Chapter Eleven

Hondeghem and Cäestre

25–28 May 1940

‘We had no tanks or aircraft to support us, as there were only a few in France. Often the Germans would have one small plane above us guiding and giving range to their artillery. On one occasion Colonel Whistler sent back a message request: “Give me a Hurricane for half an hour” but there were none to give.’

Private Bert Bleach, 4th Battalion Royal Sussex.

Brigadier Nigel Somerset’s Somerforce command also extended to Hondeghem, a small village a little over 3 miles southeast of Cassel. The story of the stand at Hondeghem, now firmly enshrined in RHA legend, began on 24 May when 5/RHA moved from the Forêt de Nieppe and was stopped on its way to Cassel with orders to deploy one troop to the village. Accordingly, the four 18-pounders of F Troop, under the command of Captain Brian Teacher, were detached from K Battery to hold the village along with seventy-five men and an officer from the 2/Searchlight Regiment armed with twelve Bren guns and half a dozen anti-tank rifles. Joining them was the battery commander, Major Robert Rawdon Hoare and a small HQ under Battery Sergeant Major (BSM) Reginald Millard.

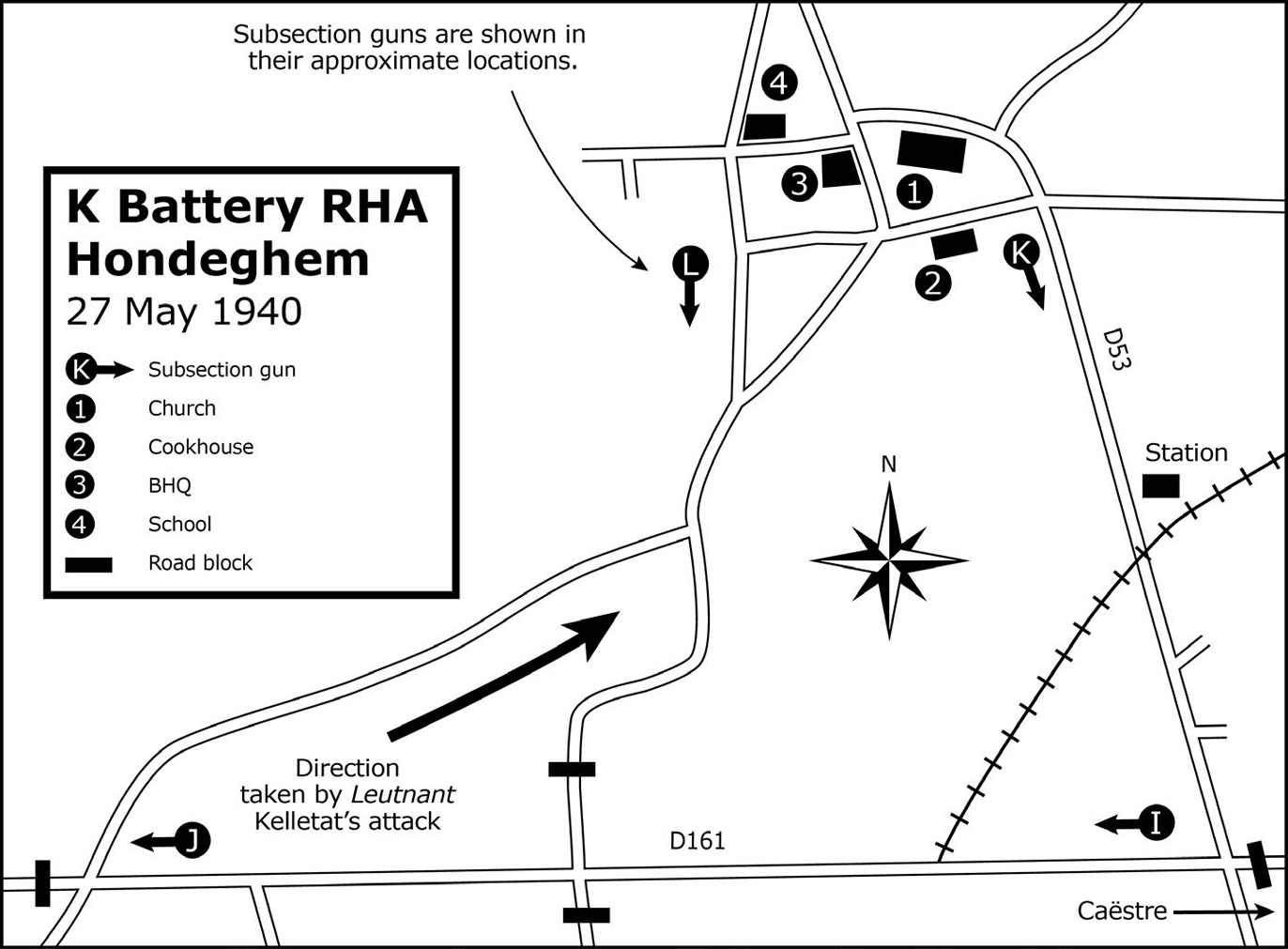

Rawdon Hoare deployed two guns – I and J Subsections – covering the southern outskirts of the village on the Rue de Staple and the remaining pair – K and L Subsections – in the square around the church. Headquarters was set up close to the church while the remaining troops were set to work blocking roads and preparing defensive positions. Their first brush with enemy tanks came early on 26 May 1940 when Second Lieutenant Mortimer Lanyon was sent out with one gun to support a reconnaissance troop of 1/Fife and Forfar Yeomanry. Lanyon positioned his gun 3 miles west of Cassel by a farm at le Tom on the D26 where he was informed enemy units were digging anti-tank positions in a copse about one and a half miles to the south-east:

‘I was about to shell the copse ... when two hostile tanks appeared near it. I opened fire and they disappeared into it. I shelled the copse, and waited, and later my No.1 reported that he could see tanks coming down a hedge. At the same time a third tank, which we could not see, opened fire on us from a different area. I engaged the two tanks at 2,000 yards and both were put out of action. The third tank escaped in another direction.’1

Lanyon had very possibly met the advance units of the 6th Panzer Division as le Tom was directly in the path of Johann von Ravenstein’s combat group which was heading towards Cassel from Arques. His local action was just the precursor of the events that unfolded at Hondeghem the next morning when Hauptmann Löwe arrived with 65/Panzer Battalion.

Löwe’s orders were to advance to l’Hazewinde and Poperinghe and crush any resistance he might find en-route. Travelling from Staple he reached the roadblock on the D161 at about 8.15am on 27 May where the leading tanks were fired on by the J Subsection Gun and possibly by the I Subsection Gun which was 700 yards further east on the Rue de Staple. Troop Sergeant Major (TSM) Ralph Opie was at the J Gun position when he observed the German column break across to the fields on their right, moments later the gun came under infantry attack which was initially dealt with by the defenders in nearby buildings. Still under attack from enemy armoured vehicles, the J Gun took a direct hit, killing one of the gun crew and wounding 33-year-old Gunner Reginald Manning in the head and chest and TSM Opie in the head.2

Opie remembered the roadblock was 80 yards further down the road and after the first tank was put out of action he and the surviving members of the gun crew struggled to keep the gun firing before they were overwhelmed and taken prisoner. Manning was sent back to the German casualty clearing station at St Omer where he died of his wounds. There is little detail as to what took place around the I Gun and we can only assume that it was put out of action in a similar fashion before Löwe and his battle group continued their advance along the D161 leaving the remaining two RHA guns in the village for the next wave of German troops to deal with.

The news of the demise of the guns on the main road would have travelled back to the village very quickly and if the sounds of battle had not already alerted Rawdon Hoare to the presence of the enemy, the arrival of IR 4 would have left him in no doubt. The German report of the battle in the village was recorded by Leutnant Kelletat whose account leaves us in no doubt of the determination that the surviving men of F Troop demonstrated in their defence of the village. Kelletat and his men arrived just as the D Troop guns opened fire on the village from their positions on the Mont de Récollets, their targets being relayed from the observation post in the church tower:

‘At around 10.00am our vehicles turned off just ahead of the village onto the byway leading to Hondeghem. As we dismounted, heavy artillery fire rained down on our vehicles from the direction of Cassel ...There was shooting from just about every direction as we entered the village ... I remained with my platoon on the left of the road and advanced a bit further through houses and over hedgerows. Then we ran straight into enemy machine-gun and rifle fire lashing through the hedgerows. We could not see the enemy, but he seemed to have his emplacements everywhere. At any rate an advance towards the centre of the village was out of the question.’3

Kelletat may well have been advancing up the Rue St Pierre towards the L Gun which was firing over open sights down the road. In attempting to cross the road he was slightly wounded by a shell which hit a building just behind him. Hoping to outflank the gun he moved forward again only to be ‘lashed by a sheaf of machine guns fire through the hedgerow’.

The L Gun had been manhandled from its original position in the north western corner of the square and was now firing from the southwest corner at the advancing German units who were attempting to make headway. One of the first targets was the battery cookhouse which had been occupied by the Germans who were busy firing a machine gun from the upper story. One round sealed the fate of the cookhouse and the remains of the machine gun is now a prized possession of the battery. Enemy machine-gun fire was now coming from all quarters and the gun crews were constantly changing position:

‘Both K and L Guns were now hotly engaged, firing at the point blank range of one hundred yards using Fuse 1. So close were the Germans that the gun crews were being bombed with hand grenades, but casualties remained small, only one man having been killed and two wounded. Both guns were in very exposed positions but they maintained a fast rate of accurate fire and every round took effect.’4

It is likely that Captain Jimmy Haggas, commanding B Squadron of the Fife and Forfar Yeomanry, arrived in the village in response to the request for reinforcements although he was under the impression that he was to report to the brigadier! Haggas’ account does not allude to any reaction that Major Rawdon Hoare may have felt about this instant promotion but it must have raised a few smiles at the time:

‘On arrival at Hondeghem we found it occupied by a troop of RHA under Major Hawdon Hoare. Two guns were in action but the other section had been previously knocked out ... I formed a line of men with Bren guns and advanced up some streets in order to clear the village, but found they had withdrawn leaving some dead. I later took out a patrol and sighted a strong force of Germans about 1,000 yards away. This force was composed of heavy tanks and motorised infantry. Two large tanks were also moving down a lane some 300 yards away. Meanwhile the shelling of the village increased.’5

Although the village was in great danger of being enveloped, an element of impatience was creeping into the German assault which had now been held up for at least seven hours by a relatively small British force. Leutnant Kelletat on hearing he was the only officer remaining alive in his kompanie reported back to regimental headquarters where he was told brusquely to take command and ‘mop up the village’. Returning to his men he ordered the observation post in the church tower destroyed and prepared for the final attack.

It would have been around this time that Rawdon Hoare decided the moment to withdraw had arrived, particularly as ammunition was low and there appeared to be little hope of reinforcements. Douglas Williams, in his 1940 account, says the withdrawal took place at 4.15pm when two columns left the village during a lull in enemy activity. The first, containing all the wounded and the two guns, was sent off ahead to rendezvous at St-Sylvestre-Cappel 2 miles to the northeast, with the second, which left a short time afterwards, taking a different route.

At St-Sylvestre-Cappel the column ran into units of the 6th Panzer Division which had already occupied the village. Douglas Williams again:

‘A volley of hand grenades suddenly started from behind the tombstones in the graveyard. Germans appeared on all sides and the troop commander [Captain Brian Teacher] decided they could only be dislodged by the desperate measure of a direct charge. Two parties armed with rifles and bayonets advanced round each side of the churchyard wall, each man shouting as he had been ordered to do, at the top of his voice. A terrible roar went up and the psychological effect was immediately apparent. Three or four Germans were shot and the rest throwing away their rifles broke into a panic stricken rout.’6

Despite both guns coming into action again the writing was on the wall for F Troop as German tanks moved in and destroyed the K Gun, leaving the crew of L Gun to put their own weapon out of action before clambering into the remaining lorries and departing in haste. But the drama was not quite over. One vehicle ended up in a ditch while another missed a turning and hurtled through a hedge into a field, regaining the road only after smashing through a set of railings. Incredibly, with machine-gun and rifle rounds whistling all around them, most of them got away. However, the final word must go to the startled expressions on the faces of the men of C Squadron ERY when they learned F Troop had driven over the very road they had mined with the loss of only one vehicle.

Predictably the casualty figures for the fight at Hondeghem and St-Sylvestre-Cappel were high. F Troop alone lost forty-five men out of the sixty-three that marched into Hondeghem but the majority would have been wounded as apart from the two casualties buried at Cassel Communal Cemetery there are only fifteen men of 5/RHA recorded on the CWGC database who were probably killed with F Troop. To those that survived, the award of the DSO to Major Rawdon Hoare and the MC to Brian Teacher served as an official recognition of the K Battery stand, while the award of the DCM to BSM Reginald Millard and the MM to Gunner Kavanagh, together with the three others mentioned in despatches, was further testimony of the bravery of those who manned the guns and ammunition limbers. Casualties from 5/Battery of 2/Searchlight Regiment are more difficult to find and the CWGC database record only two being killed on 27 May. There is no way of knowing the complete list of German casualties but at least seven men were killed in Leutnant Kelletat’s kompanie.7

It was probably elements of von Ravenstein’s combat group that came up against 133 Brigade after they resumed their advance from Hondeghem along the D161. The 4/Royal Sussex was under the command of another First World War veteran, 42-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Lashmer ‘Bolo’ Whistler, an outspoken individual but one renowned for his outstanding leadership. His battalion had been on the road from Lille since 24 May and was now ordered to defend Caëstre, but quite from whom – or even from what – remained a mystery to Second Lieutenant Peter Hadley in B Company:

‘Why we were in Caëstre at all I did not know. Were we surrounded? It seemed quite likely. I did not even know whether we were operating as part of a higher formation or whether we were a “lost battalion” and I was too tired to care. We were evidently pawns in a game of some sort, and we were not in a position to see the chess board.’8

One thing was certain they were not operating as a ‘lost battalion’. Although the 2/Royal Sussex – which we met briefly south of Hazebrouck in Chapter 10 – had been transferred to 132 Brigade, Brigadier Noel Whitty still had two infantry battalions at his disposal and it was these that were deployed to defend a line running from Eecke in the north to Strazeele in the south, a distance of nearly 4 miles.

At Caëstre Lieutenant Cecil Gould, commanding B Company of the 4/Royal Sussex, held the southern approaches while D Company stretched north towards Eecke. This left C Company to maintain contact with the 5th (Cinque Ports) Battalion, whose line ran down towards Strazeele where Whitty established brigade headquarters. Enemy shelling began on 26 May and continued intermittently throughout the day and night and realising that a German attack was only a matter of time, Whistler sent Private Bert Bleach from D Company 200 yards ahead of the company positions with orders to set up a reconnaissance post:

‘We were given binoculars, a bike, paper and pencil, shovel and pick. We dug a hole or trench in the grass verge where we had good vision for about a mile across flat country, refugees were pouring past all the time carrying a few belongings such as blankets and chairs. We had to take turns at reporting back to battalion HQ on what we had seen. At first it was fairly quiet, but later in the afternoon we saw German tanks and heavy guns parked up and firing in our direction.’9

Bleach and his colleague had seen the advance units of what turned out to be some twenty enemy tanks approaching the south-east corner of the village under cover of an artillery bombardment that Hadley felt had not really stopped since the battalion first arrived. Private Bill Holmes would have agreed with him. ‘We were in dugouts – two per trench. The time came to get our food. My mate asked me should he go or would I? You had to run, crawl and jump to reach the food. When I got back to the trench he was dead.’10

The shelling was not the first occasion this territorial battalion had been under fire but Whistler’s apparent total disregard for the dangers of high explosive material did much for the morale of those present:

‘[We] made no secret of our distaste for this sort of thing and crouched down unashamedly by the side of the road at the whistle of every approaching missile; but the CO merely stood there with his hands in his pockets laughing at us, for all the world as if he were in the Royal enclosure at Ascot. Brave? Most certainly yes – if to be ignorant of fear can be termed bravery. Our brigade commander was exactly the same.’11

As the tanks approached the village the guns of 226/Battery, 57/Anti-Tank Regiment opened up on the leading formation bringing six vehicles to a juddering halt. The remaining tanks withdrew and for the remainder of the day harassed the Sussex with machine-gun fire. Sometime that afternoon Peter Hadley and a fighting patrol from 11 Platoon was sent out by Whistler to deal with an enemy presence believed to be lodged in a farm three quarters of a mile to the west:

‘We were just crossing road when – for the second time that day – I heard a shout of “Tanks!” This time there was not much doubt about it; for simultaneously with the warning came an ominous and unmistakeable rumble close at hand on our right. Never did ten men (and one officer) surmount a seemingly impenetrable hedge with greater speed: for we had no anti-tank rifles and it was without question a time for discretion rather than valour. In a matter of seconds eleven distinctly bewildered human beings were lying scratched and breathless behind the hedge listening to the sound of German tanks blazing away, barely 100 yards from us.’12

Hadley had found his Germans but very sensibly wanted to get a better idea of exactly what he was up against before making any decision as to what action to take. It was while he was keeping the tanks under observation that he and his men stumbled on another group of enemy tanks:

‘One of the German tanks was just the other side of the hedge only a stone’s throw away. There was no sound or movement and I presumed that the crew must be lying up inside in preparation for another move forward. Summoning what little courage I possessed, I crept forward stealthily on my own until I was actually behind the hedge with the tank barely ten yards from me on the other side. My forefinger was crooked somewhat nervously through the ring of a hand grenade and my heart was thumping away like a sledgehammer as I waited for some sign of human movement which would give me my chance. But nothing happened.’13

His anxiety soon turned to relief when he realised he had found six knocked out tanks from the earlier engagement and the ‘terrifying monster which might at any moment turn and spit fire at me was as dead as mutton’. He admits to being somewhat embarrassed as a dozen Germans then advanced towards him with their hands above their heads in surrender. Having handed his prisoners over to an approaching unit of 226/Battery who had been responsible for the ‘dead tanks’, he returned to report to his company commander.

South of Caëstre the 5/Royal Sussex under the command of 47-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Farrah Morgan – known amongst the men as ‘Monocle Joe’ – were dug in around the D947. His battalion was fighting desperately to hold back the German advance which looked to have refocused its assault by attempting to outflank Caëstre to the south and attack the 5th Battalion’s positions along the road to Strazeele. It was a tactic which had not gone unnoticed at Caëstre and Hadley for one ‘had an uncomfortable feeling that the enemy was bypassing the little pocket of resistance that our efforts had provided’. His uncomfortable feeling was exactly right and it was the 5th Battalion that was about to feel the full force of the German attack. Captain Maurice Few, commanding D Company, wrote an account of the battle which, although completed in August after he had been taken prisoner, provides a flavour of the nature of the fighting south of Caëstre.

When D Company arrived at Strazeele at midday on 27 May, Lieutenant Colonel Morgan had been in command for just eighteen days but, despite this, was about to demonstrate his flair for battlefield leadership, skills he had honed since he first saw action with the Border Regiment in 1915. Thinking the road north was clear of enemy, Morgan’s initial orders sent A and D Companies towards Caëstre to reinforce the 4th Battalion, a move that was delayed by a skirmish with enemy tanks which had concealed themselves behind hedges. Caught unawares the Sussex deployed for action and after a short and violent battle lasting some twenty minutes the tanks withdrew leaving behind seven Sussex casualties of whom four were killed.14

It was a taste of things to come but in the meantime the two companies, consisting of less than 100 men, continued north to Caëstre where D Company took up a position on the southern edge of the village with A Company in reserve. According to Few’s account, C Company – which had arrived from the Bois d’Aval – then moved through Strazeele and took up temporary positions at the north end of the village before marching the one and a half miles to the crossroads east of la Croix Rouge where they found B Company heavily engaged and pinned down by enemy machine-gun fire. However, by directing artillery fire from 257 and 258/Field Batteries onto the main road, Lieutenant Ivan Austin, commanding the carrier platoon, enabled B Company to move along the road and dig in.

It had been touch and go but by nightfall on 27 May the battalion was in position on and around the D947 with C Company at la Croix Rouge and the remaining companies strung out along the road towards Caëstre. The next day the battalion came under a sustained attack which began with heavy shelling:

‘An enemy concentration of about 400 infantry was observed on the battalion front. The enemy attacked C Company who, together with 1/8 Middlesex Machine guns and 2 French tanks, assisted in the repulse of the enemy who retired soon after. The whole Croix Rouge area was then heavily shelled, two machine guns being knocked out.’15

D Company came under fire at about the same time and enemy infantry were seen advancing towards them:

‘They were engaged with some losses being inflicted. Eventually enemy mortar and machine-gun fire intensified making the buildings untenable. Fired SOS for artillery support at 5.15pm but without response. The company evacuated buildings and withdrew into the field in the rear, the Germans being about 150 yards away ... Lance Sergeant Pritchard and 2 men were sent back to investigate [the absence of 2/Lt John Hincks] but reported no one left alive in 2/Lt Hincks’ buildings. Troops became restive and made a break for the rear. Captains Few and Hole were finally left with 18 other ranks of B and D Companies and 1 LMG [Bren gun] with a sandbag full of loaded magazines. The field of fire being limited to 50 yards it was decided to take up another position known to Captain Few on the right where some support could be expected from the 4th Battalion.’16

The distressing part of this account is the indiscipline which prompted the majority of men to ‘break for the rear’ leaving their officers to continue the fight with a handful of men and NCOs. Maurice Few and his men were now somewhere on the outskirts of Caëstre – still under spasmodic shellfire – but able to maintain the LMG fire along a fixed line down the road at intervals during the night. But by the time a runner arrived from the 4/Royal Sussex at 1.30am, there were only eight other ranks still capable of fighting. The runner brought word that the brigade was pulling out for Mont des Cats and it was likely they would find their battalion at Flêtre.

In the meantime, back at la Croix Rouge, the beleaguered 5th Battalion was still holding onto its positions but Morgan’s only reserve was the Carrier Platoon under the command of Lieutenant Austin. Battalion headquarters was half a mile east of the village along the Voie Communale Botter Straete with C Company on the forward edge of the village. At 6.00pm on 28 May a runner arrived at battalion headquarters with a message from C Company stating that it had been overrun with heavy casualties and all that remained was Second Lieutenant Waters and a handful of men. Austin was ordered forward with a carrier which came under fire as he approached the crossroads:

‘Lieutenant Austin went forward on foot carrying the Bren gun and a box of filled magazines. At about 200 yards from the village Austin came upon the flank of a German platoon, about 30–40 men were lying along a hedgerow with the commander slightly in the rear ... Lieutenant Austin proceeded to mount the gun on a stone heap and fire through the hedgerow, but before he could complete this a German fired at point blank range by thrusting his rifle through the hedge. The bullet struck and splintered the butt of the Bren gun and passed through his respirator. He therefore came into action forthwith, standing up and firing from the hip. Magazines were expended until the entire German unit became casualties or withdrew. Having satisfied himself the village and immediate vicinity was clear of enemy, Lieutenant Austin reported to that effect to the CO.’17

Austin’s MC was announced in July 1940 and he later expressed amazement that the gun still worked after ‘a bullet ricocheted off the return spring casing in the butt ... After I returned to HQ to report I must have looked a bit shattered, as Major Grant gave me half a tumberful of whiskey with a raw egg in it.’18 That night the battalion withdrew to Mont des Cats via Flêtre where they were reunited with Maurice Few and the remnants of D Company. All Peter Hadley remembered was that it was dark and still as they passed through Caëstre and at one point he caught sight of the brigade staff captain standing on a corner. ‘Twelve hours later’, he wrote, ‘he was a prisoner.’

The CWGC database does not tell the whole story of the number of casualties sustained by the two battalions in the actions around Caëstre. The majority of the battalion was taken prisoner between Mont des Cats and Dunkirk with around 250 officers and men – including Hadley, Whistler and Cecil Gould – managing to get back to England. It was a similar story with the 5th Battalion: Maurice Few’s diary records the strength of the battalion at Mont des Cats as 200 officers and men with at least another 10–15 being captured before they reached Dunkirk.19 Both Whistler and Morgan were awarded the DSO in recognition of the 133 Brigade stand around Caëstre.