With your coop planned and construction under way, it’s time to start thinking about your future pen of hens. Before you buy any chicks or chickens, it’s important to educate yourself about all of the different breeds. By familiarizing yourself with the specific characteristics of the many chickens available, you will be more likely to pick chickens that will do well in your region and meet your needs for eggs and entertainment.

If you have access to a computer, start your research with the Internet. The World Wide Web hosts dozens of sites devoted to chickens, where people from all over the world share their chicken stories, tips, and pictures. A few of my favorite web sites are listed in the appendix, and hundreds of others I haven’t listed are waiting for you to find them.

Many on-line hatcheries have chicken facts and links to yet more chicken sites. Some general information chicken web sites will lead you to great books covering every facet of chicken ownership, from urban chicken keeping to small farm chicken breeding. Before you know it, several hours will have passed on the Internet while you’ve been reading and thinking chicken.

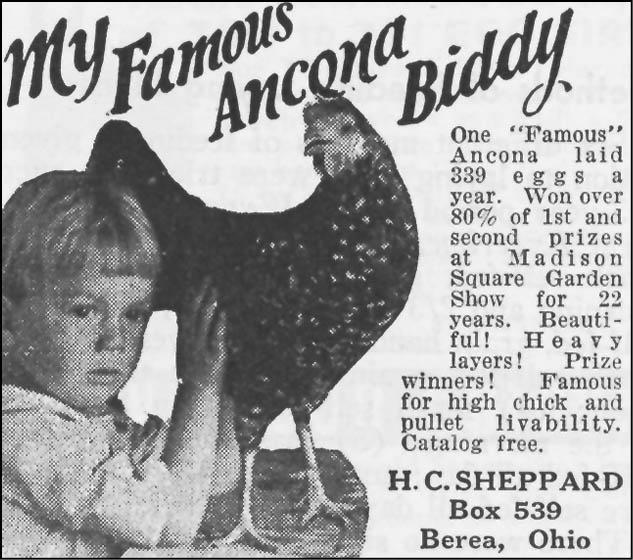

Poultry Tribune, circa 1940.

If you don’t have a computer in your home, go to your local library. Most libraries have computers with Internet access that you can use for free. If you are computer shy, read the books at the library to get you started. Great books about keeping chickens are available at all good bookstores, feed and supply stores, and yard and garden shops.

Picking chickens is as much as, if not more fun than, designing the coop. After reading about breeds, you can make informed decisions on which chickens you want to keep in your urban flock. Perhaps the color or pattern is the primary criterion for picking your chicken. Should you get big chickens or small ones? Maybe you want a mellow friendly bird, or one more inquisitive? Have several breeds (and styles) in mind when shopping for chicks. When you visit your local feed store in spring, it may not have all your first picks. The eclectic or rare breeds are almost always available from reputable Internet poultry hatcheries and poultry supply stores.

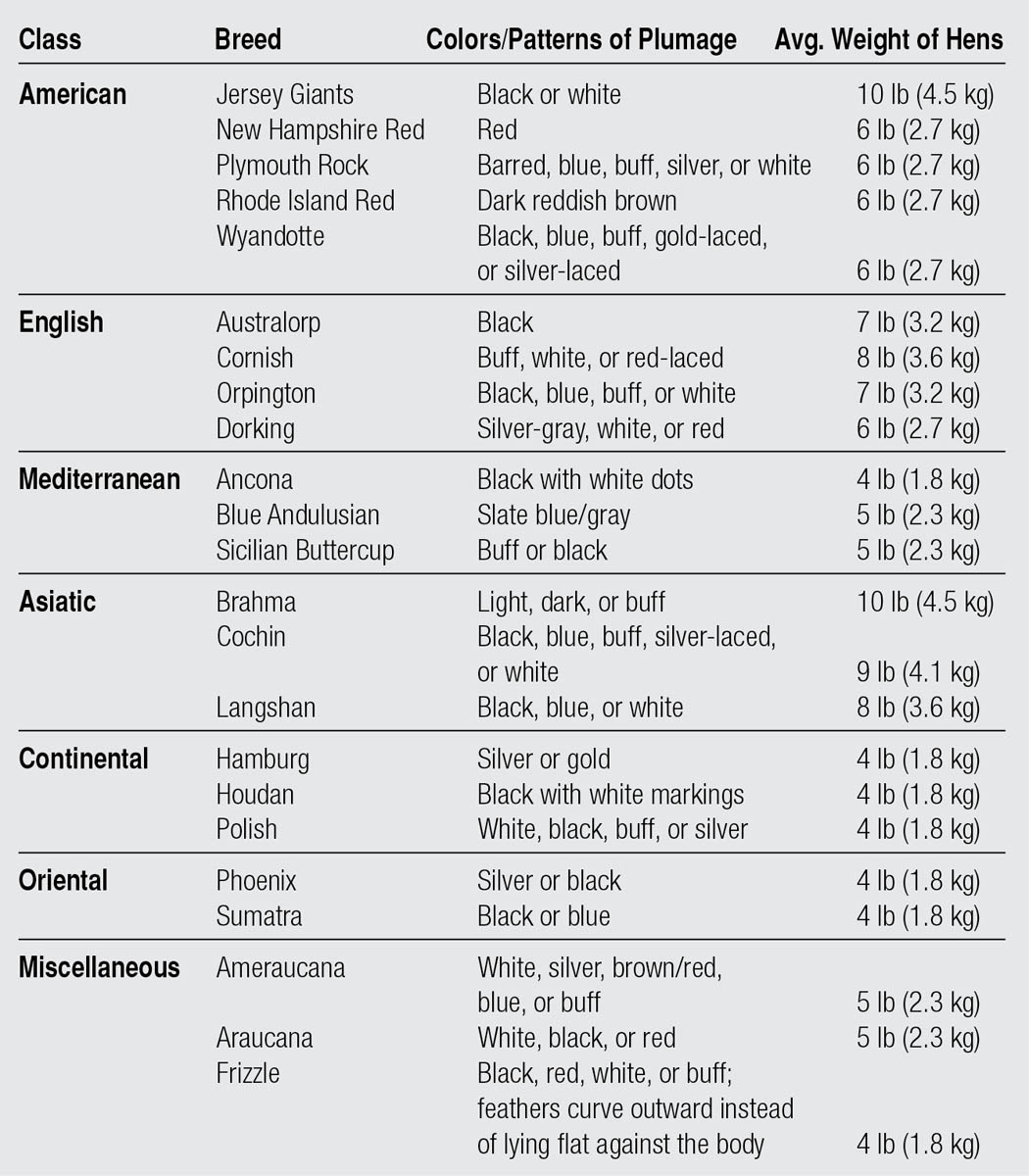

Purebred chickens are organized according to class, breed, and variety. Class is the broadest category of chickens, and it generally refers to the regions where the chickens were originally bred or with which they are traditionally associated. Chicken classes include Asiatic, American, Continental, Mediterranean, English, Oriental, and Miscellaneous.

Within each class of chickens are particular breeds. Chickens of the same breed have a similar body type, features, and markings. The breeds are basically divided into two categories. Standard breeds are medium to heavyweight chickens. Bantam breeds are smaller, lightweight chickens. The standard breeds tend to be mellower, while the bantams are known as “flighty” for two reasons: They are somewhat nervous all the time, and they can fly up to 6 feet (1.8 m) into the air, giving them plenty of clearance over most fences. Some breeds are excellent egg layers; others are well regarded for their meat. Dual-purpose breeds are known for both their meat and their eggs. Breeds with striking features or feather arrangements are sometimes known as ornamental breeds.

A breed can contain several varieties. A variety generally has a specific pattern or color of plumage. For example, Plymouth Rock is a breed in the American class that comes in several varieties, including a pattern known as barred (black and white herringbone) and colors like white, buff, blue, or silver. Wyandottes, one of the prettiest dual-purpose breeds, come in several varieties of solid colors as well as a vibrant silver-black or gold-black fish-scale pattern.

The American Standard of Perfection, published by the American Poultry Association, describes the ideal conformation and standards for each breed. Show strains are chickens whose physical type and traits conform to the breed standard. These supermodels of chic chickens travel nationwide to compete in poultry shows.

Each class of chickens contains several breeds, which themselves may contain several varieties with specific patterns or colors of plumage.

While the show strains in a breed are the upper-crust birds of chicken fancier society, utility strains are the blue-collar, working-class chickens within their breed. These chickens are purebred, but they possess certain imperfections that render them incapable of conforming to the breed standard required in poultry showing. These imperfections might be something as sinful as a narrow breast in a breed whose standard is a wide breast, muted or runny colors in a breed with a patterned plumage standard, or misshapen beaks or feet. There’s nothing really wrong with these birds — they’re just not perfect supermodels! They are the “regular folks” of the chicken world. The birds you find for sale in local feed stores are usually utility strains of certain breeds. Though not up to show standards, these chickens have no problem laying eggs, digging compost into your garden, and making you laugh.

The hens of dual-purpose breeds tend to be tamer and less broody than hens of other breeds.

In addition to purebred chickens, you may also come across chicken hybrids. Most hybrids, also known as crossbreds, were developed by commercial poultry growers so that they could obtain the maximum amount of eggs and/or meat from a chicken. Hybrids tend to be plainer-looking than purebreds, and they can be quite nervous, a trait you may not want in your urban flock. An example of a popular commercial hybrid meat production chicken is the Cornish-Rock. This meaty bird was the result of an English Cornish being crossed with an American White Rock. Good egg-producing hybrids include Black Sex Link and Red Sex Link hens.

Below is a partial listing of chicken classes, breeds, and varieties to get you familiar with the wonderful world of chickens.

While many standard breed chickens have a bantam equivalent, there are few true bantam breeds. The most popular of these are the Silkie, with its fine, white flowing plumage, and the Japanese, with its long, elegant tail feathers. Ah, so many chickens, so little time!

Chickens are social creatures. They like company: their own company and yours. My chickens like it when I talk to them out the window, or when I sit and read with them in the yard. However, I can’t always be with my chickens. That’s why I have several — they keep each other company. No matter what breed or variety you decide on for your pet urban flock, don’t get just one hen, because she will get lonely when you are not around to talk to her. Nothing is sadder than the mournful moaning of a bored, lonely chicken. Chickens can be quite vocal about their emotions.

When thinking about what chicken to get for your flock, keep in mind the climate where you live. Standard breeds don’t tolerate extreme heat or humidity very well. Bantam chickens, by contrast, which weigh just 2 to 4 pounds (1–2 kg), have less body mass to cool off and can take the heat. On the flip side of the coin, standard breeds have ample insulation against the cold, while bantams in a cold coop will shiver themselves down to nothing.

If you live in a region with freezing cold winters (Northwest, Northeast, Midwest), pick chickens of the heavier standard breeds. In the Southwest, Southeast, and Deep South, where winters are milder and most summers are consistently hot and humid, heavy hens would do as well as a polar bear in a hot tub. Bantams or lighter medium-weight standard breeds are best for such temperate or subtropical climates.

Having learned a little bit about breeds, you now have a better idea of what kind of chickens you may want. You already know that chickens come in two different sizes: bantam (small) and standard (large). Of course, besides the size differential, not all the chicken breeds are created equal. Some hens, like Plymouth Rocks and Rhode Island Reds, can weigh in at 6 to 7 pounds (3–4 kg), while others, like the Jersey Giant and the Brahma, tip the scales at a hefty 10 pounds (4.5 kg). A 10-pound chicken? That’s the size of a small turkey! While such hefty chickens are the exception rather than the norm, they do exist. But before investing in one of these “big-boned” breeds, remember: The bigger the chicken, the more it eats. And chickens love to eat. If a low feed bill is important to you, pass on the big Brahma and Jersey Giant and consider a svelter breed, like a Rhode Island Red or Partridge Rock.

The Sebright (left) is a good example of the size of a bantam breed, and the Leghorn (right) of a standard breed.

Chickens come in a vast array of colors and feather patterns. They can be plain or fancy. They can have fluffy tufts on top of their heads, or have bare naked necks. They can have long slender legs, or legs so thick with feathers they look like waddling, fluffy pears. Some chickens have big, showy combs atop their heads, while others have just a short, blunt mohawk for a comb. Chickens are black, white, buff, brown, red, orange, gray. Chickens come with spots, checks, barring, or solid patterns. As with any species, it takes all kinds.

As I’ve mentioned several times, my Girls include a Barred Plymouth Rock (Zsa Zsa), a Rhode Island Red (Lucy), and an Australorp (Whoopee). Out of the three, Lucy is the best layer, despite her breed reputation as a moderate laying dual-purpose breed. Lucy gives me a medium-sized, speckled brown egg nearly every day.

The next best layer in my flock is the Barred Plymouth Rock. Zsa Zsa lays four to five large or extra-large eggs on me a week. If Zsa Zsa misses a day or two of consecutive laying, she will leave a huge egg the next session to make up for it — and not infrequently it’s a double yolker!

The Australorp (Whoopee), the biggest hen in the flock, lays eggs the most sporadically. Australorps are reputed to be prolific layers, but my Whoopee is not one of those. Thank goodness Whoopee is fun and good looking, because she sure is lacking in the egg-laying department!

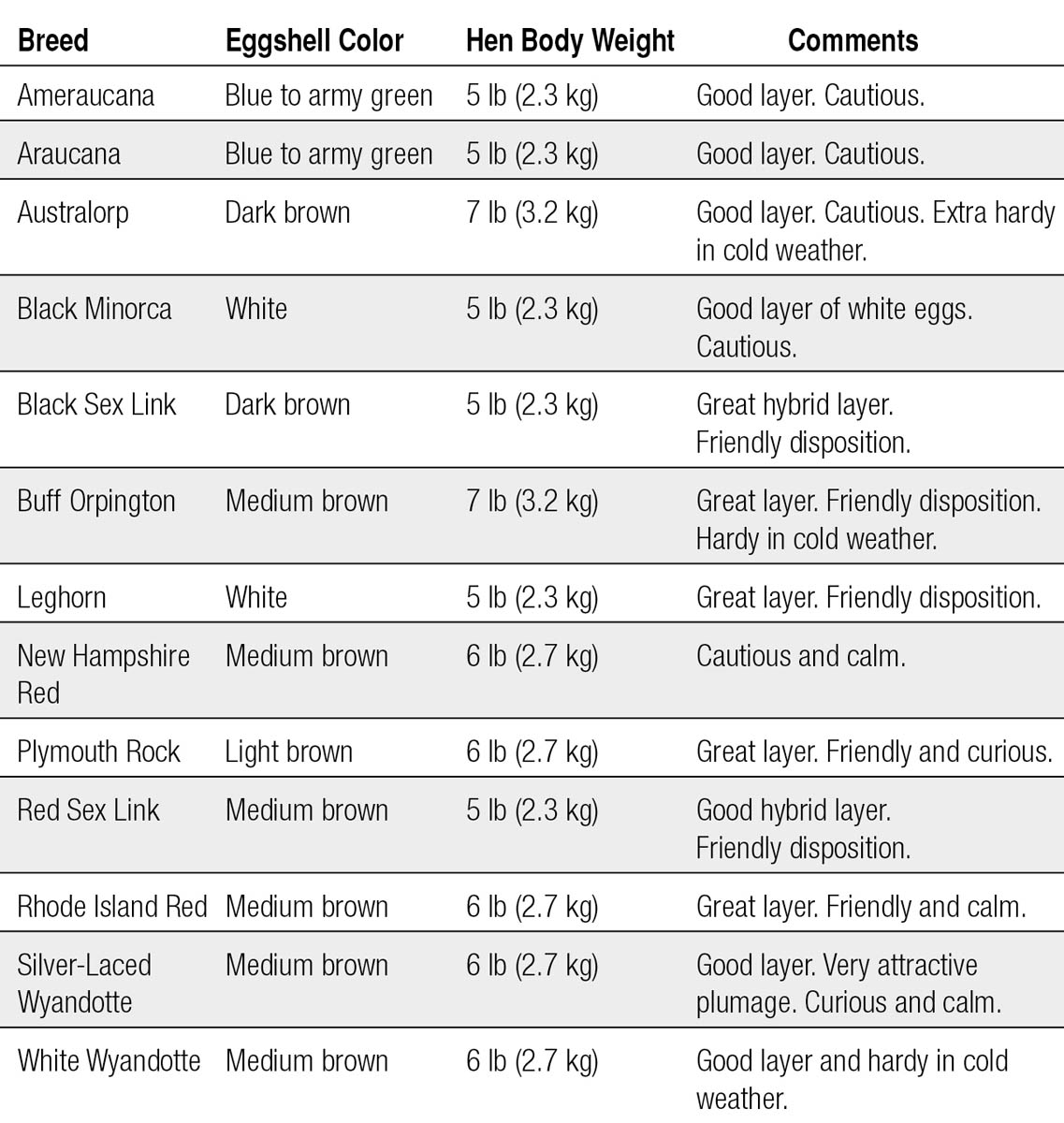

Good chicken breeds and varieties for urban flocks include chickens that are tame, quiet, hardy, and not broody.

I mentioned the Girls’ laying habits for a reason. Individuality counts. You may pick one breed because it’s reputed to be an Olympic-quality layer and another breed for its good looks, but chickens, like people, are not all created equal. A chicken you choose for plumage may end up being a veritable egg machine, while the reputed layer drops an occasional egg as little more than an afterthought to a day of grubbing and clucking. Since garden flocks are usually kept as much for fresh backyard eggs as their fowl company, I’ve listed what are considered the most dependable egg-laying hens in the table below. These are all light- to medium-weight hens that would do well in most any climate (or what I otherwise refer to as the All-Season Hen Collection). Most of these hens are friendly, quiet, and not overly active. All are dependable egg layers, but none is reputed to be broody (that is, to have a tendency to sit on a clutch of eggs to try to hatch them). Brooding is a rather moot endeavor for the urban hen, as she has no rooster to fertilize the eggs. Brooding is also an eggless time for you, as the hen will not lay new eggs while being broody.

Why get chicks instead of chickens? To begin, mature chickens aren’t usually available for sale in the local feed stores or from on-line hatcheries. If you can find one for sale, a full-grown hen will cost you about $20 (compared to a baby chick that costs about a buck). After folks have spent several months of time and chicken feed plumping up their hens into maturity, they are not very likely to let them go (would you?).

However, if you really want a head start on hens, pullets that are three to five months old are sometimes sold at feed stores for around $10 each. For my money, I prefer getting a baby chick to raise myself. This way, you get the enjoyment of watching a chick grow up, and the chick knows you all its life. A hen you’ve raised from a chick is apt to be much tamer than an older pullet or young hen you would purchase. Plus, you have no idea how a mature chicken was handled before you brought it home. If you want the bird to be friendly, accustomed to being handled, and as well-mannered as nature will allow it to be, you’d do best to raise it yourself from chickdom.

If you want chicks, get chicks that are already born. Don’t get eggs and try to hatch your own chicks. It’s too involved a venture and requires more time and attention than you probably have to give. Hatching chicks is more appropriate as a science project for kids — after all, they have lots of free time on their little hands. Plus, if you incubate and hatch your own chicks, you’ll have the problem of sexing them.

Sexing is the professional poultry grower’s term for the process of identifying chick gender. Chicks at the feed store are divided by breed, then subdivided into “sexed” categories, while a batch of unsexed chicks is identified as a “straight run” (includes both female and male chicks, as gender has not been differentiated). If you hatch your own chicks, you’ll get both male and female chicks, but you won’t know which is which until the roosters start crowing. Get girl (a.k.a. sexed) chicks that are a day or two old. By getting them so young, you will bond with them just as well as if you’d hatched them yourself.

“Sexing” a chick is the process of identifying a newborn chick’s gender; even sexing experts are accurate only about 95 percent of the time.

Pick a sexed female chick and avoid “straight-run” chicks (which have not been sexed and include both female and male chicks).

Call around several feed stores in your area to see what breeds they have on hand. If you can stand the suspense, visit a couple of the stores prior to purchasing a chick to see who has the best selection and cleanest habitats. Ask your feed store if the chicken breeder who supplies them with chicks is a member of the National Poultry Improvement Plant (NPIP). This organization promotes the responsible breeding of healthy poultry. Picking a chick out of a full brooder is like trying to pick one fish out of an aquarium tank containing four dozen. Yet if you derive pleasure from choosing your own chick, even though she looks exactly like all the others, then the feed store is your place for future chicks.

The downside of buying your chicks at the local feed store is that it may not have eclectic or rare breeds. For this reason, more often than not, be prepared to leave with a healthy, perky baby chick, no matter what the breed.

If you are unwilling to settle for a backup and absolutely have to have that Gold-Laced Wyandotte you’ve read so much about, then turn on your computer and shop at some of the reputable, regional hatcheries. These professional breeders raise lots of chickens, and they raise chicks all year long. If you can’t wait to get started, you can order chicks immediately over the Internet when you start designing and building your coop. While the benefit of shopping at year-round on-line chick hatcheries is having more breed choices, the downside is that many such hatcheries require minimum orders of 25 to 50 chicks (though this trend is changing as more pet chickens hatch in yards across America each day). No matter how well you plead your case to your neighbors or city representative, they are not likely to concede to a pet flock numbering in the dozens. Also, with on-line mail order chicks, there is always the unlikely though distressing possibility of finding a couple of dead chicks in the delivery box. Reputable on-line hatcheries guarantee a live chick to your doorstep. However, be prepared for the possibility of a fatality, and be extra happy when all the chicks you’ve ordered arrive live and peeping.

Poultry Tribune, circa 1940.

First rule with picking your chicks: no boys — they become roosters, which you can’t keep in a neighborhood yard. Pick chicks whose sex has been determined (known as sexed chicks) rather than chicks whose gender will be a surprise (straight run). If you were raising chickens for meat, you would get straight-run chicks, as you would not care whether you got roosters or hens since you plan to eat them anyway. However, if you want eggs, you need hens, so get female chicks only. A sexed chick costs about 30¢ more than a straight-run chick, but it’s worth it. For a little over a quarter, there is a 90 to 95 percent breeder guarantee that the chicken will be a female.

When picking baby chicks, avoid chicks that look unquestionably sick, have visible deformities (bent beaks, twisted legs, watery eyes), or are listless, weak, and unresponsive. When you get to the feed store, you may be staring into a large box containing one hundred baby chicks. Spend some time trying to focus on a few chicks so you can visually inspect them. Ask the store employees if you can pick up a couple chicks to take a closer look at them. I’ve always spent an hour or more staring at baby chicks to pick and bring home. By carefully examining my chicks and selecting only the healthiest looking birds, I have never had a single chick mortality.

Be warned: Baby chicks are very cute. Resist the temptation to get more chicks than you need. Chicken farmers sometimes recommend getting 25 percent more chicks than planned because chick mortality is not uncommon when acquiring large numbers. This formula is unnecessary to the keeper of small flocks. If you pick healthy chicks to start with and take care of them — keep them warm, provide plenty of fresh water and food, and change bedding frequently — you shouldn’t have any fatalities in your fledgling flock. Pick only the number of chicks you ultimately want in your flock, and take great care of them!

Poultry Tribune, circa 1940.