So, you picked out your chicks. Now they’re home with you, still bundled inside a dark cardboard box punched with ragged little breathing holes, frantically peeping. They want out — now! What do you do?

Well, what you should have done before bringing the little ones home was set up their living quarters. No, not that spacious coop you’re building or have finished building out in the backyard. You need something smaller and cozier for the chicks until they are mature enough to tolerate being kept outside. You need a brooder.

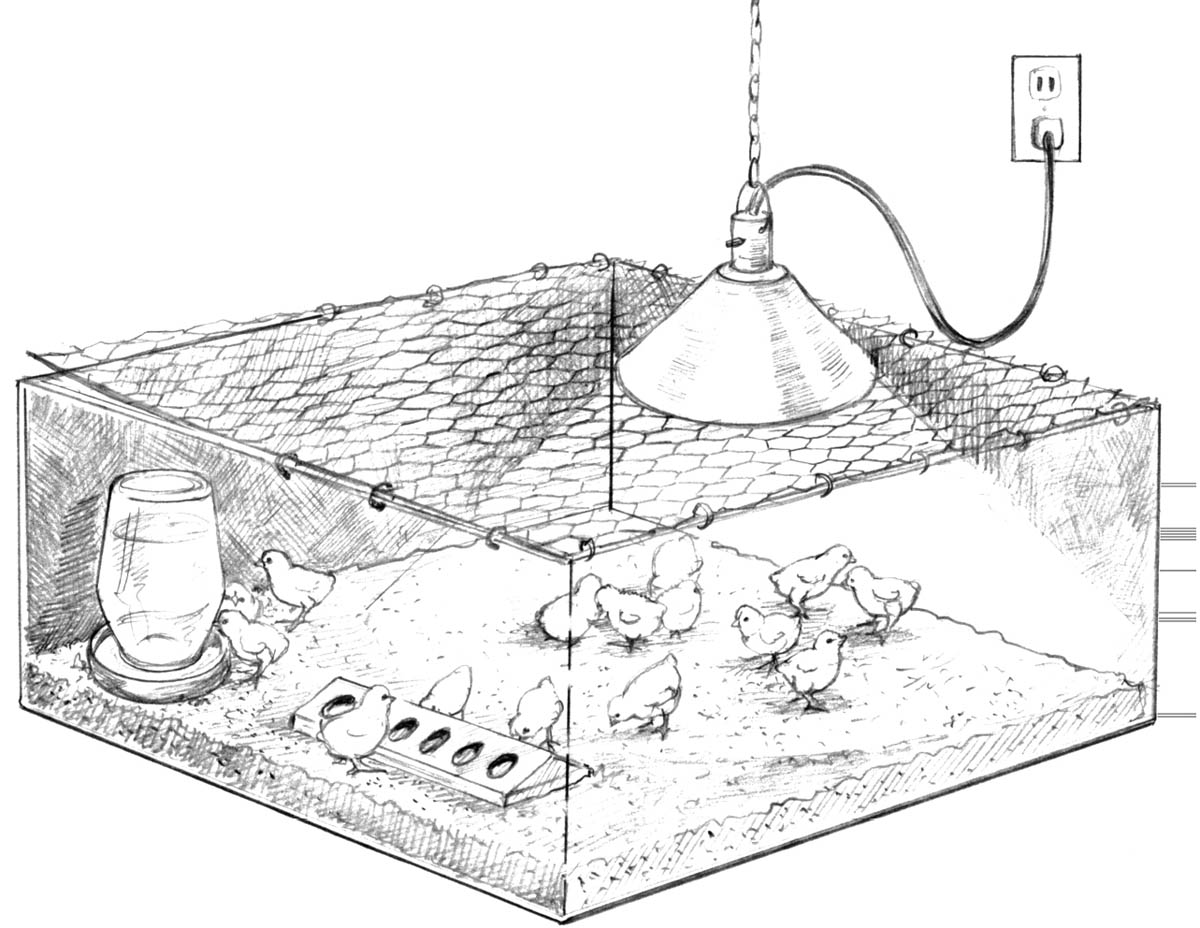

A brooder is a wire cage or some other type of ventilated box equipped with an overhanging light source for warmth. Some folks use old aquariums or wood boxes, but I prefer a large wire cage specifically made for the purpose of raising a few baby chicks. These cages or brooders are available at your local or on-line hatchery or feed store. Keep the brooder on a table or countertop in your basement, garage, or spare room while your chicks occupy it. You want the baby chicks close by to monitor them.

Ensure that no drafts will disturb the brooder. A great quick windbreak for a brooder can be as simple as newspaper folded lengthwise into 4-inch (10 cm) strips and taped around the bottom of the cage.

A brooder should provide water, food, warmth, quiet, and security for your new chicks.

A typical brooder cage has a wire floor and sits on top of a removable metal pan for easy cleaning. Lift the cage, line the pan with newspaper, and replace the cage atop the pan. You will need to remove the soiled newspaper and replace it with fresh newsprint at least once daily, or else your chicks will start to stink. Chicks are, and remain throughout their lifetimes, prolific poopers. I always clean my chicks’ brooder twice daily; in the morning after the chicks have had a long night to themselves to sleep and poop, and before my bedtime, so the chicks can rest in clean premises. Just because you’re raising chicks doesn’t mean you want your spare room, garage, or basement to smell like a barnyard!

Put some old rags, towels, or socks on the cage floor. Chicks don’t roost on a perch the first two or three weeks of their life. They fall asleep on the floor where they are standing, eating, or pooping. The rags give them something soft to fall asleep on. Use rags you won’t mind throwing out. Once the chicks sleep (and, of course, poop) on them, you’ll want to throw them away and replace them with fresh sleeping rags daily. Make sure the rags don’t have loose threads on them or the chicks will try to ingest them, which can harm the chicks. I found that old socks are best to use for chick bedding — they have few loose threads and fibers that the chicks can pull on and consume.

After the chicks are a month old, you can place wood shavings on the bottom of the brooder cage. Do not use wood shavings before that first month is over, however. Baby chicks don’t know what’s what yet — in the course of experimental tasting, they will try to eat the shavings. If they do ingest wood shavings, their digestive system may become blocked up (known as pasting up), and the chicks may become very ill and die.

Chicks live in their brooder, a roomy cage equipped with a heat lamp, until they are fully feathered. They are now called pullets; when they are one year old; they become hens.

Suspend a heat lamp 6 to 8 inches (15–20 cm) from the top of the cage. The temperature in the cage should start out between 90° and 95° F and should be decreased by five degrees each week for the next five to six weeks. Put a thermometer on the cage floor to determine whether to move the heat lamp higher (to lower the temperature) or lower (to raise the temperature).

Don’t hang the lamp dead center over the cage, but over to one side. You need to give the chicks room to escape the lamp if they are feeling too hot. You will want to regularly observe and regulate the heat so that you don’t accidentally roast your chicks. If the chicks are always huddled together directly under the lamp, the brooder temperature is too cold. If the chicks stay as far away from the lamp as they can, clinging to the walls on the opposite side of the brooder, the temperature is too warm.

Your chicks need to have plenty of cool, fresh water to drink. Put the chicks’ water dispenser in the cage over to one corner, away from the direct path of the heat lamp. If the water in the dispenser becomes too hot, the chicks will not drink. Chicks’ fragile physiques are susceptible to immediate dehydration without access to fresh, cool drinking water. Discard the water from the dispenser and refill it with clean water twice daily. The chicks poop everywhere, all the time, and they make no exceptions for their watering tray.

Place a chick feeder in the cage. The feeder is usually a stainless-steel feeding dish, though plastic feeders are available (plastic is a bit easier to clean). The feeders can be either a shallow round dish with a top cover containing several half dollar–size holes, or a narrow trough topped lengthwise and center with a rod that turns in place. The purpose of the holes in the round feeder and the teetering rod in the trough feeder is to keep the chicks out of their food dish. Without the protective top and rod, the chicks, not knowing any better, would stand in their dishes and poop and sleep.

A chick feeder gives chicks access to their feed while at the same time keeping them from getting into the feed.

What goes in the chick feeder? Chick feed, of course. Chick feed has a unique nutritional makeup designed just for growing chicks. Chick feed is ground up so that it’s easy for the chicks to eat and digest. It comes in two forms: “mash” and “crumble.” Mash and crumble each look like their name implies. Commercial prepared chick feeds, which are available at feed stores, have all of the necessary nutrients needed by your chick flock.

Chick feed comes in two varieties: medicated and nonmedicated. Medicated feed prevents chick coccidiosis and is essential in larger farm flocks of chickens. However, with only three or four chicks, you have control over the cleanliness of their habitat. Disease in your small flock is not as likely to occur as in larger, farm-size flocks. I’ve always raised my city chicks on nonmedicated feed and have never lost a chick to sickness.

Poultry Tribune, circa 1940.

When your chicks are about three weeks old, install a small perch or dowel into one end of the brooder. Your fledglings need to practice roosting much like a kid needs to ride a tricycle before trying out a bike. Placing a dowel into the brooder early in their lives encourages the chicks to give roosting a chance. If you see that the chicks aren’t getting the idea to jump up on the perch themselves, give them a hand. Pick them up and hold them over the perch until they grip it. Gently let go when they do. They will fall over a few times, but like a kid on a bike, once they learn how to roost, they’ll never forget. And there’s nothing cuter than several-weeks-old chicks, still all fuzzy and peeping, clustered on the perch together!

Put the chicks in the brooder as soon as you bring them home. Promptly give them water to drink. Initially, mix a little sugar (1 teaspoon per quart) into the water. This mixture gives them instant energy and helps reduce their stress level (imagine being locked up and bounced around in a dark cardboard box for a while). A little serving of sugared water is especially important if you have received your chicks by mail, as they will be thirsty and stressed from their long journey. Once your chicks have had some time to adjust, provide them with fresh water without adding sugar. The sweetened water is a one-time serving to the chicks and should not be continued after the first watering.

The first day and night with the chicks will be magical. Well, it’s magical for the people; I imagine the chicks have a different take on the experience. They are frightened, awestruck, and totally dependent on you. They are fuzzy, clumsy, and curious. They are full of life but weigh little more than a heavy paper napkin.

Your new chicks will look fragile and wobbly. Their tiny claws will fall through the holes of the wire flooring. Don’t worry — chicks are actually tougher than they look. Soon they’ll get stronger and more accustomed to their new home. In just a day, the baby chicks will be running from side to side and over the wire flooring without losing a step. They will eat, drink, and sleep like old pros.

And they will peep. They peep all the time like chatty canaries on caffeine. They peep when they eat. They peep when they poop. Peep when other chicks are peeping. Peep when no one else is peeping. It is a veritable peep show (bad peeping pun indeed). They stop peeping only when they sleep, which they do suddenly without warning. Sleeping comes naturally and abruptly to chicks. To sleep, the baby chicks simply fall down wherever they are standing and peeping, and they close their tiny chick eyes.

I’ll never forget the first time I held a baby chick. It was — what else — magical. The chick got really warm in my cupped hands and fell asleep with her tiny head resting on my fingertips. The first time I saw a chick asleep in the cage, I had such a scare. I thought she was dead. She was lying face down, wings slightly opened and splayed away from her body, looking lifeless. I tentatively touched her through the wire and she popped up, peeping, and ran to the food tray while pooping. Whew. If you see your chicks lying this way, don’t panic. They may scare you to death the first time you see them lying there on the bottom of the brooder like a cottonball carcass, but they are probably just taking a quick nap.

Get used to seeing your chicks sprawled facedown in the poultry power nap position. They spend most of their first few weeks either sleeping or eating. The abundant rest and food fuels the chicks’ physique through an amazing growth spurt. They’ll go from a few ounces to a few pounds by the time they’re eight to fourteen weeks old.

When can the chicks move out to the coop? Depending on their breed and variety, chicks will be ready to begin their pullet rite of passage out of the brooder and into the coop at anywhere from three to four months of age. The basic rule is: Wait until your pullets have all their feathers (that is, they’re fully feathered) before moving them out to the coop.

The move to the coop should be undertaken gradually. Think of young pullets as greenhouse seedlings. Seedlings raised indoors are never brought out and immediately thrown into the soil. Instead, they are gradually acclimated to the outdoors over a brief period (known in gardening parlance as hardening off). It’s the same for your young chickens. When the weather has become consistently warm, take the birds outside in their brooder. Leave the brooder in the henhouse for a few hours, then bring it back inside for the night. Repeat the next two days. On days three through six, open the brooder and let the pullets wander freely around their new digs, but continue to bring them in for the night.

After a week of this careful treatment, your pullets should be accustomed to the temperature and décor change in their habitat. Having had a chance to scratch in the dirt and eat bugs, they’ll be itching to move into their new abode. Let them.

Nobody wants a sick chick. Once a baby chick is sick, its chances for survival are not as good as if it had remained healthy through its chickhood. The best cure is prevention. First, pick chicks that aren’t already sick. See chapter 6 for more information about that. Second, keep the cage clean, provide the chicks with fresh water twice a day, and keep an eye on their behavior. I bring lawn chairs into the basement where my chicks live and sit and watch them a little bit each day. By getting accustomed to your chicks’ looks and habits, you are more likely to become aware of anything that doesn’t look right.

Poultry Tribune, circa 1940.

Possible signs of discomfort or illness in chicks may include watery eyes, waterier-than-usual droppings, listless behavior, and not eating or drinking. Chicks (and chickens) are susceptible to waste-borne disease and bacteria. If you are really watching your chicks, you’ll notice that they walk around their cage pecking at and tasting big bites of their own droppings (remember, chickens do not have good senses of smell or taste). Keep the cage very clean to decrease the chicks’ chances of consuming their own waste.

By watching your chicks carefully each day, you can pre-vent problems before they happen. An uncared for, unwatched chick could die from simply pasting up (see below). How will you know if your chicks are unhappy for some reason? You will hear them. They will peep and cheep more incessantly than they usually do. They may have run out of water or food (they never should). They may be too cold or too hot. Perhaps they are pasting up or just not feeling well. Watch your chicks diligently the first few weeks of their lives. They are pretty much helpless and rely totally on you for their food, water, warmth, and health.

If your chicks are ill and home remedies are not helping, you can call the feed store where you purchased them for some advice, or contact a local avian veterinary practitioner.

Pasting up occurs when a chick’s droppings cluster up and adhere to its behind (the vent), preventing the chick from passing new droppings. It’s the chicken version of constipation. A chick can paste up if it eats cedar shavings (a good reason not to use them for bedding) or if it doesn’t have enough water to drink (chicks and chickens drink surprisingly large quantities of water).

If you see that a chick is pasting up, pick it up and use a damp, warm washcloth to gently remove the material from the chick’s rear end. Try not to get the chick too wet with the washcloth or it can catch draft and a cold.

Watch your chicks daily to make sure they are clean and happy. Pasting up can cause your chick discomfort or, if not promptly noticed, death.

When your chicks start to resemble fat, feathered pigeons, they are no longer chicks but pullets. They will be pullets until they are one year old. Then they’ll be hens. Pullets and laying hens have different feed needs than do chicks. You can get all the feeds necessary for your chicks, pullets, and laying hens at your local feed store.

The bigger chickens are, the more feed they eat. Those little chick feeders aren’t going to do the job of feeding your ravenous pullets and hens. To keep food plentiful and always available, use a galvanized stainless-steel cylindrical feeder. These can hold several pounds of feed. Suspend the feeder from the coop or henhouse rafters so its lip is about even with the flat of your chickens’ backs when they are standing. Keeping the feeder raised helps keep the food in the dispensing tray clean.

You will also need a larger waterer for your chickens. Chickens are thirsty birds. How thirsty? The Girls can easily go through a gallon a day. They drink even more on hot days. Install a 3- or 5-gallon (11 or 19 L) plastic or galvanized steel waterer in the coop or henhouse. As with the feeder, suspend the waterer so that it is as high as your chickens’ backs. Keep the water dispenser in a shady area to keep the water cool and fresher longer. Check the water level in the waterer every day to make sure your chickens haven’t tilted it and caused it to leak and spill out. Refill or refresh the water as necessary.

Pullet feed is basically hen feed without any calcium additives. Calcium makes for strong eggshells. Give your chickens pullet feed until they are about four to five months old. At about this time, the birds are fully feathered, their butts are really fuzzy, and their legs and hips seem to spread farther apart so that they have a bell-bottomed shape. When your hens’ bottoms start spreading, it means your girls are near egg-laying time.

As your pullets transition into henhood, gradually mix in hen laying feed (the one fortified with calcium) with the remainder of the pullet feed. The laying feed is made up of larger pellets than pullet or chick feed. Give your hens time to get used to this — at least two weeks — by mixing the adult laying feed into the remaining pullet feed in increasing increments until all the pullet feed is gone. By that time, your hens will have laid their first eggs.

Once your chicks have become pullets, introduce grit into their diet. Grit is gravel or small rocks pullets and hens need to eat, along with their chicken feed. Why? Because chickens don’t have teeth. Think of grit as the only “teeth” the chicken has to chew its food. When a chicken eats, food goes into the crop first. The crop is like a chicken’s initial stomach — it doesn’t digest food, but merely prepares it for its imminent journey down the gullet and into the gizzard.

The gizzard is a chicken’s muscular “second stomach.” Grit joins ingested food in a chicken’s gizzard. While the gizzard undulates like a flexing and relaxing muscle, the grit gets tossed around with the food, which gradually mashes up all the food for subsequent digestion. Without grit freely available to your hens, they will not digest their food properly and they may become ill.

Keep about a small cup of grit available at all times in a sturdy container that won’t tip over. I use a clean tuna or cat food can posted on top of a wood stake in the ground. (I remove the label, punch a hole in the bottom of the can, and screw it into the stake.)

Chick feed comes in mash or crumble form and does not contain any calcium.

Teach your chicks to roost by regularly holding them on their perch; soon they will learn to balance.

Keep chicken feed clean by storing it in a large, resealable plastic container. I use two large trash barrels: one with the open bags of feed and scratch stored inside, the other for the unopened bags of feed and scratch. Storing the chicken feed and snacks in water-tight, vermin-resistant containers lets me keep the food near the hungry hens, out back behind their coop.

Poultry Tribune, circa 1940.

If you really love your chickens, give them scratch. Scratch is a mixture of cracked grains and corn. It’s sweet, fattening, and delicious — like caramel corn for chickens. They go crazy for it.

Scratch is a good snack for chickens, but it should never be substituted for the daily laying feed. Scratch contains a lot of corn, which is high in fat and low in protein. Your hens need at least 16 percent protein in their diet each day, which they’ll get in the prepared hen feed, but not solely from scratch.

Since scratch is high in fat, I dish it out to the Girls before they roost in the evenings. I tend to give them a little more scratch in winter, so they’ll have something in their gizzards to keep them warm on our cold Northwest nights. Feeding your hens too much scratch will make them fat — too fat. Plump hens are happy hens, but obese hens are susceptible to health problems.

When feeding your chicken, think in terms of variety. A chicken is what a chicken eats. Would you be healthy if you ate nothing but pepperoni pizza for breakfast, lunch, and dinner? Happy perhaps, but not healthy. It’s the same with chickens. In addition to prepared chicken feed and occasional scratch snacks, they need some variety in their diet. They especially need greens and vegetables. If you can’t let them out in the yard often enough to nibble on your lawn, or if you have no lawn, toss some greens into the coop every day. Chickens can have even wilted greens and produce, so long as they are not spoiled.

I like to give my hens some fresh greens each day, together with a few pieces of fruits or vegetables. When lettuce and corn are on sale, I always get extra for the Girls. I also am fortunate to have a wonderful neighbor who works in a grocery produce department and brings the Girls tasty, fresh, and otherwise wasted greens and vegetables.

Chickens love to eat breads and starches, like rice and pasta, but take it easy on the portions you give them. Excessive amounts of grain products can make your poultry portly. Small bits of bread treats are fine. For instance, I don’t like eating the heels on a sliced loaf of bread. Guess what? The chickens aren’t as fickle as I am — they love the bread heels! When I have leftover rice or pasta that does not merit storing in the fridge, I toss it into the coop with the greens and vegetables.

When I want to really give my chickens a savory treat, or when I need to bribe them back into their coop, I bring out the heavy artillery: cottage cheese. I swear, the Girls would hold their eggs ransom for that cottage cheese if they could. And it’s not only a proven bribe but also is full of vitamins and is a great source of protein. Once a week, I’ll put out about a half-cup of low-fat, no-salt cottage cheese for the Girls. Why is low- or no-salt cottage cheese best? Because chickens already get whatever salt they need in their prepared feed. The Girls are on prepared feed because it has exactly what they need for optimum and balanced nutrition. Too much salt in their diet will not only make chickens thirstier than they already are, but it can also affect their laying and health (nobody wants a hypertensive hen!).

Feed your chicks not only chicken feed but also greens, fruits, and vegetables. They love the variety, and it will make their eggs rich and luscious.

The coop is built. Your darling chicks have grown into pullets, which have matured into hens. The hens have been eating and drinking like queens. In fact, they are starting to look like King Henry VIII on chicken legs. So what’s next? The moment we’ve all been waiting for — the eggs!

Eggs for cakes, cookies, quiche. Eggs for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. So many eggs that I have to give them away to grateful relatives, friends, and neighbors. Everyone I know was as excited about those first eggs as I was. In a funny way, eggs seem to bring people together. It did in my family and circle of friends, and it will for you and yours.

Once your hens start laying, people by the dozen come out of the woodwork, humbly pleading for those fresh, backyard jewels. Walk a balanced line so you don’t deny anyone your backyard eggs, but do not overindulge anyone, either. While true largesse is giving away one or two dozen eggs at a time, dole out those gorgeous, yolky gems frugally, a half dozen at a time. This is not to be stingy, because you will have more than enough eggs for yourself even if you give half of them away. The parsimonious passing out of the eggs as a sort of continuing ransom will ensure a steady stream of egg-craving friends and visitors for your chickens.

When the Girls were about five months old, an informal “egg watch” began and was ongoing nearly 24 hours a day until the first egg was dropped. The phone would ring. The dog would bark as neighbor after neighbor stopped at the front door. Over and over, the question: “So . . . uh, any eggs yet?” When one of the Girls laid an egg the first time, everyone got a phone call (known in our family as the Egg Call).

Lucy began to lay at almost five months, and Whoopee and Zsa Zsa kicked in at five and a half months. Lucy is the most prolific chicken, with almost 300 eggs in her first year of laying. Zsa Zsa had laid 200 eggs in almost eleven months. Whoopee is the laggard, tallying a mere 112 eggs over ten months. That’s okay — what Whoopee lacks in egg production, she makes up for with her good looks and goofy personality.

How do I know how many eggs the Girls have laid? Because I keep an egg journal. It’s a fun way to keep track of the eggs I collect from my flock. You can use a calendar, a spreadsheet, or even a real journal to document your hens’ egg-laying ways. Once the Girls started gifting me with eggs, I became familiar with the color and style of egg laid by each chicken. I identified and noted each egg every day on my kitchen wall calendar. Of course, keeping track of eggs is easy with two or three chickens, but it gets more challenging with each additional hen.

Keep an egg journal to track your chickens’ egg-laying prowess.

Hens lay their eggs in “nest boxes,” private, shoebox-sized cubicles along a henhouse wall.

Hens begin laying anywhere from five to six months of age. A pullet’s first egg will be small. It may also be discolored and somewhat misshapen. That’s okay — after all, your chicken is just getting started, and it takes a couple of months for nature to calibrate this process. After that first egg, your hen may not lay for another day or two. When she does lay again, the egg will be larger and the color more firmly established.

If you pay attention to your hens, their behavior will let you know when they are getting ready to start laying eggs. The first is what I call the Egg March. Although the hens don’t know it, nature is getting them ready to lay. The Girls were about four months old when I noticed that at about the same time each day, all three hens, if loose in the yard or just hanging out in the coop, would resolutely march back into their henhouse. I peeked in on them to see what they were doing. They were standing around, taking turns digging in the nest box. Half an hour later, they’d go back into the yard, unsure why they’d left it in the first place.

The other thing a hen will do when she is about ready to lay (or when she’s just started laying) is squat down in a defensive posture, wings slightly away from her body, when you try to pet her. At first I thought my hens had developed a severe inferiority complex. Then I learned that this is the position a breeder takes when she’s getting ready to accept a mate. Mating, of course, is coincident with the production of eggs.

When a hen lays her first egg, she’s not sure what is happening to her. The urge to lay comes on suddenly. She will retreat to the nearest corner of the yard or coop. There, she will spend the next 15 minutes diligently digging a shallow hole. Once the hole is a depth acceptable to the hen, she will sit in it, tail to the wall, beak to the wind. Another 15 minutes go by, and she suddenly stands up and runs off as if nothing has happened. There sits your first egg, snuggled in a nest of fallen leaves and still hot to the touch!

If your hen starts laying in mid-summer, she will be pretty regular, with an egg every day or two. If a hen begins to lay in fall, or in winter after the fall molting, eggs won’t come so regularly — maybe two to four eggs each week. Hens lay better in warmer weather, and they slow down in the cold season. However, if the weather gets too warm and the hens can’t cool properly, their laying may be less consistent.

Chickens lay their eggs at about the same time each day. Because chickens typically lay an egg every 25 hours, you would expect them to lay their next egg later each day. My Girls don’t do this. Lucy is the early riser, and I’ll find her hot egg between 8 and 10 a.m. each day. Zsa Zsa jumps into the nest box next and starts her celebratory egg squawk about an hour after Lucy. True to her laid-back form, when Whoopee bothers to lay an egg, it’s late in the afternoon, after I’ve already gathered the early eggs. Though Lucy and Zsa Zsa always lay eggs in their nest boxes, Whoopee sometimes can’t be troubled to waddle into the henhouse, and she will drop her egg just inside the coop door, where she was pacing and waiting to be let out.

Encourage your hens to lay in the nest boxes you’ve built for them. To do this, keep your hens cooped up until late in the afternoon, until you’re sure they all had a chance to lay. This way, the hens won’t get used to laying hidden eggs in the garden. Once your hens are accustomed to their laying routine, they can be let out in the yard, and when the urge to lay hits them, they’ll run right back to the nest box.

Sometimes a hen just won’t get it. Instead of laying an egg in those lovely nest boxes you’ve built her, she will lay on the henhouse floor (not the cleanest place to lay eggs, especially after a night of roosting) or dig a hole in the run and lay there. Show your hen to the nest box by planting a fake egg there. You can buy a fake egg at the feed store, but any egglike object will do. I’ve used those hollow plastic Easter eggs and golf balls. Both work well in luring the hen to the nest box to lay. Once a hen sees an “egg” in the nest box, she seems to say to herself, “Ooh, that looks like a good place to lay an egg! Someone has already laid there . . . guess I will lay there, too!” Voilà, egg in nest box.

Chickens need between 14 and 16 hours of light each day to lay. To keep your hens laying eggs consistently through the winter months, install a hanging light fixture with a 25- to 40-watt bulb set on a timer in the henhouse. Some folks install heat lamps for this purpose, but I think that they run the risk of making the henhouse too hot. Set the timer to turn on two hours before dawn and two hours after sunset. Small-wattage bulbs in the henhouse can make a big difference in the frequency and number of eggs laid throughout the winter months.

While artificial winter lighting for chickens is generally a good thing, I have one caveat. Extending natural daylight appears to play around with chickens’ internal clocks. They wake up before the sun comes up, and they stay awake in their henhouse long after the sun has set. The net effect can be to turn mere household hens into bona fide party chicks.

I gave the Girls lots of extra light last winter. I noticed that instead of going to bed at dusk, like most chickens, the Girls began hanging out later and later in the garden. I wasn’t sure how they were doing this, as chickens are notoriously night blind. Then I saw that they were using the shaft of light that shone through the open coop doors to find their way back home. One time, the coop and henhouse doors had somehow closed, and no light spilled out into the yard. On a moonless winter night, I looked out the back window and saw them standing together, fluffed out and huddled close in a group in the middle of the lawn. They had been so busy hunting bugs they didn’t notice it had become dark. The Girls couldn’t find their way back to the henhouse and figured they’d tough the night out unsheltered in a huddle in the yard.

In an ideal world, you would collect eggs promptly after they are laid. But because most folks aren’t stay-at-home chicken lovers, it’s more realistic to say that the eggs should be brought in no later than the end of each day. Eggs left in the nest box overnight or for several days will not be fresh. Also, eggs left too long in a nest box are prone to breakage, as the hens lay more eggs on top of preexisting eggs. Leaving eggs in the nest box may encourage bored or anxious hens to begin eating the eggs. This bad chicken habit is very hard to break once it’s begun, so prevent it by collecting eggs each day. This won’t be too hard to do, especially if you have kids. Kids love to race outside and get the fresh eggs. Who can blame them? Collecting fresh eggs from your own garden is really cool!

Bits of dirt or manure may adhere to the eggshell during the egg’s brief stay in the nest box. When you bring in the eggs, wipe them clean with a dry cloth or lightly scrub them with a coarse paper towel or very fine sandpaper. If you can avoid it, do not wash the egg with water. Eggshells have a natural outer coating that keeps bacteria out. This outer coating is water soluble; in other words, if you wash the egg, you also wash away its protective coating. If the egg is so dirty that you must wash it, use it right away.

If you can’t use a dirty egg right away, use a damp sponge with no detergent to rub off the dirt. Dry the eggshell thoroughly with a soft cloth, then rub a little cooking oil over the entire egg, wiping away the excess. The oil will help replace the natural coating on the shell that keeps bacteria and other unwanted organisms out of the shell’s precious contents. Personally, I don’t fuss around much with Ma Nature, and I recommend washing the egg only as a last resort. Usually a dry rub will do the job.

A chicken can lay more than 600 eggs in her first two years.

If an egg you collect is dirty, wash and dry it, then rub it with cooking oil.

Store eggs in the refrigerator, where they’ll stay fresh for two to three weeks.

Do not hard boil eggs immediately upon collecting them. The whites and yolks of day-fresh eggs just don’t gel adequately. Also, the egg white sticks in large chunks to the eggshell when you try to peel a fresh hard-cooked egg. I recommend that, after collecting eggs, you dry them and put them in the fridge for a day or two to give their gelatinous contents a little time to settle down inside their shells.

Although I doubt you’ll have trouble giving away your fresh eggs, you just might have Super Hens that lay too many. Don’t let any precious eggs go to waste. You can always freeze eggs for later use. However, never freeze eggs in their shell unless you enjoy eggs exploding in your freezer. Crack the fresh, surplus eggs into a freezer-tolerant container, scramble them up with a little salt, and seal the container securely. This way, your extra eggs keep in the freezer up to six months.

If you and your family are eating all the eggs you want but don’t want to freeze the extras, you may want to share the surplus with those less fortunate than you and your family. Contact your nearest women’s or homeless shelter or any other charity that feeds hungry people to inquire whether it will receive your eggs.

What if you have more eggs than you can give away? Can you sell your surplus? The only thing you cannot readily do with your surplus eggs is sell them. Com-mercial egg producers are required to heed federal standards and industry guidelines for egg quality, so all eggs (presumably) are in-spected to ensure they comply. Unless you want to set yourself up as a commercial egg producer, complete with adherence to federal regulations, regular health inspections, and a lot of other red tape, you cannot sell your eggs. In fact, city law usually prohibits the unregulated sale of fresh eggs by residential chicken keepers. Exceptions to this type of law may permit you to sell the eggs privately at produce stands and community farmers’ markets. However, don’t sell a single egg until you check your city codes or town ordinances for the law.

Poultry Tribune, circa 1940.

Many people associate chickens with filthy living conditions. It’s true that a chicken coop that’s not cleaned once or twice a week will get stinky. But we human keepers have certain responsibilities to our critters. The main commitment that we have to city chickens is to keep their coop clean. If the coop is well maintained, it won’t smell, and the birds will be both happy and healthy.

Large numbers of chickens are difficult to keep super clean. That’s why chicken farms are located on acreage, not on a city lot. Fortunately, a few chickens in a city yard are nothing like dozens of chickens on a small farm or hundreds of birds in a mass-production chicken environment. The advantage to a small flock of chickens in the city is that the birds are easy to keep clean. You don’t need a lot of fancy equipment, regular inspections from the USDA, or even more than a couple of hours of work every week. Cleanliness for a small two- to five-bird coop simply means removing and properly disposing of the manure in the coop and henhouse regularly.

Moisture is the enemy of a clean coop. Excessive moisture from chicken droppings or spilled drinking water leads to molds and bacteria, which can lead to allergies or infections in the chickens. Moisture unchecked eventually ferments and stinks, which leads to unhappy neighbors and a steady convention of blowflies in and around the coop.

Your chicken coop will stay fresh and dry if you place liberal portions of chopped straw and wood shavings (especially pine) on the floor of the run and the henhouse. It’s important that the straw be chopped; unchopped straw can contribute to moisture buildup and disease. Each week, spread 8 to 12 inches (20–31 cm) of chopped straw over the chicken run. It sounds like a lot, but it gets tamped down quickly with a busy flock of bell-bottomed chickens stomping about. Spread 1 to 2 inches (3–5 cm) of wood shavings over the floor of the henhouse, and put fresh chopped straw over that, in the same thickness as in the run. Fill each nest box with 6 to 8 inches (15–20 cm) of straw, tamping it down to provide a firm fit for the hen and her bottom. Hens like to lay their eggs in tidy places that are private and quiet.

You can buy bales of straw from your local feed store. Large bales of straw cost about $5 and will last for several coop cleanings. They should be stored in a dry place. I buy two bales at a time and store them behind the chicken coop, tucked beneath the deep roof eaves and covered by a rubber tarp. Don’t store your straw where the chickens have access to it. Chickens love to play in fresh straw. If you leave a bale where they can get to it, they will have the time of their lives kicking it apart.

At least once a week, remove thickly soiled sections of straw from the run and henhouse. Scoop up the debris with a pitchfork or rake it into a pile. If you don’t have a compost bin, now is the time to get one. Put the soiled straw into your compost bin, along with the usual organic composting materials. Chicken poop is a rich source of nitrogen, an essential active agent in the composting process. After you have scooped out most of the droppings in the coop, fluff up the remaining straw with a pitchfork or rake. Then, top it off generously with a layer of fresh straw 8 to 12 inches (20–31 cm) thick.

Straw is the best kind of litter for the chicken coop; it is absorbent and sweet smelling.

Composted chicken manure becomes rich garden soil.

If you don’t have enough space for more than one or two compost bins, you need to consider how and where to dispose of soiled straw. On trash collection day, you could put the soiled straw out in addition to other yard debris for the period. A better alternative is to offer it to your friends. I have friends and neighbors lining up for my manure-laced straw. They bring by their trash cans and wheelbarrows, and I fill them up with the soiled bedding from the coop. Friends leave my house with cars full of chicken poop and smiles on their faces. I’m never at a lack for takers on coop-cleaning day. Actually, I have a waiting list for every barrel of poop straw I don’t use in my own compost bin. Who would have guessed that chicken poop would make me so popular with my friends?

A note about composting: It takes time. Warmth, combined with regular air and moisture, hastens the composting process, regardless of what is in the compost bin. Don’t expect to toss mounds of chicken droppings into the compost bin and then to mix it into your garden soil a week later. The high acidity of the chicken manure in the immature compost can be too much for your garden plants. Putting large, concentrated quantities of chicken manure directly into a garden can “burn” your plants. Manure, together with the other compost ingredients (lawn clippings, fallen leaves, coffee grounds, vegetable discards — produce too wilted or rotten to feed to the chickens — and bits of clay soil) needs to break down over three to six months.

After a few weeks, the dirt in the chicken run, if once compacted clay soil, will be dark and crumbly. The chicken drop-pings and straw, together with the nearly constant scratching by the hens in their pen, instantly improve any soil beneath their scaly chicken feet.

Some small-flock chicken keepers have another method of dealing with coop care — they do almost nothing. This is known as the “deep litter system,” and it works like this: no removal of droppings, no fluffing, just adding straw regularly to the coop and henhouse floors all summer through winter. In spring, all of that prime compost material has been mulching nonstop for three seasons. This is one way to efficiently compost chicken waste and organic matter directly onto a large area without doing much of anything. However, you have to control the odor that will surely emanate from the coop by leaving the chicken waste in and merely adding lots of straw and cedar shavings. The problem with the deep litter system, besides the inherent odor worry, is the tendency for the coop to get damp. Dampness is not a condition tolerated by chickens for long without some type of disease sprouting up in the flock (like coccidiosis, a parasitic infection transmitted through chicken droppings). Personally, I prefer the meager labor once weekly in freshening up the chicken coop. The deep litter system would work better in a small, mobile coop or in a coop on a large tract of land with not many neighbors nearby. For urban chickens, the deep litter system simply stinks too much.

Every couple of months, inspect the coop and henhouse to make sure there are no loose screws or nails, splinters, or jagged wire that could harm your flock. Chickens love to peck and pick at things with no regard for their own personal safety. They’d swallow a small screw in a jiffy if given a chance, so don’t give them the opportunity. Experience has taught me that important lesson.

I have a basement window that looks into the coop. I had noticed that the caulking was missing from the frames; panes were loose. This could be dangerous for the Girls if one of them pushed up against the glass. I put up the temporary garden fence and routed the hens out of the coop. Then I caulked the panes with generous helpings of wood putty. Hours later, the putty appeared dry and I bribed the hens back into the coop with — what else — cottage cheese. Early the next morning, I woke to a distant, rhythmic tap-tap-tapping. It sounded like it was coming from inside the house.

Thinking rats were rummaging around in the basement, I quietly went downstairs to sneak up on them. The tapping noise grew the lower I got. Tap-tap-tap. I looked around the dark basement. It took me a minute, but I realized that the hens were making the tap-tap-tap as they feasted on the window putty from inside their coop. Oh no! I ran outside to the coop and shooed the Girls away from the window putty. Fortunately, it was just one hen (Zsa Zsa) who did most of the eating — it was easy to tell because she was the only hen with a full putty “beard” outlining her beak. Fearing the worst but hoping for the best, I promptly fed her an apple, hoping to flush out the putty. I was lucky. Zsa Zsa seemed to have no ill effects from consuming several tablespoons of wood putty, and I didn’t lose a hen. I reputtied the pane, this time using a super-fast-drying brand. I also put up a wire screen around the window so the Girls couldn’t get right up next to it. No more putty for the poultry.

Every couple of months, inspect the coop to make sure it has no loose screws or nails, splinters, or jagged wire that could harm your flock.

The scoop on coop care is basic and unwavering: Keep the coop clean all the time. No matter when you do it, or how you do it, do it. Your chickens and your neighbors will appreciate the fresh straw and clean accommodations. Remember, if the coop smells, it’s not the chickens’ fault . . . it’s yours!

In summer, keep an eye on your chickens to make sure they are not too hot. Provide them with plenty of water. A heavy breed of hen can drink more than a quart of water each day during warm weather. Make ample shade available during the hottest part of the day. The henhouse can become an oven when the thermostat hits 90° F. Don’t let your chickens roast on the roost! Ensure the henhouse is adequately ventilated. Open its doors and windows to let any stray breezes drift through. If the day is hot and still, install a small portable fan in the coop by attaching it to the plug outlet used by the henhouse heating lamp in winter.

When chickens get too hot for their comfort, they pant. Their beaks part and stay open, and their little chicken tongues stick out with each labored breath. When the Girls look really pitiful, I let them out into the garden. They dig shallow holes in shaded soil and lie, breast down, wings spread open on the ground, until they cool off. If they are still hot, I fill a clean spray bottle with cool water and mist them.

Bantams aren’t as susceptible to overheating as their heavy breed cousins, but they are sensitive to freezing cold temperatures. When keeping bantams in your flock, be sure to keep them in an enclosed, draft-free, heated henhouse during any cold spells.

What’s the optimal temperature for a henhouse in winter? Depends on how cold it is and what kind of chickens you have. Heavy breeds, like the Girls, need a heat lamp when temperatures are at or below the freezing point. Bantam breeds need a heat lamp when outside temperatures dip into the 40s.

Use a 25- to 40-watt light bulb or the heat lamp from the chicks’ brooder to warm the henhouse. Affix the light or lamp away from straw and not directly over the hens’ perch. The heat from these bulbs will raise the temperature in a 3' × 5' × 5' (0.9 × 1.5 × 1.5 m) henhouse ten degrees over the course of several hours. Put the light or lamp on a timer so that it comes on around midnight and turns off when the sun comes up.

Do not use an oil or electric heater to warm the henhouse. Such devices provide too much heat for the compact space of a henhouse. The last thing you want is to dehydrate your poor chickens!

Four key elements make up a chicken health care program: a clean environment, plenty of fresh food and water, protection from the elements, and exercise.

Careful attention to coop care will ensure that your chickens have a clean environment. Nothing makes chickens (or any other pet, for that matter) sick quicker than filth.

Healthy hens are hungry hens. Eating is one of a chicken’s main hobbies and reasons for living, so don’t deprive your hens of munchies. Make sure the hens’ feed is fresh and plentiful.

Healthy chickens are dry and warm chickens. Make certain the henhouse is watertight. It’s difficult to make the coop completely water-free, so give the chickens one dry place to go in their quarters. A damp chicken is prone to catching colds (yes, chickens can catch colds!) or developing infections.

If you notice that your chicken has a cold (she will be sneezing and sniffling, same as you), crush some fresh garlic and mix it into her scratch, or put about a teaspoon of fine garlic powder into a gallon of the hens’ drinking water. The curative marvels of garlic do not discriminate between people and chickens, and soon your flock will feel better.

Healthy chickens need their exercise. They love to walk and scamper around the garden, scratch up dirt for bugs and worms, and run and flap their wings a bit (this latter activity may look like your chicken is trying to fly, but she won’t make any progress, especially if your chicken is a plump, heavy breed). This outdoor time breaks up the boredom of staying in the coop all the time. If your hens don’t get enough leg time in your garden, it can cause them to become anxious and fidgety, and they may start picking on each other. Regular free-range grubbing and running in the yard make for happy, well-adjusted chickens.

If I don’t let my hens out for a couple days because of bad weather, they’ll get cranky and stop laying for a few days (okay, Girls, I get the message). But as soon as they get some yard time, even half an hour between rainstorms, they start laying eggs again. It just goes to show that regular exercise is as important to a chicken’s health as it is to ours.

Chickens that don’t get enough activity get fat. Obesity in chickens contributes to the health problem known as egg binding, which occurs when an egg has become lodged up inside the hen, and she cannot expel it during laying. A fatty layer has built up around the hen’s reproductive organs, inhibiting the oviduct from moving the egg down toward the vent. Sometimes chickens bind up simply because an egg they are trying to lay is too large.

If you notice that your hen is looking uncomfortable, standing or moving in a strange way with her head or tail down, she might be binding up. Help her immediately! Place her in a warm area (under a heat lamp) to relax her. Sometimes warmth alone will help her pass the egg. If heat doesn’t work, massage some vegetable oil very carefully around her vent while gently massaging the hen’s stomach in the direction the egg should be traveling. If no egg emerges, hold the hen over steaming water, being careful not to burn her. I’ve read that some folks, as a last resort, will gently break the egg while it is in the hen, and bit by bit empty its contents, with the hen’s contractions pushing out the rest. However, the hen may die from shock or a heart attack if the egg remains stuck in or while the egg is being broken inside her. Exercise your hens consistently to avoid this and most other health problems.

Another health problem for chickens is feather picking, which occurs when your chicken, usually prompted by some type of physical or emotional discomfort, pulls off large quantities of its own feathers or the feathers of fellow hens. If you catch your chicken at feather picking, you can discourage this behavior by applying a mix of one part vinegar to five parts water with a washcloth to the bird’s bare areas. This cleanses the area, and the stink and taste of the vinegar discourage the chickens from further picking.

Chickens take dust baths to cleanse off any mites they pick up. However, if the mites are visible to your naked eye, the problem is too far gone for the hen to take care of with a dirt bath alone. Be on the lookout for a mite infestation: If one chicken has mites, chances are the others in the flock also do. Mites sometimes appear as tiny, almost invisible brown pinheads crawling on a chicken’s skin, beneath the feathers. The mites may also be visible crawling on the roost where the chickens sleep. Another type of mite demonstrates itself as patchy, crusty, whitish scales on a chicken’s legs.

You can eliminate mites with either a powder or a spray treatment available at the feed store or on-line hatchery and supply stores. These powders and sprays aren’t toxic and are usually effective with repeated applications. To apply the powder, place the recommended dosage in an area in the coop where the chickens take their dust baths. This way, they can apply the dust themselves without being handled. If you apply the powder or spray directly on the chickens, I recommend doing this at night after they have gone to roost. Chickens don’t see well in the dark and are quiet and passive after sundown. You can control exactly where you apply the medication, and the chicken won’t stress out and protest the application as they would during daylight hours.

A home remedy for leg mites is to soak the chicken’s legs in warm, soapy water twice daily until effective. However, holding a chicken still long enough to really soak those legs is more of a challenge than some could handle. Instead, use a damp, soapy sponge or washcloth to wipe the chicken’s legs with one hand while holding her under your other arm. Again, to make this treatment easier for you and the chicken, do it after sundown.

Like any other bird, your chickens will molt each year. Chickens start molting as early as midsummer, and the molt may continue until late fall. During their molt, chickens lose old feathers and new feathers, called pinfeathers, sprout out like porcupine spines. Some chickens molt so slowly and gradually that you barely notice they’re molting. Others throw off all their feathers at once and are half-naked for a couple of months.

Molting is stressful for a chicken. Just imagine if you spent your entire life covered in soft feathers, then suddenly lost them all and became covered in hard-shelled spikes instead. You’d probably be uncomfortable, too! Chickens aren’t real happy when they molt. In fact, they get downright crabby. Sometimes they become skittish, moody, and aggressive. And they lay considerably fewer eggs.

Make sure your chickens get plenty of good, nutritious feed during the molt. This will help them maintain their strength and vigor. A vigorless hen is a sorrowful sight.

For more information on chicken health and home care for certain ailments and conditions, check out The Chicken Health Handbook by Gail Damerow. It has everything you’ll ever need to know about chicken health through the years of keeping your pet flock. If you are not comfortable administering health care other than the basics, or if your chickens are too sick for home remedies, contact your local avian medical center or veterinarian specializing in bird medicine and surgery.