Example 4.1a: Ascending fifth leap

ALESSANDRO DE ROSA: Ennio, I have a confession to make. I’m a little embarrassed, but I’m sure you’ll take it the right way.

ENNIO MORRICONE: Tell me. . . .

A long time ago, before we had ever met, I had this dream. I was in your house and we were talking, just like we are now. At a certain point, I stood up and saw a strange statuette in a glass showcase. After taking a closer look I realized it was an Oscar—one that you hadn’t yet won. The showcase was right next to a half-open door.

Now, I know my question may sound odd and perhaps indiscreet but where do you keep your Oscars and all your other awards?

I’m glad you’ve waited to tell me this.

He smiles and stands up.

Come with me, I’ll show you.

We put away the chessboard and call off the game. Once again Ennio was winning by a long shot. I follow the maestro as he walks toward the inlaid door protected by Codognotto’s Warrior. That must be his studio. . . . We stop in front of a closed door. I had already noticed that Ennio always has keys hanging from his belt. He opens the door.

I usually never let anyone in here, you know. Brace yourself; it’s a bit of a mess inside.

We enter. In the studio there are some tables and a desk where he works. My eyes fall on some pictures: Maria, their children, their grandchildren. . . . It’s a big room, though not huge. There is an antique organ nestled in between floor-to-ceiling bookshelves on either side. I can spot all sorts of books, from C’era una volta la RCA [Once Upon a Time at the RCA] to a music encyclopedia;1 a vast collection of vinyls, cassettes, and CDs; music books, daily newspapers, and magazines scattered on the sofas; and piles of paper of various kinds lying on the tables. I would not define it as a particularly ordered room, but it is clear there is method. In sum, it’s lived in. Right in front of me is a massive shelf on which I can see all his scores collected in hard-paper folders and covered in white fabric—indeed, white is the prominent color. The enormous score that Morricone composed for the synchronized edition of the 1912 silent film Richard III stands out among the others.2

I feel a strong, particular connection with Shakespeare, among other authors.

He points at a wooden shelf.

You see, this is where I keep my awards.

I turn and finally see the golden statuette. This time, it’s a real one in front of me, unlike in my dreamy vision. Next to it, is his other one. Differently from my dream, there is no glass showcase, but the wooden shelf is actually behind the door. Collected are practically all the acknowledgments of Morricone’s career. Some David di Donatello Awards, several Silver Ribbons, honors from chiefs of state, the Polar Music Prize (that is, the “Nobel Prize for music”), one Grammy Award, a big Golden Lion. . . .

You see, there’s no glass showcase!

You dedicated both your Academy Awards to your wife. . . .

It was deserved and the right thing to do. She gave up a lot to devote herself to our family and children, while I was composing. We saw little of each other for over fifty years—I was either with the orchestra, or closed in here working. Nobody could enter, except for her; that was her special privilege.

When I work I’m under pressure until I finish what I have to do. It can be a pain to have me around; Maria took me, supported me, and accepted me for what I am.

Are all your children far now?

Alessandra and Marco live in Rome. The other two have been living in the United States for a while now, Andrea in Los Angeles, Giovanni in New York. Thanks to that computer we are able to stay in touch. . . .

He points at it.

I Skype with them, I find it convenient, although it’s quite odd to see my grandchildren grow through these screens. . . . However, if it wasn’t for this technology, the distance would feel even greater. Hence why I gave in and use it.

Are you kidding? People have tried to explain to me how email works numerous times, but I’m just fine with my telephone and my fax. I’ve always relied on paper sheets to keep to my weekly schedule—I split a sheet of paper in seven parts, write the days on it and fill in all my appointments and commitments for the week. Agendas bother me and I just don’t trust computers.

I know that today some people use them to compose. I experimented with them in the studio as well, but I don’t see how it’s possible to write for a big ensemble on a screen.

Why?

How can someone oversee the entire page at a glance? How can one check the vertical disposition of the voices? You cannot just enlarge a detail and neglect the totality.

Well, it depends on the software. Nowadays there are screens that are wide enough for big scores.

Do you use a computer to compose?

Very often.

Well, I need paper. To exert graphic control over the score might well seem a matter of secondary importance, but for me it’s fundamental. Being able to observe the density of the musical material at a glance, just by glimpsing at the sheet, is something I find reassuring.

Pasolini used to say that writing was a habit, an existential addiction for him. Why do you write?

Writing music is my job, what I like to do, and the only thing I know how to do. It is an addiction, yes, a habit, but also a necessity and a pleasure: the love for sounds and timbres, the chance to sonically shape my ideas, to transform an interest and a curiosity—my very imagination—into something concrete.

I don’t have a real answer to your question, I can’t say where this necessity, this urge to write originates. I don’t think there’s any fixed rule. I have so many motivations. . . . Perhaps it feels too complicated to pinpoint it and define it once and for all, precisely because there’s something so intimate and private to it, which does not want to be communicated.

Is there a particular condition in which musical ideas come to you more often?

They usually come when I least expect it. In any case, the more I work, the more ideas flow. Sometimes my wife sees me lost in thoughts and asks me, “Ennio, what are you after?” “Nothing,” I answer. In fact, I may be singing a melody to myself, an idea, mine or someone else’s that has gotten stuck in my head. I guess it’s something like a professional deformation. These symptoms tend to “worsen” as the evening approaches, when, after a full day of work spent at my desk or, worse, mixing and recording in the studio, I have dinner and go to bed. On those kinds of days, I take music with me under the covers. It’s unbelievable that Maria has put up with me for all these years. Sometimes sonic and musical ideas surface in my dreams. In the event that some of them persist into the half-sleeping phase, I sometimes even manage to catch and transcribe them. For years I have kept a notebook and staff paper on my bedside table. Depending on the type of idea, some can be notated in staves, while others require regular paper.

Do you think that the composition process originates from an act of will or from something bursting out, such as urgency? What’s your trigger?

It depends. Music springs out when I’m faced with the challenge to conjure up an idea, to give birth to it. Sometimes the idea may come up later, sometimes it may not materialize at all; other times it may show up randomly. When any of the above happens, I can either abort the idea, or elaborate it, or even transform it into something different. A composer imagines and writes music just like another person writes down a note or a letter.

As for film music, I put a lot of thought into it. Even when I’m not able to come up with anything extraordinary, I must force myself, because there’s a signed contract and a deadline, and I must be ready to record music that is good, dignified, and respectful of another author’s creative work.

When it comes to another kind of music, which I refer to as “absolute,” I tend to wait for a specific intuition that feels right—I can be attracted by a timbral idea, a combination of sounds, specific aleatory passages of the orchestra, an instrumental configuration, the option of using a choir. . . . In other words, parameters can be diverse and uncontrolled, independent from my will. This is at any rate how it works for me. In case there’s a soloist who commissions a work from me, or an ensemble that is going to perform it, that becomes my starting point.

In any event, in absolute music I prefer to work without deadlines. Recently some Jesuit fathers asked me to compose a Mass.3 I accepted, but specified, “I will deliver it to you when it will be finished. Only then will we be sure that it’s been written.” I don’t like due dates. A composition is an organism with a life of its own, which needs to be respected. I have often felt the same responsibility for a new music piece that one would feel for an offspring.

Sometimes I even felt like I was “pregnant,” so to speak. It is a process that deeply motivates and intrigues me.

Have you ever gone through crises of productivity and creativity?

I must confess that I haven’t been very keen on writing in recent years, but then again, I do it anyway and still enjoy it. In general, I’ve never experienced crises when faced with deadlines; I’ve always managed to meet them.

Once, however, I was considerably late when working at Once Upon a Time in the West—I couldn’t come up with new themes. The rumor that I was going through a crisis reached the ears of Bino Cicogna, the film’s producer. He didn’t think about it twice, he went to Leone and told him, “Why don’t you call Armando Trovajoli? This is a special kind of western, call Trovajoli.” They made an audition with him and even made a demo recording without telling me anything. When Leone heard Armando’s audition, he wasn’t convinced about it. Meanwhile, I had gotten over my crisis, unaware of what was happening. For a long time I knew nothing of this story, until one day Donato Salone, my copyist at the time, revealed all. When I demanded an explanation from Sergio, he replied, “Ennio, you were dawdling, what else was I supposed to do?”

Apparently it’s not convenient to have a creative crisis when in the film business.

He smiles.

You get the point. All in all, I felt bad about what had happened—for Sergio, but also for Armando, who had no qualms about replacing me. Similar episodes occurred on other occasions. . . . From that moment on, whenever I’m asked to replace someone, I first speak with them to understand their point of view, even if I don’t know them personally.

What is the function of a crisis phase, in your opinion?

I don’t know where crises come from, nor what triggers them; what I do know is that any creative process has to come to terms with a crisis sooner or later. At my age, it’s not easy to reinvent myself on every occasion. “Ennio, can you still make it?” I sometimes ask myself. Then I roll up my sleeves and get back to work. Anyway, I did experience crises when composing absolute music. The real trouble with composing this kind of music is getting started and then finding the courage to throw everything away two or three times. It’s been a while now since I have last written any absolute music.

I’m very self-critical and essentially a pessimist, and I don’t feel I am the right person to judge my own work. For this reason, I seek counsel from trusted people who can offer feedback or critique.

In film scoring, when I had troubles finding my so-called inspiration (though I don’t like this term), I had to resort to something else—craft. One cannot always find the right idea that perfectly fits someone else’s work. Although I approach every work with the highest respect, I can’t always expect things to run smoothly the way they did in The Best Offer, where the film itself dictated me what I had to do. . . . That would be the ideal situation every time!

What was it like on that occasion?

When I read the screenplay, I was particularly struck by the sequence in which the antiques dealer [Geoffrey Rush], who is the main character, enters his vault and unveils his treasure, a room safeguarding dozens of portraits of women. Such an intimate moment led me to compose a piece that integrates several female singing voices. The voices were meant to emerge as if they came from the paintings and were evoked and materialized in the protagonist’s fantasy. They were to liberally intertwine in a free counterpoint, reminiscent of a disjointed, disorganized madrigal—or rather, organized but improvised, improvised but organized.

So would you call moments like these “inspirations”?

Yes, in that case the idea sparked intuitively from the film. But make no mistake; even then it was only an idea, which had to then be elaborated with significant effort. By inspiration, I mean intuition, which sometimes can be generated from reacting to a stimulus that can be contained in the images or in a text, or produced by an unpredictable event, like a dream. Whatever the case, I consider inspiration the exact opposite of being without ideas. The romantic usage of the term, linking inspiration to the heart, to love and feelings, has never convinced me, yet it has affected the way most people perceive musical and creative professions today. So many times I have been asked about my inspiration. . . . I wonder why this mysterious realm is so intriguing to people. What’s your take on this?

In my opinion, this concept thrives because we all seek reassurance. Something that “suddenly falls from the sky” makes us feel less lonely, as it proves the existence of a mystery we can be hopeful for. And when this mystery is conveyed by a “genius,” an “artist”. . . well, that is when the reassuring and authoritative figure people have yearned for is manifested in the flesh, confirming our hopes.

I have always been wary of the word “genius,” and it always brings to mind a quotation, which I think was by Edison: “Genius is 1 percent inspiration, 99 percent perspiration.” Sweat, hard work! If we want to speak about inspiration, then we must become aware that it just lasts for a moment; once that moment is gone, work remains. You write something, erase it, throw it away, and start again. There’s no such thing as falling from the sky. Sometimes the idea contains the seeds of a possible elaboration within itself, but in general, one must struggle. I realize that thinking about music in this way might be less appealing.

He smiles.

Well, anyway, it still is a fascinating mystery and we are trying to explore it. Going back to your instinctive reaction to Tornatore’s film, did you eventually follow your initial intuition?

Yes, as I usually do. When I have the right idea, I let loose, following my original instinct. I transcribe the idea to best mirror it, and this helps me get over the initial panic of a blank page. Only after the recording stage, or in that case after receiving the final appreciation of Peppuccio, the audience, and the critics, was I able to turn back and reflect on what I had done. At that point I could retrace all the previous stages of that idea, the various experiences that had crystallized before that final synthesis.

I realized how that piece of music had become my way of expressing an old subject in a new way. A few of my past works were forerunners, such as Bambini del mondo, Sequenze di una vita [Sequences of a Lifetime] (1979),4 as well as my score for The Devil Is a Woman (Il sorriso del grande tentatore, 1973) by Damiano Damiani.

I mean, one could even have a brilliant inspiration or intuition, but the process of elaboration depends on what one has acquired throughout years of training, deriving from the culture and the history one has absorbed, assimilated in depth before being able to give it back in some form.

I wrote the theme of 1900 by Bertolucci, like many other themes that are today very famous, in the editing room, in front of the film, in the dark, with a pencil and a blank piece of paper. Composing melodies is something I have been doing since I was a child, because my father taught me how to do so. Yes, the images did suggest something to me, but it’s also true that I trained for years in order to achieve that ability to synthesize thoughts into music. Harmony, counterpoint, historical forms, experimentation—everything comes into play.

By the way, writing a theme is not the most complex task—the intuition, the idea, or whatever we may call it, more often than not, is not confined to melody. For example, for A Pure Formality I created the whole score based on the screenplay’s structure. The theme of the last song, “Ricordare,” is made of melodic fragments that surface as the protagonist, writer Onoff [Gérard Depardieu], gradually recovers his memory throughout the story. One moves from trauma to settlement, from dissonance to consonance.

You emphasized how important past experiences are for you. Stravinsky, a composer you love, on the contrary avowed that he demeaned his past every time he composed.

For me it is different. I believe that feeling the echo of the past resonating in my present is fundamental. In order to be able to do what I do today, I must acknowledge the pathways I have taken, those that have fabricated my culture, my musical and personal identity. This “system of references” is not of public interest, it probably doesn’t reach others as an element of communication, but it is crucial for me as a personal drive—it pushes me into writing. For instance, my idealization of Frescobaldi’s, Bach’s, and Stravinsky’s melodic cells—which I have included in so many of my applied and absolute music pieces—stems from a similar intimate urge.5

When I wrote the Mass I was referring to earlier, which I later entitled Missa Papae Francisci, Anno duecentesimo a Societate Restituta [Lat., Mass for Pope Francis, in the Two-Hundredth Anniversary of the Societate Restituta], I decided to use a double chorus to pay homage to both the great Venetian School, from Adrian Willaert to Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli, and my score for The Mission. Similarly, for my Fourth Concerto (1993) for two trumpets, two trombones, and organ, I devised a stereophonic effect through the spatialization of the two pairs of trumpets and trombones because I wanted to evoke the double chorus of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice. I feel the need to link present choices to tradition, to re-enliven my past in my present, even through writing.

An “eternal return.” György Ligeti used to say, “Be original!” More modestly, I’d rather exhort one to be honest, although first we should have to agree on the meaning of these terms. What do you think about originality, honesty, and sincerity in music (and beyond)?

Sure, that’s a difficult one to answer. . . . Be original?

He whispers to himself, almost as if to buy time. . . .

I believe I’m honest as far as what I think and write. Decidedly, I have influences, and can easily name them: Petrassi, Nono, Stravinsky, Palestrina, Monteverdi, Frescobaldi, Bach, Aldo Clementi to an extent, perhaps a few others as well. But this doesn’t make me dishonest. Well, I don’t tell myself while I am writing, “Now let’s get out of trouble with this passage in the style of Petrassi or Palestrina. . . .” This is not how it works. These loves are so deeply entrenched in me that I no longer notice their presence. I limit myself to write, the important thing is to be self-satisfied, at least in that very moment—honest, at least in that moment. Afterward, I am open to review my choices from different angles, listen to criticisms and praises, rethink the whole thing from the outset.

Should I deem myself dishonest because sometimes I am forced to rush my writing, or because in given situations I didn’t wait for that pure, raw “inspiration” to reach me? I don’t think so.

The moment I read a screenplay or watch a film I know which idea is going to be the right one, the strongest, and the one to go for. There have been times, especially in the past, when I would have wanted to be given more time to develop an idea, but what I would hear in return typically was, “We’re going to tape everything in one month.” My fantasies would end right there. I ought to give my best anyway, this is what my job is about—to keep up to the task I am assigned, rescuing myself and my work.

I have always worked trying to not give up my highest ideals. I ended up writing very tonal melodies following inner procedures and a research path that would make me feel gratified with my conscience—that is to say, the conscience of a composer who carries the cultural baggage of studies and experiences that are “other,” different from applied music. This kind of professional and artistic honesty, which I have tried to embody in every professional circumstance, has often been very much overlooked.

Some things I have written could be analyzed more in depth, but unfortunately this kind of attention is usually not reserved for film music. I am not interested in claiming anything, but surely I defend my personal intention to give applied music the artistic and compositional dignity it deserves.

In sum, originality is something one may come across only once in a while?

Exactly, just like that.

The way you talk about it, you don’t seem to think of the composer as an inventor, someone who creates from scratch, but as someone who recovers, rediscovers, and envisions links between things that already exist.

A composer does draw on history in part, but if that was it, it would be like saying that all the music of the past, the present, and the future already exists, and composers merely transcribe something that is already there. Composers instead think, reflect, and unconsciously devise techniques based on the music they love or they have already composed. They appropriate the things they were inspired and struck by and look for new formulations.

It’s totally normal. In short, the history of music has not been for nothing, it has undoubtedly left us with something.

He becomes emotional.

And yet, were I to concede that it is just a matter of “recovering” or attuning to something that was already there, it would mean to admit that I have been going in circles, always rewriting the same music. Taken out of context and considered as the only answer, this possibility frankly depresses me. After all, where does this kind of collective memory that preserves everything really stand? What does it look like?

For this reason, sometimes I think that the act of composing concerns the creation of something new, something that didn’t exist prior to a specific need felt by the composer. Perhaps I’ve simply needed this idea to go on, and I cannot deny that it still pushes me forward today.

From time to time, the solutions that I devise in my work may lead to nonoriginal outcomes. However, because they derive from personal, uncontrolled, and incontrollable discoveries (they may even appear as such for a short time, but at least in that very moment they belong to me in their totality), they are what challenge me and make me continue writing.

In the moment of invention, during that instant of illusion, I find myself marking a step in the right direction and for a moment freeing myself from every burden, before returning to look around me immediately after.

So this is how you see the act of composition: claiming your space in history, perhaps your own story, for an instant, in the present, in the moment. And even if this may be an illusion, it is functional in life, to moving on.

It is an act of focusing and detachment that helps me realize the idea, that ultimately coincides with the idea, and is inextricably linked to the here and now. I remember when, for Marco Polo by Montaldo, I started to simply work over two chords in a specific piece. The alternation between the first and fourth degree (the first inversion of A minor and D minor) produced a monotony that reminded me of the static harmonies of certain Oriental music, in which a motionless harmonic discourse often does not lead anywhere. As a reaction to this concept, in the central part of the piece, I began modulating using exclusively plagal cadenzas.6 That was an extemporary invention for me. After I recorded the piece and the mix was finished, I found some involuntary reminiscences of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade, which evoked the Oriental world as well. The outcome I achieved was similar to Rimsky-Korsakov, although the reasoning behind it was completely different.

I thus think it’s important to let myself go at work, and only afterward consider the eventual attributions of what I have created. In sum, although invention and reinvention may appear as opposite attitudes, I believe that both of them are in a sense valid and legitimate.

Perhaps it is because of this eternal dilemma—invention or recomposition—that an artist is so often perceived as a medium or a genius, that is to say someone who enjoys a privileged contact with mysterious energies, be they internal or external, divine or psychological. These beliefs are still strong today; but maybe, as we were saying earlier, they are just functional to mankind in that they exhibit this insoluble ambiguity.

The idea of the medium makes me smile, as much as in a different way the idea of the genius amuses me. I rather see myself as an artisan. When I lock myself up in my studio and sit at my desk, composing goes through personal, concrete, and material activities—craftsmanship, in a word.

So you don’t compose at the piano, do you?

I directly write on the score. I heard that some, even illustrious composers, are used to composing piano reductions—compressed scores—to then orchestrate them at a second stage. It’s a matter of personal preference. A system of that kind simply doesn’t suit me, because I consider the orchestra or the ensemble as fully expressive tools, and moving from a piano reduction to the orchestra would be a flawed strategy for me. I usually turn to the piano only in double-checking what I’ve written, or when I am stuck and can’t manage to get where I wish. I also use the piano to present directors with musical ideas for a film. I cannot let them wait until we are in the recording studio before they know anything about my music. Certainly, what I play for them at that early stage is nothing more than a “little thing,” and I must hope that they will be satisfied once they hear that idea performed by the full orchestra in a more complete and elaborate form. That “little thing” shall in fact change in the recording room, because the orchestra always gives me something new in return.

Just to be clear, I am no modern wonder. Every composer who knows music and has studied composition, anybody who has mastered the technique and the ability to think of a musical fact, is able to write directly on staff paper without first needing a piano.

I even choose the kind of paper according to the type of musical idea I have in mind. I often start by ruling the staves in advance with tight or loose bars depending on my need—this helps me predict a sense of space. I can graphically foresee the interaction between the parts, their movements, their dynamic; still, I don’t fall into graphism, unlike Sylvano Bussotti, who designs scores that resemble contemporary art paintings.7 In some cases, I simply know in advance what I am going to write. Other times, however, quite the opposite happens—the paper constrains my original idea.

When I am chasing an idea that is widely varied in terms of musical and spatial expression, I go for tall and wide staff paper, I have it specially designed for that purpose. Seeing the blank space provokes a burst of ideas in me and renders the whole process interesting. . . . Then I might even think, “Let’s not use such a wide space here,” because it is as though I knew in advance that I’ll use it later, even though in that moment the idea has not yet materialized. That same idea burgeons in front of a huge empty space.

He gets emotional.

More on that, I write better when bars are not there, it makes me feel freer, although usually film music requires the use of bars.8

I remember that when I was a student I eagerly examined Wagner’s scores. I thought—and still think—that he felt the need to erase all the resting parts from the score. Almost as if he was bothered by them. He wrote in such a way that he could visualize all the instruments playing at a given moment in a very focalized manner. When one instrument rested, Wagner didn’t leave the staff blank, he got rid of it, so that his page was always full.

He probably enjoyed looking at thick, constantly flowing textures. I don’t think he needed to save on paper. This is obviously not to suggest that this is the only difference separating me from Wagner’s greatness . . . no debate about that!

In fact, Wagner doesn’t seem like the kind of person who would have saved on paper, nor did he spare his own ideas. . . . Speaking of musical ideas, in what shape do they usually come about?

In cinema, ideas and consequential options derive from several “contingent” factors, not the least the screenplay and the images; sometimes they burst out from an unexpected intuition. With absolute music, on the other hand, it is different.

In my Fourth Concerto, for instance, I felt the necessity to pair two trumpets and two trombones to the organ’s right and left. Nobody or nothing required that to be so, but I was interested in obtaining a sense of space, besides the specific timbral blend.

The commission of Vidi Aquam. Id Est Benacum (1993), for soprano and small orchestra, was very binding. In a way it was also unique in its genre, in that the location was clearly defined—the shore of Lake Garda. In that case I chose to use five quartets, each one differing from the other and entering one after another, one into the next, gradually building up to twenty-seven combinations. Why did I come up with such a solution? Where did that specific form come from? What made me decide to adopt a selection of pitches that conjured up a static and prolonged modal ambiguity, which embraced the soprano’s voice with two added sounds only at the end?

Everything originated from the idea of an apparent stasis, full of internal life, which that particular location had suggested to me.

When I write for films I can even lend myself to compose “romantic” music; but when I think about a music that doesn’t necessarily aim at amplifying emotions and feelings, a music that is not associated with moving pictures, in short that is not subjected to constraints but concerns my inner self, then I seek for a broader and more abstract kind of expressivity.

However, to partly contradict myself, I shall mention that when I wrote one of the pieces for Correspondence (La corrispondenza, 2016) by Tornatore I tentatively started from a reduced score for solo pianos—four pianos, to be exact. What did the pianos play? And why four? One pianist could not perform all the superimposed parts alone, that’s why I needed four different players, each of whom performed one note at a time (it was sufficient to use even just one finger).

The idea, in that case, came to me straight from a reaction to the film’s plot. It’s the story of two characters who are very close, yet far apart. My initial idea was none other than a theoretical speculation, almost detached from everything; it burgeoned from my reasoning about this “close distance.” The way I thought of and developed this piece can be compared to how I usually approach absolute music. Only after elaborating it did I realize that it was a good intuition, and yet it turned out to be too static when extrapolated from its applied context, and too little expanded to be used in the film. Eventually I decided to discard it, but who knows, something different may come up in the future from this idea.

This makes me want to rephrase my previous question, this time asking you to envision a moment in which you are free from constraints; how do musical ideas show up in this situation?

Timbre comes before anything else. Intervals come after for me, whereas timbre is fundamental; to think of an instrument or a combination of instruments—an ensemble—is always a source of inspiration for me. Only afterward do I reflect on the form, the structure underlying a musical composition.

Speaking of which, even if I no longer believe in the traditional notion of the musical form,9 I think that it remains no less central a parameter for undertaking any new composition.

When time is not dictated by the synchronization to the moving image, writing is freer and one can devise a personal form for every new composition.

Sometimes certain elements themselves define and structure a form, almost as though every composition allowed for a range of appropriate options that self-generate forms, in a sense. When this is the case, it’s not even necessary to think about it. This reflection comes to me a little later in the composition process, after I have already chosen the instruments. Many variables come into play during the working process—writing, erasing, correcting, asking myself whether an entrance should be delayed or anticipated. It is not so much a matter of reflecting, but a subconscious process that becomes pragmatically concrete as soon as the pencil marks a rest or a note. At any given moment new alternatives, new options open up. A piece may undertake several different directions—which is the right one? All of them and none of them, but this is precisely what makes each composition and each composer different from one another.

In your experience as a composer, as much as in your life experience, would you say that you planned your next steps and choices in advance, or that you first acted and only later thought about your actions?

In a sense, I’d say I did both things. Much of what I have, but also haven’t accomplished in my life and in my compositions, I have interiorized thanks to a progression of practical, often contingent experiences. Thanks to my perseverance and ambitiousness, I’ve been able to react time and time again to new stimuli. All of this has led me into a more and more personal synthesis. For instance, after attending the Darmstadt Summer Courses in 1958, I felt an urge deep down to react to what I had witnessed there.

I had already gotten closer to some of the idioms and modes of composition of neue Musik in those years. Before leaving for Germany I had written 3 Studi [3 Studies] (1957), for flute, clarinet, and bassoon, and Distanze [Distances] (1958), for violin, cello, and piano. When I came back still immersed in the suggestions I had gathered there, I composed Musica per undici violini [Music for Eleven Violins] (1958).

Then I found myself becoming an arranger in the pop song industry and a composer in cinema. Both activities were very far from what I had envisioned for my future. In a nutshell, every time I’ve had to face what life had in store for me, I did so to the best of my abilities.

Today I feel like I have developed quite a different attitude toward composition than the one I had at the beginning, at least as far as my way of writing is concerned; however, the seeds I planted during those experiences, as well as the techniques I learned, triggered a process of gradual transformation and stylistic contamination, which, I believe, have little by little come to define my personal voice, my timbre, my identity.

To be clear, this is not the way I reasoned back then, I simply wasn’t aware of it.

How do you relate talent and commitment?

For my part, commitment has always been thorough and even a quite distressing factor; today, after such a long practice, I can say I have developed some musical talent. I say this because my early intuitions, which I could perhaps define as “inventions,” were mine, sure, but they initially didn’t play such a key role. It was arguably through their gradual development that they became important; thus, they should be traced to a non–completely conscious process, a sort of underlying attitude that is part of my way of being. It is the totality of ideas and their mutations that has produced results over time. Doesn’t this also depend on the commitment one puts into progressing? Perhaps it is not inappropriate to say that talent is what produces an improvement that is unnoticeable as it happens; every old experience, even the most insignificant, may lead toward an unforeseeable outcome, one that nobody could have ever imagined at first. Commitment, on the one hand, depends on conscious will; talent, on the other hand, may then consist in the unconscious element at the service of professional and creative improvement.

Therefore you see talent as a process, not as a starting point, as it is usually reputed to be.

Yes, I believe that talent is a consequence of passion, but also of exercise and discipline. These are ultimately the ingredients that make good qualities emerge. As for me, I have never thought of myself as a talented person. I’m telling the truth, I’m not being falsely modest. Today I do realize that there may have been some talent here and there, but I keep thinking of it as an evolution.

Although we cannot touch it or hold it in our hands, and despite the fact we could supposedly do without it, it seems that music has accompanied mankind since its origins. A sound; a magic and enchanting phenomenon; a myth; a divinity; a category of perception; a sociocultural construction—defining music has always given intellectuals and scholars a hard time, whether they have related it to subjectivity as well as to mathematics, to becoming as much as to being.

Where do you think music comes from?

Once upon a time, perhaps, one of our ancestors discovered how to produce sounds via vocal cords; little by little, by modulating their tuning with increasing accuracy, someone may have succeeded one day in transforming those sounds from yelling into singing. A voice, per se, produces melodies, even when we use it to speak. Obviously, there is no way to be sure about my theory, but I see music as born with that one ancestor, whom I have often called the Homo musicus.

Similarly, one day the ancestor hit a rock with some bones, creating at once a potential weapon and the first percussion. Then he or she came across a pipe with holes, through which the wind had blown before. Maybe, through experiments and tries, the ancestor realized that sound was not only produced by blowing, but also by the vibration of a leather membrane, of a percussed metal or stone, as well as of plucked strings. Instruments, timbres, vibration phenomena, overtones (later theorized by Pythagoras) were then discovered.

The human heart provides a more or less regular pulse; therefore, hitting a percussion can turn into a musical call understandable to anyone. It’s not by chance that a lot of primitive music is based on percussion and song.

In life’s most important moments, from birth to death, in military as much as in religious contexts, music amplifies human values and makes events more exalting, providing a sensual and exterior, though most of all interior, clarification of spiritual human feelings. These associations jump directly to our present time, because a certain way of applying music to images triggers our instincts and emotions in a very basic and similar way, especially in advertising.

What is music? We will probably never agree on a satisfying answer, but the question has always borne a relevant philosophical weight. Perhaps “making music” responds to a human need, which is even deeper than creativity itself—something that’s related to the impulse to communicate.

Creativity and communication appear to be means by which humans affirm themselves and express their belonging to something bigger—in other words, they are means to survive. This starts already as infants; the attempts made by newborns to communicate with their mothers are necessary for life, they are sturdily linked to the instinct of survival.

Think about yelling, as I was mentioning before: it serves to affirm our existence in the face of other people and the entire world. The first way to make a shout become a form of communication was to transform it into singing. It must have seemed like magic. Singing became in turn a coded way of communicating, developing along the uses and customs of a society, or at least the part of a society that produces and consumes culture. Singing became a generally shared code between those who make music and those who listen to it.

A language?

A language, which has undergone processes of mutation and evolved or regressed with mankind, as happens with all sorts of language. Beware, though, I don’t believe in music as a “universal language.” Communication is based on complex and varied parameters, which are in most regards cultural, meaning that they are limited to geographical areas and historical periods, not unlike what happens with tongues, which are different for any epoch and country in the world.

How does communication happen in music?

There are those who conceive and produce music, and those who use it. Media, that is, the means through which musical communication takes place, may change through time—performers, disc, radio, television, the Internet . . . all of these are musical media. Composers are influenced by their own musical culture, by their habits, by the styles they have been accustomed to throughout their training and experience, by their knowledge of musical idioms and music history (at least the ones they should know, even if sometimes they don’t). At any rate, however, even the freest among composers draws on practices that have consolidated over time, be they genres, forms, ensembles, or writing techniques.

Do you mean the linguistic codes of a society, of a culture?

I call them constraints, some of them may be conscious and others unconscious, musical and extramusical, interior and exterior—all of which shape the individual to live in a given context.

Then there are the receivers of musical messages—the listeners or users. They too are conditioned by their own culture and their musical experiences, as well as their listening habits. As an example, some years ago I found myself arguing with a person who had confessed to me, “I don’t like Mozart, I find his music boring, it’s like he’s always writing gavottes and minuets. He is predictable.” It sounded like a daring statement to me, and in replying I tried to defend Mozart’s genius by referring to his historical and linguistic context.

What was sacrilegious to me was truth for that fellow. Listening to Mozart bored him. For one thing, I could not force him to like his music, but my conclusion was that he had probably listened to Mozart while being accustomed to a different kind of music. Then I reflected upon the fact that abandoning oneself while listening to an unusual piece of music might not suffice in order to appreciate it. One can still be deaf even when confronted with something he or she can recognize to have some kind of richness, something that our culture presents to us as the expression of value and quality.

Once again we go back to our experiences as listeners, to the tools we have to understand music, which more often than not are weak because nobody taught us how to develop them—I’m especially thinking about schooling, which should be completely reformed, perhaps not only from a musical point of view.

Communication discloses complex questions. Can incommunicable music even exist? Is it the same with two people who speak different languages and don’t understand each other?

Unfortunately, it can happen, and it does happen especially with certain contemporary music. I said it a few moments ago, I don’t believe music is a universal language that communicates with everybody in the same way, so I equally don’t believe in universal incommunicability; yet, sometimes it can be difficult for some to access certain kinds of music. We just witnessed this with Mozart, no wonder it’s even more so when it comes to the so-called avant-garde, experimental music, like that realized in Darmstadt, where compositional and organizational principles were often based less on intuition than they were on science, sometimes even on chance. More often than not listeners are not aware of any of this, or even if they are, they don’t know how to relate to it.

They don’t feel they’re being involved. Are you saying, then, that music may cease to be a language in certain instances?

That’s precisely the point. Some music doesn’t aim to signify, to “say” or “narrate” something, at least not in the sense we are accustomed to in our Western tradition. This music remains a language in the sense of a code which was created by a composer—we still perceive codified units through our senses, and we are led to decode them in accordance with our own listening habits—but as a language it is different every time, changing from composer to composer, and thus being shared by a minority of people.

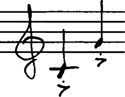

Still, all of us can anticipate the moment in which a finale by Mozart or Beethoven is about to come. All of us almost instinctively respond to the following melodic cell [Example 4.1a]:

Example 4.1a: Ascending fifth leap

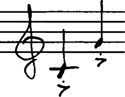

with this [Example 4.1b]:

Example 4.1b: Descending fifth leap

That is so because over the centuries, the so-called tonal system has been widely adopted as the language of Western music. Aside from gradually evolving, this system substantively drew on melody, harmony (based on scales and on definite relations between the scales’ degrees), and rhythm (meant as a regular time matrix); all of these parameters were shared by a large collectivity.10

Before this system was adopted, modality was in use, harmony could already be inferred, but was rather understood in terms of voices moving autonomously and simultaneously. The very concept of tonal organization was yet to come.

When the tonal system and its forms spread and became the standard, they ensured a great number of people a safe anchor to consolidate their own sensibilities and express themselves by creating timeless and extraordinary musical works.

A sort of cornerstone?

Exactly. The twentieth century witnessed instead a speed-up, which can be compared to the amount of all the changes that occurred over five to six earlier centuries combined—in music and more in general in arts and sciences. Languages have exponentially multiplied, and all of this has happened very quickly.

Do you then see the revolutions in musical languages that have occurred in the twentieth century as processes leading to incommunicability, at least in part?

Within the evolution that informed a certain kind of twentieth-century music, sounds have emancipated themselves, at least in theory, from their containers, such as structure, form, grammar, and gesture. This has somehow unsettled almost all that we used to refer to as “music.”

Approaching the musical fact has turned into a true problem, and this certainly hasn’t helped to draw “bridges” between those who create music and those who listen to it.

Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde already marked a revolutionary milestone—its melodic chromaticism rendered functional harmony more ambiguous; it undermined tonal consequentiality, making it less and less predictable.

With the twelve-tone theory elaborated in the early twentieth century by Schoenberg, the pivotal chord hierarchies in the tonal system (self-evident in terms such as “dominant,” “subdominant,” and “tonic”) lost their meaning altogether. The democratization of sounds unsettled the dictatorship of scale degrees and consequently the very concept of tonality crumbled.

Following Schoenberg, there came Anton Webern and his followers. They theorized the integral serialization of every parameter, such as timbre, pitch, silence, duration, dynamics, and so on and so forth. All of this pointed to logical organization, pure mathematics—another fatal blow to the tradition.11

One consequence of this revolution was the exclusion of melody (together with its harmonization and rhythm) from the criteria of composition.

The public was consequently deprived of the most important function of the melody, which had thus far worked as a sort of “compass” for the listener. All the more, the increasing difficulty connected to the rapid progress of the various languages made comprehension even harder. Listeners were required to accept sounds devoid of any shared traditional rule, while composers asked nothing more than simply perceiving sounds for what they are—sounds in themselves, combined in free forms.

This was further exacerbated as the category of “sound” opened up to gradually include noise. Musical Futurism, Luigi Russolo and his intonarumori,12 Charles Ives, Edgard Varèse, and several other composers were all key in the progression leading into musique concrète. In 1949, Pierre Henry and Pierre Schaeffer composed Symphonie pour un homme seul using sounds of footsteps, breaths, slamming doors, the noise of a train, and a police siren, thus starting the Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrète.

The process of continuous innovation and research drove post-Webernians into developing total serialism, according to which compositions draw on complex logical procedures and speculations; all the parameters are serialized and report to a matrix that predetermines the logic-mathematical structure informing every detail of the work. Messiaen, Boulez, Stockhausen, Berio, Maderna are perhaps the most famous interpreters of those experiences. Never had such a peak in complexity been hit before, at times leading to extraordinary results, other times to decidedly less memorable outcomes.

That was the moment in which I landed in Darmstadt. After finishing at the conservatory I wanted to engage in the world around me by creating something that was all mine and original. But the side of the music world that I met there was new to me.

I was shocked by what I heard and saw. “Is this what they call new music?” I asked myself.

I remember Evangelisti playing excellent improvisations at the piano, at the level of Stockhausen’s earliest Klavierstücke.13 Have you ever listened to them?

Sure. However, the Klavierstücke are not improvised, but composed precisely through total serialism, the ultimate frontier of avant-garde research in those years. The formal, grammatical, gestural sense of the tradition was set into crisis, to say the least, not by a total absence of rules, but by their abundance.14

This is the point. Someone may think of it as a provocation, but the question many of us shared at that time was: “What’s the point of devising such complex systems if, in the moment of listening, complexity reaches the ears as a totally open improvisation, or even as noise?” At any rate, I was attracted to it and composed the three pieces I mentioned before—3 Studi, Distanze, and Musica per undici violini. Meanwhile, John Cage was demonstrating that chance too was an option for new music.

The ingredients of his revolution were nonsense, improvisation, and audacious silence. With his work, Cage delegitimized many post-Webernians. Still, what would the composer’s task become after reaching that point? Improvisation, calculation, or something else?

Nobody had solutions, but we still had to deal with a moral imperative concerning the figure of the composer and our work in front of history, society, and culture, in order to find a meaning, both exterior and inner, in the uncertainties of those times. Research turned to novelty, originality at all costs. We ended up in a situation where a work would be considered good merely because of its difficulty, its impenetrableness—the lower the public consensus, the higher the satisfaction of the composer, who could thus consider having accomplished his or her goal.

Moreover, in Italy, the notion of musical pureness, of music for music’s sake was perpetuated in the wake of Benedetto Croce’s idealism, a philosophical doctrine that had pervaded music aesthetics in the first half of the twentieth century and had been embraced by both academia and music critics—in short, the figures who had been responsible for the education of my colleagues and myself.15 Any music that didn’t conform to the established criteria of purity and autonomy from extramusical meanings fell into public contempt; applied music was despised and, implicitly, hierarchies between high and low musical “classes” were strengthened. The constraints were so substantial that they determined not only our aesthetics, but also our very ideas about “composing.”

This too was probably a necessary passage, even though as a result communication between composers and the public was all the more complicated, perhaps compromised.

This brings to my mind the lines pronounced by the industrialist’s son in Teorema by Pasolini, the moment in which he finds out he is a homosexual wanting to be a painter. While stacking the glass panes he has just finished painting, he tells himself:

It’s always necessary to come up with new techniques, which are unrecognizable . . . and therefore resemble no previous works or methods; to avoid the childishness of the ridiculous . . . so as to build a world in which it is possible to be anything . . . and for which there is no previous measure of judgment. . . . It should be new like the techniques. . . . No one must realize the painter’s worthless, that he’s a moron, inferior, that he’s no better than the worm that writhes to keep alive, that they’re comparable. . . . Nobody should appreciate him or think he’s clever. . . . It must all be presented as if perfected, as if based on unknown rules which therefore cannot be judged. . . . Like a fool, yes like a fool! . . . Glass on glass, since I can’t correct anything . . . but nobody must realize that. . . . Although a stroke painted on one glass can correct, without spoiling it, a stroke painted before, on another glass, but nobody must believe that it’s all the result of being powerless, impotent. . . . It must seem to be a firm decision, unhesitating, high and almost overbearing. . . . Nobody must know that a brush’s stroke succeeds by chance, by chance and in trembling, . . . that as soon as a line turns up well done by miracle, . . . it must be covered up right away and protected as in a reliquary. . . . But nobody, nobody must catch on! The painter is a poor shaking fool, a half-ass who lives by chance and by risk, as ashamed as a child, he has reduced his life to the ridiculous melancholy of one thrown down by the impression that something has been lost forever. . . .

Pasolini underpins these words with Mozart’s Requiem, a Mass for the dead.

But, even admitting that a composer’s goal is to set up a world closed in itself, for which no comparisons are possible, to which no previous standards apply, does this mean that one should give up communicating with the outside world and relate only to him- or herself and their work? If every composition is an autonomous, independent, and incommunicable entity, a dead language denying its own relational nature, does it instead aim to produce death and separation? For one thing, it pursues the death of the community and celebrates the triumph of individualism, breaking the social contract between the two parts involved—the makers and the users.

This is what many started professing in varied ways. Just speaking about it brings back all that weightiness. A sense of void and confusion was in the air; at the same time one could perceive a certain presumption growing larger and more radical, the moral imperative to go on at all costs in that direction, no matter what. It was a dead end.

My mind goes to a great flutist like Severino Gazzelloni, who performed Evangelisti’s “crosswords” in Darmstadt, to the glue used to stick flies to the staff paper, to the newspapers distributed in place of scores to the musicians . . . was it a perverse plot? If yes, against whom exactly: the audience, the performers, or the composers themselves?

As time went by, I started suspecting that, rather than “perversion,” it was a matter of provoking or maybe defending our belonging to an intellectual and musical class that aimed to distinguish itself from the rest. Only rarely was there true honesty and real experimentation.

A class who based its raison d’être, its power on inaccessibility?

Everyone coped with that situation in their own way; in the meantime, however, we had lost most of our public, our main interlocutors.

We had begun making music based on certain principles, sticking with criteria that seemed sacred and undisputable, and then we saw practically all of them dismantled right under our noses. Composers were tangled up in a complicated knot.

Which direction should music take?

Someone started promoting the narrative that music was dead, while all other expressive forms were nearing their end.

A deep silence hangs over us. Ennio remains absorbed for some moments, I do too. Like we can feel the impasse of communication weighing on us.

It was chaos.

Or something like it, at least for me.

Suddenly, in the summer of 1958, something deeply struck me in that general confusion. Cori di Didone [Dido’s Choruses] for mixed chorus and orchestra by Nono, based on texts by Ungaretti, hit me down in my core. There it was, an abstracted expressivity intermingled with cold logics, set up on tight calculation.

The reaction of the concert hall was immediate; everybody cried in unison, “Encore!”

It was a moment of convergence between the most elaborate logics, the strictest calculation, and a kind of expressivity that was new and familiar at once. Contrarily to most of what I had heard during those days, that piece succeeded in moving and stimulating me.

Before going to Darmstadt, I had already heard a recording of Il canto sospeso [The Suspended Chant] (1956), for solo soprano, alto and tenor, mixed chorus, and orchestra, and that work had also left me breathless.

Two systems—a mathematic and an expressive one—proceed side by side in those two compositions, nurturing one another. Their most disruptive power consists precisely in this tension.

Like some sort of hope?

Yes, in this complementarity I primarily found the pleasure of listening, but also hope and a possible direction to follow, which I fully embraced. Back in Rome, I completed three compositions, which still today satisfy me in that they musically translated my experience in Darmstadt and my reactions to it. Calculation, improvisation, and expressivity could almost touch each other and communicate, lining up in the same compositional project. I was not aware of all this up front, not in the terms I am speaking of it today. Back then there was no time to reflect, and my worries were others. I needed to work with music to be able to survive and support my family, and this also implied that I should please the taste of my clients, who could not be bothered with incommunicability issues.

I was anguished with the fear of betraying the world of research, to which I owed my background—a world which still represented for me a source of values and enrichment, besides being faced with enormous challenges. Therefore, the more I was led afar from research over the years, the more I would nourish my own personal worldview; no matter how disputable the latter would be, it came to constitute my very being as a composer.

Particularly for this reason, the Darmstadt experience was a turning point for me.

A certainty grew inside me as I realized that all the greatest composers in history were able to make science and logic coincide with expressivity, using the languages they shared with their colleagues at the time and improving them with elements that had not previously existed, thus determining a more or less conscious change in the course of things.

Musical works that have been passed on to us from the Western tradition have brought to our knowledge the evolution and the experiments that past composers condensed and established as they lived their times to the fullest, split between logics and emotion, rationality and irrationality, reason and instinct, calculation and improvisation, freedom and constraints, experimenting and newly reconfiguring preexisting elements. These syntheses were in turn a mirror of the society that produced them and entertained manifold relations with all kinds of other human activities. Those were qualities that I also found in Nono’s work, as well as in other great composers I still respect and admire.

I often draw parallels between music, history, and the evolution of thought. I tell myself, “Maybe it’s not by chance that Schoenberg’s twelve-tone democracy, which ascribes the same value to all sounds, was formulated a hundred years after the French Revolution with its motto ‘liberté, égalité, fraternité’—then followed by the Revolutions in 1848 and the national independences a few years later.” These historical events undoubtedly bore a deep influence on the development of musical thought. The very term “dominant” in the tonal system is opposed by the idea of “democracy,” which suggests an antihierarchical vision of sounds. How can one not see a linkage between these things? In my view there are dynamics that transcend the musical facts, music’s language and its inner rules, and can be related to extramusical, social, political, and philosophical factors. In the second half of the twentieth century, for instance, the fall of dictatorships can be linked to an extremely fast evolution in music and in the other arts and sciences. All of them have moved quickly to develop an extremely vast multiplicity of theories, languages, hypotheses, and reformulations.

To be precise, we are not the first to argue that links exist between music and society. For example, a composer like Mozart worked in an apparently more stable context, as compared to a present composer, at least as far as language is concerned. In a letter to his father on December 28, 1782, he declared à propos of his series of concertos for piano and orchestra K 413, K 414, and K 415, “These concertos are a happy medium between what’s too difficult and too easy—they are Brilliant—pleasing to the ear—Natural, without becoming vacuous;—there are passages here and there that only connoisseurs can fully appreciate—yet the common listener will find them satisfying as well, although without knowing why.”16

The target and the context within which such music was composed, performed, and distributed is clear—a ritual for the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie. However, while Mozart was able to secure his own space within this apparent stability, realizing a kind of polite complexity through his music that flows effortlessly, his music is anything but obvious if one takes a look at the score.17The logical transparency of his music is paralleled by the illuminist confidence in a reality that can be subdued through the instruments of deduction and rationality. The triumph of reason, in which everything is consequential (at least in appearance) and all is representation and thus spectacle, is interpreted with the self-confidence of someone who can relax and enjoy his time knowing that he has the winning card in his pocket—reason, indeed. Think of Così fan tutte, where everything is fictionalized—a theater-within-the-theater staging played around with comedy.

When the French Revolution came, on the other hand, Beethoven had already started questioning the relation between mankind (including himself) and history. Is it mankind who determines history or history that governs mankind? This question remains unanswered in Beethoven, who spent his entire life deconstructing the sonata form (as well as many other forms) driven by a constant urge of change within a thick flowing of invention and fantasy. He remained split, prisoner of his dilemma—do I believe or not? Am I the maker of my history and destiny, or do history and destiny shape my identity?

The grand opéra, like the historical novel, took on these issues with special vigor. Mankind over history, or the other way around? This was typically done by setting the love story of two youths against the backdrop of history’s adversity. I’m thinking of The Betrothed by Manzoni, dealing with an impossible love story amid epidemics, wars, and adversities. Love, death, the Middle Ages, the Greek theater. . . . Romanticism flourished in these subjects. Then comes the Wagner case.

Wagner created a musical and theatrical language that exposed the human subconscious and the instincts inhabiting it. In his syntax, harmonic functions are maintained and articulated only to make their ambiguities emerge—the same way the irrational is shifting and mutable. Through melodic chromaticism and the recurrence of semitones, which may represent the subjugation of the individuals (but also their emotions and impulses), Wagner stretched the boundaries of vertical harmony, the chords, which instead stood for the social contract, the rational, and the conscious. Harmonic functions are stated, but only to be denied. Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk, the total work of art, shares elements with Dostoevsky’s polyphonic novel: there is not one reality, it depends on the watcher’s perspective.18Meanwhile, Freud’s psychoanalysis and later Einstein’s relativity were about to break through in Europe.

God was declared dead by Nietzsche, together with several other certainties, which were being confronted by a wave of relativism. It was easy to sense that the end of an epoch was approaching. The heavy decadence of European culture, melancholically smashed and dismantled by the advancing future, can be sensed in Mahler’s music, in Thomas Mann’s writings—both of which, in my opinion, share this paradoxical melancholy of the future—and later in some films by Leone, Bertolucci, Pasolini, Visconti, and others; more in general, in all the contradictions characterizing the twentieth century.

He remains silent for a moment, immersed in his thoughts.

During my studies, I repeatedly observed sharp contrasts unraveling between different epochs. To give an example, while Romantic music was linked to interiority and irrationality and was concerned with the evocation of emotions, the twentieth century turned to decidedly scientific, logical, structural, and mathematic criteria, which led to a complexity of musical codes never before reached to such an extent. Those were two opposite attitudes and sensibilities that guided the research and the evolution of music, science, and philosophy. As a consequence, techniques too progressed and in turn supported research and change. Certain things grow up independently and connect to others, somehow connecting mankind as a whole. Therefore, I must confess that I believe in a natural, synchronic progress of all facets of art throughout history.

I perceive a veiled positivism in your words. You subsume all the human activities within this “contrasting dynamic” and consider languages and music as organisms that transform in order to survive. This continuous oscillation, which seems to characterize mankind in all its manifestations, works as a push toward life, research, discovery, preservation, and, in addition, motion and becoming.

It is like chasing the solution of a mystery that will probably always slip away—even if we will come to understand part of it, it won’t stop changing and vanishing. Every point of arrival is, consequently, a new start. All this leads us to deal with the present, with our time, which we must live to the fullest—it’s the only way to find our own path and ultimately ourselves.

According to your vision, there wouldn’t seem to be a great difference between the primal scream of our ancestor, the Homo musicus, and what “making music” means today to a composer. Even if things have become dramatically more complicated since the age of the earliest discoveries about sound, the primordial intention to communicate with others has endured. Some avant-gardes may have attempted to resort to mathematics and logics in order to escape randomness, anguish, and solitude (or, conversely, in the quest for God); but this has paradoxically led them to an even greater isolation. Giving credit for a moment to this line of interpretation, we may as well say that, rather than incommunicability, we have gone through a period of “in-communication”—the communication with our inner selves that doesn’t necessarily demand a way back to the outside, but rather self-reflection, internal exploration aimed at better understanding certain facets of ourselves and the way they relate among themselves and with the world.

This is a very interesting point. When we wondered about the origins of music and made up such fascinating, mysterious, and emphatic hypotheses, we imagined that originally music served for a human’s self-determination in the world, a means of communication, “the scream that became a song.” The essential function mankind assigned to music might have been a response to such a primary pulse, and would have been retained over time.

I’ve spoken more and more about a certain type of music, especially my own concert music, in terms of “sound sculpture.” I think the word “sculpture” satisfactorily represents an element of my musical poetics, in that as much as one can feel a stone by touch, one can perceive a sequence of timbres and sounds through listening. One is put in touch with sound matter the way he or she touches a stone or a block of marble.

“Don’t listen to music in the way you’ve been accustomed to,” I keep saying. “Think of the sounds as though they had a shape, as though they were part of a sculpture.”

Indeed, I found myself facing this issue in examining part of your work. How do I speak to readers interested in a musical work, honestly and in a possibly communicative way? Due to the necessity of translating something nonverbal into words, I realize that I tend to oscillate between a structural description, aimed at identifying, isolating, comparing, and analyzing elements, micro- and macro-structures, recurrent patterns; and a semantic analysis, which attributes arbitrary meanings to listening.

For instance, when listening to your Fourth Concerto, I began visualizing whirlwinds of concentric sand—a totally personal and private association. But how do I approach this idea? Perhaps not by searching for communicative and linguistic elements, but embracing a sensorial, possibly synesthetic experience, almost like letting free associations flow through private and personal symbolic paths.

It’s like holding a big stone in our hands. Attempting to dialogue with the object would be useless, not to mention a very unlikely manner to obtain answers. We could instead opt for a tactile perception, a perception that engages ourselves as subjects, but simultaneously encompasses the interpretive stratifications that instinctively spring from our culture, from the evolution of mankind and, according to some, from the “collective subconscious.” The object, in other words, is hollowed of all its meanings, it is us who, according to the need, may want to attach a specific meaning to it and assign it a function, thus defining the position of the object in the world and, as a result, our own place in relation to the object.

It seems almost as if you were talking about a mechanism of “projection.” Indeed, most of the imagery you draw on to describe my Fourth Concerto appertains to you as a perceiving subject. This process, which pushes the listener to interpret, is even more relevant when the composer does not necessarily aim to “imply something,” but presents a determined sound object to the public.

What about communication? How does it come about at this point?

Everything depends on what the composer wishes to do with his or her sculpture, as well as on the surrounding context and the meaning that anybody can or wishes to attribute to it. There are no univocal solutions. After surviving ideological dictatorships of various kinds—in music as in society—we have reached a greater freedom in musical languages today than in the past, without giving away the presence of relevant scientific elements in the compositional stage. Composition, however, no longer depends on dogmatic theorizations about what it ought to be, it is no longer anchored to a consolidated practice, but varies according to the author and the context.

The problem today is no longer whether we want to communicate or not, but to whom we communicate and how. Making myself understood is as important to me as pursuing my own personal research, which is likely to be challenging for the average listener. I will say more: these two aspects may even go hand in hand.

Thanks to the concrete experience I have gained in my lifetime, I have come to realize that a piece of music may receive better feedback than another depending both on the way it is written and how it is circulated. I have painstakingly come to understand that what I intuit to be the meaning of a message in a given moment may not be the same for other people. We discussed this earlier; music is not a universal language, it is based on codes which composers share, at least in part, with an audience.

In my career as a composer there have been moments of experimentation and other moments more settled, definite, and clear; as well as others in which the two poles converged, both in my absolute and my applied music. When I started composing pieces that needed to be understood by the masses—even without forgetting that experimenting was a crucial aspect for me—I aimed to be as accessible as possible, while trying, however, not to give into banality. I alternated phases of transition and consolidation with phases of experimentation.

For this reason, I have partly moved away from the vision—typical in new music circles—that the composer is the uncompromising carrier of novelty. In my opinion, the audience should sometimes make an effort, but composers should do the same for their part. In communication, it is not possible to ignore the other’s needs, even when, paradoxically, communication does not deal with anything specific. All prominent composers tried to be understood by the audiences of their time. We can take Mozart as an example. As we were saying, he respected the canons of his time, but brought them to flourish, thanks to his genius and fantasy.

Today, composers have extensive freedoms in experimentation, and shared canons are more fleeting than ever. But it’s the same with race cars—it’s fair to experiment in your garage, but when the time comes to race, you join the fray to win. I don’t despise the avant-garde, but I believe that after reaching a certain point, composers have a duty toward the public and toward themselves—the duty to be understood, to be felt, at least in their intentions; only then can the present and especially the future credit them for their attitude and their actions. I can’t judge my own deeds, least of all, those of others.

The path I’ve traveled so far has led me to discover many things in this process of experience. Several reflections we have been touched on converged and found an answer in the Gruppo d’Improvvisazione di Nuova Consonanza, which pursued, to a certain extent, an extreme, radical, and uncompromising experimentation. Other answers I had to find in my personal composition activity for movies and such.19

Initially it was hard to harmonize my ideals of composition, the technical background gathered during my school years, and my early work in the record industry and in film. When you are a student you look for your own personality, your own vision of music, yet I was forced to attempt a personal synthesis of all these elements. Records must be sold, you can’t afford incommunicability! It’s no easy task being yourself, with your own ideals and language, while serving a film production and, most important, an audience at the same time.

I’ll give you an example. There was a moment in my life, starting with the first three film scores I made for Dario Argento—The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970), The Cat o’ Nine Tails (1971), 4 Flies on Grey Velvet (1971)—when I decided to adopt a completely different writing style from the one I normally used in cinema. I wanted to experiment in a more contemporary and dissonant language, embracing techniques that reached beyond Webern’s influence. I started to gather ideas, melodic and harmonic fragments based on twelve-tone techniques, utilizing principles derived from Schoenberg’s dodecaphony.

I collected these materials in two books that I called Multipla—a thesaurus from which I could pick and combine any of them in a different way every time. Every idea was numbered and could potentially be assigned to any instrument or orchestral group (e.g., idea 1 to the clarinet, the trumpet, or the first violins, etc.) and matched with other ideas (phrases, melodies, chord sequences). In other words, I created a handbook of combinable musical modules.

In the recording room, I would assign to the orchestra the free dissonant structures that I had previously prepared; while a group of instruments would play parts 1 and 2, I would give the attack for part 3 to another group, and so on—I later applied the same procedure to the voices in Exorcist II: The Heretic.

I would conduct the performance in sync with the film screening, and the score would offer a wide variety of options, which is why I started using the term “multiple scores.” The outcome was an array of swarming, dissonant sonorities, a semi-aleatory atmosphere that was shaped in the process of performing, through live choices I directed via my gestures. Of course, the skills of the performers were decisive. All this was enhanced by the sixteen-track mixing that I had at my disposal at the time, with which I was able to obtain an even greater variety of post-produced sonorities.

Seeking the functional double aesthetic that I was trying to explain earlier, I had planned up front to pair such a dissonant and semi-aleatory texture to some tonal music box–like melodies. In the horror and thriller genres these elements work well, both separate and combined. For most of the public, dissonance produces a state of tension, uncertainty, and uncanniness, whereas extremely simple, childlike themes work as anchors for listeners and concurrently sound chilling in context.