Before designing your coop and deciding what kinds of hens to get for your pet urban flock, you will need to know some basic “chicken speak.” If you are anything like me — a suburb-raised, city-loving person — then your general knowledge of chickens is low. Woefully low. It’s nothing to be embarrassed about. After all, over the past 50 years, chickens have receded from common sight in one’s neighborhood, being relegated to the margins of rural life and rare enclaves of animal husbandry. With them went rudimentary chicken facts.

When people find out I have a small flock of chickens, they always ask the same question: “Don’t you need to keep a rooster in order to get eggs?” Though it’s tempting to say something sassy in response, I refrain, because once there was a time when I didn’t know the answer (although I was very young at that time). The answer is no. The only thing you need for eggs is a hen. A rooster is necessary only if you want those eggs to be fertile, producing baby chicks. Besides, city law usually prohibits the keeping of roosters in residential flocks of the cities and suburbs.

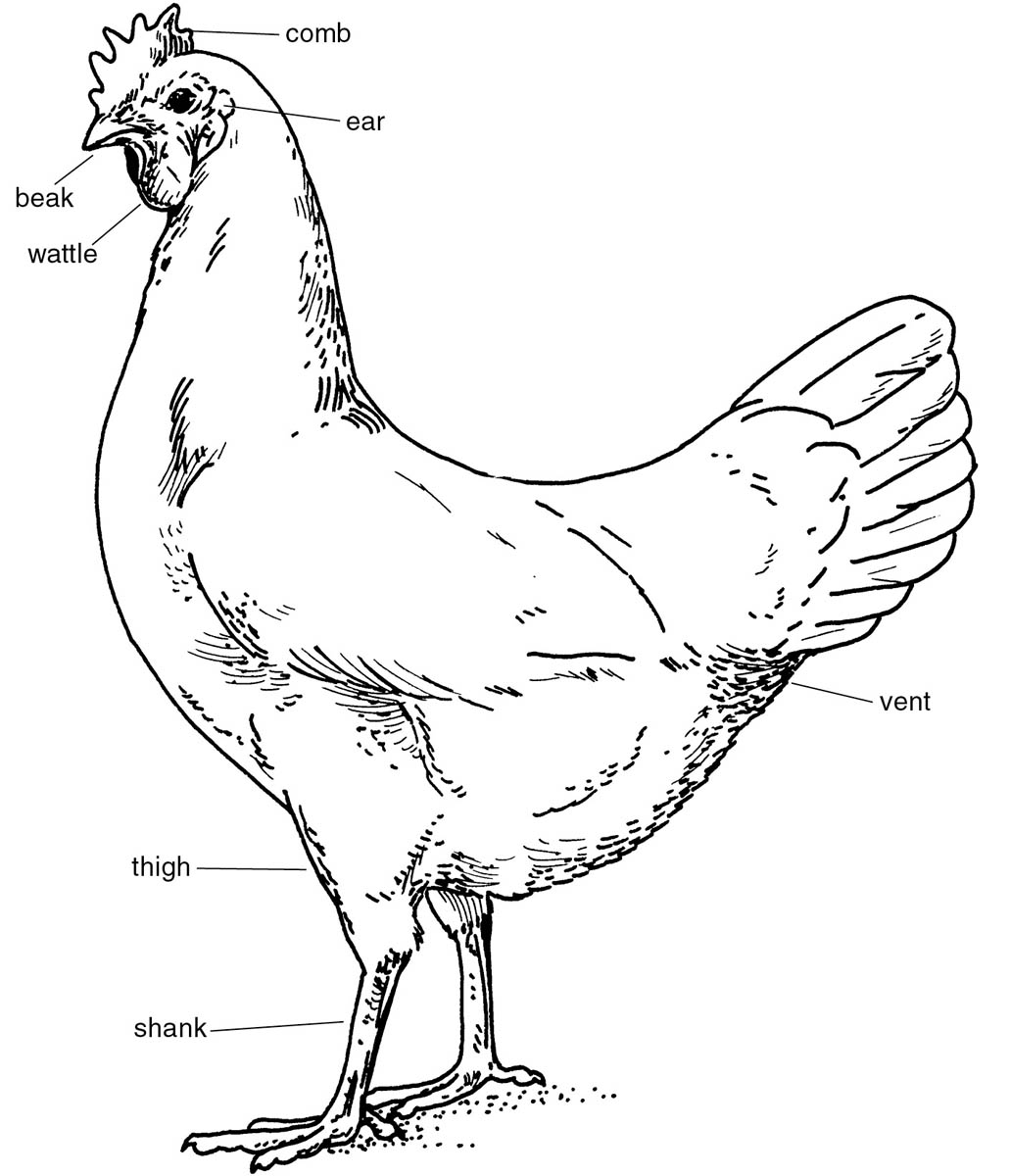

What about those red, serrated “hats” on a chicken’s head — what are those called? Do chickens have shins? Is there really such a thing as pecking order? Before answering these and other frequently asked questions, I will address the oldest and most frequent chicken question of all time.

Hens don’t need a rooster to lay eggs. A rooster fertilizes eggs; he’s necessary for chicks, but not for eggs.

Modern chickens descended from South Asian wild jungle fowl about 8,000 years ago.

Which came first, the chicken or the egg? While the answer to this question is incessantly debated, the origins of the domestic chicken are more definite, though not entirely precise. Scientists generally agree that today’s domestic chicken (Gallus domesticus) had its origins in Southeast Asia between six thousand and eight thousand years ago. At that time in what today would be the countries of Thailand and Vietnam, four types of wild jungle fowl (Gallus gallus) existed. Some scientists (including, in his day, Charles Darwin) believe that the chicken descended solely from the Red Jungle Fowl. Other members of the scientific community posit that more than one of the four wild jungle fowl varieties may have contributed to modern chicken DNA.

Most scientists and chicken researchers agree that chickens were domesticated in India sometime between 4000 and 3000 b.c. These chickens weren’t “chicken” but fearsome flocks of fowl raised by royalty for cockfighting. Because of their aggressive, single-minded focus on combat in the ring, roosters became a symbol of war and courage. Throughout ancient history, battle garments and clan insignia bore the image of a rooster with his head held high and chest puffed out, staring into the distance, unblinkingly awaiting whatever combat should come his way.

Chickens begin to appear in historical and literary references in China, Egypt, and Babylon between 1500 and 600 b.c. Even the Greek playwright Aristophanes referred to chickens in his dramatic works. While Alexander the Great is known for bringing chickens to Europe, the birds may in fact have arrived earlier, accompanying far-traveling trade merchants and wandering soldiers as their primary source of protein on the roads of battle and commerce. It is at this time that chickens forged their role as the first real “to go” meal in recorded history.

The ancient, vanguard chickens gradually evolved into contemporary classes of chickens. From Europe, chickens most likely emigrated to the Americas care of Christopher Columbus in the North and the Spaniards in the South. Once here, chickens became an important source of meat for the inhabitants of and immigrants to the New World.

Poultry popularity came to a head in what is sometimes referred to as the “Golden Age of Pure Breed Poultry.” During the mid- to late 1800s, dozens of poultry clubs sprang up in England and the United States. These clubs guided and influenced the creation of then-new breeds of chickens that remain popular today.

Now that you have some hen history under your hat, it’s time to enhance your cosmopolitan vocabulary with a few choice words about the bird.

Chick. A baby chicken.

Chicken. A type of domesticated fowl raised and kept for meat, eggs, and ornamentation.

Cock. An adult male chicken at least one year old. More commonly called a rooster. Keeping roosters within city limits is usually not permitted.

Cockerel. A juvenile male chicken less than one year old.

Flock. A group of three or more chickens. Most municipal codes permit at least three chickens to be kept per residence.

Hen. An adult female chicken at least one year old.

Pullet. A juvenile female chicken less than one year old. A chick is considered a pullet when most of its feathers have come in and it’s about the size of a husky park pigeon.

Sexing. The act and the art of determining chick gender. The sexing of baby chicks is 90 to 95 percent accurate. Sexing chickens is a highly specialized vocation whose practitioners are steadily diminishing.

Poultry Tribune, circa 1940.

Bantam. A small variety of chickens weighing 2 to 4 pounds (0.9–1.8 kg). Most bantams are miniatures of standard breeds, although there are a few true bantam breeds (e.g., the Silkie and the Japanese bantams), meaning there is no standard breed equivalent. Also referred to as banties.

Comb. The reddish, skinlike “hat” or crown atop a chicken’s head.

Dual purpose. Chickens raised for both meat and egg production. Dual-purpose breeds tend to have calmer dispositions than strictly egg-laying or meat producing chickens do. They lay brown eggs, except for the English Dorking, which lays white eggs.

Oviduct. The reproductive channel down which eggs descend to the vent.

Shank. A chicken’s leg between the thigh and the foot; comparable to the human shin.

Standard. Larger chickens that are medium to heavy weight. Chickens of standard breeds weigh anywhere from 5 to 14 pounds (2.3–6.4 kg).

Vent. The chicken’s bottom end, from which eggs and waste descend.

Wattles. Those red, fleshy, dangling muttonchops on either side of a chicken’s beak.

Basic chicken anatomy

Chicken run. An outdoor area within the coop that provides a protected place for chickens to freely wander about; the equivalent of a dog run.

Coop. An enclosed area for chicken habitation that contains a chicken run and a henhouse.

Feed. Chicken chow. There are different formulated feeds for chicks, pullets, and hens. Chick food can be medicated to prevent possible disease. Pullet food helps chickens grow and put on weight. Hen feed, also called laying feed, contains calcium for strong eggshells. Never feed hen food to chicks — the jolt of calcium in younger fowl can damage their kidneys. Start giving laying feed to pullets when they are around four to five months old, right before they begin to lay eggs.

Henhouse. A shed or other small structure located within the coop where chickens sleep (roost) and lay eggs; the equivalent of a doghouse.

Nest box. A cozy, private cubicle in the henhouse where hens lay their eggs.

Perch. A small ledge affixed to an interior wall in the henhouse that hens roost (sleep) on. Hens like to sleep about 2 to 3 feet (60–90 cm) off the ground.

Scratch. The chicken equivalent of a snack. It’s a mix of grains and cracked corn. Give it to your birds in addition to, and not instead of, fortified, enriched hen or pullet feed.

Brood. A hen sitting on her eggs to try to hatch them.

Dirt bath. Chickens’ instinctive act of cleansing away and killing mites or parasites by digging a shallow hole, lying in it, and kicking up dirt onto their entire bodies. After a dirt bath, some chickens lie motionless and appear dead — they are relaxing after their satisfying “spa” treatment.

Lay. To produce an egg.

Pecking order. Social ranking of hens established naturally within the flock.

Preen. To run the beak through the feathers to clean and arrange them.

Roost. A chicken sitting on a perch to sleep at night.

Poultry Tribune, circa 1940.

Over the years, I’ve been asked all kinds of questions about keeping chickens in the backyard. While some questions are . . . well . . . unique, to put it mildly — Question: Can I walk my chicken on a leash in the park? Answer: Only if you want to attract a pack of wild dogs — most folks seek more ordinary information. The following are some of the most commonly asked questions about chickens and keeping them in the city.

Do I need a rooster for my chicken to lay eggs?

No. Pullets and hens lay eggs without a rooster. A hen’s natural plan is to release several hundred eggs during its lifetime. You need a rooster only if you want the eggs fertilized for the purpose of having chicks. Nearly all cities have ordinances against keeping roosters, because they are noisy. Contrary to popular belief, roosters don’t crow just at sunrise — they crow all day long, frequently and loudly.

How long do chickens live?

Depending on several factors — including your chickens’ health, diet, and heredity — the average life span of a happy hen is eight to ten years. Chickens have been known to live up to twenty years, though this is an exception.

When do chickens start to lay eggs?

When they are about five months old. I’ve had hens start laying as early as four months and as late as six months of age.

How long will a chicken lay eggs?

A hen’s first two years are her most productive; she will lay nearly every day. Thereafter, egg laying slows down each year. We’ve had hens that laid eggs until they were 12 years old, albeit one per week. And I’ve read of a chicken (a Rhode Island Red) that laid into her seventeenth year! Most hens will keep on laying until their old age and demise, although they won’t produce as many eggs as in their youth.

Chickens live about eight years, though some keep clucking for twice that long.

Hens start laying at about six months. They lay the most eggs during their first two years.

What do you do with a chicken that no longer lays?

Old hens just don’t lay as much as young hens. That’s okay, because your hens are family pets, not objectified egg-laying machines. Your hen’s gradually (and naturally) diminishing egg-laying capabilities are no reason to expel her from her flock and your home. As with all pets, you have a responsibility to keep and nurture your hens until their natural demise. If you don’t think you can commit to your chickens through times of many and scarcely laid eggs, then don’t get a flock.

When your senior chicken does finally expire, you can get another chicken or chick. Raise the chick separately from any remaining adult chickens in the original flock. Gradually, and with supervision, introduce pullets into the adult flock. Chickens are social birds and need to warm up to new flock members.

In the event that your love for your chickens was superficially related to the amount of eggs they laid and you don’t want to keep your nonlaying hens, you have a few choices.

Your first choice is to eat your chicken. It’s not a choice that everyone would make, but if you don’t mind, then why not? This way, you don’t subject others to your unwanted chickens. Although I don’t think I could eat a chicken that I’ve named and that has been following me around the yard for years, chicken farmers and others who raise large numbers of (unnamed) hens butcher and stew their chickens once the best of their egg-laying days are over. Stewing is the only way to cook an old chicken. Chickens over the age of one or two years don’t provide the tenderest meat. Chickens raised for meat, like broilers — yes, they really are called that — are killed for meat when they are only six to eight weeks old. There really is something to the saying about “tough old birds.”

If you don’t want to keep your senior chickens but don’t want to eat them either, put an ad in the paper offering them to a personal party or a petting zoo. There is always a chicken lover out there who may be able to squeeze another beak into a henhouse or flock.

Do not ever dump your chickens in the woods, in the park, or at veterinarians’ offices. Not only is this irresponsible, but it also is cruel to the helpless birds. Your chickens, like all household pets, deserve better.

Poultry Tribune, circa 1940.

What do chickens eat?

Chickens eat chicken feed, which is available at feed stores. Chicks and pullets that are not yet laying eggs should be given nonlaying feed; hens that are laying should be given laying feed. The difference between the two is that laying feed contains calcium, which is necessary for strong eggshells. Nonlaying feed does not contain calcium, because it can harm the kidneys of immature chickens. When pullets are ready to begin laying eggs, they graduate from nonlaying to laying feed. Chickens also eat grit, gravel or small stones that aid in the digestion of food.

In addition to the formulated chicken feed and grit, chickens love to eat fresh fruits and vegetables, like apples, melon, grapes, lettuce, tomatoes, corn, and spinach, and breads and pastas. My hens are crazy about cottage cheese; a spoonful (low salt or unsalted) lures them into the coop every time! Not only has our household food waste diminished to zero, but all the good food that goes into the chickens makes the eggs sweeter.

While you can give your hens vegetable leftovers and discards (like the outside leaves of a lettuce head), do not ever give them spoiled food. Also avoid giving your chickens any food that might add strong odors or flavors to their eggs, like cabbage or garlic.

For a complete roundup of chicken nutrition, see chapter 7.

Do chickens have teeth?

No, they don’t. Their beaks don’t do the chewing — their gizzards do. When a chicken eats, food goes into its crop, a pouch in the throat that holds food. The crop delivers food to the proventriculus, or true stomach, where hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes are added. Finally the food passes to the ventriculus, or gizzard. The gizzard is a muscular pouch that contains grit. Grit acts like a masticating agent, mashing up the ingested food.

Do I have to bathe my chicken?

Not unless you really, really want to — and I can tell you from personal experience that the chicken will not want to take a bath. Chickens are hard enough to hold still under dry conditions. Try holding them still during a warm bath and blow dry!

Mother Nature takes pretty good care of hen hygiene. Chickens keep clean through preening and dirt baths. A dirt bath removes any mites from a chicken’s feathers. Preening removes fine particles of dirt and dust. However, chickens participating in a poultry show are bathed and groomed so that their natural good looks shine even more in the ring. Unless you are showing poultry or your chickens have shown an affinity for water, I’d refrain from bathing backyard hens. The chickens in your urban flock aren’t going anywhere, so they don’t need to get gussied up. Plus, a wet chicken is susceptible to colds.

Hens are female adult chickens. Pullets are female chickens less than one year old.

Buy baby chicks only from reputable feed stores on online hatcheries.

Can chickens catch colds?

Yes, they can. If you see that your chicken has the sniffles or is sneezing (yes, chickens sneeze), mash up a clove of fresh garlic in some cottage cheese or other goody that your chicken loves. You can also mix a teaspoon of fine garlic powder into a gallon of your chickens’ drinking water, but that way, all your flock will be drinking the remedy. The garlic won’t hurt them, but it may imbue your hens’ eggs with a strong, distinct scent and/or flavor. If your sick chicken fails to make a comeback after a few days’ worth of the garlic treatment, review The Chicken Health Handbook, by Gail Damerow, for more information.

Can chickens get frostbite?

Yes. Although chicken feet are quite resilient against frostbite, the wattles and comb are susceptible. So keep your chickens out of the wind and snow. The smaller the chicken, the more vigilant you need to be about keeping it warm in cold weather.

Do chickens have good eyesight?

Yes. Sight and hearing are a chicken’s two best senses (besides their sense of humor). They find tasty bugs and grubs by seeing them crawl around in the dirt, or hearing them shuffle under leaves or grass. Chickens don’t have a great sense of smell or taste, which perhaps explains why they think worms and beetles are delicious.

Do chickens make good pets?

Yes, absolutely! People keep all kinds of birds as pets: parakeets, canaries, cockatiels, parrots. Why not keep chickens? They are no more difficult to care for than any of these birds, or any other pets like dogs, cats, or fish. Keeping typical farm animals in a personal residence is nothing new — remember the miniature potbellied pig craze of the 1980s? Sadly, the attraction to pigs in residence went belly up a short time later. Very few true miniature pigs were sold to a pig-loving public. Most folks were in possession of a basic, generic pig that grew to 300 or more pounds within a year. The public reeled from Big Pig Shock. We cooled off toward farm animals as pets, and rightly so. Pigs, like most farm animals, didn’t work out because they are simply too large and require too much care and space from a typical city dweller.

Yet a pet-loving public would not be deterred from taking chickens under their wing. Chickens aren’t large. Chickens aren’t difficult to care for and maintain. And chickens are cute. For these reasons, it was only a matter of time before we invited chickens into our city and suburban neighborhoods.

And while they do make great pets, we are talking outdoor pets, not indoors. Chickens cannot be housebroken. While my hens would love to come in to the house and watch “Animal Planet” on TV, I don’t let them in because of their indiscriminate waste elimination habits (in other words, they poop anywhere, anytime, all the time). However, I heard of one chicken lover who kept her pet chicken indoors and controlled the relentless droppings by making the chicken wear a diaper (no lie!).

Are chickens smelly?

This is an understandable concern in any community, particularly those where houses sit close together. The answer depends on the chickens’ owner. Chicken coops that are not properly and adequately cleaned at least once a week will start to develop that barnyard smell. If you follow the simple guidelines for coop care described in chapter 7, you will be able to proudly say, “My chickens don’t stink!”

Are chickens dumb?

While chickens don’t grow up to do quantum physics or govern small countries, they are not stupid. Their intelligence is relative to their species. They are, after all, birds. They aren’t as smart as an African Grey parrot, but they hold an MBA when compared to a common finch. Chickens also do quite well in learning to respond to certain stimuli. My chickens have learned all manner of things. When they hear the back door open, they know to run to the coop gate to greet me. When I call “chick chick,” they come running, because they know I call them over to personally hand out special food treats. Or when I tap my fingers on the picnic table, they jump up onto the tabletop looking for imaginary goodies.

Can a chicken love you?

Yes — sort of. Although nature didn’t equip them with the same capacity for affection as a cat or dog, chickens do show fondness, in their own way. Just walk outside with a dish of scratch or cottage cheese and watch the chickens lovingly run right up to you. Okay, so chickens love you for the food, but that’s something, right? My chickens like to sit with me on the arms of my outdoor chairs, just hanging out and preening awhile. To me, that’s love.

Where’s the best place to buy chickens?

At your local feed store or on-line from a reputable hatchery. You can also obtain all your henhouse equipment and supplies there. Most feed stores carry the most popular purebred chickens, such as Barred Rocks, Rhode Island and New Hampshire Reds, Austra-lorps, and Orpingtons, and a few of the recently available commercial hybrids, like Red Sex Link and Black Sex Link chickens. If you are just starting to keep a small flock, you can get advice from the feed store employees or from the hatchery web site (usually great sources of basic chicken information), or you can buy one of the many books (like this one) they all have available.

On-line feed stores and hatcheries have a terrific variety of breeds available. The downside to ordering your chicks from an on-line breeder or hatchery is that sometimes a minimum order of chicks is required — between 10 and 50 — which far exceeds the number of chickens that residents are permitted to keep. This trend is gradually changing, as some hatcheries are responding to the resurgence of small backyard flocks. Some on-line hatcheries let you order just one chick in a breed, if desired. Unfortunately, ordering chicks by mail carries the morbid risk of finding one or more chicks dead after the ordeal of cross-country shipping. Reputable hatcheries have guarantees to prevent or resolve that occurrence.

Can you keep chickens in urban areas?

After all this, you’re still asking? City chickens are marvelous! Most city codes permit keeping several chickens in residential areas. They are easy-to-care-for pets that provide your family with fresh, organic eggs. They are part of the recycling and compost chain in your garden. And for you and your family, friends, and neighbors, chickens provide hours of fowl amusement!

Do you need a permit keep chickens?

Depends on where you live and the number of hens you intend to keep. Municipal codes in some cities and towns do not require a permit unless you want to keep more than three chickens. To apply for a permit, you may need to obtain the signatures of all residents within a certain distance of your coop, which evidences their consent to your keeping a small flock of chickens. See chapter 4 for more information.

Where can I learn more about chickens?

I’ve listed various print and Internet resources at the end of this book. Over the past few years, the best book I’ve seen about chickens (besides this one, of course) has been Storey’s Guide to Raising Chickens by Gail Damerow.

If you are like me, the more you learn about chickens, the more you’ll want to know. One day, without your realizing it, your chicken illiteracy will have transformed into chicken enlightenment!