2

Ole the Engineer

When the summer he was 15 came to an end, Ole became restless. With his parents’ permission, he moved to Madison, the capital of Wisconsin. Madison is about 20 miles from Cambridge. In Madison, Ole was an apprentice at the Fuller and Johnson farm machinery shop. It was a good thing that Ole had made so much money giving boat rides over the summer. His room and board in Madison cost $3.50 per week, but he was paid only $2.50 per week at his apprentice job. He also had enough money left over to continue his science magazine subscription. The magazine sparked his imagination with its articles about new engines that ran on a new kind of fuel called “gasoline” rather than on steam. Ole worked about 10 hours a day at the shop. After he returned to his boarding house, he spent hours more reading everything he could get his hands on about engineering, math, and mechanics.

As an apprentice, Ole learned his craft well, and he was soon ready to launch a career as a machinist. He worked in several other machine shops in Madison, including one that made electric motors. For the next 5 years, Ole bounced from one job to another, learning everything he needed to know in order to become a mechanical engineer. From Madison, Ole moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the heart of America’s steel industry. In Pittsburgh, Ole found work in the steel-rolling mills. These mills turn plain slabs of steel into steel sheets or coils that can be used in manufacturing. At the mill, he learned the finer points of metallurgy. When he decided that he had learned enough about rolling steel, Ole moved back to the Midwest and settled in Chicago. There he landed a series of jobs that helped him to master the art of machine tool making. Machine tools are power-driven tools, such as a lathe or drill, used to cut or shape raw material into a usable form. Along the way, he also learned how to draw detailed machine plans and how to make models from the drawings. This skill is known as pattern making.

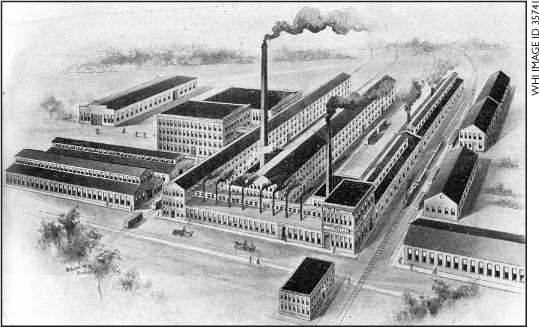

Ole was an apprentice at the Fuller and Johnson Company in Madison.

This machine shop has lathes and other power-driven tools.

In 1900, when Ole was 23 years old, he returned to Wisconsin. He lived in Milwaukee, where he got a job running the pattern-making shop of the E. P. Allis Company. The E. P. Allis Company was a major manufacturing company that made, among other things, steam engines. But Ole had a new interest that took up most of his spare time. He had read about a new type of engine called the internal combustion engine—the kind of engine that powers automobiles. Ole began spending every free moment he had working on his own internal combustion engine. He was sure that he could use all the engineering knowledge he had gained to make his own automobile.

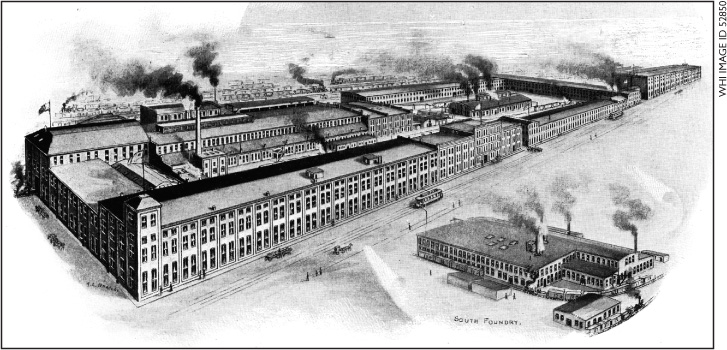

The E. P. Allis Company was known around the world for its large machinery.

In Milwaukee, Ole lived in a boarding house owned by a woman named Mrs. Doyle. It was in the basement of Mrs. Doyle’s house that Ole built his first engine. The day his engine was ready to try out, Ole forgot to buy gasoline. So that night he hooked the engine up to the pipe in the basement that supplied gas to all of the lights in Mrs. Doyle’s house. Ole cranked the engine. It worked perfectly! The engine sprang to life with an earsplitting roar. It also used all of the gas coming from the pipe. The entire house plunged briefly into darkness. Not surprisingly, the guests at Mrs. Doyle’s dinner party that evening were somewhat startled. After that, Mrs. Doyle kindly asked Ole not to cause any more explosions in her basement.

Ole at his drawing table, where he could almost always be found.

Ole set out in search of a new place to tinker with his engine. He soon found a shed for rent next to the property of a young woman named Bess Cary. Her father had died the year before. Now she was taking classes at the local business college so that she would be able to help support the family. Bess was only 16 years old.

Ole continued to improve his engine designs over the next few years. He eventually did manage to build his own automobile. He attached a small engine to a carriage. It was loud and put out enough smoke to fill the entire street. But it was also strange and exciting enough to draw crowds of people whenever Ole took it out for a spin. It was a good thing that it drew crowds, since it broke down quite often. Ole often needed help pushing it back to the shop.

Ole hoped to start a company to make and sell his automobile. He realized, however, that he would need a partner in order to make it happen. He formed a company with a fellow machinist named Clark. But neither Ole nor Clark had marketing skills, so they quickly went their separate ways. A few months later, Ole found a new partner. They formed a company called Clemick and Evinrude. This new company designed and built custom engines and parts for other companies to use in their manufacturing. This company was quite successful at first. The partners received an order from the United States government for 50 portable engines. Several car makers—which seemed to be springing up everywhere—also bought engines from Clemick and Evinrude. After only a few months in business, the company was making its products in 6 different machine shops in Milwaukee. They hired Ole’s neighbor Bess to take care of the company’s bookkeeping and marketing. Ole enjoyed spending time with Bess very much.

Unfortunately, after such a great start, things started to sour for Clemick and Evinrude. The 2 partners could not agree on how to run the company. The company fell apart after only 6 months. Next, Ole formed a new company called the Motor Car Power Equipment Company, in partnership with a retired furniture dealer. Again, the company quickly collapsed, because the partner foolishly refused to spend any money on advertising.

All of these failed partnerships may make it seem as though Ole was just a bad businessman. But it was more complicated than that. The end of the 1800s and beginning of the 1900s was an amazing period of change in the history of inventions and manufacturing. Exciting new machines were showing up every year. Inventors and entrepreneurs fiercely competed for the public’s attention.

Throughout this period of failed partnerships, Ole continued to work hard trying to make an automobile that was good enough to put on the market. He eventually developed a car he called the Eclipse. Once again he found partners to start manufacturing and selling the Eclipse. Once again he didn’t get along with them, and the venture crumbled. That was really unfortunate, because there was nothing wrong with the car that Ole had designed. If he had had better luck (or better skill) at choosing business partners, it’s quite possible that Ole Evinrude could have become a pioneer in the automobile industry, like Henry Ford! Instead, after 4 disappointing business failures, Ole gave up on his dream of making and selling automobiles.

Key Inventions Around the

Turn of the Century

An incredible number of important new inventions were created around the turn of the twentieth century. Here are just a few of them:

| Year | Invention | Inventor |

| 1891 | Modern escalator | Jesse W. Reno |

| 1893 | Zipper | Whitcomb L. Judson |

| 1895 | Diesel engine | Rudolf diesel |

| 1895 | Radio signals | Guglielmo Marconi |

| 1898 | Remote control | Nikola Tesla |

| 1899 | Magnetic tape recorder | Valdemar Poulsen |

| 1901 | Vacuum cleaner | Hubert Booth |

| 1902 | Air conditioner | Willis Carrier |

| 1903 | Powered airplane | Wilbur and Orville Wright |

| 1907 | Helicopter | Paul Cornu |

Ole designed an automobile called the Eclipse in the early 1900s, but history pretty much forgot about his car. Here are some key events and dates in the early development of the automobile that history has not forgotten:

Model T

| 1876 | — | Nikolaus Otto builds the first 4-cycle internal combustion engine. |

| 1885 | — | Karl Benz builds the first successful motor vehicle, a 3-wheeled cycle powered by a gasoline engine. |

| 1886 | — | Gottfried Daimler builds the first modern automobile. |

| 1901 | — | The Olds automobile factory opens in Detroit. |

| 1908 | — | William Durant founds General Motors. |

| 1908 | — | Henry Ford introduces the Model T. |

| 1913 | — | Ford Motor Company introduces the first moving assembly line for manufacturing automobiles. |