dawn attack by IR 69 failed to materialize. At 9.30am the air was filled with the sound of enemy aircraft. Lieutenant Davis-Scourfield was in the Place de Norvêge with B Company KRRC when the air attack began:

‘No-one who experienced the attack that morning is ever likely to forget it. A hundred aircraft attacked the Citadel and old town in waves. They dived in threes, with a prolonged scream, dropping one high explosive and three or four incendiary bombs. Each of this series of attacks lasted twenty-five minutes. The first effects on the defence were paralyzing but, as others had experienced with Stukas, the damage was moral rather than physical ... As the Stuka attack died away our contemplation was quickly disrupted, for down the street came running and clattering some 15 men headed by Richard Warre (D Company Scout Platoon Commander) and his Corporal Birt: they flooded into the house and cellar, Richard reporting that our forward positions had been shelled out and the enemy had forced the line of the canal.’30

Whether it was common knowledge that there was to be no evacuation was of little importance to the surviving men of 30 Brigade and even to the most optimistic it must have been obvious that they were now engaged in a battle that would only conclude in death or captivity. Some such as Major Austin Brown of the QVR still held out some hope for a final evacuation:

‘At dawn we moved down to the quay. We had hoped we would be evacuated, but there were no ships to be seen and the prospects seemed very gloomy. Some wounded were taken off later in a pinnace during the bombing. We were ordered to continue the defence and positions were taken up around the Gare Maritime.’31

If any ships were to be seen they would have been those responding to Nicholson’s request for a naval bombardment which had been asked for in the last message sent from the Gare Maritime from Calais garrison. Sadly the bombardment only materialized later that evening by which time it was too late.

By midday the British line had been pushed back to a final perimeter around the harbour, a withdrawal that had cost all three battalions further casualties. Major Allan’s account makes for difficult reading as he describes the last hours of the Rifle Brigade:

‘Much more could be written of the fighting on this last day: the tough resistance put up on the right by Tony Rolt’s scout platoon, PSM Easen’s platoon of B Company (he later died of wounds) and others; of Arthur Hamilton-Russell, mortally wounded in an attempt to gain observation from the most exposed point near him, after as hard a four days fighting and work as ever a soldier did; of Tony Rolt’s final gallant effort, almost alone, to seize a possible point of vantage ... of the hours of steady and accurate shooting put in by Peter Brush’s command where Rifleman [Frederick] Gurr got badly wounded in the leg he was to lose, Sergeant Welsh shot through the jaw, Rifleman Murphy, who had found and got into working order a Lewis gun; David Fellowes of C Company, with a large hole in his head ... Of those who died, although the deeds of some are not known in full, it would be impossible to write too much.’32

Shortly before 4.30pm Nicholson realized the fight for Calais was over. Austin Evitts recalled the gloom and despair that descended on the small group ensconced in the Citadel. ‘I looked across at the Brigadier. The bitter agony of defeat lay unmistakably written on his face. Now he was about to suffer the humiliation of surrender.’ Moments later Nicholson surrendered the Calais garrison. Major Austin Brown remembered the Germans shouting for them to surrender as they were surrounded and the look of anguish on the face of Lieutenant Colonel Ellison-MacCartney’s face as he ordered them to put their weapons down. But even if Nicholson had wanted to, he could not have surrendered his entire brigade as communications had long since broken down. Split into small groups they were inevitably hunted down and either killed or captured when their ammunition ran out.

No doubt watched by Austin Brown and the surviving QVRs of C Company, Major Hamilton-Russell was spirited away with several other wounded by a naval vessel that had managed to berth long enough to embark the most seriously injured. Sadly he died of his wounds later that afternoon, but for many others their final resting place would be where they fell. While the number of wounded will never be known, the exact number of those killed in action or who later died of their wounds still remains imprecise. The CWGC database lists 192 men of the three 30 Brigade infantry battalions killed in action or died later of wounds, it is thought another 100 were lost from 3/RTR and the various Royal Artillery units that fought in the battle.33

Over 200 men were evacuated before the town fell and another 47 were taken off the eastern breakwater by HMS Gulzar during the night of 26 May; added to this number should be the 200 wounded that were taken off by the Royal Navy during the course of the battle. Lieutenant Colonel Keller escaped with Major Simpson and reached Gravelines by walking along the beach and both were evacuated from Dunkirk. Barry O’Sullivan was eventually captured and taken prisoner along with some 2,400 men of all ranks who surrendered with Nicholson.

Of those who evaded capture and returned to England the adventures of Lance Corporal Richard Illingworth, Major Denis Talbot – Nicholson’s brigade major – Lieutenant William Millet and Captain Alick Williams – the KRRC Adjutant – took them south to the River Authie from where they crossed the channel by boat with a party of French soldiers and were picked up by HMS Vesper on 17 June. Another officer who put to sea was Second Lieutenant Lucas who had commanded 8 Platoon in C Company of the QVR. Escaping from the long line of prisoners as they were marched down the St Omer road he managed to find a rowing boat near Cap Gris Nez, which he then steered for Dover, ‘rowing like a Brighton boatman on a Saturday afternoon’. He was picked up by the Navy half a mile off the British coast.

In 1945 when the full story of the fight for Calais had been told, the September issue of the London Gazette published the full list of gallantry awards. Amongst the profusion of names was Lieutenant Colonel Miller who was awarded the DSO along with Major Alexander Allan. Gris Davis-Scourfield, Tony Rolt, William Millet and Geoffrey Bowring each received the MC while Rifleman Frederick Gurr was awarded the MM. Disappointingly both Lieutenant Colonels Hoskyns and Ellison MacCartney were only mentioned in despatches as was the gallant Arthur Hamilton-Russell.

The political fallout which followed the capture of Calais has been the subject of controversy amongst historians ever since. Churchill always maintained it played an essential part in the escape of the BEF from Dunkirk but others, such as Heinz Guderian and Basil Liddell Hart, took the opposite stance. However, the facts of the matter are quite clear. Nicholson’s 30 Brigade held the 10th Panzer Division up for three days and inflicted a severe mauling of its infantry and armoured vehicles thus diverting much of Guderian’s heavy artillery from pounding Dunkirk – his key objective. If one also considers the delay on the 2nd Panzer Division imposed by 20 Brigade at Boulogne, then the feat of arms accomplished by two under-strength infantry brigades and a regiment of tanks was considerable.

The notion that the Germans considered Calais and Boulogne a threat to their advance on Dunkirk is supported by Captain Barry O’Sullivan’s statement after his escape from captivity in 1941. Under interrogation on 22 May his German captors were most anxious to learn more about the ‘large and powerful tank which they heard we had kept very secret’ and was said to have landed with the whole of the 1st Armoured Division at Calais. O’Sullivan saw no reason to dissuade his interrogators of their belief in a ‘supertank’ and was left with the distinct impression that the enemy ‘would not consider moving in the direction of the BEF with this threat to their left flank in being’.34

Of greater significance is the fact that between 22 and 26 May Boulogne and Calais were not simply by-passed as Arras had been, but were the objects of costly and time consuming assaults by two panzer divisions that could very well have been directed straight to Dunkirk. What’s more, the infamous Halt Order (see Chapter 9) was not applied to Boulogne and Calais, leaving one to speculate whether the two channel ports were indeed regarded as a continuing threat to the flanks of the German attack.

Without doubt a large proportion of the Calais garrison could have been evacuated on the night of 25 May, as had happened at Boulogne two days earlier. The Royal Navy may well have been able to evacuate the surviving units of 30 Brigade, whose continued presence in Calais served only to add to the already soaring casualty figures. As it was, most of the surviving Calais garrison spent the remaining years of the war in prison camps which, for men like Major Jack Poole of the KRRC – who went into ‘the bag’ near Abbeville – would be their second period of captivity in twenty-three years.