CHAPTER 8

Gaining Traction in a Crowded Market

Frosty ice climbers on a mountain pick axe their way through a frozen waterfall and emerge in a rowdy bar, heroes with ice-cold beers in hand. Crest-fallen couch potatoes watching their team fumble a football game light up as the pretty, smartest-person-in-the-room arrives with ice-cold beers in hand. Svelte young beauties strolling on the beach with ice cold beers. The world’s most interesting man pours a, you guessed it, ice cold beer. The world’s biggest beer companies spend $1 billion a year on this cast of characters to do one thing . . . and it is not to convince Americans to drink more beer.

Budweiser, Coors, Corona, Dos Equis, and other big beer brands use TV ads to try to convince each other’s fans to switch brands. They have been doing this for decades, grabbing and losing slivers of what is now a fast shrinking group of old fashioned beer drinkers. And yet, these multinational behemoths continue year after year to sell the fantasy of drinking really cold beverages to gain friends, have sex, and become a mock-sophisticate.

Jim Koch’s Boston Beer is the only craft beer company to ever launch a TV ad campaign. His early efforts using humor and sex appeal failed. Now he sells the taste of Sam Adams beer, an inside look at the traditional beer-making process and the difference high-quality ingredients make in beer. He sells to a smart audience that values authenticity.

The rest of the craft breweries take pride in not advertising to mass audiences. Sierra Nevada’s Ken Grossman claims to have never bought a mass-market ad. Period. No national magazines, newspapers, or television. He likes the personal touch, local media outlets reaching local beer drinkers. To open his second Sierra Nevada brewery in Ashland, North Carolina, in 2014, Grossman organized an elaborate summer-long bus tour across the country, staging a string of beer festivals, and all along the way he joined his friends at their craft breweries to brew limited production cooperative beers. The festivals and one-off beers demonstrated the camaraderie within the craft community and brought craft fans together to drink lots of craft beer.

It also “almost killed me,” says Grossman. It took an enormous amount of time and energy on the part of the Sierra Nevada staff and, in the end, celebrated hard-core fans while ignoring the 90 percent of America that doesn’t drink craft beer. Grossman swears he will never do anything like it again. And yet he still maintains his no-mass-marketing dictum.

Push will soon come to shove at Sierra Nevada and every other large craft brewery. They built their fanbase by handing curious people beers that tasted nothing like the beers they’d had before. Those folks told their friends about these wonderful new beers and, one by one, the craft beer audience grew. And then it stalled, and the flat line stretched to the dawn of social media in the mid-2000s. “The industry came alive with social media,” says David Walker, cofounder of Walker Firestone Brewery. “It was a true multiplier.” The explosion in craft beer popularity continues to grow as a new generation of fans share their craft discoveries more easily with more friends.

They may not realize it yet, but the national craft brands will take the next step up the marketing ladder and create national mass-market advertising campaigns. Founders like Grossman will hate it, but they have no choice but to follow Koch’s lead if they want to keep growing. “Craft has momentum in a flat beer market because there is a generation of transformed palates,” Craft Brew Alliance CEO Andy Thomas told a recent Brewbound conference. Now, craft needs to grow up and start acting like the beer market leader it is. “We need to reach beer drinkers in grocery stores, convenience stores, Costco, and Walmart. We need a national footprint.” To those who disdain Big Beer’s flashy television ads, Thomas says, “We have to be involved in shaping the future of beer. You are the stewards of the beer industry identity of tomorrow.”

Boston Beer’s Koch “swore he would never sell Sam Adams in a can,” says Lester Jones, chief economist for the National Beer Wholesalers Association. But when he wanted to have his beers on airplanes, in airports and convenience stores and outdoor events, he put Sam Adams in a can. Sierra Nevada is an outdoor brand and, naturally, the company sponsors hiking, biking, and wilderness events. “Cans are the superior package for an outdoor beer,” he says. But the company refused to offer their beer in cans until the last couple of years. Now, its 12-pack of cans is a big seller in the craft category. “It’s the most significant thing they have done” to support the brand, he says.

tip

Don’t be shy about making a little noise about your brew. “How brewers support their brands in the marketplace is critical to a distributor’s ability to sell that brand,” says Lester Jones with the National Beer Wholesalers Association. “Knowing that a brewer is doing something to support the brand, putting money into any type of advertising, makes sales to retailers so much easier. Wouldn’t your job be easier if there were ads for the beer you are selling playing on every TV in every bar you went into to sell that product?”

The craft guys started a revolution in beer. They’ve been aggressive, says Joe Thompson, a mergers and acquisitions consultant who often represents larger brewers and distributors. “Wholesalers fought back, but craft is winning. In the last five years, wholesalers and retailers have spent more time and attention on the craft category and taken time and attention away from Budweiser and Miller. Craft is eating Big Beer alive.

“Now that the big companies have lost enough volume, they are turning their big guns at the craft category. They are smart. They will use their scale to go after the craft business and price aggressively,” says Thompson. Expect many more purchases of craft brands by the multinational beer giants that respond to consumer demand for “local” products.

The big craft players are going to have to fight to keep growing. And those that have enjoyed being in a category that has done nothing but grow with consumers flocking to them, will be tested, Thompson says. Survival will depend on marketing muscles craft has not yet developed. “The brewers making a couple hundred thousand barrels will be fine, and the little bitty guys will be fine. In between is going to be a tough environment. Thirty-six percent of beer is drunk by 22- to 34-year-olds, and only 2 percent of that group is loyal to a brand.”

tip

Make marketing a priority. “Craft beer no longer sells itself,” says University of California, Davis, professor emeritus Michael Lewis. “It’s harder and more expensive to sell your beer. At least 25 percent of your budget will go to marketing.”

Keith Lemcke, vice president of Chicago-based Siebel Institute of Technology and marketing manager for the World Brewing Academy, says marketing is now a dedicated position at even the smallest breweries and distilleries. “This person operates effective social media, trains sales staff in stores, trains bartenders, and grocery store workers. You have to have a marketing person from the start with an effective approach. Price competition is creeping in among the bigger craft brewers. You have to be prepared to respond.” In other words, be ready to sell your brand and pivot your message on a dime.

What Is Branding, Exactly?

Let’s take a look at the basics of branding, courtesy of the expert branders themselves, the team at Entrepreneur. They will walk you through the basics of branding in the next three sections (“What is Branding, Exactly?,” “Building a Branding Strategy,” and “Bringing It All Together.”)

Branding is a very misunderstood term. Many people think of branding as just advertising or a really cool-looking logo, but it’s much more complex—and much more exciting, too.

Branding is your company’s foundation. Branding is more than an element of marketing, and it’s not just about awareness, a trademark, or a logo. Branding is your company’s reason for being, the synchronization of everything about your company that leads to consistency for you as the owner, your employees, and your potential customers. Branding meshes your marketing, public relations, business plan, packaging, pricing, customers, and employees.

Branding is your company’s foundation. Branding is more than an element of marketing, and it’s not just about awareness, a trademark, or a logo. Branding is your company’s reason for being, the synchronization of everything about your company that leads to consistency for you as the owner, your employees, and your potential customers. Branding meshes your marketing, public relations, business plan, packaging, pricing, customers, and employees.

Branding creates value. If done right, branding makes the buyer trust and believe your product is somehow better than those of your competitors. Generally, the more distinctive you can make your brand, the less likely the customer will be willing to use another company’s product or service, even if yours is slightly more expensive. “Branding is the reason why people perceive you as the only solution to their problem,” says Rob Frankel, a branding expert and author of The Revenge of Brand X: How to Build a Big Time Brand on the Web or Anywhere Else. “Once you clearly can articulate your brand, people have a way of evangelizing your brand.”

Branding creates value. If done right, branding makes the buyer trust and believe your product is somehow better than those of your competitors. Generally, the more distinctive you can make your brand, the less likely the customer will be willing to use another company’s product or service, even if yours is slightly more expensive. “Branding is the reason why people perceive you as the only solution to their problem,” says Rob Frankel, a branding expert and author of The Revenge of Brand X: How to Build a Big Time Brand on the Web or Anywhere Else. “Once you clearly can articulate your brand, people have a way of evangelizing your brand.”

Top 15 New Craft Beer Brands Released in 2014—Supermarket Sales

Top 15 New Craft Beer Brands Released in 2014—Supermarket Sales

1. Samuel Adams Rebel IPA—$21,116,309

2. Sierra Nevada variety pack—$11,374,208

3. New Belgium Snapshot Wheat—$4,530,783

4. Deschutes Fresh Squeezed IPA—$3,065,053

5. Stone Go To IPA—$2,019,261

6. New Belgium Special Release—$753,641

7. Sierra Nevada Beer Camp Across America—$722,419

8. Anchor IPA—$698,488

9. Dogfish Head Namaste Witbier—$667,338

10. Cigar City Invasion Pale Ale—$542,432

11. Ommegang Game of Thrones Fire and Blood—$423,127

12. Ommegang Game of Thrones Valar Morghulis—$414,994

13. Small Town Not Your Father’s Root Beer—$413,540

14. Ballast Point Grapefruit Sculpin IPA—$378,418

15. Rhinegeist Truth IPA—$363,303

Source: IRI supermarket sales data, released March 2015

Branding clarifies your message. You have less money to spend on advertising and marketing as a startup entrepreneur, and good branding can help you direct your money more effectively. “The more distinct and clear your brand, the harder your advertising works,” Frankel says. “Instead of having to run your ads eight or nine times, you only have to run them three times.”

Branding clarifies your message. You have less money to spend on advertising and marketing as a startup entrepreneur, and good branding can help you direct your money more effectively. “The more distinct and clear your brand, the harder your advertising works,” Frankel says. “Instead of having to run your ads eight or nine times, you only have to run them three times.”

Branding is a promise. At the end of the day, branding is the simple, steady promise you make to every customer who walks through your door—today, tomorrow, and ten years from now. Your company’s ads and brochures might say you offer speedy, friendly service, but if customers find your service slow and surly, they’ll walk out the door feeling betrayed. In their eyes, you promised something that you didn’t deliver, and no amount of advertising will ever make up for the gap between what your company says and what it does. Branding creates the consistency that allows you to deliver on your promise over and over again.

Branding is a promise. At the end of the day, branding is the simple, steady promise you make to every customer who walks through your door—today, tomorrow, and ten years from now. Your company’s ads and brochures might say you offer speedy, friendly service, but if customers find your service slow and surly, they’ll walk out the door feeling betrayed. In their eyes, you promised something that you didn’t deliver, and no amount of advertising will ever make up for the gap between what your company says and what it does. Branding creates the consistency that allows you to deliver on your promise over and over again.

Building a Branding Strategy

Your business plan should include a branding strategy. This is your written plan for how you’ll apply your brand strategically throughout the company over time.

At its core, a good branding strategy lists the one or two most important elements of your product or service, describes your company’s ultimate purpose in the world, and defines your target customer. The result is a blueprint for what’s most important to your company and to your customer.

Don’t worry; creating a branding strategy isn’t nearly as scary or as complicated as it sounds. Here’s how:

Step one. Set yourself apart. Why should people buy from you instead of the same kind of business across town? Think about the intangible qualities of your product or service, using adjectives from “friendly” to “fast” and every word in between. Your goal is to own a position in the customer’s mind so they think of you differently than the competition. “Powerful brands will own a word—like Volvo [owns] safety,” says Laura Ries, an Atlanta marketing consultant and co-author of The 22 Immutable Laws of Branding: How to Build a Product or Service into a World-Class Brand. Which word will your company own? A new hair salon might focus on the adjective “convenient” and stay open a few hours later in the evening for customers who work late—something no other local salon might do. How will you be different from the competition? The answers are valuable assets that constitute the basis of your brand.

Step one. Set yourself apart. Why should people buy from you instead of the same kind of business across town? Think about the intangible qualities of your product or service, using adjectives from “friendly” to “fast” and every word in between. Your goal is to own a position in the customer’s mind so they think of you differently than the competition. “Powerful brands will own a word—like Volvo [owns] safety,” says Laura Ries, an Atlanta marketing consultant and co-author of The 22 Immutable Laws of Branding: How to Build a Product or Service into a World-Class Brand. Which word will your company own? A new hair salon might focus on the adjective “convenient” and stay open a few hours later in the evening for customers who work late—something no other local salon might do. How will you be different from the competition? The answers are valuable assets that constitute the basis of your brand.

Step two. Know your target customer. Once you’ve defined your product or service, think about your target customer. You’ve probably already gathered demographic information about the market you’re entering, but think about the actual customers who will walk through your door. Who is this person, and what is the one thing he or she ultimately wants from your product or service? After all, the customer is buying it for a reason. What will your customer demand from you?

Step two. Know your target customer. Once you’ve defined your product or service, think about your target customer. You’ve probably already gathered demographic information about the market you’re entering, but think about the actual customers who will walk through your door. Who is this person, and what is the one thing he or she ultimately wants from your product or service? After all, the customer is buying it for a reason. What will your customer demand from you?

Step three. Develop a personality. How will you show customers every day what you’re all about? A lot of small companies write mission statements that say the company will “value” customers and strive for “excellent customer service.” Unfortunately, these words are all talk, and no action. Dig deeper and think about how you’ll fulfill your brand’s promise and provide value and service to the people you serve. If you promise quick service, for example, what will “quick” mean inside your company? And how will you make sure service stays speedy? Along the way, you’re laying the foundation of your hiring strategy and how future employees will be expected to interact with customers. You’re also creating the template for your advertising and marketing strategy.

Step three. Develop a personality. How will you show customers every day what you’re all about? A lot of small companies write mission statements that say the company will “value” customers and strive for “excellent customer service.” Unfortunately, these words are all talk, and no action. Dig deeper and think about how you’ll fulfill your brand’s promise and provide value and service to the people you serve. If you promise quick service, for example, what will “quick” mean inside your company? And how will you make sure service stays speedy? Along the way, you’re laying the foundation of your hiring strategy and how future employees will be expected to interact with customers. You’re also creating the template for your advertising and marketing strategy.

Top Ten New Craft Vendors Selling in IRI Tracked Supermarkets

Top Ten New Craft Vendors Selling in IRI Tracked Supermarkets

The number of craft brands sold in supermarkets increased sharply in 2014, to 735 compared to 595 in 2013 and 484 in 2012.

1. Rhinegeist Brewery, Cincinnati, Ohio—$782,539

2. Griffin Claw Brewing Company, Birmingham, Michigan—$570,128

3. Small Town Brewery, Wauconda, Illinois—$413,540

4. Gilgamesh Brewing, Salem, Oregon—$304,454

5. Exile Brewing Company, Des Moines, Iowa—$264,785

6. Belching Beaver Brewery, Vista, California—$225,979

7. Old Bust Head Brewing Company, Warrenton, Virginia—$208,175

8. Everybodys Brewing, White Salmon, Washington—$177,344

9. Pisgah Brewing Company, Black Mountain, North Carolina—$132,695

10. Grapevine Craft Brewery, Farmers Branch, Texas—$131,133

Source: IRI

Your branding strategy doesn’t need to be more than one page long at most. It can even be as short as one paragraph. It all depends on your product or service and your industry. The important thing is that you answer these questions before you open your doors.

Bringing It All Together

Congratulations—you’ve written your branding strategy. Now you’ll have to manage your fledgling craft brand. This is when the fun really begins. Here are some tips:

Keep ads brand-focused. Keep your promotional blitzes narrowly focused on your chief promise to potential customers. For example, a new brewery might see the open-view brewing/taproom as its greatest brand-building asset. Keep your message simple and consistent so people get the same message every time they see your name and logo.

Keep ads brand-focused. Keep your promotional blitzes narrowly focused on your chief promise to potential customers. For example, a new brewery might see the open-view brewing/taproom as its greatest brand-building asset. Keep your message simple and consistent so people get the same message every time they see your name and logo.

Be consistent. Filter every business proposition through a branding filter. How does this opportunity help build the company’s brand? How does this opportunity fit our branding strategy? These questions will keep you focused and put you in front of people who fit your product or service.

Be consistent. Filter every business proposition through a branding filter. How does this opportunity help build the company’s brand? How does this opportunity fit our branding strategy? These questions will keep you focused and put you in front of people who fit your product or service.

Shed the deadweight. Good businesses are willing to change their brands but are careful not to lose sight of their original customer base and branding message.

Shed the deadweight. Good businesses are willing to change their brands but are careful not to lose sight of their original customer base and branding message.

There’s a lot of work that goes into launching and building a world-class brand, but it pays off. Think of your fledgling brand as a baby you have to nurture, guide, and shape every day so it grows up to be dependable, hardworking, and respectable in your customers’ eyes. One day your company’s brand will make you proud. But you’ll have to invest the time, energy, and thought it takes to make that happen.

Getting Started

Now, you can apply that basic branding knowledge from Entrepreneur to the specific world of craft, accounting for the unique characteristics of this industry as you go.

You are entering a far more competitive sector than existed even five years ago. You must have a marketing strategy written into your business plan and that strategy has to be reflected in every decision you make. You are starting out behind many others. You will need to make a loud splash in the market to be heard above all the rest of the noise.

The old, slow way of selling beer by making great beer and gaining a solid following of people who want you to succeed still works, says BA’s Papazian. “That following will get you through the difficult times when you have to take a leap and spend more to grow to get to the next level.” And when you do spend money on marketing, it won’t be to buy ads. “It is investing in an employee who is on the street talking to retailers, going to beer festivals, talking to beer drinkers, building relationships with distributors and restaurants.”

Craft is personal. Craft is local. And craft fans still want to know who made the drink in their hand. Marketing a craft brand starts with understanding the founder’s story, which is a very different thing than deciding what that story should be. Why is this product being made here and now? What brought the founder to this place? Where does the founder want to take this enterprise? Is it the founder’s product, or is the brewmaster or distiller the soul of the brand? Answering these questions is an existential exercise that will ground the marketing in the company’s greater mission. When logos, websites, signage, and T-shirts reflect that mission in authentic ways, there is an opportunity to engage the all-important Millennial consumer.

“The first thing we had to do when we opened was to explain the product to consumers,” says Ralph Erenzo, founder of Hudson Valley’s Tuthilltown Spirits in Gardiner, New York. “The best person to do that is the distiller. What do we make? Why and how, the full story. When I went out to talk with people in bars, it was the first time anyone had ever met the person who made the spirits they were drinking. We’re going up against big brands with deep pockets and trying to push them aside on stores shelves. It is critical to be able to sell out of our tasting room where we have a face-to-face opportunity with the consumer. They walk out with a bottle, but they don’t come back to us for the next one. They take it to their local retailer and ask for it. We have to be there, too.”

To enhance the distillery experience for his customers, Erenzo is buying the gristmill next door to create a park so people can picnic when they visit. “It adds a tourist element. We want people to hang out, have lunch, throw rocks in the river, and experience our world.”

You may not have a beautiful location, but you can—and must—create a virtual reality for your brand that is appealing, welcoming, and engaging. Everything you do online should be considered part of your virtual reality.

Websites should be designed with the same sense of place that defines the brewery, distillery, or cidery. It is often the first “place” customers interact with a craft brand. The founder’s story should inform the look, feel, and messaging on the site, including the logo and product labels. When a website does not include photos of the founders or a sense of where the product is made, it is a lost opportunity to capture a critical selling point for craft and builds engagement with the brand.

Robust, thoughtful Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and other social media programs—a minimum marketing effort for any craft brand—should be designed to drive customers to the website where guests have the opportunity to engage more deeply with the brand. Measuring that engagement is critical to knowing if the website is serving its purpose. How long do guests stay on the site? Google analytics provides average length of time on the site. How deeply did the guest engage with the brand? Google analytics provides average number of site “pages viewed.”

No website is complete without providing fans with a way to stay connected to the brand. How many visitors “subscribe” when they visit the site? The list of subscribers is a valuable but fragile asset. Handled incorrectly, these fans will “unsubscribe” and be beyond reach. Offered engaging, relevant information and opportunities, they will share the brand’s emails with friends. Subscribers are invited to events featuring the brand and are the people most likely to ask for the brand at stores, restaurants, and bars.

Your online world will be particularly important before you open your real-world doors. To cultivate customers before they opened their doors in 2013, McMinnville, Oregon’s Grain Station Brew Works (http://grainstation.com) owners, Kelly McDonald and Mark Vickery, launched a “Community Supported Brewery Pubscription Plan.” Think of a weekly delivery of produce from a CSA (Community-Supported Agriculture), only this is a weekly allocation of beer available to members when they stop by the brewery. Pubscribers can sign up for various levels of commitment. For $250 a year, pubscribers got a pint glass, a T-shirt, and the right to weekly refills of a 23-ounce beer mug of their own at the brewpub. For $750, they got a weekly growler refill, plus a five-gallon take-home keg refilled monthly. For $2,500 a year, the top category, the pubscriber also bought the opportunity to help make beer at the brewery.

tip

Make your location serve as your company calling card. Pay attention to space and place, and it will pay off in sales. No sales effort is as effective as that of the Shanty, a bar that the New York Distilling Company operates at its Brooklyn distillery, with expansive picture windows overlooking the copper stills. Drinking the product locks the sale and cements the relationship with consumers.

The campaign provided a significant cash infusion just when unexpected last-minute bills were due. With the upfront cash and a $250,000 Small Business Administration loan and their personal savings, the pair was able to finance and build their brewpub in McMinnville’s downtown granary district in four months, from idea to grand opening.

“We allowed customers to take stock in the brewery themselves. To return often and feel a greater level of connectedness to the enterprise,” says Kelly McDonald. “They are a part of our brewery and, in turn, we are supporting local farms by buying their hops and barley to make our beer.” They’ve kept the interest high in their locally sourced beers through weekly music events, attended by pubscribers who receive regular MailChimp newsletters. From the start, beer sales have averaged $7,000 a week with another $18,000 in revenue from pizza and other pub food, according to McDonald.

The product must be center stage. Every shred of the marketing for Green Flash’s San Diego brewery is designed to engage customers directly with their beer, says Mike Hinkley, co-owner of the brewery. With a sister brewery now under construction in Virginia Beach, Virginia, he and his wife and partner Lisa are on the road all the time. “Our whole marketing strategy is about direct interaction with customers through events like South by Southwest in Austin. We stagger entering new states, building the brand in new markets one at a time. We’ll fly to a city for one beer dinner with 15 customers.

“We dedicate a lot of effort to that kind of marketing. We’re small—70,000 barrels a year—and we’re in 50 states. We’re building the brand this way to maintain the margins. We don’t discount. No time or money is spent on chain stores. We talk directly to our customers. We experience our beers with our customers, educating a core group of beer geeks and new people coming into the craft market.”

“People are curious. They want to experience new things. Men bring dates who have never experienced beer in this kind of environment. With 30 sales and marketing people around the country, we set a standard and give them guidelines and sales tools, then let them be creative in how they do their jobs,” says Lisa Hinkley. “Wherever we sell beer, it is at San Diego prices. We’re a national specialty brand.”

Having a partner like Allen Katz, head of mixology for distributor Southern Wine & Spirits, who is wired with the New York bartender network is critical, says Tom Potter, cofounder of New York Distilling Company. “We focus on ‘on-premises’ sales, and the cocktail culture is exploding in New York. We don’t have much of a marketing budget, a couple of thousand dollars a month for everything. Hopefully we will get big enough to be able to afford more. For now we rely on free publicity and word of mouth.” Media coverage, tasting events, and distillery tours are critical as well.

fun fact

Craft competitions and festivals are big business and well worth the time and effort. After all, word-of-mouth is driven by tasting, and what better way to cultivate that buzz than to interface with your potential customers. For a full list of national beer events, visit www.craftbeer.com/news-and-events/national-events. For a full list of cider festivals, visit www.ciderguide.com/cider-festivals/. Also, see the Appendix for a detailed list of festivals.

Craft competitions have been the critical marketing tool for Aurora, Colorado’s Dry Dock Brewing (http://drydockbrewing.com). Founders Kevin DeLange and Michelle Reding launched their brewery in 2005 next door to their homebrewing store. When their Dry Dock Beer earned top medals in beer competitions that first year, word spread through online beer websites and sales soared, enabling them to expand. More awards followed, and they expanded again. “We’ve followed demand,” says Reding. In Colorado, breweries are allowed to operate taprooms, so they could gauge consumer interest in a new beer and knew what worked immediately.

Their first brewery cost $80,000. By growing only in response to increased sales, they were able to finance each expansion with bank loans. Their latest expansion, in 2013, was into a new $4 million brewery capable of producing 60,000 barrels a year. From the start, their only marketing strategy was to participate in beer festivals and submit their beers to competitions, says DeLange. “We don’t do a lot of other marketing because we haven’t needed to do it. Winning gets you instant credibility and free advertising.” After their first medals, “we were on the front page of the business section of The Denver Post and The Rocky Mountain News. And our press coverage has never stopped because we continue to win awards.”

tip

Don’t discount the idea of going international. When Rabish learned American spirits are “incredibly hot overseas,” he pivoted to take advantage of the demand. “And we don’t have to pay a federal licensing tax when we sell outside the country,” he says. “The distributor pays for all the shipping, and I get paid within 30 days. Germany and Sweden are big accounts for us.”

If they decide to sell beer outside of Colorado, they say they might change their marketing philosophy. But that won’t happen any time soon. “We can’t make enough beer to satisfy demand in Colorado at this point,” says Reding. “If we go with one of the large distributors who are courting us, we’d be in a huge book with tons of other craft beer, spirits, and wine. We could get lost.”

Attend any kind of festival or trade show you can, says Kent Rabish, founder of Grand Traverse Distillery (www.grandtraversedistillery.com). “When we were brand new, I would attend the bigger shows, even before we had much product. A couple of visitors who came to the booth just happened to be Costco buyers. The next thing you know, we’re in five regional Costco locations in Michigan. They wanted ‘craft’ regional products to create a point of difference with other big chain stores.

“Our marketing budget has always been very small. If Absolut comes out with a new flavor of vodka, they support it with a $200,000 marketing push in Michigan alone. We started advertising in magazines and quickly realized it was a mistake. It was too hard to tie the expense directly to sales. Our other big mistake was paying sales reps a commission on stocking, not on sales. So for every store they put our products in, they got a fee, even when the product went into the wrong stores and just sat there collecting dust.”

Distribution Means Marketing

No matter the state, at a certain point, alcoholic beverage producers who want to grow must sell their products through an independent alcoholic beverage distributor. The three-tier system—independent producers, distributors, and retailers—is a fundamental tenant of American alcoholic beverage law. Distributors become one of the faces of a brand in their region and handle critical sales and marketing functions.

Even in states that allow self-distribution, once a brewer, distiller, or cider maker reaches a certain size, most want to stop schlepping bottles and kegs around in the back of their SUVs. If nothing else, they want someone else to take care of collecting overdue bills. Finding the right entity to handle those functions is challenging.

The relationship between producers and distributors is highly regulated in ways that sometimes make little sense. Obscure state laws may trump what is written in a duly signed contract. This is a relationship that must be discussed with a legal advisor well versed in alcoholic beverage distribution. All proposed contracts need to be reviewed by legal counsel. With laws varying state-by-state, frequently distributors are as unaware of them as the novice producer. Regardless, significant damage can be done that can haunt businesses for years.

Know your options. Meet with as many of the distributors in your region as you can and learn their sales philosophy. Does it match up with yours? Who else do they represent? Ask those producers if they are happy with the distributor’s efforts. Would they change, if they could? To which other distributor? Why? You are hiring the distributor to be part of your team. Be sure you trust them with the future of your company.

Frustrated with its lack of a good distribution option, Brooklyn Brewery created its own distribution company in the 1990s, operating it separately from the brewery. “We sold our distribution company for $12 million in 2004,” says cofounder Steve Hindy. “Big distributors are eager to represent craft now. We no longer go to them on bended knee. Now they come to us.” It is still a fraught relationship. Distributors are dealing with more brands, more products than they may be equipped to handle. “The coming shakeout in craft beer,” says Hindy, “may well come down to who gets good distribution and who doesn’t.”

Stone Brewing Company also built its own separate distribution company. “We had no other choice but to become distributors. No wholesaler would distribute our beer. It was extremely financially burdensome to build it,” says Stone Brewing cofounder Greg Koch. “Then after a year and a half, we turned the corner on it and it became viable.” Launched in 1996, Stone Distributing now represents 35 craft brands throughout a 40,000-square-mile footprint in Southern California with a population of 20 million. Industry analysts estimate Stone’s distributing company would be worth $100 million if they sold it today. “We know how to take care of beer. We have the largest refrigerated fleet in Southern California, perhaps the country.”

“A distributor who passed on us gave me a pat on the head and told me we were going nowhere. Well, that distributor is out of business today, and we’re doing just fine. Access to the market has always been challenging for craft. It’s just that the character of the challenge has changed. It used to be they didn’t understand our beers. Now there is lots of interest in our beers, but it is an extremely crowded market and consumers have a lot of choices,” says Koch. The friction is on the store shelf and in the bar taps.

aha!

“The best marketing for craft is to open your doors. Big beer companies market their crafty beers with obfuscation and sleight of hand. Truth and justice are on our side,” says Greg Koch, cofounder of Stone Brewing.

“As craft beer emerged in the 1990s, the little distributors took the craft beers no one else wanted,” says Dennis Hartman, head of the craft beer and spirits division at California distributor Wine Warehouse. “It was hard at first. Wine Warehouse never had any of the big beers; we were always the alternative network. As craft grew, it was our whole portfolio. It wasn’t easy but we were poised for what is happening now. We have 40 to 50 American craft beers, 35 Germans, 60 Belgians. Our book is really big.

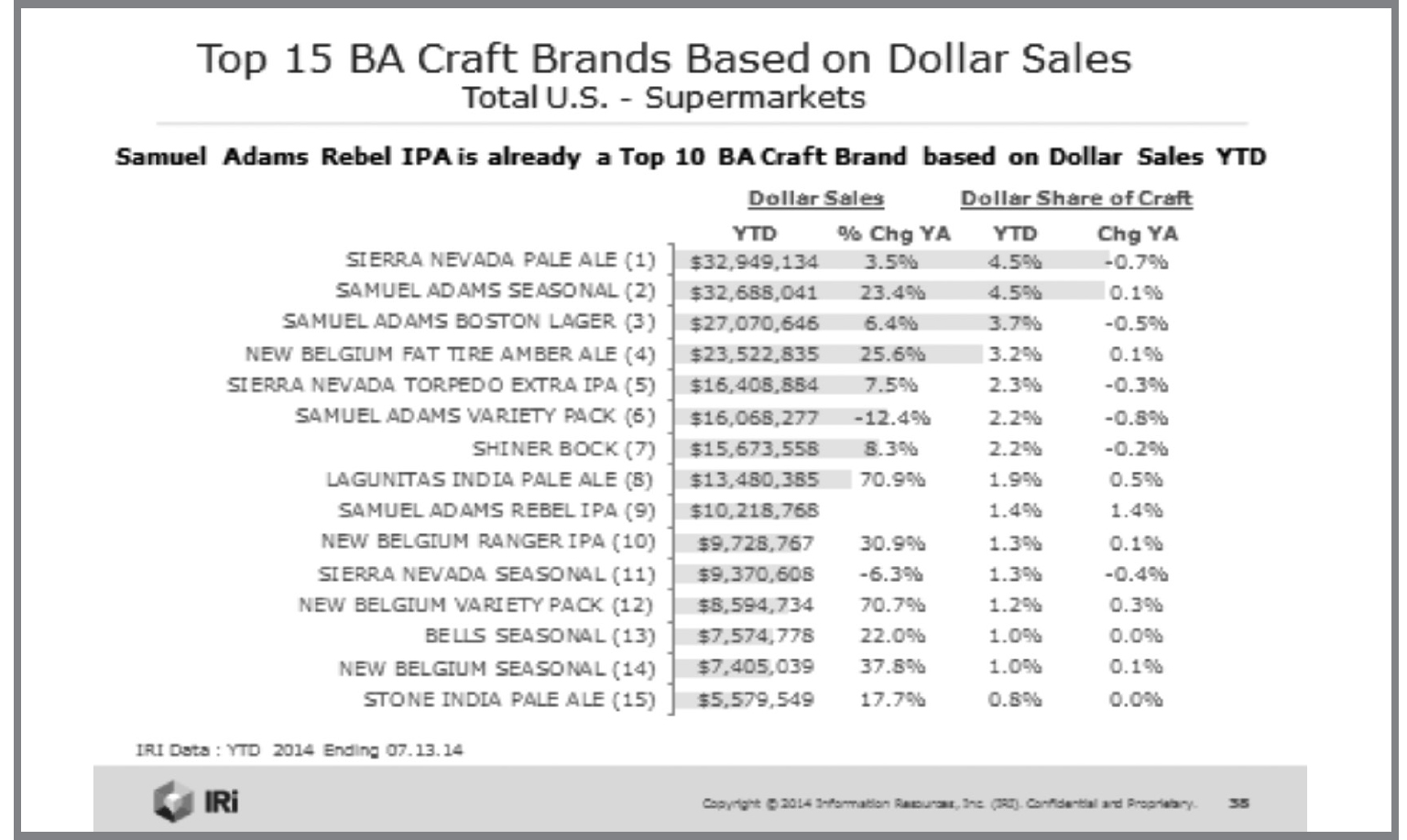

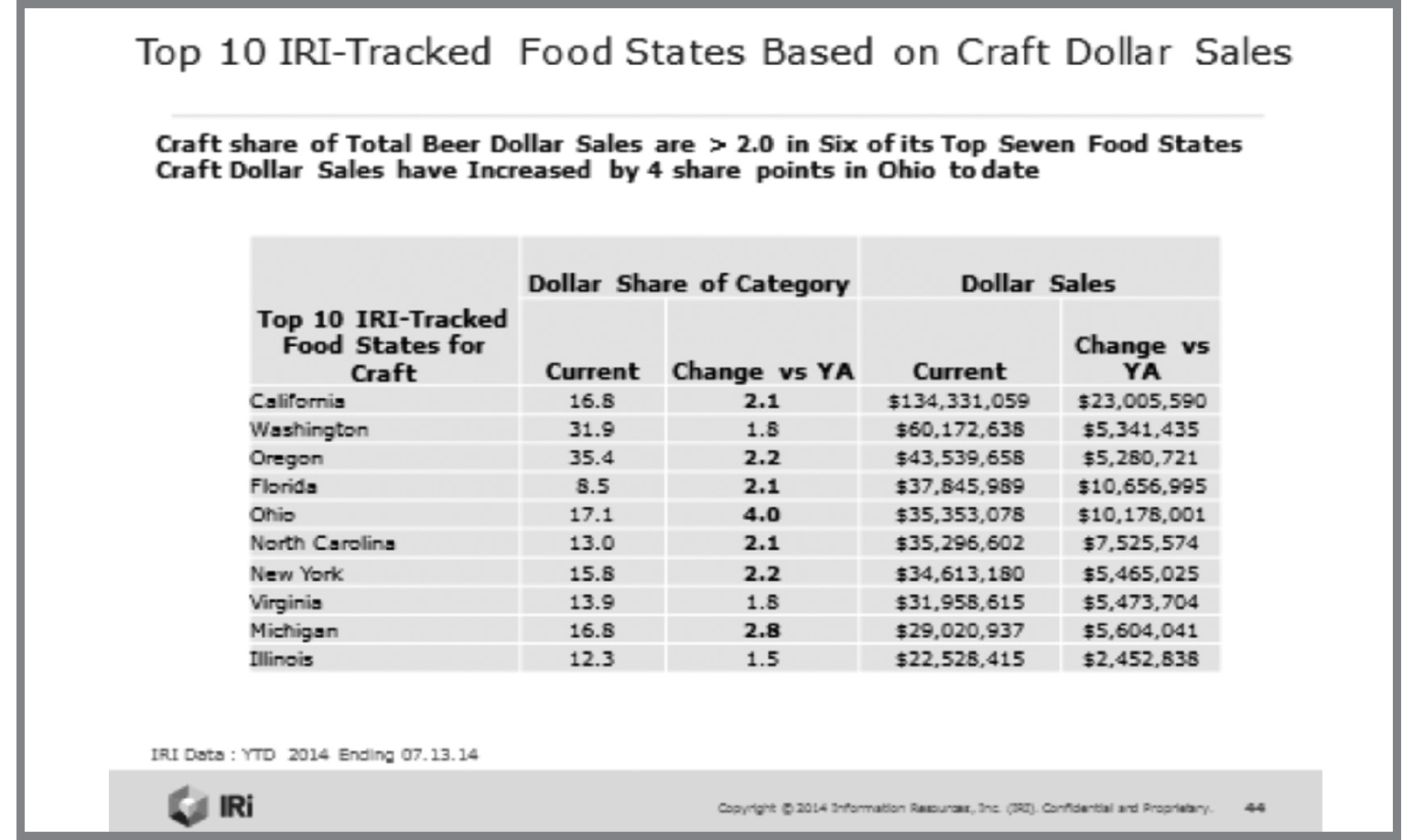

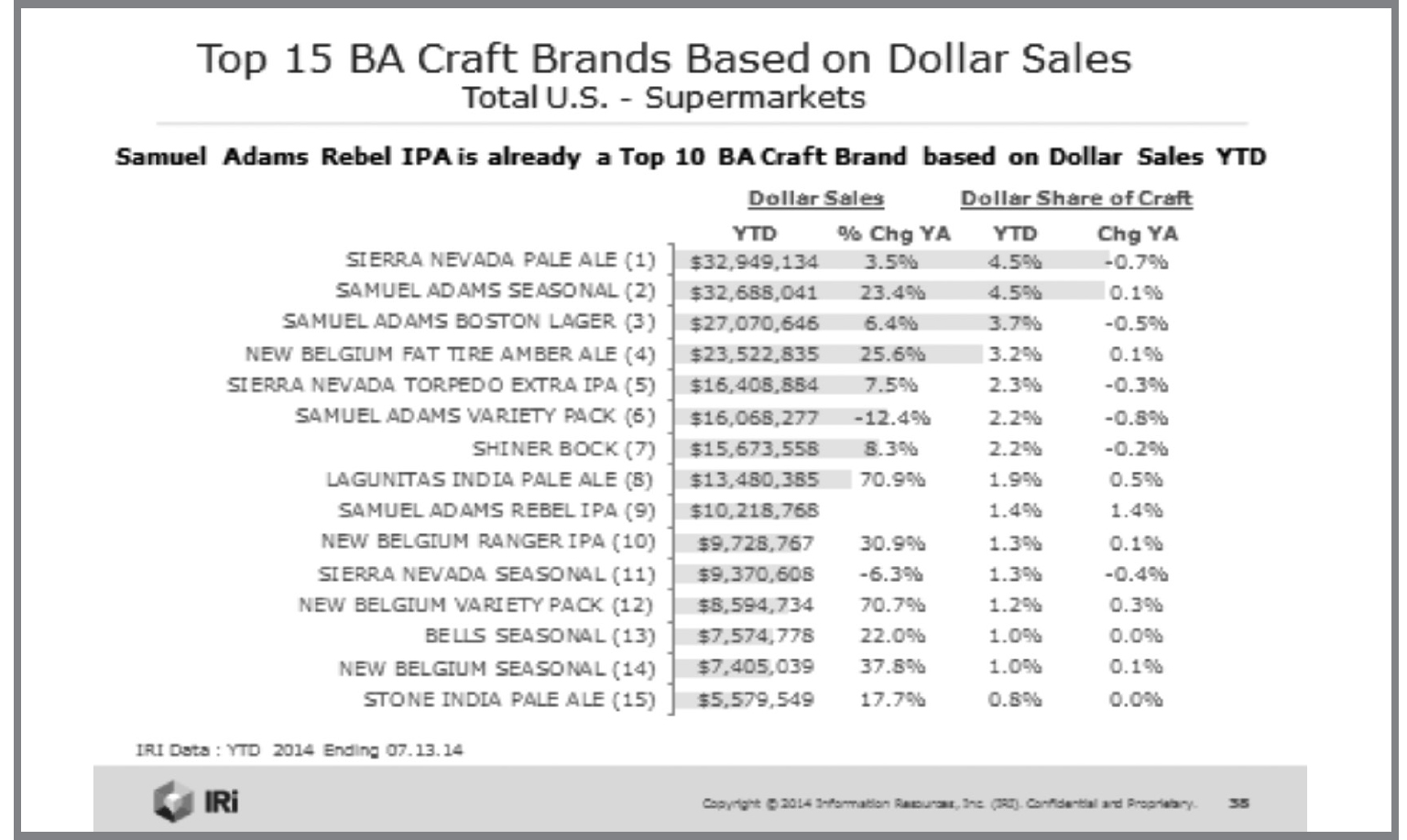

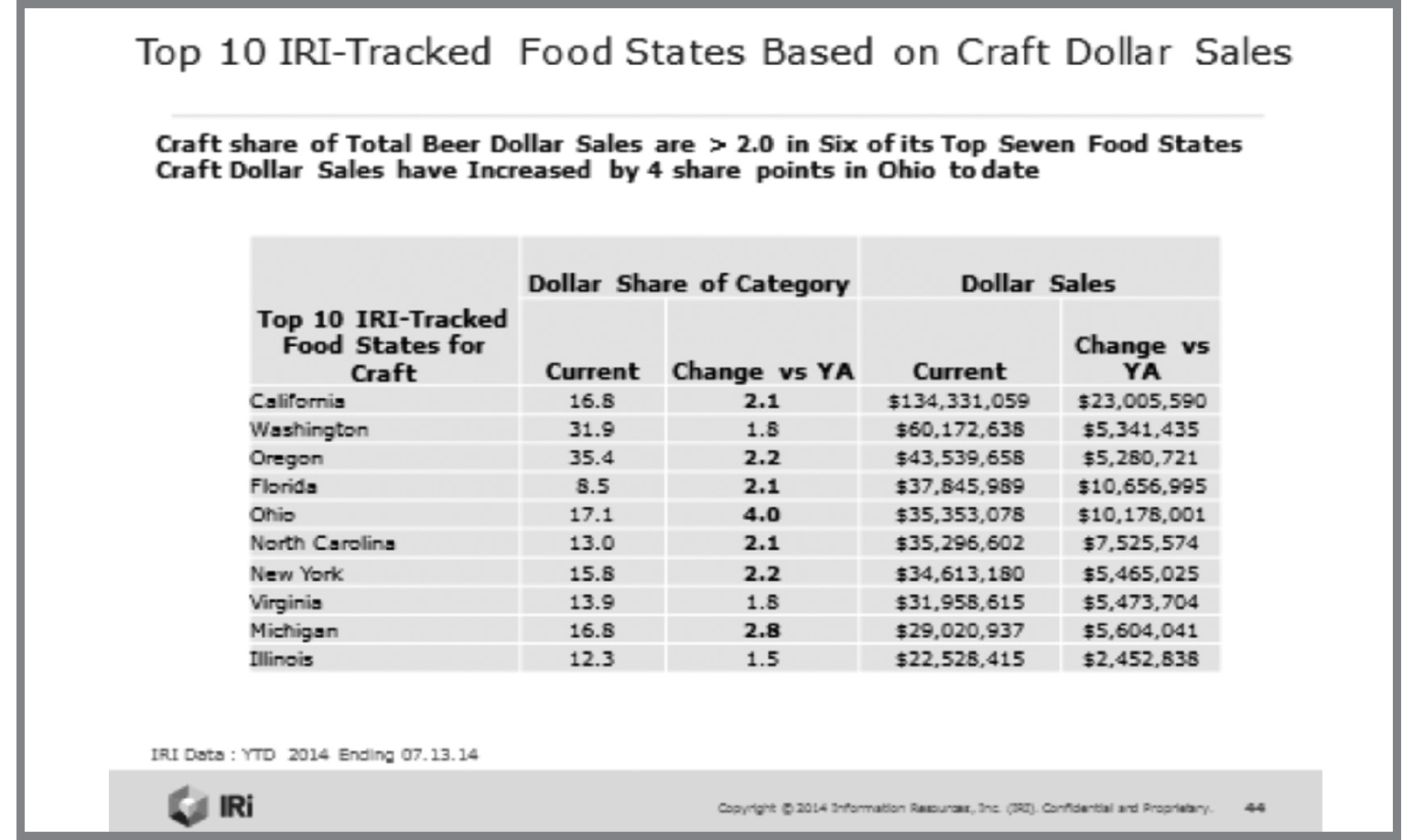

“Artisan spirits is the fastest-growing sector of our business,” Hartman says. “Up-and-coming brands don’t want to sit behind the big brands. To get a foothold in the market, they must be hand sold. You have to tell their story. They make these things, but they don’t have a marketing budget to support them. We do it for them. Now we have what everyone is looking for. We’re a major player in craft.” See Figure 8–1 for a list of other big players and Figure 8–2 for the top states in which they play, both on page 131.

New craft brands are entering a “rotation heavy market,” according to distributors. There are more brands than shelf space, so retailers constantly shuffle their offerings. The best distributors know their craft clients inside and out, and share that knowledge with the community. They work directly with restaurant chefs and bartenders to develop pairings featuring craft products. They organize tap takeovers at local bars and restaurants where host locations put a brewer’s most popular beers on tap for a night, and customers get to taste great beer and learn all about a particular brand. These events are most successful when the distributor has educated the bar staff and is at the event to answer customer questions. Pouring samples at beer and food festivals as well as music and sporting events is a constant effort.

Terry Cekola is the founder of Colorado distributor Elite Brands, a specialist in craft beer, spirits, and wine. “In Colorado, we have a great law that brewers can self-distribute. It’s fabulous; we totally support it. It’s best for them financially in the beginning. They can save a lot of money. They get reaction directly from the marketplace, the customers, about what works and what doesn’t. So when we meet with them, hopefully their beer is priced correctly.

FIGURE 8–1: List of Top 15 Craft Beer Brands by Dollar Sales

Credit: IRI PowerPoint Slide #38.

FIGURE 8–2: List of Top Ten States for Craft Beer Sales

Credit: IRI PowerPoint Slide #44.

Taking Stock with New Clients

Taking Stock with New Clients

Cekola’s team runs through a checklist with new clients to make certain they have thought through all the important distribution issues.

Do they have enough kegs? A brewery needs four or five to support one bar tap.

Do they have enough kegs? A brewery needs four or five to support one bar tap.

Do they have the right packaging for their beer style? A strong beer can be in a four-bottle pack. Lighter beers are best in six-packs.

Do they have the right packaging for their beer style? A strong beer can be in a four-bottle pack. Lighter beers are best in six-packs.

What about cans? The mobile canning companies launched four years ago that drive to breweries are now widely available, making canning affordable for small breweries.

What about cans? The mobile canning companies launched four years ago that drive to breweries are now widely available, making canning affordable for small breweries.

Do they date their beers? Craft beer is a fresh product that is rarely pasteurized. It goes stale quickly. “Freshness” dates stamped on the bottles are popular and smart selling tools. It is important to remember that the popularity of craft beer fell in the 1990s, in part, because many breweries did not have systems to remove stale beer from stores.

Do they date their beers? Craft beer is a fresh product that is rarely pasteurized. It goes stale quickly. “Freshness” dates stamped on the bottles are popular and smart selling tools. It is important to remember that the popularity of craft beer fell in the 1990s, in part, because many breweries did not have systems to remove stale beer from stores.

Are they up on the style trends? IPAs have been hot for a while, and they are not going away. Seasonal beers—small production, allocated beers—have always been incredibly popular. But the hottest trend today is session beers, lower-alcohol beers that are easy to drink. Craft brewers never call them light beers—while session beers are lower alcohol, they are not necessarily lower calorie—but they are more approachable than the higher-alcohol, complex beers craft is famous for making.

Are they up on the style trends? IPAs have been hot for a while, and they are not going away. Seasonal beers—small production, allocated beers—have always been incredibly popular. But the hottest trend today is session beers, lower-alcohol beers that are easy to drink. Craft brewers never call them light beers—while session beers are lower alcohol, they are not necessarily lower calorie—but they are more approachable than the higher-alcohol, complex beers craft is famous for making.

Do they have a local following? The rise of the local neighborhood brewery is good for craft. Certain beers are only available in their hometowns. The next town has its specialty beer. Close-to-home beer sells best.

Do they have a local following? The rise of the local neighborhood brewery is good for craft. Certain beers are only available in their hometowns. The next town has its specialty beer. Close-to-home beer sells best.

“Quality is the main thing we talk about. That’s more important than what vessel you put it in or what flavor it is. And be a good community member. What is so special about the craft industry is that it’s so collaborative. They live by the idea that a rising tide lifts all boats. People who are successful in this business are the ones who help each other.

“We talk with them about financing. You aren’t just going to pop in a new brewhouse and go to work the next day. When we get serious about bringing a new brewery in, they’ve been up and running a while,” Cekola says. They need to understand their potential for growth and how they are going to pay for it. Distributors don’t want clients to run out of beer.

![]()