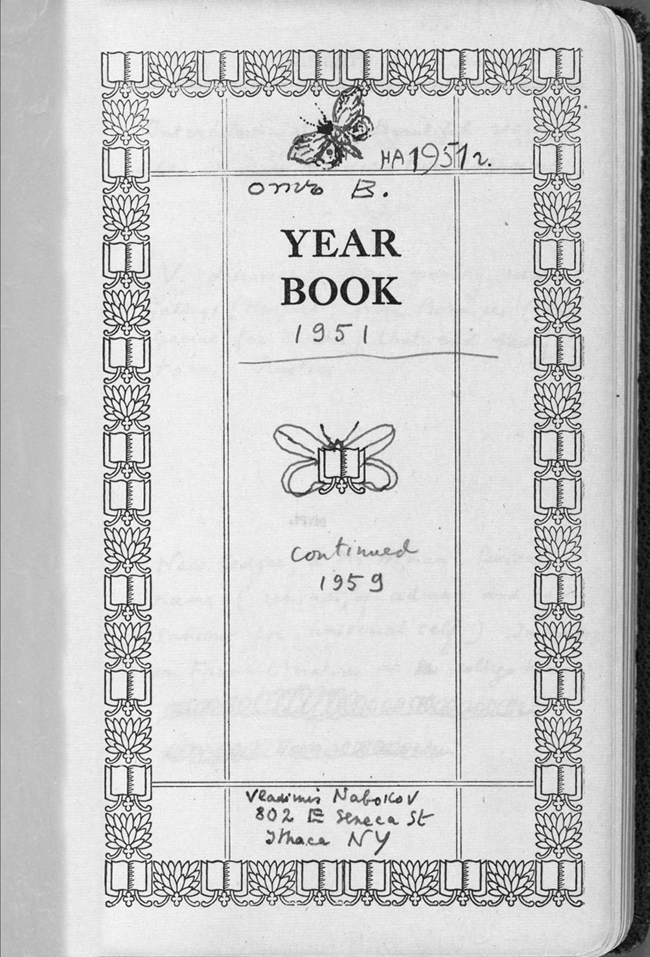

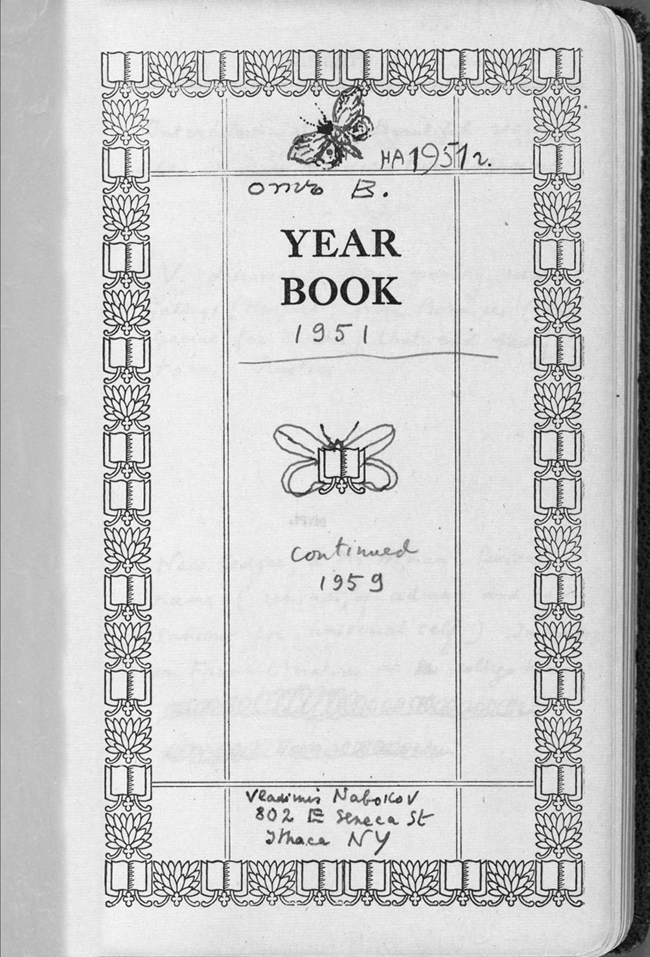

FIGURE 14. From Nabokov’s 1951 diary, Ithaca, New York.

FIGURE 14. From Nabokov’s 1951 diary, Ithaca, New York.

WHAT FOLLOWS IS a selection of Nabokov’s dream records before and after the 1964 experiment, culled, with one exception, from his 1951–59 notebook and from his pocket diaries. Even before he read Dunne’s book, Nabokov followed the basic parameters and conditions of An Experiment with Tıme, writing down a dream soon upon awakening, in great detail, without an attempt to interpret it in wake-life terms.

As mentioned in part 1, the manuscripts in his letters and diaries almost always bear signs of Nabokov’s intention to prepare some of the dreams for publication: edited words, later insertions, corrected brackets within parentheses, spelled-out numbers, facts known to him but not to an outsider, and so on.

The tiny pages of his yearly leather-bound agenda books are covered with Nabokov’s clear, rounded writing in both English and Russian, although his hand becomes very shaky toward the end. The pocket inside the cover kept a standard set of reminder strips to be pasted under the respective date (“aujourd’hui, c’est l’anniversaire de ma femme,” etc.). The last such book, the second half of its pages blank, has two more items in that pocket: a browned ginkgo leaf, now torn, and a folded clipping from the Observer for Sunday, April 10 (Nabokov’s birthday by the old style), 1977, with Anthony Burgess’s article “Christ the Man.”

The next to last entry, on May 19, records a mildly delirious dream. In the afternoon he takes his temperature and finds that he is running a slight fever (37.5°C); disheartened, he exclaims in Russian, “neuzheli vsio snachala?” [oh no, not all over again!], meaning the prospect of yet another hospitalization. This came a few weeks later, and the very last entry, of June 16, is a list of toiletries he packs to take along, and also a supply of Rohypnol, a strong oneiric sedative, still illegal in the U.S., one of whose street names is “forget-me drug.”

These diary records did not presume a reader, at least not in this unedited and unpolished state. The dream excerpts from Nabokov’s letters to his wife, given below, obviously presupposed one (and only one, I think) reader and thus were better shaped. And the few dreams he inserted in his memoirs, placed at the end of this chapter, are composed with the same care as anything in his fiction, only they are his real dreams as far as he could recall them.

[1951]

I. January 11

Dream around 7 A.M.: with V., A.,1 other people looking from window of Rumanian queen’s palace where we live, at troops (field-grey, rather old-fashioned guns, old shaggy or horribly ribby horses) passing along street, first morning of revolution, sort of parade. V. contemptuous of their appearance, A. says in awe “but they are the former Royal guards.” V. says she doesn’t care, sweeps portrait of king off console, smashing portrait, I wander out onto balcony, drizzle, railing wet and shiny,2 oldish queen sits there quietly looking at passing army wet canons, wet-dark jades. Can she really feel no sentimental thrill, no emotion whatsoever (yesterday’s glory, her [dead?] husband’s guardsmen)? Woke up on question mark.

There is not a single phrase or detail in what I remember of the dream (it was much longer anteriorly)3 that I cannot explain by chance impressions and thoughts I had recently; but over it or under it there is a kind of murmur of mystery that I cannot explain. Street was rather like street in Prague—viewed from my mother’s apartment in the early twenties. This morning Solntzev sent me some of her letters he had salvaged in Paris.4

The plot and setting recur in a number of Nabokov fictions, especially in Pnin’s chapter 4 (it also rains there at the beginning during the revolution and at the end, within and without Victor’s and Pnin’s interfused dreams) and in Pale Fire.

The plot and setting recur in a number of Nabokov fictions, especially in Pnin’s chapter 4 (it also rains there at the beginning during the revolution and at the end, within and without Victor’s and Pnin’s interfused dreams) and in Pale Fire.

It is strange, but agreeable with what can be often observed in his later experiment, that Nabokov fails to mention here—possibly fails to recall—that his grandmother, Baroness Maria von Korff, was invited, after her son, Nabokov’s father, was killed in Berlin, to Rumania by the Queen and died in Bucharest in 1925.

II. January 16

Somewhere in the W. States, burnt-leopard type of Artemisian zone (dark pattern of sage on redsoil)5 but simultaneously in the environ of Prague Czechoslovia [sic], was collecting butterflies in a vividly colored dream. Family (dead and live people) vaguely somewhere around. No butterflies flying (as almost always in my collecting dreams, though I do catch somehow some—settled on flowers etc.—probably easier to stage on the part of the dream producer).6 Then we return home (in the Petersburg sense) and I notice (with my Ithaca eyes) that E. K.7 looks as she looked thirty-five years ago and wears a pretty black dress. I mention the matter to her, with difficulty, tongue turning thickly in mouth (perhaps because I always misspell tongue)8 and feel I should not do so.

After some kind of meal, in frantic haste to go out again on the same hot hills with my net, search and search (probably because my bladder is full) for my white cap, remembering how uncomfortable I was without it in the desert sun.

NB: dreams seem to come out in more detail and to be better recalled, since I started setting them down (like firms sending you their publicity after you bought something).

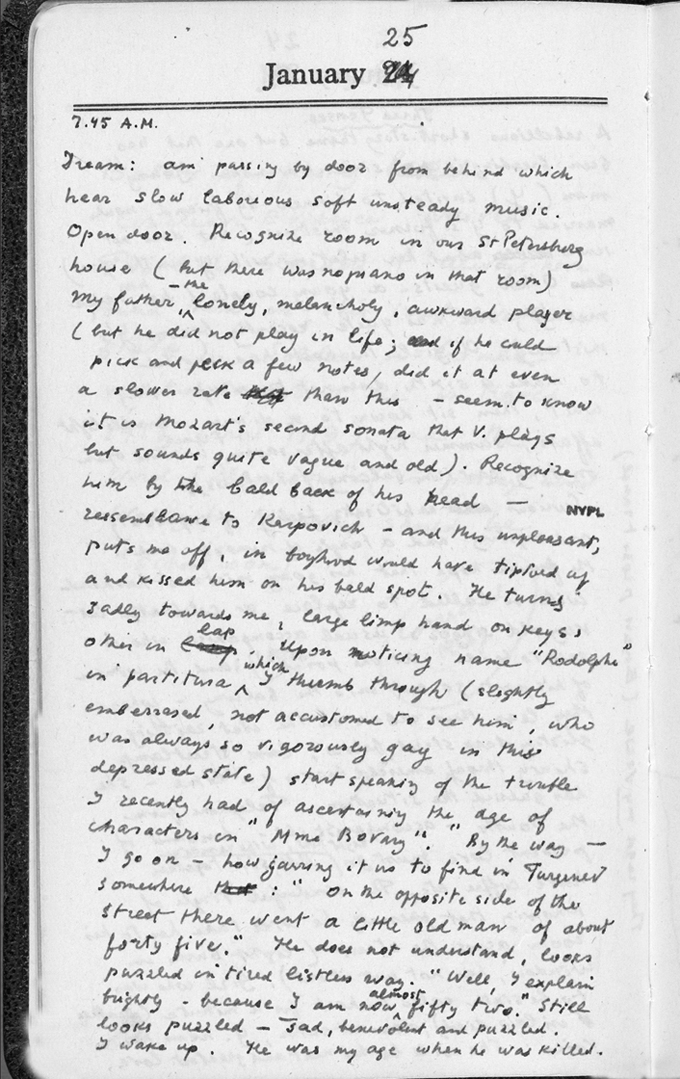

7.45 A.M.

Dream: am passing by door from behind which hear slow laborious soft unsteady music. Open door. Recognize room in our St Petersburg home (but there was no piano in that room). My father—the lonely, melancholy, awkward player (but he did not play in life; if he could pick and peck a few notes, did it at even a slower rate than this); seem to know it is Mozart’s second sonata that V. plays but sounds quite vague and old. Recognize him by the bald back of his head—resemblance to Karpovich9—and this <is> unpleasant, puts me off, in boyhood would have tiptoed up and kissed him on his bald spot. He turns sadly towards me, large limp hand on keys, other in lap. Upon noticing name “Rodolph” in partitura, which I thumb through (slightly embarrassed, not accustomed to see him, who was always so vigorously gay, in this depressed state) start speaking of the trouble I recently had of ascertaining the age of characters in “Mme Bovary.”10 By the way—I go on—how jarring it is to find in Turgenev somewhere:

“On the opposite side of the street there went a little old man of about forty-five.”11 He does not understand, looks puzzled in tired listless way. “Well, I explain brightly, because I am now almost fifty-two.” Still looks puzzled, sad, benevolent and puzzled. I wake up. He was my age when he was killed.

FIGURE 15A. A page from Nabokov’s 1951 diary.

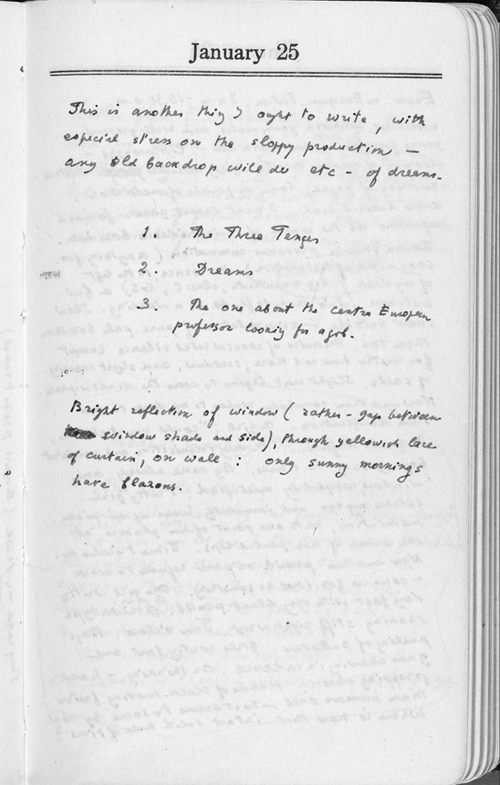

FIGURE 15B. “This is another thing I ought to write . . .”

The age coincidence is exact almost to the day: V. D. Nabokov was ninety-two days short of his fifty-second birthday when he was killed on March 28, 1922; his son, when he had this dream, was at an eighty-eight-day remove from his fifty-two. Cf. Dream 38 and also Fyodor Godunov-Cherdyntsev’s dream in the last chapter of The Gift.

The age coincidence is exact almost to the day: V. D. Nabokov was ninety-two days short of his fifty-second birthday when he was killed on March 28, 1922; his son, when he had this dream, was at an eighty-eight-day remove from his fifty-two. Cf. Dream 38 and also Fyodor Godunov-Cherdyntsev’s dream in the last chapter of The Gift.

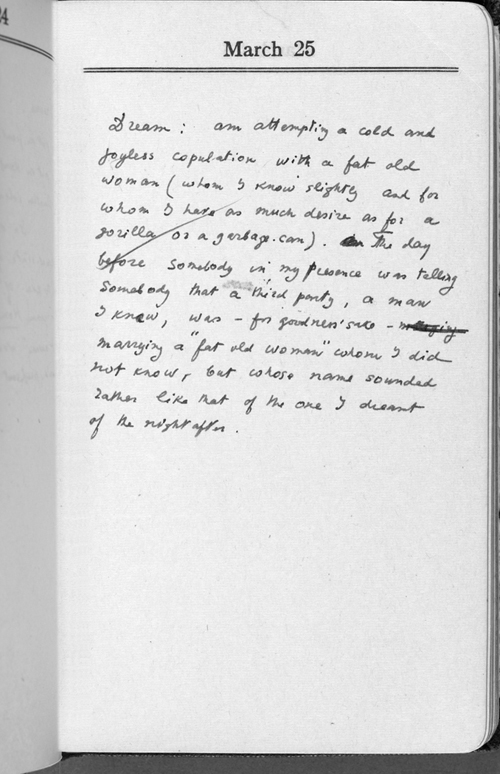

IV. March 25

Dream: am attempting a cold and joyless copulation with a fat old woman (whom I know slightly and for whom I have as much desire as for a gorilla or a garbage can). The day before somebody in my presence was telling somebody that a third party, a man I know, was—for goodness’ sake—marrying a “fat old woman” whom I did not know, but whose name sounded rather like that of the one I dreamt of the night after.

March 23

Dreams: when young “forgot to put on pants,” now “forgot to put on dentures.”

Another idea:

In our dreams we are in the normal state of rudimentary man, on the eve of its being transferred into the genus Homo. Not sapiens but “awake” would be a better name for man’s present condition.

[1963]

V. May. 27 Monday. Dreamed that Kerenski was dead.12

FIGURE 16. A dream of erotic “tenderness.”

[1965]

VI. April 23, мое рождение [my birthday]

Dream

My name is Austin Tailor! cries woman from newsstand where I had asked for Rumanian paper but then for NyTimes (and finally realize she had given me Pall Mall something).

[1966]

VII. January 7

Dream: the solution of the supreme mystery which we learn after death is that the cosmos with all its galaxies is a blue drop in the hollow of my palm (thus deprived of all the terrors of infinity). Simple.

VIII. April 3, 7.30 AM

Dream end: George Hessen13 telling latest anecdote, its “point” being street children replying to social worker: “let’s go to Seven Chops”—a disreputable dilapidated part of the town in the dream.

[1971]

IX. March 11

Покинуть все—работу, нҌгу,

искусство, милую скудель!

такъ Пушкинъ Ҍхалъ на дуэль.

Half of it in dream.

Leave everything—work, pleasure,

Art’s precious brittleness?

Over the snow that flushed pink, thus

Pushkin was driving to the duel.14

[1973]

X. 6 Jan 1973

Dream: my father had come with Dm. and me to the beach (there was, it turned out, a southern sea behind our Montreux Palace). Dm. and I were worried that my father (looking very gloomy and uncomfortable) would get badly sunburnt.

XI. Jan 9

Dream: Railway station in Italian city. V & I have been shopping. Are about to take a local train back to our mountain resort. I’m buttonholed on the platform by an American tourist. V. calls me as she boards the train. I get rid of the bore too late the train has gone. There’s another soon but I can’t recall the name of the resort. It begins with A—that’s all I know. Unhelpfully helpful station master. I cannot remember the Italian for “time table” but he keeps showing me long lists of complex freight car numbers. I wake up in angry panic.

Woke up at dawn. With diurnal part of brain still in dream gear. “That’s it!” I thought grimly as I sat up and saw that in the space between bed and window TWO guillotines, facing each other, had already been set (“That’s the way they do it, of course—in one’s bedroom”). Vertical and horizontal shadows in the barred and broken twilight, that I can never get accustomed to, kept imitating the horrible machines for at least five seconds. I had even time to wonder if V. in the adjacent bedroom was being prepared to join me. I should get thick curtains but I don’t like to wait for sleep in total darkness.

XIII. October 10

Queer dream on threshold of awakening. Was reminding A. Zak15 of the word games we played when he was my pupil 50 years ago and invented a new specimen which I managed to carry into consciousness:

МаЙЕРУ С АЛИМентами не повезло.

The Russian phrase reads “Meyer had bad luck with alimonies”; the capital letters yield the word “Jerusalem.” A roughly similar English wordplay can be shown in “No more sleep-walking-related inJURIES—A LIMited time offer.”

The Russian phrase reads “Meyer had bad luck with alimonies”; the capital letters yield the word “Jerusalem.” A roughly similar English wordplay can be shown in “No more sleep-walking-related inJURIES—A LIMited time offer.”

The day before, Nabokov mailed five hundred dollars to the Israeli ambassador in Berne, “a small contribution to your country’s defence against the Arabolshevist aggressors.” Mark the portmanteau. The third Arab-Israeli war began October 6 that year.

XIV. June 17

Dream: passing across football field where Pélé <sic> is kicking the ball about. Shoots it towards me with strong twist. I goal lunge—and almost break my hand against bedside table.

[1976]

XV. April 24

At 1 AM was roused from brief sleep by horrible anguish of the “this-is-it” sort. Discreetly screamed, hoping to wake Vé in the next room, yet fearing to succeed (because I felt quite all right).

The following surprisingly few dream descriptions do not include very frequent “I’ve seen you in my dream” instances.

The following surprisingly few dream descriptions do not include very frequent “I’ve seen you in my dream” instances.

“I dreamt of you last night—as if I was playing the piano and you were turning the pages for me . . .” (12 Jan. 1924)

“I dreamt that I was walking along the Palace Embankment with someone, the water in the Neva is lead-coloured, flowing thickly, and there are masts, masts without end, large boats and small ones, colourful stripes of black pipes—and I say to my companion: “The Bolsheviks have such a big fleet!” And he replies: “Yes, that’s why they had to remove the bridges.” After that we walked around the Winter Palace, and for some reason it was purple all over—and I thought that I must note this down for a short story. We stepped out into the Palace Square—it was squeezed from all sides by buildings, some kind of fantastic lights were playing. And my entire dream was lit up by some threatening light—the kind you find in battle paintings.” (16.6.1926)

Nabokov’s terse response to “Your most memorable dream” question, from a literary salon-type questionnaire (in Berlin in 1926), was: “Russia.”

Nabokov’s terse response to “Your most memorable dream” question, from a literary salon-type questionnaire (in Berlin in 1926), was: “Russia.”

“When I was little, I always used to dream of an enormous flood: so that I could take a boat ride down Morskaya, make a turn. . . . Street-lamps are sticking out of the water, further on, a hand sticks out: I approach it—and it turns out to be Peter’s bronze hand!” (2 July 1926—NB. The last item of his cryptogram—“So long!”)

“As for the question, ‘What is your most memorable dream?’ both Gurevich and I happened to write the same thing: Russia.” (17 July 1926)

“I dreamt that my little boy was sick, and stepped out of the dream as if out of hot salted water. I love you.” (17.2.1936)

“I dreamt last night that my little one was walking towards me along the pavement, with dirty cheeks, for some reason, and in a dark little coat; I ask him about myself: “Who is it?” and he replies: Volodya Nabokov, with a cunning little smile.” (15.5.1937)

“This morning I was awoken by an unusually lively dream: Ilyusha (I think it was he) walks in and says that he’d been informed by phone that Khodasevich “has ended his earthly existence”—word for word.” (9 June 1939, the last recorded dream in his letters to his wife)

Compared to either the original Conclusive Evidence (1951) or to the enlarged Speak, Memory (1965), the Russian version of Nabokov’s novelized autobiography entitled Drugie berega (Other Shores, 1954) differs significantly: some passages are missing, others were written specially for it and are unavailable in English. In the extensive passage concerning his early struggle with insomnia given below, the Russian text is much richer in detail; the two major insertions, in italics, are given in my translation. It is most interesting to note that whereas in later years Nabokov would not be able to fall asleep when even the dimmest light reached him in his bed (cf., for example, detailed description of his tussle with curtains in his last novel given in part 4 of this book, p. 128), in his childhood the exact opposite, total impenetrable darkness, was his dreaded nightly torment.

Compared to either the original Conclusive Evidence (1951) or to the enlarged Speak, Memory (1965), the Russian version of Nabokov’s novelized autobiography entitled Drugie berega (Other Shores, 1954) differs significantly: some passages are missing, others were written specially for it and are unavailable in English. In the extensive passage concerning his early struggle with insomnia given below, the Russian text is much richer in detail; the two major insertions, in italics, are given in my translation. It is most interesting to note that whereas in later years Nabokov would not be able to fall asleep when even the dimmest light reached him in his bed (cf., for example, detailed description of his tussle with curtains in his last novel given in part 4 of this book, p. 128), in his childhood the exact opposite, total impenetrable darkness, was his dreaded nightly torment.

All my life I have been a poor go-to-sleeper. All my life I went to sleep with the greatest of difficulties and with disgust. A fellow train passenger who puts aside a newspaper and without any trouble is snoring the next moment is as incomprehensible to me as are people who, say, “run for an office,” or enter a masonic lodge, or join any organization in order to dissolve in them energetically. I know that sleep is good for us, yet I can’t get accustomed to this betrayal of one’s reasoning, to that nightly and rather grotesque breaking up with one’s consciousness. In later years it felt somewhat like the feeling before surgery with full anesthesia, but in my childhood the forthcoming sleep appeared as a masked executioner. . . . No matter how great my weariness, the wrench of parting with consciousness is unspeakably repulsive to me. I loathe Somnus, that black-masked headsman binding me to the block; and if in the course of years I have got so used to my nightly ordeal as almost to swagger while the familiar axe is coming out of its great velvet-lined case, initially I had no such comfort or defense: I had nothing—save a door left slightly ajar into Mademoiselle’s room. Its vertical line of meek light was something I could cling to, since in absolute darkness my head would swim, just as the soul dissolves in the blackness of sleep.

Saturday night used to be a pleasurable prospect because that was the night Mademoiselle indulged in the luxury of a weekly bath, thus granting a longer lease to my tenuous gleam. But then a subtler torture set in. The nursery bathroom in our St. Petersburg house was at the end of a Z-shaped corridor some twenty heartbeats’ distance from my bed, and between dreading Mademoiselle’s return from the bathroom to her lighted bedroom and envying my brother’s stolid snore, I could never really put my additional time to profit by deftly getting to sleep while a chink in the dark still bespoke a speck of myself in nothingness. At length they would come, those inexorable steps, plodding along the passage and causing some little glass object, which had been secretly sharing my vigil, to tinkle in dismay on its shelf. Now she has entered her room. A brisk interchange of light values tells me that the candle on her bed table takes over the job of the lamp on her desk. My line of light is still there, but it has grown old and wan, and flickers whenever Mademoiselle makes her bed creak by moving. For I still hear her. Now it is a silvery rustle spelling “Suchard”; now the trk-trk-trk of a fruit knife cutting the pages of La Revue des Deux Mondes. I hear her panting slightly. And all the time I am in acute distress, desperately trying to coax sleep, opening my eyes every few seconds to check the faded gleam, and imagining paradise as a place where a sleepless neighbor reads an endless book by the light of an eternal candle.

The inevitable happens: the pince-nez case shuts with a snap, the review shuffles onto the marble of the bed table, and gustily Mademoiselle’s pursed lips blow; the first attempt fails, a groggy flame squirms and ducks; then comes a second lunge, and light collapses. In that pitchy blackness I lose my bearings, my bed seems to be slowly drifting, panic makes me sit up and stare. Lord, don’t they know that I can’t sleep without a point of light—that raving madness and death are nothing else but this perfectly black blackness! But gradually my dark-adapted eyes sift out, among entoptic floaters, certain more precious blurrings that roam in aimless amnesia until, half-remembering, they settle down as the dim folds of window curtains behind which streetlights are remotely alive. (“Mademoiselle O.”)16

1. This could be Anna Feigin (see p. 70, note 58).

2. A cast-iron balcony with wet railing appears in the same notebook two weeks afterward, in a sketch for his short story “Three Tenses,” never fleshed out (but used twenty years later in Transparent Things).

3. Cf. the classical French Revolution dream that Florensky adduces (p. 18)

4. Konstantin Solntzev (1894–1961), a bibliophile and philanthropist, later professor at Syracuse University. Nabokov had not known him before 1949, when he received a letter from Solntzev informing him that some of his papers were in VN’s possession, including some letters from VN’s mother. For more on this see V. V. Nabokov: Pro et Contra, vol. 2. (St. Petersburg: The Russian Christian Institute for the Humanities, 2001), 84–87.

5. A large number of moth species, all monofagous, feed on Artemisia plants.

6. A favorite Nabokov trope, his short story “Assistant Producer” (1943) being in a sense an extended essay on the metaphor.

7. Evgenia Konstantinovna Hofeld (1884–1957), his mother’s long-standing companion.

8. Here, too: he gets it right on the third try.

9. Mikhail Karpovich: see p. 87, note 87.

10. Nabokov analyzed Flaubert’s novel in his course on literary masterpieces, taught at Cornell from 1949 on.

11. There is a close enough passage in Turgenev’s Nest of the Gentlefolk (1859): “Next to her was sitting a wizened, jaundiced woman of about forty-five, in a low-cut dress and a black toque, with a toothless smile on her tense, worried, and vacuous face . . .” Pavel Kirsanov, a character in his Fathers and Sons (1860), which Nabokov also taught at Cornell, is also “a man of about forty-five.”

12. Alexander Kerenski, a Russian Socialist revolutionary, prime minister of the Provisional Government from July to October 1917, died in New York in 1970.

13. George Hessen (1902–1971), translator, VN’s close friend.

14. Nabokov translated that “versicle,” as he called it, later, on October 15, 1975.

15. Alexander Zak (1910–?), VN’s pupil in Berlin.

16. Stories, 488.