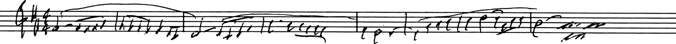

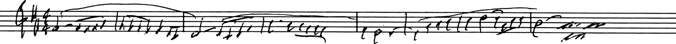

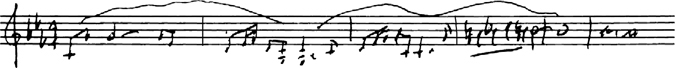

Example 3.1: Casualties of War, excerpt of the main theme

ALESSANDRO DE ROSA: When was the first time you came across a film in your lifetime?

ENNIO MORRICONE: I can’t remember precisely, but it had to have been in the thirties, when I was a kid. Back then, every theater bill included two movies, adults could watch both with just one ticket, and the entrance was free for children my age. I have a vivid and indelible memory of a sequence from a Chinese film where a kind of statue suddenly appears; it looked still, but slowly started to move. It made a lasting impression.1

Adventure films excited me, while I was not into romantic stories. When we were kids, films came out at Christmas, just like presents.

Have you ever reconciled yourself with romantic films? You ended up scoring a good deal of them over the years.

I would say so, though I always try to maintain a critical detachment when I score love scenes. I think it’s easy to become kitsch if you are not cautious enough. More often than not I don’t have to force myself, as I react automatically to the images. For instance, in the closing scene of Love Affair (dir. Glenn Gordon Caron), which I scored in 1994, the two protagonists hug and kiss after a short dialogue and a panoramic shot of New York City follows, leading in to the end credits.2 I immediately thought to use a fragment of the main theme and repeat it by gradually attenuating it. In this way, the episode of the kiss—that is, the climax, the apotheosis of the characters’ encounter—would have resulted in a unique, unrepeatable moment, and would have become a part of the characters’ memories in the very moment of its happening. The director instead wanted the music to start out lighter during the dialogue, followed by a great crescendo leading to the kiss and then to the panoramic shot—a proper happy ending, a triumph of sentimentalism that really did not convince me.

Those kinds of solutions have always left me dubious.

You don’t believe in triumphs, do you?

Not in full ones. In fact, I believe they don’t exist, other than in movies. They are quite unrealistic in everyday life. Usually, I am not so keen on composing triumphant music, I only do it when I necessity forces me to.

Something similar happened in The Untouchables (1987) by Brian De Palma, though in that case it was not a love triumph.

I remember spending four days with the director in New York, where I composed all the themes. We were about to say goodbye when Brian realized one very important theme was still missing. We went through each of them: “Al Capone’s theme is OK, the family theme too, the theme of the four friends is there . . . what is missing is ‘The Police’s Triumph’!” We decided that I would send him a few options from Rome.

I prepared three pieces, had them performed by a duo of pianists, so as to obtain some fine takes, and sent them off to him. Brian replied that none of them worked. I sent him three new pieces, but he told me on the phone that he was still not convinced, regrettably. I went back to work and sent him three other pieces, accompanied by a brief in which I specified that, of the total nine proposals he received, number six was the least convincing, the most triumphant, definitely the worst for me; so, I recommended not picking it. Guess which one he chose?

I remain silent, understanding that De Palma picked piece number six.

I bet you got it right. . . . I have the same diffidence for violent sequences (all the more when violence is unjustified) that I have for the triumphant matching of images and music in love scenes. Usually I try to compensate violence with music. At times, I interpret it from the victims’ perspective. In this respect, I think that music in cinema can extol or counterbalance the message conveyed by the images.

How important is for you to overturn clichés?

I cannot and I do not want to do it every time. However, in my opinion, it is critical for a composer to gain awareness as to the array of available options, so that he or she can make a deliberate choice and understand where to stand in regard to the images and their meanings.

Speaking about De Palma—The Untouchables was released in 1987, and that was your first film with him. . . .

It was immediately clear that it would become an important film, thanks to its remarkable qualities and stellar cast. De Palma made an excellent first impression on me, though I noticed from the start that he was a very reserved and introverted man. At any rate, his behavior concealed a sensitive and kind person.

We worked quite well together, so two years later, in 1989, he reached out again for Casualties of War, a movie set during the Vietnam War. I was struck by the symbolic figure of a Vietnamese girl who is imprisoned, abused, and murdered, riddled with bullets by a group of US soldiers on a railway bridge.

She buckles onto her legs like a dying bird, before tumbling down from the high ground. I imagined a theme based on just a few notes for two panpipes, which, by ping-ponging their sound, evoke the slowing fluttering of a bird’s wings shortly before death.

The Clemente brothers, the two pipers, amazingly rendered this idea, which was anything but ordinary for the instrument’s traditional repertory. I contrasted the panpipes with a low-range brass cluster, which I believe well renders the soft and yet stifling grip of the cold ground onto which the girl’s body collapses and dies. The main theme gradually emerges from this atmosphere [Example 3.1].3

Example 3.1: Casualties of War, excerpt of the main theme

In the final part of the piece, a choir enters repeating the word ciao [bye], which has the same meaning in Italian as in Vietnamese.

Of the three films you made together, Mission to Mars (2000) was the last and perhaps the least successful one.

Personally, my memories of it are all exceptional. I tried to follow my own path, and the music can be fully appreciated in the absolute silence of the outer space scenes, where it reaches the viewer’s ears in all its pureness.

The film was admittedly unsuccessful, both in reviews and at the box office, and I felt responsible for that. Moreover, communication with De Palma was rather nonexistent throughout the production.

He decided to meet me with his interpreter only after the recording sessions were over, shortly before my return to Rome. It was a very peculiar moment. You see, three minutes after we met, the three of us were already in tears, as Brian said, “I didn’t expect such music, perhaps I didn’t deserve it.”

In spite of his comment, it was the last film we made together, because when he contacted me afterward our schedules never matched up, unfortunately.

Why did you feel responsible for the failure of the film?

It’s simply how I feel. There’s nothing I can do about it, if a film doesn’t meet the box-office expectations, I feel responsible.

How should a piece of music enter a sequence of images?

That depends, there are no fixed rules, and yet I usually prefer a gradual progression. I enjoy when music fades into a scene from silence then fades back to silence as the scene ends. This is why, I have used the so-called pedal point a lot (perhaps even too much) over the years; and by pedal point I mean a low tenuto note, which is often assigned to double basses or cellos, or more rarely to the organ or the synthesizer.

Music enters the scene gradually, silently at the start, so that the listener doesn’t even notice. One may feel something like a presence, but it’s not enough to foresee what is going to happen. It is a neutral musical artifice, static but present, music “in essence” and yet already refined, which supports the rest of the piece and helps articulate the action.

The music may leave the scene the same way it entered, with decorum and discretion. The pedal point takes the viewers by the hand and leads them to a different place and time, before delicately bringing them back to the “here and now” narrated by the images.

How do you usually choose where to place the music in a film?

In this case too, there is not only one answer. I frequently start by watching the edited (or pre-edited) movie, which only lacks the musical track. At that point, together with the director, we take the time codes and discuss every detail. Seldom does the making of music precede the film, but in those cases I usually compose based on the screenplay or even on an exchange with the director, who tells me about his project at a very early stage: the setting, the characters, ideas, and so forth.

Which procedure do you prefer?

The latter for sure, provided that communication with the director is good. However, not every production can afford this way of working: recording the music before shooting increases costs, in that one usually needs a second session after the film has been edited, to correct imprecisions, details, sync points. . . . The whole process becomes more complex—I worked like this with Leone, Tornatore, and a few others.

How about giving me an example of a sequence you realized like this?

Probably the most famous, at least as far as Leone’s films are concerned, is the one with Claudia Cardinale arriving at the railway station in Once Upon a Time in the West.

That sequence was entirely shot following the musical timing. The character of Jill understands that nobody has come to meet her at the station, she looks at the station clock, and the music kicks in with its pedal point introducing the first part of the theme. Then Jill enters the building and asks the station manager for information, while the camera spies on her through the window from outside. Only at that moment does Edda Dell’Orso’s voice enter, followed by a rapid crescendo on the horns leading into the full orchestra, which Leone synced to an upward pan shot of the dolly moving from the window to Jill entering the village. Visually, you move from a detail shot to an establishing shot of the town, and musically from an isolated voice to the full orchestra. Except that in this case, I was not the one syncing my score to the shot list, it was Sergio who adapted his camera movements to the music. Moreover, when they shot the scene, they synced the camera movements to those of the coaches and the extras.

Leone was obsessed with the slightest details.

It has been said that this sequence caught Kubrick’s attention and that he phoned Leone to ask how he made it. . . .

Many asked Leone about that sequence, among them was also Stanley Kubrick. He asked him how the composer achieved such a seamless result with all those sync points involved. . . .

Sergio simply replied, “We had recorded the music up front. I tuned the scene, the movements, and the camera cuts to the music that was played back at full volume on set.”

“But of course, that’s clear,” said Kubrick.

Clear but not obvious, for usually music is the last thing one takes into account when making a film.

Why is that, in your opinion?

Perhaps it is a remnant of silent cinema, when pianists sometimes improvised the music live. Sure enough, however, there are also ideological and practical reasons that have since become habitual.

For instance, several illustrious composers of the past denigrated film music as functional music: according to Stravinsky, film music, just like café-concert music, had the mere task to accompany dialogues without disturbing them, while Satie spoke of a sort of “furniture music.”

All too often, no less today than in the past, music is not considered as a language that concurs to shape the content of a film, but as something that plays in the background. Starting from this bias, film composers have themselves underestimated their own contribution, and in so doing they have made directors and producers accustomed to very fast working times, not the least by resorting to myriads of clichés.

How do you typically work on films that have already been shot?

The director and I examine the film at the Moviola. I take notes and collect all the useful information, draft ideas or demands, and together we decide the entry and exit points of each cue. I time the duration of each piece and supply durations with a brief in which I outline the requirements of the transitions from one cue to the next, then I add identifying letters and time codes. When possible, I try to bargain for a few more seconds before the start and after the end of a cue, to best fit the fade-ins and fade-outs of the music, as I was saying earlier. This is the first step.

However, every time new compromises must be found, new demands must be fulfilled.

Composers must take every sound and visual element involved in the structure of the film into account, they also need to be creative and agree with their director on how to proceed.

At this point they go home, lock themselves in their studio, and work hard to figure out their own solutions.

How important do you consider the relationship with the director?

This is the most delicate and most important link in the chain. The director is the master of the work of art, which I am serving. Generally, discussions throughout the creative process stimulate me, enrich me with perspective, compel me to look for new solutions. When, on the contrary, the production phase lacks dialogue and everything is seemingly too tranquil, I feel a little “abandoned” and I can’t always be sure that I am giving my best shot.

A good conversation always helps, no matter what, because it can optimize similar viewpoints or help bridge the gap between initially distant ideas and approaches.

When did you find the atmosphere to be “too quiet”?

It’s happened several times. To name a few names, it occurred with Carlo Lizzani, Sergio Corbucci, even with Pasquale Festa Campanile, who never came to the recording room to listen to the music before editing.4

After a few films together, I told Festa Campanile that if he didn’t change that habit, I wouldn’t work with him again. He replied that, unlike scenography, cinematography, and screenwriting, music lives a separate life of its own; it is completely autonomous, and directors who think they can control any aspect of it are just daydreamers.

His comment left me perplexed, but it made me stop and think. All in all, he was implying that he trusted me and my work; what’s more, he probably had a point. Directors often feel incapable when faced with music and the composer’s decisions.

How do you remember him?

He was a very nice man, always on the phone with his girlfriend (naturally, a different one every time). I often developed solid friendships or some sort of affinity with the directors I didn’t have a lively exchange with during the production process. . . .

I had similar issues with Pedro Almodóvar, with whom I worked on Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (¡Átame!) in 1990. I could not understand whether he liked the music I wrote or he didn’t. . . .

Didn’t he attend the recording sessions?

He attended every session in Rome. The problem was that he would always tell me: “All right.” No hint of enthusiasm, warmth, or engagement. Everything was just “all right.” I even started suspecting that he was depressed, since he did not seem to enjoy anything in particular.

We met again some years later in Berlin, where we were both to accept an award. I asked him, “Tell me the truth, did you like my music for Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! or not?” He didn’t let me finish the question before exclaiming with great enthusiasm, “I loved it so much!” And then he burst into laughter. Who knows, perhaps he didn’t even remember the music. . . .

To this day, I am still in doubt as to whether he liked it or not.

His overemphatic “so much” didn’t convince me.

The main theme of Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! has a very distended character.

Yes, it was precisely this aspect of the melody that I liked. The fact is that many directors need some time to get acquainted with music they may not have expected—filmmakers live in the anticipation of a type of music they have already in mind, usually because it relates to something they have heard somewhere else, without knowing what it is. Sometimes they can get accustomed to novelty, sometimes they can’t.

Do you think the way directors couple music with moving images has changed over the years?

Yes, I think that generally speaking they have made remarkable improvements. As far as I am concerned, I always try to explain to filmmakers the way I work, the options and ideas I look for, in order to create an ever more conscious and mindful relationship. The director needs to understand why I use a certain kind of orchestration, as it may affect the features of a theme.

Sometimes I’d rather avoid writing themes altogether, but that’s quite hardly an option, as the director usually expects or the kind of film requires that I include a theme. At times, I think that my reputation for composing nice themes is precisely what got me some jobs.

Is it true that your wife, Maria, is the first person you put in charge to judge your themes?

Yes. Many a time directors had chosen the worst pieces among those I had proposed. As a consequence, I was then forced to do my best to rescue those themes, by means of instrumentation, for example. This led me to realize that I best let directors only hear the good themes. To this end, I devised a new method: first my wife would listen to all the options; then she would give me her opinion, “Keep this; throw this away; Ennio, this is nothing special.”

She does not have a technical knowledge of music, but she has the same instinct as the audience. And she is extremely severe. So this is how I solved my problem, from the moment in which Maria started giving me her feedback, directors ended up listening exclusively to the best pieces she had already preapproved.

When, on the other hand, a theme is not required, the responsibility is neither the director’s nor my wife’s, but exclusively mine.

Customarily, do you propose one or several versions of a theme to a director?

Generally I prepare different pieces so that the director can choose, I propose four or five options for a single theme. As a result I come up with approximately twenty pieces for each film; this can be disorienting for some directors. Eventually, through reasoning, we usually find the right path. We stop, we listen patiently, and gradually things start to come along with time.

The same goes even for directors I have already worked with on eight or nine films.

Usually they visit me here in my living room, I sit at the piano and they listen.

How long have you had this piano?

I point at the instrument next to the sofa where we are seated, under the tall and bright windows of the living room.

Since the early sixties, I believe. I’ve never been a real pianist, even though I passed the ninth-grade piano exam at the conservatory. However, one day I decided that I needed one of those. I called Bruno Nicolai and asked him, “Bruno, I need to buy a piano. Come with me and help me choose one.” He ended up making the choice. It is a beautiful Steinway grand piano.

Nicolai was a great friend, and I miss him.

Besides conducting many of your compositions, Bruno Nicolai also co-wrote some film scores with you.

That’s correct, but I wish to clarify the terms of our collaboration once and for all, as too many misleading rumors have been spread over the years.

First, let me say that Bruno started to work with me because he was a brilliant conductor: I knew and appreciated him since our conservatory days; for a long time, he conducted several of my film scores in the recording room, leaving me free to sit next to the director during the delicate synchronization process.

The author of an article I recently read claims that our friendship deteriorated because of those collaborations. Others wrote that we went through legal issues to ascertain the paternity of some stylistic solutions we had in common . . . some depicted Nicolai as my secret “aid,” the one who ghostwrote some of my scores. Those are all unfounded claims, journalistic inventions!

He becomes indignant.

I have always composed alone, from the primary idea to the last refining aspect of the orchestration. Moreover, never were there lawsuits between Bruno and me, simply because there was nothing to ascertain: everything was always transparent and in the light of day!

As you know, after the success of A Fistful of Dollars everybody reached me to make me score new westerns. In 1965, Alberto De Martino proposed me to score $100,000 for Ringo.5 As in those days I was working with Leone on For a Few Dollars More, I replied to De Martino’s kind request, “Thank you for thinking about me, Alberto, but why don’t you ask Bruno Nicolai? He’s a very solid composer.” Therefore, Bruno scored $100,000 for Ringo and a few other later movies by De Martino. But when De Martino made Dirty Heroes (Dalle Ardenne all’inferno, 1967), he contacted me again and pleaded with me, “Ennio, you must do this one.” I firmly replied that I would never take Nicolai’s place. He was so insistent that eventually Bruno and I mutually agreed on scoring the film together—each of us would write half of the pieces. From that moment on, we co-scored all of De Martino’s films in which one of us was hired, except for Carnal Circuit (Femmine insaziabili, 1969), which Bruno scored alone. We even decided to share credit in those cases in which one or the other authored the whole score.

After The Antichrist (L’Anticristo, 1974), another director contacted Bruno to hire the Morricone & Nicolai team. But I was opposed to creating a brand akin to “Garinei & Giovannini,” because I thought it would be inconvenient for both our careers—it meant to work in two and earn for one.

I straightforwardly clarified my position with Bruno and added that I thought it was better if we took separate paths. We both agreed on this new direction, and our friendship always remained intact and sacrosanct.

We were talking about your way of working when you write a theme. Do you prepare different orchestrations as well?

At times, yes. As I record a theme, I tend to keep the director’s expression in my sight. For the more “audacious” and experimental pieces, which I know are riskier, I usually keep a second, completely different version ready. This way, I can swiftly replace them. Giuseppe Tornatore, whom I call Peppuccio, once asked me how it was possible for me to compose new pieces so quickly. “I already have the alternative ready,” I answered him.

Did you feel your creativity was ever curbed having to compose “thematically”?

Some years ago, I went through a rather long period in which I was obsessed with the idea of “destroying the theme,” because I have always believed that relationships with directors are very limiting when based exclusively on “themes.” In 1969, I was working on He and She (L’assoluto naturale) by Bolognini, a philosophical movie based on the homonymous play by Goffredo Parise. We reached the third and last recording session and Bolognini had not yet uttered a word. That kind of reaction was unusual for him, as he generally gave me generous amounts of feedback. That time, though, he did not make any comment, he kept on drawing on a sheet of paper, without looking at me. He was sketching faces of crying women.

Suddenly I asked, “Mauro, what do you think about the music?”

Without raising his eyes from the page, he uttered these very words, “I don’t like any of it.”

“How is that possible? Why did you wait until the last session to tell me?” I replied.

“These two notes . . . they don’t convince me,” he concisely concluded.

I had written a theme based on two tones, so I told him that I would add a third one and everything would be resolved. I went to the orchestra and made all the necessary corrections. His reaction was excellent at that point. I retaped all that we had already done in the previous two and a half sessions. Eventually, it worked “fine.”

One day, ten years later, after we had made several other films together, I met Bolognini in Piazza di Spagna and he told me, “Today I listened to your soundtrack for He and She. You know, it’s the best you’ve ever made for me.”

This anecdote led me to conclude that novelty, namely, whatever is not “trendy” at a given moment in time, ends up being irksome and baffling both for the filmmaker and the audience. And yet, when all is said and done, innovation is what enables compositions to endure in time and be remembered.

This was my way of making sense of Bolognini’s sentence, as I had written other equally good music for him! In sum, hearing that was a great reward for me on the one hand, and a real blow on the other.

Have any of the directors you’ve worked with progressed in their musical competence?

Tornatore is among those who has learned the most. At times he has been able to go as far as to give me advice, which is unprecedented in my experience. I remember how his eyes lit up the first time he listened to the inversion of a major chord. In time his musical knowledge and sensibility have made giant leaps forward, and he is now very good at describing his feelings—his “ghosts” as he calls them—in musical terms. His style continues to become more and more technical; he absorbs new concepts like a sponge. On top of that, we work in great professional harmony.

Peppuccio made very remarkable films, touching upon a range of deep existential issues.

Take for instance the meanings enclosed in Malèna (2000). . . .

. . . which brought you another Oscar nomination . . .

Yes, in 2001. Aside from the nomination, I care a lot about this movie because it deals with the important and delicate question of womanhood. It is, in the end, just a film, but can you believe how many times in the past and still today women are discriminated against by our chauvinist society? Too many. All too often, especially in Italy, men are likely to ruthlessly misjudge women for a matter of convenience, in an attempt to subdue them and put them in an inferior position compared to men. This is really unbearable for me.

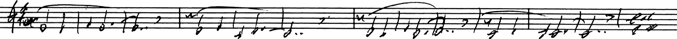

I employed some geometrical and mathematic procedures to build up musical passages and arpeggios in the film, so as to suggest the automatism of idiotic social clichés. The main theme, on the other hand, departs from everything else and escapes to a different place. Perhaps it flies toward utopia, or at least toward the way I wish things were [Example 3.2].

Example 3.2: Malèna, excerpt of the main theme

Your first film together was Cinema Paradiso (Nuovo Cinema Paradiso, 1988). How did you first meet Tornatore?

Franco Cristaldi phoned me and told me he wanted me to score a movie he was producing.6 I was very busy, and I was about to start working on Old Gringo (1989) by Luis Puenzo, starring Jane Fonda, Gregory Peck, and Jimmy Smits. So I told him that I couldn’t. He insisted so relentlessly that I was nearly exasperated when I hung up the phone. Shortly after, he called back to say that he was going to send me the script anyway: “Read it and then decide!”

I read it because Cristaldi was a dear friend, and we had always worked well together over the years. When I got to the final scene, the famous reel of kisses, I was convinced. I turned down Old Gringo and devoted myself to Cinema Paradiso.

That’s life: at times there are unexpected encounters and one has to muster up the courage to seize the opportunity. The kisses scene struck me so, already while reading the script. When I then saw how Tornatore realized it in the film, he confirmed my first impressions of his narrative and directing talent. The idea of recounting the history of cinema by editing together all of the kiss sequences that had been censored by a provincial priest was just fantastic. I never understood why he had Cristaldi make the phone call and didn’t do it himself—perhaps Peppuccio was too shy.

To begin, I prepared the theme of the cinema, indeed called “Cinema Paradiso” [Example 3.3].7

Example 3.3: Cinema Paradiso, excerpt of the homonymous theme

On the other hand, you co-wrote the love theme—the one occurring both in the kisses sequence and in the sequence when the lead character returns to his childhood bedroom after many years—with your son Andrea. How come?

I took a theme he had composed and made some irrelevant adjustments—as his original idea was brilliant. We scored the whole film together.

For the following two Tornatore movies we shared the credit again, even though I composed everything on my own this time around. We did that as a good omen—because the first movie had done so well, we hoped for the success of the next ones.

Meanwhile, Andrea has become a talented composer; in addition he studied orchestral conducting. . . . Despite my concerns about him starting a career in music (because it is always such a tough and uncertain choice), I can say today that I am glad he insisted. Indeed, one could already recognize his talent in that theme.

So far you and Tornatore have made eleven films together in total. . . .

I’d rather say ten and a half, because Il cane blu [The Blue Dog]—besides containing a lot of music, almost like a silent film—is an episode in a multi-authored film, Especially on Sunday (La domenica specialmente, dir. Francesco Barilli, Giuseppe Bertolucci, Marco Tullio Giordana, and Giuseppe Tornatore, 1991).

In 2013, Peppuccio phoned me and asked, “Did you know that today is our silver wedding anniversary?” It was unbelievable that twenty-five years had flown by so fast!

A great friendship has flourished between us, and when relationships of this kind develop, I feel stimulated not only on a personal level but also on a professional one. He is a competent author, attentive to details, broadly versatile. In other words, his movies never fail to thrill me. Therefore, while on the one hand I am engaged by the technique, personality, and content of his cinema, on the other, he is always sure to provide me with the best working conditions, allowing me all the time and room to tailor a musical idea to the images and sounds of the film, to carefully ponder the mixing phase, to decide which emotions to amplify and how to do so, all of which is crucial for me. . . . Peppuccio and I work in great synergy. It is so rare to build such a working relationship.

Was it demanding to work on The Legend of 1900 (La leggenda del pianista sull’oceano, 1998)?

It was a colossal movie, one can tell this just by listening to some of the orchestrations I made for the main themes.

I composed a great deal of music for this film, spanning different genres, combining full-orchestra effects with jazz sonorities and inflections. Still, I must confess that perhaps my favorite version of the main theme is the simplest, the one for solo piano, which can be heard in the track “Playing Love,”8 when the character named 1900 [Tim Roth] gazes at the face of the girl [Mélanie Thierry] through the ship’s porthole as he is recording on a rudimentary gramophone [Example 3.4].

Example 3.4: The Legend of 1900, excerpt of the main theme

The biggest trouble I had since first reading the script was the requirement to write “music which has never been heard before”—these are Peppuccio’s exact words in the script, but also the words used by Alessandro Baricco in the book from which the film was adapted—to describe the music played by 1900.9 A beautiful phrase, for sure . . . but what if you are the one who is supposed to comply with that expectation?

Even from a technological profile I discovered aspects that would have been unthinkable just a few years before. Do you recall the scene of the piano contest between 1900 and Jelly Roll Morton, the legendary black pianist?

Sure.

Well, all of Jelly Roll Morton’s recordings were quite outdated, the quality of the disks was very poor, and hence it was impossible to use them directly in the film. Naturally there was the option to newly record them, but at the price of losing Morton’s unmistakable touch. My sound engineer, Fabio Venturi, came to our aid.

Together we collected the tracks we were interested in and managed to extrapolate the dynamics of every single note, thanks to digital and MIDI procedures.

And what about the piece 1900 eventually wins the contest with, inflaming the audience and literally setting the piano strings on fire?

It’s a virtuoso piece played beautifully by the extraordinary pianist Gilda Buttà.10 We overdubbed some parts, since it had to convey the impression of more than one pianist playing at once. Peppuccio’s editing was also very convincing.

If you were forced to save just one score among those you wrote for Tornatore, throwing everything else away, which would you choose?

That’s a very difficult question. I would not throw anything away, as I love everything I made. But if I had to choose, I think that I devised the best intertwining between music and film in The Legend of 1900, The Unknown Woman (La sconosciuta, 2006), and The Best Offer (La migliore offerta, 2013)—perhaps even more so in A Pure Formality (Una pura formalità, 1994), a very special film for me.

Roman Polanski starred in the role of a detective psychoanalyst . . .

I worked with him twice. The first time it was in a film he directed, Frantic (1988), with Harrison Ford and Emmanuelle Seigner (who later became his wife), the second time in A Pure Formality, in which he costarred with Gérard Depardieu. One time I saw him acting in a stage drama, Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, and I was absolutely stunned: he is a great director and a superb actor—a smart, correct, amenable, and generous man.

How did it go with Frantic?

I can’t recall the way he contacted me, but when we met he decided to show me the film right away. Ideas flowed immediately after that first meeting. It was a crime thriller.

I used a predetermined harmonic scheme, which I then worked out in numerous ways. It was combinatory music, just like “Inventions for John,” yet more complex. Something similar can be found in the combinations of themes I realized in The Mission for the “Requiem glorioso” [Glorious Requiem], the piece that later took the title “On Earth as It Is in Heaven,”11 the difference being that such a procedure is much less apparent in Frantic, and only a trained ear can notice it.12

How do you recall working with Depardieu? You scored a number of films in which he starred, and in A Pure Formality he sang your song “Ricordare.” . . .

Initially Claudio Baglioni was expected to sing that song.13 We rehearsed it once in my studio and he was magnificent, but eventually nothing came of it. At that point, Peppuccio himself wrote the lyrics and we considered having Depardieu sing it.

I remember the moment we were in the recording studio: I gave him the cues and, all in all, he worked them out quite well.

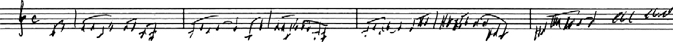

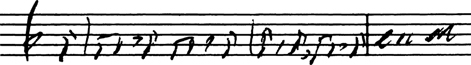

For that song, I had imagined the word ricordare [remember] woven into the melody, right from the start: “Ricordare, ricordare . . .” [Example 3.5].

Example 3.5: Vocal line of “Ricordare” (A Pure Formality)

What is your attitude toward songs in film?

It depends. I wrote some songs in agreement with directors, but the choice of the singer was always up to the production—I have never personally chosen one. Unfortunately, the presence of a song in a film nowadays is all too often determined not by the wish of the director or the composer, but rather by the producers, who chase easy fame.

I turned down some productions where requests came up at the last minute to insert a song that was well ranked on the charts.

On various occasions. I turned down Zeffirelli’s Endless Love for this very reason. As I was about to tell you earlier, I traveled to Los Angeles, where I had already composed several themes, including the piece that would eventually become “Deborah’s Theme” in Once Upon a Time in America.

Obviously I had signed a contract for the production; then one day in a meeting Zeffirelli mentioned that we ought to insert a song by Lionel Richie, sung by Diana Ross.14

I found it absurd that a song composed by someone other than myself would be inserted into my score.

Zeffirelli explained that later agreements were undersigned with the producers after my contract had already been signed and that he had to comply with Richie at that point. He asked me to turn a blind eye.

I replied: “Franco, that’s not written in the contract I signed. I’m not going to make the film.”

He insisted, but I turned him down anyway. The producers paid me a congruous amount for the work I had done thus far. After nine days spent in Los Angeles, I left with my earnings in hand.

Nine years later I would collaborate again with Zeffirelli, on Hamlet (1990), starring Mel Gibson.

Then the moment arrived when Leone listened to that particular theme and wanted it for his film. Sergio fell in love with it right away, and once he heard the story about its origin he burst out in sarcastic comments. He was always eager to know every single detail, and he knew how to be ruthless toward his colleagues.

Do you consider song a lesser genre?

No, I myself have composed a lot of songs and have nothing against them or against singers. However, the moment in which a composer is hired to write the score for a film, he or she gets to developing an integrated whole. To introduce a heterogeneous musical identity at the last minute is not something that one can do haphazardly . . . it must be pondered with careful attention.

Another bizarre episode more recently occurred with Quentin Tarantino on Django Unchained (2012).

Are you referring to “Ancora qui” [Still Here], the song performed by Elisa?15

Exactly. Our common publisher (Sugar, Caterina Caselli’s company)16 commissioned me to write a song. I accepted, wrote the music, and sent it to Elisa. A demo version, combining Elisa’s voice and a rough mix of my arrangement, was then delivered to Tarantino.

He liked it so much that he put it directly in the film, without waiting for the final mix, which eventually was released only in Elisa’s official album.17

Tarantino is famous for his very peculiar way of dealing with music, but that time he went so far as to use a provisional version!

That demo is now in the film, and I still haven’t figured out why. Perhaps he deliberately wanted it, or maybe he thought that it was the definitive version. . . .

It’s a totally different case when a song is foreseen in the screenplay, right from the outset—identifying a specific meaning in a film, its story, and thus its musical articulation.

For instance, my collaboration with Joan Baez on Sacco & Vanzetti was conceived of up front for explicit reasons, and, above all, the storyline justified the song’s presence. The same can be said for A Pure Formality, where the song “Ricordare” plays a specific symbolic and functional role.

What is your attitude toward music that is inscribed at a film’s internal level, that is, that comes from within the scene?18

I have always been interested in distinguishing between musical underscoring and source music, that is, between the music stemming, say, from a record player, a ballroom, or a car stereo.

The times in which I was asked to write for the internal, diegetic level, I sometimes even worked the tracks in such a way that they would sound rawer, for they are usually of secondary importance, and I tend to make sure they don’t blend with the external, accompanying score.

I feel like it is important to emphasize the difference between music which directly expresses my ideas about the film and its characters, and applies to an external, extradiegetic level, and music that is extemporarily connected to an internal sound source.

At times, however, the music coming from a radio or from the story is of fundamental importance to the storyline.

To what extent do you think music can be adapted to predetermined images?

Everything depends on what one aims to express. After so many years working in this industry, I have come to realize that music has a singular flexibility in regard to movies, stories, and images. One can test such adaptability particularly in films featuring few themes. There it is easier to notice the extent to which the same music can achieve different goals when it is synced to different images.

For Investigation of a Citizen above Suspicion, I composed only two themes, both of which recur throughout a number of scenes. This is a good example of what I mean—Petri was very ingenious and was able to obtain several variants of meaning, thanks to his edits.

Do you think that there is such a thing as “perfect” music for a given sequence of pictures?

I have ever fewer certainties as I go on, and I would probably say that the right music does not exist, and yet every piece of music has its own character and its own evocative potential. Applying music to film connotes poetical, and consequently mysteriously empirical reasons. The blend between music and images is always determined by something that is not completely controllable by those in charge. This procedure can be accomplished in different manners and with different goals. And these very variables lead to the mystery I am referring to.

The same sequence can be musically interpreted in manifold ways, some of which work better than others, but after a certain point we enter into the land of subjectivity. To give just one example, I love Nino Rota’s work with Fellini, especially in films like Fellini’s Casanova (1976). And yet, in his place, I would have written completely different music, arguably not less “right” than his. The same is true for him, had he scored the movies I did.

It appears that you have reached a very flexible vision as to how the relation between music and images should be. . . .

Some years ago, when I was in the jury of a music symposium in Spoleto, I launched an experiment: ten composers were asked to score the same film sequence. Afterward, each one of them was given the chance to personally discuss the scene with the director. As a result, each proposal turned out very different from the others, though all of them were excellent in themselves.

Now, which one was the most appropriate? Which one worked best?

We noticed that the visuals acquired different meanings thanks to each score, and this affected the viewers’ perception. This aside, we were not able to single out the “rightest” piece of music: there were too many variables at stake.

Oftentimes, for example, Tarantino has benefited from this kind of openness when he utilized music that I had composed for older films and fit it into new scenes.

What was your opinion of him and his cinema before you first collaborated?

I had and have always considered him a great director. Tarantino “eats up” cinema each time he makes a new film.

I like some of his films better than others. Django Unchained, for instance, is not my favorite: his approach to the history of black slavery in America is original, as he always manages to be; however, when he makes blood gush so much, it’s not my cup of tea. Django Unchained “terrorizes” me.

Besides the original song “Ancora qui,” which I co-wrote with Elisa, he also used “The Braying Mule” and “Sister Sara’s Theme,” two pieces from an American production I worked on with Don Siegel in 1970—Two Mules for Sister Sara, starring Shirley MacLaine and Clint Eastwood—as well as some pieces by Luis Bacalov.19

His previous film, Inglourious Basterds (2009), was realized very well, for my taste. The same amount of violence is present, that is after all a cypher of his work, but it is employed differently. The dialogue is extraordinary and the acting is fantastic. Inglourious Basterds is an outstanding film.

It too features a lot of your music. What runs through your mind when you find out that a piece you composed for a different occasion is used in one of his films?

It feels strange. Tarantino often appropriated my music to dislocate it in a completely different context from the one it was meant for. Part of my reluctance to work with him derived from the fact that I was somewhat afraid to come up with new music for him, as I feared that he might be too conditioned by his own musical habits. . . .

Before The Hateful Eight, Tarantino had always compiled preexisting music. How could I write something that would sound new for him and yet keep up with his idea of my music, which he knows so well and considers perfect? “Keep this perfection for yourself,” I would say. “I’m not going to work with you.”

Moreover, I was concerned with the eclecticism of his musical choices, as he always juxtaposes such a diverse array of pieces, following very subjective associations. On the other hand, there was so much of my music already among the tracks he had used in his films, that I might have been expected to compose something akin to the stuff I had already done. Frankly, that idea didn’t particularly thrill me, as I worried that, due to that sort of expectation, the outcome would never please him as much as the model he had in mind. . . .

At any rate, I believe that he has frequently made remarkable musical choices. For instance, the building tension in the first sequence of Inglourious Basterds draws on a part of a cue I used in the television series Secret of the Sahara (Il segreto del Sahara, dir. Alberto Negrin, 1988), entitled “The Mountain.”20

Right, that’s the kind of silent but increasingly uncanny tension so typical of masters of suspense, that we referred to earlier when comparing it to the tension that builds up during a chess game. . . .

Exactly. The Nazi official [Christoph Waltz] talks quietly with the farmer, the same way you and I are talking just now. But in a matter of a few minutes he turns into an incredible son of a bitch!

Naturally, when I originally composed that music in the sixties, I was not thinking about a Nazi official who ruthlessly kills a group of poor women hiding beneath the wooden floor. But it works fine anyway.21

Among the main pieces used in Inglourious Basterds there is also “Rabbia e tarantella” [Rage and Tarantella] from the film Allonsanfan (1974) by the Taviani brothers.22 In that film the piece was originally the theme of the Italian revolutionaries when dancing a tarantella, but Quentin associated it with the armed group of headhunters.

He then used “The Verdict,” from Sollima’s western The Big Gundown (La resa dei conti, 1966). In a scene of that film I even quoted the melody of “Für Elise” by Beethoven.23 He took the piece “Un amico” [A Friend] from another movie by Sollima, Blood in the Streets (Revolver, 1973), and used it to underscore the double murder of the woman [Mélanie Laurent] and the German sniper [Daniel Brühl] in the projection room of the movie theater where the Nazi movie is being screened.24

Then again, the film features “L’incontro con la figlia” [Meeting with the Daughter], “The Mercenary (Reprise),” “Algiers: November 1, 1954” (co-written with Gillo Pontecorvo), and “Mystic and Severe.”25 He is definitely a director who uses music in a very singular way.

So, what was it like? You went to the movie theater, took your seat, Tarantino’s new film began, and . . . ?

I enjoyed it. At that point, I didn’t care about the music anymore. “If he’s happy with it . . . ,” I would think.

I mentioned “The Verdict,” the track in which I quote “Für Elise.” I had already started a piece with the same quotation in Sollima’s first film.26 The quotation didn’t have anything to do with the film, but the movie sold so well that Sollima started to consider it a lucky charm, so from then on he wanted to open every new film with that quote. I did so for his two following movies.

When Tarantino utilized it, there was no reason in trying to justify the presence of that quotation . . . why? What could I object to at that point? If you like it so much, keep it. . . .

When a piece is decontextualized, it loses its meaning for you.

Yes. But I must say that his cinema has many merits. Sometimes I spoke against his way of proceeding, and the press misinterpreted it. Some wrote that Morricone didn’t like Tarantino’s films enough to say “yes” to him. But if I decided to collaborate with him, it was certainly not out of caprice, it is because I have always admired him. Moreover, so many people, such a wide and diversified audience, watch his films, and it appears that young people especially get in touch with my music primarily through his cinema.

Right, but what made you change your mind and accept to score The Hateful Eight?

As you know, we had already been in touch for the making of Inglourious Basterds, but at the time I was already working with Tornatore, and Quentin had a very tight deadline because he wanted to be able to premiere his film in Cannes. I could not make it in that moment, but I never precluded myself from collaborating with him on another occasion. Sure enough, all the things I was saying, my admiration for him, my wish to cross generational boundaries, the fact that the screenplay he proposed was really well written . . . a new challenge like this at my age—all these aspects eventually convinced me.

Tarantino insisted on a lot, he even came to Rome on the day before the ceremony of the David di Donatello Award in 2015 and brought me a translation of the script in Italian.27 He made me realize that, besides following my work for such a long time and knowing it so thoroughly, he really wanted me the way I am now.

Surely, the advice of people around me also played a role. When the chance to work with him started to be concrete, many friends I esteem such as Peppuccio, Fabio Venturi, yourself, Maria, my children, and even my grandchildren told me, “Why do you always say no to him?” And I answered, “Perhaps this time I’ll say yes, but if it’s a western I’m not going to do it!”

And yet . . .

And yet, nothing. I don’t consider this to be a western. Rather, I see it as a historical adventure film, in a sense. The characters are described with such meticulousness and universality that the fact they wear cowboy hats is nothing more than an alternative setting.

In fact, when I first listened to the music before seeing the film, I immediately thought it had something to do with a macabre ritual, as though the theme was black magic. Furthermore, two bassoons in unison convey a visceral quality and a brutal undertone. . . .

The main theme starts with two bassoons in unison, and I reprise it later in the film with a contrabassoon dubbed by the tuba. As you just said, I needed to express a visceral, hidden, or buried core, something latent and yet bodily present [Example 3.6].

Example 3.6: The Hateful Eight, excerpt of the two bassoons’ line in the main theme

Quentin was very satisfied with the outcome, he even came to Prague to attend the recording sessions, and then they mixed the whole thing in the United States. That worried me a little, but they did an excellent job.

I told Tarantino that if he wants to make another film with me, I’m fine with it, provided that he gives me more time. . . . I hate to work in haste.

Besides Tarantino, your music convinced several international juries as well. Among the many awards, it earned you your third Golden Globe and, finally, an Academy Award for Best Original Score.

Yes, it was a very happy moment. I received a wealth of congratulations and international acknowledgments by illustrious colleagues.

It took me a long time to decide whether or not to go to the United States—you know, such a long trip at my age . . . it actually caused some health issues. . . . Most importantly, I had to make my decision without knowing if I would win.

The Oscars are like a lottery . . . you go there, you sit and wait, you may even be the favorite, but if your name is not the one to be called, you can be sure you’ll have a hard time afterward. It happened five times to me already, as you know. “Do I go? Do I stay?” Eventually I told myself that I should go and so I did.

And you were right to do so!

I smile.

Yes, this time.

He smiles too.

Besides, the Academy Award was not the only ceremony in those days. I was honored with a star in the Walk of Fame on Hollywood Boulevard.

I confess that it was as tiring as touching. Tarantino came too, with producer Weinstein.

I was enormously pleased, also because I know how beneficial these kinds of accomplishments can be for Italian cinema as a whole.

I was at the Academy, sitting in the audience, and I was struck upon observing that your modesty completely set you apart from the general tone of the event. These kinds of get-togethers are usually very pompous, important of course, but also very glamorous, so to speak. In your address you spoke instead about a composer’s troubles to write for a wide audience, how this issue brings a deeper dimension related to the difficulty, but also the opportunity, to discover a way to match the public consensus with your own inner demands and needs. Despite what the market appears to suggest most of the time, consensus and quality don’t have to be totally disconnected.

I was terribly sorry for not being able to speak English, but as you know I never learned the language. At any rate, I think that you perfectly grasped the tone of my speech. It is fundamental for me to remind myself and others not only about the struggles I go through in complying with the several inner needs embedded in my stratified experience as a composer (not exclusively for films) who has lived with curiosity throughout the twentieth century; but also of how complicated it is to pursue a thin, mutable balance of communication between the composer and the listeners.

I am always chasing that particular point of convergence, even when I aim to contradict it, to do without it, but still holding it in the highest consideration.

Always “chasing that sound,” so to speak?

Sure, always looking for the right sound . . . or maybe for a group of sounds, their reciprocal relations, and beyond . . . but this is an extremely mysterious matter. . . .

He stares into the void and stays silent for some moments.

You know, Ennio, when Tarantino received your Golden Globe on your behalf, he declared that you are his favorite composer. He put you even before Mozart, Schubert, and Beethoven. . . .

I took that as a joke, spoken with honesty, but still a friendly sort of sacrilege. Luckily, I don’t have to judge myself; history will put all these day-to-day events in perspective.

The right time for assessment will come in some centuries. What will remain and what will not? Who knows!

Music is mysterious; it doesn’t offer many answers. Film music, on the other hand, is even more mysterious at times, both because of its bond with images and because of its way of bonding with the audience.

I would like to go back to the relationship between music and images and ask you something slightly more technical and personal. Given the variety of ways in which music can be employed in a film sequence, and the infinity of its possible associations with the image, what is your stance as a composer of film music?

I acknowledge that music is very malleable. On the other hand, in trying to stay musically coherent to myself, I have always sought for new ways to interweave music and the other elements of a film, principally the visual ones, and respond to the demands I’ve perceived in them. It is a way of working that embraces ambiguity, as you can see. However, absolute relativism does not lead anywhere, and perhaps I would have never succeeded in this profession had I disregarded cinema’s most empiric, aleatory, random, and extemporary facets.

The only certainty I have is that music must be finely written, even when it is intended for a different art, another expressive form. It must be based on internal, formal, and structural parameters, solid enough to hold its own independently from the images. At the same time, musical ideas must be attuned to the elements and suggestions of the specific cinematic context.

This job presupposes a thorough analysis of the script and the film—one must dig into the scenes, the characters, the plot, the editing, the technical realization, the light treatment and its typology. Story and space—everything is important for the composer.

Only after I’ve read the shooting script or the screenplay do I begin to work out some ideas. Characters, with their interiority and psychology, are especially important for me. Even when they are one-dimensional—intentionally or not—I try to imagine their thoughts, their unspoken intentions; in other words, I try to comprehend them in depth to be able to present them in a more personal, intimate light. One should not superficially stick to the image, but transform it into a resource.

I have always seen this as a personal challenge: to ensure that the music can stand autonomously, that it conveys my mindset, and that it at the same time enhances the director’s visual ideas.

I don’t know if I have managed to achieve this every time, but I have always worked with this principle in mind.

What about the viewers? Why do they usually trust the music in a film, in your opinion? Consciously or not, it is as though paradoxically they give more credit to the music, rather than the image.

These are difficult questions. Firstly, I believe that one goes to the movie theater to watch a film, not to listen to it. At least this can be said to be the general attitude among filmgoers. Music thus situates itself in a rather concealed position; in this sense, the viewer internalizes it almost deceivingly. Music succeeds in orienting, inspiring, and letting people get carried away for that very reason. Most of the time, people experience the music in a film as a subconscious suggestion. This is even truer when considering how broad the audience to which cinema appeals is—oftentimes a multitude of musically uneducated people.

In other words, music manages to show what is not visible, to work against the dialogue or, even more, tell a story that the images do not reveal. In this respect, the film composer has a great responsibility, a moral duty, which I have always felt deep inside me.

Indeed, the majority of viewers accept and trust the music without being aware of the variety of interpretive layers of a film, or being cognizant of the historical development of music in the twentieth century, and so forth. Hence, how can a composer be simultaneously true to him- or herself, respectful of the director’s intentions and producer’s ambitions, and also communicate with the audience? The answer is different every time.

What ties music to images, in your opinion?

Film and music are paired first and foremost—before their meaning, before their will to mean anything—by a particular employment of time. In fact, it is over the course of a given time span that a piece of music builds up and then reaches a conclusion, on a sequence of tones and silences; likewise the frames that make up a film sequence evolve over time.

In this sense I speak of temporality, that is, a controlled distribution of information within a specific time unit, which is shared on both the sender’s and the receiver’s ends.

What is music’s main function in relation to the moving pictures?

My friend Gillo Pontecorvo used to say that behind every story cinema tells there is a real story, one that really counts. Well, music must find a way to bring out the value of that hidden story and highlight it.

Music should help clarify the meaning of a film, whether it is of a conceptual or sentimental nature. Whatever the case, music makes no difference between the two. Rather, music “helps sentiments be conceptualized and concepts be sentimentalized,” as Pasolini used to say. Therefore, its way of working is always ambivalent.

This ambivalence is justified by the fact that, while music aims to emotionally involve the viewer, it cannot deny or neglect its descriptive and interpretive goal. This being said, I guess that all of that is and will remain a mystery.

How does the association of music to the visuals work from a technical point of view?

Technically, the application of music—even preexisting music—to images obeys dual parameters of immobility or movement, stasis or rhythm, depth, consequentiality, verticality, and horizontality.

What I call the “horizontal application” of music to moving pictures occurs along the unrolling of images; music adds rhythmic values to visual perception, reaching the brain through the ears. “Vertical application” instead concerns the perceived depth of the image; now, given that the cinematic image is essentially flat—in spite of its illusionary potential—the vertical dimension is much more important than the horizontal, as it carries somewhat of a spiritual, rather than physical, component. I think it is fair to say that vertical application better serves to highlight the conceptual content of a film.

I believe that the application of music to the moving image marks a decisive moment in the life of a film. Music replaces the image’s illusory depth by providing, or rather, newly creating a poetic depth. To this end, music is even more effective when it has a life of its own and its specific musical qualities hold up to critical scrutiny. However, music can only fulfill this role if the director allows it the necessary room to manifest itself naturally. It is essential that music be given the right space to release itself from the other sounds in the film. Here we are entering a technical ground, typical of the mixing process.

A poor mix can ruin a film, as much as the lack of proper space for music’s deployment. On the other hand, an overabundance of music can just as equally damage the ultimate outcome of the film, the comprehensibility and the effectiveness of its communication. Music is all too often either excessively low in volume, too sparse, or too continuous. The timing and modes of music’s entrances and exits in a visual sequence should be cautiously considered, as well as how it is balanced within the overall soundtrack—including effects, noises, and dialogue. Too frequently this doesn’t happen.

I’ve been asked many times why the music I’ve composed for Leone has been my best. I don’t agree with this judgment, in fact I believe I’ve written better scores. But it is true that, compared to other directors, Sergio left more space for my music to express and reach its full potential; he valued music as the supporting architectonic structure of certain passages in his films.

One should also bear in mind that the eye has more possibilities than the ear to consciously draw together different elements and “understand” them.

In what sense? Does this last point relate to a specific kind of audience?

In my experience I have come to believe that it is mainly a physiological matter. Eyesight, most likely, has a sort of sensorial priority over hearing, and yet, immediacy does not equal comprehensibility.

The eye can decode complex elements and synthesize them into a single unity, conjuring up general meanings through contrasts and relating the various fragments it observes.

The ear instead cannot distinguish the identities of more than three sounds at a time; it can only add them together as though they were one. For instance, if five people speak simultaneously in a room, it is virtually impossible to understand what they say, the result being a buzzing sound. Interestingly, a person with decent ear training can singularly grasp each voice in a three-part fugue but cannot distinguish the horizontal lines (the melodies) in a six-voice fugue; the only aspect one can perceive in that case is the fugue’s vertical totality (the harmony).

All these features must be considered during the mixing phase, precisely to avoid confusion in the viewer. In order to achieve a clear communication, it is in fact opportune to monitor the mixing of the music with the other sounds.

With directors, and not only with them, I often talk about a principle concerning the soundtrack (meaning the totality of music, its sound effects, dialogue, and noises) and its perception in relation to the images. I call it “EST,” that is “Energy, Space, and Time.”

These are three very important parameters for the functioning of a message that a director and composer deliver to the audience. I find that music is more and more relegated to a background function in today’s world, and it necessitates these three elements in order to release itself and reach its destination.

I can still recall the sense of amazement in the people who attended this incredible installation we did some years ago, one evening in Piazza del Popolo. Loudspeakers were scattered all over the place and transmitted a piece I had composed for Mission to Mars by De Palma.

Even though I am used to listening to my music in the most disparate contexts, I could appreciate the technical perfection of that installation: the volume was overwhelming, the body vibrated, and the sounds floated through the air. Silences were wounds. That experience confirmed what I already believed about the concept of “sonic energy,” that is, when music reaches its proper volume, one can no longer pretend it does not exist and cannot help but inhabit it; even the most distracted people stop minding their own business and start listening.

In other words, for you film music exerts a power over the listener that goes well beyond its relationship with images.

The most important thing, which perhaps I’ve never said out loud in my previous reflections on film music, is I believe that music is independent of cinema. Even more radically, I dare to say, that true cinema can do without music precisely because music is the only abstract art that does not belong to the reality of film.

Sure enough, a film can display a radio device or a band playing a melody and characters dancing to it, but that is not the real music in the film. The real music cannot be seen and is tasked with expressing what the images are otherwise unable to say. For that to happen, during the mixing phase one ought to avoid overlapping music with other noises, other musical elements, or too much dialogue.

The general appreciation of my music in Leone’s and Tornatore’s cinema goes beyond music per se: the truth is that Leone and Tornatore mixed it better than others. How? They left it alone, washed it away from other sounds; the listener can therefore focus on the music and better enjoy it.

Leone, Claude Lelouch, Elio Petri, Bernardo Bertolucci, Gillo Pontecorvo, Tornatore, and other skilled directors do isolate sounds, be they noises or music, because they always demand the highest effectiveness and signifying potential.

Not only is the argument that cinema is more image than sound beside the point: it is false. Yes, film started as projected images, and the lineage of that origin still persists today. But cinema is an art form that includes both hearing and viewing, and the richness of its meanings can only be extolled in the democratic equality of these two senses: experiencing the projection of a film in the recording room, devoid of any sound or just with the dialogue, would do justice to my point. However, this does not change what I have said earlier, that is, that a film can in theory do without a musical score.

How important are the sound technicians working on your side?

They are fundamental in film music, because what the audience experiences in the movie theater is not a concert but a digital rendering obtained by means of recording, mixing, and mastering.

In the sixties and seventies, I used to let the director mix everything alone, then I realized that it was better to be present, to be in control, and prevent mistakes.

I worked with extraordinary sound technicians throughout the years: Sergio Marcotulli, Giorgio Agazzi, Pino Mastroianni, Federico Savina (Carlo’s brother), Giulio Spelta, Ubaldo Consoli; lately and for a considerable time stretch, I have been working with Fabio Venturi.

In 1969, Bacalov, Trovajoli, Piccioni, and I even bought a recording studio in Rome, where we could carry out our activities as film music composers. Those were very intense years.

Is it the current Forum Music Village?

Back then it was called the Orthophonic Studio. It was Enrico De Melis’s idea, who was also my agent for a while—a very honest person.

We owned the studio for ten years; we then decided to sell it in 1979, because the expenses for technological maintenance and implementation had become too high.

All in all it was a good experience, and the studio is still there, in Piazza Euclide. We sold it to Marco Patrignani, who is still the owner. I recorded almost everything there.

Composing for film means conceiving a type of music that does not reach the listener “acoustically,” as in a live concert, but through mechanical or digital reproduction.

How often have you used a piece and its orchestration in such a way that the outcome stands for itself from an acoustic standpoint, and how often have you instead relied on mixing as an added resource for your orchestrations?

Generally, I write in such a way that the music is acoustically balanced and would work as well in a live concert. The score that gets to be performed in the studio is recorded without the need to emphasize some parts over others. Then, during the mixing phase, one can take some liberties and change some small things. Nevertheless, I compose for the orchestra in a classical sense. When mixing, one may treat the oboe with a little echo, percussion with a particular reverb, or specific balancing issues may be corrected. As it happens, even when everything appears to be fine in the recording room, a microphone may exalt a detail that is not acoustically relevant and for this reason needs to be lowered. It is a complex process.

Then again, in some cases I created scores by exploiting the creative potential of multitrack recording and mixing, as was the case for the multiple or modular scores I composed for Dario Argento’s early movies, for Yves Boisset’s films—one for all, The Assassination (L’attentat, 1972)—and then for Damiani’s films, up to my most recent experiences with Tornatore.

Studio overdubbing represents an option, a potential, as much as the use of effects and technology in general, which has dramatically improved in recent years.

The composer’s work therefore can and should embrace these resources, in my opinion. Composers must foresee and speculate on the new “instruments” at their disposal and integrate them into their musical thinking, without forgetting “tradition,” so to say.

Could you give me an example?

I could tell you how I worked on Tornatore’s The Unknown Woman, because that score represents a step forward in my way of composing music, especially from a combinatory point of view.

The film is based on flashbacks and recollections. The way I had envisioned it demanded that I keep several options open during the mixing and editing stages, until the very last minute.

Recording sessions were organized with this idea in mind—we needed music that could marry “whichever” visual cut we’d eventually end up with.

I wrote seventeen to eighteen pieces that could be intermingled in multiple ways. They could be overlaid as double or triple counterpoints, so as to engender a different sound material every time. I did three recording sessions in total, partly because I believe the director has the right to know what the potential outcomes of such a radical experiment might be.

In the first session, I recorded all the themes. In the second, I recorded the modular cues, which could then be combined and overdubbed as needed; at that point, Peppuccio and I assessed them and we picked different takes for the editing. In the third session, I recorded various thematic options that would fit in with the material from the second session (among these were the piece “Quella ninna nanna” [That Lullaby] and the strawberries theme).28 This last session was carried out following a more traditional procedure, that is, I conducted the orchestra hitting the sync points as the visual track played.

This procedure harks back to older experiments. . . .

Definitely, back to my time with the Gruppo d’Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza and to the multiple scores I had first created for Argento’s film. . . .29

This is also a very time-efficient way of writing. The compositional effort is considerably optimized because you can continuously derive new pieces from different combinations of partial material.

Yes, although this is relative. I tend not to focus so much on how long it takes to compose a score, but rather on how well a new method works for me—so that I don’t get bored. Besides, I can’t use this composing procedure all the time, it must be justified, there needs to be a reason to use it.

Certain directors’ demands can be met in different ways according to what they wish and what their film needs. However, these experiences also serve the composer to experiment with new ways to achieve a result (which can comply with or radically differ from expectations). It is curiosity that triggers the search for new pathways.

Thanks to this system, you save the option to reach a final decision together with the director for later—for the mixing phase—almost as if it was a chess game. . . . This is highly effective for a film’s production process. . . .

And not only. Following traditional methods, composers find themselves at a vantage point, even if it doesn’t seem so. When a piece is recorded, directors are not left with many options. They must accept it as is. This system, instead, enables the director to step in and make changes up to the editing stage and even afterward.

Before, directors had no choice, at least not as many as the system I invented allows.

Still, you can only afford to work in this way assuming you trust the director with whom you collaborate.

Of course. Otherwise I would go crazy, as the director would too. Similar procedures make the director co-responsible for the music. Therefore, they cannot be shared with everybody, because not everyone would accept such an open-ended system. I was making this same case when we were talking about Petri and A Quiet Place in the Country.

I repeated this experience and brought it to the next level, especially on “Volti e fantasmi” [Faces and Ghosts], from The Best Offer, in which I recorded each part independently.30 I made a first mix myself, and Fabio Venturi made the second at his house, but in the end we didn’t use it. Tornatore and I made other mixes directly in the editing room while syncing them with the visuals.

When we were done, overcome with emotion I told Peppuccio, “This is both a point of arrival and a new start.”

For instance, should Tornatore ever manage to make Sergio’s dream come true and realize his own version of The Siege of Leningrad,31 I think I would use this system. Perhaps after recording and mixing I would be able to chronologically order all the fragments and draw out a score, which I would then reperform exactly as it would be assembled in the film.

Obviously, working in this way would be rather expensive, but for a production like Leningrad, should it ever happen, it might be possible. . . .

You speak about your latest experiences with Tornatore as the beginning of a new thread of research.

These new compositional resources are very stimulating for me. I am interested in the unpredictable, in chance and unexpected outcomes, even more in that my music always reflects a defined score, a fixed form and structure, my own mindset. But the different options that this system makes available are all acceptable. Especially in regard to the images.

This sort of “organized improvisation,” or “written improvisation,” makes the aleatory and the determinist aspects coincide. I guess that pure improvisation would not excite me as much, but cinema has an aleatory facet that needs to be integrated into the compositional process. All this—uniting chance and randomness with a rational and precise organization—is possible thanks to the technological advances.

With my ideas, with this way of working, the director becomes a sort of coauthor of the music—I still write all the music, but we improvise together in mixing a piece with the rest of the soundtrack. For these reasons, at my Academy Honorary Award acceptance speech in 2007, I claimed that I was at a starting point in my career, rather than at an arriving point. I was specifically referring to these new paths I was discovering, and particularly to those I was experimenting with when working on The Unknown Woman.

I had gone through a period in which I took fewer risks, but that film represented a leap forward!

I wish I could always start with a “leap” like that, but I understand that not every film offers room for similar experimentation. The Unknown Woman was sort of a prelude to what I later realized with The Best Offer.

The modular writing enabled me to elaborate upon fragments that I could then superimpose in collaboration with Tornatore. The parts are not pre-organized; their combination takes place either during the performance, via the entry and ending signs I give to the instruments or to the orchestra sections when I conduct, or during the mixing stage.

In 2007, after being honored with myriad prizes and acknowledgments of all kinds, you received an Academy Honorary Award. How important was that for you? And how do you explain the belatedness with which you received it?

As far as the belatedness, I wouldn’t know what to say. What I do know, however, is that for a long time I was quite disappointed for not having won an Oscar, especially considering I had scored so many American movies. It was significant for me to receive one, eventually.

Another acknowledgment I deeply care about came from the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia; they appointed me the title of “Academic.”32 It was important for me, especially after years of feeling snubbed by the academic music world.