If industrial music is one part optimistic techno-fetishism, its other indubitable twentieth-century precondition is every bit as literary as Futurism, if more cynical.

William S. Burroughs, a techno-paranoid American author often grouped with the beat movement, contributed two ideas to industrial music specifically. First was the alignment of authority figures and controlling agencies into one metaphorical identity of the machine, and second was an artistic means of exposing, questioning, and subverting humankind’s mechanized enslavement to this machine.

Burroughs’s fiction is generally interpreted less as storytelling than as sociology, tactics, and philosophy. Burroughs’s outspoken distrust of tradition, authority, and order has roots and manifestations in his life prior to and beyond his writing, and indeed much of his oeuvre is essentially autobiographical. For these reasons, we’ll want to cover some facts about him before discussing his writing.

Born in St. Louis in 1914, less than a year after Russolo published “The Art of Noises,” Burroughs attended the Los Alamos Ranch School in New Mexico, later annexed by the U.S. government for the purpose of developing the atomic bomb. Early in life, he was surrounded by technology and privilege—his grandfather patented an adding machine and brought the family significant wealth.

A Harvard dropout, Burroughs was a social misfit, both effeminate and violent. His evasion of military service during World War II, his homosexuality, his drug-addiction in the 1940s and 1950s, and his expatriation to Mexico all bespoke a seedy unfitness to dwell in the day’s whitewashed America. His most unsavory moment came in 1951, when he killed his common-law wife, Joan Vollmer, in what was allegedly a bizarre accident. Vollmer, a unique exception to his sexual preference, was playing “William Tell” with Burroughs at a party in Mexico City; firing his gun while drunk, Burroughs missed the water glass she’d balanced atop her head, and shot her in the skull. As he was awaiting trial, his brother bailed him out and he left the country. He was found guilty in absentia but never served time. (For what very little it’s worth now, Burroughs would express constant repentance and sadness over the incident for the rest of his life.)

All this happened before Burroughs wrote his first novel, the 1953 autobiographical Junkie. The ideas that he articulates in the book and especially in its dizzyingly schizophrenic successors make the most sense when we understand them as reflections of the particular political moment that framed the sordidness of his early life. Once we understand that the inherited worldview of industrial music has its origins in the actual historical world whose norms of acceptability and taste Burroughs found himself so grossly violating, then not only do we see his writings as preconditional but we can better understand industrial music as part of a meaningful response to real events and attitudes.

As an illustration of the world in which—and against which—Burroughs lived, consider the American panic in the early and mid-1950s over brainwashing, a process by which it was widely thought that decent citizens could be subconsciously conditioned to carry out acts of war, espionage, and treason. Within the day’s popular understanding, these secret soldiers wouldn’t even need to know of their own hidden allegiance but might instead be sleeper agents, trained to activate when a signal was given.

Edward Hunter, the American agent and journalist who coined the term, described brainwashing as “a planned confusion of the mind where shadow takes form and form becomes shadow.”1 Note in this description how the line between shadow and form erodes, and thus the host and parasite entwine in one another until they’re indistinguishable. Whether penetrative brainwashing really occurred during Joseph McCarthy’s Red Scare or not, it framed the traditional means and ends of conflict—diplomacy and resources, for example—as merely metaphors or tokens, and instead it acknowledged humans themselves as the targets, weapons, and prizes in any real bid for domination. Individual citizens were incited to doubt their very identities in the face of monolithic authority.

To politically critical westerners, the individual powerlessness insinuated by the threat of communist brainwashing was only half of the equation: the so-called free countries that warned of reprogramming’s unprovable dangers were similarly conditioning their own citizens into fearful obedience. The anticommunist witch hunt spearheaded by McCarthy in the name of freedom had the effect of branding any nonconformity as anti-American, and so it’s not merely in the pages of Junkie that one saw a “tie-up between narcotics and Communism”; indeed, all of decent western culture cast suspicion on “other”-ness of any sort as evidence of moral, economic, governmental, industrial, and military infiltration.2

This left Burroughs and any other leftist, gay, drug-using, art-creating, nonwhite, or otherwise “undesirable” citizen trapped in a matrix that reinforced a distrust of authority both at home and abroad. In England, among the most tragic cases to reify the metaphors of the machine, government, and sexuality was the apparent suicide in 1954 of Alan Turing, pioneer of computing and artificial intelligence, who was accused of homosexuality—a charge that brought with it the implicit suspicion of embodying “the myth of the homosexual traitor,” as his biographer David Leavitt explains.3

Seemingly beleaguered for his every move (rightly or not), Burroughs fostered a paranoia toward authority in all its guises, and he began assembling an idiosyncratic theory of control. In his post-Junkie work, he uses the term control machines to refer to technology, religion, government, and language. The control machine as an idea can be seen as a peculiar version of Debord’s spectacle, or of what Marx calls “the whole superstructure,” or of philosopher Theodor Adorno’s notion of “the culture industry.” These models all vary in their specifics, but they identify an overarching set of invisible connections between hegemonically ubiquitous cultural entities.*

To Burroughs, control machines occupy conceptual spaces, defining and overtaking them, ultimately supplanting whatever neutrality they might once have had. For example, he believed that language and technology had come to occupy a broadly human space and that their subsequent stranglehold over modern life was no less insidious and enslaving than the heroin addiction with which he personally struggled; it’s what he calls “the algebra of need.”

These metaphors may seem a little mixed up—with rapidity, Burroughs invokes the ideas of language as a virus, control images, and cultural imperialism—but such haphazard depictions effectively reveal a sinister interchangeability among control machines: they were all out to get him, whoever they were. Thus, in his post-Junkie output, gods, beasts, corporations, nations, chemicals, and radio waves literally morph into one another throughout scatologically overripe, nonlinear orgies of space aliens, third-world prostitution, cowboy mythologies, and mind-scrambling drugs. In the 1991 film adaptation of his 1959 book The Naked Lunch, typewriters are sexual appendages, giant sentient bugs, and undercover federal agents all at once.

Importantly, this fluidity doesn’t just serve to conflate control machines; it also combats them. In order to hold dominion, a control machine needs to inhabit a stable domain, and so the gross nonsense of Burroughs’s writing denies the control machine any kind of stable space. Just as the addict needs the drug, the drug is useless without the addict, or as literary theorist David Seed puts it, the machine “cannot be imagined in separation from the agencies that exercise it.”4 Burroughs’s claim that the pages of The Naked Lunch could be read in any order wasn’t just a gimmick, then, but a move to tear down the structure that houses the machine—the organism and ego to which is it parasitic. He attempts to bypass the authorities of language and thought to which prose and readers alike are hosts, unbeknownst and addicted.

This particular conception of power and its conflation is exceedingly important to the industrial mind-set. Let’s get back to the music now to see how Burroughs’s ideas play out.

The band KMFDM, whose name is an acronym for Kein Mehrheit Für Die Mitleid—an intentionally confusing rearrangement of “Kein Mitleid Für Die Mehrheit” (“no sympathy for the majority”)—places itself by virtue of the name outside of the aforementioned majority and is thus “othered.” In “A Drug Against War,” the opening song from 1993’s Angst, the band’s lead singer Sascha Konietzko shouts in a one-note melody a litany of what Burroughs would call “control machines,” his message to a presumably adolescent audience hitting closer to home with each line: “Television, religion, social destruction. Sex and drugs … Parental advice leads to mental erosion.”

This all happens over a 322 bpm heavy metal-influenced backing track that commences with a sample of what one presumes is a military man, ordering, “Bomb the livin’ bejeebers out of those forces.” Not only do the sample and the repeated lyrical references to war and “empty shells fall[ing] to the ground” imbue the song with clear martial signification, but the music itself encodes this too. In the introduction and the chorus, Doppler effect sounds of falling bombs gently glide over the racket; the piercingly unrealistic drum machine snare straddles a convenient resemblance between a marching band and a machine gun. At 322 bpm, the eighth-note snare fills at the end of verses fire at about eleven rounds every second—the same rate as an AK-47. Once this is juxtaposed in proximity with what appears to be an actual sample of gunfire just over a minute into the track, the connection is clear. On one level then, media, religion, sex, drugs, and parents are invoked, all literally on the same note, and thereby flattened into a monolithic unit of authority. But beyond that, the military—and by extension the government (note the sample at 1:09, “what you’re advocating is a bigger war,” employing the rhetoric of politics)—are similarly faces of the very same agents of “mental erosion.”

Just as KMFDM’s name bizarrely swaps acronymic word placement, the band inverts the Nixon-Reagan language of the War on Drugs to serve their purposes as a self-declared Drug Against War. In doing so, they upend the violent signification of their music, for despite the panicked sample at the song’s end, insisting that we “kill everything,” the same authority figure whose commands to bomb began the track replies calmly “That’s not enough,” taking what may have been plausibly readable as the band’s reveling in militarism to a level of droll absurdity. Indeed, KMFDM’s incessant name checking, ironic use of gospel backup singers, and comic book style cover art by illustrator Aidan “Brute!” Hughes all wink knowingly to fans. This rejection of genuine military ideology relegates martial authority to the ranks of the lyrics’ aforementioned television and religion, and Konietzko makes that clear when he sneers about “cremation of senses in a friendly fire,” stepping out of the war that he otherwise might be accused of egging on. While the sound effects pervading the recording literally resemble the sounds of war, Konietzko tells us in the second verse that he brings “sonic bombardment,” effectively defanging any connection of these recorded bombs to real ones: they remain sounds. KMFDM’s music refuses to take part in supporting the power structures whose interchangeability it reveals.

The Burroughsian practice of equating power structures and authorities until they’re all gears of the same machine appears again and again in industrial music. In 1989, the Belgian duo à;GRUMH…, who were early players in the dance-oriented subgenre called Electronic Body Music (or more commonly, EBM), released the A-side “Ayatollah Jackson.” Like KMFDM, à;GRUMH… conflates military force, religion, and government as they chant, “The sacred book on Sunday, the machine gun every day … Oran para la dictadura, el processo de la democracia [Pray to the dictatorship, the process of democracy].” The song’s lyrics alternate from verse to verse between French, English, and Spanish, offering up manifestolike tirades in each, and in the process squashing even different languages into one communicative mechanism where any tongue is interchangeable with another. There’s even a little nod of self-awareness of this in a lyrical phrase near the song’s end, “Mediatic verses,” which acknowledges that this linguistic switching is itself as much a part of the song as the words sung in each language—a tidy encapsulation of the theorist Marshall McLuhan’s famous assertion that “the medium is the message.”5 And of course, the song title’s juxtaposition of a religious authority’s name alongside a pop idol’s again brings television and the mechanisms of celebrity into a conceptual tangle that now includes warfare, religion, totalitarianism, democracy, and language itself.

Figure 2.1: Song structure of “Ayatollah Jackson” by à;GRUMH…

The harmonies of “Ayatollah Jackson” also support the free interplay of these signs. At the song’s heart is a one-measure-long synthesizer bassline whose rhythm is unchanging atop a steady 128 bpm dance beat. The bass pattern is played chiefly in B-flat minor but shifts up to E-flat minor a handful of times as the song continues, and although this is a common move in pop harmony, its occurrence is peculiarly timed against the lyrics. To understand this better, take a look at the structure of the song (Figure 2.1).

Although we can easily connect E-flat as a bass pitch with the song’s chorus, instead of differentiating the lyrical content of the song, this move highlights the interchangeability both of language and of power structures invoked lyrically.

Here’s how: in the opening verse of “Ayatollah Jackson,” à;GRUMH… sings of “Les fous de Dieu [The fools of God].” Then, when the song hits what is nominally the chorus (as indicated by its repetition and chord change), its subject is also (this time in English) “The fools of God.” If the song’s harmonic motion to the chorus is to mean anything at all, then why would it underlie a simple lyrical restatement—the only one in the song? The answer to this question is not to be found in the interplay of the languages sung; English is used plenty over a B-flat bass in addition to the chorus E-flat, and E-flat is neither exclusive to the chorus nor to English, since it’s the chord over which the line “Agobiar el cuerpo es un mensaje de amor [the oppression of the body is a message of love]” is previously sung.

This may all seem a bit dizzying, but in short, the sameness of lyrical meaning in both verse and chorus, with B-flat and E-flat centers alike, tends to collapse any difference we might derive from the song’s internal parts.6 This is why listening to the song feels like a plateau with no peak; it resists traditional differentiations of structure.

Adding to the confusion still are the perplexing durations of the track’s internal sections. Across western pop genres, the overwhelming tendency is for the lengths of musical phrases and indeed whole verses and choruses to be four, eight, or sixteen measures long; our ears and our bodies are attracted to rhythmic powers of two. The leftmost column of the chart above not only reveals a tendency toward awkward sectional lengths, especially in the first half of the song, but also shows that corresponding sections—the three verses, their post-verses, and the several breaks—lack consistency even unto themselves. Verse lengths are six, twelve, and eight measures, while postverse lengths are three, four, and seven measures. The patterns one expects to find in the relationships between lyrics and music in a song are clouded here by a nearly arbitrary set of internal dimensions. Differentiated, discrete spaces in a piece of music help us make sense of the whole, but when the sung subverts the structural hallmarks that musically and linguistically govern how, for example, dictatorship, democracy, God, the body, and Michael Jackson all differ from one another, then the music aligns these subjects into an amorphous mixture of power entities: the machine is de-institutionalized.*

Neither a metaphorical trick nor arbitrary, these metamorphoses are in fact the goals in Burroughs’s algebra of need. He writes, “The ultimate purpose of cancer and all virus is to replace the host,” and so, for example, in The Naked Lunch, when a man is through experimentation somehow “de-anxietized,” Burroughs reveals that the paranoia lifted from him was in fact the virus on which his humanity relied; it had invisibly replaced its host.7 Now free of it, the character “turns to viscid, transparent jelly that drifts away in green mist, unveiling a monster black centipede.”8

More famous and perhaps most significant in Burroughs’s writing is the literal equation of language with disease, mentioned earlier: “the written word was literally a virus that made the spoken word possible. The word has not been recognized as a virus because it has achieved a state of stable symbiosis with the host.”9 Thought without words is nearly impossible; humans and language are defined in relation to one another. Concerned in his boundless paranoia that language itself is an agent of enemy control, Burroughs sought to liberate humanity and literature from the assumptions and constraints that language imposes, and in doing so he laid the second of his two principal foundations for industrial music.

Film scholar Anne Friedberg exposes in the writings of Burroughs the response to the word-as-virus situation. Quoting his book The Ticket That Exploded, Friedberg explains, “Within the viral metaphor, ‘inoculation can only be effected through exposure.’ Words and images must be used, but only in recombinative patterns.”10

Burroughs achieved this inoculation through what he and co-author Brion Gysin called the “cut-up” method of recontextualizing and remixing signs. The story goes that Gysin, a writer, painter, and friend of Burroughs, began experimenting in the summer of 1959 with cutting pages of text into vertical columns, and then rearranging these long strips of paper in random order. The effect, as they discovered, was that the essential linguistic character of the original text in many cases remained, but the strange phrases and fragments that resulted from reading what was no longer a linear text offered entirely new images and meanings. Burroughs recommends mixing texts and repeating the process—“As many Shakespeare Rimbaud poems as you like”—in order to “produce the accident of spontaneity.”11 Mechanization becomes the text’s author. It samples and digitizes raw artifacts from the surrounding world and from the machinist’s mind.

Gysin and Burroughs acknowledged that Dadaist Tristan Tzara may have been the first to experiment with this idea, when, onstage in 1916, he caused a ruckus by reading random words drawn from a hat, declaring that he was thereby creating a new poem on the spot. However, the key innovation this time around lay in Gysin and Burroughs’s belief that the cut-up possessed real power to disrupt the textual worlds from which it derived. Having quickly applied the method to tape recording and photography, Burroughs wrote, “I have frequently observed that this simple operation—make recordings and take pictures of some location you wish to discommode or destroy, now play recordings back and take more pictures—, will result in accidents, fires, removals.”12 If this viral inoculation could work to shut down a business or cause a traffic jam, then by cutting up and reordering the sounds of industry, authority, religion, commerce, and war, those held under their sway might be deprogrammed as the control machines sputter and reveal their own evil; this is the glitch described in this book’s introduction. Burroughs and Gysin called the new meanings and effects that result from the juxtaposition of texts (or the collaboration of individuals) the third mind—a powerful narrative voice whose own forceful will does not come from a single text or author, nor even their sum, but is discursive, autonomous, even sentient.*

Although collage has been a technique in pop music production since the mid-1950s (first used in Buchanan and Goodman’s 1956 hit “The Flying Saucer”), the cut-up as a means of producing seemingly random internal juxtapositions from within a starting text shares a particular and deep kinship with industrial music. Unlike collage, the cut-up is specifically imbued with an agenda: it is a method of détournement that, in the words of Guy Debord, asserts “indifference toward a meaningless and forgotten original”—indifference that is especially pronounced and political when the original demands allegiance.13

It’s not just this anti-author(ity) sentiment and power that attracts industrial music to the cut-up; in fact there have been specific historical connections that both instructed and reinforced the genre’s use of the technique. Demonstrating and contributing to the cut-up’s industrial kinship is the personal and creative relationship between Burroughs and Genesis P-Orridge, founder of Throbbing Gristle and of Industrial Records, the label from which the entire genre takes its name. P-Orridge writes of meeting Burroughs for the first time in 1971:

He took the remote and started to flip through the channels, cutting up programmed TV. I realized he was teaching me. At the same time he began to hit stop and start on his Sony TC cassette recorder, mixing in “random” cut-ups of prior recordings. These were overlaid with our conversation, none acknowledging the other, an instant holography of information and environment. I was already being taught. What Bill explained to me then was pivotal to the unfolding of my life and art: Everything is recorded.* If it is recorded, then it can be edited. If it can be edited then the order, sense, meaning and direction are as arbitrary and personal as the agenda and/or person editing.14**

P-Orridge goes on: “If reality consists of a series of parallel recordings that usually go unchallenged, then reality only remains stable and predictable until it is challenged and/or the recordings are altered, or their order changed.”15 This outlook is compatible not only with P-Orridge’s somewhat idiosyncratic magical perspective but also with the cyberpunk and hacker-oriented ideas and imagery that would saturate and characterize industrial music later in the 1980s and 1990s.

P-Orridge’s tutelage under and championing of Burroughs and Gysin led to the release of a collection of Burroughs’s 1959–1978 cut-up archives through Industrial Records—the 1981 LP Nothing Here Now but the Recordings—and to his co-curating the autumn 1982 “Final Academy” multiperformance event at the Ritzy Cinema in Brixton, South London, which featured both Burroughs and Gysin as well as the first performance by P-Orridge’s spin-off group Psychic TV. This extravaganza is remembered by many as a high point in the history of industrial thought and music.

Cut-up techniques have propelled songs to popularity in industrial circles during every era of the genre; Front 242’s 1988 “Welcome To Paradise,” the Evolution Control Committee’s 1998 “Rocked By Rape,” and Boole’s 2002 “America Inline” are good examples. However, P-Orridge’s literally religious fervor toward the practice suggests Throbbing Gristle’s music as an especially potent case study. Though the next chapter will explore the band’s music in greater depth, for now consider Throbbing Gristle’s track “Still Walking.”

“Still Walking” appears on both the 1979 album 20 Jazz Funk Greats and 1980 Heathen Earth, which is a recording of a live in-studio performance. In its original 1979 incarnation, driving the song is a sputtering, reverberated sixteenth-note pulse of a low-pitched analogue synthesizer, panned cyclically between right and left channels, with drum machine snares and clinks doubling the rhythms. Amidst this flanged clattering—all run through a low-frequency oscillator called the “Gristleizer,” built by band member Chris Carter—are guitar groans (played by Cosey Fanni Tutti) and violin shrieks (courtesy of P-Orridge), processed to sound more like circular saws than stringed instruments. The song enacts an obsessive arbitrariness: no pitch, no moment, no process takes center stage as the sounds careen about the stereo field in static agitation.

Listening carefully, however, reveals a peculiar nonlinear lyric, spoken by each of the band’s four members, starting at different moments and taken at differing paces. In his study of 20 Jazz Funk Greats, musician and scholar Drew Daniel writes, “The oblique lyrical snippets hint at a resolution, a domestic, occult scenario kept just out of sight … one is being given too much information, and yet the band is also holding something back.”16 Indeed the text, which band member Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson acknowledges as having cut-up origins, bears the abstraction of Burroughs as well as the oddly nondescript capacity to mean both nothing and anything—like a “contentless scene” acting exercise.17

this end

or all of us

he said

all of us do it

each time asleep

each time he said

especially again

especially item

But the cut-up process becomes a formal element of “Still Walking” not merely through the text’s genesis; it is the random juxtapositions and phasing of the text when spoken by the band’s members that bring it into dialogue with itself. Every word and phrase that we discern beneath the noise is called to meaning against every previous speech and speaker in the song.

A better understanding of “Still Walking” can be gleaned when we consider not only the 1979 album version but also the 1980 rendition from Heathen Earth.

The song’s title and duration are the same, but at first glance that’s where the similarities end. In the 1980 recording, the only instrumental feature is a quiet bass swelling that gently breathes in a slow rhythm, like the swinging of a pendulum or the beating of a heart. Gone are the screeching strings and the ugly drum machine chattering. The text spoken throughout the song is an entirely different, too. The 1979 “Still Walking” text, in addition to its blank banality, makes reference to ritual, totem, water, and a “spell of semen”; P-Orridge calls it a magical text and Christopherson relates its origins to P-Orridge’s fascination with occultist Austin Osman Spare.18 In contrast, the 1980 text, divided between Christopherson and Tutti, comes across more as prostitution than ritual. Christopherson recalls, “Cosey and I used to do this sort of thing spontaneously. It was almost like we were having a separate conversation with somebody else, but the combination of alternating lines between us produced a third mind.”19 In this version, Christopherson incessantly offers awkward lines such as “You walkin’ on that way? ‘Cos uh, I’ve got to get on this way as well” and “I’ve got everything that we need; we could just go”—lines that might be conceivably innocent at first were it not for Tutti’s world-weary utterances of “You make it a bit too obvious” and “A little bit later, maybe.” This text’s identity as a failed pickup is one of many “third minds” that arise from its internal possibilities. What keeps us from hearing the performance as just a two-minded dialogue is that Christopherson and Tutti’s lines are never in response to one another, but they instead overlap: they are two simultaneous monologues. The suggested world of the speakers is not contiguous in time or perception but is cut up. And like the 1979 “Still Walking,” a contentlessness hovers uneasily in mysterious lines such as “Twice before he said it, he said, it was twice” and “If you catch them, don’t waste it.” Here, instead of the title “Still Walking” conjuring a spiritual journey, it suggests through Tutti’s disinterest in the sleazy pickup lines that she herself is the one still walking, presumably away from Christopherson. Cutting up the milieu a step further is the repetition and reverberation of the spoken text, an effect of live sampling, processing, and playback (often shifted in pitch and speed), thus producing moments not of two speakers coinciding but three: a literal specter of the third mind.

Why read so much into these recordings? Because the fact that the Heathen Earth track purports to be the same song as the jittering noise on 20 Jazz Funk Greats points to the conclusion that the defining characteristic of “Still Walking,” at least as far as Throbbing Gristle is concerned, isn’t a strictly musical one at all. The piece is less an arrangement of sound than a highlighting of the cut-up as process.

Composer and archivist of experimental music Michael Nyman writes, “Identity takes on a very different significance for the more open experimental work, where indeterminacy in performance guarantees that two versions of the same piece will have virtually no perceptible musical ‘facts’ in common.”20 This is wholly in keeping with the notion of the cut-up: the cutter doesn’t seek to mold materials into a preconceived final work of art but instead merely enacts the process and allows the randomness of its effects to dictate the ends. As such, if we view “Still Walking” as a process of textual and performative cut-up instead of a prescriptive set of sounds, then it’s no surprise these two versions should differ so much to the ear; how indeed could they not?

Throbbing Gristle is a consistently good band for illustrating the importance of process. Beyond the argument by comparison available to us with “Still Walking,” we can turn to 1975’s “Final Muzak” to get another angle on the issue. The song is an instrumental loop with tuneless drones and a mechanically repeating percussive rhythm. A close listening reveals nonrepeating diffusions of beat emphasis, phasing, and rhythmic displacement in the percussion loop, but more significantly, over the course of the piece’s five and a half minutes, the main droning instrument moves very gradually up in pitch by the interval of a minor third. This process is too slow to hear as it happens, but it functions as a large-scale gesture within the illusion of stasis. By virtue of this pitch shift being the only directional change in the music, “Final Muzak” is de facto about that shift, which in real time is functionally content-free, both perceptually inaudible and performatively impossible for humans. Owing heavily to Chris Carter’s electronic and tape techniques, the work takes on the conceptual sheen of foregrounded structure and process.

One of the difficulties that plague conversations about industrial music is that the genre has come to include (to the chagrin and outright denial of some purists) anything from gentle synthesized droning to metal-inspired riffage. Recognizing that a process can drive industrial music’s creation as much as a desired sonic profile can helps us understand this apparent disparity. As both a practical and an ideological tool of industrial music, the cut-up technique doesn’t discriminate between dialogue, guitars, synthesizer textures, or ethnomusicological field recordings; nor should it. This helps explain not only how “Still Walking” takes on different masks but how near-whimsical recordings by a band like Nurse With Wound share a kinship with, say, Nine Inch Nails’ disorienting and intricate remix of “Gave Up” (courtesy of Coil) on their Fixed EP.

The cut-up itself isn’t prerequisite to industrial music, but the freedom it imbues to musicians in their treatment of sonic building blocks remains essential to the genre, as does the larger idea of détournement, of which it is one type. This freedom isn’t mere license to move beyond the limits of human logic and performability—indeed, even the most basic cut-ups, edits, and hip-hop record scratches can achieve this—but, getting more directly at the worldview adapted from Burroughs, the cut-up as an idea grants license to test the limits of the technology involved. In 1995, the band Coil released an album as ELpH Vs. Coil, called Worship the Glitch. As the title suggests, its central themes come from misfires in sound programming, computer crashes, and accidental damage to recording equipment. In fact, ELpH is the name that Coil gave to the “spiritual entity” that seemed, to them, to create unexpected technological errors and bugs in the execution of their music—yet another third mind, this time between the band’s members and their machinery. The record’s influence is most strongly heard today in the glitch genre of electronic music, beyond what normally passes for modern industrial. But the aesthetics of failure, born of “following [machine’s] mistakes,” as Coil’s John Balance puts it, is as industrial an idea as any.21 By challenging the capacity of the machine to operate, musicians bypass having to question whether their own reinterpretations and appropriations of technology are merely part of an even larger hidden control mechanism; Burroughs himself wrote in a pre-digital age, “it is especially difficult to know what side anyone is working on, especially yourself.”22 The randomness is now precisely the error of the machine, and not the operation of its potential sleeper agent.

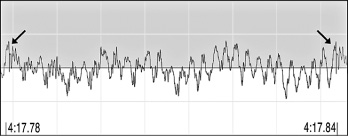

Among the spiritual ancestors of this practice is the Black Album, recorded in December 1975 by Boyd Rice, an American artist who would later found the band NON. The record comprises loops of easy listening and pop from the midtwentieth century, warped, sped up, slowed down, mixed, and shredded. Its packaging indicates that it is to be played at any speed, thus denying the turntable final authority over a “correct” hearing of the piece. To this date, the album has never been given an official CD release, out of recognition of and respect for this insistence that the work not be bound by machine-driven conventions. More recent examples of machine failure as an aesthetic in industrial music include the late 1990s work of the Australian band Snog, and “futurepop” act Icon of Coil’s 2004 club hit “Shelter,” in which the song’s hook—the repetition of the line “where I feel safe”—contains a signature glitch effect created in software by repeating a 0.06 second–long vocal snippet seven times in succession, leaving a jagged, discontinuous digital seam flapping in the breeze between beats. This is visibly indicated in the soundwave of Figure 2.2, excerpted from the song.

Figure 2.2: Soundwave of excerpt from “Shelter” by Icon of Coil, showing digital cut-and-paste repetition. Arrows indicate the repeated seam of the cut.

The point of all this is that the cut-up doesn’t need to be dogmatic in order to bear its subversive power. With regard to its strictest form as he and Gysin first developed it, Burroughs acknowledged in 1979 that “one arrives at a point where, cutting a page, you can cut and cut it to infinity; but, as one goes along, the results become less and less convincing.”23 Indeed, Burroughs himself continued to use narrative as a backbone of his writings, recognizing, as beat scholar Oliver Harris puts it, “that to maximize the potency of his texts it was necessary to retain a dialectical relation to the conventional prose that defined the norm against which cut-ups were designed to act.”24 Both Burroughs and P-Orridge, in their respective later works, reveal a more nuanced relationship with the cut-up than one of mere use-and-disuse for effect: having experimented with its randomness for years, having consummated their commitment to the third mind, and having pushed the boundaries of both their own authorhood and their chosen media’s capacity to bear it, they involuntarily speak with a transformed artistic voice. Swallowing the cut-up into oneself—and along with it, its jagged denial of consensus—makes for an artistic base state of hyperassociation and magical thinking, whatever the technical means of one’s creative work. A charitably optimistic view of industrial music might suggest this state of affairs acts as a microcosm of the whole genre’s relationship with such overt experimentalism.

In his 1992 collaboration with the band Ministry, Burroughs orders us to “Cut word lines. Cut music lines. Smash the control images. Smash the control machines.” This cutting and smashing is by no means a rejection outright of the viral agents of mind control—words, technology, belief—but instead it’s a reversal of these agents’ powers upon themselves. As both the fragmented recordings to be cut up and as the recording device, machines are necessary to smash the machine, just as vaccination is achieved through viral exposure. It is through this reality that one can’t view Burroughs and industrial music as merely technophobic; instead they have a techno-paranoid streak. Industrial music’s debt to Futurism’s uncomplicated machine idolatry precludes a Luddite, antitechnological response to its perception of media totalitarianism—this isn’t folk music we’re talking about. So as the music stakes out territory amidst the larger machines it seeks to dismantle and rewire, it’s thus appropriately ambivalent. In perusing even the names of industrial bands, albums, and songs, we can see in roughly equal amounts a valorizing and humanizing of technology as well as a reactionary call to destroy it. Examples of technophilic titles include:

“Steelrose” (by Project Pitchfork)

L’Âme Életrique (by Die Form)

“Electronic New Self” (by the Fair Sex)

Futureperfect (by VNV Nation)

“Passion for the Future” (by Manufacture)

“Utopian Landscapes” (by Cruciform Injection)

“The Gift of Machine” (by Inure)

“Machineries of Joy” (by Die Krupps)

Machines of Loving Grace (band)

“Celestial Circuitry” (by Object)

And examples of techno-paranoid titles include:

“Punish Your Machine” (by Front 242)

“Machine Slave” (by Front Line Assembly)

“Cybernetics and Pavlovian Warfare” (by A Split-Second)

The Pain Machinery (band)

“The Micro-Implant Conspiracy” (by Oneiroid Psychosis)

Death to Digital (by Julien-K)

My Psychotic Motor (band)

“Future Dead” (by Tactical Sekt)

“The Agony of the Plasma” (by SPK)

Dystopian Visions (compilation album)

This ambivalence remains unresolved throughout industrial music history; individual artists may favor a particular vision for their own deprogramming tactics, but the majority of the genre’s ubiquitous conceptual ties to the machine are themselves attitudinally ambivalent, like the band Einstürzende Neubauten’s name (“collapsing new buildings”), or “Cyberchrist,” a phrase that offers equal parts hope and cynicism, and which was used as a song title by no fewer than seven industrial bands between 1993 and 1995 alone. At the political heart of this ambivalence is the “transforming, liberating potential in new technologies” versus the “fear that the mass media will create passive, onedimensional audiences,” cultural historians James Naremore and Patrick Brantlinger famously wrote in 1991, concluding, “Perhaps both [views] are correct. …”25

The prehistory in this and the preceding chapter has traced specific ideas rather than sounds because these ideas help us understand the baseline condition that makes industrial music possible. Not only is there plentiful documentary evidence of the music’s debt to Futurism and Burroughs, but the lenses of their worldviews effortlessly assimilate, interpret, and account for the musical and lyrical themes of the genre.* A blunt version of this argument is that industrial music’s fascination with technology, experimentation, violence, ugliness, and destruction is Futurism’s legacy, while the antiestablishment paranoia, the free polymorphism of authority signifiers, and the haphazard retooling of contexts are the echoes of Burroughs. On the other hand, a more detailed understanding plays into what scholar Bret Wood calls “the ambiguous nature of industrial itself,”26 where, just as the machine is a stand-in for a number of power structures, the duality of interpretations of the machine can bespeak and account for industrial music’s sometimes frustratingly unclear politics. Exemplifying the interactions of these contradictory ideas in practice, when Einstürzende Neubauten performed a sweaty, ear-splitting spectacle of a concert in London in August 1983, Barney Hoskyns wrote in the New Musical Express, “They reverse [F]uturism.”27